User login

Annular plaques on the back and flanks

An 86-year-old African American woman sought care for an asymptomatic rash on her back and flanks that she’d had for 14 months. Physical examination of her trunk revealed 3 to 6 cm annular/arcuate plaques with central clearing. The lesions also had a delicate trailing scale behind a slightly raised erythematous rim (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythema annulare centrifugum

Potassium hydroxide (KOH) testing and culture of the rash were negative, but a KOH of the skin between her toes and her toenails revealed septate hyphae, which confirmed a diagnosis of tinea pedis and onychomycosis. The combination of tinea pedis/onychomycosis and the clinical appearance of the rash on the patient’s flanks led us to diagnose erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) in this patient.

EAC is a noninfectious hypersensitivity phenomenon.1 It is most commonly associated with dermatophyte fungi, but other inciting agents include candida, penicillium in blue cheese, viruses (varicella zoster virus, human immunodeficiency virus, Epstein-Barr virus), ectoparasites (phthirus pubis), and, rarely, certain medications, including diuretics, finasteride, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antimalarials, and amitriptyline.2-6 Hormonal changes during pregnancy and neoplasms have occasionally been associated with EAC.2-4

Histologic findings are nonspecific in EAC, but a biopsy may be performed to exclude other conditions. Superficial EAC demonstrates histologic changes primarily in the epidermis, including spongiosis, parakeratosis, and a superficial inflammatory infiltrate.8 The deep variant demonstrates superficial to deep dermal lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate in a perivascular “sleeve-like” distribution with little epidermal change.7,8

Differential diagnosis includes figurate erythemas

The differential diagnosis includes figurate erythemas (erythema chronicum migrans and erythema marginatum) and other conditions with annular, scaling plaques (tinea corporis [ringworm], annular psoriasis, pityriasis rosea, syphilis (secondary stage), and mycosis fungoides).2,9

Figurate erythemas. Unlike EAC, figurate erythemas are non-scaling annular lesions. Erythema chronicum migrans is a manifestation of Lyme disease. It is characterized by papules that expand peripherally at the site of a tick bite. In some cases, secondary lesions distant from the bite occur. Erythema marginatum is associated with rheumatic fever. These nonpruritic red circular rings without scale are unique in their capacity to expand several centimeters per day.

Conditions characterized by annular scaling plaques. Tinea corporis presents as round red patches that slowly become ring-shaped, with a raised border and clear center. Unlike EAC, the scale is present at the leading border of the rings.

Annular psoriasis is characterized by ring-shaped patches with white micaceous scaling and central clearing. Topical steroid use may be responsible for the central clearing as scaled patches expand. This rash can appear in places EAC typically does not, such as on the scalp, elbows, and knees.

Pityriasis rosea starts with a solitary herald patch a few days before hundreds of small oval scaled patches appear on the trunk in a “fir tree” distribution. Unlike EAC, the herald patch does not show the trailing scale.

The rash associated with the secondary stage of syphilis can appear on the soles of the feet and palms, which differs from EAC because EAC typically spares the feet and hands.

In the patch stage of mycosis fungoides, the ring-shaped rash can appear similar to psoriasis or chronic eczema, but can sometimes last years to even decades. Unlike EAC, these rings do not show a trailing scale and the patches may demonstrate poikiloderma (erythema, atrophy, and dyspigmentation).

To treat EAC, eliminate the trigger

Treatment of EAC should focus on eliminating the inciting agent.2 In one study of 66 patients with EAC, 42%, had a concomitant cutaneous fungal infection (tinea pedis, tinea corporis, or onychomycosis).3 A direct cause-and-effect relationship was established in 2 patients with dermatophyte-induced EAC whose lesions were reproduced and subsequently cleared by the experimental inoculation and treatment of tinea pedis.1

Our patient. Four weeks of oral terbinafine 250 mg/d effectively cleared our patient’s case of tinea pedis and EAC. After 3 months of treatment with terbinafine the onychomycosis showed one-third clearing at the proximal nail fold. Without additional treatment, the nails were completely clear 8 months later.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected]

1. Jillson OF, Hoekelman RA. Further amplification of the concept of dermatophytid. I. Erythema annulare centrifugum as a dermatophytid. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1952;66:738-745.

2. España A. Figurate erythemas. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadephia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:307-312.

3. Kim KJ, Chang SE, Choi JH, et al. Clinicopathologic analysis of 66 cases of erythema annulare centrifugum. J Dermatol. 2002;29:61-67.

4. Ziemer M, Eisendle K, Zelger B. New concepts on erythema annulare centrifugum: a clinical reaction pattern that does not represent a specific clinicopathological entity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:119-126.

5. Ohmori S, Sugita K, Ikenouci-Sugita A, et al. Erythema annulare centrifugum associated with herpes zoster. J UOEH. 2012;34:225-229.

6. Shelley WB. Erythema annulare centrifugum. A case due to hypersensitivity to blue cheese penicillium. Arch Dermatol. 1964;90:54-58.

7. Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

8. Ríos-Martín JJ, Ferrándiz-Pulido L, Moreno-Ramírez D. Approaches to the dermatopathologic diagnosis of figurate lesions [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2011;102:316-324.

9. Boucher K, Haimowitz J. Erythema annulare centrifugum. In: Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, et al. Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. New York, NY: Mosby; 2002:188-189.

An 86-year-old African American woman sought care for an asymptomatic rash on her back and flanks that she’d had for 14 months. Physical examination of her trunk revealed 3 to 6 cm annular/arcuate plaques with central clearing. The lesions also had a delicate trailing scale behind a slightly raised erythematous rim (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythema annulare centrifugum

Potassium hydroxide (KOH) testing and culture of the rash were negative, but a KOH of the skin between her toes and her toenails revealed septate hyphae, which confirmed a diagnosis of tinea pedis and onychomycosis. The combination of tinea pedis/onychomycosis and the clinical appearance of the rash on the patient’s flanks led us to diagnose erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) in this patient.

EAC is a noninfectious hypersensitivity phenomenon.1 It is most commonly associated with dermatophyte fungi, but other inciting agents include candida, penicillium in blue cheese, viruses (varicella zoster virus, human immunodeficiency virus, Epstein-Barr virus), ectoparasites (phthirus pubis), and, rarely, certain medications, including diuretics, finasteride, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antimalarials, and amitriptyline.2-6 Hormonal changes during pregnancy and neoplasms have occasionally been associated with EAC.2-4

Histologic findings are nonspecific in EAC, but a biopsy may be performed to exclude other conditions. Superficial EAC demonstrates histologic changes primarily in the epidermis, including spongiosis, parakeratosis, and a superficial inflammatory infiltrate.8 The deep variant demonstrates superficial to deep dermal lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate in a perivascular “sleeve-like” distribution with little epidermal change.7,8

Differential diagnosis includes figurate erythemas

The differential diagnosis includes figurate erythemas (erythema chronicum migrans and erythema marginatum) and other conditions with annular, scaling plaques (tinea corporis [ringworm], annular psoriasis, pityriasis rosea, syphilis (secondary stage), and mycosis fungoides).2,9

Figurate erythemas. Unlike EAC, figurate erythemas are non-scaling annular lesions. Erythema chronicum migrans is a manifestation of Lyme disease. It is characterized by papules that expand peripherally at the site of a tick bite. In some cases, secondary lesions distant from the bite occur. Erythema marginatum is associated with rheumatic fever. These nonpruritic red circular rings without scale are unique in their capacity to expand several centimeters per day.

Conditions characterized by annular scaling plaques. Tinea corporis presents as round red patches that slowly become ring-shaped, with a raised border and clear center. Unlike EAC, the scale is present at the leading border of the rings.

Annular psoriasis is characterized by ring-shaped patches with white micaceous scaling and central clearing. Topical steroid use may be responsible for the central clearing as scaled patches expand. This rash can appear in places EAC typically does not, such as on the scalp, elbows, and knees.

Pityriasis rosea starts with a solitary herald patch a few days before hundreds of small oval scaled patches appear on the trunk in a “fir tree” distribution. Unlike EAC, the herald patch does not show the trailing scale.

The rash associated with the secondary stage of syphilis can appear on the soles of the feet and palms, which differs from EAC because EAC typically spares the feet and hands.

In the patch stage of mycosis fungoides, the ring-shaped rash can appear similar to psoriasis or chronic eczema, but can sometimes last years to even decades. Unlike EAC, these rings do not show a trailing scale and the patches may demonstrate poikiloderma (erythema, atrophy, and dyspigmentation).

To treat EAC, eliminate the trigger

Treatment of EAC should focus on eliminating the inciting agent.2 In one study of 66 patients with EAC, 42%, had a concomitant cutaneous fungal infection (tinea pedis, tinea corporis, or onychomycosis).3 A direct cause-and-effect relationship was established in 2 patients with dermatophyte-induced EAC whose lesions were reproduced and subsequently cleared by the experimental inoculation and treatment of tinea pedis.1

Our patient. Four weeks of oral terbinafine 250 mg/d effectively cleared our patient’s case of tinea pedis and EAC. After 3 months of treatment with terbinafine the onychomycosis showed one-third clearing at the proximal nail fold. Without additional treatment, the nails were completely clear 8 months later.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected]

An 86-year-old African American woman sought care for an asymptomatic rash on her back and flanks that she’d had for 14 months. Physical examination of her trunk revealed 3 to 6 cm annular/arcuate plaques with central clearing. The lesions also had a delicate trailing scale behind a slightly raised erythematous rim (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythema annulare centrifugum

Potassium hydroxide (KOH) testing and culture of the rash were negative, but a KOH of the skin between her toes and her toenails revealed septate hyphae, which confirmed a diagnosis of tinea pedis and onychomycosis. The combination of tinea pedis/onychomycosis and the clinical appearance of the rash on the patient’s flanks led us to diagnose erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) in this patient.

EAC is a noninfectious hypersensitivity phenomenon.1 It is most commonly associated with dermatophyte fungi, but other inciting agents include candida, penicillium in blue cheese, viruses (varicella zoster virus, human immunodeficiency virus, Epstein-Barr virus), ectoparasites (phthirus pubis), and, rarely, certain medications, including diuretics, finasteride, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antimalarials, and amitriptyline.2-6 Hormonal changes during pregnancy and neoplasms have occasionally been associated with EAC.2-4

Histologic findings are nonspecific in EAC, but a biopsy may be performed to exclude other conditions. Superficial EAC demonstrates histologic changes primarily in the epidermis, including spongiosis, parakeratosis, and a superficial inflammatory infiltrate.8 The deep variant demonstrates superficial to deep dermal lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate in a perivascular “sleeve-like” distribution with little epidermal change.7,8

Differential diagnosis includes figurate erythemas

The differential diagnosis includes figurate erythemas (erythema chronicum migrans and erythema marginatum) and other conditions with annular, scaling plaques (tinea corporis [ringworm], annular psoriasis, pityriasis rosea, syphilis (secondary stage), and mycosis fungoides).2,9

Figurate erythemas. Unlike EAC, figurate erythemas are non-scaling annular lesions. Erythema chronicum migrans is a manifestation of Lyme disease. It is characterized by papules that expand peripherally at the site of a tick bite. In some cases, secondary lesions distant from the bite occur. Erythema marginatum is associated with rheumatic fever. These nonpruritic red circular rings without scale are unique in their capacity to expand several centimeters per day.

Conditions characterized by annular scaling plaques. Tinea corporis presents as round red patches that slowly become ring-shaped, with a raised border and clear center. Unlike EAC, the scale is present at the leading border of the rings.

Annular psoriasis is characterized by ring-shaped patches with white micaceous scaling and central clearing. Topical steroid use may be responsible for the central clearing as scaled patches expand. This rash can appear in places EAC typically does not, such as on the scalp, elbows, and knees.

Pityriasis rosea starts with a solitary herald patch a few days before hundreds of small oval scaled patches appear on the trunk in a “fir tree” distribution. Unlike EAC, the herald patch does not show the trailing scale.

The rash associated with the secondary stage of syphilis can appear on the soles of the feet and palms, which differs from EAC because EAC typically spares the feet and hands.

In the patch stage of mycosis fungoides, the ring-shaped rash can appear similar to psoriasis or chronic eczema, but can sometimes last years to even decades. Unlike EAC, these rings do not show a trailing scale and the patches may demonstrate poikiloderma (erythema, atrophy, and dyspigmentation).

To treat EAC, eliminate the trigger

Treatment of EAC should focus on eliminating the inciting agent.2 In one study of 66 patients with EAC, 42%, had a concomitant cutaneous fungal infection (tinea pedis, tinea corporis, or onychomycosis).3 A direct cause-and-effect relationship was established in 2 patients with dermatophyte-induced EAC whose lesions were reproduced and subsequently cleared by the experimental inoculation and treatment of tinea pedis.1

Our patient. Four weeks of oral terbinafine 250 mg/d effectively cleared our patient’s case of tinea pedis and EAC. After 3 months of treatment with terbinafine the onychomycosis showed one-third clearing at the proximal nail fold. Without additional treatment, the nails were completely clear 8 months later.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected]

1. Jillson OF, Hoekelman RA. Further amplification of the concept of dermatophytid. I. Erythema annulare centrifugum as a dermatophytid. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1952;66:738-745.

2. España A. Figurate erythemas. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadephia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:307-312.

3. Kim KJ, Chang SE, Choi JH, et al. Clinicopathologic analysis of 66 cases of erythema annulare centrifugum. J Dermatol. 2002;29:61-67.

4. Ziemer M, Eisendle K, Zelger B. New concepts on erythema annulare centrifugum: a clinical reaction pattern that does not represent a specific clinicopathological entity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:119-126.

5. Ohmori S, Sugita K, Ikenouci-Sugita A, et al. Erythema annulare centrifugum associated with herpes zoster. J UOEH. 2012;34:225-229.

6. Shelley WB. Erythema annulare centrifugum. A case due to hypersensitivity to blue cheese penicillium. Arch Dermatol. 1964;90:54-58.

7. Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

8. Ríos-Martín JJ, Ferrándiz-Pulido L, Moreno-Ramírez D. Approaches to the dermatopathologic diagnosis of figurate lesions [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2011;102:316-324.

9. Boucher K, Haimowitz J. Erythema annulare centrifugum. In: Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, et al. Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. New York, NY: Mosby; 2002:188-189.

1. Jillson OF, Hoekelman RA. Further amplification of the concept of dermatophytid. I. Erythema annulare centrifugum as a dermatophytid. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1952;66:738-745.

2. España A. Figurate erythemas. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Philadephia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:307-312.

3. Kim KJ, Chang SE, Choi JH, et al. Clinicopathologic analysis of 66 cases of erythema annulare centrifugum. J Dermatol. 2002;29:61-67.

4. Ziemer M, Eisendle K, Zelger B. New concepts on erythema annulare centrifugum: a clinical reaction pattern that does not represent a specific clinicopathological entity. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:119-126.

5. Ohmori S, Sugita K, Ikenouci-Sugita A, et al. Erythema annulare centrifugum associated with herpes zoster. J UOEH. 2012;34:225-229.

6. Shelley WB. Erythema annulare centrifugum. A case due to hypersensitivity to blue cheese penicillium. Arch Dermatol. 1964;90:54-58.

7. Weyers W, Diaz-Cascajo C, Weyers I. Erythema annulare centrifugum: results of a clinicopathologic study of 73 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:451-462.

8. Ríos-Martín JJ, Ferrándiz-Pulido L, Moreno-Ramírez D. Approaches to the dermatopathologic diagnosis of figurate lesions [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2011;102:316-324.

9. Boucher K, Haimowitz J. Erythema annulare centrifugum. In: Lebwohl MG, Heymann WR, Berth-Jones J, et al. Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies. New York, NY: Mosby; 2002:188-189.

Inguinal area rash

Concerned that this could be some type of malignancy, the FP performed a 4 mm punch biopsy and the pathology report came back as Paget’s disease.

Extramammary Paget’s disease should be considered in any patient with chronic dermatitis of the groin, vulva, scrotal, or perianal area. Patients with Paget’s disease of the external genitalia often present with nonresolving eczematous lesions in the groin, genitalia, perineum, or perianal area. Pruritus occurs in approximately 70% of patients. Patients may also experience burning, pain, or no symptoms other than the lesion.

The risk of recurrence is higher in men than women. The recurrence rate of primary tumors after standard surgical excision is 30% to 60%. The rate after excision with Mohs micrographic surgery is 8% to 26%. In this case, the FP sent the patient for Mohs surgery to minimize the risk of recurrence.

Photo courtesy of Anna Saucedo, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Paget disease of the external genitalia. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:514-518.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Concerned that this could be some type of malignancy, the FP performed a 4 mm punch biopsy and the pathology report came back as Paget’s disease.

Extramammary Paget’s disease should be considered in any patient with chronic dermatitis of the groin, vulva, scrotal, or perianal area. Patients with Paget’s disease of the external genitalia often present with nonresolving eczematous lesions in the groin, genitalia, perineum, or perianal area. Pruritus occurs in approximately 70% of patients. Patients may also experience burning, pain, or no symptoms other than the lesion.

The risk of recurrence is higher in men than women. The recurrence rate of primary tumors after standard surgical excision is 30% to 60%. The rate after excision with Mohs micrographic surgery is 8% to 26%. In this case, the FP sent the patient for Mohs surgery to minimize the risk of recurrence.

Photo courtesy of Anna Saucedo, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Paget disease of the external genitalia. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:514-518.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Concerned that this could be some type of malignancy, the FP performed a 4 mm punch biopsy and the pathology report came back as Paget’s disease.

Extramammary Paget’s disease should be considered in any patient with chronic dermatitis of the groin, vulva, scrotal, or perianal area. Patients with Paget’s disease of the external genitalia often present with nonresolving eczematous lesions in the groin, genitalia, perineum, or perianal area. Pruritus occurs in approximately 70% of patients. Patients may also experience burning, pain, or no symptoms other than the lesion.

The risk of recurrence is higher in men than women. The recurrence rate of primary tumors after standard surgical excision is 30% to 60%. The rate after excision with Mohs micrographic surgery is 8% to 26%. In this case, the FP sent the patient for Mohs surgery to minimize the risk of recurrence.

Photo courtesy of Anna Saucedo, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Paget disease of the external genitalia. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:514-518.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Perineal and perianal pruritus

The biopsy revealed that the patient had Paget’s disease of the vulva. Paget’s disease of the external genitalia is an uncommon primary cutaneous adenocarcinoma of apocrine gland-bearing skin. Lesions present as geographic red macules that often appear excoriated or have an eczematoid appearance. Lesions may be dotted with small, white patches. Patients may also present with erythematous, eczematous, or leukoplakic plaques.

The most commonly involved site is the vulva, although perineal, perianal, scrotal, and penile skin may also be affected. Aside from the location, Paget’s disease of the vulva is morphologically and histologically identical to Paget’s disease of the nipple.

Up to 25% of patients with genital Paget’s disease have an underlying neoplasm. Associated malignancies include carcinomas of Bartholin’s glands, urethra, bladder, vagina, cervix, endometrium, and adnexal apocrine tissue. Only a small number of cases represent a direct extension of an underlying carcinoma.

In this case, the patient was sent to a gynecologic oncologist for a wide local excision of the involved area. The health care team planned to follow the patient closely to detect any recurrence at an early stage.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Paget disease of the external genitalia. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:514-518.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The biopsy revealed that the patient had Paget’s disease of the vulva. Paget’s disease of the external genitalia is an uncommon primary cutaneous adenocarcinoma of apocrine gland-bearing skin. Lesions present as geographic red macules that often appear excoriated or have an eczematoid appearance. Lesions may be dotted with small, white patches. Patients may also present with erythematous, eczematous, or leukoplakic plaques.

The most commonly involved site is the vulva, although perineal, perianal, scrotal, and penile skin may also be affected. Aside from the location, Paget’s disease of the vulva is morphologically and histologically identical to Paget’s disease of the nipple.

Up to 25% of patients with genital Paget’s disease have an underlying neoplasm. Associated malignancies include carcinomas of Bartholin’s glands, urethra, bladder, vagina, cervix, endometrium, and adnexal apocrine tissue. Only a small number of cases represent a direct extension of an underlying carcinoma.

In this case, the patient was sent to a gynecologic oncologist for a wide local excision of the involved area. The health care team planned to follow the patient closely to detect any recurrence at an early stage.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Paget disease of the external genitalia. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:514-518.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The biopsy revealed that the patient had Paget’s disease of the vulva. Paget’s disease of the external genitalia is an uncommon primary cutaneous adenocarcinoma of apocrine gland-bearing skin. Lesions present as geographic red macules that often appear excoriated or have an eczematoid appearance. Lesions may be dotted with small, white patches. Patients may also present with erythematous, eczematous, or leukoplakic plaques.

The most commonly involved site is the vulva, although perineal, perianal, scrotal, and penile skin may also be affected. Aside from the location, Paget’s disease of the vulva is morphologically and histologically identical to Paget’s disease of the nipple.

Up to 25% of patients with genital Paget’s disease have an underlying neoplasm. Associated malignancies include carcinomas of Bartholin’s glands, urethra, bladder, vagina, cervix, endometrium, and adnexal apocrine tissue. Only a small number of cases represent a direct extension of an underlying carcinoma.

In this case, the patient was sent to a gynecologic oncologist for a wide local excision of the involved area. The health care team planned to follow the patient closely to detect any recurrence at an early stage.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Paget disease of the external genitalia. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:514-518.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

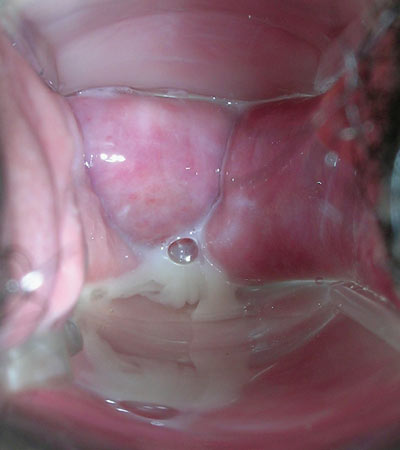

White vaginal discharge

The FP noted a strawberry cervix during the pelvic exam and the wet prep revealed the motile protozoan Trichomonas vaginalis, confirming the diagnosis of trichomoniasis.

The majority of men (90%) infected with T. vaginalis are asymptomatic, but many women (50%) report symptoms. The infection is predominantly transmitted via sexual contact. The organism can survive up to 48 hours at 50°F outside of the body, making transmission from shared undergarments or from infected hot tubs possible. Trichomonas infection is associated with low-birth-weight infants, premature rupture of membranes, and preterm delivery, so treatment is especially important in pregnant women.

In this case, the patient was treated with metronidazole 2 g in a single dose and was sent home with the same prescription for her partner, who didn’t come to the office. (According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, sexual partners of patients with Trichomonas infection should be treated.)

Since the patient was at risk for other sexually transmitted diseases, the FP sent off tests for chlamydia and gonorrhea.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Trichomonas vaginitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:504-508.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP noted a strawberry cervix during the pelvic exam and the wet prep revealed the motile protozoan Trichomonas vaginalis, confirming the diagnosis of trichomoniasis.

The majority of men (90%) infected with T. vaginalis are asymptomatic, but many women (50%) report symptoms. The infection is predominantly transmitted via sexual contact. The organism can survive up to 48 hours at 50°F outside of the body, making transmission from shared undergarments or from infected hot tubs possible. Trichomonas infection is associated with low-birth-weight infants, premature rupture of membranes, and preterm delivery, so treatment is especially important in pregnant women.

In this case, the patient was treated with metronidazole 2 g in a single dose and was sent home with the same prescription for her partner, who didn’t come to the office. (According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, sexual partners of patients with Trichomonas infection should be treated.)

Since the patient was at risk for other sexually transmitted diseases, the FP sent off tests for chlamydia and gonorrhea.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Trichomonas vaginitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:504-508.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The FP noted a strawberry cervix during the pelvic exam and the wet prep revealed the motile protozoan Trichomonas vaginalis, confirming the diagnosis of trichomoniasis.

The majority of men (90%) infected with T. vaginalis are asymptomatic, but many women (50%) report symptoms. The infection is predominantly transmitted via sexual contact. The organism can survive up to 48 hours at 50°F outside of the body, making transmission from shared undergarments or from infected hot tubs possible. Trichomonas infection is associated with low-birth-weight infants, premature rupture of membranes, and preterm delivery, so treatment is especially important in pregnant women.

In this case, the patient was treated with metronidazole 2 g in a single dose and was sent home with the same prescription for her partner, who didn’t come to the office. (According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, sexual partners of patients with Trichomonas infection should be treated.)

Since the patient was at risk for other sexually transmitted diseases, the FP sent off tests for chlamydia and gonorrhea.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Trichomonas vaginitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:504-508.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Vaginal itching

The wet prep revealed pseudohyphae with budding, the hallmark of a candida infection; the patient was given a diagnosis of vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC).

VVC is a common fungal infection in women of childbearing age; it is not a sexually transmitted disease. Patients with VVC will complain of pruritus, accompanied by a thick, odorless, white vaginal discharge.

Based on clinical presentation, microbiology, host factors, and response to therapy, VVC can be classified as either uncomplicated or complicated:

- Uncomplicated VVC is characterized by sporadic or infrequent symptoms that are mild to moderate. Patients are not immunocompromised.

- Complicated VVC is characterized by recurrent (≥4 episodes in one year) or severe VVC and may involve non-albicans Candidiasis, or a patient who has uncontrolled diabetes, debilitation, or immunosuppression.

Treatment options include topical over-the-counter azole antifungal creams and a single dose of fluconazole 150 mg orally. In this case, the patient bought over-the-counter antifungal cream and her symptoms cleared quickly.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Candida vulvovaginitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:499-503.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The wet prep revealed pseudohyphae with budding, the hallmark of a candida infection; the patient was given a diagnosis of vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC).

VVC is a common fungal infection in women of childbearing age; it is not a sexually transmitted disease. Patients with VVC will complain of pruritus, accompanied by a thick, odorless, white vaginal discharge.

Based on clinical presentation, microbiology, host factors, and response to therapy, VVC can be classified as either uncomplicated or complicated:

- Uncomplicated VVC is characterized by sporadic or infrequent symptoms that are mild to moderate. Patients are not immunocompromised.

- Complicated VVC is characterized by recurrent (≥4 episodes in one year) or severe VVC and may involve non-albicans Candidiasis, or a patient who has uncontrolled diabetes, debilitation, or immunosuppression.

Treatment options include topical over-the-counter azole antifungal creams and a single dose of fluconazole 150 mg orally. In this case, the patient bought over-the-counter antifungal cream and her symptoms cleared quickly.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Candida vulvovaginitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:499-503.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The wet prep revealed pseudohyphae with budding, the hallmark of a candida infection; the patient was given a diagnosis of vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC).

VVC is a common fungal infection in women of childbearing age; it is not a sexually transmitted disease. Patients with VVC will complain of pruritus, accompanied by a thick, odorless, white vaginal discharge.

Based on clinical presentation, microbiology, host factors, and response to therapy, VVC can be classified as either uncomplicated or complicated:

- Uncomplicated VVC is characterized by sporadic or infrequent symptoms that are mild to moderate. Patients are not immunocompromised.

- Complicated VVC is characterized by recurrent (≥4 episodes in one year) or severe VVC and may involve non-albicans Candidiasis, or a patient who has uncontrolled diabetes, debilitation, or immunosuppression.

Treatment options include topical over-the-counter azole antifungal creams and a single dose of fluconazole 150 mg orally. In this case, the patient bought over-the-counter antifungal cream and her symptoms cleared quickly.

Photo and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Candida vulvovaginitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:499-503.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

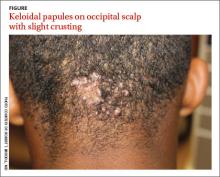

Occipital scalp papules in a teenage boy

A 15-year-old African American boy with no previous medical problems presented with a 2-month history of hair loss and pruritic papules on the occipital scalp that had developed after a barber shaved the area. Physical examination revealed 2 dozen 1 to 2 mm keloidal papules on the posterior neck and occipital scalp with areas of focal crusting (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Acne keloidalis nuchae

Acne keloidalis nuchae is a chronic folliculitis that is characterized by smooth, dome-shaped papules on the posterior scalp and neck that become confluent, forming firm papules and hairless, keloid-like plaques.1 Seen almost exclusively in young, postpubescent African American males, the condition is often asymptomatic, although some patients complain that the affected area itches. The cause of acne keloidalis nuchae may be associated with an acute pseudofolliculitis secondary to close-shaved curly hair reentering the skin; this leads to a foreign body reaction to hair protein and subsequent fibrosis.2

Differential Dx includes acne vulgaris

Acne keloidalis nuchae is diagnosed based on the appearance and location of the papules and keloid-like plaques as well as the patient’s history. The differential diagnosis includes acne vulgaris, hidradenitis suppurativa, and pseudofolliculitis barbae.

Acne vulgaris is a disorder of the pilosebaceous follicles primarily seen on the face, upper part of the chest, and back. Unlike acne keloidalis, it is characterized by the presence of comedones.1,3

Hidradenitis suppurativa is characterized by secondary inflammation of the apocrine glands, which produces inflamed nodules and abscesses, primarily in the axillae, groin, and anogenital region.1

Pseudofolliculitis barbae looks very similar to the initial presentation of acne keloidalis nuchae, and in fact, the pathophysiologic mechanism is the same. That said, pseudofolliculitis barbae occurs on the beard area and rarely produces keloidal papules.3

Treat with steroids, antibiotics

Treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae is often difficult. Early treatment, however, decreases the potential for developing larger lesions and long-term disfigurement.1

Topical steroid therapy is indicated for mild to moderate acne keloidalis nuchae. Application of tretinoin 0.01% gel once or twice daily for several months has an anti-inflammatory effect and alters keratinocyte differentiation, which may discharge ingrown hairs. Topical and systemic antibiotics minimize infection associated with pseudofolliculitis and have anti-inflammatory effects.1,3 Intralesional steroid injections (triamcinolone acetonide 2.5-5 mg/cc) with 0.1 cc injected into each lesion every 2 to 3 weeks for 3 to 6 injections can reduce inflammation and pruritus and reduce the thickness of keloidal scars.3 (For a how-to video that illustrates intralesional injections, go to http://www.jfponline.com/multimedia/video.html.)

Surgical management is generally reserved for large lesions that do not respond to medical management. Surgical excision with healing by secondary intention has been reported to cause fewer recurrences than surgical excision with primary closure.4 The use of CO2 laser ablation can be considered for advanced cases.5

Teach patients with acne keloidalis nuchae that they can prevent further irritation of the affected area by not wearing head gear that rubs on the involved area. Patients should also refrain from shaving the posterior scalp and neck to prevent the pseudofolliculitis that may be causing this condition.1,3 Electric barber trimmers that leave a short stubble but do not cleanly shave the skin are OK to use.

Our patient’s papules flattened and became asymptomatic over several months of treatment with tretinoin 0.01% gel, doxycycline 100 mg daily, and a series of biweekly intralesion steroid injections. A flat-scarred patch remained.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Division of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected]

1. McMichael A, Sanchez DG, Kelly P. Folliculitis and the follicular occlusion tetrad. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo, JL, Rapini RP, et al (eds). Dermatology. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Mosby; 2008: 517-530.

2. Herzberg AJ, Dinehart SM, Kerns BJ, et al. Acne keloidalis. Transverse microscopy, immunohistochemistry, and electron microscopy. Am J Dermatopathol. 1990;12:109-121.

3. Kelly AP. Pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:645-653.

4. Glenn MG, Bennett RG, Kelly AP. Acne keloidalis nuchae: treatment with excision and second-intention healing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(2 pt 1):243-246.

5. Kantor GR, Ratz JL, Wheeland RG. Treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae with carbon dioxide laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(2 pt 1):263-267.

A 15-year-old African American boy with no previous medical problems presented with a 2-month history of hair loss and pruritic papules on the occipital scalp that had developed after a barber shaved the area. Physical examination revealed 2 dozen 1 to 2 mm keloidal papules on the posterior neck and occipital scalp with areas of focal crusting (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Acne keloidalis nuchae

Acne keloidalis nuchae is a chronic folliculitis that is characterized by smooth, dome-shaped papules on the posterior scalp and neck that become confluent, forming firm papules and hairless, keloid-like plaques.1 Seen almost exclusively in young, postpubescent African American males, the condition is often asymptomatic, although some patients complain that the affected area itches. The cause of acne keloidalis nuchae may be associated with an acute pseudofolliculitis secondary to close-shaved curly hair reentering the skin; this leads to a foreign body reaction to hair protein and subsequent fibrosis.2

Differential Dx includes acne vulgaris

Acne keloidalis nuchae is diagnosed based on the appearance and location of the papules and keloid-like plaques as well as the patient’s history. The differential diagnosis includes acne vulgaris, hidradenitis suppurativa, and pseudofolliculitis barbae.

Acne vulgaris is a disorder of the pilosebaceous follicles primarily seen on the face, upper part of the chest, and back. Unlike acne keloidalis, it is characterized by the presence of comedones.1,3

Hidradenitis suppurativa is characterized by secondary inflammation of the apocrine glands, which produces inflamed nodules and abscesses, primarily in the axillae, groin, and anogenital region.1

Pseudofolliculitis barbae looks very similar to the initial presentation of acne keloidalis nuchae, and in fact, the pathophysiologic mechanism is the same. That said, pseudofolliculitis barbae occurs on the beard area and rarely produces keloidal papules.3

Treat with steroids, antibiotics

Treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae is often difficult. Early treatment, however, decreases the potential for developing larger lesions and long-term disfigurement.1

Topical steroid therapy is indicated for mild to moderate acne keloidalis nuchae. Application of tretinoin 0.01% gel once or twice daily for several months has an anti-inflammatory effect and alters keratinocyte differentiation, which may discharge ingrown hairs. Topical and systemic antibiotics minimize infection associated with pseudofolliculitis and have anti-inflammatory effects.1,3 Intralesional steroid injections (triamcinolone acetonide 2.5-5 mg/cc) with 0.1 cc injected into each lesion every 2 to 3 weeks for 3 to 6 injections can reduce inflammation and pruritus and reduce the thickness of keloidal scars.3 (For a how-to video that illustrates intralesional injections, go to http://www.jfponline.com/multimedia/video.html.)

Surgical management is generally reserved for large lesions that do not respond to medical management. Surgical excision with healing by secondary intention has been reported to cause fewer recurrences than surgical excision with primary closure.4 The use of CO2 laser ablation can be considered for advanced cases.5

Teach patients with acne keloidalis nuchae that they can prevent further irritation of the affected area by not wearing head gear that rubs on the involved area. Patients should also refrain from shaving the posterior scalp and neck to prevent the pseudofolliculitis that may be causing this condition.1,3 Electric barber trimmers that leave a short stubble but do not cleanly shave the skin are OK to use.

Our patient’s papules flattened and became asymptomatic over several months of treatment with tretinoin 0.01% gel, doxycycline 100 mg daily, and a series of biweekly intralesion steroid injections. A flat-scarred patch remained.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Division of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected]

A 15-year-old African American boy with no previous medical problems presented with a 2-month history of hair loss and pruritic papules on the occipital scalp that had developed after a barber shaved the area. Physical examination revealed 2 dozen 1 to 2 mm keloidal papules on the posterior neck and occipital scalp with areas of focal crusting (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Acne keloidalis nuchae

Acne keloidalis nuchae is a chronic folliculitis that is characterized by smooth, dome-shaped papules on the posterior scalp and neck that become confluent, forming firm papules and hairless, keloid-like plaques.1 Seen almost exclusively in young, postpubescent African American males, the condition is often asymptomatic, although some patients complain that the affected area itches. The cause of acne keloidalis nuchae may be associated with an acute pseudofolliculitis secondary to close-shaved curly hair reentering the skin; this leads to a foreign body reaction to hair protein and subsequent fibrosis.2

Differential Dx includes acne vulgaris

Acne keloidalis nuchae is diagnosed based on the appearance and location of the papules and keloid-like plaques as well as the patient’s history. The differential diagnosis includes acne vulgaris, hidradenitis suppurativa, and pseudofolliculitis barbae.

Acne vulgaris is a disorder of the pilosebaceous follicles primarily seen on the face, upper part of the chest, and back. Unlike acne keloidalis, it is characterized by the presence of comedones.1,3

Hidradenitis suppurativa is characterized by secondary inflammation of the apocrine glands, which produces inflamed nodules and abscesses, primarily in the axillae, groin, and anogenital region.1

Pseudofolliculitis barbae looks very similar to the initial presentation of acne keloidalis nuchae, and in fact, the pathophysiologic mechanism is the same. That said, pseudofolliculitis barbae occurs on the beard area and rarely produces keloidal papules.3

Treat with steroids, antibiotics

Treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae is often difficult. Early treatment, however, decreases the potential for developing larger lesions and long-term disfigurement.1

Topical steroid therapy is indicated for mild to moderate acne keloidalis nuchae. Application of tretinoin 0.01% gel once or twice daily for several months has an anti-inflammatory effect and alters keratinocyte differentiation, which may discharge ingrown hairs. Topical and systemic antibiotics minimize infection associated with pseudofolliculitis and have anti-inflammatory effects.1,3 Intralesional steroid injections (triamcinolone acetonide 2.5-5 mg/cc) with 0.1 cc injected into each lesion every 2 to 3 weeks for 3 to 6 injections can reduce inflammation and pruritus and reduce the thickness of keloidal scars.3 (For a how-to video that illustrates intralesional injections, go to http://www.jfponline.com/multimedia/video.html.)

Surgical management is generally reserved for large lesions that do not respond to medical management. Surgical excision with healing by secondary intention has been reported to cause fewer recurrences than surgical excision with primary closure.4 The use of CO2 laser ablation can be considered for advanced cases.5

Teach patients with acne keloidalis nuchae that they can prevent further irritation of the affected area by not wearing head gear that rubs on the involved area. Patients should also refrain from shaving the posterior scalp and neck to prevent the pseudofolliculitis that may be causing this condition.1,3 Electric barber trimmers that leave a short stubble but do not cleanly shave the skin are OK to use.

Our patient’s papules flattened and became asymptomatic over several months of treatment with tretinoin 0.01% gel, doxycycline 100 mg daily, and a series of biweekly intralesion steroid injections. A flat-scarred patch remained.

CORRESPONDENCE

Robert T. Brodell, MD, Division of Dermatology, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; [email protected]

1. McMichael A, Sanchez DG, Kelly P. Folliculitis and the follicular occlusion tetrad. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo, JL, Rapini RP, et al (eds). Dermatology. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Mosby; 2008: 517-530.

2. Herzberg AJ, Dinehart SM, Kerns BJ, et al. Acne keloidalis. Transverse microscopy, immunohistochemistry, and electron microscopy. Am J Dermatopathol. 1990;12:109-121.

3. Kelly AP. Pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:645-653.

4. Glenn MG, Bennett RG, Kelly AP. Acne keloidalis nuchae: treatment with excision and second-intention healing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(2 pt 1):243-246.

5. Kantor GR, Ratz JL, Wheeland RG. Treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae with carbon dioxide laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(2 pt 1):263-267.

1. McMichael A, Sanchez DG, Kelly P. Folliculitis and the follicular occlusion tetrad. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo, JL, Rapini RP, et al (eds). Dermatology. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Mosby; 2008: 517-530.

2. Herzberg AJ, Dinehart SM, Kerns BJ, et al. Acne keloidalis. Transverse microscopy, immunohistochemistry, and electron microscopy. Am J Dermatopathol. 1990;12:109-121.

3. Kelly AP. Pseudofolliculitis barbae and acne keloidalis nuchae. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:645-653.

4. Glenn MG, Bennett RG, Kelly AP. Acne keloidalis nuchae: treatment with excision and second-intention healing. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(2 pt 1):243-246.

5. Kantor GR, Ratz JL, Wheeland RG. Treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae with carbon dioxide laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(2 pt 1):263-267.

Preeclampsia and swelling

The physician diagnosed pemphigoid gestationis based upon the multiple bullae on the patient’s skin, including one prominent periumbilical bulla (FIGURE). A more careful history revealed that this was the patient’s third episode of pemphigoid gestationis. A biopsy was not performed because her previous biopsy was on file and the clinical picture was consistent with a recurrence of this disease.

Pemphigoid gestationis is a rare autoimmune bullous dermatosis of pregnancy. The pathophysiology of the disease involves immunoglobulin (Ig) G antibodies that attack cells in the skin. The IgG attacks the same antigen (bullous pemphigoid antigen) as in bullous pemphigoid. This antigen is a transmembrane protein that is part of the hemidesmosome, which connects the basal cells of the epidermis to the basement membrane. When the inflammatory response is activated, the hemidesmosomes are destroyed and the epidermis separates from the dermis. It is not known why some patients form these antibodies.

Pemphigoid gestationis typically regresses spontaneously without scarring within weeks to months of delivery. In this case, the patient was treated with oral prednisone and improved rapidly. The dose was tapered over time and eventually discontinued.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Pemphigoid gestationis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:471-474.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The physician diagnosed pemphigoid gestationis based upon the multiple bullae on the patient’s skin, including one prominent periumbilical bulla (FIGURE). A more careful history revealed that this was the patient’s third episode of pemphigoid gestationis. A biopsy was not performed because her previous biopsy was on file and the clinical picture was consistent with a recurrence of this disease.

Pemphigoid gestationis is a rare autoimmune bullous dermatosis of pregnancy. The pathophysiology of the disease involves immunoglobulin (Ig) G antibodies that attack cells in the skin. The IgG attacks the same antigen (bullous pemphigoid antigen) as in bullous pemphigoid. This antigen is a transmembrane protein that is part of the hemidesmosome, which connects the basal cells of the epidermis to the basement membrane. When the inflammatory response is activated, the hemidesmosomes are destroyed and the epidermis separates from the dermis. It is not known why some patients form these antibodies.

Pemphigoid gestationis typically regresses spontaneously without scarring within weeks to months of delivery. In this case, the patient was treated with oral prednisone and improved rapidly. The dose was tapered over time and eventually discontinued.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Pemphigoid gestationis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:471-474.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The physician diagnosed pemphigoid gestationis based upon the multiple bullae on the patient’s skin, including one prominent periumbilical bulla (FIGURE). A more careful history revealed that this was the patient’s third episode of pemphigoid gestationis. A biopsy was not performed because her previous biopsy was on file and the clinical picture was consistent with a recurrence of this disease.

Pemphigoid gestationis is a rare autoimmune bullous dermatosis of pregnancy. The pathophysiology of the disease involves immunoglobulin (Ig) G antibodies that attack cells in the skin. The IgG attacks the same antigen (bullous pemphigoid antigen) as in bullous pemphigoid. This antigen is a transmembrane protein that is part of the hemidesmosome, which connects the basal cells of the epidermis to the basement membrane. When the inflammatory response is activated, the hemidesmosomes are destroyed and the epidermis separates from the dermis. It is not known why some patients form these antibodies.

Pemphigoid gestationis typically regresses spontaneously without scarring within weeks to months of delivery. In this case, the patient was treated with oral prednisone and improved rapidly. The dose was tapered over time and eventually discontinued.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Pemphigoid gestationis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:471-474.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Itchy abdominal rash

The patient was given a diagnosis of pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy. PUPPP is a dermatosis of pregnancy characterized by a papulovesicular or urticarial eruption on the abdomen (most common initial site), trunk, and limbs. The lesions usually spread to the extremities and coalesce to form urticarial plaques and spare the face, palms, soles, and periumbilical region. Other than maternal itching, PUPPP poses no increased risk of fetal or maternal morbidity.

PUPPP usually occurs late in the third trimester, but may develop postpartum. Pruritus may worsen after delivery, but generally resolves within 15 days of delivery—sometimes even prior to delivery.

The FP prescribed topical 0.1% triamcinolone cream bid and suggested that the patient use over-the-counter oral diphenhydramine, as needed. The medication provided the patient with good relief, and the PUPPP resolved completely after the delivery of a healthy child.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:467-470.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The patient was given a diagnosis of pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy. PUPPP is a dermatosis of pregnancy characterized by a papulovesicular or urticarial eruption on the abdomen (most common initial site), trunk, and limbs. The lesions usually spread to the extremities and coalesce to form urticarial plaques and spare the face, palms, soles, and periumbilical region. Other than maternal itching, PUPPP poses no increased risk of fetal or maternal morbidity.

PUPPP usually occurs late in the third trimester, but may develop postpartum. Pruritus may worsen after delivery, but generally resolves within 15 days of delivery—sometimes even prior to delivery.

The FP prescribed topical 0.1% triamcinolone cream bid and suggested that the patient use over-the-counter oral diphenhydramine, as needed. The medication provided the patient with good relief, and the PUPPP resolved completely after the delivery of a healthy child.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:467-470.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The patient was given a diagnosis of pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy. PUPPP is a dermatosis of pregnancy characterized by a papulovesicular or urticarial eruption on the abdomen (most common initial site), trunk, and limbs. The lesions usually spread to the extremities and coalesce to form urticarial plaques and spare the face, palms, soles, and periumbilical region. Other than maternal itching, PUPPP poses no increased risk of fetal or maternal morbidity.

PUPPP usually occurs late in the third trimester, but may develop postpartum. Pruritus may worsen after delivery, but generally resolves within 15 days of delivery—sometimes even prior to delivery.

The FP prescribed topical 0.1% triamcinolone cream bid and suggested that the patient use over-the-counter oral diphenhydramine, as needed. The medication provided the patient with good relief, and the PUPPP resolved completely after the delivery of a healthy child.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:467-470.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Malodorous vaginal discharge

A wet prep demonstrated clue cells in more than half of the epithelial cells and the FP diagnosed bacterial vaginosis (BV). BV is a clinical syndrome resulting from an alteration of the vaginal ecosystem. The odor of BV is caused by the aromatic amines produced by the altered bacterial flora in the vagina. Women with BV are at increased risk for human immunodeficiency virus, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, and herpes simplex virus-2, and they have an increased risk of complications after gynecologic surgery. BV is also associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes.

The FP recommended that the patient stop douching because it wouldn’t prevent or treat infections and could unfavorably influence the vaginal microscopic ecosystem. In this case, the patient had good results after being treated with oral metronidazole 500 mg bid for 7 days.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Bacterial vaginosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:494-498.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

A wet prep demonstrated clue cells in more than half of the epithelial cells and the FP diagnosed bacterial vaginosis (BV). BV is a clinical syndrome resulting from an alteration of the vaginal ecosystem. The odor of BV is caused by the aromatic amines produced by the altered bacterial flora in the vagina. Women with BV are at increased risk for human immunodeficiency virus, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, and herpes simplex virus-2, and they have an increased risk of complications after gynecologic surgery. BV is also associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes.

The FP recommended that the patient stop douching because it wouldn’t prevent or treat infections and could unfavorably influence the vaginal microscopic ecosystem. In this case, the patient had good results after being treated with oral metronidazole 500 mg bid for 7 days.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Bacterial vaginosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:494-498.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

A wet prep demonstrated clue cells in more than half of the epithelial cells and the FP diagnosed bacterial vaginosis (BV). BV is a clinical syndrome resulting from an alteration of the vaginal ecosystem. The odor of BV is caused by the aromatic amines produced by the altered bacterial flora in the vagina. Women with BV are at increased risk for human immunodeficiency virus, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, and herpes simplex virus-2, and they have an increased risk of complications after gynecologic surgery. BV is also associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes.

The FP recommended that the patient stop douching because it wouldn’t prevent or treat infections and could unfavorably influence the vaginal microscopic ecosystem. In this case, the patient had good results after being treated with oral metronidazole 500 mg bid for 7 days.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Bacterial vaginosis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:494-498.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

Genital itching and burning

The patient was given a diagnosis of lichen sclerosus, which is recognized by the hour-glass configuration of the atrophy around the vulva and perianal region. (Some atrophic changes of the vulva that can be mistaken for the atrophy of estrogen deficiency.)

Lichen sclerosus is not contagious and typically affects postmenopausal women. It's unclear what causes the condition.

Lichen sclerosus is treated with a high-potency steroid ointment (such as clobetasol) rather than estrogen or topical testosterone. Studies have demonstrated that high-potency topical steroid ointments are the most effective treatment and do not cause atrophy as an adverse effect. While topical testosterone was used in the past, it has not been proven effective and should no longer be prescribed.

The topical steroid should be applied twice daily and tapered to once daily followed by an as-needed regimen based on symptoms.

There is a higher risk of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma in patients with genital lichen sclerosus. Yearly examination for premalignant and malignant changes of the external genitalia is recommended. Areas with thick leukoplakia, mucosal ulcerations, and erythroplakia should be biopsied to rule out malignancy.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Atrophic vaginitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:489-493.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The patient was given a diagnosis of lichen sclerosus, which is recognized by the hour-glass configuration of the atrophy around the vulva and perianal region. (Some atrophic changes of the vulva that can be mistaken for the atrophy of estrogen deficiency.)

Lichen sclerosus is not contagious and typically affects postmenopausal women. It's unclear what causes the condition.

Lichen sclerosus is treated with a high-potency steroid ointment (such as clobetasol) rather than estrogen or topical testosterone. Studies have demonstrated that high-potency topical steroid ointments are the most effective treatment and do not cause atrophy as an adverse effect. While topical testosterone was used in the past, it has not been proven effective and should no longer be prescribed.

The topical steroid should be applied twice daily and tapered to once daily followed by an as-needed regimen based on symptoms.

There is a higher risk of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma in patients with genital lichen sclerosus. Yearly examination for premalignant and malignant changes of the external genitalia is recommended. Areas with thick leukoplakia, mucosal ulcerations, and erythroplakia should be biopsied to rule out malignancy.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Atrophic vaginitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:489-493.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/

The patient was given a diagnosis of lichen sclerosus, which is recognized by the hour-glass configuration of the atrophy around the vulva and perianal region. (Some atrophic changes of the vulva that can be mistaken for the atrophy of estrogen deficiency.)

Lichen sclerosus is not contagious and typically affects postmenopausal women. It's unclear what causes the condition.

Lichen sclerosus is treated with a high-potency steroid ointment (such as clobetasol) rather than estrogen or topical testosterone. Studies have demonstrated that high-potency topical steroid ointments are the most effective treatment and do not cause atrophy as an adverse effect. While topical testosterone was used in the past, it has not been proven effective and should no longer be prescribed.

The topical steroid should be applied twice daily and tapered to once daily followed by an as-needed regimen based on symptoms.

There is a higher risk of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma in patients with genital lichen sclerosus. Yearly examination for premalignant and malignant changes of the external genitalia is recommended. Areas with thick leukoplakia, mucosal ulcerations, and erythroplakia should be biopsied to rule out malignancy.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Atrophic vaginitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas of Family Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013:489-493.

To learn more about the Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see: http://www.amazon.com/Color-Family-Medicine-Richard-Usatine/dp/0071769641/

You can now get the second edition of the Color Atlas of Family Medicine as an app by clicking on this link: http://usatinemedia.com/