User login

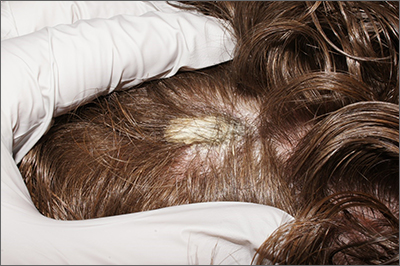

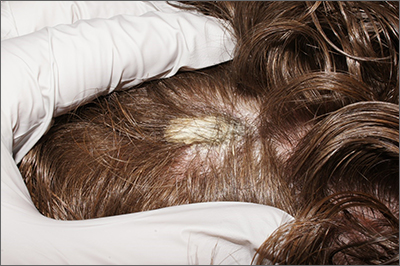

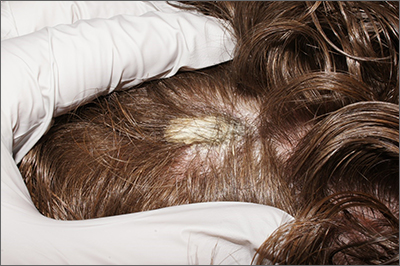

Scalp plaque

A punch biopsy was performed, and the results were consistent with pityriasis amiantacea arising from psoriasis. In an older patient, a keratinaceous horn would be worrisome for a squamous cell carcinoma. In a younger patient, like this one, it is more likely an atypical manifestation of a more common dermatosis.

Pityriasis amiantacea is an unusual disorder in which thick adherent scales form on the scalp; it is most common in children, adolescents, and young adults. There is no racial predilection. With this condition, patients complain of a fixed plaque that may shed scale but not as quickly as it accumulates. It can be an isolated finding, but more often it is a secondary manifestation of an underlying case of psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, tinea capitis, or atopic dermatitis.1

A punch biopsy performed on the scalp should include the skin underlying the compact keratin scale. However, to avoid excessive bleeding, use lidocaine with epinephrine. Allow 15 minutes for the anesthesia to take effect before beginning the procedure.

Treatment depends on the underlying cause but includes debridement of the aggregated scale with a topical keratolytic (such as salicylic acid or topical fluocinolone oil 0.01% applied) at night and washed out 7 to 10 hours later.

The patient was advised to use over-the-counter 2% salicylic acid shampoo daily and to apply topical clobetasol 0.05% solution nightly for 4 weeks and once weekly after clearance for another 3 months. At the 3-month follow-up, the patient’s scalp was clear.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Ettler J, Wetter DA, Pittelkow MR. Pityriasis amiantacea: a distinctive presentation of psoriasis associated with tumour necrosis factor-α inhibitor therapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:639-641. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2011.04286.x

A punch biopsy was performed, and the results were consistent with pityriasis amiantacea arising from psoriasis. In an older patient, a keratinaceous horn would be worrisome for a squamous cell carcinoma. In a younger patient, like this one, it is more likely an atypical manifestation of a more common dermatosis.

Pityriasis amiantacea is an unusual disorder in which thick adherent scales form on the scalp; it is most common in children, adolescents, and young adults. There is no racial predilection. With this condition, patients complain of a fixed plaque that may shed scale but not as quickly as it accumulates. It can be an isolated finding, but more often it is a secondary manifestation of an underlying case of psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, tinea capitis, or atopic dermatitis.1

A punch biopsy performed on the scalp should include the skin underlying the compact keratin scale. However, to avoid excessive bleeding, use lidocaine with epinephrine. Allow 15 minutes for the anesthesia to take effect before beginning the procedure.

Treatment depends on the underlying cause but includes debridement of the aggregated scale with a topical keratolytic (such as salicylic acid or topical fluocinolone oil 0.01% applied) at night and washed out 7 to 10 hours later.

The patient was advised to use over-the-counter 2% salicylic acid shampoo daily and to apply topical clobetasol 0.05% solution nightly for 4 weeks and once weekly after clearance for another 3 months. At the 3-month follow-up, the patient’s scalp was clear.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

A punch biopsy was performed, and the results were consistent with pityriasis amiantacea arising from psoriasis. In an older patient, a keratinaceous horn would be worrisome for a squamous cell carcinoma. In a younger patient, like this one, it is more likely an atypical manifestation of a more common dermatosis.

Pityriasis amiantacea is an unusual disorder in which thick adherent scales form on the scalp; it is most common in children, adolescents, and young adults. There is no racial predilection. With this condition, patients complain of a fixed plaque that may shed scale but not as quickly as it accumulates. It can be an isolated finding, but more often it is a secondary manifestation of an underlying case of psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, tinea capitis, or atopic dermatitis.1

A punch biopsy performed on the scalp should include the skin underlying the compact keratin scale. However, to avoid excessive bleeding, use lidocaine with epinephrine. Allow 15 minutes for the anesthesia to take effect before beginning the procedure.

Treatment depends on the underlying cause but includes debridement of the aggregated scale with a topical keratolytic (such as salicylic acid or topical fluocinolone oil 0.01% applied) at night and washed out 7 to 10 hours later.

The patient was advised to use over-the-counter 2% salicylic acid shampoo daily and to apply topical clobetasol 0.05% solution nightly for 4 weeks and once weekly after clearance for another 3 months. At the 3-month follow-up, the patient’s scalp was clear.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Ettler J, Wetter DA, Pittelkow MR. Pityriasis amiantacea: a distinctive presentation of psoriasis associated with tumour necrosis factor-α inhibitor therapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:639-641. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2011.04286.x

1. Ettler J, Wetter DA, Pittelkow MR. Pityriasis amiantacea: a distinctive presentation of psoriasis associated with tumour necrosis factor-α inhibitor therapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:639-641. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2011.04286.x

An asymptomatic rash

This patient was given a diagnosis of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CRP) based on the clinical presentation.

CRP is characterized by centrally confluent and peripherally reticulated scaly brown plaques and papules that are cosmetically disfiguring.1 CRP is usually asymptomatic and primarily impacts young adults—especially teenagers.2,3 It affects both males and females and commonly occurs on the trunk.1-3 CRP is believed to be a disorder of keratinization. Malassezia furfur may induce CRP’s hyperproliferative epidermal changes, but systemic treatment that eliminates this organism does not clear CRP.3

A CRP diagnosis is made based on clinical presentation. The eruption usually begins as verrucous papules in the inframammary or epigastric region that enlarge to 4 to 5 mm in diameter and coalesce to form a confluent plaque with a peripheral reticulated pattern. CRP can extend over the back, chest, and abdomen to the neck, shoulders, and gluteal cleft. CRP does not affect the oral mucosa, and rarely involves flexural areas, which differentiates it from the similar looking acanthosis nigricans.2 Although most cases are asymptomatic, mild pruritus may occur.1,2

A skin biopsy is rarely necessary for making a CRP diagnosis, but histopathologic findings include papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, variable acanthosis, follicular plugging, and sparse dermal inflammation.1,3

Systemic antibiotics, most commonly minocycline 100 mg bid for 30 days or doxycycline 100 mg bid for 30 days, are safe and effective for CRP.1,4 Sometimes treatment is extended for as long as 6 months. Although CRP usually responds to minocycline or doxycycline, it is believed that this is the result of these drugs’ anti-inflammatory—rather than antibiotic—properties.1,2,4 Azithromycin is an effective alternative therapy.2,4 There is a high rate of recurrence of CRP in patients after systemic antibiotics are discontinued.2 Uniform responses to treatment and retreatment of flares have solidified the belief that antibiotics are an effective suppressive (if not curative) therapy despite a lack of randomized controlled trials.4

This patient was treated with minocycline 100 mg bid. After 1 month, the rash had improved by 70%. At 3 months, it was completely clear, and treatment was discontinued.

This case was adapted from: Sessums MT, Ward KMH, Brodell R. Cutaneous eruption on chest and back. J Fam Pract. 2014;63:467-468.

1. Davis MD, Weenig RH, Camilleri MJ. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome): a minocycline-responsive dermatosis without evidence for yeast in pathogenesis. A study of 39 patients and a proposal of diagnostic criteria. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:287-293. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06955.x

2. Scheinfeld N. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: a review of the literature. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:305-313. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200607050-00004

3. Tamraz H, Raffoul M, Kurban M, et al. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: clinical and histopathological study of 10 cases from Lebanon. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:e119-e123. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04328.x

4. Jang HS, Oh CK, Cha JH, et al. Six cases of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis alleviated by various antibiotics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:652-655. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.112577

This patient was given a diagnosis of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CRP) based on the clinical presentation.

CRP is characterized by centrally confluent and peripherally reticulated scaly brown plaques and papules that are cosmetically disfiguring.1 CRP is usually asymptomatic and primarily impacts young adults—especially teenagers.2,3 It affects both males and females and commonly occurs on the trunk.1-3 CRP is believed to be a disorder of keratinization. Malassezia furfur may induce CRP’s hyperproliferative epidermal changes, but systemic treatment that eliminates this organism does not clear CRP.3

A CRP diagnosis is made based on clinical presentation. The eruption usually begins as verrucous papules in the inframammary or epigastric region that enlarge to 4 to 5 mm in diameter and coalesce to form a confluent plaque with a peripheral reticulated pattern. CRP can extend over the back, chest, and abdomen to the neck, shoulders, and gluteal cleft. CRP does not affect the oral mucosa, and rarely involves flexural areas, which differentiates it from the similar looking acanthosis nigricans.2 Although most cases are asymptomatic, mild pruritus may occur.1,2

A skin biopsy is rarely necessary for making a CRP diagnosis, but histopathologic findings include papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, variable acanthosis, follicular plugging, and sparse dermal inflammation.1,3

Systemic antibiotics, most commonly minocycline 100 mg bid for 30 days or doxycycline 100 mg bid for 30 days, are safe and effective for CRP.1,4 Sometimes treatment is extended for as long as 6 months. Although CRP usually responds to minocycline or doxycycline, it is believed that this is the result of these drugs’ anti-inflammatory—rather than antibiotic—properties.1,2,4 Azithromycin is an effective alternative therapy.2,4 There is a high rate of recurrence of CRP in patients after systemic antibiotics are discontinued.2 Uniform responses to treatment and retreatment of flares have solidified the belief that antibiotics are an effective suppressive (if not curative) therapy despite a lack of randomized controlled trials.4

This patient was treated with minocycline 100 mg bid. After 1 month, the rash had improved by 70%. At 3 months, it was completely clear, and treatment was discontinued.

This case was adapted from: Sessums MT, Ward KMH, Brodell R. Cutaneous eruption on chest and back. J Fam Pract. 2014;63:467-468.

This patient was given a diagnosis of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CRP) based on the clinical presentation.

CRP is characterized by centrally confluent and peripherally reticulated scaly brown plaques and papules that are cosmetically disfiguring.1 CRP is usually asymptomatic and primarily impacts young adults—especially teenagers.2,3 It affects both males and females and commonly occurs on the trunk.1-3 CRP is believed to be a disorder of keratinization. Malassezia furfur may induce CRP’s hyperproliferative epidermal changes, but systemic treatment that eliminates this organism does not clear CRP.3

A CRP diagnosis is made based on clinical presentation. The eruption usually begins as verrucous papules in the inframammary or epigastric region that enlarge to 4 to 5 mm in diameter and coalesce to form a confluent plaque with a peripheral reticulated pattern. CRP can extend over the back, chest, and abdomen to the neck, shoulders, and gluteal cleft. CRP does not affect the oral mucosa, and rarely involves flexural areas, which differentiates it from the similar looking acanthosis nigricans.2 Although most cases are asymptomatic, mild pruritus may occur.1,2

A skin biopsy is rarely necessary for making a CRP diagnosis, but histopathologic findings include papillomatosis, hyperkeratosis, variable acanthosis, follicular plugging, and sparse dermal inflammation.1,3

Systemic antibiotics, most commonly minocycline 100 mg bid for 30 days or doxycycline 100 mg bid for 30 days, are safe and effective for CRP.1,4 Sometimes treatment is extended for as long as 6 months. Although CRP usually responds to minocycline or doxycycline, it is believed that this is the result of these drugs’ anti-inflammatory—rather than antibiotic—properties.1,2,4 Azithromycin is an effective alternative therapy.2,4 There is a high rate of recurrence of CRP in patients after systemic antibiotics are discontinued.2 Uniform responses to treatment and retreatment of flares have solidified the belief that antibiotics are an effective suppressive (if not curative) therapy despite a lack of randomized controlled trials.4

This patient was treated with minocycline 100 mg bid. After 1 month, the rash had improved by 70%. At 3 months, it was completely clear, and treatment was discontinued.

This case was adapted from: Sessums MT, Ward KMH, Brodell R. Cutaneous eruption on chest and back. J Fam Pract. 2014;63:467-468.

1. Davis MD, Weenig RH, Camilleri MJ. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome): a minocycline-responsive dermatosis without evidence for yeast in pathogenesis. A study of 39 patients and a proposal of diagnostic criteria. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:287-293. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06955.x

2. Scheinfeld N. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: a review of the literature. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:305-313. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200607050-00004

3. Tamraz H, Raffoul M, Kurban M, et al. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: clinical and histopathological study of 10 cases from Lebanon. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:e119-e123. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04328.x

4. Jang HS, Oh CK, Cha JH, et al. Six cases of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis alleviated by various antibiotics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:652-655. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.112577

1. Davis MD, Weenig RH, Camilleri MJ. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome): a minocycline-responsive dermatosis without evidence for yeast in pathogenesis. A study of 39 patients and a proposal of diagnostic criteria. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:287-293. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06955.x

2. Scheinfeld N. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: a review of the literature. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:305-313. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200607050-00004

3. Tamraz H, Raffoul M, Kurban M, et al. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: clinical and histopathological study of 10 cases from Lebanon. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:e119-e123. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04328.x

4. Jang HS, Oh CK, Cha JH, et al. Six cases of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis alleviated by various antibiotics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:652-655. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.112577

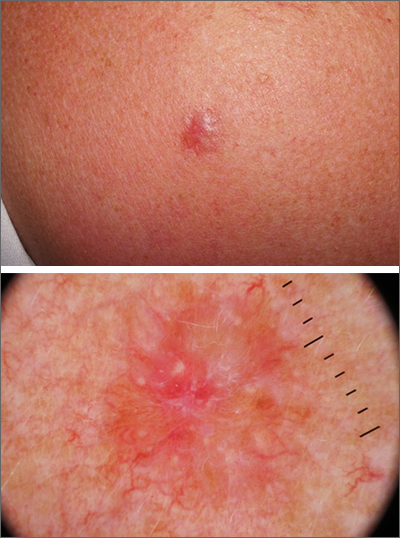

Nocturnally pruritic rash

A 74-YEAR-OLD WOMAN presented with a 3-day history of an intensely pruritic rash that was localized to her upper arms, upper chest between her breasts, and upper back. The pruritus was much worse at night while the patient was in bed. Symptoms did not improve with over-the-counter topical corticosteroids.

The patient had a history of atrial fibrillation (for which she was receiving chronic anticoagulation therapy), hypertension, an implanted pacemaker, depression, and Parkinson disease. Her medications included carbidopa-levodopa, fluoxetine, hydrochlorothiazide, metoprolol tartrate, naproxen, and warfarin. She had no known allergies. She reported that she was a nonsmoker and drank 1 glass of wine per week.

There were no recent changes in soaps, detergents, lotions, or makeup, nor did the patient have any bug bites or plant exposure. She shared a home with her spouse and several pets: a dog, a cat, and a Bantam-breed chicken. The patient’s husband, who slept in a different bedroom, had no rash. Recently, the cat had been bringing its captured prey of rabbits into the home.

Review of systems was negative for fever, chills, shortness of breath, cough, throat swelling, and rhinorrhea. Physical examination revealed red/pink macules and papules scattered over the upper arms (FIGURE 1), chest, and upper back. Many lesions were excoriated but had no active bleeding or vesicles. Under dermatoscope, no burrowing was found; however, a small (< 1 mm) creature was seen moving rapidly across the skin surface. The physician (CTW) captured and isolated the creature using a sterile lab cup.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Gamasoidosis

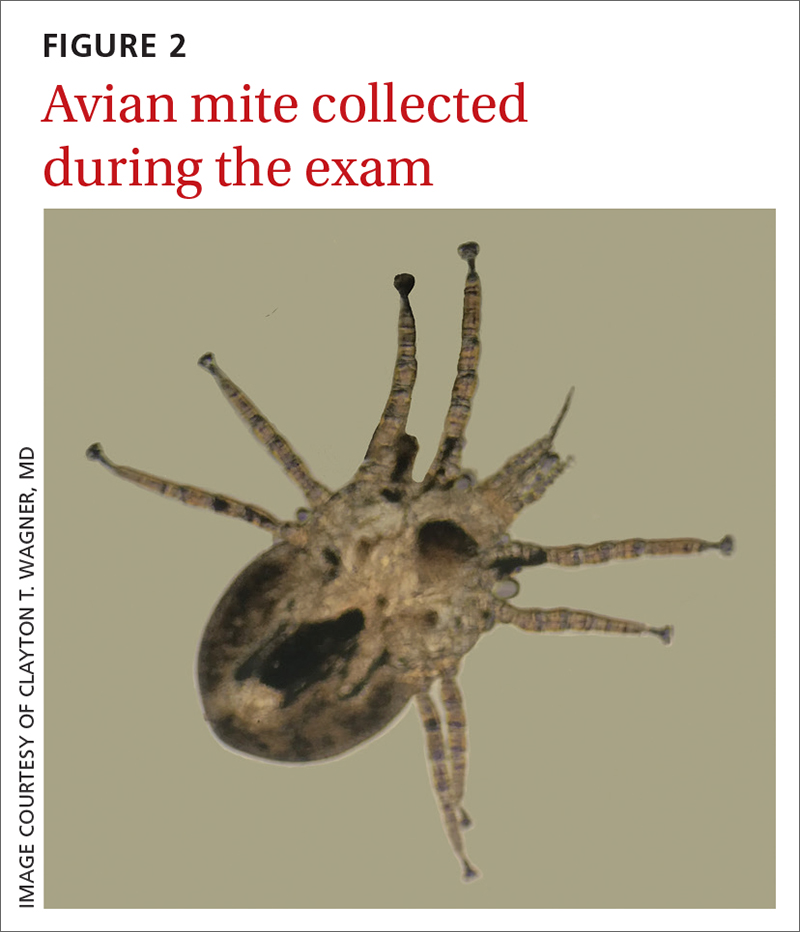

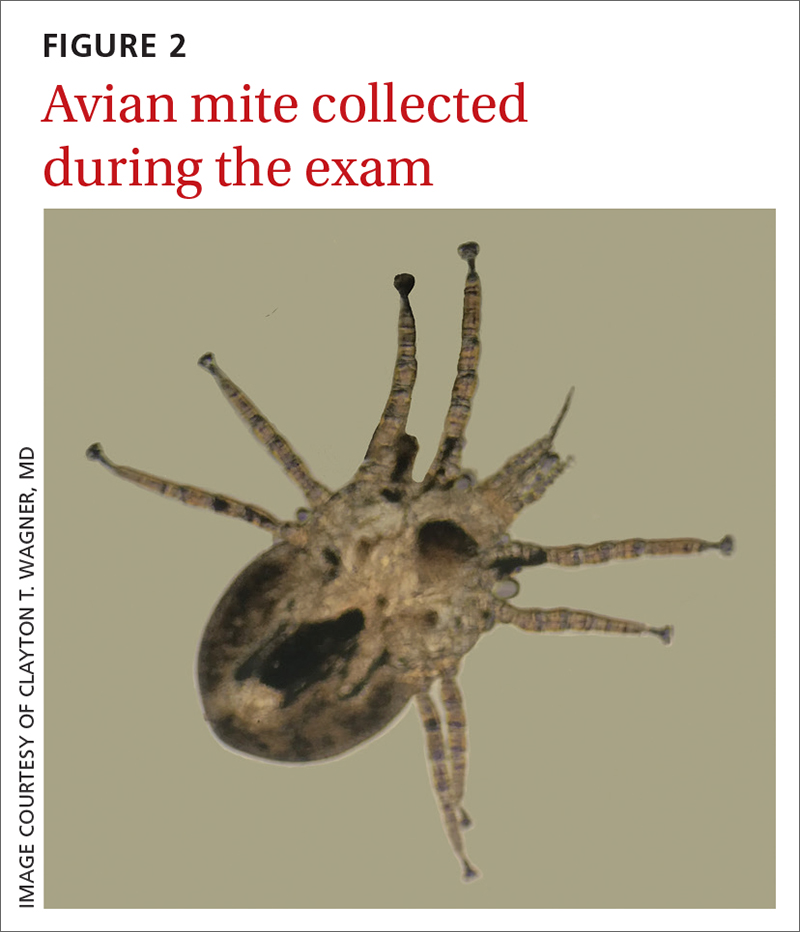

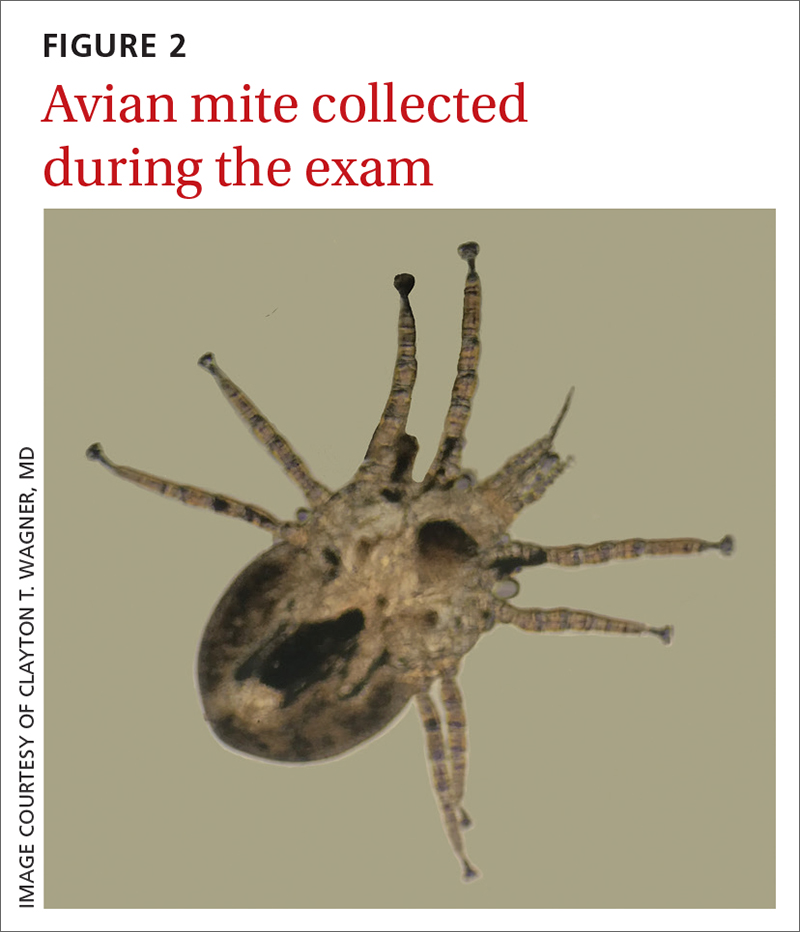

The collected sample (FIGURE 2) was examined and identified as an avian mite by a colleague who specializes in entomology, confirming the diagnosis of gamasoidosis.

Two genera of avian mites are responsible: Dermanyssus and Ornithonyssus. The most common culprits are the red poultry mite (D gallinae) and the northern fowl mite (O bursa). These small mites parasitize birds, such as poultry livestock, domesticated birds, and wild game birds. When unfed, the mite appears translucent brown and measures 0.3 to 0.7 mm in length, but after a blood meal, it appears red and increases in size to 1 mm. The mites tend to be active and feed at night and hide during the day.2 This explained the severe nighttime pruritus in this case.

Human infestation, although infrequent, can be a concern for those who work with poultry, or during the spring and summer seasons when young birds leave their nests and the mites migrate to find alternative hosts.3 The 1- to 2-mm erythematous maculopapules are often found with excoriations in covered areas.3,4 Unlike scabies, the genitalia and interdigital areas are spared.3,5

Differential for arthropod dermatoses

The differential diagnosis includes cimicosis, pulicosis, pediculosis corporis, and scabies.

Cimicosis is caused by bed bugs (from the insect Cimex genus). Bed bugs are oval and reddish brown, have 6 legs, and range in size from 1 to 7 mm. Most bed bugs hide in cracks or crevices of furniture and other surfaces (eg, bed frames, headboards, seams or holes of box springs or mattresses, or behind wallpaper, switch plates, and picture frames) by day and come out at night to feed on a sleeping host. Commonly, bed bugs will leave a series of bites grouped in rows (described as “breakfast, lunch, and dinner”). The bites can mimic urticaria, and bullous reactions may also occur.2

Continue to: Pulicosis

Pulicosis results from bites caused by a variety of flea species including, but not limited to, human, dog, oriental rat, sticktight, mouse, and chicken fleas. Fleas are small brown insects measuring about 2.5 mm in length, with flat sides and long hind legs. Their bites are most often arranged in a zigzag pattern around a host’s legs and waist. Hypersensitivity reactions may appear as papular urticaria, nodules, or bullae.2

Pediculosis corporis is caused by body lice. The adult louse is 2.5 to 3.5 mm in size, has 6 legs, and is a tan to greyish white color.6 Lice live in clothing, lay their eggs within the seams, and obtain blood meals from the host. Symptoms include generalized itching. The erythematous blue- and copper-colored macules, wheals, and lichenification can occur throughout the body, but spare the hands and feet. Secondary impetigo and furunculosis commonly occur.2

Scabies is caused by an oval mite that is ventrally flat, with dorsal spines. The mite is < 0.5 mm in size, appearing as a pinpoint of white. It burrows into its host’s skin, where it lives and lays eggs, causing pruritic papular lesions and ensuing excoriations. The mite burrows with a predilection for the finger web spaces, wrists, axillae, areolae, umbilicus, lower abdomen, genitals, and buttocks.2

Treatment involves a 3-step process

The mainstay of treatment is removal of the infested bird, decontamination of bedding and clothing, and use of oral antihistamines and topical corticosteroids.1,3,5 Bedding and clothing should be washed. Carpets, rugs, and curtains should be vacuumed and the vacuum bag placed in a sealed bag in the freezer for several hours before it can be thrown away. Eggs, larvae, nymphs, and adults are killed at 55 to 60 °F. Because humans are only incidental hosts and mites do not reproduce on them, the use of scabicidal agents, such as permethrin, is controversial.

Our patient was treated with permethrin cream before definitive identification of the mite. Once the mite was identified, the chicken was removed from the home and the patient’s bedding and clothing were decontaminated. The patient continued to apply over-the-counter topical steroids and take oral antihistamines for several more days after the chicken was removed from the home.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to acknowledge Patrick Liesch of the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Department of Entomology, Insect Diagnostic Lab, for his help in identifying the avian mite.

1. Leib AE, Anderson BE. Pruritic dermatitis caused by bird mite infestation. Cutis. 2016;97:E6-E8.

2. Collgros H, Iglesias-Sancho M, Aldunce MJ, et al. Dermanyssus gallinae (chicken mite): an underdiagnosed environmental infestation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:374-377. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2012.04434.x

3. Baselga E, Drolet BA, Esterly NB. Avian mite dermatitis. Pediatrics. 1996;97:743-745.

4. James WD, Elston DM, Treat J, et al, eds. Andrews Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

Dermanyssus gallinae infestation: an unusual cause of scalp pruritus treated with permethrin shampoo. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:319-321. doi: 10.3109/09546630903287437

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites. Reviewed September 12, 2019. Accessed August 4, 2022. www.cdc.gov/parasites/lice/body/biology.html

A 74-YEAR-OLD WOMAN presented with a 3-day history of an intensely pruritic rash that was localized to her upper arms, upper chest between her breasts, and upper back. The pruritus was much worse at night while the patient was in bed. Symptoms did not improve with over-the-counter topical corticosteroids.

The patient had a history of atrial fibrillation (for which she was receiving chronic anticoagulation therapy), hypertension, an implanted pacemaker, depression, and Parkinson disease. Her medications included carbidopa-levodopa, fluoxetine, hydrochlorothiazide, metoprolol tartrate, naproxen, and warfarin. She had no known allergies. She reported that she was a nonsmoker and drank 1 glass of wine per week.

There were no recent changes in soaps, detergents, lotions, or makeup, nor did the patient have any bug bites or plant exposure. She shared a home with her spouse and several pets: a dog, a cat, and a Bantam-breed chicken. The patient’s husband, who slept in a different bedroom, had no rash. Recently, the cat had been bringing its captured prey of rabbits into the home.

Review of systems was negative for fever, chills, shortness of breath, cough, throat swelling, and rhinorrhea. Physical examination revealed red/pink macules and papules scattered over the upper arms (FIGURE 1), chest, and upper back. Many lesions were excoriated but had no active bleeding or vesicles. Under dermatoscope, no burrowing was found; however, a small (< 1 mm) creature was seen moving rapidly across the skin surface. The physician (CTW) captured and isolated the creature using a sterile lab cup.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Gamasoidosis

The collected sample (FIGURE 2) was examined and identified as an avian mite by a colleague who specializes in entomology, confirming the diagnosis of gamasoidosis.

Two genera of avian mites are responsible: Dermanyssus and Ornithonyssus. The most common culprits are the red poultry mite (D gallinae) and the northern fowl mite (O bursa). These small mites parasitize birds, such as poultry livestock, domesticated birds, and wild game birds. When unfed, the mite appears translucent brown and measures 0.3 to 0.7 mm in length, but after a blood meal, it appears red and increases in size to 1 mm. The mites tend to be active and feed at night and hide during the day.2 This explained the severe nighttime pruritus in this case.

Human infestation, although infrequent, can be a concern for those who work with poultry, or during the spring and summer seasons when young birds leave their nests and the mites migrate to find alternative hosts.3 The 1- to 2-mm erythematous maculopapules are often found with excoriations in covered areas.3,4 Unlike scabies, the genitalia and interdigital areas are spared.3,5

Differential for arthropod dermatoses

The differential diagnosis includes cimicosis, pulicosis, pediculosis corporis, and scabies.

Cimicosis is caused by bed bugs (from the insect Cimex genus). Bed bugs are oval and reddish brown, have 6 legs, and range in size from 1 to 7 mm. Most bed bugs hide in cracks or crevices of furniture and other surfaces (eg, bed frames, headboards, seams or holes of box springs or mattresses, or behind wallpaper, switch plates, and picture frames) by day and come out at night to feed on a sleeping host. Commonly, bed bugs will leave a series of bites grouped in rows (described as “breakfast, lunch, and dinner”). The bites can mimic urticaria, and bullous reactions may also occur.2

Continue to: Pulicosis

Pulicosis results from bites caused by a variety of flea species including, but not limited to, human, dog, oriental rat, sticktight, mouse, and chicken fleas. Fleas are small brown insects measuring about 2.5 mm in length, with flat sides and long hind legs. Their bites are most often arranged in a zigzag pattern around a host’s legs and waist. Hypersensitivity reactions may appear as papular urticaria, nodules, or bullae.2

Pediculosis corporis is caused by body lice. The adult louse is 2.5 to 3.5 mm in size, has 6 legs, and is a tan to greyish white color.6 Lice live in clothing, lay their eggs within the seams, and obtain blood meals from the host. Symptoms include generalized itching. The erythematous blue- and copper-colored macules, wheals, and lichenification can occur throughout the body, but spare the hands and feet. Secondary impetigo and furunculosis commonly occur.2

Scabies is caused by an oval mite that is ventrally flat, with dorsal spines. The mite is < 0.5 mm in size, appearing as a pinpoint of white. It burrows into its host’s skin, where it lives and lays eggs, causing pruritic papular lesions and ensuing excoriations. The mite burrows with a predilection for the finger web spaces, wrists, axillae, areolae, umbilicus, lower abdomen, genitals, and buttocks.2

Treatment involves a 3-step process

The mainstay of treatment is removal of the infested bird, decontamination of bedding and clothing, and use of oral antihistamines and topical corticosteroids.1,3,5 Bedding and clothing should be washed. Carpets, rugs, and curtains should be vacuumed and the vacuum bag placed in a sealed bag in the freezer for several hours before it can be thrown away. Eggs, larvae, nymphs, and adults are killed at 55 to 60 °F. Because humans are only incidental hosts and mites do not reproduce on them, the use of scabicidal agents, such as permethrin, is controversial.

Our patient was treated with permethrin cream before definitive identification of the mite. Once the mite was identified, the chicken was removed from the home and the patient’s bedding and clothing were decontaminated. The patient continued to apply over-the-counter topical steroids and take oral antihistamines for several more days after the chicken was removed from the home.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to acknowledge Patrick Liesch of the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Department of Entomology, Insect Diagnostic Lab, for his help in identifying the avian mite.

A 74-YEAR-OLD WOMAN presented with a 3-day history of an intensely pruritic rash that was localized to her upper arms, upper chest between her breasts, and upper back. The pruritus was much worse at night while the patient was in bed. Symptoms did not improve with over-the-counter topical corticosteroids.

The patient had a history of atrial fibrillation (for which she was receiving chronic anticoagulation therapy), hypertension, an implanted pacemaker, depression, and Parkinson disease. Her medications included carbidopa-levodopa, fluoxetine, hydrochlorothiazide, metoprolol tartrate, naproxen, and warfarin. She had no known allergies. She reported that she was a nonsmoker and drank 1 glass of wine per week.

There were no recent changes in soaps, detergents, lotions, or makeup, nor did the patient have any bug bites or plant exposure. She shared a home with her spouse and several pets: a dog, a cat, and a Bantam-breed chicken. The patient’s husband, who slept in a different bedroom, had no rash. Recently, the cat had been bringing its captured prey of rabbits into the home.

Review of systems was negative for fever, chills, shortness of breath, cough, throat swelling, and rhinorrhea. Physical examination revealed red/pink macules and papules scattered over the upper arms (FIGURE 1), chest, and upper back. Many lesions were excoriated but had no active bleeding or vesicles. Under dermatoscope, no burrowing was found; however, a small (< 1 mm) creature was seen moving rapidly across the skin surface. The physician (CTW) captured and isolated the creature using a sterile lab cup.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Gamasoidosis

The collected sample (FIGURE 2) was examined and identified as an avian mite by a colleague who specializes in entomology, confirming the diagnosis of gamasoidosis.

Two genera of avian mites are responsible: Dermanyssus and Ornithonyssus. The most common culprits are the red poultry mite (D gallinae) and the northern fowl mite (O bursa). These small mites parasitize birds, such as poultry livestock, domesticated birds, and wild game birds. When unfed, the mite appears translucent brown and measures 0.3 to 0.7 mm in length, but after a blood meal, it appears red and increases in size to 1 mm. The mites tend to be active and feed at night and hide during the day.2 This explained the severe nighttime pruritus in this case.

Human infestation, although infrequent, can be a concern for those who work with poultry, or during the spring and summer seasons when young birds leave their nests and the mites migrate to find alternative hosts.3 The 1- to 2-mm erythematous maculopapules are often found with excoriations in covered areas.3,4 Unlike scabies, the genitalia and interdigital areas are spared.3,5

Differential for arthropod dermatoses

The differential diagnosis includes cimicosis, pulicosis, pediculosis corporis, and scabies.

Cimicosis is caused by bed bugs (from the insect Cimex genus). Bed bugs are oval and reddish brown, have 6 legs, and range in size from 1 to 7 mm. Most bed bugs hide in cracks or crevices of furniture and other surfaces (eg, bed frames, headboards, seams or holes of box springs or mattresses, or behind wallpaper, switch plates, and picture frames) by day and come out at night to feed on a sleeping host. Commonly, bed bugs will leave a series of bites grouped in rows (described as “breakfast, lunch, and dinner”). The bites can mimic urticaria, and bullous reactions may also occur.2

Continue to: Pulicosis

Pulicosis results from bites caused by a variety of flea species including, but not limited to, human, dog, oriental rat, sticktight, mouse, and chicken fleas. Fleas are small brown insects measuring about 2.5 mm in length, with flat sides and long hind legs. Their bites are most often arranged in a zigzag pattern around a host’s legs and waist. Hypersensitivity reactions may appear as papular urticaria, nodules, or bullae.2

Pediculosis corporis is caused by body lice. The adult louse is 2.5 to 3.5 mm in size, has 6 legs, and is a tan to greyish white color.6 Lice live in clothing, lay their eggs within the seams, and obtain blood meals from the host. Symptoms include generalized itching. The erythematous blue- and copper-colored macules, wheals, and lichenification can occur throughout the body, but spare the hands and feet. Secondary impetigo and furunculosis commonly occur.2

Scabies is caused by an oval mite that is ventrally flat, with dorsal spines. The mite is < 0.5 mm in size, appearing as a pinpoint of white. It burrows into its host’s skin, where it lives and lays eggs, causing pruritic papular lesions and ensuing excoriations. The mite burrows with a predilection for the finger web spaces, wrists, axillae, areolae, umbilicus, lower abdomen, genitals, and buttocks.2

Treatment involves a 3-step process

The mainstay of treatment is removal of the infested bird, decontamination of bedding and clothing, and use of oral antihistamines and topical corticosteroids.1,3,5 Bedding and clothing should be washed. Carpets, rugs, and curtains should be vacuumed and the vacuum bag placed in a sealed bag in the freezer for several hours before it can be thrown away. Eggs, larvae, nymphs, and adults are killed at 55 to 60 °F. Because humans are only incidental hosts and mites do not reproduce on them, the use of scabicidal agents, such as permethrin, is controversial.

Our patient was treated with permethrin cream before definitive identification of the mite. Once the mite was identified, the chicken was removed from the home and the patient’s bedding and clothing were decontaminated. The patient continued to apply over-the-counter topical steroids and take oral antihistamines for several more days after the chicken was removed from the home.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to acknowledge Patrick Liesch of the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Department of Entomology, Insect Diagnostic Lab, for his help in identifying the avian mite.

1. Leib AE, Anderson BE. Pruritic dermatitis caused by bird mite infestation. Cutis. 2016;97:E6-E8.

2. Collgros H, Iglesias-Sancho M, Aldunce MJ, et al. Dermanyssus gallinae (chicken mite): an underdiagnosed environmental infestation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:374-377. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2012.04434.x

3. Baselga E, Drolet BA, Esterly NB. Avian mite dermatitis. Pediatrics. 1996;97:743-745.

4. James WD, Elston DM, Treat J, et al, eds. Andrews Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

Dermanyssus gallinae infestation: an unusual cause of scalp pruritus treated with permethrin shampoo. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:319-321. doi: 10.3109/09546630903287437

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites. Reviewed September 12, 2019. Accessed August 4, 2022. www.cdc.gov/parasites/lice/body/biology.html

1. Leib AE, Anderson BE. Pruritic dermatitis caused by bird mite infestation. Cutis. 2016;97:E6-E8.

2. Collgros H, Iglesias-Sancho M, Aldunce MJ, et al. Dermanyssus gallinae (chicken mite): an underdiagnosed environmental infestation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:374-377. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2012.04434.x

3. Baselga E, Drolet BA, Esterly NB. Avian mite dermatitis. Pediatrics. 1996;97:743-745.

4. James WD, Elston DM, Treat J, et al, eds. Andrews Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

Dermanyssus gallinae infestation: an unusual cause of scalp pruritus treated with permethrin shampoo. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:319-321. doi: 10.3109/09546630903287437

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites. Reviewed September 12, 2019. Accessed August 4, 2022. www.cdc.gov/parasites/lice/body/biology.html

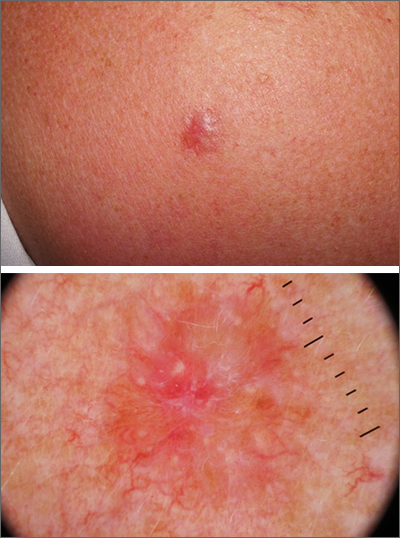

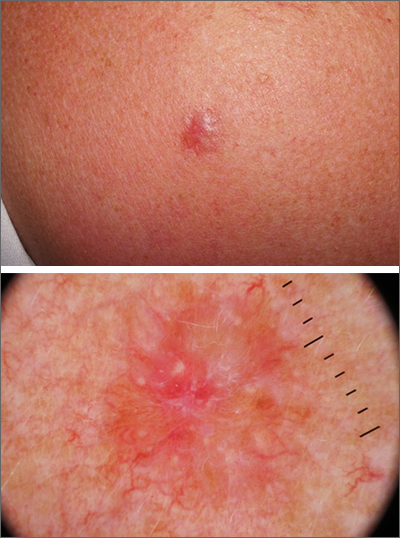

Shoulder lesion

A punch biopsy of the lesion was performed and the results were consistent with a dermatofibroma, which is a benign growth.

Dermatofibromas may manifest as a pink papule on fair-skinned individuals or a darker brown papule in patients of color. Clinically, the texture can be helpful to discern an etiology—dermatofibromas may dimple when pinched laterally, while melanocytic nevi or melanomas tend to be somewhat softer on palpation. Cutaneous sarcoma, while exceedingly rare, may be firmer and chaotic, and varied with multiple colors and topographical changes.

The dermoscopic pattern of a dermatofibroma includes central scar-like areas, a peripheral pigment network, occasional shiny white lines, and confluent circular brown macules. Other less frequent dermoscopic structures may also be seen. A prospective study of the dermoscopic morphology of 412 dermatofibromas found 10 distinct dermoscopic patterns, but also noted that 25% of the dermatofibromas exhibited an atypical pattern.1 Atypical pigment, multiple scar-like areas, and dotted vessels can occur in a dermatofibroma, as well as in a Spitz nevus, and melanoma. Thus, such findings should prompt a biopsy.

Dermatofibromas are safe to observe, but they can be surgically excised if they cause pain or cosmetic concerns.

This patient was reassured to know that the lesion would not require surgical intervention and was unlikely to enlarge or change significantly over time.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Zaballos P, Puig S, Llambrich A, Malvehy J. Dermoscopy of dermatofibromas: a prospective morphological study of 412 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:75-83. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2007.8

A punch biopsy of the lesion was performed and the results were consistent with a dermatofibroma, which is a benign growth.

Dermatofibromas may manifest as a pink papule on fair-skinned individuals or a darker brown papule in patients of color. Clinically, the texture can be helpful to discern an etiology—dermatofibromas may dimple when pinched laterally, while melanocytic nevi or melanomas tend to be somewhat softer on palpation. Cutaneous sarcoma, while exceedingly rare, may be firmer and chaotic, and varied with multiple colors and topographical changes.

The dermoscopic pattern of a dermatofibroma includes central scar-like areas, a peripheral pigment network, occasional shiny white lines, and confluent circular brown macules. Other less frequent dermoscopic structures may also be seen. A prospective study of the dermoscopic morphology of 412 dermatofibromas found 10 distinct dermoscopic patterns, but also noted that 25% of the dermatofibromas exhibited an atypical pattern.1 Atypical pigment, multiple scar-like areas, and dotted vessels can occur in a dermatofibroma, as well as in a Spitz nevus, and melanoma. Thus, such findings should prompt a biopsy.

Dermatofibromas are safe to observe, but they can be surgically excised if they cause pain or cosmetic concerns.

This patient was reassured to know that the lesion would not require surgical intervention and was unlikely to enlarge or change significantly over time.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

A punch biopsy of the lesion was performed and the results were consistent with a dermatofibroma, which is a benign growth.

Dermatofibromas may manifest as a pink papule on fair-skinned individuals or a darker brown papule in patients of color. Clinically, the texture can be helpful to discern an etiology—dermatofibromas may dimple when pinched laterally, while melanocytic nevi or melanomas tend to be somewhat softer on palpation. Cutaneous sarcoma, while exceedingly rare, may be firmer and chaotic, and varied with multiple colors and topographical changes.

The dermoscopic pattern of a dermatofibroma includes central scar-like areas, a peripheral pigment network, occasional shiny white lines, and confluent circular brown macules. Other less frequent dermoscopic structures may also be seen. A prospective study of the dermoscopic morphology of 412 dermatofibromas found 10 distinct dermoscopic patterns, but also noted that 25% of the dermatofibromas exhibited an atypical pattern.1 Atypical pigment, multiple scar-like areas, and dotted vessels can occur in a dermatofibroma, as well as in a Spitz nevus, and melanoma. Thus, such findings should prompt a biopsy.

Dermatofibromas are safe to observe, but they can be surgically excised if they cause pain or cosmetic concerns.

This patient was reassured to know that the lesion would not require surgical intervention and was unlikely to enlarge or change significantly over time.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Zaballos P, Puig S, Llambrich A, Malvehy J. Dermoscopy of dermatofibromas: a prospective morphological study of 412 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:75-83. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2007.8

1. Zaballos P, Puig S, Llambrich A, Malvehy J. Dermoscopy of dermatofibromas: a prospective morphological study of 412 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:75-83. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2007.8

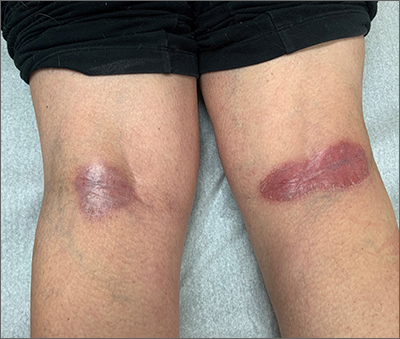

Leg rash

Punch biopsies for standard pathology and direct immunofluorescence were performed and ruled out vesiculobullous disease. Further conversation with the patient revealed that this was a phototoxic drug eruption that resulted from a medication mix-up. The patient had intended to treat an eczema flare with a topical steroid but had inadvertently applied 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), which he had left over from a previous bout of actinic keratosis. While selective to precancerous cells with rapid DNA replication, 5-FU can trigger a significant photodermatitis when applied to heavily sun-exposed skin.

Phototoxic skin reactions can be an adverse result of multiple systemic and topical therapies. Common systemic examples include amiodarone, chlorpromazine, doxycycline, hydrochlorothiazide, isotretinoin, nalidixic acid, naproxen, piroxicam, tetracycline, thioridazine, vemurafenib, and voriconazole.1 Topical examples include retinoids, levulinic acid, and 5-FU. Treatment requires that the patient stop the offending medication and use photoprotection. The patient followed this protocol and his erosions resolved over the course of a few weeks.

This case demonstrates that topical therapies, like systemic medications, can have chemical names that are confusing to patients. Further complicating matters can be the practice of folding metal tubes of cream over their life of use, thus obscuring the label.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Blakely KM, Drucker AM, Rosen CF. Drug-induced photosensitivity-an update: culprit drugs, prevention, and management. Drug Saf. 2019;42:827-847. doi: 10.1007/s40264-019-00806-5

Punch biopsies for standard pathology and direct immunofluorescence were performed and ruled out vesiculobullous disease. Further conversation with the patient revealed that this was a phototoxic drug eruption that resulted from a medication mix-up. The patient had intended to treat an eczema flare with a topical steroid but had inadvertently applied 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), which he had left over from a previous bout of actinic keratosis. While selective to precancerous cells with rapid DNA replication, 5-FU can trigger a significant photodermatitis when applied to heavily sun-exposed skin.

Phototoxic skin reactions can be an adverse result of multiple systemic and topical therapies. Common systemic examples include amiodarone, chlorpromazine, doxycycline, hydrochlorothiazide, isotretinoin, nalidixic acid, naproxen, piroxicam, tetracycline, thioridazine, vemurafenib, and voriconazole.1 Topical examples include retinoids, levulinic acid, and 5-FU. Treatment requires that the patient stop the offending medication and use photoprotection. The patient followed this protocol and his erosions resolved over the course of a few weeks.

This case demonstrates that topical therapies, like systemic medications, can have chemical names that are confusing to patients. Further complicating matters can be the practice of folding metal tubes of cream over their life of use, thus obscuring the label.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Punch biopsies for standard pathology and direct immunofluorescence were performed and ruled out vesiculobullous disease. Further conversation with the patient revealed that this was a phototoxic drug eruption that resulted from a medication mix-up. The patient had intended to treat an eczema flare with a topical steroid but had inadvertently applied 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), which he had left over from a previous bout of actinic keratosis. While selective to precancerous cells with rapid DNA replication, 5-FU can trigger a significant photodermatitis when applied to heavily sun-exposed skin.

Phototoxic skin reactions can be an adverse result of multiple systemic and topical therapies. Common systemic examples include amiodarone, chlorpromazine, doxycycline, hydrochlorothiazide, isotretinoin, nalidixic acid, naproxen, piroxicam, tetracycline, thioridazine, vemurafenib, and voriconazole.1 Topical examples include retinoids, levulinic acid, and 5-FU. Treatment requires that the patient stop the offending medication and use photoprotection. The patient followed this protocol and his erosions resolved over the course of a few weeks.

This case demonstrates that topical therapies, like systemic medications, can have chemical names that are confusing to patients. Further complicating matters can be the practice of folding metal tubes of cream over their life of use, thus obscuring the label.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Blakely KM, Drucker AM, Rosen CF. Drug-induced photosensitivity-an update: culprit drugs, prevention, and management. Drug Saf. 2019;42:827-847. doi: 10.1007/s40264-019-00806-5

1. Blakely KM, Drucker AM, Rosen CF. Drug-induced photosensitivity-an update: culprit drugs, prevention, and management. Drug Saf. 2019;42:827-847. doi: 10.1007/s40264-019-00806-5

Toenail trauma

The patient’s initial injury was probably a subungual hematoma, which can take 12 to 18 months to resolve (the time it takes for a new toenail to grow). However, the precipitating trauma likely created an opportunity for fungal elements to invade the nail plate, resulting in the current complaint of superficial onychomycosis.

Onychomycosis is a frequently seen condition with increasing prevalence in older patients. It has several clinical presentations: Superficial onychomycosis manifests with chalky white changes on the surface of the nail. Distal subungual onychomycosis develops at the distal aspect of the nail with thickening and subungual debris. Proximal subungual onychomycosis occurs in the proximal aspect of the nail.

Although often asymptomatic, onychomycosis can cause thickening of the nails and development of subsequent deformity or pincer nails (which painfully “pinch” the underlying skin). It is especially concerning in patients with diabetes or peripheral neuropathy, in whom the abnormal thickness and shape of the nails can lead to microtrauma at the proximal and lateral attachments of the nail. These patients have an increased risk of secondary infection, possible complications, and even, for some, amputation.

If the patient is asymptomatic, and does not have diabetes, neuropathy, or other risk factors, treatment is not required. For those who would benefit from treatment, it is usually safe and inexpensive with the current generation of oral antifungal medications.

Some recommend confirmatory testing before treatment intiation,1 but the low adverse effect profile of terbinafine and its current cost below $10/month2 make empiric treatment safe and cost effective in most cases.3 If needed, and with access to microscopy, a potassium hydroxide (KOH) prep can be performed on scrapings from the affected portions of the nail. If that is not available, scrapings or clippings can be sent to the lab for KOH and periodic acid-Schiff staining.

The US Food and Drug Administration previously recommended follow-up liver enzyme tests if terbinafine is used for more than 6 weeks. (Fingernails require only 6 weeks of treatment, but toenails grow more slowly and require 12 weeks of treatment.) However, research has demonstrated that hepatotoxicity risk is extremely low and transaminase elevations are rare.4 In the rare cases that liver dysfunction has occurred, patients developed symptoms of jaundice, malaise, dark urine, or pruritis.4

This patient was counseled regarding the fungal nature of onychomycosis and the general safety of a 90-day course of oral terbinafine 250 mg/d—provided he did not have underlying liver or kidney disease or leukopenia. He reported that he had not had any blood work performed in the past year but was due for his annual wellness evaluation, at which he would discuss his overall health with his primary care provider, obtain baseline blood testing, and determine whether to proceed with treatment. He was advised that if, after starting treatment, he developed any symptoms of jaundice, dark urine, or other difficulties, he should report them to his care team.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

- Frazier WT, Santiago-Delgado ZM, Stupka KC 2nd. Onychomycosis: rapid evidence review. Am Fam Physician. 2021;104:359-367.

- Terbinafine. GoodRx. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.goodrx.com/terbinafine

- Mikailov A, Cohen J, Joyce C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of confirmatory testing before treatment of onychomycosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:276-281. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.4190

- Sun CW, Hsu S. Terbinafine: safety profile and monitoring in treatment of dermatophyte infections. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:e13111. doi: 10.1111/dth.13111

The patient’s initial injury was probably a subungual hematoma, which can take 12 to 18 months to resolve (the time it takes for a new toenail to grow). However, the precipitating trauma likely created an opportunity for fungal elements to invade the nail plate, resulting in the current complaint of superficial onychomycosis.

Onychomycosis is a frequently seen condition with increasing prevalence in older patients. It has several clinical presentations: Superficial onychomycosis manifests with chalky white changes on the surface of the nail. Distal subungual onychomycosis develops at the distal aspect of the nail with thickening and subungual debris. Proximal subungual onychomycosis occurs in the proximal aspect of the nail.

Although often asymptomatic, onychomycosis can cause thickening of the nails and development of subsequent deformity or pincer nails (which painfully “pinch” the underlying skin). It is especially concerning in patients with diabetes or peripheral neuropathy, in whom the abnormal thickness and shape of the nails can lead to microtrauma at the proximal and lateral attachments of the nail. These patients have an increased risk of secondary infection, possible complications, and even, for some, amputation.

If the patient is asymptomatic, and does not have diabetes, neuropathy, or other risk factors, treatment is not required. For those who would benefit from treatment, it is usually safe and inexpensive with the current generation of oral antifungal medications.

Some recommend confirmatory testing before treatment intiation,1 but the low adverse effect profile of terbinafine and its current cost below $10/month2 make empiric treatment safe and cost effective in most cases.3 If needed, and with access to microscopy, a potassium hydroxide (KOH) prep can be performed on scrapings from the affected portions of the nail. If that is not available, scrapings or clippings can be sent to the lab for KOH and periodic acid-Schiff staining.

The US Food and Drug Administration previously recommended follow-up liver enzyme tests if terbinafine is used for more than 6 weeks. (Fingernails require only 6 weeks of treatment, but toenails grow more slowly and require 12 weeks of treatment.) However, research has demonstrated that hepatotoxicity risk is extremely low and transaminase elevations are rare.4 In the rare cases that liver dysfunction has occurred, patients developed symptoms of jaundice, malaise, dark urine, or pruritis.4

This patient was counseled regarding the fungal nature of onychomycosis and the general safety of a 90-day course of oral terbinafine 250 mg/d—provided he did not have underlying liver or kidney disease or leukopenia. He reported that he had not had any blood work performed in the past year but was due for his annual wellness evaluation, at which he would discuss his overall health with his primary care provider, obtain baseline blood testing, and determine whether to proceed with treatment. He was advised that if, after starting treatment, he developed any symptoms of jaundice, dark urine, or other difficulties, he should report them to his care team.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

The patient’s initial injury was probably a subungual hematoma, which can take 12 to 18 months to resolve (the time it takes for a new toenail to grow). However, the precipitating trauma likely created an opportunity for fungal elements to invade the nail plate, resulting in the current complaint of superficial onychomycosis.

Onychomycosis is a frequently seen condition with increasing prevalence in older patients. It has several clinical presentations: Superficial onychomycosis manifests with chalky white changes on the surface of the nail. Distal subungual onychomycosis develops at the distal aspect of the nail with thickening and subungual debris. Proximal subungual onychomycosis occurs in the proximal aspect of the nail.

Although often asymptomatic, onychomycosis can cause thickening of the nails and development of subsequent deformity or pincer nails (which painfully “pinch” the underlying skin). It is especially concerning in patients with diabetes or peripheral neuropathy, in whom the abnormal thickness and shape of the nails can lead to microtrauma at the proximal and lateral attachments of the nail. These patients have an increased risk of secondary infection, possible complications, and even, for some, amputation.

If the patient is asymptomatic, and does not have diabetes, neuropathy, or other risk factors, treatment is not required. For those who would benefit from treatment, it is usually safe and inexpensive with the current generation of oral antifungal medications.

Some recommend confirmatory testing before treatment intiation,1 but the low adverse effect profile of terbinafine and its current cost below $10/month2 make empiric treatment safe and cost effective in most cases.3 If needed, and with access to microscopy, a potassium hydroxide (KOH) prep can be performed on scrapings from the affected portions of the nail. If that is not available, scrapings or clippings can be sent to the lab for KOH and periodic acid-Schiff staining.

The US Food and Drug Administration previously recommended follow-up liver enzyme tests if terbinafine is used for more than 6 weeks. (Fingernails require only 6 weeks of treatment, but toenails grow more slowly and require 12 weeks of treatment.) However, research has demonstrated that hepatotoxicity risk is extremely low and transaminase elevations are rare.4 In the rare cases that liver dysfunction has occurred, patients developed symptoms of jaundice, malaise, dark urine, or pruritis.4

This patient was counseled regarding the fungal nature of onychomycosis and the general safety of a 90-day course of oral terbinafine 250 mg/d—provided he did not have underlying liver or kidney disease or leukopenia. He reported that he had not had any blood work performed in the past year but was due for his annual wellness evaluation, at which he would discuss his overall health with his primary care provider, obtain baseline blood testing, and determine whether to proceed with treatment. He was advised that if, after starting treatment, he developed any symptoms of jaundice, dark urine, or other difficulties, he should report them to his care team.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

- Frazier WT, Santiago-Delgado ZM, Stupka KC 2nd. Onychomycosis: rapid evidence review. Am Fam Physician. 2021;104:359-367.

- Terbinafine. GoodRx. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.goodrx.com/terbinafine

- Mikailov A, Cohen J, Joyce C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of confirmatory testing before treatment of onychomycosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:276-281. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.4190

- Sun CW, Hsu S. Terbinafine: safety profile and monitoring in treatment of dermatophyte infections. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:e13111. doi: 10.1111/dth.13111

- Frazier WT, Santiago-Delgado ZM, Stupka KC 2nd. Onychomycosis: rapid evidence review. Am Fam Physician. 2021;104:359-367.

- Terbinafine. GoodRx. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.goodrx.com/terbinafine

- Mikailov A, Cohen J, Joyce C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of confirmatory testing before treatment of onychomycosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:276-281. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.4190

- Sun CW, Hsu S. Terbinafine: safety profile and monitoring in treatment of dermatophyte infections. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32:e13111. doi: 10.1111/dth.13111

Spotted white fingernails

White nail changes are broadly called leukonychia: “leuko” meaning white and “nychia” referring to the nail. Scattered or single asymptomatic cloudy white nail lesions occurring without other associated skin or nail disorders are more specifically called punctate leukonychia.

Punctate leukonychia is theorized to be caused by trauma at the proximal nail matrix, affecting the developing nail.1 The trauma may result from aggressive nail care practices or damage to the cuticle. In many cases, there is no history of known trauma. For this patient with multiple lesions, who performed manual work, multiple small traumas may have induced the punctate leukonychia.

Other causes of leukonychia include superficial onychomycosis (in which discoloration may be whiter than the usual yellow-brown), renal disease, and arsenic toxicity.1 Arsenic toxicity causes transverse leukonychia in a band-like fashion, since it is a systemic insult to the growing nails. Longitudinal leukonychia is due to a more localized insult to the nail matrix, causing the white lines to grow out with the nail along the axis of the digit. Other than avoiding trauma, there is no treatment needed or recommended for punctate leukonychia.

The patient was counseled on the benign nature of his punctate leukonychia and assured that no treatment was necessary.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Iorizzo M, Starace M, Pasch MC. Leukonychia: what can white nails tell us? Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:177-193. doi: 10.1007/s40257-022-00671-6

White nail changes are broadly called leukonychia: “leuko” meaning white and “nychia” referring to the nail. Scattered or single asymptomatic cloudy white nail lesions occurring without other associated skin or nail disorders are more specifically called punctate leukonychia.

Punctate leukonychia is theorized to be caused by trauma at the proximal nail matrix, affecting the developing nail.1 The trauma may result from aggressive nail care practices or damage to the cuticle. In many cases, there is no history of known trauma. For this patient with multiple lesions, who performed manual work, multiple small traumas may have induced the punctate leukonychia.

Other causes of leukonychia include superficial onychomycosis (in which discoloration may be whiter than the usual yellow-brown), renal disease, and arsenic toxicity.1 Arsenic toxicity causes transverse leukonychia in a band-like fashion, since it is a systemic insult to the growing nails. Longitudinal leukonychia is due to a more localized insult to the nail matrix, causing the white lines to grow out with the nail along the axis of the digit. Other than avoiding trauma, there is no treatment needed or recommended for punctate leukonychia.

The patient was counseled on the benign nature of his punctate leukonychia and assured that no treatment was necessary.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

White nail changes are broadly called leukonychia: “leuko” meaning white and “nychia” referring to the nail. Scattered or single asymptomatic cloudy white nail lesions occurring without other associated skin or nail disorders are more specifically called punctate leukonychia.

Punctate leukonychia is theorized to be caused by trauma at the proximal nail matrix, affecting the developing nail.1 The trauma may result from aggressive nail care practices or damage to the cuticle. In many cases, there is no history of known trauma. For this patient with multiple lesions, who performed manual work, multiple small traumas may have induced the punctate leukonychia.

Other causes of leukonychia include superficial onychomycosis (in which discoloration may be whiter than the usual yellow-brown), renal disease, and arsenic toxicity.1 Arsenic toxicity causes transverse leukonychia in a band-like fashion, since it is a systemic insult to the growing nails. Longitudinal leukonychia is due to a more localized insult to the nail matrix, causing the white lines to grow out with the nail along the axis of the digit. Other than avoiding trauma, there is no treatment needed or recommended for punctate leukonychia.

The patient was counseled on the benign nature of his punctate leukonychia and assured that no treatment was necessary.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Iorizzo M, Starace M, Pasch MC. Leukonychia: what can white nails tell us? Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:177-193. doi: 10.1007/s40257-022-00671-6

1. Iorizzo M, Starace M, Pasch MC. Leukonychia: what can white nails tell us? Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:177-193. doi: 10.1007/s40257-022-00671-6

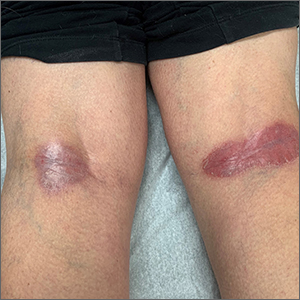

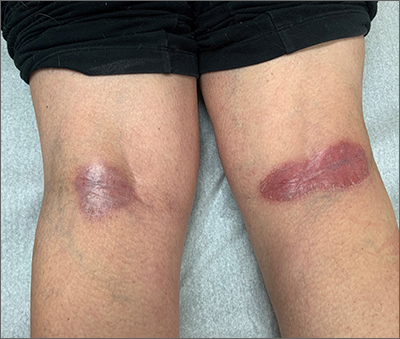

Popliteal plaques

Both a Wood lamp examination and a potassium hydroxide (KOH) prep returned negative results. Those findings, combined with the patient’s month-long antifungal medication adherence, helped to rule out other diagnoses. Based on history and examination, the patient was diagnosed with erythrasma.

Erythrasma is a skin infection caused by the gram-positive bacteria Corynebacterium minutissimum1 that usually manifests in moist intertriginous areas. Sometimes it is secondary to fungal or yeast infections, local skin irritation due to friction, or due to maceration of the skin from persistent moisture. The Wood lamp examination can show coral-red fluorescence in erythrasma, but recent bathing (as in this case) may limit this finding.1

The differential diagnosis of erythematous plaques in an intertriginous area includes inverse psoriasis. However, this patient had no nail changes, joint difficulties, or other rashes consistent with psoriasis. Macerated, erythematous inflammatory changes in intertriginous areas are always concerning for fungal infections (eg, yeast infection, tinea corporis), especially with the presence of any scale. In this case, the patient’s medication regimen helped to rule out these types of conditions.

First-line therapy for erythrasma includes topical antibiotics: clindamycin, erythromycin, mupirocin, and fusidic acid. Systemic antibiotics in the tetracycline family and macrolides may also be used but have a higher risk of adverse effects. Keeping the affected area dry is a useful adjunct to pharmacologic therapy.

The patient was treated with topical clindamycin bid for 7 days. By her 2-month follow-up appointment, there were no residual skin changes. Had the plaques persisted, the possibility of inverse psoriasis would have been revisited, with either presumptive treatment prescribed or biopsy performed to establish the diagnosis.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Forouzan P, Cohen PR. Erythrasma revisited: diagnosis, differential diagnoses, and comprehensive review of treatment. Cureus. 2020;12:e10733. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10733

Both a Wood lamp examination and a potassium hydroxide (KOH) prep returned negative results. Those findings, combined with the patient’s month-long antifungal medication adherence, helped to rule out other diagnoses. Based on history and examination, the patient was diagnosed with erythrasma.

Erythrasma is a skin infection caused by the gram-positive bacteria Corynebacterium minutissimum1 that usually manifests in moist intertriginous areas. Sometimes it is secondary to fungal or yeast infections, local skin irritation due to friction, or due to maceration of the skin from persistent moisture. The Wood lamp examination can show coral-red fluorescence in erythrasma, but recent bathing (as in this case) may limit this finding.1

The differential diagnosis of erythematous plaques in an intertriginous area includes inverse psoriasis. However, this patient had no nail changes, joint difficulties, or other rashes consistent with psoriasis. Macerated, erythematous inflammatory changes in intertriginous areas are always concerning for fungal infections (eg, yeast infection, tinea corporis), especially with the presence of any scale. In this case, the patient’s medication regimen helped to rule out these types of conditions.

First-line therapy for erythrasma includes topical antibiotics: clindamycin, erythromycin, mupirocin, and fusidic acid. Systemic antibiotics in the tetracycline family and macrolides may also be used but have a higher risk of adverse effects. Keeping the affected area dry is a useful adjunct to pharmacologic therapy.

The patient was treated with topical clindamycin bid for 7 days. By her 2-month follow-up appointment, there were no residual skin changes. Had the plaques persisted, the possibility of inverse psoriasis would have been revisited, with either presumptive treatment prescribed or biopsy performed to establish the diagnosis.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Both a Wood lamp examination and a potassium hydroxide (KOH) prep returned negative results. Those findings, combined with the patient’s month-long antifungal medication adherence, helped to rule out other diagnoses. Based on history and examination, the patient was diagnosed with erythrasma.

Erythrasma is a skin infection caused by the gram-positive bacteria Corynebacterium minutissimum1 that usually manifests in moist intertriginous areas. Sometimes it is secondary to fungal or yeast infections, local skin irritation due to friction, or due to maceration of the skin from persistent moisture. The Wood lamp examination can show coral-red fluorescence in erythrasma, but recent bathing (as in this case) may limit this finding.1

The differential diagnosis of erythematous plaques in an intertriginous area includes inverse psoriasis. However, this patient had no nail changes, joint difficulties, or other rashes consistent with psoriasis. Macerated, erythematous inflammatory changes in intertriginous areas are always concerning for fungal infections (eg, yeast infection, tinea corporis), especially with the presence of any scale. In this case, the patient’s medication regimen helped to rule out these types of conditions.

First-line therapy for erythrasma includes topical antibiotics: clindamycin, erythromycin, mupirocin, and fusidic acid. Systemic antibiotics in the tetracycline family and macrolides may also be used but have a higher risk of adverse effects. Keeping the affected area dry is a useful adjunct to pharmacologic therapy.

The patient was treated with topical clindamycin bid for 7 days. By her 2-month follow-up appointment, there were no residual skin changes. Had the plaques persisted, the possibility of inverse psoriasis would have been revisited, with either presumptive treatment prescribed or biopsy performed to establish the diagnosis.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Forouzan P, Cohen PR. Erythrasma revisited: diagnosis, differential diagnoses, and comprehensive review of treatment. Cureus. 2020;12:e10733. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10733

1. Forouzan P, Cohen PR. Erythrasma revisited: diagnosis, differential diagnoses, and comprehensive review of treatment. Cureus. 2020;12:e10733. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10733

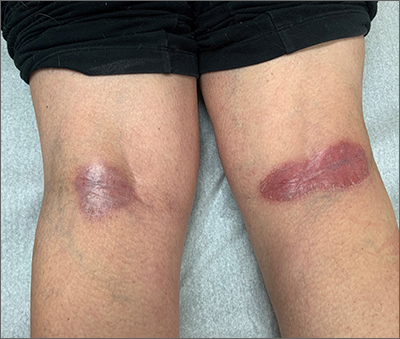

Linear leg rash

A 4-mm punch biopsy confirmed that this was a case of blaschkitis. This uncommon condition is referred to as adult blaschkitis because it resembles lichen striatus, a linear erythematous papular eruption usually seen in children younger than 15 years of age that erupts along Blaschko lines. The biopsy in this case helped to rule out lichen planus, which can also manifest with an erythematous papular eruption along Blaschko lines.

Adult blaschkitis is thought to be a hypersensitivity reaction involving T cells. It has been linked to medication use, insect stings, trauma, and autoimmune disease.1 The characteristic linear pattern is due to the inflammatory response following the Blaschko lines of keratinocytes that migrated during the embryonic phase.1 Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation is a frequent complication. Topical steroids often help with the itching, but do not usually make the lesions go away. There have been better results in reducing itching and lesion prominence with intralesional steroid injections, topical calcipotriol, or calcineurin inhibitors.1 The inflammation usually spontaneously resolves over 3 to 12 months.

The patient was advised that the condition is benign and would likely resolve on its own over time. She was counseled that since the clobetasol was helping with her itching, she could use it (sparingly) as needed. She was cautioned that prolonged usage could lead to skin atrophy.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Al-Balbeesi A. Adult blaschkitis with lichenoid features and blood eosinophilia. Cureus. 2021;13:e16846. doi: 10.7759/cureus.16846

A 4-mm punch biopsy confirmed that this was a case of blaschkitis. This uncommon condition is referred to as adult blaschkitis because it resembles lichen striatus, a linear erythematous papular eruption usually seen in children younger than 15 years of age that erupts along Blaschko lines. The biopsy in this case helped to rule out lichen planus, which can also manifest with an erythematous papular eruption along Blaschko lines.

Adult blaschkitis is thought to be a hypersensitivity reaction involving T cells. It has been linked to medication use, insect stings, trauma, and autoimmune disease.1 The characteristic linear pattern is due to the inflammatory response following the Blaschko lines of keratinocytes that migrated during the embryonic phase.1 Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation is a frequent complication. Topical steroids often help with the itching, but do not usually make the lesions go away. There have been better results in reducing itching and lesion prominence with intralesional steroid injections, topical calcipotriol, or calcineurin inhibitors.1 The inflammation usually spontaneously resolves over 3 to 12 months.

The patient was advised that the condition is benign and would likely resolve on its own over time. She was counseled that since the clobetasol was helping with her itching, she could use it (sparingly) as needed. She was cautioned that prolonged usage could lead to skin atrophy.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

A 4-mm punch biopsy confirmed that this was a case of blaschkitis. This uncommon condition is referred to as adult blaschkitis because it resembles lichen striatus, a linear erythematous papular eruption usually seen in children younger than 15 years of age that erupts along Blaschko lines. The biopsy in this case helped to rule out lichen planus, which can also manifest with an erythematous papular eruption along Blaschko lines.

Adult blaschkitis is thought to be a hypersensitivity reaction involving T cells. It has been linked to medication use, insect stings, trauma, and autoimmune disease.1 The characteristic linear pattern is due to the inflammatory response following the Blaschko lines of keratinocytes that migrated during the embryonic phase.1 Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation is a frequent complication. Topical steroids often help with the itching, but do not usually make the lesions go away. There have been better results in reducing itching and lesion prominence with intralesional steroid injections, topical calcipotriol, or calcineurin inhibitors.1 The inflammation usually spontaneously resolves over 3 to 12 months.

The patient was advised that the condition is benign and would likely resolve on its own over time. She was counseled that since the clobetasol was helping with her itching, she could use it (sparingly) as needed. She was cautioned that prolonged usage could lead to skin atrophy.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

1. Al-Balbeesi A. Adult blaschkitis with lichenoid features and blood eosinophilia. Cureus. 2021;13:e16846. doi: 10.7759/cureus.16846

1. Al-Balbeesi A. Adult blaschkitis with lichenoid features and blood eosinophilia. Cureus. 2021;13:e16846. doi: 10.7759/cureus.16846