User login

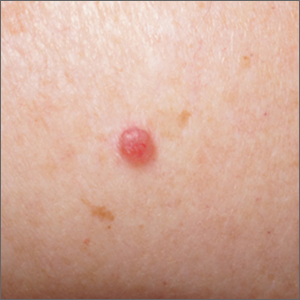

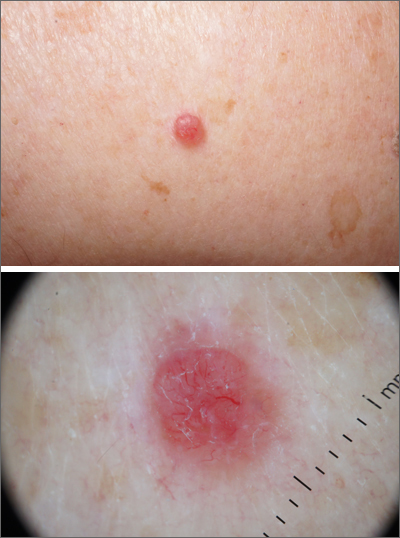

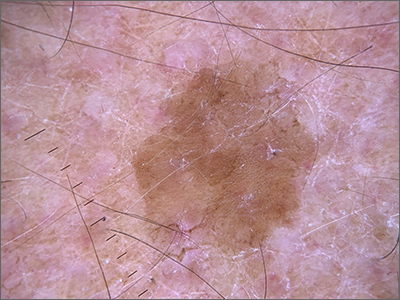

Pink shoulder lesion

A scoop shave biopsy was performed and histology was consistent with a nodular basal cell carcinoma. BCC is the most common skin cancer in the United States, occurring in approximately 30% of patients with skin types I and II.1 In patients who are Black, squamous cell carcinoma is more common than BCC.2 The overall incidence of BCC is increasing by 4% to 8% every year in the United States.1

BCC most often affects sun-damaged areas—especially on the head and neck—and frequently causes significant tissue damage. It is, however, associated with a low risk of metastasis and mortality.

BCCs may appear as a pink, brown, blue, or white papule or macule. The surface is frequently shiny or pearly in appearance with a rolled border. Dilated, angulated, tree-branch like vessels termed “arborizing vessels” are common. Infiltrative BCC subtypes may look like melted candlewax and extend beyond the area that is clinically apparent.

Partial shave biopsies of a lesion can confirm the diagnosis. A punch biopsy can make it easier to evaluate flat (or even sunken) lesions.

The patient described here was treated with electrodessication and curettage (EDC)—a fast, economical, and effective treatment for the low-risk subtypes of superficial or nodular BCCs on the trunk or extremities. EDC should be avoided with higher risk subtypes of micronodular and infiltrative BCC. With these subtypes, excision (with 4- to 6-mm margins) or Mohs microsurgery is recommended.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. References

1. Kim DP, Kus KJB, Ruiz E. Basal cell carcinoma review. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:13-24. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2018.09.004

2. Bradford PT. Skin cancer in skin of color. Dermatol Nurs. 2009;21:170-177, 206.

A scoop shave biopsy was performed and histology was consistent with a nodular basal cell carcinoma. BCC is the most common skin cancer in the United States, occurring in approximately 30% of patients with skin types I and II.1 In patients who are Black, squamous cell carcinoma is more common than BCC.2 The overall incidence of BCC is increasing by 4% to 8% every year in the United States.1

BCC most often affects sun-damaged areas—especially on the head and neck—and frequently causes significant tissue damage. It is, however, associated with a low risk of metastasis and mortality.

BCCs may appear as a pink, brown, blue, or white papule or macule. The surface is frequently shiny or pearly in appearance with a rolled border. Dilated, angulated, tree-branch like vessels termed “arborizing vessels” are common. Infiltrative BCC subtypes may look like melted candlewax and extend beyond the area that is clinically apparent.

Partial shave biopsies of a lesion can confirm the diagnosis. A punch biopsy can make it easier to evaluate flat (or even sunken) lesions.

The patient described here was treated with electrodessication and curettage (EDC)—a fast, economical, and effective treatment for the low-risk subtypes of superficial or nodular BCCs on the trunk or extremities. EDC should be avoided with higher risk subtypes of micronodular and infiltrative BCC. With these subtypes, excision (with 4- to 6-mm margins) or Mohs microsurgery is recommended.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. References

A scoop shave biopsy was performed and histology was consistent with a nodular basal cell carcinoma. BCC is the most common skin cancer in the United States, occurring in approximately 30% of patients with skin types I and II.1 In patients who are Black, squamous cell carcinoma is more common than BCC.2 The overall incidence of BCC is increasing by 4% to 8% every year in the United States.1

BCC most often affects sun-damaged areas—especially on the head and neck—and frequently causes significant tissue damage. It is, however, associated with a low risk of metastasis and mortality.

BCCs may appear as a pink, brown, blue, or white papule or macule. The surface is frequently shiny or pearly in appearance with a rolled border. Dilated, angulated, tree-branch like vessels termed “arborizing vessels” are common. Infiltrative BCC subtypes may look like melted candlewax and extend beyond the area that is clinically apparent.

Partial shave biopsies of a lesion can confirm the diagnosis. A punch biopsy can make it easier to evaluate flat (or even sunken) lesions.

The patient described here was treated with electrodessication and curettage (EDC)—a fast, economical, and effective treatment for the low-risk subtypes of superficial or nodular BCCs on the trunk or extremities. EDC should be avoided with higher risk subtypes of micronodular and infiltrative BCC. With these subtypes, excision (with 4- to 6-mm margins) or Mohs microsurgery is recommended.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. References

1. Kim DP, Kus KJB, Ruiz E. Basal cell carcinoma review. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:13-24. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2018.09.004

2. Bradford PT. Skin cancer in skin of color. Dermatol Nurs. 2009;21:170-177, 206.

1. Kim DP, Kus KJB, Ruiz E. Basal cell carcinoma review. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:13-24. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2018.09.004

2. Bradford PT. Skin cancer in skin of color. Dermatol Nurs. 2009;21:170-177, 206.

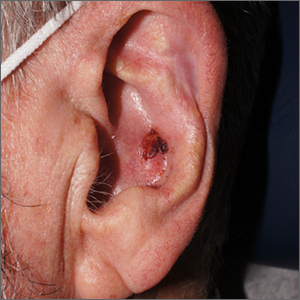

Crusty ear

The physician used a curette to perform a shave biopsy; pathology results indicated this was a poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Cutaneous SCC is the second most common skin cancer in the United States (after basal cell carcinoma) and increases in frequency with age and cumulative sun damage. It is the most common skin cancer in patients who are Black.

SCC is frequently found on the head and neck, including the ear, but is less commonly found within the conchal bowl (as seen here). Often, SCC manifests as a rough plaque or dome-shaped papule in a sun damaged location, but it may occasionally manifest as an ulcer. While most patients are cured with outpatient surgery, an estimated 8000 patients will develop nodal metastasis and 3000 patients will die from the disease in the United States annually.1 Chronically immunosuppressed patients, such as organ transplant recipients, are at high risk.

This patient underwent Mohs microsurgery (MMS) and clear margins were achieved after 2 stages. The resulting defect was repaired with a full-thickness graft from the postauricular fold. MMS is an excellent technique for keratinocyte carcinomas (SCC and basal cell carcinomas) of the head and neck, recurrent skin cancers on the trunk and extremities, high-risk cancer subtypes, and tumors with indistinct clinical borders. Follow-up for patients with SCCs includes full skin exams every 6 months for 2 years.

The American Academy of Dermatology offers a complimentary Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria App that assists in determining when Mohs surgery is appropriate, based on multiple tumor characteristics.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Waldman A, Schmults C. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:1-12. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2018.08.001

The physician used a curette to perform a shave biopsy; pathology results indicated this was a poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Cutaneous SCC is the second most common skin cancer in the United States (after basal cell carcinoma) and increases in frequency with age and cumulative sun damage. It is the most common skin cancer in patients who are Black.

SCC is frequently found on the head and neck, including the ear, but is less commonly found within the conchal bowl (as seen here). Often, SCC manifests as a rough plaque or dome-shaped papule in a sun damaged location, but it may occasionally manifest as an ulcer. While most patients are cured with outpatient surgery, an estimated 8000 patients will develop nodal metastasis and 3000 patients will die from the disease in the United States annually.1 Chronically immunosuppressed patients, such as organ transplant recipients, are at high risk.

This patient underwent Mohs microsurgery (MMS) and clear margins were achieved after 2 stages. The resulting defect was repaired with a full-thickness graft from the postauricular fold. MMS is an excellent technique for keratinocyte carcinomas (SCC and basal cell carcinomas) of the head and neck, recurrent skin cancers on the trunk and extremities, high-risk cancer subtypes, and tumors with indistinct clinical borders. Follow-up for patients with SCCs includes full skin exams every 6 months for 2 years.

The American Academy of Dermatology offers a complimentary Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria App that assists in determining when Mohs surgery is appropriate, based on multiple tumor characteristics.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

The physician used a curette to perform a shave biopsy; pathology results indicated this was a poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Cutaneous SCC is the second most common skin cancer in the United States (after basal cell carcinoma) and increases in frequency with age and cumulative sun damage. It is the most common skin cancer in patients who are Black.

SCC is frequently found on the head and neck, including the ear, but is less commonly found within the conchal bowl (as seen here). Often, SCC manifests as a rough plaque or dome-shaped papule in a sun damaged location, but it may occasionally manifest as an ulcer. While most patients are cured with outpatient surgery, an estimated 8000 patients will develop nodal metastasis and 3000 patients will die from the disease in the United States annually.1 Chronically immunosuppressed patients, such as organ transplant recipients, are at high risk.

This patient underwent Mohs microsurgery (MMS) and clear margins were achieved after 2 stages. The resulting defect was repaired with a full-thickness graft from the postauricular fold. MMS is an excellent technique for keratinocyte carcinomas (SCC and basal cell carcinomas) of the head and neck, recurrent skin cancers on the trunk and extremities, high-risk cancer subtypes, and tumors with indistinct clinical borders. Follow-up for patients with SCCs includes full skin exams every 6 months for 2 years.

The American Academy of Dermatology offers a complimentary Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria App that assists in determining when Mohs surgery is appropriate, based on multiple tumor characteristics.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Waldman A, Schmults C. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:1-12. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2018.08.001

1. Waldman A, Schmults C. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:1-12. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2018.08.001

Sacral blistering

This patient had sustained multiple pressure injuries. The superior aspect of this image shows bullous change with intact dermis, which would classify that area of injury as a Stage 2 pressure injury.1 An older injury in the coccygeal area was through the dermis (Stage 3), with some eschar seen at the base, making that area unstageable.1 (There may have been deeper injury under the eschar.)

This patient was at heightened risk for pressure injury because of his paraplegia.2 Fortunately, he had some preserved sensation. However, his rotator cuff surgery made it harder for him to smoothly transfer to and from the wheelchair, leading to sheer forces against his skin. Social determinates of health care pose an additional risk for pressure injuries. Without a properly fitted wheelchair and cushion, there is an increased risk of localized pressure over both bony prominences and parts of the body that come into contact with mechanical elements of the wheelchair.

Treatment for all pressure injuries includes relief of pressure on the affected area. In this patient’s case, he had to stay in bed (and out of the wheelchair) so that he could heal.

This patient was very knowledgeable about his condition and pressure injuries. He had already arranged for a wheelchair fitting and a visit with the wound care team. His Stage 2 injury had a bullous change instead of absent epithelium, so rather than an adherent hydrocolloid dressing (which would likely remove the loosened epithelium), he was provided with a nonadherent dressing to the area, then an absorbent foam overdressing.

An image of the patient’s deeper sacral injury was shared with the wound care team, which recommended filling the area with a silver rope dressing for its absorptive filler and antibacterial properties. The area was then covered with an absorbent foam. The patient planned to follow up with the Wound Care Clinic for reevaluation and ongoing treatment.

Images and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine Kalamazoo.

1. 2019 Guideline. The National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel. Accessed October 9, 2022. https://npiap.com/page/2019Guideline

2. Ricci JA, Bayer LR, Orgill DP. Evidence-based medicine: the evaluation and treatment of pressure injuries. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139:275e-286e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002850

This patient had sustained multiple pressure injuries. The superior aspect of this image shows bullous change with intact dermis, which would classify that area of injury as a Stage 2 pressure injury.1 An older injury in the coccygeal area was through the dermis (Stage 3), with some eschar seen at the base, making that area unstageable.1 (There may have been deeper injury under the eschar.)

This patient was at heightened risk for pressure injury because of his paraplegia.2 Fortunately, he had some preserved sensation. However, his rotator cuff surgery made it harder for him to smoothly transfer to and from the wheelchair, leading to sheer forces against his skin. Social determinates of health care pose an additional risk for pressure injuries. Without a properly fitted wheelchair and cushion, there is an increased risk of localized pressure over both bony prominences and parts of the body that come into contact with mechanical elements of the wheelchair.

Treatment for all pressure injuries includes relief of pressure on the affected area. In this patient’s case, he had to stay in bed (and out of the wheelchair) so that he could heal.

This patient was very knowledgeable about his condition and pressure injuries. He had already arranged for a wheelchair fitting and a visit with the wound care team. His Stage 2 injury had a bullous change instead of absent epithelium, so rather than an adherent hydrocolloid dressing (which would likely remove the loosened epithelium), he was provided with a nonadherent dressing to the area, then an absorbent foam overdressing.

An image of the patient’s deeper sacral injury was shared with the wound care team, which recommended filling the area with a silver rope dressing for its absorptive filler and antibacterial properties. The area was then covered with an absorbent foam. The patient planned to follow up with the Wound Care Clinic for reevaluation and ongoing treatment.

Images and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine Kalamazoo.

This patient had sustained multiple pressure injuries. The superior aspect of this image shows bullous change with intact dermis, which would classify that area of injury as a Stage 2 pressure injury.1 An older injury in the coccygeal area was through the dermis (Stage 3), with some eschar seen at the base, making that area unstageable.1 (There may have been deeper injury under the eschar.)

This patient was at heightened risk for pressure injury because of his paraplegia.2 Fortunately, he had some preserved sensation. However, his rotator cuff surgery made it harder for him to smoothly transfer to and from the wheelchair, leading to sheer forces against his skin. Social determinates of health care pose an additional risk for pressure injuries. Without a properly fitted wheelchair and cushion, there is an increased risk of localized pressure over both bony prominences and parts of the body that come into contact with mechanical elements of the wheelchair.

Treatment for all pressure injuries includes relief of pressure on the affected area. In this patient’s case, he had to stay in bed (and out of the wheelchair) so that he could heal.

This patient was very knowledgeable about his condition and pressure injuries. He had already arranged for a wheelchair fitting and a visit with the wound care team. His Stage 2 injury had a bullous change instead of absent epithelium, so rather than an adherent hydrocolloid dressing (which would likely remove the loosened epithelium), he was provided with a nonadherent dressing to the area, then an absorbent foam overdressing.

An image of the patient’s deeper sacral injury was shared with the wound care team, which recommended filling the area with a silver rope dressing for its absorptive filler and antibacterial properties. The area was then covered with an absorbent foam. The patient planned to follow up with the Wound Care Clinic for reevaluation and ongoing treatment.

Images and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine Kalamazoo.

1. 2019 Guideline. The National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel. Accessed October 9, 2022. https://npiap.com/page/2019Guideline

2. Ricci JA, Bayer LR, Orgill DP. Evidence-based medicine: the evaluation and treatment of pressure injuries. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139:275e-286e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002850

1. 2019 Guideline. The National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel. Accessed October 9, 2022. https://npiap.com/page/2019Guideline

2. Ricci JA, Bayer LR, Orgill DP. Evidence-based medicine: the evaluation and treatment of pressure injuries. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139:275e-286e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002850

Newborn with white oral lesions

These lesions, called Bohn nodules, manifest on the buccal or lingual portion of the maxillary alveolar ridge and, less frequently, on the mandibular alveolar ridge. Because Bohn nodules are white and have a firm consistency, they are often confused with teeth. They can be differentiated by location, as teeth usually erupt from the distal aspect of the alveolar ridge.

Bohn nodules are epithelial cysts that are filled with keratin, which gives them their white color. They are caused by portions of epithelium that get trapped under surrounding epithelial cells. Bohn nodules usually resolve when the overlying epithelium ruptures and releases the keratinaceous material (usually by the time the child is 3 months of age).1

These nodules can be confused with neonatal or supernumerary teeth. Neonatal teeth can be abnormally small and pointed; they are true deciduous teeth that have erupted early. If they are removed, the child will not replace them until the time of their adult tooth eruption. Additionally, there are supernumerary teeth, which are extra teeth that are often abnormally shaped and loosely adherent. These abnormal teeth warrant extraction to avoid trauma to the tongue or aspiration.2

In this case, the family was advised regarding the benign nature of the nodules and the expectation that they would spontaneously resolve.

Images and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine Kalamazoo.

1. Gupta N, Ramji S. Bohn's nodules: an under-recognised entity. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2013;98:F464. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-302922

2. DeSeta M, Holden E, Siddik D, et al. Natal and neonatal teeth: a review and case series. Br Dent J. 2022;232:449-453. doi: 10.1038/s41415-022-4091-3

These lesions, called Bohn nodules, manifest on the buccal or lingual portion of the maxillary alveolar ridge and, less frequently, on the mandibular alveolar ridge. Because Bohn nodules are white and have a firm consistency, they are often confused with teeth. They can be differentiated by location, as teeth usually erupt from the distal aspect of the alveolar ridge.

Bohn nodules are epithelial cysts that are filled with keratin, which gives them their white color. They are caused by portions of epithelium that get trapped under surrounding epithelial cells. Bohn nodules usually resolve when the overlying epithelium ruptures and releases the keratinaceous material (usually by the time the child is 3 months of age).1

These nodules can be confused with neonatal or supernumerary teeth. Neonatal teeth can be abnormally small and pointed; they are true deciduous teeth that have erupted early. If they are removed, the child will not replace them until the time of their adult tooth eruption. Additionally, there are supernumerary teeth, which are extra teeth that are often abnormally shaped and loosely adherent. These abnormal teeth warrant extraction to avoid trauma to the tongue or aspiration.2

In this case, the family was advised regarding the benign nature of the nodules and the expectation that they would spontaneously resolve.

Images and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine Kalamazoo.

These lesions, called Bohn nodules, manifest on the buccal or lingual portion of the maxillary alveolar ridge and, less frequently, on the mandibular alveolar ridge. Because Bohn nodules are white and have a firm consistency, they are often confused with teeth. They can be differentiated by location, as teeth usually erupt from the distal aspect of the alveolar ridge.

Bohn nodules are epithelial cysts that are filled with keratin, which gives them their white color. They are caused by portions of epithelium that get trapped under surrounding epithelial cells. Bohn nodules usually resolve when the overlying epithelium ruptures and releases the keratinaceous material (usually by the time the child is 3 months of age).1

These nodules can be confused with neonatal or supernumerary teeth. Neonatal teeth can be abnormally small and pointed; they are true deciduous teeth that have erupted early. If they are removed, the child will not replace them until the time of their adult tooth eruption. Additionally, there are supernumerary teeth, which are extra teeth that are often abnormally shaped and loosely adherent. These abnormal teeth warrant extraction to avoid trauma to the tongue or aspiration.2

In this case, the family was advised regarding the benign nature of the nodules and the expectation that they would spontaneously resolve.

Images and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine Kalamazoo.

1. Gupta N, Ramji S. Bohn's nodules: an under-recognised entity. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2013;98:F464. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-302922

2. DeSeta M, Holden E, Siddik D, et al. Natal and neonatal teeth: a review and case series. Br Dent J. 2022;232:449-453. doi: 10.1038/s41415-022-4091-3

1. Gupta N, Ramji S. Bohn's nodules: an under-recognised entity. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2013;98:F464. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-302922

2. DeSeta M, Holden E, Siddik D, et al. Natal and neonatal teeth: a review and case series. Br Dent J. 2022;232:449-453. doi: 10.1038/s41415-022-4091-3

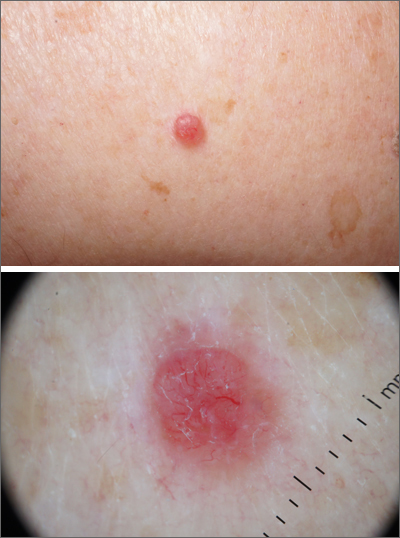

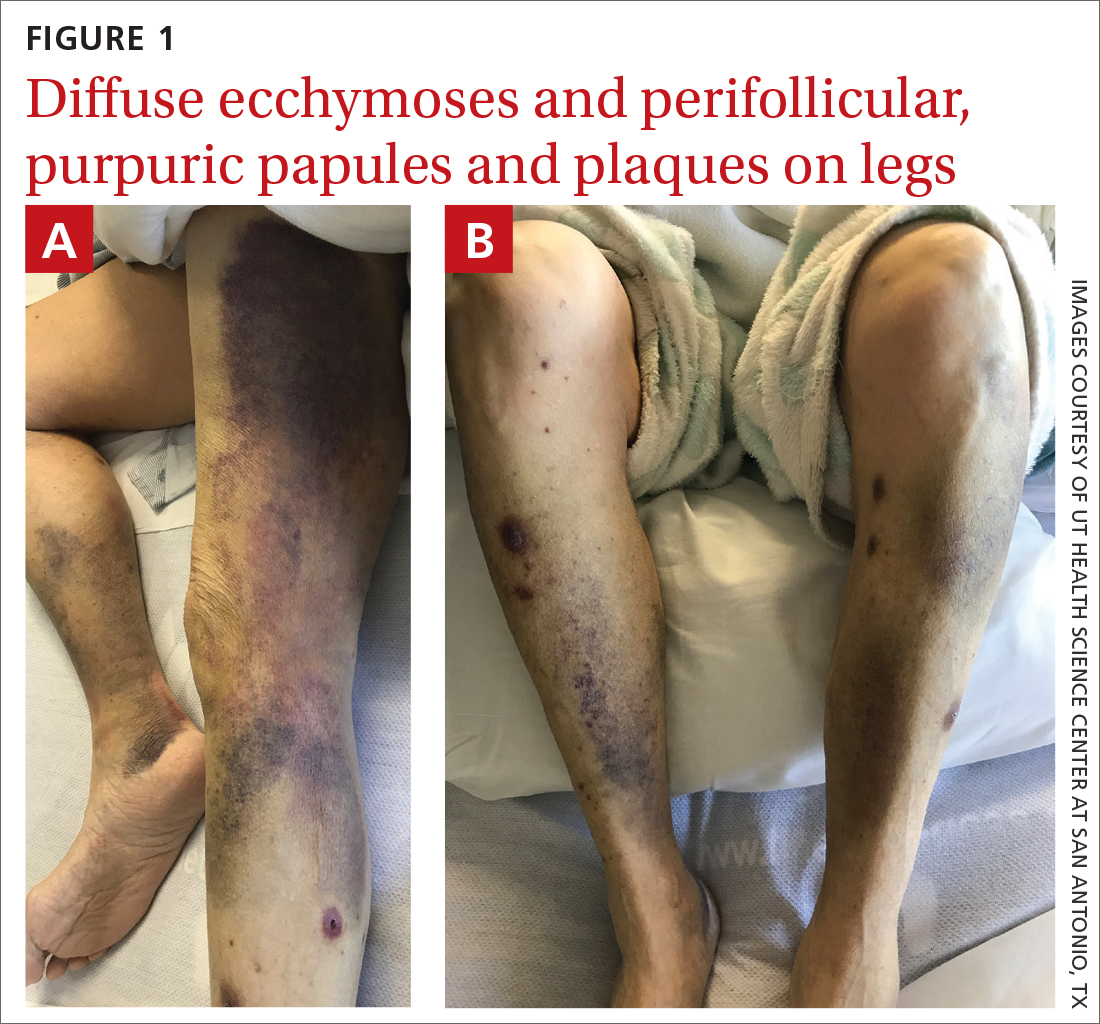

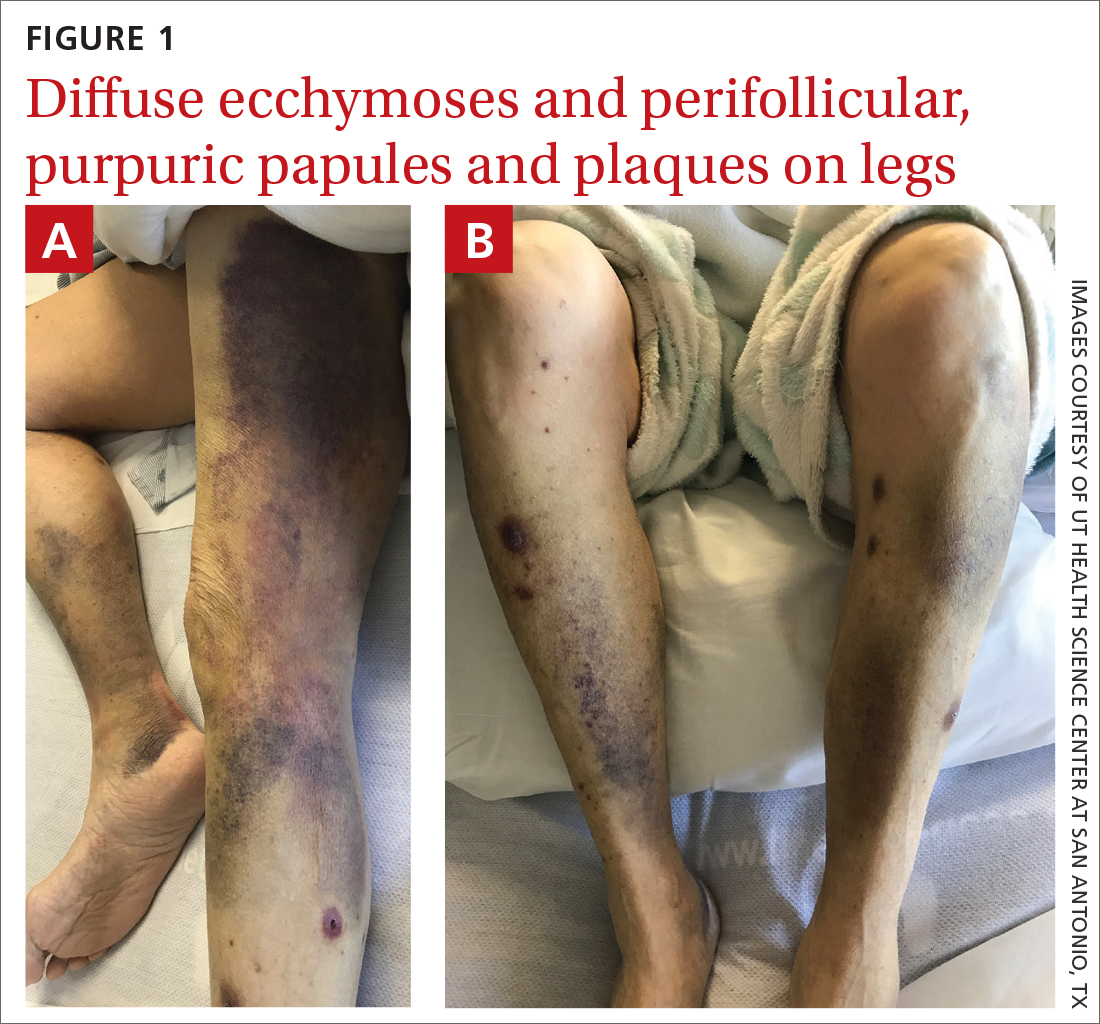

Spontaneous ecchymoses

A 65-YEAR-OLD WOMAN was brought into the emergency department by her daughter for spontaneous bruising, fatigue, and weakness of several weeks’ duration. She denied taking any medications or illicit drugs and had not experienced any falls or trauma. On a daily basis, she smoked 5 to 7 cigarettes and drank 6 or 7 beers, as had been her custom for several years. The patient lived alone and was grieving the death of her beloved dog, who had died a month earlier. She reported that since the death of her dog, her diet, which hadn’t been especially good to begin with, had deteriorated; it now consisted of beer and crackers.

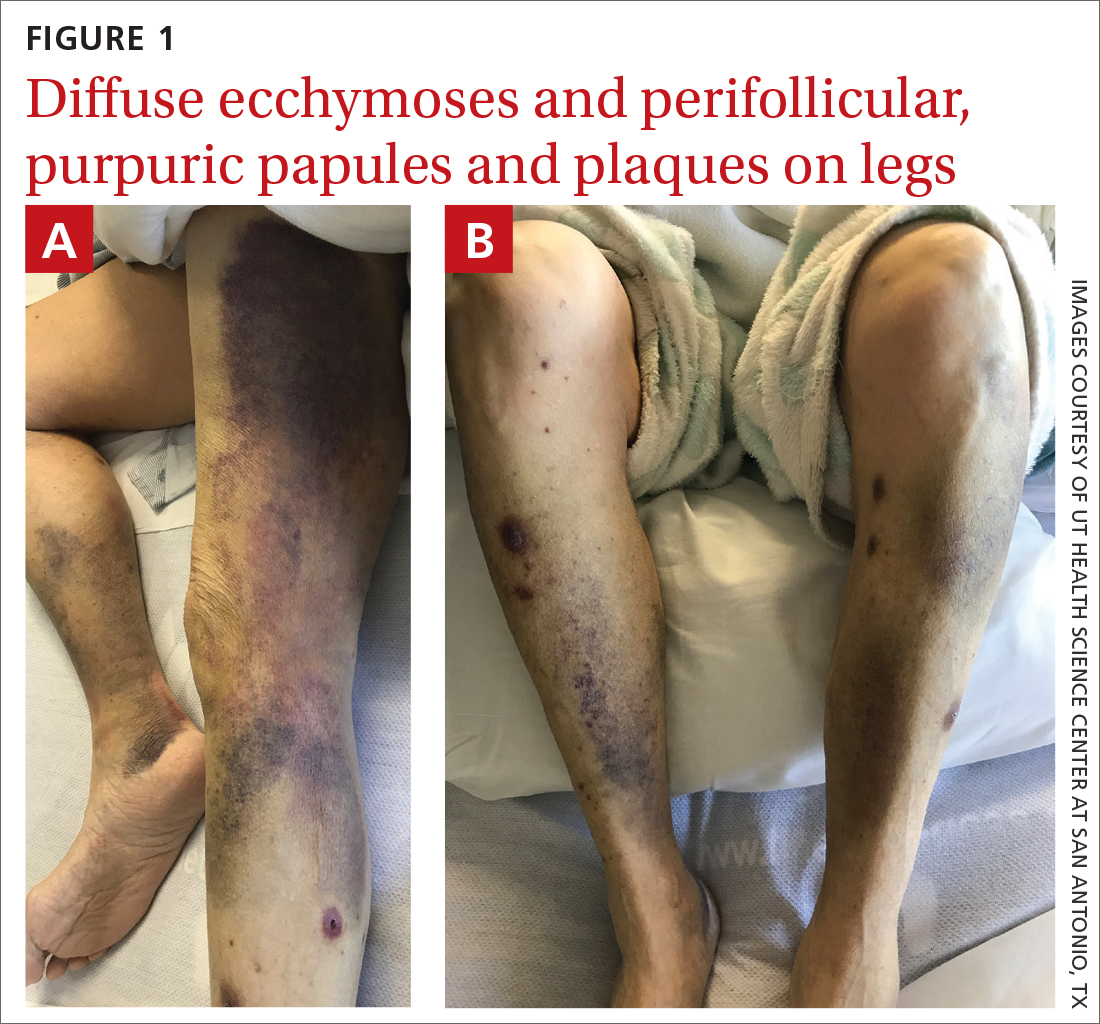

On admission, she was mildly tachycardic (105 beats/min) with a blood pressure of 125/66 mm Hg. Physical examination revealed a frail-appearing woman who was in no acute distress but was unable to stand without assistance. She had diffuse ecchymoses and perifollicular, purpuric, hyperkeratotic papules and plaques on both of her legs (FIGURES 1A and 1B). In addition, she had faint perifollicular purpuric macules on her upper back. An oral examination revealed poor dentition.

A punch biopsy was performed on her leg, and it revealed noninflammatory dermal hemorrhage without evidence of vasculitis or vasculopathy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Scurvy

Based on the patient’s appearance and her dietary history, we suspected scurvy, so a serum vitamin C level was ordered. The results took several days to return. In the meantime, additional lab work revealed hyponatremia (sodium, 129 mmol/L; normal range, 135-145 mmol/L), hypokalemia (potassium, 3 mmol/L; normal range, 3.5-5.2 mmol/L), hypophosphatemia (phosphorus, 2.3 mg/dL; normal range, 2.8-4.5 mg/dL); low serum vitamin D (6 ng/mL; normal range, 20-40 ng/mL); and macrocytic anemia (hemoglobin, 7.4 g/dL; normal range, 11-18 g/dL) with a mean corpuscular volume of 101.1 fL (normal range, 80-100 fL). Her iron panel showed normal serum iron and total iron binding capacity with a normal ferritin level (294 ng/mL; normal range, 30-300 ng/mL). A peripheral blood smear test uncovered mild anisocytosis and polychromasia, with no schistocytes. A fecal immunochemical test was negative.

Several days after admission, the results of the patient’s vitamin C test came back. Her levels were undetectable (< 5 µmol/L; normal range, 11-23 µmol/L), confirming that the patient had scurvy.

A health hazard to marinersthat is still around today

Scurvy is a condition that arises from a deficiency of vitamin C, or ascorbic acid. The first known case of scurvy was in 1550 BC.1 Hippocrates termed the condition “ileos ematitis” and stated that “the mouth feels bad; the gums are detached from the teeth; blood runs from the nostrils … ulcerations on the legs … skin is thin.”1 Scurvy was a major health hazard of mariners between the 15thand 18th centuries.2 Today, the deficiency is uncommon in industrialized countries because there are many sources of vitamin C available through diet and vitamin supplements.3 In the United States, the prevalence of vitamin C deficiency is approximately 7%.4

An essential nutrient in humans, vitamin C is required as a cofactor in the synthesis of mature collagen.3 Collagen is found in skin, bone, and endothelium. Inadequate collagen levels can result in poor dermal support of vessels and tissue fragility, leading to hemorrhage, which can occur in nearly any organ system.

Vitamin C deficiency occurs when serum concentration falls below 11.4

Continue to: Scurvy manifests after 8 to 12 weeks

Scurvy manifests after 8 to 12 weeks of inadequate vitamin C intake.1 Patients may initially experience malaise and irritability. Anemia is common. Dermatologic findings include hyperkeratotic lesions, ecchymoses, poor wound healing, gingival swelling with loss of teeth, petechiae, and corkscrew hairs. Perifollicular hemorrhage is a characteristic finding of scurvy, generally seen on the lower extremities, where the capillaries are under higher hydrostatic pressure.3 Patients may also have musculoskeletal involvement with osteopenia or hemarthroses, which may be seen on imaging.3,5 Cardiorespiratory, gastrointestinal, ophthalmologic, and neurologic findings have also been reported.3

Differential is broad; zero in on patient’s history

The differential diagnosis for hemorrhagic skin lesions is extensive and includes scurvy, coagulopathies, trauma, vasculitis, and vasculopathies.

The presence of perifollicular hemorrhage with corkscrew hairs and a dietary history of inadequate vitamin C intake can differentiate scurvy from other conditions. Serum testing revealing low plasma vitamin C will support the diagnosis, but this is an insensitive test, as values increase with recent intake. Leukocyte ascorbic acid concentrations are more representative of total body stores, but impractical for routine use.6 Skin biopsy is not necessary but may help to rule out other conditions.

Ascorbic acid will facilitate a speedy recovery

Treatment of scurvy includes vitamin C replacement. Response is rapid, with improvement to lethargy within several days and disappearance of other manifestations within several weeks.3 Recommendations on supplementation doses and forms vary, but adults require 300 to 1000 mg/d of ascorbic acid for at least 1 week or until clinical symptoms resolve and stores are repleted.3,5,7

During our patient’s hospital stay, she remained stable and improved clinically with vitamin supplementation (ascorbic acid 1 g/d for 3 days, 500 mg/d after that) and physical therapy. She was counseled on a healthy diet, which would include citrus fruits, tomatoes, and leafy vegetables. The patient was also advised to refrain from drinking alcohol and was given information on an alcohol abstinence program.

At her 1-month follow-up, her condition had improved with near resolution of the skin lesions. She reported that she had given up cigarettes and alcohol. She said she’d also begun eating more citrus fruits and leafy vegetables.

1. Maxfield L, Crane JS. Vitamin C deficiency (scurvy). In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Accessed on September 13, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493187/

2. Worral S. A nightmare disease haunted ships during age of discovery. National Geographic. January 15, 2017. Accessed September 21, 2022. www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/scurvy-disease-discovery-jonathan-lamb

3. Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Adult Scurvy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:895-906. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70244-6

4. Schleicher RL, Carroll MD, Ford ES, et al. Serum vitamin C and the prevalence of vitamin C deficiency in the United States: 2003-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1252-1263. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27016

5. Agarwal A, Shaharyar A, Kumar A, et al. Scurvy in pediatric age group – A disease often forgotten? J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2015;6:101-107. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2014.12.003

6. Scurvy and its prevention and control in major emergencies. World Health Organization. February 23, 1999. Accessed September 13, 2022. www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NHD-99.11

7. Weinstein M, Babyn P, Zlotkin S. An orange a day keeps the doctor away: scurvy in the year 2000. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E55. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.e55

A 65-YEAR-OLD WOMAN was brought into the emergency department by her daughter for spontaneous bruising, fatigue, and weakness of several weeks’ duration. She denied taking any medications or illicit drugs and had not experienced any falls or trauma. On a daily basis, she smoked 5 to 7 cigarettes and drank 6 or 7 beers, as had been her custom for several years. The patient lived alone and was grieving the death of her beloved dog, who had died a month earlier. She reported that since the death of her dog, her diet, which hadn’t been especially good to begin with, had deteriorated; it now consisted of beer and crackers.

On admission, she was mildly tachycardic (105 beats/min) with a blood pressure of 125/66 mm Hg. Physical examination revealed a frail-appearing woman who was in no acute distress but was unable to stand without assistance. She had diffuse ecchymoses and perifollicular, purpuric, hyperkeratotic papules and plaques on both of her legs (FIGURES 1A and 1B). In addition, she had faint perifollicular purpuric macules on her upper back. An oral examination revealed poor dentition.

A punch biopsy was performed on her leg, and it revealed noninflammatory dermal hemorrhage without evidence of vasculitis or vasculopathy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Scurvy

Based on the patient’s appearance and her dietary history, we suspected scurvy, so a serum vitamin C level was ordered. The results took several days to return. In the meantime, additional lab work revealed hyponatremia (sodium, 129 mmol/L; normal range, 135-145 mmol/L), hypokalemia (potassium, 3 mmol/L; normal range, 3.5-5.2 mmol/L), hypophosphatemia (phosphorus, 2.3 mg/dL; normal range, 2.8-4.5 mg/dL); low serum vitamin D (6 ng/mL; normal range, 20-40 ng/mL); and macrocytic anemia (hemoglobin, 7.4 g/dL; normal range, 11-18 g/dL) with a mean corpuscular volume of 101.1 fL (normal range, 80-100 fL). Her iron panel showed normal serum iron and total iron binding capacity with a normal ferritin level (294 ng/mL; normal range, 30-300 ng/mL). A peripheral blood smear test uncovered mild anisocytosis and polychromasia, with no schistocytes. A fecal immunochemical test was negative.

Several days after admission, the results of the patient’s vitamin C test came back. Her levels were undetectable (< 5 µmol/L; normal range, 11-23 µmol/L), confirming that the patient had scurvy.

A health hazard to marinersthat is still around today

Scurvy is a condition that arises from a deficiency of vitamin C, or ascorbic acid. The first known case of scurvy was in 1550 BC.1 Hippocrates termed the condition “ileos ematitis” and stated that “the mouth feels bad; the gums are detached from the teeth; blood runs from the nostrils … ulcerations on the legs … skin is thin.”1 Scurvy was a major health hazard of mariners between the 15thand 18th centuries.2 Today, the deficiency is uncommon in industrialized countries because there are many sources of vitamin C available through diet and vitamin supplements.3 In the United States, the prevalence of vitamin C deficiency is approximately 7%.4

An essential nutrient in humans, vitamin C is required as a cofactor in the synthesis of mature collagen.3 Collagen is found in skin, bone, and endothelium. Inadequate collagen levels can result in poor dermal support of vessels and tissue fragility, leading to hemorrhage, which can occur in nearly any organ system.

Vitamin C deficiency occurs when serum concentration falls below 11.4

Continue to: Scurvy manifests after 8 to 12 weeks

Scurvy manifests after 8 to 12 weeks of inadequate vitamin C intake.1 Patients may initially experience malaise and irritability. Anemia is common. Dermatologic findings include hyperkeratotic lesions, ecchymoses, poor wound healing, gingival swelling with loss of teeth, petechiae, and corkscrew hairs. Perifollicular hemorrhage is a characteristic finding of scurvy, generally seen on the lower extremities, where the capillaries are under higher hydrostatic pressure.3 Patients may also have musculoskeletal involvement with osteopenia or hemarthroses, which may be seen on imaging.3,5 Cardiorespiratory, gastrointestinal, ophthalmologic, and neurologic findings have also been reported.3

Differential is broad; zero in on patient’s history

The differential diagnosis for hemorrhagic skin lesions is extensive and includes scurvy, coagulopathies, trauma, vasculitis, and vasculopathies.

The presence of perifollicular hemorrhage with corkscrew hairs and a dietary history of inadequate vitamin C intake can differentiate scurvy from other conditions. Serum testing revealing low plasma vitamin C will support the diagnosis, but this is an insensitive test, as values increase with recent intake. Leukocyte ascorbic acid concentrations are more representative of total body stores, but impractical for routine use.6 Skin biopsy is not necessary but may help to rule out other conditions.

Ascorbic acid will facilitate a speedy recovery

Treatment of scurvy includes vitamin C replacement. Response is rapid, with improvement to lethargy within several days and disappearance of other manifestations within several weeks.3 Recommendations on supplementation doses and forms vary, but adults require 300 to 1000 mg/d of ascorbic acid for at least 1 week or until clinical symptoms resolve and stores are repleted.3,5,7

During our patient’s hospital stay, she remained stable and improved clinically with vitamin supplementation (ascorbic acid 1 g/d for 3 days, 500 mg/d after that) and physical therapy. She was counseled on a healthy diet, which would include citrus fruits, tomatoes, and leafy vegetables. The patient was also advised to refrain from drinking alcohol and was given information on an alcohol abstinence program.

At her 1-month follow-up, her condition had improved with near resolution of the skin lesions. She reported that she had given up cigarettes and alcohol. She said she’d also begun eating more citrus fruits and leafy vegetables.

A 65-YEAR-OLD WOMAN was brought into the emergency department by her daughter for spontaneous bruising, fatigue, and weakness of several weeks’ duration. She denied taking any medications or illicit drugs and had not experienced any falls or trauma. On a daily basis, she smoked 5 to 7 cigarettes and drank 6 or 7 beers, as had been her custom for several years. The patient lived alone and was grieving the death of her beloved dog, who had died a month earlier. She reported that since the death of her dog, her diet, which hadn’t been especially good to begin with, had deteriorated; it now consisted of beer and crackers.

On admission, she was mildly tachycardic (105 beats/min) with a blood pressure of 125/66 mm Hg. Physical examination revealed a frail-appearing woman who was in no acute distress but was unable to stand without assistance. She had diffuse ecchymoses and perifollicular, purpuric, hyperkeratotic papules and plaques on both of her legs (FIGURES 1A and 1B). In addition, she had faint perifollicular purpuric macules on her upper back. An oral examination revealed poor dentition.

A punch biopsy was performed on her leg, and it revealed noninflammatory dermal hemorrhage without evidence of vasculitis or vasculopathy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Scurvy

Based on the patient’s appearance and her dietary history, we suspected scurvy, so a serum vitamin C level was ordered. The results took several days to return. In the meantime, additional lab work revealed hyponatremia (sodium, 129 mmol/L; normal range, 135-145 mmol/L), hypokalemia (potassium, 3 mmol/L; normal range, 3.5-5.2 mmol/L), hypophosphatemia (phosphorus, 2.3 mg/dL; normal range, 2.8-4.5 mg/dL); low serum vitamin D (6 ng/mL; normal range, 20-40 ng/mL); and macrocytic anemia (hemoglobin, 7.4 g/dL; normal range, 11-18 g/dL) with a mean corpuscular volume of 101.1 fL (normal range, 80-100 fL). Her iron panel showed normal serum iron and total iron binding capacity with a normal ferritin level (294 ng/mL; normal range, 30-300 ng/mL). A peripheral blood smear test uncovered mild anisocytosis and polychromasia, with no schistocytes. A fecal immunochemical test was negative.

Several days after admission, the results of the patient’s vitamin C test came back. Her levels were undetectable (< 5 µmol/L; normal range, 11-23 µmol/L), confirming that the patient had scurvy.

A health hazard to marinersthat is still around today

Scurvy is a condition that arises from a deficiency of vitamin C, or ascorbic acid. The first known case of scurvy was in 1550 BC.1 Hippocrates termed the condition “ileos ematitis” and stated that “the mouth feels bad; the gums are detached from the teeth; blood runs from the nostrils … ulcerations on the legs … skin is thin.”1 Scurvy was a major health hazard of mariners between the 15thand 18th centuries.2 Today, the deficiency is uncommon in industrialized countries because there are many sources of vitamin C available through diet and vitamin supplements.3 In the United States, the prevalence of vitamin C deficiency is approximately 7%.4

An essential nutrient in humans, vitamin C is required as a cofactor in the synthesis of mature collagen.3 Collagen is found in skin, bone, and endothelium. Inadequate collagen levels can result in poor dermal support of vessels and tissue fragility, leading to hemorrhage, which can occur in nearly any organ system.

Vitamin C deficiency occurs when serum concentration falls below 11.4

Continue to: Scurvy manifests after 8 to 12 weeks

Scurvy manifests after 8 to 12 weeks of inadequate vitamin C intake.1 Patients may initially experience malaise and irritability. Anemia is common. Dermatologic findings include hyperkeratotic lesions, ecchymoses, poor wound healing, gingival swelling with loss of teeth, petechiae, and corkscrew hairs. Perifollicular hemorrhage is a characteristic finding of scurvy, generally seen on the lower extremities, where the capillaries are under higher hydrostatic pressure.3 Patients may also have musculoskeletal involvement with osteopenia or hemarthroses, which may be seen on imaging.3,5 Cardiorespiratory, gastrointestinal, ophthalmologic, and neurologic findings have also been reported.3

Differential is broad; zero in on patient’s history

The differential diagnosis for hemorrhagic skin lesions is extensive and includes scurvy, coagulopathies, trauma, vasculitis, and vasculopathies.

The presence of perifollicular hemorrhage with corkscrew hairs and a dietary history of inadequate vitamin C intake can differentiate scurvy from other conditions. Serum testing revealing low plasma vitamin C will support the diagnosis, but this is an insensitive test, as values increase with recent intake. Leukocyte ascorbic acid concentrations are more representative of total body stores, but impractical for routine use.6 Skin biopsy is not necessary but may help to rule out other conditions.

Ascorbic acid will facilitate a speedy recovery

Treatment of scurvy includes vitamin C replacement. Response is rapid, with improvement to lethargy within several days and disappearance of other manifestations within several weeks.3 Recommendations on supplementation doses and forms vary, but adults require 300 to 1000 mg/d of ascorbic acid for at least 1 week or until clinical symptoms resolve and stores are repleted.3,5,7

During our patient’s hospital stay, she remained stable and improved clinically with vitamin supplementation (ascorbic acid 1 g/d for 3 days, 500 mg/d after that) and physical therapy. She was counseled on a healthy diet, which would include citrus fruits, tomatoes, and leafy vegetables. The patient was also advised to refrain from drinking alcohol and was given information on an alcohol abstinence program.

At her 1-month follow-up, her condition had improved with near resolution of the skin lesions. She reported that she had given up cigarettes and alcohol. She said she’d also begun eating more citrus fruits and leafy vegetables.

1. Maxfield L, Crane JS. Vitamin C deficiency (scurvy). In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Accessed on September 13, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493187/

2. Worral S. A nightmare disease haunted ships during age of discovery. National Geographic. January 15, 2017. Accessed September 21, 2022. www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/scurvy-disease-discovery-jonathan-lamb

3. Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Adult Scurvy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:895-906. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70244-6

4. Schleicher RL, Carroll MD, Ford ES, et al. Serum vitamin C and the prevalence of vitamin C deficiency in the United States: 2003-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1252-1263. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27016

5. Agarwal A, Shaharyar A, Kumar A, et al. Scurvy in pediatric age group – A disease often forgotten? J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2015;6:101-107. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2014.12.003

6. Scurvy and its prevention and control in major emergencies. World Health Organization. February 23, 1999. Accessed September 13, 2022. www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NHD-99.11

7. Weinstein M, Babyn P, Zlotkin S. An orange a day keeps the doctor away: scurvy in the year 2000. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E55. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.e55

1. Maxfield L, Crane JS. Vitamin C deficiency (scurvy). In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Accessed on September 13, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493187/

2. Worral S. A nightmare disease haunted ships during age of discovery. National Geographic. January 15, 2017. Accessed September 21, 2022. www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/scurvy-disease-discovery-jonathan-lamb

3. Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Adult Scurvy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:895-906. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70244-6

4. Schleicher RL, Carroll MD, Ford ES, et al. Serum vitamin C and the prevalence of vitamin C deficiency in the United States: 2003-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1252-1263. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.27016

5. Agarwal A, Shaharyar A, Kumar A, et al. Scurvy in pediatric age group – A disease often forgotten? J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2015;6:101-107. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2014.12.003

6. Scurvy and its prevention and control in major emergencies. World Health Organization. February 23, 1999. Accessed September 13, 2022. www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NHD-99.11

7. Weinstein M, Babyn P, Zlotkin S. An orange a day keeps the doctor away: scurvy in the year 2000. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E55. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.e55

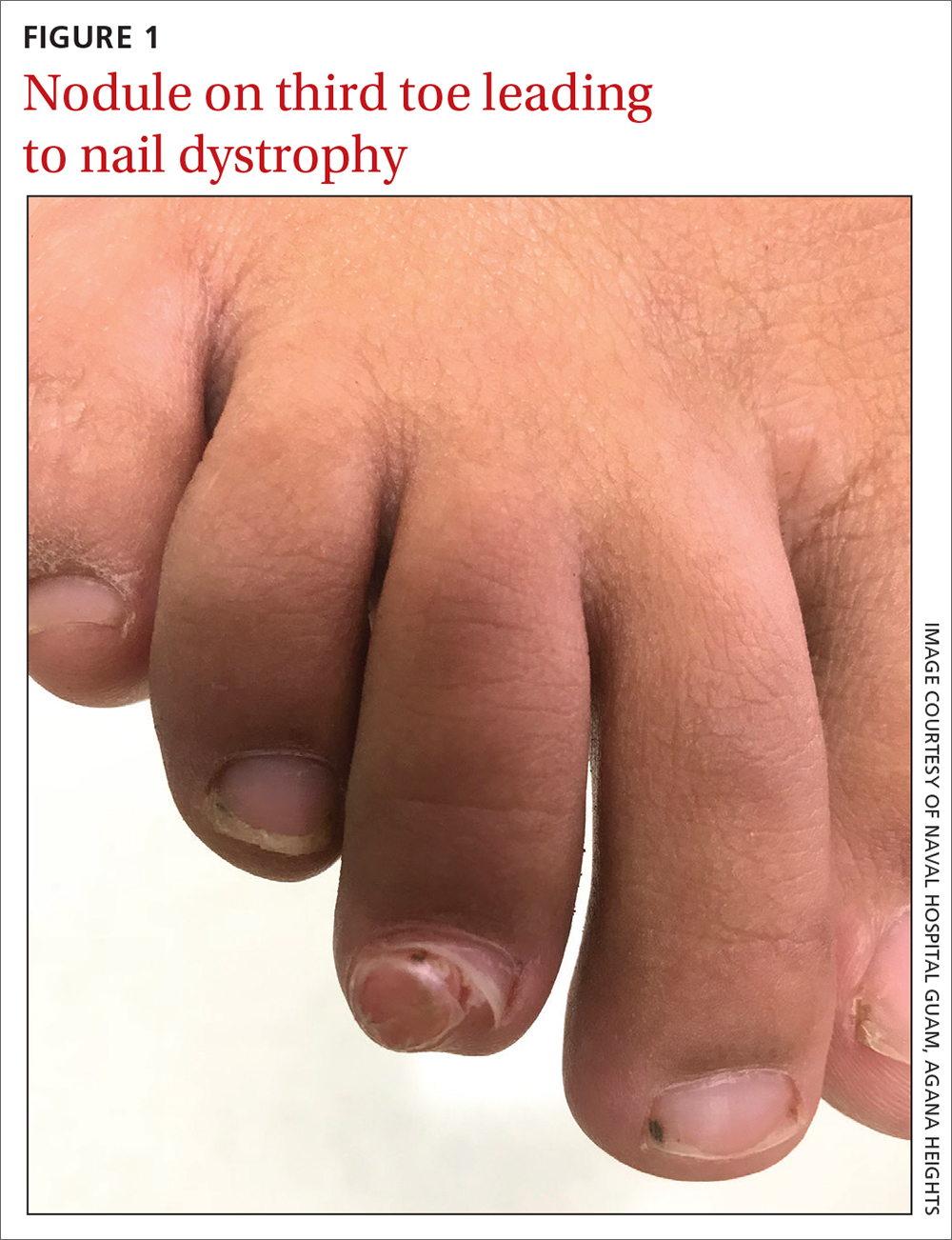

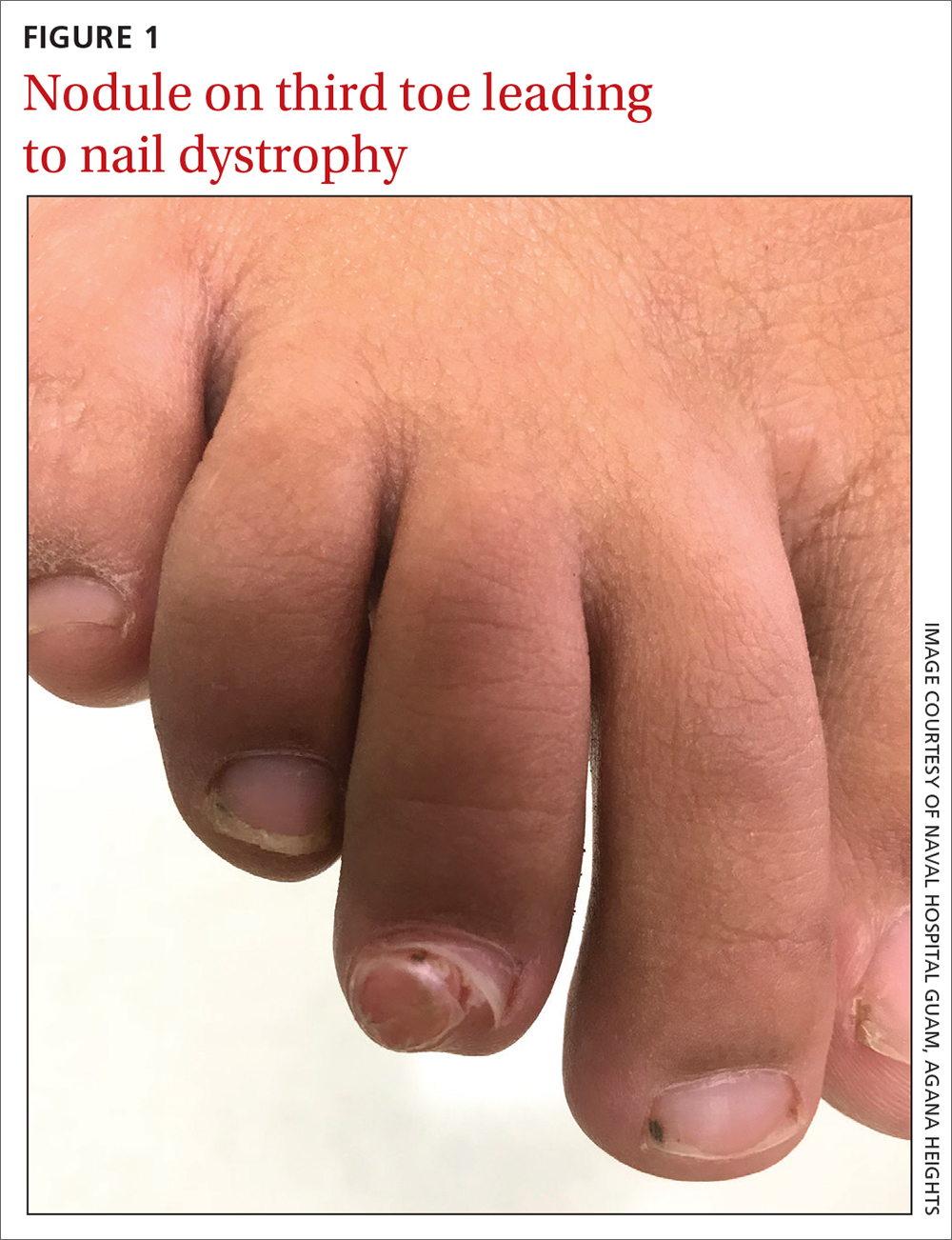

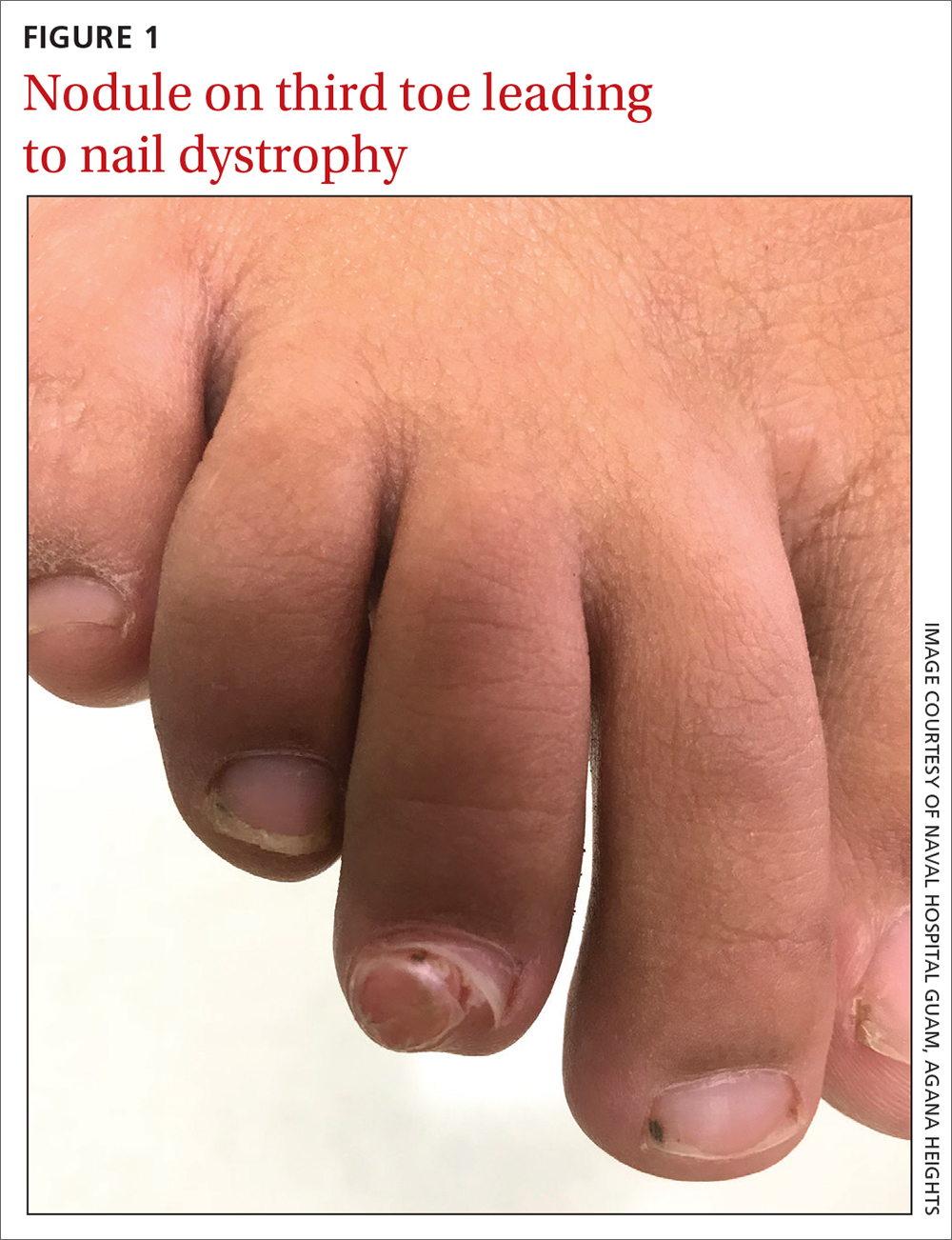

Soccer player with painful toe

A 13-YEAR-OLD GIRL presented to the clinic with a 1-year history of a slow-growing mass on the third toe of her right foot. As a soccer player, she experienced associated pain when kicking the ball or when wearing tight-fitting shoes. The lesion was otherwise asymptomatic. She denied any overt trauma to the area and indicated that the mass had enlarged over the previous year.

On exam, there was a nontender 8 × 8-mm firm nodule underneath the nail with associated nail dystrophy (FIGURE 1). The toe had full mobility, sensation was intact, and capillary refill time was < 2 seconds.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Subungual exostosis

A plain radiograph of the patient’s foot showed continuity with the bony cortex and medullary space, confirming the diagnosis of subungual exostosis (FIGURE 2).1 An exostosis, or osteochondroma, is a form of benign bone tumor in which trabecular bone overgrows its normal border in a nodular pattern. When this occurs under the nail bed, it is called subungual exostosis.2 Exostosis represents 10% to 15% of all benign bone tumors, making it the most common benign bone tumor.3 Generally, the age of occurrence is 10 to 15 years.3

Repetitive trauma can be a culprit. Up to 8% of exostoses occur in the foot, with the most commonly affected area being the distal medial portion of the big toe.3,4 Repetitive trauma and infection are potential risk factors.3,4 The affected toe may be painful, but that is not always the case.4 Typically, lesions are solitary; however, multiple lesions can occur.4

Most pediatric foot lesions are benign and involve soft tissue

Benign soft-tissue masses make up the overwhelming majority of pediatric foot lesions, accounting for 61% to 87% of all foot lesions.3 Malignancies such as chondrosarcoma can occur and can be difficult to diagnose. Rapid growth, family history, size > 5 cm, heterogenous appearance on magnetic resonance imaging, and poorly defined margins are a few characteristics that should increase suspicion for possible malignancy.5

The differential diagnosis for a growth on the toe similar to the one our patient had would include pyogenic granuloma,

Pyogenic granulomas are benign vascular lesions that occur in patients of all ages. They tend to be dome-shaped and flesh-toned to violaceous red, and they are usually found on the head, neck, and extremities—especially fingers.6 They are associated with trauma and are classically tender with a propensity to bleed.6

Acral fibromyxoma is a benign, slow-growing, predominately painless, firm mass with an affinity for the great toe; the affected area includes the nail in 50% of cases.7 A radiograph may show bony erosion or scalloping due to mass effect; however, there will be no continuity with the bony matrix. (Such continuity would suggest exostosis.)

Periungual fibromas are benign soft-tissue masses, which are pink to red and firm, and emerge from underneath the nails, potentially resulting in dystrophy.8 They can bleed and cause pain, and are strongly associated with tuberous sclerosis.5

Continue to: Verruca vulgaris

Verruca vulgaris, the common wart, can also manifest in the subungual region as a firm, generally painless mass. It is the most common neoplasm of the hand and fingers.6 Tiny black dots that correspond to thrombosed capillaries are key to identifying this lesion.

Surgical excision when patient reaches maturity

The definitive treatment for subungual exostosis is surgical excision, preferably once the patient has reached skeletal maturity. Surgery at this point is associated with decreased recurrence rates.3,4 That said, excision may need to be performed sooner if the lesion is painful and leading to deformity.3

Our patient’s persistent pain prompted us to recommend surgical excision. She underwent a third digit exostectomy, which she tolerated without any issues. The patient was fitted with a postoperative shoe that she wore until her 2-week follow-up appointment, when her sutures were removed. The patient’s activity level progressed as tolerated. She regained full function and returned to playing soccer, without any pain, 3 months after her surgery.

1. Das PC, Hassan S, Kumar P. Subungual exostosis – clinical, radiological, and histological findings. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2019;10:202-203. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_104_18

2. Yousefian F, Davis B, Browning JC. Pediatric subungual exostosis. Cutis. 2021;108:256-257. doi:10.12788/cutis.0380

3. Bouchard B, Bartlett M, Donnan L. Assessment of the pediatric foot mass. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017;25:32-41. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00397

4. DaCambra MP, Gupta SK, Ferri-de-Barros F. Subungual exostosis of the toes: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:1251-1259. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3345-4

5. Shah SH, Callahan MJ. Ultrasound evaluation of superficial lumps and bumps of the extremities in children: a 5-year retrospective review. Pediatr Radiol. 2013;43 suppl 1:S23-S40. doi: 10.1007/s00247-012-2590-0

6. Habif, Thomas P. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. Mosby/Elsevier, 2016.

7. Ramya C, Nayak C, Tambe S. Superficial acral fibromyxoma. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:457-459. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.185734

8. Ma D, Darling T, Moss J, et al. Histologic variants of periungual fibromas in tuberous sclerosis complex. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:442-444. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.03.002

A 13-YEAR-OLD GIRL presented to the clinic with a 1-year history of a slow-growing mass on the third toe of her right foot. As a soccer player, she experienced associated pain when kicking the ball or when wearing tight-fitting shoes. The lesion was otherwise asymptomatic. She denied any overt trauma to the area and indicated that the mass had enlarged over the previous year.

On exam, there was a nontender 8 × 8-mm firm nodule underneath the nail with associated nail dystrophy (FIGURE 1). The toe had full mobility, sensation was intact, and capillary refill time was < 2 seconds.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Subungual exostosis

A plain radiograph of the patient’s foot showed continuity with the bony cortex and medullary space, confirming the diagnosis of subungual exostosis (FIGURE 2).1 An exostosis, or osteochondroma, is a form of benign bone tumor in which trabecular bone overgrows its normal border in a nodular pattern. When this occurs under the nail bed, it is called subungual exostosis.2 Exostosis represents 10% to 15% of all benign bone tumors, making it the most common benign bone tumor.3 Generally, the age of occurrence is 10 to 15 years.3

Repetitive trauma can be a culprit. Up to 8% of exostoses occur in the foot, with the most commonly affected area being the distal medial portion of the big toe.3,4 Repetitive trauma and infection are potential risk factors.3,4 The affected toe may be painful, but that is not always the case.4 Typically, lesions are solitary; however, multiple lesions can occur.4

Most pediatric foot lesions are benign and involve soft tissue

Benign soft-tissue masses make up the overwhelming majority of pediatric foot lesions, accounting for 61% to 87% of all foot lesions.3 Malignancies such as chondrosarcoma can occur and can be difficult to diagnose. Rapid growth, family history, size > 5 cm, heterogenous appearance on magnetic resonance imaging, and poorly defined margins are a few characteristics that should increase suspicion for possible malignancy.5

The differential diagnosis for a growth on the toe similar to the one our patient had would include pyogenic granuloma,

Pyogenic granulomas are benign vascular lesions that occur in patients of all ages. They tend to be dome-shaped and flesh-toned to violaceous red, and they are usually found on the head, neck, and extremities—especially fingers.6 They are associated with trauma and are classically tender with a propensity to bleed.6

Acral fibromyxoma is a benign, slow-growing, predominately painless, firm mass with an affinity for the great toe; the affected area includes the nail in 50% of cases.7 A radiograph may show bony erosion or scalloping due to mass effect; however, there will be no continuity with the bony matrix. (Such continuity would suggest exostosis.)

Periungual fibromas are benign soft-tissue masses, which are pink to red and firm, and emerge from underneath the nails, potentially resulting in dystrophy.8 They can bleed and cause pain, and are strongly associated with tuberous sclerosis.5

Continue to: Verruca vulgaris

Verruca vulgaris, the common wart, can also manifest in the subungual region as a firm, generally painless mass. It is the most common neoplasm of the hand and fingers.6 Tiny black dots that correspond to thrombosed capillaries are key to identifying this lesion.

Surgical excision when patient reaches maturity

The definitive treatment for subungual exostosis is surgical excision, preferably once the patient has reached skeletal maturity. Surgery at this point is associated with decreased recurrence rates.3,4 That said, excision may need to be performed sooner if the lesion is painful and leading to deformity.3

Our patient’s persistent pain prompted us to recommend surgical excision. She underwent a third digit exostectomy, which she tolerated without any issues. The patient was fitted with a postoperative shoe that she wore until her 2-week follow-up appointment, when her sutures were removed. The patient’s activity level progressed as tolerated. She regained full function and returned to playing soccer, without any pain, 3 months after her surgery.

A 13-YEAR-OLD GIRL presented to the clinic with a 1-year history of a slow-growing mass on the third toe of her right foot. As a soccer player, she experienced associated pain when kicking the ball or when wearing tight-fitting shoes. The lesion was otherwise asymptomatic. She denied any overt trauma to the area and indicated that the mass had enlarged over the previous year.

On exam, there was a nontender 8 × 8-mm firm nodule underneath the nail with associated nail dystrophy (FIGURE 1). The toe had full mobility, sensation was intact, and capillary refill time was < 2 seconds.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Subungual exostosis

A plain radiograph of the patient’s foot showed continuity with the bony cortex and medullary space, confirming the diagnosis of subungual exostosis (FIGURE 2).1 An exostosis, or osteochondroma, is a form of benign bone tumor in which trabecular bone overgrows its normal border in a nodular pattern. When this occurs under the nail bed, it is called subungual exostosis.2 Exostosis represents 10% to 15% of all benign bone tumors, making it the most common benign bone tumor.3 Generally, the age of occurrence is 10 to 15 years.3

Repetitive trauma can be a culprit. Up to 8% of exostoses occur in the foot, with the most commonly affected area being the distal medial portion of the big toe.3,4 Repetitive trauma and infection are potential risk factors.3,4 The affected toe may be painful, but that is not always the case.4 Typically, lesions are solitary; however, multiple lesions can occur.4

Most pediatric foot lesions are benign and involve soft tissue

Benign soft-tissue masses make up the overwhelming majority of pediatric foot lesions, accounting for 61% to 87% of all foot lesions.3 Malignancies such as chondrosarcoma can occur and can be difficult to diagnose. Rapid growth, family history, size > 5 cm, heterogenous appearance on magnetic resonance imaging, and poorly defined margins are a few characteristics that should increase suspicion for possible malignancy.5

The differential diagnosis for a growth on the toe similar to the one our patient had would include pyogenic granuloma,

Pyogenic granulomas are benign vascular lesions that occur in patients of all ages. They tend to be dome-shaped and flesh-toned to violaceous red, and they are usually found on the head, neck, and extremities—especially fingers.6 They are associated with trauma and are classically tender with a propensity to bleed.6

Acral fibromyxoma is a benign, slow-growing, predominately painless, firm mass with an affinity for the great toe; the affected area includes the nail in 50% of cases.7 A radiograph may show bony erosion or scalloping due to mass effect; however, there will be no continuity with the bony matrix. (Such continuity would suggest exostosis.)

Periungual fibromas are benign soft-tissue masses, which are pink to red and firm, and emerge from underneath the nails, potentially resulting in dystrophy.8 They can bleed and cause pain, and are strongly associated with tuberous sclerosis.5

Continue to: Verruca vulgaris

Verruca vulgaris, the common wart, can also manifest in the subungual region as a firm, generally painless mass. It is the most common neoplasm of the hand and fingers.6 Tiny black dots that correspond to thrombosed capillaries are key to identifying this lesion.

Surgical excision when patient reaches maturity

The definitive treatment for subungual exostosis is surgical excision, preferably once the patient has reached skeletal maturity. Surgery at this point is associated with decreased recurrence rates.3,4 That said, excision may need to be performed sooner if the lesion is painful and leading to deformity.3

Our patient’s persistent pain prompted us to recommend surgical excision. She underwent a third digit exostectomy, which she tolerated without any issues. The patient was fitted with a postoperative shoe that she wore until her 2-week follow-up appointment, when her sutures were removed. The patient’s activity level progressed as tolerated. She regained full function and returned to playing soccer, without any pain, 3 months after her surgery.

1. Das PC, Hassan S, Kumar P. Subungual exostosis – clinical, radiological, and histological findings. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2019;10:202-203. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_104_18

2. Yousefian F, Davis B, Browning JC. Pediatric subungual exostosis. Cutis. 2021;108:256-257. doi:10.12788/cutis.0380

3. Bouchard B, Bartlett M, Donnan L. Assessment of the pediatric foot mass. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017;25:32-41. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00397

4. DaCambra MP, Gupta SK, Ferri-de-Barros F. Subungual exostosis of the toes: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:1251-1259. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3345-4

5. Shah SH, Callahan MJ. Ultrasound evaluation of superficial lumps and bumps of the extremities in children: a 5-year retrospective review. Pediatr Radiol. 2013;43 suppl 1:S23-S40. doi: 10.1007/s00247-012-2590-0

6. Habif, Thomas P. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. Mosby/Elsevier, 2016.

7. Ramya C, Nayak C, Tambe S. Superficial acral fibromyxoma. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:457-459. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.185734

8. Ma D, Darling T, Moss J, et al. Histologic variants of periungual fibromas in tuberous sclerosis complex. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:442-444. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.03.002

1. Das PC, Hassan S, Kumar P. Subungual exostosis – clinical, radiological, and histological findings. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2019;10:202-203. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_104_18

2. Yousefian F, Davis B, Browning JC. Pediatric subungual exostosis. Cutis. 2021;108:256-257. doi:10.12788/cutis.0380

3. Bouchard B, Bartlett M, Donnan L. Assessment of the pediatric foot mass. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2017;25:32-41. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-15-00397

4. DaCambra MP, Gupta SK, Ferri-de-Barros F. Subungual exostosis of the toes: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:1251-1259. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3345-4

5. Shah SH, Callahan MJ. Ultrasound evaluation of superficial lumps and bumps of the extremities in children: a 5-year retrospective review. Pediatr Radiol. 2013;43 suppl 1:S23-S40. doi: 10.1007/s00247-012-2590-0

6. Habif, Thomas P. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. Mosby/Elsevier, 2016.

7. Ramya C, Nayak C, Tambe S. Superficial acral fibromyxoma. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:457-459. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.185734

8. Ma D, Darling T, Moss J, et al. Histologic variants of periungual fibromas in tuberous sclerosis complex. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:442-444. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.03.002

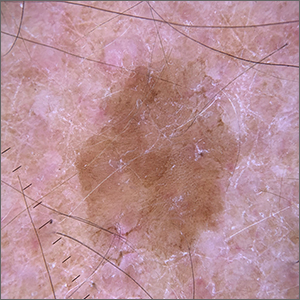

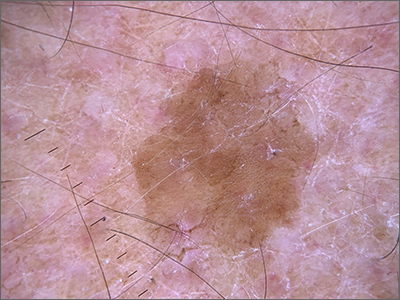

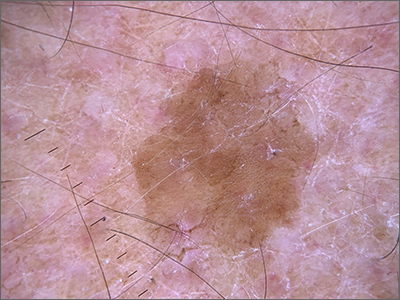

Velvety brown lesion

Dermoscopy revealed a uniform, sharply demarcated, slightly scaly lesion on a background of occasional scale and solar-damaged skin. This appearance, paired with the absence of abnormal blood vessels or suspicious, irregular pigmentation, pointed to a diagnosis of benign lichenoid keratosis also known as lichenoid keratosis (LK) or lichen planus-like keratosis. (It’s worth noting that in some cases, a dermoscopic evaluation will reveal blue-grey dots rather than the uniform, velvety brown pigmentation that was seen here.)

LK is a benign reactive inflammatory lesion that usually manifests as a solitary lesion in middle age. LKs can be found on the trunk or lower extremities. As the alternative name “lichen planus-like keratosis” implies, the lesions can be purple, polygonal, raised, and have stria. The etiology is unknown but thought to be a reaction to a lentigo or another lesion, resulting in an inflammatory infiltrate.1

If dermoscopic evaluation of the lesion is unclear, biopsy is warranted. Maor et al1 reported the pathology results of 263 consecutive patients with a histologic diagnosis of LK. Of those cases, 47% were clinically thought to be basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and 18% were submitted with a diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis.1 The high rate of concern for BCC and not listing a diagnosis of LK may have been the result of clinicians doing biopsies on the atypical lesions and clinically following the typical banal lesions.

At the patient’s request, he was given a written list of the diagnoses of his various skin lesions and advised that his LK was benign and did not require treatment. He was advised to continue coming in for serial skin examinations and report any concerning lesions in the interim.

Image and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Maor D, Ondhia C, Yu LL, et al. Lichenoid keratosis is frequently misdiagnosed as basal cell carcinoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:663-666. doi: 10.1111/ced.13178

Dermoscopy revealed a uniform, sharply demarcated, slightly scaly lesion on a background of occasional scale and solar-damaged skin. This appearance, paired with the absence of abnormal blood vessels or suspicious, irregular pigmentation, pointed to a diagnosis of benign lichenoid keratosis also known as lichenoid keratosis (LK) or lichen planus-like keratosis. (It’s worth noting that in some cases, a dermoscopic evaluation will reveal blue-grey dots rather than the uniform, velvety brown pigmentation that was seen here.)

LK is a benign reactive inflammatory lesion that usually manifests as a solitary lesion in middle age. LKs can be found on the trunk or lower extremities. As the alternative name “lichen planus-like keratosis” implies, the lesions can be purple, polygonal, raised, and have stria. The etiology is unknown but thought to be a reaction to a lentigo or another lesion, resulting in an inflammatory infiltrate.1

If dermoscopic evaluation of the lesion is unclear, biopsy is warranted. Maor et al1 reported the pathology results of 263 consecutive patients with a histologic diagnosis of LK. Of those cases, 47% were clinically thought to be basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and 18% were submitted with a diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis.1 The high rate of concern for BCC and not listing a diagnosis of LK may have been the result of clinicians doing biopsies on the atypical lesions and clinically following the typical banal lesions.

At the patient’s request, he was given a written list of the diagnoses of his various skin lesions and advised that his LK was benign and did not require treatment. He was advised to continue coming in for serial skin examinations and report any concerning lesions in the interim.

Image and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

Dermoscopy revealed a uniform, sharply demarcated, slightly scaly lesion on a background of occasional scale and solar-damaged skin. This appearance, paired with the absence of abnormal blood vessels or suspicious, irregular pigmentation, pointed to a diagnosis of benign lichenoid keratosis also known as lichenoid keratosis (LK) or lichen planus-like keratosis. (It’s worth noting that in some cases, a dermoscopic evaluation will reveal blue-grey dots rather than the uniform, velvety brown pigmentation that was seen here.)

LK is a benign reactive inflammatory lesion that usually manifests as a solitary lesion in middle age. LKs can be found on the trunk or lower extremities. As the alternative name “lichen planus-like keratosis” implies, the lesions can be purple, polygonal, raised, and have stria. The etiology is unknown but thought to be a reaction to a lentigo or another lesion, resulting in an inflammatory infiltrate.1

If dermoscopic evaluation of the lesion is unclear, biopsy is warranted. Maor et al1 reported the pathology results of 263 consecutive patients with a histologic diagnosis of LK. Of those cases, 47% were clinically thought to be basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and 18% were submitted with a diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis.1 The high rate of concern for BCC and not listing a diagnosis of LK may have been the result of clinicians doing biopsies on the atypical lesions and clinically following the typical banal lesions.

At the patient’s request, he was given a written list of the diagnoses of his various skin lesions and advised that his LK was benign and did not require treatment. He was advised to continue coming in for serial skin examinations and report any concerning lesions in the interim.

Image and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Maor D, Ondhia C, Yu LL, et al. Lichenoid keratosis is frequently misdiagnosed as basal cell carcinoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:663-666. doi: 10.1111/ced.13178

1. Maor D, Ondhia C, Yu LL, et al. Lichenoid keratosis is frequently misdiagnosed as basal cell carcinoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017;42:663-666. doi: 10.1111/ced.13178

Recurrent drainage from an old gunshot wound

An x-ray revealed a metal density in the area of concern that was consistent with a bullet fragment or other metallic foreign body. Since there were no lucencies on x-ray or tracking from the area of concern to the metacarpal, the diagnosis was confirmed as an infected foreign body. The history was very concerning for osteomyelitis, given that the patient had sustained a GSW and had undergone surgical repair with hardware. (Shifting hardware can also lead to callus formation and skin breakdown.)

The patient was told that he’d retained a bullet fragment or foreign body that caused a chronic infection and the recurrent drainage. In addition, the hardware spanning the gap between the remnants of his proximal and distal metacarpal had broken as a result of fatigue. He was referred to a surgeon to remove the foreign body and treat the infection. The patient was advised that he might also need replacement hardware and a bone graft.

Images and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

An x-ray revealed a metal density in the area of concern that was consistent with a bullet fragment or other metallic foreign body. Since there were no lucencies on x-ray or tracking from the area of concern to the metacarpal, the diagnosis was confirmed as an infected foreign body. The history was very concerning for osteomyelitis, given that the patient had sustained a GSW and had undergone surgical repair with hardware. (Shifting hardware can also lead to callus formation and skin breakdown.)

The patient was told that he’d retained a bullet fragment or foreign body that caused a chronic infection and the recurrent drainage. In addition, the hardware spanning the gap between the remnants of his proximal and distal metacarpal had broken as a result of fatigue. He was referred to a surgeon to remove the foreign body and treat the infection. The patient was advised that he might also need replacement hardware and a bone graft.

Images and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

An x-ray revealed a metal density in the area of concern that was consistent with a bullet fragment or other metallic foreign body. Since there were no lucencies on x-ray or tracking from the area of concern to the metacarpal, the diagnosis was confirmed as an infected foreign body. The history was very concerning for osteomyelitis, given that the patient had sustained a GSW and had undergone surgical repair with hardware. (Shifting hardware can also lead to callus formation and skin breakdown.)

The patient was told that he’d retained a bullet fragment or foreign body that caused a chronic infection and the recurrent drainage. In addition, the hardware spanning the gap between the remnants of his proximal and distal metacarpal had broken as a result of fatigue. He was referred to a surgeon to remove the foreign body and treat the infection. The patient was advised that he might also need replacement hardware and a bone graft.

Images and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

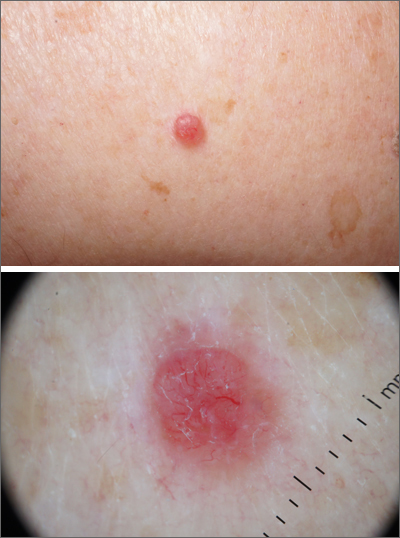

Fast growing hand lesion

A scoop shave biopsy at the lower edge of the lesion revealed that this was a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma.

Squamous cell carcinoma is the second most common cancer in the United States and the most common skin cancer in Black people.1 A patient’s age and their accumulated UV radiation from sun exposure or artificial tanning is a major contributing factor. Lesions may manifest as precancers characterized as rough pink or brown papules with a sandpaper-like texture on sun-exposed skin. These lesions may clear spontaneously or develop into invasive disease, as occurred in this case.

Surgical treatment is often curative. Fusiform excision and Mohs micrographic surgery are 2 common options. More advanced squamous cell carcinomas that are large or found to have poorly differentiated cells or large perineural invasion carry a risk of metastasis.

In elderly patients, optimal treatment isn’t always straightforward.1 Nonsurgical options include radiation and intralesional chemotherapy. These nonsurgical choices may seem less aggressive, but total inconvenience, wound care, and discomfort can be equal to or worse than a single session of curative surgery.

This patient’s lesion was excised with a 5-mm margin. The patient tolerated an in-office procedure lasting about 45 minutes but would have struggled with a longer session with Mohs microsurgery. The postoperative period required limiting full use of his left hand for about 2 weeks.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Bradford PT. Skin cancer in skin of color. Dermatol Nurs. 2009;21:170-177, 206; quiz 178. 2. Renzi M Jr, Schimmel J, Decker A, et al. Management of skin cancer in the elderly. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:279-286. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2019.02.003

A scoop shave biopsy at the lower edge of the lesion revealed that this was a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma.

Squamous cell carcinoma is the second most common cancer in the United States and the most common skin cancer in Black people.1 A patient’s age and their accumulated UV radiation from sun exposure or artificial tanning is a major contributing factor. Lesions may manifest as precancers characterized as rough pink or brown papules with a sandpaper-like texture on sun-exposed skin. These lesions may clear spontaneously or develop into invasive disease, as occurred in this case.

Surgical treatment is often curative. Fusiform excision and Mohs micrographic surgery are 2 common options. More advanced squamous cell carcinomas that are large or found to have poorly differentiated cells or large perineural invasion carry a risk of metastasis.

In elderly patients, optimal treatment isn’t always straightforward.1 Nonsurgical options include radiation and intralesional chemotherapy. These nonsurgical choices may seem less aggressive, but total inconvenience, wound care, and discomfort can be equal to or worse than a single session of curative surgery.

This patient’s lesion was excised with a 5-mm margin. The patient tolerated an in-office procedure lasting about 45 minutes but would have struggled with a longer session with Mohs microsurgery. The postoperative period required limiting full use of his left hand for about 2 weeks.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

A scoop shave biopsy at the lower edge of the lesion revealed that this was a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma.

Squamous cell carcinoma is the second most common cancer in the United States and the most common skin cancer in Black people.1 A patient’s age and their accumulated UV radiation from sun exposure or artificial tanning is a major contributing factor. Lesions may manifest as precancers characterized as rough pink or brown papules with a sandpaper-like texture on sun-exposed skin. These lesions may clear spontaneously or develop into invasive disease, as occurred in this case.

Surgical treatment is often curative. Fusiform excision and Mohs micrographic surgery are 2 common options. More advanced squamous cell carcinomas that are large or found to have poorly differentiated cells or large perineural invasion carry a risk of metastasis.

In elderly patients, optimal treatment isn’t always straightforward.1 Nonsurgical options include radiation and intralesional chemotherapy. These nonsurgical choices may seem less aggressive, but total inconvenience, wound care, and discomfort can be equal to or worse than a single session of curative surgery.

This patient’s lesion was excised with a 5-mm margin. The patient tolerated an in-office procedure lasting about 45 minutes but would have struggled with a longer session with Mohs microsurgery. The postoperative period required limiting full use of his left hand for about 2 weeks.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Bradford PT. Skin cancer in skin of color. Dermatol Nurs. 2009;21:170-177, 206; quiz 178. 2. Renzi M Jr, Schimmel J, Decker A, et al. Management of skin cancer in the elderly. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:279-286. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2019.02.003

1. Bradford PT. Skin cancer in skin of color. Dermatol Nurs. 2009;21:170-177, 206; quiz 178. 2. Renzi M Jr, Schimmel J, Decker A, et al. Management of skin cancer in the elderly. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:279-286. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2019.02.003