User login

Blisters on face

The child had bullous impetigo, which is usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus.

This is one variant of impetigo, a superficial bacterial infection of the skin. Impetigo is more common in children and is often found around the nose and mouth (as seen in this case). The honey crusts are typical of impetigo. Bullae are less common and should be a tip off that S. aureus is involved.

Given the frequency with which we see cases of community-acquired methicillin-resistant staphylococcal aureus (MRSA), it is probably best to culture all but the most limited cases of impetigo. Community-acquired MRSA can present as bullous impetigo in children or adults. If you suspect MRSA, culture the lesions and start one of the following oral antibiotics: trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or clindamycin (tetracycline or doxycycline should be reserved for adults and children older than 12 years of age). Clindamycin has the advantage of covering group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus pyogenes (GABHS) and most MRSA. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole has excellent MRSA coverage and, like clindamycin, comes in a liquid form for children. Seven to 10 days of antibiotics should be adequate to clear impetigo caused by MRSA.

There is good evidence that topical mupirocin is equally—or more—effective than oral treatment for people with limited impetigo. Mupirocin also covers MRSA. Extensive impetigo not caused by MRSA could be treated for 7 days with antibiotics that cover GABHS and S. aureus such as cephalexin or dicloxacillin. If there are recurrent MRSA infections, one might choose to prescribe intranasal mupirocin ointment and chlorhexidine bathing to decrease MRSA colonization.

The family physician diagnosed bullous impetigo and suspected MRSA. A culture confirmed this 3 days later. Fortunately the physician chose to start the child on oral clindamycin and there was significant improvement by the time the culture came back positive. The physician also discussed hygiene issues with the mother and how to avoid spread within the household.

Photo courtesy of Jack Resneck, Sr, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Sauceda AT, Usatine R. Bullous diseases—overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:784-789.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The Color Atlas of Family Medicine is also available as an app for mobile devices. See

The child had bullous impetigo, which is usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus.

This is one variant of impetigo, a superficial bacterial infection of the skin. Impetigo is more common in children and is often found around the nose and mouth (as seen in this case). The honey crusts are typical of impetigo. Bullae are less common and should be a tip off that S. aureus is involved.

Given the frequency with which we see cases of community-acquired methicillin-resistant staphylococcal aureus (MRSA), it is probably best to culture all but the most limited cases of impetigo. Community-acquired MRSA can present as bullous impetigo in children or adults. If you suspect MRSA, culture the lesions and start one of the following oral antibiotics: trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or clindamycin (tetracycline or doxycycline should be reserved for adults and children older than 12 years of age). Clindamycin has the advantage of covering group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus pyogenes (GABHS) and most MRSA. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole has excellent MRSA coverage and, like clindamycin, comes in a liquid form for children. Seven to 10 days of antibiotics should be adequate to clear impetigo caused by MRSA.

There is good evidence that topical mupirocin is equally—or more—effective than oral treatment for people with limited impetigo. Mupirocin also covers MRSA. Extensive impetigo not caused by MRSA could be treated for 7 days with antibiotics that cover GABHS and S. aureus such as cephalexin or dicloxacillin. If there are recurrent MRSA infections, one might choose to prescribe intranasal mupirocin ointment and chlorhexidine bathing to decrease MRSA colonization.

The family physician diagnosed bullous impetigo and suspected MRSA. A culture confirmed this 3 days later. Fortunately the physician chose to start the child on oral clindamycin and there was significant improvement by the time the culture came back positive. The physician also discussed hygiene issues with the mother and how to avoid spread within the household.

Photo courtesy of Jack Resneck, Sr, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Sauceda AT, Usatine R. Bullous diseases—overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:784-789.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The Color Atlas of Family Medicine is also available as an app for mobile devices. See

The child had bullous impetigo, which is usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus.

This is one variant of impetigo, a superficial bacterial infection of the skin. Impetigo is more common in children and is often found around the nose and mouth (as seen in this case). The honey crusts are typical of impetigo. Bullae are less common and should be a tip off that S. aureus is involved.

Given the frequency with which we see cases of community-acquired methicillin-resistant staphylococcal aureus (MRSA), it is probably best to culture all but the most limited cases of impetigo. Community-acquired MRSA can present as bullous impetigo in children or adults. If you suspect MRSA, culture the lesions and start one of the following oral antibiotics: trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or clindamycin (tetracycline or doxycycline should be reserved for adults and children older than 12 years of age). Clindamycin has the advantage of covering group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus pyogenes (GABHS) and most MRSA. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole has excellent MRSA coverage and, like clindamycin, comes in a liquid form for children. Seven to 10 days of antibiotics should be adequate to clear impetigo caused by MRSA.

There is good evidence that topical mupirocin is equally—or more—effective than oral treatment for people with limited impetigo. Mupirocin also covers MRSA. Extensive impetigo not caused by MRSA could be treated for 7 days with antibiotics that cover GABHS and S. aureus such as cephalexin or dicloxacillin. If there are recurrent MRSA infections, one might choose to prescribe intranasal mupirocin ointment and chlorhexidine bathing to decrease MRSA colonization.

The family physician diagnosed bullous impetigo and suspected MRSA. A culture confirmed this 3 days later. Fortunately the physician chose to start the child on oral clindamycin and there was significant improvement by the time the culture came back positive. The physician also discussed hygiene issues with the mother and how to avoid spread within the household.

Photo courtesy of Jack Resneck, Sr, MD. Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Sauceda AT, Usatine R. Bullous diseases—overview. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:784-789.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

• http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The Color Atlas of Family Medicine is also available as an app for mobile devices. See

Varicelliform eruption

The physician diagnosed pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) by clinical appearance and then performed a punch biopsy to confirm the diagnosis.

PLEVA usually presents as a papulonecrotic eruption, but may have vesicles resembling varicella. It can be thought of as “chickenpox that lasts for weeks to months” because new crops of lesions continue to appear. Always suspect PLEVA when a case of “chickenpox” is not going away. A punch biopsy is helpful in making the diagnosis.

PLEVA usually involves the anterior trunk, flexor surfaces of the upper extremities, and the axilla. The eruptions can occur in crops of vesicles that can become hemorrhagic over several weeks or months.

The general health of the patient is unaffected, although most have lymphadenopathy. CD8 T-cells are the predominant cell-type in lesional skin. It is seen more frequently in young men and can go on to become chronic (pityriasis lichenoides chronica).

Various reports suggest the efficacy of macrolides and tetracyclines, probably more for their antiinflammatory properties than for their antibacterial effects. The physician prescribed a one-month course of oral tetracycline 500 mg 4 times daily and the patient’s skin cleared.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Hara J, Usatine R. Other bullous diseases. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:799-805.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The Color Atlas of Family Medicine is also available as an app for mobile devices. See

The physician diagnosed pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) by clinical appearance and then performed a punch biopsy to confirm the diagnosis.

PLEVA usually presents as a papulonecrotic eruption, but may have vesicles resembling varicella. It can be thought of as “chickenpox that lasts for weeks to months” because new crops of lesions continue to appear. Always suspect PLEVA when a case of “chickenpox” is not going away. A punch biopsy is helpful in making the diagnosis.

PLEVA usually involves the anterior trunk, flexor surfaces of the upper extremities, and the axilla. The eruptions can occur in crops of vesicles that can become hemorrhagic over several weeks or months.

The general health of the patient is unaffected, although most have lymphadenopathy. CD8 T-cells are the predominant cell-type in lesional skin. It is seen more frequently in young men and can go on to become chronic (pityriasis lichenoides chronica).

Various reports suggest the efficacy of macrolides and tetracyclines, probably more for their antiinflammatory properties than for their antibacterial effects. The physician prescribed a one-month course of oral tetracycline 500 mg 4 times daily and the patient’s skin cleared.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Hara J, Usatine R. Other bullous diseases. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:799-805.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The Color Atlas of Family Medicine is also available as an app for mobile devices. See

The physician diagnosed pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) by clinical appearance and then performed a punch biopsy to confirm the diagnosis.

PLEVA usually presents as a papulonecrotic eruption, but may have vesicles resembling varicella. It can be thought of as “chickenpox that lasts for weeks to months” because new crops of lesions continue to appear. Always suspect PLEVA when a case of “chickenpox” is not going away. A punch biopsy is helpful in making the diagnosis.

PLEVA usually involves the anterior trunk, flexor surfaces of the upper extremities, and the axilla. The eruptions can occur in crops of vesicles that can become hemorrhagic over several weeks or months.

The general health of the patient is unaffected, although most have lymphadenopathy. CD8 T-cells are the predominant cell-type in lesional skin. It is seen more frequently in young men and can go on to become chronic (pityriasis lichenoides chronica).

Various reports suggest the efficacy of macrolides and tetracyclines, probably more for their antiinflammatory properties than for their antibacterial effects. The physician prescribed a one-month course of oral tetracycline 500 mg 4 times daily and the patient’s skin cleared.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Hara J, Usatine R. Other bullous diseases. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:799-805.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The Color Atlas of Family Medicine is also available as an app for mobile devices. See

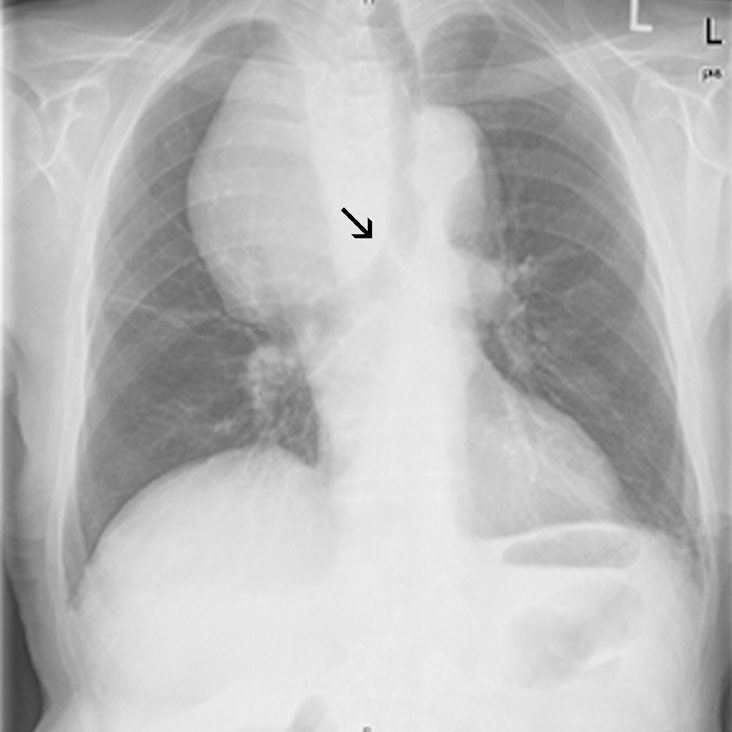

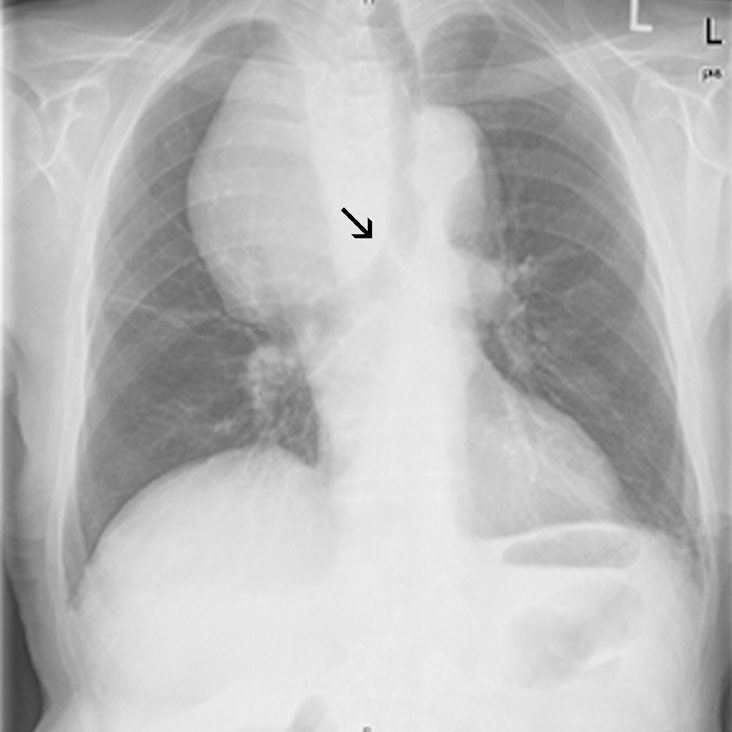

Unexpected skin necrosis of the thighs

A 62-YEAR-OLD WOMAN sought care at our clinic for painful skin lesions that had developed on her thighs 5 days earlier. She had received ongoing treatment at our clinic over the past few years for diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and sarcoidosis. In the last 2 years, she’d had 2 hospitalizations for acute renal failure, with a creatinine value as high as 3.8 mg/dL and a persistent glomerular filtration rate consistent with stage 3 chronic kidney disease.

The medications she was taking included glyburide, pravastatin, and lisinopril. During the 2 years prior to her recent clinic visit, she’d had some intermittently elevated calcium readings. Repeat calcium levels each time were normal. In addition, her parathyroid hormone levels fluctuated between low, high, and normal. Her technetium sestamibi scan was negative for hyperparathyroidism. The patient was unemployed and gave no history of recent travel, injuries, or exposure to animals.

On examination, we noted large, poorly demarcated, warm, indurated erythematous lesions on her lateral thighs. She was given a diagnosis of cellulitis and treated with trimethoprim/sulfa-methoxazole 160/800 mg twice daily for 10 days. During follow-up visits 3 and 7 days later, she indicated that the lesions were less painful and they appeared to be less swollen.

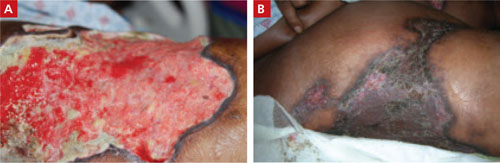

Three weeks later, the patient returned to the clinic with skin sloughing that had produced necrotic lesions with black es-char on the bases (FIGURE 1). In addition, new lesions appeared on her anterior thighs. An initial punch biopsy of the lesions revealed no significant pathologic abnormality.

FIGURE 1

What started as indurated plaques…

The patient initially came in for the treatment of indurated plaques, which developed into ulcerative skin lesions with erythematous edges and eschar on the bases.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Calciphylaxis

Calciphylaxis is an uncommon disorder of vascular calcification and thrombosis resulting in skin necrosis.1 It most commonly occurs in people with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) on hemodialysis, but in nonuremic patients the most frequent cause is primary hyperparathyroidism.2,3 Similar vascular calcifications may be observed in milk alkali syndrome, rickets, collagen diseases, and hypervitaminosis D. Progression to necrosis in these cases is extremely rare.1 There are only a few documented cases of calciphylaxis associated with sarcoidosis, hypercalcemia, and non-ESRD.4

Female sex and diabetes appear to be risk factors.2 The presence of autoimmune disorders is a major feature in patients without ESRD.2,5 Although this patient did not have a previously diagnosed autoimmune disorder, an antinuclear antibody (ANA) test and lupus anticoagulant values were later found to be positive. In patients with autoimmune disorders, prednisone administration is associated with an increased risk of calciphylaxis.5 A hypercoagulable state can also underlie development of calciphylaxis. Our patient did have a mild protein C and S deficiency.

The prognosis of patients diagnosed with calciphylaxis is very poor. The mortality rate is reported to be as high as 60% to 80%.6

4 other possibilities comprise the differential diagnosis

Several conditions may present with erythema or necrosis similar to that of calciphylaxis (TABLE).

Warfarin-induced skin necrosis may produce hemorrhagic bullae and necrotic eschar, but generally presents within 3 to 10 days of initiating warfarin therapy.7 Severe dermatologic manifestations tend to affect the breasts, buttocks, and thighs.

Cutaneous anthrax causes painless necrotic lesions with black eschar, but is linked to bioterrorism or contact with infected animals. Constitutional symptoms such as fever, chills, and malaise are often present. Skin lesions are located primarily on the face, neck, and upper extremities.

Cholesterol embolization results from cholesterol crystals detaching and obstructing smaller arteries. Skin involvement includes livedo reticularis, petechiae, purpura, and ulcerations.

Vasculitis can affect all sizes of blood vessels. It can occur as a complication of connective tissue disorders, viral infections such as hepatitis B and C, or hypersensitivity reactions to medications such as penicillins and cephalosporins. Systemic symptoms are common, as is palpable purpura. Tissue biopsy is important for diagnosis and reveals blood vessel inflammation, not vessel wall calcification.

TABLE

Is it calciphylaxis or something else?1,3,7-9

| Condition | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Warfarin-induced skin necrosis | Painful, erythematous, edematous lesions; rapidly progressive; petechiae, hemorrhagic bullae, then necrotic eschar |

| Cutaneous anthrax | Small painless, pruritic papules; advances to bullae; finally erodes to painless necrotic lesions with black eschar |

| Cholesterol embolization | Majority with livedo reticularis, cyanosis, or gangrene; smaller percentage with cutaneous ulceration, purpura, petechiae, or painful, firm erythematous nodules |

| Vasculitis | Palpable purpura; biopsy of most affected area is necessary for diagnosis |

| Calciphylaxis | Painful erythematous papules, plaques, nodules, or ulcerations in areas with high adiposity; may progress to necrosis |

What to do when the biopsy isn’t helpful

This case points out an important pathologic rule: If the biopsy doesn’t correlate with the observed disease, additional biopsies are indicated. Calciphylaxis is diagnosed on tissue microscopy, but the initial punch biopsy of the lesion revealed no significant pathologic abnormality. However, a subsequent deep-tissue biopsy showed extensive vascular wall calcification and septal fibrosis with subcutaneous fat necrosis.

Repeating abnormal laboratory testing is often appropriate, too. However, in this patient’s case, it probably would not have been helpful because she had intermittently elevated calcium levels over the years.

Wound cultures are often inaccurate in identifying a causative agent and this patient did not appear to have acute infection.

Management is mainly supportive

If you have a patient with calciphylaxis, address predisposing conditions such as hyperparathyroidism, hypercalcemia, and renal dysfunction5 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C). In addition, discontinue calcium and vitamin D supplementation6 (SOR: C).

Finally, the patient will need meticulous wound care with adequate pain control; special attention to prevention of secondary infection is essential1,6 (SOR: C).

Our patient was one of the lucky ones

We treated this patient’s hypercalcemia, which was noted on admission to the hospital, with zoledronate and corrected her hypophosphatemia. Her renal function significantly improved with aggressive hydration.

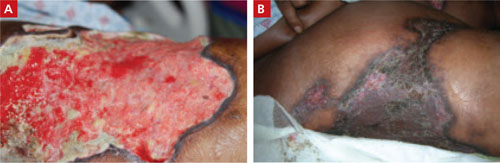

With correction of electrolytes and normalization of kidney function, lesion progression was arrested. Granulation tissue developed in the lesions and split-thickness expanded skin grafts were performed on the large lesions (FIGURE 2). Fortunately, this patient survived despite the usual high rate of mortality. JFP

FIGURE 2

Good granulation beds, followed by closure

After aggressive treatment of renal dysfunction, correction of electrolyte abnormalities, and meticulous wound care, the patient’s lesions developed good granulation beds and showed signs of healing (A). The second image (B), taken 9 months after the patient first sought treatment for the lesions, shows the wounds after skin grafting.

CORRESPONDENCE

E.J. Mayeaux, Jr, MD, DABFP, FAAFP, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, 1501 Kings Highway, Shreveport, LA 71130; [email protected]

1. Kent RB 3rd, Lylerly RT. Systemic calciphylaxis. South Med J. 1994;87:278-281.

2. Nigwekar SU, Wolf M, Sterns RH, et al. Calciphylaxis from nonuremic causes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1139-1143.

3. Fine A, Zacharias J. Calciphylaxis is usually non-ulcerating. Kidney Int. 2002;61:2210-2217.

4. Swanson AM, Desai SR, Jackson JD, et al. Calciphylaxis associated with chronic inflammatory conditions, immunosuppression therapy, and normal renal function: a report of 2 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:723-725.

5. Weenig RH, Sewell LD, Davis MD, et al. Calciphylaxis: natural history, risk factor analysis, and outcome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:569-579.

6. Al-Hwiesh AK. Calciphylaxis of both proximal and distal distribution. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2008;19:82-86.

7. Renick AM Jr. Anticoagulant-induced necrosis of skin and sub-cutaneous tissues. South Med J. 1976;69:775-778, 804.

8. Wenner KA, Kenner JR. Anthrax. Dermatol Clin. 2004;22:247-256.

9. Falanga V, Fine MJ, Kapoor WN. The cutaneous manifestations of cholesterol crystal embolization. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:1194-1198.

A 62-YEAR-OLD WOMAN sought care at our clinic for painful skin lesions that had developed on her thighs 5 days earlier. She had received ongoing treatment at our clinic over the past few years for diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and sarcoidosis. In the last 2 years, she’d had 2 hospitalizations for acute renal failure, with a creatinine value as high as 3.8 mg/dL and a persistent glomerular filtration rate consistent with stage 3 chronic kidney disease.

The medications she was taking included glyburide, pravastatin, and lisinopril. During the 2 years prior to her recent clinic visit, she’d had some intermittently elevated calcium readings. Repeat calcium levels each time were normal. In addition, her parathyroid hormone levels fluctuated between low, high, and normal. Her technetium sestamibi scan was negative for hyperparathyroidism. The patient was unemployed and gave no history of recent travel, injuries, or exposure to animals.

On examination, we noted large, poorly demarcated, warm, indurated erythematous lesions on her lateral thighs. She was given a diagnosis of cellulitis and treated with trimethoprim/sulfa-methoxazole 160/800 mg twice daily for 10 days. During follow-up visits 3 and 7 days later, she indicated that the lesions were less painful and they appeared to be less swollen.

Three weeks later, the patient returned to the clinic with skin sloughing that had produced necrotic lesions with black es-char on the bases (FIGURE 1). In addition, new lesions appeared on her anterior thighs. An initial punch biopsy of the lesions revealed no significant pathologic abnormality.

FIGURE 1

What started as indurated plaques…

The patient initially came in for the treatment of indurated plaques, which developed into ulcerative skin lesions with erythematous edges and eschar on the bases.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Calciphylaxis

Calciphylaxis is an uncommon disorder of vascular calcification and thrombosis resulting in skin necrosis.1 It most commonly occurs in people with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) on hemodialysis, but in nonuremic patients the most frequent cause is primary hyperparathyroidism.2,3 Similar vascular calcifications may be observed in milk alkali syndrome, rickets, collagen diseases, and hypervitaminosis D. Progression to necrosis in these cases is extremely rare.1 There are only a few documented cases of calciphylaxis associated with sarcoidosis, hypercalcemia, and non-ESRD.4

Female sex and diabetes appear to be risk factors.2 The presence of autoimmune disorders is a major feature in patients without ESRD.2,5 Although this patient did not have a previously diagnosed autoimmune disorder, an antinuclear antibody (ANA) test and lupus anticoagulant values were later found to be positive. In patients with autoimmune disorders, prednisone administration is associated with an increased risk of calciphylaxis.5 A hypercoagulable state can also underlie development of calciphylaxis. Our patient did have a mild protein C and S deficiency.

The prognosis of patients diagnosed with calciphylaxis is very poor. The mortality rate is reported to be as high as 60% to 80%.6

4 other possibilities comprise the differential diagnosis

Several conditions may present with erythema or necrosis similar to that of calciphylaxis (TABLE).

Warfarin-induced skin necrosis may produce hemorrhagic bullae and necrotic eschar, but generally presents within 3 to 10 days of initiating warfarin therapy.7 Severe dermatologic manifestations tend to affect the breasts, buttocks, and thighs.

Cutaneous anthrax causes painless necrotic lesions with black eschar, but is linked to bioterrorism or contact with infected animals. Constitutional symptoms such as fever, chills, and malaise are often present. Skin lesions are located primarily on the face, neck, and upper extremities.

Cholesterol embolization results from cholesterol crystals detaching and obstructing smaller arteries. Skin involvement includes livedo reticularis, petechiae, purpura, and ulcerations.

Vasculitis can affect all sizes of blood vessels. It can occur as a complication of connective tissue disorders, viral infections such as hepatitis B and C, or hypersensitivity reactions to medications such as penicillins and cephalosporins. Systemic symptoms are common, as is palpable purpura. Tissue biopsy is important for diagnosis and reveals blood vessel inflammation, not vessel wall calcification.

TABLE

Is it calciphylaxis or something else?1,3,7-9

| Condition | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Warfarin-induced skin necrosis | Painful, erythematous, edematous lesions; rapidly progressive; petechiae, hemorrhagic bullae, then necrotic eschar |

| Cutaneous anthrax | Small painless, pruritic papules; advances to bullae; finally erodes to painless necrotic lesions with black eschar |

| Cholesterol embolization | Majority with livedo reticularis, cyanosis, or gangrene; smaller percentage with cutaneous ulceration, purpura, petechiae, or painful, firm erythematous nodules |

| Vasculitis | Palpable purpura; biopsy of most affected area is necessary for diagnosis |

| Calciphylaxis | Painful erythematous papules, plaques, nodules, or ulcerations in areas with high adiposity; may progress to necrosis |

What to do when the biopsy isn’t helpful

This case points out an important pathologic rule: If the biopsy doesn’t correlate with the observed disease, additional biopsies are indicated. Calciphylaxis is diagnosed on tissue microscopy, but the initial punch biopsy of the lesion revealed no significant pathologic abnormality. However, a subsequent deep-tissue biopsy showed extensive vascular wall calcification and septal fibrosis with subcutaneous fat necrosis.

Repeating abnormal laboratory testing is often appropriate, too. However, in this patient’s case, it probably would not have been helpful because she had intermittently elevated calcium levels over the years.

Wound cultures are often inaccurate in identifying a causative agent and this patient did not appear to have acute infection.

Management is mainly supportive

If you have a patient with calciphylaxis, address predisposing conditions such as hyperparathyroidism, hypercalcemia, and renal dysfunction5 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C). In addition, discontinue calcium and vitamin D supplementation6 (SOR: C).

Finally, the patient will need meticulous wound care with adequate pain control; special attention to prevention of secondary infection is essential1,6 (SOR: C).

Our patient was one of the lucky ones

We treated this patient’s hypercalcemia, which was noted on admission to the hospital, with zoledronate and corrected her hypophosphatemia. Her renal function significantly improved with aggressive hydration.

With correction of electrolytes and normalization of kidney function, lesion progression was arrested. Granulation tissue developed in the lesions and split-thickness expanded skin grafts were performed on the large lesions (FIGURE 2). Fortunately, this patient survived despite the usual high rate of mortality. JFP

FIGURE 2

Good granulation beds, followed by closure

After aggressive treatment of renal dysfunction, correction of electrolyte abnormalities, and meticulous wound care, the patient’s lesions developed good granulation beds and showed signs of healing (A). The second image (B), taken 9 months after the patient first sought treatment for the lesions, shows the wounds after skin grafting.

CORRESPONDENCE

E.J. Mayeaux, Jr, MD, DABFP, FAAFP, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, 1501 Kings Highway, Shreveport, LA 71130; [email protected]

A 62-YEAR-OLD WOMAN sought care at our clinic for painful skin lesions that had developed on her thighs 5 days earlier. She had received ongoing treatment at our clinic over the past few years for diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and sarcoidosis. In the last 2 years, she’d had 2 hospitalizations for acute renal failure, with a creatinine value as high as 3.8 mg/dL and a persistent glomerular filtration rate consistent with stage 3 chronic kidney disease.

The medications she was taking included glyburide, pravastatin, and lisinopril. During the 2 years prior to her recent clinic visit, she’d had some intermittently elevated calcium readings. Repeat calcium levels each time were normal. In addition, her parathyroid hormone levels fluctuated between low, high, and normal. Her technetium sestamibi scan was negative for hyperparathyroidism. The patient was unemployed and gave no history of recent travel, injuries, or exposure to animals.

On examination, we noted large, poorly demarcated, warm, indurated erythematous lesions on her lateral thighs. She was given a diagnosis of cellulitis and treated with trimethoprim/sulfa-methoxazole 160/800 mg twice daily for 10 days. During follow-up visits 3 and 7 days later, she indicated that the lesions were less painful and they appeared to be less swollen.

Three weeks later, the patient returned to the clinic with skin sloughing that had produced necrotic lesions with black es-char on the bases (FIGURE 1). In addition, new lesions appeared on her anterior thighs. An initial punch biopsy of the lesions revealed no significant pathologic abnormality.

FIGURE 1

What started as indurated plaques…

The patient initially came in for the treatment of indurated plaques, which developed into ulcerative skin lesions with erythematous edges and eschar on the bases.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Calciphylaxis

Calciphylaxis is an uncommon disorder of vascular calcification and thrombosis resulting in skin necrosis.1 It most commonly occurs in people with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) on hemodialysis, but in nonuremic patients the most frequent cause is primary hyperparathyroidism.2,3 Similar vascular calcifications may be observed in milk alkali syndrome, rickets, collagen diseases, and hypervitaminosis D. Progression to necrosis in these cases is extremely rare.1 There are only a few documented cases of calciphylaxis associated with sarcoidosis, hypercalcemia, and non-ESRD.4

Female sex and diabetes appear to be risk factors.2 The presence of autoimmune disorders is a major feature in patients without ESRD.2,5 Although this patient did not have a previously diagnosed autoimmune disorder, an antinuclear antibody (ANA) test and lupus anticoagulant values were later found to be positive. In patients with autoimmune disorders, prednisone administration is associated with an increased risk of calciphylaxis.5 A hypercoagulable state can also underlie development of calciphylaxis. Our patient did have a mild protein C and S deficiency.

The prognosis of patients diagnosed with calciphylaxis is very poor. The mortality rate is reported to be as high as 60% to 80%.6

4 other possibilities comprise the differential diagnosis

Several conditions may present with erythema or necrosis similar to that of calciphylaxis (TABLE).

Warfarin-induced skin necrosis may produce hemorrhagic bullae and necrotic eschar, but generally presents within 3 to 10 days of initiating warfarin therapy.7 Severe dermatologic manifestations tend to affect the breasts, buttocks, and thighs.

Cutaneous anthrax causes painless necrotic lesions with black eschar, but is linked to bioterrorism or contact with infected animals. Constitutional symptoms such as fever, chills, and malaise are often present. Skin lesions are located primarily on the face, neck, and upper extremities.

Cholesterol embolization results from cholesterol crystals detaching and obstructing smaller arteries. Skin involvement includes livedo reticularis, petechiae, purpura, and ulcerations.

Vasculitis can affect all sizes of blood vessels. It can occur as a complication of connective tissue disorders, viral infections such as hepatitis B and C, or hypersensitivity reactions to medications such as penicillins and cephalosporins. Systemic symptoms are common, as is palpable purpura. Tissue biopsy is important for diagnosis and reveals blood vessel inflammation, not vessel wall calcification.

TABLE

Is it calciphylaxis or something else?1,3,7-9

| Condition | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Warfarin-induced skin necrosis | Painful, erythematous, edematous lesions; rapidly progressive; petechiae, hemorrhagic bullae, then necrotic eschar |

| Cutaneous anthrax | Small painless, pruritic papules; advances to bullae; finally erodes to painless necrotic lesions with black eschar |

| Cholesterol embolization | Majority with livedo reticularis, cyanosis, or gangrene; smaller percentage with cutaneous ulceration, purpura, petechiae, or painful, firm erythematous nodules |

| Vasculitis | Palpable purpura; biopsy of most affected area is necessary for diagnosis |

| Calciphylaxis | Painful erythematous papules, plaques, nodules, or ulcerations in areas with high adiposity; may progress to necrosis |

What to do when the biopsy isn’t helpful

This case points out an important pathologic rule: If the biopsy doesn’t correlate with the observed disease, additional biopsies are indicated. Calciphylaxis is diagnosed on tissue microscopy, but the initial punch biopsy of the lesion revealed no significant pathologic abnormality. However, a subsequent deep-tissue biopsy showed extensive vascular wall calcification and septal fibrosis with subcutaneous fat necrosis.

Repeating abnormal laboratory testing is often appropriate, too. However, in this patient’s case, it probably would not have been helpful because she had intermittently elevated calcium levels over the years.

Wound cultures are often inaccurate in identifying a causative agent and this patient did not appear to have acute infection.

Management is mainly supportive

If you have a patient with calciphylaxis, address predisposing conditions such as hyperparathyroidism, hypercalcemia, and renal dysfunction5 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C). In addition, discontinue calcium and vitamin D supplementation6 (SOR: C).

Finally, the patient will need meticulous wound care with adequate pain control; special attention to prevention of secondary infection is essential1,6 (SOR: C).

Our patient was one of the lucky ones

We treated this patient’s hypercalcemia, which was noted on admission to the hospital, with zoledronate and corrected her hypophosphatemia. Her renal function significantly improved with aggressive hydration.

With correction of electrolytes and normalization of kidney function, lesion progression was arrested. Granulation tissue developed in the lesions and split-thickness expanded skin grafts were performed on the large lesions (FIGURE 2). Fortunately, this patient survived despite the usual high rate of mortality. JFP

FIGURE 2

Good granulation beds, followed by closure

After aggressive treatment of renal dysfunction, correction of electrolyte abnormalities, and meticulous wound care, the patient’s lesions developed good granulation beds and showed signs of healing (A). The second image (B), taken 9 months after the patient first sought treatment for the lesions, shows the wounds after skin grafting.

CORRESPONDENCE

E.J. Mayeaux, Jr, MD, DABFP, FAAFP, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, 1501 Kings Highway, Shreveport, LA 71130; [email protected]

1. Kent RB 3rd, Lylerly RT. Systemic calciphylaxis. South Med J. 1994;87:278-281.

2. Nigwekar SU, Wolf M, Sterns RH, et al. Calciphylaxis from nonuremic causes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1139-1143.

3. Fine A, Zacharias J. Calciphylaxis is usually non-ulcerating. Kidney Int. 2002;61:2210-2217.

4. Swanson AM, Desai SR, Jackson JD, et al. Calciphylaxis associated with chronic inflammatory conditions, immunosuppression therapy, and normal renal function: a report of 2 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:723-725.

5. Weenig RH, Sewell LD, Davis MD, et al. Calciphylaxis: natural history, risk factor analysis, and outcome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:569-579.

6. Al-Hwiesh AK. Calciphylaxis of both proximal and distal distribution. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2008;19:82-86.

7. Renick AM Jr. Anticoagulant-induced necrosis of skin and sub-cutaneous tissues. South Med J. 1976;69:775-778, 804.

8. Wenner KA, Kenner JR. Anthrax. Dermatol Clin. 2004;22:247-256.

9. Falanga V, Fine MJ, Kapoor WN. The cutaneous manifestations of cholesterol crystal embolization. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:1194-1198.

1. Kent RB 3rd, Lylerly RT. Systemic calciphylaxis. South Med J. 1994;87:278-281.

2. Nigwekar SU, Wolf M, Sterns RH, et al. Calciphylaxis from nonuremic causes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1139-1143.

3. Fine A, Zacharias J. Calciphylaxis is usually non-ulcerating. Kidney Int. 2002;61:2210-2217.

4. Swanson AM, Desai SR, Jackson JD, et al. Calciphylaxis associated with chronic inflammatory conditions, immunosuppression therapy, and normal renal function: a report of 2 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:723-725.

5. Weenig RH, Sewell LD, Davis MD, et al. Calciphylaxis: natural history, risk factor analysis, and outcome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:569-579.

6. Al-Hwiesh AK. Calciphylaxis of both proximal and distal distribution. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2008;19:82-86.

7. Renick AM Jr. Anticoagulant-induced necrosis of skin and sub-cutaneous tissues. South Med J. 1976;69:775-778, 804.

8. Wenner KA, Kenner JR. Anthrax. Dermatol Clin. 2004;22:247-256.

9. Falanga V, Fine MJ, Kapoor WN. The cutaneous manifestations of cholesterol crystal embolization. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:1194-1198.

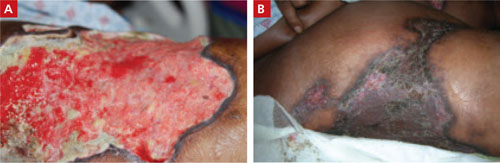

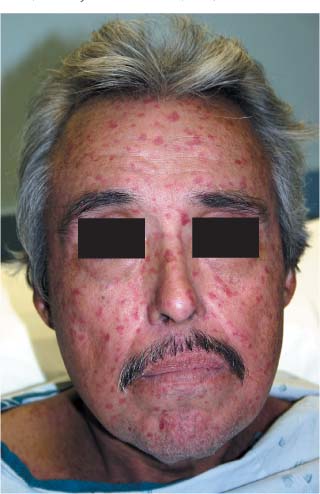

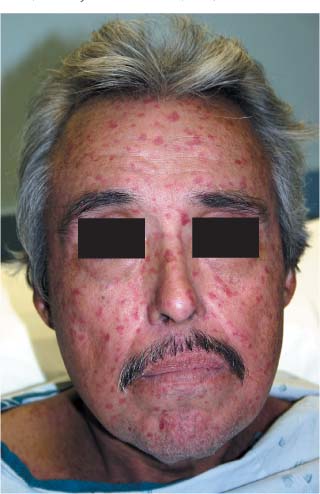

Red spots on face

The patient had several features of the CREST syndrome, which presents with Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, telangiectasias, and calcinosis cutis. His physician suspected that he had systemic sclerosis (scleroderma), a disease characterized by skin induration and thickening accompanied by variable tissue fibrosis and inflammatory infiltration in numerous visceral organs. Systemic sclerosis can be diffuse (DcSSc) or limited to the skin and adjacent tissues (limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis [LcSSc]).

Prominent telangiectasias, like the ones this patient had, can be covered with foundation makeup or treated with laser therapy. Calcium channel blockers, prazosin, prostaglandin derivatives, dipyridamole, aspirin, and topical nitrates may improve symptoms of Raynaud’s phenomenon. Patients should be advised to avoid cold, stress, nicotine, caffeine, and sympathomimetic decongestant medications. Acid reducing agents may be used for GERD.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of Dr. Everett Allen and The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Scleroderma and morphea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al., eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2009:778-783.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The Color Atlas of Family Medicine is also available as an app for mobile devices, see:

The patient had several features of the CREST syndrome, which presents with Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, telangiectasias, and calcinosis cutis. His physician suspected that he had systemic sclerosis (scleroderma), a disease characterized by skin induration and thickening accompanied by variable tissue fibrosis and inflammatory infiltration in numerous visceral organs. Systemic sclerosis can be diffuse (DcSSc) or limited to the skin and adjacent tissues (limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis [LcSSc]).

Prominent telangiectasias, like the ones this patient had, can be covered with foundation makeup or treated with laser therapy. Calcium channel blockers, prazosin, prostaglandin derivatives, dipyridamole, aspirin, and topical nitrates may improve symptoms of Raynaud’s phenomenon. Patients should be advised to avoid cold, stress, nicotine, caffeine, and sympathomimetic decongestant medications. Acid reducing agents may be used for GERD.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of Dr. Everett Allen and The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Scleroderma and morphea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al., eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2009:778-783.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The Color Atlas of Family Medicine is also available as an app for mobile devices, see:

The patient had several features of the CREST syndrome, which presents with Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, telangiectasias, and calcinosis cutis. His physician suspected that he had systemic sclerosis (scleroderma), a disease characterized by skin induration and thickening accompanied by variable tissue fibrosis and inflammatory infiltration in numerous visceral organs. Systemic sclerosis can be diffuse (DcSSc) or limited to the skin and adjacent tissues (limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis [LcSSc]).

Prominent telangiectasias, like the ones this patient had, can be covered with foundation makeup or treated with laser therapy. Calcium channel blockers, prazosin, prostaglandin derivatives, dipyridamole, aspirin, and topical nitrates may improve symptoms of Raynaud’s phenomenon. Patients should be advised to avoid cold, stress, nicotine, caffeine, and sympathomimetic decongestant medications. Acid reducing agents may be used for GERD.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. Photo courtesy of Dr. Everett Allen and The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Scleroderma and morphea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al., eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2009:778-783.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The Color Atlas of Family Medicine is also available as an app for mobile devices, see:

Patches of tough skin

The physician performed a 4-mm punch biopsy that confirmed the clinical suspicion of morphea (localized scleroderma).

Treatment options include high-potency topical glucocorticoids and topical calcipotriol (topical vitamin D). Localized scleroderma appears to soften with ultraviolet-A light therapy. Antihistamines and oral doxepin may be used to treat pruritus.

In this case, the patient was treated with topical clobetasol; she experienced some improvement in skin quality and symptoms. An antinuclear antibody test was positive, but she had not developed progressive systemic sclerosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Scleroderma and morphea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2009:778-783.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The Color Atlas of Family Medicine is also available as an app for mobile devices, see:

The physician performed a 4-mm punch biopsy that confirmed the clinical suspicion of morphea (localized scleroderma).

Treatment options include high-potency topical glucocorticoids and topical calcipotriol (topical vitamin D). Localized scleroderma appears to soften with ultraviolet-A light therapy. Antihistamines and oral doxepin may be used to treat pruritus.

In this case, the patient was treated with topical clobetasol; she experienced some improvement in skin quality and symptoms. An antinuclear antibody test was positive, but she had not developed progressive systemic sclerosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Scleroderma and morphea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2009:778-783.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The Color Atlas of Family Medicine is also available as an app for mobile devices, see:

The physician performed a 4-mm punch biopsy that confirmed the clinical suspicion of morphea (localized scleroderma).

Treatment options include high-potency topical glucocorticoids and topical calcipotriol (topical vitamin D). Localized scleroderma appears to soften with ultraviolet-A light therapy. Antihistamines and oral doxepin may be used to treat pruritus.

In this case, the patient was treated with topical clobetasol; she experienced some improvement in skin quality and symptoms. An antinuclear antibody test was positive, but she had not developed progressive systemic sclerosis.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ. Scleroderma and morphea. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2009:778-783.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The Color Atlas of Family Medicine is also available as an app for mobile devices, see:

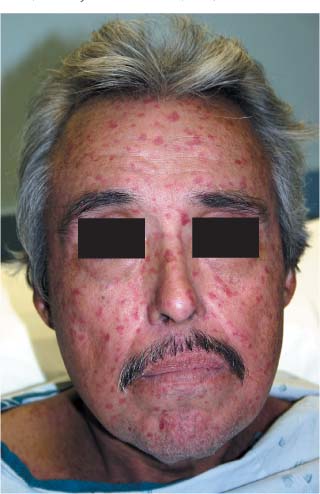

Rash on face

|

|

The patient was given a diagnosis of dermatomyositis, even though muscle weakness was barely present. FIGURE 1 shows a classic heliotrope rash around the patient’s eyes, which was bilaterally symmetrical. The facial rash was getting worse on her days off because she was spending more time in the sun and the rash of dermatomyositis is often worsened by sun exposure. Hand involvement consisted of Gottron’s papules over the finger joints and ragged cuticles (Samitz sign) (FIGURE 2). The patient had normal muscle enzymes. Her diagnosis could almost be called amyopathic dermatomyositis, which is dermatomyositis without muscle involvement.

The physician started the patient on prednisone 60 mg daily and after 2 weeks the rash was almost completely resolved. The patient was also counseled to avoid the sun when possible, and to use sun protection when outside.

The patient was started on 400 mg hydroxychloroquine daily and in 2 months, the prednisone was completely tapered off.

The physician sent the patient to ophthalmology to have a baseline retinal exam at the time the hydroxychloroquine was started. At 6 months, her eye exam remained normal despite the risk of eye problems from the hydroxychloroquine. A year later, the patient had stopped the hydroxychloroquine and was doing well off the medication. Two years later the patient had a relapse and was treated successfully using the same regimen.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Allred A, Usatine R. Dermatomyositis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:772-777.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The Color Atlas of Family Medicine is also available as an app for mobile devices, see:

|

|

The patient was given a diagnosis of dermatomyositis, even though muscle weakness was barely present. FIGURE 1 shows a classic heliotrope rash around the patient’s eyes, which was bilaterally symmetrical. The facial rash was getting worse on her days off because she was spending more time in the sun and the rash of dermatomyositis is often worsened by sun exposure. Hand involvement consisted of Gottron’s papules over the finger joints and ragged cuticles (Samitz sign) (FIGURE 2). The patient had normal muscle enzymes. Her diagnosis could almost be called amyopathic dermatomyositis, which is dermatomyositis without muscle involvement.

The physician started the patient on prednisone 60 mg daily and after 2 weeks the rash was almost completely resolved. The patient was also counseled to avoid the sun when possible, and to use sun protection when outside.

The patient was started on 400 mg hydroxychloroquine daily and in 2 months, the prednisone was completely tapered off.

The physician sent the patient to ophthalmology to have a baseline retinal exam at the time the hydroxychloroquine was started. At 6 months, her eye exam remained normal despite the risk of eye problems from the hydroxychloroquine. A year later, the patient had stopped the hydroxychloroquine and was doing well off the medication. Two years later the patient had a relapse and was treated successfully using the same regimen.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Allred A, Usatine R. Dermatomyositis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:772-777.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The Color Atlas of Family Medicine is also available as an app for mobile devices, see:

|

|

The patient was given a diagnosis of dermatomyositis, even though muscle weakness was barely present. FIGURE 1 shows a classic heliotrope rash around the patient’s eyes, which was bilaterally symmetrical. The facial rash was getting worse on her days off because she was spending more time in the sun and the rash of dermatomyositis is often worsened by sun exposure. Hand involvement consisted of Gottron’s papules over the finger joints and ragged cuticles (Samitz sign) (FIGURE 2). The patient had normal muscle enzymes. Her diagnosis could almost be called amyopathic dermatomyositis, which is dermatomyositis without muscle involvement.

The physician started the patient on prednisone 60 mg daily and after 2 weeks the rash was almost completely resolved. The patient was also counseled to avoid the sun when possible, and to use sun protection when outside.

The patient was started on 400 mg hydroxychloroquine daily and in 2 months, the prednisone was completely tapered off.

The physician sent the patient to ophthalmology to have a baseline retinal exam at the time the hydroxychloroquine was started. At 6 months, her eye exam remained normal despite the risk of eye problems from the hydroxychloroquine. A year later, the patient had stopped the hydroxychloroquine and was doing well off the medication. Two years later the patient had a relapse and was treated successfully using the same regimen.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Allred A, Usatine R. Dermatomyositis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:772-777.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The Color Atlas of Family Medicine is also available as an app for mobile devices, see:

Diffuse rash, muscle weakness

|

|

|

This is a classic presentation of dermatomyositis with the typical rash (FIGURE 1) and proximal muscle weakness. Close attention to the rash around her eyes demonstrates the pathognomonic heliotrope rash of dermatomyositis (FIGURE 2). The heliotrope rash is named after a pink-purple flower, but the rash itself can be more pink than purple.

The patient also had Gottron's papules on the fingers, seen best in this case over the proximal interphalangeal joint of the third finger (FIGURE 3). There was periungual erythema and ragged cuticles, and her scalp was red and scaly. Her neurologic exam was consistent with proximal myopathy. She also had some trouble swallowing bread. (Dysphagia is not unusual in dermatomyositis.) Laboratory tests showed mild elevations in muscle enzymes with the aspartate aminotransferase having the greatest elevation. In other cases, the creatine kinase can be very elevated.

The FP started the patient on 60 mg prednisone daily and topical steroids for the affected areas. The patient responded well to prednisone. Two weeks later, the patient was feeling stronger and the rash was fading. After 6 weeks of 60 mg prednisone daily, she was started on 10 mg methotrexate weekly in order to taper her steroids. The patient continued to do well, but the rash and muscle weakness tended to recur when her steroids were being tapered.

The patient was sent for physical therapy and started on calcium supplementation to protect her from steroid-induced osteoporosis. She was also given 1 mg folic acid a day to minimize the adverse effects of methotrexate.

Since dermatomyositis may be precipitated by an underlying malignancy, the physician screened the patient for internal cancers--especially ovarian cancer. Fortunately, the mammogram, Pap smear, colonoscopy, and abdominal and pelvic CT scans were all normal. Six months later she was doing well on 7.5 mg methotrexate weekly, and 20 mg prednisone daily.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Allred A, Usatine R. Dermatomyositis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:772-777.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The Color Atlas of Family Medicine is also available as an app for mobile devices, see:

|

|

|

This is a classic presentation of dermatomyositis with the typical rash (FIGURE 1) and proximal muscle weakness. Close attention to the rash around her eyes demonstrates the pathognomonic heliotrope rash of dermatomyositis (FIGURE 2). The heliotrope rash is named after a pink-purple flower, but the rash itself can be more pink than purple.

The patient also had Gottron's papules on the fingers, seen best in this case over the proximal interphalangeal joint of the third finger (FIGURE 3). There was periungual erythema and ragged cuticles, and her scalp was red and scaly. Her neurologic exam was consistent with proximal myopathy. She also had some trouble swallowing bread. (Dysphagia is not unusual in dermatomyositis.) Laboratory tests showed mild elevations in muscle enzymes with the aspartate aminotransferase having the greatest elevation. In other cases, the creatine kinase can be very elevated.

The FP started the patient on 60 mg prednisone daily and topical steroids for the affected areas. The patient responded well to prednisone. Two weeks later, the patient was feeling stronger and the rash was fading. After 6 weeks of 60 mg prednisone daily, she was started on 10 mg methotrexate weekly in order to taper her steroids. The patient continued to do well, but the rash and muscle weakness tended to recur when her steroids were being tapered.

The patient was sent for physical therapy and started on calcium supplementation to protect her from steroid-induced osteoporosis. She was also given 1 mg folic acid a day to minimize the adverse effects of methotrexate.

Since dermatomyositis may be precipitated by an underlying malignancy, the physician screened the patient for internal cancers--especially ovarian cancer. Fortunately, the mammogram, Pap smear, colonoscopy, and abdominal and pelvic CT scans were all normal. Six months later she was doing well on 7.5 mg methotrexate weekly, and 20 mg prednisone daily.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Allred A, Usatine R. Dermatomyositis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:772-777.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The Color Atlas of Family Medicine is also available as an app for mobile devices, see:

|

|

|

This is a classic presentation of dermatomyositis with the typical rash (FIGURE 1) and proximal muscle weakness. Close attention to the rash around her eyes demonstrates the pathognomonic heliotrope rash of dermatomyositis (FIGURE 2). The heliotrope rash is named after a pink-purple flower, but the rash itself can be more pink than purple.

The patient also had Gottron's papules on the fingers, seen best in this case over the proximal interphalangeal joint of the third finger (FIGURE 3). There was periungual erythema and ragged cuticles, and her scalp was red and scaly. Her neurologic exam was consistent with proximal myopathy. She also had some trouble swallowing bread. (Dysphagia is not unusual in dermatomyositis.) Laboratory tests showed mild elevations in muscle enzymes with the aspartate aminotransferase having the greatest elevation. In other cases, the creatine kinase can be very elevated.

The FP started the patient on 60 mg prednisone daily and topical steroids for the affected areas. The patient responded well to prednisone. Two weeks later, the patient was feeling stronger and the rash was fading. After 6 weeks of 60 mg prednisone daily, she was started on 10 mg methotrexate weekly in order to taper her steroids. The patient continued to do well, but the rash and muscle weakness tended to recur when her steroids were being tapered.

The patient was sent for physical therapy and started on calcium supplementation to protect her from steroid-induced osteoporosis. She was also given 1 mg folic acid a day to minimize the adverse effects of methotrexate.

Since dermatomyositis may be precipitated by an underlying malignancy, the physician screened the patient for internal cancers--especially ovarian cancer. Fortunately, the mammogram, Pap smear, colonoscopy, and abdominal and pelvic CT scans were all normal. Six months later she was doing well on 7.5 mg methotrexate weekly, and 20 mg prednisone daily.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Allred A, Usatine R. Dermatomyositis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:772-777.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The Color Atlas of Family Medicine is also available as an app for mobile devices, see:

Returning traveler with painful penile mass

WORRIED THAT HE MIGHT HAVE CONTRACTED CHLAMYDIA, a 27-year-old man visited our clinic for treatment. About 5 days earlier, he’d begun experiencing pain and a burning feeling when he urinated. Three days earlier, a painful lump near the head of his penis developed; the lump was growing.

The patient, who was otherwise healthy, had recently returned from a trip to Vietnam during which he reported having had sex with one female partner. He said, “I thought I was safe. I used a condom.”

On examination, he had a purulent urethral discharge and there was a fluctuant, yellowish-white, tender swelling on the left side of the frenulum (FIGURE). There were no ulcers. There was, however, a single 2-cm lymph node in the right inguinal area that was mobile, nontender, nonfluctuant, and of normal consistency.

FIGURE

Swelling with purulent discharge

In addition to the fluctuant, yellowish white, tender swelling on the left side of the frenulum, the patient had purulent urethral discharge and a single, 2-cm lymph node in the right inguinal area.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tysonitis

The clinical history was consistent with a diagnosis of gonococcal urethritis complicated by a periurethral gland abscess. The location of the swelling was most consistent with an abscess in the Tyson’s gland (also known as tysonitis). The Tyson’s (or preputial) glands of the penis are sebaceous-type glands on either side of the frenulum at the balanopreputial sulcus.1 In women, an abscess of the periurethral Skene’s gland is an analogous gonorrheal complication.

Case reports of gonorrheal infection of Tyson’s gland have documented infection with and without symptoms of urethritis.2-4 Diagnosis in this case was confirmed by sending the discharge for nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT), which was positive for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and negative for Chlamydia trachomatis.

Other diagnostic possibilities. The differential diagnosis of acute swelling on the penile shaft includes syphilis, chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum, herpes simplex virus, Behçet’s syndrome, a drug reaction, erythema multiforme, Crohn’s disease, lichen planus, amebiasis, scabies, trauma, and cancer.5

How this patient’s attempt at “safe sex” failed

Oropharyngeal gonococcal infection was the route of transmission implicated in this patient’s infection. When specifically asked about his sexual encounter, our patient admitted that while he was diligent about using a condom for intercourse, he did not use a condom when he received oral sex.

The prevalence of pharyngeal involvement is estimated to be 10% to 20% among women and MSM (men who have sex with men) who have genital gonorrheal infection.6 The risk of contracting N gonorrhoeae when receiving oral sex from an infected partner is unknown.

A common disease, a not-so-common complication

Genital infection by N gonorrhoeae remains the second most common notifiable disease in the United States, with 301,174 cases reported in 2009.7 Effective antimicrobial treatment has reduced the occurrence of local complications of gonococcal infection. Nevertheless, complications of gonococcal urethritis like the ones that follow do occur.

Acute epididymitis is the most common complication of urethral gonorrhea. It is characterized by a swollen and inflamed scrotum, localized epididymal pain, fever, and pyuria.8

Penile edema (“bull-headed clap”) is another common complication.8 It may be limited to the meatus or extend to the distal penile shaft and prepuce and may occur in the absence of other inflammatory signs.

Urethral stricture, once thought to be a common complication, is actually relatively rare, occurring in just 0.5% of cases.6 Urethral strictures attributed to gonorrheal urethritis during the pre-antibiotic era may have actually resulted from the caustic treatments administered during that time.

Acute prostatitis with sudden onset of chills, fever, malaise, and warmth and swelling of the prostate can also develop, although it is more commonly caused by gram-negative rods, such as Escherichia coli or Proteus mirabilis.8

Chronic prostatitis, usually caused by recurrent urinary tract infections, has also been documented as a complication of gonorrheal infection.9

Infection of the Cowper’s, or bulbourethral glands, can occur, leading to perineal swelling.10

Periurethral abscess results when an infected Littre’s or Tyson’s gland ruptures and the infection extends into the deeper tissues.11

Seminal vesiculitis has previously been described as an uncommon complication of gonorrheal infection. However, a recent small study showed ultrasonographic evidence of vesiculitis in 46% of patients with urethritis due to gonorrhea or chlamydia.12

Penile sclerosing lymphangitis presents as an acute, firm, cordlike lesion of the coronal sulcus. A quarter of reported cases have been linked to sexually transmitted infections, including gonorrhea.13

NAAT is key to diagnosis

Infection with genitourinary N gonorrhoeae can be detected in various ways, including gram staining of a male urethral specimen, culture, nucleic acid hybridization, and NAAT. NAAT, which we used with our patient, has the advantage of being approved for use with urine specimens from men and women, as well as with endocervical or urethral samples.

Diagnosis of nongenital infection (ie, pharynx, rectum) typically requires culture. Other diagnostic methods are not FDA-approved for use with specimens from nongenital sites and may yield false-positive results due to cross-reactivity with organisms other than N gonorrhoeae.14 Patients tested for gonorrhea should also be tested for other sexually transmitted infections, including chlamydia, syphilis, and human immunodeficiency virus.

Treat patients with ceftriaxone

Treatment for tysonitis is similar to treatment for gonococcal urethritis and centers on the use of appropriate antibiotics.15 Quinolone-resistant N gonorrhoeae is increasingly common; it is estimated that up to 40% of strains in Asia are now quinolone resistant.16 Because of this, the CDC recommends treatment with ceftriaxone and azithromycin.17 As with urethritis, presumptive treatment for chlamydia is warranted. For tysonitis, incision and drainage may also be necessary.18

A good outcome for our patient

This patient was treated with ceftriaxone 250 mg intramuscularly and azithromycin 1 g as a single oral dose. The abscess was incised and drained under local anesthesia, with 2 cc of pus obtained.

Five days after treatment, the patient reported feeling much better. He was told to call the clinic if he didn’t have complete resolution in 2 weeks. He did not report any further problems.

CORRESPONDENCE Andrew Schechtman, MD, San Jose-O’Connor Hospital Family Medicine Residency, 455 O’Connor Drive,#210, San Jose, CA 95128; [email protected]

1. Batistatou A, Panelos J, Zioga A, et al. Ectomic modified sebaceous glands in human penis. Int J Surg Pathol. 2006;14:355-356.

2. Burgess JA. Gonococcal tysonitis without urethritis after prophylactic post-coital urination. Br J Vener Dis. 1971;47:40-41.

3. Bavidge KJ. Letter: gonococcal infection of the penis. Br J Vener Dis. 1976;52:66.-

4. Abdul Gaffoor PM. Gonococcal tysonitis. Postgrad Med J. 1986;62:869-870.

5. Frenkl T, Potts J. Sexually transmitted diseases. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, et al, eds. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 9th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders; 2007:371–385.

6. Nelson AL. Gonorrheal infections. In: Nelson AL, Woodward JA, eds. Sexually Transmitted Diseases: A Practical Guide for Primary Care. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2007:153–182.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2009. Available at: www.cdc.gov/std/stats09/surv2009-Complete.pdf. Accessed March 25, 2011.

8. Marrazzo JM, Handsfield HH, Sparling PF. Neisseria gonorrhoeae. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Churchill Livingstone 2009;2753-2770.

9. Adler MW. ABC of sexually transmitted diseases: complications of common genital infections and infections in other sites. Br Med J. 1983;287:1709-1712.

10. Subramanian S. Gonococcal urethritis with bilateral tysonitis and periurethral abscess. Sex Transm Dis. 1981;8:77-78.

11. Komolafe AJ, Cornford PA, Fordham MV, et al. Periurethral abscess complicating male gonococcal urethritis treated by surgical incision and drainage. Int J STD AIDS. 2002;13:857-858.

12. Furuya R, Takahashi S, Furuya S, et al. Is urethritis accompanied by seminal vesiculitis? Int J Urol. 2009;16:628-631.

13. Rosen T, Hwong H. Sclerosing lymphangitis of the penis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:916-918.

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines 2006. Diseases characterized by urethritis and cervicitis. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/STD/treatment/2006/urethritis-and-cervicitis.htm#uc6. Accessed January 26, 2010.

15. el-Benhawi MO, el-Tonsy MH. Gonococcal urethritis with bilateral tysonitis. Cutis. 1988;41:425-426.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Increases in fluoroquinolone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae—Hawaii and California, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51:1041-1044.

17. Workowski KA, Berman S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

18. Fiumara NJ. Gonococcal tysonitis. Br J Vener Dis. 1977;53:145.

WORRIED THAT HE MIGHT HAVE CONTRACTED CHLAMYDIA, a 27-year-old man visited our clinic for treatment. About 5 days earlier, he’d begun experiencing pain and a burning feeling when he urinated. Three days earlier, a painful lump near the head of his penis developed; the lump was growing.

The patient, who was otherwise healthy, had recently returned from a trip to Vietnam during which he reported having had sex with one female partner. He said, “I thought I was safe. I used a condom.”

On examination, he had a purulent urethral discharge and there was a fluctuant, yellowish-white, tender swelling on the left side of the frenulum (FIGURE). There were no ulcers. There was, however, a single 2-cm lymph node in the right inguinal area that was mobile, nontender, nonfluctuant, and of normal consistency.

FIGURE

Swelling with purulent discharge

In addition to the fluctuant, yellowish white, tender swelling on the left side of the frenulum, the patient had purulent urethral discharge and a single, 2-cm lymph node in the right inguinal area.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tysonitis

The clinical history was consistent with a diagnosis of gonococcal urethritis complicated by a periurethral gland abscess. The location of the swelling was most consistent with an abscess in the Tyson’s gland (also known as tysonitis). The Tyson’s (or preputial) glands of the penis are sebaceous-type glands on either side of the frenulum at the balanopreputial sulcus.1 In women, an abscess of the periurethral Skene’s gland is an analogous gonorrheal complication.

Case reports of gonorrheal infection of Tyson’s gland have documented infection with and without symptoms of urethritis.2-4 Diagnosis in this case was confirmed by sending the discharge for nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT), which was positive for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and negative for Chlamydia trachomatis.

Other diagnostic possibilities. The differential diagnosis of acute swelling on the penile shaft includes syphilis, chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum, herpes simplex virus, Behçet’s syndrome, a drug reaction, erythema multiforme, Crohn’s disease, lichen planus, amebiasis, scabies, trauma, and cancer.5

How this patient’s attempt at “safe sex” failed

Oropharyngeal gonococcal infection was the route of transmission implicated in this patient’s infection. When specifically asked about his sexual encounter, our patient admitted that while he was diligent about using a condom for intercourse, he did not use a condom when he received oral sex.

The prevalence of pharyngeal involvement is estimated to be 10% to 20% among women and MSM (men who have sex with men) who have genital gonorrheal infection.6 The risk of contracting N gonorrhoeae when receiving oral sex from an infected partner is unknown.

A common disease, a not-so-common complication

Genital infection by N gonorrhoeae remains the second most common notifiable disease in the United States, with 301,174 cases reported in 2009.7 Effective antimicrobial treatment has reduced the occurrence of local complications of gonococcal infection. Nevertheless, complications of gonococcal urethritis like the ones that follow do occur.

Acute epididymitis is the most common complication of urethral gonorrhea. It is characterized by a swollen and inflamed scrotum, localized epididymal pain, fever, and pyuria.8

Penile edema (“bull-headed clap”) is another common complication.8 It may be limited to the meatus or extend to the distal penile shaft and prepuce and may occur in the absence of other inflammatory signs.

Urethral stricture, once thought to be a common complication, is actually relatively rare, occurring in just 0.5% of cases.6 Urethral strictures attributed to gonorrheal urethritis during the pre-antibiotic era may have actually resulted from the caustic treatments administered during that time.

Acute prostatitis with sudden onset of chills, fever, malaise, and warmth and swelling of the prostate can also develop, although it is more commonly caused by gram-negative rods, such as Escherichia coli or Proteus mirabilis.8

Chronic prostatitis, usually caused by recurrent urinary tract infections, has also been documented as a complication of gonorrheal infection.9

Infection of the Cowper’s, or bulbourethral glands, can occur, leading to perineal swelling.10

Periurethral abscess results when an infected Littre’s or Tyson’s gland ruptures and the infection extends into the deeper tissues.11

Seminal vesiculitis has previously been described as an uncommon complication of gonorrheal infection. However, a recent small study showed ultrasonographic evidence of vesiculitis in 46% of patients with urethritis due to gonorrhea or chlamydia.12

Penile sclerosing lymphangitis presents as an acute, firm, cordlike lesion of the coronal sulcus. A quarter of reported cases have been linked to sexually transmitted infections, including gonorrhea.13

NAAT is key to diagnosis

Infection with genitourinary N gonorrhoeae can be detected in various ways, including gram staining of a male urethral specimen, culture, nucleic acid hybridization, and NAAT. NAAT, which we used with our patient, has the advantage of being approved for use with urine specimens from men and women, as well as with endocervical or urethral samples.

Diagnosis of nongenital infection (ie, pharynx, rectum) typically requires culture. Other diagnostic methods are not FDA-approved for use with specimens from nongenital sites and may yield false-positive results due to cross-reactivity with organisms other than N gonorrhoeae.14 Patients tested for gonorrhea should also be tested for other sexually transmitted infections, including chlamydia, syphilis, and human immunodeficiency virus.

Treat patients with ceftriaxone

Treatment for tysonitis is similar to treatment for gonococcal urethritis and centers on the use of appropriate antibiotics.15 Quinolone-resistant N gonorrhoeae is increasingly common; it is estimated that up to 40% of strains in Asia are now quinolone resistant.16 Because of this, the CDC recommends treatment with ceftriaxone and azithromycin.17 As with urethritis, presumptive treatment for chlamydia is warranted. For tysonitis, incision and drainage may also be necessary.18

A good outcome for our patient

This patient was treated with ceftriaxone 250 mg intramuscularly and azithromycin 1 g as a single oral dose. The abscess was incised and drained under local anesthesia, with 2 cc of pus obtained.

Five days after treatment, the patient reported feeling much better. He was told to call the clinic if he didn’t have complete resolution in 2 weeks. He did not report any further problems.

CORRESPONDENCE Andrew Schechtman, MD, San Jose-O’Connor Hospital Family Medicine Residency, 455 O’Connor Drive,#210, San Jose, CA 95128; [email protected]

WORRIED THAT HE MIGHT HAVE CONTRACTED CHLAMYDIA, a 27-year-old man visited our clinic for treatment. About 5 days earlier, he’d begun experiencing pain and a burning feeling when he urinated. Three days earlier, a painful lump near the head of his penis developed; the lump was growing.

The patient, who was otherwise healthy, had recently returned from a trip to Vietnam during which he reported having had sex with one female partner. He said, “I thought I was safe. I used a condom.”

On examination, he had a purulent urethral discharge and there was a fluctuant, yellowish-white, tender swelling on the left side of the frenulum (FIGURE). There were no ulcers. There was, however, a single 2-cm lymph node in the right inguinal area that was mobile, nontender, nonfluctuant, and of normal consistency.

FIGURE

Swelling with purulent discharge

In addition to the fluctuant, yellowish white, tender swelling on the left side of the frenulum, the patient had purulent urethral discharge and a single, 2-cm lymph node in the right inguinal area.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tysonitis