User login

Hypopigmentation on face and arms

|

|

The family physician recognized the hypopigmentation and scarring of the pinna as classic and common findings in discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE). To confirm the diagnosis, a punch biopsy was done on an area of hypopigmentation of the arm. The antinuclear antibody (ANA) test was negative. Patients with DLE generally have negative or low ANA titers, and rarely have low titers of anti-Ro antibodies.

DLE lesions are characterized by discrete, erythematous, slightly infiltrated papules or plaques covered by a well-formed adherent scale. As the lesion progresses, the scale often thickens and becomes adherent. Hypopigmentation develops in the central area and hyperpigmentation develops at the active border. Resolution of the active lesion results in atrophy and scarring. When these lesions occur on the scalp, scarring alopecia often results.

DLE therapy includes corticosteroids (topical or intralesional) and oral antimalarials such as hydroxychloroquine. This patient chose to use topical steroids only. Patients who choose hydroxychloroquine will need eye exams by an ophthalmologist every 6 to 12 months to detect any retinal or visual field problems.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Lupus erythematosus (systemic and cutaneous). In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:766-771.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

|

|

The family physician recognized the hypopigmentation and scarring of the pinna as classic and common findings in discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE). To confirm the diagnosis, a punch biopsy was done on an area of hypopigmentation of the arm. The antinuclear antibody (ANA) test was negative. Patients with DLE generally have negative or low ANA titers, and rarely have low titers of anti-Ro antibodies.

DLE lesions are characterized by discrete, erythematous, slightly infiltrated papules or plaques covered by a well-formed adherent scale. As the lesion progresses, the scale often thickens and becomes adherent. Hypopigmentation develops in the central area and hyperpigmentation develops at the active border. Resolution of the active lesion results in atrophy and scarring. When these lesions occur on the scalp, scarring alopecia often results.

DLE therapy includes corticosteroids (topical or intralesional) and oral antimalarials such as hydroxychloroquine. This patient chose to use topical steroids only. Patients who choose hydroxychloroquine will need eye exams by an ophthalmologist every 6 to 12 months to detect any retinal or visual field problems.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Lupus erythematosus (systemic and cutaneous). In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:766-771.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

|

|

The family physician recognized the hypopigmentation and scarring of the pinna as classic and common findings in discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE). To confirm the diagnosis, a punch biopsy was done on an area of hypopigmentation of the arm. The antinuclear antibody (ANA) test was negative. Patients with DLE generally have negative or low ANA titers, and rarely have low titers of anti-Ro antibodies.

DLE lesions are characterized by discrete, erythematous, slightly infiltrated papules or plaques covered by a well-formed adherent scale. As the lesion progresses, the scale often thickens and becomes adherent. Hypopigmentation develops in the central area and hyperpigmentation develops at the active border. Resolution of the active lesion results in atrophy and scarring. When these lesions occur on the scalp, scarring alopecia often results.

DLE therapy includes corticosteroids (topical or intralesional) and oral antimalarials such as hydroxychloroquine. This patient chose to use topical steroids only. Patients who choose hydroxychloroquine will need eye exams by an ophthalmologist every 6 to 12 months to detect any retinal or visual field problems.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Lupus erythematosus (systemic and cutaneous). In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:766-771.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

Erythematous lesions on baby’s face

The physician diagnosed neonatal lupus erythematosus, a rare syndrome in which maternal autoantibodies are passively transferred to the baby and cause cutaneous lesions or isolated congenital heart block. The skin rash generally appears a few days to weeks after birth, typically after sun exposure, and shows well-demarcated erythematous scaling patches that are often annular and predominately on the scalp, neck, or face. It is self-limited and generally resolves without scarring by 6 to 7 months of age.

Diagnosis is based on physical findings in an infant <6 months of age and detection of autoantibodies against Ro (SSA), La (SSB), and/or U1-ribonucleoprotein (U1-RNP) in the child or mother. All infants diagnosed with neonatal lupus should have an EKG to detect heart block. If the EKG is abnormal, referral to a pediatric cardiologist is warranted.

Infants with neonatal lupus should also be protected from the sun through avoidance and protective clothing. Mild topical steroids may be helpful. Children with neonatal lupus may be at higher risk of developing autoimmune disorders or rheumatic disease later in life.

The infant described here had abnormal anti-Ro, anti-La, and anti-RNP levels. Her mother’s autoantibody levels were similarly abnormal. The infant’s initial nursery stay was complicated by a transient and otherwise asymptomatic bradycardia. An EKG detected a heart rate of 96 bpm with no heart block, but there were changes suggestive of left ventricular hypertrophy. An echocardiogram was normal. The patient was referred to a pediatric cardiologist and a second echocardiogram and EKG were normal.

At 7 weeks, the infant’s cutaneous lesions were present, but were resolving on their own. The skin lesions were fully resolved by 6 months of age.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Lupus erythematosus (systemic and cutaneous). In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:766-771.

Photo courtesy of: Warner AM, Frey KA, Connolly S. Photo Rounds: Annular rash on a newborn. J Fam Pract. 2006;55:128–129.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The physician diagnosed neonatal lupus erythematosus, a rare syndrome in which maternal autoantibodies are passively transferred to the baby and cause cutaneous lesions or isolated congenital heart block. The skin rash generally appears a few days to weeks after birth, typically after sun exposure, and shows well-demarcated erythematous scaling patches that are often annular and predominately on the scalp, neck, or face. It is self-limited and generally resolves without scarring by 6 to 7 months of age.

Diagnosis is based on physical findings in an infant <6 months of age and detection of autoantibodies against Ro (SSA), La (SSB), and/or U1-ribonucleoprotein (U1-RNP) in the child or mother. All infants diagnosed with neonatal lupus should have an EKG to detect heart block. If the EKG is abnormal, referral to a pediatric cardiologist is warranted.

Infants with neonatal lupus should also be protected from the sun through avoidance and protective clothing. Mild topical steroids may be helpful. Children with neonatal lupus may be at higher risk of developing autoimmune disorders or rheumatic disease later in life.

The infant described here had abnormal anti-Ro, anti-La, and anti-RNP levels. Her mother’s autoantibody levels were similarly abnormal. The infant’s initial nursery stay was complicated by a transient and otherwise asymptomatic bradycardia. An EKG detected a heart rate of 96 bpm with no heart block, but there were changes suggestive of left ventricular hypertrophy. An echocardiogram was normal. The patient was referred to a pediatric cardiologist and a second echocardiogram and EKG were normal.

At 7 weeks, the infant’s cutaneous lesions were present, but were resolving on their own. The skin lesions were fully resolved by 6 months of age.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Lupus erythematosus (systemic and cutaneous). In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:766-771.

Photo courtesy of: Warner AM, Frey KA, Connolly S. Photo Rounds: Annular rash on a newborn. J Fam Pract. 2006;55:128–129.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The physician diagnosed neonatal lupus erythematosus, a rare syndrome in which maternal autoantibodies are passively transferred to the baby and cause cutaneous lesions or isolated congenital heart block. The skin rash generally appears a few days to weeks after birth, typically after sun exposure, and shows well-demarcated erythematous scaling patches that are often annular and predominately on the scalp, neck, or face. It is self-limited and generally resolves without scarring by 6 to 7 months of age.

Diagnosis is based on physical findings in an infant <6 months of age and detection of autoantibodies against Ro (SSA), La (SSB), and/or U1-ribonucleoprotein (U1-RNP) in the child or mother. All infants diagnosed with neonatal lupus should have an EKG to detect heart block. If the EKG is abnormal, referral to a pediatric cardiologist is warranted.

Infants with neonatal lupus should also be protected from the sun through avoidance and protective clothing. Mild topical steroids may be helpful. Children with neonatal lupus may be at higher risk of developing autoimmune disorders or rheumatic disease later in life.

The infant described here had abnormal anti-Ro, anti-La, and anti-RNP levels. Her mother’s autoantibody levels were similarly abnormal. The infant’s initial nursery stay was complicated by a transient and otherwise asymptomatic bradycardia. An EKG detected a heart rate of 96 bpm with no heart block, but there were changes suggestive of left ventricular hypertrophy. An echocardiogram was normal. The patient was referred to a pediatric cardiologist and a second echocardiogram and EKG were normal.

At 7 weeks, the infant’s cutaneous lesions were present, but were resolving on their own. The skin lesions were fully resolved by 6 months of age.

Text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Lupus erythematosus (systemic and cutaneous). In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:766-771.

Photo courtesy of: Warner AM, Frey KA, Connolly S. Photo Rounds: Annular rash on a newborn. J Fam Pract. 2006;55:128–129.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

Irregularly shaped abdominal mass

A 46-year-old man sought care at our clinic for an abdominal mass, fatigue, and shortness of breath. He also indicated that he was feeling depressed.

Four years earlier, he’d had a prolonged hospitalization for severe cor pulmonale, during which he suffered a perforated cecum. He had multiple abdominal surgeries, including a right hemicolectomy. His postoperative course was complicated by multi-system organ failure and several nosocomial infections.

In the wake of his recovery, he developed an anterior midline abdominal mass that slowly enlarged over the following years (FIGURE 1). He sought a surgical consultation, but was deferred because of his high-risk operative profile.

Our examination of the patient revealed an anterior, midline, irregularly shaped mass measuring 14 × 20 in. The nontender mass was hollow to percussion and was not as prominent when the patient was supine.

FIGURE 1

Abdominal mass measuring 14 × 20 in

Four years earlier, this 46-year-old patient had undergone multiple abdominal surgeries. On this visit, he sought care for a nontender mass that was hollow to percussion.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Ventral hernia

An abdominal ultrasound revealed subcutaneous, peristalsing bowel loops consistent with a ventral hernia (FIGURE 2). A small amount of ascites was also found.

Most abdominal wall hernias occur in the inguinal region, but in 2003 there were 360,000 ventral hernia repairs performed in the United States.1 Ventral hernias can be further classified as primary or incisional (depending on patient history) and according to their location—midline (epigastric and umbilical) or lateral (Spighelian and lumbar).2

An abdominal hernia typically presents as a nontender, protruding mass that is either stable in size or gradually expands. The mass may be pulsatile, depending on the contents of the hernia and their activity. Hernias may be reducible, meaning that the contents are able to return to the abdominal cavity with external pressure or if the patient is supine. If a hernia is not reducible, then incarceration becomes a significant risk. Compromised blood supply to the incarcerated organ(s) can lead to tissue necrosis and viscous perforation. Epigastric hernias, in particular, carry a high risk of incarceration.3

FIGURE 2

Another view of the ventral hernia

3 conditions comprise the differential

The differential diagnosis includes diastasis recti, ascites, and lipoma.

Diastasis recti is a separation of the rectus abdominus muscles at the linea alba. It is seen almost exclusively in pregnant women and newborns. In this condition, the flat abdominal wall muscles remain intact, and thus abdominal contents would not protrude.

Ascites is the collection of fluid in the abdominal cavity, secondary to conditions such as cirrhosis or congestive heart failure. In ascites, the abdomen is dull to percussion, with no discrete, irregular mass.

Lipoma is a solid benign tumor composed of fatty tissue. A lipoma of this size is rare, and would be solid to percussion. Also, it would not be reducible with the patient supine.

Ultrasound or CT scan is diagnostic

After a thorough history and physical examination, ultrasonography or CT often helps differentiate a ventral hernia from other abdominal wall defects. In patients with a ventral hernia, either imaging modality will demonstrate prolapsed loops of hollow viscus.

A CT scan was not an option for our patient because none of the local machines could accommodate the size and shape of his body. He had an abdominal ultrasound instead.

Surgery sets things right

Treatment of a ventral hernia involves either an open or laparoscopic surgical correction, often with the placement of a supportive mesh4 (SOR: B, inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence). Repair of epigastric hernias is crucial even in asymptomatic patients due to the high rate of incarceration.3

Our patient was referred to a hernia specialty clinic at a nationally recognized medical center. He moved out of state shortly thereafter and was lost to follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

William Murdoch, MD, WSU/Crittenton Family Medicine Residency, 1135 West University Drive, Suite #250, Rochester Hills, MI 48307; [email protected]

1. Park AE, et al. Abdominal wall hernia. Curr Probl Surg. 2006;43:326-375.

2. Muysoms FE, et al. Classification of primary and incisional abdominal wall hernias. Hernia. 2009;13:407-414.

3. Salameh JR. Primary and unusual abdominal wall hernias. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:45-60.

4. Bencini L, et al. Comparison of laparoscopic and open repair for primary ventral hernias. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2009;19:341-344.

A 46-year-old man sought care at our clinic for an abdominal mass, fatigue, and shortness of breath. He also indicated that he was feeling depressed.

Four years earlier, he’d had a prolonged hospitalization for severe cor pulmonale, during which he suffered a perforated cecum. He had multiple abdominal surgeries, including a right hemicolectomy. His postoperative course was complicated by multi-system organ failure and several nosocomial infections.

In the wake of his recovery, he developed an anterior midline abdominal mass that slowly enlarged over the following years (FIGURE 1). He sought a surgical consultation, but was deferred because of his high-risk operative profile.

Our examination of the patient revealed an anterior, midline, irregularly shaped mass measuring 14 × 20 in. The nontender mass was hollow to percussion and was not as prominent when the patient was supine.

FIGURE 1

Abdominal mass measuring 14 × 20 in

Four years earlier, this 46-year-old patient had undergone multiple abdominal surgeries. On this visit, he sought care for a nontender mass that was hollow to percussion.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Ventral hernia

An abdominal ultrasound revealed subcutaneous, peristalsing bowel loops consistent with a ventral hernia (FIGURE 2). A small amount of ascites was also found.

Most abdominal wall hernias occur in the inguinal region, but in 2003 there were 360,000 ventral hernia repairs performed in the United States.1 Ventral hernias can be further classified as primary or incisional (depending on patient history) and according to their location—midline (epigastric and umbilical) or lateral (Spighelian and lumbar).2

An abdominal hernia typically presents as a nontender, protruding mass that is either stable in size or gradually expands. The mass may be pulsatile, depending on the contents of the hernia and their activity. Hernias may be reducible, meaning that the contents are able to return to the abdominal cavity with external pressure or if the patient is supine. If a hernia is not reducible, then incarceration becomes a significant risk. Compromised blood supply to the incarcerated organ(s) can lead to tissue necrosis and viscous perforation. Epigastric hernias, in particular, carry a high risk of incarceration.3

FIGURE 2

Another view of the ventral hernia

3 conditions comprise the differential

The differential diagnosis includes diastasis recti, ascites, and lipoma.

Diastasis recti is a separation of the rectus abdominus muscles at the linea alba. It is seen almost exclusively in pregnant women and newborns. In this condition, the flat abdominal wall muscles remain intact, and thus abdominal contents would not protrude.

Ascites is the collection of fluid in the abdominal cavity, secondary to conditions such as cirrhosis or congestive heart failure. In ascites, the abdomen is dull to percussion, with no discrete, irregular mass.

Lipoma is a solid benign tumor composed of fatty tissue. A lipoma of this size is rare, and would be solid to percussion. Also, it would not be reducible with the patient supine.

Ultrasound or CT scan is diagnostic

After a thorough history and physical examination, ultrasonography or CT often helps differentiate a ventral hernia from other abdominal wall defects. In patients with a ventral hernia, either imaging modality will demonstrate prolapsed loops of hollow viscus.

A CT scan was not an option for our patient because none of the local machines could accommodate the size and shape of his body. He had an abdominal ultrasound instead.

Surgery sets things right

Treatment of a ventral hernia involves either an open or laparoscopic surgical correction, often with the placement of a supportive mesh4 (SOR: B, inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence). Repair of epigastric hernias is crucial even in asymptomatic patients due to the high rate of incarceration.3

Our patient was referred to a hernia specialty clinic at a nationally recognized medical center. He moved out of state shortly thereafter and was lost to follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

William Murdoch, MD, WSU/Crittenton Family Medicine Residency, 1135 West University Drive, Suite #250, Rochester Hills, MI 48307; [email protected]

A 46-year-old man sought care at our clinic for an abdominal mass, fatigue, and shortness of breath. He also indicated that he was feeling depressed.

Four years earlier, he’d had a prolonged hospitalization for severe cor pulmonale, during which he suffered a perforated cecum. He had multiple abdominal surgeries, including a right hemicolectomy. His postoperative course was complicated by multi-system organ failure and several nosocomial infections.

In the wake of his recovery, he developed an anterior midline abdominal mass that slowly enlarged over the following years (FIGURE 1). He sought a surgical consultation, but was deferred because of his high-risk operative profile.

Our examination of the patient revealed an anterior, midline, irregularly shaped mass measuring 14 × 20 in. The nontender mass was hollow to percussion and was not as prominent when the patient was supine.

FIGURE 1

Abdominal mass measuring 14 × 20 in

Four years earlier, this 46-year-old patient had undergone multiple abdominal surgeries. On this visit, he sought care for a nontender mass that was hollow to percussion.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Ventral hernia

An abdominal ultrasound revealed subcutaneous, peristalsing bowel loops consistent with a ventral hernia (FIGURE 2). A small amount of ascites was also found.

Most abdominal wall hernias occur in the inguinal region, but in 2003 there were 360,000 ventral hernia repairs performed in the United States.1 Ventral hernias can be further classified as primary or incisional (depending on patient history) and according to their location—midline (epigastric and umbilical) or lateral (Spighelian and lumbar).2

An abdominal hernia typically presents as a nontender, protruding mass that is either stable in size or gradually expands. The mass may be pulsatile, depending on the contents of the hernia and their activity. Hernias may be reducible, meaning that the contents are able to return to the abdominal cavity with external pressure or if the patient is supine. If a hernia is not reducible, then incarceration becomes a significant risk. Compromised blood supply to the incarcerated organ(s) can lead to tissue necrosis and viscous perforation. Epigastric hernias, in particular, carry a high risk of incarceration.3

FIGURE 2

Another view of the ventral hernia

3 conditions comprise the differential

The differential diagnosis includes diastasis recti, ascites, and lipoma.

Diastasis recti is a separation of the rectus abdominus muscles at the linea alba. It is seen almost exclusively in pregnant women and newborns. In this condition, the flat abdominal wall muscles remain intact, and thus abdominal contents would not protrude.

Ascites is the collection of fluid in the abdominal cavity, secondary to conditions such as cirrhosis or congestive heart failure. In ascites, the abdomen is dull to percussion, with no discrete, irregular mass.

Lipoma is a solid benign tumor composed of fatty tissue. A lipoma of this size is rare, and would be solid to percussion. Also, it would not be reducible with the patient supine.

Ultrasound or CT scan is diagnostic

After a thorough history and physical examination, ultrasonography or CT often helps differentiate a ventral hernia from other abdominal wall defects. In patients with a ventral hernia, either imaging modality will demonstrate prolapsed loops of hollow viscus.

A CT scan was not an option for our patient because none of the local machines could accommodate the size and shape of his body. He had an abdominal ultrasound instead.

Surgery sets things right

Treatment of a ventral hernia involves either an open or laparoscopic surgical correction, often with the placement of a supportive mesh4 (SOR: B, inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence). Repair of epigastric hernias is crucial even in asymptomatic patients due to the high rate of incarceration.3

Our patient was referred to a hernia specialty clinic at a nationally recognized medical center. He moved out of state shortly thereafter and was lost to follow-up.

CORRESPONDENCE

William Murdoch, MD, WSU/Crittenton Family Medicine Residency, 1135 West University Drive, Suite #250, Rochester Hills, MI 48307; [email protected]

1. Park AE, et al. Abdominal wall hernia. Curr Probl Surg. 2006;43:326-375.

2. Muysoms FE, et al. Classification of primary and incisional abdominal wall hernias. Hernia. 2009;13:407-414.

3. Salameh JR. Primary and unusual abdominal wall hernias. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:45-60.

4. Bencini L, et al. Comparison of laparoscopic and open repair for primary ventral hernias. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2009;19:341-344.

1. Park AE, et al. Abdominal wall hernia. Curr Probl Surg. 2006;43:326-375.

2. Muysoms FE, et al. Classification of primary and incisional abdominal wall hernias. Hernia. 2009;13:407-414.

3. Salameh JR. Primary and unusual abdominal wall hernias. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:45-60.

4. Bencini L, et al. Comparison of laparoscopic and open repair for primary ventral hernias. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2009;19:341-344.

Dark spots on face

|

|

The family physician diagnosed chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (discoid lupus).

After noting that the rash was malar and spared the nasolabial folds, the physician ordered an antinuclear antibody (ANA) test and performed a punch biopsy. The ANA was positive at a 1:80 dilution. A homogeneous nuclear pattern was present, as is commonly seen in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and drug-induced lupus. The punch biopsy of a facial lesion was consistent with chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. The comprehensive chemistry panel and complete blood count were normal.

Cutaneous lupus is twice as common in women than men. Patients with cutaneous lupus have a 5% to 10% risk of eventually developing SLE, which tends to follow a mild course. Cutaneous lupus lesions usually slowly expand (with active inflammation at the periphery) and then heal, leaving depressed central scars, atrophy, telangiectasias, and hypopigmentation.

Topical steroids did not provide this patient with relief, so she was started on a short course of systemic steroids. Three weeks later, there was improvement (FIGURE 2). Hyperpigmentation remained, but the erythema, swelling, pain, and pruritus were gone.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Lupus erythematosus (systemic and cutaneous). In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:766-771.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

|

|

The family physician diagnosed chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (discoid lupus).

After noting that the rash was malar and spared the nasolabial folds, the physician ordered an antinuclear antibody (ANA) test and performed a punch biopsy. The ANA was positive at a 1:80 dilution. A homogeneous nuclear pattern was present, as is commonly seen in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and drug-induced lupus. The punch biopsy of a facial lesion was consistent with chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. The comprehensive chemistry panel and complete blood count were normal.

Cutaneous lupus is twice as common in women than men. Patients with cutaneous lupus have a 5% to 10% risk of eventually developing SLE, which tends to follow a mild course. Cutaneous lupus lesions usually slowly expand (with active inflammation at the periphery) and then heal, leaving depressed central scars, atrophy, telangiectasias, and hypopigmentation.

Topical steroids did not provide this patient with relief, so she was started on a short course of systemic steroids. Three weeks later, there was improvement (FIGURE 2). Hyperpigmentation remained, but the erythema, swelling, pain, and pruritus were gone.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Lupus erythematosus (systemic and cutaneous). In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:766-771.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

|

|

The family physician diagnosed chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (discoid lupus).

After noting that the rash was malar and spared the nasolabial folds, the physician ordered an antinuclear antibody (ANA) test and performed a punch biopsy. The ANA was positive at a 1:80 dilution. A homogeneous nuclear pattern was present, as is commonly seen in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and drug-induced lupus. The punch biopsy of a facial lesion was consistent with chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. The comprehensive chemistry panel and complete blood count were normal.

Cutaneous lupus is twice as common in women than men. Patients with cutaneous lupus have a 5% to 10% risk of eventually developing SLE, which tends to follow a mild course. Cutaneous lupus lesions usually slowly expand (with active inflammation at the periphery) and then heal, leaving depressed central scars, atrophy, telangiectasias, and hypopigmentation.

Topical steroids did not provide this patient with relief, so she was started on a short course of systemic steroids. Three weeks later, there was improvement (FIGURE 2). Hyperpigmentation remained, but the erythema, swelling, pain, and pruritus were gone.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux, EJ. Lupus erythematosus (systemic and cutaneous). In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:766-771.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

Discoloration of lower legs

The family physician diagnosed Schamberg’s disease based on the hemosiderin deposits and a cayenne pepper appearance. Schamberg’s disease is a capillaritis characterized by extravasation of erythrocytes in the skin with marked hemosiderin deposition.

There is no known effective treatment for Schamberg's disease. Topical corticosteroids have been tried, but with little success. Patients can be reassured that the condition is harmless and is only a cosmetic concern. The patient was reassured by this information and did not want to try topical steroids.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Cutaneous vasculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al., eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:760-765.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The family physician diagnosed Schamberg’s disease based on the hemosiderin deposits and a cayenne pepper appearance. Schamberg’s disease is a capillaritis characterized by extravasation of erythrocytes in the skin with marked hemosiderin deposition.

There is no known effective treatment for Schamberg's disease. Topical corticosteroids have been tried, but with little success. Patients can be reassured that the condition is harmless and is only a cosmetic concern. The patient was reassured by this information and did not want to try topical steroids.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Cutaneous vasculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al., eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:760-765.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The family physician diagnosed Schamberg’s disease based on the hemosiderin deposits and a cayenne pepper appearance. Schamberg’s disease is a capillaritis characterized by extravasation of erythrocytes in the skin with marked hemosiderin deposition.

There is no known effective treatment for Schamberg's disease. Topical corticosteroids have been tried, but with little success. Patients can be reassured that the condition is harmless and is only a cosmetic concern. The patient was reassured by this information and did not want to try topical steroids.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Cutaneous vasculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al., eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:760-765.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

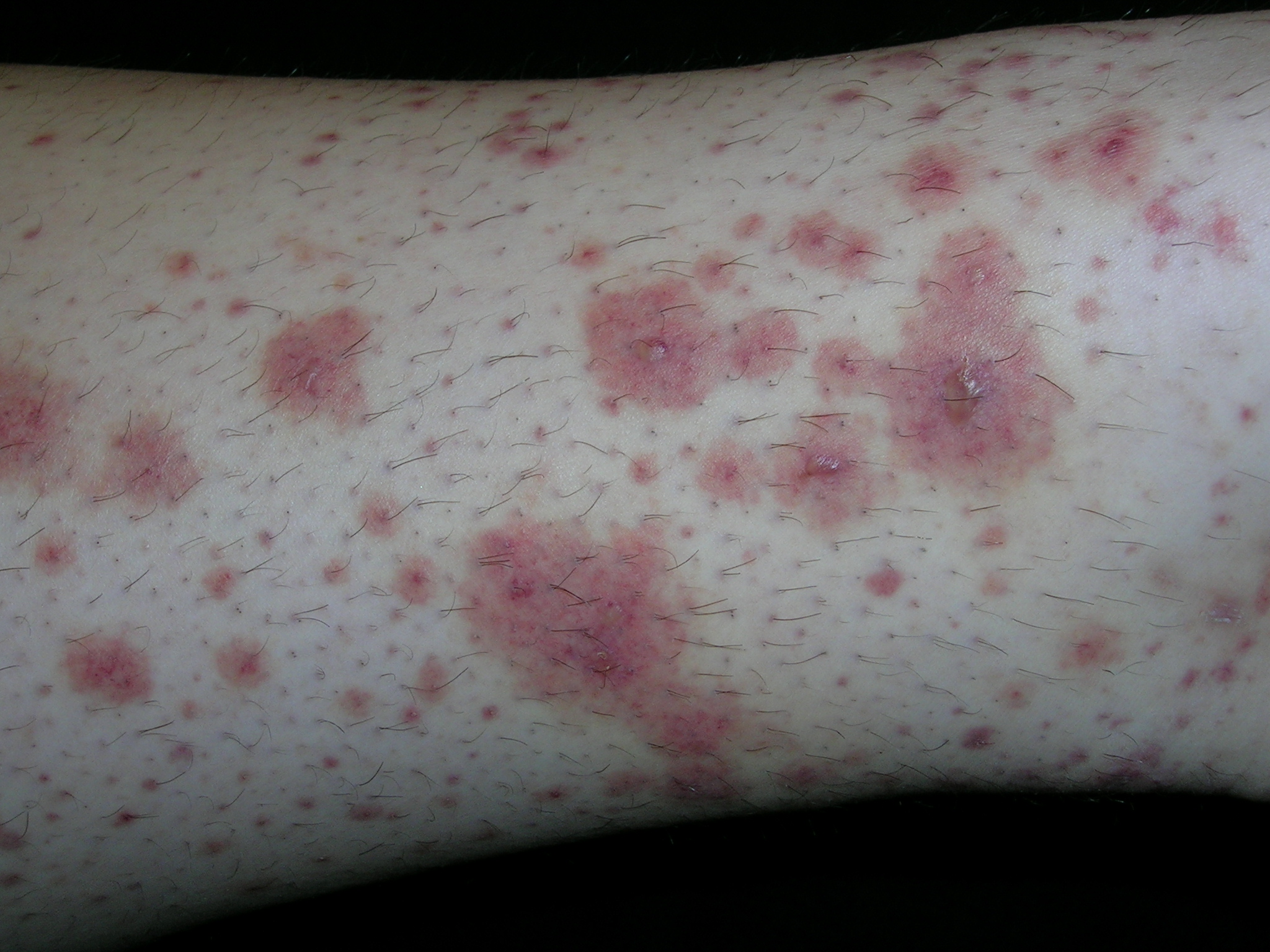

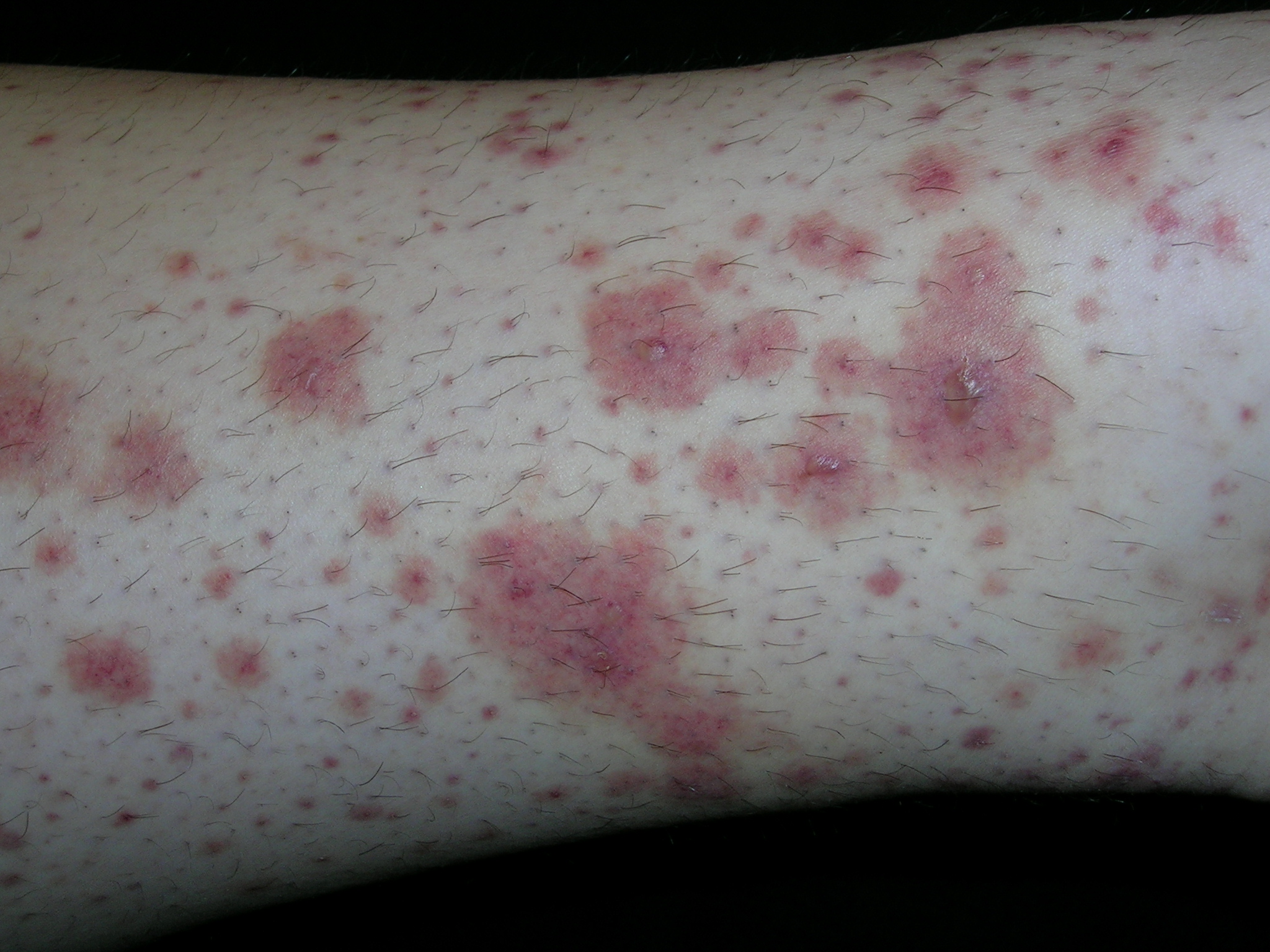

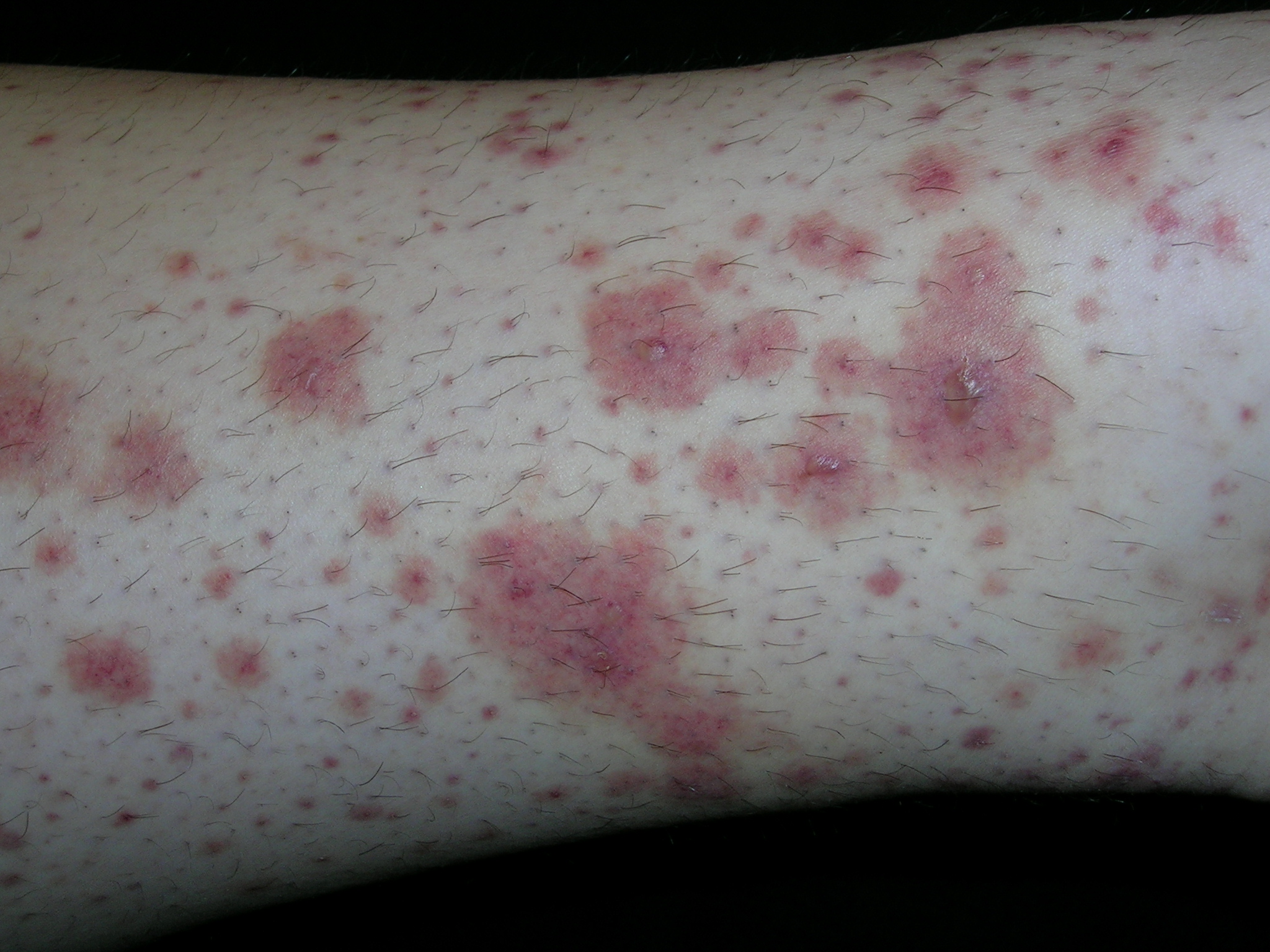

Rash on extremities

The typical palpable purpura on the legs is consistent with Henoch–Schönlein purpura. HSP occurs mainly in children and results from IgA-containing immune complexes in blood vessel walls in the skin, kidney, and gastrointestinal tract. HSP is usually benign and self-limiting. A streptococcal or viral upper respiratory infection often precedes the disease by 1 to 3 weeks. Prodromal symptoms include anorexia and fever. In half of the cases, there are recurrences, typically in the first 3 months. Recurrences are more common in patients with nephritis and are milder than the original episode.

The clinical features of HSP include nonthrombocytopenic palpable purpura mainly on the lower extremities and buttocks, gastrointestinal symptoms, arthralgia, and nephritis. Visceral involvement (with, say, the kidneys and lungs) most commonly occurs in vasculitis associated with HSP, cryoglobulinemia, or systemic lupus erythematosus.

In HSP, treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is usually preferred. Treatment with corticosteroids may be of more benefit in patients with more severe disease such as more pronounced abdominal pain and renal involvement. Oral prednisone is used to treat visceral involvement and more severe cases of vasculitis of the skin. Short courses of prednisone (60–80 mg/d) are effective and should be tapered slowly.

This patient had some hematuria but her creatinine was normal. She was started on ibuprofen with some relief of her skin pain. By the following week, her hematuria was resolved but her skin was not improving. The risks and benefits of prednisone were discussed and the patient decided to take the prednisone. Even on the steroids, the painful rash took 3 to 4 weeks to resolve. Ultimately, it did resolve with no scarring and no sequelae.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Cutaneous vasculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al., eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:760-765.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The typical palpable purpura on the legs is consistent with Henoch–Schönlein purpura. HSP occurs mainly in children and results from IgA-containing immune complexes in blood vessel walls in the skin, kidney, and gastrointestinal tract. HSP is usually benign and self-limiting. A streptococcal or viral upper respiratory infection often precedes the disease by 1 to 3 weeks. Prodromal symptoms include anorexia and fever. In half of the cases, there are recurrences, typically in the first 3 months. Recurrences are more common in patients with nephritis and are milder than the original episode.

The clinical features of HSP include nonthrombocytopenic palpable purpura mainly on the lower extremities and buttocks, gastrointestinal symptoms, arthralgia, and nephritis. Visceral involvement (with, say, the kidneys and lungs) most commonly occurs in vasculitis associated with HSP, cryoglobulinemia, or systemic lupus erythematosus.

In HSP, treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is usually preferred. Treatment with corticosteroids may be of more benefit in patients with more severe disease such as more pronounced abdominal pain and renal involvement. Oral prednisone is used to treat visceral involvement and more severe cases of vasculitis of the skin. Short courses of prednisone (60–80 mg/d) are effective and should be tapered slowly.

This patient had some hematuria but her creatinine was normal. She was started on ibuprofen with some relief of her skin pain. By the following week, her hematuria was resolved but her skin was not improving. The risks and benefits of prednisone were discussed and the patient decided to take the prednisone. Even on the steroids, the painful rash took 3 to 4 weeks to resolve. Ultimately, it did resolve with no scarring and no sequelae.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Cutaneous vasculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al., eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:760-765.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The typical palpable purpura on the legs is consistent with Henoch–Schönlein purpura. HSP occurs mainly in children and results from IgA-containing immune complexes in blood vessel walls in the skin, kidney, and gastrointestinal tract. HSP is usually benign and self-limiting. A streptococcal or viral upper respiratory infection often precedes the disease by 1 to 3 weeks. Prodromal symptoms include anorexia and fever. In half of the cases, there are recurrences, typically in the first 3 months. Recurrences are more common in patients with nephritis and are milder than the original episode.

The clinical features of HSP include nonthrombocytopenic palpable purpura mainly on the lower extremities and buttocks, gastrointestinal symptoms, arthralgia, and nephritis. Visceral involvement (with, say, the kidneys and lungs) most commonly occurs in vasculitis associated with HSP, cryoglobulinemia, or systemic lupus erythematosus.

In HSP, treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is usually preferred. Treatment with corticosteroids may be of more benefit in patients with more severe disease such as more pronounced abdominal pain and renal involvement. Oral prednisone is used to treat visceral involvement and more severe cases of vasculitis of the skin. Short courses of prednisone (60–80 mg/d) are effective and should be tapered slowly.

This patient had some hematuria but her creatinine was normal. She was started on ibuprofen with some relief of her skin pain. By the following week, her hematuria was resolved but her skin was not improving. The risks and benefits of prednisone were discussed and the patient decided to take the prednisone. Even on the steroids, the painful rash took 3 to 4 weeks to resolve. Ultimately, it did resolve with no scarring and no sequelae.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Mayeaux EJ, Usatine R. Cutaneous vasculitis. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al., eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:760-765.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

Red nodules on knees

The family physician suspected that the patient had erythema nodosum along with some pulmonary disease. She ordered a stat chest x-ray and bilateral hilar adenopathy with diffuse parenchymal infiltrates were seen (suggesting stage II sarcoidosis). The physician ordered an angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) level, erythrocyte sedimentation rate test, complete blood count, and a comprehensive metabolic profile.

When the EN rash occurs with hilar adenopathy, the entity is called Lofgren’s syndrome. Lofgren’s syndrome can occur in tuberculosis, but a more common cause of Lofgren’s syndrome is sarcoidosis (as seen in this patient). Sarcoidosis, in particular, may present with EN lesions on the ankles and knees.

The physician treated the pain and discomfort of the nodules with ibuprofen. Oral prednisone for EN alone is controversial and should be avoided unless it is being used to treat the underlying cause (such as sarcoidosis). A referral was made to pulmonary medicine. It was expected that pulmonary function tests would be performed and prednisone might be initiated if the response to the ibuprofen was not sufficient.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Paulis R. Erythema nodosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al., eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:756-759.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The family physician suspected that the patient had erythema nodosum along with some pulmonary disease. She ordered a stat chest x-ray and bilateral hilar adenopathy with diffuse parenchymal infiltrates were seen (suggesting stage II sarcoidosis). The physician ordered an angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) level, erythrocyte sedimentation rate test, complete blood count, and a comprehensive metabolic profile.

When the EN rash occurs with hilar adenopathy, the entity is called Lofgren’s syndrome. Lofgren’s syndrome can occur in tuberculosis, but a more common cause of Lofgren’s syndrome is sarcoidosis (as seen in this patient). Sarcoidosis, in particular, may present with EN lesions on the ankles and knees.

The physician treated the pain and discomfort of the nodules with ibuprofen. Oral prednisone for EN alone is controversial and should be avoided unless it is being used to treat the underlying cause (such as sarcoidosis). A referral was made to pulmonary medicine. It was expected that pulmonary function tests would be performed and prednisone might be initiated if the response to the ibuprofen was not sufficient.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Paulis R. Erythema nodosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al., eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:756-759.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The family physician suspected that the patient had erythema nodosum along with some pulmonary disease. She ordered a stat chest x-ray and bilateral hilar adenopathy with diffuse parenchymal infiltrates were seen (suggesting stage II sarcoidosis). The physician ordered an angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) level, erythrocyte sedimentation rate test, complete blood count, and a comprehensive metabolic profile.

When the EN rash occurs with hilar adenopathy, the entity is called Lofgren’s syndrome. Lofgren’s syndrome can occur in tuberculosis, but a more common cause of Lofgren’s syndrome is sarcoidosis (as seen in this patient). Sarcoidosis, in particular, may present with EN lesions on the ankles and knees.

The physician treated the pain and discomfort of the nodules with ibuprofen. Oral prednisone for EN alone is controversial and should be avoided unless it is being used to treat the underlying cause (such as sarcoidosis). A referral was made to pulmonary medicine. It was expected that pulmonary function tests would be performed and prednisone might be initiated if the response to the ibuprofen was not sufficient.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Paulis R. Erythema nodosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al., eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:756-759.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

Bumps on legs

The patient’s rapid strep test was positive and she was diagnosed clinically with erythema nodosum (EN) secondary to group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis. EN is the most frequent type of septal panniculitis (inflammation of the septa of fat lobules in the subcutaneous tissue). EN tends to occur more often in women in the adult population, generally during the second and fourth decades of life.

While the exact percentage is unknown, one study estimated that 55% of EN is idiopathic. Identifiable causes can be infectious, reactive, pharmacologic, or neoplastic. Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis has been linked to EN. A retrospective study of 129 cases of EN over several decades revealed that 28% of the patients had streptococcal infection. Nonstreptococcal upper respiratory tract infections may also play a role.

EN lesions are deep-seated nodules that may be more easily palpated than visualized. The lesions are initially firm, round or oval, and are poorly demarcated. As seen in this case, the lesions may be bright red, warm, and painful. The lesions number from 1 to more than 10 and vary in size from 1 to 15 cm. Lesions appear on the anterior/lateral aspect of both lower extremities. A characteristic of EN is the complete resolution of lesions with no ulceration or scarring. EN may occur with fever, malaise, and polyarthralgia.

The diagnosis of EN is mostly made on physical examination. When the diagnosis is uncertain, a biopsy that includes subcutaneous fat is performed. This can be a deep punch biopsy or a deep incisional biopsy sent for standard histology. For suspected strep cases, rapid strep test or throat cultures are best during acute illness, while antistreptolysin O titers may be used in the convalescent phase.

Look for, and treat, the underlying cause. There is limited evidence to guide treatment unless an underlying cause is found. In this case, the patient was treated with penicillin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and was advised to get some bedrest. She experienced complete resolution of the EN within 4 weeks.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Paulis R. Erythema nodosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al., eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:756-759.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The patient’s rapid strep test was positive and she was diagnosed clinically with erythema nodosum (EN) secondary to group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis. EN is the most frequent type of septal panniculitis (inflammation of the septa of fat lobules in the subcutaneous tissue). EN tends to occur more often in women in the adult population, generally during the second and fourth decades of life.

While the exact percentage is unknown, one study estimated that 55% of EN is idiopathic. Identifiable causes can be infectious, reactive, pharmacologic, or neoplastic. Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis has been linked to EN. A retrospective study of 129 cases of EN over several decades revealed that 28% of the patients had streptococcal infection. Nonstreptococcal upper respiratory tract infections may also play a role.

EN lesions are deep-seated nodules that may be more easily palpated than visualized. The lesions are initially firm, round or oval, and are poorly demarcated. As seen in this case, the lesions may be bright red, warm, and painful. The lesions number from 1 to more than 10 and vary in size from 1 to 15 cm. Lesions appear on the anterior/lateral aspect of both lower extremities. A characteristic of EN is the complete resolution of lesions with no ulceration or scarring. EN may occur with fever, malaise, and polyarthralgia.

The diagnosis of EN is mostly made on physical examination. When the diagnosis is uncertain, a biopsy that includes subcutaneous fat is performed. This can be a deep punch biopsy or a deep incisional biopsy sent for standard histology. For suspected strep cases, rapid strep test or throat cultures are best during acute illness, while antistreptolysin O titers may be used in the convalescent phase.

Look for, and treat, the underlying cause. There is limited evidence to guide treatment unless an underlying cause is found. In this case, the patient was treated with penicillin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and was advised to get some bedrest. She experienced complete resolution of the EN within 4 weeks.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Paulis R. Erythema nodosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al., eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:756-759.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The patient’s rapid strep test was positive and she was diagnosed clinically with erythema nodosum (EN) secondary to group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis. EN is the most frequent type of septal panniculitis (inflammation of the septa of fat lobules in the subcutaneous tissue). EN tends to occur more often in women in the adult population, generally during the second and fourth decades of life.

While the exact percentage is unknown, one study estimated that 55% of EN is idiopathic. Identifiable causes can be infectious, reactive, pharmacologic, or neoplastic. Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis has been linked to EN. A retrospective study of 129 cases of EN over several decades revealed that 28% of the patients had streptococcal infection. Nonstreptococcal upper respiratory tract infections may also play a role.

EN lesions are deep-seated nodules that may be more easily palpated than visualized. The lesions are initially firm, round or oval, and are poorly demarcated. As seen in this case, the lesions may be bright red, warm, and painful. The lesions number from 1 to more than 10 and vary in size from 1 to 15 cm. Lesions appear on the anterior/lateral aspect of both lower extremities. A characteristic of EN is the complete resolution of lesions with no ulceration or scarring. EN may occur with fever, malaise, and polyarthralgia.

The diagnosis of EN is mostly made on physical examination. When the diagnosis is uncertain, a biopsy that includes subcutaneous fat is performed. This can be a deep punch biopsy or a deep incisional biopsy sent for standard histology. For suspected strep cases, rapid strep test or throat cultures are best during acute illness, while antistreptolysin O titers may be used in the convalescent phase.

Look for, and treat, the underlying cause. There is limited evidence to guide treatment unless an underlying cause is found. In this case, the patient was treated with penicillin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and was advised to get some bedrest. She experienced complete resolution of the EN within 4 weeks.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Richard P. Usatine, MD. This case was adapted from: Paulis R. Erythema nodosum. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al., eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:756-759.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

Cellulitis unresponsive to antibiotics

A 36-year-old white woman sought care at our outpatient clinic for 2 days of right forearm and hand redness, swelling, and severe pain at a previous intravenous (IV) catheter site. The patient had received intramuscular antibiotics for culture-positive streptococcal pharyngitis 2 weeks earlier, and then IV fluids and steroids due to poor oral intake from odynophagia.

She indicated that since the time of the pharyngitis diagnosis, she’d had a persistent fever. At our clinic, she was given a diagnosis of cellulitis and started on a course of oral cephalexin.

Three days later, she returned. She had a temperature of 100°F and her right forearm and wrist were exquisitely sensitive to touch over a warm and indurated violaceous rash with pseudovesicles over the most edematous portions (FIGURE 1). This rash extended onto her right hand and proximal phalanges. Her fingers hurt when she moved them; sensation and pulses were intact.

Her left wrist was now mildly swollen, with associated warmth and erythema, but no vesicles. Her left ankle was also warm, erythematous, and moderately swollen with significant tenderness to palpation. She had a few scattered nodular, erythematous lesions on her upper right arm and chest.

We (RW and VK) admitted the patient and started her on IV vancomycin and clindamycin to treat presumed refractory cellulitis. On Day 2 she hadn’t improved, so we added gatifloxacin for gram-negative coverage. On Day 3, her lesions worsened, so we transferred her to a higher-level facility.

FIGURE 1

Worsening lesions

The patient’s right forearm and wrist were exquisitely sensitive to touch over the rash, with pseudovesicles. Ink markings denote original boundaries of the lesion.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Sweet’s syndrome

A skin biopsy revealed subepidermal bullae with marked dermal and mixed lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltrate consistent with Sweet’s syndrome.

Sweet’s syndrome, also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatoses, is a condition that was originally described by Dr. Robert Sweet in 1964.1 The condition can be classified based on etiology as "classical" or idiopathic, malignancy-associated, or drug-induced.2 Classical Sweet’s syndrome typically affects women 30 to 50 years of age, but has been reported in men and women of all ages.3-5 More than 500 cases have been reported in the literature, but incidence and prevalence data are limited.6 Conditions associated with classical Sweet’s syndrome include upper respiratory infection, gastrointestinal infection, inflammatory bowel disease, and pregnancy.5

Cellulitis and lupus erythematosus are part of the differential

The differential diagnosis for erythematous, indurated, tender skin and soft tissue lesions includes cellulitis, erysipelas, thrombophlebitis, urticaria, shingles, drug-induced eruptions, and herpes simplex virus infections.4-6

Less common conditions include erythema multiforme, erythema nodusum, tuberculosis, leukemia cutis, lupus erythematosus, vasculitis, pyoderma gangrenosa, Behçet’s disease, erythema elevatum diutinum, familial Mediterranean fever, and Sweet’s syndrome.4-6

Diagnosis hinges on these criteria

Two major criteria are required to make a diagnosis of Sweet’s syndrome. They are:2

- the abrupt onset of tender, erythematous plaques or nodules (FIGURE 2)

- a predominately neutrophilic infiltration in the dermis without leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

At least 2 of 4 minor criteria must also be present:2

- a precedent respiratory or gastrointestinal (GI) infection, vaccination, inflammatory disease, malignancy, or pregnancy

- malaise and fever

- elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and leukocytosis with a left shift. (Our patient’s erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 93 mm/h; her C-reactive protein was 11.47 mg/dL.)

- excellent response to corticosteroids or potassium iodide.

Although skin manifestations are a hallmark sign (which makes Sweet’s syndrome an important differential diagnosis for an unusual case of cellulitis, or one that is unresponsive to antibiotics), many possible coincident manifestations can occur. These include arthralgia, myalgia, headache, and malaise.5 Multi-system involvement has also been reported, affecting bone, the central nervous system, eyes, kidneys, heart, lungs, and GI tract.5

FIGURE 2

Another presentation of Sweet’s syndrome

Some Sweet’s syndrome lesions appear "juicy." This lesion occurred at the site of minor trauma (pathergy) in a patient who was febrile and systemically ill.

Treatment: Corticosteroids, not antibiotics

A high clinical suspicion for Sweet’s syndrome is critical to management decisions because the primary treatment is corticosteroids, rather than antibiotics.5,6 Oral prednisone at 0.5 to 1.5 mg/kg per day with taper over 2 to 6 weeks is a standard regimen.2 IV methylprednisolone of up to 1000 mg per day for 3 to 5 days, followed by a tapered oral dose of corticosteroids over several weeks is another option.5 Other first-line treatment options include colchicine (0.5 mg 3 times a day) and oral potassium iodide (300 mg enteric-coated tablets 3 times a day).5,6 Indomethacin, cyclosporine, surgery, and dapsone are other options/adjuncts.

Recurrences of Sweet’s syndrome may occur, regardless of treatment. They are more likely to occur in patients with an underlying malignancy and may herald recurrence of malignancy in a previously treated patient.5 Treating an underlying malignancy (or discontinuing the causative medication in drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome) may resolve symptoms. IV administration of methylprednisolone, as discussed earlier, has been successful for refractory cases.5

Our patient responded well to treatment

Our patient was started on prednisone 60 mg daily and her antibiotics were discontinued. Within 24 hours, her skin lesions regressed. She was discharged on a tapering course of the prednisone.

After several weeks, her lesions completely cleared without scarring or recurrence.

CORRESPONDENCE

Ryan A. Withrow, DO, 4-2807 Reilly Road, Family Medicine Residency Clinic, Fort Bragg, NC 28314; [email protected]

1. Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-356.

2. Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Mosby/Elsevier; 2010.

3. Kemmett D, Hunter JA. Sweet’s syndrome: a clinicopathologic review of twenty-nine cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:503-507.

4. Boatman BW, Taylor RC, Klein LE, et al. Sweet’s syndrome in children. South Med J. 1994;87:193-196.

5. Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome revisited: a review of disease concepts. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:761-778.

6. Von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-556.

A 36-year-old white woman sought care at our outpatient clinic for 2 days of right forearm and hand redness, swelling, and severe pain at a previous intravenous (IV) catheter site. The patient had received intramuscular antibiotics for culture-positive streptococcal pharyngitis 2 weeks earlier, and then IV fluids and steroids due to poor oral intake from odynophagia.

She indicated that since the time of the pharyngitis diagnosis, she’d had a persistent fever. At our clinic, she was given a diagnosis of cellulitis and started on a course of oral cephalexin.

Three days later, she returned. She had a temperature of 100°F and her right forearm and wrist were exquisitely sensitive to touch over a warm and indurated violaceous rash with pseudovesicles over the most edematous portions (FIGURE 1). This rash extended onto her right hand and proximal phalanges. Her fingers hurt when she moved them; sensation and pulses were intact.

Her left wrist was now mildly swollen, with associated warmth and erythema, but no vesicles. Her left ankle was also warm, erythematous, and moderately swollen with significant tenderness to palpation. She had a few scattered nodular, erythematous lesions on her upper right arm and chest.

We (RW and VK) admitted the patient and started her on IV vancomycin and clindamycin to treat presumed refractory cellulitis. On Day 2 she hadn’t improved, so we added gatifloxacin for gram-negative coverage. On Day 3, her lesions worsened, so we transferred her to a higher-level facility.

FIGURE 1

Worsening lesions

The patient’s right forearm and wrist were exquisitely sensitive to touch over the rash, with pseudovesicles. Ink markings denote original boundaries of the lesion.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Sweet’s syndrome

A skin biopsy revealed subepidermal bullae with marked dermal and mixed lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltrate consistent with Sweet’s syndrome.

Sweet’s syndrome, also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatoses, is a condition that was originally described by Dr. Robert Sweet in 1964.1 The condition can be classified based on etiology as "classical" or idiopathic, malignancy-associated, or drug-induced.2 Classical Sweet’s syndrome typically affects women 30 to 50 years of age, but has been reported in men and women of all ages.3-5 More than 500 cases have been reported in the literature, but incidence and prevalence data are limited.6 Conditions associated with classical Sweet’s syndrome include upper respiratory infection, gastrointestinal infection, inflammatory bowel disease, and pregnancy.5

Cellulitis and lupus erythematosus are part of the differential

The differential diagnosis for erythematous, indurated, tender skin and soft tissue lesions includes cellulitis, erysipelas, thrombophlebitis, urticaria, shingles, drug-induced eruptions, and herpes simplex virus infections.4-6

Less common conditions include erythema multiforme, erythema nodusum, tuberculosis, leukemia cutis, lupus erythematosus, vasculitis, pyoderma gangrenosa, Behçet’s disease, erythema elevatum diutinum, familial Mediterranean fever, and Sweet’s syndrome.4-6

Diagnosis hinges on these criteria

Two major criteria are required to make a diagnosis of Sweet’s syndrome. They are:2

- the abrupt onset of tender, erythematous plaques or nodules (FIGURE 2)

- a predominately neutrophilic infiltration in the dermis without leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

At least 2 of 4 minor criteria must also be present:2

- a precedent respiratory or gastrointestinal (GI) infection, vaccination, inflammatory disease, malignancy, or pregnancy

- malaise and fever

- elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and leukocytosis with a left shift. (Our patient’s erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 93 mm/h; her C-reactive protein was 11.47 mg/dL.)

- excellent response to corticosteroids or potassium iodide.

Although skin manifestations are a hallmark sign (which makes Sweet’s syndrome an important differential diagnosis for an unusual case of cellulitis, or one that is unresponsive to antibiotics), many possible coincident manifestations can occur. These include arthralgia, myalgia, headache, and malaise.5 Multi-system involvement has also been reported, affecting bone, the central nervous system, eyes, kidneys, heart, lungs, and GI tract.5

FIGURE 2

Another presentation of Sweet’s syndrome

Some Sweet’s syndrome lesions appear "juicy." This lesion occurred at the site of minor trauma (pathergy) in a patient who was febrile and systemically ill.

Treatment: Corticosteroids, not antibiotics

A high clinical suspicion for Sweet’s syndrome is critical to management decisions because the primary treatment is corticosteroids, rather than antibiotics.5,6 Oral prednisone at 0.5 to 1.5 mg/kg per day with taper over 2 to 6 weeks is a standard regimen.2 IV methylprednisolone of up to 1000 mg per day for 3 to 5 days, followed by a tapered oral dose of corticosteroids over several weeks is another option.5 Other first-line treatment options include colchicine (0.5 mg 3 times a day) and oral potassium iodide (300 mg enteric-coated tablets 3 times a day).5,6 Indomethacin, cyclosporine, surgery, and dapsone are other options/adjuncts.

Recurrences of Sweet’s syndrome may occur, regardless of treatment. They are more likely to occur in patients with an underlying malignancy and may herald recurrence of malignancy in a previously treated patient.5 Treating an underlying malignancy (or discontinuing the causative medication in drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome) may resolve symptoms. IV administration of methylprednisolone, as discussed earlier, has been successful for refractory cases.5

Our patient responded well to treatment

Our patient was started on prednisone 60 mg daily and her antibiotics were discontinued. Within 24 hours, her skin lesions regressed. She was discharged on a tapering course of the prednisone.

After several weeks, her lesions completely cleared without scarring or recurrence.

CORRESPONDENCE

Ryan A. Withrow, DO, 4-2807 Reilly Road, Family Medicine Residency Clinic, Fort Bragg, NC 28314; [email protected]

A 36-year-old white woman sought care at our outpatient clinic for 2 days of right forearm and hand redness, swelling, and severe pain at a previous intravenous (IV) catheter site. The patient had received intramuscular antibiotics for culture-positive streptococcal pharyngitis 2 weeks earlier, and then IV fluids and steroids due to poor oral intake from odynophagia.

She indicated that since the time of the pharyngitis diagnosis, she’d had a persistent fever. At our clinic, she was given a diagnosis of cellulitis and started on a course of oral cephalexin.

Three days later, she returned. She had a temperature of 100°F and her right forearm and wrist were exquisitely sensitive to touch over a warm and indurated violaceous rash with pseudovesicles over the most edematous portions (FIGURE 1). This rash extended onto her right hand and proximal phalanges. Her fingers hurt when she moved them; sensation and pulses were intact.

Her left wrist was now mildly swollen, with associated warmth and erythema, but no vesicles. Her left ankle was also warm, erythematous, and moderately swollen with significant tenderness to palpation. She had a few scattered nodular, erythematous lesions on her upper right arm and chest.

We (RW and VK) admitted the patient and started her on IV vancomycin and clindamycin to treat presumed refractory cellulitis. On Day 2 she hadn’t improved, so we added gatifloxacin for gram-negative coverage. On Day 3, her lesions worsened, so we transferred her to a higher-level facility.

FIGURE 1

Worsening lesions

The patient’s right forearm and wrist were exquisitely sensitive to touch over the rash, with pseudovesicles. Ink markings denote original boundaries of the lesion.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Sweet’s syndrome

A skin biopsy revealed subepidermal bullae with marked dermal and mixed lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltrate consistent with Sweet’s syndrome.

Sweet’s syndrome, also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatoses, is a condition that was originally described by Dr. Robert Sweet in 1964.1 The condition can be classified based on etiology as "classical" or idiopathic, malignancy-associated, or drug-induced.2 Classical Sweet’s syndrome typically affects women 30 to 50 years of age, but has been reported in men and women of all ages.3-5 More than 500 cases have been reported in the literature, but incidence and prevalence data are limited.6 Conditions associated with classical Sweet’s syndrome include upper respiratory infection, gastrointestinal infection, inflammatory bowel disease, and pregnancy.5

Cellulitis and lupus erythematosus are part of the differential

The differential diagnosis for erythematous, indurated, tender skin and soft tissue lesions includes cellulitis, erysipelas, thrombophlebitis, urticaria, shingles, drug-induced eruptions, and herpes simplex virus infections.4-6

Less common conditions include erythema multiforme, erythema nodusum, tuberculosis, leukemia cutis, lupus erythematosus, vasculitis, pyoderma gangrenosa, Behçet’s disease, erythema elevatum diutinum, familial Mediterranean fever, and Sweet’s syndrome.4-6

Diagnosis hinges on these criteria

Two major criteria are required to make a diagnosis of Sweet’s syndrome. They are:2

- the abrupt onset of tender, erythematous plaques or nodules (FIGURE 2)

- a predominately neutrophilic infiltration in the dermis without leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

At least 2 of 4 minor criteria must also be present:2

- a precedent respiratory or gastrointestinal (GI) infection, vaccination, inflammatory disease, malignancy, or pregnancy

- malaise and fever

- elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and leukocytosis with a left shift. (Our patient’s erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 93 mm/h; her C-reactive protein was 11.47 mg/dL.)

- excellent response to corticosteroids or potassium iodide.

Although skin manifestations are a hallmark sign (which makes Sweet’s syndrome an important differential diagnosis for an unusual case of cellulitis, or one that is unresponsive to antibiotics), many possible coincident manifestations can occur. These include arthralgia, myalgia, headache, and malaise.5 Multi-system involvement has also been reported, affecting bone, the central nervous system, eyes, kidneys, heart, lungs, and GI tract.5

FIGURE 2

Another presentation of Sweet’s syndrome

Some Sweet’s syndrome lesions appear "juicy." This lesion occurred at the site of minor trauma (pathergy) in a patient who was febrile and systemically ill.

Treatment: Corticosteroids, not antibiotics

A high clinical suspicion for Sweet’s syndrome is critical to management decisions because the primary treatment is corticosteroids, rather than antibiotics.5,6 Oral prednisone at 0.5 to 1.5 mg/kg per day with taper over 2 to 6 weeks is a standard regimen.2 IV methylprednisolone of up to 1000 mg per day for 3 to 5 days, followed by a tapered oral dose of corticosteroids over several weeks is another option.5 Other first-line treatment options include colchicine (0.5 mg 3 times a day) and oral potassium iodide (300 mg enteric-coated tablets 3 times a day).5,6 Indomethacin, cyclosporine, surgery, and dapsone are other options/adjuncts.

Recurrences of Sweet’s syndrome may occur, regardless of treatment. They are more likely to occur in patients with an underlying malignancy and may herald recurrence of malignancy in a previously treated patient.5 Treating an underlying malignancy (or discontinuing the causative medication in drug-induced Sweet’s syndrome) may resolve symptoms. IV administration of methylprednisolone, as discussed earlier, has been successful for refractory cases.5

Our patient responded well to treatment

Our patient was started on prednisone 60 mg daily and her antibiotics were discontinued. Within 24 hours, her skin lesions regressed. She was discharged on a tapering course of the prednisone.

After several weeks, her lesions completely cleared without scarring or recurrence.

CORRESPONDENCE

Ryan A. Withrow, DO, 4-2807 Reilly Road, Family Medicine Residency Clinic, Fort Bragg, NC 28314; [email protected]

1. Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-356.

2. Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Mosby/Elsevier; 2010.

3. Kemmett D, Hunter JA. Sweet’s syndrome: a clinicopathologic review of twenty-nine cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:503-507.

4. Boatman BW, Taylor RC, Klein LE, et al. Sweet’s syndrome in children. South Med J. 1994;87:193-196.

5. Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome revisited: a review of disease concepts. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:761-778.

6. Von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-556.

1. Sweet RD. An acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1964;76:349-356.

2. Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Mosby/Elsevier; 2010.

3. Kemmett D, Hunter JA. Sweet’s syndrome: a clinicopathologic review of twenty-nine cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:503-507.

4. Boatman BW, Taylor RC, Klein LE, et al. Sweet’s syndrome in children. South Med J. 1994;87:193-196.

5. Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Sweet’s syndrome revisited: a review of disease concepts. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:761-778.

6. Von den Driesch P. Sweet’s syndrome (acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:535-556.

Peeling skin

The family physician diagnosed toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) because >30% of the patient’s skin was desquamating.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) is diagnosed when <10% of the body surface area is involved, SJS/TEN when 10% to 30% is involved, and TEN when >30% is involved. The pathogenesis of SJS, and TEN remains unknown, however recent studies have shown that it may be due to a host-specific, cell-mediated immune response to an antigenic stimulus that activates cytotoxic T-cells and results in damage to keratinocytes.

Drugs most commonly known to cause SJS and TEN are sulfonamide antibiotics, allopurinol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, amine antiepileptic drugs (phenytoin and carbamazepine), and lamotrigine. Mycoplasma pneumoniae has been identified as the most common infectious cause for SJS. Other agents or triggers include radiation therapy, sunlight, pregnancy, connective tissue disease, and menstruation.

The epidermal detachment seen in TEN appears to result from epidermal necrosis in the absence of substantial dermal inflammation. Lesions may progress to form areas of central necrosis, bullae, and denudation.

Fever >39° C is often present. Severe pain can occur. Skin erosions lead to increased insensible blood and fluid losses, as well as an increased risk of bacterial superinfection and sepsis. These patients are at high risk for ocular complications that may lead to blindness.

This particular patient was stabilized with fluids and transferred directly to the burn unit for intensive care. The sulfa antibiotic was stopped since it was likely the triggering agent.

Photo is courtesy of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Division of Dermatology. This case was adapted from: Milana, C. Smith M. Hypersensitivity syndromes. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al., eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:750-755.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The family physician diagnosed toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) because >30% of the patient’s skin was desquamating.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) is diagnosed when <10% of the body surface area is involved, SJS/TEN when 10% to 30% is involved, and TEN when >30% is involved. The pathogenesis of SJS, and TEN remains unknown, however recent studies have shown that it may be due to a host-specific, cell-mediated immune response to an antigenic stimulus that activates cytotoxic T-cells and results in damage to keratinocytes.

Drugs most commonly known to cause SJS and TEN are sulfonamide antibiotics, allopurinol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, amine antiepileptic drugs (phenytoin and carbamazepine), and lamotrigine. Mycoplasma pneumoniae has been identified as the most common infectious cause for SJS. Other agents or triggers include radiation therapy, sunlight, pregnancy, connective tissue disease, and menstruation.

The epidermal detachment seen in TEN appears to result from epidermal necrosis in the absence of substantial dermal inflammation. Lesions may progress to form areas of central necrosis, bullae, and denudation.

Fever >39° C is often present. Severe pain can occur. Skin erosions lead to increased insensible blood and fluid losses, as well as an increased risk of bacterial superinfection and sepsis. These patients are at high risk for ocular complications that may lead to blindness.

This particular patient was stabilized with fluids and transferred directly to the burn unit for intensive care. The sulfa antibiotic was stopped since it was likely the triggering agent.

Photo is courtesy of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Division of Dermatology. This case was adapted from: Milana, C. Smith M. Hypersensitivity syndromes. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al., eds. The Color Atlas of Family Medicine. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009:750-755.

To learn more about The Color Atlas of Family Medicine, see:

* http://www.amazon.com/Color-Atlas-Family-Medicine/dp/0071474641

The family physician diagnosed toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) because >30% of the patient’s skin was desquamating.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) is diagnosed when <10% of the body surface area is involved, SJS/TEN when 10% to 30% is involved, and TEN when >30% is involved. The pathogenesis of SJS, and TEN remains unknown, however recent studies have shown that it may be due to a host-specific, cell-mediated immune response to an antigenic stimulus that activates cytotoxic T-cells and results in damage to keratinocytes.