User login

VIDEO: What you need to know about MACRA, Medicare pay

BOSTON – When the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act goes into effect in 2019, will you be ready?

In a video interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians, Robert B. Doherty, senior vice president of governmental affairs and public policy for the ACP, outlined what physicians need to know about Medicare’s post–Sustainable Growth Rate payment structures, including the difference between MIPS and ACMs.

He also explained how these new Medicare payment structures give physicians more control over their reimbursements while also requiring physicians to endure greater risk.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

BOSTON – When the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act goes into effect in 2019, will you be ready?

In a video interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians, Robert B. Doherty, senior vice president of governmental affairs and public policy for the ACP, outlined what physicians need to know about Medicare’s post–Sustainable Growth Rate payment structures, including the difference between MIPS and ACMs.

He also explained how these new Medicare payment structures give physicians more control over their reimbursements while also requiring physicians to endure greater risk.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

BOSTON – When the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act goes into effect in 2019, will you be ready?

In a video interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians, Robert B. Doherty, senior vice president of governmental affairs and public policy for the ACP, outlined what physicians need to know about Medicare’s post–Sustainable Growth Rate payment structures, including the difference between MIPS and ACMs.

He also explained how these new Medicare payment structures give physicians more control over their reimbursements while also requiring physicians to endure greater risk.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT ACP INTERNAL MEDICINE 2015

Professionalism, self-governance addressed in themed JAMA issue

The U.S. medical system is changing, and the traditional self-governing of the medical profession and physician professionalism is being challenged, according to a series of viewpoints published in a themed issue of JAMA.

The importance of the patient’s well-being in physician professionalism and how medical training encourages this in medical students is one of the major themes addressed in the issue. Also addressed is the topic of ensuring physician competency and professionalism through licensing, maintenance of certification, and accreditation processes.

“The aim of each physician clearly should be to care for and protect the interests and well-being of patients to the best of that physician’s abilities, while making sure her or his abilities are maintained as new discoveries are made,” Dr. Catherine D. DeAngelis, editor in chief emerita of JAMA, wrote in an editorial (JAMA 2015;313:1837-8 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.3597]). “Characterizing the qualities that determine professionalism in physicians is more difficult. Terms used to define the qualities of medical professionalism include sound knowledge and skills (clinical competence), excellence, accountability, sound work ethic, good communication, wise application of legal understanding, ethical conduct, humanism, altruism, and self-regulation with accountability.”

Learn more in the May 12 issue of JAMA.

The U.S. medical system is changing, and the traditional self-governing of the medical profession and physician professionalism is being challenged, according to a series of viewpoints published in a themed issue of JAMA.

The importance of the patient’s well-being in physician professionalism and how medical training encourages this in medical students is one of the major themes addressed in the issue. Also addressed is the topic of ensuring physician competency and professionalism through licensing, maintenance of certification, and accreditation processes.

“The aim of each physician clearly should be to care for and protect the interests and well-being of patients to the best of that physician’s abilities, while making sure her or his abilities are maintained as new discoveries are made,” Dr. Catherine D. DeAngelis, editor in chief emerita of JAMA, wrote in an editorial (JAMA 2015;313:1837-8 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.3597]). “Characterizing the qualities that determine professionalism in physicians is more difficult. Terms used to define the qualities of medical professionalism include sound knowledge and skills (clinical competence), excellence, accountability, sound work ethic, good communication, wise application of legal understanding, ethical conduct, humanism, altruism, and self-regulation with accountability.”

Learn more in the May 12 issue of JAMA.

The U.S. medical system is changing, and the traditional self-governing of the medical profession and physician professionalism is being challenged, according to a series of viewpoints published in a themed issue of JAMA.

The importance of the patient’s well-being in physician professionalism and how medical training encourages this in medical students is one of the major themes addressed in the issue. Also addressed is the topic of ensuring physician competency and professionalism through licensing, maintenance of certification, and accreditation processes.

“The aim of each physician clearly should be to care for and protect the interests and well-being of patients to the best of that physician’s abilities, while making sure her or his abilities are maintained as new discoveries are made,” Dr. Catherine D. DeAngelis, editor in chief emerita of JAMA, wrote in an editorial (JAMA 2015;313:1837-8 [doi:10.1001/jama.2015.3597]). “Characterizing the qualities that determine professionalism in physicians is more difficult. Terms used to define the qualities of medical professionalism include sound knowledge and skills (clinical competence), excellence, accountability, sound work ethic, good communication, wise application of legal understanding, ethical conduct, humanism, altruism, and self-regulation with accountability.”

Learn more in the May 12 issue of JAMA.

Malpractice settlement details often hidden, safety effects unsure

The majority of malpractice settlement agreements made by a Texas health system included clauses that prevented details about the case from being released, but there was little standardization or consistency in such provisions, according to a study published online May 11 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Such nondisclosure provisions, while common in settlements across the United States, run contrary to greater promotion of health care transparency and improved patient safety, the study’s authors said.

Dr. William M. Sage of the University of Texas at Austin, and his colleagues, analyzed settlement agreements made by the University of Texas System from 2001 to 2002, from 2006 to 2007, and from 2009 to 2012 (JAMA Intern. Med. 2015 May 11 [doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1035]). They chose the time frames to study the differences in settlements before, during, and after the enactment of tort reform in Texas.

In 2003, Texas amended its constitution and enacted legislation that capped noneconomic damages against physicians in medical malpractice cases at $250,000 and imposed limitations on personal-injury lawsuits.

During the study periods, the University of Texas System closed 715 malpractice claims and made 150 settlement payments. The median compensation paid by the university was $100,000, and the mean compensation was $185,372.

Excluding 20 cases involving non–University of Texas defendants and 6 minor dental injury cases, 89% of settlements (110 of 124) included nondisclosure provisions. All the nondisclosure clauses prohibited disclosure of the settlement terms and amount. The nondisclosure clauses ranged in length from 23 to 385 words. Ten of the nondisclosure clauses applied to all parties to the agreement, including the physicians and hospitals.

Of the nondisclosure provisions, 55.5% prohibited disclosure that the settlement had been reached, 46.4% prohibited disclosure of the facts of the claim, and 9.1% prohibited disclosure by the settling physicians and hospitals, as well as the plaintiff.

In addition, 2.7% of nondisclosure provisions specifically prohibited disparagement of the physicians or hospital by the claimant. Complaints to the Texas Medical Board or other regulatory bodies were prohibited in 26.4% of nondisclosure provision cases.

Researchers found that the 50 settlement agreements signed after tort reform took full effect in Texas (2009-2012) had stricter nondisclosure provisions than did the 60 signed in earlier years. Settlements made after tort reform were more likely to prohibit disclosure of the event of settlement, to prohibit disclosure of the facts of the claims, and to prohibit reporting to regulatory bodies.

The study authors noted that in response to the findings of their study, as of 2014, the University of Texas no longer restricts regulatory reporting in settlement agreements.

Nondisclosure clauses that go beyond nondisparagement, as well as restrictions on disclosing the payment amount, appear inconsistent with respect to patients and current approaches to improving the safety of medical care, noted Dr. Sage and his coauthors.

“In situations where the harm is more general or might occur again, confidential settlement of private litigation can be contrary to the public interest,” the authors wrote. “There is increasing consensus, even among early proponents of protected peer review, that greater transparency to patients and the public is necessary for safety to improve.”

The use of nondisclosure agreements should be reviewed elsewhere, the researchers suggested, including at institutions with communication-and-resolution programs.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @legal_med

The study by Dr. Sage and colleagues offers a rare glimpse into the world of medical malpractice settlements, and raises serious questions about why many case details are hidden from the public.

In malpractice settlements, some types of nondisclosure provisions can never be justified, and others should remain subject to negotiation. Because patients should not be forced to choose between compensation and acting on a perceived ethical obligation to try to prevent harm to others, settlement agreements should not restrict reporting to regulatory bodies. In addition, adopting state statutes that prohibit these provisions involves less burden and uncertainty for plaintiffs than requiring plaintiffs to challenge them in court.

Michelle M. Mello, Ph.D., J.D., of Stanford Law School and Stanford School of Medicine, and Jeffrey N. Catalano, a Boston attorney, made these comments in an editorial (JAMA Intern. Med. 2015 May 11 [doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1038]). Mr. Catalano reported that he is a practicing attorney who represents medical malpractice plaintiffs. No other disclosures were reported.

The study by Dr. Sage and colleagues offers a rare glimpse into the world of medical malpractice settlements, and raises serious questions about why many case details are hidden from the public.

In malpractice settlements, some types of nondisclosure provisions can never be justified, and others should remain subject to negotiation. Because patients should not be forced to choose between compensation and acting on a perceived ethical obligation to try to prevent harm to others, settlement agreements should not restrict reporting to regulatory bodies. In addition, adopting state statutes that prohibit these provisions involves less burden and uncertainty for plaintiffs than requiring plaintiffs to challenge them in court.

Michelle M. Mello, Ph.D., J.D., of Stanford Law School and Stanford School of Medicine, and Jeffrey N. Catalano, a Boston attorney, made these comments in an editorial (JAMA Intern. Med. 2015 May 11 [doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1038]). Mr. Catalano reported that he is a practicing attorney who represents medical malpractice plaintiffs. No other disclosures were reported.

The study by Dr. Sage and colleagues offers a rare glimpse into the world of medical malpractice settlements, and raises serious questions about why many case details are hidden from the public.

In malpractice settlements, some types of nondisclosure provisions can never be justified, and others should remain subject to negotiation. Because patients should not be forced to choose between compensation and acting on a perceived ethical obligation to try to prevent harm to others, settlement agreements should not restrict reporting to regulatory bodies. In addition, adopting state statutes that prohibit these provisions involves less burden and uncertainty for plaintiffs than requiring plaintiffs to challenge them in court.

Michelle M. Mello, Ph.D., J.D., of Stanford Law School and Stanford School of Medicine, and Jeffrey N. Catalano, a Boston attorney, made these comments in an editorial (JAMA Intern. Med. 2015 May 11 [doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1038]). Mr. Catalano reported that he is a practicing attorney who represents medical malpractice plaintiffs. No other disclosures were reported.

The majority of malpractice settlement agreements made by a Texas health system included clauses that prevented details about the case from being released, but there was little standardization or consistency in such provisions, according to a study published online May 11 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Such nondisclosure provisions, while common in settlements across the United States, run contrary to greater promotion of health care transparency and improved patient safety, the study’s authors said.

Dr. William M. Sage of the University of Texas at Austin, and his colleagues, analyzed settlement agreements made by the University of Texas System from 2001 to 2002, from 2006 to 2007, and from 2009 to 2012 (JAMA Intern. Med. 2015 May 11 [doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1035]). They chose the time frames to study the differences in settlements before, during, and after the enactment of tort reform in Texas.

In 2003, Texas amended its constitution and enacted legislation that capped noneconomic damages against physicians in medical malpractice cases at $250,000 and imposed limitations on personal-injury lawsuits.

During the study periods, the University of Texas System closed 715 malpractice claims and made 150 settlement payments. The median compensation paid by the university was $100,000, and the mean compensation was $185,372.

Excluding 20 cases involving non–University of Texas defendants and 6 minor dental injury cases, 89% of settlements (110 of 124) included nondisclosure provisions. All the nondisclosure clauses prohibited disclosure of the settlement terms and amount. The nondisclosure clauses ranged in length from 23 to 385 words. Ten of the nondisclosure clauses applied to all parties to the agreement, including the physicians and hospitals.

Of the nondisclosure provisions, 55.5% prohibited disclosure that the settlement had been reached, 46.4% prohibited disclosure of the facts of the claim, and 9.1% prohibited disclosure by the settling physicians and hospitals, as well as the plaintiff.

In addition, 2.7% of nondisclosure provisions specifically prohibited disparagement of the physicians or hospital by the claimant. Complaints to the Texas Medical Board or other regulatory bodies were prohibited in 26.4% of nondisclosure provision cases.

Researchers found that the 50 settlement agreements signed after tort reform took full effect in Texas (2009-2012) had stricter nondisclosure provisions than did the 60 signed in earlier years. Settlements made after tort reform were more likely to prohibit disclosure of the event of settlement, to prohibit disclosure of the facts of the claims, and to prohibit reporting to regulatory bodies.

The study authors noted that in response to the findings of their study, as of 2014, the University of Texas no longer restricts regulatory reporting in settlement agreements.

Nondisclosure clauses that go beyond nondisparagement, as well as restrictions on disclosing the payment amount, appear inconsistent with respect to patients and current approaches to improving the safety of medical care, noted Dr. Sage and his coauthors.

“In situations where the harm is more general or might occur again, confidential settlement of private litigation can be contrary to the public interest,” the authors wrote. “There is increasing consensus, even among early proponents of protected peer review, that greater transparency to patients and the public is necessary for safety to improve.”

The use of nondisclosure agreements should be reviewed elsewhere, the researchers suggested, including at institutions with communication-and-resolution programs.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @legal_med

The majority of malpractice settlement agreements made by a Texas health system included clauses that prevented details about the case from being released, but there was little standardization or consistency in such provisions, according to a study published online May 11 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Such nondisclosure provisions, while common in settlements across the United States, run contrary to greater promotion of health care transparency and improved patient safety, the study’s authors said.

Dr. William M. Sage of the University of Texas at Austin, and his colleagues, analyzed settlement agreements made by the University of Texas System from 2001 to 2002, from 2006 to 2007, and from 2009 to 2012 (JAMA Intern. Med. 2015 May 11 [doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1035]). They chose the time frames to study the differences in settlements before, during, and after the enactment of tort reform in Texas.

In 2003, Texas amended its constitution and enacted legislation that capped noneconomic damages against physicians in medical malpractice cases at $250,000 and imposed limitations on personal-injury lawsuits.

During the study periods, the University of Texas System closed 715 malpractice claims and made 150 settlement payments. The median compensation paid by the university was $100,000, and the mean compensation was $185,372.

Excluding 20 cases involving non–University of Texas defendants and 6 minor dental injury cases, 89% of settlements (110 of 124) included nondisclosure provisions. All the nondisclosure clauses prohibited disclosure of the settlement terms and amount. The nondisclosure clauses ranged in length from 23 to 385 words. Ten of the nondisclosure clauses applied to all parties to the agreement, including the physicians and hospitals.

Of the nondisclosure provisions, 55.5% prohibited disclosure that the settlement had been reached, 46.4% prohibited disclosure of the facts of the claim, and 9.1% prohibited disclosure by the settling physicians and hospitals, as well as the plaintiff.

In addition, 2.7% of nondisclosure provisions specifically prohibited disparagement of the physicians or hospital by the claimant. Complaints to the Texas Medical Board or other regulatory bodies were prohibited in 26.4% of nondisclosure provision cases.

Researchers found that the 50 settlement agreements signed after tort reform took full effect in Texas (2009-2012) had stricter nondisclosure provisions than did the 60 signed in earlier years. Settlements made after tort reform were more likely to prohibit disclosure of the event of settlement, to prohibit disclosure of the facts of the claims, and to prohibit reporting to regulatory bodies.

The study authors noted that in response to the findings of their study, as of 2014, the University of Texas no longer restricts regulatory reporting in settlement agreements.

Nondisclosure clauses that go beyond nondisparagement, as well as restrictions on disclosing the payment amount, appear inconsistent with respect to patients and current approaches to improving the safety of medical care, noted Dr. Sage and his coauthors.

“In situations where the harm is more general or might occur again, confidential settlement of private litigation can be contrary to the public interest,” the authors wrote. “There is increasing consensus, even among early proponents of protected peer review, that greater transparency to patients and the public is necessary for safety to improve.”

The use of nondisclosure agreements should be reviewed elsewhere, the researchers suggested, including at institutions with communication-and-resolution programs.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

On Twitter @legal_med

Key clinical point: Most malpractice settlements include nondisclosure provisions, but the clauses are inconsistent and lack standardization.

Major finding: Of 124 malpractice settlements made by the University of Texas System, 89% (110 settlements) included nondisclosure provisions. All the nondisclosure clauses prohibited disclosure of the settlement terms and amount, but the provisions varied in length and scope.

Data source: Review of 150 medical malpractice settlements made by the University of Texas System from 2001 to 2002, from 2006 to 2007, and from 2009 to 2012.

Disclosures: The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Emergency physicians’ poll indicates increased volume of emergency visits

Emergency department visits are on the rise, based on an American College of Emergency Physicians’ survey.

According to the results of ACEP’s March 2015 poll of 2.099 emergency physicians, 75% have noted an increase in the volume of ED visits since the implementation of the Affordable Care Act in 2014; 47% have noticed a slight increase, and 28% said that volumes have greatly increased.

Additionally, 70% of respondents said their emergency departments are not adequately prepared for potentially significant increases in patient volume.

Dr. Ryan A. Stanton, an emergency physician with MESA Medical Group in Lexington, Ky., said in an interview that respondents likely have data to back up their opinions. Data from his hospital shows ED volume increases of 20% in 2014.

The poll results were “not surprising at all,” he said, and reflect a need “to bolster up the health care system that is going to support” the increased patient volume that comes with greater coverage due to the ACA.

Emergency department visits are on the rise, based on an American College of Emergency Physicians’ survey.

According to the results of ACEP’s March 2015 poll of 2.099 emergency physicians, 75% have noted an increase in the volume of ED visits since the implementation of the Affordable Care Act in 2014; 47% have noticed a slight increase, and 28% said that volumes have greatly increased.

Additionally, 70% of respondents said their emergency departments are not adequately prepared for potentially significant increases in patient volume.

Dr. Ryan A. Stanton, an emergency physician with MESA Medical Group in Lexington, Ky., said in an interview that respondents likely have data to back up their opinions. Data from his hospital shows ED volume increases of 20% in 2014.

The poll results were “not surprising at all,” he said, and reflect a need “to bolster up the health care system that is going to support” the increased patient volume that comes with greater coverage due to the ACA.

Emergency department visits are on the rise, based on an American College of Emergency Physicians’ survey.

According to the results of ACEP’s March 2015 poll of 2.099 emergency physicians, 75% have noted an increase in the volume of ED visits since the implementation of the Affordable Care Act in 2014; 47% have noticed a slight increase, and 28% said that volumes have greatly increased.

Additionally, 70% of respondents said their emergency departments are not adequately prepared for potentially significant increases in patient volume.

Dr. Ryan A. Stanton, an emergency physician with MESA Medical Group in Lexington, Ky., said in an interview that respondents likely have data to back up their opinions. Data from his hospital shows ED volume increases of 20% in 2014.

The poll results were “not surprising at all,” he said, and reflect a need “to bolster up the health care system that is going to support” the increased patient volume that comes with greater coverage due to the ACA.

To Battle Burnout, Jerome C. Siy, MD, CHIE, SFHM, Instructs Hospitalist Leaders to Engage, Communicate, and Create a “Culture”

Studies show nearly one in three hospitalists will experience long-term exhaustion or diminished interest in their work.1 Burned out physicians have low empathy, don’t communicate well, and provide poor quality of care. Not only does burnout lower quality of care, it is also costly and affects physicians’ personal lives. Unfortunately, despite more than a decade of research and effort to improve burnout, there seems to be no secret formula.

“We see burnout in our quality metrics. We see it in increased medical errors. Patient compliance can be tied to burnout and poor patient satisfaction, as well,” said Jerome C. Siy, MD, CHIE, SFHM, during his HM15 session last month at the Gaylord National Resort and Conference Center in National Harbor, Md. “What is really important to understand is that burnout results in high turnover and early retirement. Conservative estimates tell us a burned out physician can cost the hospital system $250,000.”

Dr. Siy’s talk, “Preventing Hospitalist Burnout through Engagement,” went beyond the basics of burnout (higher rates of substance abuse, depression, suicidal ideation, and family conflicts) and explored the systematic reasons for its occurrence in hospital medicine. The 2009 winner of SHM’s Award for Clinical Excellence also outlined a handful of ways HM groups can engage and combat burnout.

“What is interesting is that the rate that our profession has burnout is inversely proportional to the rate of the U.S. general population,” said Dr. Siy, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota Medical School and department head of hospital medicine at HealthPartners Medical Group in Minneapolis. “In the general U.S. population, the higher your level of education, the lower the rates of burnout. And yet we, physicians, have a remarkably high rate of burnout compared with those at our education level.

“And when they broke it out by specialty, it was front-line physicians that have the highest rates of burnout.”

Dr. Siy says burnout is partly the fault of the “system,” in terms of workload and performance pressures. His hospitalist group has implemented mindfulness training with a guru and empathy training with age simulators. They employ geographic-based teams and bedside rounds with nursing. They’ve even hired scribes on the observation unit.

“Not only are we trying to address burnout from the individual physician perspective, but we’re trying to address the causes of burnout,” he says.

Dr. Siy also showed attendees a video on engagement by best-selling author Daniel Pink. The three factors Pink believes lead to better performance and personal satisfaction are autonomy, mastery, purpose. And Pink encourages business leaders to “take compensation off the table.”

“He talks about how compensation is important and drives things, but actually, if you are fair with your compensation, it no longer incents your workforce,” Dr. Siy reiterates. “So if compensation is a big issue for you, you should know that.”

Most important, he says, “It’s about creating a culture.” He provided this list of ways to engage hospitalists:

- Add a measure of physician engagement to your scorecard;

- Translate engagement data by having presence in the workspace, even when off service;

- Employ individualized and group time to provide feedback and mentoring, develop relationships, learn new skills, and grow;

- Have physicians lead and partner in quality improvement efforts;

- Have regular, formal meetings with opportunities for open discussion;

- Incorporate professional development into your culture;

- Develop a common sense of purpose inside and outside of the hospital; and

- Structure compensation to reflect your values.

“Everyone in your group has to have an opportunity to grow,” he says. “They need to know that you, the group leaders … and the system care about them.” TH

Reference

1. Hinami K, Whelan CT, Miller JA, Wolosin RJ, Wetterneck TB, Society of Hospital Medicine Career Satisfaction Task Force. Job characteristics, satisfaction, and burnout across hospitalist practice models. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):402-410.

Studies show nearly one in three hospitalists will experience long-term exhaustion or diminished interest in their work.1 Burned out physicians have low empathy, don’t communicate well, and provide poor quality of care. Not only does burnout lower quality of care, it is also costly and affects physicians’ personal lives. Unfortunately, despite more than a decade of research and effort to improve burnout, there seems to be no secret formula.

“We see burnout in our quality metrics. We see it in increased medical errors. Patient compliance can be tied to burnout and poor patient satisfaction, as well,” said Jerome C. Siy, MD, CHIE, SFHM, during his HM15 session last month at the Gaylord National Resort and Conference Center in National Harbor, Md. “What is really important to understand is that burnout results in high turnover and early retirement. Conservative estimates tell us a burned out physician can cost the hospital system $250,000.”

Dr. Siy’s talk, “Preventing Hospitalist Burnout through Engagement,” went beyond the basics of burnout (higher rates of substance abuse, depression, suicidal ideation, and family conflicts) and explored the systematic reasons for its occurrence in hospital medicine. The 2009 winner of SHM’s Award for Clinical Excellence also outlined a handful of ways HM groups can engage and combat burnout.

“What is interesting is that the rate that our profession has burnout is inversely proportional to the rate of the U.S. general population,” said Dr. Siy, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota Medical School and department head of hospital medicine at HealthPartners Medical Group in Minneapolis. “In the general U.S. population, the higher your level of education, the lower the rates of burnout. And yet we, physicians, have a remarkably high rate of burnout compared with those at our education level.

“And when they broke it out by specialty, it was front-line physicians that have the highest rates of burnout.”

Dr. Siy says burnout is partly the fault of the “system,” in terms of workload and performance pressures. His hospitalist group has implemented mindfulness training with a guru and empathy training with age simulators. They employ geographic-based teams and bedside rounds with nursing. They’ve even hired scribes on the observation unit.

“Not only are we trying to address burnout from the individual physician perspective, but we’re trying to address the causes of burnout,” he says.

Dr. Siy also showed attendees a video on engagement by best-selling author Daniel Pink. The three factors Pink believes lead to better performance and personal satisfaction are autonomy, mastery, purpose. And Pink encourages business leaders to “take compensation off the table.”

“He talks about how compensation is important and drives things, but actually, if you are fair with your compensation, it no longer incents your workforce,” Dr. Siy reiterates. “So if compensation is a big issue for you, you should know that.”

Most important, he says, “It’s about creating a culture.” He provided this list of ways to engage hospitalists:

- Add a measure of physician engagement to your scorecard;

- Translate engagement data by having presence in the workspace, even when off service;

- Employ individualized and group time to provide feedback and mentoring, develop relationships, learn new skills, and grow;

- Have physicians lead and partner in quality improvement efforts;

- Have regular, formal meetings with opportunities for open discussion;

- Incorporate professional development into your culture;

- Develop a common sense of purpose inside and outside of the hospital; and

- Structure compensation to reflect your values.

“Everyone in your group has to have an opportunity to grow,” he says. “They need to know that you, the group leaders … and the system care about them.” TH

Reference

1. Hinami K, Whelan CT, Miller JA, Wolosin RJ, Wetterneck TB, Society of Hospital Medicine Career Satisfaction Task Force. Job characteristics, satisfaction, and burnout across hospitalist practice models. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):402-410.

Studies show nearly one in three hospitalists will experience long-term exhaustion or diminished interest in their work.1 Burned out physicians have low empathy, don’t communicate well, and provide poor quality of care. Not only does burnout lower quality of care, it is also costly and affects physicians’ personal lives. Unfortunately, despite more than a decade of research and effort to improve burnout, there seems to be no secret formula.

“We see burnout in our quality metrics. We see it in increased medical errors. Patient compliance can be tied to burnout and poor patient satisfaction, as well,” said Jerome C. Siy, MD, CHIE, SFHM, during his HM15 session last month at the Gaylord National Resort and Conference Center in National Harbor, Md. “What is really important to understand is that burnout results in high turnover and early retirement. Conservative estimates tell us a burned out physician can cost the hospital system $250,000.”

Dr. Siy’s talk, “Preventing Hospitalist Burnout through Engagement,” went beyond the basics of burnout (higher rates of substance abuse, depression, suicidal ideation, and family conflicts) and explored the systematic reasons for its occurrence in hospital medicine. The 2009 winner of SHM’s Award for Clinical Excellence also outlined a handful of ways HM groups can engage and combat burnout.

“What is interesting is that the rate that our profession has burnout is inversely proportional to the rate of the U.S. general population,” said Dr. Siy, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota Medical School and department head of hospital medicine at HealthPartners Medical Group in Minneapolis. “In the general U.S. population, the higher your level of education, the lower the rates of burnout. And yet we, physicians, have a remarkably high rate of burnout compared with those at our education level.

“And when they broke it out by specialty, it was front-line physicians that have the highest rates of burnout.”

Dr. Siy says burnout is partly the fault of the “system,” in terms of workload and performance pressures. His hospitalist group has implemented mindfulness training with a guru and empathy training with age simulators. They employ geographic-based teams and bedside rounds with nursing. They’ve even hired scribes on the observation unit.

“Not only are we trying to address burnout from the individual physician perspective, but we’re trying to address the causes of burnout,” he says.

Dr. Siy also showed attendees a video on engagement by best-selling author Daniel Pink. The three factors Pink believes lead to better performance and personal satisfaction are autonomy, mastery, purpose. And Pink encourages business leaders to “take compensation off the table.”

“He talks about how compensation is important and drives things, but actually, if you are fair with your compensation, it no longer incents your workforce,” Dr. Siy reiterates. “So if compensation is a big issue for you, you should know that.”

Most important, he says, “It’s about creating a culture.” He provided this list of ways to engage hospitalists:

- Add a measure of physician engagement to your scorecard;

- Translate engagement data by having presence in the workspace, even when off service;

- Employ individualized and group time to provide feedback and mentoring, develop relationships, learn new skills, and grow;

- Have physicians lead and partner in quality improvement efforts;

- Have regular, formal meetings with opportunities for open discussion;

- Incorporate professional development into your culture;

- Develop a common sense of purpose inside and outside of the hospital; and

- Structure compensation to reflect your values.

“Everyone in your group has to have an opportunity to grow,” he says. “They need to know that you, the group leaders … and the system care about them.” TH

Reference

1. Hinami K, Whelan CT, Miller JA, Wolosin RJ, Wetterneck TB, Society of Hospital Medicine Career Satisfaction Task Force. Job characteristics, satisfaction, and burnout across hospitalist practice models. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):402-410.

HM15 Offers Hospitalist Leaders Training, Encouragement

NATIONAL HARBOR, Md.—Patient satisfaction, physician engagement, and administrator buy-in, oh my.

So went the thoughts of Jaidev Bhoopal, MD, last month at HM15. He’d been a hospitalist for about eight years, but he was named section chair about a month before he arrived at the annual meeting. His calculated first stop was the daylong practice management pre-course titled “Where the Rubber Meets the Road: Managing in the Era of Healthcare Reform.”

The timing couldn’t have been better.

“I’m starting a new role and I wanted to get input and ideas,” said Dr. Bhoopal, section chair of the hospitalist department at St. Mary’s Medical Center in Duluth, Minn. “This gives you a playbook of where you want to be and where you want to go.”

A playbook for where to go could just as well be the slogan for practice management’s role at SHM’s annual meeting. An educational track, a dedicated—and ever-popular—pre-course, and a chance to ask the field’s founding fathers their best practices were among the highlights of this spring’s four-day confab.

The need for practice management and leadership training is greater in the past few years as hospitalists have been more confounded than ever with how to best run their practices under a myriad of new rules and regulations tied to the Affordable Care Act and the digitization of healthcare. At their core, the changes are shifting hospital-based care from fee-for-service to value-based payments.

“The tipping point is really here for us,” said Win Whitcomb, MD, MHM, chief medical officer of Remedy Partners of Darien, Conn.

Dr. Whitcomb, a founder of SHM and regular columnist for The Hospitalist, said that HM group (HMG) leaders have to be well versed in how to navigate a landscape of alternative payment models to excel in the new paradigm. Particularly after the announcement earlier this year that the federal government has set a goal of tying 85% of Medicare hospital fee-for-service payments to quality or value by 2016, and that percentage could increase to 90% by 2018. The January announcement was the first time in Medicare’s history that explicit goals for alternative payment models and value-based payments were set, according to an announcement from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

“Strategically, these things are essential to work into the plan of what the hospital medicine group is doing in the coming three to five years,” Dr. Whitcomb said. “Hospitalists can’t do this alone. They have to do it with teams. It’s not only teams of other professionals in the hospital and around the hospital, but it’s other physicians.”

Dr. Whitcomb said key to the new paradigm is shared financial and clinical responsibilities. He says hospitalists have to “change our thinking…to a mindset where we’re in this together.”

Part of that shared responsibility extends to the post-acute care setting, where SHM senior vice president for practice management Joseph Miller said that some 30% of HMGs are practicing. To help those practitioners, SHM and IPC Healthcare of North Hollywood, Calif., debuted the “Primer for Hospitalists on Skilled Nursing Facilities” at HM15.

The educational program, housed at SHM’s Learning Portal, has 32 lessons meant to differentiate the traditional acute-care hospital from post-acute care facilities. It is grouped in five sections and two modules, with a focus on skilled-nursing facilities (SNFs), which are the most common post-acute care settings.

“The types of resources that are available are different, and that’s not only in terms of staff, but the availability of specialists, the availability of testing capabilities,” Miller said. “If you need to work with a cardiologist for a particular patient...how do you engage them? You’re not going to be able to have them come and see that patient frequently. How do you communicate with them to get the feedback you need as the attending physician?”

Another communication hassle involves the growing number of HMGs spread over multiple sites. For Sara Shraibman, MD, an assistant program director at Syosset Hospital in Syosset, N.Y., those sites are two hospitals covered by the North Shore LIJ Medical Group.

“It’s actually a new program, so we are trying to look at our compensation, models comparing them across two hospitals…and how we manage,” she said. “Not every hospitalist will go back and forth. Some will, some won’t. Some will work nights to help cover, some won’t. It’s very interesting trying to come up with a schedule.”

The best way to address conflict at multi-site groups is communicating and focusing on shared goals, said David Weidig, MD, director of hospital medicine for Aurora Medical Group in West Allis, Wis., and a new member of Team Hospitalist.

“Make sure that no matter what conflict might be up front, that everybody is looking at the goals downstream and saying, ‘Yes, that is a goal we want to achieve. We want to have better patient safety metrics. We want to have decreased readmissions. We want to have better transitions of care,’” Dr. Weidig said. “The common goal all the way from hospital administrators all the way down to hospital physicians is going to be the key.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

NATIONAL HARBOR, Md.—Patient satisfaction, physician engagement, and administrator buy-in, oh my.

So went the thoughts of Jaidev Bhoopal, MD, last month at HM15. He’d been a hospitalist for about eight years, but he was named section chair about a month before he arrived at the annual meeting. His calculated first stop was the daylong practice management pre-course titled “Where the Rubber Meets the Road: Managing in the Era of Healthcare Reform.”

The timing couldn’t have been better.

“I’m starting a new role and I wanted to get input and ideas,” said Dr. Bhoopal, section chair of the hospitalist department at St. Mary’s Medical Center in Duluth, Minn. “This gives you a playbook of where you want to be and where you want to go.”

A playbook for where to go could just as well be the slogan for practice management’s role at SHM’s annual meeting. An educational track, a dedicated—and ever-popular—pre-course, and a chance to ask the field’s founding fathers their best practices were among the highlights of this spring’s four-day confab.

The need for practice management and leadership training is greater in the past few years as hospitalists have been more confounded than ever with how to best run their practices under a myriad of new rules and regulations tied to the Affordable Care Act and the digitization of healthcare. At their core, the changes are shifting hospital-based care from fee-for-service to value-based payments.

“The tipping point is really here for us,” said Win Whitcomb, MD, MHM, chief medical officer of Remedy Partners of Darien, Conn.

Dr. Whitcomb, a founder of SHM and regular columnist for The Hospitalist, said that HM group (HMG) leaders have to be well versed in how to navigate a landscape of alternative payment models to excel in the new paradigm. Particularly after the announcement earlier this year that the federal government has set a goal of tying 85% of Medicare hospital fee-for-service payments to quality or value by 2016, and that percentage could increase to 90% by 2018. The January announcement was the first time in Medicare’s history that explicit goals for alternative payment models and value-based payments were set, according to an announcement from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

“Strategically, these things are essential to work into the plan of what the hospital medicine group is doing in the coming three to five years,” Dr. Whitcomb said. “Hospitalists can’t do this alone. They have to do it with teams. It’s not only teams of other professionals in the hospital and around the hospital, but it’s other physicians.”

Dr. Whitcomb said key to the new paradigm is shared financial and clinical responsibilities. He says hospitalists have to “change our thinking…to a mindset where we’re in this together.”

Part of that shared responsibility extends to the post-acute care setting, where SHM senior vice president for practice management Joseph Miller said that some 30% of HMGs are practicing. To help those practitioners, SHM and IPC Healthcare of North Hollywood, Calif., debuted the “Primer for Hospitalists on Skilled Nursing Facilities” at HM15.

The educational program, housed at SHM’s Learning Portal, has 32 lessons meant to differentiate the traditional acute-care hospital from post-acute care facilities. It is grouped in five sections and two modules, with a focus on skilled-nursing facilities (SNFs), which are the most common post-acute care settings.

“The types of resources that are available are different, and that’s not only in terms of staff, but the availability of specialists, the availability of testing capabilities,” Miller said. “If you need to work with a cardiologist for a particular patient...how do you engage them? You’re not going to be able to have them come and see that patient frequently. How do you communicate with them to get the feedback you need as the attending physician?”

Another communication hassle involves the growing number of HMGs spread over multiple sites. For Sara Shraibman, MD, an assistant program director at Syosset Hospital in Syosset, N.Y., those sites are two hospitals covered by the North Shore LIJ Medical Group.

“It’s actually a new program, so we are trying to look at our compensation, models comparing them across two hospitals…and how we manage,” she said. “Not every hospitalist will go back and forth. Some will, some won’t. Some will work nights to help cover, some won’t. It’s very interesting trying to come up with a schedule.”

The best way to address conflict at multi-site groups is communicating and focusing on shared goals, said David Weidig, MD, director of hospital medicine for Aurora Medical Group in West Allis, Wis., and a new member of Team Hospitalist.

“Make sure that no matter what conflict might be up front, that everybody is looking at the goals downstream and saying, ‘Yes, that is a goal we want to achieve. We want to have better patient safety metrics. We want to have decreased readmissions. We want to have better transitions of care,’” Dr. Weidig said. “The common goal all the way from hospital administrators all the way down to hospital physicians is going to be the key.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

NATIONAL HARBOR, Md.—Patient satisfaction, physician engagement, and administrator buy-in, oh my.

So went the thoughts of Jaidev Bhoopal, MD, last month at HM15. He’d been a hospitalist for about eight years, but he was named section chair about a month before he arrived at the annual meeting. His calculated first stop was the daylong practice management pre-course titled “Where the Rubber Meets the Road: Managing in the Era of Healthcare Reform.”

The timing couldn’t have been better.

“I’m starting a new role and I wanted to get input and ideas,” said Dr. Bhoopal, section chair of the hospitalist department at St. Mary’s Medical Center in Duluth, Minn. “This gives you a playbook of where you want to be and where you want to go.”

A playbook for where to go could just as well be the slogan for practice management’s role at SHM’s annual meeting. An educational track, a dedicated—and ever-popular—pre-course, and a chance to ask the field’s founding fathers their best practices were among the highlights of this spring’s four-day confab.

The need for practice management and leadership training is greater in the past few years as hospitalists have been more confounded than ever with how to best run their practices under a myriad of new rules and regulations tied to the Affordable Care Act and the digitization of healthcare. At their core, the changes are shifting hospital-based care from fee-for-service to value-based payments.

“The tipping point is really here for us,” said Win Whitcomb, MD, MHM, chief medical officer of Remedy Partners of Darien, Conn.

Dr. Whitcomb, a founder of SHM and regular columnist for The Hospitalist, said that HM group (HMG) leaders have to be well versed in how to navigate a landscape of alternative payment models to excel in the new paradigm. Particularly after the announcement earlier this year that the federal government has set a goal of tying 85% of Medicare hospital fee-for-service payments to quality or value by 2016, and that percentage could increase to 90% by 2018. The January announcement was the first time in Medicare’s history that explicit goals for alternative payment models and value-based payments were set, according to an announcement from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

“Strategically, these things are essential to work into the plan of what the hospital medicine group is doing in the coming three to five years,” Dr. Whitcomb said. “Hospitalists can’t do this alone. They have to do it with teams. It’s not only teams of other professionals in the hospital and around the hospital, but it’s other physicians.”

Dr. Whitcomb said key to the new paradigm is shared financial and clinical responsibilities. He says hospitalists have to “change our thinking…to a mindset where we’re in this together.”

Part of that shared responsibility extends to the post-acute care setting, where SHM senior vice president for practice management Joseph Miller said that some 30% of HMGs are practicing. To help those practitioners, SHM and IPC Healthcare of North Hollywood, Calif., debuted the “Primer for Hospitalists on Skilled Nursing Facilities” at HM15.

The educational program, housed at SHM’s Learning Portal, has 32 lessons meant to differentiate the traditional acute-care hospital from post-acute care facilities. It is grouped in five sections and two modules, with a focus on skilled-nursing facilities (SNFs), which are the most common post-acute care settings.

“The types of resources that are available are different, and that’s not only in terms of staff, but the availability of specialists, the availability of testing capabilities,” Miller said. “If you need to work with a cardiologist for a particular patient...how do you engage them? You’re not going to be able to have them come and see that patient frequently. How do you communicate with them to get the feedback you need as the attending physician?”

Another communication hassle involves the growing number of HMGs spread over multiple sites. For Sara Shraibman, MD, an assistant program director at Syosset Hospital in Syosset, N.Y., those sites are two hospitals covered by the North Shore LIJ Medical Group.

“It’s actually a new program, so we are trying to look at our compensation, models comparing them across two hospitals…and how we manage,” she said. “Not every hospitalist will go back and forth. Some will, some won’t. Some will work nights to help cover, some won’t. It’s very interesting trying to come up with a schedule.”

The best way to address conflict at multi-site groups is communicating and focusing on shared goals, said David Weidig, MD, director of hospital medicine for Aurora Medical Group in West Allis, Wis., and a new member of Team Hospitalist.

“Make sure that no matter what conflict might be up front, that everybody is looking at the goals downstream and saying, ‘Yes, that is a goal we want to achieve. We want to have better patient safety metrics. We want to have decreased readmissions. We want to have better transitions of care,’” Dr. Weidig said. “The common goal all the way from hospital administrators all the way down to hospital physicians is going to be the key.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

HM15 Speakers Urge Hospitalists to Use Technology, Teamwork, Talent

NATIONAL HARBOR, Md.—In the convention business, some say an annual meeting is only as good as its keynote addresses. Those people would call HM15 a home run, because the thousands of hospitalists who made their way to just outside the nation’s capital last month were treated to a trinity of talented talkers.

First up was patient safety guru Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, FCCM, senior vice president for patient safety and quality at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore. Maureen Bisognano, president and CEO of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), echoed his patient-centered focus in her address. The four-day confab ended with hospitalist dean Bob Wachter, MD, MHM, reading from his new book, “The Digital Doctor: Hope, Hype, and Harm at the Dawn of Medicine’s Computer Age.”

The three came from different perspectives but ended up in the same place: Hospitalists can use technology, teamwork, and talent to be the people who make healthcare in this country safer. In fact, HM has the responsibility to do so.

“We are the only hope that the healthcare system has of improving quality and safety,” Dr. Pronovost said.

Famous for creating a five-step checklist designed to reduce the incidence of central line-associated infections, he talked about healthcare in terms of physicians telling “depressing” stories that hold change back.

“The first is that we still tell a story that harm is inevitable,” he said. “‘You’re sick, you’re old, you’re young, stuff happens.’ Second, we still tell stories that [show that] safety and quality are based on the heroism of our clinicians rather than design of safe systems. And, third, we still tell a story that ‘I am powerless to do anything about it.’

“We need some new stories.”

Reframing the discussion of healthcare into a story of preventing all harm is ambitious but doable, he added. Hospitalists need to team with others, though, because an overhauled healthcare system needs buy-in from all physicians.

“The trick of this is to have enough details that people want to join you, but don’t completely tell the story, because others have to co-create it with you,” Dr. Pronovost said. “You tell the why and the what, but the how is co-created by all of your colleagues who are working with you.”

Bisognano says hospitalists can help hospitalists achieve IHI’s Triple Aim, an initiative to simultaneously improve the patient experience and the health of populations, reducing the per capita cost of healthcare. But, like Dr. Pronovost, her argument is based on a new view of the healthcare system.

“We need not a system that says, ‘What’s the matter?’ but a system that understands deeply what matters to each patient,” Bisognano said.

That prism requires speaking a new “language,” one that uses quality of care delivered and defines it more broadly than simply mortality rates and adverse events.

“You can look at health and care, but you also can drive out unnecessary cost,” she said. “And being a former hospital CEO, I can say it was magic when a clinician could walk in and be able to talk in both languages.”

Dr. Wachter spoke of the past, present, and future of the digital age of medicine. He is as frustrated by poor electronic health record (EHR) rollouts as front-line hospitalists but notes that healthcare in the past five years has seen a digital revolution in a much shorter time period than most industries, thanks to federal incentives.

“Most fields that go digital do so over the course of 10 or 20 years, in a very organic way, with the early adopters, the rank and file, and then the laggards,” he said. “And in that kind of organic adoption curve, you see problems arise, and people begin to deal with them and understand them and mitigate them.

“What the federal intervention did was essentially turbocharge the digitization of healthcare. We’ve seen this in a very telescoped way. … It’s like we got started on a huge dose of chemo, stat.”

Moving forward, Dr. Wachter said the focus has to be on improving the use and integration of healthcare to ensure that it translates to better patient care. For example, going to digital radiology has in many ways ended the daily meetings that once were commonplace in hospital “film rooms.” In essence, the move from “analog to digital” meant people communicated less. Now, multidisciplinary rounds and other unit-based approaches are trying to recreate teamwork.

“Places are doing some pretty impressive things to try to bring teams back together in a digital environment,” Dr. Wachter said. “But, the point is, I didn’t give this any thought. I don’t know whether you did. What didn’t cross my own cognitive radar screen was that when we go digital, we will screw up the relationships, because people can now be wherever they want to be to do their work.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

NATIONAL HARBOR, Md.—In the convention business, some say an annual meeting is only as good as its keynote addresses. Those people would call HM15 a home run, because the thousands of hospitalists who made their way to just outside the nation’s capital last month were treated to a trinity of talented talkers.

First up was patient safety guru Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, FCCM, senior vice president for patient safety and quality at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore. Maureen Bisognano, president and CEO of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), echoed his patient-centered focus in her address. The four-day confab ended with hospitalist dean Bob Wachter, MD, MHM, reading from his new book, “The Digital Doctor: Hope, Hype, and Harm at the Dawn of Medicine’s Computer Age.”

The three came from different perspectives but ended up in the same place: Hospitalists can use technology, teamwork, and talent to be the people who make healthcare in this country safer. In fact, HM has the responsibility to do so.

“We are the only hope that the healthcare system has of improving quality and safety,” Dr. Pronovost said.

Famous for creating a five-step checklist designed to reduce the incidence of central line-associated infections, he talked about healthcare in terms of physicians telling “depressing” stories that hold change back.

“The first is that we still tell a story that harm is inevitable,” he said. “‘You’re sick, you’re old, you’re young, stuff happens.’ Second, we still tell stories that [show that] safety and quality are based on the heroism of our clinicians rather than design of safe systems. And, third, we still tell a story that ‘I am powerless to do anything about it.’

“We need some new stories.”

Reframing the discussion of healthcare into a story of preventing all harm is ambitious but doable, he added. Hospitalists need to team with others, though, because an overhauled healthcare system needs buy-in from all physicians.

“The trick of this is to have enough details that people want to join you, but don’t completely tell the story, because others have to co-create it with you,” Dr. Pronovost said. “You tell the why and the what, but the how is co-created by all of your colleagues who are working with you.”

Bisognano says hospitalists can help hospitalists achieve IHI’s Triple Aim, an initiative to simultaneously improve the patient experience and the health of populations, reducing the per capita cost of healthcare. But, like Dr. Pronovost, her argument is based on a new view of the healthcare system.

“We need not a system that says, ‘What’s the matter?’ but a system that understands deeply what matters to each patient,” Bisognano said.

That prism requires speaking a new “language,” one that uses quality of care delivered and defines it more broadly than simply mortality rates and adverse events.

“You can look at health and care, but you also can drive out unnecessary cost,” she said. “And being a former hospital CEO, I can say it was magic when a clinician could walk in and be able to talk in both languages.”

Dr. Wachter spoke of the past, present, and future of the digital age of medicine. He is as frustrated by poor electronic health record (EHR) rollouts as front-line hospitalists but notes that healthcare in the past five years has seen a digital revolution in a much shorter time period than most industries, thanks to federal incentives.

“Most fields that go digital do so over the course of 10 or 20 years, in a very organic way, with the early adopters, the rank and file, and then the laggards,” he said. “And in that kind of organic adoption curve, you see problems arise, and people begin to deal with them and understand them and mitigate them.

“What the federal intervention did was essentially turbocharge the digitization of healthcare. We’ve seen this in a very telescoped way. … It’s like we got started on a huge dose of chemo, stat.”

Moving forward, Dr. Wachter said the focus has to be on improving the use and integration of healthcare to ensure that it translates to better patient care. For example, going to digital radiology has in many ways ended the daily meetings that once were commonplace in hospital “film rooms.” In essence, the move from “analog to digital” meant people communicated less. Now, multidisciplinary rounds and other unit-based approaches are trying to recreate teamwork.

“Places are doing some pretty impressive things to try to bring teams back together in a digital environment,” Dr. Wachter said. “But, the point is, I didn’t give this any thought. I don’t know whether you did. What didn’t cross my own cognitive radar screen was that when we go digital, we will screw up the relationships, because people can now be wherever they want to be to do their work.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

NATIONAL HARBOR, Md.—In the convention business, some say an annual meeting is only as good as its keynote addresses. Those people would call HM15 a home run, because the thousands of hospitalists who made their way to just outside the nation’s capital last month were treated to a trinity of talented talkers.

First up was patient safety guru Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, FCCM, senior vice president for patient safety and quality at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore. Maureen Bisognano, president and CEO of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), echoed his patient-centered focus in her address. The four-day confab ended with hospitalist dean Bob Wachter, MD, MHM, reading from his new book, “The Digital Doctor: Hope, Hype, and Harm at the Dawn of Medicine’s Computer Age.”

The three came from different perspectives but ended up in the same place: Hospitalists can use technology, teamwork, and talent to be the people who make healthcare in this country safer. In fact, HM has the responsibility to do so.

“We are the only hope that the healthcare system has of improving quality and safety,” Dr. Pronovost said.

Famous for creating a five-step checklist designed to reduce the incidence of central line-associated infections, he talked about healthcare in terms of physicians telling “depressing” stories that hold change back.

“The first is that we still tell a story that harm is inevitable,” he said. “‘You’re sick, you’re old, you’re young, stuff happens.’ Second, we still tell stories that [show that] safety and quality are based on the heroism of our clinicians rather than design of safe systems. And, third, we still tell a story that ‘I am powerless to do anything about it.’

“We need some new stories.”

Reframing the discussion of healthcare into a story of preventing all harm is ambitious but doable, he added. Hospitalists need to team with others, though, because an overhauled healthcare system needs buy-in from all physicians.

“The trick of this is to have enough details that people want to join you, but don’t completely tell the story, because others have to co-create it with you,” Dr. Pronovost said. “You tell the why and the what, but the how is co-created by all of your colleagues who are working with you.”

Bisognano says hospitalists can help hospitalists achieve IHI’s Triple Aim, an initiative to simultaneously improve the patient experience and the health of populations, reducing the per capita cost of healthcare. But, like Dr. Pronovost, her argument is based on a new view of the healthcare system.

“We need not a system that says, ‘What’s the matter?’ but a system that understands deeply what matters to each patient,” Bisognano said.

That prism requires speaking a new “language,” one that uses quality of care delivered and defines it more broadly than simply mortality rates and adverse events.

“You can look at health and care, but you also can drive out unnecessary cost,” she said. “And being a former hospital CEO, I can say it was magic when a clinician could walk in and be able to talk in both languages.”

Dr. Wachter spoke of the past, present, and future of the digital age of medicine. He is as frustrated by poor electronic health record (EHR) rollouts as front-line hospitalists but notes that healthcare in the past five years has seen a digital revolution in a much shorter time period than most industries, thanks to federal incentives.

“Most fields that go digital do so over the course of 10 or 20 years, in a very organic way, with the early adopters, the rank and file, and then the laggards,” he said. “And in that kind of organic adoption curve, you see problems arise, and people begin to deal with them and understand them and mitigate them.

“What the federal intervention did was essentially turbocharge the digitization of healthcare. We’ve seen this in a very telescoped way. … It’s like we got started on a huge dose of chemo, stat.”

Moving forward, Dr. Wachter said the focus has to be on improving the use and integration of healthcare to ensure that it translates to better patient care. For example, going to digital radiology has in many ways ended the daily meetings that once were commonplace in hospital “film rooms.” In essence, the move from “analog to digital” meant people communicated less. Now, multidisciplinary rounds and other unit-based approaches are trying to recreate teamwork.

“Places are doing some pretty impressive things to try to bring teams back together in a digital environment,” Dr. Wachter said. “But, the point is, I didn’t give this any thought. I don’t know whether you did. What didn’t cross my own cognitive radar screen was that when we go digital, we will screw up the relationships, because people can now be wherever they want to be to do their work.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Family Medicine’s Increasing Presence in Hospital Medicine

Years ago, I struggled with a difficult decision. Given the fact that the military disallowed dual training tracks, such as internal medicine/pediatrics (med/peds), I had to choose from internal medicine (IM), pediatrics (Peds), or family practice (FP) residencies. My personal history and experiential data remained incomplete and the view ahead blurry; still, the choice remained.

Over time, I’ve embraced the uncertainty inherent in most analyses. Such is the case with the current composition of specialties that make up hospital medicine nationwide. Available data remains in flux, yet I see apparent trends.

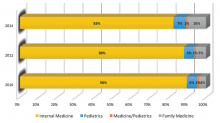

A new question in the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) report asked, “Did your hospital medicine group employ hospitalist physicians trained and certified in the following specialties…?” Strikingly, a full 59% of groups serving adult patients only reported having at least one family medicine-trained provider in their midst! And in these adult-only practices, 98% of groups utilized at least one internal medicine physician, 24% reported a med/peds doc, and none reported pediatricians.

Meanwhile, of 40 groups caring for children only, 95% reported using pediatrics, 2.5% internal medicine (huh?), 22.5% med/peds, and zero FPs. The 19 groups serving both adults and children revealed participation from all four nonsurgical hospitalist specialties (IM, peds, FP, med/peds).

So what is the specialty distribution of medical hospitalists overall? There’s no good data about this.

The 2014 Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) sample, licensed for use in SOHM, reported data for roughly 4,200 community hospital medicine providers: 82% were internal medicine, 10% family medicine, 7% pediatrics, and <1% med/peds. MGMA, however, cautions against assuming that this represents the entire population of hospitalists and their training. Although representative of the groups who participated in the survey, it may not be representative of groups that didn’t participate, and thus it would be misleading to suggest that this distribution holds true nationally.

In an effort to corroborate the MGMA distribution, I reviewed other compensation and productivity surveys; one such survey, conducted by the American Medical Group Association, reported hospitalists by training program. It contained over 3,700 community hospital providers—89% internal medicine, 6% family medicine, 5% pediatrics—but did not inquire about medicine/pediatrics.

Finally, if one combines the academic and community provider samples from MGMA (n=4,867), the distribution is 80% IM, 8.5% FP, 10% peds, and <1% med/peds.

Which of these, if any, is the actual distribution of nonprocedural hospitalists? Although we cannot know exactly, I believe something close to the following to be current state: internal medicine 80%, family medicine 10%, pediatrics 10%, and medicine/pediatrics <1%.

It is clear from survey trends that the proportion of family medicine providers is growing, while the internal medicine super-majority is shrinking somewhat. Pediatrics appears to remain stable as a proportion of the total, as does med/peds, with the latter unable to grow in numbers proportionally given the small number of providers nationally compared to the other three fields.

The growth of family medicine-trained hospitalists relates to the continued high demand for the profession, with such residents comprising the largest pool of available providers, second only to internal medicine.

Based on the SHM survey, family medicine hospitalists seem to practice similarly to IM; they generally see adults only. It appears that they are accepted into traditional adult hospitalist practices, readily contrasting with groups serving children, which report no FP participation. Meanwhile, med/peds hospitalists provide care across the spectrum of hospitalist groups, though they often report splitting their duties between adults-only services and pediatric services.

As for me, a generation removed from my election of a family practice internship and subsequent transition to internal medicine residency, I should not have worried so. Both paths can lead to hospital medicine.

Dr. Ahlstrom is a hospitalist at Indigo Health Partners in Traverse City, Mich., and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Years ago, I struggled with a difficult decision. Given the fact that the military disallowed dual training tracks, such as internal medicine/pediatrics (med/peds), I had to choose from internal medicine (IM), pediatrics (Peds), or family practice (FP) residencies. My personal history and experiential data remained incomplete and the view ahead blurry; still, the choice remained.

Over time, I’ve embraced the uncertainty inherent in most analyses. Such is the case with the current composition of specialties that make up hospital medicine nationwide. Available data remains in flux, yet I see apparent trends.

A new question in the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) report asked, “Did your hospital medicine group employ hospitalist physicians trained and certified in the following specialties…?” Strikingly, a full 59% of groups serving adult patients only reported having at least one family medicine-trained provider in their midst! And in these adult-only practices, 98% of groups utilized at least one internal medicine physician, 24% reported a med/peds doc, and none reported pediatricians.

Meanwhile, of 40 groups caring for children only, 95% reported using pediatrics, 2.5% internal medicine (huh?), 22.5% med/peds, and zero FPs. The 19 groups serving both adults and children revealed participation from all four nonsurgical hospitalist specialties (IM, peds, FP, med/peds).

So what is the specialty distribution of medical hospitalists overall? There’s no good data about this.

The 2014 Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) sample, licensed for use in SOHM, reported data for roughly 4,200 community hospital medicine providers: 82% were internal medicine, 10% family medicine, 7% pediatrics, and <1% med/peds. MGMA, however, cautions against assuming that this represents the entire population of hospitalists and their training. Although representative of the groups who participated in the survey, it may not be representative of groups that didn’t participate, and thus it would be misleading to suggest that this distribution holds true nationally.

In an effort to corroborate the MGMA distribution, I reviewed other compensation and productivity surveys; one such survey, conducted by the American Medical Group Association, reported hospitalists by training program. It contained over 3,700 community hospital providers—89% internal medicine, 6% family medicine, 5% pediatrics—but did not inquire about medicine/pediatrics.

Finally, if one combines the academic and community provider samples from MGMA (n=4,867), the distribution is 80% IM, 8.5% FP, 10% peds, and <1% med/peds.

Which of these, if any, is the actual distribution of nonprocedural hospitalists? Although we cannot know exactly, I believe something close to the following to be current state: internal medicine 80%, family medicine 10%, pediatrics 10%, and medicine/pediatrics <1%.

It is clear from survey trends that the proportion of family medicine providers is growing, while the internal medicine super-majority is shrinking somewhat. Pediatrics appears to remain stable as a proportion of the total, as does med/peds, with the latter unable to grow in numbers proportionally given the small number of providers nationally compared to the other three fields.

The growth of family medicine-trained hospitalists relates to the continued high demand for the profession, with such residents comprising the largest pool of available providers, second only to internal medicine.

Based on the SHM survey, family medicine hospitalists seem to practice similarly to IM; they generally see adults only. It appears that they are accepted into traditional adult hospitalist practices, readily contrasting with groups serving children, which report no FP participation. Meanwhile, med/peds hospitalists provide care across the spectrum of hospitalist groups, though they often report splitting their duties between adults-only services and pediatric services.

As for me, a generation removed from my election of a family practice internship and subsequent transition to internal medicine residency, I should not have worried so. Both paths can lead to hospital medicine.

Dr. Ahlstrom is a hospitalist at Indigo Health Partners in Traverse City, Mich., and a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Years ago, I struggled with a difficult decision. Given the fact that the military disallowed dual training tracks, such as internal medicine/pediatrics (med/peds), I had to choose from internal medicine (IM), pediatrics (Peds), or family practice (FP) residencies. My personal history and experiential data remained incomplete and the view ahead blurry; still, the choice remained.

Over time, I’ve embraced the uncertainty inherent in most analyses. Such is the case with the current composition of specialties that make up hospital medicine nationwide. Available data remains in flux, yet I see apparent trends.

A new question in the 2014 State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) report asked, “Did your hospital medicine group employ hospitalist physicians trained and certified in the following specialties…?” Strikingly, a full 59% of groups serving adult patients only reported having at least one family medicine-trained provider in their midst! And in these adult-only practices, 98% of groups utilized at least one internal medicine physician, 24% reported a med/peds doc, and none reported pediatricians.

Meanwhile, of 40 groups caring for children only, 95% reported using pediatrics, 2.5% internal medicine (huh?), 22.5% med/peds, and zero FPs. The 19 groups serving both adults and children revealed participation from all four nonsurgical hospitalist specialties (IM, peds, FP, med/peds).

So what is the specialty distribution of medical hospitalists overall? There’s no good data about this.