User login

A New View for the VA

In June 2015, David J. Shulkin, MD was sworn in as VA Under Secretary of Health—a position that had been empty for more than a year following the resignation of Robert Petzel, MD, in the wake of the Phoenix wait-time controversy. Carolyn M. Clancy, MD, had filled the position on an interim basis. Federal Practitioner recently sat down with Dr. Shulkin to discuss his plans for improving both health care quality and employee morale across the VA, which has been sapped by the recent scandals.

Building a New Health Care System

VA Under Secretary of Health David J. Shulkin, MD.I think there is an overlap between the design of a new health care system and having high levels of staff satisfaction. To me, it starts with being able to provide your employees, physicians, and staff with the types of tools and resources that they need to be able to take care of patients and a work environment that allows them to feel that they can practice to the best of their professional levels.

When I go around to visit VA facilities across the country, I see tremendous variation. I see some facilities that have invested in great programs, so their staff feels like they are practicing in world class facilities. And I see other places [where] it looks like they’re practicing 30 years ago.

The plan that we’ve put forth proposes that we invest our resources in a way that allows everyone who works in the VA to feel like they are working in a world class center. But that also means that we won’t be able to do everything for everybody. When you make investments, it means that you’re going to invest in one place and not everywhere. So there are some things that the VA may actually no longer do.

However, our plan allows us to develop the types of facilities where people will want to work and continue to want to work, by leveraging what already exists that’s being done well in the private community.

Applying Best Practices to the VA

Dr. Shulkin. Implementing best practices is not the same to me as standardizing everything. I think that all you have to do as a physician is reflect back upon medical school. Almost everything I learned in medical school is no longer relevant and none of the drugs. So there is a recognition that in order to be good at something, you need to be continually challenging the evidence that you have and the beliefs that you have and learning and improving and evolving and innovating. So implementing best practices, to me, is not stifling innovation or stifling experimentation. What it says is that if you have an organization as big as ours and somebody is doing something well, others should be learning from it and adopting it.

The example I point to is James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital in Tampa, Florida. They’re doing same-day access primary care. They have no wait times. That’s our issue, wait times, and here’s a place that has no wait times. And the staff love it and the patients love it.

Why isn’t every VA doing that? I can’t think of a reason. It doesn’t mean they’re going to have to do it exactly the same way, and it doesn’t mean 5 years from now there won’t be a different way of having patients get appointments and access to care. But today, that’s the best practice that I can see, and I want every VA doing that.

Bringing an Outside Perspective

Dr. Shulkin. There were times when having an outside person come in to be Under Secretary would have been a challenge. But I think right now, given where the VA is, there is a recognition that having outside eyes is a good thing. Within the VA, there is a thirst for understanding how problems are solved in the private sector, and there is a real openness to new ideas. I think this comes from a recognition that it doesn’t feel good to be working as hard as I know most VA professionals are and continuing to see themselves bashed in the press

So people are open to new ideas, and they want to get beyond where we are. Having outside eyes on this is seen, today, as a good thing. But it needs to be done carefully and in a way that respects the things that have made the VA great, the good parts of the culture, and the hard work of the professionals who are caring for veterans every day. This can’t be a message of changing everything in the VA because, clearly, there are lots of things that are working really well. But there are areas where we can benefit from perspectives outside of the VA, and that’s what I’m trying to bring to the organization.

Increased Hiring Within the VA

Dr. Shulkin. A large part of the Veterans Choice Act funds that were authorized in 2014 were targeted toward new hires. The VA has hired a net increase of 14,000 employees. I think there were 1,600 net new physicians and 3,500 net new nurses. We’ve hired professionals in almost every part of the organization, including homeless coordinators, social workers, and pharmacists. You’ve seen hiring across the board. I think that you will continue to see that, but it will be more targeted toward areas we’ve identified that will impact access the most and where the shortages are the greatest.

Primary care doctors and psychiatrists will be 2 areas where there will be targeted hiring, and there are specialty areas that, depending on the geography, that will be targeted for hiring as well. Depending upon what our budget looks like, which we still don’t yet know for 2016, 2017, and 2018, we will see how much additional flexibility may be there for hiring.

Cost vs Quality of Care Debate: Lessons Learned From Hepatitis C Care

Dr. Shulkin. I think the challenge and the lessons that we’re trying to learn from the hepatitis C example was that when we put our 2015 budget together, we didn’t even know that new hepatitis C drug [cures] existed. We were looking at the older version—the interferons, which of course, weren’t curative in the same way. By the time that our budget actually hit, there was a new drug that offered new hope. Frankly, for the VA, that amounted to about a billion dollars in unfunded monies, because we didn’t know about the drug when we put that budget together. So that is a challenge for us.

Having said that, I’m very proud of the way that VA responded by moving money around to make sure that veterans got the right care. Nobody in this country has treated more veterans with hepatitis C than the VA. Nobody even comes close. More than 35,000 veterans received treatment for hepatitis C that’s curative in 2015. Nobody does it by addressing disparities in health care the way the VA does. We reach out to those that are in most need. Those with the mental health issues. Those that are essentially socially isolated. We’re calling them and bringing them in. No other health system does this. The VA has actually shown why it’s a great organization in responding this way. 2016 and beyond, we are committed to trying to find ways to do that. We will work with our ethics people, our hepatologists, our policy people, Congress, and drug makers to make sure that we can do the best we can for veterans.

Providing Long-term, Quality Care While Offering Options to Veterans

Dr. Shulkin.The VA is not a voucher program. This is not sending people out into the community to find their own care. VA health care is a well-integrated coordinated plan for people who we feel a responsibility for, for life. They are going to be VA patients as long as they want to be VA patients. But this is our responsibility, so that when they go out into the community, their care needs to be coordinated and tied back into VA health care. It can’t be seen as a separate health care system or a fragmented health care system.

That’s the problem that we’ve learned in health care, both in the VA and outside the VA. When you fragment care, when you separate care, that’s where you find quality problems and gaps in care that lead to people missing necessary testing or treatments that they need.

We deliberately designed Veterans’ Choice to address these issues, because these are our patients and our responsibility. When they go into the community, it doesn’t mean they leave VA. It means they’re getting care in the community as part of the VA health care system.

In June 2015, David J. Shulkin, MD was sworn in as VA Under Secretary of Health—a position that had been empty for more than a year following the resignation of Robert Petzel, MD, in the wake of the Phoenix wait-time controversy. Carolyn M. Clancy, MD, had filled the position on an interim basis. Federal Practitioner recently sat down with Dr. Shulkin to discuss his plans for improving both health care quality and employee morale across the VA, which has been sapped by the recent scandals.

Building a New Health Care System

VA Under Secretary of Health David J. Shulkin, MD.I think there is an overlap between the design of a new health care system and having high levels of staff satisfaction. To me, it starts with being able to provide your employees, physicians, and staff with the types of tools and resources that they need to be able to take care of patients and a work environment that allows them to feel that they can practice to the best of their professional levels.

When I go around to visit VA facilities across the country, I see tremendous variation. I see some facilities that have invested in great programs, so their staff feels like they are practicing in world class facilities. And I see other places [where] it looks like they’re practicing 30 years ago.

The plan that we’ve put forth proposes that we invest our resources in a way that allows everyone who works in the VA to feel like they are working in a world class center. But that also means that we won’t be able to do everything for everybody. When you make investments, it means that you’re going to invest in one place and not everywhere. So there are some things that the VA may actually no longer do.

However, our plan allows us to develop the types of facilities where people will want to work and continue to want to work, by leveraging what already exists that’s being done well in the private community.

Applying Best Practices to the VA

Dr. Shulkin. Implementing best practices is not the same to me as standardizing everything. I think that all you have to do as a physician is reflect back upon medical school. Almost everything I learned in medical school is no longer relevant and none of the drugs. So there is a recognition that in order to be good at something, you need to be continually challenging the evidence that you have and the beliefs that you have and learning and improving and evolving and innovating. So implementing best practices, to me, is not stifling innovation or stifling experimentation. What it says is that if you have an organization as big as ours and somebody is doing something well, others should be learning from it and adopting it.

The example I point to is James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital in Tampa, Florida. They’re doing same-day access primary care. They have no wait times. That’s our issue, wait times, and here’s a place that has no wait times. And the staff love it and the patients love it.

Why isn’t every VA doing that? I can’t think of a reason. It doesn’t mean they’re going to have to do it exactly the same way, and it doesn’t mean 5 years from now there won’t be a different way of having patients get appointments and access to care. But today, that’s the best practice that I can see, and I want every VA doing that.

Bringing an Outside Perspective

Dr. Shulkin. There were times when having an outside person come in to be Under Secretary would have been a challenge. But I think right now, given where the VA is, there is a recognition that having outside eyes is a good thing. Within the VA, there is a thirst for understanding how problems are solved in the private sector, and there is a real openness to new ideas. I think this comes from a recognition that it doesn’t feel good to be working as hard as I know most VA professionals are and continuing to see themselves bashed in the press

So people are open to new ideas, and they want to get beyond where we are. Having outside eyes on this is seen, today, as a good thing. But it needs to be done carefully and in a way that respects the things that have made the VA great, the good parts of the culture, and the hard work of the professionals who are caring for veterans every day. This can’t be a message of changing everything in the VA because, clearly, there are lots of things that are working really well. But there are areas where we can benefit from perspectives outside of the VA, and that’s what I’m trying to bring to the organization.

Increased Hiring Within the VA

Dr. Shulkin. A large part of the Veterans Choice Act funds that were authorized in 2014 were targeted toward new hires. The VA has hired a net increase of 14,000 employees. I think there were 1,600 net new physicians and 3,500 net new nurses. We’ve hired professionals in almost every part of the organization, including homeless coordinators, social workers, and pharmacists. You’ve seen hiring across the board. I think that you will continue to see that, but it will be more targeted toward areas we’ve identified that will impact access the most and where the shortages are the greatest.

Primary care doctors and psychiatrists will be 2 areas where there will be targeted hiring, and there are specialty areas that, depending on the geography, that will be targeted for hiring as well. Depending upon what our budget looks like, which we still don’t yet know for 2016, 2017, and 2018, we will see how much additional flexibility may be there for hiring.

Cost vs Quality of Care Debate: Lessons Learned From Hepatitis C Care

Dr. Shulkin. I think the challenge and the lessons that we’re trying to learn from the hepatitis C example was that when we put our 2015 budget together, we didn’t even know that new hepatitis C drug [cures] existed. We were looking at the older version—the interferons, which of course, weren’t curative in the same way. By the time that our budget actually hit, there was a new drug that offered new hope. Frankly, for the VA, that amounted to about a billion dollars in unfunded monies, because we didn’t know about the drug when we put that budget together. So that is a challenge for us.

Having said that, I’m very proud of the way that VA responded by moving money around to make sure that veterans got the right care. Nobody in this country has treated more veterans with hepatitis C than the VA. Nobody even comes close. More than 35,000 veterans received treatment for hepatitis C that’s curative in 2015. Nobody does it by addressing disparities in health care the way the VA does. We reach out to those that are in most need. Those with the mental health issues. Those that are essentially socially isolated. We’re calling them and bringing them in. No other health system does this. The VA has actually shown why it’s a great organization in responding this way. 2016 and beyond, we are committed to trying to find ways to do that. We will work with our ethics people, our hepatologists, our policy people, Congress, and drug makers to make sure that we can do the best we can for veterans.

Providing Long-term, Quality Care While Offering Options to Veterans

Dr. Shulkin.The VA is not a voucher program. This is not sending people out into the community to find their own care. VA health care is a well-integrated coordinated plan for people who we feel a responsibility for, for life. They are going to be VA patients as long as they want to be VA patients. But this is our responsibility, so that when they go out into the community, their care needs to be coordinated and tied back into VA health care. It can’t be seen as a separate health care system or a fragmented health care system.

That’s the problem that we’ve learned in health care, both in the VA and outside the VA. When you fragment care, when you separate care, that’s where you find quality problems and gaps in care that lead to people missing necessary testing or treatments that they need.

We deliberately designed Veterans’ Choice to address these issues, because these are our patients and our responsibility. When they go into the community, it doesn’t mean they leave VA. It means they’re getting care in the community as part of the VA health care system.

In June 2015, David J. Shulkin, MD was sworn in as VA Under Secretary of Health—a position that had been empty for more than a year following the resignation of Robert Petzel, MD, in the wake of the Phoenix wait-time controversy. Carolyn M. Clancy, MD, had filled the position on an interim basis. Federal Practitioner recently sat down with Dr. Shulkin to discuss his plans for improving both health care quality and employee morale across the VA, which has been sapped by the recent scandals.

Building a New Health Care System

VA Under Secretary of Health David J. Shulkin, MD.I think there is an overlap between the design of a new health care system and having high levels of staff satisfaction. To me, it starts with being able to provide your employees, physicians, and staff with the types of tools and resources that they need to be able to take care of patients and a work environment that allows them to feel that they can practice to the best of their professional levels.

When I go around to visit VA facilities across the country, I see tremendous variation. I see some facilities that have invested in great programs, so their staff feels like they are practicing in world class facilities. And I see other places [where] it looks like they’re practicing 30 years ago.

The plan that we’ve put forth proposes that we invest our resources in a way that allows everyone who works in the VA to feel like they are working in a world class center. But that also means that we won’t be able to do everything for everybody. When you make investments, it means that you’re going to invest in one place and not everywhere. So there are some things that the VA may actually no longer do.

However, our plan allows us to develop the types of facilities where people will want to work and continue to want to work, by leveraging what already exists that’s being done well in the private community.

Applying Best Practices to the VA

Dr. Shulkin. Implementing best practices is not the same to me as standardizing everything. I think that all you have to do as a physician is reflect back upon medical school. Almost everything I learned in medical school is no longer relevant and none of the drugs. So there is a recognition that in order to be good at something, you need to be continually challenging the evidence that you have and the beliefs that you have and learning and improving and evolving and innovating. So implementing best practices, to me, is not stifling innovation or stifling experimentation. What it says is that if you have an organization as big as ours and somebody is doing something well, others should be learning from it and adopting it.

The example I point to is James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital in Tampa, Florida. They’re doing same-day access primary care. They have no wait times. That’s our issue, wait times, and here’s a place that has no wait times. And the staff love it and the patients love it.

Why isn’t every VA doing that? I can’t think of a reason. It doesn’t mean they’re going to have to do it exactly the same way, and it doesn’t mean 5 years from now there won’t be a different way of having patients get appointments and access to care. But today, that’s the best practice that I can see, and I want every VA doing that.

Bringing an Outside Perspective

Dr. Shulkin. There were times when having an outside person come in to be Under Secretary would have been a challenge. But I think right now, given where the VA is, there is a recognition that having outside eyes is a good thing. Within the VA, there is a thirst for understanding how problems are solved in the private sector, and there is a real openness to new ideas. I think this comes from a recognition that it doesn’t feel good to be working as hard as I know most VA professionals are and continuing to see themselves bashed in the press

So people are open to new ideas, and they want to get beyond where we are. Having outside eyes on this is seen, today, as a good thing. But it needs to be done carefully and in a way that respects the things that have made the VA great, the good parts of the culture, and the hard work of the professionals who are caring for veterans every day. This can’t be a message of changing everything in the VA because, clearly, there are lots of things that are working really well. But there are areas where we can benefit from perspectives outside of the VA, and that’s what I’m trying to bring to the organization.

Increased Hiring Within the VA

Dr. Shulkin. A large part of the Veterans Choice Act funds that were authorized in 2014 were targeted toward new hires. The VA has hired a net increase of 14,000 employees. I think there were 1,600 net new physicians and 3,500 net new nurses. We’ve hired professionals in almost every part of the organization, including homeless coordinators, social workers, and pharmacists. You’ve seen hiring across the board. I think that you will continue to see that, but it will be more targeted toward areas we’ve identified that will impact access the most and where the shortages are the greatest.

Primary care doctors and psychiatrists will be 2 areas where there will be targeted hiring, and there are specialty areas that, depending on the geography, that will be targeted for hiring as well. Depending upon what our budget looks like, which we still don’t yet know for 2016, 2017, and 2018, we will see how much additional flexibility may be there for hiring.

Cost vs Quality of Care Debate: Lessons Learned From Hepatitis C Care

Dr. Shulkin. I think the challenge and the lessons that we’re trying to learn from the hepatitis C example was that when we put our 2015 budget together, we didn’t even know that new hepatitis C drug [cures] existed. We were looking at the older version—the interferons, which of course, weren’t curative in the same way. By the time that our budget actually hit, there was a new drug that offered new hope. Frankly, for the VA, that amounted to about a billion dollars in unfunded monies, because we didn’t know about the drug when we put that budget together. So that is a challenge for us.

Having said that, I’m very proud of the way that VA responded by moving money around to make sure that veterans got the right care. Nobody in this country has treated more veterans with hepatitis C than the VA. Nobody even comes close. More than 35,000 veterans received treatment for hepatitis C that’s curative in 2015. Nobody does it by addressing disparities in health care the way the VA does. We reach out to those that are in most need. Those with the mental health issues. Those that are essentially socially isolated. We’re calling them and bringing them in. No other health system does this. The VA has actually shown why it’s a great organization in responding this way. 2016 and beyond, we are committed to trying to find ways to do that. We will work with our ethics people, our hepatologists, our policy people, Congress, and drug makers to make sure that we can do the best we can for veterans.

Providing Long-term, Quality Care While Offering Options to Veterans

Dr. Shulkin.The VA is not a voucher program. This is not sending people out into the community to find their own care. VA health care is a well-integrated coordinated plan for people who we feel a responsibility for, for life. They are going to be VA patients as long as they want to be VA patients. But this is our responsibility, so that when they go out into the community, their care needs to be coordinated and tied back into VA health care. It can’t be seen as a separate health care system or a fragmented health care system.

That’s the problem that we’ve learned in health care, both in the VA and outside the VA. When you fragment care, when you separate care, that’s where you find quality problems and gaps in care that lead to people missing necessary testing or treatments that they need.

We deliberately designed Veterans’ Choice to address these issues, because these are our patients and our responsibility. When they go into the community, it doesn’t mean they leave VA. It means they’re getting care in the community as part of the VA health care system.

Managing Diabetes in Women of Childbearing Age

There were 13.4 million women (ages 20 and older) with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes in the United States in 2012, according to the CDC.1 By 2050, overall prevalence of diabetes is expected to double or triple.2 Since the number of women with diabetes will continue to increase, it is important for clinicians to familiarize themselves with management of the condition in those of childbearing age—particularly with regard to medication selection.

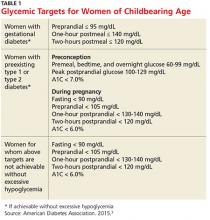

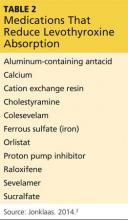

Diabetes management in women of childbearing age presents multiple complexities. First, strict glucose control from preconception through pregnancy is necessary to reduce the risk for complications in mother and fetus. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends an A1C of less than 7% during the preconception period, if achievable without hypoglycemia.3 Full glycemic targets for women are outlined in Table 1.

Continue for medication classes with pregnancy category >>

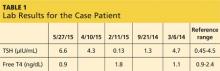

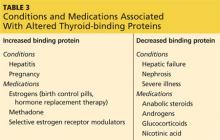

Second, many medications used to manage diabetes and pregnancy-associated comorbidities can be fetotoxic. The FDA assigns all drugs to a pregnancy category, the definitions of which are available at http://chemm.nlm.nih.gov/pregnancycategories.htm.4 The ADA recommends that sexually active women of childbearing age avoid any potentially teratogenic medications (see Table 2) if they are not using reliable contraception.3

Excellent control of diabetes is necessary to decrease risk for birth defects. Infants born to mothers with preconception diabetes have been shown to have higher rates of morbidity and mortality.5 Infants born to women with diabetes are generally large for gestational age and experience hypoglycemia in the first 24 to 48 hours of life.6 Large-for-gestational-age babies are at increased risk for trauma at birth, including orthopedic injuries (eg, shoulder dislocation) and brachial plexus injuries. There is also an increased risk for fetal cardiac defects and congenital congestive heart failure.6

This article will review four cases of diabetes management in women of childbearing age. The ADA guidelines form the basis for all recommendations.

Continue for case 1 >>

Case 1 A 32-year-old obese woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) presents for routine follow-up. Recent lab results reveal an A1C of 6.4%; GFR > 100 mL/min/1.73 m2; and microalbuminuria (110 mg/d). She is currently taking lisinopril (2.5 mg once daily), metformin (1,000 mg bid), and glyburide (5 mg bid). She plans to become pregnant in the next six months and wants advice.

Discussion

This patient should be counseled on preconception glycemic targets and switched to pregnancy-safe medications. She should also be advised that the recommended weight gain in pregnancy for women with T2DM is 15 to 25 lb in overweight women and 10 to 20 lb in obese women.3

The ADA recommends a target A1C < 7%, in the absence of severe hypoglycemia, prior to conception in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) or T2DM.3 For women with preconception diabetes who become pregnant, it is recommended that their premeal, bedtime, and overnight glucose be maintained at 60 to 99 mg/dL, their peak postprandial glucose at 100 to 129 mg/dL, and their A1C < 6% during pregnancy (all without excessive hypoglycemia), due to increases in red blood cell turnover.3 It is also recommended that they avoid statins, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), certain beta blockers, and most noninsulin therapies.3

This patient is currently taking lisinopril, a medication with a pregnancy category of X. The ACE inhibitor class of medications is known to cause oligohydramnios, intrauterine growth retardation, structural malformation, premature birth, fetal renal dysplasia, and other congenital abnormalities, and use of these drugs should be avoided in women trying to conceive.7

Safer options for blood pressure control include clonidine, diltiazam, labetalol, methyldopa, or prazosin.3 Diuretics can reduce placental blood perfusion and should be avoided.8 An alternative for management of microalbuminuria in women of childbearing age is nifedipine.9 In multiple studies, this medication was not only safer in pregnancy, with no major teratogenic risk, but also effectively reduced urine microalbumin levels.10,11

For T2DM management, metformin (pregnancy category B) and glyburide (pregnancy category B/C, depending on manufacturer) can be used.12,13 Glyburide, the most studied sulfonylurea, is recommended as the drug of choice in its class.14-16 While insulin is the standard for managing diabetes in pregnancy—earlier research supported a switch from oral medications to insulin in women interested in becoming pregnant—recent studies have demonstrated that oral medications can be safely used.17 In addition, lifestyle changes (eg, carbohydrate counting, limited meal portions, and regular moderate exercise) prior to and during pregnancy can be beneficial for diabetes management.18,19

Also remind the patient to take regular prenatal vitamins. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends that all women planning to become or capable of becoming pregnant take 400 to 800 µg supplements of folic acid daily.20 For women at high risk for neural tube defects or who have had a previous pregnancy with neural tube defects, 4 mg/d is recommended.21 In women with diabetes who are trying to conceive, a folic acid supplement of 5 mg/d is recommended, beginning three months prior to conception.22

Research shows that diabetic women are less likely to take folic acid supplementation during pregnancy. A study of 6,835 obese or overweight women with diabetes showed that only 35% reported daily folic acid supplementation.23 The study authors recommended all women of childbearing age, especially those who are obese or have diabetes, take folic acid daily.23 Encourage all women intending to become pregnant to start prenatal vitamin supplementation.

Continue for case 2 >>

Case 2 A 26-year-old obese patient, 28 weeks primigravida, presents for follow-up on her 3-hour glucose tolerance test. Results indicate a 3-hour glucose level of 148 mg/dL. The patient has a family history of T2DM and gestational diabetes.

Discussion

Gestational diabetes is defined by the ADA as diabetes diagnosed during the second or third trimester of pregnancy that is not T1DM or T2DM.3 The ADA recommends lifestyle management of gestational diabetes before medications are introduced. A1C should be maintained at 6% or less without hypoglycemia. In general, insulin is preferred over oral agents for treatment of gestational diabetes.3

There tends to be a spike in insulin resistance in the second or third trimester; women with preconception diabetes, for example, may require frequent increases in daily insulin dose to maintain glycemic levels, compared to the first trimester.3 A baseline ophthalmology exam should be performed in the first trimester for patients with preconception diabetes, with additional monitoring as needed.3

Following pregnancy, screening should be conducted for diabetes or prediabetes at six to 12 weeks’ postpartum and every one to three years afterward.3 The cumulative incidence of T2DM varies considerably among studies, ranging from 17% to 63% in five to 16 years postpartum.24,25 Thus, women with gestational diabetes should maintain lifestyle changes, including diet and exercise, to reduce the risk for T2DM later in life.

Continue for case 3 >>

Case 3 A 43-year-old woman with T1DM becomes pregnant while taking atorvastatin (20 mg), insulin detemir (18 units qhs), and insulin aspart with meals, as per her calculated insulin-to-carbohydrate ratio (ICR; 1 U aspart for 18 g carbohydrates) and insulin sensitivity factor (ISF; 1 U aspart for every 60 mg/dL above 130 mg/dL). Her biggest concern today is her medication list and potential adverse effects on the fetus. Her most recent A1C, two months ago, was 6.5%. She senses hypoglycemia at glucose levels of about 60 mg/dL and admits to having such measurements about twice per week.

Discussion

In this case, the patient needs to stop taking her statin and check her blood glucose regularly, as she is at increased risk for hypoglycemia. In their 2013 guidelines, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association stated that statins “should not be used in women of childbearing potential unless these women are using effective contraception and are not nursing.”26 This presents a major problem for many women of childbearing age with diabetes.

Statins are associated with a variety of congenital abnormalities, including fetal growth restriction and structural abnormalities in the fetus.27 It is advised that women planning for pregnancy avoid use of statins.28 If the patient has severe hypertriglyceridemia that puts her at risk for acute pancreatitis, fenofibrate (pregnancy category C) can be considered in the second and third trimesters.29,30

With T1DM in pregnancy, there is an increased risk for hypoglycemia in the first trimester.3 This risk increases as women adapt to more strict blood glucose control. Frequent recalculation of the ICR and ISF may be needed as the pregnancy progresses and weight gain occurs. Most insulin formulations are pregnancy class B, with the exception of glargine, degludec, and glulisine, which are pregnancy category C.3

Continue for case 4 >>

Case 4 A 21-year-old woman with T1DM wishes to start contraception but has concerns about long-term options. She seeks your advice in making a decision.

Discussion

For long-term pregnancy prevention, either the copper or progesterone-containing intrauterine device (IUD) is safe and effective for women with T1DM or T2DM.31 While the levonorgestrel IUD does not produce metabolic changes in T1DM, it has not yet been adequately studied in T2DM. Demographics suggest that young women with T2DM could become viable candidates for intrauterine contraception.31

The hormone-releasing “ring” has been found to be reliable and safe for women of late reproductive age with T1DM.32 Combined hormonal contraceptives and the transdermal contraceptive patch are best avoided to reduce risk for complications associated with estrogen-containing contraceptives (eg, venous thromboembolism and myocardial infarction).33

Continue for the conclusion >>

Conclusion

All women with diabetes should be counseled on glucose control prior to pregnancy. Achieving a goal A1C below 6% in the absence of hypoglycemia is recommended by the ADA.3 Long-term contraception options should be considered in women of childbearing age with diabetes to prevent pregnancy. Clinicians should carefully select medications for management of diabetes and its comorbidities in women planning to become pregnant. Healthy dietary habits and regular exercise should be encouraged in all patients with diabetes, especially prior to pregnancy.

References

1. CDC. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2014. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/statsreport14/national-diabetes-report-web.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2016.

2. CDC. Number of Americans with diabetes projected to double or triple by 2050. 2010. www.cdc.gov/media/pressrel/2010/r101022.html. Accessed January 12, 2016.

3. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2015. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(suppl 1):S1-S93.

4. Chemical Hazards Emergency Medical Management. FDA pregnancy categories. http://chemm.nlm.nih.gov/pregnancycategories.htm. Accessed January 12, 2016.

5. Weindling AM. Offspring of diabetic pregnancy: short-term outcomes. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;14(2):111-118.

6. Kaneshiro NK. Infant of diabetic mother (2013). Medline Plus. www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/001597.htm. Accessed January 12, 2016.

7. Shotan A, Widerhorn J, Hurst A, Elkayam U. Risks of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition during pregnancy: experimental and clinical evidence, potential mechanisms, and recommendations for use. Am J Med. 1994;96(5):451-456.

8. Sibai BM. Treatment of hypertension in pregnant women. N Engl J Med. 1996;335 (4):257-265.

9. Ismail AA, Medhat I, Tawfic TA, Kholeif A. Evaluation of calcium-antagonists (nifedipine) in the treatment of pre-eclampsia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1993;40:39-43.

10. Magee LA, Schick B, Donnenfeld AE, et al. The safety of calcium channel blockers in human pregnancy: a prospective, multicenter cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174(3):823-828.

11. Kattah AG, Garovic VD. The management of hypertension in pregnancy. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2013;20(3):229-239.

12. Carroll DG, Kelley KW. Review of metformin and glyburide in the management of gestational diabetes. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2014;12(4):528.

13. Koren G. Glyburide and fetal safety; transplacental pharmacokinetic considerations. Reprod Toxicol. 2001;15(3):227-229.

14. Elliott BD, Langer O, Schenker S, Johnson RF. Insignificant transfer of glyburide occurs across the human placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:807-812.

15. Moore TR. Glyburide for the treatment of gestational diabetes: a critical appraisal. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(suppl 2):S209-S213.

16. Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1183-1197.

17. Kalra B, Gupta Y, Singla R, Kalra S. Use of oral anti-diabetic agents in pregnancy: a pragmatic approach. N Am J Med Sci. 2015; 7(1):6-12.

18. Zhang C, Ning Y. Effect of dietary and lifestyle factors on the risk of gestational diabetes: review of epidemiologic evidence. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(6 suppl):1975S-1979S.

19. Metzger BE, Buchanan TA, Coustan DR, et al. Summary and recommendations of the Fifth International Workshop-Conference on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(suppl 2):S251-S260.

20. US Preventive Services Task Force. Folic acid to prevent neural tube defects: preventive medication, 2015. www.uspreventiveservices taskforce.org/Page/Document/Update SummaryFinal/folic-acid-to-prevent-neural-tube-defects-preventive-medication. Accessed January 12, 2016.

21. Cheschier N; ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Neural tube defects. ACOG Practice Bulletin no 44. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83(1):123-133.

22. Blumer I, Hadar E, Hadden DR, et al. Diabetes and pregnancy: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(11):4227-4249.

23. Case AP, Ramadhani TA, Canfield MA, et al. Folic acid supplementation among diabetic, overweight, or obese women of childbearing age. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2007;36(4):335-341.

24. Hanna FWF, Peters JR. Screening for gestational diabetes; past, present and future. Diabet Med. 2002;19:351-358.

25. Ben-haroush A, Yogev Y, Hod M. Epidemiology of gestational diabetes mellitus and its association with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2004;21(2):103-113.

26. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 suppl 2):S1-S45.

27. Patel C, Edgerton L, Flake D. What precautions should we use with statins for women of childbearing age? J Fam Pract. 2006; 55(1):75-77.

28. Kazmin A, Garcia-Bournissen F, Koren G. Risks of statin use during pregnancy: a systematic review. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2007;29(11):906-908.

29. Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al. Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012; 97(9):2969-2989.

30. Saadi HF, Kurlander DJ, Erkins JM, Hoogwerf BJ. Severe hypertriglyceridemia and acute pancreatitis during pregnancy: treatment with gemfibrozil. Endocr Pract. 1999;5(1):33-36.

31. Goldstuck ND, Steyn PS. The intrauterine device in women with diabetes mellitus type I and II: a systematic review. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:814062.

32. Grigoryan OR, Grodnitskaya EE, Andreeva EN, et al. Use of the NuvaRing hormone-releasing system in late reproductive-age women with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2008;24(2):99-104.

33. Bonnema RA, McNamara MC, Spencer AL. Contraception choices in women with underlying medical conditions. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(6):621-628.

There were 13.4 million women (ages 20 and older) with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes in the United States in 2012, according to the CDC.1 By 2050, overall prevalence of diabetes is expected to double or triple.2 Since the number of women with diabetes will continue to increase, it is important for clinicians to familiarize themselves with management of the condition in those of childbearing age—particularly with regard to medication selection.

Diabetes management in women of childbearing age presents multiple complexities. First, strict glucose control from preconception through pregnancy is necessary to reduce the risk for complications in mother and fetus. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends an A1C of less than 7% during the preconception period, if achievable without hypoglycemia.3 Full glycemic targets for women are outlined in Table 1.

Continue for medication classes with pregnancy category >>

Second, many medications used to manage diabetes and pregnancy-associated comorbidities can be fetotoxic. The FDA assigns all drugs to a pregnancy category, the definitions of which are available at http://chemm.nlm.nih.gov/pregnancycategories.htm.4 The ADA recommends that sexually active women of childbearing age avoid any potentially teratogenic medications (see Table 2) if they are not using reliable contraception.3

Excellent control of diabetes is necessary to decrease risk for birth defects. Infants born to mothers with preconception diabetes have been shown to have higher rates of morbidity and mortality.5 Infants born to women with diabetes are generally large for gestational age and experience hypoglycemia in the first 24 to 48 hours of life.6 Large-for-gestational-age babies are at increased risk for trauma at birth, including orthopedic injuries (eg, shoulder dislocation) and brachial plexus injuries. There is also an increased risk for fetal cardiac defects and congenital congestive heart failure.6

This article will review four cases of diabetes management in women of childbearing age. The ADA guidelines form the basis for all recommendations.

Continue for case 1 >>

Case 1 A 32-year-old obese woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) presents for routine follow-up. Recent lab results reveal an A1C of 6.4%; GFR > 100 mL/min/1.73 m2; and microalbuminuria (110 mg/d). She is currently taking lisinopril (2.5 mg once daily), metformin (1,000 mg bid), and glyburide (5 mg bid). She plans to become pregnant in the next six months and wants advice.

Discussion

This patient should be counseled on preconception glycemic targets and switched to pregnancy-safe medications. She should also be advised that the recommended weight gain in pregnancy for women with T2DM is 15 to 25 lb in overweight women and 10 to 20 lb in obese women.3

The ADA recommends a target A1C < 7%, in the absence of severe hypoglycemia, prior to conception in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) or T2DM.3 For women with preconception diabetes who become pregnant, it is recommended that their premeal, bedtime, and overnight glucose be maintained at 60 to 99 mg/dL, their peak postprandial glucose at 100 to 129 mg/dL, and their A1C < 6% during pregnancy (all without excessive hypoglycemia), due to increases in red blood cell turnover.3 It is also recommended that they avoid statins, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), certain beta blockers, and most noninsulin therapies.3

This patient is currently taking lisinopril, a medication with a pregnancy category of X. The ACE inhibitor class of medications is known to cause oligohydramnios, intrauterine growth retardation, structural malformation, premature birth, fetal renal dysplasia, and other congenital abnormalities, and use of these drugs should be avoided in women trying to conceive.7

Safer options for blood pressure control include clonidine, diltiazam, labetalol, methyldopa, or prazosin.3 Diuretics can reduce placental blood perfusion and should be avoided.8 An alternative for management of microalbuminuria in women of childbearing age is nifedipine.9 In multiple studies, this medication was not only safer in pregnancy, with no major teratogenic risk, but also effectively reduced urine microalbumin levels.10,11

For T2DM management, metformin (pregnancy category B) and glyburide (pregnancy category B/C, depending on manufacturer) can be used.12,13 Glyburide, the most studied sulfonylurea, is recommended as the drug of choice in its class.14-16 While insulin is the standard for managing diabetes in pregnancy—earlier research supported a switch from oral medications to insulin in women interested in becoming pregnant—recent studies have demonstrated that oral medications can be safely used.17 In addition, lifestyle changes (eg, carbohydrate counting, limited meal portions, and regular moderate exercise) prior to and during pregnancy can be beneficial for diabetes management.18,19

Also remind the patient to take regular prenatal vitamins. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends that all women planning to become or capable of becoming pregnant take 400 to 800 µg supplements of folic acid daily.20 For women at high risk for neural tube defects or who have had a previous pregnancy with neural tube defects, 4 mg/d is recommended.21 In women with diabetes who are trying to conceive, a folic acid supplement of 5 mg/d is recommended, beginning three months prior to conception.22

Research shows that diabetic women are less likely to take folic acid supplementation during pregnancy. A study of 6,835 obese or overweight women with diabetes showed that only 35% reported daily folic acid supplementation.23 The study authors recommended all women of childbearing age, especially those who are obese or have diabetes, take folic acid daily.23 Encourage all women intending to become pregnant to start prenatal vitamin supplementation.

Continue for case 2 >>

Case 2 A 26-year-old obese patient, 28 weeks primigravida, presents for follow-up on her 3-hour glucose tolerance test. Results indicate a 3-hour glucose level of 148 mg/dL. The patient has a family history of T2DM and gestational diabetes.

Discussion

Gestational diabetes is defined by the ADA as diabetes diagnosed during the second or third trimester of pregnancy that is not T1DM or T2DM.3 The ADA recommends lifestyle management of gestational diabetes before medications are introduced. A1C should be maintained at 6% or less without hypoglycemia. In general, insulin is preferred over oral agents for treatment of gestational diabetes.3

There tends to be a spike in insulin resistance in the second or third trimester; women with preconception diabetes, for example, may require frequent increases in daily insulin dose to maintain glycemic levels, compared to the first trimester.3 A baseline ophthalmology exam should be performed in the first trimester for patients with preconception diabetes, with additional monitoring as needed.3

Following pregnancy, screening should be conducted for diabetes or prediabetes at six to 12 weeks’ postpartum and every one to three years afterward.3 The cumulative incidence of T2DM varies considerably among studies, ranging from 17% to 63% in five to 16 years postpartum.24,25 Thus, women with gestational diabetes should maintain lifestyle changes, including diet and exercise, to reduce the risk for T2DM later in life.

Continue for case 3 >>

Case 3 A 43-year-old woman with T1DM becomes pregnant while taking atorvastatin (20 mg), insulin detemir (18 units qhs), and insulin aspart with meals, as per her calculated insulin-to-carbohydrate ratio (ICR; 1 U aspart for 18 g carbohydrates) and insulin sensitivity factor (ISF; 1 U aspart for every 60 mg/dL above 130 mg/dL). Her biggest concern today is her medication list and potential adverse effects on the fetus. Her most recent A1C, two months ago, was 6.5%. She senses hypoglycemia at glucose levels of about 60 mg/dL and admits to having such measurements about twice per week.

Discussion

In this case, the patient needs to stop taking her statin and check her blood glucose regularly, as she is at increased risk for hypoglycemia. In their 2013 guidelines, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association stated that statins “should not be used in women of childbearing potential unless these women are using effective contraception and are not nursing.”26 This presents a major problem for many women of childbearing age with diabetes.

Statins are associated with a variety of congenital abnormalities, including fetal growth restriction and structural abnormalities in the fetus.27 It is advised that women planning for pregnancy avoid use of statins.28 If the patient has severe hypertriglyceridemia that puts her at risk for acute pancreatitis, fenofibrate (pregnancy category C) can be considered in the second and third trimesters.29,30

With T1DM in pregnancy, there is an increased risk for hypoglycemia in the first trimester.3 This risk increases as women adapt to more strict blood glucose control. Frequent recalculation of the ICR and ISF may be needed as the pregnancy progresses and weight gain occurs. Most insulin formulations are pregnancy class B, with the exception of glargine, degludec, and glulisine, which are pregnancy category C.3

Continue for case 4 >>

Case 4 A 21-year-old woman with T1DM wishes to start contraception but has concerns about long-term options. She seeks your advice in making a decision.

Discussion

For long-term pregnancy prevention, either the copper or progesterone-containing intrauterine device (IUD) is safe and effective for women with T1DM or T2DM.31 While the levonorgestrel IUD does not produce metabolic changes in T1DM, it has not yet been adequately studied in T2DM. Demographics suggest that young women with T2DM could become viable candidates for intrauterine contraception.31

The hormone-releasing “ring” has been found to be reliable and safe for women of late reproductive age with T1DM.32 Combined hormonal contraceptives and the transdermal contraceptive patch are best avoided to reduce risk for complications associated with estrogen-containing contraceptives (eg, venous thromboembolism and myocardial infarction).33

Continue for the conclusion >>

Conclusion

All women with diabetes should be counseled on glucose control prior to pregnancy. Achieving a goal A1C below 6% in the absence of hypoglycemia is recommended by the ADA.3 Long-term contraception options should be considered in women of childbearing age with diabetes to prevent pregnancy. Clinicians should carefully select medications for management of diabetes and its comorbidities in women planning to become pregnant. Healthy dietary habits and regular exercise should be encouraged in all patients with diabetes, especially prior to pregnancy.

References

1. CDC. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2014. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/statsreport14/national-diabetes-report-web.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2016.

2. CDC. Number of Americans with diabetes projected to double or triple by 2050. 2010. www.cdc.gov/media/pressrel/2010/r101022.html. Accessed January 12, 2016.

3. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2015. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(suppl 1):S1-S93.

4. Chemical Hazards Emergency Medical Management. FDA pregnancy categories. http://chemm.nlm.nih.gov/pregnancycategories.htm. Accessed January 12, 2016.

5. Weindling AM. Offspring of diabetic pregnancy: short-term outcomes. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;14(2):111-118.

6. Kaneshiro NK. Infant of diabetic mother (2013). Medline Plus. www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/001597.htm. Accessed January 12, 2016.

7. Shotan A, Widerhorn J, Hurst A, Elkayam U. Risks of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition during pregnancy: experimental and clinical evidence, potential mechanisms, and recommendations for use. Am J Med. 1994;96(5):451-456.

8. Sibai BM. Treatment of hypertension in pregnant women. N Engl J Med. 1996;335 (4):257-265.

9. Ismail AA, Medhat I, Tawfic TA, Kholeif A. Evaluation of calcium-antagonists (nifedipine) in the treatment of pre-eclampsia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1993;40:39-43.

10. Magee LA, Schick B, Donnenfeld AE, et al. The safety of calcium channel blockers in human pregnancy: a prospective, multicenter cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174(3):823-828.

11. Kattah AG, Garovic VD. The management of hypertension in pregnancy. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2013;20(3):229-239.

12. Carroll DG, Kelley KW. Review of metformin and glyburide in the management of gestational diabetes. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2014;12(4):528.

13. Koren G. Glyburide and fetal safety; transplacental pharmacokinetic considerations. Reprod Toxicol. 2001;15(3):227-229.

14. Elliott BD, Langer O, Schenker S, Johnson RF. Insignificant transfer of glyburide occurs across the human placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:807-812.

15. Moore TR. Glyburide for the treatment of gestational diabetes: a critical appraisal. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(suppl 2):S209-S213.

16. Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1183-1197.

17. Kalra B, Gupta Y, Singla R, Kalra S. Use of oral anti-diabetic agents in pregnancy: a pragmatic approach. N Am J Med Sci. 2015; 7(1):6-12.

18. Zhang C, Ning Y. Effect of dietary and lifestyle factors on the risk of gestational diabetes: review of epidemiologic evidence. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(6 suppl):1975S-1979S.

19. Metzger BE, Buchanan TA, Coustan DR, et al. Summary and recommendations of the Fifth International Workshop-Conference on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(suppl 2):S251-S260.

20. US Preventive Services Task Force. Folic acid to prevent neural tube defects: preventive medication, 2015. www.uspreventiveservices taskforce.org/Page/Document/Update SummaryFinal/folic-acid-to-prevent-neural-tube-defects-preventive-medication. Accessed January 12, 2016.

21. Cheschier N; ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Neural tube defects. ACOG Practice Bulletin no 44. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83(1):123-133.

22. Blumer I, Hadar E, Hadden DR, et al. Diabetes and pregnancy: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(11):4227-4249.

23. Case AP, Ramadhani TA, Canfield MA, et al. Folic acid supplementation among diabetic, overweight, or obese women of childbearing age. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2007;36(4):335-341.

24. Hanna FWF, Peters JR. Screening for gestational diabetes; past, present and future. Diabet Med. 2002;19:351-358.

25. Ben-haroush A, Yogev Y, Hod M. Epidemiology of gestational diabetes mellitus and its association with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2004;21(2):103-113.

26. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 suppl 2):S1-S45.

27. Patel C, Edgerton L, Flake D. What precautions should we use with statins for women of childbearing age? J Fam Pract. 2006; 55(1):75-77.

28. Kazmin A, Garcia-Bournissen F, Koren G. Risks of statin use during pregnancy: a systematic review. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2007;29(11):906-908.

29. Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al. Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012; 97(9):2969-2989.

30. Saadi HF, Kurlander DJ, Erkins JM, Hoogwerf BJ. Severe hypertriglyceridemia and acute pancreatitis during pregnancy: treatment with gemfibrozil. Endocr Pract. 1999;5(1):33-36.

31. Goldstuck ND, Steyn PS. The intrauterine device in women with diabetes mellitus type I and II: a systematic review. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:814062.

32. Grigoryan OR, Grodnitskaya EE, Andreeva EN, et al. Use of the NuvaRing hormone-releasing system in late reproductive-age women with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2008;24(2):99-104.

33. Bonnema RA, McNamara MC, Spencer AL. Contraception choices in women with underlying medical conditions. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(6):621-628.

There were 13.4 million women (ages 20 and older) with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes in the United States in 2012, according to the CDC.1 By 2050, overall prevalence of diabetes is expected to double or triple.2 Since the number of women with diabetes will continue to increase, it is important for clinicians to familiarize themselves with management of the condition in those of childbearing age—particularly with regard to medication selection.

Diabetes management in women of childbearing age presents multiple complexities. First, strict glucose control from preconception through pregnancy is necessary to reduce the risk for complications in mother and fetus. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends an A1C of less than 7% during the preconception period, if achievable without hypoglycemia.3 Full glycemic targets for women are outlined in Table 1.

Continue for medication classes with pregnancy category >>

Second, many medications used to manage diabetes and pregnancy-associated comorbidities can be fetotoxic. The FDA assigns all drugs to a pregnancy category, the definitions of which are available at http://chemm.nlm.nih.gov/pregnancycategories.htm.4 The ADA recommends that sexually active women of childbearing age avoid any potentially teratogenic medications (see Table 2) if they are not using reliable contraception.3

Excellent control of diabetes is necessary to decrease risk for birth defects. Infants born to mothers with preconception diabetes have been shown to have higher rates of morbidity and mortality.5 Infants born to women with diabetes are generally large for gestational age and experience hypoglycemia in the first 24 to 48 hours of life.6 Large-for-gestational-age babies are at increased risk for trauma at birth, including orthopedic injuries (eg, shoulder dislocation) and brachial plexus injuries. There is also an increased risk for fetal cardiac defects and congenital congestive heart failure.6

This article will review four cases of diabetes management in women of childbearing age. The ADA guidelines form the basis for all recommendations.

Continue for case 1 >>

Case 1 A 32-year-old obese woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) presents for routine follow-up. Recent lab results reveal an A1C of 6.4%; GFR > 100 mL/min/1.73 m2; and microalbuminuria (110 mg/d). She is currently taking lisinopril (2.5 mg once daily), metformin (1,000 mg bid), and glyburide (5 mg bid). She plans to become pregnant in the next six months and wants advice.

Discussion

This patient should be counseled on preconception glycemic targets and switched to pregnancy-safe medications. She should also be advised that the recommended weight gain in pregnancy for women with T2DM is 15 to 25 lb in overweight women and 10 to 20 lb in obese women.3

The ADA recommends a target A1C < 7%, in the absence of severe hypoglycemia, prior to conception in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) or T2DM.3 For women with preconception diabetes who become pregnant, it is recommended that their premeal, bedtime, and overnight glucose be maintained at 60 to 99 mg/dL, their peak postprandial glucose at 100 to 129 mg/dL, and their A1C < 6% during pregnancy (all without excessive hypoglycemia), due to increases in red blood cell turnover.3 It is also recommended that they avoid statins, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), certain beta blockers, and most noninsulin therapies.3

This patient is currently taking lisinopril, a medication with a pregnancy category of X. The ACE inhibitor class of medications is known to cause oligohydramnios, intrauterine growth retardation, structural malformation, premature birth, fetal renal dysplasia, and other congenital abnormalities, and use of these drugs should be avoided in women trying to conceive.7

Safer options for blood pressure control include clonidine, diltiazam, labetalol, methyldopa, or prazosin.3 Diuretics can reduce placental blood perfusion and should be avoided.8 An alternative for management of microalbuminuria in women of childbearing age is nifedipine.9 In multiple studies, this medication was not only safer in pregnancy, with no major teratogenic risk, but also effectively reduced urine microalbumin levels.10,11

For T2DM management, metformin (pregnancy category B) and glyburide (pregnancy category B/C, depending on manufacturer) can be used.12,13 Glyburide, the most studied sulfonylurea, is recommended as the drug of choice in its class.14-16 While insulin is the standard for managing diabetes in pregnancy—earlier research supported a switch from oral medications to insulin in women interested in becoming pregnant—recent studies have demonstrated that oral medications can be safely used.17 In addition, lifestyle changes (eg, carbohydrate counting, limited meal portions, and regular moderate exercise) prior to and during pregnancy can be beneficial for diabetes management.18,19

Also remind the patient to take regular prenatal vitamins. The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends that all women planning to become or capable of becoming pregnant take 400 to 800 µg supplements of folic acid daily.20 For women at high risk for neural tube defects or who have had a previous pregnancy with neural tube defects, 4 mg/d is recommended.21 In women with diabetes who are trying to conceive, a folic acid supplement of 5 mg/d is recommended, beginning three months prior to conception.22

Research shows that diabetic women are less likely to take folic acid supplementation during pregnancy. A study of 6,835 obese or overweight women with diabetes showed that only 35% reported daily folic acid supplementation.23 The study authors recommended all women of childbearing age, especially those who are obese or have diabetes, take folic acid daily.23 Encourage all women intending to become pregnant to start prenatal vitamin supplementation.

Continue for case 2 >>

Case 2 A 26-year-old obese patient, 28 weeks primigravida, presents for follow-up on her 3-hour glucose tolerance test. Results indicate a 3-hour glucose level of 148 mg/dL. The patient has a family history of T2DM and gestational diabetes.

Discussion

Gestational diabetes is defined by the ADA as diabetes diagnosed during the second or third trimester of pregnancy that is not T1DM or T2DM.3 The ADA recommends lifestyle management of gestational diabetes before medications are introduced. A1C should be maintained at 6% or less without hypoglycemia. In general, insulin is preferred over oral agents for treatment of gestational diabetes.3

There tends to be a spike in insulin resistance in the second or third trimester; women with preconception diabetes, for example, may require frequent increases in daily insulin dose to maintain glycemic levels, compared to the first trimester.3 A baseline ophthalmology exam should be performed in the first trimester for patients with preconception diabetes, with additional monitoring as needed.3

Following pregnancy, screening should be conducted for diabetes or prediabetes at six to 12 weeks’ postpartum and every one to three years afterward.3 The cumulative incidence of T2DM varies considerably among studies, ranging from 17% to 63% in five to 16 years postpartum.24,25 Thus, women with gestational diabetes should maintain lifestyle changes, including diet and exercise, to reduce the risk for T2DM later in life.

Continue for case 3 >>

Case 3 A 43-year-old woman with T1DM becomes pregnant while taking atorvastatin (20 mg), insulin detemir (18 units qhs), and insulin aspart with meals, as per her calculated insulin-to-carbohydrate ratio (ICR; 1 U aspart for 18 g carbohydrates) and insulin sensitivity factor (ISF; 1 U aspart for every 60 mg/dL above 130 mg/dL). Her biggest concern today is her medication list and potential adverse effects on the fetus. Her most recent A1C, two months ago, was 6.5%. She senses hypoglycemia at glucose levels of about 60 mg/dL and admits to having such measurements about twice per week.

Discussion

In this case, the patient needs to stop taking her statin and check her blood glucose regularly, as she is at increased risk for hypoglycemia. In their 2013 guidelines, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association stated that statins “should not be used in women of childbearing potential unless these women are using effective contraception and are not nursing.”26 This presents a major problem for many women of childbearing age with diabetes.

Statins are associated with a variety of congenital abnormalities, including fetal growth restriction and structural abnormalities in the fetus.27 It is advised that women planning for pregnancy avoid use of statins.28 If the patient has severe hypertriglyceridemia that puts her at risk for acute pancreatitis, fenofibrate (pregnancy category C) can be considered in the second and third trimesters.29,30

With T1DM in pregnancy, there is an increased risk for hypoglycemia in the first trimester.3 This risk increases as women adapt to more strict blood glucose control. Frequent recalculation of the ICR and ISF may be needed as the pregnancy progresses and weight gain occurs. Most insulin formulations are pregnancy class B, with the exception of glargine, degludec, and glulisine, which are pregnancy category C.3

Continue for case 4 >>

Case 4 A 21-year-old woman with T1DM wishes to start contraception but has concerns about long-term options. She seeks your advice in making a decision.

Discussion

For long-term pregnancy prevention, either the copper or progesterone-containing intrauterine device (IUD) is safe and effective for women with T1DM or T2DM.31 While the levonorgestrel IUD does not produce metabolic changes in T1DM, it has not yet been adequately studied in T2DM. Demographics suggest that young women with T2DM could become viable candidates for intrauterine contraception.31

The hormone-releasing “ring” has been found to be reliable and safe for women of late reproductive age with T1DM.32 Combined hormonal contraceptives and the transdermal contraceptive patch are best avoided to reduce risk for complications associated with estrogen-containing contraceptives (eg, venous thromboembolism and myocardial infarction).33

Continue for the conclusion >>

Conclusion

All women with diabetes should be counseled on glucose control prior to pregnancy. Achieving a goal A1C below 6% in the absence of hypoglycemia is recommended by the ADA.3 Long-term contraception options should be considered in women of childbearing age with diabetes to prevent pregnancy. Clinicians should carefully select medications for management of diabetes and its comorbidities in women planning to become pregnant. Healthy dietary habits and regular exercise should be encouraged in all patients with diabetes, especially prior to pregnancy.

References

1. CDC. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2014. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/statsreport14/national-diabetes-report-web.pdf. Accessed January 12, 2016.

2. CDC. Number of Americans with diabetes projected to double or triple by 2050. 2010. www.cdc.gov/media/pressrel/2010/r101022.html. Accessed January 12, 2016.

3. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2015. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(suppl 1):S1-S93.

4. Chemical Hazards Emergency Medical Management. FDA pregnancy categories. http://chemm.nlm.nih.gov/pregnancycategories.htm. Accessed January 12, 2016.

5. Weindling AM. Offspring of diabetic pregnancy: short-term outcomes. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;14(2):111-118.

6. Kaneshiro NK. Infant of diabetic mother (2013). Medline Plus. www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/001597.htm. Accessed January 12, 2016.

7. Shotan A, Widerhorn J, Hurst A, Elkayam U. Risks of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition during pregnancy: experimental and clinical evidence, potential mechanisms, and recommendations for use. Am J Med. 1994;96(5):451-456.

8. Sibai BM. Treatment of hypertension in pregnant women. N Engl J Med. 1996;335 (4):257-265.

9. Ismail AA, Medhat I, Tawfic TA, Kholeif A. Evaluation of calcium-antagonists (nifedipine) in the treatment of pre-eclampsia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1993;40:39-43.

10. Magee LA, Schick B, Donnenfeld AE, et al. The safety of calcium channel blockers in human pregnancy: a prospective, multicenter cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174(3):823-828.

11. Kattah AG, Garovic VD. The management of hypertension in pregnancy. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2013;20(3):229-239.

12. Carroll DG, Kelley KW. Review of metformin and glyburide in the management of gestational diabetes. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2014;12(4):528.

13. Koren G. Glyburide and fetal safety; transplacental pharmacokinetic considerations. Reprod Toxicol. 2001;15(3):227-229.

14. Elliott BD, Langer O, Schenker S, Johnson RF. Insignificant transfer of glyburide occurs across the human placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165:807-812.

15. Moore TR. Glyburide for the treatment of gestational diabetes: a critical appraisal. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(suppl 2):S209-S213.

16. Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1183-1197.

17. Kalra B, Gupta Y, Singla R, Kalra S. Use of oral anti-diabetic agents in pregnancy: a pragmatic approach. N Am J Med Sci. 2015; 7(1):6-12.

18. Zhang C, Ning Y. Effect of dietary and lifestyle factors on the risk of gestational diabetes: review of epidemiologic evidence. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(6 suppl):1975S-1979S.

19. Metzger BE, Buchanan TA, Coustan DR, et al. Summary and recommendations of the Fifth International Workshop-Conference on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(suppl 2):S251-S260.

20. US Preventive Services Task Force. Folic acid to prevent neural tube defects: preventive medication, 2015. www.uspreventiveservices taskforce.org/Page/Document/Update SummaryFinal/folic-acid-to-prevent-neural-tube-defects-preventive-medication. Accessed January 12, 2016.

21. Cheschier N; ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Neural tube defects. ACOG Practice Bulletin no 44. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;83(1):123-133.

22. Blumer I, Hadar E, Hadden DR, et al. Diabetes and pregnancy: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(11):4227-4249.

23. Case AP, Ramadhani TA, Canfield MA, et al. Folic acid supplementation among diabetic, overweight, or obese women of childbearing age. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2007;36(4):335-341.

24. Hanna FWF, Peters JR. Screening for gestational diabetes; past, present and future. Diabet Med. 2002;19:351-358.

25. Ben-haroush A, Yogev Y, Hod M. Epidemiology of gestational diabetes mellitus and its association with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2004;21(2):103-113.

26. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 suppl 2):S1-S45.

27. Patel C, Edgerton L, Flake D. What precautions should we use with statins for women of childbearing age? J Fam Pract. 2006; 55(1):75-77.

28. Kazmin A, Garcia-Bournissen F, Koren G. Risks of statin use during pregnancy: a systematic review. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2007;29(11):906-908.

29. Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al. Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012; 97(9):2969-2989.

30. Saadi HF, Kurlander DJ, Erkins JM, Hoogwerf BJ. Severe hypertriglyceridemia and acute pancreatitis during pregnancy: treatment with gemfibrozil. Endocr Pract. 1999;5(1):33-36.

31. Goldstuck ND, Steyn PS. The intrauterine device in women with diabetes mellitus type I and II: a systematic review. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2013;2013:814062.

32. Grigoryan OR, Grodnitskaya EE, Andreeva EN, et al. Use of the NuvaRing hormone-releasing system in late reproductive-age women with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2008;24(2):99-104.

33. Bonnema RA, McNamara MC, Spencer AL. Contraception choices in women with underlying medical conditions. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82(6):621-628.

Disease Education

Q) The billing consultant who came to our office said we can increase our reimbursements if we also provide education to our patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Is she right?

In 2010, under an omnibus bill, kidney disease education (KDE) classes were added as a Medicare benefit. These are for patients with stage 4 CKD (glomerular filtration rate, 15-30 mL/min) and are to be taught by a qualified instructor (MD, PA, NP, or CNS).

The classes can be taught on the same day as an evaluation/management visit (ie, a regular office visit) and are compensated by the hour. (Side note: Medicare defines an hour as 31 minutes—yes, 31 minutes; Medicare takes for granted that you will also need time to chart!) You can teach two classes in the same day. Thus, if you wanted to, you could have a patient arrive for an office visit, then teach two 31-minute classes, and bill all three for the same day. The entire visit could be 75 minutes (although this may be exhausting for this population).

You can conduct the classes in a number of settings, including nursing homes, hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, the office, or even the patient’s home. Many PAs and NPs have taught these classes to hospitalized patients who have lost kidney function due to an acute insult (ie, medications, dehydration, contrast).

Each Medicare recipient has a lifetime benefit of six KDE classes. The CPT billing code is G0420 for an individual class and G0421 for a group class. You must make sure you also code for the stage 4 CKD diagnosis (code: 585.4).

Congress stipulated KDE classes must include information on causes, symptoms, and treatments and comprise a posttest at a specific health literacy level. To make it simple, the National Kidney Foundation Council of Advanced Practitioners (NKF-CAP) has developed two free Power-Point slide decks for clinicians to use in KDE classes (available at www.kidney.org/professionals/CAP/sub_resources#kde). References and updated peer-reviewed guidelines are included. You can print the slides for your patients and/or share the program with your colleagues.

Many nephrology practitioners teach the two slide sets over and over, because patients only retain one-third of the info we provide them on a given day. So if you teach each slide set three times, you have six lifetime classes—and hopefully the patient will have retained everything.

One caveat: Before you initiate KDE classes for a specific patient, check with the patient’s nephrology group (we hope at stage 4 the patient has a nephrologist) to see if they are providing the education. —KZ and JD

Kim Zuber, PA-C, MSPS, DFAAPA

American Academy of Nephrology PAs

Jane S. Davis, CRNP, DNP

Division of Nephrology at the University of Alabama

National Kidney Foundation's Council of Advanced Practitioners

Q) The billing consultant who came to our office said we can increase our reimbursements if we also provide education to our patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Is she right?

In 2010, under an omnibus bill, kidney disease education (KDE) classes were added as a Medicare benefit. These are for patients with stage 4 CKD (glomerular filtration rate, 15-30 mL/min) and are to be taught by a qualified instructor (MD, PA, NP, or CNS).

The classes can be taught on the same day as an evaluation/management visit (ie, a regular office visit) and are compensated by the hour. (Side note: Medicare defines an hour as 31 minutes—yes, 31 minutes; Medicare takes for granted that you will also need time to chart!) You can teach two classes in the same day. Thus, if you wanted to, you could have a patient arrive for an office visit, then teach two 31-minute classes, and bill all three for the same day. The entire visit could be 75 minutes (although this may be exhausting for this population).

You can conduct the classes in a number of settings, including nursing homes, hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, the office, or even the patient’s home. Many PAs and NPs have taught these classes to hospitalized patients who have lost kidney function due to an acute insult (ie, medications, dehydration, contrast).

Each Medicare recipient has a lifetime benefit of six KDE classes. The CPT billing code is G0420 for an individual class and G0421 for a group class. You must make sure you also code for the stage 4 CKD diagnosis (code: 585.4).