User login

Opiate-prescribing standard decreases opiate use in hospitalized patients

Clinical question: Can an opiate-prescribing standard that favors oral and subcutaneous over intravenous administration reduce exposure to intravenous opiates for hospitalized adults?

Background: IV opiates, while effective for analgesia, may have a higher addictive potential because of the rapid and intermittent rises of peak concentrations. Subcutaneous and/or oral administration is a proven method of opioid delivery with similar bioavailability and efficacy of intravenous administration with more favorable pharmacokinetics.

Study design: Intervention-based quality improvement project.

Setting: Adult general medicine inpatient unit in an urban academic center.

Synopsis: Clinical leadership of the study unit collaborated to create an opiate-prescribing standard recommending oral over parenteral opioids and subcutaneous over IV if parental administration was required. The standard was promoted and reinforced with prescriber and nurse education, and prescribers were able to order intravenous opiates per usual protocol.

After a 6-month preintervention control period of 4,500 patient-days, the 3-month intervention period included 2,459 patient-days and led to a 84% decrease in IV opiate doses (0.06 vs. 0.39; P less than .001) and a 55% decrease in parenteral doses (0.18 vs. 0.39; P less than .001). Surprisingly there was a 23% decrease in overall doses of opiates (0.73 vs. 0.95; P = .02). Pain scores were similar between the two groups during hospital days 1-3 and improved in the intervention group between days 4 and 5.

This study was limited by a narrow focus, unblinded participants, and nursing-reported pain scores. While promising, more information is needed before establishing conclusions on a broader scale.

Bottom line: Establishing and promoting an opioid prescribing standard on a single unit led to a decrease in intravenous, parenteral, and overall opiates prescribed with similar or improved pain scores.

Citation: Ackerman AL et al. Association of an opioid standard of practice intervention with intravenous opioid exposure in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jun 1;178(6):759-63.

Dr. Chowdury is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of Colorado, Denver.

Clinical question: Can an opiate-prescribing standard that favors oral and subcutaneous over intravenous administration reduce exposure to intravenous opiates for hospitalized adults?

Background: IV opiates, while effective for analgesia, may have a higher addictive potential because of the rapid and intermittent rises of peak concentrations. Subcutaneous and/or oral administration is a proven method of opioid delivery with similar bioavailability and efficacy of intravenous administration with more favorable pharmacokinetics.

Study design: Intervention-based quality improvement project.

Setting: Adult general medicine inpatient unit in an urban academic center.

Synopsis: Clinical leadership of the study unit collaborated to create an opiate-prescribing standard recommending oral over parenteral opioids and subcutaneous over IV if parental administration was required. The standard was promoted and reinforced with prescriber and nurse education, and prescribers were able to order intravenous opiates per usual protocol.

After a 6-month preintervention control period of 4,500 patient-days, the 3-month intervention period included 2,459 patient-days and led to a 84% decrease in IV opiate doses (0.06 vs. 0.39; P less than .001) and a 55% decrease in parenteral doses (0.18 vs. 0.39; P less than .001). Surprisingly there was a 23% decrease in overall doses of opiates (0.73 vs. 0.95; P = .02). Pain scores were similar between the two groups during hospital days 1-3 and improved in the intervention group between days 4 and 5.

This study was limited by a narrow focus, unblinded participants, and nursing-reported pain scores. While promising, more information is needed before establishing conclusions on a broader scale.

Bottom line: Establishing and promoting an opioid prescribing standard on a single unit led to a decrease in intravenous, parenteral, and overall opiates prescribed with similar or improved pain scores.

Citation: Ackerman AL et al. Association of an opioid standard of practice intervention with intravenous opioid exposure in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jun 1;178(6):759-63.

Dr. Chowdury is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of Colorado, Denver.

Clinical question: Can an opiate-prescribing standard that favors oral and subcutaneous over intravenous administration reduce exposure to intravenous opiates for hospitalized adults?

Background: IV opiates, while effective for analgesia, may have a higher addictive potential because of the rapid and intermittent rises of peak concentrations. Subcutaneous and/or oral administration is a proven method of opioid delivery with similar bioavailability and efficacy of intravenous administration with more favorable pharmacokinetics.

Study design: Intervention-based quality improvement project.

Setting: Adult general medicine inpatient unit in an urban academic center.

Synopsis: Clinical leadership of the study unit collaborated to create an opiate-prescribing standard recommending oral over parenteral opioids and subcutaneous over IV if parental administration was required. The standard was promoted and reinforced with prescriber and nurse education, and prescribers were able to order intravenous opiates per usual protocol.

After a 6-month preintervention control period of 4,500 patient-days, the 3-month intervention period included 2,459 patient-days and led to a 84% decrease in IV opiate doses (0.06 vs. 0.39; P less than .001) and a 55% decrease in parenteral doses (0.18 vs. 0.39; P less than .001). Surprisingly there was a 23% decrease in overall doses of opiates (0.73 vs. 0.95; P = .02). Pain scores were similar between the two groups during hospital days 1-3 and improved in the intervention group between days 4 and 5.

This study was limited by a narrow focus, unblinded participants, and nursing-reported pain scores. While promising, more information is needed before establishing conclusions on a broader scale.

Bottom line: Establishing and promoting an opioid prescribing standard on a single unit led to a decrease in intravenous, parenteral, and overall opiates prescribed with similar or improved pain scores.

Citation: Ackerman AL et al. Association of an opioid standard of practice intervention with intravenous opioid exposure in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jun 1;178(6):759-63.

Dr. Chowdury is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of Colorado, Denver.

Focus on patient experience to cut readmission rates

Incorporate patient-reported quality measures

Hospitalists have focused much attention on reducing 30-day readmission rates, at a time when 15-20% of health care dollars spent on those readmissions is considered potentially preventable.

But until very recently, no study has explored patient perceptions of the likelihood of readmission during index admission. Now, that’s changed.

“Our objective was to examine associations between patient perceptions of care during index hospital admission and 30-day readmission,” says Jocelyn Carter, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and lead author of November 2017 study in BMJ Quality & Safety.

Enrolled in the study were 846 patients at two inpatient adult medicine units at Massachusetts General, Boston; 201 (23.8%) of these patients were readmitted within 30 days. In multivariable models adjusting for baseline differences, respondents who reported being “very satisfied” with the care received during the index hospitalization were less likely to be readmitted; participants reporting that doctors “always listened to them carefully” also were less likely to be readmitted.

“These findings are important since they suggest that engaging patients in an assessment of communication quality, unmet needs, concerns, and overall experience during admission may help to identify issues that might not be captured in standard postdischarge surveys when the appropriate time for quality improvement interventions has passed,” Dr. Carter said. “Incorporating patient-reported measures during index hospitalizations may improve readmission rates and help predict which patients are more likely to be readmitted.”

Reference

Carter J et al. The association between patient experience factors and likelihood of 30-day readmission: A prospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf. 16 Nov 2017. Accessed Feb 2, 2018.

Incorporate patient-reported quality measures

Incorporate patient-reported quality measures

Hospitalists have focused much attention on reducing 30-day readmission rates, at a time when 15-20% of health care dollars spent on those readmissions is considered potentially preventable.

But until very recently, no study has explored patient perceptions of the likelihood of readmission during index admission. Now, that’s changed.

“Our objective was to examine associations between patient perceptions of care during index hospital admission and 30-day readmission,” says Jocelyn Carter, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and lead author of November 2017 study in BMJ Quality & Safety.

Enrolled in the study were 846 patients at two inpatient adult medicine units at Massachusetts General, Boston; 201 (23.8%) of these patients were readmitted within 30 days. In multivariable models adjusting for baseline differences, respondents who reported being “very satisfied” with the care received during the index hospitalization were less likely to be readmitted; participants reporting that doctors “always listened to them carefully” also were less likely to be readmitted.

“These findings are important since they suggest that engaging patients in an assessment of communication quality, unmet needs, concerns, and overall experience during admission may help to identify issues that might not be captured in standard postdischarge surveys when the appropriate time for quality improvement interventions has passed,” Dr. Carter said. “Incorporating patient-reported measures during index hospitalizations may improve readmission rates and help predict which patients are more likely to be readmitted.”

Reference

Carter J et al. The association between patient experience factors and likelihood of 30-day readmission: A prospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf. 16 Nov 2017. Accessed Feb 2, 2018.

Hospitalists have focused much attention on reducing 30-day readmission rates, at a time when 15-20% of health care dollars spent on those readmissions is considered potentially preventable.

But until very recently, no study has explored patient perceptions of the likelihood of readmission during index admission. Now, that’s changed.

“Our objective was to examine associations between patient perceptions of care during index hospital admission and 30-day readmission,” says Jocelyn Carter, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and lead author of November 2017 study in BMJ Quality & Safety.

Enrolled in the study were 846 patients at two inpatient adult medicine units at Massachusetts General, Boston; 201 (23.8%) of these patients were readmitted within 30 days. In multivariable models adjusting for baseline differences, respondents who reported being “very satisfied” with the care received during the index hospitalization were less likely to be readmitted; participants reporting that doctors “always listened to them carefully” also were less likely to be readmitted.

“These findings are important since they suggest that engaging patients in an assessment of communication quality, unmet needs, concerns, and overall experience during admission may help to identify issues that might not be captured in standard postdischarge surveys when the appropriate time for quality improvement interventions has passed,” Dr. Carter said. “Incorporating patient-reported measures during index hospitalizations may improve readmission rates and help predict which patients are more likely to be readmitted.”

Reference

Carter J et al. The association between patient experience factors and likelihood of 30-day readmission: A prospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf. 16 Nov 2017. Accessed Feb 2, 2018.

Launching a surgical comanagement project

Improving quality, patient satisfaction

When hospital medicine and surgical departments (usually orthopedics or neurosurgery) have joined in comanagement programs, improvements in quality metrics and patient satisfaction have often resulted.

At the Level 1 regional trauma center in which he works, Charles L. Kast, MD, and his colleagues wanted to try a comanagement agreement between hospital medicine and trauma surgery.

“The surgical team identified a need within their own department, which was to improve patient mortality and satisfaction in the inpatient setting,” said Dr. Kast, who is based at North Shore University Hospital, Manhasset, N.Y. “Their leadership sought out our hospital medicine leadership team, who then worked together to synthesize their metrics. We were able to identify other quality indicators, such as readmission rates and hospital-acquired conditions, which we felt could also benefit from our services in order to help them improve.”

Five hospitalists became members of the comanagement team. A single hospitalist rotated for 2 weeks at a time, during which they were relieved of routine hospital medicine rounding responsibilities. The hospitalist attended daily interdisciplinary rounds with the trauma surgery team, during which he/she identified patients that could benefit from hospital medicine comanagement: Patients who were over age 65 years, had multiple chronic medical conditions, or were on high-risk medications were preferentially selected. Approximately 10 patients were seen daily.

The comanagement program was well received by trauma surgeons, who talked about improved patient communication and a fostered sense of collegiality. Preliminary quality and patient satisfaction metrics were also positive.

A top takeaway is that the benefits of surgical comanagement can be demonstrated in “atypical” collaborations, depending on the needs of the department and the hospital’s vision.

“The gains in improved patient quality metrics are only half of the story,” Dr. Kast said. “Collaborating in surgical comanagement improves the satisfaction of the hospitalists and surgeons involved and can lead to future quality improvement projects or original research, both of which we are currently pursuing.”

Reference

Kast C et al. The successful development of a hospital medicine-trauma surgery co-management program [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(suppl 2). Accessed Feb. 2, 2018.

Improving quality, patient satisfaction

Improving quality, patient satisfaction

When hospital medicine and surgical departments (usually orthopedics or neurosurgery) have joined in comanagement programs, improvements in quality metrics and patient satisfaction have often resulted.

At the Level 1 regional trauma center in which he works, Charles L. Kast, MD, and his colleagues wanted to try a comanagement agreement between hospital medicine and trauma surgery.

“The surgical team identified a need within their own department, which was to improve patient mortality and satisfaction in the inpatient setting,” said Dr. Kast, who is based at North Shore University Hospital, Manhasset, N.Y. “Their leadership sought out our hospital medicine leadership team, who then worked together to synthesize their metrics. We were able to identify other quality indicators, such as readmission rates and hospital-acquired conditions, which we felt could also benefit from our services in order to help them improve.”

Five hospitalists became members of the comanagement team. A single hospitalist rotated for 2 weeks at a time, during which they were relieved of routine hospital medicine rounding responsibilities. The hospitalist attended daily interdisciplinary rounds with the trauma surgery team, during which he/she identified patients that could benefit from hospital medicine comanagement: Patients who were over age 65 years, had multiple chronic medical conditions, or were on high-risk medications were preferentially selected. Approximately 10 patients were seen daily.

The comanagement program was well received by trauma surgeons, who talked about improved patient communication and a fostered sense of collegiality. Preliminary quality and patient satisfaction metrics were also positive.

A top takeaway is that the benefits of surgical comanagement can be demonstrated in “atypical” collaborations, depending on the needs of the department and the hospital’s vision.

“The gains in improved patient quality metrics are only half of the story,” Dr. Kast said. “Collaborating in surgical comanagement improves the satisfaction of the hospitalists and surgeons involved and can lead to future quality improvement projects or original research, both of which we are currently pursuing.”

Reference

Kast C et al. The successful development of a hospital medicine-trauma surgery co-management program [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(suppl 2). Accessed Feb. 2, 2018.

When hospital medicine and surgical departments (usually orthopedics or neurosurgery) have joined in comanagement programs, improvements in quality metrics and patient satisfaction have often resulted.

At the Level 1 regional trauma center in which he works, Charles L. Kast, MD, and his colleagues wanted to try a comanagement agreement between hospital medicine and trauma surgery.

“The surgical team identified a need within their own department, which was to improve patient mortality and satisfaction in the inpatient setting,” said Dr. Kast, who is based at North Shore University Hospital, Manhasset, N.Y. “Their leadership sought out our hospital medicine leadership team, who then worked together to synthesize their metrics. We were able to identify other quality indicators, such as readmission rates and hospital-acquired conditions, which we felt could also benefit from our services in order to help them improve.”

Five hospitalists became members of the comanagement team. A single hospitalist rotated for 2 weeks at a time, during which they were relieved of routine hospital medicine rounding responsibilities. The hospitalist attended daily interdisciplinary rounds with the trauma surgery team, during which he/she identified patients that could benefit from hospital medicine comanagement: Patients who were over age 65 years, had multiple chronic medical conditions, or were on high-risk medications were preferentially selected. Approximately 10 patients were seen daily.

The comanagement program was well received by trauma surgeons, who talked about improved patient communication and a fostered sense of collegiality. Preliminary quality and patient satisfaction metrics were also positive.

A top takeaway is that the benefits of surgical comanagement can be demonstrated in “atypical” collaborations, depending on the needs of the department and the hospital’s vision.

“The gains in improved patient quality metrics are only half of the story,” Dr. Kast said. “Collaborating in surgical comanagement improves the satisfaction of the hospitalists and surgeons involved and can lead to future quality improvement projects or original research, both of which we are currently pursuing.”

Reference

Kast C et al. The successful development of a hospital medicine-trauma surgery co-management program [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(suppl 2). Accessed Feb. 2, 2018.

Paradigm shifts in palliative care

Better engagement with patients essential

A 57-year-old man is admitted to the hospital with new back pain, which has been getting worse over the past 6 days. He had been diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer in mid-2017 and underwent treatment with a platinum-based double therapy.

The man also has a history of heroin use – as recently as two years earlier – and he was divorced not long ago. He has been using an old prescription for Vicodin to treat himself, taking as many as 10-12 tablets a day.

This man is an example of the kind of complicated patient hospitalists are called on to treat – complex pain in an era when opioid abuse is considered a public scourge. How is a hospitalist to handle a case like this?

Pain cases are far from the only types of increasingly complex, often palliative cases in which hospitalists are being asked to provide help. Care for the elderly is also becoming increasingly difficult as the U.S. population ages and as hospitalists step in to provide care in the absence of geriatricians. .

Pain management in the opioid era and the need for new approaches in elderly care were highlighted at the Hospital Medicine 2018 annual conference, with experts drawing attention to subtleties that are often overlooked in these sometimes desperate cases.

James Risser, MD, medical director of palliative care at Regions Hospital in Minneapolis, said the complex problems of the 57-year-old man with back pain amounted to an example of “pain’s greatest hits.”

That particular case underscores the need to identify individual types of pain, he said, because they all need to be handled differently. If hospitalists don’t consider all the different aspects of pain, a patient might endure more suffering than necessary.

“All of this pain is swirling around in a very complicated patient,” Dr. Risser said, noting that it is important to “tease out the individual parts” of a complex patient’s history.

“Pain is a very complicated construct, from the physical to the neurological to the emotional,” Dr. Risser said. “Pain is a subjective experience, and the way people interact with their pain really depends not just on physical pain but also their psychological state, their social state, and even their spiritual state.”

Understanding this array of causes has led Dr. Risser to approach the problem of pain from different angles – including perspectives that might not be traditional, he said.

“One of the things that I’ve gotten better at is taking a spiritual history,” he said. “I don’t know if that’s part of everybody’s armamentarium. But if you’re dealing with people who are very, very sick, sometimes that’s the fundamental fabric of how they live and how they die. If there are unresolved issues along those lines, it’s possible they could be experiencing their pain in a different or more severe way.”

Varieties of pain

Treatment depends on the pain type, Dr. Risser said. Somatic pain often responds to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories or steroids.

Neuropathic pain usually responds poorly to anti-inflammatories and to opioids. There is some research suggesting methadone could be helpful, but the data are not very strong. The most common medications prescribed are antiseizure medications and antidepressants, such as gabapentin and serotonin, and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.

The question of cancer pain versus noncancer pain can be tricky, Dr. Risser said. If a person’s life expectancy is limited, there can be a reason, or even a requirement, to use higher-risk medications. But, he said, that doesn’t mean the patient still won’t have problems with overuse of pain medication.

“We have a lot of patients now living post cancer who have been put on methadone or have been put on Oxycontin, and now we’re trying to figure out what to do with them,” he said. “I don’t think it’s that clear anymore that there’s a massive difference between cancer and noncancer pain, especially for those survivors.”

Clinicians, he said, should “fix what can be fixed” – and with the right tools. “If you have a patient who’s got severe lower abdominal pain because they have a bladder full or urine, really the treatment would probably not be … opioids. It probably would be a Foley catheter,” he said.

Hospitalists should treat patients based on sound principles of pain management, Dr. Risser said, but “while you try to create a diagnostic framework, know that people continually defy the boxes we put them in.”

Indeed, in an era of pain-medication addiction, it might be a good idea to worry about prescribing opioids, but clinicians have to remember that their goal is to help patients get relief – and that they themselves bring biases to the table, said Amy Davis, DO, MS, of Drexel University, Philadelphia.

In a presentation at HM18, Dr. Davis displayed images of a variety of patients on a large screen – different races and genders, some in business attire, some rougher around the edges.

“Would pain decisions change based on what people look like?” she asked. “Can you really spot who the drug traffickers are? We need to remember that our biases play a huge role not only in the treatment of our patients but in their outcomes. I’m challenging everybody to start thinking about these folks not as drug-seekers but as comfort-seekers.”

When it comes right down to it, she said, patients want a better life, not their drug of choice.

“That is the nature of the disease. [The illegal drug] is not what they’re looking for in reality because that does not provide a good quality of life,” Dr. Davis said. “The [practice of medicine] is supposed to be about helping people live their lives, not just checking off boxes.”

People with an opioid use disorder are physically different, she said. The processing of pain stimuli by their brain and spinal cord is physically altered – they have an increased perception of pain and lower pain tolerance.

“This is not a character flaw,” Dr. Davis affirmed. The increased sensitivity to pain does not resolve with opioid cessation; it can last for decades. Clinicians may need to spend more time interacting with certain patients to get a sense of the physical and nonphysical pain from which they suffer.

“Consistent, open, nonjudgmental communication improves not only the information we gather from patients and families, but it actually changes the adherence,” Dr. Davis said. “Ultimately the treatment outcomes are what all of this is about.”

Paradigm shift

Another palliative care role that hospitalists often find themselves in is “comforter” of elderly patients.

Ryan Greysen, MD, MHS, chief of hospital medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said hospitals must respond to a shift in the paradigm of elderly care. To explain the nature of this change, he referenced the “paradigm shift” model devised by the philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn, PhD. According to Kuhn, science proceeds in a settled pattern for many years, but on the rare occasions, when there is a fundamental drift in thinking, new problems present themselves and put the old model in a crisis mode, which prompts an intellectual revolution and a shift in the paradigm itself.

“This is a way of thinking about changes in scientific paradigms, but I think it works in clinical practice as well,” Dr. Greysen said.

The need for a paradigm shift in the care of elderly inpatients has largely to do with demographics. By 2050, the number of people aged 65 years and older is expected to be about 80 million, roughly double what it was in 2000. The number of people aged 85 years and up is expected to be about 20 million, or about four times the total in 2000.

In 2010, 40% of the hospitalized population was over 65 years. In 2030, that will flip: Only 40% of inpatients will be under 65 years. This will mean that hospitalists must care for more patients who are older, and the patients themselves will have more complicated medical issues.

“To be ready for the aging century, we must be better able to adapt and address those things that affect seniors,” Dr. Greysen said. With the number of geriatricians falling, much more of this care will fall to hospitalists, he said.

More attention must be paid to the potential harms of hospital-based care to older patients: decreased muscle strength and aerobic capacity, vasomotor instability, lower bone density, poor ventilation, altered thirst and nutrition, and fragile skin, among others, Dr. Greysen said.

In a study published in 2015, Dr. Greysen assessed outcomes for elderly patients who were assessed before hospitalization for functional impairment. The more impaired they were, the more likely they were to be readmitted within 30 days of discharge – from a 13.5% readmission rate for those with no impairment up to 18.2% for those considered to have “dependency” in three or more activities of daily living.1

In another analysis, severe functional impairment – dependency in at least two activities of daily living – was associated with more post-acute care Medicare costs than neurological disorders or renal failure.2

Acute care for the elderly (ACE) programs, which have care specifically tailored to the needs of older patients, have been found to be associated with less functional decline, shorter lengths of stay, fewer adverse events, and lower costs and readmission rates, Dr. Greysen said.

These programs are becoming more common, but they are not spreading as quickly as perhaps they should, he said. In part, this is because of the “know-do” gap, in which practical steps that have been shown to work are not actually implemented because of assumptions that they are already in place or the mistaken belief that simple steps could not possibly make a difference.

Part of the paradigm shift that’s needed, Dr. Greysen said, is an appreciation of the concept of “posthospitalization syndrome,” which is composed of several domains: sleep, function, nutrition, symptom burden such as pain and discomfort, cognition, level of engagement, psychosocial status including emotional stress, and treatment burden including the adverse effects of medications.

Better patient engagement in discharge planning – including asking patients about whether they’ve had help reading hospital discharge–related documents, their level of education, and how often they are getting out of bed – is one necessary step toward change. Surveys of satisfaction using tablets and patient portals is another option, Dr. Greysen said.

The patients of the future will likely prompt their own change, he said, quoting from a 2013 publication.

“Possibly the most promising predictor for change in delivery of care is change in the patients themselves,” the authors wrote. “Baby boomers have redefined the norms at every stage of their lives. ... They will expect providers to engage them in shared decision making, elicit their health care goals and treatment preferences, communicate with providers across sites, and provide needed social supports.”3

References

1. Greysen SR et al. Functional impairment and hospital readmission in medicare seniors. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Apr;175(4):559-65.

2. Greysen SR et al. Functional impairment: An unmeasured marker of medicare costs for postacute care of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017 Sep;65(9):1996-2002.

3. Laura A. Levit, Erin P. Balogh, Sharyl J. Nass, and Patricia A. Ganz, eds. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. (Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), 2013 Dec 27).

Better engagement with patients essential

Better engagement with patients essential

A 57-year-old man is admitted to the hospital with new back pain, which has been getting worse over the past 6 days. He had been diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer in mid-2017 and underwent treatment with a platinum-based double therapy.

The man also has a history of heroin use – as recently as two years earlier – and he was divorced not long ago. He has been using an old prescription for Vicodin to treat himself, taking as many as 10-12 tablets a day.

This man is an example of the kind of complicated patient hospitalists are called on to treat – complex pain in an era when opioid abuse is considered a public scourge. How is a hospitalist to handle a case like this?

Pain cases are far from the only types of increasingly complex, often palliative cases in which hospitalists are being asked to provide help. Care for the elderly is also becoming increasingly difficult as the U.S. population ages and as hospitalists step in to provide care in the absence of geriatricians. .

Pain management in the opioid era and the need for new approaches in elderly care were highlighted at the Hospital Medicine 2018 annual conference, with experts drawing attention to subtleties that are often overlooked in these sometimes desperate cases.

James Risser, MD, medical director of palliative care at Regions Hospital in Minneapolis, said the complex problems of the 57-year-old man with back pain amounted to an example of “pain’s greatest hits.”

That particular case underscores the need to identify individual types of pain, he said, because they all need to be handled differently. If hospitalists don’t consider all the different aspects of pain, a patient might endure more suffering than necessary.

“All of this pain is swirling around in a very complicated patient,” Dr. Risser said, noting that it is important to “tease out the individual parts” of a complex patient’s history.

“Pain is a very complicated construct, from the physical to the neurological to the emotional,” Dr. Risser said. “Pain is a subjective experience, and the way people interact with their pain really depends not just on physical pain but also their psychological state, their social state, and even their spiritual state.”

Understanding this array of causes has led Dr. Risser to approach the problem of pain from different angles – including perspectives that might not be traditional, he said.

“One of the things that I’ve gotten better at is taking a spiritual history,” he said. “I don’t know if that’s part of everybody’s armamentarium. But if you’re dealing with people who are very, very sick, sometimes that’s the fundamental fabric of how they live and how they die. If there are unresolved issues along those lines, it’s possible they could be experiencing their pain in a different or more severe way.”

Varieties of pain

Treatment depends on the pain type, Dr. Risser said. Somatic pain often responds to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories or steroids.

Neuropathic pain usually responds poorly to anti-inflammatories and to opioids. There is some research suggesting methadone could be helpful, but the data are not very strong. The most common medications prescribed are antiseizure medications and antidepressants, such as gabapentin and serotonin, and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.

The question of cancer pain versus noncancer pain can be tricky, Dr. Risser said. If a person’s life expectancy is limited, there can be a reason, or even a requirement, to use higher-risk medications. But, he said, that doesn’t mean the patient still won’t have problems with overuse of pain medication.

“We have a lot of patients now living post cancer who have been put on methadone or have been put on Oxycontin, and now we’re trying to figure out what to do with them,” he said. “I don’t think it’s that clear anymore that there’s a massive difference between cancer and noncancer pain, especially for those survivors.”

Clinicians, he said, should “fix what can be fixed” – and with the right tools. “If you have a patient who’s got severe lower abdominal pain because they have a bladder full or urine, really the treatment would probably not be … opioids. It probably would be a Foley catheter,” he said.

Hospitalists should treat patients based on sound principles of pain management, Dr. Risser said, but “while you try to create a diagnostic framework, know that people continually defy the boxes we put them in.”

Indeed, in an era of pain-medication addiction, it might be a good idea to worry about prescribing opioids, but clinicians have to remember that their goal is to help patients get relief – and that they themselves bring biases to the table, said Amy Davis, DO, MS, of Drexel University, Philadelphia.

In a presentation at HM18, Dr. Davis displayed images of a variety of patients on a large screen – different races and genders, some in business attire, some rougher around the edges.

“Would pain decisions change based on what people look like?” she asked. “Can you really spot who the drug traffickers are? We need to remember that our biases play a huge role not only in the treatment of our patients but in their outcomes. I’m challenging everybody to start thinking about these folks not as drug-seekers but as comfort-seekers.”

When it comes right down to it, she said, patients want a better life, not their drug of choice.

“That is the nature of the disease. [The illegal drug] is not what they’re looking for in reality because that does not provide a good quality of life,” Dr. Davis said. “The [practice of medicine] is supposed to be about helping people live their lives, not just checking off boxes.”

People with an opioid use disorder are physically different, she said. The processing of pain stimuli by their brain and spinal cord is physically altered – they have an increased perception of pain and lower pain tolerance.

“This is not a character flaw,” Dr. Davis affirmed. The increased sensitivity to pain does not resolve with opioid cessation; it can last for decades. Clinicians may need to spend more time interacting with certain patients to get a sense of the physical and nonphysical pain from which they suffer.

“Consistent, open, nonjudgmental communication improves not only the information we gather from patients and families, but it actually changes the adherence,” Dr. Davis said. “Ultimately the treatment outcomes are what all of this is about.”

Paradigm shift

Another palliative care role that hospitalists often find themselves in is “comforter” of elderly patients.

Ryan Greysen, MD, MHS, chief of hospital medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said hospitals must respond to a shift in the paradigm of elderly care. To explain the nature of this change, he referenced the “paradigm shift” model devised by the philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn, PhD. According to Kuhn, science proceeds in a settled pattern for many years, but on the rare occasions, when there is a fundamental drift in thinking, new problems present themselves and put the old model in a crisis mode, which prompts an intellectual revolution and a shift in the paradigm itself.

“This is a way of thinking about changes in scientific paradigms, but I think it works in clinical practice as well,” Dr. Greysen said.

The need for a paradigm shift in the care of elderly inpatients has largely to do with demographics. By 2050, the number of people aged 65 years and older is expected to be about 80 million, roughly double what it was in 2000. The number of people aged 85 years and up is expected to be about 20 million, or about four times the total in 2000.

In 2010, 40% of the hospitalized population was over 65 years. In 2030, that will flip: Only 40% of inpatients will be under 65 years. This will mean that hospitalists must care for more patients who are older, and the patients themselves will have more complicated medical issues.

“To be ready for the aging century, we must be better able to adapt and address those things that affect seniors,” Dr. Greysen said. With the number of geriatricians falling, much more of this care will fall to hospitalists, he said.

More attention must be paid to the potential harms of hospital-based care to older patients: decreased muscle strength and aerobic capacity, vasomotor instability, lower bone density, poor ventilation, altered thirst and nutrition, and fragile skin, among others, Dr. Greysen said.

In a study published in 2015, Dr. Greysen assessed outcomes for elderly patients who were assessed before hospitalization for functional impairment. The more impaired they were, the more likely they were to be readmitted within 30 days of discharge – from a 13.5% readmission rate for those with no impairment up to 18.2% for those considered to have “dependency” in three or more activities of daily living.1

In another analysis, severe functional impairment – dependency in at least two activities of daily living – was associated with more post-acute care Medicare costs than neurological disorders or renal failure.2

Acute care for the elderly (ACE) programs, which have care specifically tailored to the needs of older patients, have been found to be associated with less functional decline, shorter lengths of stay, fewer adverse events, and lower costs and readmission rates, Dr. Greysen said.

These programs are becoming more common, but they are not spreading as quickly as perhaps they should, he said. In part, this is because of the “know-do” gap, in which practical steps that have been shown to work are not actually implemented because of assumptions that they are already in place or the mistaken belief that simple steps could not possibly make a difference.

Part of the paradigm shift that’s needed, Dr. Greysen said, is an appreciation of the concept of “posthospitalization syndrome,” which is composed of several domains: sleep, function, nutrition, symptom burden such as pain and discomfort, cognition, level of engagement, psychosocial status including emotional stress, and treatment burden including the adverse effects of medications.

Better patient engagement in discharge planning – including asking patients about whether they’ve had help reading hospital discharge–related documents, their level of education, and how often they are getting out of bed – is one necessary step toward change. Surveys of satisfaction using tablets and patient portals is another option, Dr. Greysen said.

The patients of the future will likely prompt their own change, he said, quoting from a 2013 publication.

“Possibly the most promising predictor for change in delivery of care is change in the patients themselves,” the authors wrote. “Baby boomers have redefined the norms at every stage of their lives. ... They will expect providers to engage them in shared decision making, elicit their health care goals and treatment preferences, communicate with providers across sites, and provide needed social supports.”3

References

1. Greysen SR et al. Functional impairment and hospital readmission in medicare seniors. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Apr;175(4):559-65.

2. Greysen SR et al. Functional impairment: An unmeasured marker of medicare costs for postacute care of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017 Sep;65(9):1996-2002.

3. Laura A. Levit, Erin P. Balogh, Sharyl J. Nass, and Patricia A. Ganz, eds. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. (Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), 2013 Dec 27).

A 57-year-old man is admitted to the hospital with new back pain, which has been getting worse over the past 6 days. He had been diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer in mid-2017 and underwent treatment with a platinum-based double therapy.

The man also has a history of heroin use – as recently as two years earlier – and he was divorced not long ago. He has been using an old prescription for Vicodin to treat himself, taking as many as 10-12 tablets a day.

This man is an example of the kind of complicated patient hospitalists are called on to treat – complex pain in an era when opioid abuse is considered a public scourge. How is a hospitalist to handle a case like this?

Pain cases are far from the only types of increasingly complex, often palliative cases in which hospitalists are being asked to provide help. Care for the elderly is also becoming increasingly difficult as the U.S. population ages and as hospitalists step in to provide care in the absence of geriatricians. .

Pain management in the opioid era and the need for new approaches in elderly care were highlighted at the Hospital Medicine 2018 annual conference, with experts drawing attention to subtleties that are often overlooked in these sometimes desperate cases.

James Risser, MD, medical director of palliative care at Regions Hospital in Minneapolis, said the complex problems of the 57-year-old man with back pain amounted to an example of “pain’s greatest hits.”

That particular case underscores the need to identify individual types of pain, he said, because they all need to be handled differently. If hospitalists don’t consider all the different aspects of pain, a patient might endure more suffering than necessary.

“All of this pain is swirling around in a very complicated patient,” Dr. Risser said, noting that it is important to “tease out the individual parts” of a complex patient’s history.

“Pain is a very complicated construct, from the physical to the neurological to the emotional,” Dr. Risser said. “Pain is a subjective experience, and the way people interact with their pain really depends not just on physical pain but also their psychological state, their social state, and even their spiritual state.”

Understanding this array of causes has led Dr. Risser to approach the problem of pain from different angles – including perspectives that might not be traditional, he said.

“One of the things that I’ve gotten better at is taking a spiritual history,” he said. “I don’t know if that’s part of everybody’s armamentarium. But if you’re dealing with people who are very, very sick, sometimes that’s the fundamental fabric of how they live and how they die. If there are unresolved issues along those lines, it’s possible they could be experiencing their pain in a different or more severe way.”

Varieties of pain

Treatment depends on the pain type, Dr. Risser said. Somatic pain often responds to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories or steroids.

Neuropathic pain usually responds poorly to anti-inflammatories and to opioids. There is some research suggesting methadone could be helpful, but the data are not very strong. The most common medications prescribed are antiseizure medications and antidepressants, such as gabapentin and serotonin, and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.

The question of cancer pain versus noncancer pain can be tricky, Dr. Risser said. If a person’s life expectancy is limited, there can be a reason, or even a requirement, to use higher-risk medications. But, he said, that doesn’t mean the patient still won’t have problems with overuse of pain medication.

“We have a lot of patients now living post cancer who have been put on methadone or have been put on Oxycontin, and now we’re trying to figure out what to do with them,” he said. “I don’t think it’s that clear anymore that there’s a massive difference between cancer and noncancer pain, especially for those survivors.”

Clinicians, he said, should “fix what can be fixed” – and with the right tools. “If you have a patient who’s got severe lower abdominal pain because they have a bladder full or urine, really the treatment would probably not be … opioids. It probably would be a Foley catheter,” he said.

Hospitalists should treat patients based on sound principles of pain management, Dr. Risser said, but “while you try to create a diagnostic framework, know that people continually defy the boxes we put them in.”

Indeed, in an era of pain-medication addiction, it might be a good idea to worry about prescribing opioids, but clinicians have to remember that their goal is to help patients get relief – and that they themselves bring biases to the table, said Amy Davis, DO, MS, of Drexel University, Philadelphia.

In a presentation at HM18, Dr. Davis displayed images of a variety of patients on a large screen – different races and genders, some in business attire, some rougher around the edges.

“Would pain decisions change based on what people look like?” she asked. “Can you really spot who the drug traffickers are? We need to remember that our biases play a huge role not only in the treatment of our patients but in their outcomes. I’m challenging everybody to start thinking about these folks not as drug-seekers but as comfort-seekers.”

When it comes right down to it, she said, patients want a better life, not their drug of choice.

“That is the nature of the disease. [The illegal drug] is not what they’re looking for in reality because that does not provide a good quality of life,” Dr. Davis said. “The [practice of medicine] is supposed to be about helping people live their lives, not just checking off boxes.”

People with an opioid use disorder are physically different, she said. The processing of pain stimuli by their brain and spinal cord is physically altered – they have an increased perception of pain and lower pain tolerance.

“This is not a character flaw,” Dr. Davis affirmed. The increased sensitivity to pain does not resolve with opioid cessation; it can last for decades. Clinicians may need to spend more time interacting with certain patients to get a sense of the physical and nonphysical pain from which they suffer.

“Consistent, open, nonjudgmental communication improves not only the information we gather from patients and families, but it actually changes the adherence,” Dr. Davis said. “Ultimately the treatment outcomes are what all of this is about.”

Paradigm shift

Another palliative care role that hospitalists often find themselves in is “comforter” of elderly patients.

Ryan Greysen, MD, MHS, chief of hospital medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said hospitals must respond to a shift in the paradigm of elderly care. To explain the nature of this change, he referenced the “paradigm shift” model devised by the philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn, PhD. According to Kuhn, science proceeds in a settled pattern for many years, but on the rare occasions, when there is a fundamental drift in thinking, new problems present themselves and put the old model in a crisis mode, which prompts an intellectual revolution and a shift in the paradigm itself.

“This is a way of thinking about changes in scientific paradigms, but I think it works in clinical practice as well,” Dr. Greysen said.

The need for a paradigm shift in the care of elderly inpatients has largely to do with demographics. By 2050, the number of people aged 65 years and older is expected to be about 80 million, roughly double what it was in 2000. The number of people aged 85 years and up is expected to be about 20 million, or about four times the total in 2000.

In 2010, 40% of the hospitalized population was over 65 years. In 2030, that will flip: Only 40% of inpatients will be under 65 years. This will mean that hospitalists must care for more patients who are older, and the patients themselves will have more complicated medical issues.

“To be ready for the aging century, we must be better able to adapt and address those things that affect seniors,” Dr. Greysen said. With the number of geriatricians falling, much more of this care will fall to hospitalists, he said.

More attention must be paid to the potential harms of hospital-based care to older patients: decreased muscle strength and aerobic capacity, vasomotor instability, lower bone density, poor ventilation, altered thirst and nutrition, and fragile skin, among others, Dr. Greysen said.

In a study published in 2015, Dr. Greysen assessed outcomes for elderly patients who were assessed before hospitalization for functional impairment. The more impaired they were, the more likely they were to be readmitted within 30 days of discharge – from a 13.5% readmission rate for those with no impairment up to 18.2% for those considered to have “dependency” in three or more activities of daily living.1

In another analysis, severe functional impairment – dependency in at least two activities of daily living – was associated with more post-acute care Medicare costs than neurological disorders or renal failure.2

Acute care for the elderly (ACE) programs, which have care specifically tailored to the needs of older patients, have been found to be associated with less functional decline, shorter lengths of stay, fewer adverse events, and lower costs and readmission rates, Dr. Greysen said.

These programs are becoming more common, but they are not spreading as quickly as perhaps they should, he said. In part, this is because of the “know-do” gap, in which practical steps that have been shown to work are not actually implemented because of assumptions that they are already in place or the mistaken belief that simple steps could not possibly make a difference.

Part of the paradigm shift that’s needed, Dr. Greysen said, is an appreciation of the concept of “posthospitalization syndrome,” which is composed of several domains: sleep, function, nutrition, symptom burden such as pain and discomfort, cognition, level of engagement, psychosocial status including emotional stress, and treatment burden including the adverse effects of medications.

Better patient engagement in discharge planning – including asking patients about whether they’ve had help reading hospital discharge–related documents, their level of education, and how often they are getting out of bed – is one necessary step toward change. Surveys of satisfaction using tablets and patient portals is another option, Dr. Greysen said.

The patients of the future will likely prompt their own change, he said, quoting from a 2013 publication.

“Possibly the most promising predictor for change in delivery of care is change in the patients themselves,” the authors wrote. “Baby boomers have redefined the norms at every stage of their lives. ... They will expect providers to engage them in shared decision making, elicit their health care goals and treatment preferences, communicate with providers across sites, and provide needed social supports.”3

References

1. Greysen SR et al. Functional impairment and hospital readmission in medicare seniors. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Apr;175(4):559-65.

2. Greysen SR et al. Functional impairment: An unmeasured marker of medicare costs for postacute care of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017 Sep;65(9):1996-2002.

3. Laura A. Levit, Erin P. Balogh, Sharyl J. Nass, and Patricia A. Ganz, eds. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. (Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), 2013 Dec 27).

Hospital-level care coordination strategies and the patient experience

Clinical question: Does patient experience correlate with specific hospital care coordination and transition strategies, and if so, which strategies most strongly correlate with higher patient experience scores?

Background: Patient experience is an increasingly important measure in value-based payment programs. However, progress has been slow in improving patient experience, and little empirical data exist regarding which strategies are effective. Care transitions are critical times during a hospitalization, with many hospitals already implementing measures to improve the discharge process and prevent readmission of patients. It is not known whether those measures also influence patient experience scores, and if they do improve scores, which measures are most effective at doing so.

Study design: An analytic observational survey design.

Setting: Hospitals eligible for the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) between June 2013 and December 2014.

Synopsis: A survey was developed and given to chief medical officers at 1,600 hospitals between June 2013 and December 2014; the survey assessed care coordination strategies employed by these institutions. 992 hospitals (62% response rate) were subsequently categorized as “low-strategy,” “mid-strategy,” or “high-strategy” hospitals. Patient satisfaction scores from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey in 2014 were correlated to the number of strategies and the specific strategies each hospital employed. In general, the higher-strategy hospitals had significantly higher HCAHPS survey scores than did low-strategy hospitals (+2.23 points; P less than .001). Specifically, creating and sharing a discharge summary prior to discharge (+1.43 points; P less than .001), using a discharge planner (+1.71 points; P less than .001), and calling patients 48 hours post discharge (+1.64 points; P less than .001) all resulted in overall higher hospital ratings by patients.

One limitation of this study is that no causal inference can be made between the specific strategies associated with higher HCAHPS scores and care coordination strategies.

Bottom line: Hospital-led care transition strategies with direct patient interactions led to higher patient satisfaction scores.

Citation: Figueroa JF et al. Hospital-level care coordination strategies associated with better patient experience. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018 Apr 4. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007597.

Dr. Tsien is a hospitalist in the division of hospital medicine in the department of medicine at Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill.

Clinical question: Does patient experience correlate with specific hospital care coordination and transition strategies, and if so, which strategies most strongly correlate with higher patient experience scores?

Background: Patient experience is an increasingly important measure in value-based payment programs. However, progress has been slow in improving patient experience, and little empirical data exist regarding which strategies are effective. Care transitions are critical times during a hospitalization, with many hospitals already implementing measures to improve the discharge process and prevent readmission of patients. It is not known whether those measures also influence patient experience scores, and if they do improve scores, which measures are most effective at doing so.

Study design: An analytic observational survey design.

Setting: Hospitals eligible for the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) between June 2013 and December 2014.

Synopsis: A survey was developed and given to chief medical officers at 1,600 hospitals between June 2013 and December 2014; the survey assessed care coordination strategies employed by these institutions. 992 hospitals (62% response rate) were subsequently categorized as “low-strategy,” “mid-strategy,” or “high-strategy” hospitals. Patient satisfaction scores from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey in 2014 were correlated to the number of strategies and the specific strategies each hospital employed. In general, the higher-strategy hospitals had significantly higher HCAHPS survey scores than did low-strategy hospitals (+2.23 points; P less than .001). Specifically, creating and sharing a discharge summary prior to discharge (+1.43 points; P less than .001), using a discharge planner (+1.71 points; P less than .001), and calling patients 48 hours post discharge (+1.64 points; P less than .001) all resulted in overall higher hospital ratings by patients.

One limitation of this study is that no causal inference can be made between the specific strategies associated with higher HCAHPS scores and care coordination strategies.

Bottom line: Hospital-led care transition strategies with direct patient interactions led to higher patient satisfaction scores.

Citation: Figueroa JF et al. Hospital-level care coordination strategies associated with better patient experience. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018 Apr 4. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007597.

Dr. Tsien is a hospitalist in the division of hospital medicine in the department of medicine at Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill.

Clinical question: Does patient experience correlate with specific hospital care coordination and transition strategies, and if so, which strategies most strongly correlate with higher patient experience scores?

Background: Patient experience is an increasingly important measure in value-based payment programs. However, progress has been slow in improving patient experience, and little empirical data exist regarding which strategies are effective. Care transitions are critical times during a hospitalization, with many hospitals already implementing measures to improve the discharge process and prevent readmission of patients. It is not known whether those measures also influence patient experience scores, and if they do improve scores, which measures are most effective at doing so.

Study design: An analytic observational survey design.

Setting: Hospitals eligible for the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) between June 2013 and December 2014.

Synopsis: A survey was developed and given to chief medical officers at 1,600 hospitals between June 2013 and December 2014; the survey assessed care coordination strategies employed by these institutions. 992 hospitals (62% response rate) were subsequently categorized as “low-strategy,” “mid-strategy,” or “high-strategy” hospitals. Patient satisfaction scores from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey in 2014 were correlated to the number of strategies and the specific strategies each hospital employed. In general, the higher-strategy hospitals had significantly higher HCAHPS survey scores than did low-strategy hospitals (+2.23 points; P less than .001). Specifically, creating and sharing a discharge summary prior to discharge (+1.43 points; P less than .001), using a discharge planner (+1.71 points; P less than .001), and calling patients 48 hours post discharge (+1.64 points; P less than .001) all resulted in overall higher hospital ratings by patients.

One limitation of this study is that no causal inference can be made between the specific strategies associated with higher HCAHPS scores and care coordination strategies.

Bottom line: Hospital-led care transition strategies with direct patient interactions led to higher patient satisfaction scores.

Citation: Figueroa JF et al. Hospital-level care coordination strategies associated with better patient experience. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018 Apr 4. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007597.

Dr. Tsien is a hospitalist in the division of hospital medicine in the department of medicine at Loyola University Chicago, Maywood, Ill.

Does nurse-physician rounding matter?

Advancing the Quadruple Aim

Inadequate and fragmented communication between physicians and nurses can lead to unwelcome events for the hospitalized patient and clinicians. Missing orders, medication errors, patient misidentification, and lack of physician awareness of significant changes in patient status are just some examples of how deficits in formal communication can affect health outcomes during acute stays.

A 2000 Institute of Medicine report showed that bad systems, not bad people, account for the majority of errors and injuries caused by complexity, professional fragmentation, and barriers in communication. Their recommendation was to train physicians, nurses, and other professionals in teamwork.1,2 However, as Milisa Manojlovich, PhD, RN, found, there are significant differences in how physicians and nurses perceive collaboration and communication.3

Nurse-physician rounding was historically standard for patient care during hospitalization. When physicians split time between inpatient and outpatient care, nurses had to maximize their time to collaborate and communicate with physicians whenever the physicians left their outpatient offices to come and round on their patients. Today most inpatient care is delivered by hospitalists on a 24-hour basis. This continuous availability of physicians reduces the perceived need to have joint rounds.

However, health care teams in acute care facilities now face higher and sicker patient volumes, different productivity models and demands, new compliance standards, changing work flows, and increased complexity of treatment and management of patients. This has led to gaps in timely communication and partnership.4-6 Erosion of the traditional nurse-physician relationships affects the quality of patient care, the patient’s experience, and patient safety.8-10 Poor communication among health care team members is one of the most common causes of patient care errors.4 Poor nurse-physician communication can also lead to medical errors, poor outcomes caused by lack of coordination within the treatment team, increased use of unnecessary resources with inefficiency, and increases in the complexity of communication among team members, and time wastage.5,7,11 All these lead to poor work flows and directly affect patient safety.7

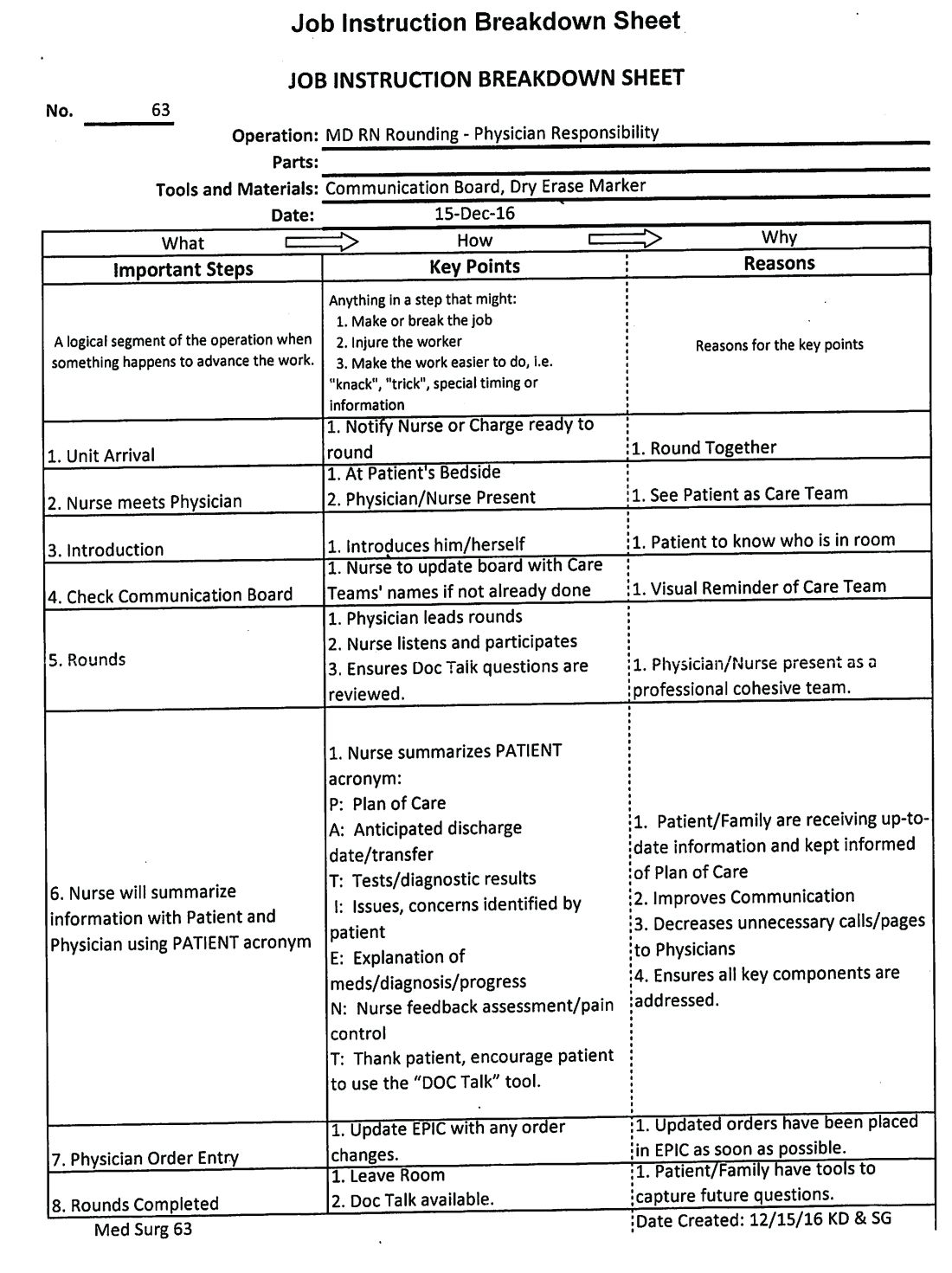

At Lee Health System in Lee County, Fla., we saw an opportunity in this changing health care environment to promote nurse-physician rounding. We created a structured, standardized process for morning rounding and engaged unit clerks, nursing leadership, and hospitalist service line leaders. We envisioned improvement of the patient experience, nurse-physician relationship, quality of care, the discharge planning process, and efficiency, as well as decreasing length of stay, improving communication, and bringing the patient and the treatment team closer, as demonstrated by Bradley Monash, MD, et al.12

Some data suggest that patient-centered bedside rounds on hospitalized patients have no effect on patient perceptions or their satisfaction with care.13 However, we felt that collaboration among a multidisciplinary team would help us achieve better outcomes. For example, our patients would perceive the care team (MD-RN) as a cohesive unit, and in turn gain trust in the members of the treatment team, as found by Nathalie McIntosh, PhD, et al and by Jason Ramirez, MD.7,16 Our vision was to empower nurses to be advocates for patients and their family members as they navigated their acute care admission. Nurses could also support physicians by communicating the physicians’ care plans to families and patients. After rounding with the physician, the nurse would be part of the decision-making process and care planning.17

Every rounding session had discharge planning and hospital stay expectations that were shared with the patient and nurse, who could then partner with case managers and social workers, which would streamline and reduce length of stay.14 We hoped rounding would also decrease the number of nurse pages to clarify or question orders. This would, in turn, improve daily work flow for the physicians and the nursing team with improvements in employee satisfaction scores.15 A study also has demonstrated a reduction in readmission rates from nurse-physician rounding.19

A disconnect in communication and trust between physicians and the nursing staff was reflected in low patient experience scores and perceived quality of care received during in-hospital stay. Gwendolyn Lancaster, EdD, MSN, RN, CCRN, et al, as well as a Joint Commission report, demonstrated how a lack of communication and poor team dynamics can translate to poor patient experience and be a major cause for sentinel events.6,20 Artificial, forced hierarchies and role perception among health care team members led to frustration, hostility, and distrust, which compromises quality and patient safety.1

One of our biggest challenges when we started this project was explaining the “Why” to the hospitalist group and nursing staff. Physicians were used to being the dominant partner in the team. Partnering with and engaging nurses in shared decision making and care planning was a seismic shift in culture and work flow within the care team. Early gains helped skeptical team members begin to understand the value in nurse-physician rounding. Near universal adoption of the rounding process at Lee Health has caused improvements in the working relationship and trust among the health care professionals. We have seen improvements in utilization management, as well as appropriateness and timeliness of resource use, because of better communication and understanding of care plans by nursing and physicians. Collaboration with specialists and alignment in care planning are other gains. Hospitalists and nurses are both very satisfied with the decrease in the number of pages during the day, and this has lowered stressors on health care teams.

How we did it

Nurse-physician rounding is a proven method to improve collaboration, communication, and relationships among health care team members in acute care facilities. In the complex health care challenges faced today, this improved work flow for taking care of patients can help advance the Quadruple Aim of high quality, low cost, improved patient experience, physician, and staff satisfaction.21

Lee Health System includes four facilities in Lee County, with a total of 1,216 licensed adult acute care beds. The pilot project was started in 2014.

Initially the vice president of nursing and the hospitalist medical director met to create an education plan for nurses and physicians. We chose one adult medicine unit to pilot the project because there already existed a closely knit nursing and hospitalist team. In our facility there is no strict geographical rounding; each hospitalist carries between three and six patients in the unit. As a first step, a nurse floor assignment sheet was faxed in the morning to the hospitalist office with the direct phone numbers of the nurses. The unit clerk, using physician assignments in the EHR, teamed up the physician and nurses for rounding. Once the physician arrived at the unit, he or she checked in with the unit clerk, who alerted nurses that the hospitalist was available on the floor to commence rounding. If the primary nurse was unavailable because of other duties or breaks, the charge nurse rounded with the physician.

Once in the room with the patient, the duo introduced themselves as members of the treatment team and acknowledged the patient’s needs. During the visit, care plans and treatment were reviewed, the patient’s questions were answered, a physical exam was completed, and lab and imaging results were discussed; the nurse also helped raise questions he or she had received from family members so answers could be communicated to the family later. Patients appreciated knowing that their physicians and nurses were working together as a team for their safety and recovery. During the visit, care was taken to focus specially on the course of hospitalization and discharge planning.

We tracked the rounding with a manual paper process maintained by the charge nurse. Our initial rounding rates were 30%-40%, and we continued to promote this initiative to the team, and eventually the importance and value of these rounds caught on with both nurses and physicians, and now our current average rounding rate is 90%. We then decided to scale this to all units in the hospital.

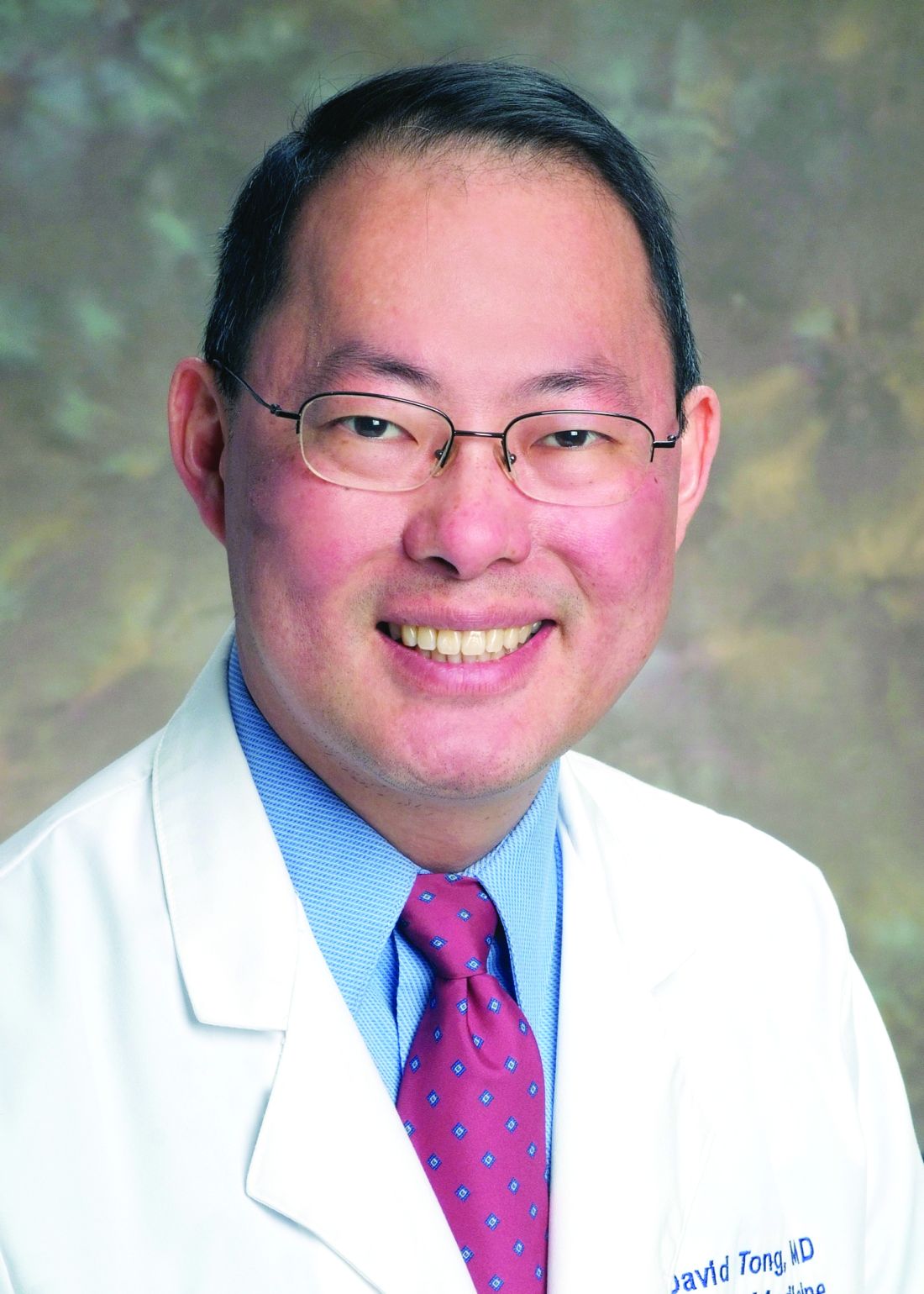

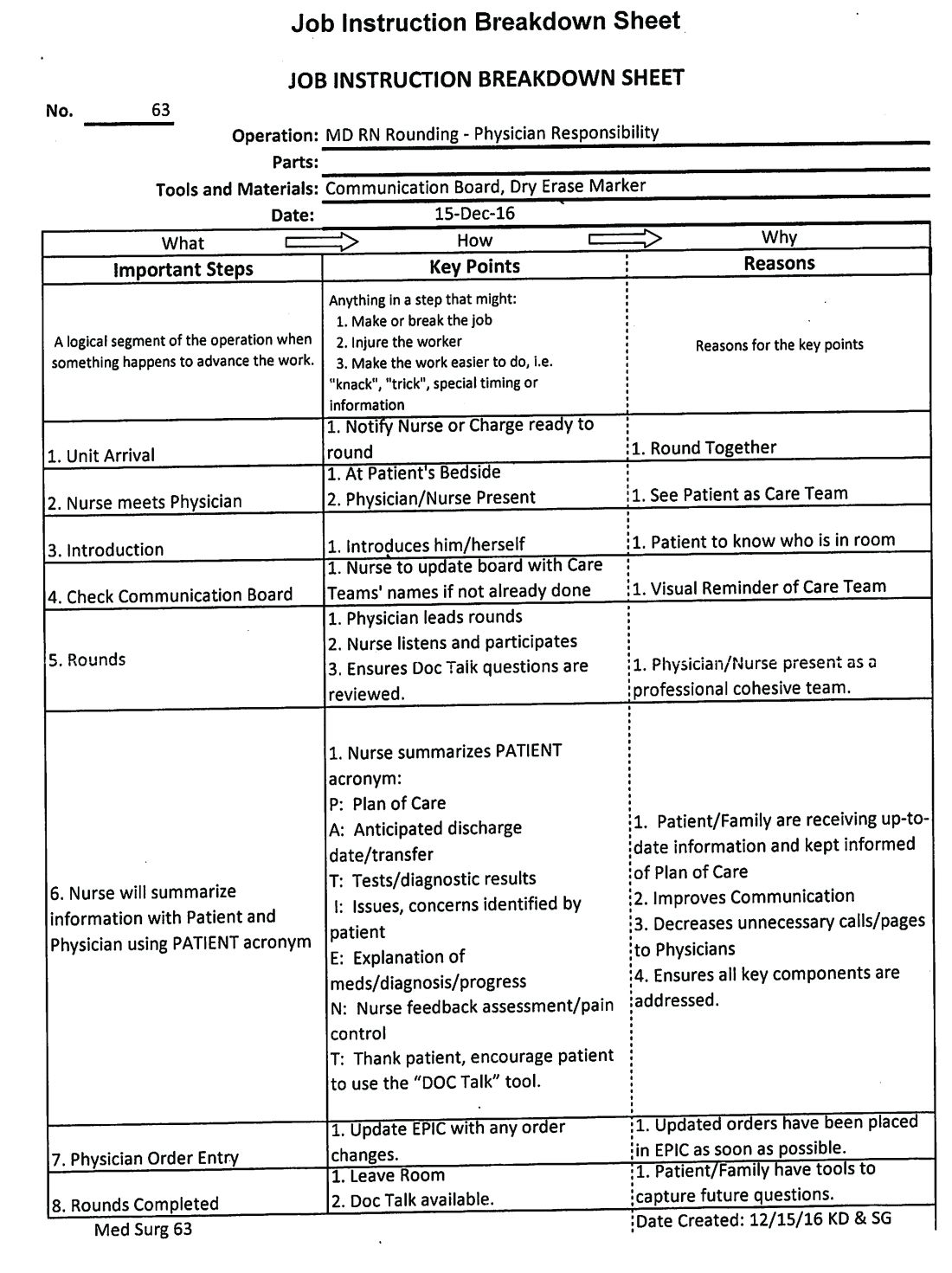

This process was repeated at other hospitals in the system once a standardized work flow was created (See Image 1). This initiative was next presented to the health system board of directors, who agreed that nurse-physician rounding should be the standard of care across our health system. Through partnership and collaboration with the IT department, we developed a tool to track nurse-physician rounding through our EHR system, which gave accountability to both physicians and nurses.

In conclusion, improved communication by timely nurse-physician rounding can lead to better outcomes for patients and also reduce costs and improve patient and staff experience, advancing the Quadruple Aim. Moving forward to build and sustain this work flow, we plan to continue nurse-physician collaboration across the health system consistently and for all areas of acute care operations.

Explaining the “Why,” sharing data on the benefits of the model, and reinforcing documentation of the rounding in our EHR are some steps we have put into action at leadership and staff meetings to sustain the activity. We are soliciting feedback, as well as monitoring and identifying any unaddressed barriers during rounding. Addition of this process measure to our quality improvement bonus opportunity also has helped to sustain performance from our teams.

Dr. Laufer is system medical director of hospital medicine and transitional care at Lee Health in Ft. Myers, Fla. Dr. Prasad is chief medical officer of Lee Physician Group, Ft. Myers, Fla.

References

1. Leape LL et al. Five years after to err is human: What we have learned? JAMA. 2005;293(19):2384-90.

2. Sutcliffe KM et al. Communication failures: An insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):186-94.

3. Manojlovich M. Reframing communication with physicians as sensemaking. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013 Oct-Dec;28(4):295-303.

4. Siegele P. Enhancing outcomes in a surgical intensive care unit by implementing daily goals. Crit Care Nurse. 2009 Dec;29(6):58-69.

5. Asthon J et al. Qualitative evaluation of regular morning meeting aimed at improving interdisciplinary communication and patient outcomes. Int J Nurs Pract. 2005 Oct;11(5):206-13.

6. Lancaster G et al. Interdisciplinary Communication and collaboration among physicians, nurses, and unlicensed assistive personnel. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2015 May;47(3):275-84.

7. McIntosh N et al. Impact of provider coordination on nurse and physician perception of patient care quality. J Nurs Care Qual. 2014 Jul-Sep;29(3):269-79.

8. Jo M et al. An organizational assessment of disruptive clinical behavior. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013 Apr-Jun;28(2):110-21.

9. World Health Organization. Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. Geneva, 2010.

10. O’Connor P et al. A mixed-methods study of the causes and impact of poor teamwork between junior doctors and nurses. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016 Jun;28(3):339-45.

11. Manojlovich M. Nurse/Physician communication through a sense making lens. Med Care. 2010 Nov;48(11):941-6.

12. Monash B et al. Standardized attending rounds to improve the patient experience: A pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. J Hosp Med. 2017 Mar;12(3):143-9.

13. O’Leary KJ et al. Effect of patient-centered bedside rounds on hospitalized patients decision control, activation and satisfaction with care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016 Dec;25(12):921-8.

14. Dutton RP et al. Daily multidisciplinary rounds shorten length of stay for trauma patients. J Trauma. 2003 Nov;55(5):913-9.

15. Manojlovich M et al. Healthy work environments, nurse-physician communication, and patients’ outcomes. Am J Crit Care. 2007 Nov;16(6):536-43.

16. Ramirez J et al. Patient satisfaction with bedside teaching rounds compared with nonbedside rounds. South Med J. 2016 Feb;109(2):112-5.

17. Sollami A et al. Nurse-Physician collaboration: A meta-analytical investigation of survey scores. J Interprof Care. 2015 May;29(3):223-9.

18. House S et al. Nurses and physicians perceptions of nurse-physician collaboration. J Nurs Adm. 2017 Mar;47(3):165-71.

19. Townsend-Gervis M et al. Interdisciplinary rounds and structured communications reduce re-admissions and improve some patients’ outcomes. West J Nurs Res. 2014 Aug;36(7):917-28.

20. The Joint Commission. Sentinel Events. http://www.jointcommission.org/sentinel_event.aspx. Accessed Oct 2017.

21. Bodenheimer T et al. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014 Nov-Dec;12(6):573-6.

Advancing the Quadruple Aim

Advancing the Quadruple Aim

Inadequate and fragmented communication between physicians and nurses can lead to unwelcome events for the hospitalized patient and clinicians. Missing orders, medication errors, patient misidentification, and lack of physician awareness of significant changes in patient status are just some examples of how deficits in formal communication can affect health outcomes during acute stays.

A 2000 Institute of Medicine report showed that bad systems, not bad people, account for the majority of errors and injuries caused by complexity, professional fragmentation, and barriers in communication. Their recommendation was to train physicians, nurses, and other professionals in teamwork.1,2 However, as Milisa Manojlovich, PhD, RN, found, there are significant differences in how physicians and nurses perceive collaboration and communication.3

Nurse-physician rounding was historically standard for patient care during hospitalization. When physicians split time between inpatient and outpatient care, nurses had to maximize their time to collaborate and communicate with physicians whenever the physicians left their outpatient offices to come and round on their patients. Today most inpatient care is delivered by hospitalists on a 24-hour basis. This continuous availability of physicians reduces the perceived need to have joint rounds.

However, health care teams in acute care facilities now face higher and sicker patient volumes, different productivity models and demands, new compliance standards, changing work flows, and increased complexity of treatment and management of patients. This has led to gaps in timely communication and partnership.4-6 Erosion of the traditional nurse-physician relationships affects the quality of patient care, the patient’s experience, and patient safety.8-10 Poor communication among health care team members is one of the most common causes of patient care errors.4 Poor nurse-physician communication can also lead to medical errors, poor outcomes caused by lack of coordination within the treatment team, increased use of unnecessary resources with inefficiency, and increases in the complexity of communication among team members, and time wastage.5,7,11 All these lead to poor work flows and directly affect patient safety.7

At Lee Health System in Lee County, Fla., we saw an opportunity in this changing health care environment to promote nurse-physician rounding. We created a structured, standardized process for morning rounding and engaged unit clerks, nursing leadership, and hospitalist service line leaders. We envisioned improvement of the patient experience, nurse-physician relationship, quality of care, the discharge planning process, and efficiency, as well as decreasing length of stay, improving communication, and bringing the patient and the treatment team closer, as demonstrated by Bradley Monash, MD, et al.12