User login

Clinical Challenge

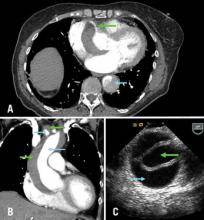

Images courtesy Dr. Michael Davidson

A) Axial CT chest at level of aortic root: green arrow = right coronary artery filling from true lumen, traversing false lumen; blue arrow = dissection in descending thoracic aorta; B) CT chest coronal reconstruction; blue arrows = true lumen in ascending aorta and innominate artery opacified with intravenous contrast; green arrows = false lumen; C) Transesophageal echocardiography of ascending aorta; green arrow= true lumen, blue arrow = false lumen.

BTX

A 71-year-old female with known ascending aortic aneurysm previously 4.5 cm presents to the emergency room with sharp chest pain of acute onset radiating to her back. She has diminished right radial and left femoral pulses. Chest x-ray shows a moderately widened mediastinum. Representative images are shown from the computed tomography of chest with contrast and a transesophageal echo with views of the ascending aorta.

Directed questions:

1. What is the diagnosis?

2. What are the two most common classification systems of this disease process?

3. What is the mortality associated with this diagnosis?

4. What is the best method of diagnosis in a stable patient? In an unstable patient?

5. What is the recommended treatment strategy?

6. What options are available for arterial cannulation?

Answers to the Clinical Challenge

1) Acute Aortic dissection of the ascending aorta, aortic arch and descending aorta

2) Stanford system (A=ascending arch, B=descending arch), Debakey system (I=ascending, arch and descending aorta, II - ascending aorta only, III - descending aorta only)

3) An acute type A dissection has been classically described as having a mortality of 1% per hour. Common causes of death are aortic free rupture, pericardial tamponade, acute aortic regurgitation, acute myocardial ischemia from coronary malperfusion.

4) In a stable patient, computed tomography with intravenous contrast is best due its ease and a sensitivity and a specificity nearing 90-100%. In unstable patients transesophageal echocardiography in the operating room is an excellent strategy for diagnosis to avoid delay in definitive surgical repair.

5) Initial medical management is aimed at control of blood pressure and pain. Esmolol and nitroprusside are good options. Unstable patients belong in the operating room and all delays should be avoided. Surgical repair is indicated in nearly all type A acute aortic dissections except maybe in the highest risk patients. At surgery, the ascending aorta, the aortic root, aortic valve, coronary arteries, aortic arch and arch vessels must all be assessed and repaired or replaced as necessary. As dissections frequently will extend into the arch, a short period of deep hypothermic circulatory arrest is common.

6) Most commonly, peripheral arterial cannulation is performed via the femoral or axillary artery. Care must be taken if dissection into the peripheral vessels is suspected. The ascending aorta may be cannulated but one must ensure perfusion through the true lumen. Transapical cannulation has been described as well. Transesophageal echocardiography can be used to guide cannulation placement into the ascending aorta.

Selected References and Additional Resources:

Bolman, R. Acute Type A Aortic Dissection. Operative Techniques in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 14(2):124, 2009.

Coady MA, et al. Natural history, pathogenesis, and etiology of thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections. Cardiology Clinics. 17:615, 1999.

Sabik JF, et al: Long-term effectiveness of operations for ascending aortic dissections. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 119:946, 2000.

Safi HJ, Miller CC 3rd, Reardon MJ, et al: Operation for acute and chronic aortic dissection: Recent outcome with regard to neurologic deficit and early death. Ann Thorac Surg 1998; 66:402

TSDAWeekly Curriculum - "Acute Aortic Dissection" http://tsda.org/documents/PDF/Weekly%20Curricula/E-mail%20Archive/03.11.10.pdf

Images courtesy Dr. Michael Davidson

A) Axial CT chest at level of aortic root: green arrow = right coronary artery filling from true lumen, traversing false lumen; blue arrow = dissection in descending thoracic aorta; B) CT chest coronal reconstruction; blue arrows = true lumen in ascending aorta and innominate artery opacified with intravenous contrast; green arrows = false lumen; C) Transesophageal echocardiography of ascending aorta; green arrow= true lumen, blue arrow = false lumen.

BTX

A 71-year-old female with known ascending aortic aneurysm previously 4.5 cm presents to the emergency room with sharp chest pain of acute onset radiating to her back. She has diminished right radial and left femoral pulses. Chest x-ray shows a moderately widened mediastinum. Representative images are shown from the computed tomography of chest with contrast and a transesophageal echo with views of the ascending aorta.

Directed questions:

1. What is the diagnosis?

2. What are the two most common classification systems of this disease process?

3. What is the mortality associated with this diagnosis?

4. What is the best method of diagnosis in a stable patient? In an unstable patient?

5. What is the recommended treatment strategy?

6. What options are available for arterial cannulation?

Answers to the Clinical Challenge

1) Acute Aortic dissection of the ascending aorta, aortic arch and descending aorta

2) Stanford system (A=ascending arch, B=descending arch), Debakey system (I=ascending, arch and descending aorta, II - ascending aorta only, III - descending aorta only)

3) An acute type A dissection has been classically described as having a mortality of 1% per hour. Common causes of death are aortic free rupture, pericardial tamponade, acute aortic regurgitation, acute myocardial ischemia from coronary malperfusion.

4) In a stable patient, computed tomography with intravenous contrast is best due its ease and a sensitivity and a specificity nearing 90-100%. In unstable patients transesophageal echocardiography in the operating room is an excellent strategy for diagnosis to avoid delay in definitive surgical repair.

5) Initial medical management is aimed at control of blood pressure and pain. Esmolol and nitroprusside are good options. Unstable patients belong in the operating room and all delays should be avoided. Surgical repair is indicated in nearly all type A acute aortic dissections except maybe in the highest risk patients. At surgery, the ascending aorta, the aortic root, aortic valve, coronary arteries, aortic arch and arch vessels must all be assessed and repaired or replaced as necessary. As dissections frequently will extend into the arch, a short period of deep hypothermic circulatory arrest is common.

6) Most commonly, peripheral arterial cannulation is performed via the femoral or axillary artery. Care must be taken if dissection into the peripheral vessels is suspected. The ascending aorta may be cannulated but one must ensure perfusion through the true lumen. Transapical cannulation has been described as well. Transesophageal echocardiography can be used to guide cannulation placement into the ascending aorta.

Selected References and Additional Resources:

Bolman, R. Acute Type A Aortic Dissection. Operative Techniques in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 14(2):124, 2009.

Coady MA, et al. Natural history, pathogenesis, and etiology of thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections. Cardiology Clinics. 17:615, 1999.

Sabik JF, et al: Long-term effectiveness of operations for ascending aortic dissections. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 119:946, 2000.

Safi HJ, Miller CC 3rd, Reardon MJ, et al: Operation for acute and chronic aortic dissection: Recent outcome with regard to neurologic deficit and early death. Ann Thorac Surg 1998; 66:402

TSDAWeekly Curriculum - "Acute Aortic Dissection" http://tsda.org/documents/PDF/Weekly%20Curricula/E-mail%20Archive/03.11.10.pdf

Images courtesy Dr. Michael Davidson

A) Axial CT chest at level of aortic root: green arrow = right coronary artery filling from true lumen, traversing false lumen; blue arrow = dissection in descending thoracic aorta; B) CT chest coronal reconstruction; blue arrows = true lumen in ascending aorta and innominate artery opacified with intravenous contrast; green arrows = false lumen; C) Transesophageal echocardiography of ascending aorta; green arrow= true lumen, blue arrow = false lumen.

BTX

A 71-year-old female with known ascending aortic aneurysm previously 4.5 cm presents to the emergency room with sharp chest pain of acute onset radiating to her back. She has diminished right radial and left femoral pulses. Chest x-ray shows a moderately widened mediastinum. Representative images are shown from the computed tomography of chest with contrast and a transesophageal echo with views of the ascending aorta.

Directed questions:

1. What is the diagnosis?

2. What are the two most common classification systems of this disease process?

3. What is the mortality associated with this diagnosis?

4. What is the best method of diagnosis in a stable patient? In an unstable patient?

5. What is the recommended treatment strategy?

6. What options are available for arterial cannulation?

Answers to the Clinical Challenge

1) Acute Aortic dissection of the ascending aorta, aortic arch and descending aorta

2) Stanford system (A=ascending arch, B=descending arch), Debakey system (I=ascending, arch and descending aorta, II - ascending aorta only, III - descending aorta only)

3) An acute type A dissection has been classically described as having a mortality of 1% per hour. Common causes of death are aortic free rupture, pericardial tamponade, acute aortic regurgitation, acute myocardial ischemia from coronary malperfusion.

4) In a stable patient, computed tomography with intravenous contrast is best due its ease and a sensitivity and a specificity nearing 90-100%. In unstable patients transesophageal echocardiography in the operating room is an excellent strategy for diagnosis to avoid delay in definitive surgical repair.

5) Initial medical management is aimed at control of blood pressure and pain. Esmolol and nitroprusside are good options. Unstable patients belong in the operating room and all delays should be avoided. Surgical repair is indicated in nearly all type A acute aortic dissections except maybe in the highest risk patients. At surgery, the ascending aorta, the aortic root, aortic valve, coronary arteries, aortic arch and arch vessels must all be assessed and repaired or replaced as necessary. As dissections frequently will extend into the arch, a short period of deep hypothermic circulatory arrest is common.

6) Most commonly, peripheral arterial cannulation is performed via the femoral or axillary artery. Care must be taken if dissection into the peripheral vessels is suspected. The ascending aorta may be cannulated but one must ensure perfusion through the true lumen. Transapical cannulation has been described as well. Transesophageal echocardiography can be used to guide cannulation placement into the ascending aorta.

Selected References and Additional Resources:

Bolman, R. Acute Type A Aortic Dissection. Operative Techniques in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 14(2):124, 2009.

Coady MA, et al. Natural history, pathogenesis, and etiology of thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections. Cardiology Clinics. 17:615, 1999.

Sabik JF, et al: Long-term effectiveness of operations for ascending aortic dissections. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 119:946, 2000.

Safi HJ, Miller CC 3rd, Reardon MJ, et al: Operation for acute and chronic aortic dissection: Recent outcome with regard to neurologic deficit and early death. Ann Thorac Surg 1998; 66:402

TSDAWeekly Curriculum - "Acute Aortic Dissection" http://tsda.org/documents/PDF/Weekly%20Curricula/E-mail%20Archive/03.11.10.pdf

New Cardiothoracic Safety Reporting for 'Near Misses'

Many residents are unaware that a near miss reporting site for cardiothoracic surgery exists, the Cardiothoracic Safety Reporting System. This system, available through the CTSNet website (http://ctsrs.ctsnet.org/) allows anyone with a CTSNet login to submit descriptions of near misses and review the near misses others have submitted, ranging from labeling errors to a case of an ascending aortic graft igniting during a Bentall procedure.

By way of background, it has been estimated that about 100,000 people die avoidable deaths annually in U.S. hospitals, and many more incur injuries to the tune of an annual cost of approximately $9 billion; this exceeds the combined number of deaths and injuries from automobile and airplane crashes, suicides, poisonings, drownings and falls annually (BMJ 2000; 320(7237): 759-63). To reduce this number of errors requires learning not only from the times harm resulted to patients from errors, but also the cases where an error occurred but negative consequences were averted, a “near miss.”

As surgeons, we are accustomed to the discussion of our errors in regular morbidity and mortality conferences. Conferences such as these are invaluable for learning and practice improvement, but are limited in that they focus on actual adverse events, with near-misses rarely discussed. And, since only the participants present at the conferences learn the lessons to be gleaned from these events, the impact of conferences such as this are narrow.

In other disciplines, industry-wide schemes for reporting “close calls,” near misses, or sentinel (“warning”) events have been created. The near-miss reporting system in aviation, the Aviation Reporting Safety System (http://asrs.arc.nasa.gov/), is well-known, but similar systems are in place in the nuclear power industry, the military, petrochemical processing and steel production, high-reliability organizations which function in “high consequence” environments (www.ctsnet.org/sections/newsandviews/specialreports/article-10.html).

With these examples in mind, in 2007 the STS's Workforce for Patient Safety, at the time under the leadership of Dr. Thor Sundt, created the Cardiothoracic Safety Reporting System. Dr. Sundt, Dr. Marshall Blair, the current chair of the Workforce, and Dr. Emile Bacha, who was involved in the early planning and discussion of this project, recently approached the Thoracic Surgery Residents' Association (TSRA) regarding increasing resident participation in the effort. In TSRA internal discussions about the site, the chief concern was the anonymity of those who submitted cases.

Although CTSNet login information is required to access the site, it is electronically scrambled so that the users identity is “unobtainable and untraceable through any means, even if CTSNet wanted to try to find that information, they could not,” said Dr. Marshall. “It is scrambled to the extent that even if the Supreme Court ordered CTSNet to divulge the data, CTSNet would be unable to do so because they simply do not have that data; it doesn't exist anywhere,” explained Dr. Sundt.

Furthermore, the cases submitted are modified to remove any data that is identifiable and only those with CTSNet logins can review the cases. It is also important to recognize that by definition, no legally actionable material can be submitted; for legal reasons; no actual harm to a patient can have occurred for a case to be considered a “near miss.”

What is to be gained by submitting cases to the site? “Everybody makes mistakes … there's an old saying that a mistake is only a mistake when you don't learn from it. The purpose of a site like this is to share your mistakes and have other people benefit from it - that is something good that can come out of an otherwise bad situation. In a near miss, there is no harm to the patient, but we still can benefit.

“The idea is to move outside the team-centric morbidity and mortality conference type of sharing to a sharing with the rest of the field things that would benefit everybody and by doing this to end up avoiding that problem in a different place - how great is that?” said Dr. Bacha. “And, the more robust the site becomes, the more the field would benefit,” he continued.

Besides these altruistic benefits, those who review the site can also learn from the cases others have submitted. Visitors will see that previously submitted cases have been analyzed by a human factors expert, who provided useful commentary on the situations described. Dr. Marshall has analyzed all of the cases submitted to date and has found that they are split about 50/50 between labeling and device/equipment errors.

For instance, Dr. Marshall described a case of a labeling error in the context of transplantation. In this case, both the heart and lungs were procured at one institution but when the heart and lung teams arrived at their home institutions, they found they had brought the wrong cooler back with them; the heart team had the lungs and the lung team had the heart.

As it turned out, the organs went to neighboring institutions so the error was easily rectified, but this was an obvious near miss with a practical, easy to implement solution: label your coolers.

There is a lot to be gained from this project with very little downside; “it's very easy to submit cases, it is very straightforward and totally anonymous” said Dr. Marshall “and the more cases we have, the more we can learn.”

Many residents are unaware that a near miss reporting site for cardiothoracic surgery exists, the Cardiothoracic Safety Reporting System. This system, available through the CTSNet website (http://ctsrs.ctsnet.org/) allows anyone with a CTSNet login to submit descriptions of near misses and review the near misses others have submitted, ranging from labeling errors to a case of an ascending aortic graft igniting during a Bentall procedure.

By way of background, it has been estimated that about 100,000 people die avoidable deaths annually in U.S. hospitals, and many more incur injuries to the tune of an annual cost of approximately $9 billion; this exceeds the combined number of deaths and injuries from automobile and airplane crashes, suicides, poisonings, drownings and falls annually (BMJ 2000; 320(7237): 759-63). To reduce this number of errors requires learning not only from the times harm resulted to patients from errors, but also the cases where an error occurred but negative consequences were averted, a “near miss.”

As surgeons, we are accustomed to the discussion of our errors in regular morbidity and mortality conferences. Conferences such as these are invaluable for learning and practice improvement, but are limited in that they focus on actual adverse events, with near-misses rarely discussed. And, since only the participants present at the conferences learn the lessons to be gleaned from these events, the impact of conferences such as this are narrow.

In other disciplines, industry-wide schemes for reporting “close calls,” near misses, or sentinel (“warning”) events have been created. The near-miss reporting system in aviation, the Aviation Reporting Safety System (http://asrs.arc.nasa.gov/), is well-known, but similar systems are in place in the nuclear power industry, the military, petrochemical processing and steel production, high-reliability organizations which function in “high consequence” environments (www.ctsnet.org/sections/newsandviews/specialreports/article-10.html).

With these examples in mind, in 2007 the STS's Workforce for Patient Safety, at the time under the leadership of Dr. Thor Sundt, created the Cardiothoracic Safety Reporting System. Dr. Sundt, Dr. Marshall Blair, the current chair of the Workforce, and Dr. Emile Bacha, who was involved in the early planning and discussion of this project, recently approached the Thoracic Surgery Residents' Association (TSRA) regarding increasing resident participation in the effort. In TSRA internal discussions about the site, the chief concern was the anonymity of those who submitted cases.

Although CTSNet login information is required to access the site, it is electronically scrambled so that the users identity is “unobtainable and untraceable through any means, even if CTSNet wanted to try to find that information, they could not,” said Dr. Marshall. “It is scrambled to the extent that even if the Supreme Court ordered CTSNet to divulge the data, CTSNet would be unable to do so because they simply do not have that data; it doesn't exist anywhere,” explained Dr. Sundt.

Furthermore, the cases submitted are modified to remove any data that is identifiable and only those with CTSNet logins can review the cases. It is also important to recognize that by definition, no legally actionable material can be submitted; for legal reasons; no actual harm to a patient can have occurred for a case to be considered a “near miss.”

What is to be gained by submitting cases to the site? “Everybody makes mistakes … there's an old saying that a mistake is only a mistake when you don't learn from it. The purpose of a site like this is to share your mistakes and have other people benefit from it - that is something good that can come out of an otherwise bad situation. In a near miss, there is no harm to the patient, but we still can benefit.

“The idea is to move outside the team-centric morbidity and mortality conference type of sharing to a sharing with the rest of the field things that would benefit everybody and by doing this to end up avoiding that problem in a different place - how great is that?” said Dr. Bacha. “And, the more robust the site becomes, the more the field would benefit,” he continued.

Besides these altruistic benefits, those who review the site can also learn from the cases others have submitted. Visitors will see that previously submitted cases have been analyzed by a human factors expert, who provided useful commentary on the situations described. Dr. Marshall has analyzed all of the cases submitted to date and has found that they are split about 50/50 between labeling and device/equipment errors.

For instance, Dr. Marshall described a case of a labeling error in the context of transplantation. In this case, both the heart and lungs were procured at one institution but when the heart and lung teams arrived at their home institutions, they found they had brought the wrong cooler back with them; the heart team had the lungs and the lung team had the heart.

As it turned out, the organs went to neighboring institutions so the error was easily rectified, but this was an obvious near miss with a practical, easy to implement solution: label your coolers.

There is a lot to be gained from this project with very little downside; “it's very easy to submit cases, it is very straightforward and totally anonymous” said Dr. Marshall “and the more cases we have, the more we can learn.”

Many residents are unaware that a near miss reporting site for cardiothoracic surgery exists, the Cardiothoracic Safety Reporting System. This system, available through the CTSNet website (http://ctsrs.ctsnet.org/) allows anyone with a CTSNet login to submit descriptions of near misses and review the near misses others have submitted, ranging from labeling errors to a case of an ascending aortic graft igniting during a Bentall procedure.

By way of background, it has been estimated that about 100,000 people die avoidable deaths annually in U.S. hospitals, and many more incur injuries to the tune of an annual cost of approximately $9 billion; this exceeds the combined number of deaths and injuries from automobile and airplane crashes, suicides, poisonings, drownings and falls annually (BMJ 2000; 320(7237): 759-63). To reduce this number of errors requires learning not only from the times harm resulted to patients from errors, but also the cases where an error occurred but negative consequences were averted, a “near miss.”

As surgeons, we are accustomed to the discussion of our errors in regular morbidity and mortality conferences. Conferences such as these are invaluable for learning and practice improvement, but are limited in that they focus on actual adverse events, with near-misses rarely discussed. And, since only the participants present at the conferences learn the lessons to be gleaned from these events, the impact of conferences such as this are narrow.

In other disciplines, industry-wide schemes for reporting “close calls,” near misses, or sentinel (“warning”) events have been created. The near-miss reporting system in aviation, the Aviation Reporting Safety System (http://asrs.arc.nasa.gov/), is well-known, but similar systems are in place in the nuclear power industry, the military, petrochemical processing and steel production, high-reliability organizations which function in “high consequence” environments (www.ctsnet.org/sections/newsandviews/specialreports/article-10.html).

With these examples in mind, in 2007 the STS's Workforce for Patient Safety, at the time under the leadership of Dr. Thor Sundt, created the Cardiothoracic Safety Reporting System. Dr. Sundt, Dr. Marshall Blair, the current chair of the Workforce, and Dr. Emile Bacha, who was involved in the early planning and discussion of this project, recently approached the Thoracic Surgery Residents' Association (TSRA) regarding increasing resident participation in the effort. In TSRA internal discussions about the site, the chief concern was the anonymity of those who submitted cases.

Although CTSNet login information is required to access the site, it is electronically scrambled so that the users identity is “unobtainable and untraceable through any means, even if CTSNet wanted to try to find that information, they could not,” said Dr. Marshall. “It is scrambled to the extent that even if the Supreme Court ordered CTSNet to divulge the data, CTSNet would be unable to do so because they simply do not have that data; it doesn't exist anywhere,” explained Dr. Sundt.

Furthermore, the cases submitted are modified to remove any data that is identifiable and only those with CTSNet logins can review the cases. It is also important to recognize that by definition, no legally actionable material can be submitted; for legal reasons; no actual harm to a patient can have occurred for a case to be considered a “near miss.”

What is to be gained by submitting cases to the site? “Everybody makes mistakes … there's an old saying that a mistake is only a mistake when you don't learn from it. The purpose of a site like this is to share your mistakes and have other people benefit from it - that is something good that can come out of an otherwise bad situation. In a near miss, there is no harm to the patient, but we still can benefit.

“The idea is to move outside the team-centric morbidity and mortality conference type of sharing to a sharing with the rest of the field things that would benefit everybody and by doing this to end up avoiding that problem in a different place - how great is that?” said Dr. Bacha. “And, the more robust the site becomes, the more the field would benefit,” he continued.

Besides these altruistic benefits, those who review the site can also learn from the cases others have submitted. Visitors will see that previously submitted cases have been analyzed by a human factors expert, who provided useful commentary on the situations described. Dr. Marshall has analyzed all of the cases submitted to date and has found that they are split about 50/50 between labeling and device/equipment errors.

For instance, Dr. Marshall described a case of a labeling error in the context of transplantation. In this case, both the heart and lungs were procured at one institution but when the heart and lung teams arrived at their home institutions, they found they had brought the wrong cooler back with them; the heart team had the lungs and the lung team had the heart.

As it turned out, the organs went to neighboring institutions so the error was easily rectified, but this was an obvious near miss with a practical, easy to implement solution: label your coolers.

There is a lot to be gained from this project with very little downside; “it's very easy to submit cases, it is very straightforward and totally anonymous” said Dr. Marshall “and the more cases we have, the more we can learn.”

News from the TSRA

The STS meeting in January led to many discussions within the TSRA including both future and current events. Future events included the results of the recent resident survey, upcoming thoracic surgery review book, new opportunities in using social media and further improvement of the "boot camp" weekend for new residents. More immediate conversation included continued adjustments in work hour restrictions, job hunting strategies and a discussion on the steps of completing the board exam.

A Message from Dr. William A. Baumgartner on Behalf of the ABTS to the TSRA at the STS Annual Meeting

Passing a board exam necessitates proving to the examiners you have an accurate plan on where to go with a patient. Applying for the board exam on the other hand necessitates an accurate map of where you have been as a training physician. Documentation of cases performed by a trainee serves as this "map" of past accomplishments. A case journal is not only used as a requirement for board exams. Hospitals, insurers, and industry can also use these data to choose who is going to perform their next test or treatment.

It is the responsibility of the trainee to maintain their case log to confirm they are getting their index cases completed. More and more applicants for the ABTS are applying with holes in their resume with categories of cases not completed. Often the cause of this is not a program's lack of exposure, but poor documentation during the period of training.

Much like not getting paid for poor documentation of procedures when out in practice, the ABTS will soon become stricter on documentation of index cases.

The good news is that the program for logging cases will soon follow the CPT coding system for CT Surgery residents starting in July, 2011. The program will provide for more accurate documentation and will also give a more "real world" experience. In the meantime, check your case log regularly and expeditiously discuss with your program director any deficiencies that may exist.

The STS meeting in January led to many discussions within the TSRA including both future and current events. Future events included the results of the recent resident survey, upcoming thoracic surgery review book, new opportunities in using social media and further improvement of the "boot camp" weekend for new residents. More immediate conversation included continued adjustments in work hour restrictions, job hunting strategies and a discussion on the steps of completing the board exam.

A Message from Dr. William A. Baumgartner on Behalf of the ABTS to the TSRA at the STS Annual Meeting

Passing a board exam necessitates proving to the examiners you have an accurate plan on where to go with a patient. Applying for the board exam on the other hand necessitates an accurate map of where you have been as a training physician. Documentation of cases performed by a trainee serves as this "map" of past accomplishments. A case journal is not only used as a requirement for board exams. Hospitals, insurers, and industry can also use these data to choose who is going to perform their next test or treatment.

It is the responsibility of the trainee to maintain their case log to confirm they are getting their index cases completed. More and more applicants for the ABTS are applying with holes in their resume with categories of cases not completed. Often the cause of this is not a program's lack of exposure, but poor documentation during the period of training.

Much like not getting paid for poor documentation of procedures when out in practice, the ABTS will soon become stricter on documentation of index cases.

The good news is that the program for logging cases will soon follow the CPT coding system for CT Surgery residents starting in July, 2011. The program will provide for more accurate documentation and will also give a more "real world" experience. In the meantime, check your case log regularly and expeditiously discuss with your program director any deficiencies that may exist.

The STS meeting in January led to many discussions within the TSRA including both future and current events. Future events included the results of the recent resident survey, upcoming thoracic surgery review book, new opportunities in using social media and further improvement of the "boot camp" weekend for new residents. More immediate conversation included continued adjustments in work hour restrictions, job hunting strategies and a discussion on the steps of completing the board exam.

A Message from Dr. William A. Baumgartner on Behalf of the ABTS to the TSRA at the STS Annual Meeting

Passing a board exam necessitates proving to the examiners you have an accurate plan on where to go with a patient. Applying for the board exam on the other hand necessitates an accurate map of where you have been as a training physician. Documentation of cases performed by a trainee serves as this "map" of past accomplishments. A case journal is not only used as a requirement for board exams. Hospitals, insurers, and industry can also use these data to choose who is going to perform their next test or treatment.

It is the responsibility of the trainee to maintain their case log to confirm they are getting their index cases completed. More and more applicants for the ABTS are applying with holes in their resume with categories of cases not completed. Often the cause of this is not a program's lack of exposure, but poor documentation during the period of training.

Much like not getting paid for poor documentation of procedures when out in practice, the ABTS will soon become stricter on documentation of index cases.

The good news is that the program for logging cases will soon follow the CPT coding system for CT Surgery residents starting in July, 2011. The program will provide for more accurate documentation and will also give a more "real world" experience. In the meantime, check your case log regularly and expeditiously discuss with your program director any deficiencies that may exist.

Perspectives From Cross-Trained Cardiac Surgeons (Part II)

In the second part of a discussion of the potential integration of Cardiac Surgery and Interventional Cardiology, two "early adopters" - Mathew Williams at New York Presbyterian Hospital-Columbia and Michael Davidson at the Brigham and Women's Hospital - continue their personal perspective on potential problems and training challenges such integration might entail.

Dr. Davidson notes there are some downsides to this new type of practice. “The issues that all of us face that do this - the 'ugly underbelly,' if you will - revolve around competition and turf. It plays out differently in every institution due to differences in reimbursement at each institution, etc.

"But even if reimbursement is not the issue, there are also issues of identity. There is a little element of being in 'no man's land': you are set aside from your cardiac surgery colleagues because you do things that they don't. And on the flipside you have the cardiologists, who are largely supportive, but there is always a little worry about encroachment on turf that you have to be very careful about. I don't think anyone has the ideal solution to this."

Looking to the future and the idea of the integration of cardiac surgery and interventional cardiology, both focused on potential changes in training programs. As a first point, they both noted that a significant amount time is required to master catheter-based skills."We need to accept that it takes more than three months to learn," Dr. Williams said.

Dr. Davidson echoed and expanded on this point: "One of the dangers cardiac surgeons face is that because they have such a high degree of technical skills, they tend to not have enough appreciation for the degree of technical skill that is involved in being a good, competent interventional cardiologists. Sometimes, cardiac surgeons assume that because they have good surgical skills, they can waltz into a cardiac catheterization lab and 'figure it out' in a short period of time and this is simply not true. One actually needs to put in a fair amount of time and do a few hundred cases to gain advanced catheter skills.

"One can get lulled into a sense of ease by doing a couple of easy procedures (e.g. a straightforward aortic stent graft) and then getting a sense that endovascular work is very easy. But in fact when one does more advanced procedures, one sees that it actually does take a lot of technical skill. For a cardiac surgeon to do this right, they have to understand the idea that you can't do a weekend or month-long course and expect to have real endovascular competency. "

"There's a bit of a paradox in that many feel it would be good to have more of a cardiac surgical presence in the cath lab; at the same time you risk having cardiac surgeons who are inadequately trained and may get into trouble assuming their surgical skills translate into endovascular skills."

Both went on to comment on the changes in training that would be necessary if interventional cardiology and cardiac surgery were to merge in the future. "There's a lot of divergence of opinion here. I am in the camp that believes that the separation of interventional cardiology and cardiac surgery is artificial and based on historical models that may not apply anymore. I think we should go more towards disease based treatment but in doing this, there would be a blurring of the lines as to be who should be doing what. One way to avoid the 'turf battles' and to achieve better integration would be to have the training integrated from the beginning," said Dr. Davidson.

"One of the problems that has been brought up is in this country is that often the treatment a patient gets is determined by who they happen to go see - one treatment if they go to a surgeon and one treatment if they go to a cardiologist" for the same disease.

"Ideally, if you train people from the ground up to be disease managers and then further differentiate from that point,"say 'outpatient clinicians' versus 'imaging clinicians' versus those that do 'big procedures' or endovascular procedures but united by their core training, it may reduce the 'turf battles' that are actually not very good for patients. The core should be patient care", Davidson continued.

In making any large-scale change, there are always two options: swift, radical action or more gradual stepwise changes.

"The question becomes should we do this by mass upheaval or incremental steps over time? Hard to know," Dr. Davidson remarked.

There are multiple complexities involved in such a change, he noted: "there are a lot of realities that go into this. For instance, the idea of merging cardiology and cardiac surgery doesn't take into account some practitioners who want to divide their time between cardiac and thoracic surgery. This group is more committed to keeping cardiac and thoracic surgery together and maintaining the general surgery training. So, there is an internal conflict/struggles even within CT surgery; in addition to the potential conflicts between cardiac surgery and cardiology."

On his vision of the future, Dr. Williams commented, "going forward, what I imagine is continued slow evolution - that's not my dream; I would hope for merged departments."

He went on to express concern regarding the future of cardiac surgery training. "Cardiac surgery is moving too slowly, in my opinion. At our institution, for example, we've been starting a six-year training program but given the amount of thoracic and general surgery they are required to do, we are not going to be training the cardiac surgeon of the future. Unless we radically change the training structure, true integration of the fields is never going to happen."

Dr. Williams pointed out that in his experience, the primary force of resistance to the idea of the integration of interventional cardiology and cardiac surgery was not from the medical side: "Actually in my experience, the cardiologists have embraced this a lot more than cardiac surgery.

"The resistance is not so much from the medical side as the surgical side. They have been a lot more receptive to this. Cardiothoracic surgeons seem to be more interested in fighting about turf instead of really looking at what the appropriate training is."

In the second part of a discussion of the potential integration of Cardiac Surgery and Interventional Cardiology, two "early adopters" - Mathew Williams at New York Presbyterian Hospital-Columbia and Michael Davidson at the Brigham and Women's Hospital - continue their personal perspective on potential problems and training challenges such integration might entail.

Dr. Davidson notes there are some downsides to this new type of practice. “The issues that all of us face that do this - the 'ugly underbelly,' if you will - revolve around competition and turf. It plays out differently in every institution due to differences in reimbursement at each institution, etc.

"But even if reimbursement is not the issue, there are also issues of identity. There is a little element of being in 'no man's land': you are set aside from your cardiac surgery colleagues because you do things that they don't. And on the flipside you have the cardiologists, who are largely supportive, but there is always a little worry about encroachment on turf that you have to be very careful about. I don't think anyone has the ideal solution to this."

Looking to the future and the idea of the integration of cardiac surgery and interventional cardiology, both focused on potential changes in training programs. As a first point, they both noted that a significant amount time is required to master catheter-based skills."We need to accept that it takes more than three months to learn," Dr. Williams said.

Dr. Davidson echoed and expanded on this point: "One of the dangers cardiac surgeons face is that because they have such a high degree of technical skills, they tend to not have enough appreciation for the degree of technical skill that is involved in being a good, competent interventional cardiologists. Sometimes, cardiac surgeons assume that because they have good surgical skills, they can waltz into a cardiac catheterization lab and 'figure it out' in a short period of time and this is simply not true. One actually needs to put in a fair amount of time and do a few hundred cases to gain advanced catheter skills.

"One can get lulled into a sense of ease by doing a couple of easy procedures (e.g. a straightforward aortic stent graft) and then getting a sense that endovascular work is very easy. But in fact when one does more advanced procedures, one sees that it actually does take a lot of technical skill. For a cardiac surgeon to do this right, they have to understand the idea that you can't do a weekend or month-long course and expect to have real endovascular competency. "

"There's a bit of a paradox in that many feel it would be good to have more of a cardiac surgical presence in the cath lab; at the same time you risk having cardiac surgeons who are inadequately trained and may get into trouble assuming their surgical skills translate into endovascular skills."

Both went on to comment on the changes in training that would be necessary if interventional cardiology and cardiac surgery were to merge in the future. "There's a lot of divergence of opinion here. I am in the camp that believes that the separation of interventional cardiology and cardiac surgery is artificial and based on historical models that may not apply anymore. I think we should go more towards disease based treatment but in doing this, there would be a blurring of the lines as to be who should be doing what. One way to avoid the 'turf battles' and to achieve better integration would be to have the training integrated from the beginning," said Dr. Davidson.

"One of the problems that has been brought up is in this country is that often the treatment a patient gets is determined by who they happen to go see - one treatment if they go to a surgeon and one treatment if they go to a cardiologist" for the same disease.

"Ideally, if you train people from the ground up to be disease managers and then further differentiate from that point,"say 'outpatient clinicians' versus 'imaging clinicians' versus those that do 'big procedures' or endovascular procedures but united by their core training, it may reduce the 'turf battles' that are actually not very good for patients. The core should be patient care", Davidson continued.

In making any large-scale change, there are always two options: swift, radical action or more gradual stepwise changes.

"The question becomes should we do this by mass upheaval or incremental steps over time? Hard to know," Dr. Davidson remarked.

There are multiple complexities involved in such a change, he noted: "there are a lot of realities that go into this. For instance, the idea of merging cardiology and cardiac surgery doesn't take into account some practitioners who want to divide their time between cardiac and thoracic surgery. This group is more committed to keeping cardiac and thoracic surgery together and maintaining the general surgery training. So, there is an internal conflict/struggles even within CT surgery; in addition to the potential conflicts between cardiac surgery and cardiology."

On his vision of the future, Dr. Williams commented, "going forward, what I imagine is continued slow evolution - that's not my dream; I would hope for merged departments."

He went on to express concern regarding the future of cardiac surgery training. "Cardiac surgery is moving too slowly, in my opinion. At our institution, for example, we've been starting a six-year training program but given the amount of thoracic and general surgery they are required to do, we are not going to be training the cardiac surgeon of the future. Unless we radically change the training structure, true integration of the fields is never going to happen."

Dr. Williams pointed out that in his experience, the primary force of resistance to the idea of the integration of interventional cardiology and cardiac surgery was not from the medical side: "Actually in my experience, the cardiologists have embraced this a lot more than cardiac surgery.

"The resistance is not so much from the medical side as the surgical side. They have been a lot more receptive to this. Cardiothoracic surgeons seem to be more interested in fighting about turf instead of really looking at what the appropriate training is."

In the second part of a discussion of the potential integration of Cardiac Surgery and Interventional Cardiology, two "early adopters" - Mathew Williams at New York Presbyterian Hospital-Columbia and Michael Davidson at the Brigham and Women's Hospital - continue their personal perspective on potential problems and training challenges such integration might entail.

Dr. Davidson notes there are some downsides to this new type of practice. “The issues that all of us face that do this - the 'ugly underbelly,' if you will - revolve around competition and turf. It plays out differently in every institution due to differences in reimbursement at each institution, etc.

"But even if reimbursement is not the issue, there are also issues of identity. There is a little element of being in 'no man's land': you are set aside from your cardiac surgery colleagues because you do things that they don't. And on the flipside you have the cardiologists, who are largely supportive, but there is always a little worry about encroachment on turf that you have to be very careful about. I don't think anyone has the ideal solution to this."

Looking to the future and the idea of the integration of cardiac surgery and interventional cardiology, both focused on potential changes in training programs. As a first point, they both noted that a significant amount time is required to master catheter-based skills."We need to accept that it takes more than three months to learn," Dr. Williams said.

Dr. Davidson echoed and expanded on this point: "One of the dangers cardiac surgeons face is that because they have such a high degree of technical skills, they tend to not have enough appreciation for the degree of technical skill that is involved in being a good, competent interventional cardiologists. Sometimes, cardiac surgeons assume that because they have good surgical skills, they can waltz into a cardiac catheterization lab and 'figure it out' in a short period of time and this is simply not true. One actually needs to put in a fair amount of time and do a few hundred cases to gain advanced catheter skills.

"One can get lulled into a sense of ease by doing a couple of easy procedures (e.g. a straightforward aortic stent graft) and then getting a sense that endovascular work is very easy. But in fact when one does more advanced procedures, one sees that it actually does take a lot of technical skill. For a cardiac surgeon to do this right, they have to understand the idea that you can't do a weekend or month-long course and expect to have real endovascular competency. "

"There's a bit of a paradox in that many feel it would be good to have more of a cardiac surgical presence in the cath lab; at the same time you risk having cardiac surgeons who are inadequately trained and may get into trouble assuming their surgical skills translate into endovascular skills."

Both went on to comment on the changes in training that would be necessary if interventional cardiology and cardiac surgery were to merge in the future. "There's a lot of divergence of opinion here. I am in the camp that believes that the separation of interventional cardiology and cardiac surgery is artificial and based on historical models that may not apply anymore. I think we should go more towards disease based treatment but in doing this, there would be a blurring of the lines as to be who should be doing what. One way to avoid the 'turf battles' and to achieve better integration would be to have the training integrated from the beginning," said Dr. Davidson.

"One of the problems that has been brought up is in this country is that often the treatment a patient gets is determined by who they happen to go see - one treatment if they go to a surgeon and one treatment if they go to a cardiologist" for the same disease.

"Ideally, if you train people from the ground up to be disease managers and then further differentiate from that point,"say 'outpatient clinicians' versus 'imaging clinicians' versus those that do 'big procedures' or endovascular procedures but united by their core training, it may reduce the 'turf battles' that are actually not very good for patients. The core should be patient care", Davidson continued.

In making any large-scale change, there are always two options: swift, radical action or more gradual stepwise changes.

"The question becomes should we do this by mass upheaval or incremental steps over time? Hard to know," Dr. Davidson remarked.

There are multiple complexities involved in such a change, he noted: "there are a lot of realities that go into this. For instance, the idea of merging cardiology and cardiac surgery doesn't take into account some practitioners who want to divide their time between cardiac and thoracic surgery. This group is more committed to keeping cardiac and thoracic surgery together and maintaining the general surgery training. So, there is an internal conflict/struggles even within CT surgery; in addition to the potential conflicts between cardiac surgery and cardiology."

On his vision of the future, Dr. Williams commented, "going forward, what I imagine is continued slow evolution - that's not my dream; I would hope for merged departments."

He went on to express concern regarding the future of cardiac surgery training. "Cardiac surgery is moving too slowly, in my opinion. At our institution, for example, we've been starting a six-year training program but given the amount of thoracic and general surgery they are required to do, we are not going to be training the cardiac surgeon of the future. Unless we radically change the training structure, true integration of the fields is never going to happen."

Dr. Williams pointed out that in his experience, the primary force of resistance to the idea of the integration of interventional cardiology and cardiac surgery was not from the medical side: "Actually in my experience, the cardiologists have embraced this a lot more than cardiac surgery.

"The resistance is not so much from the medical side as the surgical side. They have been a lot more receptive to this. Cardiothoracic surgeons seem to be more interested in fighting about turf instead of really looking at what the appropriate training is."

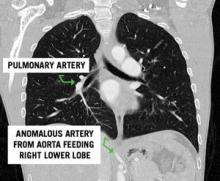

Clinical Challenge

Directed questions:

1. What are the two main subtypes of pulmonary sequestration?

2. This patient had a normal appearing lung field on CT scan. What subtype of pulmonary sequestration does this represent?

3. What is the vascular anatomy that defines the difference between the two subtypes of sequestration?

4. In which lobes are sequestrations most commonly found?

5. Which subtype is associated with congenital anomalies?

6. What therapy would you recommend to this patient?

7. Is there a role for the resection of an incidentally found, asymptomatic sequestration?

Answers and discussion on page 4.

Clinical Challenge: Kety Points

--Definition:

- Portion of lung parenchyma with absence of normal bronchial communication with the tracheobronchial tree and systemic arterial blood supply.

--Two types:

- Extralobar: mass of lung tissue separate from normal lung with its own pleural investment. Venous drainage and arterial supply are systemic, not pulmonary in origin

- Intralobar: mass of abnormal lung tissue intimately related with normal lung parenchyma with systemic arterial supply but normal pulmonary venous drainage

--Common presentation:

- recurrent, chronic pulmonary infections

--Arterial blood supply is always systemic

- Most commonly, arising from the descending thoracic or abdominal aorta

--Most commonly located in the lower lobe but extralobar sequestrations have been reported below the diaphragm as well

--Treatment:

- Elective surgical resection

- May need urgent/emergent resection if significant hemoptysis or intrathoracic hemorrhage

- Intralobar sequestrations often require lobectomy while extralobar resections can often be dissected free from normal lung parenchyma

Selected References and Additional Resources:

Bratu, I. The multiple facets of pulmonary sequestration. J Pediatric Surgery. 35(5):784-790, 2001.

Mendeloff, EN. Sequestrations, Congenital Cystic Adenomatoid Malformations, and Congenital Lobar Emphysema. J

Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 16:209-214, 2004.

Hamanaka, H. Surgical Treatment of infected intralobar pulmonary sequestration: a collective review of patients older than 50 years reported in the literature. Ann Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 13(5):331, 2007.

Stanton, M. Systemic review and meta-analysis of the postnatal management of congenital cystic lung lesions. J Pediatric Surg. 44(5): 1027, 2009.

Yamanaka, A. Anomalous systemic arterial supply to normal basal segments of the left lower lobe. Ann Thoracic Surgery. 68(2): 332-8, 1999.

TSDAWeekly Curriculum - "Congenital Lung Anomalies" http://www.tsda.org/documents/PDF/Weekly%20Curricula/E-mail%20Archive/06.10.10.pdf

Answers to the Clinical Challenge

1. Intralobar and extralobar pulmonary sequestrations.

2. Pryce type I sequestration classifies a rare subtype characterized by anomalous systemic arterial supply to a normal segment of lung

3. Both intralobar and extralobar sequestrations are characterized by systemic arterial inflow, most commonly from the aorta. Intralobar sequestrations have pulmonary venous return. In contrast, extralobar sequestrations have systemic venous drainage, most commonly via the azygous or hemiazygous venous system.

4. Pulmonary sequestrations are most commonly found in the lower lobe, left side more common than right. Uncommonly, extralobar sequestrations can be found outside of the chest cavity with reports of lesions below the diaphragm.

5. Over half of patients with extralobar sequestrations have associated congenital anomalies. Common anomalies include congenital diaphragmatic hernia, pericardial defects, other bronchopulmonary foregut malformations and total anomalous pulmonary venous return. Congenital anomalies are uncommon with intralobar sequestrations.

6. Resection of the sequestration with directed ligation of the arterial feeding vessel.

7. Asymptomatic sequestrations should be resected due to the potential for developing infection or hemorrhage, including aneurysm formation and rupture of the aberrant arterial vasculature. There are reports that suggest resection for symptomatic disease, especially infection, is associated with a higher morbidity than resection for asymptomatic disease.

Directed questions:

1. What are the two main subtypes of pulmonary sequestration?

2. This patient had a normal appearing lung field on CT scan. What subtype of pulmonary sequestration does this represent?

3. What is the vascular anatomy that defines the difference between the two subtypes of sequestration?

4. In which lobes are sequestrations most commonly found?

5. Which subtype is associated with congenital anomalies?

6. What therapy would you recommend to this patient?

7. Is there a role for the resection of an incidentally found, asymptomatic sequestration?

Answers and discussion on page 4.

Clinical Challenge: Kety Points

--Definition:

- Portion of lung parenchyma with absence of normal bronchial communication with the tracheobronchial tree and systemic arterial blood supply.

--Two types:

- Extralobar: mass of lung tissue separate from normal lung with its own pleural investment. Venous drainage and arterial supply are systemic, not pulmonary in origin

- Intralobar: mass of abnormal lung tissue intimately related with normal lung parenchyma with systemic arterial supply but normal pulmonary venous drainage

--Common presentation:

- recurrent, chronic pulmonary infections

--Arterial blood supply is always systemic

- Most commonly, arising from the descending thoracic or abdominal aorta

--Most commonly located in the lower lobe but extralobar sequestrations have been reported below the diaphragm as well

--Treatment:

- Elective surgical resection

- May need urgent/emergent resection if significant hemoptysis or intrathoracic hemorrhage

- Intralobar sequestrations often require lobectomy while extralobar resections can often be dissected free from normal lung parenchyma

Selected References and Additional Resources:

Bratu, I. The multiple facets of pulmonary sequestration. J Pediatric Surgery. 35(5):784-790, 2001.

Mendeloff, EN. Sequestrations, Congenital Cystic Adenomatoid Malformations, and Congenital Lobar Emphysema. J

Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 16:209-214, 2004.

Hamanaka, H. Surgical Treatment of infected intralobar pulmonary sequestration: a collective review of patients older than 50 years reported in the literature. Ann Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 13(5):331, 2007.

Stanton, M. Systemic review and meta-analysis of the postnatal management of congenital cystic lung lesions. J Pediatric Surg. 44(5): 1027, 2009.

Yamanaka, A. Anomalous systemic arterial supply to normal basal segments of the left lower lobe. Ann Thoracic Surgery. 68(2): 332-8, 1999.

TSDAWeekly Curriculum - "Congenital Lung Anomalies" http://www.tsda.org/documents/PDF/Weekly%20Curricula/E-mail%20Archive/06.10.10.pdf

Answers to the Clinical Challenge

1. Intralobar and extralobar pulmonary sequestrations.

2. Pryce type I sequestration classifies a rare subtype characterized by anomalous systemic arterial supply to a normal segment of lung

3. Both intralobar and extralobar sequestrations are characterized by systemic arterial inflow, most commonly from the aorta. Intralobar sequestrations have pulmonary venous return. In contrast, extralobar sequestrations have systemic venous drainage, most commonly via the azygous or hemiazygous venous system.

4. Pulmonary sequestrations are most commonly found in the lower lobe, left side more common than right. Uncommonly, extralobar sequestrations can be found outside of the chest cavity with reports of lesions below the diaphragm.

5. Over half of patients with extralobar sequestrations have associated congenital anomalies. Common anomalies include congenital diaphragmatic hernia, pericardial defects, other bronchopulmonary foregut malformations and total anomalous pulmonary venous return. Congenital anomalies are uncommon with intralobar sequestrations.

6. Resection of the sequestration with directed ligation of the arterial feeding vessel.

7. Asymptomatic sequestrations should be resected due to the potential for developing infection or hemorrhage, including aneurysm formation and rupture of the aberrant arterial vasculature. There are reports that suggest resection for symptomatic disease, especially infection, is associated with a higher morbidity than resection for asymptomatic disease.

Directed questions:

1. What are the two main subtypes of pulmonary sequestration?

2. This patient had a normal appearing lung field on CT scan. What subtype of pulmonary sequestration does this represent?

3. What is the vascular anatomy that defines the difference between the two subtypes of sequestration?

4. In which lobes are sequestrations most commonly found?

5. Which subtype is associated with congenital anomalies?

6. What therapy would you recommend to this patient?

7. Is there a role for the resection of an incidentally found, asymptomatic sequestration?

Answers and discussion on page 4.

Clinical Challenge: Kety Points

--Definition:

- Portion of lung parenchyma with absence of normal bronchial communication with the tracheobronchial tree and systemic arterial blood supply.

--Two types:

- Extralobar: mass of lung tissue separate from normal lung with its own pleural investment. Venous drainage and arterial supply are systemic, not pulmonary in origin

- Intralobar: mass of abnormal lung tissue intimately related with normal lung parenchyma with systemic arterial supply but normal pulmonary venous drainage

--Common presentation:

- recurrent, chronic pulmonary infections

--Arterial blood supply is always systemic

- Most commonly, arising from the descending thoracic or abdominal aorta

--Most commonly located in the lower lobe but extralobar sequestrations have been reported below the diaphragm as well

--Treatment:

- Elective surgical resection

- May need urgent/emergent resection if significant hemoptysis or intrathoracic hemorrhage

- Intralobar sequestrations often require lobectomy while extralobar resections can often be dissected free from normal lung parenchyma

Selected References and Additional Resources:

Bratu, I. The multiple facets of pulmonary sequestration. J Pediatric Surgery. 35(5):784-790, 2001.

Mendeloff, EN. Sequestrations, Congenital Cystic Adenomatoid Malformations, and Congenital Lobar Emphysema. J

Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 16:209-214, 2004.

Hamanaka, H. Surgical Treatment of infected intralobar pulmonary sequestration: a collective review of patients older than 50 years reported in the literature. Ann Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 13(5):331, 2007.

Stanton, M. Systemic review and meta-analysis of the postnatal management of congenital cystic lung lesions. J Pediatric Surg. 44(5): 1027, 2009.

Yamanaka, A. Anomalous systemic arterial supply to normal basal segments of the left lower lobe. Ann Thoracic Surgery. 68(2): 332-8, 1999.

TSDAWeekly Curriculum - "Congenital Lung Anomalies" http://www.tsda.org/documents/PDF/Weekly%20Curricula/E-mail%20Archive/06.10.10.pdf

Answers to the Clinical Challenge

1. Intralobar and extralobar pulmonary sequestrations.

2. Pryce type I sequestration classifies a rare subtype characterized by anomalous systemic arterial supply to a normal segment of lung

3. Both intralobar and extralobar sequestrations are characterized by systemic arterial inflow, most commonly from the aorta. Intralobar sequestrations have pulmonary venous return. In contrast, extralobar sequestrations have systemic venous drainage, most commonly via the azygous or hemiazygous venous system.

4. Pulmonary sequestrations are most commonly found in the lower lobe, left side more common than right. Uncommonly, extralobar sequestrations can be found outside of the chest cavity with reports of lesions below the diaphragm.

5. Over half of patients with extralobar sequestrations have associated congenital anomalies. Common anomalies include congenital diaphragmatic hernia, pericardial defects, other bronchopulmonary foregut malformations and total anomalous pulmonary venous return. Congenital anomalies are uncommon with intralobar sequestrations.

6. Resection of the sequestration with directed ligation of the arterial feeding vessel.

7. Asymptomatic sequestrations should be resected due to the potential for developing infection or hemorrhage, including aneurysm formation and rupture of the aberrant arterial vasculature. There are reports that suggest resection for symptomatic disease, especially infection, is associated with a higher morbidity than resection for asymptomatic disease.

Views from Cross-Trained Cardiac Surgeons (Part 1)

A session at the 2010 Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics conference co-sponsored by TCT, the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons centered on integrating cardiac surgery and interventional cardiology.

With such a shift being discussed, it is useful to consider the perspectives of two “early adopters" of this way of thinking - Dr. Mathew Williams at New York Presbyterian Hospital-Columbia and Dr. Michael Davidson at the Brigham and Women's Hospital. Both completed cardiac surgery training and then went on to pursue training in interventional cardiology. Each currently practices using a blend of techniques from both disciplines.

At the time they pursued interventional cardiology training, no formalized training programs for cardiac surgeons interested in interventional techniques existed. But both had observed the emergence of transcatheter valves.

“I've always had a strong interest in valves," said Dr. Davidson, “and it was very clear to me that transcatheter valve techniques would play an incredibly large role and that it was highly likely during my career that these would take a high-profile role. To be a full participant, I couldn't just have cardiac surgical skills but would also need interventional skills, and not just for 'cardiac surgical backup' or providing femoral access, but to really be a full participant - to understand the technology and how to utilize it."

Dr. Williams and Dr. Davidson each approached interventional cardiologists at their respective institutions to set up their training. Dr. Williams worked with Dr. Martin Leon, a prominent interventional cardiologist at Columbia and eventually completed a year-long traditional interventional cardiology fellowship, “I did everything the interventional cardiology fellows did, except I also spent a day a week in the OR as well to keep up those skills," Dr. Williams said.

Dr. Davidson worked with Dr. Donald Baim, a pioneer in interventional cardiology then at the Brigham, and did a year-long fellowship from 2005 to 2006. “I spent about 3 days a week in the cath lab and 2 days a week in the OR so I could keep up my surgical skills. I did a lot of diagnostic catheterizations and assisted in PCI cases. Because of my interest in valves, I was also involved any time there was a structural heart case such as mitral/aortic valvuloplasties. I also made a point of being involved in cases done by vascular surgeons (aortic, peripheral, renal, and carotid work) and spent some time in the electrophysiology lab to gain experience in trans-septal perforations."

The interventional cardiologists involved, Dr. Leon and Dr. Baim, were both described as very enthusiastic about this innovative training pathway. “It was something that Marty [Leon] had always thought was a great concept and had never really happened before then," Dr. Williams said. Similarly, “Dr. Baim loved the idea; it really meshed well with his world view of how the specialties were changing," said Dr. Davidson, who added that “having that kind of high-altitude backup was important and allowed me the air cover to pursue this sort of training."

After their interventional cardiology fellowships, both men joined the staff at their respective training institutions. Dr. Williams is on staff at Columbia in both interventional cardiology and cardiac surgery. “I do a reasonable amount of independent PCI and perform the full scope of interventional procedures - I've joined that group and take acute MI call. Our cardiologists have really embraced this and are fantastic. I am in the hybrid OR 4 days/week - not all of the cases I do in this room are hybrids, but I do completion angiograms on almost every CABG that I do. I do hybrid coronary revascularization with PCI and surgery in a single setting. However, the majority of my work is valvular - including 4-8 trans-catheter valves per month (either transapical or transfemoral). I also spend time in the cath lab - I do the routine, catheter-only based procedures there."

Dr. Davidson is on staff in cardiac surgery at the Brigham and does not perform coronary interventions. “I'm spending the majority of my time doing cardiac surgery with the emphasis being on valves, but I am also a full participant in any structural heart disease cases going on in interventional cardiology (e.g. transcatheter aortic valve). I also do my own cardiac catheterizations and so any given week, I have patients who come in for hybrid procedures. For instance a patient may come in with mitral valve prolapse and I will schedule them for cardiac catherization, possible stent and minimally invasive MVP in a single setting. I spend about one day a week doing catheter-based procedures and several days a week doing traditional surgery. Another thing that has occurred here is that we've had a programmatic approach to this integrated practice. We have a joint advanced valve and structural heart disease clinic that I started with one of my interventional colleagues that has now branched out to involve more cardiologists and more surgeons. In this clinic, cardiac surgeons and interventional cardiologists see patients jointly."

Dr. Davidson notes some of the benefits of cross-training: “It allows me to be a greater participant in my patient's care. For instance, I have patients sent to me who have very complicated valve disease and we may put them through a full workup including catheterization to figure out what component of their symptoms is the valve disease and what component may be from other pathologies. It makes me more involved in disease management, not just doing the surgeries as they come."

(Part 2 of this article follows next month).

A session at the 2010 Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics conference co-sponsored by TCT, the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons centered on integrating cardiac surgery and interventional cardiology.

With such a shift being discussed, it is useful to consider the perspectives of two “early adopters" of this way of thinking - Dr. Mathew Williams at New York Presbyterian Hospital-Columbia and Dr. Michael Davidson at the Brigham and Women's Hospital. Both completed cardiac surgery training and then went on to pursue training in interventional cardiology. Each currently practices using a blend of techniques from both disciplines.

At the time they pursued interventional cardiology training, no formalized training programs for cardiac surgeons interested in interventional techniques existed. But both had observed the emergence of transcatheter valves.

“I've always had a strong interest in valves," said Dr. Davidson, “and it was very clear to me that transcatheter valve techniques would play an incredibly large role and that it was highly likely during my career that these would take a high-profile role. To be a full participant, I couldn't just have cardiac surgical skills but would also need interventional skills, and not just for 'cardiac surgical backup' or providing femoral access, but to really be a full participant - to understand the technology and how to utilize it."

Dr. Williams and Dr. Davidson each approached interventional cardiologists at their respective institutions to set up their training. Dr. Williams worked with Dr. Martin Leon, a prominent interventional cardiologist at Columbia and eventually completed a year-long traditional interventional cardiology fellowship, “I did everything the interventional cardiology fellows did, except I also spent a day a week in the OR as well to keep up those skills," Dr. Williams said.

Dr. Davidson worked with Dr. Donald Baim, a pioneer in interventional cardiology then at the Brigham, and did a year-long fellowship from 2005 to 2006. “I spent about 3 days a week in the cath lab and 2 days a week in the OR so I could keep up my surgical skills. I did a lot of diagnostic catheterizations and assisted in PCI cases. Because of my interest in valves, I was also involved any time there was a structural heart case such as mitral/aortic valvuloplasties. I also made a point of being involved in cases done by vascular surgeons (aortic, peripheral, renal, and carotid work) and spent some time in the electrophysiology lab to gain experience in trans-septal perforations."

The interventional cardiologists involved, Dr. Leon and Dr. Baim, were both described as very enthusiastic about this innovative training pathway. “It was something that Marty [Leon] had always thought was a great concept and had never really happened before then," Dr. Williams said. Similarly, “Dr. Baim loved the idea; it really meshed well with his world view of how the specialties were changing," said Dr. Davidson, who added that “having that kind of high-altitude backup was important and allowed me the air cover to pursue this sort of training."

After their interventional cardiology fellowships, both men joined the staff at their respective training institutions. Dr. Williams is on staff at Columbia in both interventional cardiology and cardiac surgery. “I do a reasonable amount of independent PCI and perform the full scope of interventional procedures - I've joined that group and take acute MI call. Our cardiologists have really embraced this and are fantastic. I am in the hybrid OR 4 days/week - not all of the cases I do in this room are hybrids, but I do completion angiograms on almost every CABG that I do. I do hybrid coronary revascularization with PCI and surgery in a single setting. However, the majority of my work is valvular - including 4-8 trans-catheter valves per month (either transapical or transfemoral). I also spend time in the cath lab - I do the routine, catheter-only based procedures there."

Dr. Davidson is on staff in cardiac surgery at the Brigham and does not perform coronary interventions. “I'm spending the majority of my time doing cardiac surgery with the emphasis being on valves, but I am also a full participant in any structural heart disease cases going on in interventional cardiology (e.g. transcatheter aortic valve). I also do my own cardiac catheterizations and so any given week, I have patients who come in for hybrid procedures. For instance a patient may come in with mitral valve prolapse and I will schedule them for cardiac catherization, possible stent and minimally invasive MVP in a single setting. I spend about one day a week doing catheter-based procedures and several days a week doing traditional surgery. Another thing that has occurred here is that we've had a programmatic approach to this integrated practice. We have a joint advanced valve and structural heart disease clinic that I started with one of my interventional colleagues that has now branched out to involve more cardiologists and more surgeons. In this clinic, cardiac surgeons and interventional cardiologists see patients jointly."

Dr. Davidson notes some of the benefits of cross-training: “It allows me to be a greater participant in my patient's care. For instance, I have patients sent to me who have very complicated valve disease and we may put them through a full workup including catheterization to figure out what component of their symptoms is the valve disease and what component may be from other pathologies. It makes me more involved in disease management, not just doing the surgeries as they come."

(Part 2 of this article follows next month).

A session at the 2010 Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics conference co-sponsored by TCT, the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons centered on integrating cardiac surgery and interventional cardiology.

With such a shift being discussed, it is useful to consider the perspectives of two “early adopters" of this way of thinking - Dr. Mathew Williams at New York Presbyterian Hospital-Columbia and Dr. Michael Davidson at the Brigham and Women's Hospital. Both completed cardiac surgery training and then went on to pursue training in interventional cardiology. Each currently practices using a blend of techniques from both disciplines.

At the time they pursued interventional cardiology training, no formalized training programs for cardiac surgeons interested in interventional techniques existed. But both had observed the emergence of transcatheter valves.