User login

Career Choices: Psychiatric oncology

Editor’s note: Career Choices features a psychiatry resident/fellow interviewing a psychiatrist about why he or she has chosen a specific career path. The goal is to inform trainees about the various psychiatric career options, and to give them a feel for the pros and cons of the various paths.

In this Career Choices, Saeed Ahmed, MD, Addiction Psychiatry Fellow at Boston University, talked with William Pirl, MD, MPH, FACLP, FAPOS. Dr. Pirl is Associate Professor, Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School. He joined Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in 2018 as Vice Chair for Psychosocial Oncology, Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care. He is a past president of the American Psychosocial Oncology Society and North American Associate Editor for the journal Psycho-Oncology.

Dr. Ahmed: What made you choose the psychiatric oncology track, and how did your training lead you towards this path?

Dr. Pirl: I went to medical school thinking that I wanted to be a psychiatrist. However, I was really drawn to internal medicine, especially the process of sorting through medical differential diagnoses. I was deciding between applying for residency in medicine or psychiatry when I did an elective rotation in consultation-liaison (CL) psychiatry. Consultation-liaison psychiatry combined both medicine and psychiatry, which is exactly what I wanted to do. After residency, I wanted to do a CL fellowship outside of Boston, which is where I had done all of my medical education and training. One of my residency advisors suggested Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, and I ended up going there. On the first day of fellowship, I realized that I’d only be working with cancer over that year, which I had not really thought about beforehand. Luckily, I loved it, and over the year I realized that the work had tremendous impact and meaning.

Dr. Ahmed: What are some of the pros and cons of working in psychiatric oncology?

Dr. Pirl: Things that I think are pros might be cons for some people. Consults in psychiatric oncology tend to be more relationship-based than they might be in other CL subspecialties. Oncology clinicians want to know who they are referring their patients to, and they are used to team-based care. If you like practicing as part of a multidisciplinary team, this is a pro.

Psychiatric oncology has more focus on existential issues, which interests me more than some other things in psychiatry. Bearing witness to so much tragedy can be a con at times, but psychiatrists who do this work learn ways to manage this within themselves. Psychiatric oncology also offers many experiences where you can see how much impact you make. It’s rewarding to see results and get positive feedback from patients and their families.

Continue to: Lastly, this is...

Lastly, this is a historic time in oncology. Over the last 15 years, things are happening that I never thought I would live to see. Some patients who 10 or 15 years ago would have had an expected survival of 6 to 9 months are now living years. We are now at a point where we might not actually know a patient’s prognosis, which introduces a whole other layer of uncertainty in cancer. Working as a psychiatrist during this time of rapidly evolving care is amazing. Cancer care will look very different over the next decade.

Dr. Ahmed: Based on your personal experience, what should one consider when choosing a psychiatric oncology program?

Dr. Pirl: I trained in a time before CL was a certified subspecialty of psychiatry. At that time, programs could focus solely on cancer, which cannot be done now. Trainees need to have broader training in certified fellowships. If someone knows that they are interested in psychiatric oncology, there are 2 programs that they should consider: the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute track of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital CL fellowship, and the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center/New York Hospital CL fellowship. However, completing a CL fellowship will give someone the skills to do this work, even though they may not know all of the cancer content yet.

Dr. Ahmed: What are some of the career options and work settings in psychiatric oncology?

Dr. Pirl: There are many factors that make it difficult for psychiatrist to have a psychiatric oncology private practice. The amount of late cancellations and no-shows because of illness makes it hard to do this work without some institutional subsidy. Also, being able to communicate and work as a team with oncology providers is much easier if you are in the same place. Most psychiatrists who do psychiatric oncology work in a cancer center or hospital. Practice settings at those places include both inpatient and outpatient work. There is also a shortage of psychiatrists doing this work, which makes it easier to get a job and to advance into leadership roles.

Continue to: Dr. Ahmed...

Dr. Ahmed: What are some of the challenges in working in this field?

Dr. Pirl: One challenge is figuring out how to make sure you have income doing something that is not financially viable on its own. This is why most people work for cancer centers or hospitals and have some institutional subsidy for their work. Another challenge is access to care. There are not enough psychiatric resources for all the people with cancer who need them. Traditional referral-based models are getting harder and harder to manage. I think the emotional aspects of the work can also be challenging at times.

Dr. Ahmed: Where do you see the field going?

Dr. Pirl: Psychosocial care is now considered part of quality cancer care, and regulations require cancer centers to do certain aspects of it. This is leading to clinical growth and more integration into oncology. However, I am worried that we are not having enough psychiatry residents choose to do CL and/or psychiatric oncology. Some trainees are choosing to do a palliative care fellowship instead. When those trainees tell me why they want to do palliative care, I say that I do all of that and actually have much more time to do it because I am not managing constipation and vent settings. We need to do a better job of making trainees more aware of psychiatric oncology.

Dr. Ahmed: What advice do you have for those contemplating a career in psychiatric oncology?

Dr. Pirl: Please join the field. There is a shortage of psychiatrists who do this work, which is ironically one of the best and most meaningful jobs in psychiatry.

Editor’s note: Career Choices features a psychiatry resident/fellow interviewing a psychiatrist about why he or she has chosen a specific career path. The goal is to inform trainees about the various psychiatric career options, and to give them a feel for the pros and cons of the various paths.

In this Career Choices, Saeed Ahmed, MD, Addiction Psychiatry Fellow at Boston University, talked with William Pirl, MD, MPH, FACLP, FAPOS. Dr. Pirl is Associate Professor, Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School. He joined Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in 2018 as Vice Chair for Psychosocial Oncology, Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care. He is a past president of the American Psychosocial Oncology Society and North American Associate Editor for the journal Psycho-Oncology.

Dr. Ahmed: What made you choose the psychiatric oncology track, and how did your training lead you towards this path?

Dr. Pirl: I went to medical school thinking that I wanted to be a psychiatrist. However, I was really drawn to internal medicine, especially the process of sorting through medical differential diagnoses. I was deciding between applying for residency in medicine or psychiatry when I did an elective rotation in consultation-liaison (CL) psychiatry. Consultation-liaison psychiatry combined both medicine and psychiatry, which is exactly what I wanted to do. After residency, I wanted to do a CL fellowship outside of Boston, which is where I had done all of my medical education and training. One of my residency advisors suggested Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, and I ended up going there. On the first day of fellowship, I realized that I’d only be working with cancer over that year, which I had not really thought about beforehand. Luckily, I loved it, and over the year I realized that the work had tremendous impact and meaning.

Dr. Ahmed: What are some of the pros and cons of working in psychiatric oncology?

Dr. Pirl: Things that I think are pros might be cons for some people. Consults in psychiatric oncology tend to be more relationship-based than they might be in other CL subspecialties. Oncology clinicians want to know who they are referring their patients to, and they are used to team-based care. If you like practicing as part of a multidisciplinary team, this is a pro.

Psychiatric oncology has more focus on existential issues, which interests me more than some other things in psychiatry. Bearing witness to so much tragedy can be a con at times, but psychiatrists who do this work learn ways to manage this within themselves. Psychiatric oncology also offers many experiences where you can see how much impact you make. It’s rewarding to see results and get positive feedback from patients and their families.

Continue to: Lastly, this is...

Lastly, this is a historic time in oncology. Over the last 15 years, things are happening that I never thought I would live to see. Some patients who 10 or 15 years ago would have had an expected survival of 6 to 9 months are now living years. We are now at a point where we might not actually know a patient’s prognosis, which introduces a whole other layer of uncertainty in cancer. Working as a psychiatrist during this time of rapidly evolving care is amazing. Cancer care will look very different over the next decade.

Dr. Ahmed: Based on your personal experience, what should one consider when choosing a psychiatric oncology program?

Dr. Pirl: I trained in a time before CL was a certified subspecialty of psychiatry. At that time, programs could focus solely on cancer, which cannot be done now. Trainees need to have broader training in certified fellowships. If someone knows that they are interested in psychiatric oncology, there are 2 programs that they should consider: the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute track of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital CL fellowship, and the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center/New York Hospital CL fellowship. However, completing a CL fellowship will give someone the skills to do this work, even though they may not know all of the cancer content yet.

Dr. Ahmed: What are some of the career options and work settings in psychiatric oncology?

Dr. Pirl: There are many factors that make it difficult for psychiatrist to have a psychiatric oncology private practice. The amount of late cancellations and no-shows because of illness makes it hard to do this work without some institutional subsidy. Also, being able to communicate and work as a team with oncology providers is much easier if you are in the same place. Most psychiatrists who do psychiatric oncology work in a cancer center or hospital. Practice settings at those places include both inpatient and outpatient work. There is also a shortage of psychiatrists doing this work, which makes it easier to get a job and to advance into leadership roles.

Continue to: Dr. Ahmed...

Dr. Ahmed: What are some of the challenges in working in this field?

Dr. Pirl: One challenge is figuring out how to make sure you have income doing something that is not financially viable on its own. This is why most people work for cancer centers or hospitals and have some institutional subsidy for their work. Another challenge is access to care. There are not enough psychiatric resources for all the people with cancer who need them. Traditional referral-based models are getting harder and harder to manage. I think the emotional aspects of the work can also be challenging at times.

Dr. Ahmed: Where do you see the field going?

Dr. Pirl: Psychosocial care is now considered part of quality cancer care, and regulations require cancer centers to do certain aspects of it. This is leading to clinical growth and more integration into oncology. However, I am worried that we are not having enough psychiatry residents choose to do CL and/or psychiatric oncology. Some trainees are choosing to do a palliative care fellowship instead. When those trainees tell me why they want to do palliative care, I say that I do all of that and actually have much more time to do it because I am not managing constipation and vent settings. We need to do a better job of making trainees more aware of psychiatric oncology.

Dr. Ahmed: What advice do you have for those contemplating a career in psychiatric oncology?

Dr. Pirl: Please join the field. There is a shortage of psychiatrists who do this work, which is ironically one of the best and most meaningful jobs in psychiatry.

Editor’s note: Career Choices features a psychiatry resident/fellow interviewing a psychiatrist about why he or she has chosen a specific career path. The goal is to inform trainees about the various psychiatric career options, and to give them a feel for the pros and cons of the various paths.

In this Career Choices, Saeed Ahmed, MD, Addiction Psychiatry Fellow at Boston University, talked with William Pirl, MD, MPH, FACLP, FAPOS. Dr. Pirl is Associate Professor, Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School. He joined Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in 2018 as Vice Chair for Psychosocial Oncology, Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care. He is a past president of the American Psychosocial Oncology Society and North American Associate Editor for the journal Psycho-Oncology.

Dr. Ahmed: What made you choose the psychiatric oncology track, and how did your training lead you towards this path?

Dr. Pirl: I went to medical school thinking that I wanted to be a psychiatrist. However, I was really drawn to internal medicine, especially the process of sorting through medical differential diagnoses. I was deciding between applying for residency in medicine or psychiatry when I did an elective rotation in consultation-liaison (CL) psychiatry. Consultation-liaison psychiatry combined both medicine and psychiatry, which is exactly what I wanted to do. After residency, I wanted to do a CL fellowship outside of Boston, which is where I had done all of my medical education and training. One of my residency advisors suggested Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, and I ended up going there. On the first day of fellowship, I realized that I’d only be working with cancer over that year, which I had not really thought about beforehand. Luckily, I loved it, and over the year I realized that the work had tremendous impact and meaning.

Dr. Ahmed: What are some of the pros and cons of working in psychiatric oncology?

Dr. Pirl: Things that I think are pros might be cons for some people. Consults in psychiatric oncology tend to be more relationship-based than they might be in other CL subspecialties. Oncology clinicians want to know who they are referring their patients to, and they are used to team-based care. If you like practicing as part of a multidisciplinary team, this is a pro.

Psychiatric oncology has more focus on existential issues, which interests me more than some other things in psychiatry. Bearing witness to so much tragedy can be a con at times, but psychiatrists who do this work learn ways to manage this within themselves. Psychiatric oncology also offers many experiences where you can see how much impact you make. It’s rewarding to see results and get positive feedback from patients and their families.

Continue to: Lastly, this is...

Lastly, this is a historic time in oncology. Over the last 15 years, things are happening that I never thought I would live to see. Some patients who 10 or 15 years ago would have had an expected survival of 6 to 9 months are now living years. We are now at a point where we might not actually know a patient’s prognosis, which introduces a whole other layer of uncertainty in cancer. Working as a psychiatrist during this time of rapidly evolving care is amazing. Cancer care will look very different over the next decade.

Dr. Ahmed: Based on your personal experience, what should one consider when choosing a psychiatric oncology program?

Dr. Pirl: I trained in a time before CL was a certified subspecialty of psychiatry. At that time, programs could focus solely on cancer, which cannot be done now. Trainees need to have broader training in certified fellowships. If someone knows that they are interested in psychiatric oncology, there are 2 programs that they should consider: the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute track of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital CL fellowship, and the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center/New York Hospital CL fellowship. However, completing a CL fellowship will give someone the skills to do this work, even though they may not know all of the cancer content yet.

Dr. Ahmed: What are some of the career options and work settings in psychiatric oncology?

Dr. Pirl: There are many factors that make it difficult for psychiatrist to have a psychiatric oncology private practice. The amount of late cancellations and no-shows because of illness makes it hard to do this work without some institutional subsidy. Also, being able to communicate and work as a team with oncology providers is much easier if you are in the same place. Most psychiatrists who do psychiatric oncology work in a cancer center or hospital. Practice settings at those places include both inpatient and outpatient work. There is also a shortage of psychiatrists doing this work, which makes it easier to get a job and to advance into leadership roles.

Continue to: Dr. Ahmed...

Dr. Ahmed: What are some of the challenges in working in this field?

Dr. Pirl: One challenge is figuring out how to make sure you have income doing something that is not financially viable on its own. This is why most people work for cancer centers or hospitals and have some institutional subsidy for their work. Another challenge is access to care. There are not enough psychiatric resources for all the people with cancer who need them. Traditional referral-based models are getting harder and harder to manage. I think the emotional aspects of the work can also be challenging at times.

Dr. Ahmed: Where do you see the field going?

Dr. Pirl: Psychosocial care is now considered part of quality cancer care, and regulations require cancer centers to do certain aspects of it. This is leading to clinical growth and more integration into oncology. However, I am worried that we are not having enough psychiatry residents choose to do CL and/or psychiatric oncology. Some trainees are choosing to do a palliative care fellowship instead. When those trainees tell me why they want to do palliative care, I say that I do all of that and actually have much more time to do it because I am not managing constipation and vent settings. We need to do a better job of making trainees more aware of psychiatric oncology.

Dr. Ahmed: What advice do you have for those contemplating a career in psychiatric oncology?

Dr. Pirl: Please join the field. There is a shortage of psychiatrists who do this work, which is ironically one of the best and most meaningful jobs in psychiatry.

Feigning alcohol withdrawal symptoms can render the CIWA-Ar scale useless

The Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol–Revised (CIWA-Ar) scale is a well-established protocol that attempts to measure the degree of alcohol and benzodiazepine withdrawal. The CIWA-Ar scale measures 10 domains and indexes the severity of withdrawal on a scale from 0 to 67; scores >8 are generally considered to be indicative of at least mild-to-moderate withdrawal, and scores >20 represent significant withdrawal.1 Despite its common use in many medical settings, the CIWA-Ar scale has been impugned as a less-than-reliable index of true alcohol withdrawal2 and has the potential for misuse among ordering physicians.3 In this case report, I describe a malingering patient who intentionally and successfully feigned symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, which demonstrates that the purposeful reproduction of symptoms measured by the CIWA-Ar scale can render the protocol clinically useless.

CASE REPORT

Mr. G, a 63-year-old African-American man, was admitted to the general medical floor with a chief complaint of alcohol withdrawal. He had a history of alcohol use disorder, severe, and unspecified depression. He said he had been drinking a gallon of wine plus “a fifth” of vodka every day for the past 1.5 months. More than 1 year ago, he had been admitted for alcohol withdrawal with subsequent delirium tremens, but he denied having any other psychiatric history.

In the emergency department, Mr. G was given IV lorazepam, 6 mg total, for alcohol withdrawal. He was reported to be “scoring” on the CIWA-Ar scale with apparently uncontrollable tremulousness, visual hallucinations, and confusion. His vitals were within normal limits, his mean corpuscular volume and lipase level were within normal limits, and the rest of his presentation was largely unremarkable.

Once admitted to the general medical floor, he continued to receive benzodiazepines for what was documented as severe alcohol withdrawal. When clinical staff were not in the room, the patient was observed to be resting comfortably without tremulousness. When the patient was seen by the psychiatry consultation service, he produced full body tremulousness with marked shoulder and hip thrusting. His account of how much he had been drinking contradicted the amount he reported to other teams in the hospital. When the consulting psychiatrist appeared unimpressed by his full body jerking, the patient abruptly pointed to the corner of the room and yelled “What is that?” when nothing was there. When the primary medical team suggested to the patient that his vitals were within normal limits and he did not appear to be in true alcohol withdrawal, the patient escalated the degree of his full body jerking.

Over the next few days, the patient routinely would tell clinical staff “I’m having DTs.” He also specifically requested lorazepam. After consultation, the medical and psychiatry teams determined the patient was feigning symptoms of alcohol withdrawal. The lorazepam was discontinued, and the patient was discharged home with outpatient psychiatric follow-up.

Limitations of the CIWA-Ar scale

The CIWA-Ar scale is intended to guide the need for medications, such as benzodiazepines, to help mitigate symptoms of alcohol withdrawal. Symptom-triggered benzodiazepine treatment has been shown to be superior to fixed-schedule dosing.4 However, symptom-triggered treatment is problematic in the setting of feigned symptoms.

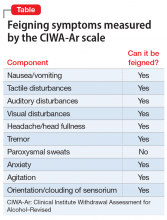

When psychiatrists and nurses calculate a CIWA-Ar score, they rely on both subjective accounts of a patient’s withdrawal severity as well as objective signs, such as vitals and a physical examination. Many of the elements included in the CIWA-Ar scale can be easily feigned (Table). Feigned alcohol withdrawal may fall into 2 categories: (1) the false reporting of subjective symptoms, and (2) the false portrayal of objective signs.

Continue to: The false reporting...

The false reporting of subjective symptoms can include the reported presence of nausea or vomiting, anxiety, tactile hallucinations, auditory hallucinations, headache or head fullness, and visual hallucinations. The false portrayal of objective signs can include the feigning of tremulousness, agitation, and confusion (eg, incorrectly answering orienting questions). In both categories, the simple presence of these signs or symptoms, whether falsely reported or falsely portrayed, would cause the patient to “score” on the CIWA-Ar scale.

Thus, the need to effectively rule out feigned symptoms is essential because inappropriate dosing of benzodiazepines can be dangerous, costly, and utilize limited hospital resources that could otherwise be diverted to a patient with a true medical or psychiatric illness. In these instances, it is crucial to pay close attention to vital signs because these are more reliable indices of withdrawal. A patient’s ability to purposefully feign symptoms of alcohol withdrawal highlights the limitations of the CIWA-Ar scale as a validated measure of alcohol withdrawal, and renders it effectively useless in the setting of either malingering or factitious disorder.

Resnick5 describes malingering as either pure malingering, partial malingering, or false imputation. Pure malingering refers to the feigning of a nonexistent disorder or illness. Partial malingering refers to the exaggeration of symptoms that are present, but to a lesser degree. False imputation refers to the attribution of symptoms from a separate disorder to one the patient knows is unrelated (eg, attributing chronic low back pain from a prior sports injury to a recent motor vehicle accident). In Mr. G’s case, he had multiple prior admissions for true, non-feigned alcohol withdrawal with subsequent delirium tremens. His knowledge of the signs and symptoms of alcohol withdrawal therefore helped him make calculated efforts to manipulate clinical staff in his quest to obtain benzodiazepines. Whether this was pure or partial malingering remained unclear because Mr. G’s true level of withdrawal could not be adequately assessed.

Potentially serious consequences

The CIWA-Ar scale is among the most widely used scales to determine the level of alcohol withdrawal and need for subsequent benzodiazepine treatment. However, its effective use is limited because it relies on subjective symptoms and objective signs that can be easily feigned or manipulated. In the setting of malingering or factitious disorder, when a patient is feigning symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, the CIWA-Ar scale may be rendered clinically useless. This can lead to dangerous iatrogenic adverse effects, lengthy and nontherapeutic hospital stays, and an increasing financial burden on health care systems.

1. Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, et al. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict. 1989;84(11):1353-1357.

2. Knight E, Lappalainen L. Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol–Revised might be an unreliable tool in the management of alcohol withdrawal. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63(9):691-695.

3. Hecksel KA, Bostwick JM, Jaeger TM, et al. Inappropriate use of symptom-triggered therapy for alcohol withdrawal in the general hospital. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(3):274-279.

4. Daeppen JB, Gache P, Landry U, et al. Symptom-triggered vs fixed-schedule doses of benzodiazepine for alcohol withdrawal: a randomized treatment trial. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(10):1117-1121.

5. Resnick PJ. The detection of malingered mental illness. Behav Sci Law. 1984;2(1):20-38.

The Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol–Revised (CIWA-Ar) scale is a well-established protocol that attempts to measure the degree of alcohol and benzodiazepine withdrawal. The CIWA-Ar scale measures 10 domains and indexes the severity of withdrawal on a scale from 0 to 67; scores >8 are generally considered to be indicative of at least mild-to-moderate withdrawal, and scores >20 represent significant withdrawal.1 Despite its common use in many medical settings, the CIWA-Ar scale has been impugned as a less-than-reliable index of true alcohol withdrawal2 and has the potential for misuse among ordering physicians.3 In this case report, I describe a malingering patient who intentionally and successfully feigned symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, which demonstrates that the purposeful reproduction of symptoms measured by the CIWA-Ar scale can render the protocol clinically useless.

CASE REPORT

Mr. G, a 63-year-old African-American man, was admitted to the general medical floor with a chief complaint of alcohol withdrawal. He had a history of alcohol use disorder, severe, and unspecified depression. He said he had been drinking a gallon of wine plus “a fifth” of vodka every day for the past 1.5 months. More than 1 year ago, he had been admitted for alcohol withdrawal with subsequent delirium tremens, but he denied having any other psychiatric history.

In the emergency department, Mr. G was given IV lorazepam, 6 mg total, for alcohol withdrawal. He was reported to be “scoring” on the CIWA-Ar scale with apparently uncontrollable tremulousness, visual hallucinations, and confusion. His vitals were within normal limits, his mean corpuscular volume and lipase level were within normal limits, and the rest of his presentation was largely unremarkable.

Once admitted to the general medical floor, he continued to receive benzodiazepines for what was documented as severe alcohol withdrawal. When clinical staff were not in the room, the patient was observed to be resting comfortably without tremulousness. When the patient was seen by the psychiatry consultation service, he produced full body tremulousness with marked shoulder and hip thrusting. His account of how much he had been drinking contradicted the amount he reported to other teams in the hospital. When the consulting psychiatrist appeared unimpressed by his full body jerking, the patient abruptly pointed to the corner of the room and yelled “What is that?” when nothing was there. When the primary medical team suggested to the patient that his vitals were within normal limits and he did not appear to be in true alcohol withdrawal, the patient escalated the degree of his full body jerking.

Over the next few days, the patient routinely would tell clinical staff “I’m having DTs.” He also specifically requested lorazepam. After consultation, the medical and psychiatry teams determined the patient was feigning symptoms of alcohol withdrawal. The lorazepam was discontinued, and the patient was discharged home with outpatient psychiatric follow-up.

Limitations of the CIWA-Ar scale

The CIWA-Ar scale is intended to guide the need for medications, such as benzodiazepines, to help mitigate symptoms of alcohol withdrawal. Symptom-triggered benzodiazepine treatment has been shown to be superior to fixed-schedule dosing.4 However, symptom-triggered treatment is problematic in the setting of feigned symptoms.

When psychiatrists and nurses calculate a CIWA-Ar score, they rely on both subjective accounts of a patient’s withdrawal severity as well as objective signs, such as vitals and a physical examination. Many of the elements included in the CIWA-Ar scale can be easily feigned (Table). Feigned alcohol withdrawal may fall into 2 categories: (1) the false reporting of subjective symptoms, and (2) the false portrayal of objective signs.

Continue to: The false reporting...

The false reporting of subjective symptoms can include the reported presence of nausea or vomiting, anxiety, tactile hallucinations, auditory hallucinations, headache or head fullness, and visual hallucinations. The false portrayal of objective signs can include the feigning of tremulousness, agitation, and confusion (eg, incorrectly answering orienting questions). In both categories, the simple presence of these signs or symptoms, whether falsely reported or falsely portrayed, would cause the patient to “score” on the CIWA-Ar scale.

Thus, the need to effectively rule out feigned symptoms is essential because inappropriate dosing of benzodiazepines can be dangerous, costly, and utilize limited hospital resources that could otherwise be diverted to a patient with a true medical or psychiatric illness. In these instances, it is crucial to pay close attention to vital signs because these are more reliable indices of withdrawal. A patient’s ability to purposefully feign symptoms of alcohol withdrawal highlights the limitations of the CIWA-Ar scale as a validated measure of alcohol withdrawal, and renders it effectively useless in the setting of either malingering or factitious disorder.

Resnick5 describes malingering as either pure malingering, partial malingering, or false imputation. Pure malingering refers to the feigning of a nonexistent disorder or illness. Partial malingering refers to the exaggeration of symptoms that are present, but to a lesser degree. False imputation refers to the attribution of symptoms from a separate disorder to one the patient knows is unrelated (eg, attributing chronic low back pain from a prior sports injury to a recent motor vehicle accident). In Mr. G’s case, he had multiple prior admissions for true, non-feigned alcohol withdrawal with subsequent delirium tremens. His knowledge of the signs and symptoms of alcohol withdrawal therefore helped him make calculated efforts to manipulate clinical staff in his quest to obtain benzodiazepines. Whether this was pure or partial malingering remained unclear because Mr. G’s true level of withdrawal could not be adequately assessed.

Potentially serious consequences

The CIWA-Ar scale is among the most widely used scales to determine the level of alcohol withdrawal and need for subsequent benzodiazepine treatment. However, its effective use is limited because it relies on subjective symptoms and objective signs that can be easily feigned or manipulated. In the setting of malingering or factitious disorder, when a patient is feigning symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, the CIWA-Ar scale may be rendered clinically useless. This can lead to dangerous iatrogenic adverse effects, lengthy and nontherapeutic hospital stays, and an increasing financial burden on health care systems.

The Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol–Revised (CIWA-Ar) scale is a well-established protocol that attempts to measure the degree of alcohol and benzodiazepine withdrawal. The CIWA-Ar scale measures 10 domains and indexes the severity of withdrawal on a scale from 0 to 67; scores >8 are generally considered to be indicative of at least mild-to-moderate withdrawal, and scores >20 represent significant withdrawal.1 Despite its common use in many medical settings, the CIWA-Ar scale has been impugned as a less-than-reliable index of true alcohol withdrawal2 and has the potential for misuse among ordering physicians.3 In this case report, I describe a malingering patient who intentionally and successfully feigned symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, which demonstrates that the purposeful reproduction of symptoms measured by the CIWA-Ar scale can render the protocol clinically useless.

CASE REPORT

Mr. G, a 63-year-old African-American man, was admitted to the general medical floor with a chief complaint of alcohol withdrawal. He had a history of alcohol use disorder, severe, and unspecified depression. He said he had been drinking a gallon of wine plus “a fifth” of vodka every day for the past 1.5 months. More than 1 year ago, he had been admitted for alcohol withdrawal with subsequent delirium tremens, but he denied having any other psychiatric history.

In the emergency department, Mr. G was given IV lorazepam, 6 mg total, for alcohol withdrawal. He was reported to be “scoring” on the CIWA-Ar scale with apparently uncontrollable tremulousness, visual hallucinations, and confusion. His vitals were within normal limits, his mean corpuscular volume and lipase level were within normal limits, and the rest of his presentation was largely unremarkable.

Once admitted to the general medical floor, he continued to receive benzodiazepines for what was documented as severe alcohol withdrawal. When clinical staff were not in the room, the patient was observed to be resting comfortably without tremulousness. When the patient was seen by the psychiatry consultation service, he produced full body tremulousness with marked shoulder and hip thrusting. His account of how much he had been drinking contradicted the amount he reported to other teams in the hospital. When the consulting psychiatrist appeared unimpressed by his full body jerking, the patient abruptly pointed to the corner of the room and yelled “What is that?” when nothing was there. When the primary medical team suggested to the patient that his vitals were within normal limits and he did not appear to be in true alcohol withdrawal, the patient escalated the degree of his full body jerking.

Over the next few days, the patient routinely would tell clinical staff “I’m having DTs.” He also specifically requested lorazepam. After consultation, the medical and psychiatry teams determined the patient was feigning symptoms of alcohol withdrawal. The lorazepam was discontinued, and the patient was discharged home with outpatient psychiatric follow-up.

Limitations of the CIWA-Ar scale

The CIWA-Ar scale is intended to guide the need for medications, such as benzodiazepines, to help mitigate symptoms of alcohol withdrawal. Symptom-triggered benzodiazepine treatment has been shown to be superior to fixed-schedule dosing.4 However, symptom-triggered treatment is problematic in the setting of feigned symptoms.

When psychiatrists and nurses calculate a CIWA-Ar score, they rely on both subjective accounts of a patient’s withdrawal severity as well as objective signs, such as vitals and a physical examination. Many of the elements included in the CIWA-Ar scale can be easily feigned (Table). Feigned alcohol withdrawal may fall into 2 categories: (1) the false reporting of subjective symptoms, and (2) the false portrayal of objective signs.

Continue to: The false reporting...

The false reporting of subjective symptoms can include the reported presence of nausea or vomiting, anxiety, tactile hallucinations, auditory hallucinations, headache or head fullness, and visual hallucinations. The false portrayal of objective signs can include the feigning of tremulousness, agitation, and confusion (eg, incorrectly answering orienting questions). In both categories, the simple presence of these signs or symptoms, whether falsely reported or falsely portrayed, would cause the patient to “score” on the CIWA-Ar scale.

Thus, the need to effectively rule out feigned symptoms is essential because inappropriate dosing of benzodiazepines can be dangerous, costly, and utilize limited hospital resources that could otherwise be diverted to a patient with a true medical or psychiatric illness. In these instances, it is crucial to pay close attention to vital signs because these are more reliable indices of withdrawal. A patient’s ability to purposefully feign symptoms of alcohol withdrawal highlights the limitations of the CIWA-Ar scale as a validated measure of alcohol withdrawal, and renders it effectively useless in the setting of either malingering or factitious disorder.

Resnick5 describes malingering as either pure malingering, partial malingering, or false imputation. Pure malingering refers to the feigning of a nonexistent disorder or illness. Partial malingering refers to the exaggeration of symptoms that are present, but to a lesser degree. False imputation refers to the attribution of symptoms from a separate disorder to one the patient knows is unrelated (eg, attributing chronic low back pain from a prior sports injury to a recent motor vehicle accident). In Mr. G’s case, he had multiple prior admissions for true, non-feigned alcohol withdrawal with subsequent delirium tremens. His knowledge of the signs and symptoms of alcohol withdrawal therefore helped him make calculated efforts to manipulate clinical staff in his quest to obtain benzodiazepines. Whether this was pure or partial malingering remained unclear because Mr. G’s true level of withdrawal could not be adequately assessed.

Potentially serious consequences

The CIWA-Ar scale is among the most widely used scales to determine the level of alcohol withdrawal and need for subsequent benzodiazepine treatment. However, its effective use is limited because it relies on subjective symptoms and objective signs that can be easily feigned or manipulated. In the setting of malingering or factitious disorder, when a patient is feigning symptoms of alcohol withdrawal, the CIWA-Ar scale may be rendered clinically useless. This can lead to dangerous iatrogenic adverse effects, lengthy and nontherapeutic hospital stays, and an increasing financial burden on health care systems.

1. Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, et al. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict. 1989;84(11):1353-1357.

2. Knight E, Lappalainen L. Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol–Revised might be an unreliable tool in the management of alcohol withdrawal. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63(9):691-695.

3. Hecksel KA, Bostwick JM, Jaeger TM, et al. Inappropriate use of symptom-triggered therapy for alcohol withdrawal in the general hospital. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(3):274-279.

4. Daeppen JB, Gache P, Landry U, et al. Symptom-triggered vs fixed-schedule doses of benzodiazepine for alcohol withdrawal: a randomized treatment trial. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(10):1117-1121.

5. Resnick PJ. The detection of malingered mental illness. Behav Sci Law. 1984;2(1):20-38.

1. Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, et al. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict. 1989;84(11):1353-1357.

2. Knight E, Lappalainen L. Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol–Revised might be an unreliable tool in the management of alcohol withdrawal. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63(9):691-695.

3. Hecksel KA, Bostwick JM, Jaeger TM, et al. Inappropriate use of symptom-triggered therapy for alcohol withdrawal in the general hospital. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(3):274-279.

4. Daeppen JB, Gache P, Landry U, et al. Symptom-triggered vs fixed-schedule doses of benzodiazepine for alcohol withdrawal: a randomized treatment trial. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(10):1117-1121.

5. Resnick PJ. The detection of malingered mental illness. Behav Sci Law. 1984;2(1):20-38.

A reflection on Ghana’s mental health system

In recent years, the delivery of mental health services in Ghana has expanded substantially, especially since the passing of the Mental Health Act in 2012. In this article, I reflect on my experience as a visiting psychiatry resident in August 2018 at 2 Ghanaian hospitals located in Accra and Navrongo. Evident strengths of the mental health system were family support for patients and the scope of psychiatrists, while the most prominent weakness was the inadequate funding. As treatment of mental illness expands, more funding, psychiatrists, and mental health workers will be critical for the continued success of Ghana’s mental health system.

Psychiatric treatment in Ghana

Ghana has a population of approximately 28 million people, yet the country has an estimated 18 to 25 psychiatrists, up from 11 psychiatrists in 2011.1-3 Compared with the United States, which has 10.54 psychiatrists per 100,000 people (approximately 1 psychiatrist per 9,500 people), Ghana has .058 psychiatrists per 100,000 people (approximately 1 psychiatrist per 1.7 million people).4 In Ghana, most psychiatric care is delivered by mental health nurses, community mental health officers (CMHOs), and clinical psychiatric officers; supervision by psychiatrists is limited.3 Due to low public awareness, a scarcity of clinicians, and limited access to diagnostic services and medications, individuals with psychiatric illness in Ghana are often stigmatized, undertreated, and mistreated. To address this, in March 2012, Ghana passed Mental Health Act 846, which established a mental health commission and outlined protections for individuals with mental health needs.5 Since then, the number of people seeking treatment and the number of clinicians have expanded, but there are still significant challenges, such as a lack of funding for medications and facilities, and limited clinicians.6

During my last year of psychiatry residency at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, I spent several weeks in Ghana at 2 institutions, observing and supervising the provision of psychiatric services. This was my first experience with the country’s health care system; therefore, my objectives were to:

- assess the current state of psychiatric services through observation and interviews with clinical staff

- provide instruction to clinicians in areas of need.

Two-thirds of my time was spent at the Accra Psychiatric Hospital, 1 of only 3 psychiatric hospitals in Ghana, all of which are located in the southern region of the country. The remainder of my time was spent at the Navrongo War Memorial Hospital in Ghana’s Northern Region.

The Accra Psychiatric Hospital is a sprawling complex near the center of the capital city. Every morning I walked through a large outdoor waiting area to the examination room, which was filled with at least 30 patients by 9

Navrongo War Memorial Hospital. There are no practicing psychiatrists in the northern region of the country; therefore, all mental health care is delivered by mental health nurses and CMHOs. CMHOs have 1 year of training plus a minimum of 2 years of service. They focus on identifying psychiatric cases in the community and coordinating treatment. Nurses have prescribing rights. A psychiatrist should be scheduled to visit the various districts in the region every 6 months to provide supervision, but this is not always feasible.

When I visited, I was the only psychiatrist who had been to this hospital in more than 1 year. During my time there, I reviewed the treatment protocols and gave lectures on the management of psychiatric emergencies and motivational interviewing, because addiction to alcohol and tramadol are 2 of the most pressing mental health problems in the country.7 I also saw patients with nurses, and supervised them on their assessment and treatment.

Continue to: In Ghana...

In Ghana, psychiatric services are often delivered using the community mental health model, in which many patients are visited in their homes. One morning, we went to a prayer camp to see if there were any individuals who would benefit from psychiatric services. There were no cases that day, but during the visit I sat under a tree where a few years before it was not uncommon to find a person who was psychotic or agitated chained to the tree. Several years of outreach by the local nurses has resulted in the camp leaders better recognizing mental illness early and contacting the nurses, as opposed to locking a person in chains for an extended period.

On one occasion, we answered a crisis call where a person experiencing a psychotic episode had locked himself in his house. The team talked with the individual through a locked screen door for 30 minutes, after which he eventually came out of the home to speak with us. A few days later, the patient accepted fluphenazine decanoate injection at his home. Two weeks later, he came to the outpatient clinic to continue treatment. Four months later, the patient was still in treatment and had started an apprenticeship for repairing cars.

As I was walking out of the hospital on my last day, I was called back to see a woman with a seizure who had been brought to the hospital. Unfortunately, there was no more diazepam in stock with which to treat her. This event highlighted the lack of resources available in this setting.

3 Take-home messages

My experience at both hospitals led me to reflect on 3 important factors impacting the mental health system in Ghana:

Family support. For at least 80% of appointments, patients were accompanied by family members or friends. The family hierarchy is still dominant in the Ghanaian culture, and clinicians often need the buy-in of the family, especially when financial support is required. More often than not, families enhanced patients’ treatment, but in some instances, they were a barrier.

Continue to: The types of cases

The types of cases. Most of the patients coming to both hospitals had diagnoses of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, substance use disorder, or epilepsy. My impression was that patients or family members sought treatment for disorders that were conspicuous. I saw <5 cases of depression or anxiety. I wonder if this was because:

- patients with these disorders were referred to psychologists

- patients sought out faith-based treatment

- there was a lower incidence of these disorders, or these disorders were detected less frequently.

Inadequate funding. Despite the clinicians’ astute observations and diagnoses, they faced challenges, including a lack of access to medications because pharmacies were out of stock, or the patient or hospital could not afford the medication. At times, these challenges resulted in patients admitted to the hospital not receiving medications. When Mental Health Act 846 was implemented, it was widely purported that mental health care would be available to everyone, but the funding mechanism was not firmly established.8,9 Currently, laboratory workup, mental health treatment, and medications are not covered by health insurance, and government funding for mental health is insufficient. Therefore, in most areas, the entire cost burden of psychiatric care falls on patients and their families, or on hospitals.

Making progress despite barriers

In her inaugural address, former American Psychiatric Association President Altha J. Stewart, MD, named expanding the organization’s work in global mental health as one of her 3 primary goals.10 There are several means by which American psychiatrists can support the work of psychiatrists in Ghana and elsewhere. One way is by helping the mental health commission and other entities within the country petition the government and health insurance companies to expand coverage for mental health services. Teleconferencing, in which psychiatrists in Ghana or other parts of the world provide supervision to mid-level clinicians, has been piloted in other countries such as Liberia and could be implemented to address the critical shortages of psychiatrists in certain regions.11

In the past 7 years, Ghana has made significant strides in destigmatizing mental illness, and as a result more individuals are seeking treatment and more clinicians at all levels are being trained. Despite significant barriers, physicians, nurses, and other mental health workers deliver empathic and evidence-based treatment in a manner that defies the mental health system’s current limitations.

1. Ofori-Atta A, Attafuah J, Jack H, et al. Joining psychiatric care and faith healing in a prayer camp in Ghana: randomised trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;212(1):34-41.

2. Ghana has only 18 psychiatrists; experts beg government for more funds. GhanaWeb. https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/Ghana-has-only-18-psychiatrists-experts-beg-government-for-more-funds-591732. Published October 17, 2017. Accessed July 24, 2019.

3. Agyapong VIO, Farren C, McAuliffe E. Improving Ghana’s mental healthcare through task-shifting-psychiatrists and health policy directors perceptions about government’s commitment and the role of community mental health workers. Global Health. 2016;12:57.

4. World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory data repository. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.MHHR?lang=en. Published April 25, 2019. Accessed July 24, 2019.

5. Walker GH, Osei A. Mental health law in Ghana. BJPsych Int. 2017;14(2):38-39.

6. Doku VC, Wusu-Takyi A, Awakame J. Implementing the Mental Health Act in Ghana: any challenges ahead? Ghana Med J. 2012;46(4):241-250.

7. Kissiedu E. High dose Tramadol floods market. Business Day. http://businessdayghana.com/high-dose-tramadol-floods-market/. Published September 25, 2017. Accessed July 24, 2019.

8. Badu E, O’Brien AP, Mitchell R. An integrative review of potential enablers and barriers to accessing mental health services in Ghana. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):110.

9. Ghana mental health care delivery risks collapse for lack of funds. News Ghana. https://www.newsghana.com.gh/ghana-mental-health-care-delivery-risks-collapse-for-lack-of-funds/. Published May 29, 2018. Accessed July 24, 2019.

10. Stewart AJ. Response to the Presidential Address. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):726-727.

11. Katz, CL, Washington FB, Sacco M, et al. A resident-based telepsychiatry supervision pilot program in Liberia. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;70(3):243-246.

In recent years, the delivery of mental health services in Ghana has expanded substantially, especially since the passing of the Mental Health Act in 2012. In this article, I reflect on my experience as a visiting psychiatry resident in August 2018 at 2 Ghanaian hospitals located in Accra and Navrongo. Evident strengths of the mental health system were family support for patients and the scope of psychiatrists, while the most prominent weakness was the inadequate funding. As treatment of mental illness expands, more funding, psychiatrists, and mental health workers will be critical for the continued success of Ghana’s mental health system.

Psychiatric treatment in Ghana

Ghana has a population of approximately 28 million people, yet the country has an estimated 18 to 25 psychiatrists, up from 11 psychiatrists in 2011.1-3 Compared with the United States, which has 10.54 psychiatrists per 100,000 people (approximately 1 psychiatrist per 9,500 people), Ghana has .058 psychiatrists per 100,000 people (approximately 1 psychiatrist per 1.7 million people).4 In Ghana, most psychiatric care is delivered by mental health nurses, community mental health officers (CMHOs), and clinical psychiatric officers; supervision by psychiatrists is limited.3 Due to low public awareness, a scarcity of clinicians, and limited access to diagnostic services and medications, individuals with psychiatric illness in Ghana are often stigmatized, undertreated, and mistreated. To address this, in March 2012, Ghana passed Mental Health Act 846, which established a mental health commission and outlined protections for individuals with mental health needs.5 Since then, the number of people seeking treatment and the number of clinicians have expanded, but there are still significant challenges, such as a lack of funding for medications and facilities, and limited clinicians.6

During my last year of psychiatry residency at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, I spent several weeks in Ghana at 2 institutions, observing and supervising the provision of psychiatric services. This was my first experience with the country’s health care system; therefore, my objectives were to:

- assess the current state of psychiatric services through observation and interviews with clinical staff

- provide instruction to clinicians in areas of need.

Two-thirds of my time was spent at the Accra Psychiatric Hospital, 1 of only 3 psychiatric hospitals in Ghana, all of which are located in the southern region of the country. The remainder of my time was spent at the Navrongo War Memorial Hospital in Ghana’s Northern Region.

The Accra Psychiatric Hospital is a sprawling complex near the center of the capital city. Every morning I walked through a large outdoor waiting area to the examination room, which was filled with at least 30 patients by 9

Navrongo War Memorial Hospital. There are no practicing psychiatrists in the northern region of the country; therefore, all mental health care is delivered by mental health nurses and CMHOs. CMHOs have 1 year of training plus a minimum of 2 years of service. They focus on identifying psychiatric cases in the community and coordinating treatment. Nurses have prescribing rights. A psychiatrist should be scheduled to visit the various districts in the region every 6 months to provide supervision, but this is not always feasible.

When I visited, I was the only psychiatrist who had been to this hospital in more than 1 year. During my time there, I reviewed the treatment protocols and gave lectures on the management of psychiatric emergencies and motivational interviewing, because addiction to alcohol and tramadol are 2 of the most pressing mental health problems in the country.7 I also saw patients with nurses, and supervised them on their assessment and treatment.

Continue to: In Ghana...

In Ghana, psychiatric services are often delivered using the community mental health model, in which many patients are visited in their homes. One morning, we went to a prayer camp to see if there were any individuals who would benefit from psychiatric services. There were no cases that day, but during the visit I sat under a tree where a few years before it was not uncommon to find a person who was psychotic or agitated chained to the tree. Several years of outreach by the local nurses has resulted in the camp leaders better recognizing mental illness early and contacting the nurses, as opposed to locking a person in chains for an extended period.

On one occasion, we answered a crisis call where a person experiencing a psychotic episode had locked himself in his house. The team talked with the individual through a locked screen door for 30 minutes, after which he eventually came out of the home to speak with us. A few days later, the patient accepted fluphenazine decanoate injection at his home. Two weeks later, he came to the outpatient clinic to continue treatment. Four months later, the patient was still in treatment and had started an apprenticeship for repairing cars.

As I was walking out of the hospital on my last day, I was called back to see a woman with a seizure who had been brought to the hospital. Unfortunately, there was no more diazepam in stock with which to treat her. This event highlighted the lack of resources available in this setting.

3 Take-home messages

My experience at both hospitals led me to reflect on 3 important factors impacting the mental health system in Ghana:

Family support. For at least 80% of appointments, patients were accompanied by family members or friends. The family hierarchy is still dominant in the Ghanaian culture, and clinicians often need the buy-in of the family, especially when financial support is required. More often than not, families enhanced patients’ treatment, but in some instances, they were a barrier.

Continue to: The types of cases

The types of cases. Most of the patients coming to both hospitals had diagnoses of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, substance use disorder, or epilepsy. My impression was that patients or family members sought treatment for disorders that were conspicuous. I saw <5 cases of depression or anxiety. I wonder if this was because:

- patients with these disorders were referred to psychologists

- patients sought out faith-based treatment

- there was a lower incidence of these disorders, or these disorders were detected less frequently.

Inadequate funding. Despite the clinicians’ astute observations and diagnoses, they faced challenges, including a lack of access to medications because pharmacies were out of stock, or the patient or hospital could not afford the medication. At times, these challenges resulted in patients admitted to the hospital not receiving medications. When Mental Health Act 846 was implemented, it was widely purported that mental health care would be available to everyone, but the funding mechanism was not firmly established.8,9 Currently, laboratory workup, mental health treatment, and medications are not covered by health insurance, and government funding for mental health is insufficient. Therefore, in most areas, the entire cost burden of psychiatric care falls on patients and their families, or on hospitals.

Making progress despite barriers

In her inaugural address, former American Psychiatric Association President Altha J. Stewart, MD, named expanding the organization’s work in global mental health as one of her 3 primary goals.10 There are several means by which American psychiatrists can support the work of psychiatrists in Ghana and elsewhere. One way is by helping the mental health commission and other entities within the country petition the government and health insurance companies to expand coverage for mental health services. Teleconferencing, in which psychiatrists in Ghana or other parts of the world provide supervision to mid-level clinicians, has been piloted in other countries such as Liberia and could be implemented to address the critical shortages of psychiatrists in certain regions.11

In the past 7 years, Ghana has made significant strides in destigmatizing mental illness, and as a result more individuals are seeking treatment and more clinicians at all levels are being trained. Despite significant barriers, physicians, nurses, and other mental health workers deliver empathic and evidence-based treatment in a manner that defies the mental health system’s current limitations.

In recent years, the delivery of mental health services in Ghana has expanded substantially, especially since the passing of the Mental Health Act in 2012. In this article, I reflect on my experience as a visiting psychiatry resident in August 2018 at 2 Ghanaian hospitals located in Accra and Navrongo. Evident strengths of the mental health system were family support for patients and the scope of psychiatrists, while the most prominent weakness was the inadequate funding. As treatment of mental illness expands, more funding, psychiatrists, and mental health workers will be critical for the continued success of Ghana’s mental health system.

Psychiatric treatment in Ghana

Ghana has a population of approximately 28 million people, yet the country has an estimated 18 to 25 psychiatrists, up from 11 psychiatrists in 2011.1-3 Compared with the United States, which has 10.54 psychiatrists per 100,000 people (approximately 1 psychiatrist per 9,500 people), Ghana has .058 psychiatrists per 100,000 people (approximately 1 psychiatrist per 1.7 million people).4 In Ghana, most psychiatric care is delivered by mental health nurses, community mental health officers (CMHOs), and clinical psychiatric officers; supervision by psychiatrists is limited.3 Due to low public awareness, a scarcity of clinicians, and limited access to diagnostic services and medications, individuals with psychiatric illness in Ghana are often stigmatized, undertreated, and mistreated. To address this, in March 2012, Ghana passed Mental Health Act 846, which established a mental health commission and outlined protections for individuals with mental health needs.5 Since then, the number of people seeking treatment and the number of clinicians have expanded, but there are still significant challenges, such as a lack of funding for medications and facilities, and limited clinicians.6

During my last year of psychiatry residency at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, I spent several weeks in Ghana at 2 institutions, observing and supervising the provision of psychiatric services. This was my first experience with the country’s health care system; therefore, my objectives were to:

- assess the current state of psychiatric services through observation and interviews with clinical staff

- provide instruction to clinicians in areas of need.

Two-thirds of my time was spent at the Accra Psychiatric Hospital, 1 of only 3 psychiatric hospitals in Ghana, all of which are located in the southern region of the country. The remainder of my time was spent at the Navrongo War Memorial Hospital in Ghana’s Northern Region.

The Accra Psychiatric Hospital is a sprawling complex near the center of the capital city. Every morning I walked through a large outdoor waiting area to the examination room, which was filled with at least 30 patients by 9

Navrongo War Memorial Hospital. There are no practicing psychiatrists in the northern region of the country; therefore, all mental health care is delivered by mental health nurses and CMHOs. CMHOs have 1 year of training plus a minimum of 2 years of service. They focus on identifying psychiatric cases in the community and coordinating treatment. Nurses have prescribing rights. A psychiatrist should be scheduled to visit the various districts in the region every 6 months to provide supervision, but this is not always feasible.

When I visited, I was the only psychiatrist who had been to this hospital in more than 1 year. During my time there, I reviewed the treatment protocols and gave lectures on the management of psychiatric emergencies and motivational interviewing, because addiction to alcohol and tramadol are 2 of the most pressing mental health problems in the country.7 I also saw patients with nurses, and supervised them on their assessment and treatment.

Continue to: In Ghana...

In Ghana, psychiatric services are often delivered using the community mental health model, in which many patients are visited in their homes. One morning, we went to a prayer camp to see if there were any individuals who would benefit from psychiatric services. There were no cases that day, but during the visit I sat under a tree where a few years before it was not uncommon to find a person who was psychotic or agitated chained to the tree. Several years of outreach by the local nurses has resulted in the camp leaders better recognizing mental illness early and contacting the nurses, as opposed to locking a person in chains for an extended period.

On one occasion, we answered a crisis call where a person experiencing a psychotic episode had locked himself in his house. The team talked with the individual through a locked screen door for 30 minutes, after which he eventually came out of the home to speak with us. A few days later, the patient accepted fluphenazine decanoate injection at his home. Two weeks later, he came to the outpatient clinic to continue treatment. Four months later, the patient was still in treatment and had started an apprenticeship for repairing cars.

As I was walking out of the hospital on my last day, I was called back to see a woman with a seizure who had been brought to the hospital. Unfortunately, there was no more diazepam in stock with which to treat her. This event highlighted the lack of resources available in this setting.

3 Take-home messages

My experience at both hospitals led me to reflect on 3 important factors impacting the mental health system in Ghana:

Family support. For at least 80% of appointments, patients were accompanied by family members or friends. The family hierarchy is still dominant in the Ghanaian culture, and clinicians often need the buy-in of the family, especially when financial support is required. More often than not, families enhanced patients’ treatment, but in some instances, they were a barrier.

Continue to: The types of cases

The types of cases. Most of the patients coming to both hospitals had diagnoses of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, substance use disorder, or epilepsy. My impression was that patients or family members sought treatment for disorders that were conspicuous. I saw <5 cases of depression or anxiety. I wonder if this was because:

- patients with these disorders were referred to psychologists

- patients sought out faith-based treatment

- there was a lower incidence of these disorders, or these disorders were detected less frequently.

Inadequate funding. Despite the clinicians’ astute observations and diagnoses, they faced challenges, including a lack of access to medications because pharmacies were out of stock, or the patient or hospital could not afford the medication. At times, these challenges resulted in patients admitted to the hospital not receiving medications. When Mental Health Act 846 was implemented, it was widely purported that mental health care would be available to everyone, but the funding mechanism was not firmly established.8,9 Currently, laboratory workup, mental health treatment, and medications are not covered by health insurance, and government funding for mental health is insufficient. Therefore, in most areas, the entire cost burden of psychiatric care falls on patients and their families, or on hospitals.

Making progress despite barriers

In her inaugural address, former American Psychiatric Association President Altha J. Stewart, MD, named expanding the organization’s work in global mental health as one of her 3 primary goals.10 There are several means by which American psychiatrists can support the work of psychiatrists in Ghana and elsewhere. One way is by helping the mental health commission and other entities within the country petition the government and health insurance companies to expand coverage for mental health services. Teleconferencing, in which psychiatrists in Ghana or other parts of the world provide supervision to mid-level clinicians, has been piloted in other countries such as Liberia and could be implemented to address the critical shortages of psychiatrists in certain regions.11

In the past 7 years, Ghana has made significant strides in destigmatizing mental illness, and as a result more individuals are seeking treatment and more clinicians at all levels are being trained. Despite significant barriers, physicians, nurses, and other mental health workers deliver empathic and evidence-based treatment in a manner that defies the mental health system’s current limitations.

1. Ofori-Atta A, Attafuah J, Jack H, et al. Joining psychiatric care and faith healing in a prayer camp in Ghana: randomised trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;212(1):34-41.

2. Ghana has only 18 psychiatrists; experts beg government for more funds. GhanaWeb. https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/Ghana-has-only-18-psychiatrists-experts-beg-government-for-more-funds-591732. Published October 17, 2017. Accessed July 24, 2019.

3. Agyapong VIO, Farren C, McAuliffe E. Improving Ghana’s mental healthcare through task-shifting-psychiatrists and health policy directors perceptions about government’s commitment and the role of community mental health workers. Global Health. 2016;12:57.

4. World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory data repository. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.MHHR?lang=en. Published April 25, 2019. Accessed July 24, 2019.

5. Walker GH, Osei A. Mental health law in Ghana. BJPsych Int. 2017;14(2):38-39.

6. Doku VC, Wusu-Takyi A, Awakame J. Implementing the Mental Health Act in Ghana: any challenges ahead? Ghana Med J. 2012;46(4):241-250.

7. Kissiedu E. High dose Tramadol floods market. Business Day. http://businessdayghana.com/high-dose-tramadol-floods-market/. Published September 25, 2017. Accessed July 24, 2019.

8. Badu E, O’Brien AP, Mitchell R. An integrative review of potential enablers and barriers to accessing mental health services in Ghana. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):110.

9. Ghana mental health care delivery risks collapse for lack of funds. News Ghana. https://www.newsghana.com.gh/ghana-mental-health-care-delivery-risks-collapse-for-lack-of-funds/. Published May 29, 2018. Accessed July 24, 2019.

10. Stewart AJ. Response to the Presidential Address. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):726-727.

11. Katz, CL, Washington FB, Sacco M, et al. A resident-based telepsychiatry supervision pilot program in Liberia. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;70(3):243-246.

1. Ofori-Atta A, Attafuah J, Jack H, et al. Joining psychiatric care and faith healing in a prayer camp in Ghana: randomised trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;212(1):34-41.

2. Ghana has only 18 psychiatrists; experts beg government for more funds. GhanaWeb. https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/Ghana-has-only-18-psychiatrists-experts-beg-government-for-more-funds-591732. Published October 17, 2017. Accessed July 24, 2019.

3. Agyapong VIO, Farren C, McAuliffe E. Improving Ghana’s mental healthcare through task-shifting-psychiatrists and health policy directors perceptions about government’s commitment and the role of community mental health workers. Global Health. 2016;12:57.

4. World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory data repository. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.MHHR?lang=en. Published April 25, 2019. Accessed July 24, 2019.

5. Walker GH, Osei A. Mental health law in Ghana. BJPsych Int. 2017;14(2):38-39.

6. Doku VC, Wusu-Takyi A, Awakame J. Implementing the Mental Health Act in Ghana: any challenges ahead? Ghana Med J. 2012;46(4):241-250.

7. Kissiedu E. High dose Tramadol floods market. Business Day. http://businessdayghana.com/high-dose-tramadol-floods-market/. Published September 25, 2017. Accessed July 24, 2019.

8. Badu E, O’Brien AP, Mitchell R. An integrative review of potential enablers and barriers to accessing mental health services in Ghana. Health Res Policy Syst. 2018;16(1):110.

9. Ghana mental health care delivery risks collapse for lack of funds. News Ghana. https://www.newsghana.com.gh/ghana-mental-health-care-delivery-risks-collapse-for-lack-of-funds/. Published May 29, 2018. Accessed July 24, 2019.

10. Stewart AJ. Response to the Presidential Address. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):726-727.

11. Katz, CL, Washington FB, Sacco M, et al. A resident-based telepsychiatry supervision pilot program in Liberia. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;70(3):243-246.

The challenges of caring for a physician with a mental illness

A physician’s mental health is important for the delivery of quality health care to his/her patients. Early identification and treatment of physicians with mental illnesses is challenging because physicians may neglect their own mental health due to the associated stigma, time constraints, or uncertainty regarding where to seek help. Physicians often worry about whom to confide in and harbor a fear that others will doubt his/her competence after recovery.1 Physicians have higher rates of suicide than the general population.2 According to data from the National Violent Death Reporting System, a diagnosed mental illness or a job problem significantly contribute to suicide among physicians.3 Additionally, physicians also have high rates of substance use and affective disorders.1,4

Here, we present the case of a physician we treated on an inpatient psychiatry unit who stirred profound emotions in us as trainees, and discuss how we managed this complicated scenario.

CASE REPORT

Dr. P, a 35-year-old male endocrinologist, was admitted to our inpatient psychiatry unit with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, manic, severe, with psychotic features. Earlier that day, Dr. P had walked out of his private outpatient practice where he still had several appointments. After he had been missing for several hours, he was picked up by the police. Dr. P had 2 prior psychiatric admissions; the last one had occurred >10 years ago. A few weeks before this admission, he stopped taking lithium, while continuing escitalopram. He had not been keeping his appointments with his outpatient psychiatrist.

At admission, Dr. P had pressured speech, grandiose delusions, an expansive affect, and aggressive behavior. He was responding to internal stimuli with no insight into his illness. He was evasive when asked about hallucinations. Dr. P believed he was superior in intelligence and physical prowess to everyone in the emergency department (ED), and for that reason, the ED staff was persecuting him. His urine toxicology was negative.

On the inpatient unit, because Dr. P exhibited posturing, mutism, and negativism, catatonia associated with bipolar disorder was added to his diagnosis. For the first 2 days, his catatonia was managed with oral lorazepam, 2 mg twice daily. Dr. P was also observed giving medical advice to other patients on the unit, and was told to stop. Throughout his hospitalization, he dictated his own treatment and would frequently debate with his treatment team on the pharmacologic basis for treatment decisions, asserting his expertise as a physician and claiming to have a general clinical knowledge of the acute management of bipolar disorder.

Dr. P was eventually stabilized on oral lithium, 450 mg twice daily, and aripiprazole, 10 mg/d. He also received oral clonazepam, as needed for acute agitation, which was eventually tapered and discontinued. He gradually responded to treatment, and demonstrated improved insight. The treatment team met with Dr. P’s parents, who also were physicians, to discuss treatment goals, management considerations, and an aftercare plan. After spending 8 days in the hospital, Dr. P was discharged home to the care of his immediate family, and instructed to follow up with his outpatient psychiatrist. We do not know if he resumed clinical duties.

Managing an extremely knowledgeable patient

During his hospitalization, Dr. P frequently challenged our clinical knowledge; he would repeatedly remind us that he was a physician and that we were still trainees, which caused us to second-guess ourselves. Eventually, the attending physician on our team was able to impress upon Dr. P the clearly established roles of the treatment team and the patient. It was also important to maintain open communication channels with Dr. P and his family, and to address his anxiety by discussing the treatment plan in detail.5

Continue to: Although his queries on medication...

Although his queries on medication pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics were daunting, we empathized with him, recognizing that his knowledge invariably contributed to his anxiety. We engaged with Dr. P and his parents and elaborated on the rationale behind treatment decisions. This earned his trust and tremendously facilitated his recovery.

We were also cautious about using benzodiazepines to treat Dr. P’s catatonia because we were concerned that his knowledge could aid him in feigning symptoms to obtain these medications. Physicians have a high rate of prescription medication abuse, mainly opiates and benzodiazepines.2 The abuse of prescription medications by physicians is related to several psychological and psychiatric factors, including anxiety, depression, stress at work, personality problems, loss of loved ones, and pain. While treating physician patients, treatment decisions that include the use of opiates and benzodiazepines should be carefully considered.

A complicated scenario

Managing a physician patient can be a rewarding experience; however, there are several factors that can impact the experience, including: