User login

Delay can reduce TEVAR problems with type B dissections

NEW YORK – Patients with acute type B aortic dissections who are treated with thoracic endovascular aortic repair within 48 hours of symptom onset are more than three times as likely to have a severe complication as are those who are treated between 2 and 6 weeks after initial presentation, according to Dr. Nimesh D. Desai.

"There has been a dramatic increase in survival of patients managed with TEVAR for life-threatening complications of type B dissection versus any other therapy. Recently, [FDA] approval of two devices in the U.S. (Gore cTAG and Medtronic Valiant Captiva TEVAR grafts) has really opened up the field of inquiry into the optimal timing of TEVAR in the nonemergent, non–life-threatening complicated type B dissection patient. In the current study, we analyzed the impact of timing of intervention," Dr. Desai said at the meeting sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

Between 2005 and 2012, 317 people were admitted to the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, for acute (less than 6 weeks) type B dissections, said Dr. Desai. He reviewed the outcomes for 132 patients who had undergone TEVAR, dividing them into three groups according to the timing of the procedure: acute/early (TEVAR within 48 hours of symptom onset), n = 70; acute/delayed (TEVAR 48 hours to 14 days following symptom onset), n = 44; and subacute (TEVAR 2-6 weeks following symptom onset), n = 18. Patients in all three groups were generally between 63 and 65 years old. Most were men who had histories of severe hypertension and smoking. About 10% had a previous stroke.

Those in the acute/early group were more likely to have undergone TEVAR for life-threatening conditions. For instance, 43.28% of the acute/early group had a contained rupture vs. 25% of the acute/delayed and 11.11% of the subacute patients, a significant difference. The acute/early group also had higher rates of frank rupture and clinical malperfusion than did the other groups.

In contrast, 56% of the subacute group underwent TEVAR because they manifested "softer indications" of impending rupture or radiographic malperfusion, which were not considered to be as emergent. Three-quarters of the subacute group had already been discharged home and were readmitted for the procedure, reported Dr. Desai, who is at the University of Pennsylvania.

The overall rate of severe postoperative complications was 39% in the acute/early group, 27% in the acute/delayed group, and 11.1% in the subacute group, a significant difference.

In-house mortality was 8.5% in the acute/early group (nine patients), 4.5% in the acute/delayed group (three), and 0 in the subacute group, a nonsignificant difference. Similar, but nonsignificant trends were found in 30-day mortality (11.7%, 6.8%, and 0%) and stroke (5.6%, 4.6%, and 0%).

An opposite trend toward higher rates of paralysis was observed in the subacute group (7.04%, 4.5%, and 9.5%, respectively, in the three groups).

The incidence of retrograde type A aortic dissection was 8.5% in the acute/early, 6.8% in the acute/delayed, and 4.7% in the subacute groups. "Retrograde type A dissections are an iatrogenic disease caused by stenting type B dissections," said Dr. Desai. "They almost never happen with any other type of stent graft category."

He said that in his experience, the risk increases with excessive oversizing of stents and the dissections tend to occur at the interface between the native aorta and stent graft. In addition, he noted, many of the dissections occur a year or more after the original dissection.

"Delayed intervention appears to lower the risk of complications of TEVAR for aortic dissection in patients who are stable enough to wait. Our practice is to wait 10-14 days for remodeling indications," said Dr. Desai. Type B patients who are initially managed medically should be followed closely, he said, because they are at risk for the onset of new indications that might require TEVAR.

Operator experience and adequate case planning are critical when treating patients in the setting of acute or subacute type A dissections, Dr. Desai said, adding that the development of devices specific for dissections, rather than those designed for aneurysm pathologies, may lead to fewer complications.

Dr. Desai is a primary investigator for Food and Drug Administration TEVAR trials for W.L. Gore and Associates, Medtronic, and Cook Medical.

NEW YORK – Patients with acute type B aortic dissections who are treated with thoracic endovascular aortic repair within 48 hours of symptom onset are more than three times as likely to have a severe complication as are those who are treated between 2 and 6 weeks after initial presentation, according to Dr. Nimesh D. Desai.

"There has been a dramatic increase in survival of patients managed with TEVAR for life-threatening complications of type B dissection versus any other therapy. Recently, [FDA] approval of two devices in the U.S. (Gore cTAG and Medtronic Valiant Captiva TEVAR grafts) has really opened up the field of inquiry into the optimal timing of TEVAR in the nonemergent, non–life-threatening complicated type B dissection patient. In the current study, we analyzed the impact of timing of intervention," Dr. Desai said at the meeting sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

Between 2005 and 2012, 317 people were admitted to the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, for acute (less than 6 weeks) type B dissections, said Dr. Desai. He reviewed the outcomes for 132 patients who had undergone TEVAR, dividing them into three groups according to the timing of the procedure: acute/early (TEVAR within 48 hours of symptom onset), n = 70; acute/delayed (TEVAR 48 hours to 14 days following symptom onset), n = 44; and subacute (TEVAR 2-6 weeks following symptom onset), n = 18. Patients in all three groups were generally between 63 and 65 years old. Most were men who had histories of severe hypertension and smoking. About 10% had a previous stroke.

Those in the acute/early group were more likely to have undergone TEVAR for life-threatening conditions. For instance, 43.28% of the acute/early group had a contained rupture vs. 25% of the acute/delayed and 11.11% of the subacute patients, a significant difference. The acute/early group also had higher rates of frank rupture and clinical malperfusion than did the other groups.

In contrast, 56% of the subacute group underwent TEVAR because they manifested "softer indications" of impending rupture or radiographic malperfusion, which were not considered to be as emergent. Three-quarters of the subacute group had already been discharged home and were readmitted for the procedure, reported Dr. Desai, who is at the University of Pennsylvania.

The overall rate of severe postoperative complications was 39% in the acute/early group, 27% in the acute/delayed group, and 11.1% in the subacute group, a significant difference.

In-house mortality was 8.5% in the acute/early group (nine patients), 4.5% in the acute/delayed group (three), and 0 in the subacute group, a nonsignificant difference. Similar, but nonsignificant trends were found in 30-day mortality (11.7%, 6.8%, and 0%) and stroke (5.6%, 4.6%, and 0%).

An opposite trend toward higher rates of paralysis was observed in the subacute group (7.04%, 4.5%, and 9.5%, respectively, in the three groups).

The incidence of retrograde type A aortic dissection was 8.5% in the acute/early, 6.8% in the acute/delayed, and 4.7% in the subacute groups. "Retrograde type A dissections are an iatrogenic disease caused by stenting type B dissections," said Dr. Desai. "They almost never happen with any other type of stent graft category."

He said that in his experience, the risk increases with excessive oversizing of stents and the dissections tend to occur at the interface between the native aorta and stent graft. In addition, he noted, many of the dissections occur a year or more after the original dissection.

"Delayed intervention appears to lower the risk of complications of TEVAR for aortic dissection in patients who are stable enough to wait. Our practice is to wait 10-14 days for remodeling indications," said Dr. Desai. Type B patients who are initially managed medically should be followed closely, he said, because they are at risk for the onset of new indications that might require TEVAR.

Operator experience and adequate case planning are critical when treating patients in the setting of acute or subacute type A dissections, Dr. Desai said, adding that the development of devices specific for dissections, rather than those designed for aneurysm pathologies, may lead to fewer complications.

Dr. Desai is a primary investigator for Food and Drug Administration TEVAR trials for W.L. Gore and Associates, Medtronic, and Cook Medical.

NEW YORK – Patients with acute type B aortic dissections who are treated with thoracic endovascular aortic repair within 48 hours of symptom onset are more than three times as likely to have a severe complication as are those who are treated between 2 and 6 weeks after initial presentation, according to Dr. Nimesh D. Desai.

"There has been a dramatic increase in survival of patients managed with TEVAR for life-threatening complications of type B dissection versus any other therapy. Recently, [FDA] approval of two devices in the U.S. (Gore cTAG and Medtronic Valiant Captiva TEVAR grafts) has really opened up the field of inquiry into the optimal timing of TEVAR in the nonemergent, non–life-threatening complicated type B dissection patient. In the current study, we analyzed the impact of timing of intervention," Dr. Desai said at the meeting sponsored by the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

Between 2005 and 2012, 317 people were admitted to the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, for acute (less than 6 weeks) type B dissections, said Dr. Desai. He reviewed the outcomes for 132 patients who had undergone TEVAR, dividing them into three groups according to the timing of the procedure: acute/early (TEVAR within 48 hours of symptom onset), n = 70; acute/delayed (TEVAR 48 hours to 14 days following symptom onset), n = 44; and subacute (TEVAR 2-6 weeks following symptom onset), n = 18. Patients in all three groups were generally between 63 and 65 years old. Most were men who had histories of severe hypertension and smoking. About 10% had a previous stroke.

Those in the acute/early group were more likely to have undergone TEVAR for life-threatening conditions. For instance, 43.28% of the acute/early group had a contained rupture vs. 25% of the acute/delayed and 11.11% of the subacute patients, a significant difference. The acute/early group also had higher rates of frank rupture and clinical malperfusion than did the other groups.

In contrast, 56% of the subacute group underwent TEVAR because they manifested "softer indications" of impending rupture or radiographic malperfusion, which were not considered to be as emergent. Three-quarters of the subacute group had already been discharged home and were readmitted for the procedure, reported Dr. Desai, who is at the University of Pennsylvania.

The overall rate of severe postoperative complications was 39% in the acute/early group, 27% in the acute/delayed group, and 11.1% in the subacute group, a significant difference.

In-house mortality was 8.5% in the acute/early group (nine patients), 4.5% in the acute/delayed group (three), and 0 in the subacute group, a nonsignificant difference. Similar, but nonsignificant trends were found in 30-day mortality (11.7%, 6.8%, and 0%) and stroke (5.6%, 4.6%, and 0%).

An opposite trend toward higher rates of paralysis was observed in the subacute group (7.04%, 4.5%, and 9.5%, respectively, in the three groups).

The incidence of retrograde type A aortic dissection was 8.5% in the acute/early, 6.8% in the acute/delayed, and 4.7% in the subacute groups. "Retrograde type A dissections are an iatrogenic disease caused by stenting type B dissections," said Dr. Desai. "They almost never happen with any other type of stent graft category."

He said that in his experience, the risk increases with excessive oversizing of stents and the dissections tend to occur at the interface between the native aorta and stent graft. In addition, he noted, many of the dissections occur a year or more after the original dissection.

"Delayed intervention appears to lower the risk of complications of TEVAR for aortic dissection in patients who are stable enough to wait. Our practice is to wait 10-14 days for remodeling indications," said Dr. Desai. Type B patients who are initially managed medically should be followed closely, he said, because they are at risk for the onset of new indications that might require TEVAR.

Operator experience and adequate case planning are critical when treating patients in the setting of acute or subacute type A dissections, Dr. Desai said, adding that the development of devices specific for dissections, rather than those designed for aneurysm pathologies, may lead to fewer complications.

Dr. Desai is a primary investigator for Food and Drug Administration TEVAR trials for W.L. Gore and Associates, Medtronic, and Cook Medical.

Key clinical point: Delayed intervention appears to lower the risk of complications of TEVAR for aortic dissection in patients who are stable enough to wait.

Major finding: The overall risk of severe complications was more than threefold higher in patients who underwent TEVAR for acute type B aortic dissections within 48 hours of initial presentation, compared with those whose treatment could be delayed until 2-6 weeks after symptom onset.

Data source: A single-center, retrospective registry analysis of 317 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Desai said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

TAVR beat surgery in high-risk aortic stenosis patients

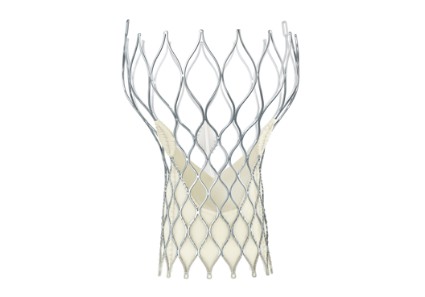

WASHINGTON - A first in transcatheter aortic valve replacement trials, the CoreValve prosthesis was superior to surgical valve replacement in patients with severe aortic stenosis at increased surgical risk, showing a significantly lower risk of mortality 1 year later.

In the U.S. CoreValve High Risk Study, a prospective randomized controlled study of almost 800 patients, the rate of all-cause mortality at 1 year, the primary endpoint, was 14.2% among those in the transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) group, compared with 19.1% among those in the surgery group, a statistically significant difference that represented a 26% survival benefit at 1 year for the CoreValve, Dr. David H. Adams reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

This is the first prospective, randomized study to show superiority for transcatheter valve therapy over surgery, and "there's no study or trial that I'm aware of that's suggested that TAVR patients would have a superior survival outcome," Dr. Adams of Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, said in an interview. Based on these results, he said he expects that TAVR "will increasingly become the alternative of choice for patients" at this level of risk.

The study was the high-risk arm of the U.S. CoreValve pivotal trial. The CoreValve self-expanding prosthesis was approved in January 2014 by the Food and Drug Administration for use in extreme risk patients, based on the results of the extreme risk cohort of patients. The data from the study in the high-risk trial are being reviewed at the FDA, according to the manufacturer, Medtronic.

The study compared the safety and effectiveness of TAVR with the CoreValve device to surgical valve replacement in 795 patients at 45 U.S. centers. The patients had severe aortic stenosis, had New York Heart Association class II heart failure or higher, and were judged to have at least a 15% risk of death within 30 days after surgery and less than a 50% risk of death or irreversible complications within 30 days after surgery. Their mean age was about age 83 years, almost half were females, most had class NYHA class III HF, and cardiac risk factors included coronary artery disease (in about two-thirds), previous coronary artery bypass surgery (about 30%), a previous MI (about 25%), and almost all had heart failure.

At 1 year, a composite of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (death from any cause, MI, any stroke, or reintervention), a secondary endpoint, was significantly lower among those on TAVR (20.4%) vs. the surgical group (27.3%). The rate of any stroke at 30 days was 4.9% in TAVR patients and 6.2% in the surgical group; and at 1 year, those rates were 8.8% and 12.6%, respectively; neither difference was statistically significant. Major vascular complications and permanent pacemaker implantations were significantly higher in the TAVR group (22.3% at 1 year, vs. 11.3% in the surgical group). In the TAVR group, there were five cases of cardiac perforation; there were no perforations in the surgical group.

Patients are being followed through 5 years. The 2-year mortality data are encouraging, with continued separation of the all-cause mortality curves, although the numbers are still small, Dr. Adams said.

More patients in the trial refused surgical valve replacement after randomization and the mortality rate within 30 days after surgery was 4.5%, which was lower than the rate specified for inclusion in the study, which was 15% or higher, so the patients may have been at a lower risk than planned, he said.

During the discussion, the inevitable comparisons to the results of the Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves A (PARTNER A) study were raised. In PARTNER A, which compared the safety and effectiveness of the balloon-expandable SAPIEN Transcatheter Heart Valve to aortic valve replacement surgery in high-risk patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis, found no difference in mortality between the two arms and an increase in cerebrovascular events in the TAVR arm.

Dr. Adams said that different characteristics of the device in the two trials are possible explanations as to why the TAVR results were superior to surgery in the CoreValve study, and not in PARTNER A. "The size of the catheter as well as perhaps the self-expanding nature of the device both could help explain that," he said.

While patient risk was assessed differently in the studies, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons scores of the patients were different, "we're confident these were patients at increased risk for surgery," he added.

The study was published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine on March 29 (2014 March 29 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1400590]).

The study is funded by the CoreValve manufacturer, Medtronic. Dr. Adams disclosed receiving grant support from Medtronic during the conduct of the study and other support from Medtronic and Edwards Lifesciences outside the submitted work.

WASHINGTON - A first in transcatheter aortic valve replacement trials, the CoreValve prosthesis was superior to surgical valve replacement in patients with severe aortic stenosis at increased surgical risk, showing a significantly lower risk of mortality 1 year later.

In the U.S. CoreValve High Risk Study, a prospective randomized controlled study of almost 800 patients, the rate of all-cause mortality at 1 year, the primary endpoint, was 14.2% among those in the transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) group, compared with 19.1% among those in the surgery group, a statistically significant difference that represented a 26% survival benefit at 1 year for the CoreValve, Dr. David H. Adams reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

This is the first prospective, randomized study to show superiority for transcatheter valve therapy over surgery, and "there's no study or trial that I'm aware of that's suggested that TAVR patients would have a superior survival outcome," Dr. Adams of Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, said in an interview. Based on these results, he said he expects that TAVR "will increasingly become the alternative of choice for patients" at this level of risk.

The study was the high-risk arm of the U.S. CoreValve pivotal trial. The CoreValve self-expanding prosthesis was approved in January 2014 by the Food and Drug Administration for use in extreme risk patients, based on the results of the extreme risk cohort of patients. The data from the study in the high-risk trial are being reviewed at the FDA, according to the manufacturer, Medtronic.

The study compared the safety and effectiveness of TAVR with the CoreValve device to surgical valve replacement in 795 patients at 45 U.S. centers. The patients had severe aortic stenosis, had New York Heart Association class II heart failure or higher, and were judged to have at least a 15% risk of death within 30 days after surgery and less than a 50% risk of death or irreversible complications within 30 days after surgery. Their mean age was about age 83 years, almost half were females, most had class NYHA class III HF, and cardiac risk factors included coronary artery disease (in about two-thirds), previous coronary artery bypass surgery (about 30%), a previous MI (about 25%), and almost all had heart failure.

At 1 year, a composite of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (death from any cause, MI, any stroke, or reintervention), a secondary endpoint, was significantly lower among those on TAVR (20.4%) vs. the surgical group (27.3%). The rate of any stroke at 30 days was 4.9% in TAVR patients and 6.2% in the surgical group; and at 1 year, those rates were 8.8% and 12.6%, respectively; neither difference was statistically significant. Major vascular complications and permanent pacemaker implantations were significantly higher in the TAVR group (22.3% at 1 year, vs. 11.3% in the surgical group). In the TAVR group, there were five cases of cardiac perforation; there were no perforations in the surgical group.

Patients are being followed through 5 years. The 2-year mortality data are encouraging, with continued separation of the all-cause mortality curves, although the numbers are still small, Dr. Adams said.

More patients in the trial refused surgical valve replacement after randomization and the mortality rate within 30 days after surgery was 4.5%, which was lower than the rate specified for inclusion in the study, which was 15% or higher, so the patients may have been at a lower risk than planned, he said.

During the discussion, the inevitable comparisons to the results of the Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves A (PARTNER A) study were raised. In PARTNER A, which compared the safety and effectiveness of the balloon-expandable SAPIEN Transcatheter Heart Valve to aortic valve replacement surgery in high-risk patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis, found no difference in mortality between the two arms and an increase in cerebrovascular events in the TAVR arm.

Dr. Adams said that different characteristics of the device in the two trials are possible explanations as to why the TAVR results were superior to surgery in the CoreValve study, and not in PARTNER A. "The size of the catheter as well as perhaps the self-expanding nature of the device both could help explain that," he said.

While patient risk was assessed differently in the studies, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons scores of the patients were different, "we're confident these were patients at increased risk for surgery," he added.

The study was published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine on March 29 (2014 March 29 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1400590]).

The study is funded by the CoreValve manufacturer, Medtronic. Dr. Adams disclosed receiving grant support from Medtronic during the conduct of the study and other support from Medtronic and Edwards Lifesciences outside the submitted work.

WASHINGTON - A first in transcatheter aortic valve replacement trials, the CoreValve prosthesis was superior to surgical valve replacement in patients with severe aortic stenosis at increased surgical risk, showing a significantly lower risk of mortality 1 year later.

In the U.S. CoreValve High Risk Study, a prospective randomized controlled study of almost 800 patients, the rate of all-cause mortality at 1 year, the primary endpoint, was 14.2% among those in the transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) group, compared with 19.1% among those in the surgery group, a statistically significant difference that represented a 26% survival benefit at 1 year for the CoreValve, Dr. David H. Adams reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

This is the first prospective, randomized study to show superiority for transcatheter valve therapy over surgery, and "there's no study or trial that I'm aware of that's suggested that TAVR patients would have a superior survival outcome," Dr. Adams of Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, said in an interview. Based on these results, he said he expects that TAVR "will increasingly become the alternative of choice for patients" at this level of risk.

The study was the high-risk arm of the U.S. CoreValve pivotal trial. The CoreValve self-expanding prosthesis was approved in January 2014 by the Food and Drug Administration for use in extreme risk patients, based on the results of the extreme risk cohort of patients. The data from the study in the high-risk trial are being reviewed at the FDA, according to the manufacturer, Medtronic.

The study compared the safety and effectiveness of TAVR with the CoreValve device to surgical valve replacement in 795 patients at 45 U.S. centers. The patients had severe aortic stenosis, had New York Heart Association class II heart failure or higher, and were judged to have at least a 15% risk of death within 30 days after surgery and less than a 50% risk of death or irreversible complications within 30 days after surgery. Their mean age was about age 83 years, almost half were females, most had class NYHA class III HF, and cardiac risk factors included coronary artery disease (in about two-thirds), previous coronary artery bypass surgery (about 30%), a previous MI (about 25%), and almost all had heart failure.

At 1 year, a composite of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (death from any cause, MI, any stroke, or reintervention), a secondary endpoint, was significantly lower among those on TAVR (20.4%) vs. the surgical group (27.3%). The rate of any stroke at 30 days was 4.9% in TAVR patients and 6.2% in the surgical group; and at 1 year, those rates were 8.8% and 12.6%, respectively; neither difference was statistically significant. Major vascular complications and permanent pacemaker implantations were significantly higher in the TAVR group (22.3% at 1 year, vs. 11.3% in the surgical group). In the TAVR group, there were five cases of cardiac perforation; there were no perforations in the surgical group.

Patients are being followed through 5 years. The 2-year mortality data are encouraging, with continued separation of the all-cause mortality curves, although the numbers are still small, Dr. Adams said.

More patients in the trial refused surgical valve replacement after randomization and the mortality rate within 30 days after surgery was 4.5%, which was lower than the rate specified for inclusion in the study, which was 15% or higher, so the patients may have been at a lower risk than planned, he said.

During the discussion, the inevitable comparisons to the results of the Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves A (PARTNER A) study were raised. In PARTNER A, which compared the safety and effectiveness of the balloon-expandable SAPIEN Transcatheter Heart Valve to aortic valve replacement surgery in high-risk patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis, found no difference in mortality between the two arms and an increase in cerebrovascular events in the TAVR arm.

Dr. Adams said that different characteristics of the device in the two trials are possible explanations as to why the TAVR results were superior to surgery in the CoreValve study, and not in PARTNER A. "The size of the catheter as well as perhaps the self-expanding nature of the device both could help explain that," he said.

While patient risk was assessed differently in the studies, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons scores of the patients were different, "we're confident these were patients at increased risk for surgery," he added.

The study was published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine on March 29 (2014 March 29 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1400590]).

The study is funded by the CoreValve manufacturer, Medtronic. Dr. Adams disclosed receiving grant support from Medtronic during the conduct of the study and other support from Medtronic and Edwards Lifesciences outside the submitted work.

Major finding: All-cause mortality was 14.2% among high-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis 1 year after TAVR with a self-expanding aortic valve bioprosthesis, vs. 19.1% among those who had surgical aortic valve replacement, a highly statistically significant difference.

Data source: The multicenter prospective U.S. study compared survival at 1 year in 795 patients at high risk for surgery who were randomized to TAVR with the CoreValve device or surgical aortic valve replacement.

Disclosures: The study is funded by the CoreValve manufacturer, Medtronic. Dr. Adams disclosed receiving grant support from Medtronic during the conduct of the study and other support from Medtronic and Edwards Lifesciences outside the study.

DECAAF: Assess extent of fibrosis before AF ablation

For patients scheduled to undergo AF catheter ablation, estimating the extent of atrial fibrosis using delayed enhancement MRI can help distinguish those likely to respond from patients likely to have recurrent arrhythmia, according to a report published online Feb. 4 in JAMA.

In the prospective, observational DECAAF (Delayed-Enhancement MRI Determinant of Successful Radiofrequency Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation) study, 260 such patients (mean age, 59 years) underwent quantification of left atrial fibrosis via delayed enhancement MRI with gadolinium at 15 medical centers in six countries, before undergoing AF ablation. These centers had varying levels of experience with cardiac imaging and used different ablation procedures, said Dr. Nassir F. Marrouche, director of the comprehensive arrhythmia and research management center, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and his associates.

Four categories of fibrosis were used: involvement of less than 10% of the atrial wall (stage 1, 49 patients), 10%-19% of the atrial wall (stage 2, 107 patients), 20%-29% of the atrial wall (stage 3, 80 patients), and 30% or more of the atrial wall (stage 4, 24 patients). The estimated percentage of atrial fibrosis strongly correlated with arrhythmia recurrence at 1 year, even after the data were adjusted to account for variables such as patient age and sex; the presence of hypertension, heart failure, mitral valve disease, or diabetes; and the type of AF (paroxysmal vs persistent).

The hazard ratio for recurrent arrhythmia was 1.06 for every 1% increase in the extent of atrial fibrosis (JAMA 2014 Feb. 4 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3]).

This is the first multicenter study to demonstrate the feasibility and potential clinical value of quantifying the degree of AF fibrosis using delayed enhancement MRI before performing ablation, offering a noninvasive, effective method for determining which patients are likely to benefit and which should avoid the procedure, Dr. Marrouche and his associates said.

The JAMA report expands on results presented at the annual meeting of the Heart Rhythm Society last year.

The study was funded by the Comprehensive Arrhythmia and Research Management Center at the University of Utah and the George S. and Dolores Dore Eccles Foundation. Dr. Marrouche reported owning stock and being named in two patents licensed to Marrek; his associates reported numerous ties to industry sources.

For patients scheduled to undergo AF catheter ablation, estimating the extent of atrial fibrosis using delayed enhancement MRI can help distinguish those likely to respond from patients likely to have recurrent arrhythmia, according to a report published online Feb. 4 in JAMA.

In the prospective, observational DECAAF (Delayed-Enhancement MRI Determinant of Successful Radiofrequency Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation) study, 260 such patients (mean age, 59 years) underwent quantification of left atrial fibrosis via delayed enhancement MRI with gadolinium at 15 medical centers in six countries, before undergoing AF ablation. These centers had varying levels of experience with cardiac imaging and used different ablation procedures, said Dr. Nassir F. Marrouche, director of the comprehensive arrhythmia and research management center, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and his associates.

Four categories of fibrosis were used: involvement of less than 10% of the atrial wall (stage 1, 49 patients), 10%-19% of the atrial wall (stage 2, 107 patients), 20%-29% of the atrial wall (stage 3, 80 patients), and 30% or more of the atrial wall (stage 4, 24 patients). The estimated percentage of atrial fibrosis strongly correlated with arrhythmia recurrence at 1 year, even after the data were adjusted to account for variables such as patient age and sex; the presence of hypertension, heart failure, mitral valve disease, or diabetes; and the type of AF (paroxysmal vs persistent).

The hazard ratio for recurrent arrhythmia was 1.06 for every 1% increase in the extent of atrial fibrosis (JAMA 2014 Feb. 4 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3]).

This is the first multicenter study to demonstrate the feasibility and potential clinical value of quantifying the degree of AF fibrosis using delayed enhancement MRI before performing ablation, offering a noninvasive, effective method for determining which patients are likely to benefit and which should avoid the procedure, Dr. Marrouche and his associates said.

The JAMA report expands on results presented at the annual meeting of the Heart Rhythm Society last year.

The study was funded by the Comprehensive Arrhythmia and Research Management Center at the University of Utah and the George S. and Dolores Dore Eccles Foundation. Dr. Marrouche reported owning stock and being named in two patents licensed to Marrek; his associates reported numerous ties to industry sources.

For patients scheduled to undergo AF catheter ablation, estimating the extent of atrial fibrosis using delayed enhancement MRI can help distinguish those likely to respond from patients likely to have recurrent arrhythmia, according to a report published online Feb. 4 in JAMA.

In the prospective, observational DECAAF (Delayed-Enhancement MRI Determinant of Successful Radiofrequency Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation) study, 260 such patients (mean age, 59 years) underwent quantification of left atrial fibrosis via delayed enhancement MRI with gadolinium at 15 medical centers in six countries, before undergoing AF ablation. These centers had varying levels of experience with cardiac imaging and used different ablation procedures, said Dr. Nassir F. Marrouche, director of the comprehensive arrhythmia and research management center, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and his associates.

Four categories of fibrosis were used: involvement of less than 10% of the atrial wall (stage 1, 49 patients), 10%-19% of the atrial wall (stage 2, 107 patients), 20%-29% of the atrial wall (stage 3, 80 patients), and 30% or more of the atrial wall (stage 4, 24 patients). The estimated percentage of atrial fibrosis strongly correlated with arrhythmia recurrence at 1 year, even after the data were adjusted to account for variables such as patient age and sex; the presence of hypertension, heart failure, mitral valve disease, or diabetes; and the type of AF (paroxysmal vs persistent).

The hazard ratio for recurrent arrhythmia was 1.06 for every 1% increase in the extent of atrial fibrosis (JAMA 2014 Feb. 4 [doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3]).

This is the first multicenter study to demonstrate the feasibility and potential clinical value of quantifying the degree of AF fibrosis using delayed enhancement MRI before performing ablation, offering a noninvasive, effective method for determining which patients are likely to benefit and which should avoid the procedure, Dr. Marrouche and his associates said.

The JAMA report expands on results presented at the annual meeting of the Heart Rhythm Society last year.

The study was funded by the Comprehensive Arrhythmia and Research Management Center at the University of Utah and the George S. and Dolores Dore Eccles Foundation. Dr. Marrouche reported owning stock and being named in two patents licensed to Marrek; his associates reported numerous ties to industry sources.

Frailty assessment central to TAVR decision

SNOWMASS, COLO.– Transcatheter aortic valve replacement in nonsurgical candidates with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis carries a hefty price tag of $116,500 per quality-adjusted life-year gained over medical management.

That’s the bottom line in a cost-effectiveness study led by cardiologist Dr. Mark A. Hlatky. The investigators applied data on the costs and benefits of transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) as documented in the landmark PARTNER (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves) trial in their Markov model involving a hypothetical patient cohort. The estimated incremental cost-effectiveness of $116,500 per quality-adjusted life-year gained is well in excess of the $50,000 figure widely accepted by health policy makers as defining a cutoff for cost-effective therapy.

In this cost-effectiveness analysis (Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2013;6:419-28), TAVR boosted life expectancy by roughly 11 months, from 2.08 years with medical therapy to 2.93 years. Quality-adjusted life expectancy rose from 1.19 to 1.93 years. TAVR also resulted in 1.4 fewer hospitalizations than with medical management. However, undergoing TAVR rather than medical management raised the lifetime stroke risk from 1% to 11% and increased lifetime health care costs from $83,600 to $169,100, reported the group led by Dr. Hlatky, professor of health research and policy and also professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University.

"This is a fascinating study," Dr. Karen P. Alexander said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass. "I think the lesson here is that futility from a cost perspective is also something that should be in the discussion" regarding TAVR vs. medical therapy in patients with inoperable aortic stenosis.

She highlighted the Hlatky study in discussing the key role frailty assessment plays in considering TAVR. The study showed that the cost-effectiveness of TAVR is greater in patients with a lower burden of noncardiac disease, which is another way saying "those who are less frail."

This conclusion underscores a statement in the 2012 American College of Cardiology/American Association for Thoracic Surgery/Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions/Society of Thoracic Surgeons expert consensus document on TAVR paraphrased by Dr. Alexander: Frailty will assume central importance in patient selection for TAVR by virtue of the extensive comorbidities in this population. Existing models do not have predictive variables of interest in high-risk patients. (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012;59:1200-54).

Dr. Alexander of Duke University in Durham, N.C., said frailty is important when considering TAVR because it has been shown to be associated with increased rates of post-TAVR 30-day morbidity and mortality, prolonged hospital length of stay, and 1-year mortality.

She defined frailty as a multisystem impairment resulting in reduced physiologic reserve and increased vulnerability to stress. Frailty is a physiologic phenotype associated with slow gait, weakness, weight loss, exhaustion, and a low daily activity level.

While the degree of a patient’s frailty is an important consideration in deciding on TAVR vs. medical management, frailty per se is no contraindication to the procedure. Indeed, the prevalence of frailty as defined simply by a baseline 5-meter walk time in excess of 6 seconds was 72% among the 7,710 TAVR patients, mean age 84 years, included in the recent first report of the comprehensive national STS/ACC Transcatheter Valve Therapy Registry (JAMA 2013;310:2069-77). That’s nearly twice the 38% prevalence among community-dwelling 85-year-olds, Dr. Alexander noted, citing data from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging (CMAJ 2011;183:e487-94).

More than 20 different frailty risk scores are now in circulation. Dr. Alexander is particularly enthusiastic about the frailty risk tool developed as part of the ACC’s new Championing Care for the Patient With Aortic Stenosis Initiative. It efficiently assesses five domains of frailty – slowness, weakness, malnutrition, inactivity with loss of independence, and malnutrition – and generates a clinically useful qualitative frailty rating. A patient with a high frailty score may not have sufficient life expectancy to obtain the benefits of TAVR.

With regard to treatment futility, Dr. Alexander observed that it can be defined as either lack of medical efficacy as judged by physicians or as lack of meaningful survival as judged by a patient’s personal values. Yet one in four Americans aged 75 years or older has given little or no thought to their own wishes for end-of-life medical therapy, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey.

The telephone survey, conducted last spring, included a representative sample of 1,994 U.S. adults. While 47% of respondents aged 75 years or older indicated they had given their own wishes for end-of-life medical care a great deal of thought, 25% said they had given the matter "not much or none." Reflection on those personal wishes needs to be part of the physician/patient discussion about TAVR, according to Dr. Alexander.

With regard to general views on end-of-life therapy, 74% of surveyed individuals age 75 and up declared there should be circumstances in which a patient should be allowed to die. Another 22% said medical staff should do everything possible to save a patient’s life under all circumstances.

Dr. Alexander reported serving as a consultant to Gilead and Pozen.

SNOWMASS, COLO.– Transcatheter aortic valve replacement in nonsurgical candidates with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis carries a hefty price tag of $116,500 per quality-adjusted life-year gained over medical management.

That’s the bottom line in a cost-effectiveness study led by cardiologist Dr. Mark A. Hlatky. The investigators applied data on the costs and benefits of transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) as documented in the landmark PARTNER (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves) trial in their Markov model involving a hypothetical patient cohort. The estimated incremental cost-effectiveness of $116,500 per quality-adjusted life-year gained is well in excess of the $50,000 figure widely accepted by health policy makers as defining a cutoff for cost-effective therapy.

In this cost-effectiveness analysis (Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2013;6:419-28), TAVR boosted life expectancy by roughly 11 months, from 2.08 years with medical therapy to 2.93 years. Quality-adjusted life expectancy rose from 1.19 to 1.93 years. TAVR also resulted in 1.4 fewer hospitalizations than with medical management. However, undergoing TAVR rather than medical management raised the lifetime stroke risk from 1% to 11% and increased lifetime health care costs from $83,600 to $169,100, reported the group led by Dr. Hlatky, professor of health research and policy and also professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University.

"This is a fascinating study," Dr. Karen P. Alexander said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass. "I think the lesson here is that futility from a cost perspective is also something that should be in the discussion" regarding TAVR vs. medical therapy in patients with inoperable aortic stenosis.

She highlighted the Hlatky study in discussing the key role frailty assessment plays in considering TAVR. The study showed that the cost-effectiveness of TAVR is greater in patients with a lower burden of noncardiac disease, which is another way saying "those who are less frail."

This conclusion underscores a statement in the 2012 American College of Cardiology/American Association for Thoracic Surgery/Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions/Society of Thoracic Surgeons expert consensus document on TAVR paraphrased by Dr. Alexander: Frailty will assume central importance in patient selection for TAVR by virtue of the extensive comorbidities in this population. Existing models do not have predictive variables of interest in high-risk patients. (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012;59:1200-54).

Dr. Alexander of Duke University in Durham, N.C., said frailty is important when considering TAVR because it has been shown to be associated with increased rates of post-TAVR 30-day morbidity and mortality, prolonged hospital length of stay, and 1-year mortality.

She defined frailty as a multisystem impairment resulting in reduced physiologic reserve and increased vulnerability to stress. Frailty is a physiologic phenotype associated with slow gait, weakness, weight loss, exhaustion, and a low daily activity level.

While the degree of a patient’s frailty is an important consideration in deciding on TAVR vs. medical management, frailty per se is no contraindication to the procedure. Indeed, the prevalence of frailty as defined simply by a baseline 5-meter walk time in excess of 6 seconds was 72% among the 7,710 TAVR patients, mean age 84 years, included in the recent first report of the comprehensive national STS/ACC Transcatheter Valve Therapy Registry (JAMA 2013;310:2069-77). That’s nearly twice the 38% prevalence among community-dwelling 85-year-olds, Dr. Alexander noted, citing data from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging (CMAJ 2011;183:e487-94).

More than 20 different frailty risk scores are now in circulation. Dr. Alexander is particularly enthusiastic about the frailty risk tool developed as part of the ACC’s new Championing Care for the Patient With Aortic Stenosis Initiative. It efficiently assesses five domains of frailty – slowness, weakness, malnutrition, inactivity with loss of independence, and malnutrition – and generates a clinically useful qualitative frailty rating. A patient with a high frailty score may not have sufficient life expectancy to obtain the benefits of TAVR.

With regard to treatment futility, Dr. Alexander observed that it can be defined as either lack of medical efficacy as judged by physicians or as lack of meaningful survival as judged by a patient’s personal values. Yet one in four Americans aged 75 years or older has given little or no thought to their own wishes for end-of-life medical therapy, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey.

The telephone survey, conducted last spring, included a representative sample of 1,994 U.S. adults. While 47% of respondents aged 75 years or older indicated they had given their own wishes for end-of-life medical care a great deal of thought, 25% said they had given the matter "not much or none." Reflection on those personal wishes needs to be part of the physician/patient discussion about TAVR, according to Dr. Alexander.

With regard to general views on end-of-life therapy, 74% of surveyed individuals age 75 and up declared there should be circumstances in which a patient should be allowed to die. Another 22% said medical staff should do everything possible to save a patient’s life under all circumstances.

Dr. Alexander reported serving as a consultant to Gilead and Pozen.

SNOWMASS, COLO.– Transcatheter aortic valve replacement in nonsurgical candidates with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis carries a hefty price tag of $116,500 per quality-adjusted life-year gained over medical management.

That’s the bottom line in a cost-effectiveness study led by cardiologist Dr. Mark A. Hlatky. The investigators applied data on the costs and benefits of transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) as documented in the landmark PARTNER (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves) trial in their Markov model involving a hypothetical patient cohort. The estimated incremental cost-effectiveness of $116,500 per quality-adjusted life-year gained is well in excess of the $50,000 figure widely accepted by health policy makers as defining a cutoff for cost-effective therapy.

In this cost-effectiveness analysis (Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2013;6:419-28), TAVR boosted life expectancy by roughly 11 months, from 2.08 years with medical therapy to 2.93 years. Quality-adjusted life expectancy rose from 1.19 to 1.93 years. TAVR also resulted in 1.4 fewer hospitalizations than with medical management. However, undergoing TAVR rather than medical management raised the lifetime stroke risk from 1% to 11% and increased lifetime health care costs from $83,600 to $169,100, reported the group led by Dr. Hlatky, professor of health research and policy and also professor of medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University.

"This is a fascinating study," Dr. Karen P. Alexander said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass. "I think the lesson here is that futility from a cost perspective is also something that should be in the discussion" regarding TAVR vs. medical therapy in patients with inoperable aortic stenosis.

She highlighted the Hlatky study in discussing the key role frailty assessment plays in considering TAVR. The study showed that the cost-effectiveness of TAVR is greater in patients with a lower burden of noncardiac disease, which is another way saying "those who are less frail."

This conclusion underscores a statement in the 2012 American College of Cardiology/American Association for Thoracic Surgery/Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions/Society of Thoracic Surgeons expert consensus document on TAVR paraphrased by Dr. Alexander: Frailty will assume central importance in patient selection for TAVR by virtue of the extensive comorbidities in this population. Existing models do not have predictive variables of interest in high-risk patients. (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012;59:1200-54).

Dr. Alexander of Duke University in Durham, N.C., said frailty is important when considering TAVR because it has been shown to be associated with increased rates of post-TAVR 30-day morbidity and mortality, prolonged hospital length of stay, and 1-year mortality.

She defined frailty as a multisystem impairment resulting in reduced physiologic reserve and increased vulnerability to stress. Frailty is a physiologic phenotype associated with slow gait, weakness, weight loss, exhaustion, and a low daily activity level.

While the degree of a patient’s frailty is an important consideration in deciding on TAVR vs. medical management, frailty per se is no contraindication to the procedure. Indeed, the prevalence of frailty as defined simply by a baseline 5-meter walk time in excess of 6 seconds was 72% among the 7,710 TAVR patients, mean age 84 years, included in the recent first report of the comprehensive national STS/ACC Transcatheter Valve Therapy Registry (JAMA 2013;310:2069-77). That’s nearly twice the 38% prevalence among community-dwelling 85-year-olds, Dr. Alexander noted, citing data from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging (CMAJ 2011;183:e487-94).

More than 20 different frailty risk scores are now in circulation. Dr. Alexander is particularly enthusiastic about the frailty risk tool developed as part of the ACC’s new Championing Care for the Patient With Aortic Stenosis Initiative. It efficiently assesses five domains of frailty – slowness, weakness, malnutrition, inactivity with loss of independence, and malnutrition – and generates a clinically useful qualitative frailty rating. A patient with a high frailty score may not have sufficient life expectancy to obtain the benefits of TAVR.

With regard to treatment futility, Dr. Alexander observed that it can be defined as either lack of medical efficacy as judged by physicians or as lack of meaningful survival as judged by a patient’s personal values. Yet one in four Americans aged 75 years or older has given little or no thought to their own wishes for end-of-life medical therapy, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey.

The telephone survey, conducted last spring, included a representative sample of 1,994 U.S. adults. While 47% of respondents aged 75 years or older indicated they had given their own wishes for end-of-life medical care a great deal of thought, 25% said they had given the matter "not much or none." Reflection on those personal wishes needs to be part of the physician/patient discussion about TAVR, according to Dr. Alexander.

With regard to general views on end-of-life therapy, 74% of surveyed individuals age 75 and up declared there should be circumstances in which a patient should be allowed to die. Another 22% said medical staff should do everything possible to save a patient’s life under all circumstances.

Dr. Alexander reported serving as a consultant to Gilead and Pozen.

New valve guideline promotes early surgery

The updated practice guideline for managing adults with valvular heart disease has a new, "modular" format to facilitate clinicians' access to "concise, relevant bytes of information at the point of care, when clinical knowledge is needed most," according to reports published online simultaneously March 3 in Circulation and the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The guideline, compiled by a committee of cardiologists, interventionalists, surgeons, and anesthesiologists under the aegis of the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology, was last updated in 2008.

"Some recommendations from the earlier valvular heart disease guideline have been updated as warranted by new evidence or a better understanding of earlier evidence, whereas others that were inaccurate, irrelevant, or overlapping were deleted or modified," said writing committee cochairs Dr. Rick A. Nishimura of the division of cardiovascular diseases, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.; and Dr. Catherine M. Otto, director of the University of Washington Medical Center's Heart Valve Clinic, Seattle.

The narrative text of the guideline is limited, and instead it uses decision pathway diagrams and numerous summary tables of current evidence and recommendations. These include links to relevant references. It is hoped that clinicians can more easily use the new guideline as a quick reference. This format also will enable individual sections to be updated or amended as new evidence comes to light. The PDF of the guideline is available for free.

"This novel approach to evidence-based guideline development will revolutionize the clinical impact of guideline recommendations, ensuring they are always current and allowing seamless integration with electronic medical record systems," Dr. Otto said in a press statement accompanying the reports.

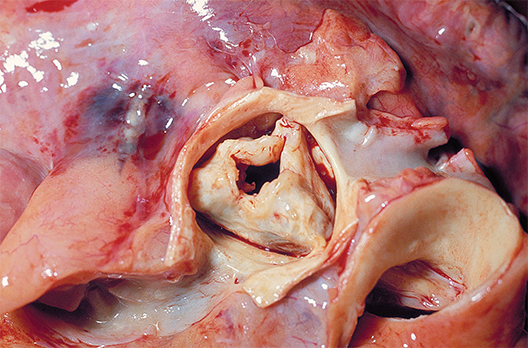

The guideline now includes gradations of disease severity, to help clinicians determine the optimal timing of intervention. Whether or not intervention is indicated depends on five factors: the presence or absence of symptoms, the severity of valvular heart disease, the response of the left and/or right ventricle to the volume or pressure overload caused by the valvular disease, the effect on the pulmonary or systemic circulation, and any change in heart rhythm.

Disease severity ranges from stage A, "at risk," which denotes patients who have risk factors for developing valvular heart disease; through stage B, "progressive," which indicates patients who are asymptomatic but have mildly to moderately severe disease; through stage C, "asymptomatic severe," which includes patients with severe yet still asymptomatic valvular disease in which the left or right ventricle remains compensated or in which the left or right ventricle has decompensated; to stage D, "symptomatic severe," which indicates patients whose severe valvular disease has produced symptoms.

"In patients with stenotic lesions, there is an additional category of 'very severe' stenosis based on studies of the natural history showing that prognosis becomes poorer as the severity of stenosis increases," the guideline states.

Information is provided for assessing the various disease states associated with the aortic, mitral, and tricuspid valves, and addresses the issues of valve repair, replacement, and the use of prosthetic valves.

Compared with the previous guideline, the new one suggests surgical intervention at an earlier stage for certain patients. "Due to more knowledge regarding the natural history of untreated patients with severe valvular heart disease and better outcomes from surgery, we've lowered the threshold for operation to include more patients with asymptomatic severe disease. Now, select patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis and severe asymptomatic mitral regurgitation can be considered for intervention, depending on certain other factors such as operative mortality and … the ability to achieve a durable valve repair," Dr. Nishimura said in the press statement.

The new guideline also proposes a new approach to risk assessment, to be applied to all patients for whom intervention is being considered. Previous risk scoring systems were "useful but limited"; the new approach takes into consideration "procedure-specific impediments, major organ system compromise, comorbidities, patient frailty, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons predicted risk of mortality model."

For the first time, the guideline discusses transcatheter aortic valve replacement and other catheter-based treatments, new technologies that have improved patient care but also have complicated risk assessment. Separate recommendations are now offered regarding the choice and the timing of these interventions.

In addition to the AHA and the ACC, this guideline was developed in collaboration with the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Society for Echocardiography, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

The complete 2014 Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease is available from the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association.

Dr. Nishimura and Dr. Otto reported no financial conflicts of interest; their associates on the ACC/AHA Task Force's writing committee reported ties to Edwards Scientific, Medtronic, and St. Jude Medical.

The updated practice guideline for managing adults with valvular heart disease has a new, "modular" format to facilitate clinicians' access to "concise, relevant bytes of information at the point of care, when clinical knowledge is needed most," according to reports published online simultaneously March 3 in Circulation and the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The guideline, compiled by a committee of cardiologists, interventionalists, surgeons, and anesthesiologists under the aegis of the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology, was last updated in 2008.

"Some recommendations from the earlier valvular heart disease guideline have been updated as warranted by new evidence or a better understanding of earlier evidence, whereas others that were inaccurate, irrelevant, or overlapping were deleted or modified," said writing committee cochairs Dr. Rick A. Nishimura of the division of cardiovascular diseases, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.; and Dr. Catherine M. Otto, director of the University of Washington Medical Center's Heart Valve Clinic, Seattle.

The narrative text of the guideline is limited, and instead it uses decision pathway diagrams and numerous summary tables of current evidence and recommendations. These include links to relevant references. It is hoped that clinicians can more easily use the new guideline as a quick reference. This format also will enable individual sections to be updated or amended as new evidence comes to light. The PDF of the guideline is available for free.

"This novel approach to evidence-based guideline development will revolutionize the clinical impact of guideline recommendations, ensuring they are always current and allowing seamless integration with electronic medical record systems," Dr. Otto said in a press statement accompanying the reports.

The guideline now includes gradations of disease severity, to help clinicians determine the optimal timing of intervention. Whether or not intervention is indicated depends on five factors: the presence or absence of symptoms, the severity of valvular heart disease, the response of the left and/or right ventricle to the volume or pressure overload caused by the valvular disease, the effect on the pulmonary or systemic circulation, and any change in heart rhythm.

Disease severity ranges from stage A, "at risk," which denotes patients who have risk factors for developing valvular heart disease; through stage B, "progressive," which indicates patients who are asymptomatic but have mildly to moderately severe disease; through stage C, "asymptomatic severe," which includes patients with severe yet still asymptomatic valvular disease in which the left or right ventricle remains compensated or in which the left or right ventricle has decompensated; to stage D, "symptomatic severe," which indicates patients whose severe valvular disease has produced symptoms.

"In patients with stenotic lesions, there is an additional category of 'very severe' stenosis based on studies of the natural history showing that prognosis becomes poorer as the severity of stenosis increases," the guideline states.

Information is provided for assessing the various disease states associated with the aortic, mitral, and tricuspid valves, and addresses the issues of valve repair, replacement, and the use of prosthetic valves.

Compared with the previous guideline, the new one suggests surgical intervention at an earlier stage for certain patients. "Due to more knowledge regarding the natural history of untreated patients with severe valvular heart disease and better outcomes from surgery, we've lowered the threshold for operation to include more patients with asymptomatic severe disease. Now, select patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis and severe asymptomatic mitral regurgitation can be considered for intervention, depending on certain other factors such as operative mortality and … the ability to achieve a durable valve repair," Dr. Nishimura said in the press statement.

The new guideline also proposes a new approach to risk assessment, to be applied to all patients for whom intervention is being considered. Previous risk scoring systems were "useful but limited"; the new approach takes into consideration "procedure-specific impediments, major organ system compromise, comorbidities, patient frailty, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons predicted risk of mortality model."

For the first time, the guideline discusses transcatheter aortic valve replacement and other catheter-based treatments, new technologies that have improved patient care but also have complicated risk assessment. Separate recommendations are now offered regarding the choice and the timing of these interventions.

In addition to the AHA and the ACC, this guideline was developed in collaboration with the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Society for Echocardiography, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

The complete 2014 Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease is available from the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association.

Dr. Nishimura and Dr. Otto reported no financial conflicts of interest; their associates on the ACC/AHA Task Force's writing committee reported ties to Edwards Scientific, Medtronic, and St. Jude Medical.

The updated practice guideline for managing adults with valvular heart disease has a new, "modular" format to facilitate clinicians' access to "concise, relevant bytes of information at the point of care, when clinical knowledge is needed most," according to reports published online simultaneously March 3 in Circulation and the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The guideline, compiled by a committee of cardiologists, interventionalists, surgeons, and anesthesiologists under the aegis of the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology, was last updated in 2008.

"Some recommendations from the earlier valvular heart disease guideline have been updated as warranted by new evidence or a better understanding of earlier evidence, whereas others that were inaccurate, irrelevant, or overlapping were deleted or modified," said writing committee cochairs Dr. Rick A. Nishimura of the division of cardiovascular diseases, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.; and Dr. Catherine M. Otto, director of the University of Washington Medical Center's Heart Valve Clinic, Seattle.

The narrative text of the guideline is limited, and instead it uses decision pathway diagrams and numerous summary tables of current evidence and recommendations. These include links to relevant references. It is hoped that clinicians can more easily use the new guideline as a quick reference. This format also will enable individual sections to be updated or amended as new evidence comes to light. The PDF of the guideline is available for free.

"This novel approach to evidence-based guideline development will revolutionize the clinical impact of guideline recommendations, ensuring they are always current and allowing seamless integration with electronic medical record systems," Dr. Otto said in a press statement accompanying the reports.

The guideline now includes gradations of disease severity, to help clinicians determine the optimal timing of intervention. Whether or not intervention is indicated depends on five factors: the presence or absence of symptoms, the severity of valvular heart disease, the response of the left and/or right ventricle to the volume or pressure overload caused by the valvular disease, the effect on the pulmonary or systemic circulation, and any change in heart rhythm.

Disease severity ranges from stage A, "at risk," which denotes patients who have risk factors for developing valvular heart disease; through stage B, "progressive," which indicates patients who are asymptomatic but have mildly to moderately severe disease; through stage C, "asymptomatic severe," which includes patients with severe yet still asymptomatic valvular disease in which the left or right ventricle remains compensated or in which the left or right ventricle has decompensated; to stage D, "symptomatic severe," which indicates patients whose severe valvular disease has produced symptoms.

"In patients with stenotic lesions, there is an additional category of 'very severe' stenosis based on studies of the natural history showing that prognosis becomes poorer as the severity of stenosis increases," the guideline states.

Information is provided for assessing the various disease states associated with the aortic, mitral, and tricuspid valves, and addresses the issues of valve repair, replacement, and the use of prosthetic valves.

Compared with the previous guideline, the new one suggests surgical intervention at an earlier stage for certain patients. "Due to more knowledge regarding the natural history of untreated patients with severe valvular heart disease and better outcomes from surgery, we've lowered the threshold for operation to include more patients with asymptomatic severe disease. Now, select patients with severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis and severe asymptomatic mitral regurgitation can be considered for intervention, depending on certain other factors such as operative mortality and … the ability to achieve a durable valve repair," Dr. Nishimura said in the press statement.

The new guideline also proposes a new approach to risk assessment, to be applied to all patients for whom intervention is being considered. Previous risk scoring systems were "useful but limited"; the new approach takes into consideration "procedure-specific impediments, major organ system compromise, comorbidities, patient frailty, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons predicted risk of mortality model."

For the first time, the guideline discusses transcatheter aortic valve replacement and other catheter-based treatments, new technologies that have improved patient care but also have complicated risk assessment. Separate recommendations are now offered regarding the choice and the timing of these interventions.

In addition to the AHA and the ACC, this guideline was developed in collaboration with the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Society for Echocardiography, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons.

The complete 2014 Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease is available from the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association.

Dr. Nishimura and Dr. Otto reported no financial conflicts of interest; their associates on the ACC/AHA Task Force's writing committee reported ties to Edwards Scientific, Medtronic, and St. Jude Medical.

Preoperative organ dysfunction worsens SAVR outcomes

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The presence of preoperative dysfunction in more than any one of four key organ systems profoundly reduces survival in patients undergoing surgical aortic valve replacement, a study showed.

"If you have two or more dysfunctional organ systems, you really need to think about what you’re doing for this patient. At 5 years, only about 40% of these patients are alive. It makes a lot of sense to me to say that if you have a patient with severe COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease] and renal dysfunction, that patient should probably never get a surgical valve," Dr. Vinod H. Thourani said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

In a retrospective analysis of a registry with prospectively entered data, 29% of 1,759 patients who underwent surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) with or without coronary artery bypass grafting at Emory University during 2002-2010 had preoperative dysfunction of one or more of four organ systems under scrutiny. Eighty-five patients had severe COPD, as defined by a forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) that was less than 50% of predicted, 140 had chronic renal failure, 149 had a prior stroke, and 241 had heart failure with a left ventricular ejection less than 35%.

Patients with chronic renal failure had far and away the worst 30-day and long-term outcomes. Half were dead within 3 years. The 7-year survival rate was just 11.7%.

The second-worst outcomes were seen in patients with severe COPD preoperatively. Their 7-year survival rate was 30.8%.

"Anyone with an FEV1 below about 40% becomes a higher-risk surgical candidate; think instead of TAVR [transcatheter aortic valve replacement],"advised Dr. Thourani of the division of cardiothoracic surgery at Emory University, Atlanta.

In contrast, outcomes in patients with either heart failure or prior stroke "were not that bad," he said, pointing to 7-year survival rates of 55.9% and 48.6%, respectively.

Ninety-five patients (5.4%) in this recently published study (Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2013;95:838-45) had more than one dysfunctional organ system prior to SAVR. Median survival in patients without dysfunction in any of the four organ systems was 8.2 years and counting. With one dysfunctional organ, it was still good at 7.2 years. However, with two dysfunctional organ systems, the median survival dropped precipitously to 4.1 years. With three dysfunctional organ systems, it was 5.9 years.

Dr. Thourin serves as a consultant to Edwards Lifesciences, Sorin, and St. Jude Medical.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The presence of preoperative dysfunction in more than any one of four key organ systems profoundly reduces survival in patients undergoing surgical aortic valve replacement, a study showed.

"If you have two or more dysfunctional organ systems, you really need to think about what you’re doing for this patient. At 5 years, only about 40% of these patients are alive. It makes a lot of sense to me to say that if you have a patient with severe COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease] and renal dysfunction, that patient should probably never get a surgical valve," Dr. Vinod H. Thourani said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

In a retrospective analysis of a registry with prospectively entered data, 29% of 1,759 patients who underwent surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) with or without coronary artery bypass grafting at Emory University during 2002-2010 had preoperative dysfunction of one or more of four organ systems under scrutiny. Eighty-five patients had severe COPD, as defined by a forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) that was less than 50% of predicted, 140 had chronic renal failure, 149 had a prior stroke, and 241 had heart failure with a left ventricular ejection less than 35%.

Patients with chronic renal failure had far and away the worst 30-day and long-term outcomes. Half were dead within 3 years. The 7-year survival rate was just 11.7%.

The second-worst outcomes were seen in patients with severe COPD preoperatively. Their 7-year survival rate was 30.8%.

"Anyone with an FEV1 below about 40% becomes a higher-risk surgical candidate; think instead of TAVR [transcatheter aortic valve replacement],"advised Dr. Thourani of the division of cardiothoracic surgery at Emory University, Atlanta.

In contrast, outcomes in patients with either heart failure or prior stroke "were not that bad," he said, pointing to 7-year survival rates of 55.9% and 48.6%, respectively.

Ninety-five patients (5.4%) in this recently published study (Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2013;95:838-45) had more than one dysfunctional organ system prior to SAVR. Median survival in patients without dysfunction in any of the four organ systems was 8.2 years and counting. With one dysfunctional organ, it was still good at 7.2 years. However, with two dysfunctional organ systems, the median survival dropped precipitously to 4.1 years. With three dysfunctional organ systems, it was 5.9 years.

Dr. Thourin serves as a consultant to Edwards Lifesciences, Sorin, and St. Jude Medical.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – The presence of preoperative dysfunction in more than any one of four key organ systems profoundly reduces survival in patients undergoing surgical aortic valve replacement, a study showed.

"If you have two or more dysfunctional organ systems, you really need to think about what you’re doing for this patient. At 5 years, only about 40% of these patients are alive. It makes a lot of sense to me to say that if you have a patient with severe COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease] and renal dysfunction, that patient should probably never get a surgical valve," Dr. Vinod H. Thourani said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

In a retrospective analysis of a registry with prospectively entered data, 29% of 1,759 patients who underwent surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) with or without coronary artery bypass grafting at Emory University during 2002-2010 had preoperative dysfunction of one or more of four organ systems under scrutiny. Eighty-five patients had severe COPD, as defined by a forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) that was less than 50% of predicted, 140 had chronic renal failure, 149 had a prior stroke, and 241 had heart failure with a left ventricular ejection less than 35%.

Patients with chronic renal failure had far and away the worst 30-day and long-term outcomes. Half were dead within 3 years. The 7-year survival rate was just 11.7%.

The second-worst outcomes were seen in patients with severe COPD preoperatively. Their 7-year survival rate was 30.8%.

"Anyone with an FEV1 below about 40% becomes a higher-risk surgical candidate; think instead of TAVR [transcatheter aortic valve replacement],"advised Dr. Thourani of the division of cardiothoracic surgery at Emory University, Atlanta.

In contrast, outcomes in patients with either heart failure or prior stroke "were not that bad," he said, pointing to 7-year survival rates of 55.9% and 48.6%, respectively.

Ninety-five patients (5.4%) in this recently published study (Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2013;95:838-45) had more than one dysfunctional organ system prior to SAVR. Median survival in patients without dysfunction in any of the four organ systems was 8.2 years and counting. With one dysfunctional organ, it was still good at 7.2 years. However, with two dysfunctional organ systems, the median survival dropped precipitously to 4.1 years. With three dysfunctional organ systems, it was 5.9 years.

Dr. Thourin serves as a consultant to Edwards Lifesciences, Sorin, and St. Jude Medical.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

CoreValve holds size advantage for U.S. TAVR

When the Food and Drug Administration in January granted marketing approval to a second transcatheter aortic valve replacement system for inoperable patients with aortic stenosis, the CoreValve marketed by Medtronic, the new valve conceded a greater than 2-year head start to the first system on the U.S. market, Sapien marketed by Edwards.

But cardiologists see that 2-year edge in familiarity eclipsed for at least some patients by two major advantages that CoreValve currently holds over Sapien: delivery via a significantly thinner sheath, and the option of larger-diameter valves that allow replacement in patients with a wider aortic annulus.

The CoreValve delivery sheath is 18 French, compared with a 22F or 24F size for the Sapien transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) with U.S. approval, and the Sapien valves come in diameters of 23 and 26 mm, compared with options of 23, 26, 29, and 31 mm for the CoreValve.