User login

AML candidate drug back in the pipeline

The Food and Drug Administration has given the biopharmaceutical company Cellectis permission to resume phase 1 trials of UCART123, a gene-edited T-cell investigational drug that targets CD123, as a potential treatment for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN), according to a press release from the company.

UCART123 is the first allogeneic, “off-the-shelf” gene-edited chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell product candidate that the FDA has approved for clinical trials. The agency had placed a clinical hold on phase 1 trials of the gene-edited CAR T-cell drug on Sept. 4, following a patient death in the BPDCN clinical study. In order to proceed with the trials, Cellectis agreed to several changes in the study protocols.

The changes include decreasing the dose of the UCART123 therapy to 6.25x104 cells/kg and lowering the dose of the lympho-depleting regimen of cyclophosphamide to 750 mg/m2 per day over 3 days with a maximum daily dose of 1.33 g. Additionally, there can be no uncontrolled infection after receipt of the lympho-depleting preconditioning regimen. Patients must be afebrile at the start of treatment, off all but a replacement dose of corticosteroids, and have no organ dysfunction. Plus, the next three patients treated in each study must be under age 65.

There’s also a condition that patient enrollments be staggered by at least 28 days.

The drug sponsor is working with investigators and each clinical site to obtain the Institutional Review Board’s approval of the revised protocols.

The hold followed the death of a 78-year-old man with relapsed/refractory BPDCN with 30% blasts in his bone marrow and cutaneous lesions. The first dose of UCART123 at 6.25x105 cells/kg was administered without complication, but at day 5 the patient began experiencing side effects, including cytokine release syndrome and a lung infection. At day 8, the cytokine release syndrome had worsened and the patient had also developed capillary leak syndrome. He died on day 9 of the study.

In the AML phase 1 study, a 58-year-old woman with AML and 84% blasts in her bone marrow received the same dose of UCART123. She also developed cytokine release syndrome and capillary leak syndrome but both resolved with treatment.

Both patients also received the same preconditioning treatment: 30 mg/m2 per day fludarabine for 4 days and 1g/m2 per day cyclophosphamide for 3 days.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

The Food and Drug Administration has given the biopharmaceutical company Cellectis permission to resume phase 1 trials of UCART123, a gene-edited T-cell investigational drug that targets CD123, as a potential treatment for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN), according to a press release from the company.

UCART123 is the first allogeneic, “off-the-shelf” gene-edited chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell product candidate that the FDA has approved for clinical trials. The agency had placed a clinical hold on phase 1 trials of the gene-edited CAR T-cell drug on Sept. 4, following a patient death in the BPDCN clinical study. In order to proceed with the trials, Cellectis agreed to several changes in the study protocols.

The changes include decreasing the dose of the UCART123 therapy to 6.25x104 cells/kg and lowering the dose of the lympho-depleting regimen of cyclophosphamide to 750 mg/m2 per day over 3 days with a maximum daily dose of 1.33 g. Additionally, there can be no uncontrolled infection after receipt of the lympho-depleting preconditioning regimen. Patients must be afebrile at the start of treatment, off all but a replacement dose of corticosteroids, and have no organ dysfunction. Plus, the next three patients treated in each study must be under age 65.

There’s also a condition that patient enrollments be staggered by at least 28 days.

The drug sponsor is working with investigators and each clinical site to obtain the Institutional Review Board’s approval of the revised protocols.

The hold followed the death of a 78-year-old man with relapsed/refractory BPDCN with 30% blasts in his bone marrow and cutaneous lesions. The first dose of UCART123 at 6.25x105 cells/kg was administered without complication, but at day 5 the patient began experiencing side effects, including cytokine release syndrome and a lung infection. At day 8, the cytokine release syndrome had worsened and the patient had also developed capillary leak syndrome. He died on day 9 of the study.

In the AML phase 1 study, a 58-year-old woman with AML and 84% blasts in her bone marrow received the same dose of UCART123. She also developed cytokine release syndrome and capillary leak syndrome but both resolved with treatment.

Both patients also received the same preconditioning treatment: 30 mg/m2 per day fludarabine for 4 days and 1g/m2 per day cyclophosphamide for 3 days.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

The Food and Drug Administration has given the biopharmaceutical company Cellectis permission to resume phase 1 trials of UCART123, a gene-edited T-cell investigational drug that targets CD123, as a potential treatment for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN), according to a press release from the company.

UCART123 is the first allogeneic, “off-the-shelf” gene-edited chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell product candidate that the FDA has approved for clinical trials. The agency had placed a clinical hold on phase 1 trials of the gene-edited CAR T-cell drug on Sept. 4, following a patient death in the BPDCN clinical study. In order to proceed with the trials, Cellectis agreed to several changes in the study protocols.

The changes include decreasing the dose of the UCART123 therapy to 6.25x104 cells/kg and lowering the dose of the lympho-depleting regimen of cyclophosphamide to 750 mg/m2 per day over 3 days with a maximum daily dose of 1.33 g. Additionally, there can be no uncontrolled infection after receipt of the lympho-depleting preconditioning regimen. Patients must be afebrile at the start of treatment, off all but a replacement dose of corticosteroids, and have no organ dysfunction. Plus, the next three patients treated in each study must be under age 65.

There’s also a condition that patient enrollments be staggered by at least 28 days.

The drug sponsor is working with investigators and each clinical site to obtain the Institutional Review Board’s approval of the revised protocols.

The hold followed the death of a 78-year-old man with relapsed/refractory BPDCN with 30% blasts in his bone marrow and cutaneous lesions. The first dose of UCART123 at 6.25x105 cells/kg was administered without complication, but at day 5 the patient began experiencing side effects, including cytokine release syndrome and a lung infection. At day 8, the cytokine release syndrome had worsened and the patient had also developed capillary leak syndrome. He died on day 9 of the study.

In the AML phase 1 study, a 58-year-old woman with AML and 84% blasts in her bone marrow received the same dose of UCART123. She also developed cytokine release syndrome and capillary leak syndrome but both resolved with treatment.

Both patients also received the same preconditioning treatment: 30 mg/m2 per day fludarabine for 4 days and 1g/m2 per day cyclophosphamide for 3 days.

[email protected]

On Twitter @maryellenny

EMA grants accelerated assessment to drug for AML

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use has granted accelerated assessment to a marketing authorization application (MAA) for CPX-351 (Vyxeos™), a fixed-ratio combination of cytarabine and daunorubicin inside a lipid vesicle.

The MAA is for CPX-351 to treat adults with high-risk acute myeloid leukemia (AML), defined as therapy-related AML or AML with myelodysplasia-related changes.

Accelerated assessment is designed to reduce the review timeline for products of major interest for public health and therapeutic innovation.

“If approved, Vyxeos will become the first new chemotherapy treatment option specifically for European patients with therapy-related AML or AML with myelodysplasia-related changes,” said Karen Smith, MD, PhD, executive vice president, research and development and chief medical officer at Jazz Pharmaceuticals, the company developing and marketing CPX-351.

The MAA for CPX-351 is supported by clinical data from 5 studies, including a phase 3 study. Results from this study were presented at the 2016 ASCO Annual Meeting.

In this study, researchers compared CPX-351 to cytarabine and daunorubicin (7+3) in 309 patients, ages 60 to 75, with newly diagnosed, therapy-related AML or AML with myelodysplasia-related changes.

The complete response rate was 38% in the CPX-351 arm and 26% in the 7+3 arm (P=0.036).

The rate of hematopoietic stem cell transplant was 34% in the CPX-351 arm and 25% in the 7+3 arm.

The median overall survival was 9.6 months in the CPX-351 arm and 5.9 months in the 7+3 arm (P=0.005).

All-cause 30-day mortality was 6% in the CPX-351 arm and 11% in the 7+3 arm. Sixty-day mortality was 14% and 21%, respectively.

Six percent of patients in both arms had a fatal adverse event (AE) on treatment or within 30 days of therapy that was not in the setting of progressive disease.

The rate of AEs that led to discontinuation was 18% in the CPX-351 arm and 13% in the 7+3 arm. AEs leading to discontinuation in the CPX-351 arm included prolonged cytopenias, infection, cardiotoxicity, respiratory failure, hemorrhage, renal insufficiency, colitis, and generalized medical deterioration.

The most common AEs (incidence ≥ 25%) in the CPX-351 arm were hemorrhagic events, febrile neutropenia, rash, edema, nausea, mucositis, diarrhea, constipation, musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, abdominal pain, dyspnea, headache, cough, decreased appetite, arrhythmia, pneumonia, bacteremia, chills, sleep disorders, and vomiting.

The most common serious AEs (incidence ≥ 5%) in the CPX-351 arm were dyspnea, myocardial toxicity, sepsis, pneumonia, febrile neutropenia, bacteremia, and hemorrhage. ![]()

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use has granted accelerated assessment to a marketing authorization application (MAA) for CPX-351 (Vyxeos™), a fixed-ratio combination of cytarabine and daunorubicin inside a lipid vesicle.

The MAA is for CPX-351 to treat adults with high-risk acute myeloid leukemia (AML), defined as therapy-related AML or AML with myelodysplasia-related changes.

Accelerated assessment is designed to reduce the review timeline for products of major interest for public health and therapeutic innovation.

“If approved, Vyxeos will become the first new chemotherapy treatment option specifically for European patients with therapy-related AML or AML with myelodysplasia-related changes,” said Karen Smith, MD, PhD, executive vice president, research and development and chief medical officer at Jazz Pharmaceuticals, the company developing and marketing CPX-351.

The MAA for CPX-351 is supported by clinical data from 5 studies, including a phase 3 study. Results from this study were presented at the 2016 ASCO Annual Meeting.

In this study, researchers compared CPX-351 to cytarabine and daunorubicin (7+3) in 309 patients, ages 60 to 75, with newly diagnosed, therapy-related AML or AML with myelodysplasia-related changes.

The complete response rate was 38% in the CPX-351 arm and 26% in the 7+3 arm (P=0.036).

The rate of hematopoietic stem cell transplant was 34% in the CPX-351 arm and 25% in the 7+3 arm.

The median overall survival was 9.6 months in the CPX-351 arm and 5.9 months in the 7+3 arm (P=0.005).

All-cause 30-day mortality was 6% in the CPX-351 arm and 11% in the 7+3 arm. Sixty-day mortality was 14% and 21%, respectively.

Six percent of patients in both arms had a fatal adverse event (AE) on treatment or within 30 days of therapy that was not in the setting of progressive disease.

The rate of AEs that led to discontinuation was 18% in the CPX-351 arm and 13% in the 7+3 arm. AEs leading to discontinuation in the CPX-351 arm included prolonged cytopenias, infection, cardiotoxicity, respiratory failure, hemorrhage, renal insufficiency, colitis, and generalized medical deterioration.

The most common AEs (incidence ≥ 25%) in the CPX-351 arm were hemorrhagic events, febrile neutropenia, rash, edema, nausea, mucositis, diarrhea, constipation, musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, abdominal pain, dyspnea, headache, cough, decreased appetite, arrhythmia, pneumonia, bacteremia, chills, sleep disorders, and vomiting.

The most common serious AEs (incidence ≥ 5%) in the CPX-351 arm were dyspnea, myocardial toxicity, sepsis, pneumonia, febrile neutropenia, bacteremia, and hemorrhage. ![]()

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use has granted accelerated assessment to a marketing authorization application (MAA) for CPX-351 (Vyxeos™), a fixed-ratio combination of cytarabine and daunorubicin inside a lipid vesicle.

The MAA is for CPX-351 to treat adults with high-risk acute myeloid leukemia (AML), defined as therapy-related AML or AML with myelodysplasia-related changes.

Accelerated assessment is designed to reduce the review timeline for products of major interest for public health and therapeutic innovation.

“If approved, Vyxeos will become the first new chemotherapy treatment option specifically for European patients with therapy-related AML or AML with myelodysplasia-related changes,” said Karen Smith, MD, PhD, executive vice president, research and development and chief medical officer at Jazz Pharmaceuticals, the company developing and marketing CPX-351.

The MAA for CPX-351 is supported by clinical data from 5 studies, including a phase 3 study. Results from this study were presented at the 2016 ASCO Annual Meeting.

In this study, researchers compared CPX-351 to cytarabine and daunorubicin (7+3) in 309 patients, ages 60 to 75, with newly diagnosed, therapy-related AML or AML with myelodysplasia-related changes.

The complete response rate was 38% in the CPX-351 arm and 26% in the 7+3 arm (P=0.036).

The rate of hematopoietic stem cell transplant was 34% in the CPX-351 arm and 25% in the 7+3 arm.

The median overall survival was 9.6 months in the CPX-351 arm and 5.9 months in the 7+3 arm (P=0.005).

All-cause 30-day mortality was 6% in the CPX-351 arm and 11% in the 7+3 arm. Sixty-day mortality was 14% and 21%, respectively.

Six percent of patients in both arms had a fatal adverse event (AE) on treatment or within 30 days of therapy that was not in the setting of progressive disease.

The rate of AEs that led to discontinuation was 18% in the CPX-351 arm and 13% in the 7+3 arm. AEs leading to discontinuation in the CPX-351 arm included prolonged cytopenias, infection, cardiotoxicity, respiratory failure, hemorrhage, renal insufficiency, colitis, and generalized medical deterioration.

The most common AEs (incidence ≥ 25%) in the CPX-351 arm were hemorrhagic events, febrile neutropenia, rash, edema, nausea, mucositis, diarrhea, constipation, musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, abdominal pain, dyspnea, headache, cough, decreased appetite, arrhythmia, pneumonia, bacteremia, chills, sleep disorders, and vomiting.

The most common serious AEs (incidence ≥ 5%) in the CPX-351 arm were dyspnea, myocardial toxicity, sepsis, pneumonia, febrile neutropenia, bacteremia, and hemorrhage. ![]()

FDA lifts hold on trials of universal CAR T-cell therapy

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has lifted the full clinical hold on 2 phase 1 studies of UCART123, an allogeneic chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy targeting CD123.

One of these studies was designed for patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and the other was designed for patients with blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN).

The hold meant no new subjects could be enrolled in either trial, and there could be no further dosing of subjects who were already enrolled.

The hold was placed in September because the first patient treated in the BPDCN trial died. The patient developed grade 2 cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and a grade 3 lung infection. This was followed by grade 4 capillary leak syndrome and grade 5 CRS.

The first patient treated in the AML trial also developed grade 4 capillary leak syndrome and grade 3 CRS, but both resolved.

Now, the FDA has lifted the hold on the trials because Cellectis, the company developing UCART123, agreed to implement the following main revisions to phase 1 UCART123 protocols:

- Decrease the cohort dose level to 6.25 x 104 UCART123 cells/kg

- Decrease the cyclophosphamide dose of the lymphodepleting regimen to 750 mg/m²/day over 3 days, with a maximum daily dose of 1.33 grams

- Include specific criteria at Day 0, the day of UCART123 infusion, such as no new uncontrolled infection after receipt of lymphodepletion, afebrile, off all but replacement dose of corticosteroids, and no organ dysfunction since eligibility screening

- Ensure the next 3 patients to be treated in each protocol will be under the age of 65

- Ensure that enrollment will be staggered across the UCART123 protocols; at least 28 days should elapse between the enrollments of 2 patients across the 2 studies.

Cellectis is currently working with investigators and clinical sites to obtain internal review board approval on the revised protocols and resume patient enrollment. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has lifted the full clinical hold on 2 phase 1 studies of UCART123, an allogeneic chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy targeting CD123.

One of these studies was designed for patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and the other was designed for patients with blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN).

The hold meant no new subjects could be enrolled in either trial, and there could be no further dosing of subjects who were already enrolled.

The hold was placed in September because the first patient treated in the BPDCN trial died. The patient developed grade 2 cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and a grade 3 lung infection. This was followed by grade 4 capillary leak syndrome and grade 5 CRS.

The first patient treated in the AML trial also developed grade 4 capillary leak syndrome and grade 3 CRS, but both resolved.

Now, the FDA has lifted the hold on the trials because Cellectis, the company developing UCART123, agreed to implement the following main revisions to phase 1 UCART123 protocols:

- Decrease the cohort dose level to 6.25 x 104 UCART123 cells/kg

- Decrease the cyclophosphamide dose of the lymphodepleting regimen to 750 mg/m²/day over 3 days, with a maximum daily dose of 1.33 grams

- Include specific criteria at Day 0, the day of UCART123 infusion, such as no new uncontrolled infection after receipt of lymphodepletion, afebrile, off all but replacement dose of corticosteroids, and no organ dysfunction since eligibility screening

- Ensure the next 3 patients to be treated in each protocol will be under the age of 65

- Ensure that enrollment will be staggered across the UCART123 protocols; at least 28 days should elapse between the enrollments of 2 patients across the 2 studies.

Cellectis is currently working with investigators and clinical sites to obtain internal review board approval on the revised protocols and resume patient enrollment. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has lifted the full clinical hold on 2 phase 1 studies of UCART123, an allogeneic chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy targeting CD123.

One of these studies was designed for patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and the other was designed for patients with blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN).

The hold meant no new subjects could be enrolled in either trial, and there could be no further dosing of subjects who were already enrolled.

The hold was placed in September because the first patient treated in the BPDCN trial died. The patient developed grade 2 cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and a grade 3 lung infection. This was followed by grade 4 capillary leak syndrome and grade 5 CRS.

The first patient treated in the AML trial also developed grade 4 capillary leak syndrome and grade 3 CRS, but both resolved.

Now, the FDA has lifted the hold on the trials because Cellectis, the company developing UCART123, agreed to implement the following main revisions to phase 1 UCART123 protocols:

- Decrease the cohort dose level to 6.25 x 104 UCART123 cells/kg

- Decrease the cyclophosphamide dose of the lymphodepleting regimen to 750 mg/m²/day over 3 days, with a maximum daily dose of 1.33 grams

- Include specific criteria at Day 0, the day of UCART123 infusion, such as no new uncontrolled infection after receipt of lymphodepletion, afebrile, off all but replacement dose of corticosteroids, and no organ dysfunction since eligibility screening

- Ensure the next 3 patients to be treated in each protocol will be under the age of 65

- Ensure that enrollment will be staggered across the UCART123 protocols; at least 28 days should elapse between the enrollments of 2 patients across the 2 studies.

Cellectis is currently working with investigators and clinical sites to obtain internal review board approval on the revised protocols and resume patient enrollment. ![]()

Cancer drug costs increasing despite competition

Cancer drug costs in the US increase substantially after launch, regardless of competition, according to a study published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.*

Researchers studied 24 cancer drugs approved over the last 20 years and found a mean cumulative cost increase of about 37%, or 19% when adjusted for inflation.

Among drugs approved to treat hematologic malignancies, the greatest inflation-adjusted price increases were for arsenic trioxide (57%), nelarabine (55%), and rituximab (49%).

The lowest inflation-adjusted price increases were for ofatumumab (8%), clofarabine (8%), and liposomal vincristine (18%).

For this study, Daniel A. Goldstein, MD, of Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, and his colleagues measured the monthly price trajectories of 24 cancer drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. This included 10 drugs approved to treat hematologic malignancies between 1997 and 2011.

To account for discounts and rebates, the researchers used the average sales prices published by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and adjusted to general and health-related inflation rates. For each drug, the researchers calculated the cumulative and annual drug cost changes.

Results

The mean follow-up was 8 years. The mean cumulative cost increase for all 24 drugs was +36.5% (95% CI, 24.7% to 48.3%).

The general inflation-adjusted increase was +19.1% (95% CI, 11.0% to 27.2%), and the health-related inflation-adjusted increase was +8.4% (95% CI, 1.4% to 15.4%).

Only 1 of the 24 drugs studied had a price decrease over time. That drug is ziv-aflibercept, which was approved to treat metastatic colorectal cancer in 2012.

Ziv-aflibercept was launched with an annual price exceeding $110,000. After public outcry, the drug’s manufacturer, Sanofi, cut the price in half. By the end of the study’s follow-up period in 2017, the cost of ziv-aflibercept had decreased 13% (inflation-adjusted decrease of 15%, health-related inflation-adjusted decrease of 20%).

Cost changes for the drugs approved to treat hematologic malignancies are listed in the following table.

| Drug (indication, approval date, years of follow-up) | Mean monthly cost at launch | Mean annual cost change (SD) | Cumulative cost change | General and health-related inflation-adjusted change, respectively |

| Arsenic trioxide (APL, 2000, 12) | $11,455 | +6% (4) | +95% | +57%, +39% |

| Bendamustine (CLL, NHL, 2008, 8) | $6924 | +5% (5) | +50% | +32%, +21% |

| Bortezomib (MM, MCL, 2003, 12) | $5490 | +4% (3) | +63% | +31%, +16% |

| Brentuximab (lymphoma, 2011, 4) | $19,482 | +8% (0.1) | +35% | +29%, +22% |

| Clofarabine (ALL, 2004, 11) | $56,486 | +3% (3) | +31% | +8%, -4% |

| Liposomal vincristine (ALL, 2012, 3) | $34,602 | +8% (0.5) | +21% | +18%, +14% |

| Nelarabine (ALL, lymphoma, 2005, 10) | $18,513 | +6% (2) | +83% | +55%, +39% |

| Ofatumumab (CLL, 2009, 6) | $4538 | +3% (2) | +17% | +8%, -0.5% |

| Pralatrexate (lymphoma, 2009, 6) | $31,684 | +6% (4) | +43% | +31%, +21% |

| Rituximab (NHL, CLL, 1997, 12) | $4111 | +5% (0.5) | +85% | +49%, +32% |

Abbreviations: ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; APL, acute promyelocytic leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; MM, multiple myeloma; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; SD, standard deviation.

The researchers noted that there was a steady increase in drug costs over the study period, regardless of whether a drug was granted a new supplemental indication, the drug had a new off-label indication, or a competitor drug was approved.

The only variable that was significantly associated with price change was the amount of time that had elapsed from a drug’s launch.

This association was significant in models in which the researchers used prices adjusted to inflation (P=0.002) and health-related inflation (P=0.023). However, it was not significant when the researchers used the actual drug price (P=0.085). ![]()

*Data in the abstract differ from data in the body of the JCO paper. This article includes data from the body of the JCO paper.

Cancer drug costs in the US increase substantially after launch, regardless of competition, according to a study published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.*

Researchers studied 24 cancer drugs approved over the last 20 years and found a mean cumulative cost increase of about 37%, or 19% when adjusted for inflation.

Among drugs approved to treat hematologic malignancies, the greatest inflation-adjusted price increases were for arsenic trioxide (57%), nelarabine (55%), and rituximab (49%).

The lowest inflation-adjusted price increases were for ofatumumab (8%), clofarabine (8%), and liposomal vincristine (18%).

For this study, Daniel A. Goldstein, MD, of Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, and his colleagues measured the monthly price trajectories of 24 cancer drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. This included 10 drugs approved to treat hematologic malignancies between 1997 and 2011.

To account for discounts and rebates, the researchers used the average sales prices published by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and adjusted to general and health-related inflation rates. For each drug, the researchers calculated the cumulative and annual drug cost changes.

Results

The mean follow-up was 8 years. The mean cumulative cost increase for all 24 drugs was +36.5% (95% CI, 24.7% to 48.3%).

The general inflation-adjusted increase was +19.1% (95% CI, 11.0% to 27.2%), and the health-related inflation-adjusted increase was +8.4% (95% CI, 1.4% to 15.4%).

Only 1 of the 24 drugs studied had a price decrease over time. That drug is ziv-aflibercept, which was approved to treat metastatic colorectal cancer in 2012.

Ziv-aflibercept was launched with an annual price exceeding $110,000. After public outcry, the drug’s manufacturer, Sanofi, cut the price in half. By the end of the study’s follow-up period in 2017, the cost of ziv-aflibercept had decreased 13% (inflation-adjusted decrease of 15%, health-related inflation-adjusted decrease of 20%).

Cost changes for the drugs approved to treat hematologic malignancies are listed in the following table.

| Drug (indication, approval date, years of follow-up) | Mean monthly cost at launch | Mean annual cost change (SD) | Cumulative cost change | General and health-related inflation-adjusted change, respectively |

| Arsenic trioxide (APL, 2000, 12) | $11,455 | +6% (4) | +95% | +57%, +39% |

| Bendamustine (CLL, NHL, 2008, 8) | $6924 | +5% (5) | +50% | +32%, +21% |

| Bortezomib (MM, MCL, 2003, 12) | $5490 | +4% (3) | +63% | +31%, +16% |

| Brentuximab (lymphoma, 2011, 4) | $19,482 | +8% (0.1) | +35% | +29%, +22% |

| Clofarabine (ALL, 2004, 11) | $56,486 | +3% (3) | +31% | +8%, -4% |

| Liposomal vincristine (ALL, 2012, 3) | $34,602 | +8% (0.5) | +21% | +18%, +14% |

| Nelarabine (ALL, lymphoma, 2005, 10) | $18,513 | +6% (2) | +83% | +55%, +39% |

| Ofatumumab (CLL, 2009, 6) | $4538 | +3% (2) | +17% | +8%, -0.5% |

| Pralatrexate (lymphoma, 2009, 6) | $31,684 | +6% (4) | +43% | +31%, +21% |

| Rituximab (NHL, CLL, 1997, 12) | $4111 | +5% (0.5) | +85% | +49%, +32% |

Abbreviations: ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; APL, acute promyelocytic leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; MM, multiple myeloma; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; SD, standard deviation.

The researchers noted that there was a steady increase in drug costs over the study period, regardless of whether a drug was granted a new supplemental indication, the drug had a new off-label indication, or a competitor drug was approved.

The only variable that was significantly associated with price change was the amount of time that had elapsed from a drug’s launch.

This association was significant in models in which the researchers used prices adjusted to inflation (P=0.002) and health-related inflation (P=0.023). However, it was not significant when the researchers used the actual drug price (P=0.085). ![]()

*Data in the abstract differ from data in the body of the JCO paper. This article includes data from the body of the JCO paper.

Cancer drug costs in the US increase substantially after launch, regardless of competition, according to a study published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.*

Researchers studied 24 cancer drugs approved over the last 20 years and found a mean cumulative cost increase of about 37%, or 19% when adjusted for inflation.

Among drugs approved to treat hematologic malignancies, the greatest inflation-adjusted price increases were for arsenic trioxide (57%), nelarabine (55%), and rituximab (49%).

The lowest inflation-adjusted price increases were for ofatumumab (8%), clofarabine (8%), and liposomal vincristine (18%).

For this study, Daniel A. Goldstein, MD, of Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, and his colleagues measured the monthly price trajectories of 24 cancer drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. This included 10 drugs approved to treat hematologic malignancies between 1997 and 2011.

To account for discounts and rebates, the researchers used the average sales prices published by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and adjusted to general and health-related inflation rates. For each drug, the researchers calculated the cumulative and annual drug cost changes.

Results

The mean follow-up was 8 years. The mean cumulative cost increase for all 24 drugs was +36.5% (95% CI, 24.7% to 48.3%).

The general inflation-adjusted increase was +19.1% (95% CI, 11.0% to 27.2%), and the health-related inflation-adjusted increase was +8.4% (95% CI, 1.4% to 15.4%).

Only 1 of the 24 drugs studied had a price decrease over time. That drug is ziv-aflibercept, which was approved to treat metastatic colorectal cancer in 2012.

Ziv-aflibercept was launched with an annual price exceeding $110,000. After public outcry, the drug’s manufacturer, Sanofi, cut the price in half. By the end of the study’s follow-up period in 2017, the cost of ziv-aflibercept had decreased 13% (inflation-adjusted decrease of 15%, health-related inflation-adjusted decrease of 20%).

Cost changes for the drugs approved to treat hematologic malignancies are listed in the following table.

| Drug (indication, approval date, years of follow-up) | Mean monthly cost at launch | Mean annual cost change (SD) | Cumulative cost change | General and health-related inflation-adjusted change, respectively |

| Arsenic trioxide (APL, 2000, 12) | $11,455 | +6% (4) | +95% | +57%, +39% |

| Bendamustine (CLL, NHL, 2008, 8) | $6924 | +5% (5) | +50% | +32%, +21% |

| Bortezomib (MM, MCL, 2003, 12) | $5490 | +4% (3) | +63% | +31%, +16% |

| Brentuximab (lymphoma, 2011, 4) | $19,482 | +8% (0.1) | +35% | +29%, +22% |

| Clofarabine (ALL, 2004, 11) | $56,486 | +3% (3) | +31% | +8%, -4% |

| Liposomal vincristine (ALL, 2012, 3) | $34,602 | +8% (0.5) | +21% | +18%, +14% |

| Nelarabine (ALL, lymphoma, 2005, 10) | $18,513 | +6% (2) | +83% | +55%, +39% |

| Ofatumumab (CLL, 2009, 6) | $4538 | +3% (2) | +17% | +8%, -0.5% |

| Pralatrexate (lymphoma, 2009, 6) | $31,684 | +6% (4) | +43% | +31%, +21% |

| Rituximab (NHL, CLL, 1997, 12) | $4111 | +5% (0.5) | +85% | +49%, +32% |

Abbreviations: ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; APL, acute promyelocytic leukemia; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; MM, multiple myeloma; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; SD, standard deviation.

The researchers noted that there was a steady increase in drug costs over the study period, regardless of whether a drug was granted a new supplemental indication, the drug had a new off-label indication, or a competitor drug was approved.

The only variable that was significantly associated with price change was the amount of time that had elapsed from a drug’s launch.

This association was significant in models in which the researchers used prices adjusted to inflation (P=0.002) and health-related inflation (P=0.023). However, it was not significant when the researchers used the actual drug price (P=0.085). ![]()

*Data in the abstract differ from data in the body of the JCO paper. This article includes data from the body of the JCO paper.

Adequately nourished AML patients have survival advantage

Good nutritional status can extend the lives of patients with acute myeloid leukemia going into induction chemotherapy, according to a retrospective study of 95 adult AML patients.

Those with good nutritional status had significantly shorter hospital stays than did undernourished patients. Furthermore, they had greater 12-month survival, compared with undernourished patients.

“Assessment of nutritional status is essential because undernutrition in this population is common,” Elise Deluche, MD, and her coinvestigators wrote (Nutrition. 2017 Sep;41:120-5). They assessed the nutritional status of 95 consecutive adult AML patients admitted to Limoges (France) University Hospital during 2009-2014 and followed their nutritional status for 12 months.Patients were considered undernourished if they had lost more than 5% of their weight, and had a body mass index (BMI) of under 18.5 kg/m2 if less than 70 years of age, or under 21 kg/m2 if aged at least 70 years.

Fourteen patients (15%) were undernourished at admission. That proportion grew after chemotherapy induction to 17 patients (18%), but there were no significant differences from admission in BMI, weight, or albumin.

The adequately nourished patients had significantly worse nutritional status at discharge than admission, with a significantly lower median weight (P =.02), BMI (P = .04), and albumin levels (P = .0002), compared with their admission values.

Importantly, the well nourished patients had shorter hospital stays than their undernourished counterparts, at 31 days, compared with 39 days (P = .03). Furthermore, their 12-month survival was greater, at 89.9%, than that of the undernourished patient, at 58.3% (P = .002).

After chemotherapy induction, 64 patients (67%) were in complete remission: 57 (70%) in the adequately nourished and 7 (50%) in the undernourished group, a nonsignificant difference.

This is the first study to look solely at patients with AML, Dr. DeLuche and her coinvestigators said, as previous nutritional studies have also included patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and it “confirmed that the length of hospitalization was shorter for patients without undernutrition.” They added that their study included a more accurate representation of AML patients with a median patient age of 58 years, much older than the range of 28-41 found in other studies. A quarter of the patients in Dr. DeLuche’s study were over age 65.

“[Existing] screening tools should be improved and adapted to the specific situation of induction chemotherapy for monitoring nutritional status during hospitalization,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding, and the investigators had no conflicts of interest.

Good nutritional status can extend the lives of patients with acute myeloid leukemia going into induction chemotherapy, according to a retrospective study of 95 adult AML patients.

Those with good nutritional status had significantly shorter hospital stays than did undernourished patients. Furthermore, they had greater 12-month survival, compared with undernourished patients.

“Assessment of nutritional status is essential because undernutrition in this population is common,” Elise Deluche, MD, and her coinvestigators wrote (Nutrition. 2017 Sep;41:120-5). They assessed the nutritional status of 95 consecutive adult AML patients admitted to Limoges (France) University Hospital during 2009-2014 and followed their nutritional status for 12 months.Patients were considered undernourished if they had lost more than 5% of their weight, and had a body mass index (BMI) of under 18.5 kg/m2 if less than 70 years of age, or under 21 kg/m2 if aged at least 70 years.

Fourteen patients (15%) were undernourished at admission. That proportion grew after chemotherapy induction to 17 patients (18%), but there were no significant differences from admission in BMI, weight, or albumin.

The adequately nourished patients had significantly worse nutritional status at discharge than admission, with a significantly lower median weight (P =.02), BMI (P = .04), and albumin levels (P = .0002), compared with their admission values.

Importantly, the well nourished patients had shorter hospital stays than their undernourished counterparts, at 31 days, compared with 39 days (P = .03). Furthermore, their 12-month survival was greater, at 89.9%, than that of the undernourished patient, at 58.3% (P = .002).

After chemotherapy induction, 64 patients (67%) were in complete remission: 57 (70%) in the adequately nourished and 7 (50%) in the undernourished group, a nonsignificant difference.

This is the first study to look solely at patients with AML, Dr. DeLuche and her coinvestigators said, as previous nutritional studies have also included patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and it “confirmed that the length of hospitalization was shorter for patients without undernutrition.” They added that their study included a more accurate representation of AML patients with a median patient age of 58 years, much older than the range of 28-41 found in other studies. A quarter of the patients in Dr. DeLuche’s study were over age 65.

“[Existing] screening tools should be improved and adapted to the specific situation of induction chemotherapy for monitoring nutritional status during hospitalization,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding, and the investigators had no conflicts of interest.

Good nutritional status can extend the lives of patients with acute myeloid leukemia going into induction chemotherapy, according to a retrospective study of 95 adult AML patients.

Those with good nutritional status had significantly shorter hospital stays than did undernourished patients. Furthermore, they had greater 12-month survival, compared with undernourished patients.

“Assessment of nutritional status is essential because undernutrition in this population is common,” Elise Deluche, MD, and her coinvestigators wrote (Nutrition. 2017 Sep;41:120-5). They assessed the nutritional status of 95 consecutive adult AML patients admitted to Limoges (France) University Hospital during 2009-2014 and followed their nutritional status for 12 months.Patients were considered undernourished if they had lost more than 5% of their weight, and had a body mass index (BMI) of under 18.5 kg/m2 if less than 70 years of age, or under 21 kg/m2 if aged at least 70 years.

Fourteen patients (15%) were undernourished at admission. That proportion grew after chemotherapy induction to 17 patients (18%), but there were no significant differences from admission in BMI, weight, or albumin.

The adequately nourished patients had significantly worse nutritional status at discharge than admission, with a significantly lower median weight (P =.02), BMI (P = .04), and albumin levels (P = .0002), compared with their admission values.

Importantly, the well nourished patients had shorter hospital stays than their undernourished counterparts, at 31 days, compared with 39 days (P = .03). Furthermore, their 12-month survival was greater, at 89.9%, than that of the undernourished patient, at 58.3% (P = .002).

After chemotherapy induction, 64 patients (67%) were in complete remission: 57 (70%) in the adequately nourished and 7 (50%) in the undernourished group, a nonsignificant difference.

This is the first study to look solely at patients with AML, Dr. DeLuche and her coinvestigators said, as previous nutritional studies have also included patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and it “confirmed that the length of hospitalization was shorter for patients without undernutrition.” They added that their study included a more accurate representation of AML patients with a median patient age of 58 years, much older than the range of 28-41 found in other studies. A quarter of the patients in Dr. DeLuche’s study were over age 65.

“[Existing] screening tools should be improved and adapted to the specific situation of induction chemotherapy for monitoring nutritional status during hospitalization,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding, and the investigators had no conflicts of interest.

FROM NUTRITION

Key clinical point:

Major finding: AML patients who were adequately nourished going into induction chemotherapy had significantly shorter hospital stays (31 days versus 39 days) and greater 12-month survival than did those who were undernourished (89.9% versus 58.3%).

Data source: A study of 95 consecutive AML patients admitted to a single center and assessed for nutritional status before and after induction chemotherapy.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding, and the investigators had no conflicts of interest.

Study reveals misperceptions among AML patients

SAN DIEGO—A study of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients has revealed misperceptions about treatment risks and the likelihood of cure.

Investigators surveyed 100 AML patients receiving intensive and non-intensive chemotherapy, as well as the patients’ oncologists.

The results showed that patients tended to overestimate both the risk of dying due to treatment and the likelihood of cure.

These findings were presented at the 2017 Palliative and Supportive Care in Oncology Symposium (abstract 43).

“Patients with AML face very challenging treatment decisions that are often placed upon them within days after being diagnosed,” said study investigator Areej El-Jawahri, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

“Because they face a grave decision, they need to understand what the risks of treatment are versus the possibility of a cure.”

For this study, Dr El-Jawahri and her colleagues enrolled 50 patients who were receiving intensive care for AML (which usually meant hospitalization for 4 to 6 weeks) and 50 patients who were receiving non-intensive care (often given as outpatient treatment).

The patients’ median age was 71 (range, 60-100), and 92% were white. Six percent of patients had low-risk disease, 48% had intermediate-risk, and 46% had high-risk disease.

Within 3 days of starting treatment, both the patients and their physicians were given a questionnaire to assess how they perceived the likelihood of the patient dying from treatment.

One month later, patients and physicians completed a follow-up questionnaire to assess perceptions of patient prognosis. Within that time frame, most patients received laboratory results that more definitively established the type and stage of cancer.

At 24 weeks, the investigators asked patients if they had discussed their end-of-life wishes with their oncologists.

Results

Initially, most of the patient population (91.3%) thought it was “somewhat” or “extremely” likely they would die from their treatment. However, only 22% of treating oncologists said the same.

One month later, a majority of patients in both treatment groups thought it was “somewhat” or “extremely” likely they would be cured of their AML.

Specifically, 82.1% of patients receiving non-intensive chemotherapy said it was “somewhat” or “extremely” likely they would be cured, while 10% of their oncologists said the same.

Meanwhile, 97.6% of patients receiving intensive chemotherapy said it was “somewhat” or “extremely” likely they would be cured, and 42% of their oncologists said the same.

Overall, 77.8% of patients said they had not discussed their end-of-life wishes with their oncologists at 24 weeks.

“There were several very important factors we were not able to capture in our study, including what was actually discussed between patients and their oncologists and whether patients simply misunderstood or misheard the information conveyed to them,” Dr El-Jawahri said.

“Perhaps most importantly, we did not audio-record the discussions between the patients and their physicians, which could provide additional details regarding barriers to accurate prognostic understanding in these conversations.”

Related research and next steps

Prior to this study, Dr El-Jawahri and her colleagues had looked at similar perceptions in patients with solid tumor malignancies as well as in patients with hematologic malignancies who were receiving hematopoietic stem cell transplants.

The gaps in perception of treatment risk and cure for patients compared to their physicians were not as large in those cases as in the AML patients in this study. The investigators attribute this to higher levels of distress seen in AML patients due to the urgency of their treatment decisions.

Dr El-Jawahri and her colleagues have found that early consideration of palliative care in a treatment plan for patients with solid tumors improves patients’ understanding of the prognosis. The team hopes to implement a similar study in patients with AML.

“Clearly, there are important communication gaps between oncologists and their patients,” Dr El-Jawahri said. “We need to find ways to help physicians do a better job of communicating with their patients, especially in diseases like AML where stress levels are remarkably high.” ![]()

SAN DIEGO—A study of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients has revealed misperceptions about treatment risks and the likelihood of cure.

Investigators surveyed 100 AML patients receiving intensive and non-intensive chemotherapy, as well as the patients’ oncologists.

The results showed that patients tended to overestimate both the risk of dying due to treatment and the likelihood of cure.

These findings were presented at the 2017 Palliative and Supportive Care in Oncology Symposium (abstract 43).

“Patients with AML face very challenging treatment decisions that are often placed upon them within days after being diagnosed,” said study investigator Areej El-Jawahri, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

“Because they face a grave decision, they need to understand what the risks of treatment are versus the possibility of a cure.”

For this study, Dr El-Jawahri and her colleagues enrolled 50 patients who were receiving intensive care for AML (which usually meant hospitalization for 4 to 6 weeks) and 50 patients who were receiving non-intensive care (often given as outpatient treatment).

The patients’ median age was 71 (range, 60-100), and 92% were white. Six percent of patients had low-risk disease, 48% had intermediate-risk, and 46% had high-risk disease.

Within 3 days of starting treatment, both the patients and their physicians were given a questionnaire to assess how they perceived the likelihood of the patient dying from treatment.

One month later, patients and physicians completed a follow-up questionnaire to assess perceptions of patient prognosis. Within that time frame, most patients received laboratory results that more definitively established the type and stage of cancer.

At 24 weeks, the investigators asked patients if they had discussed their end-of-life wishes with their oncologists.

Results

Initially, most of the patient population (91.3%) thought it was “somewhat” or “extremely” likely they would die from their treatment. However, only 22% of treating oncologists said the same.

One month later, a majority of patients in both treatment groups thought it was “somewhat” or “extremely” likely they would be cured of their AML.

Specifically, 82.1% of patients receiving non-intensive chemotherapy said it was “somewhat” or “extremely” likely they would be cured, while 10% of their oncologists said the same.

Meanwhile, 97.6% of patients receiving intensive chemotherapy said it was “somewhat” or “extremely” likely they would be cured, and 42% of their oncologists said the same.

Overall, 77.8% of patients said they had not discussed their end-of-life wishes with their oncologists at 24 weeks.

“There were several very important factors we were not able to capture in our study, including what was actually discussed between patients and their oncologists and whether patients simply misunderstood or misheard the information conveyed to them,” Dr El-Jawahri said.

“Perhaps most importantly, we did not audio-record the discussions between the patients and their physicians, which could provide additional details regarding barriers to accurate prognostic understanding in these conversations.”

Related research and next steps

Prior to this study, Dr El-Jawahri and her colleagues had looked at similar perceptions in patients with solid tumor malignancies as well as in patients with hematologic malignancies who were receiving hematopoietic stem cell transplants.

The gaps in perception of treatment risk and cure for patients compared to their physicians were not as large in those cases as in the AML patients in this study. The investigators attribute this to higher levels of distress seen in AML patients due to the urgency of their treatment decisions.

Dr El-Jawahri and her colleagues have found that early consideration of palliative care in a treatment plan for patients with solid tumors improves patients’ understanding of the prognosis. The team hopes to implement a similar study in patients with AML.

“Clearly, there are important communication gaps between oncologists and their patients,” Dr El-Jawahri said. “We need to find ways to help physicians do a better job of communicating with their patients, especially in diseases like AML where stress levels are remarkably high.” ![]()

SAN DIEGO—A study of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients has revealed misperceptions about treatment risks and the likelihood of cure.

Investigators surveyed 100 AML patients receiving intensive and non-intensive chemotherapy, as well as the patients’ oncologists.

The results showed that patients tended to overestimate both the risk of dying due to treatment and the likelihood of cure.

These findings were presented at the 2017 Palliative and Supportive Care in Oncology Symposium (abstract 43).

“Patients with AML face very challenging treatment decisions that are often placed upon them within days after being diagnosed,” said study investigator Areej El-Jawahri, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

“Because they face a grave decision, they need to understand what the risks of treatment are versus the possibility of a cure.”

For this study, Dr El-Jawahri and her colleagues enrolled 50 patients who were receiving intensive care for AML (which usually meant hospitalization for 4 to 6 weeks) and 50 patients who were receiving non-intensive care (often given as outpatient treatment).

The patients’ median age was 71 (range, 60-100), and 92% were white. Six percent of patients had low-risk disease, 48% had intermediate-risk, and 46% had high-risk disease.

Within 3 days of starting treatment, both the patients and their physicians were given a questionnaire to assess how they perceived the likelihood of the patient dying from treatment.

One month later, patients and physicians completed a follow-up questionnaire to assess perceptions of patient prognosis. Within that time frame, most patients received laboratory results that more definitively established the type and stage of cancer.

At 24 weeks, the investigators asked patients if they had discussed their end-of-life wishes with their oncologists.

Results

Initially, most of the patient population (91.3%) thought it was “somewhat” or “extremely” likely they would die from their treatment. However, only 22% of treating oncologists said the same.

One month later, a majority of patients in both treatment groups thought it was “somewhat” or “extremely” likely they would be cured of their AML.

Specifically, 82.1% of patients receiving non-intensive chemotherapy said it was “somewhat” or “extremely” likely they would be cured, while 10% of their oncologists said the same.

Meanwhile, 97.6% of patients receiving intensive chemotherapy said it was “somewhat” or “extremely” likely they would be cured, and 42% of their oncologists said the same.

Overall, 77.8% of patients said they had not discussed their end-of-life wishes with their oncologists at 24 weeks.

“There were several very important factors we were not able to capture in our study, including what was actually discussed between patients and their oncologists and whether patients simply misunderstood or misheard the information conveyed to them,” Dr El-Jawahri said.

“Perhaps most importantly, we did not audio-record the discussions between the patients and their physicians, which could provide additional details regarding barriers to accurate prognostic understanding in these conversations.”

Related research and next steps

Prior to this study, Dr El-Jawahri and her colleagues had looked at similar perceptions in patients with solid tumor malignancies as well as in patients with hematologic malignancies who were receiving hematopoietic stem cell transplants.

The gaps in perception of treatment risk and cure for patients compared to their physicians were not as large in those cases as in the AML patients in this study. The investigators attribute this to higher levels of distress seen in AML patients due to the urgency of their treatment decisions.

Dr El-Jawahri and her colleagues have found that early consideration of palliative care in a treatment plan for patients with solid tumors improves patients’ understanding of the prognosis. The team hopes to implement a similar study in patients with AML.

“Clearly, there are important communication gaps between oncologists and their patients,” Dr El-Jawahri said. “We need to find ways to help physicians do a better job of communicating with their patients, especially in diseases like AML where stress levels are remarkably high.” ![]()

Targeting key pathways to eradicate AML

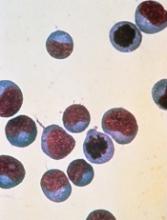

Targeting two pathways simultaneously—one critical for oncogenesis and one essential for cell survival—may be an effective strategy for treating acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to researchers.

The team studied mouse models of FLT3-ITD AML and found an inhibitor targeting the FLT3 pathway was largely effective against the disease.

However, targeting the BCL-2 pathway as well proved even more effective, completely eliminating AML in most cases.

Fumihiko Ishikawa, MD, PhD, of RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences in Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan, and his colleagues described this work in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers noted that mutations observed in AML patients have also been observed in elderly people without AML. So the team set out to determine which mutations actually contribute to the disease.

The researchers obtained bone marrow or blood samples from patients with FLT3-ITD AML and transplanted different cellular populations from each individual into mice. The team then examined how the cells behaved.

They were surprised to find that cells with similar surface marker profiles behaved differently. Therefore, the team used single-cell genomic sequencing to correlate mutational profiles with malignant potential.

The researchers said their results suggest that FLT3-ITD is “a critical trigger for leukemia initiation,” and it cooperates with accumulated mutations in DNMT3A, TET2, NPM1, and/or WT1.

The team went on to treat the FLT3-ITD AML mice with RK-20449, a FLT3/HCK inhibitor, and they observed “significant responses.”

In fact, RK-20449 eradicated leukemia originating from 5 different patients. The recipient mice experienced complete elimination of AML cells, in spite of the fact that they also carried mutations not directly targeted by RK-20449.

However, the researchers also noted the presence of RK-20449-resistant AML cells in some mice. The team therefore theorized that co-inhibition of an antiapoptotic signal—BCL-2—might remedy this.

So they treated resistant mice with the BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax as well as RK-20449. The combination produced responses in all mice treated and completely eliminated AML cells in 9 of 12 cases.

“This shows that determining which of the mutations in a diverse landscape are critical in leukemia onset and which of the pathways are critical for therapeutic resistance in leukemia, and simultaneously targeting those pathways, is an encouraging way to treat difficult cancers such as AML,” Dr Ishikawa said. ![]()

Targeting two pathways simultaneously—one critical for oncogenesis and one essential for cell survival—may be an effective strategy for treating acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to researchers.

The team studied mouse models of FLT3-ITD AML and found an inhibitor targeting the FLT3 pathway was largely effective against the disease.

However, targeting the BCL-2 pathway as well proved even more effective, completely eliminating AML in most cases.

Fumihiko Ishikawa, MD, PhD, of RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences in Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan, and his colleagues described this work in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers noted that mutations observed in AML patients have also been observed in elderly people without AML. So the team set out to determine which mutations actually contribute to the disease.

The researchers obtained bone marrow or blood samples from patients with FLT3-ITD AML and transplanted different cellular populations from each individual into mice. The team then examined how the cells behaved.

They were surprised to find that cells with similar surface marker profiles behaved differently. Therefore, the team used single-cell genomic sequencing to correlate mutational profiles with malignant potential.

The researchers said their results suggest that FLT3-ITD is “a critical trigger for leukemia initiation,” and it cooperates with accumulated mutations in DNMT3A, TET2, NPM1, and/or WT1.

The team went on to treat the FLT3-ITD AML mice with RK-20449, a FLT3/HCK inhibitor, and they observed “significant responses.”

In fact, RK-20449 eradicated leukemia originating from 5 different patients. The recipient mice experienced complete elimination of AML cells, in spite of the fact that they also carried mutations not directly targeted by RK-20449.

However, the researchers also noted the presence of RK-20449-resistant AML cells in some mice. The team therefore theorized that co-inhibition of an antiapoptotic signal—BCL-2—might remedy this.

So they treated resistant mice with the BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax as well as RK-20449. The combination produced responses in all mice treated and completely eliminated AML cells in 9 of 12 cases.

“This shows that determining which of the mutations in a diverse landscape are critical in leukemia onset and which of the pathways are critical for therapeutic resistance in leukemia, and simultaneously targeting those pathways, is an encouraging way to treat difficult cancers such as AML,” Dr Ishikawa said. ![]()

Targeting two pathways simultaneously—one critical for oncogenesis and one essential for cell survival—may be an effective strategy for treating acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to researchers.

The team studied mouse models of FLT3-ITD AML and found an inhibitor targeting the FLT3 pathway was largely effective against the disease.

However, targeting the BCL-2 pathway as well proved even more effective, completely eliminating AML in most cases.

Fumihiko Ishikawa, MD, PhD, of RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences in Yokohama, Kanagawa, Japan, and his colleagues described this work in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers noted that mutations observed in AML patients have also been observed in elderly people without AML. So the team set out to determine which mutations actually contribute to the disease.

The researchers obtained bone marrow or blood samples from patients with FLT3-ITD AML and transplanted different cellular populations from each individual into mice. The team then examined how the cells behaved.

They were surprised to find that cells with similar surface marker profiles behaved differently. Therefore, the team used single-cell genomic sequencing to correlate mutational profiles with malignant potential.

The researchers said their results suggest that FLT3-ITD is “a critical trigger for leukemia initiation,” and it cooperates with accumulated mutations in DNMT3A, TET2, NPM1, and/or WT1.

The team went on to treat the FLT3-ITD AML mice with RK-20449, a FLT3/HCK inhibitor, and they observed “significant responses.”

In fact, RK-20449 eradicated leukemia originating from 5 different patients. The recipient mice experienced complete elimination of AML cells, in spite of the fact that they also carried mutations not directly targeted by RK-20449.

However, the researchers also noted the presence of RK-20449-resistant AML cells in some mice. The team therefore theorized that co-inhibition of an antiapoptotic signal—BCL-2—might remedy this.

So they treated resistant mice with the BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax as well as RK-20449. The combination produced responses in all mice treated and completely eliminated AML cells in 9 of 12 cases.

“This shows that determining which of the mutations in a diverse landscape are critical in leukemia onset and which of the pathways are critical for therapeutic resistance in leukemia, and simultaneously targeting those pathways, is an encouraging way to treat difficult cancers such as AML,” Dr Ishikawa said. ![]()

‘Year of AML’ just the beginning, expert says

SAN FRANCISCO – After years of stagnation in the field of acute myeloid leukemia – with most standard therapies developed in the 1970s – times are changing, Bruno Medeiros, MD, said at the annual congress on hematologic malignancies held by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

“2017 is the year of AML,” he said. Four new therapies have been approved by the FDA since April. They include midostaurin for newly diagnosed, FLT-3–mutated patients; enasidenib, for relapsed/refractory IDH2-mutated patients; CPX-351, for high-risk AML patients; and gemtuzumab ozogamicin for newly diagnosed, CD-33–positive patients.

“Development of novel therapies in order to improve the outcomes of these patients is crucial,” said Dr. Medeiros, director of the inpatient hematology service at Stanford (Calif.) Cancer Institute. “I think all of us in the community hope that this is just the tip of the iceberg – this is just the beginning.”

The field is still struggling to negotiate the newly broadened landscape of AML treatment, he said. For instance, it’s not known exactly which patients are likely to respond to isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) inhibitors, he said.

He did offer some guidance on the use of CPX-351, a new formulation of the chemotherapeutic agents cytarabine and daunorubicin that is active in chemotherapy-resistant patients and could be a useful tool leading up to transplant.

“It appears that this drug is able to actually get patients into remission more effectively, leads to fewer toxicities and then allows patients to get to transplant in better shape with better disease response, translating into better overall outcomes,” Dr. Medeiros said.

Many more drugs are in development, with results likely to be revealed soon. Approval for a novel IDH1 inhibitor – only the IDH2 inhibitor is currently approved – is expected early next year. Also under investigation are the hypomethylating agents guadecitabine, a formulation that protects decitabine from degradation, and oral azacitidine, which might be beneficial particularly to patients not eligible for allogeneic stem cell transplant; the B-cell lymphoma 2–inhibitor venetoclax; and an E-selectin antagonist that targets an adhesion molecule in AML cells.

Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy – so promising in other areas of hematologic treatment – is complicated in AML, he said, because of the lack of a target that doesn’t bring on unwanted effects.

“The expression of any antigen in leukemic stem cells is also shared by the expression in hematopoietic stem cells and therefore the use of agents that will target these particular antigens consequently leads to an ‘on-target, off-leukemia’ side effect associated with myeloid cell aplasia.”

Dr. Medeiros reports financial relationships with Celgene, Jazz, Novartis, Pfizer, and other companies.

SAN FRANCISCO – After years of stagnation in the field of acute myeloid leukemia – with most standard therapies developed in the 1970s – times are changing, Bruno Medeiros, MD, said at the annual congress on hematologic malignancies held by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

“2017 is the year of AML,” he said. Four new therapies have been approved by the FDA since April. They include midostaurin for newly diagnosed, FLT-3–mutated patients; enasidenib, for relapsed/refractory IDH2-mutated patients; CPX-351, for high-risk AML patients; and gemtuzumab ozogamicin for newly diagnosed, CD-33–positive patients.

“Development of novel therapies in order to improve the outcomes of these patients is crucial,” said Dr. Medeiros, director of the inpatient hematology service at Stanford (Calif.) Cancer Institute. “I think all of us in the community hope that this is just the tip of the iceberg – this is just the beginning.”

The field is still struggling to negotiate the newly broadened landscape of AML treatment, he said. For instance, it’s not known exactly which patients are likely to respond to isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) inhibitors, he said.

He did offer some guidance on the use of CPX-351, a new formulation of the chemotherapeutic agents cytarabine and daunorubicin that is active in chemotherapy-resistant patients and could be a useful tool leading up to transplant.

“It appears that this drug is able to actually get patients into remission more effectively, leads to fewer toxicities and then allows patients to get to transplant in better shape with better disease response, translating into better overall outcomes,” Dr. Medeiros said.

Many more drugs are in development, with results likely to be revealed soon. Approval for a novel IDH1 inhibitor – only the IDH2 inhibitor is currently approved – is expected early next year. Also under investigation are the hypomethylating agents guadecitabine, a formulation that protects decitabine from degradation, and oral azacitidine, which might be beneficial particularly to patients not eligible for allogeneic stem cell transplant; the B-cell lymphoma 2–inhibitor venetoclax; and an E-selectin antagonist that targets an adhesion molecule in AML cells.

Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy – so promising in other areas of hematologic treatment – is complicated in AML, he said, because of the lack of a target that doesn’t bring on unwanted effects.

“The expression of any antigen in leukemic stem cells is also shared by the expression in hematopoietic stem cells and therefore the use of agents that will target these particular antigens consequently leads to an ‘on-target, off-leukemia’ side effect associated with myeloid cell aplasia.”

Dr. Medeiros reports financial relationships with Celgene, Jazz, Novartis, Pfizer, and other companies.

SAN FRANCISCO – After years of stagnation in the field of acute myeloid leukemia – with most standard therapies developed in the 1970s – times are changing, Bruno Medeiros, MD, said at the annual congress on hematologic malignancies held by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

“2017 is the year of AML,” he said. Four new therapies have been approved by the FDA since April. They include midostaurin for newly diagnosed, FLT-3–mutated patients; enasidenib, for relapsed/refractory IDH2-mutated patients; CPX-351, for high-risk AML patients; and gemtuzumab ozogamicin for newly diagnosed, CD-33–positive patients.

“Development of novel therapies in order to improve the outcomes of these patients is crucial,” said Dr. Medeiros, director of the inpatient hematology service at Stanford (Calif.) Cancer Institute. “I think all of us in the community hope that this is just the tip of the iceberg – this is just the beginning.”

The field is still struggling to negotiate the newly broadened landscape of AML treatment, he said. For instance, it’s not known exactly which patients are likely to respond to isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) inhibitors, he said.

He did offer some guidance on the use of CPX-351, a new formulation of the chemotherapeutic agents cytarabine and daunorubicin that is active in chemotherapy-resistant patients and could be a useful tool leading up to transplant.

“It appears that this drug is able to actually get patients into remission more effectively, leads to fewer toxicities and then allows patients to get to transplant in better shape with better disease response, translating into better overall outcomes,” Dr. Medeiros said.

Many more drugs are in development, with results likely to be revealed soon. Approval for a novel IDH1 inhibitor – only the IDH2 inhibitor is currently approved – is expected early next year. Also under investigation are the hypomethylating agents guadecitabine, a formulation that protects decitabine from degradation, and oral azacitidine, which might be beneficial particularly to patients not eligible for allogeneic stem cell transplant; the B-cell lymphoma 2–inhibitor venetoclax; and an E-selectin antagonist that targets an adhesion molecule in AML cells.

Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy – so promising in other areas of hematologic treatment – is complicated in AML, he said, because of the lack of a target that doesn’t bring on unwanted effects.

“The expression of any antigen in leukemic stem cells is also shared by the expression in hematopoietic stem cells and therefore the use of agents that will target these particular antigens consequently leads to an ‘on-target, off-leukemia’ side effect associated with myeloid cell aplasia.”

Dr. Medeiros reports financial relationships with Celgene, Jazz, Novartis, Pfizer, and other companies.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE NCCN HEMATOLOGIC MALIGNANCIES CONGRESS

ATLG fights GVHD but reduces PFS, OS

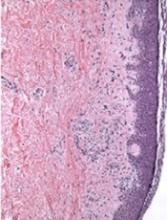

Results of a phase 3 trial suggest rabbit anti-T lymphocyte globulin (ATLG) can reduce graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) but also decrease survival in patients who have received a hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) from a matched, unrelated donor.

In this randomized trial, ATLG significantly decreased the incidence of moderate-to-severe chronic GVHD and acute grade 2-4 GVHD, when compared to placebo.

However, patients who received ATLG also had significantly lower progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) than placebo-treated patients.

On the other hand, the data also suggest that patients who receive conditioning regimens that do not lower absolute lymphocyte counts (ALCs) substantially may not experience a significant decrease in survival with ATLG.

These results were published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. The study was sponsored by Neovii Pharmaceuticals AG, which is developing ATLG as Grafalon®.

The study was a prospective, randomized, double-blind trial conducted in North America and Australia (NCT01295710). It enrolled 254 patients, ages 18 to 65, who had acute lymphoblastic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, or myelodysplastic syndromes. All patients were undergoing myeloablative, HLA-matched, unrelated HSCT.

Patients were randomized in a 1:1 fashion to receive ATLG (given at 20 mg/kg/day, n=126) or placebo (250 ml of normal saline, n=128) on days -3, -2, and -1 prior to HSCT.

In addition, all patients received antihistamine and methylprednisolone (at 2 mg/kg on day -3 and 1 mg/kg on days -2 and -1).

Patients also received GVHD prophylaxis in the form of tacrolimus (with a target serum trough level of 5 to 15 ng/mL) and methotrexate (15 mg/m2 on day 1, then 10 mg/m2 on days 3, 6, and 11). If patients did not develop clinical GVHD, tacrolimus was tapered starting on day 50 or later over a minimum of 26 weeks and ultimately discontinued.

Patients received 1 of 3 conditioning regimens, which were declared prior to randomization and included:

- Cyclophosphamide at 120 mg/kg intravenously (IV) and fractionated total body irradiation (TBI, ≥12 Gy)

- Busulfan at 16 mg/kg orally or 12.8 mg/kg IV and cyclophosphamide at 120 mg/kg IV

- Busulfan at 16 mg/kg orally or 12.8 mg/kg IV and fludarabine at 120 mg/m2 IV.

Overall results

Compared to placebo-treated patients, those who received ATLG had a significant reduction in grade 2-4 acute GVHD—23% and 40%, respectively (P=0.004)—and moderate-to-severe chronic GVHD—12% and 33%, respectively (P<0.001).

However, there was no significant difference between the ATLG and placebo arms with regard to moderate-severe chronic GVHD-free survival. The 2-year estimate was 48% and 44%, respectively (P=0.47).

In addition, PFS and OS were significantly lower in patients who received ATLG. The estimated 2-year PFS was 47% in the ATLG arm and 65% in the placebo arm (P=0.04). The estimated 2-year OS was 59% and 74%, respectively (P=0.034).

In a multivariable analysis, ATLG remained significantly associated with inferior PFS (hazard ratio [HR]=1.55, P=0.026) and OS (hazard ratio=1.74, P=0.01).

Role of conditioning, ALC

The researchers found evidence to suggest that conditioning regimen and ALC played a role in patient outcomes.

For patients who received cyclophosphamide and TBI, 2-year moderate-severe chronic GVHD-free survival was 61% in the placebo arm and 38% in the ATLG arm (P=0.080). Two-year OS was 88% and 48%, respectively (P=0.006). And 2-year PFS was 75% and 29%, respectively (P=0.007).

For patients who received busulfan and cyclophosphamide, 2-year moderate-severe chronic GVHD-free survival was 47% in the placebo arm and 53% in the ATLG arm (P=0.650). Two-year OS was 77% and 71%, respectively (P=0.350). And 2-year PFS was 73% and 60%, respectively (P=0.460).

For patients who received busulfan and fludarabine, 2-year moderate-severe chronic GVHD-free survival was 33% in the placebo arm and 49% in the ATLG arm (P=0.047). Two-year OS was 66% and 53%, respectively (P=0.520). And 2-year PFS was 58% and 48%, respectively (P=0.540).

The researchers noted that the choice of conditioning regimen had a “profound effect” on ALC at day -3 (the time of ATLG/placebo initiation). More than 70% of patients who received TBI had an ALC <0.1 x 109/L, compared to less than 35% of patients who received busulfan-based conditioning.

ALC, in turn, had an impact on PFS and OS. In patients with an ALC ≥ 0.1 x 109/L on day -3, ATLG did not compromise PFS or OS, but PFS and OS were negatively affected in patients with an ALC < 0.1.

ATLG recipients with an ALC < 0.1 had significantly worse OS (HR=4.13, P<0.001) and PFS (HR=3.19, P<0.001) than patients with an ALC ≥ 0.1. ![]()

Results of a phase 3 trial suggest rabbit anti-T lymphocyte globulin (ATLG) can reduce graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) but also decrease survival in patients who have received a hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) from a matched, unrelated donor.

In this randomized trial, ATLG significantly decreased the incidence of moderate-to-severe chronic GVHD and acute grade 2-4 GVHD, when compared to placebo.

However, patients who received ATLG also had significantly lower progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) than placebo-treated patients.

On the other hand, the data also suggest that patients who receive conditioning regimens that do not lower absolute lymphocyte counts (ALCs) substantially may not experience a significant decrease in survival with ATLG.

These results were published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. The study was sponsored by Neovii Pharmaceuticals AG, which is developing ATLG as Grafalon®.

The study was a prospective, randomized, double-blind trial conducted in North America and Australia (NCT01295710). It enrolled 254 patients, ages 18 to 65, who had acute lymphoblastic leukemia, acute myeloid leukemia, or myelodysplastic syndromes. All patients were undergoing myeloablative, HLA-matched, unrelated HSCT.

Patients were randomized in a 1:1 fashion to receive ATLG (given at 20 mg/kg/day, n=126) or placebo (250 ml of normal saline, n=128) on days -3, -2, and -1 prior to HSCT.

In addition, all patients received antihistamine and methylprednisolone (at 2 mg/kg on day -3 and 1 mg/kg on days -2 and -1).