User login

Study could change treatment of MLSM7

New findings could help improve treatment of an inherited bone marrow disorder known as myelodysplasia and leukemia syndrome with monosomy 7 (MLSM7), according to researchers.

While studying families affected by MLSM7, researchers identified germline mutations in SAMD9L or SAMD9 in patients who had hematologic abnormalities, myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), or acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

However, these mutations were also present in apparently healthy family members, and the researchers found that bone marrow monosomy 7 sometimes resolved without treatment.

The team recounted these findings in JCI Insight.

The researchers analyzed blood samples from 16 siblings in 5 families affected by MLSM7 and found they all carried germline mutations in SAMD9 or SAMD9L. In 3 of the 5 families, there were apparently healthy parents who also carried the mutations.

“Surprisingly, the health consequences of these mutations varied tremendously for reasons that must still be determined, but the findings are already affecting how we may choose to manage these patients,” said study author Jeffery Klco, MD, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee.

Three of the 16 siblings developed AML and died of the disease or related complications. Two other siblings were diagnosed with MDS.

The remaining 11 siblings with the mutations were apparently healthy, although several had been treated for anemia and other conditions associated with low blood counts.

Some of these patients had a previous history of bone marrow monosomy 7 that spontaneously corrected over time. These patients, despite no therapy, appeared to have normal bone marrow function.

“This was an even greater surprise,” Dr Klco said. “The spontaneous recovery experienced by some children with the germline mutations suggests some patients with SAMD9 and SAMD9L mutations who were previously considered candidates for bone marrow transplantation may recover hematologic function on their own.”

Dr Klco and his colleagues have a theory that could explain the spontaneous correction. The team noted that SAMD9 and SAMD9L are activated in response to viral infections. While the normal function of both proteins is poorly understood, abnormally activated SAMD9 and SAMD9L are known to inhibit cell growth.

In this study, deep sequencing showed that selective pressure on developing blood cells favors cells without the SAMD9 or SAMD9L mutations. That may increase pressure for cells to selectively jettison chromosome 7 with the gene alteration or take other molecular measures to counteract the mutant protein.

Implications for treatment

This research also showed that, in patients who developed AML, loss of chromosome 7 was associated with the development of mutations in additional genes, including ETV6, KRAS, SETBP1, and RUNX1.

These same mutations are broadly associated with monosomy 7 in AML, which suggests that understanding how SAMD9 and SAMD9L mutations contribute to leukemia has implications beyond familial cases.

The presence of secondary mutations may also help clinicians identify which patients will benefit from immediate treatment, including chemotherapy or transplant to prevent or treat AML or myelodysplasia, Dr Klco said.

For patients without the mutations or significant symptoms due to low blood cell counts, watchful waiting with careful follow-up may sometimes be an option.

“Now that we know this disease can resolve without treatment in some patients, we need to focus on developing screening and treatment guidelines,” Dr Klco said. “We want to reserve hematopoietic bone marrow transplantation for those who truly need the procedure. These findings will help to point the way.”

“So little is known about SAMD9 and SAMD9L that we need to continue working in the lab to better understand how these mutations impact blood cell development and how they are activated in response to infections and other types of stress.”

New findings could help improve treatment of an inherited bone marrow disorder known as myelodysplasia and leukemia syndrome with monosomy 7 (MLSM7), according to researchers.

While studying families affected by MLSM7, researchers identified germline mutations in SAMD9L or SAMD9 in patients who had hematologic abnormalities, myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), or acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

However, these mutations were also present in apparently healthy family members, and the researchers found that bone marrow monosomy 7 sometimes resolved without treatment.

The team recounted these findings in JCI Insight.

The researchers analyzed blood samples from 16 siblings in 5 families affected by MLSM7 and found they all carried germline mutations in SAMD9 or SAMD9L. In 3 of the 5 families, there were apparently healthy parents who also carried the mutations.

“Surprisingly, the health consequences of these mutations varied tremendously for reasons that must still be determined, but the findings are already affecting how we may choose to manage these patients,” said study author Jeffery Klco, MD, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee.

Three of the 16 siblings developed AML and died of the disease or related complications. Two other siblings were diagnosed with MDS.

The remaining 11 siblings with the mutations were apparently healthy, although several had been treated for anemia and other conditions associated with low blood counts.

Some of these patients had a previous history of bone marrow monosomy 7 that spontaneously corrected over time. These patients, despite no therapy, appeared to have normal bone marrow function.

“This was an even greater surprise,” Dr Klco said. “The spontaneous recovery experienced by some children with the germline mutations suggests some patients with SAMD9 and SAMD9L mutations who were previously considered candidates for bone marrow transplantation may recover hematologic function on their own.”

Dr Klco and his colleagues have a theory that could explain the spontaneous correction. The team noted that SAMD9 and SAMD9L are activated in response to viral infections. While the normal function of both proteins is poorly understood, abnormally activated SAMD9 and SAMD9L are known to inhibit cell growth.

In this study, deep sequencing showed that selective pressure on developing blood cells favors cells without the SAMD9 or SAMD9L mutations. That may increase pressure for cells to selectively jettison chromosome 7 with the gene alteration or take other molecular measures to counteract the mutant protein.

Implications for treatment

This research also showed that, in patients who developed AML, loss of chromosome 7 was associated with the development of mutations in additional genes, including ETV6, KRAS, SETBP1, and RUNX1.

These same mutations are broadly associated with monosomy 7 in AML, which suggests that understanding how SAMD9 and SAMD9L mutations contribute to leukemia has implications beyond familial cases.

The presence of secondary mutations may also help clinicians identify which patients will benefit from immediate treatment, including chemotherapy or transplant to prevent or treat AML or myelodysplasia, Dr Klco said.

For patients without the mutations or significant symptoms due to low blood cell counts, watchful waiting with careful follow-up may sometimes be an option.

“Now that we know this disease can resolve without treatment in some patients, we need to focus on developing screening and treatment guidelines,” Dr Klco said. “We want to reserve hematopoietic bone marrow transplantation for those who truly need the procedure. These findings will help to point the way.”

“So little is known about SAMD9 and SAMD9L that we need to continue working in the lab to better understand how these mutations impact blood cell development and how they are activated in response to infections and other types of stress.”

New findings could help improve treatment of an inherited bone marrow disorder known as myelodysplasia and leukemia syndrome with monosomy 7 (MLSM7), according to researchers.

While studying families affected by MLSM7, researchers identified germline mutations in SAMD9L or SAMD9 in patients who had hematologic abnormalities, myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), or acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

However, these mutations were also present in apparently healthy family members, and the researchers found that bone marrow monosomy 7 sometimes resolved without treatment.

The team recounted these findings in JCI Insight.

The researchers analyzed blood samples from 16 siblings in 5 families affected by MLSM7 and found they all carried germline mutations in SAMD9 or SAMD9L. In 3 of the 5 families, there were apparently healthy parents who also carried the mutations.

“Surprisingly, the health consequences of these mutations varied tremendously for reasons that must still be determined, but the findings are already affecting how we may choose to manage these patients,” said study author Jeffery Klco, MD, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee.

Three of the 16 siblings developed AML and died of the disease or related complications. Two other siblings were diagnosed with MDS.

The remaining 11 siblings with the mutations were apparently healthy, although several had been treated for anemia and other conditions associated with low blood counts.

Some of these patients had a previous history of bone marrow monosomy 7 that spontaneously corrected over time. These patients, despite no therapy, appeared to have normal bone marrow function.

“This was an even greater surprise,” Dr Klco said. “The spontaneous recovery experienced by some children with the germline mutations suggests some patients with SAMD9 and SAMD9L mutations who were previously considered candidates for bone marrow transplantation may recover hematologic function on their own.”

Dr Klco and his colleagues have a theory that could explain the spontaneous correction. The team noted that SAMD9 and SAMD9L are activated in response to viral infections. While the normal function of both proteins is poorly understood, abnormally activated SAMD9 and SAMD9L are known to inhibit cell growth.

In this study, deep sequencing showed that selective pressure on developing blood cells favors cells without the SAMD9 or SAMD9L mutations. That may increase pressure for cells to selectively jettison chromosome 7 with the gene alteration or take other molecular measures to counteract the mutant protein.

Implications for treatment

This research also showed that, in patients who developed AML, loss of chromosome 7 was associated with the development of mutations in additional genes, including ETV6, KRAS, SETBP1, and RUNX1.

These same mutations are broadly associated with monosomy 7 in AML, which suggests that understanding how SAMD9 and SAMD9L mutations contribute to leukemia has implications beyond familial cases.

The presence of secondary mutations may also help clinicians identify which patients will benefit from immediate treatment, including chemotherapy or transplant to prevent or treat AML or myelodysplasia, Dr Klco said.

For patients without the mutations or significant symptoms due to low blood cell counts, watchful waiting with careful follow-up may sometimes be an option.

“Now that we know this disease can resolve without treatment in some patients, we need to focus on developing screening and treatment guidelines,” Dr Klco said. “We want to reserve hematopoietic bone marrow transplantation for those who truly need the procedure. These findings will help to point the way.”

“So little is known about SAMD9 and SAMD9L that we need to continue working in the lab to better understand how these mutations impact blood cell development and how they are activated in response to infections and other types of stress.”

Gene therapy granted accelerated assessment

The European Medicines Agency’s (EMA) Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use has granted accelerated assessment for the upcoming marketing authorization application (MAA) for LentiGlobin™.

LentiGlobin is a gene therapy intended for the treatment of adolescents and adults with transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia (TDT) and a non-β0/β0 genotype.

bluebird bio intends to file an MAA for LentiGlobin with the EMA this year.

Accelerated assessment can reduce the active review time of an MAA from 210 days to 150 days once it has been validated by the EMA.

An accelerated assessment is granted to products deemed to be of major interest for public health and represent therapeutic innovation.

The accelerated assessment for LentiGlobin is supported by data from clinical studies, including the phase 1/2 Northstar (HGB-204) study, phase 1/2 HGB-205 study, phase 3 Northstar-2 (HGB-207) study, and the long-term follow-up study LTF-303.

The EMA previously granted PRIME (Priority Medicines) eligibility and orphan designation to LentiGlobin for the treatment of TDT.

LentiGlobin is also part of the EMA’s Adaptive Pathways pilot program, which is part of the EMA’s effort to improve timely access to new medicines.

Phase 1/2 trials

Results from the phase 1/2 trials of LentiGlobin—HGB-204 and HGB-205—were published in NEJM in April.

HGB-204 is a completed study that included 18 patients with TDT. Eight patients had a β0/β0 genotype, 6 had a βE/β0 genotype, and 4 had other genotypes.

HGB-205 is an ongoing study, and results were reported for 4 patients with TDT. Three patients had a βE/β0 genotype. The remaining patient was homozygous for the IVS1-110 mutation and had a severe clinical presentation similar to that seen in β0/β0 genotypes.

For both studies, the researchers harvested hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (mobilized with filgrastim and plerixafor) from the patients. CD34+ cells were transduced ex vivo with LentiGlobin BB305 vector, which encodes adult hemoglobin (HbA) with a T87Q amino acid substitution (HbAT87Q).

The patients underwent myeloablative conditioning with busulfan, and the final LentiGlobin product was infused into patients after a 72-hour washout period.

In HGB-205 only, patients received enhanced red blood cell (RBC) transfusions for at least 3 months before stem cell mobilization and harvest to maintain a hemoglobin level of more than 11.0 g/dL.

Safety

In HGB-204, there were 5 grade 1 adverse events (AEs) considered possibly or probably related to LentiGlobin—abdominal pain (n=2), dyspnea (n=1), hot flush (n=1), and non-cardiac chest pain (n=1).

There were 9 serious AEs. Grade 3 serious AEs included 2 episodes of veno-occlusive liver disease that were attributed to busulfan, Klebsiella infection, cardiac ventricular thrombosis, cellulitis, hyperglycemia, and gastroenteritis. Grade 2 serious AEs included device-related thrombosis and infectious diarrhea.

In HGB-205, there were no AEs considered possibly or probably related to LentiGlobin. The 3 serious AEs were tooth infection (grade 3), major depression (grade 3), and pneumonia (grade 2).

Efficacy

The median time to neutrophil engraftment was 18.5 days (range, 14.0 to 30.0) in HGB-204 and 16.5 days (range, 14.0 to 29.0) in HGB-205.

The median time to platelet engraftment was 39.5 days (range, 19.0 to 191.0) and 23.0 days (range, 20.0 to 26.0), respectively.

In both studies, the median follow-up was 26 months (range, 15 to 42) after LentiGlobin infusion.

At last follow-up, all but 1 of the 13 patients with a non-β0/β0 genotype had stopped receiving RBC transfusions.

In the 8 patients with a β0/β0 genotype and the 1 patient with 2 copies of the IVS1-110 mutation, the median annualized transfusion volume decreased by 73% after LentiGlobin administration.

Two patients with a β0/β0 genotype were able to stop receiving RBC transfusions, as was the patient with 2 copies of the IVS1-110 mutation.

The European Medicines Agency’s (EMA) Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use has granted accelerated assessment for the upcoming marketing authorization application (MAA) for LentiGlobin™.

LentiGlobin is a gene therapy intended for the treatment of adolescents and adults with transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia (TDT) and a non-β0/β0 genotype.

bluebird bio intends to file an MAA for LentiGlobin with the EMA this year.

Accelerated assessment can reduce the active review time of an MAA from 210 days to 150 days once it has been validated by the EMA.

An accelerated assessment is granted to products deemed to be of major interest for public health and represent therapeutic innovation.

The accelerated assessment for LentiGlobin is supported by data from clinical studies, including the phase 1/2 Northstar (HGB-204) study, phase 1/2 HGB-205 study, phase 3 Northstar-2 (HGB-207) study, and the long-term follow-up study LTF-303.

The EMA previously granted PRIME (Priority Medicines) eligibility and orphan designation to LentiGlobin for the treatment of TDT.

LentiGlobin is also part of the EMA’s Adaptive Pathways pilot program, which is part of the EMA’s effort to improve timely access to new medicines.

Phase 1/2 trials

Results from the phase 1/2 trials of LentiGlobin—HGB-204 and HGB-205—were published in NEJM in April.

HGB-204 is a completed study that included 18 patients with TDT. Eight patients had a β0/β0 genotype, 6 had a βE/β0 genotype, and 4 had other genotypes.

HGB-205 is an ongoing study, and results were reported for 4 patients with TDT. Three patients had a βE/β0 genotype. The remaining patient was homozygous for the IVS1-110 mutation and had a severe clinical presentation similar to that seen in β0/β0 genotypes.

For both studies, the researchers harvested hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (mobilized with filgrastim and plerixafor) from the patients. CD34+ cells were transduced ex vivo with LentiGlobin BB305 vector, which encodes adult hemoglobin (HbA) with a T87Q amino acid substitution (HbAT87Q).

The patients underwent myeloablative conditioning with busulfan, and the final LentiGlobin product was infused into patients after a 72-hour washout period.

In HGB-205 only, patients received enhanced red blood cell (RBC) transfusions for at least 3 months before stem cell mobilization and harvest to maintain a hemoglobin level of more than 11.0 g/dL.

Safety

In HGB-204, there were 5 grade 1 adverse events (AEs) considered possibly or probably related to LentiGlobin—abdominal pain (n=2), dyspnea (n=1), hot flush (n=1), and non-cardiac chest pain (n=1).

There were 9 serious AEs. Grade 3 serious AEs included 2 episodes of veno-occlusive liver disease that were attributed to busulfan, Klebsiella infection, cardiac ventricular thrombosis, cellulitis, hyperglycemia, and gastroenteritis. Grade 2 serious AEs included device-related thrombosis and infectious diarrhea.

In HGB-205, there were no AEs considered possibly or probably related to LentiGlobin. The 3 serious AEs were tooth infection (grade 3), major depression (grade 3), and pneumonia (grade 2).

Efficacy

The median time to neutrophil engraftment was 18.5 days (range, 14.0 to 30.0) in HGB-204 and 16.5 days (range, 14.0 to 29.0) in HGB-205.

The median time to platelet engraftment was 39.5 days (range, 19.0 to 191.0) and 23.0 days (range, 20.0 to 26.0), respectively.

In both studies, the median follow-up was 26 months (range, 15 to 42) after LentiGlobin infusion.

At last follow-up, all but 1 of the 13 patients with a non-β0/β0 genotype had stopped receiving RBC transfusions.

In the 8 patients with a β0/β0 genotype and the 1 patient with 2 copies of the IVS1-110 mutation, the median annualized transfusion volume decreased by 73% after LentiGlobin administration.

Two patients with a β0/β0 genotype were able to stop receiving RBC transfusions, as was the patient with 2 copies of the IVS1-110 mutation.

The European Medicines Agency’s (EMA) Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use has granted accelerated assessment for the upcoming marketing authorization application (MAA) for LentiGlobin™.

LentiGlobin is a gene therapy intended for the treatment of adolescents and adults with transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia (TDT) and a non-β0/β0 genotype.

bluebird bio intends to file an MAA for LentiGlobin with the EMA this year.

Accelerated assessment can reduce the active review time of an MAA from 210 days to 150 days once it has been validated by the EMA.

An accelerated assessment is granted to products deemed to be of major interest for public health and represent therapeutic innovation.

The accelerated assessment for LentiGlobin is supported by data from clinical studies, including the phase 1/2 Northstar (HGB-204) study, phase 1/2 HGB-205 study, phase 3 Northstar-2 (HGB-207) study, and the long-term follow-up study LTF-303.

The EMA previously granted PRIME (Priority Medicines) eligibility and orphan designation to LentiGlobin for the treatment of TDT.

LentiGlobin is also part of the EMA’s Adaptive Pathways pilot program, which is part of the EMA’s effort to improve timely access to new medicines.

Phase 1/2 trials

Results from the phase 1/2 trials of LentiGlobin—HGB-204 and HGB-205—were published in NEJM in April.

HGB-204 is a completed study that included 18 patients with TDT. Eight patients had a β0/β0 genotype, 6 had a βE/β0 genotype, and 4 had other genotypes.

HGB-205 is an ongoing study, and results were reported for 4 patients with TDT. Three patients had a βE/β0 genotype. The remaining patient was homozygous for the IVS1-110 mutation and had a severe clinical presentation similar to that seen in β0/β0 genotypes.

For both studies, the researchers harvested hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (mobilized with filgrastim and plerixafor) from the patients. CD34+ cells were transduced ex vivo with LentiGlobin BB305 vector, which encodes adult hemoglobin (HbA) with a T87Q amino acid substitution (HbAT87Q).

The patients underwent myeloablative conditioning with busulfan, and the final LentiGlobin product was infused into patients after a 72-hour washout period.

In HGB-205 only, patients received enhanced red blood cell (RBC) transfusions for at least 3 months before stem cell mobilization and harvest to maintain a hemoglobin level of more than 11.0 g/dL.

Safety

In HGB-204, there were 5 grade 1 adverse events (AEs) considered possibly or probably related to LentiGlobin—abdominal pain (n=2), dyspnea (n=1), hot flush (n=1), and non-cardiac chest pain (n=1).

There were 9 serious AEs. Grade 3 serious AEs included 2 episodes of veno-occlusive liver disease that were attributed to busulfan, Klebsiella infection, cardiac ventricular thrombosis, cellulitis, hyperglycemia, and gastroenteritis. Grade 2 serious AEs included device-related thrombosis and infectious diarrhea.

In HGB-205, there were no AEs considered possibly or probably related to LentiGlobin. The 3 serious AEs were tooth infection (grade 3), major depression (grade 3), and pneumonia (grade 2).

Efficacy

The median time to neutrophil engraftment was 18.5 days (range, 14.0 to 30.0) in HGB-204 and 16.5 days (range, 14.0 to 29.0) in HGB-205.

The median time to platelet engraftment was 39.5 days (range, 19.0 to 191.0) and 23.0 days (range, 20.0 to 26.0), respectively.

In both studies, the median follow-up was 26 months (range, 15 to 42) after LentiGlobin infusion.

At last follow-up, all but 1 of the 13 patients with a non-β0/β0 genotype had stopped receiving RBC transfusions.

In the 8 patients with a β0/β0 genotype and the 1 patient with 2 copies of the IVS1-110 mutation, the median annualized transfusion volume decreased by 73% after LentiGlobin administration.

Two patients with a β0/β0 genotype were able to stop receiving RBC transfusions, as was the patient with 2 copies of the IVS1-110 mutation.

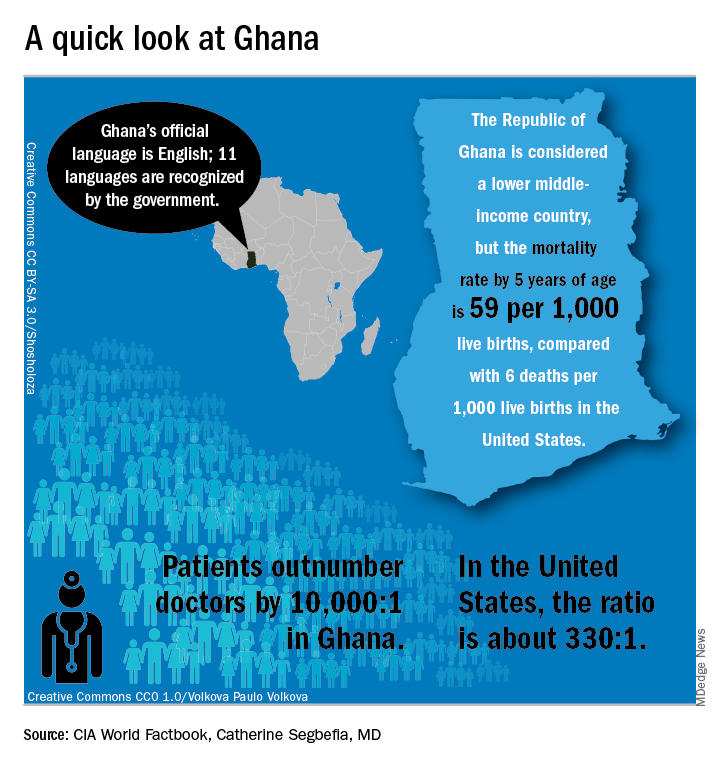

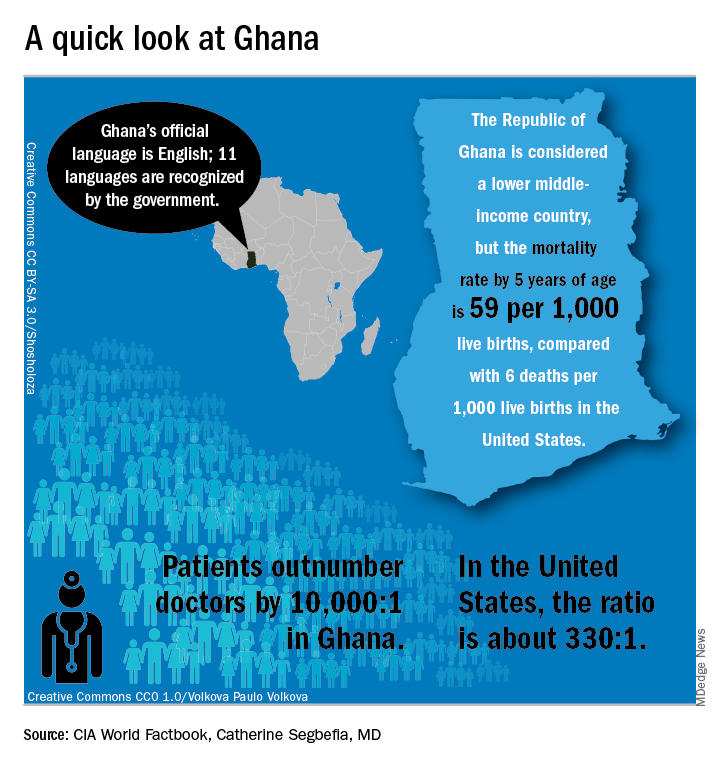

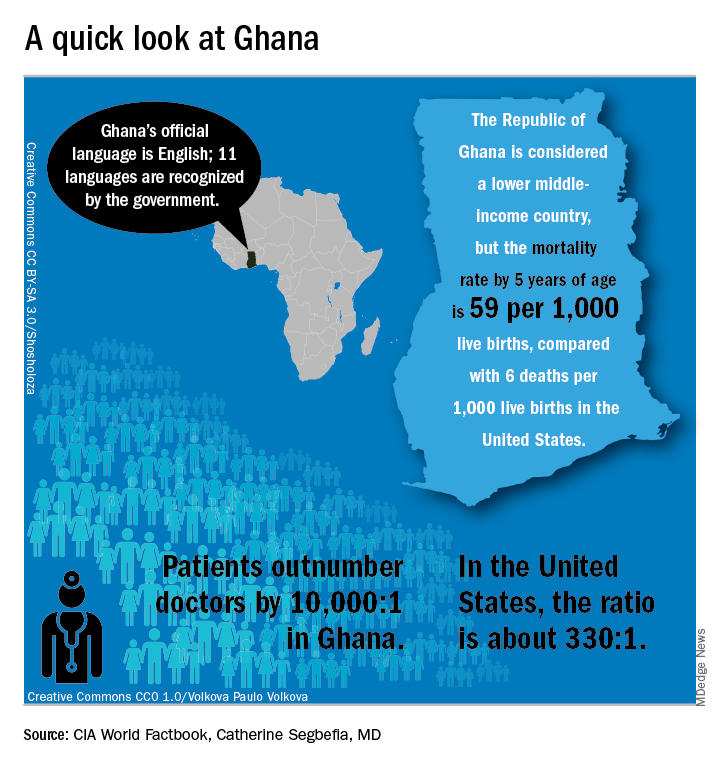

In Ghana, SCD research is meeting patients on home turf

WASHINGTON – Sometimes, the hardest part of solving a problem is figuring out how to work around misaligned resources, and so it has been with sickle cell disease research.

“From my point of view, what I call the geographical disparity in sickle cell disease research can be explained by the fact that the majority of affected individuals are living in the East, and the overwhelming majority of the research takes place in the West,” said Solomon Ofori-Acquah, PhD. He and three physician collaborators from Ghana shared their roadmap to conducting clinical trials in West Africa during an “East Meets West” session of the annual symposium of the Foundation for Sickle Cell Disease Research.

In Ghana, not far from where scientists now believe the hemoglobin sickling mutation originated, fully 2% of newborns have SCD; this translates into 16,000 new cases per year in a population of just 28 million, compared with the 2,000 new SCD cases seen annually in the entire United States. And access even to proven therapies can be limited; historically, little to no clinical drug development work has been conducted in this part of the world.

In the United States, half of the SCD trials that were withdrawn or terminated listed recruitment and retention of study participants as a factor in the study’s discontinuation, said Amma Owusu-Ansah, MD. “I see what we are doing as a very feasible solution to the problem of inadequate accrual to studies in the U.S.,” said Dr. Owusu-Ansah, a hematologist at the University of Pittsburgh’s Center for Translational and International Hematology (CTIH), where she serves as clinical director.

From the African perspective, hosting clinical trials – and building a robust infrastructure to do so – may help alleviate the delay in translation of disease-modifying therapies for SCD to Africa, where most people with the disease live, she said.

An existing example of resource sharing is the Human Heredity & Health in Africa (H3Africa) initiative, said Dr. Ofori-Acquah, who directs the CTIH and also holds an appointment at the University of Ghana. The project, funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Wellcome Trust, “aims to facilitate a contemporary research approach to the study of genomics and environmental determinants of common diseases with the goal of improving the health of African populations,” according to the H3Africa website. Within this framework of 40 research centers conducting genomics research and biobanking, several discrete projects aim to expand knowledge of sickle cell disease.

“All of these networks are going to study thousands of patients,” said Dr. Ofori-Acquah. “I see the H3 as a mechanism to accelerate genomics research in sickle cell disease.”

“We created a research team and built capacity for future work…. Ghana, and Africa, are capable of conducting clinical trials to global standards and producing quality data,” she said.

The story of one clinical trial is illustrative of the challenges and strengths of the multinational approach.

The phase 1b trial of a novel treatment for sickle cell disease, NVX-508, began with an initial hurdle of lack of access to emergency care at the study site, said Dr. Owusu-Ansah, a study investigator. Her first reaction, she said, was, “Well, we can’t do this, because we don’t have access to a big staff and emergency facilities.”

But after consulting with colleagues, she realized a shift in mindset was needed: “Rather than focus on what we don’t have, what do we actually have available? We have relationships we have built with institutions,” including the oldest SCD clinic in Ghana, the Ghana Institute of Clinical Genetics (GICG). This facility sits next door to a hospital with 24-hour care, Korle Bu Teaching Hospital (KBTH), a major tertiary care and referral center.

Open since 1974, the KBTH-allied GICG provides comprehensive outpatient health care to teens and adult with SCD. Currently, more than 25,000 SCD patients are registered at GICG; about half have the HbSS genotype, and another 40% have the HbSC genotype, said Yvonne Dei-Adomakoh, MD. Dr. Dei-Adomakoh of the University of Ghana is an investigator for an upcoming phase 3 trial to test voxelotor against placebo in SCD.

The GICG is working hard to become a site where clinical trials, as well as research and development, are embedded into clinic functions. In this way, not only will research be advanced for all those with SCD, but advances will be more easily incorporated into clinical care, said Dr. Dei-Adomakoh.

Dr. Owusu-Ansah noted that the facility offers a pharmacy, a laboratory, exam rooms, and information technology and medical record resources. Importantly, GICG is already staffed with physicians and allied health personnel with SCD expertise.

The University of Ghana campus is home to one of Africa’s leading biomedical research facilities, a sophisticated 11,000-square-foot laboratory that can perform testing ranging from polymerase chain reactions to DNA sequencing to genotyping and flow cytometry; it also houses a laboratory animal facility. This laboratory, the Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research, also offers administrative, scientific, and research support, and houses an institutional review board.

The problem of the Noguchi laboratory site’s distance from the 24-hour support of KBTH has been solved by arranging to have an ambulance with paramedics available on site during the clinical trials.

Some other challenges the investigators discovered highlighted less-obvious infrastructure deficits; keeping a refrigerated chain of custody for biological samples, for example, can be difficult. In preparation for the trials, much basic laboratory and clinical equipment has been updated.

Conducting a U.S.-registered clinical trial in Ghana doesn’t obviate the need to meet that country’s considerable regulatory hurdles, said Dr. Owusu-Ansah. Requirements include a full regulatory submission to, and physical inspection by, Ghana’s FDA. Ghana also requires that the principal investigator must live in Ghana for the duration of the trial and that key study personnel complete Ghanaian good clinical practices training, she said.

The University of Pittsburgh is a U.S. partner in the NVX-508 study, and it was non-negotiable for that institution that a clinical trial monitor visit the African study sites. The institution’s institutional review board was sensitive to the importance of protecting vulnerable populations, and needed to hear complete plans for risk assessment, data protection, and compensation for Ghanaian study participants, Dr. Owusu-Ansah said.

But, in a turn of events typical of the ups and downs of drug development, the phase 1 trial had passed most of the administrative hurdles when in July the drug’s sponsor, NuvOx Pharma, suspended the NVX-508 trial to focus on other areas. For now, the trial registration has been withdrawn on clinicaltrials.gov and the new drug application is inactive. But Dr. Owusu-Ansah said study preparations could resume in the future, if the drug is made available to investigators.

Dr. Owusu-Ansah reported that she has received salary support from NuvOx Pharma. Dr. Segbefia reported that she has received support from Daiichi-Sankyo and Eli Lilly and Company.

WASHINGTON – Sometimes, the hardest part of solving a problem is figuring out how to work around misaligned resources, and so it has been with sickle cell disease research.

“From my point of view, what I call the geographical disparity in sickle cell disease research can be explained by the fact that the majority of affected individuals are living in the East, and the overwhelming majority of the research takes place in the West,” said Solomon Ofori-Acquah, PhD. He and three physician collaborators from Ghana shared their roadmap to conducting clinical trials in West Africa during an “East Meets West” session of the annual symposium of the Foundation for Sickle Cell Disease Research.

In Ghana, not far from where scientists now believe the hemoglobin sickling mutation originated, fully 2% of newborns have SCD; this translates into 16,000 new cases per year in a population of just 28 million, compared with the 2,000 new SCD cases seen annually in the entire United States. And access even to proven therapies can be limited; historically, little to no clinical drug development work has been conducted in this part of the world.

In the United States, half of the SCD trials that were withdrawn or terminated listed recruitment and retention of study participants as a factor in the study’s discontinuation, said Amma Owusu-Ansah, MD. “I see what we are doing as a very feasible solution to the problem of inadequate accrual to studies in the U.S.,” said Dr. Owusu-Ansah, a hematologist at the University of Pittsburgh’s Center for Translational and International Hematology (CTIH), where she serves as clinical director.

From the African perspective, hosting clinical trials – and building a robust infrastructure to do so – may help alleviate the delay in translation of disease-modifying therapies for SCD to Africa, where most people with the disease live, she said.

An existing example of resource sharing is the Human Heredity & Health in Africa (H3Africa) initiative, said Dr. Ofori-Acquah, who directs the CTIH and also holds an appointment at the University of Ghana. The project, funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Wellcome Trust, “aims to facilitate a contemporary research approach to the study of genomics and environmental determinants of common diseases with the goal of improving the health of African populations,” according to the H3Africa website. Within this framework of 40 research centers conducting genomics research and biobanking, several discrete projects aim to expand knowledge of sickle cell disease.

“All of these networks are going to study thousands of patients,” said Dr. Ofori-Acquah. “I see the H3 as a mechanism to accelerate genomics research in sickle cell disease.”

“We created a research team and built capacity for future work…. Ghana, and Africa, are capable of conducting clinical trials to global standards and producing quality data,” she said.

The story of one clinical trial is illustrative of the challenges and strengths of the multinational approach.

The phase 1b trial of a novel treatment for sickle cell disease, NVX-508, began with an initial hurdle of lack of access to emergency care at the study site, said Dr. Owusu-Ansah, a study investigator. Her first reaction, she said, was, “Well, we can’t do this, because we don’t have access to a big staff and emergency facilities.”

But after consulting with colleagues, she realized a shift in mindset was needed: “Rather than focus on what we don’t have, what do we actually have available? We have relationships we have built with institutions,” including the oldest SCD clinic in Ghana, the Ghana Institute of Clinical Genetics (GICG). This facility sits next door to a hospital with 24-hour care, Korle Bu Teaching Hospital (KBTH), a major tertiary care and referral center.

Open since 1974, the KBTH-allied GICG provides comprehensive outpatient health care to teens and adult with SCD. Currently, more than 25,000 SCD patients are registered at GICG; about half have the HbSS genotype, and another 40% have the HbSC genotype, said Yvonne Dei-Adomakoh, MD. Dr. Dei-Adomakoh of the University of Ghana is an investigator for an upcoming phase 3 trial to test voxelotor against placebo in SCD.

The GICG is working hard to become a site where clinical trials, as well as research and development, are embedded into clinic functions. In this way, not only will research be advanced for all those with SCD, but advances will be more easily incorporated into clinical care, said Dr. Dei-Adomakoh.

Dr. Owusu-Ansah noted that the facility offers a pharmacy, a laboratory, exam rooms, and information technology and medical record resources. Importantly, GICG is already staffed with physicians and allied health personnel with SCD expertise.

The University of Ghana campus is home to one of Africa’s leading biomedical research facilities, a sophisticated 11,000-square-foot laboratory that can perform testing ranging from polymerase chain reactions to DNA sequencing to genotyping and flow cytometry; it also houses a laboratory animal facility. This laboratory, the Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research, also offers administrative, scientific, and research support, and houses an institutional review board.

The problem of the Noguchi laboratory site’s distance from the 24-hour support of KBTH has been solved by arranging to have an ambulance with paramedics available on site during the clinical trials.

Some other challenges the investigators discovered highlighted less-obvious infrastructure deficits; keeping a refrigerated chain of custody for biological samples, for example, can be difficult. In preparation for the trials, much basic laboratory and clinical equipment has been updated.

Conducting a U.S.-registered clinical trial in Ghana doesn’t obviate the need to meet that country’s considerable regulatory hurdles, said Dr. Owusu-Ansah. Requirements include a full regulatory submission to, and physical inspection by, Ghana’s FDA. Ghana also requires that the principal investigator must live in Ghana for the duration of the trial and that key study personnel complete Ghanaian good clinical practices training, she said.

The University of Pittsburgh is a U.S. partner in the NVX-508 study, and it was non-negotiable for that institution that a clinical trial monitor visit the African study sites. The institution’s institutional review board was sensitive to the importance of protecting vulnerable populations, and needed to hear complete plans for risk assessment, data protection, and compensation for Ghanaian study participants, Dr. Owusu-Ansah said.

But, in a turn of events typical of the ups and downs of drug development, the phase 1 trial had passed most of the administrative hurdles when in July the drug’s sponsor, NuvOx Pharma, suspended the NVX-508 trial to focus on other areas. For now, the trial registration has been withdrawn on clinicaltrials.gov and the new drug application is inactive. But Dr. Owusu-Ansah said study preparations could resume in the future, if the drug is made available to investigators.

Dr. Owusu-Ansah reported that she has received salary support from NuvOx Pharma. Dr. Segbefia reported that she has received support from Daiichi-Sankyo and Eli Lilly and Company.

WASHINGTON – Sometimes, the hardest part of solving a problem is figuring out how to work around misaligned resources, and so it has been with sickle cell disease research.

“From my point of view, what I call the geographical disparity in sickle cell disease research can be explained by the fact that the majority of affected individuals are living in the East, and the overwhelming majority of the research takes place in the West,” said Solomon Ofori-Acquah, PhD. He and three physician collaborators from Ghana shared their roadmap to conducting clinical trials in West Africa during an “East Meets West” session of the annual symposium of the Foundation for Sickle Cell Disease Research.

In Ghana, not far from where scientists now believe the hemoglobin sickling mutation originated, fully 2% of newborns have SCD; this translates into 16,000 new cases per year in a population of just 28 million, compared with the 2,000 new SCD cases seen annually in the entire United States. And access even to proven therapies can be limited; historically, little to no clinical drug development work has been conducted in this part of the world.

In the United States, half of the SCD trials that were withdrawn or terminated listed recruitment and retention of study participants as a factor in the study’s discontinuation, said Amma Owusu-Ansah, MD. “I see what we are doing as a very feasible solution to the problem of inadequate accrual to studies in the U.S.,” said Dr. Owusu-Ansah, a hematologist at the University of Pittsburgh’s Center for Translational and International Hematology (CTIH), where she serves as clinical director.

From the African perspective, hosting clinical trials – and building a robust infrastructure to do so – may help alleviate the delay in translation of disease-modifying therapies for SCD to Africa, where most people with the disease live, she said.

An existing example of resource sharing is the Human Heredity & Health in Africa (H3Africa) initiative, said Dr. Ofori-Acquah, who directs the CTIH and also holds an appointment at the University of Ghana. The project, funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Wellcome Trust, “aims to facilitate a contemporary research approach to the study of genomics and environmental determinants of common diseases with the goal of improving the health of African populations,” according to the H3Africa website. Within this framework of 40 research centers conducting genomics research and biobanking, several discrete projects aim to expand knowledge of sickle cell disease.

“All of these networks are going to study thousands of patients,” said Dr. Ofori-Acquah. “I see the H3 as a mechanism to accelerate genomics research in sickle cell disease.”

“We created a research team and built capacity for future work…. Ghana, and Africa, are capable of conducting clinical trials to global standards and producing quality data,” she said.

The story of one clinical trial is illustrative of the challenges and strengths of the multinational approach.

The phase 1b trial of a novel treatment for sickle cell disease, NVX-508, began with an initial hurdle of lack of access to emergency care at the study site, said Dr. Owusu-Ansah, a study investigator. Her first reaction, she said, was, “Well, we can’t do this, because we don’t have access to a big staff and emergency facilities.”

But after consulting with colleagues, she realized a shift in mindset was needed: “Rather than focus on what we don’t have, what do we actually have available? We have relationships we have built with institutions,” including the oldest SCD clinic in Ghana, the Ghana Institute of Clinical Genetics (GICG). This facility sits next door to a hospital with 24-hour care, Korle Bu Teaching Hospital (KBTH), a major tertiary care and referral center.

Open since 1974, the KBTH-allied GICG provides comprehensive outpatient health care to teens and adult with SCD. Currently, more than 25,000 SCD patients are registered at GICG; about half have the HbSS genotype, and another 40% have the HbSC genotype, said Yvonne Dei-Adomakoh, MD. Dr. Dei-Adomakoh of the University of Ghana is an investigator for an upcoming phase 3 trial to test voxelotor against placebo in SCD.

The GICG is working hard to become a site where clinical trials, as well as research and development, are embedded into clinic functions. In this way, not only will research be advanced for all those with SCD, but advances will be more easily incorporated into clinical care, said Dr. Dei-Adomakoh.

Dr. Owusu-Ansah noted that the facility offers a pharmacy, a laboratory, exam rooms, and information technology and medical record resources. Importantly, GICG is already staffed with physicians and allied health personnel with SCD expertise.

The University of Ghana campus is home to one of Africa’s leading biomedical research facilities, a sophisticated 11,000-square-foot laboratory that can perform testing ranging from polymerase chain reactions to DNA sequencing to genotyping and flow cytometry; it also houses a laboratory animal facility. This laboratory, the Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research, also offers administrative, scientific, and research support, and houses an institutional review board.

The problem of the Noguchi laboratory site’s distance from the 24-hour support of KBTH has been solved by arranging to have an ambulance with paramedics available on site during the clinical trials.

Some other challenges the investigators discovered highlighted less-obvious infrastructure deficits; keeping a refrigerated chain of custody for biological samples, for example, can be difficult. In preparation for the trials, much basic laboratory and clinical equipment has been updated.

Conducting a U.S.-registered clinical trial in Ghana doesn’t obviate the need to meet that country’s considerable regulatory hurdles, said Dr. Owusu-Ansah. Requirements include a full regulatory submission to, and physical inspection by, Ghana’s FDA. Ghana also requires that the principal investigator must live in Ghana for the duration of the trial and that key study personnel complete Ghanaian good clinical practices training, she said.

The University of Pittsburgh is a U.S. partner in the NVX-508 study, and it was non-negotiable for that institution that a clinical trial monitor visit the African study sites. The institution’s institutional review board was sensitive to the importance of protecting vulnerable populations, and needed to hear complete plans for risk assessment, data protection, and compensation for Ghanaian study participants, Dr. Owusu-Ansah said.

But, in a turn of events typical of the ups and downs of drug development, the phase 1 trial had passed most of the administrative hurdles when in July the drug’s sponsor, NuvOx Pharma, suspended the NVX-508 trial to focus on other areas. For now, the trial registration has been withdrawn on clinicaltrials.gov and the new drug application is inactive. But Dr. Owusu-Ansah said study preparations could resume in the future, if the drug is made available to investigators.

Dr. Owusu-Ansah reported that she has received salary support from NuvOx Pharma. Dr. Segbefia reported that she has received support from Daiichi-Sankyo and Eli Lilly and Company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM FSCDR 2018

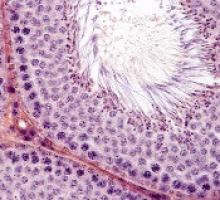

Treatments, disease affect spermatogonia in boys

Alkylating agents, hydroxyurea (HU), and certain non-malignant diseases can significantly deplete spermatogonial cell counts in young boys, according to research published in Human Reproduction.

Boys who received alkylating agents to treat cancer had significantly lower spermatogonial cell counts than control subjects or boys with malignant/nonmalignant diseases treated with non-alkylating agents.

Five of 6 SCD patients treated with HU had a totally depleted spermatogonial pool, and the remaining patient had a low spermatogonial cell count.

Five boys with non-malignant diseases who were not exposed to chemotherapy had significantly lower spermatogonial cell counts than controls.

“Our findings of a dramatic decrease in germ cell numbers in boys treated with alkylating agents and in sickle cell disease patients treated with hydroxyurea suggest that storing frozen testicular tissue from these boys should be performed before these treatments are initiated,” said study author Cecilia Petersen, MD, PhD, of Karolinska Institutet and University Hospital in Stockholm, Sweden.

“This needs to be communicated to physicians as well as patients and their parents or carers. However, until sperm that are able to fertilize eggs are produced from stored testicular tissue, we cannot confirm that germ cell quantity might determine the success of transplantation of the tissue in adulthood. Further research on this is needed to establish a realistic fertility preservation technique.”

Dr Petersen and her colleagues also noted that preserving testicular tissue may not be a viable option for boys who have low spermatogonial cell counts prior to treatment.

Patients and controls

For this study, the researchers analyzed testicular tissue from 32 boys facing treatments that carried a high risk of infertility—testicular irradiation, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy in advance of stem cell transplant.

Twenty boys had the tissue taken after initial chemotherapy, and 12 had it taken before starting any treatment.1

Eight patients had received chemotherapy with non-alkylating agents, 6 (all with malignancies) had received alkylating agents, and 6 (all with SCD) had received HU.

Diseases included acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n=6), SCD (n=6), acute myeloid leukemia (n=3), thalassemia major (n=3), neuroblastoma (n=2), juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (n=2), myelodysplastic syndromes (n=2), primary immunodeficiency (n=2), Wilms tumor (n=1), adrenoleukodystrophy (n=1), hepatoblastoma (n=1), primitive neuroectodermal tumor (n=1), severe aplastic anemia (n=1), and Fanconi anemia (n=1).

The researchers compared samples from these 32 patients to 14 healthy testicular tissue samples stored in the biobank at the Karolinska University Hospital.

For both sample types, the team counted the number of spermatogonial cells found in a cross-section of seminiferous tubules.

“We could compare the number of spermatogonia with those found in the healthy boys as a way to estimate the effect of medical treatment or the disease itself on the future fertility of a patient,” explained study author Jan-Bernd Stukenborg, PhD, of Karolinska Institutet and University Hospital.

Impact of treatment

There was no significant difference in the mean quantity of spermatogonia per transverse tubular cross-section (S/T) between patients exposed to non-alkylating agents (1.7 ± 1.0, n=8) and biobank controls (4.1 ± 4.6, n=14).

However, samples from patients who received alkylating agents had a significantly lower mean S/T value (0.2 ± 0.3, n=6) than samples from patients treated with non-alkylating agents (P=0.003) and biobank controls (P<0.001).

“We found that the numbers of germ cells present in the cross-sections of the seminiferous tubules were significantly depleted and close to 0 in patients treated with alkylating agents,” Dr Stukenborg said.

Samples from the SCD patients also had a significantly lower mean S/T value (0.3 ± 0.6, n=6) than biobank controls (P=0.003).

Dr Stukenborg noted that the germ cell pool was totally depleted in 5 of the boys with SCD, and the pool was “very low” in the sixth SCD patient.

“This was not seen in patients who had not started treatment or were treated with non-alkylating agents or in the biobank tissues,” Dr Stukenborg said.2

He and his colleagues noted that it is possible for germ cells to recover to normal levels after treatment that is highly toxic to the testes, but high doses of alkylating agents and radiotherapy to the testicles are strongly associated with permanent or long-term infertility.

“The first group of boys who received bone marrow transplants are now reaching their thirties,” said study author Kirsi Jahnukainen, MD, PhD, of Helsinki University Central Hospital in Finland.

“Recent data suggest they may have a high chance of their sperm production recovering, even if they received high-dose alkylating therapies, so long as they had no testicular irradiation.”

Impact of disease

The researchers also found evidence to suggest that, for some boys, their disease may have affected spermatogonial cell counts before any treatment began.

Five patients with non-malignant disease who had not been exposed to chemotherapy (3 with thalassemia major, 1 with Fanconi anemia, and 1 with primary immunodeficiency) had a significantly lower mean S/T value (0.4 ± 0.5) than controls (P=0.006).

“Among patients who had not been treated previously with chemotherapy, there were several boys with a low number of germ cells for their age,” Dr Jahnukainen said.

“This suggests that some non-malignant diseases that require bone marrow transplants may affect the fertility of young boys even before exposure to therapy that is toxic for the testes.”

The researchers noted that a limitation of this study was that biobank samples had no detailed information regarding previous medical treatments and testicular volumes.

1. Testicular tissue is taken from patients under general anesthesia. The surgeon removes approximately 20% of the tissue from the testicular capsule in one of the testicles. For this study, a third of the tissue was taken to the Karolinska Institutet for analysis.

2. A recent meta-analysis showed that normal testicular tissue samples of newborns contain approximately 2.5 germ cells per tubular cross-section. This number decreases to approximately 1.2 within the first 3 years of age, followed by an increase up to 2.6 germ cells per tubular cross-section at 6 to 7 years, reaching a plateau until the age of 11. At the onset of puberty, an increase of up to 7 spermatogonia per tubular cross-section could be observed.

Alkylating agents, hydroxyurea (HU), and certain non-malignant diseases can significantly deplete spermatogonial cell counts in young boys, according to research published in Human Reproduction.

Boys who received alkylating agents to treat cancer had significantly lower spermatogonial cell counts than control subjects or boys with malignant/nonmalignant diseases treated with non-alkylating agents.

Five of 6 SCD patients treated with HU had a totally depleted spermatogonial pool, and the remaining patient had a low spermatogonial cell count.

Five boys with non-malignant diseases who were not exposed to chemotherapy had significantly lower spermatogonial cell counts than controls.

“Our findings of a dramatic decrease in germ cell numbers in boys treated with alkylating agents and in sickle cell disease patients treated with hydroxyurea suggest that storing frozen testicular tissue from these boys should be performed before these treatments are initiated,” said study author Cecilia Petersen, MD, PhD, of Karolinska Institutet and University Hospital in Stockholm, Sweden.

“This needs to be communicated to physicians as well as patients and their parents or carers. However, until sperm that are able to fertilize eggs are produced from stored testicular tissue, we cannot confirm that germ cell quantity might determine the success of transplantation of the tissue in adulthood. Further research on this is needed to establish a realistic fertility preservation technique.”

Dr Petersen and her colleagues also noted that preserving testicular tissue may not be a viable option for boys who have low spermatogonial cell counts prior to treatment.

Patients and controls

For this study, the researchers analyzed testicular tissue from 32 boys facing treatments that carried a high risk of infertility—testicular irradiation, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy in advance of stem cell transplant.

Twenty boys had the tissue taken after initial chemotherapy, and 12 had it taken before starting any treatment.1

Eight patients had received chemotherapy with non-alkylating agents, 6 (all with malignancies) had received alkylating agents, and 6 (all with SCD) had received HU.

Diseases included acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n=6), SCD (n=6), acute myeloid leukemia (n=3), thalassemia major (n=3), neuroblastoma (n=2), juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (n=2), myelodysplastic syndromes (n=2), primary immunodeficiency (n=2), Wilms tumor (n=1), adrenoleukodystrophy (n=1), hepatoblastoma (n=1), primitive neuroectodermal tumor (n=1), severe aplastic anemia (n=1), and Fanconi anemia (n=1).

The researchers compared samples from these 32 patients to 14 healthy testicular tissue samples stored in the biobank at the Karolinska University Hospital.

For both sample types, the team counted the number of spermatogonial cells found in a cross-section of seminiferous tubules.

“We could compare the number of spermatogonia with those found in the healthy boys as a way to estimate the effect of medical treatment or the disease itself on the future fertility of a patient,” explained study author Jan-Bernd Stukenborg, PhD, of Karolinska Institutet and University Hospital.

Impact of treatment

There was no significant difference in the mean quantity of spermatogonia per transverse tubular cross-section (S/T) between patients exposed to non-alkylating agents (1.7 ± 1.0, n=8) and biobank controls (4.1 ± 4.6, n=14).

However, samples from patients who received alkylating agents had a significantly lower mean S/T value (0.2 ± 0.3, n=6) than samples from patients treated with non-alkylating agents (P=0.003) and biobank controls (P<0.001).

“We found that the numbers of germ cells present in the cross-sections of the seminiferous tubules were significantly depleted and close to 0 in patients treated with alkylating agents,” Dr Stukenborg said.

Samples from the SCD patients also had a significantly lower mean S/T value (0.3 ± 0.6, n=6) than biobank controls (P=0.003).

Dr Stukenborg noted that the germ cell pool was totally depleted in 5 of the boys with SCD, and the pool was “very low” in the sixth SCD patient.

“This was not seen in patients who had not started treatment or were treated with non-alkylating agents or in the biobank tissues,” Dr Stukenborg said.2

He and his colleagues noted that it is possible for germ cells to recover to normal levels after treatment that is highly toxic to the testes, but high doses of alkylating agents and radiotherapy to the testicles are strongly associated with permanent or long-term infertility.

“The first group of boys who received bone marrow transplants are now reaching their thirties,” said study author Kirsi Jahnukainen, MD, PhD, of Helsinki University Central Hospital in Finland.

“Recent data suggest they may have a high chance of their sperm production recovering, even if they received high-dose alkylating therapies, so long as they had no testicular irradiation.”

Impact of disease

The researchers also found evidence to suggest that, for some boys, their disease may have affected spermatogonial cell counts before any treatment began.

Five patients with non-malignant disease who had not been exposed to chemotherapy (3 with thalassemia major, 1 with Fanconi anemia, and 1 with primary immunodeficiency) had a significantly lower mean S/T value (0.4 ± 0.5) than controls (P=0.006).

“Among patients who had not been treated previously with chemotherapy, there were several boys with a low number of germ cells for their age,” Dr Jahnukainen said.

“This suggests that some non-malignant diseases that require bone marrow transplants may affect the fertility of young boys even before exposure to therapy that is toxic for the testes.”

The researchers noted that a limitation of this study was that biobank samples had no detailed information regarding previous medical treatments and testicular volumes.

1. Testicular tissue is taken from patients under general anesthesia. The surgeon removes approximately 20% of the tissue from the testicular capsule in one of the testicles. For this study, a third of the tissue was taken to the Karolinska Institutet for analysis.

2. A recent meta-analysis showed that normal testicular tissue samples of newborns contain approximately 2.5 germ cells per tubular cross-section. This number decreases to approximately 1.2 within the first 3 years of age, followed by an increase up to 2.6 germ cells per tubular cross-section at 6 to 7 years, reaching a plateau until the age of 11. At the onset of puberty, an increase of up to 7 spermatogonia per tubular cross-section could be observed.

Alkylating agents, hydroxyurea (HU), and certain non-malignant diseases can significantly deplete spermatogonial cell counts in young boys, according to research published in Human Reproduction.

Boys who received alkylating agents to treat cancer had significantly lower spermatogonial cell counts than control subjects or boys with malignant/nonmalignant diseases treated with non-alkylating agents.

Five of 6 SCD patients treated with HU had a totally depleted spermatogonial pool, and the remaining patient had a low spermatogonial cell count.

Five boys with non-malignant diseases who were not exposed to chemotherapy had significantly lower spermatogonial cell counts than controls.

“Our findings of a dramatic decrease in germ cell numbers in boys treated with alkylating agents and in sickle cell disease patients treated with hydroxyurea suggest that storing frozen testicular tissue from these boys should be performed before these treatments are initiated,” said study author Cecilia Petersen, MD, PhD, of Karolinska Institutet and University Hospital in Stockholm, Sweden.

“This needs to be communicated to physicians as well as patients and their parents or carers. However, until sperm that are able to fertilize eggs are produced from stored testicular tissue, we cannot confirm that germ cell quantity might determine the success of transplantation of the tissue in adulthood. Further research on this is needed to establish a realistic fertility preservation technique.”

Dr Petersen and her colleagues also noted that preserving testicular tissue may not be a viable option for boys who have low spermatogonial cell counts prior to treatment.

Patients and controls

For this study, the researchers analyzed testicular tissue from 32 boys facing treatments that carried a high risk of infertility—testicular irradiation, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy in advance of stem cell transplant.

Twenty boys had the tissue taken after initial chemotherapy, and 12 had it taken before starting any treatment.1

Eight patients had received chemotherapy with non-alkylating agents, 6 (all with malignancies) had received alkylating agents, and 6 (all with SCD) had received HU.

Diseases included acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n=6), SCD (n=6), acute myeloid leukemia (n=3), thalassemia major (n=3), neuroblastoma (n=2), juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (n=2), myelodysplastic syndromes (n=2), primary immunodeficiency (n=2), Wilms tumor (n=1), adrenoleukodystrophy (n=1), hepatoblastoma (n=1), primitive neuroectodermal tumor (n=1), severe aplastic anemia (n=1), and Fanconi anemia (n=1).

The researchers compared samples from these 32 patients to 14 healthy testicular tissue samples stored in the biobank at the Karolinska University Hospital.

For both sample types, the team counted the number of spermatogonial cells found in a cross-section of seminiferous tubules.

“We could compare the number of spermatogonia with those found in the healthy boys as a way to estimate the effect of medical treatment or the disease itself on the future fertility of a patient,” explained study author Jan-Bernd Stukenborg, PhD, of Karolinska Institutet and University Hospital.

Impact of treatment

There was no significant difference in the mean quantity of spermatogonia per transverse tubular cross-section (S/T) between patients exposed to non-alkylating agents (1.7 ± 1.0, n=8) and biobank controls (4.1 ± 4.6, n=14).

However, samples from patients who received alkylating agents had a significantly lower mean S/T value (0.2 ± 0.3, n=6) than samples from patients treated with non-alkylating agents (P=0.003) and biobank controls (P<0.001).

“We found that the numbers of germ cells present in the cross-sections of the seminiferous tubules were significantly depleted and close to 0 in patients treated with alkylating agents,” Dr Stukenborg said.

Samples from the SCD patients also had a significantly lower mean S/T value (0.3 ± 0.6, n=6) than biobank controls (P=0.003).

Dr Stukenborg noted that the germ cell pool was totally depleted in 5 of the boys with SCD, and the pool was “very low” in the sixth SCD patient.

“This was not seen in patients who had not started treatment or were treated with non-alkylating agents or in the biobank tissues,” Dr Stukenborg said.2

He and his colleagues noted that it is possible for germ cells to recover to normal levels after treatment that is highly toxic to the testes, but high doses of alkylating agents and radiotherapy to the testicles are strongly associated with permanent or long-term infertility.

“The first group of boys who received bone marrow transplants are now reaching their thirties,” said study author Kirsi Jahnukainen, MD, PhD, of Helsinki University Central Hospital in Finland.

“Recent data suggest they may have a high chance of their sperm production recovering, even if they received high-dose alkylating therapies, so long as they had no testicular irradiation.”

Impact of disease

The researchers also found evidence to suggest that, for some boys, their disease may have affected spermatogonial cell counts before any treatment began.

Five patients with non-malignant disease who had not been exposed to chemotherapy (3 with thalassemia major, 1 with Fanconi anemia, and 1 with primary immunodeficiency) had a significantly lower mean S/T value (0.4 ± 0.5) than controls (P=0.006).

“Among patients who had not been treated previously with chemotherapy, there were several boys with a low number of germ cells for their age,” Dr Jahnukainen said.

“This suggests that some non-malignant diseases that require bone marrow transplants may affect the fertility of young boys even before exposure to therapy that is toxic for the testes.”

The researchers noted that a limitation of this study was that biobank samples had no detailed information regarding previous medical treatments and testicular volumes.

1. Testicular tissue is taken from patients under general anesthesia. The surgeon removes approximately 20% of the tissue from the testicular capsule in one of the testicles. For this study, a third of the tissue was taken to the Karolinska Institutet for analysis.

2. A recent meta-analysis showed that normal testicular tissue samples of newborns contain approximately 2.5 germ cells per tubular cross-section. This number decreases to approximately 1.2 within the first 3 years of age, followed by an increase up to 2.6 germ cells per tubular cross-section at 6 to 7 years, reaching a plateau until the age of 11. At the onset of puberty, an increase of up to 7 spermatogonia per tubular cross-section could be observed.

FDA approves biosimilar filgrastim

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the leukocyte growth factor Nivestym™ (filgrastim-aafi), a biosimilar to Neupogen (filgrastim).

Nivestym is approved to treat patients with nonmyeloid malignancies who are receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy or undergoing bone marrow transplant, acute myeloid leukemia patients receiving induction or consolidation chemotherapy, patients undergoing autologous peripheral blood progenitor cell collection, and patients with severe chronic neutropenia.

The FDA’s approval of Nivestym was based on a review of evidence suggesting the drug is highly similar to Neupogen, according to Pfizer, the company developing Nivestym.

The full approved indication for Nivestym is as follows:

- To decrease the incidence of infection, as manifested by febrile neutropenia, in patients with nonmyeloid malignancies receiving myelosuppressive anticancer drugs associated with a significant incidence of severe neutropenia with fever

- To reduce the time to neutrophil recovery and the duration of fever following induction or consolidation chemotherapy in patients with acute myeloid leukemia

- To reduce the duration of neutropenia and neutropenia-related clinical sequelae (eg, febrile neutropenia) in patients with nonmyeloid malignancies undergoing myeloablative chemotherapy followed by bone marrow transplant

- For the mobilization of autologous hematopoietic progenitor cells into the peripheral blood for collection by leukapheresis

- For chronic administration to reduce the incidence and duration of sequelae of severe neutropenia (eg, fever, infections, oropharyngeal ulcers) in symptomatic patients with congenital neutropenia, cyclic neutropenia, or idiopathic neutropenia.

For more details on Nivestym, see the full prescribing information.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the leukocyte growth factor Nivestym™ (filgrastim-aafi), a biosimilar to Neupogen (filgrastim).

Nivestym is approved to treat patients with nonmyeloid malignancies who are receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy or undergoing bone marrow transplant, acute myeloid leukemia patients receiving induction or consolidation chemotherapy, patients undergoing autologous peripheral blood progenitor cell collection, and patients with severe chronic neutropenia.

The FDA’s approval of Nivestym was based on a review of evidence suggesting the drug is highly similar to Neupogen, according to Pfizer, the company developing Nivestym.

The full approved indication for Nivestym is as follows:

- To decrease the incidence of infection, as manifested by febrile neutropenia, in patients with nonmyeloid malignancies receiving myelosuppressive anticancer drugs associated with a significant incidence of severe neutropenia with fever

- To reduce the time to neutrophil recovery and the duration of fever following induction or consolidation chemotherapy in patients with acute myeloid leukemia

- To reduce the duration of neutropenia and neutropenia-related clinical sequelae (eg, febrile neutropenia) in patients with nonmyeloid malignancies undergoing myeloablative chemotherapy followed by bone marrow transplant

- For the mobilization of autologous hematopoietic progenitor cells into the peripheral blood for collection by leukapheresis

- For chronic administration to reduce the incidence and duration of sequelae of severe neutropenia (eg, fever, infections, oropharyngeal ulcers) in symptomatic patients with congenital neutropenia, cyclic neutropenia, or idiopathic neutropenia.

For more details on Nivestym, see the full prescribing information.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the leukocyte growth factor Nivestym™ (filgrastim-aafi), a biosimilar to Neupogen (filgrastim).

Nivestym is approved to treat patients with nonmyeloid malignancies who are receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy or undergoing bone marrow transplant, acute myeloid leukemia patients receiving induction or consolidation chemotherapy, patients undergoing autologous peripheral blood progenitor cell collection, and patients with severe chronic neutropenia.

The FDA’s approval of Nivestym was based on a review of evidence suggesting the drug is highly similar to Neupogen, according to Pfizer, the company developing Nivestym.

The full approved indication for Nivestym is as follows:

- To decrease the incidence of infection, as manifested by febrile neutropenia, in patients with nonmyeloid malignancies receiving myelosuppressive anticancer drugs associated with a significant incidence of severe neutropenia with fever

- To reduce the time to neutrophil recovery and the duration of fever following induction or consolidation chemotherapy in patients with acute myeloid leukemia

- To reduce the duration of neutropenia and neutropenia-related clinical sequelae (eg, febrile neutropenia) in patients with nonmyeloid malignancies undergoing myeloablative chemotherapy followed by bone marrow transplant

- For the mobilization of autologous hematopoietic progenitor cells into the peripheral blood for collection by leukapheresis

- For chronic administration to reduce the incidence and duration of sequelae of severe neutropenia (eg, fever, infections, oropharyngeal ulcers) in symptomatic patients with congenital neutropenia, cyclic neutropenia, or idiopathic neutropenia.

For more details on Nivestym, see the full prescribing information.

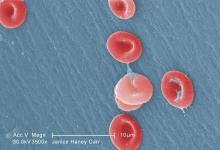

Kinase may be therapeutic target for hemoglobinopathies

A kinase called heme-regulated inhibitor (HRI) could be a therapeutic target for sickle cell disease (SCD) and some forms of β-thalassemia, according to researchers.

The team found that reducing the activity of HRI (also known as EIF2AK1) can boost the production of fetal hemoglobin (HbF).

Gerd Blobel MD, PhD, of The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania, and his colleagues reported this discovery in Science.

Dr Blobel noted that hydroxyurea remains the only approved drug that can increase fetal Hb in adults.

“Our goal was to identify new potential drug targets that regulate fetal Hb levels,” he said.

To that end, the researchers conducted a CRISPR-Cas9 screen targeting protein kinases. They designed a library of single-guide RNAs targeting 482 kinase domains, which covered almost all known kinases in the human genome.

The team attempted to determine if interference with any of the kinases in an immortalized human red blood cell line would increase HbF levels.

Results suggested that HRI, an erythroid-specific kinase that controls protein translation, is a repressor of HbF.

To confirm that HRI plays a key role in regulating HbF levels, the researchers depleted HRI in primary cultured human red blood cell precursors.

Reduced activity of HRI resulted in decreased phosphorylation of eIF2a and increased levels of HbF, but interfering with HRI levels did not impair cell viability or maturation.

The researchers next showed that HRI was a repressor of HbF in cultured primary cells from patients with SCD.

When HRI levels were artificially reduced, HbF levels were significantly increased, and cells were less prone to sickling. This suggested to the researchers that “HRI depletion may achieve therapeutically relevant levels of HbF.”

Mechanistically, the effects of HRI on HbF were shown to occur, in large measure, through modulating the activity of BCL11A, a direct repressor of HbF transcription.

The observation that HRI inhibition elevated HbF levels and reduced cell sickling in culture suggested that future pharmacologic HRI inhibitors might provide clinical benefit in patients with SCD.

To that end, an important aspect of this work was to determine if the effect of HRI inhibition could be increased with another drug added to the mix, Dr Blobel said.

He and his colleagues therefore tested whether pomalidomide, which was previously shown to increase HbF in an experimental setting, could be such a drug.

HRI depletion in combination with pomalidomide treatment raised HbF levels more than either treatment alone, suggesting that HRI inhibition might be combined with another HbF-inducing drug to increase the therapeutic index.

A kinase called heme-regulated inhibitor (HRI) could be a therapeutic target for sickle cell disease (SCD) and some forms of β-thalassemia, according to researchers.

The team found that reducing the activity of HRI (also known as EIF2AK1) can boost the production of fetal hemoglobin (HbF).

Gerd Blobel MD, PhD, of The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania, and his colleagues reported this discovery in Science.

Dr Blobel noted that hydroxyurea remains the only approved drug that can increase fetal Hb in adults.

“Our goal was to identify new potential drug targets that regulate fetal Hb levels,” he said.

To that end, the researchers conducted a CRISPR-Cas9 screen targeting protein kinases. They designed a library of single-guide RNAs targeting 482 kinase domains, which covered almost all known kinases in the human genome.

The team attempted to determine if interference with any of the kinases in an immortalized human red blood cell line would increase HbF levels.

Results suggested that HRI, an erythroid-specific kinase that controls protein translation, is a repressor of HbF.

To confirm that HRI plays a key role in regulating HbF levels, the researchers depleted HRI in primary cultured human red blood cell precursors.

Reduced activity of HRI resulted in decreased phosphorylation of eIF2a and increased levels of HbF, but interfering with HRI levels did not impair cell viability or maturation.

The researchers next showed that HRI was a repressor of HbF in cultured primary cells from patients with SCD.

When HRI levels were artificially reduced, HbF levels were significantly increased, and cells were less prone to sickling. This suggested to the researchers that “HRI depletion may achieve therapeutically relevant levels of HbF.”

Mechanistically, the effects of HRI on HbF were shown to occur, in large measure, through modulating the activity of BCL11A, a direct repressor of HbF transcription.

The observation that HRI inhibition elevated HbF levels and reduced cell sickling in culture suggested that future pharmacologic HRI inhibitors might provide clinical benefit in patients with SCD.

To that end, an important aspect of this work was to determine if the effect of HRI inhibition could be increased with another drug added to the mix, Dr Blobel said.

He and his colleagues therefore tested whether pomalidomide, which was previously shown to increase HbF in an experimental setting, could be such a drug.

HRI depletion in combination with pomalidomide treatment raised HbF levels more than either treatment alone, suggesting that HRI inhibition might be combined with another HbF-inducing drug to increase the therapeutic index.

A kinase called heme-regulated inhibitor (HRI) could be a therapeutic target for sickle cell disease (SCD) and some forms of β-thalassemia, according to researchers.

The team found that reducing the activity of HRI (also known as EIF2AK1) can boost the production of fetal hemoglobin (HbF).

Gerd Blobel MD, PhD, of The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania, and his colleagues reported this discovery in Science.

Dr Blobel noted that hydroxyurea remains the only approved drug that can increase fetal Hb in adults.

“Our goal was to identify new potential drug targets that regulate fetal Hb levels,” he said.

To that end, the researchers conducted a CRISPR-Cas9 screen targeting protein kinases. They designed a library of single-guide RNAs targeting 482 kinase domains, which covered almost all known kinases in the human genome.

The team attempted to determine if interference with any of the kinases in an immortalized human red blood cell line would increase HbF levels.

Results suggested that HRI, an erythroid-specific kinase that controls protein translation, is a repressor of HbF.

To confirm that HRI plays a key role in regulating HbF levels, the researchers depleted HRI in primary cultured human red blood cell precursors.

Reduced activity of HRI resulted in decreased phosphorylation of eIF2a and increased levels of HbF, but interfering with HRI levels did not impair cell viability or maturation.

The researchers next showed that HRI was a repressor of HbF in cultured primary cells from patients with SCD.