User login

RELAPSE: Answers to why a patient is having a new mood episode

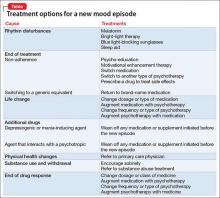

A mood disorder is a chronic illness, associated with episodic recurrence over time1,2; when a patient experiences a new mood episode, explore possible underlying causes of that recurrence. The mnemonic RELAPSE can help you take an informed approach to treatment, instead of making reflexive medication changes (Table).

Rhythm disturbances. Seasonal changes, shift work, jet lag, and sleep irregularity can induce a mood episode in a vulnerable patient. Failure of a patient’s circadian clock to resynchronize itself after such disruption in the dark–light cycle can trigger mood symptoms.

Ending treatment. Intentional or unintentional non-adherence to a prescribed medication or psychotherapy can trigger a mood episode. Likewise, switching from a brand-name medication to a generic equivalent can induce a new episode because the generic drug might be as much as 20% less bioavailable than the brand formulation.3

Life change. Some life events, such as divorce or job loss, can be sufficiently overwhelming—despite medical therapy and psychotherapy—to induce a new episode in a vulnerable patient.

Additional drugs. Opiates, interferon, steroids, reserpine, and other drugs can be depressogenic; on the other hand, steroids, anticholinergic agents, and antidepressants can induce mania. If another physician, or the patient, adds a medication or supplement that causes an interaction with the patient’s current psychotropic prescription, the result might be increased metabolism or clearance of the psychotropic—thus decreasing its efficacy and leading to a new mood episode.

Physical health changes. Neurologic conditions (epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, stroke), autoimmune illnesses (eg, lupus), primary sleep disorders (eg, obstructive sleep apnea), and hormone changes (eg, testosterone, estrogen, and thyroid) that can occur over the lifespan of a patient with a mood disorder can trigger a new episode.

Substance use and withdrawal. Chronic use of alcohol and opiates and withdrawal from cocaine and stimulants in a patient with a mood disorder can induce a depressive episode; use of cocaine, stimulants, and caffeine can induce a manic state.

End of drug response. Some patients experience a loss of drug response over time (tachyphylaxis) or a depressive recurrence while taking an antidepressant.4 These phenomena might be caused by brain changes over time. These are a diagnosis of exclusion after other possibilities have been ruled out.

1. Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, et al. Multiple recurrences of major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:229-233.

2. Perlis RH, Ostacher MJ, Patel JK, et al. Predictors of recurrence in bipolar disorder: primary outcomes from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:217-224.

3. Ellingrod VL. How differences among generics might affect your patient’s response. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(5):31-32,38.

4. Dunlop BW. Depressive recurrence on antidepressant treatment (DRAT): 4 next-step options. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12:54-55.

A mood disorder is a chronic illness, associated with episodic recurrence over time1,2; when a patient experiences a new mood episode, explore possible underlying causes of that recurrence. The mnemonic RELAPSE can help you take an informed approach to treatment, instead of making reflexive medication changes (Table).

Rhythm disturbances. Seasonal changes, shift work, jet lag, and sleep irregularity can induce a mood episode in a vulnerable patient. Failure of a patient’s circadian clock to resynchronize itself after such disruption in the dark–light cycle can trigger mood symptoms.

Ending treatment. Intentional or unintentional non-adherence to a prescribed medication or psychotherapy can trigger a mood episode. Likewise, switching from a brand-name medication to a generic equivalent can induce a new episode because the generic drug might be as much as 20% less bioavailable than the brand formulation.3

Life change. Some life events, such as divorce or job loss, can be sufficiently overwhelming—despite medical therapy and psychotherapy—to induce a new episode in a vulnerable patient.

Additional drugs. Opiates, interferon, steroids, reserpine, and other drugs can be depressogenic; on the other hand, steroids, anticholinergic agents, and antidepressants can induce mania. If another physician, or the patient, adds a medication or supplement that causes an interaction with the patient’s current psychotropic prescription, the result might be increased metabolism or clearance of the psychotropic—thus decreasing its efficacy and leading to a new mood episode.

Physical health changes. Neurologic conditions (epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, stroke), autoimmune illnesses (eg, lupus), primary sleep disorders (eg, obstructive sleep apnea), and hormone changes (eg, testosterone, estrogen, and thyroid) that can occur over the lifespan of a patient with a mood disorder can trigger a new episode.

Substance use and withdrawal. Chronic use of alcohol and opiates and withdrawal from cocaine and stimulants in a patient with a mood disorder can induce a depressive episode; use of cocaine, stimulants, and caffeine can induce a manic state.

End of drug response. Some patients experience a loss of drug response over time (tachyphylaxis) or a depressive recurrence while taking an antidepressant.4 These phenomena might be caused by brain changes over time. These are a diagnosis of exclusion after other possibilities have been ruled out.

A mood disorder is a chronic illness, associated with episodic recurrence over time1,2; when a patient experiences a new mood episode, explore possible underlying causes of that recurrence. The mnemonic RELAPSE can help you take an informed approach to treatment, instead of making reflexive medication changes (Table).

Rhythm disturbances. Seasonal changes, shift work, jet lag, and sleep irregularity can induce a mood episode in a vulnerable patient. Failure of a patient’s circadian clock to resynchronize itself after such disruption in the dark–light cycle can trigger mood symptoms.

Ending treatment. Intentional or unintentional non-adherence to a prescribed medication or psychotherapy can trigger a mood episode. Likewise, switching from a brand-name medication to a generic equivalent can induce a new episode because the generic drug might be as much as 20% less bioavailable than the brand formulation.3

Life change. Some life events, such as divorce or job loss, can be sufficiently overwhelming—despite medical therapy and psychotherapy—to induce a new episode in a vulnerable patient.

Additional drugs. Opiates, interferon, steroids, reserpine, and other drugs can be depressogenic; on the other hand, steroids, anticholinergic agents, and antidepressants can induce mania. If another physician, or the patient, adds a medication or supplement that causes an interaction with the patient’s current psychotropic prescription, the result might be increased metabolism or clearance of the psychotropic—thus decreasing its efficacy and leading to a new mood episode.

Physical health changes. Neurologic conditions (epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, stroke), autoimmune illnesses (eg, lupus), primary sleep disorders (eg, obstructive sleep apnea), and hormone changes (eg, testosterone, estrogen, and thyroid) that can occur over the lifespan of a patient with a mood disorder can trigger a new episode.

Substance use and withdrawal. Chronic use of alcohol and opiates and withdrawal from cocaine and stimulants in a patient with a mood disorder can induce a depressive episode; use of cocaine, stimulants, and caffeine can induce a manic state.

End of drug response. Some patients experience a loss of drug response over time (tachyphylaxis) or a depressive recurrence while taking an antidepressant.4 These phenomena might be caused by brain changes over time. These are a diagnosis of exclusion after other possibilities have been ruled out.

1. Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, et al. Multiple recurrences of major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:229-233.

2. Perlis RH, Ostacher MJ, Patel JK, et al. Predictors of recurrence in bipolar disorder: primary outcomes from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:217-224.

3. Ellingrod VL. How differences among generics might affect your patient’s response. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(5):31-32,38.

4. Dunlop BW. Depressive recurrence on antidepressant treatment (DRAT): 4 next-step options. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12:54-55.

1. Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, et al. Multiple recurrences of major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:229-233.

2. Perlis RH, Ostacher MJ, Patel JK, et al. Predictors of recurrence in bipolar disorder: primary outcomes from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:217-224.

3. Ellingrod VL. How differences among generics might affect your patient’s response. Current Psychiatry. 2010;9(5):31-32,38.

4. Dunlop BW. Depressive recurrence on antidepressant treatment (DRAT): 4 next-step options. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12:54-55.

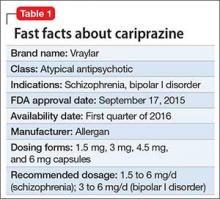

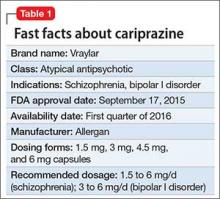

Cariprazine for schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder

Cariprazine is a newly approved (September 2015) dopamine D3/D2 receptor partial agonist with higher affinity for the D3 receptor than for D2. The drug is FDA-indicated for treating schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder (BD I)1,2 (Table 1). In clinical trials, cariprazine alleviated symptoms of schizophrenia and mixed and manic symptoms of BD I, with minimal effect on metabolic parameters, the prolactin level, and cardiac conduction.

Clinical implications

Despite numerous developments in pharmacotherapeutics, people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder continue to struggle with residual symptoms or endure treatments that produce adverse effects (AEs). In particular, metabolic issues, sedation, and cognitive impairment plague many current treatment options for these disorders.

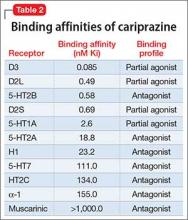

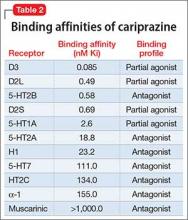

Receptor blocking. As a dopamine D3-preferring D3/D2 partial agonist, cariprazine offers an alternative to antipsychotics that preferentially modulate D2 receptors. First-generation (typical) antipsychotics block D2 receptors; atypical antipsychotics block D2 receptors and 5-HT2A receptors. Dopamine partial agonists aripiprazole and brexpiprazole are D2-preferring, with minimal D3 effects. In contrast, cariprazine has a 6-fold to 8-fold higher affinity for D3 receptors than for D2 receptors, and has specificity for the D3 receptor that is 3 to 10 times higher than what aripiprazole has for the D3 receptor3-5 (Table 2).

Use in schizophrenia. Recommended dosage range is 1.5 to 6 mg/d. In Phase-III clinical trials, dosages of 3 to 9 mg/d produced significant improvement on the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS) and on the Clinical Global Impression scale. Higher dosages (6 to 9 mg/d) showed early separation from placebo—by the end of Week 1—but carried a dosage-related risk of AEs, leading the FDA to recommend 6 mg/d as the maximum dosage.1,6-8

Use in manic or mixed episodes of BD I. Recommended dosage range is 3 to 6 mg/d. In clinical trials, dosages in the range of 3 to 12 mg/d were effective for acute manic or mixed symptoms; significant improvement in the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) score was seen as early as Day 4. Dosages >6 mg/d yielded no additional benefit and were associated with increased risk of AEs.9-12

Pharmacologic profile, adverse effects. Cariprazine has a pharmacologic profile consistent with the generally favorable metabolic profile and lack of anticholinergic effects seen in clinical trials. In short- and long-term trials, the drug had minimal effects on prolactin, blood pressure, and cardiac conduction.13

Across clinical trials for both disorders, akathisia and parkinsonism were among more common AEs of cariprazine. Both AEs were usually mild, resulting in relatively few premature discontinuations from trials. Parkinsonism appeared somewhat dosage-related; akathisia had no clear relationship to dosage.

How it works

The theory behind the use of partial agonists, including cariprazine, is that these agents restore homeostatic balance to neurochemical circuits by:

- decreasing the effects of endogenous neurotransmitters (dopamine tone) in regions of the brain where their transmission is excessive, such as mesolimbic regions in schizophrenia or mania

- simultaneously increasing neurotransmission in regions where transmission of endogenous neurotransmitters is low, such as the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia

- exerting little effect in regions where neurotransmitter activity is normal, such as the pituitary gland.

- simultaneously

Cariprazine has higher binding affinity for dopamine D3 receptors (Ki 0.085 nM) than for D2L receptors (Ki 0.49 nM) and D2S receptors (Ki 0.69 nM). The drug also has strong affinity for serotonin receptor 5-HT2B; moderate affinity for 5-HT1A; and lower affinity for 5-HT2A, histamine H1, and 5-HT7 receptors. Cariprazine has little or no affinity for adrenergic or cholinergic receptors.14In patients with schizophrenia, as measured on PET scanning, a dosage of 1.5 mg/d yielded 69% to 75% D2/D3 receptor occupancy. A dosage of 3 mg/d yielded >90% occupancy.

Search for an understanding of action continues. The relative contribution of D3 partial agonism, compared with D2 partial agonism, is a subject of ongoing basic scientific and clinical research. D3 is an autoreceptor that (1) controls phasic, but not tonic, activity of dopamine nerve cells and (2) mediates behavioral abnormalities induced by glutamate and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists.5,12 In animal studies, D3-preferring agents have been shown to exert pro-cognitive effects and improve anhedonic symptoms.

Pharmacokinetics

Cariprazine is a once-daily medication with a relatively long half-life that can be taken with or without food. Dosages of 3 to 12 mg/d yield a fairly linear, dose-proportional increase in plasma concentration. The peak serum concentration for cariprazine is 3 to 4 hours under fasting conditions; taking the drug with food causes a slight delay in absorption but does not have a significant effect on the area under the curve. Mean half-life for cariprazine is 2 to 5 days over a dosage range of 1.5 to 12.5 mg/d in otherwise healthy adults with schizophrenia.1

Cariprazine is metabolized primarily by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4. It is a weak inhibitor of CYP2D6 and CYP3A4.1 Hepatic metabolism of cariprazine produces 2 active metabolites: desmethyl-cariprazine (DCAR) and didesmethyl-cariprazine (DDCAR), both of which are equipotent to cariprazine. After multiple dose administration, mean cariprazine and DCAR levels reach steady state in 1 to 2 weeks; DDCAR, in 4 to 8 weeks. The systemic exposure and serum levels of DDCAR are roughly 3-fold greater than cariprazine because of the longer elimination half-life of DDCAR.1

Efficacy in schizophrenia

The efficacy of cariprazine in schizophrenia was established by 3 six-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Two trials were fixed-dosage; a third used 2 flexible dosage ranges. The primary efficacy measure was change from baseline in the total score of the PANSS at the end of Week 6, compared with placebo. In all trials, patients were adults (age 18 to 60) who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for schizophrenia and had a PANSS score between 80 and 120 at screening and baseline.

Study 1 (n = 711) compared dosages of 1.5 mg/d, 3 mg/d, and 4.5 mg/d with placebo.7 All cariprazine dosages and an active control (risperdone) were superior to placebo in reducing symptoms of schizophrenia, as measured by the PANSS. The placebo-subtracted differences on PANSS score at 6 weeks for dosages of 1.5 mg/d, 3 mg/d, and 4.5 mg/d were –7.6, –8.8, –10.4, respectively (significant at 95% CI).

Study 2 (n = 151) compared 3 mg/d and 6 mg/d dosages of cariprazine with placebo.1 Both dosages and an active control (aripiprazole) were superior to placebo in reducing PANSS scores. Placebo-subtracted differences on PANSS score at 6 weeks for dosages of 3 mg/d and 6 mg/day were –6.0, –8.8, respectively (significant at 95% CI).

Study 3 (n = 147) was a fixed-flexible dosage trial comparing cariprazine, 3 to 6 mg/d and 6 to 9 mg/d dosage ranges, to placebo.8 Both ranges were superior to placebo in reducing symptoms on PANSS. Placebo-subtracted differences from placebo on PANSS at 6 weeks for cariprazine 3 to 6 or 6 to 9 mg/d were –6.8, –9.9, respectively (significant at 95% CI).

These trials established the efficacy of cariprazine for acute schizophrenia at dosages ranging from 1.5 to 9 mg/d. Although there was a modest trend toward higher efficacy at higher dosages, there was a dose-related increase in certain adverse reactions (extrapyramidal symptoms [EPS]) at dosages >6 mg/d.1

Efficacy in bipolar disorder

The efficacy of cariprazine for acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes of BD I was established in 3 randomized, placebo-controlled, flexibly dosed 3-week trials. In all trials, patients were adults (age 18 to 65) who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for BD I with manic or mixed episodes and with or without psychotic features (YMRS score, ≥20). The primary efficacy measure in the 3 trials was a change from baseline in the total YMRS score at the end of Week 3, compared with placebo.

Study 1 (n = 492) compared 2 flexibly dosed ranges of cariprazine (3 to 6 mg/d and 6 to 12 mg/d) with placebo.10 Both dosage ranges were superior to placebo in reducing mixed and manic symptoms, as measured by reduction in the total YMRS score. Placebo-subtracted differences in YMRS scores from placebo at Week 3 for cariprazine 3 to 6 mg/d and 6 to 12 mg/d were –6.1, –5.9, respectively (significant at 95% CI). The higher range offered no additional advantage over the lower range.

Study 2 (n = 235) compared flexibly dosed cariprazine, 3 to 12 mg/d, to placebo.11 Cariprazine was superior to placebo in reducing bipolar symptoms as measured by the YMRS. The difference between cariprazine 3 to 12 mg/d and placebo on the YMRS score at Week 3 was –6.1 (significant at 95% CI).

Study 3 (n = 310) compared flexibly dosed cariprazine, 3 to 12 mg/d, with placebo.15 Again, cariprazine was superior to placebo in reducing the YMRS score at Week 3: difference, –4.3 (significant at 95% CI).

These trials establish the efficacy of cariprazine in treating acute mania or mixed BD I episodes at dosages ranging from 3 to 12 mg/d. Dosages >6 mg/d did not offer additional benefit over lower dosages, and resulted in a dosage-related increase in EPS at dosages >6 mg/d.16

Tolerability

Cariprazine generally was well tolerated in short-term trials for schizophrenia and BD I. The only treatment-emergent adverse event reported for at least 1 treatment group in all trials at a rate of ≥10%, and at least twice the rate seen with placebo was akathisia. Adverse events reported at a lower rate than placebo included EPS (particularly parkinsonism), restlessness, headache, insomnia, fatigue, and gastrointestinal distress. The discontinuation rate due to AEs for treatment groups and placebo-treated patients generally was similar. In schizophrenia Study 3, for example, the discontinuation rate due to AEs was 13% for placebo; 14% for cariprazine, 3 to 6 mg/d; and 13% for cariprazine, 6 to 9 mg/d.1 48-Week open-label safety study. Patients with schizophrenia received open-label cariprazine for as long as 48 weeks.7 Serious adverse events were reported in 12.9%, including 1 death (suicide); exacerbation of symptoms of schizophrenia (4.3%); and psychosis (2.2%). Treatment-emergent adverse events reported in at least 10% of patients included akathisia (14.0%), insomnia (14.0%), and weight gain (11.8%). The mean change in laboratory values, blood pressure, pulse rate, and electrocardiographic parameters was clinically insignificant.

Other studies. In a 16-week, open-label extension study of patients with BD I, the major tolerability issue was akathisia. This AE developed in 37% of patients and led to a 5% withdrawal rate.12

In short- and long-term studies for either indication, the effect of the drug on metabolic parameters appears to be small. In studies with active controls, potentially significant weight gain (>7%) was greater for aripiprazole and risperidone than for cariprazine.6,7 The effect on the prolactin level was minimal. There do not appear to be clinically meaningful changes in laboratory values, vital signs, or QT interval.

Unique clinical issues

Preferential binding. Cariprazine is the third dopamine partial agonist approved for use in the United States; unlike the other 2—aripiprazole and brexpiprazole—cariprazine shows preference for D3 receptors over D2 receptors. The exact clinical impact of a preference for D3 and the drug’s partial agonism of 5-HT1A has not been fully elucidated.

EPS, including akathisia and parkinsonism, were among common adverse events. Both were usually mild, with 0.5% of schizophrenia patients and 2% of BD I patients dropping out of trials because of any type of EPS-related AEs.

Why Rx? On a practical medical level, reasons to prescribe cariprazine likely include:

- minimal effect on prolactin

- relative lack of effect on metabolic parameters, including weight (cariprazine showed less weight gain than risperidone or aripiprazole control arms in trials).

Dosing

The recommended dosage of cariprazine for schizophrenia ranges from 1.5 to 6 mg/d. The recommended starting dosage is 1.5 mg/d, which can be increased to 3 mg on Day 2, with further upward dosage adjustments of 1.5 to 3 mg/d, based on clinical response and tolerability.1

The recommended dosages of cariprazine for mixed and manic episodes of BD I range from 3 to 6 mg/d. The recommended starting dosage is 1.5 mg/d, which can be increased to 3 mg on Day 2, with further upward dosage adjustments of 1.5 to 3 mg/d, based on clinical response and tolerability.1

Other key aspects of dosing to keep in mind:

- Because of the long half-life and 2 equipotent active metabolites of cariprazine, any changes made to the dosage will not be reflected fully in the serum level for 2 weeks.

- Administering the drug with food slightly delays, but does not affect, the extent of absorption.

- Because the drug is metabolized primarily by CYP3A4, dosage adjustment is required in the presence of a CYP3A4 inhibitor; the recommended starting dosage of cariprazine is 1.5 mg every other day with a maximum dosage of 3 mg/d when it is administered concomitantly with a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor.

- Because data are not available regarding concomitant use of cariprazine with a strong CYP3A4 inducer, this practice is not recommended.1

- Because the drug is metabolized primarily by CYP3A4, dosage adjustment is required in the presence of a CYP3A4 Because data are not available regarding concomitant use of cariprazine with a strong CYP3A4

Contraindications

Cariprazine carries a FDA black-box warning of increased mortality in older patients who have dementia-related psychosis, as other atypical antipsychotics do. Clinical trials produced few data about the use of cariprazine in geriatric patients; no data exist about use in the pediatric population.1

Metabolic, prolactin, and cardiac concerns about cariprazine appeared favorably minor in Phase-III and long-term safety trials. Concomitant use of cariprazine with any strong inducer of CYP3A4 has not been studied, and is not recommended. Dosage reduction is recommended when using cariprazine concomitantly with a CYP3A4 inhibitor.1

In conclusion

The puzzle in neuropsychiatry has always been to find ways to produce different effects in different brain regions—with a single drug. Cariprazine’s particular binding profile—higher affinity and higher selectivity for D3 receptors than for D2 receptors compared with either aripiprazole or brexpiprazole—may secure a role for it in managing psychosis and mood disorders.

1. Vraylar [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ: Actavis Pharma, Inc.; 2015.

2. McCormack PL, Cariprazine: first global approval. Drugs. 2015;75(17):2035-2043.

3. Kiss B, Horváth A, Némethy Z, et al. Cariprazine (RGH-188), a dopamine D(3) receptor-preferring, D(3)/D(2) dopamine receptor antagonist-partial agonist antipsychotic candidate: in vitro and neurochemical profile. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;333(1):328-340.

4. Potkin, S, Keator, D, Mukherjee J, et al. P. 1. E 028 dopamine D3 and D2 receptor occupancy of cariprazine in schizophrenic patients. Eur Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;19(suppl 3):S316.

5. Veselinovicˇ T, Paulzen M, Gründer G. Cariprazine, a new, orally active dopamine D2/3 receptor partial agonist for the treatment of schizophrenia, bipolar mania and depression. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13(11):1141-1159.

6. Cutler A, Mokliatchouk O, Laszlovszky I, et al. Cariprazine in acute schizophrenia: a fixed-dose phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled trial. Abstract presented at: 166th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; May 18-22, 2013; San Francisco, CA.

7. Durgam S, Starace A, Li D, et al. An evaluation of the safety and efficacy of cariprazine in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: a phase II, randomized clinical trial. Schizophr Res. 2014;152(2-3):450-457.

8. Kane JM, Zukin S, Wang Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of cariprazine in acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: results from an international, phase III clinical trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;35(4):367-373.

9. Bose A, Starace A, Lu, K, et al. Cariprazine in the treatment of acute mania in bipolar disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. Poster presented at: 16th Annual Meeting of the College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists; April 21-24, 2013; Colorado Springs, CO.

10. Calabrese JR, Keck PE Jr, Starace A, et al. Efficacy and safety of low- and high-dose cariprazine in acute and mixed mania associated with bipolar I disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(3):284-292.

11. Durgam S, Starace A, Li D, et al. The efficacy and tolerability of cariprazine in acute mania associated with bipolar I disorder: a phase II trial. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17(1):63-75.

12. Ketter, T. A phase III, open-label, 16-week study of flexibly dosed cariprazine in 402 patients with bipolar I disorder. Presented at: 53rd Annual Meeting of the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit; May 28-31, 2013; Hollywood, FL.

13. Bose A, Li D, Migliore R. The efficacy and safety of the novel antipsychotic cariprazine in the acute exacerbation of schizophrenia. Poster presented at: 50th Annual Meeting of the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit; June 14-17, 2010; Boca Raton, FL.

14. Citrome L. Cariprazine: chemistry, pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, and metabolism, clinical efficacy, safety, and tolerability. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2013;9(2):193-206.

15. Sachs GS, Greenberg WM, Starace A, et al. Cariprazine in the treatment of acute mania in bipolar I disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:296-302.

16. Vieta E, Durgam S, Lu K, et al. Effect of cariprazine across the symptoms of mania in bipolar I disorder: analyses of pooled data from phase II/III trials. Eur Neuropsycholpharmacol. 2015;25(11):1882-1891.

Cariprazine is a newly approved (September 2015) dopamine D3/D2 receptor partial agonist with higher affinity for the D3 receptor than for D2. The drug is FDA-indicated for treating schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder (BD I)1,2 (Table 1). In clinical trials, cariprazine alleviated symptoms of schizophrenia and mixed and manic symptoms of BD I, with minimal effect on metabolic parameters, the prolactin level, and cardiac conduction.

Clinical implications

Despite numerous developments in pharmacotherapeutics, people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder continue to struggle with residual symptoms or endure treatments that produce adverse effects (AEs). In particular, metabolic issues, sedation, and cognitive impairment plague many current treatment options for these disorders.

Receptor blocking. As a dopamine D3-preferring D3/D2 partial agonist, cariprazine offers an alternative to antipsychotics that preferentially modulate D2 receptors. First-generation (typical) antipsychotics block D2 receptors; atypical antipsychotics block D2 receptors and 5-HT2A receptors. Dopamine partial agonists aripiprazole and brexpiprazole are D2-preferring, with minimal D3 effects. In contrast, cariprazine has a 6-fold to 8-fold higher affinity for D3 receptors than for D2 receptors, and has specificity for the D3 receptor that is 3 to 10 times higher than what aripiprazole has for the D3 receptor3-5 (Table 2).

Use in schizophrenia. Recommended dosage range is 1.5 to 6 mg/d. In Phase-III clinical trials, dosages of 3 to 9 mg/d produced significant improvement on the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS) and on the Clinical Global Impression scale. Higher dosages (6 to 9 mg/d) showed early separation from placebo—by the end of Week 1—but carried a dosage-related risk of AEs, leading the FDA to recommend 6 mg/d as the maximum dosage.1,6-8

Use in manic or mixed episodes of BD I. Recommended dosage range is 3 to 6 mg/d. In clinical trials, dosages in the range of 3 to 12 mg/d were effective for acute manic or mixed symptoms; significant improvement in the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) score was seen as early as Day 4. Dosages >6 mg/d yielded no additional benefit and were associated with increased risk of AEs.9-12

Pharmacologic profile, adverse effects. Cariprazine has a pharmacologic profile consistent with the generally favorable metabolic profile and lack of anticholinergic effects seen in clinical trials. In short- and long-term trials, the drug had minimal effects on prolactin, blood pressure, and cardiac conduction.13

Across clinical trials for both disorders, akathisia and parkinsonism were among more common AEs of cariprazine. Both AEs were usually mild, resulting in relatively few premature discontinuations from trials. Parkinsonism appeared somewhat dosage-related; akathisia had no clear relationship to dosage.

How it works

The theory behind the use of partial agonists, including cariprazine, is that these agents restore homeostatic balance to neurochemical circuits by:

- decreasing the effects of endogenous neurotransmitters (dopamine tone) in regions of the brain where their transmission is excessive, such as mesolimbic regions in schizophrenia or mania

- simultaneously increasing neurotransmission in regions where transmission of endogenous neurotransmitters is low, such as the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia

- exerting little effect in regions where neurotransmitter activity is normal, such as the pituitary gland.

- simultaneously

Cariprazine has higher binding affinity for dopamine D3 receptors (Ki 0.085 nM) than for D2L receptors (Ki 0.49 nM) and D2S receptors (Ki 0.69 nM). The drug also has strong affinity for serotonin receptor 5-HT2B; moderate affinity for 5-HT1A; and lower affinity for 5-HT2A, histamine H1, and 5-HT7 receptors. Cariprazine has little or no affinity for adrenergic or cholinergic receptors.14In patients with schizophrenia, as measured on PET scanning, a dosage of 1.5 mg/d yielded 69% to 75% D2/D3 receptor occupancy. A dosage of 3 mg/d yielded >90% occupancy.

Search for an understanding of action continues. The relative contribution of D3 partial agonism, compared with D2 partial agonism, is a subject of ongoing basic scientific and clinical research. D3 is an autoreceptor that (1) controls phasic, but not tonic, activity of dopamine nerve cells and (2) mediates behavioral abnormalities induced by glutamate and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists.5,12 In animal studies, D3-preferring agents have been shown to exert pro-cognitive effects and improve anhedonic symptoms.

Pharmacokinetics

Cariprazine is a once-daily medication with a relatively long half-life that can be taken with or without food. Dosages of 3 to 12 mg/d yield a fairly linear, dose-proportional increase in plasma concentration. The peak serum concentration for cariprazine is 3 to 4 hours under fasting conditions; taking the drug with food causes a slight delay in absorption but does not have a significant effect on the area under the curve. Mean half-life for cariprazine is 2 to 5 days over a dosage range of 1.5 to 12.5 mg/d in otherwise healthy adults with schizophrenia.1

Cariprazine is metabolized primarily by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4. It is a weak inhibitor of CYP2D6 and CYP3A4.1 Hepatic metabolism of cariprazine produces 2 active metabolites: desmethyl-cariprazine (DCAR) and didesmethyl-cariprazine (DDCAR), both of which are equipotent to cariprazine. After multiple dose administration, mean cariprazine and DCAR levels reach steady state in 1 to 2 weeks; DDCAR, in 4 to 8 weeks. The systemic exposure and serum levels of DDCAR are roughly 3-fold greater than cariprazine because of the longer elimination half-life of DDCAR.1

Efficacy in schizophrenia

The efficacy of cariprazine in schizophrenia was established by 3 six-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Two trials were fixed-dosage; a third used 2 flexible dosage ranges. The primary efficacy measure was change from baseline in the total score of the PANSS at the end of Week 6, compared with placebo. In all trials, patients were adults (age 18 to 60) who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for schizophrenia and had a PANSS score between 80 and 120 at screening and baseline.

Study 1 (n = 711) compared dosages of 1.5 mg/d, 3 mg/d, and 4.5 mg/d with placebo.7 All cariprazine dosages and an active control (risperdone) were superior to placebo in reducing symptoms of schizophrenia, as measured by the PANSS. The placebo-subtracted differences on PANSS score at 6 weeks for dosages of 1.5 mg/d, 3 mg/d, and 4.5 mg/d were –7.6, –8.8, –10.4, respectively (significant at 95% CI).

Study 2 (n = 151) compared 3 mg/d and 6 mg/d dosages of cariprazine with placebo.1 Both dosages and an active control (aripiprazole) were superior to placebo in reducing PANSS scores. Placebo-subtracted differences on PANSS score at 6 weeks for dosages of 3 mg/d and 6 mg/day were –6.0, –8.8, respectively (significant at 95% CI).

Study 3 (n = 147) was a fixed-flexible dosage trial comparing cariprazine, 3 to 6 mg/d and 6 to 9 mg/d dosage ranges, to placebo.8 Both ranges were superior to placebo in reducing symptoms on PANSS. Placebo-subtracted differences from placebo on PANSS at 6 weeks for cariprazine 3 to 6 or 6 to 9 mg/d were –6.8, –9.9, respectively (significant at 95% CI).

These trials established the efficacy of cariprazine for acute schizophrenia at dosages ranging from 1.5 to 9 mg/d. Although there was a modest trend toward higher efficacy at higher dosages, there was a dose-related increase in certain adverse reactions (extrapyramidal symptoms [EPS]) at dosages >6 mg/d.1

Efficacy in bipolar disorder

The efficacy of cariprazine for acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes of BD I was established in 3 randomized, placebo-controlled, flexibly dosed 3-week trials. In all trials, patients were adults (age 18 to 65) who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for BD I with manic or mixed episodes and with or without psychotic features (YMRS score, ≥20). The primary efficacy measure in the 3 trials was a change from baseline in the total YMRS score at the end of Week 3, compared with placebo.

Study 1 (n = 492) compared 2 flexibly dosed ranges of cariprazine (3 to 6 mg/d and 6 to 12 mg/d) with placebo.10 Both dosage ranges were superior to placebo in reducing mixed and manic symptoms, as measured by reduction in the total YMRS score. Placebo-subtracted differences in YMRS scores from placebo at Week 3 for cariprazine 3 to 6 mg/d and 6 to 12 mg/d were –6.1, –5.9, respectively (significant at 95% CI). The higher range offered no additional advantage over the lower range.

Study 2 (n = 235) compared flexibly dosed cariprazine, 3 to 12 mg/d, to placebo.11 Cariprazine was superior to placebo in reducing bipolar symptoms as measured by the YMRS. The difference between cariprazine 3 to 12 mg/d and placebo on the YMRS score at Week 3 was –6.1 (significant at 95% CI).

Study 3 (n = 310) compared flexibly dosed cariprazine, 3 to 12 mg/d, with placebo.15 Again, cariprazine was superior to placebo in reducing the YMRS score at Week 3: difference, –4.3 (significant at 95% CI).

These trials establish the efficacy of cariprazine in treating acute mania or mixed BD I episodes at dosages ranging from 3 to 12 mg/d. Dosages >6 mg/d did not offer additional benefit over lower dosages, and resulted in a dosage-related increase in EPS at dosages >6 mg/d.16

Tolerability

Cariprazine generally was well tolerated in short-term trials for schizophrenia and BD I. The only treatment-emergent adverse event reported for at least 1 treatment group in all trials at a rate of ≥10%, and at least twice the rate seen with placebo was akathisia. Adverse events reported at a lower rate than placebo included EPS (particularly parkinsonism), restlessness, headache, insomnia, fatigue, and gastrointestinal distress. The discontinuation rate due to AEs for treatment groups and placebo-treated patients generally was similar. In schizophrenia Study 3, for example, the discontinuation rate due to AEs was 13% for placebo; 14% for cariprazine, 3 to 6 mg/d; and 13% for cariprazine, 6 to 9 mg/d.1 48-Week open-label safety study. Patients with schizophrenia received open-label cariprazine for as long as 48 weeks.7 Serious adverse events were reported in 12.9%, including 1 death (suicide); exacerbation of symptoms of schizophrenia (4.3%); and psychosis (2.2%). Treatment-emergent adverse events reported in at least 10% of patients included akathisia (14.0%), insomnia (14.0%), and weight gain (11.8%). The mean change in laboratory values, blood pressure, pulse rate, and electrocardiographic parameters was clinically insignificant.

Other studies. In a 16-week, open-label extension study of patients with BD I, the major tolerability issue was akathisia. This AE developed in 37% of patients and led to a 5% withdrawal rate.12

In short- and long-term studies for either indication, the effect of the drug on metabolic parameters appears to be small. In studies with active controls, potentially significant weight gain (>7%) was greater for aripiprazole and risperidone than for cariprazine.6,7 The effect on the prolactin level was minimal. There do not appear to be clinically meaningful changes in laboratory values, vital signs, or QT interval.

Unique clinical issues

Preferential binding. Cariprazine is the third dopamine partial agonist approved for use in the United States; unlike the other 2—aripiprazole and brexpiprazole—cariprazine shows preference for D3 receptors over D2 receptors. The exact clinical impact of a preference for D3 and the drug’s partial agonism of 5-HT1A has not been fully elucidated.

EPS, including akathisia and parkinsonism, were among common adverse events. Both were usually mild, with 0.5% of schizophrenia patients and 2% of BD I patients dropping out of trials because of any type of EPS-related AEs.

Why Rx? On a practical medical level, reasons to prescribe cariprazine likely include:

- minimal effect on prolactin

- relative lack of effect on metabolic parameters, including weight (cariprazine showed less weight gain than risperidone or aripiprazole control arms in trials).

Dosing

The recommended dosage of cariprazine for schizophrenia ranges from 1.5 to 6 mg/d. The recommended starting dosage is 1.5 mg/d, which can be increased to 3 mg on Day 2, with further upward dosage adjustments of 1.5 to 3 mg/d, based on clinical response and tolerability.1

The recommended dosages of cariprazine for mixed and manic episodes of BD I range from 3 to 6 mg/d. The recommended starting dosage is 1.5 mg/d, which can be increased to 3 mg on Day 2, with further upward dosage adjustments of 1.5 to 3 mg/d, based on clinical response and tolerability.1

Other key aspects of dosing to keep in mind:

- Because of the long half-life and 2 equipotent active metabolites of cariprazine, any changes made to the dosage will not be reflected fully in the serum level for 2 weeks.

- Administering the drug with food slightly delays, but does not affect, the extent of absorption.

- Because the drug is metabolized primarily by CYP3A4, dosage adjustment is required in the presence of a CYP3A4 inhibitor; the recommended starting dosage of cariprazine is 1.5 mg every other day with a maximum dosage of 3 mg/d when it is administered concomitantly with a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor.

- Because data are not available regarding concomitant use of cariprazine with a strong CYP3A4 inducer, this practice is not recommended.1

- Because the drug is metabolized primarily by CYP3A4, dosage adjustment is required in the presence of a CYP3A4 Because data are not available regarding concomitant use of cariprazine with a strong CYP3A4

Contraindications

Cariprazine carries a FDA black-box warning of increased mortality in older patients who have dementia-related psychosis, as other atypical antipsychotics do. Clinical trials produced few data about the use of cariprazine in geriatric patients; no data exist about use in the pediatric population.1

Metabolic, prolactin, and cardiac concerns about cariprazine appeared favorably minor in Phase-III and long-term safety trials. Concomitant use of cariprazine with any strong inducer of CYP3A4 has not been studied, and is not recommended. Dosage reduction is recommended when using cariprazine concomitantly with a CYP3A4 inhibitor.1

In conclusion

The puzzle in neuropsychiatry has always been to find ways to produce different effects in different brain regions—with a single drug. Cariprazine’s particular binding profile—higher affinity and higher selectivity for D3 receptors than for D2 receptors compared with either aripiprazole or brexpiprazole—may secure a role for it in managing psychosis and mood disorders.

Cariprazine is a newly approved (September 2015) dopamine D3/D2 receptor partial agonist with higher affinity for the D3 receptor than for D2. The drug is FDA-indicated for treating schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder (BD I)1,2 (Table 1). In clinical trials, cariprazine alleviated symptoms of schizophrenia and mixed and manic symptoms of BD I, with minimal effect on metabolic parameters, the prolactin level, and cardiac conduction.

Clinical implications

Despite numerous developments in pharmacotherapeutics, people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder continue to struggle with residual symptoms or endure treatments that produce adverse effects (AEs). In particular, metabolic issues, sedation, and cognitive impairment plague many current treatment options for these disorders.

Receptor blocking. As a dopamine D3-preferring D3/D2 partial agonist, cariprazine offers an alternative to antipsychotics that preferentially modulate D2 receptors. First-generation (typical) antipsychotics block D2 receptors; atypical antipsychotics block D2 receptors and 5-HT2A receptors. Dopamine partial agonists aripiprazole and brexpiprazole are D2-preferring, with minimal D3 effects. In contrast, cariprazine has a 6-fold to 8-fold higher affinity for D3 receptors than for D2 receptors, and has specificity for the D3 receptor that is 3 to 10 times higher than what aripiprazole has for the D3 receptor3-5 (Table 2).

Use in schizophrenia. Recommended dosage range is 1.5 to 6 mg/d. In Phase-III clinical trials, dosages of 3 to 9 mg/d produced significant improvement on the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS) and on the Clinical Global Impression scale. Higher dosages (6 to 9 mg/d) showed early separation from placebo—by the end of Week 1—but carried a dosage-related risk of AEs, leading the FDA to recommend 6 mg/d as the maximum dosage.1,6-8

Use in manic or mixed episodes of BD I. Recommended dosage range is 3 to 6 mg/d. In clinical trials, dosages in the range of 3 to 12 mg/d were effective for acute manic or mixed symptoms; significant improvement in the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) score was seen as early as Day 4. Dosages >6 mg/d yielded no additional benefit and were associated with increased risk of AEs.9-12

Pharmacologic profile, adverse effects. Cariprazine has a pharmacologic profile consistent with the generally favorable metabolic profile and lack of anticholinergic effects seen in clinical trials. In short- and long-term trials, the drug had minimal effects on prolactin, blood pressure, and cardiac conduction.13

Across clinical trials for both disorders, akathisia and parkinsonism were among more common AEs of cariprazine. Both AEs were usually mild, resulting in relatively few premature discontinuations from trials. Parkinsonism appeared somewhat dosage-related; akathisia had no clear relationship to dosage.

How it works

The theory behind the use of partial agonists, including cariprazine, is that these agents restore homeostatic balance to neurochemical circuits by:

- decreasing the effects of endogenous neurotransmitters (dopamine tone) in regions of the brain where their transmission is excessive, such as mesolimbic regions in schizophrenia or mania

- simultaneously increasing neurotransmission in regions where transmission of endogenous neurotransmitters is low, such as the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia

- exerting little effect in regions where neurotransmitter activity is normal, such as the pituitary gland.

- simultaneously

Cariprazine has higher binding affinity for dopamine D3 receptors (Ki 0.085 nM) than for D2L receptors (Ki 0.49 nM) and D2S receptors (Ki 0.69 nM). The drug also has strong affinity for serotonin receptor 5-HT2B; moderate affinity for 5-HT1A; and lower affinity for 5-HT2A, histamine H1, and 5-HT7 receptors. Cariprazine has little or no affinity for adrenergic or cholinergic receptors.14In patients with schizophrenia, as measured on PET scanning, a dosage of 1.5 mg/d yielded 69% to 75% D2/D3 receptor occupancy. A dosage of 3 mg/d yielded >90% occupancy.

Search for an understanding of action continues. The relative contribution of D3 partial agonism, compared with D2 partial agonism, is a subject of ongoing basic scientific and clinical research. D3 is an autoreceptor that (1) controls phasic, but not tonic, activity of dopamine nerve cells and (2) mediates behavioral abnormalities induced by glutamate and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists.5,12 In animal studies, D3-preferring agents have been shown to exert pro-cognitive effects and improve anhedonic symptoms.

Pharmacokinetics

Cariprazine is a once-daily medication with a relatively long half-life that can be taken with or without food. Dosages of 3 to 12 mg/d yield a fairly linear, dose-proportional increase in plasma concentration. The peak serum concentration for cariprazine is 3 to 4 hours under fasting conditions; taking the drug with food causes a slight delay in absorption but does not have a significant effect on the area under the curve. Mean half-life for cariprazine is 2 to 5 days over a dosage range of 1.5 to 12.5 mg/d in otherwise healthy adults with schizophrenia.1

Cariprazine is metabolized primarily by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4. It is a weak inhibitor of CYP2D6 and CYP3A4.1 Hepatic metabolism of cariprazine produces 2 active metabolites: desmethyl-cariprazine (DCAR) and didesmethyl-cariprazine (DDCAR), both of which are equipotent to cariprazine. After multiple dose administration, mean cariprazine and DCAR levels reach steady state in 1 to 2 weeks; DDCAR, in 4 to 8 weeks. The systemic exposure and serum levels of DDCAR are roughly 3-fold greater than cariprazine because of the longer elimination half-life of DDCAR.1

Efficacy in schizophrenia

The efficacy of cariprazine in schizophrenia was established by 3 six-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Two trials were fixed-dosage; a third used 2 flexible dosage ranges. The primary efficacy measure was change from baseline in the total score of the PANSS at the end of Week 6, compared with placebo. In all trials, patients were adults (age 18 to 60) who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for schizophrenia and had a PANSS score between 80 and 120 at screening and baseline.

Study 1 (n = 711) compared dosages of 1.5 mg/d, 3 mg/d, and 4.5 mg/d with placebo.7 All cariprazine dosages and an active control (risperdone) were superior to placebo in reducing symptoms of schizophrenia, as measured by the PANSS. The placebo-subtracted differences on PANSS score at 6 weeks for dosages of 1.5 mg/d, 3 mg/d, and 4.5 mg/d were –7.6, –8.8, –10.4, respectively (significant at 95% CI).

Study 2 (n = 151) compared 3 mg/d and 6 mg/d dosages of cariprazine with placebo.1 Both dosages and an active control (aripiprazole) were superior to placebo in reducing PANSS scores. Placebo-subtracted differences on PANSS score at 6 weeks for dosages of 3 mg/d and 6 mg/day were –6.0, –8.8, respectively (significant at 95% CI).

Study 3 (n = 147) was a fixed-flexible dosage trial comparing cariprazine, 3 to 6 mg/d and 6 to 9 mg/d dosage ranges, to placebo.8 Both ranges were superior to placebo in reducing symptoms on PANSS. Placebo-subtracted differences from placebo on PANSS at 6 weeks for cariprazine 3 to 6 or 6 to 9 mg/d were –6.8, –9.9, respectively (significant at 95% CI).

These trials established the efficacy of cariprazine for acute schizophrenia at dosages ranging from 1.5 to 9 mg/d. Although there was a modest trend toward higher efficacy at higher dosages, there was a dose-related increase in certain adverse reactions (extrapyramidal symptoms [EPS]) at dosages >6 mg/d.1

Efficacy in bipolar disorder

The efficacy of cariprazine for acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes of BD I was established in 3 randomized, placebo-controlled, flexibly dosed 3-week trials. In all trials, patients were adults (age 18 to 65) who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for BD I with manic or mixed episodes and with or without psychotic features (YMRS score, ≥20). The primary efficacy measure in the 3 trials was a change from baseline in the total YMRS score at the end of Week 3, compared with placebo.

Study 1 (n = 492) compared 2 flexibly dosed ranges of cariprazine (3 to 6 mg/d and 6 to 12 mg/d) with placebo.10 Both dosage ranges were superior to placebo in reducing mixed and manic symptoms, as measured by reduction in the total YMRS score. Placebo-subtracted differences in YMRS scores from placebo at Week 3 for cariprazine 3 to 6 mg/d and 6 to 12 mg/d were –6.1, –5.9, respectively (significant at 95% CI). The higher range offered no additional advantage over the lower range.

Study 2 (n = 235) compared flexibly dosed cariprazine, 3 to 12 mg/d, to placebo.11 Cariprazine was superior to placebo in reducing bipolar symptoms as measured by the YMRS. The difference between cariprazine 3 to 12 mg/d and placebo on the YMRS score at Week 3 was –6.1 (significant at 95% CI).

Study 3 (n = 310) compared flexibly dosed cariprazine, 3 to 12 mg/d, with placebo.15 Again, cariprazine was superior to placebo in reducing the YMRS score at Week 3: difference, –4.3 (significant at 95% CI).

These trials establish the efficacy of cariprazine in treating acute mania or mixed BD I episodes at dosages ranging from 3 to 12 mg/d. Dosages >6 mg/d did not offer additional benefit over lower dosages, and resulted in a dosage-related increase in EPS at dosages >6 mg/d.16

Tolerability

Cariprazine generally was well tolerated in short-term trials for schizophrenia and BD I. The only treatment-emergent adverse event reported for at least 1 treatment group in all trials at a rate of ≥10%, and at least twice the rate seen with placebo was akathisia. Adverse events reported at a lower rate than placebo included EPS (particularly parkinsonism), restlessness, headache, insomnia, fatigue, and gastrointestinal distress. The discontinuation rate due to AEs for treatment groups and placebo-treated patients generally was similar. In schizophrenia Study 3, for example, the discontinuation rate due to AEs was 13% for placebo; 14% for cariprazine, 3 to 6 mg/d; and 13% for cariprazine, 6 to 9 mg/d.1 48-Week open-label safety study. Patients with schizophrenia received open-label cariprazine for as long as 48 weeks.7 Serious adverse events were reported in 12.9%, including 1 death (suicide); exacerbation of symptoms of schizophrenia (4.3%); and psychosis (2.2%). Treatment-emergent adverse events reported in at least 10% of patients included akathisia (14.0%), insomnia (14.0%), and weight gain (11.8%). The mean change in laboratory values, blood pressure, pulse rate, and electrocardiographic parameters was clinically insignificant.

Other studies. In a 16-week, open-label extension study of patients with BD I, the major tolerability issue was akathisia. This AE developed in 37% of patients and led to a 5% withdrawal rate.12

In short- and long-term studies for either indication, the effect of the drug on metabolic parameters appears to be small. In studies with active controls, potentially significant weight gain (>7%) was greater for aripiprazole and risperidone than for cariprazine.6,7 The effect on the prolactin level was minimal. There do not appear to be clinically meaningful changes in laboratory values, vital signs, or QT interval.

Unique clinical issues

Preferential binding. Cariprazine is the third dopamine partial agonist approved for use in the United States; unlike the other 2—aripiprazole and brexpiprazole—cariprazine shows preference for D3 receptors over D2 receptors. The exact clinical impact of a preference for D3 and the drug’s partial agonism of 5-HT1A has not been fully elucidated.

EPS, including akathisia and parkinsonism, were among common adverse events. Both were usually mild, with 0.5% of schizophrenia patients and 2% of BD I patients dropping out of trials because of any type of EPS-related AEs.

Why Rx? On a practical medical level, reasons to prescribe cariprazine likely include:

- minimal effect on prolactin

- relative lack of effect on metabolic parameters, including weight (cariprazine showed less weight gain than risperidone or aripiprazole control arms in trials).

Dosing

The recommended dosage of cariprazine for schizophrenia ranges from 1.5 to 6 mg/d. The recommended starting dosage is 1.5 mg/d, which can be increased to 3 mg on Day 2, with further upward dosage adjustments of 1.5 to 3 mg/d, based on clinical response and tolerability.1

The recommended dosages of cariprazine for mixed and manic episodes of BD I range from 3 to 6 mg/d. The recommended starting dosage is 1.5 mg/d, which can be increased to 3 mg on Day 2, with further upward dosage adjustments of 1.5 to 3 mg/d, based on clinical response and tolerability.1

Other key aspects of dosing to keep in mind:

- Because of the long half-life and 2 equipotent active metabolites of cariprazine, any changes made to the dosage will not be reflected fully in the serum level for 2 weeks.

- Administering the drug with food slightly delays, but does not affect, the extent of absorption.

- Because the drug is metabolized primarily by CYP3A4, dosage adjustment is required in the presence of a CYP3A4 inhibitor; the recommended starting dosage of cariprazine is 1.5 mg every other day with a maximum dosage of 3 mg/d when it is administered concomitantly with a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor.

- Because data are not available regarding concomitant use of cariprazine with a strong CYP3A4 inducer, this practice is not recommended.1

- Because the drug is metabolized primarily by CYP3A4, dosage adjustment is required in the presence of a CYP3A4 Because data are not available regarding concomitant use of cariprazine with a strong CYP3A4

Contraindications

Cariprazine carries a FDA black-box warning of increased mortality in older patients who have dementia-related psychosis, as other atypical antipsychotics do. Clinical trials produced few data about the use of cariprazine in geriatric patients; no data exist about use in the pediatric population.1

Metabolic, prolactin, and cardiac concerns about cariprazine appeared favorably minor in Phase-III and long-term safety trials. Concomitant use of cariprazine with any strong inducer of CYP3A4 has not been studied, and is not recommended. Dosage reduction is recommended when using cariprazine concomitantly with a CYP3A4 inhibitor.1

In conclusion

The puzzle in neuropsychiatry has always been to find ways to produce different effects in different brain regions—with a single drug. Cariprazine’s particular binding profile—higher affinity and higher selectivity for D3 receptors than for D2 receptors compared with either aripiprazole or brexpiprazole—may secure a role for it in managing psychosis and mood disorders.

1. Vraylar [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ: Actavis Pharma, Inc.; 2015.

2. McCormack PL, Cariprazine: first global approval. Drugs. 2015;75(17):2035-2043.

3. Kiss B, Horváth A, Némethy Z, et al. Cariprazine (RGH-188), a dopamine D(3) receptor-preferring, D(3)/D(2) dopamine receptor antagonist-partial agonist antipsychotic candidate: in vitro and neurochemical profile. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;333(1):328-340.

4. Potkin, S, Keator, D, Mukherjee J, et al. P. 1. E 028 dopamine D3 and D2 receptor occupancy of cariprazine in schizophrenic patients. Eur Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;19(suppl 3):S316.

5. Veselinovicˇ T, Paulzen M, Gründer G. Cariprazine, a new, orally active dopamine D2/3 receptor partial agonist for the treatment of schizophrenia, bipolar mania and depression. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13(11):1141-1159.

6. Cutler A, Mokliatchouk O, Laszlovszky I, et al. Cariprazine in acute schizophrenia: a fixed-dose phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled trial. Abstract presented at: 166th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; May 18-22, 2013; San Francisco, CA.

7. Durgam S, Starace A, Li D, et al. An evaluation of the safety and efficacy of cariprazine in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: a phase II, randomized clinical trial. Schizophr Res. 2014;152(2-3):450-457.

8. Kane JM, Zukin S, Wang Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of cariprazine in acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: results from an international, phase III clinical trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;35(4):367-373.

9. Bose A, Starace A, Lu, K, et al. Cariprazine in the treatment of acute mania in bipolar disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. Poster presented at: 16th Annual Meeting of the College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists; April 21-24, 2013; Colorado Springs, CO.

10. Calabrese JR, Keck PE Jr, Starace A, et al. Efficacy and safety of low- and high-dose cariprazine in acute and mixed mania associated with bipolar I disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(3):284-292.

11. Durgam S, Starace A, Li D, et al. The efficacy and tolerability of cariprazine in acute mania associated with bipolar I disorder: a phase II trial. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17(1):63-75.

12. Ketter, T. A phase III, open-label, 16-week study of flexibly dosed cariprazine in 402 patients with bipolar I disorder. Presented at: 53rd Annual Meeting of the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit; May 28-31, 2013; Hollywood, FL.

13. Bose A, Li D, Migliore R. The efficacy and safety of the novel antipsychotic cariprazine in the acute exacerbation of schizophrenia. Poster presented at: 50th Annual Meeting of the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit; June 14-17, 2010; Boca Raton, FL.

14. Citrome L. Cariprazine: chemistry, pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, and metabolism, clinical efficacy, safety, and tolerability. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2013;9(2):193-206.

15. Sachs GS, Greenberg WM, Starace A, et al. Cariprazine in the treatment of acute mania in bipolar I disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:296-302.

16. Vieta E, Durgam S, Lu K, et al. Effect of cariprazine across the symptoms of mania in bipolar I disorder: analyses of pooled data from phase II/III trials. Eur Neuropsycholpharmacol. 2015;25(11):1882-1891.

1. Vraylar [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ: Actavis Pharma, Inc.; 2015.

2. McCormack PL, Cariprazine: first global approval. Drugs. 2015;75(17):2035-2043.

3. Kiss B, Horváth A, Némethy Z, et al. Cariprazine (RGH-188), a dopamine D(3) receptor-preferring, D(3)/D(2) dopamine receptor antagonist-partial agonist antipsychotic candidate: in vitro and neurochemical profile. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;333(1):328-340.

4. Potkin, S, Keator, D, Mukherjee J, et al. P. 1. E 028 dopamine D3 and D2 receptor occupancy of cariprazine in schizophrenic patients. Eur Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;19(suppl 3):S316.

5. Veselinovicˇ T, Paulzen M, Gründer G. Cariprazine, a new, orally active dopamine D2/3 receptor partial agonist for the treatment of schizophrenia, bipolar mania and depression. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13(11):1141-1159.

6. Cutler A, Mokliatchouk O, Laszlovszky I, et al. Cariprazine in acute schizophrenia: a fixed-dose phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled trial. Abstract presented at: 166th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association; May 18-22, 2013; San Francisco, CA.

7. Durgam S, Starace A, Li D, et al. An evaluation of the safety and efficacy of cariprazine in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: a phase II, randomized clinical trial. Schizophr Res. 2014;152(2-3):450-457.

8. Kane JM, Zukin S, Wang Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of cariprazine in acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: results from an international, phase III clinical trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;35(4):367-373.

9. Bose A, Starace A, Lu, K, et al. Cariprazine in the treatment of acute mania in bipolar disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. Poster presented at: 16th Annual Meeting of the College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists; April 21-24, 2013; Colorado Springs, CO.

10. Calabrese JR, Keck PE Jr, Starace A, et al. Efficacy and safety of low- and high-dose cariprazine in acute and mixed mania associated with bipolar I disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(3):284-292.

11. Durgam S, Starace A, Li D, et al. The efficacy and tolerability of cariprazine in acute mania associated with bipolar I disorder: a phase II trial. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17(1):63-75.

12. Ketter, T. A phase III, open-label, 16-week study of flexibly dosed cariprazine in 402 patients with bipolar I disorder. Presented at: 53rd Annual Meeting of the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit; May 28-31, 2013; Hollywood, FL.

13. Bose A, Li D, Migliore R. The efficacy and safety of the novel antipsychotic cariprazine in the acute exacerbation of schizophrenia. Poster presented at: 50th Annual Meeting of the New Clinical Drug Evaluation Unit; June 14-17, 2010; Boca Raton, FL.

14. Citrome L. Cariprazine: chemistry, pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, and metabolism, clinical efficacy, safety, and tolerability. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2013;9(2):193-206.

15. Sachs GS, Greenberg WM, Starace A, et al. Cariprazine in the treatment of acute mania in bipolar I disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:296-302.

16. Vieta E, Durgam S, Lu K, et al. Effect of cariprazine across the symptoms of mania in bipolar I disorder: analyses of pooled data from phase II/III trials. Eur Neuropsycholpharmacol. 2015;25(11):1882-1891.

Cariprazine for schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder

Cariprazine is a newly approved (September 2015) dopamine D3/D2 receptor partial agonist with higher affinity for the D3 receptor than for D2. The drug is FDA-indicated for treating schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder (BD I)1,2 (Table 1). In clinical trials, cariprazine alleviated symptoms of schizophrenia and mixed and manic symptoms of BD I, with minimal effect on metabolic parameters, the prolactin level, and cardiac conduction.

Clinical implications

Despite numerous developments in pharmacotherapeutics, people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder continue to struggle with residual symptoms or endure treatments that produce adverse effects (AEs). In particular, metabolic issues, sedation, and cognitive impairment plague many current treatment options for these disorders.

Receptor blocking. As a dopamine D3-preferring D3/D2 partial agonist, cariprazine offers an alternative to antipsychotics that preferentially modulate D2 receptors. First-generation (typical) antipsychotics block D2 receptors; atypical antipsychotics block D2 receptors and 5-HT2A receptors. Dopamine partial agonists aripiprazole and brexpiprazole are D2-preferring, with minimal D3 effects. In contrast, cariprazine has a 6-fold to 8-fold higher affinity for D3 receptors than for D2 receptors, and has specificity for the D3 receptor that is 3 to 10 times higher than what aripiprazole has for the D3 receptor3-5 (Table 2).

Use in schizophrenia. Recommended dosage range is 1.5 to 6 mg/d. In Phase-III clinical trials, dosages of 3 to 9 mg/d produced significant improvement on the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS) and on the Clinical Global Impression scale. Higher dosages (6 to 9 mg/d) showed early separation from placebo—by the end of Week 1—but carried a dosage-related risk of AEs, leading the FDA to recommend 6 mg/d as the maximum dosage.1,6-8

Use in manic or mixed episodes of BD I. Recommended dosage range is 3 to 6 mg/d. In clinical trials, dosages in the range of 3 to 12 mg/d were effective for acute manic or mixed symptoms; significant improvement in the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) score was seen as early as Day 4. Dosages >6 mg/d yielded no additional benefit and were associated with increased risk of AEs.9-12

Pharmacologic profile, adverse effects. Cariprazine has a pharmacologic profile consistent with the generally favorable metabolic profile and lack of anticholinergic effects seen in clinical trials. In short- and long-term trials, the drug had minimal effects on prolactin, blood pressure, and cardiac conduction.13

Across clinical trials for both disorders, akathisia and parkinsonism were among more common AEs of cariprazine. Both AEs were usually mild, resulting in relatively few premature discontinuations from trials. Parkinsonism appeared somewhat dosage-related; akathisia had no clear relationship to dosage.

How it works

The theory behind the use of partial agonists, including cariprazine, is that these agents restore homeostatic balance to neurochemical circuits by:

- decreasing the effects of endogenous neurotransmitters (dopamine tone) in regions of the brain where their transmission is excessive, such as mesolimbic regions in schizophrenia or mania

- simultaneously increasing neurotransmission in regions where transmission of endogenous neurotransmitters is low, such as the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia

- exerting little effect in regions where neurotransmitter activity is normal, such as the pituitary gland.

- simultaneously

Cariprazine has higher binding affinity for dopamine D3 receptors (Ki 0.085 nM) than for D2L receptors (Ki 0.49 nM) and D2S receptors (Ki 0.69 nM). The drug also has strong affinity for serotonin receptor 5-HT2B; moderate affinity for 5-HT1A; and lower affinity for 5-HT2A, histamine H1, and 5-HT7 receptors. Cariprazine has little or no affinity for adrenergic or cholinergic receptors.14In patients with schizophrenia, as measured on PET scanning, a dosage of 1.5 mg/d yielded 69% to 75% D2/D3 receptor occupancy. A dosage of 3 mg/d yielded >90% occupancy.

Search for an understanding of action continues. The relative contribution of D3 partial agonism, compared with D2 partial agonism, is a subject of ongoing basic scientific and clinical research. D3 is an autoreceptor that (1) controls phasic, but not tonic, activity of dopamine nerve cells and (2) mediates behavioral abnormalities induced by glutamate and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists.5,12 In animal studies, D3-preferring agents have been shown to exert pro-cognitive effects and improve anhedonic symptoms.

Pharmacokinetics

Cariprazine is a once-daily medication with a relatively long half-life that can be taken with or without food. Dosages of 3 to 12 mg/d yield a fairly linear, dose-proportional increase in plasma concentration. The peak serum concentration for cariprazine is 3 to 4 hours under fasting conditions; taking the drug with food causes a slight delay in absorption but does not have a significant effect on the area under the curve. Mean half-life for cariprazine is 2 to 5 days over a dosage range of 1.5 to 12.5 mg/d in otherwise healthy adults with schizophrenia.1

Cariprazine is metabolized primarily by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4. It is a weak inhibitor of CYP2D6 and CYP3A4.1 Hepatic metabolism of cariprazine produces 2 active metabolites: desmethyl-cariprazine (DCAR) and didesmethyl-cariprazine (DDCAR), both of which are equipotent to cariprazine. After multiple dose administration, mean cariprazine and DCAR levels reach steady state in 1 to 2 weeks; DDCAR, in 4 to 8 weeks. The systemic exposure and serum levels of DDCAR are roughly 3-fold greater than cariprazine because of the longer elimination half-life of DDCAR.1

Efficacy in schizophrenia

The efficacy of cariprazine in schizophrenia was established by 3 six-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Two trials were fixed-dosage; a third used 2 flexible dosage ranges. The primary efficacy measure was change from baseline in the total score of the PANSS at the end of Week 6, compared with placebo. In all trials, patients were adults (age 18 to 60) who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for schizophrenia and had a PANSS score between 80 and 120 at screening and baseline.

Study 1 (n = 711) compared dosages of 1.5 mg/d, 3 mg/d, and 4.5 mg/d with placebo.7 All cariprazine dosages and an active control (risperdone) were superior to placebo in reducing symptoms of schizophrenia, as measured by the PANSS. The placebo-subtracted differences on PANSS score at 6 weeks for dosages of 1.5 mg/d, 3 mg/d, and 4.5 mg/d were –7.6, –8.8, –10.4, respectively (significant at 95% CI).

Study 2 (n = 151) compared 3 mg/d and 6 mg/d dosages of cariprazine with placebo.1 Both dosages and an active control (aripiprazole) were superior to placebo in reducing PANSS scores. Placebo-subtracted differences on PANSS score at 6 weeks for dosages of 3 mg/d and 6 mg/day were –6.0, –8.8, respectively (significant at 95% CI).

Study 3 (n = 147) was a fixed-flexible dosage trial comparing cariprazine, 3 to 6 mg/d and 6 to 9 mg/d dosage ranges, to placebo.8 Both ranges were superior to placebo in reducing symptoms on PANSS. Placebo-subtracted differences from placebo on PANSS at 6 weeks for cariprazine 3 to 6 or 6 to 9 mg/d were –6.8, –9.9, respectively (significant at 95% CI).

These trials established the efficacy of cariprazine for acute schizophrenia at dosages ranging from 1.5 to 9 mg/d. Although there was a modest trend toward higher efficacy at higher dosages, there was a dose-related increase in certain adverse reactions (extrapyramidal symptoms [EPS]) at dosages >6 mg/d.1

Efficacy in bipolar disorder

The efficacy of cariprazine for acute treatment of manic or mixed episodes of BD I was established in 3 randomized, placebo-controlled, flexibly dosed 3-week trials. In all trials, patients were adults (age 18 to 65) who met DSM-IV-TR criteria for BD I with manic or mixed episodes and with or without psychotic features (YMRS score, ≥20). The primary efficacy measure in the 3 trials was a change from baseline in the total YMRS score at the end of Week 3, compared with placebo.

Study 1 (n = 492) compared 2 flexibly dosed ranges of cariprazine (3 to 6 mg/d and 6 to 12 mg/d) with placebo.10 Both dosage ranges were superior to placebo in reducing mixed and manic symptoms, as measured by reduction in the total YMRS score. Placebo-subtracted differences in YMRS scores from placebo at Week 3 for cariprazine 3 to 6 mg/d and 6 to 12 mg/d were –6.1, –5.9, respectively (significant at 95% CI). The higher range offered no additional advantage over the lower range.

Study 2 (n = 235) compared flexibly dosed cariprazine, 3 to 12 mg/d, to placebo.11 Cariprazine was superior to placebo in reducing bipolar symptoms as measured by the YMRS. The difference between cariprazine 3 to 12 mg/d and placebo on the YMRS score at Week 3 was –6.1 (significant at 95% CI).

Study 3 (n = 310) compared flexibly dosed cariprazine, 3 to 12 mg/d, with placebo.15 Again, cariprazine was superior to placebo in reducing the YMRS score at Week 3: difference, –4.3 (significant at 95% CI).

These trials establish the efficacy of cariprazine in treating acute mania or mixed BD I episodes at dosages ranging from 3 to 12 mg/d. Dosages >6 mg/d did not offer additional benefit over lower dosages, and resulted in a dosage-related increase in EPS at dosages >6 mg/d.16

Tolerability

Cariprazine generally was well tolerated in short-term trials for schizophrenia and BD I. The only treatment-emergent adverse event reported for at least 1 treatment group in all trials at a rate of ≥10%, and at least twice the rate seen with placebo was akathisia. Adverse events reported at a lower rate than placebo included EPS (particularly parkinsonism), restlessness, headache, insomnia, fatigue, and gastrointestinal distress. The discontinuation rate due to AEs for treatment groups and placebo-treated patients generally was similar. In schizophrenia Study 3, for example, the discontinuation rate due to AEs was 13% for placebo; 14% for cariprazine, 3 to 6 mg/d; and 13% for cariprazine, 6 to 9 mg/d.1 48-Week open-label safety study. Patients with schizophrenia received open-label cariprazine for as long as 48 weeks.7 Serious adverse events were reported in 12.9%, including 1 death (suicide); exacerbation of symptoms of schizophrenia (4.3%); and psychosis (2.2%). Treatment-emergent adverse events reported in at least 10% of patients included akathisia (14.0%), insomnia (14.0%), and weight gain (11.8%). The mean change in laboratory values, blood pressure, pulse rate, and electrocardiographic parameters was clinically insignificant.

Other studies. In a 16-week, open-label extension study of patients with BD I, the major tolerability issue was akathisia. This AE developed in 37% of patients and led to a 5% withdrawal rate.12

In short- and long-term studies for either indication, the effect of the drug on metabolic parameters appears to be small. In studies with active controls, potentially significant weight gain (>7%) was greater for aripiprazole and risperidone than for cariprazine.6,7 The effect on the prolactin level was minimal. There do not appear to be clinically meaningful changes in laboratory values, vital signs, or QT interval.

Unique clinical issues

Preferential binding. Cariprazine is the third dopamine partial agonist approved for use in the United States; unlike the other 2—aripiprazole and brexpiprazole—cariprazine shows preference for D3 receptors over D2 receptors. The exact clinical impact of a preference for D3 and the drug’s partial agonism of 5-HT1A has not been fully elucidated.

EPS, including akathisia and parkinsonism, were among common adverse events. Both were usually mild, with 0.5% of schizophrenia patients and 2% of BD I patients dropping out of trials because of any type of EPS-related AEs.

Why Rx? On a practical medical level, reasons to prescribe cariprazine likely include:

- minimal effect on prolactin

- relative lack of effect on metabolic parameters, including weight (cariprazine showed less weight gain than risperidone or aripiprazole control arms in trials).

Dosing

The recommended dosage of cariprazine for schizophrenia ranges from 1.5 to 6 mg/d. The recommended starting dosage is 1.5 mg/d, which can be increased to 3 mg on Day 2, with further upward dosage adjustments of 1.5 to 3 mg/d, based on clinical response and tolerability.1

The recommended dosages of cariprazine for mixed and manic episodes of BD I range from 3 to 6 mg/d. The recommended starting dosage is 1.5 mg/d, which can be increased to 3 mg on Day 2, with further upward dosage adjustments of 1.5 to 3 mg/d, based on clinical response and tolerability.1

Other key aspects of dosing to keep in mind:

- Because of the long half-life and 2 equipotent active metabolites of cariprazine, any changes made to the dosage will not be reflected fully in the serum level for 2 weeks.

- Administering the drug with food slightly delays, but does not affect, the extent of absorption.

- Because the drug is metabolized primarily by CYP3A4, dosage adjustment is required in the presence of a CYP3A4 inhibitor; the recommended starting dosage of cariprazine is 1.5 mg every other day with a maximum dosage of 3 mg/d when it is administered concomitantly with a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor.

- Because data are not available regarding concomitant use of cariprazine with a strong CYP3A4 inducer, this practice is not recommended.1

- Because the drug is metabolized primarily by CYP3A4, dosage adjustment is required in the presence of a CYP3A4 Because data are not available regarding concomitant use of cariprazine with a strong CYP3A4

Contraindications

Cariprazine carries a FDA black-box warning of increased mortality in older patients who have dementia-related psychosis, as other atypical antipsychotics do. Clinical trials produced few data about the use of cariprazine in geriatric patients; no data exist about use in the pediatric population.1

Metabolic, prolactin, and cardiac concerns about cariprazine appeared favorably minor in Phase-III and long-term safety trials. Concomitant use of cariprazine with any strong inducer of CYP3A4 has not been studied, and is not recommended. Dosage reduction is recommended when using cariprazine concomitantly with a CYP3A4 inhibitor.1

In conclusion