User login

VIDEO: Office-based hereditary cancer risk testing is doable

AUSTIN, TEXAS – , according to Mark S. DeFrancesco, MD, and his associates.

Few community-based ob.gyns. routinely screen their patients for hereditary cancer risks, Dr. DeFrancesco said at the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, despite ACOG’s position that they are fully trained and qualified to do so. He and his colleagues studied an intervention aimed at streamlining and standardizing genetic assessment in their practice.

A team of physicians, staff, genetic counselors, and process engineers analyzed how hereditary cancer risk assessment was being done at five clinical sites of two community ob.gyn. practices – Dr. DeFrancesco’s practice in Waterbury, Conn., and that of Richard Waldman, MD, in Syracuse, N.Y. – then refined workflows and added tools to create a turnkey process for assessment and screening, Dr. DeFrancesco said.

Under the new process, patients completed a family cancer history in the exam room prior to seeing their physician. Genetic testing was offered to patients who met National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for hereditary/familial high-risk assessment for breast and ovarian cancer (J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017 Jan;15[1]:9-20). Those who chose to be tested were able to provide a saliva sample in the office. Counseling was provided to appropriate patients.

The number of patients tested for hereditary risk of breast and ovarian cancer increased dramatically with the new process. During the 8-week period after the intervention, 4% (165) were tested out of 4,107 total patients seen; during the 8 weeks preceding, 1% (43) of 3,882 patients were tested.

Overall, 92.8% (3,811) of patients seen after the intervention provided a family cancer history. Almost a quarter – 23.5% (906) – met NCCN criteria for genetic testing.

A total of 318 patients agreed to undergo genetic testing and 165 (51.9%) completed the process. Nine patients (5.5%) were found to carry a pathogenic gene variant associated with hereditary breast and/or ovarian cancer or Lynch syndrome, Dr. DeFrancesco and colleagues reported.

Patients and providers also were surveyed regarding their experience with the new process. Patients overwhelming noted that they understood the information provided (98.8%), and that they were satisfied with the overall process (97.6%). All 15 providers said that they would continue to use the new process in their practice and most – 13 of 15 – said they found the process thorough and felt comfortable recommending genetic counseling without referral to a genetic counselor (2 were undecided).

“I think that this study really proves the concept that in a community-based practice, we can test our patients,” Dr. DeFrancesco said in an interview.

Myriad Genetics sponsored the study. Dr. DeFrancesco reported no financial conflicts of interest. His coauthors include employees of Myriad Genetics, some with ownership interests.

SOURCE: DeFrancesco, MS et al. ACOG 2018 3K.

AUSTIN, TEXAS – , according to Mark S. DeFrancesco, MD, and his associates.

Few community-based ob.gyns. routinely screen their patients for hereditary cancer risks, Dr. DeFrancesco said at the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, despite ACOG’s position that they are fully trained and qualified to do so. He and his colleagues studied an intervention aimed at streamlining and standardizing genetic assessment in their practice.

A team of physicians, staff, genetic counselors, and process engineers analyzed how hereditary cancer risk assessment was being done at five clinical sites of two community ob.gyn. practices – Dr. DeFrancesco’s practice in Waterbury, Conn., and that of Richard Waldman, MD, in Syracuse, N.Y. – then refined workflows and added tools to create a turnkey process for assessment and screening, Dr. DeFrancesco said.

Under the new process, patients completed a family cancer history in the exam room prior to seeing their physician. Genetic testing was offered to patients who met National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for hereditary/familial high-risk assessment for breast and ovarian cancer (J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017 Jan;15[1]:9-20). Those who chose to be tested were able to provide a saliva sample in the office. Counseling was provided to appropriate patients.

The number of patients tested for hereditary risk of breast and ovarian cancer increased dramatically with the new process. During the 8-week period after the intervention, 4% (165) were tested out of 4,107 total patients seen; during the 8 weeks preceding, 1% (43) of 3,882 patients were tested.

Overall, 92.8% (3,811) of patients seen after the intervention provided a family cancer history. Almost a quarter – 23.5% (906) – met NCCN criteria for genetic testing.

A total of 318 patients agreed to undergo genetic testing and 165 (51.9%) completed the process. Nine patients (5.5%) were found to carry a pathogenic gene variant associated with hereditary breast and/or ovarian cancer or Lynch syndrome, Dr. DeFrancesco and colleagues reported.

Patients and providers also were surveyed regarding their experience with the new process. Patients overwhelming noted that they understood the information provided (98.8%), and that they were satisfied with the overall process (97.6%). All 15 providers said that they would continue to use the new process in their practice and most – 13 of 15 – said they found the process thorough and felt comfortable recommending genetic counseling without referral to a genetic counselor (2 were undecided).

“I think that this study really proves the concept that in a community-based practice, we can test our patients,” Dr. DeFrancesco said in an interview.

Myriad Genetics sponsored the study. Dr. DeFrancesco reported no financial conflicts of interest. His coauthors include employees of Myriad Genetics, some with ownership interests.

SOURCE: DeFrancesco, MS et al. ACOG 2018 3K.

AUSTIN, TEXAS – , according to Mark S. DeFrancesco, MD, and his associates.

Few community-based ob.gyns. routinely screen their patients for hereditary cancer risks, Dr. DeFrancesco said at the annual meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, despite ACOG’s position that they are fully trained and qualified to do so. He and his colleagues studied an intervention aimed at streamlining and standardizing genetic assessment in their practice.

A team of physicians, staff, genetic counselors, and process engineers analyzed how hereditary cancer risk assessment was being done at five clinical sites of two community ob.gyn. practices – Dr. DeFrancesco’s practice in Waterbury, Conn., and that of Richard Waldman, MD, in Syracuse, N.Y. – then refined workflows and added tools to create a turnkey process for assessment and screening, Dr. DeFrancesco said.

Under the new process, patients completed a family cancer history in the exam room prior to seeing their physician. Genetic testing was offered to patients who met National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for hereditary/familial high-risk assessment for breast and ovarian cancer (J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017 Jan;15[1]:9-20). Those who chose to be tested were able to provide a saliva sample in the office. Counseling was provided to appropriate patients.

The number of patients tested for hereditary risk of breast and ovarian cancer increased dramatically with the new process. During the 8-week period after the intervention, 4% (165) were tested out of 4,107 total patients seen; during the 8 weeks preceding, 1% (43) of 3,882 patients were tested.

Overall, 92.8% (3,811) of patients seen after the intervention provided a family cancer history. Almost a quarter – 23.5% (906) – met NCCN criteria for genetic testing.

A total of 318 patients agreed to undergo genetic testing and 165 (51.9%) completed the process. Nine patients (5.5%) were found to carry a pathogenic gene variant associated with hereditary breast and/or ovarian cancer or Lynch syndrome, Dr. DeFrancesco and colleagues reported.

Patients and providers also were surveyed regarding their experience with the new process. Patients overwhelming noted that they understood the information provided (98.8%), and that they were satisfied with the overall process (97.6%). All 15 providers said that they would continue to use the new process in their practice and most – 13 of 15 – said they found the process thorough and felt comfortable recommending genetic counseling without referral to a genetic counselor (2 were undecided).

“I think that this study really proves the concept that in a community-based practice, we can test our patients,” Dr. DeFrancesco said in an interview.

Myriad Genetics sponsored the study. Dr. DeFrancesco reported no financial conflicts of interest. His coauthors include employees of Myriad Genetics, some with ownership interests.

SOURCE: DeFrancesco, MS et al. ACOG 2018 3K.

REPORTING FROM ACOG 2018

Key clinical point: Ob.gyns. can successfully integrate hereditary cancer risk testing into their practices.

Major finding: Office-based genetic testing increased from 1% to 4% of patients seen.

Study details: Prospective, single-arm process intervention study screening more than 4,000 women at 5 ob.gyn. practice sites.

Disclosures: Myriad Genetics sponsored the study. Dr. DeFrancesco reported no financial conflicts of interest. His coauthors included employees of Myriad Genetics, some with ownership interests.

Source: DeFrancesco, MS et al. ACOG 2018 poster 3K.

How does oral contraceptive use affect one’s risk of ovarian, endometrial, breast, and colorectal cancers?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Hormonal contraception (HC), including OC, is a central component of women’s health care worldwide. In addition to its many potential health benefits (pregnancy prevention, menstrual symptom management), HC use modifies the risk of various cancers. As we discussed in the February 2018 issue of OBG Management, a recent large population-based study in Denmark showed a small but statistically significant increase in breast cancer risk in HC users.1,2 Conversely, HC use has a long recognized protective effect against ovarian and endometrial cancers. These risk relationships may be altered by other modifiable lifestyle characteristics, such as smoking, alcohol use, obesity, and physical activity.

Details of the study

Michels and colleagues evaluated the association between OC use and multiple cancers, stratifying these risks by duration of use and various modifiable lifestyle characteristics.3 The authors used a prospective survey-based cohort (the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study) linked with state cancer registries to evaluate this relationship in a diverse population of 196,536 women across 6 US states and 2 metropolitan areas. Women were enrolled in 1995–1996 and followed until 2011. Cancer risks were presented as hazard ratios (HR), which indicate the risk of developing a specific cancer type in OC users compared with nonusers. HRs differ from relative risks (RR) and odds ratios because they compare the instantaneous risk difference between the 2 groups, rather than the cumulative risk difference over the entire study period.4

Duration of OC use and risk reduction

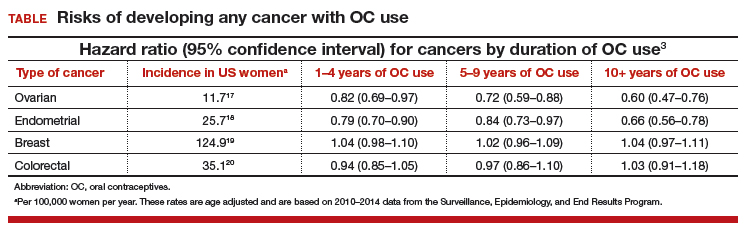

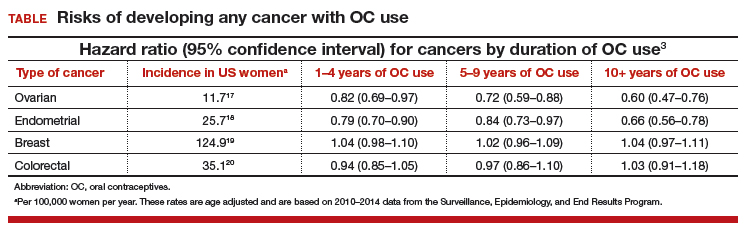

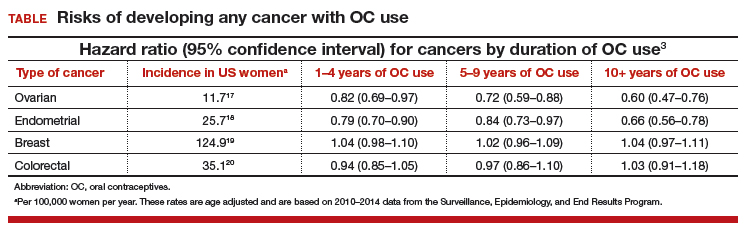

In this study population, OC use was associated with a significantly decreased risk of ovarian cancer, and this risk increased with longer duration of use (TABLE). Similarly, long-term OC use was associated with a decreased risk for endometrial cancer. These effects were true across various lifestyle characteristics, including smoking status, alcohol use, body mass index (BMI), and physical activity level.

There was a nonsignificant trend toward increased risk of breast cancer among OC users. The most significant elevation in breast cancer risk was found in long-term users who were current smokers (HR, 1.21 [95% confidence interval (CI), 1.01–1.44]). OC use had a minimal effect on colorectal cancer risk.

The bottom line. US women using OCs were significantly less likely to develop ovarian and endometrial cancers compared with nonusers. This risk reduction increased with longer duration of OC use and was true regardless of lifestyle. Conversely, there was a trend toward a slightly increased risk of developing breast cancer in OC users.

Study strengths and weaknesses

The effect on breast cancer risk is less pronounced than that reported in a recent large, prospective cohort study in Denmark, which reported an RR of developing breast cancer of 1.20 (95% CI, 1.14–1.26) among all current or recent HC users.1 These differing results may be due to the US study population’s increased heterogeneity compared with the Danish cohort; potential recall bias in the US study (not present in the Danish study because pharmacy records were used); the larger size of the Danish study (that is, ability to detect very small effect sizes); and lack of information on OC formulation, recency of use, and parity in the US study.

Nevertheless, the significant protective effect against ovarian and endometrial cancers (reported previously in numerous studies) should be a part of totality of cancer risk when counseling patients on any potential increased risk of breast cancer with OC use.

According to the study by Michels and colleagues, overall, women using OCs had a decreased risk of ovarian and endometrial cancers and a trend toward a slightly increased risk of breast cancer.3 Based on this and prior estimates, the overall risk of developing any cancer appears to be lower in OC users than in nonusers.5,6

Consider discussing the points below when counseling women on OC use and cancer risk.

Cancer prevention

- OC use was associated with a significantly decreased risk of both ovarian and endometrial cancers. This effect increased with longer duration of use.

- Ovarian cancer risk reduction persisted regardless of smoking status, BMI, alcohol use, or physical activity level.

- The largest reduction in endometrial cancer was seen in current smokers and patients with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2.

Breast cancer risk

- There was a trend toward a slightly increased risk of breast cancer with OC use of any duration.

- A Danish cohort study showed a significantly higher risk (although still an overall low risk) of breast cancer with HC use (RR, 1.20 [95% CI, 1.14-1.26]).1

- The differences in these 2 results may be related to study design and population characteristic differences.

Overall cancer risk

- The definitive and larger risk reductions in ovarian and endometrial cancer compared with the lesser risk increase in breast cancer suggest a net decrease in developing any cancer for OC users.3,5,6

Risks of pregnancy prevention failure

- OCs are an effective method for preventing unintended pregnancy. Risks of OCs should be weighed against the risks of unintended pregnancy.

- In the United States, the maternal mortality rate (2015) is 26.4 deaths for every 100,000 women.7 The risk of maternal mortality is substantially higher than even the highest published estimates of HC-attributable breast cancer rates (that is, 13 incremental breast cancers for every 100,000 women using HC; 2 incremental breast cancers for every 100,000 women 35 years of age or younger using HC).1

- Unintended pregnancy is a serious maternal-child health problem, and it has substantial health, social, and economic consequences.8-14

- Unintended pregnancies generate a significant economic burden (an estimated $21 billion in direct and indirect costs for the US health care system per year).15 Approximately 42% of unintended pregnancies end in abortion.16

-- Dana M. Scott, MD, and Mark D. Pearlman, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Mørch LS, Skovlund CW, Hannaford PC, Iversen L, Fielding S, Lidegaard Ø. Contemporary hormonal contraception and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2228–2239.

- Scott DM, Pearlman MD. Does hormonal contraception increase the risk of breast cancer? OBG Manag. 2018;30(2):16–17.

- Michels KA, Pfeiffer RM, Brinton LA, Trabert B. Modification of the associations between duration of oral contraceptive use and ovarian, endometrial, breast, and colorectal cancers [published online January 18, 2018]. JAMA Oncol. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.4942.

- Sedgwick P. Hazards and hazard ratios. BMJ. 2012;345:e5980.

- Bassuk SS, Manson JE. Oral contraceptives and menopausal hormone therapy: relative and attributable risks of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and other health outcomes. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(3):193–200.

- Hunter D. Oral contraceptives and the small increased risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2276–2277.

- GBD 2015 Maternal Mortality Collaborators. Global, regional, and national levels of maternal mortality, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1775–1812.

- Brown SS, Eisenberg L, eds. The best intentions: unintended pregnancy and the well-being of children and families. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 1995:50–90.

- Klein JD; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence. Adolescent pregnancy: current trends and issues. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):281–286.

- Logan C, Holcombe E, Manlove J, Ryan S; The National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy and Child Trends. The consequences of unintended childbearing. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b353/b02ae6cad716a7f64ca48b3edae63544c03e.pdf?_ga=2.149310646.1402594583.1524236972-1233479770.1524236972&_gac=1.195699992.1524237056. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Finer LB, Sonfield A. The evidence mounts on the benefits of preventing unintended pregnancy. Contraception. 2013;87(2):126–127.

- Trussell J, Henry N, Hassan F, Prezioso A, Law A, Filonenko A. Burden of unintended pregnancy in the United States: potential savings with increased use of long-acting reversible contraception. Contraception. 2013;87(2):154–161.

- Sonfield A, Kost K. Public costs from unintended pregnancies and the role of public insurance programs in paying for pregnancy and infant care: estimates for 2008. Guttmacher Institute. https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/public-costs-of-up.pdf. Published October 2013. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Forrest JD, Singh S. Public-sector savings resulting from expenditures for contraceptive services. Fam Plann Perspect. 1990;22(1):6–15.

- Sonfield A, Kost K. Public costs from unintended pregnancies and the role of public insurance programs in paying for pregnancy-related care: national and state estimates for 2010. Guttmacher Institute. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/public-costs-of-UP-2010.pdf. Published February 2015. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(9):843–852.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: ovarian cancer. Bethesda, MD; National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/ovary.html. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: uterine cancer. Bethesda, MD; National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/corp.html. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: female breast cancer. Bethesda, MD; National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: colorectal cancer. Bethesda, MD; National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html. Accessed April 20, 2018.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Hormonal contraception (HC), including OC, is a central component of women’s health care worldwide. In addition to its many potential health benefits (pregnancy prevention, menstrual symptom management), HC use modifies the risk of various cancers. As we discussed in the February 2018 issue of OBG Management, a recent large population-based study in Denmark showed a small but statistically significant increase in breast cancer risk in HC users.1,2 Conversely, HC use has a long recognized protective effect against ovarian and endometrial cancers. These risk relationships may be altered by other modifiable lifestyle characteristics, such as smoking, alcohol use, obesity, and physical activity.

Details of the study

Michels and colleagues evaluated the association between OC use and multiple cancers, stratifying these risks by duration of use and various modifiable lifestyle characteristics.3 The authors used a prospective survey-based cohort (the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study) linked with state cancer registries to evaluate this relationship in a diverse population of 196,536 women across 6 US states and 2 metropolitan areas. Women were enrolled in 1995–1996 and followed until 2011. Cancer risks were presented as hazard ratios (HR), which indicate the risk of developing a specific cancer type in OC users compared with nonusers. HRs differ from relative risks (RR) and odds ratios because they compare the instantaneous risk difference between the 2 groups, rather than the cumulative risk difference over the entire study period.4

Duration of OC use and risk reduction

In this study population, OC use was associated with a significantly decreased risk of ovarian cancer, and this risk increased with longer duration of use (TABLE). Similarly, long-term OC use was associated with a decreased risk for endometrial cancer. These effects were true across various lifestyle characteristics, including smoking status, alcohol use, body mass index (BMI), and physical activity level.

There was a nonsignificant trend toward increased risk of breast cancer among OC users. The most significant elevation in breast cancer risk was found in long-term users who were current smokers (HR, 1.21 [95% confidence interval (CI), 1.01–1.44]). OC use had a minimal effect on colorectal cancer risk.

The bottom line. US women using OCs were significantly less likely to develop ovarian and endometrial cancers compared with nonusers. This risk reduction increased with longer duration of OC use and was true regardless of lifestyle. Conversely, there was a trend toward a slightly increased risk of developing breast cancer in OC users.

Study strengths and weaknesses

The effect on breast cancer risk is less pronounced than that reported in a recent large, prospective cohort study in Denmark, which reported an RR of developing breast cancer of 1.20 (95% CI, 1.14–1.26) among all current or recent HC users.1 These differing results may be due to the US study population’s increased heterogeneity compared with the Danish cohort; potential recall bias in the US study (not present in the Danish study because pharmacy records were used); the larger size of the Danish study (that is, ability to detect very small effect sizes); and lack of information on OC formulation, recency of use, and parity in the US study.

Nevertheless, the significant protective effect against ovarian and endometrial cancers (reported previously in numerous studies) should be a part of totality of cancer risk when counseling patients on any potential increased risk of breast cancer with OC use.

According to the study by Michels and colleagues, overall, women using OCs had a decreased risk of ovarian and endometrial cancers and a trend toward a slightly increased risk of breast cancer.3 Based on this and prior estimates, the overall risk of developing any cancer appears to be lower in OC users than in nonusers.5,6

Consider discussing the points below when counseling women on OC use and cancer risk.

Cancer prevention

- OC use was associated with a significantly decreased risk of both ovarian and endometrial cancers. This effect increased with longer duration of use.

- Ovarian cancer risk reduction persisted regardless of smoking status, BMI, alcohol use, or physical activity level.

- The largest reduction in endometrial cancer was seen in current smokers and patients with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2.

Breast cancer risk

- There was a trend toward a slightly increased risk of breast cancer with OC use of any duration.

- A Danish cohort study showed a significantly higher risk (although still an overall low risk) of breast cancer with HC use (RR, 1.20 [95% CI, 1.14-1.26]).1

- The differences in these 2 results may be related to study design and population characteristic differences.

Overall cancer risk

- The definitive and larger risk reductions in ovarian and endometrial cancer compared with the lesser risk increase in breast cancer suggest a net decrease in developing any cancer for OC users.3,5,6

Risks of pregnancy prevention failure

- OCs are an effective method for preventing unintended pregnancy. Risks of OCs should be weighed against the risks of unintended pregnancy.

- In the United States, the maternal mortality rate (2015) is 26.4 deaths for every 100,000 women.7 The risk of maternal mortality is substantially higher than even the highest published estimates of HC-attributable breast cancer rates (that is, 13 incremental breast cancers for every 100,000 women using HC; 2 incremental breast cancers for every 100,000 women 35 years of age or younger using HC).1

- Unintended pregnancy is a serious maternal-child health problem, and it has substantial health, social, and economic consequences.8-14

- Unintended pregnancies generate a significant economic burden (an estimated $21 billion in direct and indirect costs for the US health care system per year).15 Approximately 42% of unintended pregnancies end in abortion.16

-- Dana M. Scott, MD, and Mark D. Pearlman, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Hormonal contraception (HC), including OC, is a central component of women’s health care worldwide. In addition to its many potential health benefits (pregnancy prevention, menstrual symptom management), HC use modifies the risk of various cancers. As we discussed in the February 2018 issue of OBG Management, a recent large population-based study in Denmark showed a small but statistically significant increase in breast cancer risk in HC users.1,2 Conversely, HC use has a long recognized protective effect against ovarian and endometrial cancers. These risk relationships may be altered by other modifiable lifestyle characteristics, such as smoking, alcohol use, obesity, and physical activity.

Details of the study

Michels and colleagues evaluated the association between OC use and multiple cancers, stratifying these risks by duration of use and various modifiable lifestyle characteristics.3 The authors used a prospective survey-based cohort (the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study) linked with state cancer registries to evaluate this relationship in a diverse population of 196,536 women across 6 US states and 2 metropolitan areas. Women were enrolled in 1995–1996 and followed until 2011. Cancer risks were presented as hazard ratios (HR), which indicate the risk of developing a specific cancer type in OC users compared with nonusers. HRs differ from relative risks (RR) and odds ratios because they compare the instantaneous risk difference between the 2 groups, rather than the cumulative risk difference over the entire study period.4

Duration of OC use and risk reduction

In this study population, OC use was associated with a significantly decreased risk of ovarian cancer, and this risk increased with longer duration of use (TABLE). Similarly, long-term OC use was associated with a decreased risk for endometrial cancer. These effects were true across various lifestyle characteristics, including smoking status, alcohol use, body mass index (BMI), and physical activity level.

There was a nonsignificant trend toward increased risk of breast cancer among OC users. The most significant elevation in breast cancer risk was found in long-term users who were current smokers (HR, 1.21 [95% confidence interval (CI), 1.01–1.44]). OC use had a minimal effect on colorectal cancer risk.

The bottom line. US women using OCs were significantly less likely to develop ovarian and endometrial cancers compared with nonusers. This risk reduction increased with longer duration of OC use and was true regardless of lifestyle. Conversely, there was a trend toward a slightly increased risk of developing breast cancer in OC users.

Study strengths and weaknesses

The effect on breast cancer risk is less pronounced than that reported in a recent large, prospective cohort study in Denmark, which reported an RR of developing breast cancer of 1.20 (95% CI, 1.14–1.26) among all current or recent HC users.1 These differing results may be due to the US study population’s increased heterogeneity compared with the Danish cohort; potential recall bias in the US study (not present in the Danish study because pharmacy records were used); the larger size of the Danish study (that is, ability to detect very small effect sizes); and lack of information on OC formulation, recency of use, and parity in the US study.

Nevertheless, the significant protective effect against ovarian and endometrial cancers (reported previously in numerous studies) should be a part of totality of cancer risk when counseling patients on any potential increased risk of breast cancer with OC use.

According to the study by Michels and colleagues, overall, women using OCs had a decreased risk of ovarian and endometrial cancers and a trend toward a slightly increased risk of breast cancer.3 Based on this and prior estimates, the overall risk of developing any cancer appears to be lower in OC users than in nonusers.5,6

Consider discussing the points below when counseling women on OC use and cancer risk.

Cancer prevention

- OC use was associated with a significantly decreased risk of both ovarian and endometrial cancers. This effect increased with longer duration of use.

- Ovarian cancer risk reduction persisted regardless of smoking status, BMI, alcohol use, or physical activity level.

- The largest reduction in endometrial cancer was seen in current smokers and patients with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2.

Breast cancer risk

- There was a trend toward a slightly increased risk of breast cancer with OC use of any duration.

- A Danish cohort study showed a significantly higher risk (although still an overall low risk) of breast cancer with HC use (RR, 1.20 [95% CI, 1.14-1.26]).1

- The differences in these 2 results may be related to study design and population characteristic differences.

Overall cancer risk

- The definitive and larger risk reductions in ovarian and endometrial cancer compared with the lesser risk increase in breast cancer suggest a net decrease in developing any cancer for OC users.3,5,6

Risks of pregnancy prevention failure

- OCs are an effective method for preventing unintended pregnancy. Risks of OCs should be weighed against the risks of unintended pregnancy.

- In the United States, the maternal mortality rate (2015) is 26.4 deaths for every 100,000 women.7 The risk of maternal mortality is substantially higher than even the highest published estimates of HC-attributable breast cancer rates (that is, 13 incremental breast cancers for every 100,000 women using HC; 2 incremental breast cancers for every 100,000 women 35 years of age or younger using HC).1

- Unintended pregnancy is a serious maternal-child health problem, and it has substantial health, social, and economic consequences.8-14

- Unintended pregnancies generate a significant economic burden (an estimated $21 billion in direct and indirect costs for the US health care system per year).15 Approximately 42% of unintended pregnancies end in abortion.16

-- Dana M. Scott, MD, and Mark D. Pearlman, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Mørch LS, Skovlund CW, Hannaford PC, Iversen L, Fielding S, Lidegaard Ø. Contemporary hormonal contraception and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2228–2239.

- Scott DM, Pearlman MD. Does hormonal contraception increase the risk of breast cancer? OBG Manag. 2018;30(2):16–17.

- Michels KA, Pfeiffer RM, Brinton LA, Trabert B. Modification of the associations between duration of oral contraceptive use and ovarian, endometrial, breast, and colorectal cancers [published online January 18, 2018]. JAMA Oncol. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.4942.

- Sedgwick P. Hazards and hazard ratios. BMJ. 2012;345:e5980.

- Bassuk SS, Manson JE. Oral contraceptives and menopausal hormone therapy: relative and attributable risks of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and other health outcomes. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(3):193–200.

- Hunter D. Oral contraceptives and the small increased risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2276–2277.

- GBD 2015 Maternal Mortality Collaborators. Global, regional, and national levels of maternal mortality, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1775–1812.

- Brown SS, Eisenberg L, eds. The best intentions: unintended pregnancy and the well-being of children and families. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 1995:50–90.

- Klein JD; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence. Adolescent pregnancy: current trends and issues. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):281–286.

- Logan C, Holcombe E, Manlove J, Ryan S; The National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy and Child Trends. The consequences of unintended childbearing. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b353/b02ae6cad716a7f64ca48b3edae63544c03e.pdf?_ga=2.149310646.1402594583.1524236972-1233479770.1524236972&_gac=1.195699992.1524237056. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Finer LB, Sonfield A. The evidence mounts on the benefits of preventing unintended pregnancy. Contraception. 2013;87(2):126–127.

- Trussell J, Henry N, Hassan F, Prezioso A, Law A, Filonenko A. Burden of unintended pregnancy in the United States: potential savings with increased use of long-acting reversible contraception. Contraception. 2013;87(2):154–161.

- Sonfield A, Kost K. Public costs from unintended pregnancies and the role of public insurance programs in paying for pregnancy and infant care: estimates for 2008. Guttmacher Institute. https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/public-costs-of-up.pdf. Published October 2013. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Forrest JD, Singh S. Public-sector savings resulting from expenditures for contraceptive services. Fam Plann Perspect. 1990;22(1):6–15.

- Sonfield A, Kost K. Public costs from unintended pregnancies and the role of public insurance programs in paying for pregnancy-related care: national and state estimates for 2010. Guttmacher Institute. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/public-costs-of-UP-2010.pdf. Published February 2015. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(9):843–852.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: ovarian cancer. Bethesda, MD; National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/ovary.html. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: uterine cancer. Bethesda, MD; National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/corp.html. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: female breast cancer. Bethesda, MD; National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: colorectal cancer. Bethesda, MD; National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Mørch LS, Skovlund CW, Hannaford PC, Iversen L, Fielding S, Lidegaard Ø. Contemporary hormonal contraception and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2228–2239.

- Scott DM, Pearlman MD. Does hormonal contraception increase the risk of breast cancer? OBG Manag. 2018;30(2):16–17.

- Michels KA, Pfeiffer RM, Brinton LA, Trabert B. Modification of the associations between duration of oral contraceptive use and ovarian, endometrial, breast, and colorectal cancers [published online January 18, 2018]. JAMA Oncol. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.4942.

- Sedgwick P. Hazards and hazard ratios. BMJ. 2012;345:e5980.

- Bassuk SS, Manson JE. Oral contraceptives and menopausal hormone therapy: relative and attributable risks of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and other health outcomes. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(3):193–200.

- Hunter D. Oral contraceptives and the small increased risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2276–2277.

- GBD 2015 Maternal Mortality Collaborators. Global, regional, and national levels of maternal mortality, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1775–1812.

- Brown SS, Eisenberg L, eds. The best intentions: unintended pregnancy and the well-being of children and families. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 1995:50–90.

- Klein JD; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence. Adolescent pregnancy: current trends and issues. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):281–286.

- Logan C, Holcombe E, Manlove J, Ryan S; The National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy and Child Trends. The consequences of unintended childbearing. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b353/b02ae6cad716a7f64ca48b3edae63544c03e.pdf?_ga=2.149310646.1402594583.1524236972-1233479770.1524236972&_gac=1.195699992.1524237056. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Finer LB, Sonfield A. The evidence mounts on the benefits of preventing unintended pregnancy. Contraception. 2013;87(2):126–127.

- Trussell J, Henry N, Hassan F, Prezioso A, Law A, Filonenko A. Burden of unintended pregnancy in the United States: potential savings with increased use of long-acting reversible contraception. Contraception. 2013;87(2):154–161.

- Sonfield A, Kost K. Public costs from unintended pregnancies and the role of public insurance programs in paying for pregnancy and infant care: estimates for 2008. Guttmacher Institute. https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/public-costs-of-up.pdf. Published October 2013. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Forrest JD, Singh S. Public-sector savings resulting from expenditures for contraceptive services. Fam Plann Perspect. 1990;22(1):6–15.

- Sonfield A, Kost K. Public costs from unintended pregnancies and the role of public insurance programs in paying for pregnancy-related care: national and state estimates for 2010. Guttmacher Institute. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/public-costs-of-UP-2010.pdf. Published February 2015. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(9):843–852.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: ovarian cancer. Bethesda, MD; National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/ovary.html. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: uterine cancer. Bethesda, MD; National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/corp.html. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: female breast cancer. Bethesda, MD; National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: colorectal cancer. Bethesda, MD; National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html. Accessed April 20, 2018.

Early breast cancer: Patients report favorable quality of life after partial breast irradiation

In women with breast cancer undergoing breast-conserving surgery, accelerated partial breast irradiation (APBI) using multicatheter brachytherapy does not negatively affect quality of life, compared with standard whole breast irradiation, investigators have reported.

Patients reported similar quality of life scores for multicatheter brachytherapy–based APBI and whole breast irradiation in the study by the Groupe Européen de Curiethérapie of European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology (GEC-ESTRO).

Moreover, breast symptom scores were significantly worse for whole-breast radiation, Rebekka Schäfer, MD, of the department of radiation oncology at the University Hospital Würzburg (Germany) and colleagues reported in Lancet Oncology.

“This trial provides further clinical evidence that APBI with interstitial brachytherapy can be considered as an alternative treatment option after breast-conserving surgery for patients with low-risk breast cancer,” Dr. Schäfer and coauthors wrote.

In several previous studies, APBI has been shown to have clinical outcomes equivalent to those of whole breast irradiation in terms of disease recurrence, survival, and treatment side effects, they added.

The quality of life findings in the present report come from long-term follow-up of a randomized, controlled, phase 3 trial conducted at 16 European centers. This study included 1,184 women with early breast cancer randomly who, after receiving breast-conserving surgery, were assigned either to APBI that used multicatheter brachytherapy or to whole breast irradiation.

Women in the study completed validated quality of life questionnaires right before and right after radiotherapy, as well as during follow-up.

A little more than half of the women in each group completed the quality of life questionnaires after the treatment and again at follow-up, investigators said.

Global health status was stable over time in both groups, investigators reported. In the APBI group, global health status score on a scale of 0-100 was 65.6 right after the procedure and 66.2 at 5 years; similarly, scores in the whole breast irradiation group were 64.6 after radiotherapy and 66.0 at 5 years.

The only quality of life difference between arms that investigators characterized as moderately clinically relevant was in breast symptom scores, which were significantly worse in the whole breast radiation group right after radiotherapy (difference of means, 13.6; 95% CI, 9.7-17.5; P less than .0001) and at 3-month follow-up (difference of means, 12.7; 95% CI, 9.8-15.6; P less than .0001).

Emotional functioning, fatigue, and financial difficulty scores in the APBI group were “slightly better” than in the whole breast radiation group right after radiotherapy and at a 3-month follow-up, investigators reported; however, at 5 year follow-up, there were no significant differences between arms in those measures.

“Our findings show that APBI using multicatheter interstitial brachytherapy does not result in clinically significant deterioration of overall quality of life and that the different domains of quality of life after APBI were not worse in comparison with whole breast irradiation in terms of clinically relevant differences,” Dr. Schäfer and colleagues concluded in their report.

Dr. Schäfer reported no conflicts of interest. Coauthors reported disclosures outside of the submitted work including Nucletron Operations BV, Elekta Company, Merck Serono, Novocure, AstraZeneca, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, among others.

SOURCE: Schäfer R et al. Lancet Oncol. 2018 Apr 22. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30195-5.

This study by Schäfer and colleagues supports results of earlier and smaller studies showing promising quality of life results following accelerated partial breast irradiation (APBI) using multicatheter brachytherapy, according to Reshma Jagsi, MD.

“The results suggest that for quality of life, multicatheter brachytherapy-based APBI does not adversely affect outcomes, compared with whole breast irradiation,” Dr. Jagsi wrote in an editorial accompanying the article.

In previous trials, APBI using external radiation beam techniques has likewise shown favorable and promising quality of life outcomes.

There are now eagerly anticipated studies of APBI delivered primarily using external beam techniques that have included rigorous collection of quality of life outcomes, Dr. Jagsi added.

Those trials, which include RAPID and RTOG 0413/NSABP B39, will provide additional evidence to consider alongside those of the trial reported by Schäfer and colleagues on behalf of the Groupe Européen de Curiethérapie of European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology (GEC-ESTRO).

“Together with the results from the GEC-ESTRO trial, results from these trials will be meaningful to the many tens of thousands of women who undergo breast-conserving surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy each year,” Dr. Jagsi wrote.

Reshma Jagsi, MD, is with the department of radiation oncology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. These comments are derived from editorial in Lancet Oncology . Dr. Jagsi reported receiving personal fees from Amgen.

This study by Schäfer and colleagues supports results of earlier and smaller studies showing promising quality of life results following accelerated partial breast irradiation (APBI) using multicatheter brachytherapy, according to Reshma Jagsi, MD.

“The results suggest that for quality of life, multicatheter brachytherapy-based APBI does not adversely affect outcomes, compared with whole breast irradiation,” Dr. Jagsi wrote in an editorial accompanying the article.

In previous trials, APBI using external radiation beam techniques has likewise shown favorable and promising quality of life outcomes.

There are now eagerly anticipated studies of APBI delivered primarily using external beam techniques that have included rigorous collection of quality of life outcomes, Dr. Jagsi added.

Those trials, which include RAPID and RTOG 0413/NSABP B39, will provide additional evidence to consider alongside those of the trial reported by Schäfer and colleagues on behalf of the Groupe Européen de Curiethérapie of European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology (GEC-ESTRO).

“Together with the results from the GEC-ESTRO trial, results from these trials will be meaningful to the many tens of thousands of women who undergo breast-conserving surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy each year,” Dr. Jagsi wrote.

Reshma Jagsi, MD, is with the department of radiation oncology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. These comments are derived from editorial in Lancet Oncology . Dr. Jagsi reported receiving personal fees from Amgen.

This study by Schäfer and colleagues supports results of earlier and smaller studies showing promising quality of life results following accelerated partial breast irradiation (APBI) using multicatheter brachytherapy, according to Reshma Jagsi, MD.

“The results suggest that for quality of life, multicatheter brachytherapy-based APBI does not adversely affect outcomes, compared with whole breast irradiation,” Dr. Jagsi wrote in an editorial accompanying the article.

In previous trials, APBI using external radiation beam techniques has likewise shown favorable and promising quality of life outcomes.

There are now eagerly anticipated studies of APBI delivered primarily using external beam techniques that have included rigorous collection of quality of life outcomes, Dr. Jagsi added.

Those trials, which include RAPID and RTOG 0413/NSABP B39, will provide additional evidence to consider alongside those of the trial reported by Schäfer and colleagues on behalf of the Groupe Européen de Curiethérapie of European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology (GEC-ESTRO).

“Together with the results from the GEC-ESTRO trial, results from these trials will be meaningful to the many tens of thousands of women who undergo breast-conserving surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy each year,” Dr. Jagsi wrote.

Reshma Jagsi, MD, is with the department of radiation oncology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. These comments are derived from editorial in Lancet Oncology . Dr. Jagsi reported receiving personal fees from Amgen.

In women with breast cancer undergoing breast-conserving surgery, accelerated partial breast irradiation (APBI) using multicatheter brachytherapy does not negatively affect quality of life, compared with standard whole breast irradiation, investigators have reported.

Patients reported similar quality of life scores for multicatheter brachytherapy–based APBI and whole breast irradiation in the study by the Groupe Européen de Curiethérapie of European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology (GEC-ESTRO).

Moreover, breast symptom scores were significantly worse for whole-breast radiation, Rebekka Schäfer, MD, of the department of radiation oncology at the University Hospital Würzburg (Germany) and colleagues reported in Lancet Oncology.

“This trial provides further clinical evidence that APBI with interstitial brachytherapy can be considered as an alternative treatment option after breast-conserving surgery for patients with low-risk breast cancer,” Dr. Schäfer and coauthors wrote.

In several previous studies, APBI has been shown to have clinical outcomes equivalent to those of whole breast irradiation in terms of disease recurrence, survival, and treatment side effects, they added.

The quality of life findings in the present report come from long-term follow-up of a randomized, controlled, phase 3 trial conducted at 16 European centers. This study included 1,184 women with early breast cancer randomly who, after receiving breast-conserving surgery, were assigned either to APBI that used multicatheter brachytherapy or to whole breast irradiation.

Women in the study completed validated quality of life questionnaires right before and right after radiotherapy, as well as during follow-up.

A little more than half of the women in each group completed the quality of life questionnaires after the treatment and again at follow-up, investigators said.

Global health status was stable over time in both groups, investigators reported. In the APBI group, global health status score on a scale of 0-100 was 65.6 right after the procedure and 66.2 at 5 years; similarly, scores in the whole breast irradiation group were 64.6 after radiotherapy and 66.0 at 5 years.

The only quality of life difference between arms that investigators characterized as moderately clinically relevant was in breast symptom scores, which were significantly worse in the whole breast radiation group right after radiotherapy (difference of means, 13.6; 95% CI, 9.7-17.5; P less than .0001) and at 3-month follow-up (difference of means, 12.7; 95% CI, 9.8-15.6; P less than .0001).

Emotional functioning, fatigue, and financial difficulty scores in the APBI group were “slightly better” than in the whole breast radiation group right after radiotherapy and at a 3-month follow-up, investigators reported; however, at 5 year follow-up, there were no significant differences between arms in those measures.

“Our findings show that APBI using multicatheter interstitial brachytherapy does not result in clinically significant deterioration of overall quality of life and that the different domains of quality of life after APBI were not worse in comparison with whole breast irradiation in terms of clinically relevant differences,” Dr. Schäfer and colleagues concluded in their report.

Dr. Schäfer reported no conflicts of interest. Coauthors reported disclosures outside of the submitted work including Nucletron Operations BV, Elekta Company, Merck Serono, Novocure, AstraZeneca, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, among others.

SOURCE: Schäfer R et al. Lancet Oncol. 2018 Apr 22. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30195-5.

In women with breast cancer undergoing breast-conserving surgery, accelerated partial breast irradiation (APBI) using multicatheter brachytherapy does not negatively affect quality of life, compared with standard whole breast irradiation, investigators have reported.

Patients reported similar quality of life scores for multicatheter brachytherapy–based APBI and whole breast irradiation in the study by the Groupe Européen de Curiethérapie of European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology (GEC-ESTRO).

Moreover, breast symptom scores were significantly worse for whole-breast radiation, Rebekka Schäfer, MD, of the department of radiation oncology at the University Hospital Würzburg (Germany) and colleagues reported in Lancet Oncology.

“This trial provides further clinical evidence that APBI with interstitial brachytherapy can be considered as an alternative treatment option after breast-conserving surgery for patients with low-risk breast cancer,” Dr. Schäfer and coauthors wrote.

In several previous studies, APBI has been shown to have clinical outcomes equivalent to those of whole breast irradiation in terms of disease recurrence, survival, and treatment side effects, they added.

The quality of life findings in the present report come from long-term follow-up of a randomized, controlled, phase 3 trial conducted at 16 European centers. This study included 1,184 women with early breast cancer randomly who, after receiving breast-conserving surgery, were assigned either to APBI that used multicatheter brachytherapy or to whole breast irradiation.

Women in the study completed validated quality of life questionnaires right before and right after radiotherapy, as well as during follow-up.

A little more than half of the women in each group completed the quality of life questionnaires after the treatment and again at follow-up, investigators said.

Global health status was stable over time in both groups, investigators reported. In the APBI group, global health status score on a scale of 0-100 was 65.6 right after the procedure and 66.2 at 5 years; similarly, scores in the whole breast irradiation group were 64.6 after radiotherapy and 66.0 at 5 years.

The only quality of life difference between arms that investigators characterized as moderately clinically relevant was in breast symptom scores, which were significantly worse in the whole breast radiation group right after radiotherapy (difference of means, 13.6; 95% CI, 9.7-17.5; P less than .0001) and at 3-month follow-up (difference of means, 12.7; 95% CI, 9.8-15.6; P less than .0001).

Emotional functioning, fatigue, and financial difficulty scores in the APBI group were “slightly better” than in the whole breast radiation group right after radiotherapy and at a 3-month follow-up, investigators reported; however, at 5 year follow-up, there were no significant differences between arms in those measures.

“Our findings show that APBI using multicatheter interstitial brachytherapy does not result in clinically significant deterioration of overall quality of life and that the different domains of quality of life after APBI were not worse in comparison with whole breast irradiation in terms of clinically relevant differences,” Dr. Schäfer and colleagues concluded in their report.

Dr. Schäfer reported no conflicts of interest. Coauthors reported disclosures outside of the submitted work including Nucletron Operations BV, Elekta Company, Merck Serono, Novocure, AstraZeneca, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, among others.

SOURCE: Schäfer R et al. Lancet Oncol. 2018 Apr 22. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30195-5.

FROM LANCET ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Quality of life results support the use of accelerated partial breast irradiation (APBI) using multicatheter brachytherapy as an alternative to whole breast radiation after breast-conserving surgery.

Major finding: Patients reported similar quality of life scores for the two modalities, while breast symptom scores for whole breast radiation were significantly worse right after radiotherapy (difference of means, 13.6; 95% confidence interval, 9.7-17.5; P less than .0001) and at 3-month follow-up (difference of means, 12.7; 95% CI, 9.8-15.6; P less than .0001), compared with those for APBI.

Study details: 5-year quality of life results from a European phase 3 trial including 1,184 women with early breast cancer who, after undergoing breast-conserving surgery, received either whole breast irradiation or APBI using multicatheter brachytherapy.

Disclosures: Authors reported disclosures outside of the submitted work including Nucletron Operations BV, Elekta Company, Merck Serono, Novocure, AstraZeneca, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, among others.

Source: Schäfer R et al. Lancet Oncol. 2018 Apr 22. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30195-5.

Hormone therapy raises diabetes risk in breast cancer survivors

Hormone therapy for breast cancer more than doubles a woman’s risk for developing type 2 diabetes, results of a case-cohort study suggest.

Hormone therapy with tamoxifen was associated with a more than twofold increase in risk of diabetes, and aromatase inhibitors were associated with a more than fourfold increase, reported Hatem Hamood, MD, of Leumit Health Services in Karmiel, Israel, and colleagues.

Among 2,246 women with breast cancer and no diabetes at baseline, followed for a mean of 5.9 years (longest follow-up 13 years), the crude cumulative lifetime incidence rate of diabetes was 20.9%, the investigators wrote. The report was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“[Hormone therapy] is a significant risk factor of diabetes among breast cancer survivors. The underlying mechanism is unclear, and additional research is warranted. Although cessation of treatment is not recommended and progression of breast cancer often is inevitable, devised strategies aimed at lifestyle modifications in patients at high risk of diabetes could at least preserve the natural history of breast cancer,” they wrote.

Diabetes has previously been identified as a possible risk factor for breast cancer, but the potential for breast cancer therapy as a precipitating factor for diabetes is uncertain, the authors said.

“Given the detrimental impact of diabetes on breast cancer survival, additional exploration of the role of breast cancer treatment in the development of diabetes is important not only because it would add valuable information on the etiology of diabetes but also because it would help to identify high-risk patients in need of accentuated clinical care,” they wrote.

To explore the possible association between hormone therapy and diabetes risk, the investigators performed a retrospective case-cohort study of 2,246 women who had been diagnosed with primary nonmetastatic breast cancer treated with hormone therapy from 2002 through 2012.

They examined data on a randomly selected cohort of 448 breast cancer survivors and all patients in the parent (no diabetes at baseline) cohort who developed diabetes during the study period (324 patients).

They found that the prevalence of diabetes among their source population of 2,644 breast cancer survivors (including those with baseline diabetes) increased “drastically” from 6% in 2002 to 28% in 2015. The prevalence exceeded Israeli national norms from 2010 through 2013, with standardized prevalence ratios of 1.61 to 1.81 (P less than .001).

As noted, in the population without baseline diabetes, the crude cumulative incidence rate of diabetes in the presence of death as a competing risk factor was 20.9%.

In multivariate analyses controlling for demographic and socioeconomic factors, and for chemotherapy type, hypertension, outpatient visits, use of corticosteroids, thiazide diuretics, beta-blockers, statins, and year of breast cancer diagnosis, factors significantly associated with diabetes risk were use of hormone therapy (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 2.40, P = .008), tamoxifen (aHR 2.25, P = .013), aromatase inhibitors (aHR 4.27, P = .013), therapy duration more than 1 year (aHR 2.36, P = .009), and 1 year or less (aHR 6.48, P = .004).

The investigators noted that although other reports have found no association between aromatase inhibitors and diabetes risk, those studies had small samples or offered no explanation of the lack of association.

In contrast, a 2016 joint ACS/ASCO breast cancer survivorship-care guideline notes that aromatase inhibitors may raise the risk of diabetes, the investigators noted.

The study was supported by grants from the Israeli Council for Higher Education. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hamood H et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Apr 24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.3524.

Hormone therapy for breast cancer more than doubles a woman’s risk for developing type 2 diabetes, results of a case-cohort study suggest.

Hormone therapy with tamoxifen was associated with a more than twofold increase in risk of diabetes, and aromatase inhibitors were associated with a more than fourfold increase, reported Hatem Hamood, MD, of Leumit Health Services in Karmiel, Israel, and colleagues.

Among 2,246 women with breast cancer and no diabetes at baseline, followed for a mean of 5.9 years (longest follow-up 13 years), the crude cumulative lifetime incidence rate of diabetes was 20.9%, the investigators wrote. The report was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“[Hormone therapy] is a significant risk factor of diabetes among breast cancer survivors. The underlying mechanism is unclear, and additional research is warranted. Although cessation of treatment is not recommended and progression of breast cancer often is inevitable, devised strategies aimed at lifestyle modifications in patients at high risk of diabetes could at least preserve the natural history of breast cancer,” they wrote.

Diabetes has previously been identified as a possible risk factor for breast cancer, but the potential for breast cancer therapy as a precipitating factor for diabetes is uncertain, the authors said.

“Given the detrimental impact of diabetes on breast cancer survival, additional exploration of the role of breast cancer treatment in the development of diabetes is important not only because it would add valuable information on the etiology of diabetes but also because it would help to identify high-risk patients in need of accentuated clinical care,” they wrote.

To explore the possible association between hormone therapy and diabetes risk, the investigators performed a retrospective case-cohort study of 2,246 women who had been diagnosed with primary nonmetastatic breast cancer treated with hormone therapy from 2002 through 2012.

They examined data on a randomly selected cohort of 448 breast cancer survivors and all patients in the parent (no diabetes at baseline) cohort who developed diabetes during the study period (324 patients).

They found that the prevalence of diabetes among their source population of 2,644 breast cancer survivors (including those with baseline diabetes) increased “drastically” from 6% in 2002 to 28% in 2015. The prevalence exceeded Israeli national norms from 2010 through 2013, with standardized prevalence ratios of 1.61 to 1.81 (P less than .001).

As noted, in the population without baseline diabetes, the crude cumulative incidence rate of diabetes in the presence of death as a competing risk factor was 20.9%.

In multivariate analyses controlling for demographic and socioeconomic factors, and for chemotherapy type, hypertension, outpatient visits, use of corticosteroids, thiazide diuretics, beta-blockers, statins, and year of breast cancer diagnosis, factors significantly associated with diabetes risk were use of hormone therapy (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 2.40, P = .008), tamoxifen (aHR 2.25, P = .013), aromatase inhibitors (aHR 4.27, P = .013), therapy duration more than 1 year (aHR 2.36, P = .009), and 1 year or less (aHR 6.48, P = .004).

The investigators noted that although other reports have found no association between aromatase inhibitors and diabetes risk, those studies had small samples or offered no explanation of the lack of association.

In contrast, a 2016 joint ACS/ASCO breast cancer survivorship-care guideline notes that aromatase inhibitors may raise the risk of diabetes, the investigators noted.

The study was supported by grants from the Israeli Council for Higher Education. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hamood H et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Apr 24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.3524.

Hormone therapy for breast cancer more than doubles a woman’s risk for developing type 2 diabetes, results of a case-cohort study suggest.

Hormone therapy with tamoxifen was associated with a more than twofold increase in risk of diabetes, and aromatase inhibitors were associated with a more than fourfold increase, reported Hatem Hamood, MD, of Leumit Health Services in Karmiel, Israel, and colleagues.

Among 2,246 women with breast cancer and no diabetes at baseline, followed for a mean of 5.9 years (longest follow-up 13 years), the crude cumulative lifetime incidence rate of diabetes was 20.9%, the investigators wrote. The report was published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“[Hormone therapy] is a significant risk factor of diabetes among breast cancer survivors. The underlying mechanism is unclear, and additional research is warranted. Although cessation of treatment is not recommended and progression of breast cancer often is inevitable, devised strategies aimed at lifestyle modifications in patients at high risk of diabetes could at least preserve the natural history of breast cancer,” they wrote.

Diabetes has previously been identified as a possible risk factor for breast cancer, but the potential for breast cancer therapy as a precipitating factor for diabetes is uncertain, the authors said.

“Given the detrimental impact of diabetes on breast cancer survival, additional exploration of the role of breast cancer treatment in the development of diabetes is important not only because it would add valuable information on the etiology of diabetes but also because it would help to identify high-risk patients in need of accentuated clinical care,” they wrote.

To explore the possible association between hormone therapy and diabetes risk, the investigators performed a retrospective case-cohort study of 2,246 women who had been diagnosed with primary nonmetastatic breast cancer treated with hormone therapy from 2002 through 2012.

They examined data on a randomly selected cohort of 448 breast cancer survivors and all patients in the parent (no diabetes at baseline) cohort who developed diabetes during the study period (324 patients).

They found that the prevalence of diabetes among their source population of 2,644 breast cancer survivors (including those with baseline diabetes) increased “drastically” from 6% in 2002 to 28% in 2015. The prevalence exceeded Israeli national norms from 2010 through 2013, with standardized prevalence ratios of 1.61 to 1.81 (P less than .001).

As noted, in the population without baseline diabetes, the crude cumulative incidence rate of diabetes in the presence of death as a competing risk factor was 20.9%.

In multivariate analyses controlling for demographic and socioeconomic factors, and for chemotherapy type, hypertension, outpatient visits, use of corticosteroids, thiazide diuretics, beta-blockers, statins, and year of breast cancer diagnosis, factors significantly associated with diabetes risk were use of hormone therapy (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 2.40, P = .008), tamoxifen (aHR 2.25, P = .013), aromatase inhibitors (aHR 4.27, P = .013), therapy duration more than 1 year (aHR 2.36, P = .009), and 1 year or less (aHR 6.48, P = .004).

The investigators noted that although other reports have found no association between aromatase inhibitors and diabetes risk, those studies had small samples or offered no explanation of the lack of association.

In contrast, a 2016 joint ACS/ASCO breast cancer survivorship-care guideline notes that aromatase inhibitors may raise the risk of diabetes, the investigators noted.

The study was supported by grants from the Israeli Council for Higher Education. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Hamood H et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Apr 24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.3524.

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Consider screening survivors of nonmetastatic breast cancer for diabetes.

Major finding: The crude lifetime incidence of diabetes following hormone therapy for breast cancer was 20.9%.

Study details: Case-cohort study of 2,246 women with nonmetastatic breast cancer and no baseline diabetes treated with hormone therapy.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grants from the Israeli Council for Higher Education. The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Hamood H et al. J Clin Oncol. 2018 Apr 24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.3524.

OlympiAD: No statistically significant boost in OS with olaparib in HER2-negative mBC

CHICAGO – Median overall survival (OS) in patients with HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer (mBC) and germline BRCA mutation (gBRCAm), although not statistically significant, was 2.2 months longer with olaparib versus physician’s choice chemotherapy (TPC), according to the final analysis of the OlympiAD study.

The results suggested the possibility of greater benefit among chemotherapy naive patients for metastatic breast cancer, with no cumulative toxicity reported with extended exposure, Mark E. Robson, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research.

OlympiAD was a randomized, controlled, open-label, multicenter, phase 3 study of olaparib tablet monotherapy (300 mg, twice daily) compared with predeclared TPC monotherapy (capecitabine, vinorelbine, or eribulin). Patients were stratified by prior chemotherapy, prior platinum, and receptor status (ER+ and/or PR+ vs. TNBC). Of 302 randomized patients, 205 received olaparib and 91 received TPC (6 TPC patients declined treatment). Eligible patients had HER2-negative mBC and a germline BRCA mutation. In addition, patients should have received less than or equal to two chemotherapy lines in the metastatic setting, with prior anthracycline and taxane treatment either as (neo)adjuvant therapy or in the metastatic setting.

The data presented at AACR was a follow-up on the primary progression-free survival (PFS) analysis, which demonstrated significant benefit in olaparib over standard chemotherapy TPC (7.0 vs 4.2 months, HR 0.58, 95% confidence interval, 0.43-0.80, P less than .001). Overall response rate (ORR) in the olaparib arm was double of that observed on the TPC arm in measurable disease patients (59.9% vs. 28.8%).

At the final OS analysis with 192 deaths, HR for OS in the olaparib vs TPC group was 0.90 (95% CI, 0.66-1.23; P = .513), reported Dr. Robson of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York.

“The preplanned subgroup analyses according to the stratification factors were not powered to detect survival advantages, and were considered only hypothesis generating,” he said.

In patients who had not received chemotherapy in the metastatic setting, there was a median difference in OS of 7.9 months with olaparib (HR 0.51, 95% CI, 0.29-0.90; nominal P = .02; median 22.6 vs. 14.7 months).

Median follow-up for OS was 18.9 months for olaparib vs. 15.5 months in the TPC group.

No differences were observed between patients that were ER and/or PgR positive vs. TNBC, or whether patients received prior platinum, Dr. Robson said.

Grade 3 adverse events were similar to those in the primary analysis with no cumulative toxicity with extended exposure, he said.

SOURCE: Robson ME et al. AACR Annual Meeting Abstract CT038.

CHICAGO – Median overall survival (OS) in patients with HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer (mBC) and germline BRCA mutation (gBRCAm), although not statistically significant, was 2.2 months longer with olaparib versus physician’s choice chemotherapy (TPC), according to the final analysis of the OlympiAD study.

The results suggested the possibility of greater benefit among chemotherapy naive patients for metastatic breast cancer, with no cumulative toxicity reported with extended exposure, Mark E. Robson, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research.

OlympiAD was a randomized, controlled, open-label, multicenter, phase 3 study of olaparib tablet monotherapy (300 mg, twice daily) compared with predeclared TPC monotherapy (capecitabine, vinorelbine, or eribulin). Patients were stratified by prior chemotherapy, prior platinum, and receptor status (ER+ and/or PR+ vs. TNBC). Of 302 randomized patients, 205 received olaparib and 91 received TPC (6 TPC patients declined treatment). Eligible patients had HER2-negative mBC and a germline BRCA mutation. In addition, patients should have received less than or equal to two chemotherapy lines in the metastatic setting, with prior anthracycline and taxane treatment either as (neo)adjuvant therapy or in the metastatic setting.

The data presented at AACR was a follow-up on the primary progression-free survival (PFS) analysis, which demonstrated significant benefit in olaparib over standard chemotherapy TPC (7.0 vs 4.2 months, HR 0.58, 95% confidence interval, 0.43-0.80, P less than .001). Overall response rate (ORR) in the olaparib arm was double of that observed on the TPC arm in measurable disease patients (59.9% vs. 28.8%).

At the final OS analysis with 192 deaths, HR for OS in the olaparib vs TPC group was 0.90 (95% CI, 0.66-1.23; P = .513), reported Dr. Robson of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York.

“The preplanned subgroup analyses according to the stratification factors were not powered to detect survival advantages, and were considered only hypothesis generating,” he said.

In patients who had not received chemotherapy in the metastatic setting, there was a median difference in OS of 7.9 months with olaparib (HR 0.51, 95% CI, 0.29-0.90; nominal P = .02; median 22.6 vs. 14.7 months).

Median follow-up for OS was 18.9 months for olaparib vs. 15.5 months in the TPC group.

No differences were observed between patients that were ER and/or PgR positive vs. TNBC, or whether patients received prior platinum, Dr. Robson said.

Grade 3 adverse events were similar to those in the primary analysis with no cumulative toxicity with extended exposure, he said.

SOURCE: Robson ME et al. AACR Annual Meeting Abstract CT038.

CHICAGO – Median overall survival (OS) in patients with HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer (mBC) and germline BRCA mutation (gBRCAm), although not statistically significant, was 2.2 months longer with olaparib versus physician’s choice chemotherapy (TPC), according to the final analysis of the OlympiAD study.

The results suggested the possibility of greater benefit among chemotherapy naive patients for metastatic breast cancer, with no cumulative toxicity reported with extended exposure, Mark E. Robson, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research.

OlympiAD was a randomized, controlled, open-label, multicenter, phase 3 study of olaparib tablet monotherapy (300 mg, twice daily) compared with predeclared TPC monotherapy (capecitabine, vinorelbine, or eribulin). Patients were stratified by prior chemotherapy, prior platinum, and receptor status (ER+ and/or PR+ vs. TNBC). Of 302 randomized patients, 205 received olaparib and 91 received TPC (6 TPC patients declined treatment). Eligible patients had HER2-negative mBC and a germline BRCA mutation. In addition, patients should have received less than or equal to two chemotherapy lines in the metastatic setting, with prior anthracycline and taxane treatment either as (neo)adjuvant therapy or in the metastatic setting.

The data presented at AACR was a follow-up on the primary progression-free survival (PFS) analysis, which demonstrated significant benefit in olaparib over standard chemotherapy TPC (7.0 vs 4.2 months, HR 0.58, 95% confidence interval, 0.43-0.80, P less than .001). Overall response rate (ORR) in the olaparib arm was double of that observed on the TPC arm in measurable disease patients (59.9% vs. 28.8%).

At the final OS analysis with 192 deaths, HR for OS in the olaparib vs TPC group was 0.90 (95% CI, 0.66-1.23; P = .513), reported Dr. Robson of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York.

“The preplanned subgroup analyses according to the stratification factors were not powered to detect survival advantages, and were considered only hypothesis generating,” he said.

In patients who had not received chemotherapy in the metastatic setting, there was a median difference in OS of 7.9 months with olaparib (HR 0.51, 95% CI, 0.29-0.90; nominal P = .02; median 22.6 vs. 14.7 months).

Median follow-up for OS was 18.9 months for olaparib vs. 15.5 months in the TPC group.

No differences were observed between patients that were ER and/or PgR positive vs. TNBC, or whether patients received prior platinum, Dr. Robson said.

Grade 3 adverse events were similar to those in the primary analysis with no cumulative toxicity with extended exposure, he said.

SOURCE: Robson ME et al. AACR Annual Meeting Abstract CT038.

FROM THE AACR ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Median overall survival was not significantly different with olaparib versus chemotherapy in patients with BRCA-mutated, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer.

Major finding: Median overall survival in patients with HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer and a germline BRCA mutation was 19.3 months versus 17.1 months for olaparib versus chemotherapy (HR 0.90 95% CI 0.66, 1.23; P = .513).

Study details: Randomized, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial (OlympiAD) of olaparib tablet monotherapy (300 mg, twice daily) compared with predeclared physician’s choice chemotherapy (capecitabine, vinorelbine, or eribulin).

Disclosures: Dr. Robson disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, AbbVie, McKesson, Myriad Genetics, and Medivation.

Source: Robson ME et al. AACR Annual Meeting Abstract CT038.