User login

Rural Cancer Survivors Are More Likely to Have Chronic Pain

TOPLINE:

Rural cancer survivors experience significantly higher rates of chronic pain at 43.0% than those among urban survivors at 33.5%. Even after controlling for demographics and health conditions, rural residents showed 21% higher odds of experiencing chronic pain.

METHODOLOGY:

- Chronic pain prevalence among cancer survivors is twice that of the general US population and is associated with numerous negative outcomes. Rural residence is frequently linked to debilitating long-term survivorship effects, and current data lack information on whether chronic pain disparity exists specifically for rural cancer survivors.

- Researchers pooled data from the 2019–2021 and 2023 National Health Interview Survey, a cross–sectional survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics.

- Analysis included 5542 adult cancer survivors diagnosed within the previous 5 years, with 51.6% female participants and 48.4% male participants.

- Chronic pain was defined as pain experienced on most or all days over the past 3 months, following National Center for Health Statistics conventions.

- Rural residence classification was based on noncore or nonmetropolitan counties using the modified National Center for Health Statistics Urban–Rural Classification Scheme for Counties.

TAKEAWAY:

- Rural cancer survivors showed significantly higher odds of experiencing chronic pain compared with urban survivors (odds ratio [OR], 1.21; 95% CI, 1.01-1.45).

- Rural survivors were more likely to be non–Hispanic White, have less than a 4-year college degree, have an income below 200% of the federal poverty level, and have slightly more chronic health conditions.

- Having an income below 100% of the federal poverty level was associated with doubled odds of chronic pain (OR, 2.07; 95% CI, 1.54-2.77) compared with having an income at least four times the federal poverty level.

- Each additional health condition increased the odds of experiencing chronic pain by 32% (OR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.26-1.39).

IN PRACTICE:

“Policymakers and health systems should work to close this gap by increasing the availability of pain management resources for rural cancer survivors. Approaches could include innovative payment models for integrative medicine in rural areas or supporting rural clinician access to pain specialists,” the authors of the study wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Hyojin Choi, PhD, Department of Family Medicine, The Robert Larner MD College of Medicine, University of Vermont in Burlington, Vermont. It was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors note that the cross–sectional design of the study and limited information on individual respondents’ use of multimodal pain treatment options constrain the interpretation of findings.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors did not report any relevant conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Rural cancer survivors experience significantly higher rates of chronic pain at 43.0% than those among urban survivors at 33.5%. Even after controlling for demographics and health conditions, rural residents showed 21% higher odds of experiencing chronic pain.

METHODOLOGY:

- Chronic pain prevalence among cancer survivors is twice that of the general US population and is associated with numerous negative outcomes. Rural residence is frequently linked to debilitating long-term survivorship effects, and current data lack information on whether chronic pain disparity exists specifically for rural cancer survivors.

- Researchers pooled data from the 2019–2021 and 2023 National Health Interview Survey, a cross–sectional survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics.

- Analysis included 5542 adult cancer survivors diagnosed within the previous 5 years, with 51.6% female participants and 48.4% male participants.

- Chronic pain was defined as pain experienced on most or all days over the past 3 months, following National Center for Health Statistics conventions.

- Rural residence classification was based on noncore or nonmetropolitan counties using the modified National Center for Health Statistics Urban–Rural Classification Scheme for Counties.

TAKEAWAY:

- Rural cancer survivors showed significantly higher odds of experiencing chronic pain compared with urban survivors (odds ratio [OR], 1.21; 95% CI, 1.01-1.45).

- Rural survivors were more likely to be non–Hispanic White, have less than a 4-year college degree, have an income below 200% of the federal poverty level, and have slightly more chronic health conditions.

- Having an income below 100% of the federal poverty level was associated with doubled odds of chronic pain (OR, 2.07; 95% CI, 1.54-2.77) compared with having an income at least four times the federal poverty level.

- Each additional health condition increased the odds of experiencing chronic pain by 32% (OR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.26-1.39).

IN PRACTICE:

“Policymakers and health systems should work to close this gap by increasing the availability of pain management resources for rural cancer survivors. Approaches could include innovative payment models for integrative medicine in rural areas or supporting rural clinician access to pain specialists,” the authors of the study wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Hyojin Choi, PhD, Department of Family Medicine, The Robert Larner MD College of Medicine, University of Vermont in Burlington, Vermont. It was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors note that the cross–sectional design of the study and limited information on individual respondents’ use of multimodal pain treatment options constrain the interpretation of findings.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors did not report any relevant conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Rural cancer survivors experience significantly higher rates of chronic pain at 43.0% than those among urban survivors at 33.5%. Even after controlling for demographics and health conditions, rural residents showed 21% higher odds of experiencing chronic pain.

METHODOLOGY:

- Chronic pain prevalence among cancer survivors is twice that of the general US population and is associated with numerous negative outcomes. Rural residence is frequently linked to debilitating long-term survivorship effects, and current data lack information on whether chronic pain disparity exists specifically for rural cancer survivors.

- Researchers pooled data from the 2019–2021 and 2023 National Health Interview Survey, a cross–sectional survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics.

- Analysis included 5542 adult cancer survivors diagnosed within the previous 5 years, with 51.6% female participants and 48.4% male participants.

- Chronic pain was defined as pain experienced on most or all days over the past 3 months, following National Center for Health Statistics conventions.

- Rural residence classification was based on noncore or nonmetropolitan counties using the modified National Center for Health Statistics Urban–Rural Classification Scheme for Counties.

TAKEAWAY:

- Rural cancer survivors showed significantly higher odds of experiencing chronic pain compared with urban survivors (odds ratio [OR], 1.21; 95% CI, 1.01-1.45).

- Rural survivors were more likely to be non–Hispanic White, have less than a 4-year college degree, have an income below 200% of the federal poverty level, and have slightly more chronic health conditions.

- Having an income below 100% of the federal poverty level was associated with doubled odds of chronic pain (OR, 2.07; 95% CI, 1.54-2.77) compared with having an income at least four times the federal poverty level.

- Each additional health condition increased the odds of experiencing chronic pain by 32% (OR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.26-1.39).

IN PRACTICE:

“Policymakers and health systems should work to close this gap by increasing the availability of pain management resources for rural cancer survivors. Approaches could include innovative payment models for integrative medicine in rural areas or supporting rural clinician access to pain specialists,” the authors of the study wrote.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Hyojin Choi, PhD, Department of Family Medicine, The Robert Larner MD College of Medicine, University of Vermont in Burlington, Vermont. It was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors note that the cross–sectional design of the study and limited information on individual respondents’ use of multimodal pain treatment options constrain the interpretation of findings.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors did not report any relevant conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

NICE Endorses Chemo-Free First-Line Options for EGFR NSCLC

NICE Endorses Chemo-Free First-Line Options for EGFR NSCLC

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has recommended amivantamab (Rybrevant) plus lazertinib (Lazcluze) as a first-line option for adults with previously untreated advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) exon 19 deletions or exon 21 L858R substitution mutations.

In final draft guidance, NICE said the combination therapy should be funded by the NHS in England for eligible patients when it is the most appropriate option. Around 1115 people are expected to benefit.

Lung cancer is the third most common cancer and the leading cause of cancer mortality in the UK. It accounted for 10% of all new cancer diagnoses and 20% of cancer deaths in 2020. Approximately 31,000 people received NSCLC diagnoses in England in 2021, comprising 91% of all lung cancer cases. EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC is more common in women, non-smokers, and individuals from Asian ethnic backgrounds.

Welcoming the decision, Virginia Harrison, research trustee, EGFR+ UK, said, “This is a meaningful advance for patients and their families facing this diagnosis. [It] provides something the EGFR community urgently needs: more choice in first-line treatment.”

How Practice May Shift

The recommendation adds an alternative to existing standards, including osimertinib monotherapy or osimertinib plus pemetrexed/platinum-based chemotherapy. Clinical specialists noted that no single standard care exists for this patient group.

Younger patients and those willing to accept greater side effects may choose between amivantamab plus lazertinib or osimertinib plus chemotherapy. Patients older than 80 years might prefer osimertinib monotherapy due to adverse event considerations.

Mechanism of Action and Clinical Evidence

Amivantamab is a bispecific antibody that simultaneously binds EGFR and mesenchymal-epithelial transition receptors, blocking downstream signaling pathways that drive tumor growth and promoting immune-mediated cancer cell killing. Lazertinib is an oral third-generation EGFR TKI that selectively inhibits mutant EGFR signaling. Together, the agents provides complementary suppression of EGFR-driven tumour growth and resistance mechanisms.

The NICE recommendation is supported by results from the phase 3 MARIPOSA trial, which met its primary endpoint of progression-free survival (PFS). Treatment with amivantamab plus lazertinib significantly prolonged median PFS to 23.7 months compared with 16.6 months with osimertinib. The combination also demonstrated a significant improvement in overall survival, reducing the risk for death by 25% vs osimertinib. Median OS was not reached in the combination arm and was 36.7 months with osimertinib.

The most common adverse reactions with the combination included rash, nail toxicity, hypoalbuminaemia, hepatotoxicity, and stomatitis.

A Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency-approved subcutaneous formulation of amivantamab, authorized after the committee’s initial meeting, may further improve tolerability and convenience. Administration-related reactions occurred in 63% of patients with the intravenous formulation vs 14% with the subcutaneous formulation. Clinicians expect subcutaneous dosing to replace intravenous use in practice.

Dosing, Access, and Implementation

Amivantamab is administered every 2 weeks, either intravenously or subcutaneously. Lazertinib is taken as a daily oral tablet.

Rybrevant costs £1079 for a 350-mg per 7-mL vial. Lazcluze is priced at £4128.50 for 56 x 80-mg tablets and £6192.75 for 28 x 240-mg tablets. Confidential NHS discounts are available through simple patient access schemes.

Integrated care boards, NHS England, and local authorities must implement the guidance within 90 days of publication. For drugs receiving positive draft recommendations for routine commissioning, interim funding becomes accessible from the Cancer Drugs Fund budget starting from the point of marketing authorisation or publication of draft guidance.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has recommended amivantamab (Rybrevant) plus lazertinib (Lazcluze) as a first-line option for adults with previously untreated advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) exon 19 deletions or exon 21 L858R substitution mutations.

In final draft guidance, NICE said the combination therapy should be funded by the NHS in England for eligible patients when it is the most appropriate option. Around 1115 people are expected to benefit.

Lung cancer is the third most common cancer and the leading cause of cancer mortality in the UK. It accounted for 10% of all new cancer diagnoses and 20% of cancer deaths in 2020. Approximately 31,000 people received NSCLC diagnoses in England in 2021, comprising 91% of all lung cancer cases. EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC is more common in women, non-smokers, and individuals from Asian ethnic backgrounds.

Welcoming the decision, Virginia Harrison, research trustee, EGFR+ UK, said, “This is a meaningful advance for patients and their families facing this diagnosis. [It] provides something the EGFR community urgently needs: more choice in first-line treatment.”

How Practice May Shift

The recommendation adds an alternative to existing standards, including osimertinib monotherapy or osimertinib plus pemetrexed/platinum-based chemotherapy. Clinical specialists noted that no single standard care exists for this patient group.

Younger patients and those willing to accept greater side effects may choose between amivantamab plus lazertinib or osimertinib plus chemotherapy. Patients older than 80 years might prefer osimertinib monotherapy due to adverse event considerations.

Mechanism of Action and Clinical Evidence

Amivantamab is a bispecific antibody that simultaneously binds EGFR and mesenchymal-epithelial transition receptors, blocking downstream signaling pathways that drive tumor growth and promoting immune-mediated cancer cell killing. Lazertinib is an oral third-generation EGFR TKI that selectively inhibits mutant EGFR signaling. Together, the agents provides complementary suppression of EGFR-driven tumour growth and resistance mechanisms.

The NICE recommendation is supported by results from the phase 3 MARIPOSA trial, which met its primary endpoint of progression-free survival (PFS). Treatment with amivantamab plus lazertinib significantly prolonged median PFS to 23.7 months compared with 16.6 months with osimertinib. The combination also demonstrated a significant improvement in overall survival, reducing the risk for death by 25% vs osimertinib. Median OS was not reached in the combination arm and was 36.7 months with osimertinib.

The most common adverse reactions with the combination included rash, nail toxicity, hypoalbuminaemia, hepatotoxicity, and stomatitis.

A Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency-approved subcutaneous formulation of amivantamab, authorized after the committee’s initial meeting, may further improve tolerability and convenience. Administration-related reactions occurred in 63% of patients with the intravenous formulation vs 14% with the subcutaneous formulation. Clinicians expect subcutaneous dosing to replace intravenous use in practice.

Dosing, Access, and Implementation

Amivantamab is administered every 2 weeks, either intravenously or subcutaneously. Lazertinib is taken as a daily oral tablet.

Rybrevant costs £1079 for a 350-mg per 7-mL vial. Lazcluze is priced at £4128.50 for 56 x 80-mg tablets and £6192.75 for 28 x 240-mg tablets. Confidential NHS discounts are available through simple patient access schemes.

Integrated care boards, NHS England, and local authorities must implement the guidance within 90 days of publication. For drugs receiving positive draft recommendations for routine commissioning, interim funding becomes accessible from the Cancer Drugs Fund budget starting from the point of marketing authorisation or publication of draft guidance.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has recommended amivantamab (Rybrevant) plus lazertinib (Lazcluze) as a first-line option for adults with previously untreated advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) exon 19 deletions or exon 21 L858R substitution mutations.

In final draft guidance, NICE said the combination therapy should be funded by the NHS in England for eligible patients when it is the most appropriate option. Around 1115 people are expected to benefit.

Lung cancer is the third most common cancer and the leading cause of cancer mortality in the UK. It accounted for 10% of all new cancer diagnoses and 20% of cancer deaths in 2020. Approximately 31,000 people received NSCLC diagnoses in England in 2021, comprising 91% of all lung cancer cases. EGFR mutation-positive NSCLC is more common in women, non-smokers, and individuals from Asian ethnic backgrounds.

Welcoming the decision, Virginia Harrison, research trustee, EGFR+ UK, said, “This is a meaningful advance for patients and their families facing this diagnosis. [It] provides something the EGFR community urgently needs: more choice in first-line treatment.”

How Practice May Shift

The recommendation adds an alternative to existing standards, including osimertinib monotherapy or osimertinib plus pemetrexed/platinum-based chemotherapy. Clinical specialists noted that no single standard care exists for this patient group.

Younger patients and those willing to accept greater side effects may choose between amivantamab plus lazertinib or osimertinib plus chemotherapy. Patients older than 80 years might prefer osimertinib monotherapy due to adverse event considerations.

Mechanism of Action and Clinical Evidence

Amivantamab is a bispecific antibody that simultaneously binds EGFR and mesenchymal-epithelial transition receptors, blocking downstream signaling pathways that drive tumor growth and promoting immune-mediated cancer cell killing. Lazertinib is an oral third-generation EGFR TKI that selectively inhibits mutant EGFR signaling. Together, the agents provides complementary suppression of EGFR-driven tumour growth and resistance mechanisms.

The NICE recommendation is supported by results from the phase 3 MARIPOSA trial, which met its primary endpoint of progression-free survival (PFS). Treatment with amivantamab plus lazertinib significantly prolonged median PFS to 23.7 months compared with 16.6 months with osimertinib. The combination also demonstrated a significant improvement in overall survival, reducing the risk for death by 25% vs osimertinib. Median OS was not reached in the combination arm and was 36.7 months with osimertinib.

The most common adverse reactions with the combination included rash, nail toxicity, hypoalbuminaemia, hepatotoxicity, and stomatitis.

A Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency-approved subcutaneous formulation of amivantamab, authorized after the committee’s initial meeting, may further improve tolerability and convenience. Administration-related reactions occurred in 63% of patients with the intravenous formulation vs 14% with the subcutaneous formulation. Clinicians expect subcutaneous dosing to replace intravenous use in practice.

Dosing, Access, and Implementation

Amivantamab is administered every 2 weeks, either intravenously or subcutaneously. Lazertinib is taken as a daily oral tablet.

Rybrevant costs £1079 for a 350-mg per 7-mL vial. Lazcluze is priced at £4128.50 for 56 x 80-mg tablets and £6192.75 for 28 x 240-mg tablets. Confidential NHS discounts are available through simple patient access schemes.

Integrated care boards, NHS England, and local authorities must implement the guidance within 90 days of publication. For drugs receiving positive draft recommendations for routine commissioning, interim funding becomes accessible from the Cancer Drugs Fund budget starting from the point of marketing authorisation or publication of draft guidance.

NICE Endorses Chemo-Free First-Line Options for EGFR NSCLC

NICE Endorses Chemo-Free First-Line Options for EGFR NSCLC

Turning the Cancer Research Problem Into an Opportunity

Turning the Cancer Research Problem Into an Opportunity

The War on Cancer, declared by President Richard Nixon some 50 years ago, has been canceled during the second Trump administration in 2025 — so saith The New York Times Sunday magazine cover story on September 14, 2025. This war seems now to be best described as "The War on Cancer Research."

To our horror and disbelief, we've witnessed the slow but persistent drift of much of the United States citizenry away from science and the sudden and severe movement of the US government to crush much medical research. But it is not as if we were not warned.

In August 2024, on these pages and without political bias, I urged Medscape readers to pay attention to Project 2025. A great deal of what we as a population are now experiencing was laid out as a carefully constructed plan.

What is surprising is the cruel ruthlessness of the "move fast and break things" approach, taken with little apparent concern about the resultant human tragedies (workforce and patients) and no clear care about the resulting fallout. As we've now learned, destroying something as grand as our cancer research enterprise can be accomplished very quickly. Rebuilding it is certain to be slow and difficult and perhaps can never be accomplished.

In this new anti-science, anti-research, and anti-researcher reality, what can we now do?

First and foremost, we must recognize that the war on cancer is not over. Cancer is not canceled, even if much of the US government's research effort/funding has been. Those of us in medicine and public health often speak in quantification of causes of death of our populations. As such, I'll remind Medscape readers that cancer afflicts some 20 million humans worldwide each year, killing nearly 10 million. Although two-thirds of Americans diagnosed with a potentially lethal malignancy are cured, cancer still kills roughly 600,000 Americans each year. Cancer has been the second most frequent cause of death of Americans for 75 years.

Being inevitable and immutable, death itself is not the enemy. We all die. Disease, disability, pain, and human suffering are the real enemies of us all. Cancer maims, pains, diabetes, and torments some 20 million humans worldwide each year. That is a huge humanitarian problem that should be recognized by individuals of all creeds and backgrounds.

With this depletion of our domestic government basic and applied cancer research program, what can we do?

- Think globally and look to the international scientific research enterprises — relying on them, much as they have relied on us.

- Defend the universal importance of reliable and available literature on medical science.

- Continue to translate and apply the vast amount of available published research in clinical practice and publish the results.

- Urge private industries to expand their research budgets into areas of study that may not produce quickly tangible positive bottom-line results.

- Remind the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (for whom chronic diseases seem paramount) that cancer is the second leading American chronic disease by morbidity.

- Redouble efforts of cancer prevention, especially urging the FDA to ban combustible tobacco and strive more diligently to decrease obesity.

- Appeal to our vast philanthropic universe to increase its funding of nonprofit organizations active in the cancer investigation, diagnosis, and management space.

One such 501c3 organization is California-based Cancer Commons. (Disclosure: I named it in 2010 and serve as its editor in chief).

A commons is a space shared by a community to use for the common interest. As we originally envisioned it, a cancer commons is an open access internet location where individuals and organizations (eg, corporations, universities, government agencies, philanthropies) will voluntarily share their data to work together to defeat the common enemy of humans: cancer.

On September 8, 2025, Cancer Commons was the 15th annual Lundberg Institute Lecturer at the Commonwealth Club of California in San Francisco. At the lecture, Cancer Commons founder (and long-term survivor of metastatic malignant melanoma), Jay Martin "Martin" Tenenbaum, PhD, spoke of the need for a cancer commons and the founder's vision. Emma Shtivelman, PhD, the long-time compassionate chief scientist, described some of the thousands of patients with advanced cancer that she has helped — all free of charge. And newly named CEO Clifford Reid, MBA, PhD, used his entrepreneurial prowess to envision an ambitious future.

Cancer Commons has always focused on patients with cancer who are beyond standards of curative care. As Cancer Commons evolves, it anticipates focusing on patients with cancer who are beyond National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines. The organization intends to greatly expand its 1000 patients per year with "high touch" engagement with PhD clinical scientists to many thousands by including artificial intelligence. It plans to extend its N-of-One approach to create new knowledge — especially regarding the hundreds of drugs that are FDA-approved for use in treating cancer but have not been further assessed for the utility in actually treating patients with cancer.

The war on cancer is not over. It remains a persistent foe that causes immense disability, pain, and human suffering. With government support depleted, the burden now shifts to the private sector and philanthropic organizations, such as Cancer Commons, to serve as the new vital infrastructure in the fight for a cure. Now, we must redouble our efforts to ensure that these research endeavors are supported if the US government will not do its part.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The War on Cancer, declared by President Richard Nixon some 50 years ago, has been canceled during the second Trump administration in 2025 — so saith The New York Times Sunday magazine cover story on September 14, 2025. This war seems now to be best described as "The War on Cancer Research."

To our horror and disbelief, we've witnessed the slow but persistent drift of much of the United States citizenry away from science and the sudden and severe movement of the US government to crush much medical research. But it is not as if we were not warned.

In August 2024, on these pages and without political bias, I urged Medscape readers to pay attention to Project 2025. A great deal of what we as a population are now experiencing was laid out as a carefully constructed plan.

What is surprising is the cruel ruthlessness of the "move fast and break things" approach, taken with little apparent concern about the resultant human tragedies (workforce and patients) and no clear care about the resulting fallout. As we've now learned, destroying something as grand as our cancer research enterprise can be accomplished very quickly. Rebuilding it is certain to be slow and difficult and perhaps can never be accomplished.

In this new anti-science, anti-research, and anti-researcher reality, what can we now do?

First and foremost, we must recognize that the war on cancer is not over. Cancer is not canceled, even if much of the US government's research effort/funding has been. Those of us in medicine and public health often speak in quantification of causes of death of our populations. As such, I'll remind Medscape readers that cancer afflicts some 20 million humans worldwide each year, killing nearly 10 million. Although two-thirds of Americans diagnosed with a potentially lethal malignancy are cured, cancer still kills roughly 600,000 Americans each year. Cancer has been the second most frequent cause of death of Americans for 75 years.

Being inevitable and immutable, death itself is not the enemy. We all die. Disease, disability, pain, and human suffering are the real enemies of us all. Cancer maims, pains, diabetes, and torments some 20 million humans worldwide each year. That is a huge humanitarian problem that should be recognized by individuals of all creeds and backgrounds.

With this depletion of our domestic government basic and applied cancer research program, what can we do?

- Think globally and look to the international scientific research enterprises — relying on them, much as they have relied on us.

- Defend the universal importance of reliable and available literature on medical science.

- Continue to translate and apply the vast amount of available published research in clinical practice and publish the results.

- Urge private industries to expand their research budgets into areas of study that may not produce quickly tangible positive bottom-line results.

- Remind the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (for whom chronic diseases seem paramount) that cancer is the second leading American chronic disease by morbidity.

- Redouble efforts of cancer prevention, especially urging the FDA to ban combustible tobacco and strive more diligently to decrease obesity.

- Appeal to our vast philanthropic universe to increase its funding of nonprofit organizations active in the cancer investigation, diagnosis, and management space.

One such 501c3 organization is California-based Cancer Commons. (Disclosure: I named it in 2010 and serve as its editor in chief).

A commons is a space shared by a community to use for the common interest. As we originally envisioned it, a cancer commons is an open access internet location where individuals and organizations (eg, corporations, universities, government agencies, philanthropies) will voluntarily share their data to work together to defeat the common enemy of humans: cancer.

On September 8, 2025, Cancer Commons was the 15th annual Lundberg Institute Lecturer at the Commonwealth Club of California in San Francisco. At the lecture, Cancer Commons founder (and long-term survivor of metastatic malignant melanoma), Jay Martin "Martin" Tenenbaum, PhD, spoke of the need for a cancer commons and the founder's vision. Emma Shtivelman, PhD, the long-time compassionate chief scientist, described some of the thousands of patients with advanced cancer that she has helped — all free of charge. And newly named CEO Clifford Reid, MBA, PhD, used his entrepreneurial prowess to envision an ambitious future.

Cancer Commons has always focused on patients with cancer who are beyond standards of curative care. As Cancer Commons evolves, it anticipates focusing on patients with cancer who are beyond National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines. The organization intends to greatly expand its 1000 patients per year with "high touch" engagement with PhD clinical scientists to many thousands by including artificial intelligence. It plans to extend its N-of-One approach to create new knowledge — especially regarding the hundreds of drugs that are FDA-approved for use in treating cancer but have not been further assessed for the utility in actually treating patients with cancer.

The war on cancer is not over. It remains a persistent foe that causes immense disability, pain, and human suffering. With government support depleted, the burden now shifts to the private sector and philanthropic organizations, such as Cancer Commons, to serve as the new vital infrastructure in the fight for a cure. Now, we must redouble our efforts to ensure that these research endeavors are supported if the US government will not do its part.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The War on Cancer, declared by President Richard Nixon some 50 years ago, has been canceled during the second Trump administration in 2025 — so saith The New York Times Sunday magazine cover story on September 14, 2025. This war seems now to be best described as "The War on Cancer Research."

To our horror and disbelief, we've witnessed the slow but persistent drift of much of the United States citizenry away from science and the sudden and severe movement of the US government to crush much medical research. But it is not as if we were not warned.

In August 2024, on these pages and without political bias, I urged Medscape readers to pay attention to Project 2025. A great deal of what we as a population are now experiencing was laid out as a carefully constructed plan.

What is surprising is the cruel ruthlessness of the "move fast and break things" approach, taken with little apparent concern about the resultant human tragedies (workforce and patients) and no clear care about the resulting fallout. As we've now learned, destroying something as grand as our cancer research enterprise can be accomplished very quickly. Rebuilding it is certain to be slow and difficult and perhaps can never be accomplished.

In this new anti-science, anti-research, and anti-researcher reality, what can we now do?

First and foremost, we must recognize that the war on cancer is not over. Cancer is not canceled, even if much of the US government's research effort/funding has been. Those of us in medicine and public health often speak in quantification of causes of death of our populations. As such, I'll remind Medscape readers that cancer afflicts some 20 million humans worldwide each year, killing nearly 10 million. Although two-thirds of Americans diagnosed with a potentially lethal malignancy are cured, cancer still kills roughly 600,000 Americans each year. Cancer has been the second most frequent cause of death of Americans for 75 years.

Being inevitable and immutable, death itself is not the enemy. We all die. Disease, disability, pain, and human suffering are the real enemies of us all. Cancer maims, pains, diabetes, and torments some 20 million humans worldwide each year. That is a huge humanitarian problem that should be recognized by individuals of all creeds and backgrounds.

With this depletion of our domestic government basic and applied cancer research program, what can we do?

- Think globally and look to the international scientific research enterprises — relying on them, much as they have relied on us.

- Defend the universal importance of reliable and available literature on medical science.

- Continue to translate and apply the vast amount of available published research in clinical practice and publish the results.

- Urge private industries to expand their research budgets into areas of study that may not produce quickly tangible positive bottom-line results.

- Remind the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (for whom chronic diseases seem paramount) that cancer is the second leading American chronic disease by morbidity.

- Redouble efforts of cancer prevention, especially urging the FDA to ban combustible tobacco and strive more diligently to decrease obesity.

- Appeal to our vast philanthropic universe to increase its funding of nonprofit organizations active in the cancer investigation, diagnosis, and management space.

One such 501c3 organization is California-based Cancer Commons. (Disclosure: I named it in 2010 and serve as its editor in chief).

A commons is a space shared by a community to use for the common interest. As we originally envisioned it, a cancer commons is an open access internet location where individuals and organizations (eg, corporations, universities, government agencies, philanthropies) will voluntarily share their data to work together to defeat the common enemy of humans: cancer.

On September 8, 2025, Cancer Commons was the 15th annual Lundberg Institute Lecturer at the Commonwealth Club of California in San Francisco. At the lecture, Cancer Commons founder (and long-term survivor of metastatic malignant melanoma), Jay Martin "Martin" Tenenbaum, PhD, spoke of the need for a cancer commons and the founder's vision. Emma Shtivelman, PhD, the long-time compassionate chief scientist, described some of the thousands of patients with advanced cancer that she has helped — all free of charge. And newly named CEO Clifford Reid, MBA, PhD, used his entrepreneurial prowess to envision an ambitious future.

Cancer Commons has always focused on patients with cancer who are beyond standards of curative care. As Cancer Commons evolves, it anticipates focusing on patients with cancer who are beyond National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines. The organization intends to greatly expand its 1000 patients per year with "high touch" engagement with PhD clinical scientists to many thousands by including artificial intelligence. It plans to extend its N-of-One approach to create new knowledge — especially regarding the hundreds of drugs that are FDA-approved for use in treating cancer but have not been further assessed for the utility in actually treating patients with cancer.

The war on cancer is not over. It remains a persistent foe that causes immense disability, pain, and human suffering. With government support depleted, the burden now shifts to the private sector and philanthropic organizations, such as Cancer Commons, to serve as the new vital infrastructure in the fight for a cure. Now, we must redouble our efforts to ensure that these research endeavors are supported if the US government will not do its part.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Turning the Cancer Research Problem Into an Opportunity

Turning the Cancer Research Problem Into an Opportunity

Impact of Retroactive Application of Updated Surveillance Guidelines on Endoscopy Center Capacity at a Large VA Health Care System

Impact of Retroactive Application of Updated Surveillance Guidelines on Endoscopy Center Capacity at a Large VA Health Care System

In 2020, the US Multi-Society Task Force (USMSTF) on Colorectal Cancer (CRC) increased the recommended colon polyp surveillance interval for 1 to 2 subcentimeter tubular adenomas from 5 to 10 years to 7 to 10 years.1 This change was prompted by emerging research indicating that rates of CRC and advanced neoplasia among patients with a history of only 1 to 2 subcentimeter tubular adenomas are lower than initially estimated.2,3 This extension provides an opportunity to increase endoscopy capacity and improve access to colonoscopies by retroactively applying the 2020 guidelines to surveillance interval recommendations made before their introduction. For example, based on the updated guidelines, patients previously recommended to undergo colon polyp surveillance colonoscopy 5 years after an index colonoscopy could extend their surveillance interval by 2 to 5 years. Increasing endoscopic capacity could address the growing demand for colonoscopies from new screening guidelines that reduced the age of initial CRC screening from 50 years to 45 years and the backlog of procedures due to COVID-19 restrictions.4

As part of a project to increase endoscopic capacity at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Pittsburgh Healthcare System (VAPHS), this study assessed the potential impact of retroactively applying the 2020 USMSTF polyp surveillance guidelines on endoscopic capacity. These results may be informative for other VA and private-sector health care systems seeking to identify strategies to improve endoscopy capacity.

Methods

VAPHS is an integrated health care system in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) serving 85,000 patients across 8 health care institutions in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia. VAPHS manages colorectal screening recommendations for patients receiving medical care in the health care system regardless of whether their prior colonoscopy was performed at VAPHS or external facilities. The VA maintains a national CRC screening and surveillance electronic medical record reminder that prompts health care practitioners to order colon polyp surveillance based on interval recommendations from the index colonoscopy. This study reviewed all patients from the VAPHS panel with a reminder to undergo colonoscopy for screening for CRC or surveillance of colon polyps within 12 months from September 1, 2022.

Among patients with a reminder, 3 investigators reviewed index colonoscopy and pathology reports to identify CRC risk category, colonoscopy indication, procedural quality, and recommended repeat colonoscopy interval. Per the USMSTF guidelines, patients with incomplete colonoscopy or pathology records, high-risk indications (ie, personal history of inflammatory bowel disease, personal history of CRC, or family history of CRC), or inadequate bowel preparation (Boston Bowel Preparation Score < 6) were excluded. Additionally, patients who had CRC screening or surveillance discontinued due to age or comorbidities, had completed a subsequent follow-up colonoscopy, or were deceased at the time of review were excluded.

Retroactive Interval Reclassification

Among eligible patients, this study compared the repeat colonoscopy interval recommended by the prior endoscopist with those from the 2020 USMSTF guidelines. In cases where the interval was documented as a range of years, the lower end was considered the recommendation. Similarly, the lower end of the range from the 2020 USMSTF guidelines was used for the reclassified surveillance interval. Years extended per patient were quantified relative to September 1, 2023 (ie, 1 year after the review date). For example, if the index colonoscopy was completed on September 1, 2016, the initial surveillance recommendation was 5 years, and the reclassified recommendation was 7 years, the interval extension beyond September 1, 2023, was 0 years.

Furthermore, because index surveillance recommendations are not always guideline concordant, the years extended per patient were calculated by harmonizing the index endoscopist’s recommendations with the guidelines at the time of the index colonoscopy.5 For example, if the index colonoscopy was completed on September 1, 2018, and the endoscopist recommended a 5-year follow-up for a patient with average risk for CRC, adequate bowel preparation, and no colorectal polyps, that patient is eligible to extend their colonoscopy to September 1, 2028, based on guideline recommendations at the time of index endoscopy recommending that the next colonoscopy occur in 10 years. In this analysis the 2012 USMSTF guidelines were applied to all index colonoscopies completed in 2021 or earlier to allow time for adoption of the 2020 guidelines.

This project fulfilled a facility mandate to increase capacity to conduct endoscopic procedures. Institutional review board approval was not required by VAPHS policy relating to clinical operations projects. Approval for publication of clinical operations activity was obtained from the VAPHS facility director.

Results

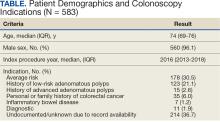

Within 1 year of the September 1, 2022, review date, 637 patients receiving care at VAPHS had clinical reminders for an upcoming colonoscopy. Of these, 54 (8.4%) were already up to date or were deceased at the time of review. Of the 583 eligible patients, 96% were male, the median age was 74 years, the median index colonoscopy year was 2016, and 178 (30.5%) had an average-risk CRC screening indication at the index colonoscopy (Table).

Of the 583 patients due for colonoscopy, 331 (56.7%) had both colonoscopy and pathology reports available. The majority of those with incomplete records had the index colonoscopy completed outside VAPHS. Among these patients, 222 (67.0%) had adequate bowel preparation. Of those with adequate bowel preparation, 43 were not eligible for interval extension because of high-risk conditions and 13 were not eligible because there was no index surveillance interval recommendation from the index endoscopist. Of the patients due for colonoscopy, 166 (28.4%) were potentially eligible for surveillance interval extension (Figure).

Sixty-five (39.2%) of the 166 patients had 1 to 2 subcentimeter tubular adenomas on their index colonoscopy. Sixty-two patients were eligible for interval extension to 7 years, but this only resulted in ≥ 1 year of extension beyond the review date for 36 (6% of all 583 patients due for colonoscopy). The 36 patients were extended 63 years. By harmonizing the index endoscopists’ surveillance interval recommendation with the guideline at the time of the index colonoscopy, 29 additional patients could have their colonoscopy extended by ≥ 1 year. Harmonization extended colonoscopy intervals by 93 years. Retroactively applying the 2020 USMSTF polyp surveillance guidelines and harmonizing recommendations to guidelines extended the time of index colonoscopy by 153 years.

Discussion

With retroactive application of the 2020 USMSTF polyp surveillance guidelines, 6% of patients due for an upcoming colonoscopy could extend their follow-up by ≥ 1 year by extending the surveillance interval for 1 to 2 subcentimeter tubular adenomas to 7 years. An additional 5% of patients could extend their interval by harmonizing the index endoscopist’s interval recommendation with polyp surveillance guidelines at the time of the index colonoscopy. These findings are consistent with the results of 2 studies that demonstrated that about 14% of patients due for colonoscopy could have their interval extended.6,7 The current study enhances those insights by separating the contribution of 2020 USMSTF polyp surveillance guidelines from the contribution of harmonizing surveillance intervals with guidelines for other polyp histologies. This study found that there is an opportunity to improve endoscopic capacity by harmonizing recommendations with guidelines. This complements a 2023 study showing that even when knowledgeable about guidelines, clinicians do not necessarily follow recommendations.8 While this and previous research have identified that 11% to 14% of patients are eligible for extension, these individuals would also have to be willing to have their polyp surveillance intervals extended for there to be a real-world impact on endoscopic capacity. A 2024 study found that only 19% to 37% of patients with 1 to 2 small tubular adenomas were willing to have polyps surveillance interval extension.9 This suggests the actual effect on capacity may be even lower than reported.

Limitations

The overall impact of the 2020 USMSTF polyp surveillance guidelines on endoscopic capacity was blunted by the high prevalence of incomplete index colonoscopy records among the study population. Without data on bowel preparation quality or procedure indications, this study could not assess whether 43% of patients were eligible for surveillance interval extension. Most index colonoscopies with incomplete documentation were completed at community-care gastroenterology facilities. This high rate of incomplete documentation is likely generalizable to other VA health care systems—especially in the era of the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014, which increased veteran access to non-VA community care.10 Veterans due for colon polyp surveillance colonoscopies are more likely to have had their prior colonoscopy in community care compared with prior eras.11 Furthermore, because the VHA is among the most established integrated health care systems offering primary and subspecialty care in the US, private sector health care systems may have even greater rates of care fragmentation for longitudinal CRC screening and colon polyp surveillance, as these systems have only begun to regionally integrate recently.12,13

Another limitation is that nearly one-third of the individuals with documentation had inadequate bowel preparation for surveillance recommendations. This results in shorter surveillance follow-up colonoscopies and increases downstream demand for future colonoscopies. The low yield of extending colon polyp surveillance interval in this study emphasizes that improved efforts to obtain colonoscopy and pathology reports from community care, right-sizing the colon polyp surveillance intervals recommended by endoscopists, and improving quality of bowel preparation could have downstream health care system benefits in the future. These efforts could increase colonoscopy capacity at VA health care systems, thereby shortening colonoscopy wait times, decreasing fragmentation of care, and increasing the number of veterans who receive high-quality colonoscopies at VA health care systems.14

Conclusions

Eleven percent of patients in this study due for a colonoscopy could extend their follow-up by ≥ 1 year. About half of these extensions were directly due to the 2020 USMSTF polyp surveillance interval extension for 1 to 2 subcentimeter tubular adenomas. The rest resulted from harmonizing recommendations with guidelines at the time of the procedure. To determine whether retroactively applying polyp surveillance guidelines to follow-up interval recommendations will result in improved endoscopic capacity, health care system administrators should consider the degree of CRC screening care fragmentation in their patient population. Greater long-term gains in endoscopic capacity may be achieved by proactively supporting endoscopists in making guideline-concordant screening recommendations at the time of colonoscopy.

Gupta S, Lieberman D, Anderson JC, et al. Recommendations for follow-up after colonoscopy and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91:463-485. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2020.01.014

Dubé C, Yakubu M, McCurdy BR, et al. Risk of advanced adenoma, colorectal cancer, and colorectal cancer mortality in people with low-risk adenomas at baseline colonoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1790-1801. doi:10.1038/ajg.2017.360

Click B, Pinsky PF, Hickey T, Doroudi M, Shoen RE. Association of colonoscopy adenoma findings with long-term colorectal cancer incidence. JAMA. 2018;319:2021-2031. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.5809

US Preventive Services Task Force, Davidson KW, Barry MJ, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325:1965-1977. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.6238

Djinbachian R, Dubé AJ, Durand M, et al. Adherence to post-polypectomy surveillance guidelines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2019;51:673-683. doi:10.1055/a-0865-2082

Gawron AJ, Kaltenbach T, Dominitz JA. The impact of the coronavirus disease-19 pandemic on access to endoscopy procedures in the VA healthcare system. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:1216-1220.e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.07.033

Xiao AH, Chang SY, Stevoff CG, Komanduri S, Pandolfino JE, Keswani RN. Adoption of multi-society guidelines facilitates value-based reduction in screening and surveillance colonoscopy volume during COVID-19 pandemic. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66:2578-2584. doi:10.1007/s10620-020-06539-1

Dong J, Wang LF, Ardolino E, Feuerstein JD. Real-world compliance with the 2020 U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer polypectomy surveillance guidelines: an observational study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;97:350-356.e3. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2022.08.020

Lee JK, Koripella PC, Jensen CD, et al. Randomized trial of patient outreach approaches to de-implement outdated colonoscopy surveillance intervals. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22:1315-1322.e7. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2023.12.027

Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014, HR 3230, 113th Cong (2014). Accessed September 8, 2025. https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/house-bill/3230

Dueker JM, Khalid A. Performance of the Veterans Choice Program for improving access to colonoscopy at a tertiary VA facility. Fed Pract. 2020;37:224-228.

Oliver A. The Veterans Health Administration: an American success story? Milbank Q. 2007;85:5-35. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00475.x

Furukawa MF, Machta RM, Barrett KA, et al. Landscape of health systems in the United States. Med Care Res Rev. 2020;77:357-366. doi:10.1177/1077558718823130

Petros V, Tsambikos E, Madhoun M, Tierney WM. Impact of community referral on colonoscopy quality metrics in a Veterans Affairs Medical Center. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2022;13:e00460. doi:10.14309/ctg.0000000000000460

In 2020, the US Multi-Society Task Force (USMSTF) on Colorectal Cancer (CRC) increased the recommended colon polyp surveillance interval for 1 to 2 subcentimeter tubular adenomas from 5 to 10 years to 7 to 10 years.1 This change was prompted by emerging research indicating that rates of CRC and advanced neoplasia among patients with a history of only 1 to 2 subcentimeter tubular adenomas are lower than initially estimated.2,3 This extension provides an opportunity to increase endoscopy capacity and improve access to colonoscopies by retroactively applying the 2020 guidelines to surveillance interval recommendations made before their introduction. For example, based on the updated guidelines, patients previously recommended to undergo colon polyp surveillance colonoscopy 5 years after an index colonoscopy could extend their surveillance interval by 2 to 5 years. Increasing endoscopic capacity could address the growing demand for colonoscopies from new screening guidelines that reduced the age of initial CRC screening from 50 years to 45 years and the backlog of procedures due to COVID-19 restrictions.4

As part of a project to increase endoscopic capacity at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Pittsburgh Healthcare System (VAPHS), this study assessed the potential impact of retroactively applying the 2020 USMSTF polyp surveillance guidelines on endoscopic capacity. These results may be informative for other VA and private-sector health care systems seeking to identify strategies to improve endoscopy capacity.

Methods

VAPHS is an integrated health care system in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) serving 85,000 patients across 8 health care institutions in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia. VAPHS manages colorectal screening recommendations for patients receiving medical care in the health care system regardless of whether their prior colonoscopy was performed at VAPHS or external facilities. The VA maintains a national CRC screening and surveillance electronic medical record reminder that prompts health care practitioners to order colon polyp surveillance based on interval recommendations from the index colonoscopy. This study reviewed all patients from the VAPHS panel with a reminder to undergo colonoscopy for screening for CRC or surveillance of colon polyps within 12 months from September 1, 2022.

Among patients with a reminder, 3 investigators reviewed index colonoscopy and pathology reports to identify CRC risk category, colonoscopy indication, procedural quality, and recommended repeat colonoscopy interval. Per the USMSTF guidelines, patients with incomplete colonoscopy or pathology records, high-risk indications (ie, personal history of inflammatory bowel disease, personal history of CRC, or family history of CRC), or inadequate bowel preparation (Boston Bowel Preparation Score < 6) were excluded. Additionally, patients who had CRC screening or surveillance discontinued due to age or comorbidities, had completed a subsequent follow-up colonoscopy, or were deceased at the time of review were excluded.

Retroactive Interval Reclassification

Among eligible patients, this study compared the repeat colonoscopy interval recommended by the prior endoscopist with those from the 2020 USMSTF guidelines. In cases where the interval was documented as a range of years, the lower end was considered the recommendation. Similarly, the lower end of the range from the 2020 USMSTF guidelines was used for the reclassified surveillance interval. Years extended per patient were quantified relative to September 1, 2023 (ie, 1 year after the review date). For example, if the index colonoscopy was completed on September 1, 2016, the initial surveillance recommendation was 5 years, and the reclassified recommendation was 7 years, the interval extension beyond September 1, 2023, was 0 years.

Furthermore, because index surveillance recommendations are not always guideline concordant, the years extended per patient were calculated by harmonizing the index endoscopist’s recommendations with the guidelines at the time of the index colonoscopy.5 For example, if the index colonoscopy was completed on September 1, 2018, and the endoscopist recommended a 5-year follow-up for a patient with average risk for CRC, adequate bowel preparation, and no colorectal polyps, that patient is eligible to extend their colonoscopy to September 1, 2028, based on guideline recommendations at the time of index endoscopy recommending that the next colonoscopy occur in 10 years. In this analysis the 2012 USMSTF guidelines were applied to all index colonoscopies completed in 2021 or earlier to allow time for adoption of the 2020 guidelines.

This project fulfilled a facility mandate to increase capacity to conduct endoscopic procedures. Institutional review board approval was not required by VAPHS policy relating to clinical operations projects. Approval for publication of clinical operations activity was obtained from the VAPHS facility director.

Results

Within 1 year of the September 1, 2022, review date, 637 patients receiving care at VAPHS had clinical reminders for an upcoming colonoscopy. Of these, 54 (8.4%) were already up to date or were deceased at the time of review. Of the 583 eligible patients, 96% were male, the median age was 74 years, the median index colonoscopy year was 2016, and 178 (30.5%) had an average-risk CRC screening indication at the index colonoscopy (Table).

Of the 583 patients due for colonoscopy, 331 (56.7%) had both colonoscopy and pathology reports available. The majority of those with incomplete records had the index colonoscopy completed outside VAPHS. Among these patients, 222 (67.0%) had adequate bowel preparation. Of those with adequate bowel preparation, 43 were not eligible for interval extension because of high-risk conditions and 13 were not eligible because there was no index surveillance interval recommendation from the index endoscopist. Of the patients due for colonoscopy, 166 (28.4%) were potentially eligible for surveillance interval extension (Figure).

Sixty-five (39.2%) of the 166 patients had 1 to 2 subcentimeter tubular adenomas on their index colonoscopy. Sixty-two patients were eligible for interval extension to 7 years, but this only resulted in ≥ 1 year of extension beyond the review date for 36 (6% of all 583 patients due for colonoscopy). The 36 patients were extended 63 years. By harmonizing the index endoscopists’ surveillance interval recommendation with the guideline at the time of the index colonoscopy, 29 additional patients could have their colonoscopy extended by ≥ 1 year. Harmonization extended colonoscopy intervals by 93 years. Retroactively applying the 2020 USMSTF polyp surveillance guidelines and harmonizing recommendations to guidelines extended the time of index colonoscopy by 153 years.

Discussion

With retroactive application of the 2020 USMSTF polyp surveillance guidelines, 6% of patients due for an upcoming colonoscopy could extend their follow-up by ≥ 1 year by extending the surveillance interval for 1 to 2 subcentimeter tubular adenomas to 7 years. An additional 5% of patients could extend their interval by harmonizing the index endoscopist’s interval recommendation with polyp surveillance guidelines at the time of the index colonoscopy. These findings are consistent with the results of 2 studies that demonstrated that about 14% of patients due for colonoscopy could have their interval extended.6,7 The current study enhances those insights by separating the contribution of 2020 USMSTF polyp surveillance guidelines from the contribution of harmonizing surveillance intervals with guidelines for other polyp histologies. This study found that there is an opportunity to improve endoscopic capacity by harmonizing recommendations with guidelines. This complements a 2023 study showing that even when knowledgeable about guidelines, clinicians do not necessarily follow recommendations.8 While this and previous research have identified that 11% to 14% of patients are eligible for extension, these individuals would also have to be willing to have their polyp surveillance intervals extended for there to be a real-world impact on endoscopic capacity. A 2024 study found that only 19% to 37% of patients with 1 to 2 small tubular adenomas were willing to have polyps surveillance interval extension.9 This suggests the actual effect on capacity may be even lower than reported.

Limitations

The overall impact of the 2020 USMSTF polyp surveillance guidelines on endoscopic capacity was blunted by the high prevalence of incomplete index colonoscopy records among the study population. Without data on bowel preparation quality or procedure indications, this study could not assess whether 43% of patients were eligible for surveillance interval extension. Most index colonoscopies with incomplete documentation were completed at community-care gastroenterology facilities. This high rate of incomplete documentation is likely generalizable to other VA health care systems—especially in the era of the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014, which increased veteran access to non-VA community care.10 Veterans due for colon polyp surveillance colonoscopies are more likely to have had their prior colonoscopy in community care compared with prior eras.11 Furthermore, because the VHA is among the most established integrated health care systems offering primary and subspecialty care in the US, private sector health care systems may have even greater rates of care fragmentation for longitudinal CRC screening and colon polyp surveillance, as these systems have only begun to regionally integrate recently.12,13

Another limitation is that nearly one-third of the individuals with documentation had inadequate bowel preparation for surveillance recommendations. This results in shorter surveillance follow-up colonoscopies and increases downstream demand for future colonoscopies. The low yield of extending colon polyp surveillance interval in this study emphasizes that improved efforts to obtain colonoscopy and pathology reports from community care, right-sizing the colon polyp surveillance intervals recommended by endoscopists, and improving quality of bowel preparation could have downstream health care system benefits in the future. These efforts could increase colonoscopy capacity at VA health care systems, thereby shortening colonoscopy wait times, decreasing fragmentation of care, and increasing the number of veterans who receive high-quality colonoscopies at VA health care systems.14

Conclusions

Eleven percent of patients in this study due for a colonoscopy could extend their follow-up by ≥ 1 year. About half of these extensions were directly due to the 2020 USMSTF polyp surveillance interval extension for 1 to 2 subcentimeter tubular adenomas. The rest resulted from harmonizing recommendations with guidelines at the time of the procedure. To determine whether retroactively applying polyp surveillance guidelines to follow-up interval recommendations will result in improved endoscopic capacity, health care system administrators should consider the degree of CRC screening care fragmentation in their patient population. Greater long-term gains in endoscopic capacity may be achieved by proactively supporting endoscopists in making guideline-concordant screening recommendations at the time of colonoscopy.

In 2020, the US Multi-Society Task Force (USMSTF) on Colorectal Cancer (CRC) increased the recommended colon polyp surveillance interval for 1 to 2 subcentimeter tubular adenomas from 5 to 10 years to 7 to 10 years.1 This change was prompted by emerging research indicating that rates of CRC and advanced neoplasia among patients with a history of only 1 to 2 subcentimeter tubular adenomas are lower than initially estimated.2,3 This extension provides an opportunity to increase endoscopy capacity and improve access to colonoscopies by retroactively applying the 2020 guidelines to surveillance interval recommendations made before their introduction. For example, based on the updated guidelines, patients previously recommended to undergo colon polyp surveillance colonoscopy 5 years after an index colonoscopy could extend their surveillance interval by 2 to 5 years. Increasing endoscopic capacity could address the growing demand for colonoscopies from new screening guidelines that reduced the age of initial CRC screening from 50 years to 45 years and the backlog of procedures due to COVID-19 restrictions.4

As part of a project to increase endoscopic capacity at the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Pittsburgh Healthcare System (VAPHS), this study assessed the potential impact of retroactively applying the 2020 USMSTF polyp surveillance guidelines on endoscopic capacity. These results may be informative for other VA and private-sector health care systems seeking to identify strategies to improve endoscopy capacity.

Methods

VAPHS is an integrated health care system in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) serving 85,000 patients across 8 health care institutions in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia. VAPHS manages colorectal screening recommendations for patients receiving medical care in the health care system regardless of whether their prior colonoscopy was performed at VAPHS or external facilities. The VA maintains a national CRC screening and surveillance electronic medical record reminder that prompts health care practitioners to order colon polyp surveillance based on interval recommendations from the index colonoscopy. This study reviewed all patients from the VAPHS panel with a reminder to undergo colonoscopy for screening for CRC or surveillance of colon polyps within 12 months from September 1, 2022.

Among patients with a reminder, 3 investigators reviewed index colonoscopy and pathology reports to identify CRC risk category, colonoscopy indication, procedural quality, and recommended repeat colonoscopy interval. Per the USMSTF guidelines, patients with incomplete colonoscopy or pathology records, high-risk indications (ie, personal history of inflammatory bowel disease, personal history of CRC, or family history of CRC), or inadequate bowel preparation (Boston Bowel Preparation Score < 6) were excluded. Additionally, patients who had CRC screening or surveillance discontinued due to age or comorbidities, had completed a subsequent follow-up colonoscopy, or were deceased at the time of review were excluded.

Retroactive Interval Reclassification

Among eligible patients, this study compared the repeat colonoscopy interval recommended by the prior endoscopist with those from the 2020 USMSTF guidelines. In cases where the interval was documented as a range of years, the lower end was considered the recommendation. Similarly, the lower end of the range from the 2020 USMSTF guidelines was used for the reclassified surveillance interval. Years extended per patient were quantified relative to September 1, 2023 (ie, 1 year after the review date). For example, if the index colonoscopy was completed on September 1, 2016, the initial surveillance recommendation was 5 years, and the reclassified recommendation was 7 years, the interval extension beyond September 1, 2023, was 0 years.

Furthermore, because index surveillance recommendations are not always guideline concordant, the years extended per patient were calculated by harmonizing the index endoscopist’s recommendations with the guidelines at the time of the index colonoscopy.5 For example, if the index colonoscopy was completed on September 1, 2018, and the endoscopist recommended a 5-year follow-up for a patient with average risk for CRC, adequate bowel preparation, and no colorectal polyps, that patient is eligible to extend their colonoscopy to September 1, 2028, based on guideline recommendations at the time of index endoscopy recommending that the next colonoscopy occur in 10 years. In this analysis the 2012 USMSTF guidelines were applied to all index colonoscopies completed in 2021 or earlier to allow time for adoption of the 2020 guidelines.

This project fulfilled a facility mandate to increase capacity to conduct endoscopic procedures. Institutional review board approval was not required by VAPHS policy relating to clinical operations projects. Approval for publication of clinical operations activity was obtained from the VAPHS facility director.

Results

Within 1 year of the September 1, 2022, review date, 637 patients receiving care at VAPHS had clinical reminders for an upcoming colonoscopy. Of these, 54 (8.4%) were already up to date or were deceased at the time of review. Of the 583 eligible patients, 96% were male, the median age was 74 years, the median index colonoscopy year was 2016, and 178 (30.5%) had an average-risk CRC screening indication at the index colonoscopy (Table).

Of the 583 patients due for colonoscopy, 331 (56.7%) had both colonoscopy and pathology reports available. The majority of those with incomplete records had the index colonoscopy completed outside VAPHS. Among these patients, 222 (67.0%) had adequate bowel preparation. Of those with adequate bowel preparation, 43 were not eligible for interval extension because of high-risk conditions and 13 were not eligible because there was no index surveillance interval recommendation from the index endoscopist. Of the patients due for colonoscopy, 166 (28.4%) were potentially eligible for surveillance interval extension (Figure).

Sixty-five (39.2%) of the 166 patients had 1 to 2 subcentimeter tubular adenomas on their index colonoscopy. Sixty-two patients were eligible for interval extension to 7 years, but this only resulted in ≥ 1 year of extension beyond the review date for 36 (6% of all 583 patients due for colonoscopy). The 36 patients were extended 63 years. By harmonizing the index endoscopists’ surveillance interval recommendation with the guideline at the time of the index colonoscopy, 29 additional patients could have their colonoscopy extended by ≥ 1 year. Harmonization extended colonoscopy intervals by 93 years. Retroactively applying the 2020 USMSTF polyp surveillance guidelines and harmonizing recommendations to guidelines extended the time of index colonoscopy by 153 years.

Discussion

With retroactive application of the 2020 USMSTF polyp surveillance guidelines, 6% of patients due for an upcoming colonoscopy could extend their follow-up by ≥ 1 year by extending the surveillance interval for 1 to 2 subcentimeter tubular adenomas to 7 years. An additional 5% of patients could extend their interval by harmonizing the index endoscopist’s interval recommendation with polyp surveillance guidelines at the time of the index colonoscopy. These findings are consistent with the results of 2 studies that demonstrated that about 14% of patients due for colonoscopy could have their interval extended.6,7 The current study enhances those insights by separating the contribution of 2020 USMSTF polyp surveillance guidelines from the contribution of harmonizing surveillance intervals with guidelines for other polyp histologies. This study found that there is an opportunity to improve endoscopic capacity by harmonizing recommendations with guidelines. This complements a 2023 study showing that even when knowledgeable about guidelines, clinicians do not necessarily follow recommendations.8 While this and previous research have identified that 11% to 14% of patients are eligible for extension, these individuals would also have to be willing to have their polyp surveillance intervals extended for there to be a real-world impact on endoscopic capacity. A 2024 study found that only 19% to 37% of patients with 1 to 2 small tubular adenomas were willing to have polyps surveillance interval extension.9 This suggests the actual effect on capacity may be even lower than reported.

Limitations

The overall impact of the 2020 USMSTF polyp surveillance guidelines on endoscopic capacity was blunted by the high prevalence of incomplete index colonoscopy records among the study population. Without data on bowel preparation quality or procedure indications, this study could not assess whether 43% of patients were eligible for surveillance interval extension. Most index colonoscopies with incomplete documentation were completed at community-care gastroenterology facilities. This high rate of incomplete documentation is likely generalizable to other VA health care systems—especially in the era of the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014, which increased veteran access to non-VA community care.10 Veterans due for colon polyp surveillance colonoscopies are more likely to have had their prior colonoscopy in community care compared with prior eras.11 Furthermore, because the VHA is among the most established integrated health care systems offering primary and subspecialty care in the US, private sector health care systems may have even greater rates of care fragmentation for longitudinal CRC screening and colon polyp surveillance, as these systems have only begun to regionally integrate recently.12,13

Another limitation is that nearly one-third of the individuals with documentation had inadequate bowel preparation for surveillance recommendations. This results in shorter surveillance follow-up colonoscopies and increases downstream demand for future colonoscopies. The low yield of extending colon polyp surveillance interval in this study emphasizes that improved efforts to obtain colonoscopy and pathology reports from community care, right-sizing the colon polyp surveillance intervals recommended by endoscopists, and improving quality of bowel preparation could have downstream health care system benefits in the future. These efforts could increase colonoscopy capacity at VA health care systems, thereby shortening colonoscopy wait times, decreasing fragmentation of care, and increasing the number of veterans who receive high-quality colonoscopies at VA health care systems.14

Conclusions

Eleven percent of patients in this study due for a colonoscopy could extend their follow-up by ≥ 1 year. About half of these extensions were directly due to the 2020 USMSTF polyp surveillance interval extension for 1 to 2 subcentimeter tubular adenomas. The rest resulted from harmonizing recommendations with guidelines at the time of the procedure. To determine whether retroactively applying polyp surveillance guidelines to follow-up interval recommendations will result in improved endoscopic capacity, health care system administrators should consider the degree of CRC screening care fragmentation in their patient population. Greater long-term gains in endoscopic capacity may be achieved by proactively supporting endoscopists in making guideline-concordant screening recommendations at the time of colonoscopy.

Gupta S, Lieberman D, Anderson JC, et al. Recommendations for follow-up after colonoscopy and polypectomy: a consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91:463-485. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2020.01.014

Dubé C, Yakubu M, McCurdy BR, et al. Risk of advanced adenoma, colorectal cancer, and colorectal cancer mortality in people with low-risk adenomas at baseline colonoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1790-1801. doi:10.1038/ajg.2017.360

Click B, Pinsky PF, Hickey T, Doroudi M, Shoen RE. Association of colonoscopy adenoma findings with long-term colorectal cancer incidence. JAMA. 2018;319:2021-2031. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.5809

US Preventive Services Task Force, Davidson KW, Barry MJ, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325:1965-1977. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.6238

Djinbachian R, Dubé AJ, Durand M, et al. Adherence to post-polypectomy surveillance guidelines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2019;51:673-683. doi:10.1055/a-0865-2082

Gawron AJ, Kaltenbach T, Dominitz JA. The impact of the coronavirus disease-19 pandemic on access to endoscopy procedures in the VA healthcare system. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:1216-1220.e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.07.033

Xiao AH, Chang SY, Stevoff CG, Komanduri S, Pandolfino JE, Keswani RN. Adoption of multi-society guidelines facilitates value-based reduction in screening and surveillance colonoscopy volume during COVID-19 pandemic. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66:2578-2584. doi:10.1007/s10620-020-06539-1

Dong J, Wang LF, Ardolino E, Feuerstein JD. Real-world compliance with the 2020 U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer polypectomy surveillance guidelines: an observational study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;97:350-356.e3. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2022.08.020

Lee JK, Koripella PC, Jensen CD, et al. Randomized trial of patient outreach approaches to de-implement outdated colonoscopy surveillance intervals. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22:1315-1322.e7. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2023.12.027