User login

Optimizing use of TKIs in chronic leukemia

DUBROVNIK, CROATIA – Long-term efficacy and toxicity should inform decisions about tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), according to one expert.

Studies have indicated that long-term survival rates are similar whether CML patients receive frontline treatment with imatinib or second-generation TKIs. But the newer TKIs pose a higher risk of uncommon toxicities, Hagop M. Kantarjian, MD, said during the keynote presentation at Leukemia and Lymphoma, a meeting jointly sponsored by the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and the School of Medicine at the University of Zagreb, Croatia.

Dr. Kantarjian, a professor at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, said most CML patients should receive daily treatment with TKIs – even if they are in complete cytogenetic response or 100% Philadelphia chromosome positive – because they will live longer.

Frontline treatment options for CML that are approved by the Food and Drug Administration include imatinib, dasatinib, nilotinib, and bosutinib.

Dr. Kantarjian noted that dasatinib and nilotinib bested imatinib in early analyses from clinical trials, but all three TKIs produced similar rates of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) at extended follow-up.

Dasatinib and imatinib produced similar rates of 5-year OS and PFS in the DASISION trial (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jul 10;34[20]:2333-40).

In ENESTnd, 5-year OS and PFS rates were similar with nilotinib and imatinib (Leukemia. 2016 May;30[5]:1044-54).

However, the higher incidence of uncommon toxicities with the newer TKIs must be taken into account, Dr. Kantarjian said.

Choosing a TKI

Dr. Kantarjian recommends frontline imatinib for older patients (aged 65-70) and those who are low risk based on their Sokal score.

Second-generation TKIs should be given up front to patients who are at higher risk by Sokal and for “very young patients in whom early treatment discontinuation is important,” he said.

“In accelerated or blast phase, I always use the second-generation TKIs,” he said. “If there’s no binding mutation, I prefer dasatinib. I think it’s the most potent of them. If there are toxicities with dasatinib, bosutinib is equivalent in efficacy, so they are interchangeable.”

A TKI should not be discarded unless there is loss of complete cytogenetic response – not major molecular response – at the maximum tolerated adjusted dose that does not cause grade 3-4 toxicities or chronic grade 2 toxicities, Dr. Kantarjian added.

“We have to remember that we can go down on the dosages of, for example, imatinib, down to 200 mg a day, dasatinib as low as 20 mg a day, nilotinib as low as 150 mg twice a day or even 200 mg daily, and bosutinib down to 200 mg daily,” he said. “So if we have a patient who’s responding with side effects, we should not abandon the particular TKI, we should try to manipulate the dose schedule if they are having a good response.”

Dr. Kantarjian noted that pleural effusion is a toxicity of particular concern with dasatinib, but lowering the dose to 50 mg daily results in similar efficacy and significantly less toxicity than 100 mg daily. For patients over the age of 70, a 20-mg dose can be used.

Vaso-occlusive and vasospastic reactions are increasingly observed in patients treated with nilotinib. For that reason, Dr. Kantarjian said he prefers to forgo up-front nilotinib, particularly in patients who have cardiovascular or neurotoxic problems.

“The incidence of vaso-occlusive and vasospastic reactions is now close to 10%-15% at about 10 years with nilotinib,” Dr. Kantarjian said. “So it is not a trivial toxicity.”

For patients with vaso-occlusive/vasospastic reactions, “bosutinib is probably the safest drug,” Dr. Kantarjian said.

For second- or third-line therapy, patients can receive ponatinib or a second-generation TKI (dasatinib, nilotinib, or bosutinib), as well as omacetaxine or allogeneic stem cell transplant.

“If you disregard toxicities, I think ponatinib is the most powerful TKI, and I think that’s because we are using it at a higher dose that produces so many toxicities,” Dr. Kantarjian said.

Ponatinib is not used up front because of these toxicities, particularly pancreatitis, skin rashes, vaso-occlusive disorders, and hypertension, he added.

Dr. Kantarjian suggests giving ponatinib at 30 mg daily in patients with T315I mutation and those without guiding mutations who are resistant to second-generation TKIs.

Discontinuing a TKI

Dr. Kantarjian said patients can discontinue TKI therapy if they:

- Are low- or intermediate-risk by Sokal.

- Have quantifiable BCR-ABL transcripts.

- Are in chronic phase.

- Achieved an optimal response to their first TKI.

- Have been on TKI therapy for more than 8 years.

- Achieved a complete molecular response.

- Have had a molecular response for more than 2-3 years.

- Are available for monitoring every other month for the first 2 years.

Dr. Kantarjian did not report any conflicts of interest at the meeting. However, he has previously reported relationships with Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, and Ariad Pharmaceuticals.

The Leukemia and Lymphoma meeting is organized by Jonathan Wood & Association, which is owned by the parent company of this news organization.

DUBROVNIK, CROATIA – Long-term efficacy and toxicity should inform decisions about tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), according to one expert.

Studies have indicated that long-term survival rates are similar whether CML patients receive frontline treatment with imatinib or second-generation TKIs. But the newer TKIs pose a higher risk of uncommon toxicities, Hagop M. Kantarjian, MD, said during the keynote presentation at Leukemia and Lymphoma, a meeting jointly sponsored by the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and the School of Medicine at the University of Zagreb, Croatia.

Dr. Kantarjian, a professor at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, said most CML patients should receive daily treatment with TKIs – even if they are in complete cytogenetic response or 100% Philadelphia chromosome positive – because they will live longer.

Frontline treatment options for CML that are approved by the Food and Drug Administration include imatinib, dasatinib, nilotinib, and bosutinib.

Dr. Kantarjian noted that dasatinib and nilotinib bested imatinib in early analyses from clinical trials, but all three TKIs produced similar rates of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) at extended follow-up.

Dasatinib and imatinib produced similar rates of 5-year OS and PFS in the DASISION trial (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jul 10;34[20]:2333-40).

In ENESTnd, 5-year OS and PFS rates were similar with nilotinib and imatinib (Leukemia. 2016 May;30[5]:1044-54).

However, the higher incidence of uncommon toxicities with the newer TKIs must be taken into account, Dr. Kantarjian said.

Choosing a TKI

Dr. Kantarjian recommends frontline imatinib for older patients (aged 65-70) and those who are low risk based on their Sokal score.

Second-generation TKIs should be given up front to patients who are at higher risk by Sokal and for “very young patients in whom early treatment discontinuation is important,” he said.

“In accelerated or blast phase, I always use the second-generation TKIs,” he said. “If there’s no binding mutation, I prefer dasatinib. I think it’s the most potent of them. If there are toxicities with dasatinib, bosutinib is equivalent in efficacy, so they are interchangeable.”

A TKI should not be discarded unless there is loss of complete cytogenetic response – not major molecular response – at the maximum tolerated adjusted dose that does not cause grade 3-4 toxicities or chronic grade 2 toxicities, Dr. Kantarjian added.

“We have to remember that we can go down on the dosages of, for example, imatinib, down to 200 mg a day, dasatinib as low as 20 mg a day, nilotinib as low as 150 mg twice a day or even 200 mg daily, and bosutinib down to 200 mg daily,” he said. “So if we have a patient who’s responding with side effects, we should not abandon the particular TKI, we should try to manipulate the dose schedule if they are having a good response.”

Dr. Kantarjian noted that pleural effusion is a toxicity of particular concern with dasatinib, but lowering the dose to 50 mg daily results in similar efficacy and significantly less toxicity than 100 mg daily. For patients over the age of 70, a 20-mg dose can be used.

Vaso-occlusive and vasospastic reactions are increasingly observed in patients treated with nilotinib. For that reason, Dr. Kantarjian said he prefers to forgo up-front nilotinib, particularly in patients who have cardiovascular or neurotoxic problems.

“The incidence of vaso-occlusive and vasospastic reactions is now close to 10%-15% at about 10 years with nilotinib,” Dr. Kantarjian said. “So it is not a trivial toxicity.”

For patients with vaso-occlusive/vasospastic reactions, “bosutinib is probably the safest drug,” Dr. Kantarjian said.

For second- or third-line therapy, patients can receive ponatinib or a second-generation TKI (dasatinib, nilotinib, or bosutinib), as well as omacetaxine or allogeneic stem cell transplant.

“If you disregard toxicities, I think ponatinib is the most powerful TKI, and I think that’s because we are using it at a higher dose that produces so many toxicities,” Dr. Kantarjian said.

Ponatinib is not used up front because of these toxicities, particularly pancreatitis, skin rashes, vaso-occlusive disorders, and hypertension, he added.

Dr. Kantarjian suggests giving ponatinib at 30 mg daily in patients with T315I mutation and those without guiding mutations who are resistant to second-generation TKIs.

Discontinuing a TKI

Dr. Kantarjian said patients can discontinue TKI therapy if they:

- Are low- or intermediate-risk by Sokal.

- Have quantifiable BCR-ABL transcripts.

- Are in chronic phase.

- Achieved an optimal response to their first TKI.

- Have been on TKI therapy for more than 8 years.

- Achieved a complete molecular response.

- Have had a molecular response for more than 2-3 years.

- Are available for monitoring every other month for the first 2 years.

Dr. Kantarjian did not report any conflicts of interest at the meeting. However, he has previously reported relationships with Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, and Ariad Pharmaceuticals.

The Leukemia and Lymphoma meeting is organized by Jonathan Wood & Association, which is owned by the parent company of this news organization.

DUBROVNIK, CROATIA – Long-term efficacy and toxicity should inform decisions about tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), according to one expert.

Studies have indicated that long-term survival rates are similar whether CML patients receive frontline treatment with imatinib or second-generation TKIs. But the newer TKIs pose a higher risk of uncommon toxicities, Hagop M. Kantarjian, MD, said during the keynote presentation at Leukemia and Lymphoma, a meeting jointly sponsored by the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and the School of Medicine at the University of Zagreb, Croatia.

Dr. Kantarjian, a professor at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, said most CML patients should receive daily treatment with TKIs – even if they are in complete cytogenetic response or 100% Philadelphia chromosome positive – because they will live longer.

Frontline treatment options for CML that are approved by the Food and Drug Administration include imatinib, dasatinib, nilotinib, and bosutinib.

Dr. Kantarjian noted that dasatinib and nilotinib bested imatinib in early analyses from clinical trials, but all three TKIs produced similar rates of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) at extended follow-up.

Dasatinib and imatinib produced similar rates of 5-year OS and PFS in the DASISION trial (J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jul 10;34[20]:2333-40).

In ENESTnd, 5-year OS and PFS rates were similar with nilotinib and imatinib (Leukemia. 2016 May;30[5]:1044-54).

However, the higher incidence of uncommon toxicities with the newer TKIs must be taken into account, Dr. Kantarjian said.

Choosing a TKI

Dr. Kantarjian recommends frontline imatinib for older patients (aged 65-70) and those who are low risk based on their Sokal score.

Second-generation TKIs should be given up front to patients who are at higher risk by Sokal and for “very young patients in whom early treatment discontinuation is important,” he said.

“In accelerated or blast phase, I always use the second-generation TKIs,” he said. “If there’s no binding mutation, I prefer dasatinib. I think it’s the most potent of them. If there are toxicities with dasatinib, bosutinib is equivalent in efficacy, so they are interchangeable.”

A TKI should not be discarded unless there is loss of complete cytogenetic response – not major molecular response – at the maximum tolerated adjusted dose that does not cause grade 3-4 toxicities or chronic grade 2 toxicities, Dr. Kantarjian added.

“We have to remember that we can go down on the dosages of, for example, imatinib, down to 200 mg a day, dasatinib as low as 20 mg a day, nilotinib as low as 150 mg twice a day or even 200 mg daily, and bosutinib down to 200 mg daily,” he said. “So if we have a patient who’s responding with side effects, we should not abandon the particular TKI, we should try to manipulate the dose schedule if they are having a good response.”

Dr. Kantarjian noted that pleural effusion is a toxicity of particular concern with dasatinib, but lowering the dose to 50 mg daily results in similar efficacy and significantly less toxicity than 100 mg daily. For patients over the age of 70, a 20-mg dose can be used.

Vaso-occlusive and vasospastic reactions are increasingly observed in patients treated with nilotinib. For that reason, Dr. Kantarjian said he prefers to forgo up-front nilotinib, particularly in patients who have cardiovascular or neurotoxic problems.

“The incidence of vaso-occlusive and vasospastic reactions is now close to 10%-15% at about 10 years with nilotinib,” Dr. Kantarjian said. “So it is not a trivial toxicity.”

For patients with vaso-occlusive/vasospastic reactions, “bosutinib is probably the safest drug,” Dr. Kantarjian said.

For second- or third-line therapy, patients can receive ponatinib or a second-generation TKI (dasatinib, nilotinib, or bosutinib), as well as omacetaxine or allogeneic stem cell transplant.

“If you disregard toxicities, I think ponatinib is the most powerful TKI, and I think that’s because we are using it at a higher dose that produces so many toxicities,” Dr. Kantarjian said.

Ponatinib is not used up front because of these toxicities, particularly pancreatitis, skin rashes, vaso-occlusive disorders, and hypertension, he added.

Dr. Kantarjian suggests giving ponatinib at 30 mg daily in patients with T315I mutation and those without guiding mutations who are resistant to second-generation TKIs.

Discontinuing a TKI

Dr. Kantarjian said patients can discontinue TKI therapy if they:

- Are low- or intermediate-risk by Sokal.

- Have quantifiable BCR-ABL transcripts.

- Are in chronic phase.

- Achieved an optimal response to their first TKI.

- Have been on TKI therapy for more than 8 years.

- Achieved a complete molecular response.

- Have had a molecular response for more than 2-3 years.

- Are available for monitoring every other month for the first 2 years.

Dr. Kantarjian did not report any conflicts of interest at the meeting. However, he has previously reported relationships with Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, and Ariad Pharmaceuticals.

The Leukemia and Lymphoma meeting is organized by Jonathan Wood & Association, which is owned by the parent company of this news organization.

REPORTING FROM LEUKEMIA AND LYMPHOMA 2018

Optimizing use of TKIs in CML

DUBROVNIK, CROATIA—Long-term efficacy and toxicity should inform decisions about tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), according to the keynote presenter at Leukemia and Lymphoma: Europe and the USA, Linking Knowledge and Practice.

Studies have indicated that long-term survival rates are similar whether CML patients receive frontline treatment with imatinib or second-generation TKIs.

However, the newer TKIs pose a higher risk of uncommon toxicities, said Hagop Kantarjian, MD, a professor at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, who gave the meeting’s keynote speech.

Dr. Kantarjian said most CML patients should receive daily treatment with TKIs—even if they are in complete cytogenetic response or 100% Ph-positive—because they will live longer.

Frontline treatment options for CML that are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration include imatinib, dasatinib, nilotinib, and bosutinib.

Dr. Kantarjian noted that dasatinib and nilotinib bested imatinib in early analyses from clinical trials, but all three TKIs produced similar rates of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) at extended follow-up.

Dasatinib and imatinib produced similar rates of 5-year OS and PFS in the DASISION trial.1 In ENESTnd, 5-year OS and PFS rates were similar with nilotinib and imatinib.2

However, Dr. Kantarjian said the higher incidence of uncommon toxicities with the newer TKIs must be taken into account.

Choosing a TKI

Dr. Kantarjian recommends frontline imatinib for older patients (≥ 65 to 70) and those who are low-risk according to Sokal score.

Second-generation TKIs should be given upfront to patients who are higher-risk by Sokal and for “very young patients in whom early treatment discontinuation is important,” according to Dr. Kantarjian.

“In accelerated or blast phase, I always use the second-generation TKIs,” he said. “If there’s no binding mutation, I prefer dasatinib. I think it’s the most potent of them. If there are toxicities with dasatinib, bosutinib is equivalent in efficacy, so they are interchangeable.”

Dr. Kantarjian also said a TKI should not be discarded unless there is loss of complete cytogenetic response (not major molecular response) at the maximum tolerated adjusted dose that does not cause grade 3-4 toxicities or chronic grade 2 toxicities.

“[W]e have to remember that we can go down on the dosages of, for example, imatinib down to 200 mg a day, dasatinib as low as 20 mg a day, nilotinib as low as 150 mg twice a day or even 200 mg daily, and bosutinib down to 200 mg daily,” Dr. Kantarjian said.

“So if we have a patient who’s responding with side effects, we should not abandon the particular TKI, we should try to manipulate the dose schedule if they are having a good response.”

Dr. Kantarjian noted that pleural effusion is a toxicity of particular concern with dasatinib, but lowering the dose to 50 mg daily results in similar efficacy and significantly less toxicity than 100 mg daily. For patients over the age of 70, a 20 mg dose can be used.

Dr. Kantarjian said vaso-occlusive and vasospastic reactions are increasingly observed in patients treated with nilotinib. Therefore, he prefers to forgo upfront nilotinib, particularly in patients who have cardiovascular or neurotoxic problems.

“The incidence of vaso-occlusive and vasospastic reactions is now close to 10% to 15% at about 10 years with nilotinib,” Dr. Kantarjian said. “So it is not a trivial toxicity.”

For patients with vaso-occlusive/vasospastic reactions, “bosutinib is probably the safest drug,” Dr. Kantarjian said.

For second- or third-line therapy, patients can receive ponatinib or a second-generation TKI (dasatinib, nilotinib, or bosutinib) as well as omacetaxine or allogeneic stem cell transplant.

“If you disregard toxicities, I think ponatinib is the most powerful TKI, and I think that’s because we are using it at a higher dose that produces so many toxicities,” Dr. Kantarjian said.

He added that the reason ponatinib is not used upfront is because of these toxicities, particularly pancreatitis, skin rashes, vaso-occlusive disorders, and hypertension.

Dr. Kantarjian suggests giving ponatinib at 30 mg daily in patients with T315I mutation and those without guiding mutations who are resistant to second-generation TKIs.

When to discontinue TKIs

Dr. Kantarjian said patients can discontinue TKI therapy if they:

- Are low- or intermediate-risk by Sokal

- Have quantifiable BCR-ABL transcripts—B2A2, B3A2 (e13a2 or e14a2)

- Are in chronic phase

- Achieved an optimal response to their first TKI

- Have been on TKI therapy for more than 8 years

- Achieved a complete molecular response (MR4.5)

- Have had a molecular response for more than 2 to 3 years

- Are available for monitoring every other month for the first 2 years.

Dr. Kantarjian did not report any conflicts of interest at the meeting. However, he has previously reported relationships with Novartis (makers of imatinib and nilotinib), Bristol-Myers Squibb (makers of dasatinib), Pfizer (makers of bosutinib), and Ariad Pharmaceuticals (makers of ponatinib, now owned by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited).

1. Cortes JE et al. J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jul 10; 34(20): 2333–2340. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.8899

2. Hochhaus A et al. Leukemia. 2016 May; 30(5): 1044–1054. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.5

DUBROVNIK, CROATIA—Long-term efficacy and toxicity should inform decisions about tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), according to the keynote presenter at Leukemia and Lymphoma: Europe and the USA, Linking Knowledge and Practice.

Studies have indicated that long-term survival rates are similar whether CML patients receive frontline treatment with imatinib or second-generation TKIs.

However, the newer TKIs pose a higher risk of uncommon toxicities, said Hagop Kantarjian, MD, a professor at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, who gave the meeting’s keynote speech.

Dr. Kantarjian said most CML patients should receive daily treatment with TKIs—even if they are in complete cytogenetic response or 100% Ph-positive—because they will live longer.

Frontline treatment options for CML that are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration include imatinib, dasatinib, nilotinib, and bosutinib.

Dr. Kantarjian noted that dasatinib and nilotinib bested imatinib in early analyses from clinical trials, but all three TKIs produced similar rates of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) at extended follow-up.

Dasatinib and imatinib produced similar rates of 5-year OS and PFS in the DASISION trial.1 In ENESTnd, 5-year OS and PFS rates were similar with nilotinib and imatinib.2

However, Dr. Kantarjian said the higher incidence of uncommon toxicities with the newer TKIs must be taken into account.

Choosing a TKI

Dr. Kantarjian recommends frontline imatinib for older patients (≥ 65 to 70) and those who are low-risk according to Sokal score.

Second-generation TKIs should be given upfront to patients who are higher-risk by Sokal and for “very young patients in whom early treatment discontinuation is important,” according to Dr. Kantarjian.

“In accelerated or blast phase, I always use the second-generation TKIs,” he said. “If there’s no binding mutation, I prefer dasatinib. I think it’s the most potent of them. If there are toxicities with dasatinib, bosutinib is equivalent in efficacy, so they are interchangeable.”

Dr. Kantarjian also said a TKI should not be discarded unless there is loss of complete cytogenetic response (not major molecular response) at the maximum tolerated adjusted dose that does not cause grade 3-4 toxicities or chronic grade 2 toxicities.

“[W]e have to remember that we can go down on the dosages of, for example, imatinib down to 200 mg a day, dasatinib as low as 20 mg a day, nilotinib as low as 150 mg twice a day or even 200 mg daily, and bosutinib down to 200 mg daily,” Dr. Kantarjian said.

“So if we have a patient who’s responding with side effects, we should not abandon the particular TKI, we should try to manipulate the dose schedule if they are having a good response.”

Dr. Kantarjian noted that pleural effusion is a toxicity of particular concern with dasatinib, but lowering the dose to 50 mg daily results in similar efficacy and significantly less toxicity than 100 mg daily. For patients over the age of 70, a 20 mg dose can be used.

Dr. Kantarjian said vaso-occlusive and vasospastic reactions are increasingly observed in patients treated with nilotinib. Therefore, he prefers to forgo upfront nilotinib, particularly in patients who have cardiovascular or neurotoxic problems.

“The incidence of vaso-occlusive and vasospastic reactions is now close to 10% to 15% at about 10 years with nilotinib,” Dr. Kantarjian said. “So it is not a trivial toxicity.”

For patients with vaso-occlusive/vasospastic reactions, “bosutinib is probably the safest drug,” Dr. Kantarjian said.

For second- or third-line therapy, patients can receive ponatinib or a second-generation TKI (dasatinib, nilotinib, or bosutinib) as well as omacetaxine or allogeneic stem cell transplant.

“If you disregard toxicities, I think ponatinib is the most powerful TKI, and I think that’s because we are using it at a higher dose that produces so many toxicities,” Dr. Kantarjian said.

He added that the reason ponatinib is not used upfront is because of these toxicities, particularly pancreatitis, skin rashes, vaso-occlusive disorders, and hypertension.

Dr. Kantarjian suggests giving ponatinib at 30 mg daily in patients with T315I mutation and those without guiding mutations who are resistant to second-generation TKIs.

When to discontinue TKIs

Dr. Kantarjian said patients can discontinue TKI therapy if they:

- Are low- or intermediate-risk by Sokal

- Have quantifiable BCR-ABL transcripts—B2A2, B3A2 (e13a2 or e14a2)

- Are in chronic phase

- Achieved an optimal response to their first TKI

- Have been on TKI therapy for more than 8 years

- Achieved a complete molecular response (MR4.5)

- Have had a molecular response for more than 2 to 3 years

- Are available for monitoring every other month for the first 2 years.

Dr. Kantarjian did not report any conflicts of interest at the meeting. However, he has previously reported relationships with Novartis (makers of imatinib and nilotinib), Bristol-Myers Squibb (makers of dasatinib), Pfizer (makers of bosutinib), and Ariad Pharmaceuticals (makers of ponatinib, now owned by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited).

1. Cortes JE et al. J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jul 10; 34(20): 2333–2340. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.8899

2. Hochhaus A et al. Leukemia. 2016 May; 30(5): 1044–1054. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.5

DUBROVNIK, CROATIA—Long-term efficacy and toxicity should inform decisions about tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), according to the keynote presenter at Leukemia and Lymphoma: Europe and the USA, Linking Knowledge and Practice.

Studies have indicated that long-term survival rates are similar whether CML patients receive frontline treatment with imatinib or second-generation TKIs.

However, the newer TKIs pose a higher risk of uncommon toxicities, said Hagop Kantarjian, MD, a professor at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, who gave the meeting’s keynote speech.

Dr. Kantarjian said most CML patients should receive daily treatment with TKIs—even if they are in complete cytogenetic response or 100% Ph-positive—because they will live longer.

Frontline treatment options for CML that are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration include imatinib, dasatinib, nilotinib, and bosutinib.

Dr. Kantarjian noted that dasatinib and nilotinib bested imatinib in early analyses from clinical trials, but all three TKIs produced similar rates of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) at extended follow-up.

Dasatinib and imatinib produced similar rates of 5-year OS and PFS in the DASISION trial.1 In ENESTnd, 5-year OS and PFS rates were similar with nilotinib and imatinib.2

However, Dr. Kantarjian said the higher incidence of uncommon toxicities with the newer TKIs must be taken into account.

Choosing a TKI

Dr. Kantarjian recommends frontline imatinib for older patients (≥ 65 to 70) and those who are low-risk according to Sokal score.

Second-generation TKIs should be given upfront to patients who are higher-risk by Sokal and for “very young patients in whom early treatment discontinuation is important,” according to Dr. Kantarjian.

“In accelerated or blast phase, I always use the second-generation TKIs,” he said. “If there’s no binding mutation, I prefer dasatinib. I think it’s the most potent of them. If there are toxicities with dasatinib, bosutinib is equivalent in efficacy, so they are interchangeable.”

Dr. Kantarjian also said a TKI should not be discarded unless there is loss of complete cytogenetic response (not major molecular response) at the maximum tolerated adjusted dose that does not cause grade 3-4 toxicities or chronic grade 2 toxicities.

“[W]e have to remember that we can go down on the dosages of, for example, imatinib down to 200 mg a day, dasatinib as low as 20 mg a day, nilotinib as low as 150 mg twice a day or even 200 mg daily, and bosutinib down to 200 mg daily,” Dr. Kantarjian said.

“So if we have a patient who’s responding with side effects, we should not abandon the particular TKI, we should try to manipulate the dose schedule if they are having a good response.”

Dr. Kantarjian noted that pleural effusion is a toxicity of particular concern with dasatinib, but lowering the dose to 50 mg daily results in similar efficacy and significantly less toxicity than 100 mg daily. For patients over the age of 70, a 20 mg dose can be used.

Dr. Kantarjian said vaso-occlusive and vasospastic reactions are increasingly observed in patients treated with nilotinib. Therefore, he prefers to forgo upfront nilotinib, particularly in patients who have cardiovascular or neurotoxic problems.

“The incidence of vaso-occlusive and vasospastic reactions is now close to 10% to 15% at about 10 years with nilotinib,” Dr. Kantarjian said. “So it is not a trivial toxicity.”

For patients with vaso-occlusive/vasospastic reactions, “bosutinib is probably the safest drug,” Dr. Kantarjian said.

For second- or third-line therapy, patients can receive ponatinib or a second-generation TKI (dasatinib, nilotinib, or bosutinib) as well as omacetaxine or allogeneic stem cell transplant.

“If you disregard toxicities, I think ponatinib is the most powerful TKI, and I think that’s because we are using it at a higher dose that produces so many toxicities,” Dr. Kantarjian said.

He added that the reason ponatinib is not used upfront is because of these toxicities, particularly pancreatitis, skin rashes, vaso-occlusive disorders, and hypertension.

Dr. Kantarjian suggests giving ponatinib at 30 mg daily in patients with T315I mutation and those without guiding mutations who are resistant to second-generation TKIs.

When to discontinue TKIs

Dr. Kantarjian said patients can discontinue TKI therapy if they:

- Are low- or intermediate-risk by Sokal

- Have quantifiable BCR-ABL transcripts—B2A2, B3A2 (e13a2 or e14a2)

- Are in chronic phase

- Achieved an optimal response to their first TKI

- Have been on TKI therapy for more than 8 years

- Achieved a complete molecular response (MR4.5)

- Have had a molecular response for more than 2 to 3 years

- Are available for monitoring every other month for the first 2 years.

Dr. Kantarjian did not report any conflicts of interest at the meeting. However, he has previously reported relationships with Novartis (makers of imatinib and nilotinib), Bristol-Myers Squibb (makers of dasatinib), Pfizer (makers of bosutinib), and Ariad Pharmaceuticals (makers of ponatinib, now owned by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited).

1. Cortes JE et al. J Clin Oncol. 2016 Jul 10; 34(20): 2333–2340. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.8899

2. Hochhaus A et al. Leukemia. 2016 May; 30(5): 1044–1054. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.5

TKI discontinuation appears safe in CML

NEW YORK – Despite initial concerns that stopping tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment would be ill-advised in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), clinical trial data suggest it is a safe and reasonable strategy, according to a leading expert.

“About 95% of people in all of these trials will regain their original response when they start off on therapy again,” said Jerald P. Radich, MD, of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance.

“There’s been a few that don’t, but blast crisis has been very, very rare, thank goodness, so it looks to be fairly safe for now,” Dr. Radich said at the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Hematologic Malignancies Annual Congress.

That being said, careful follow up is still required, Dr. Radich cautioned, noting that there was still an excess of CML in Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bomb survivors evident decades after radiation exposure.

“CML is a very strange disease,” he said. “You can’t eliminate the possibility of some slow-growing clone that, once you take [a patient] off tyrosine kinase therapy, is going into an accelerated phase and might take years to manifest itself.”

In one of the latest reports to shed light on what happens after discontinuation, investigators for the ENESTop study reported that treatment-free remission “seems achievable” in patients who have sustained, deep remissions after discontinuing nilotinib second-line therapy (Ann Intern Med. 2018 Apr 3;168[7]:461-70).

In ENESTop, chronic phase CML patients on tyrosine kinase inhibitors for at least 3 years were eligible to discontinue therapy if they achieved MR4.5 (BCR-ABL1IS of 0.0032% or less) and maintained that response level during a 1-year consolidation phase.

Out of 163 patients in the study, 126 met the criteria to enter the treatment-free remission phase; of that subset, 58% maintained treatment-free remission at 48 weeks, while 53% maintained it at 96 weeks, investigators said.

For 56 patients who restarted nilotinib, 55 regained at least major molecular response (MMR), and 52 regained MR4.5, while none had progression to accelerated phase or blast crisis, according to the report.

Similarly, earlier reported results from the ENESTfreedom trial showed that, of 190 patients entering the treatment-free remission phase after a median duration of 43.5 months on nilotinib, more than half remained in MMR or better at 48 weeks (Leukemia. 2017 Jul;31[7]:1525-31).

Of 86 patients who started nilotinib again after losing MMR, 98.8% regained MMR and 88.4% regained MR4.5 by the data cutoff date for the trial.

Duration and depth of response may make a “little bit of difference” in likelihood of relapse, Dr. Radich added.

In an interim analysis of a prospective multicenter, nonrandomized European discontinuation trial (EURO-SKI), investigators found that patients achieving deep molecular responses had good molecular relapse-free survival (Lancet Oncol. 2018 Jun;19[6]:747-57).

Based on that, investigators suggested that patients with deep molecular responses should be considered for discontinuation to spare them from side effects and to reduce health expenditures.

Results of these and other trials are “pretty much unbelievable,” Dr. Radich said. That’s in part because mathematical modeling – extrapolated from early trials – had suggested it could take nearly 50 years to completely eradicate minimal residual disease with tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and that the cumulative cure rate after 30 years of treatment could be as low as 31%.

Dr. Radich reported financial disclosures related to Amgen, Novartis, and Seattle Genetics.

NEW YORK – Despite initial concerns that stopping tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment would be ill-advised in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), clinical trial data suggest it is a safe and reasonable strategy, according to a leading expert.

“About 95% of people in all of these trials will regain their original response when they start off on therapy again,” said Jerald P. Radich, MD, of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance.

“There’s been a few that don’t, but blast crisis has been very, very rare, thank goodness, so it looks to be fairly safe for now,” Dr. Radich said at the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Hematologic Malignancies Annual Congress.

That being said, careful follow up is still required, Dr. Radich cautioned, noting that there was still an excess of CML in Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bomb survivors evident decades after radiation exposure.

“CML is a very strange disease,” he said. “You can’t eliminate the possibility of some slow-growing clone that, once you take [a patient] off tyrosine kinase therapy, is going into an accelerated phase and might take years to manifest itself.”

In one of the latest reports to shed light on what happens after discontinuation, investigators for the ENESTop study reported that treatment-free remission “seems achievable” in patients who have sustained, deep remissions after discontinuing nilotinib second-line therapy (Ann Intern Med. 2018 Apr 3;168[7]:461-70).

In ENESTop, chronic phase CML patients on tyrosine kinase inhibitors for at least 3 years were eligible to discontinue therapy if they achieved MR4.5 (BCR-ABL1IS of 0.0032% or less) and maintained that response level during a 1-year consolidation phase.

Out of 163 patients in the study, 126 met the criteria to enter the treatment-free remission phase; of that subset, 58% maintained treatment-free remission at 48 weeks, while 53% maintained it at 96 weeks, investigators said.

For 56 patients who restarted nilotinib, 55 regained at least major molecular response (MMR), and 52 regained MR4.5, while none had progression to accelerated phase or blast crisis, according to the report.

Similarly, earlier reported results from the ENESTfreedom trial showed that, of 190 patients entering the treatment-free remission phase after a median duration of 43.5 months on nilotinib, more than half remained in MMR or better at 48 weeks (Leukemia. 2017 Jul;31[7]:1525-31).

Of 86 patients who started nilotinib again after losing MMR, 98.8% regained MMR and 88.4% regained MR4.5 by the data cutoff date for the trial.

Duration and depth of response may make a “little bit of difference” in likelihood of relapse, Dr. Radich added.

In an interim analysis of a prospective multicenter, nonrandomized European discontinuation trial (EURO-SKI), investigators found that patients achieving deep molecular responses had good molecular relapse-free survival (Lancet Oncol. 2018 Jun;19[6]:747-57).

Based on that, investigators suggested that patients with deep molecular responses should be considered for discontinuation to spare them from side effects and to reduce health expenditures.

Results of these and other trials are “pretty much unbelievable,” Dr. Radich said. That’s in part because mathematical modeling – extrapolated from early trials – had suggested it could take nearly 50 years to completely eradicate minimal residual disease with tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and that the cumulative cure rate after 30 years of treatment could be as low as 31%.

Dr. Radich reported financial disclosures related to Amgen, Novartis, and Seattle Genetics.

NEW YORK – Despite initial concerns that stopping tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment would be ill-advised in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), clinical trial data suggest it is a safe and reasonable strategy, according to a leading expert.

“About 95% of people in all of these trials will regain their original response when they start off on therapy again,” said Jerald P. Radich, MD, of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance.

“There’s been a few that don’t, but blast crisis has been very, very rare, thank goodness, so it looks to be fairly safe for now,” Dr. Radich said at the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Hematologic Malignancies Annual Congress.

That being said, careful follow up is still required, Dr. Radich cautioned, noting that there was still an excess of CML in Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bomb survivors evident decades after radiation exposure.

“CML is a very strange disease,” he said. “You can’t eliminate the possibility of some slow-growing clone that, once you take [a patient] off tyrosine kinase therapy, is going into an accelerated phase and might take years to manifest itself.”

In one of the latest reports to shed light on what happens after discontinuation, investigators for the ENESTop study reported that treatment-free remission “seems achievable” in patients who have sustained, deep remissions after discontinuing nilotinib second-line therapy (Ann Intern Med. 2018 Apr 3;168[7]:461-70).

In ENESTop, chronic phase CML patients on tyrosine kinase inhibitors for at least 3 years were eligible to discontinue therapy if they achieved MR4.5 (BCR-ABL1IS of 0.0032% or less) and maintained that response level during a 1-year consolidation phase.

Out of 163 patients in the study, 126 met the criteria to enter the treatment-free remission phase; of that subset, 58% maintained treatment-free remission at 48 weeks, while 53% maintained it at 96 weeks, investigators said.

For 56 patients who restarted nilotinib, 55 regained at least major molecular response (MMR), and 52 regained MR4.5, while none had progression to accelerated phase or blast crisis, according to the report.

Similarly, earlier reported results from the ENESTfreedom trial showed that, of 190 patients entering the treatment-free remission phase after a median duration of 43.5 months on nilotinib, more than half remained in MMR or better at 48 weeks (Leukemia. 2017 Jul;31[7]:1525-31).

Of 86 patients who started nilotinib again after losing MMR, 98.8% regained MMR and 88.4% regained MR4.5 by the data cutoff date for the trial.

Duration and depth of response may make a “little bit of difference” in likelihood of relapse, Dr. Radich added.

In an interim analysis of a prospective multicenter, nonrandomized European discontinuation trial (EURO-SKI), investigators found that patients achieving deep molecular responses had good molecular relapse-free survival (Lancet Oncol. 2018 Jun;19[6]:747-57).

Based on that, investigators suggested that patients with deep molecular responses should be considered for discontinuation to spare them from side effects and to reduce health expenditures.

Results of these and other trials are “pretty much unbelievable,” Dr. Radich said. That’s in part because mathematical modeling – extrapolated from early trials – had suggested it could take nearly 50 years to completely eradicate minimal residual disease with tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and that the cumulative cure rate after 30 years of treatment could be as low as 31%.

Dr. Radich reported financial disclosures related to Amgen, Novartis, and Seattle Genetics.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM NCCN HEMATOLOGIC MALIGNANCIES

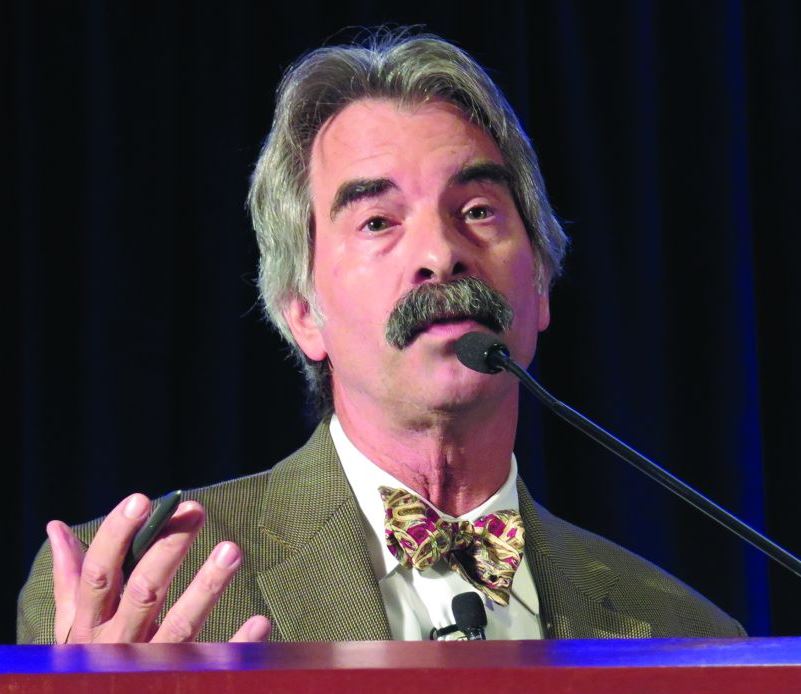

AMP publishes report on DNA variants in CMNs

A new report addresses the clinical relevance of DNA variants in chronic myeloid neoplasms (CMNs).

The report is intended to aid clinical laboratory professionals with the management of most CMNs and the development of high-throughput pan-myeloid sequencing testing panels.

The authors list 34 genes they consider “critical” for sequencing tests to help standardize clinical practice and improve care of patients with CMNs.

The Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) established a CMN Working Group to generate the report, which was published in The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics.

“The molecular pathology community has witnessed a recent explosion of scientific literature highlighting the clinical significance of small DNA variants in CMNs,” said Rebecca F. McClure, MD, a member of the AMP CMN Working Group and an associate professor at Health Sciences North/Horizon Santé-Nord in Sudbury, Ontario, Canada.

“AMP’s working group recognized a clear, unmet need for evidence-based recommendations to assist in the development of the high-quality pan-myeloid gene panels that provide relevant diagnostic and prognostic information and enable monitoring of clonal architecture.”

The increasing availability of targeted, high-throughput, next-generation sequencing panels has enabled scientists to explore the genetic heterogeneity and clinical relevance of the small DNA variants in CMNs.

However, the biological complexity and multiple forms of CMNs have led to variability in the genes included on the available panels that are used to make an accurate diagnosis, provide reliable prognostic information, and select an appropriate therapy based on DNA variant profiles present at various time points.

AMP established its CMN Working Group to review the published literature on CMNs, summarize key findings that support clinical utility, and define a set of critical gene inclusions for all high-throughput pan-myeloid sequencing testing panels.

The group proposed the following 34 genes as a minimum recommended testing list: ASXL1, BCOR, BCORL1, CALR, CBL, CEBPA, CSF3R, DNMT3A, ETV6, EZH2, FLT3, IDH1, IDH2, JAK2, KIT, KRAS, MPL, NF1, NPM1, NRAS, PHF6, PPM1D, PTPN11, RAD21, RUNX1, SETBP1, SF3B1, SMC3, SRSF2, STAG2, TET2, TP53, U2AF1, and ZRSR2.

“While the goal of the study was to distill the literature for molecular pathologists, in doing so, we also revealed recurrent mutational patterns of clonal evolution that will [help] hematologist/oncologists, researchers, and pathologists understand how to interpret the results of these panels as they reveal critical biology of the neoplasms,” said Annette S. Kim, MD, PhD, CMN Working Group Chair and an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

A new report addresses the clinical relevance of DNA variants in chronic myeloid neoplasms (CMNs).

The report is intended to aid clinical laboratory professionals with the management of most CMNs and the development of high-throughput pan-myeloid sequencing testing panels.

The authors list 34 genes they consider “critical” for sequencing tests to help standardize clinical practice and improve care of patients with CMNs.

The Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) established a CMN Working Group to generate the report, which was published in The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics.

“The molecular pathology community has witnessed a recent explosion of scientific literature highlighting the clinical significance of small DNA variants in CMNs,” said Rebecca F. McClure, MD, a member of the AMP CMN Working Group and an associate professor at Health Sciences North/Horizon Santé-Nord in Sudbury, Ontario, Canada.

“AMP’s working group recognized a clear, unmet need for evidence-based recommendations to assist in the development of the high-quality pan-myeloid gene panels that provide relevant diagnostic and prognostic information and enable monitoring of clonal architecture.”

The increasing availability of targeted, high-throughput, next-generation sequencing panels has enabled scientists to explore the genetic heterogeneity and clinical relevance of the small DNA variants in CMNs.

However, the biological complexity and multiple forms of CMNs have led to variability in the genes included on the available panels that are used to make an accurate diagnosis, provide reliable prognostic information, and select an appropriate therapy based on DNA variant profiles present at various time points.

AMP established its CMN Working Group to review the published literature on CMNs, summarize key findings that support clinical utility, and define a set of critical gene inclusions for all high-throughput pan-myeloid sequencing testing panels.

The group proposed the following 34 genes as a minimum recommended testing list: ASXL1, BCOR, BCORL1, CALR, CBL, CEBPA, CSF3R, DNMT3A, ETV6, EZH2, FLT3, IDH1, IDH2, JAK2, KIT, KRAS, MPL, NF1, NPM1, NRAS, PHF6, PPM1D, PTPN11, RAD21, RUNX1, SETBP1, SF3B1, SMC3, SRSF2, STAG2, TET2, TP53, U2AF1, and ZRSR2.

“While the goal of the study was to distill the literature for molecular pathologists, in doing so, we also revealed recurrent mutational patterns of clonal evolution that will [help] hematologist/oncologists, researchers, and pathologists understand how to interpret the results of these panels as they reveal critical biology of the neoplasms,” said Annette S. Kim, MD, PhD, CMN Working Group Chair and an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

A new report addresses the clinical relevance of DNA variants in chronic myeloid neoplasms (CMNs).

The report is intended to aid clinical laboratory professionals with the management of most CMNs and the development of high-throughput pan-myeloid sequencing testing panels.

The authors list 34 genes they consider “critical” for sequencing tests to help standardize clinical practice and improve care of patients with CMNs.

The Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) established a CMN Working Group to generate the report, which was published in The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics.

“The molecular pathology community has witnessed a recent explosion of scientific literature highlighting the clinical significance of small DNA variants in CMNs,” said Rebecca F. McClure, MD, a member of the AMP CMN Working Group and an associate professor at Health Sciences North/Horizon Santé-Nord in Sudbury, Ontario, Canada.

“AMP’s working group recognized a clear, unmet need for evidence-based recommendations to assist in the development of the high-quality pan-myeloid gene panels that provide relevant diagnostic and prognostic information and enable monitoring of clonal architecture.”

The increasing availability of targeted, high-throughput, next-generation sequencing panels has enabled scientists to explore the genetic heterogeneity and clinical relevance of the small DNA variants in CMNs.

However, the biological complexity and multiple forms of CMNs have led to variability in the genes included on the available panels that are used to make an accurate diagnosis, provide reliable prognostic information, and select an appropriate therapy based on DNA variant profiles present at various time points.

AMP established its CMN Working Group to review the published literature on CMNs, summarize key findings that support clinical utility, and define a set of critical gene inclusions for all high-throughput pan-myeloid sequencing testing panels.

The group proposed the following 34 genes as a minimum recommended testing list: ASXL1, BCOR, BCORL1, CALR, CBL, CEBPA, CSF3R, DNMT3A, ETV6, EZH2, FLT3, IDH1, IDH2, JAK2, KIT, KRAS, MPL, NF1, NPM1, NRAS, PHF6, PPM1D, PTPN11, RAD21, RUNX1, SETBP1, SF3B1, SMC3, SRSF2, STAG2, TET2, TP53, U2AF1, and ZRSR2.

“While the goal of the study was to distill the literature for molecular pathologists, in doing so, we also revealed recurrent mutational patterns of clonal evolution that will [help] hematologist/oncologists, researchers, and pathologists understand how to interpret the results of these panels as they reveal critical biology of the neoplasms,” said Annette S. Kim, MD, PhD, CMN Working Group Chair and an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

Familial risk of myeloid malignancies

A large study has revealed “the strongest evidence yet” supporting genetic susceptibility to myeloid malignancies, according to a researcher.

The study showed that first-degree relatives of patients with myeloid malignancies had double the risk of developing a myeloid malignancy themselves, when compared to the general population.

The researchers observed significant risks for developing acute myeloid leukemia (AML), myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), essential thrombocythemia (ET), and polycythemia vera (PV).

“Our study provides the strongest evidence yet for inherited risk for these diseases—evidence that has proved evasive before, in part, because these cancers are relatively uncommon, and our ability to characterize these diseases has, until recently, been limited,” said Amit Sud, MBChB, PhD, of The Institute of Cancer Research in London, UK.

Dr Sud and his colleagues described their research in a letter to Blood.

The researchers analyzed data from the Swedish Family-Cancer Database, which included 93,199 first-degree relatives of 35,037 patients with myeloid malignancies. The patients had been diagnosed between 1958 and 2015.

First-degree relatives of the patients had an increased risk of all myeloid malignancies, with a standardized incidence ratio (SIR) of 1.99 (95% CI 1.12-2.04).

For individual diseases, there was a significant association between family history and increased risk for:

- AML—SIR=1.53 (95% CI 1.21-2.17)

- ET—SIR=6.30 (95% CI 3.95-9.54)

- MDS—SIR=6.87 (95% CI 4.07-10.86)

- PV—SIR=7.66 (95% CI 5.74-10.02).

Dr Sud and his colleagues noted that the strongest familial relative risks tended to occur for the same disease, but there were significant associations between different myeloid malignancies as well.

Risk by age group

The researchers also looked at familial relative risk for the same disease by patients’ age at diagnosis and observed a significantly increased risk for younger cases for all myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) combined, PV, and MDS.

The SIRs for MPNs were 6.46 (95% CI 5.12-8.04) for patients age 59 or younger and 4.15 (95% CI 3.38-5.04) for patients older than 59.

The SIRs for PV were 10.90 (95% CI 7.12-15.97) for patients age 59 or younger and 5.96 (95% CI 3.93-8.67) for patients older than 59.

The SIRs for MDS were 11.95 (95% CI 6.36-20.43) for patients age 68 or younger and 3.27 (95% CI 1.06-7.63) for patients older than 68.

Risk by number of relatives

Dr Sud and his colleagues also discovered that familial relative risks of all myeloid malignancies and MPNs were significantly associated with the number of first-degree relatives affected by myeloid malignancies or MPNs.

The SIRs for first-degree relatives with 2 or more affected relatives were 4.55 (95% CI 2.08-8.64) for all myeloid malignancies and 17.82 (95% CI 5.79-24.89) for MPNs.

The SIRs for first-degree relatives with 1 affected relative were 1.96 (95% CI 1.79-2.15) for all myeloid malignancies and 4.83 (95% CI 4.14-5.60) for MPNs.

The researchers said these results suggest inherited genetic changes increase the risk of myeloid malignancies, although environmental factors shared in families could also play a role.

“In the future, our findings could help identify people at higher risk than normal because of their family background who could be prioritized for medical help like screening to catch the disease earlier if it arises,” Dr Sud said.

This study was funded by German Cancer Aid, the Swedish Research Council, ALF funding from Region Skåne, DKFZ, and Bloodwise.

A large study has revealed “the strongest evidence yet” supporting genetic susceptibility to myeloid malignancies, according to a researcher.

The study showed that first-degree relatives of patients with myeloid malignancies had double the risk of developing a myeloid malignancy themselves, when compared to the general population.

The researchers observed significant risks for developing acute myeloid leukemia (AML), myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), essential thrombocythemia (ET), and polycythemia vera (PV).

“Our study provides the strongest evidence yet for inherited risk for these diseases—evidence that has proved evasive before, in part, because these cancers are relatively uncommon, and our ability to characterize these diseases has, until recently, been limited,” said Amit Sud, MBChB, PhD, of The Institute of Cancer Research in London, UK.

Dr Sud and his colleagues described their research in a letter to Blood.

The researchers analyzed data from the Swedish Family-Cancer Database, which included 93,199 first-degree relatives of 35,037 patients with myeloid malignancies. The patients had been diagnosed between 1958 and 2015.

First-degree relatives of the patients had an increased risk of all myeloid malignancies, with a standardized incidence ratio (SIR) of 1.99 (95% CI 1.12-2.04).

For individual diseases, there was a significant association between family history and increased risk for:

- AML—SIR=1.53 (95% CI 1.21-2.17)

- ET—SIR=6.30 (95% CI 3.95-9.54)

- MDS—SIR=6.87 (95% CI 4.07-10.86)

- PV—SIR=7.66 (95% CI 5.74-10.02).

Dr Sud and his colleagues noted that the strongest familial relative risks tended to occur for the same disease, but there were significant associations between different myeloid malignancies as well.

Risk by age group

The researchers also looked at familial relative risk for the same disease by patients’ age at diagnosis and observed a significantly increased risk for younger cases for all myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) combined, PV, and MDS.

The SIRs for MPNs were 6.46 (95% CI 5.12-8.04) for patients age 59 or younger and 4.15 (95% CI 3.38-5.04) for patients older than 59.

The SIRs for PV were 10.90 (95% CI 7.12-15.97) for patients age 59 or younger and 5.96 (95% CI 3.93-8.67) for patients older than 59.

The SIRs for MDS were 11.95 (95% CI 6.36-20.43) for patients age 68 or younger and 3.27 (95% CI 1.06-7.63) for patients older than 68.

Risk by number of relatives

Dr Sud and his colleagues also discovered that familial relative risks of all myeloid malignancies and MPNs were significantly associated with the number of first-degree relatives affected by myeloid malignancies or MPNs.

The SIRs for first-degree relatives with 2 or more affected relatives were 4.55 (95% CI 2.08-8.64) for all myeloid malignancies and 17.82 (95% CI 5.79-24.89) for MPNs.

The SIRs for first-degree relatives with 1 affected relative were 1.96 (95% CI 1.79-2.15) for all myeloid malignancies and 4.83 (95% CI 4.14-5.60) for MPNs.

The researchers said these results suggest inherited genetic changes increase the risk of myeloid malignancies, although environmental factors shared in families could also play a role.

“In the future, our findings could help identify people at higher risk than normal because of their family background who could be prioritized for medical help like screening to catch the disease earlier if it arises,” Dr Sud said.

This study was funded by German Cancer Aid, the Swedish Research Council, ALF funding from Region Skåne, DKFZ, and Bloodwise.

A large study has revealed “the strongest evidence yet” supporting genetic susceptibility to myeloid malignancies, according to a researcher.

The study showed that first-degree relatives of patients with myeloid malignancies had double the risk of developing a myeloid malignancy themselves, when compared to the general population.

The researchers observed significant risks for developing acute myeloid leukemia (AML), myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), essential thrombocythemia (ET), and polycythemia vera (PV).

“Our study provides the strongest evidence yet for inherited risk for these diseases—evidence that has proved evasive before, in part, because these cancers are relatively uncommon, and our ability to characterize these diseases has, until recently, been limited,” said Amit Sud, MBChB, PhD, of The Institute of Cancer Research in London, UK.

Dr Sud and his colleagues described their research in a letter to Blood.

The researchers analyzed data from the Swedish Family-Cancer Database, which included 93,199 first-degree relatives of 35,037 patients with myeloid malignancies. The patients had been diagnosed between 1958 and 2015.

First-degree relatives of the patients had an increased risk of all myeloid malignancies, with a standardized incidence ratio (SIR) of 1.99 (95% CI 1.12-2.04).

For individual diseases, there was a significant association between family history and increased risk for:

- AML—SIR=1.53 (95% CI 1.21-2.17)

- ET—SIR=6.30 (95% CI 3.95-9.54)

- MDS—SIR=6.87 (95% CI 4.07-10.86)

- PV—SIR=7.66 (95% CI 5.74-10.02).

Dr Sud and his colleagues noted that the strongest familial relative risks tended to occur for the same disease, but there were significant associations between different myeloid malignancies as well.

Risk by age group

The researchers also looked at familial relative risk for the same disease by patients’ age at diagnosis and observed a significantly increased risk for younger cases for all myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) combined, PV, and MDS.

The SIRs for MPNs were 6.46 (95% CI 5.12-8.04) for patients age 59 or younger and 4.15 (95% CI 3.38-5.04) for patients older than 59.

The SIRs for PV were 10.90 (95% CI 7.12-15.97) for patients age 59 or younger and 5.96 (95% CI 3.93-8.67) for patients older than 59.

The SIRs for MDS were 11.95 (95% CI 6.36-20.43) for patients age 68 or younger and 3.27 (95% CI 1.06-7.63) for patients older than 68.

Risk by number of relatives

Dr Sud and his colleagues also discovered that familial relative risks of all myeloid malignancies and MPNs were significantly associated with the number of first-degree relatives affected by myeloid malignancies or MPNs.

The SIRs for first-degree relatives with 2 or more affected relatives were 4.55 (95% CI 2.08-8.64) for all myeloid malignancies and 17.82 (95% CI 5.79-24.89) for MPNs.

The SIRs for first-degree relatives with 1 affected relative were 1.96 (95% CI 1.79-2.15) for all myeloid malignancies and 4.83 (95% CI 4.14-5.60) for MPNs.

The researchers said these results suggest inherited genetic changes increase the risk of myeloid malignancies, although environmental factors shared in families could also play a role.

“In the future, our findings could help identify people at higher risk than normal because of their family background who could be prioritized for medical help like screening to catch the disease earlier if it arises,” Dr Sud said.

This study was funded by German Cancer Aid, the Swedish Research Council, ALF funding from Region Skåne, DKFZ, and Bloodwise.

Global burden of hematologic malignancies

Research has shown an increase in the global incidence of leukemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in recent years.

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study showed that, from 2006 to 2016, the incidence of NHL increased 45%, and the incidence of leukemia increased 26%.

These increases were largely due to population growth and aging.

Results from the GDB study were published in JAMA Oncology.

The study indicated that, in 2016, there were 17.2 million cases of cancer worldwide and 8.9 million cancer deaths.

One in 3 men were likely to get cancer during their lifetime, as were 1 in 5 women. Cancer was associated with 213.2 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs).

The following table lists the 2016 global incidence and mortality figures for all cancers combined and for individual hematologic malignancies.

| Cancer type | Cases, thousands | Deaths, thousands |

| All cancers | 17,228 | 8927 |

| Leukemias | 467 | 310 |

| Acute lymphoid leukemia | 76 | 51 |

| Chronic lymphoid leukemia | 105 | 35 |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 103 | 85 |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 32 | 22 |

| Other leukemias | 150 | 117 |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 73 | 29 |

| NHL | 461 | 240 |

| Multiple myeloma | 139 | 98 |

Leukemia

In 2016, there were 467,000 new cases of leukemia and 310,000 leukemia deaths. Leukemia was responsible for 10.2 million DALYs. Leukemia developed in 1 in 118 men and 1 in 194 women worldwide.

Between 2006 and 2016, the global leukemia incidence increased by 26%—from 370,482 to 466,802 cases.

The researchers said the factors contributing to this increase were population growth (12%), population aging (10%), and an increase in age-specific incidence rates (3%).

NHL

In 2016, there were 461,000 new cases of NHL and 240,000 NHL deaths. NHL was responsible for 6.8 million DALYs. NHL developed in 1 in 110 men and 1 in 161 women worldwide.

Between 2006 and 2016, NHL increased by 45%, from 319,078 to 461,164 cases.

The factors contributing to this increase were increasing age-specific incidence rates (17%), changing population age structure (15%), and population growth (12%).

“A large proportion of the increase in cancer incidence can be explained by improving life expectancy and population growth—a development that can at least partially be attributed to a reduced burden from other common diseases,” the study authors wrote.

The authors also pointed out that prevention efforts are less effective for hematologic malignancies than for other cancers.

Research has shown an increase in the global incidence of leukemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in recent years.

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study showed that, from 2006 to 2016, the incidence of NHL increased 45%, and the incidence of leukemia increased 26%.

These increases were largely due to population growth and aging.

Results from the GDB study were published in JAMA Oncology.

The study indicated that, in 2016, there were 17.2 million cases of cancer worldwide and 8.9 million cancer deaths.

One in 3 men were likely to get cancer during their lifetime, as were 1 in 5 women. Cancer was associated with 213.2 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs).

The following table lists the 2016 global incidence and mortality figures for all cancers combined and for individual hematologic malignancies.

| Cancer type | Cases, thousands | Deaths, thousands |

| All cancers | 17,228 | 8927 |

| Leukemias | 467 | 310 |

| Acute lymphoid leukemia | 76 | 51 |

| Chronic lymphoid leukemia | 105 | 35 |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 103 | 85 |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 32 | 22 |

| Other leukemias | 150 | 117 |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 73 | 29 |

| NHL | 461 | 240 |

| Multiple myeloma | 139 | 98 |

Leukemia

In 2016, there were 467,000 new cases of leukemia and 310,000 leukemia deaths. Leukemia was responsible for 10.2 million DALYs. Leukemia developed in 1 in 118 men and 1 in 194 women worldwide.

Between 2006 and 2016, the global leukemia incidence increased by 26%—from 370,482 to 466,802 cases.

The researchers said the factors contributing to this increase were population growth (12%), population aging (10%), and an increase in age-specific incidence rates (3%).

NHL

In 2016, there were 461,000 new cases of NHL and 240,000 NHL deaths. NHL was responsible for 6.8 million DALYs. NHL developed in 1 in 110 men and 1 in 161 women worldwide.

Between 2006 and 2016, NHL increased by 45%, from 319,078 to 461,164 cases.

The factors contributing to this increase were increasing age-specific incidence rates (17%), changing population age structure (15%), and population growth (12%).

“A large proportion of the increase in cancer incidence can be explained by improving life expectancy and population growth—a development that can at least partially be attributed to a reduced burden from other common diseases,” the study authors wrote.

The authors also pointed out that prevention efforts are less effective for hematologic malignancies than for other cancers.

Research has shown an increase in the global incidence of leukemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in recent years.

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study showed that, from 2006 to 2016, the incidence of NHL increased 45%, and the incidence of leukemia increased 26%.

These increases were largely due to population growth and aging.

Results from the GDB study were published in JAMA Oncology.

The study indicated that, in 2016, there were 17.2 million cases of cancer worldwide and 8.9 million cancer deaths.

One in 3 men were likely to get cancer during their lifetime, as were 1 in 5 women. Cancer was associated with 213.2 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs).

The following table lists the 2016 global incidence and mortality figures for all cancers combined and for individual hematologic malignancies.

| Cancer type | Cases, thousands | Deaths, thousands |

| All cancers | 17,228 | 8927 |

| Leukemias | 467 | 310 |

| Acute lymphoid leukemia | 76 | 51 |

| Chronic lymphoid leukemia | 105 | 35 |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 103 | 85 |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 32 | 22 |

| Other leukemias | 150 | 117 |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 73 | 29 |

| NHL | 461 | 240 |

| Multiple myeloma | 139 | 98 |

Leukemia

In 2016, there were 467,000 new cases of leukemia and 310,000 leukemia deaths. Leukemia was responsible for 10.2 million DALYs. Leukemia developed in 1 in 118 men and 1 in 194 women worldwide.

Between 2006 and 2016, the global leukemia incidence increased by 26%—from 370,482 to 466,802 cases.

The researchers said the factors contributing to this increase were population growth (12%), population aging (10%), and an increase in age-specific incidence rates (3%).

NHL

In 2016, there were 461,000 new cases of NHL and 240,000 NHL deaths. NHL was responsible for 6.8 million DALYs. NHL developed in 1 in 110 men and 1 in 161 women worldwide.

Between 2006 and 2016, NHL increased by 45%, from 319,078 to 461,164 cases.

The factors contributing to this increase were increasing age-specific incidence rates (17%), changing population age structure (15%), and population growth (12%).

“A large proportion of the increase in cancer incidence can be explained by improving life expectancy and population growth—a development that can at least partially be attributed to a reduced burden from other common diseases,” the study authors wrote.

The authors also pointed out that prevention efforts are less effective for hematologic malignancies than for other cancers.

Diabetics have higher risk of hematologic, other cancers

A review of data from more than 19 million people indicates that diabetes significantly raises a person’s risk of developing cancer.

When researchers compared patients with diabetes and without, both male and female diabetics had an increased risk of leukemias and lymphomas as well as certain solid tumors.

Researchers also found that diabetes conferred a higher cancer risk for women than men, both for all cancers combined and for some specific cancers, including leukemia.

“The link between diabetes and the risk of developing cancer is now firmly established,” said Toshiaki Ohkuma, PhD, of The George Institute for Global Health at the University of New South Wales in Australia.

“We have also demonstrated, for the first time, that women with diabetes are more likely to develop any form of cancer and have a significantly higher chance of developing kidney, oral, and stomach cancers and leukemia.”

Dr Ohkuma and his colleagues reported these findings in Diabetologia.

The researchers conducted a systematic search in PubMed MEDLINE to identify reports on the links between diabetes and cancer. Additional reports were identified from the reference lists of the relevant studies.

Only those cohort studies providing relative risks (RRs) for the association between diabetes and cancer for both women and men were included. In total, 107 relevant articles were identified, along with 36 cohorts of individual participant data.

RRs for cancer were obtained for patients with diabetes (types 1 and 2 combined) versus those without diabetes, for both men and women. The women-to-men ratios of these relative risk ratios (RRRs) were then calculated to determine the excess risk in women if present.

Data on all-site cancer was available from 47 studies, involving 121 cohorts and 19,239,302 individuals.

Diabetics vs non-diabetics

Women with diabetes had a 27% higher risk of all-site cancer compared to women without diabetes (RR=1.27; 95% CI 1.21, 1.32; P<0.001).

For men, the risk of all-site cancer was 19% higher among those with diabetes than those without (RR=1.19; 95% CI 1.13, 1.25; P<0.001).

There were several hematologic malignancies for which diabetics had an increased risk, as shown in the following table.

| Cancer type | RR for women (99% CI) | RR for men (99% CI) |

| Lymphatic and hematopoietic tissue | 1.24 (1.05, 1.46)* | 1.21 (0.98, 1.48) |

| Leukemia | 1.53 (1.00, 2.33) | 1.22 (0.80, 1.85) |

| Myeloid leukemia | 0.83 (0.39, 1.76) | 1.12 (0.77, 1.62) |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 1.33 (1.12, 1.57)* | 1.14 (0.56, 2.33) |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 1.67 (1.27, 2.20)* | 1.62 (1.32, 1.98)* |

| Lymphoid leukemia | 1.74 (0.31, 9.79) | 1.20 (0.86, 1.68) |

| Lymphoma | 2.31 (0.57, 9.30) | 1.80 (0.68, 4.75) |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 1.16 (1.02, 1.32)* | 1.20 (1.08, 1.34)* |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 1.20 (0.61, 2.38) | 1.36 (1.05, 1.77)* |

| Multiple myeloma | 1.19 (0.97, 1.47) | 1.12 (0.90, 1.41) |

| *denotes statistical significance with a P value < 0.01 | ||

Sex comparison

Calculation of the women-to-men ratio revealed that women with diabetes had a 6% greater excess risk of all-site cancer compared to men with diabetes (RRR=1.06; 95% CI 1.03, 1.09; P<0.001).

The women-to-men ratios also showed significantly higher risks for female diabetics for:

- Kidney cancer—RRR=1.11 (99% CI 1.04, 1.18; P<0.001)

- Oral cancer—RRR=1.13 (99% CI 1.00, 1.28; P=0.009)

- Stomach cancer—RRR=1.14 (99% CI 1.07, 1.22; P<0.001)

- Leukemia—RRR=1.15 (99% CI 1.02, 1.28; P=0.002).

However, women had a significantly lower risk of liver cancer (RRR=0.88; 99% CI 0.79, 0.99; P=0.005).

There are several possible reasons for the excess cancer risk observed in women, according to study author Sanne Peters, PhD, of The George Institute for Global Health at the University of Oxford in the UK.

For example, on average, women are in the pre-diabetic state of impaired glucose tolerance 2 years longer than men.

“Historically, we know that women are often under-treated when they first present with symptoms of diabetes, are less likely to receive intensive care, and are not taking the same levels of medications as men,” Dr Peters said. “All of these could go some way into explaining why women are at greater risk of developing cancer, but, without more research, we can’t be certain.”

A review of data from more than 19 million people indicates that diabetes significantly raises a person’s risk of developing cancer.

When researchers compared patients with diabetes and without, both male and female diabetics had an increased risk of leukemias and lymphomas as well as certain solid tumors.

Researchers also found that diabetes conferred a higher cancer risk for women than men, both for all cancers combined and for some specific cancers, including leukemia.

“The link between diabetes and the risk of developing cancer is now firmly established,” said Toshiaki Ohkuma, PhD, of The George Institute for Global Health at the University of New South Wales in Australia.

“We have also demonstrated, for the first time, that women with diabetes are more likely to develop any form of cancer and have a significantly higher chance of developing kidney, oral, and stomach cancers and leukemia.”

Dr Ohkuma and his colleagues reported these findings in Diabetologia.

The researchers conducted a systematic search in PubMed MEDLINE to identify reports on the links between diabetes and cancer. Additional reports were identified from the reference lists of the relevant studies.

Only those cohort studies providing relative risks (RRs) for the association between diabetes and cancer for both women and men were included. In total, 107 relevant articles were identified, along with 36 cohorts of individual participant data.

RRs for cancer were obtained for patients with diabetes (types 1 and 2 combined) versus those without diabetes, for both men and women. The women-to-men ratios of these relative risk ratios (RRRs) were then calculated to determine the excess risk in women if present.

Data on all-site cancer was available from 47 studies, involving 121 cohorts and 19,239,302 individuals.

Diabetics vs non-diabetics

Women with diabetes had a 27% higher risk of all-site cancer compared to women without diabetes (RR=1.27; 95% CI 1.21, 1.32; P<0.001).

For men, the risk of all-site cancer was 19% higher among those with diabetes than those without (RR=1.19; 95% CI 1.13, 1.25; P<0.001).

There were several hematologic malignancies for which diabetics had an increased risk, as shown in the following table.

| Cancer type | RR for women (99% CI) | RR for men (99% CI) |

| Lymphatic and hematopoietic tissue | 1.24 (1.05, 1.46)* | 1.21 (0.98, 1.48) |

| Leukemia | 1.53 (1.00, 2.33) | 1.22 (0.80, 1.85) |

| Myeloid leukemia | 0.83 (0.39, 1.76) | 1.12 (0.77, 1.62) |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 1.33 (1.12, 1.57)* | 1.14 (0.56, 2.33) |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia | 1.67 (1.27, 2.20)* | 1.62 (1.32, 1.98)* |

| Lymphoid leukemia | 1.74 (0.31, 9.79) | 1.20 (0.86, 1.68) |

| Lymphoma | 2.31 (0.57, 9.30) | 1.80 (0.68, 4.75) |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 1.16 (1.02, 1.32)* | 1.20 (1.08, 1.34)* |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 1.20 (0.61, 2.38) | 1.36 (1.05, 1.77)* |

| Multiple myeloma | 1.19 (0.97, 1.47) | 1.12 (0.90, 1.41) |

| *denotes statistical significance with a P value < 0.01 | ||

Sex comparison

Calculation of the women-to-men ratio revealed that women with diabetes had a 6% greater excess risk of all-site cancer compared to men with diabetes (RRR=1.06; 95% CI 1.03, 1.09; P<0.001).

The women-to-men ratios also showed significantly higher risks for female diabetics for: