User login

AML leads percent gains in 5-year survival among leukemias

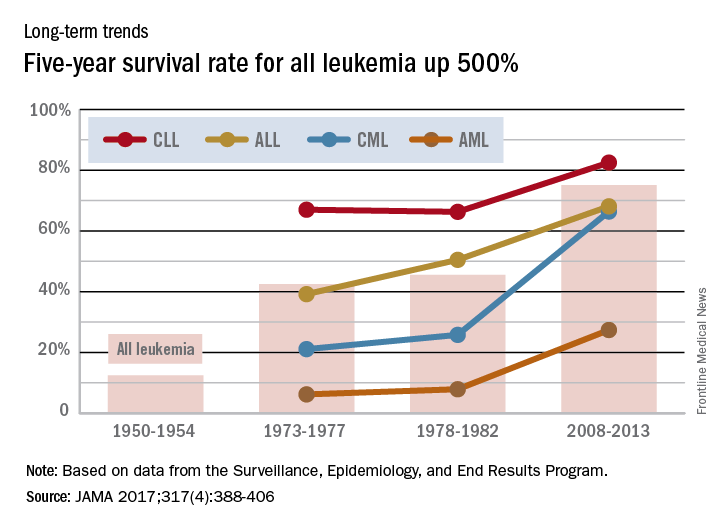

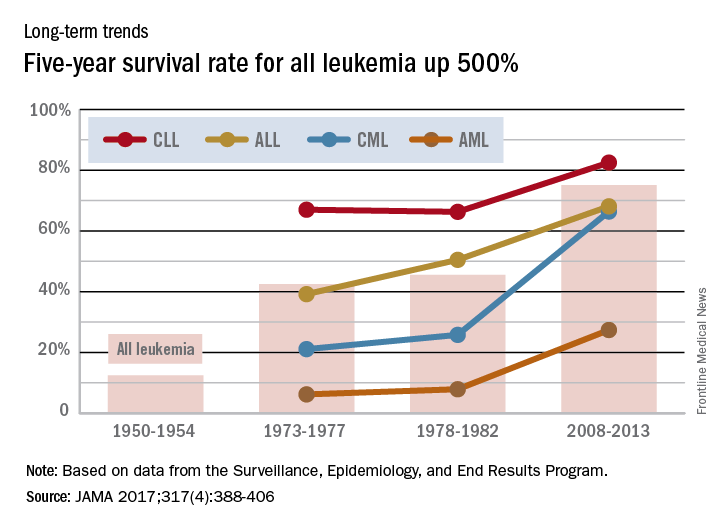

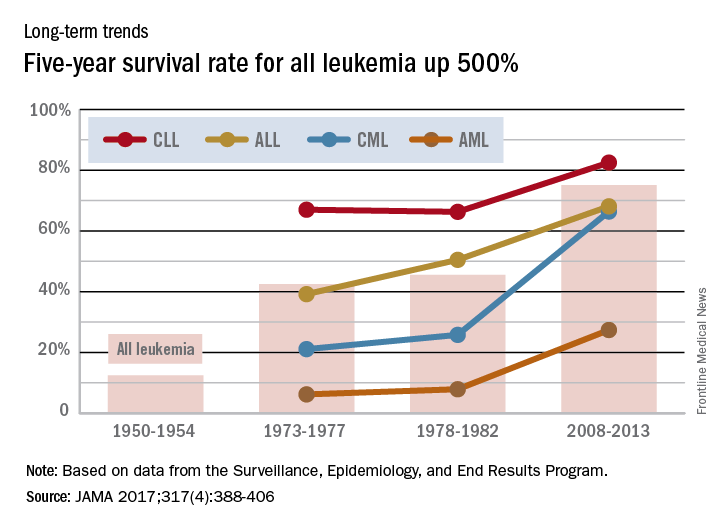

Over the 60-year span from the early 1950s to 2013, the 5-year survival rate for all leukemias increased by 500%, according to data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program.

For 2008-2013, the 5-year relative survival rate for all leukemias was 60.1%, compared with 10% during 1950-1954, said Ali H. Mokdad, PhD, and his associates at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, Seattle (JAMA 2017;317[4]:388-406).

Over the 60-year span from the early 1950s to 2013, the 5-year survival rate for all leukemias increased by 500%, according to data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program.

For 2008-2013, the 5-year relative survival rate for all leukemias was 60.1%, compared with 10% during 1950-1954, said Ali H. Mokdad, PhD, and his associates at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, Seattle (JAMA 2017;317[4]:388-406).

Over the 60-year span from the early 1950s to 2013, the 5-year survival rate for all leukemias increased by 500%, according to data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program.

For 2008-2013, the 5-year relative survival rate for all leukemias was 60.1%, compared with 10% during 1950-1954, said Ali H. Mokdad, PhD, and his associates at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, Seattle (JAMA 2017;317[4]:388-406).

Study quantifies 5-year survival rates for blood cancers

chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

A new study shows that 5-year survival rates for US patients with hematologic malignancies have increased greatly since the 1950s, but there is still room for improvement, particularly for patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Researchers found the absolute difference in improvement for 5-year survival from 1950-1954 to 2008-2013 ranged from 38.2% for non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) to 56.6% for Hodgkin lymphoma.

And although the 5-year survival rate for Hodgkin lymphoma patients reached 86.6% for 2008-2013, the 5-year survival rate for patients with AML only reached 27.4%.

This study also revealed large disparities in overall cancer mortality rates between different counties across the country.

Ali H. Mokdad, PhD, of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation in Seattle, Washington, and his colleagues reported these findings in JAMA.

Overall cancer deaths

The researchers found there were 19,511,910 cancer deaths recorded in the US between 1980 and 2014. Cancer mortality decreased by 20.1% between 1980 and 2014, from 240.2 deaths per 100,000 people to 192.0 deaths per 100,000 people.

In 1980, cancer mortality ranged from 130.6 per 100,000 in Summit County, Colorado, to 386.9 per 100,000 in North Slope Borough, Alaska.

In 2014, cancer mortality ranged from 70.7 per 100,000 in Summit County, Colorado, to 503.1 per 100,000 in Union County, Florida.

“Such significant disparities among US counties is unacceptable,” Dr Mokdad said. “Every person should have access to early screenings for cancer, as well as adequate treatment.”

Mortality rates for hematologic malignancies

In 2014, the mortality rates, per 100,000 people, for hematologic malignancies were:

- 0.4 for Hodgkin lymphoma (rank out of all cancers, 27)

- 8.3 for NHL (rank, 7)

- 3.9 for multiple myeloma (rank, 16)

- 9.0 for all leukemias (rank, 6)

- 0.7 for acute lymphoid leukemia (ALL)

- 2.6 for chronic lymphoid leukemia (CLL)

- 5.1 for AML

- 0.6 for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

The leukemia subtypes were not assigned a rank.

5-year survival rates for hematologic malignancies

Hodgkin lymphoma

- 30% for 1950-54

- 68.6% for 1973-77

- 72.1% for 1978-82

- 86.6% for 2008-2013

- Absolute difference (between the first and latest year of data), 56.6%.

NHL

- 33% for 1950-54

- 45.3% for 1973-77

- 48.7% for 1978-82

- 71.2% for 2008-2013

- Absolute difference, 38.2%.

Multiple myeloma

- 6% for 1950-54

- 23.4% for 1973-77

- 26.6% for 1978-82

- 49.8% for 2008-2013

- Absolute difference, 43.8%.

Leukemia

- 10% for 1950-54

- 34% for 1973-77

- 36.3% for 1978-82

- 60.1% for 2008-2013

- Absolute difference, 50.1%.

ALL

- 39.2% for 1973-77

- 50.5% for 1978-82

- 68.1% for 2008-2013

- Absolute difference, 28.9%.

CLL

- 67% for 1973-77

- 66.3% for 1978-82

- 82.5% for 2008-2013

- Absolute difference, 15.5%.

AML

- 6.2% for 1973-77

- 7.9% for 1978-82

- 27.4% for 2008-2013

- Absolute difference, 21.2%.

CML

- 21.1% for 1973-77

- 25.8% for 1978-82

- 66.4% for 2008-2013

- Absolute difference, 45.3%.

For the leukemia subtypes, there was no data for 1950 to 1954. ![]()

chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

A new study shows that 5-year survival rates for US patients with hematologic malignancies have increased greatly since the 1950s, but there is still room for improvement, particularly for patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Researchers found the absolute difference in improvement for 5-year survival from 1950-1954 to 2008-2013 ranged from 38.2% for non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) to 56.6% for Hodgkin lymphoma.

And although the 5-year survival rate for Hodgkin lymphoma patients reached 86.6% for 2008-2013, the 5-year survival rate for patients with AML only reached 27.4%.

This study also revealed large disparities in overall cancer mortality rates between different counties across the country.

Ali H. Mokdad, PhD, of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation in Seattle, Washington, and his colleagues reported these findings in JAMA.

Overall cancer deaths

The researchers found there were 19,511,910 cancer deaths recorded in the US between 1980 and 2014. Cancer mortality decreased by 20.1% between 1980 and 2014, from 240.2 deaths per 100,000 people to 192.0 deaths per 100,000 people.

In 1980, cancer mortality ranged from 130.6 per 100,000 in Summit County, Colorado, to 386.9 per 100,000 in North Slope Borough, Alaska.

In 2014, cancer mortality ranged from 70.7 per 100,000 in Summit County, Colorado, to 503.1 per 100,000 in Union County, Florida.

“Such significant disparities among US counties is unacceptable,” Dr Mokdad said. “Every person should have access to early screenings for cancer, as well as adequate treatment.”

Mortality rates for hematologic malignancies

In 2014, the mortality rates, per 100,000 people, for hematologic malignancies were:

- 0.4 for Hodgkin lymphoma (rank out of all cancers, 27)

- 8.3 for NHL (rank, 7)

- 3.9 for multiple myeloma (rank, 16)

- 9.0 for all leukemias (rank, 6)

- 0.7 for acute lymphoid leukemia (ALL)

- 2.6 for chronic lymphoid leukemia (CLL)

- 5.1 for AML

- 0.6 for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

The leukemia subtypes were not assigned a rank.

5-year survival rates for hematologic malignancies

Hodgkin lymphoma

- 30% for 1950-54

- 68.6% for 1973-77

- 72.1% for 1978-82

- 86.6% for 2008-2013

- Absolute difference (between the first and latest year of data), 56.6%.

NHL

- 33% for 1950-54

- 45.3% for 1973-77

- 48.7% for 1978-82

- 71.2% for 2008-2013

- Absolute difference, 38.2%.

Multiple myeloma

- 6% for 1950-54

- 23.4% for 1973-77

- 26.6% for 1978-82

- 49.8% for 2008-2013

- Absolute difference, 43.8%.

Leukemia

- 10% for 1950-54

- 34% for 1973-77

- 36.3% for 1978-82

- 60.1% for 2008-2013

- Absolute difference, 50.1%.

ALL

- 39.2% for 1973-77

- 50.5% for 1978-82

- 68.1% for 2008-2013

- Absolute difference, 28.9%.

CLL

- 67% for 1973-77

- 66.3% for 1978-82

- 82.5% for 2008-2013

- Absolute difference, 15.5%.

AML

- 6.2% for 1973-77

- 7.9% for 1978-82

- 27.4% for 2008-2013

- Absolute difference, 21.2%.

CML

- 21.1% for 1973-77

- 25.8% for 1978-82

- 66.4% for 2008-2013

- Absolute difference, 45.3%.

For the leukemia subtypes, there was no data for 1950 to 1954. ![]()

chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

A new study shows that 5-year survival rates for US patients with hematologic malignancies have increased greatly since the 1950s, but there is still room for improvement, particularly for patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Researchers found the absolute difference in improvement for 5-year survival from 1950-1954 to 2008-2013 ranged from 38.2% for non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) to 56.6% for Hodgkin lymphoma.

And although the 5-year survival rate for Hodgkin lymphoma patients reached 86.6% for 2008-2013, the 5-year survival rate for patients with AML only reached 27.4%.

This study also revealed large disparities in overall cancer mortality rates between different counties across the country.

Ali H. Mokdad, PhD, of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation in Seattle, Washington, and his colleagues reported these findings in JAMA.

Overall cancer deaths

The researchers found there were 19,511,910 cancer deaths recorded in the US between 1980 and 2014. Cancer mortality decreased by 20.1% between 1980 and 2014, from 240.2 deaths per 100,000 people to 192.0 deaths per 100,000 people.

In 1980, cancer mortality ranged from 130.6 per 100,000 in Summit County, Colorado, to 386.9 per 100,000 in North Slope Borough, Alaska.

In 2014, cancer mortality ranged from 70.7 per 100,000 in Summit County, Colorado, to 503.1 per 100,000 in Union County, Florida.

“Such significant disparities among US counties is unacceptable,” Dr Mokdad said. “Every person should have access to early screenings for cancer, as well as adequate treatment.”

Mortality rates for hematologic malignancies

In 2014, the mortality rates, per 100,000 people, for hematologic malignancies were:

- 0.4 for Hodgkin lymphoma (rank out of all cancers, 27)

- 8.3 for NHL (rank, 7)

- 3.9 for multiple myeloma (rank, 16)

- 9.0 for all leukemias (rank, 6)

- 0.7 for acute lymphoid leukemia (ALL)

- 2.6 for chronic lymphoid leukemia (CLL)

- 5.1 for AML

- 0.6 for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML).

The leukemia subtypes were not assigned a rank.

5-year survival rates for hematologic malignancies

Hodgkin lymphoma

- 30% for 1950-54

- 68.6% for 1973-77

- 72.1% for 1978-82

- 86.6% for 2008-2013

- Absolute difference (between the first and latest year of data), 56.6%.

NHL

- 33% for 1950-54

- 45.3% for 1973-77

- 48.7% for 1978-82

- 71.2% for 2008-2013

- Absolute difference, 38.2%.

Multiple myeloma

- 6% for 1950-54

- 23.4% for 1973-77

- 26.6% for 1978-82

- 49.8% for 2008-2013

- Absolute difference, 43.8%.

Leukemia

- 10% for 1950-54

- 34% for 1973-77

- 36.3% for 1978-82

- 60.1% for 2008-2013

- Absolute difference, 50.1%.

ALL

- 39.2% for 1973-77

- 50.5% for 1978-82

- 68.1% for 2008-2013

- Absolute difference, 28.9%.

CLL

- 67% for 1973-77

- 66.3% for 1978-82

- 82.5% for 2008-2013

- Absolute difference, 15.5%.

AML

- 6.2% for 1973-77

- 7.9% for 1978-82

- 27.4% for 2008-2013

- Absolute difference, 21.2%.

CML

- 21.1% for 1973-77

- 25.8% for 1978-82

- 66.4% for 2008-2013

- Absolute difference, 45.3%.

For the leukemia subtypes, there was no data for 1950 to 1954. ![]()

Drugs may be effective against hematologic, other cancers

Image courtesy of PNAS

A diabetes medication and an antihypertensive drug may prove effective in the treatment of hematologic malignancies and other cancers, according to preclinical research published in Science Advances.

Past research has shown that metformin, a drug used to treat type 2 diabetes, has anticancer properties.

However, the usual therapeutic dose is too low to effectively fight cancer, and higher doses of metformin could be too toxic.

With the current study, researchers found that the antihypertensive drug syrosingopine enhances the anticancer efficacy of metformin without harming normal blood cells.

The team screened over a thousand drugs to find one that could boost metformin’s efficacy against cancers.

They identified syrosingopine and tested it in combination with metformin—at concentrations substantially below the drugs’ therapeutic thresholds—on a range of cancer cell lines and in mouse models of liver cancer.

Thirty-five of the 43 cell lines tested were susceptible to both syrosingopine and metformin. This included leukemia, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma cell lines.

In addition, the mice given a short course of syrosingopine and metformin experienced a reduction in the number of visible liver tumors.

The researchers also tested syrosingopine and metformin in peripheral blasts from 12 patients with acute myeloid leukemia and a patient with blast crisis chronic myeloid leukemia. All 13 samples responded to the treatment.

On the other hand, syrosingopine and metformin did not affect peripheral blood cells from healthy subjects.

“[A]lmost all tumor cells were killed by this cocktail and at doses that are actually not toxic to normal cells,” said study author Don Benjamin, of the University of Basel in Switzerland.

“And the effect was exclusively confined to cancer cells, as the blood cells from healthy donors were insensitive to the treatment.”

The researchers believe metformin functions by lowering blood glucose levels for cancer cells, starving them of essential nutrients needed for their survival. However, it is not clear how syrosingopine works in conjunction with metformin.

The team emphasized the need for more research evaluating the drugs in combination.

“We have been able to show that the 2 known drugs lead to more profound effects on cancer cell proliferation than each drug alone,” Dr Benjamin said. “The data from this study support the development of combination approaches for the treatment of cancer patients.” ![]()

Image courtesy of PNAS

A diabetes medication and an antihypertensive drug may prove effective in the treatment of hematologic malignancies and other cancers, according to preclinical research published in Science Advances.

Past research has shown that metformin, a drug used to treat type 2 diabetes, has anticancer properties.

However, the usual therapeutic dose is too low to effectively fight cancer, and higher doses of metformin could be too toxic.

With the current study, researchers found that the antihypertensive drug syrosingopine enhances the anticancer efficacy of metformin without harming normal blood cells.

The team screened over a thousand drugs to find one that could boost metformin’s efficacy against cancers.

They identified syrosingopine and tested it in combination with metformin—at concentrations substantially below the drugs’ therapeutic thresholds—on a range of cancer cell lines and in mouse models of liver cancer.

Thirty-five of the 43 cell lines tested were susceptible to both syrosingopine and metformin. This included leukemia, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma cell lines.

In addition, the mice given a short course of syrosingopine and metformin experienced a reduction in the number of visible liver tumors.

The researchers also tested syrosingopine and metformin in peripheral blasts from 12 patients with acute myeloid leukemia and a patient with blast crisis chronic myeloid leukemia. All 13 samples responded to the treatment.

On the other hand, syrosingopine and metformin did not affect peripheral blood cells from healthy subjects.

“[A]lmost all tumor cells were killed by this cocktail and at doses that are actually not toxic to normal cells,” said study author Don Benjamin, of the University of Basel in Switzerland.

“And the effect was exclusively confined to cancer cells, as the blood cells from healthy donors were insensitive to the treatment.”

The researchers believe metformin functions by lowering blood glucose levels for cancer cells, starving them of essential nutrients needed for their survival. However, it is not clear how syrosingopine works in conjunction with metformin.

The team emphasized the need for more research evaluating the drugs in combination.

“We have been able to show that the 2 known drugs lead to more profound effects on cancer cell proliferation than each drug alone,” Dr Benjamin said. “The data from this study support the development of combination approaches for the treatment of cancer patients.” ![]()

Image courtesy of PNAS

A diabetes medication and an antihypertensive drug may prove effective in the treatment of hematologic malignancies and other cancers, according to preclinical research published in Science Advances.

Past research has shown that metformin, a drug used to treat type 2 diabetes, has anticancer properties.

However, the usual therapeutic dose is too low to effectively fight cancer, and higher doses of metformin could be too toxic.

With the current study, researchers found that the antihypertensive drug syrosingopine enhances the anticancer efficacy of metformin without harming normal blood cells.

The team screened over a thousand drugs to find one that could boost metformin’s efficacy against cancers.

They identified syrosingopine and tested it in combination with metformin—at concentrations substantially below the drugs’ therapeutic thresholds—on a range of cancer cell lines and in mouse models of liver cancer.

Thirty-five of the 43 cell lines tested were susceptible to both syrosingopine and metformin. This included leukemia, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma cell lines.

In addition, the mice given a short course of syrosingopine and metformin experienced a reduction in the number of visible liver tumors.

The researchers also tested syrosingopine and metformin in peripheral blasts from 12 patients with acute myeloid leukemia and a patient with blast crisis chronic myeloid leukemia. All 13 samples responded to the treatment.

On the other hand, syrosingopine and metformin did not affect peripheral blood cells from healthy subjects.

“[A]lmost all tumor cells were killed by this cocktail and at doses that are actually not toxic to normal cells,” said study author Don Benjamin, of the University of Basel in Switzerland.

“And the effect was exclusively confined to cancer cells, as the blood cells from healthy donors were insensitive to the treatment.”

The researchers believe metformin functions by lowering blood glucose levels for cancer cells, starving them of essential nutrients needed for their survival. However, it is not clear how syrosingopine works in conjunction with metformin.

The team emphasized the need for more research evaluating the drugs in combination.

“We have been able to show that the 2 known drugs lead to more profound effects on cancer cell proliferation than each drug alone,” Dr Benjamin said. “The data from this study support the development of combination approaches for the treatment of cancer patients.” ![]()

Study reveals CML patients likely to benefit from HSCT long-term

Photo by Chad McNeeley

SAN DIEGO—Researchers believe they have identified patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) who are likely to derive long-term benefit from allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (allo-HSCT).

The researchers found that CML patients have a low risk of long-term morbidity if they undergo HSCT before the age of 45, are conditioned with busulfan and cyclophosphamide (Bu/Cy), and receive a graft from a matched, related donor (MRD).

Jessica Wu, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, presented these findings at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 823*).

Wu noted that allogeneic HSCT is potentially curative for CML, but this method of treatment has been on the decline since the introduction of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). And today, few CML patients undergo allo-HSCT.

She said that although TKIs can induce remission in CML patients, the drugs also fail to eradicate leukemia, can produce side effects that impact patients’ quality of life, and come with a significant financial burden (estimated at $92,000 to $138,000 per patient per year).

With this in mind, Wu and her colleagues set out to determine if certain CML patients might benefit from allo-HSCT long-term. The team also wanted to quantify overall and cause-specific late mortality after allo-HSCT and the long-term burden of severe/life-threatening chronic health conditions after allo-HSCT.

Patient population

The researchers studied 637 CML patients treated with allo-HSCT between 1981 and 2010 at City of Hope in Duarte, California, or the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis/Saint Paul. The patients had to have survived at least 2 years post-transplant.

About 60% of patients were male, and 67% were non-Hispanic white. Their median age at HSCT was 36.4 years, and 65% received an MRD graft. Nineteen percent of patients were transplanted in 1980-1989, 52% were transplanted in 1990-1999, and 29% were transplanted in 2000-2010.

Fifty-eight percent of patients received Cy/total body irradiation (TBI), 18% received Bu/Cy, and 3% received reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC).

Sixty-one percent of patients had chronic graft-vs-host disease (cGVHD), and 32% had high-risk disease at the time of HSCT.

Survival

The patients were followed for a median of 16.7 years. Thirty percent (n=192) died after surviving at least 2 years post-HSCT.

The median time to death was 8.3 years (range, 2-29.5), and the median age at death was 49.2 (range, 7.8-69.8). At 20 years from HSCT, the overall survival was 68.6%.

HSCT recipients had a 4.4-fold increased risk of death compared with the age-, sex-, and race-matched general population.

“Non-relapse mortality was the major contributor to late mortality, with infection, second malignancies, and cGVHD being the most common causes of death,” Wu said.

Non-relapse mortality was 20%, and relapse-related mortality was 4%. Eight percent of patients died of infection, 6.3% died of cGVHD, and 3.7% died of second malignancies.

Health outcomes

Patients who were still alive at the time of the study were asked to complete the BMTSS-2 health questionnaire, which was used to examine the risk of grade 3/4 chronic health conditions.

A total of 288 patients completed the questionnaire, as did a sibling comparison group of 404 individuals.

Among the patients, the median age at allo-HSCT was 37.5 (range, 3.6-71.4), and the median duration of follow-up was 13.9 years (range, 2-34.6).

Sixty-two percent of patients received an MRD graft, and 38% had a matched, unrelated donor. Eighty-three percent of patients had TBI-based conditioning, 16% received Bu/Cy, and 2.7% received RIC.

The prevalence of grade 3/4 chronic health conditions was significantly higher among patients than among siblings—38% and 24%, respectively (P<0.0001).

The odds ratio (OR)—adjusted for age, sex, race, and socioeconomic status—was 2.7 (P<0.0001).

The cumulative incidence of any grade 3/4 condition at 20 years after HSCT was 47.2% among patients. Common conditions were diabetes (14.9%), second malignancies (12.6%), and coronary artery disease (10%).

The researchers found the risk of grade 3/4 morbidity was significantly higher for the following patient groups:

- Those age 45 and older (hazard ratio [HR]=3.3, P<0.0001)

- Patients with a matched, unrelated donor (HR=3.0, P<0.0001)

- Those who received peripheral blood or cord blood grafts as opposed to bone marrow (HR=2.7, P=0.006).

(This analysis was adjusted for race/ethnicity, sex, education, household income, insurance, cGVHD, and conditioning regimen).

Lower risk

To identify subpopulations with a reduced risk of long-term morbidity, the researchers calculated the risk in various CML patient groups compared to siblings.

The overall OR for CML patients compared with siblings was 2.7 (P<0.0001).

The OR for patients in first chronic phase who underwent HSCT before the age of 45 and had an MRD was 1.5 (P=0.1).

The OR for CML patients in first chronic phase who underwent HSCT before the age of 45, had an MRD, and received Bu/Cy conditioning was 0.8 (P=0.7).

“[W]e found that patients who received a matched, related donor transplant under the age of 45, with busulfan/cyclophosphamide, carried the same burden of morbidity as the sibling cohort,” Wu said. “These findings could help inform decisions regarding therapeutic options for the management of CML.”

Wu noted that the limited sample size in this study prevented the researchers from examining outcomes with RIC. And a lack of data at analysis prevented them from examining pre-HSCT and post-HSCT management of CML, the interval between diagnosis and HSCT, and the life-long economic burden of allo-HSCT.

However, she said data collection is ongoing, and the researchers hope to address some of these limitations.![]()

*Information presented at the meeting differs from the abstract.

Photo by Chad McNeeley

SAN DIEGO—Researchers believe they have identified patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) who are likely to derive long-term benefit from allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (allo-HSCT).

The researchers found that CML patients have a low risk of long-term morbidity if they undergo HSCT before the age of 45, are conditioned with busulfan and cyclophosphamide (Bu/Cy), and receive a graft from a matched, related donor (MRD).

Jessica Wu, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, presented these findings at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 823*).

Wu noted that allogeneic HSCT is potentially curative for CML, but this method of treatment has been on the decline since the introduction of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). And today, few CML patients undergo allo-HSCT.

She said that although TKIs can induce remission in CML patients, the drugs also fail to eradicate leukemia, can produce side effects that impact patients’ quality of life, and come with a significant financial burden (estimated at $92,000 to $138,000 per patient per year).

With this in mind, Wu and her colleagues set out to determine if certain CML patients might benefit from allo-HSCT long-term. The team also wanted to quantify overall and cause-specific late mortality after allo-HSCT and the long-term burden of severe/life-threatening chronic health conditions after allo-HSCT.

Patient population

The researchers studied 637 CML patients treated with allo-HSCT between 1981 and 2010 at City of Hope in Duarte, California, or the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis/Saint Paul. The patients had to have survived at least 2 years post-transplant.

About 60% of patients were male, and 67% were non-Hispanic white. Their median age at HSCT was 36.4 years, and 65% received an MRD graft. Nineteen percent of patients were transplanted in 1980-1989, 52% were transplanted in 1990-1999, and 29% were transplanted in 2000-2010.

Fifty-eight percent of patients received Cy/total body irradiation (TBI), 18% received Bu/Cy, and 3% received reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC).

Sixty-one percent of patients had chronic graft-vs-host disease (cGVHD), and 32% had high-risk disease at the time of HSCT.

Survival

The patients were followed for a median of 16.7 years. Thirty percent (n=192) died after surviving at least 2 years post-HSCT.

The median time to death was 8.3 years (range, 2-29.5), and the median age at death was 49.2 (range, 7.8-69.8). At 20 years from HSCT, the overall survival was 68.6%.

HSCT recipients had a 4.4-fold increased risk of death compared with the age-, sex-, and race-matched general population.

“Non-relapse mortality was the major contributor to late mortality, with infection, second malignancies, and cGVHD being the most common causes of death,” Wu said.

Non-relapse mortality was 20%, and relapse-related mortality was 4%. Eight percent of patients died of infection, 6.3% died of cGVHD, and 3.7% died of second malignancies.

Health outcomes

Patients who were still alive at the time of the study were asked to complete the BMTSS-2 health questionnaire, which was used to examine the risk of grade 3/4 chronic health conditions.

A total of 288 patients completed the questionnaire, as did a sibling comparison group of 404 individuals.

Among the patients, the median age at allo-HSCT was 37.5 (range, 3.6-71.4), and the median duration of follow-up was 13.9 years (range, 2-34.6).

Sixty-two percent of patients received an MRD graft, and 38% had a matched, unrelated donor. Eighty-three percent of patients had TBI-based conditioning, 16% received Bu/Cy, and 2.7% received RIC.

The prevalence of grade 3/4 chronic health conditions was significantly higher among patients than among siblings—38% and 24%, respectively (P<0.0001).

The odds ratio (OR)—adjusted for age, sex, race, and socioeconomic status—was 2.7 (P<0.0001).

The cumulative incidence of any grade 3/4 condition at 20 years after HSCT was 47.2% among patients. Common conditions were diabetes (14.9%), second malignancies (12.6%), and coronary artery disease (10%).

The researchers found the risk of grade 3/4 morbidity was significantly higher for the following patient groups:

- Those age 45 and older (hazard ratio [HR]=3.3, P<0.0001)

- Patients with a matched, unrelated donor (HR=3.0, P<0.0001)

- Those who received peripheral blood or cord blood grafts as opposed to bone marrow (HR=2.7, P=0.006).

(This analysis was adjusted for race/ethnicity, sex, education, household income, insurance, cGVHD, and conditioning regimen).

Lower risk

To identify subpopulations with a reduced risk of long-term morbidity, the researchers calculated the risk in various CML patient groups compared to siblings.

The overall OR for CML patients compared with siblings was 2.7 (P<0.0001).

The OR for patients in first chronic phase who underwent HSCT before the age of 45 and had an MRD was 1.5 (P=0.1).

The OR for CML patients in first chronic phase who underwent HSCT before the age of 45, had an MRD, and received Bu/Cy conditioning was 0.8 (P=0.7).

“[W]e found that patients who received a matched, related donor transplant under the age of 45, with busulfan/cyclophosphamide, carried the same burden of morbidity as the sibling cohort,” Wu said. “These findings could help inform decisions regarding therapeutic options for the management of CML.”

Wu noted that the limited sample size in this study prevented the researchers from examining outcomes with RIC. And a lack of data at analysis prevented them from examining pre-HSCT and post-HSCT management of CML, the interval between diagnosis and HSCT, and the life-long economic burden of allo-HSCT.

However, she said data collection is ongoing, and the researchers hope to address some of these limitations.![]()

*Information presented at the meeting differs from the abstract.

Photo by Chad McNeeley

SAN DIEGO—Researchers believe they have identified patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) who are likely to derive long-term benefit from allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (allo-HSCT).

The researchers found that CML patients have a low risk of long-term morbidity if they undergo HSCT before the age of 45, are conditioned with busulfan and cyclophosphamide (Bu/Cy), and receive a graft from a matched, related donor (MRD).

Jessica Wu, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, presented these findings at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 823*).

Wu noted that allogeneic HSCT is potentially curative for CML, but this method of treatment has been on the decline since the introduction of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). And today, few CML patients undergo allo-HSCT.

She said that although TKIs can induce remission in CML patients, the drugs also fail to eradicate leukemia, can produce side effects that impact patients’ quality of life, and come with a significant financial burden (estimated at $92,000 to $138,000 per patient per year).

With this in mind, Wu and her colleagues set out to determine if certain CML patients might benefit from allo-HSCT long-term. The team also wanted to quantify overall and cause-specific late mortality after allo-HSCT and the long-term burden of severe/life-threatening chronic health conditions after allo-HSCT.

Patient population

The researchers studied 637 CML patients treated with allo-HSCT between 1981 and 2010 at City of Hope in Duarte, California, or the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis/Saint Paul. The patients had to have survived at least 2 years post-transplant.

About 60% of patients were male, and 67% were non-Hispanic white. Their median age at HSCT was 36.4 years, and 65% received an MRD graft. Nineteen percent of patients were transplanted in 1980-1989, 52% were transplanted in 1990-1999, and 29% were transplanted in 2000-2010.

Fifty-eight percent of patients received Cy/total body irradiation (TBI), 18% received Bu/Cy, and 3% received reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC).

Sixty-one percent of patients had chronic graft-vs-host disease (cGVHD), and 32% had high-risk disease at the time of HSCT.

Survival

The patients were followed for a median of 16.7 years. Thirty percent (n=192) died after surviving at least 2 years post-HSCT.

The median time to death was 8.3 years (range, 2-29.5), and the median age at death was 49.2 (range, 7.8-69.8). At 20 years from HSCT, the overall survival was 68.6%.

HSCT recipients had a 4.4-fold increased risk of death compared with the age-, sex-, and race-matched general population.

“Non-relapse mortality was the major contributor to late mortality, with infection, second malignancies, and cGVHD being the most common causes of death,” Wu said.

Non-relapse mortality was 20%, and relapse-related mortality was 4%. Eight percent of patients died of infection, 6.3% died of cGVHD, and 3.7% died of second malignancies.

Health outcomes

Patients who were still alive at the time of the study were asked to complete the BMTSS-2 health questionnaire, which was used to examine the risk of grade 3/4 chronic health conditions.

A total of 288 patients completed the questionnaire, as did a sibling comparison group of 404 individuals.

Among the patients, the median age at allo-HSCT was 37.5 (range, 3.6-71.4), and the median duration of follow-up was 13.9 years (range, 2-34.6).

Sixty-two percent of patients received an MRD graft, and 38% had a matched, unrelated donor. Eighty-three percent of patients had TBI-based conditioning, 16% received Bu/Cy, and 2.7% received RIC.

The prevalence of grade 3/4 chronic health conditions was significantly higher among patients than among siblings—38% and 24%, respectively (P<0.0001).

The odds ratio (OR)—adjusted for age, sex, race, and socioeconomic status—was 2.7 (P<0.0001).

The cumulative incidence of any grade 3/4 condition at 20 years after HSCT was 47.2% among patients. Common conditions were diabetes (14.9%), second malignancies (12.6%), and coronary artery disease (10%).

The researchers found the risk of grade 3/4 morbidity was significantly higher for the following patient groups:

- Those age 45 and older (hazard ratio [HR]=3.3, P<0.0001)

- Patients with a matched, unrelated donor (HR=3.0, P<0.0001)

- Those who received peripheral blood or cord blood grafts as opposed to bone marrow (HR=2.7, P=0.006).

(This analysis was adjusted for race/ethnicity, sex, education, household income, insurance, cGVHD, and conditioning regimen).

Lower risk

To identify subpopulations with a reduced risk of long-term morbidity, the researchers calculated the risk in various CML patient groups compared to siblings.

The overall OR for CML patients compared with siblings was 2.7 (P<0.0001).

The OR for patients in first chronic phase who underwent HSCT before the age of 45 and had an MRD was 1.5 (P=0.1).

The OR for CML patients in first chronic phase who underwent HSCT before the age of 45, had an MRD, and received Bu/Cy conditioning was 0.8 (P=0.7).

“[W]e found that patients who received a matched, related donor transplant under the age of 45, with busulfan/cyclophosphamide, carried the same burden of morbidity as the sibling cohort,” Wu said. “These findings could help inform decisions regarding therapeutic options for the management of CML.”

Wu noted that the limited sample size in this study prevented the researchers from examining outcomes with RIC. And a lack of data at analysis prevented them from examining pre-HSCT and post-HSCT management of CML, the interval between diagnosis and HSCT, and the life-long economic burden of allo-HSCT.

However, she said data collection is ongoing, and the researchers hope to address some of these limitations.![]()

*Information presented at the meeting differs from the abstract.

Group estimates global cancer cases, deaths in 2015

receiving chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Researchers have estimated the global incidence of 32 cancer types and deaths related to these malignancies in 2015.

The group’s data, published in JAMA Oncology, suggest there were 17.5 million cancer cases and 8.7 million cancer deaths last year.

There were 78,000 cases of Hodgkin lymphoma and 24,000 deaths from the disease, as well as 666,000 cases of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and 231,000 NHL deaths.

There were 154,000 cases of multiple myeloma and 101,000 deaths from the disease.

And there were 606,000 cases of leukemia, with 353,000 leukemia deaths. This included 161,000 cases of acute lymphoid leukemia (110,000 deaths), 191,000 cases of chronic lymphoid leukemia (61,000 deaths), 190,000 cases of acute myeloid leukemia (147,000 deaths), and 64,000 cases of chronic myeloid leukemia (35,000 deaths).

The data also show that, between 2005 and 2015, cancer cases increased by 33%, mostly due to population aging and growth, plus changes in age-specific cancer rates.

Globally, the odds of developing cancer during a lifetime were 1 in 3 for men and 1 in 4 for women in 2015.

Prostate cancer was the most common cancer in men (1.6 million cases), although tracheal, bronchus, and lung cancer was the leading cause of cancer deaths for men.

Breast cancer was the most common cancer for women (2.4 million cases) and the leading cause of cancer deaths in women.

The most common childhood cancers were leukemia, “other neoplasms,” NHL, and brain and nervous system cancers. ![]()

receiving chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Researchers have estimated the global incidence of 32 cancer types and deaths related to these malignancies in 2015.

The group’s data, published in JAMA Oncology, suggest there were 17.5 million cancer cases and 8.7 million cancer deaths last year.

There were 78,000 cases of Hodgkin lymphoma and 24,000 deaths from the disease, as well as 666,000 cases of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and 231,000 NHL deaths.

There were 154,000 cases of multiple myeloma and 101,000 deaths from the disease.

And there were 606,000 cases of leukemia, with 353,000 leukemia deaths. This included 161,000 cases of acute lymphoid leukemia (110,000 deaths), 191,000 cases of chronic lymphoid leukemia (61,000 deaths), 190,000 cases of acute myeloid leukemia (147,000 deaths), and 64,000 cases of chronic myeloid leukemia (35,000 deaths).

The data also show that, between 2005 and 2015, cancer cases increased by 33%, mostly due to population aging and growth, plus changes in age-specific cancer rates.

Globally, the odds of developing cancer during a lifetime were 1 in 3 for men and 1 in 4 for women in 2015.

Prostate cancer was the most common cancer in men (1.6 million cases), although tracheal, bronchus, and lung cancer was the leading cause of cancer deaths for men.

Breast cancer was the most common cancer for women (2.4 million cases) and the leading cause of cancer deaths in women.

The most common childhood cancers were leukemia, “other neoplasms,” NHL, and brain and nervous system cancers. ![]()

receiving chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Researchers have estimated the global incidence of 32 cancer types and deaths related to these malignancies in 2015.

The group’s data, published in JAMA Oncology, suggest there were 17.5 million cancer cases and 8.7 million cancer deaths last year.

There were 78,000 cases of Hodgkin lymphoma and 24,000 deaths from the disease, as well as 666,000 cases of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and 231,000 NHL deaths.

There were 154,000 cases of multiple myeloma and 101,000 deaths from the disease.

And there were 606,000 cases of leukemia, with 353,000 leukemia deaths. This included 161,000 cases of acute lymphoid leukemia (110,000 deaths), 191,000 cases of chronic lymphoid leukemia (61,000 deaths), 190,000 cases of acute myeloid leukemia (147,000 deaths), and 64,000 cases of chronic myeloid leukemia (35,000 deaths).

The data also show that, between 2005 and 2015, cancer cases increased by 33%, mostly due to population aging and growth, plus changes in age-specific cancer rates.

Globally, the odds of developing cancer during a lifetime were 1 in 3 for men and 1 in 4 for women in 2015.

Prostate cancer was the most common cancer in men (1.6 million cases), although tracheal, bronchus, and lung cancer was the leading cause of cancer deaths for men.

Breast cancer was the most common cancer for women (2.4 million cases) and the leading cause of cancer deaths in women.

The most common childhood cancers were leukemia, “other neoplasms,” NHL, and brain and nervous system cancers. ![]()

Half of CML patients can stop TKI therapy, study suggests

© Todd Buchanan 2016

SAN DIEGO—Updated results of the EURO-SKI trial support the idea that certain chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients can safely stop tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy.

About half of the patients studied, who had been in deep molecular remission for at least 1 year, had no evidence of relapse for at least 1 year after stopping TKI therapy.

Francis-Xavier Mahon, MD, PhD, of the Bergonie Cancer Center at the University of Bordeaux in France, presented this finding at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 787*).

Stopping treatment is an emerging goal of CML management. Several studies have demonstrated the feasibility of stopping treatment, and consistent results over time have validated the concept of treatment-free remission (TFR), Dr Mahon said.

“A sustained deep molecular response on long-term TKI therapy seems to be necessary prior to attempting TFR,” he noted. “However, the exact preconditions for stopping CML treatments are not yet defined.”

Dr Mahon and his colleagues studied 821 chronic phase CML patients treated with TKIs (imatinib, dasatinib, or nilotinib) for at least 3 years. The patients were in deep molecular remission (MR4) for at least a year.

Dr Mahon reported on an intention-to-stop-treatment analysis of 755 patients. Their median age at diagnosis was 52 years, median time from diagnosis to stopping TKI therapy was 7.7 years, median duration of TKI therapy was 7.4 years, and median duration of deep molecular remission before stopping TKI therapy was 4.7 years.

At a median follow-up of 14.9 months, about half of patients (378/755) were still alive and in major molecular response. Molecular recurrence-free survival was 61% at 6 months, 55% at 12 months, 52% at 18 months, 50% at 24 months, and 47% at 36 months.

Most loss of molecular response came within the first 6 months after stopping treatment. Most patients regained their previous remission level after resuming TKI therapy, and no study participants progressed to a dangerous state of advanced disease.

Dr Mahon noted that longer duration of imatinib therapy prior to stopping TKIs, optimally 5.8 years or longer, correlates to a higher probability of relapse-free survival. Gender, age, and other variables, such as Sokal scores, do not predict the probability of successful stopping.

“With inclusion and relapse criteria less strict than in many previous trials, and with decentralized but standardized PCR monitoring, stopping of TKI therapy in a large cohort of CML patients appears feasible and safe,” Dr Mahon said. “This trial demonstrates that half of patients are still off treatment without molecular recurrence after a median 15 months.”

Current guidelines recommend that most patients who achieve remission with TKI therapy continue taking the drugs indefinitely, yet it is unclear whether continued therapy is necessary for all patients.

The European Leukemia Net are expected to propose new guidelines in the next 6 months, which Dr Mahon hopes will define a consensus regarding durability of TKI therapy and provide recommendations on whether stopping TKIs can be moved into the clinic for appropriate patients. ![]()

*Information presented at the meeting differs from the abstract.

© Todd Buchanan 2016

SAN DIEGO—Updated results of the EURO-SKI trial support the idea that certain chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients can safely stop tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy.

About half of the patients studied, who had been in deep molecular remission for at least 1 year, had no evidence of relapse for at least 1 year after stopping TKI therapy.

Francis-Xavier Mahon, MD, PhD, of the Bergonie Cancer Center at the University of Bordeaux in France, presented this finding at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 787*).

Stopping treatment is an emerging goal of CML management. Several studies have demonstrated the feasibility of stopping treatment, and consistent results over time have validated the concept of treatment-free remission (TFR), Dr Mahon said.

“A sustained deep molecular response on long-term TKI therapy seems to be necessary prior to attempting TFR,” he noted. “However, the exact preconditions for stopping CML treatments are not yet defined.”

Dr Mahon and his colleagues studied 821 chronic phase CML patients treated with TKIs (imatinib, dasatinib, or nilotinib) for at least 3 years. The patients were in deep molecular remission (MR4) for at least a year.

Dr Mahon reported on an intention-to-stop-treatment analysis of 755 patients. Their median age at diagnosis was 52 years, median time from diagnosis to stopping TKI therapy was 7.7 years, median duration of TKI therapy was 7.4 years, and median duration of deep molecular remission before stopping TKI therapy was 4.7 years.

At a median follow-up of 14.9 months, about half of patients (378/755) were still alive and in major molecular response. Molecular recurrence-free survival was 61% at 6 months, 55% at 12 months, 52% at 18 months, 50% at 24 months, and 47% at 36 months.

Most loss of molecular response came within the first 6 months after stopping treatment. Most patients regained their previous remission level after resuming TKI therapy, and no study participants progressed to a dangerous state of advanced disease.

Dr Mahon noted that longer duration of imatinib therapy prior to stopping TKIs, optimally 5.8 years or longer, correlates to a higher probability of relapse-free survival. Gender, age, and other variables, such as Sokal scores, do not predict the probability of successful stopping.

“With inclusion and relapse criteria less strict than in many previous trials, and with decentralized but standardized PCR monitoring, stopping of TKI therapy in a large cohort of CML patients appears feasible and safe,” Dr Mahon said. “This trial demonstrates that half of patients are still off treatment without molecular recurrence after a median 15 months.”

Current guidelines recommend that most patients who achieve remission with TKI therapy continue taking the drugs indefinitely, yet it is unclear whether continued therapy is necessary for all patients.

The European Leukemia Net are expected to propose new guidelines in the next 6 months, which Dr Mahon hopes will define a consensus regarding durability of TKI therapy and provide recommendations on whether stopping TKIs can be moved into the clinic for appropriate patients. ![]()

*Information presented at the meeting differs from the abstract.

© Todd Buchanan 2016

SAN DIEGO—Updated results of the EURO-SKI trial support the idea that certain chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients can safely stop tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy.

About half of the patients studied, who had been in deep molecular remission for at least 1 year, had no evidence of relapse for at least 1 year after stopping TKI therapy.

Francis-Xavier Mahon, MD, PhD, of the Bergonie Cancer Center at the University of Bordeaux in France, presented this finding at the 2016 ASH Annual Meeting (abstract 787*).

Stopping treatment is an emerging goal of CML management. Several studies have demonstrated the feasibility of stopping treatment, and consistent results over time have validated the concept of treatment-free remission (TFR), Dr Mahon said.

“A sustained deep molecular response on long-term TKI therapy seems to be necessary prior to attempting TFR,” he noted. “However, the exact preconditions for stopping CML treatments are not yet defined.”

Dr Mahon and his colleagues studied 821 chronic phase CML patients treated with TKIs (imatinib, dasatinib, or nilotinib) for at least 3 years. The patients were in deep molecular remission (MR4) for at least a year.

Dr Mahon reported on an intention-to-stop-treatment analysis of 755 patients. Their median age at diagnosis was 52 years, median time from diagnosis to stopping TKI therapy was 7.7 years, median duration of TKI therapy was 7.4 years, and median duration of deep molecular remission before stopping TKI therapy was 4.7 years.

At a median follow-up of 14.9 months, about half of patients (378/755) were still alive and in major molecular response. Molecular recurrence-free survival was 61% at 6 months, 55% at 12 months, 52% at 18 months, 50% at 24 months, and 47% at 36 months.

Most loss of molecular response came within the first 6 months after stopping treatment. Most patients regained their previous remission level after resuming TKI therapy, and no study participants progressed to a dangerous state of advanced disease.

Dr Mahon noted that longer duration of imatinib therapy prior to stopping TKIs, optimally 5.8 years or longer, correlates to a higher probability of relapse-free survival. Gender, age, and other variables, such as Sokal scores, do not predict the probability of successful stopping.

“With inclusion and relapse criteria less strict than in many previous trials, and with decentralized but standardized PCR monitoring, stopping of TKI therapy in a large cohort of CML patients appears feasible and safe,” Dr Mahon said. “This trial demonstrates that half of patients are still off treatment without molecular recurrence after a median 15 months.”

Current guidelines recommend that most patients who achieve remission with TKI therapy continue taking the drugs indefinitely, yet it is unclear whether continued therapy is necessary for all patients.

The European Leukemia Net are expected to propose new guidelines in the next 6 months, which Dr Mahon hopes will define a consensus regarding durability of TKI therapy and provide recommendations on whether stopping TKIs can be moved into the clinic for appropriate patients. ![]()

*Information presented at the meeting differs from the abstract.

VIDEO: Half-dose TKI safe, cost-effective in CML in stable remission

SAN DIEGO – Tyrosine kinase inhibitors have dramatically improved survival for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia, but for some patients with solid stable remissions, halving the TKI dose or even stopping therapy altogether, at least temporarily, appears to be safe and to offer both health and financial benefits,

In the British Destiny [De-escalation and Stopping Treatment of Imatinib, Nilotinib, or Sprycel (dasatinib)], there were 12 molecular relapses occurring between the second and twelfth month of dose reduction among 174 patients with either an MR3 or MR4 molecular response, and all patients had restoration of molecular remissions after resumption of full dose TKIs.

Coinvestigator Mhairi Copland, MD, PhD, of the University of Glasgow, Scotland, discussed in a video interview the potential clinical benefits of lower-dose therapy in patients in stable CML remissions, and notes that de-escalation strategy is associated with a nearly 50% saving in costs compared with full-dose TKI therapy.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN DIEGO – Tyrosine kinase inhibitors have dramatically improved survival for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia, but for some patients with solid stable remissions, halving the TKI dose or even stopping therapy altogether, at least temporarily, appears to be safe and to offer both health and financial benefits,

In the British Destiny [De-escalation and Stopping Treatment of Imatinib, Nilotinib, or Sprycel (dasatinib)], there were 12 molecular relapses occurring between the second and twelfth month of dose reduction among 174 patients with either an MR3 or MR4 molecular response, and all patients had restoration of molecular remissions after resumption of full dose TKIs.

Coinvestigator Mhairi Copland, MD, PhD, of the University of Glasgow, Scotland, discussed in a video interview the potential clinical benefits of lower-dose therapy in patients in stable CML remissions, and notes that de-escalation strategy is associated with a nearly 50% saving in costs compared with full-dose TKI therapy.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

SAN DIEGO – Tyrosine kinase inhibitors have dramatically improved survival for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia, but for some patients with solid stable remissions, halving the TKI dose or even stopping therapy altogether, at least temporarily, appears to be safe and to offer both health and financial benefits,

In the British Destiny [De-escalation and Stopping Treatment of Imatinib, Nilotinib, or Sprycel (dasatinib)], there were 12 molecular relapses occurring between the second and twelfth month of dose reduction among 174 patients with either an MR3 or MR4 molecular response, and all patients had restoration of molecular remissions after resumption of full dose TKIs.

Coinvestigator Mhairi Copland, MD, PhD, of the University of Glasgow, Scotland, discussed in a video interview the potential clinical benefits of lower-dose therapy in patients in stable CML remissions, and notes that de-escalation strategy is associated with a nearly 50% saving in costs compared with full-dose TKI therapy.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT ASH 2016

Halving the TKI dose safe, cost effective in CML patients with stable remissions

SAN DIEGO – For some chronic myeloid leukemia patients with solid, stable remissions, halving their dose of a tyrosine kinase inhibitor – or even stopping therapy altogether, at least temporarily – appears to be safe and to offer both health and financial benefits, European investigators said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

In the British De-escalation and Stopping Treatment of Imatinib, Nilotinib, or Sprycel [dasatinib], or Destiny Study, a total of 12 molecular relapses occurred between the second and twelfth month of dose reduction among 174 patients with either an MR3 or MR4 molecular response, and all 12 patients had restoration of molecular remissions after resumption of full dose TKIs, reported co-investigator Mhairi Copland, MD, PhD, from the University of Glasgow, Scotland.

“What we wanted to explore in the Destiny study is cutting the dose of tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy in CML by half, followed by stopping therapy not just in patients with undetectable disease but also with stable low levels of disease,” Dr. Copland said during a briefing at the meeting.

“We hypothesized that more patients would be able to reduce therapy safely, and a proportion of these would be able to go on to stop therapy; also, that the patients on half-dose therapy would have reduced amount of side effects compared to those on full-dose therapy,” she added.

Several recent studies, including the EURO-SKI trial, have shown that it is safe to stop TKI therapy in those patients who are optimally responding and have undetectable levels of the BCR-ABL transcript.

Rendezvous with Destiny

In Destiny, the investigators enrolled patients with “good, but not perfect” molecular responses: MR3 or better, defined as a minimum of 3 consecutive tests each with greater than 10,000 ABL control transcripts following a minimum of 3 years on a TKI at standard prescribed doses. The median overall duration of TKI therapy was 7 years.

Participants on imatinib had their daily doses reduced to 200 mg, those on nilotinib had their doses cut back to 200 mg twice daily, and those on dasatinib had their quotidian doses halved to 50 mg.

After 12 months of half-dose therapy, molecular recurrence, defined as a loss of MR3 on two consecutive samples, was detected in 9 of 49 patients (18.4%) with MR3 but not MR4 remissions, compared with 3 of 125 patients (2.4%) with MR4 or better remissions (P less than .001).

The median time to relapse was 4.4 months among MR3/not 4 patients vs. 8.7 months for MR4 or better patients.

The probability of molecular recurrence on dose reduction was unrelated to either age, sex, performance status, type of TKI, or the duration of TKI therapy (median 7 years overall).

No patients experienced either progression to advanced phase disease or loss of cytogenetic response. During the course of follow-up, one patient died, and there were 15 serious adverse events, but these were determined to be unrelated to either CML or TKI treatment.

All 12 patients who experienced molecular recurrence regained MR3 within 4 months of resuming TKI therapy at the full dose.

As noted before, patient-reported side effects such as lethargy, diarrhea, rash, nausea, periorbital edema, and hair thinning decreased during the first 3 months of de-escalation, but not thereafter. Dr. Copland said that patients had generally good quality-of-life scores at study entry, suggesting that they were likely not especially bothered by TKI side effects in the first place.

The investigators calculated that for the 174 patients, halving treatment would save an estimated £1,943,364 ($2,474,679) from an expected TKI budget of £4,156,969 ($5,293,484), a savings of 46.7%. Estimated savings were similar for patients with MR4 or better alone (47.7%) and for those with a major molecular response (44.2%).

EURO-SKI Update

Also at ASH 2016, Francois-Xavier Mahon, MD, PhD, from the University of Bordeaux, France, reported additional follow-up data from the EURO-SKI trial, results of which were first reported at the 2016 annual meeting of the European Hematology Association in Copenhagen.

The investigators found that 50% of 755 assessable patients with CML were free of molecular recurrence at 24 months, as were 47% at 36 months.

As reported previously, patients who had been on a TKI for more than 5.8 years before attempting to stop had a lower rate of relapse (34.5%) than patients who had been on therapy for less than 5.8 years (57.4%). Each additional year of TKI therapy was associated with an approximately 16% better chance of successful TKI cessation.

“With inclusion and relapse criteria less strict than in many previous trials, and with decentralized but standardized PCR monitoring, stopping of TKI therapy in a large cohort of CML patients appears feasible and safe,” Dr. Mahon said at the briefing.

The British Destiny Study was supported by Newcastle University. Dr. Copland reported honoraria, advisory board memberships, and/or research funding from Amgen, Pfizer, Shire, BMS, and Ariad.

EURO-SKI was sponsored by the European LeukemiaNet. Dr. Mahon has previously disclosed being on the scientific advisory board and receiving honoraria from Novartis Oncology and BMS, and serving as consultant to those companies and to Pfizer.

SAN DIEGO – For some chronic myeloid leukemia patients with solid, stable remissions, halving their dose of a tyrosine kinase inhibitor – or even stopping therapy altogether, at least temporarily – appears to be safe and to offer both health and financial benefits, European investigators said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

In the British De-escalation and Stopping Treatment of Imatinib, Nilotinib, or Sprycel [dasatinib], or Destiny Study, a total of 12 molecular relapses occurred between the second and twelfth month of dose reduction among 174 patients with either an MR3 or MR4 molecular response, and all 12 patients had restoration of molecular remissions after resumption of full dose TKIs, reported co-investigator Mhairi Copland, MD, PhD, from the University of Glasgow, Scotland.

“What we wanted to explore in the Destiny study is cutting the dose of tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy in CML by half, followed by stopping therapy not just in patients with undetectable disease but also with stable low levels of disease,” Dr. Copland said during a briefing at the meeting.

“We hypothesized that more patients would be able to reduce therapy safely, and a proportion of these would be able to go on to stop therapy; also, that the patients on half-dose therapy would have reduced amount of side effects compared to those on full-dose therapy,” she added.

Several recent studies, including the EURO-SKI trial, have shown that it is safe to stop TKI therapy in those patients who are optimally responding and have undetectable levels of the BCR-ABL transcript.

Rendezvous with Destiny

In Destiny, the investigators enrolled patients with “good, but not perfect” molecular responses: MR3 or better, defined as a minimum of 3 consecutive tests each with greater than 10,000 ABL control transcripts following a minimum of 3 years on a TKI at standard prescribed doses. The median overall duration of TKI therapy was 7 years.

Participants on imatinib had their daily doses reduced to 200 mg, those on nilotinib had their doses cut back to 200 mg twice daily, and those on dasatinib had their quotidian doses halved to 50 mg.

After 12 months of half-dose therapy, molecular recurrence, defined as a loss of MR3 on two consecutive samples, was detected in 9 of 49 patients (18.4%) with MR3 but not MR4 remissions, compared with 3 of 125 patients (2.4%) with MR4 or better remissions (P less than .001).

The median time to relapse was 4.4 months among MR3/not 4 patients vs. 8.7 months for MR4 or better patients.

The probability of molecular recurrence on dose reduction was unrelated to either age, sex, performance status, type of TKI, or the duration of TKI therapy (median 7 years overall).

No patients experienced either progression to advanced phase disease or loss of cytogenetic response. During the course of follow-up, one patient died, and there were 15 serious adverse events, but these were determined to be unrelated to either CML or TKI treatment.

All 12 patients who experienced molecular recurrence regained MR3 within 4 months of resuming TKI therapy at the full dose.

As noted before, patient-reported side effects such as lethargy, diarrhea, rash, nausea, periorbital edema, and hair thinning decreased during the first 3 months of de-escalation, but not thereafter. Dr. Copland said that patients had generally good quality-of-life scores at study entry, suggesting that they were likely not especially bothered by TKI side effects in the first place.

The investigators calculated that for the 174 patients, halving treatment would save an estimated £1,943,364 ($2,474,679) from an expected TKI budget of £4,156,969 ($5,293,484), a savings of 46.7%. Estimated savings were similar for patients with MR4 or better alone (47.7%) and for those with a major molecular response (44.2%).

EURO-SKI Update

Also at ASH 2016, Francois-Xavier Mahon, MD, PhD, from the University of Bordeaux, France, reported additional follow-up data from the EURO-SKI trial, results of which were first reported at the 2016 annual meeting of the European Hematology Association in Copenhagen.

The investigators found that 50% of 755 assessable patients with CML were free of molecular recurrence at 24 months, as were 47% at 36 months.

As reported previously, patients who had been on a TKI for more than 5.8 years before attempting to stop had a lower rate of relapse (34.5%) than patients who had been on therapy for less than 5.8 years (57.4%). Each additional year of TKI therapy was associated with an approximately 16% better chance of successful TKI cessation.

“With inclusion and relapse criteria less strict than in many previous trials, and with decentralized but standardized PCR monitoring, stopping of TKI therapy in a large cohort of CML patients appears feasible and safe,” Dr. Mahon said at the briefing.

The British Destiny Study was supported by Newcastle University. Dr. Copland reported honoraria, advisory board memberships, and/or research funding from Amgen, Pfizer, Shire, BMS, and Ariad.

EURO-SKI was sponsored by the European LeukemiaNet. Dr. Mahon has previously disclosed being on the scientific advisory board and receiving honoraria from Novartis Oncology and BMS, and serving as consultant to those companies and to Pfizer.

SAN DIEGO – For some chronic myeloid leukemia patients with solid, stable remissions, halving their dose of a tyrosine kinase inhibitor – or even stopping therapy altogether, at least temporarily – appears to be safe and to offer both health and financial benefits, European investigators said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

In the British De-escalation and Stopping Treatment of Imatinib, Nilotinib, or Sprycel [dasatinib], or Destiny Study, a total of 12 molecular relapses occurred between the second and twelfth month of dose reduction among 174 patients with either an MR3 or MR4 molecular response, and all 12 patients had restoration of molecular remissions after resumption of full dose TKIs, reported co-investigator Mhairi Copland, MD, PhD, from the University of Glasgow, Scotland.

“What we wanted to explore in the Destiny study is cutting the dose of tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy in CML by half, followed by stopping therapy not just in patients with undetectable disease but also with stable low levels of disease,” Dr. Copland said during a briefing at the meeting.

“We hypothesized that more patients would be able to reduce therapy safely, and a proportion of these would be able to go on to stop therapy; also, that the patients on half-dose therapy would have reduced amount of side effects compared to those on full-dose therapy,” she added.

Several recent studies, including the EURO-SKI trial, have shown that it is safe to stop TKI therapy in those patients who are optimally responding and have undetectable levels of the BCR-ABL transcript.

Rendezvous with Destiny

In Destiny, the investigators enrolled patients with “good, but not perfect” molecular responses: MR3 or better, defined as a minimum of 3 consecutive tests each with greater than 10,000 ABL control transcripts following a minimum of 3 years on a TKI at standard prescribed doses. The median overall duration of TKI therapy was 7 years.

Participants on imatinib had their daily doses reduced to 200 mg, those on nilotinib had their doses cut back to 200 mg twice daily, and those on dasatinib had their quotidian doses halved to 50 mg.

After 12 months of half-dose therapy, molecular recurrence, defined as a loss of MR3 on two consecutive samples, was detected in 9 of 49 patients (18.4%) with MR3 but not MR4 remissions, compared with 3 of 125 patients (2.4%) with MR4 or better remissions (P less than .001).

The median time to relapse was 4.4 months among MR3/not 4 patients vs. 8.7 months for MR4 or better patients.

The probability of molecular recurrence on dose reduction was unrelated to either age, sex, performance status, type of TKI, or the duration of TKI therapy (median 7 years overall).

No patients experienced either progression to advanced phase disease or loss of cytogenetic response. During the course of follow-up, one patient died, and there were 15 serious adverse events, but these were determined to be unrelated to either CML or TKI treatment.

All 12 patients who experienced molecular recurrence regained MR3 within 4 months of resuming TKI therapy at the full dose.

As noted before, patient-reported side effects such as lethargy, diarrhea, rash, nausea, periorbital edema, and hair thinning decreased during the first 3 months of de-escalation, but not thereafter. Dr. Copland said that patients had generally good quality-of-life scores at study entry, suggesting that they were likely not especially bothered by TKI side effects in the first place.

The investigators calculated that for the 174 patients, halving treatment would save an estimated £1,943,364 ($2,474,679) from an expected TKI budget of £4,156,969 ($5,293,484), a savings of 46.7%. Estimated savings were similar for patients with MR4 or better alone (47.7%) and for those with a major molecular response (44.2%).

EURO-SKI Update

Also at ASH 2016, Francois-Xavier Mahon, MD, PhD, from the University of Bordeaux, France, reported additional follow-up data from the EURO-SKI trial, results of which were first reported at the 2016 annual meeting of the European Hematology Association in Copenhagen.

The investigators found that 50% of 755 assessable patients with CML were free of molecular recurrence at 24 months, as were 47% at 36 months.

As reported previously, patients who had been on a TKI for more than 5.8 years before attempting to stop had a lower rate of relapse (34.5%) than patients who had been on therapy for less than 5.8 years (57.4%). Each additional year of TKI therapy was associated with an approximately 16% better chance of successful TKI cessation.

“With inclusion and relapse criteria less strict than in many previous trials, and with decentralized but standardized PCR monitoring, stopping of TKI therapy in a large cohort of CML patients appears feasible and safe,” Dr. Mahon said at the briefing.

The British Destiny Study was supported by Newcastle University. Dr. Copland reported honoraria, advisory board memberships, and/or research funding from Amgen, Pfizer, Shire, BMS, and Ariad.

EURO-SKI was sponsored by the European LeukemiaNet. Dr. Mahon has previously disclosed being on the scientific advisory board and receiving honoraria from Novartis Oncology and BMS, and serving as consultant to those companies and to Pfizer.

FROM ASH 2016

Key clinical point: Halving TKI doses in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in stable remission is safe and cost effective.

Major finding: After halving TKI doses, there were 12 molecular relapses among 174 patients with an MR3 or better molecular response.

Data source: Prospective dose-reduction study in 174 patients with CML in MR3 remission or better.

Disclosures: The British Destiny Study was supported by Newcastle University. Dr. Copland reported honoraria, advisory board memberships, and/or research funding from Amgen, Pfizer, Shire, BMS, and Ariad. EURO-SKI was sponsored by the European LeukemiaNet. Dr. Mahon has previously disclosed being on the scientific advisory board and receiving honoraria from Novartis Oncology and BMS, and serving as consultant to those companies and to Pfizer.

FDA grants full approval for ponatinib

Photo from Business Wire

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted full approval for the kinase inhibitor ponatinib (Iclusig®) and updated the drug’s label.

Ponatinib now has full approval as a treatment for adults with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) or Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL) when no other tyrosine kinase inhibitor is indicated.

Ponatinib is also approved to treat adults with T315I-positive CML or T315I-positive Ph+ ALL.

Ponatinib was initially approved in December 2012 under the FDA’s accelerated approval program.

This program allows the FDA to approve a drug to treat a serious or life-threatening disease based on clinical data showing the drug has an effect on a surrogate endpoint reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit to patients.

The company developing the drug must conduct post-approval research to determine if the drug provides a clinical benefit. If so, the drug can be granted full approval.

The full approval and label update for ponatinib is based on 48-month follow-up data (as of August 2015) from the phase 2 PACE trial, which enrolled heavily pretreated patients with resistant or intolerant CML or Ph+ ALL. These data were presented at the 2016 ASCO Annual Meeting.

“The longer follow up of the PACE study confirms the clinical benefit of ponatinib in this setting,” said Jorge Cortes, MD, a professor at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston and a leading investigator in the PACE trial.

“We had learned from the initial report of the high response rate with ponatinib among CML patients with resistance or intolerance to prior therapies. The 4-year follow-up and updated safety profile demonstrate durability of responses in this heavily pretreated population. These results solidify ponatinib as an important and valuable treatment option for refractory patients with CML where no other TKI therapy is appropriate, including those who have the T315I mutation.”

Past problems with ponatinib

Previous follow-up data from the PACE trial, collected in 2013, suggested ponatinib can increase the risk of thrombotic events. When these data came to light, officials in the US and European Union, where ponatinib had already been approved, began to investigate the drug.

Ponatinib was pulled from the US market for a little over 2 months, and trials of the drug were placed on partial hold while the FDA evaluated the drug’s safety. Ponatinib went back on the market in January 2014, with new safety measures in place.

Ponatinib was not pulled from the market in the European Union, but the European Medicine’s Agency released recommendations for safer use of the drug. The Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use reviewed data on ponatinib and decided its benefits outweigh its risks. ![]()

Photo from Business Wire

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted full approval for the kinase inhibitor ponatinib (Iclusig®) and updated the drug’s label.

Ponatinib now has full approval as a treatment for adults with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) or Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL) when no other tyrosine kinase inhibitor is indicated.

Ponatinib is also approved to treat adults with T315I-positive CML or T315I-positive Ph+ ALL.

Ponatinib was initially approved in December 2012 under the FDA’s accelerated approval program.

This program allows the FDA to approve a drug to treat a serious or life-threatening disease based on clinical data showing the drug has an effect on a surrogate endpoint reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit to patients.

The company developing the drug must conduct post-approval research to determine if the drug provides a clinical benefit. If so, the drug can be granted full approval.

The full approval and label update for ponatinib is based on 48-month follow-up data (as of August 2015) from the phase 2 PACE trial, which enrolled heavily pretreated patients with resistant or intolerant CML or Ph+ ALL. These data were presented at the 2016 ASCO Annual Meeting.

“The longer follow up of the PACE study confirms the clinical benefit of ponatinib in this setting,” said Jorge Cortes, MD, a professor at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston and a leading investigator in the PACE trial.

“We had learned from the initial report of the high response rate with ponatinib among CML patients with resistance or intolerance to prior therapies. The 4-year follow-up and updated safety profile demonstrate durability of responses in this heavily pretreated population. These results solidify ponatinib as an important and valuable treatment option for refractory patients with CML where no other TKI therapy is appropriate, including those who have the T315I mutation.”

Past problems with ponatinib

Previous follow-up data from the PACE trial, collected in 2013, suggested ponatinib can increase the risk of thrombotic events. When these data came to light, officials in the US and European Union, where ponatinib had already been approved, began to investigate the drug.

Ponatinib was pulled from the US market for a little over 2 months, and trials of the drug were placed on partial hold while the FDA evaluated the drug’s safety. Ponatinib went back on the market in January 2014, with new safety measures in place.

Ponatinib was not pulled from the market in the European Union, but the European Medicine’s Agency released recommendations for safer use of the drug. The Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use reviewed data on ponatinib and decided its benefits outweigh its risks. ![]()

Photo from Business Wire

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted full approval for the kinase inhibitor ponatinib (Iclusig®) and updated the drug’s label.