User login

Time to ‘step up’ global response to Zika outbreak

WASHINGTON – Once again, the United States is ill-prepared to handle the threat of a global pandemic entering its borders and must commit resources to the development of a Zika virus vaccine, said Dr. Victor J. Dzau, president of the National Academy of Medicine.

Dr. Dzau issued this call to action on Feb. 16 at a workshop centered around the recent Zika virus outbreak and how to combat it. The workshop was convened at the request of the Health and Human Services department.

Calling Zika virus “a new threat to global health,” Dr. Dzau said the best course of action is for the U.S. and health authorities around the world is to create a “global health risk framework” that would actively work to identify new and emerging public health threats and prevent them from becoming outbreaks. This framework would consist of a global architecture to reduce risk and mitigate the next global health crisis, identification of key resources and applications before an outbreak occurs, successful containment of future outbreaks, and coordinated responses “informed by good planning and evidence, not fear or politics,” he said.

“Global leaders need to step up,” said Dr. Dzau. “They need to step up investments to improve their response and also their preparedness for pandemics and infectious outbreaks.”

One of the most serious concerns about Zika virus has been its effects on pregnant women, as infected mothers have been bearing children with microcephaly in Central and South America. Dr. Laura E. Riley of Massachusetts General Hospital spoke about the gaps in what ob.gyns. currently know about the virus and the best way to treat pregnant women who may have been exposed.

Testing for Zika immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies is the “first step” in treating any pregnant woman who has traveled and may have been exposed to the virus, she said. However, Dr. Riley noted that the test is relatively new and “we’re putting a lot of stock into this test that we don’t have a lot of information about.”

Citing a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in February, Dr. Riley said that evidence of the link between Zika virus infections and microcephaly is stronger than ever, but there is still doubt as to exactly how microcephaly is caused, and at what point during the pregnancy symptoms begin to present in the fetus.

Serial ultrasounds have shown the slowing of fetal development over the course of a pregnancy – specifically in two Brazilian women examined for the report – but data is still sparse. “The causal relationship between Zika virus and other adverse pregnancy outcomes” is also of critical importance, said Dr. Riley. “I think we have pretty well established the association with microcephaly [but] there may be other neurologic abnormalities that we should be aware of and looking for.”

These other conditions include lissencephaly and intracranial calcification, Dr. Riley said.

“We don’t know what the infection rate is, but more importantly, the incidence of internal fetal transmission by trimester is particularly important as well, and what are the factors that influence that transmission?” asked Dr. Riley. “Is it the severity of internal infection? Is it the maternal immune response? We don’t know. We have information that we can glean from other infections.”

For now, said Dr. Riley is relying largely on the CDC guidance in advising patients.

“I’m taking the CDC guidance and I’m taking my own knowledge of [cytomegalovirus] and rubella and I’m trying to put it all together for Zika virus, for which I know very little,” she said.

Dr. Dzau and Dr. Riley did not report having any relevant financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – Once again, the United States is ill-prepared to handle the threat of a global pandemic entering its borders and must commit resources to the development of a Zika virus vaccine, said Dr. Victor J. Dzau, president of the National Academy of Medicine.

Dr. Dzau issued this call to action on Feb. 16 at a workshop centered around the recent Zika virus outbreak and how to combat it. The workshop was convened at the request of the Health and Human Services department.

Calling Zika virus “a new threat to global health,” Dr. Dzau said the best course of action is for the U.S. and health authorities around the world is to create a “global health risk framework” that would actively work to identify new and emerging public health threats and prevent them from becoming outbreaks. This framework would consist of a global architecture to reduce risk and mitigate the next global health crisis, identification of key resources and applications before an outbreak occurs, successful containment of future outbreaks, and coordinated responses “informed by good planning and evidence, not fear or politics,” he said.

“Global leaders need to step up,” said Dr. Dzau. “They need to step up investments to improve their response and also their preparedness for pandemics and infectious outbreaks.”

One of the most serious concerns about Zika virus has been its effects on pregnant women, as infected mothers have been bearing children with microcephaly in Central and South America. Dr. Laura E. Riley of Massachusetts General Hospital spoke about the gaps in what ob.gyns. currently know about the virus and the best way to treat pregnant women who may have been exposed.

Testing for Zika immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies is the “first step” in treating any pregnant woman who has traveled and may have been exposed to the virus, she said. However, Dr. Riley noted that the test is relatively new and “we’re putting a lot of stock into this test that we don’t have a lot of information about.”

Citing a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in February, Dr. Riley said that evidence of the link between Zika virus infections and microcephaly is stronger than ever, but there is still doubt as to exactly how microcephaly is caused, and at what point during the pregnancy symptoms begin to present in the fetus.

Serial ultrasounds have shown the slowing of fetal development over the course of a pregnancy – specifically in two Brazilian women examined for the report – but data is still sparse. “The causal relationship between Zika virus and other adverse pregnancy outcomes” is also of critical importance, said Dr. Riley. “I think we have pretty well established the association with microcephaly [but] there may be other neurologic abnormalities that we should be aware of and looking for.”

These other conditions include lissencephaly and intracranial calcification, Dr. Riley said.

“We don’t know what the infection rate is, but more importantly, the incidence of internal fetal transmission by trimester is particularly important as well, and what are the factors that influence that transmission?” asked Dr. Riley. “Is it the severity of internal infection? Is it the maternal immune response? We don’t know. We have information that we can glean from other infections.”

For now, said Dr. Riley is relying largely on the CDC guidance in advising patients.

“I’m taking the CDC guidance and I’m taking my own knowledge of [cytomegalovirus] and rubella and I’m trying to put it all together for Zika virus, for which I know very little,” she said.

Dr. Dzau and Dr. Riley did not report having any relevant financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – Once again, the United States is ill-prepared to handle the threat of a global pandemic entering its borders and must commit resources to the development of a Zika virus vaccine, said Dr. Victor J. Dzau, president of the National Academy of Medicine.

Dr. Dzau issued this call to action on Feb. 16 at a workshop centered around the recent Zika virus outbreak and how to combat it. The workshop was convened at the request of the Health and Human Services department.

Calling Zika virus “a new threat to global health,” Dr. Dzau said the best course of action is for the U.S. and health authorities around the world is to create a “global health risk framework” that would actively work to identify new and emerging public health threats and prevent them from becoming outbreaks. This framework would consist of a global architecture to reduce risk and mitigate the next global health crisis, identification of key resources and applications before an outbreak occurs, successful containment of future outbreaks, and coordinated responses “informed by good planning and evidence, not fear or politics,” he said.

“Global leaders need to step up,” said Dr. Dzau. “They need to step up investments to improve their response and also their preparedness for pandemics and infectious outbreaks.”

One of the most serious concerns about Zika virus has been its effects on pregnant women, as infected mothers have been bearing children with microcephaly in Central and South America. Dr. Laura E. Riley of Massachusetts General Hospital spoke about the gaps in what ob.gyns. currently know about the virus and the best way to treat pregnant women who may have been exposed.

Testing for Zika immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies is the “first step” in treating any pregnant woman who has traveled and may have been exposed to the virus, she said. However, Dr. Riley noted that the test is relatively new and “we’re putting a lot of stock into this test that we don’t have a lot of information about.”

Citing a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in February, Dr. Riley said that evidence of the link between Zika virus infections and microcephaly is stronger than ever, but there is still doubt as to exactly how microcephaly is caused, and at what point during the pregnancy symptoms begin to present in the fetus.

Serial ultrasounds have shown the slowing of fetal development over the course of a pregnancy – specifically in two Brazilian women examined for the report – but data is still sparse. “The causal relationship between Zika virus and other adverse pregnancy outcomes” is also of critical importance, said Dr. Riley. “I think we have pretty well established the association with microcephaly [but] there may be other neurologic abnormalities that we should be aware of and looking for.”

These other conditions include lissencephaly and intracranial calcification, Dr. Riley said.

“We don’t know what the infection rate is, but more importantly, the incidence of internal fetal transmission by trimester is particularly important as well, and what are the factors that influence that transmission?” asked Dr. Riley. “Is it the severity of internal infection? Is it the maternal immune response? We don’t know. We have information that we can glean from other infections.”

For now, said Dr. Riley is relying largely on the CDC guidance in advising patients.

“I’m taking the CDC guidance and I’m taking my own knowledge of [cytomegalovirus] and rubella and I’m trying to put it all together for Zika virus, for which I know very little,” she said.

Dr. Dzau and Dr. Riley did not report having any relevant financial disclosures.

FROM A MEETING OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF MEDICINE

Rheumatic problems plague chikungunya patients

Approximately one-third of chikungunya patients who acquired the disease during Caribbean travel reported postchikungunya muscle pain, joint pain, and joint swelling, according to data for 28 patients seen at a single center in 2014. The findings were published in Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease (2016. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2016.01.009).

The researchers contacted 19 of the patients approximately 13 months after their original diagnoses. Of these, 37% described ongoing rheumatic problems; 32% reported joint pain, 32% reported joint swelling, and 26% reported muscle pain.

Dr. Cosmina Zeana of Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center, New York, and colleagues initially identified 28 adult patients with a median age of 52 years. Most were Hispanic (96%) and half were women (54%). The average length of stay in the Caribbean was 30 days, and 82% had visited the Dominican Republic. The follow-up data were collected via a telephone questionnaire.

Chikungunya has become endemic in Latin America, the researchers noted. “Of increasing concern is the occurrence of persistent rheumatic and general disabling symptoms that can last for several years following acute infection,” they wrote. Transmission of chikungunya has been documented throughout the Caribbean, but this study is the first known assessment of postchikungunya rheumatologic disorders among individuals diagnosed with acute chikungunya after traveling to the Caribbean in particular, they added.

At follow-up, three patients without preexisting rheumatic disease met criteria for diffuse postchikungunya (pCHIK) musculoskeletal disorders. In addition, four patients with preexisting rheumatic disease reported an increase in symptom severity including worsening knee osteoarthritis in both knees (one patient) and increased joint involvement (three patients).

Significantly more patients with preexisting disease reported using pain medication, compared with those without preexisting disease. However, no significant differences appeared in the percentage of patients in each group reporting other symptoms including joint pain, muscle pain, and joint swelling.

Nearly all the patients presented for acute care with fever (99%), joint pain (89%), myalgia (70%), and joint swelling (68%). The median pain level was 8 on a scale of 1-10.

Other symptoms reported at the time of acute diagnosis included gastrointestinal problems (59%), headache (48%), and rash (48%). Almost half the patients (46%) required inpatient care, with complications including hypotensive episodes, syncope, electrolyte imbalance, and thrombocytopenia.

“Patients seeking pretravel health care in preparation for a trip to the Caribbean – as to any other CHIK-endemic 185 region – need to be comprehensively counseled about the health risks related to the acute stage of the infection as well as related to the risk for developing a potentially long-lasting rheumatic disorder,” the researchers said.

“An integrated care plan for patients with acute CHIK consisting of follow-up appointments with the primary care provider and a rheumatologist with the aim of reducing the time to identify patients with pCHIK rheumatic disorders and initiation of optimal disease management may be useful and need further study,” they added.

The findings were limited by several factors including small sample size, use of self-reports, and narrow geographic range. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Approximately one-third of chikungunya patients who acquired the disease during Caribbean travel reported postchikungunya muscle pain, joint pain, and joint swelling, according to data for 28 patients seen at a single center in 2014. The findings were published in Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease (2016. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2016.01.009).

The researchers contacted 19 of the patients approximately 13 months after their original diagnoses. Of these, 37% described ongoing rheumatic problems; 32% reported joint pain, 32% reported joint swelling, and 26% reported muscle pain.

Dr. Cosmina Zeana of Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center, New York, and colleagues initially identified 28 adult patients with a median age of 52 years. Most were Hispanic (96%) and half were women (54%). The average length of stay in the Caribbean was 30 days, and 82% had visited the Dominican Republic. The follow-up data were collected via a telephone questionnaire.

Chikungunya has become endemic in Latin America, the researchers noted. “Of increasing concern is the occurrence of persistent rheumatic and general disabling symptoms that can last for several years following acute infection,” they wrote. Transmission of chikungunya has been documented throughout the Caribbean, but this study is the first known assessment of postchikungunya rheumatologic disorders among individuals diagnosed with acute chikungunya after traveling to the Caribbean in particular, they added.

At follow-up, three patients without preexisting rheumatic disease met criteria for diffuse postchikungunya (pCHIK) musculoskeletal disorders. In addition, four patients with preexisting rheumatic disease reported an increase in symptom severity including worsening knee osteoarthritis in both knees (one patient) and increased joint involvement (three patients).

Significantly more patients with preexisting disease reported using pain medication, compared with those without preexisting disease. However, no significant differences appeared in the percentage of patients in each group reporting other symptoms including joint pain, muscle pain, and joint swelling.

Nearly all the patients presented for acute care with fever (99%), joint pain (89%), myalgia (70%), and joint swelling (68%). The median pain level was 8 on a scale of 1-10.

Other symptoms reported at the time of acute diagnosis included gastrointestinal problems (59%), headache (48%), and rash (48%). Almost half the patients (46%) required inpatient care, with complications including hypotensive episodes, syncope, electrolyte imbalance, and thrombocytopenia.

“Patients seeking pretravel health care in preparation for a trip to the Caribbean – as to any other CHIK-endemic 185 region – need to be comprehensively counseled about the health risks related to the acute stage of the infection as well as related to the risk for developing a potentially long-lasting rheumatic disorder,” the researchers said.

“An integrated care plan for patients with acute CHIK consisting of follow-up appointments with the primary care provider and a rheumatologist with the aim of reducing the time to identify patients with pCHIK rheumatic disorders and initiation of optimal disease management may be useful and need further study,” they added.

The findings were limited by several factors including small sample size, use of self-reports, and narrow geographic range. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Approximately one-third of chikungunya patients who acquired the disease during Caribbean travel reported postchikungunya muscle pain, joint pain, and joint swelling, according to data for 28 patients seen at a single center in 2014. The findings were published in Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease (2016. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2016.01.009).

The researchers contacted 19 of the patients approximately 13 months after their original diagnoses. Of these, 37% described ongoing rheumatic problems; 32% reported joint pain, 32% reported joint swelling, and 26% reported muscle pain.

Dr. Cosmina Zeana of Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center, New York, and colleagues initially identified 28 adult patients with a median age of 52 years. Most were Hispanic (96%) and half were women (54%). The average length of stay in the Caribbean was 30 days, and 82% had visited the Dominican Republic. The follow-up data were collected via a telephone questionnaire.

Chikungunya has become endemic in Latin America, the researchers noted. “Of increasing concern is the occurrence of persistent rheumatic and general disabling symptoms that can last for several years following acute infection,” they wrote. Transmission of chikungunya has been documented throughout the Caribbean, but this study is the first known assessment of postchikungunya rheumatologic disorders among individuals diagnosed with acute chikungunya after traveling to the Caribbean in particular, they added.

At follow-up, three patients without preexisting rheumatic disease met criteria for diffuse postchikungunya (pCHIK) musculoskeletal disorders. In addition, four patients with preexisting rheumatic disease reported an increase in symptom severity including worsening knee osteoarthritis in both knees (one patient) and increased joint involvement (three patients).

Significantly more patients with preexisting disease reported using pain medication, compared with those without preexisting disease. However, no significant differences appeared in the percentage of patients in each group reporting other symptoms including joint pain, muscle pain, and joint swelling.

Nearly all the patients presented for acute care with fever (99%), joint pain (89%), myalgia (70%), and joint swelling (68%). The median pain level was 8 on a scale of 1-10.

Other symptoms reported at the time of acute diagnosis included gastrointestinal problems (59%), headache (48%), and rash (48%). Almost half the patients (46%) required inpatient care, with complications including hypotensive episodes, syncope, electrolyte imbalance, and thrombocytopenia.

“Patients seeking pretravel health care in preparation for a trip to the Caribbean – as to any other CHIK-endemic 185 region – need to be comprehensively counseled about the health risks related to the acute stage of the infection as well as related to the risk for developing a potentially long-lasting rheumatic disorder,” the researchers said.

“An integrated care plan for patients with acute CHIK consisting of follow-up appointments with the primary care provider and a rheumatologist with the aim of reducing the time to identify patients with pCHIK rheumatic disorders and initiation of optimal disease management may be useful and need further study,” they added.

The findings were limited by several factors including small sample size, use of self-reports, and narrow geographic range. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM TRAVEL MEDICINE AND INFECTIOUS DISEASE

Key clinical point: Individuals traveling to the Caribbean should be counseled about the possible acute and long-term health risks associated with chikungunya infections.

Major finding: Approximately 37% of Caribbean travelers who developed chikungunya infections reported ongoing rheumatic problems an average of 13 months later.

Data source: Data from 28 adults treated for acute chikungunya infection at a single center.

Disclosures: The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Zika virus found in amniotic fluid

A case study conducted in Brazil revealed the presence of Zika virus in the amniotic fluid of two pregnant women, suggesting that the virus can cross the placental barrier and potentially infect the developing fetus.

Both women in the study had their amniotic fluid samples taken at 28 weeks, and later gave birth to babies with microcephaly.

The finding, published online Feb 17 in The Lancet Infectious Diseases (Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Feb 17. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[16]00095-5), does not prove that Zika virus infection causes microcephaly but does suggest the biological plausibility of such a link.

In the same study, the researchers, led by Dr. Ana de Filippis of Oswaldo Cruz Institute in Rio de Janeiro, applied reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and viral metagenomic sequencing to the viral samples, allowing them to establish that the virus was very closely related to the Zika virus that caused an outbreak in French Polynesia in 2013, and was not a recombinant strain.

The women in the study, age 27 and 35, were from the Brazilian state of Paraíba. Neither woman reported smoking, using recreational drugs or alcohol, or taking medications known to affect fetal development.

Zika virus was not found in the blood or urine of either woman when the amniotic samples were taken, though both had reported earlier symptoms consistent with Zika infection. Other infections, including HIV, dengue, chikungunya, rubella, and herpes viruses, were ruled out.

The results provide important insight into the origin of the Zika virus circulating in Brazil, the researchers wrote in their analysis. Moreover, “our group is the first, to our knowledge, to isolate the whole genome of Zika virus directly from the amniotic fluid of a pregnant woman before delivery, supporting the hypothesis that Zika virus infection could occur through transplacental transmission,” wrote Dr. de Filippis and her colleagues.

Still, little is known about the effects of Zika on the developing central nervous system, the researchers wrote. A connection between Zika virus infections and poor CNS outcomes “remains presumptive, and is based on a temporal association. New studies should be done to investigate whether the Zika virus can infect either neurological precursor cells or final differentiated cells.”

The researchers cautioned that congenital microcephaly has been associated with genetic disorders, chemical exposures, brain injury and uterine infections. Other possible contributors to the current high rate of microcephaly in Brazil, which last year was 20 times higher than in previous years, need to be investigated, they wrote.

Agencies within Brazil’s national government and the city of Rio de Janeiro funded the study, and investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

The temporal association between Zika virus outbreaks and microcephaly in Brazil strongly suggests that Zika virus infection during pregnancy might cause severe neurological damage in neonates. The challenge now is to provide empirical evidence for the link between Zika virus and microcephaly, and the demonstration that Zika virus can cross the placental barrier and infect the neonate strongly favors this association.

Even if all these data strongly suggest that Zika virus can cause microcephaly, the number of microcephaly cases related to Zika virus is still unknown. The next step will be to do case-control studies to estimate the potential risk of microcephaly after Zika virus infection during pregnancy, other fetal or neonatal complications, and long-term outcomes for infected symptomatic and asymptomatic neonates.

These comments were adapted from commentary by Dr. Didier Musso, Institut Louis Malardé, Tahiti, French Polynesia, and Dr. David Baud, University of Lausanne and University Hospital, Lausanne, Switzerland (Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Feb 17. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[16]0096-7). Dr. Musso and Dr. Baud reported no conflicts of interest.

The temporal association between Zika virus outbreaks and microcephaly in Brazil strongly suggests that Zika virus infection during pregnancy might cause severe neurological damage in neonates. The challenge now is to provide empirical evidence for the link between Zika virus and microcephaly, and the demonstration that Zika virus can cross the placental barrier and infect the neonate strongly favors this association.

Even if all these data strongly suggest that Zika virus can cause microcephaly, the number of microcephaly cases related to Zika virus is still unknown. The next step will be to do case-control studies to estimate the potential risk of microcephaly after Zika virus infection during pregnancy, other fetal or neonatal complications, and long-term outcomes for infected symptomatic and asymptomatic neonates.

These comments were adapted from commentary by Dr. Didier Musso, Institut Louis Malardé, Tahiti, French Polynesia, and Dr. David Baud, University of Lausanne and University Hospital, Lausanne, Switzerland (Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Feb 17. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[16]0096-7). Dr. Musso and Dr. Baud reported no conflicts of interest.

The temporal association between Zika virus outbreaks and microcephaly in Brazil strongly suggests that Zika virus infection during pregnancy might cause severe neurological damage in neonates. The challenge now is to provide empirical evidence for the link between Zika virus and microcephaly, and the demonstration that Zika virus can cross the placental barrier and infect the neonate strongly favors this association.

Even if all these data strongly suggest that Zika virus can cause microcephaly, the number of microcephaly cases related to Zika virus is still unknown. The next step will be to do case-control studies to estimate the potential risk of microcephaly after Zika virus infection during pregnancy, other fetal or neonatal complications, and long-term outcomes for infected symptomatic and asymptomatic neonates.

These comments were adapted from commentary by Dr. Didier Musso, Institut Louis Malardé, Tahiti, French Polynesia, and Dr. David Baud, University of Lausanne and University Hospital, Lausanne, Switzerland (Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Feb 17. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[16]0096-7). Dr. Musso and Dr. Baud reported no conflicts of interest.

A case study conducted in Brazil revealed the presence of Zika virus in the amniotic fluid of two pregnant women, suggesting that the virus can cross the placental barrier and potentially infect the developing fetus.

Both women in the study had their amniotic fluid samples taken at 28 weeks, and later gave birth to babies with microcephaly.

The finding, published online Feb 17 in The Lancet Infectious Diseases (Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Feb 17. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[16]00095-5), does not prove that Zika virus infection causes microcephaly but does suggest the biological plausibility of such a link.

In the same study, the researchers, led by Dr. Ana de Filippis of Oswaldo Cruz Institute in Rio de Janeiro, applied reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and viral metagenomic sequencing to the viral samples, allowing them to establish that the virus was very closely related to the Zika virus that caused an outbreak in French Polynesia in 2013, and was not a recombinant strain.

The women in the study, age 27 and 35, were from the Brazilian state of Paraíba. Neither woman reported smoking, using recreational drugs or alcohol, or taking medications known to affect fetal development.

Zika virus was not found in the blood or urine of either woman when the amniotic samples were taken, though both had reported earlier symptoms consistent with Zika infection. Other infections, including HIV, dengue, chikungunya, rubella, and herpes viruses, were ruled out.

The results provide important insight into the origin of the Zika virus circulating in Brazil, the researchers wrote in their analysis. Moreover, “our group is the first, to our knowledge, to isolate the whole genome of Zika virus directly from the amniotic fluid of a pregnant woman before delivery, supporting the hypothesis that Zika virus infection could occur through transplacental transmission,” wrote Dr. de Filippis and her colleagues.

Still, little is known about the effects of Zika on the developing central nervous system, the researchers wrote. A connection between Zika virus infections and poor CNS outcomes “remains presumptive, and is based on a temporal association. New studies should be done to investigate whether the Zika virus can infect either neurological precursor cells or final differentiated cells.”

The researchers cautioned that congenital microcephaly has been associated with genetic disorders, chemical exposures, brain injury and uterine infections. Other possible contributors to the current high rate of microcephaly in Brazil, which last year was 20 times higher than in previous years, need to be investigated, they wrote.

Agencies within Brazil’s national government and the city of Rio de Janeiro funded the study, and investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

A case study conducted in Brazil revealed the presence of Zika virus in the amniotic fluid of two pregnant women, suggesting that the virus can cross the placental barrier and potentially infect the developing fetus.

Both women in the study had their amniotic fluid samples taken at 28 weeks, and later gave birth to babies with microcephaly.

The finding, published online Feb 17 in The Lancet Infectious Diseases (Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Feb 17. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[16]00095-5), does not prove that Zika virus infection causes microcephaly but does suggest the biological plausibility of such a link.

In the same study, the researchers, led by Dr. Ana de Filippis of Oswaldo Cruz Institute in Rio de Janeiro, applied reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and viral metagenomic sequencing to the viral samples, allowing them to establish that the virus was very closely related to the Zika virus that caused an outbreak in French Polynesia in 2013, and was not a recombinant strain.

The women in the study, age 27 and 35, were from the Brazilian state of Paraíba. Neither woman reported smoking, using recreational drugs or alcohol, or taking medications known to affect fetal development.

Zika virus was not found in the blood or urine of either woman when the amniotic samples were taken, though both had reported earlier symptoms consistent with Zika infection. Other infections, including HIV, dengue, chikungunya, rubella, and herpes viruses, were ruled out.

The results provide important insight into the origin of the Zika virus circulating in Brazil, the researchers wrote in their analysis. Moreover, “our group is the first, to our knowledge, to isolate the whole genome of Zika virus directly from the amniotic fluid of a pregnant woman before delivery, supporting the hypothesis that Zika virus infection could occur through transplacental transmission,” wrote Dr. de Filippis and her colleagues.

Still, little is known about the effects of Zika on the developing central nervous system, the researchers wrote. A connection between Zika virus infections and poor CNS outcomes “remains presumptive, and is based on a temporal association. New studies should be done to investigate whether the Zika virus can infect either neurological precursor cells or final differentiated cells.”

The researchers cautioned that congenital microcephaly has been associated with genetic disorders, chemical exposures, brain injury and uterine infections. Other possible contributors to the current high rate of microcephaly in Brazil, which last year was 20 times higher than in previous years, need to be investigated, they wrote.

Agencies within Brazil’s national government and the city of Rio de Janeiro funded the study, and investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

FROM THE LANCET INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Key clinical point: Zika virus can cross the placental barrier in pregnant women and potentially infect a fetus.

Major finding: Genetic sequencing showed virus detected in amniotic fluid corresponded 97%-100% with the strain that caused a 2013 outbreak in French Polynesia.

Data source: A case study of two women in the same region of Brazil, using amniotic samples from 28 weeks’ gestation in which Zika virus was detected and sequenced.

Disclosures: Two government agencies in Brazil sponsored the study, and investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

CDC: Zika virus expected to spread through Puerto Rico

Updated Zika virus figures from the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico show that more than two dozen locally acquired cases have occurred since December 2015, and more can be expected, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In a Feb. 12 report published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, CDC officials said, “Because the most common mosquito vector of Zika virus, Aedes aegypti, is present throughout Puerto Rico, Zika virus is expected to continue to spread throughout the island.”

During the period of Nov. 23, 2015, to Jan. 28, 2016, the Puerto Rico Department of Health (PRDH) reported a total of 30 laboratory-confirmed cases of Zika virus. The first locally acquired case of Zika virus in Puerto Rico was reported on Dec. 31, 2015, in a patient from the southeastern region (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Feb;65[early release]:1-6. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6506e2er.).

The PRDH is using passive and enhanced surveillance to track the spread of the mosquito-borne Flavivirus, a disease that in humans has a generally benign course but that has a suspected association with microcephaly in infants born to Zika-infected mothers. Investigators are also tracking a suspected association with Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Patients, who mainly resided in metropolitan San Juan or areas of eastern Puerto Rico, had mostly mild illness. Patients most frequently experienced rash (77%), myalgia (77%), arthralgia (73%), and fever (73%). Three patients were hospitalized.

One case of Guillain-Barré syndrome in a Zika-infected individual was reported to the PRDH, but the department saw no cases of microcephaly that were suspected of being associated with Zika virus.

The CDC is coordinating with the PRDH in ongoing surveillance efforts and response to the Zika virus. All clinicians in Puerto Rico are urged to report cases of Guillain-Barré syndrome, microcephaly, and suspected Zika infection to the PRDH. Residents of Puerto Rico should use strict mosquito avoidance and bite prevention measures, including the use of window screens, protective clothing, and an effective insect repellent.

On Twitter @karioakes

Updated Zika virus figures from the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico show that more than two dozen locally acquired cases have occurred since December 2015, and more can be expected, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In a Feb. 12 report published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, CDC officials said, “Because the most common mosquito vector of Zika virus, Aedes aegypti, is present throughout Puerto Rico, Zika virus is expected to continue to spread throughout the island.”

During the period of Nov. 23, 2015, to Jan. 28, 2016, the Puerto Rico Department of Health (PRDH) reported a total of 30 laboratory-confirmed cases of Zika virus. The first locally acquired case of Zika virus in Puerto Rico was reported on Dec. 31, 2015, in a patient from the southeastern region (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Feb;65[early release]:1-6. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6506e2er.).

The PRDH is using passive and enhanced surveillance to track the spread of the mosquito-borne Flavivirus, a disease that in humans has a generally benign course but that has a suspected association with microcephaly in infants born to Zika-infected mothers. Investigators are also tracking a suspected association with Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Patients, who mainly resided in metropolitan San Juan or areas of eastern Puerto Rico, had mostly mild illness. Patients most frequently experienced rash (77%), myalgia (77%), arthralgia (73%), and fever (73%). Three patients were hospitalized.

One case of Guillain-Barré syndrome in a Zika-infected individual was reported to the PRDH, but the department saw no cases of microcephaly that were suspected of being associated with Zika virus.

The CDC is coordinating with the PRDH in ongoing surveillance efforts and response to the Zika virus. All clinicians in Puerto Rico are urged to report cases of Guillain-Barré syndrome, microcephaly, and suspected Zika infection to the PRDH. Residents of Puerto Rico should use strict mosquito avoidance and bite prevention measures, including the use of window screens, protective clothing, and an effective insect repellent.

On Twitter @karioakes

Updated Zika virus figures from the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico show that more than two dozen locally acquired cases have occurred since December 2015, and more can be expected, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In a Feb. 12 report published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, CDC officials said, “Because the most common mosquito vector of Zika virus, Aedes aegypti, is present throughout Puerto Rico, Zika virus is expected to continue to spread throughout the island.”

During the period of Nov. 23, 2015, to Jan. 28, 2016, the Puerto Rico Department of Health (PRDH) reported a total of 30 laboratory-confirmed cases of Zika virus. The first locally acquired case of Zika virus in Puerto Rico was reported on Dec. 31, 2015, in a patient from the southeastern region (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Feb;65[early release]:1-6. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6506e2er.).

The PRDH is using passive and enhanced surveillance to track the spread of the mosquito-borne Flavivirus, a disease that in humans has a generally benign course but that has a suspected association with microcephaly in infants born to Zika-infected mothers. Investigators are also tracking a suspected association with Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Patients, who mainly resided in metropolitan San Juan or areas of eastern Puerto Rico, had mostly mild illness. Patients most frequently experienced rash (77%), myalgia (77%), arthralgia (73%), and fever (73%). Three patients were hospitalized.

One case of Guillain-Barré syndrome in a Zika-infected individual was reported to the PRDH, but the department saw no cases of microcephaly that were suspected of being associated with Zika virus.

The CDC is coordinating with the PRDH in ongoing surveillance efforts and response to the Zika virus. All clinicians in Puerto Rico are urged to report cases of Guillain-Barré syndrome, microcephaly, and suspected Zika infection to the PRDH. Residents of Puerto Rico should use strict mosquito avoidance and bite prevention measures, including the use of window screens, protective clothing, and an effective insect repellent.

On Twitter @karioakes

FROM MMWR

Dermatologic features may help distinguish Zika infection

Dermatologists may be seeing patients who have recently traveled to an area affected by the current Zika outbreaks, who present with a rash and possibly a fever.

Before serology and possibly virology confirms the diagnosis, there are certain distinguishing characteristics that may help distinguish Zika initially from dengue and Chikungunya, according to Dr. Stephen K. Tyring.

Dr. Tyring, clinical professor of dermatology at the University of Texas, Houston, said in an interview that serology is required to confirm the diagnosis, and should be obtained via state and local health departments, which are increasingly being provided with test kits. Virology via polymerase chain reaction also may be needed to diagnose the infection.

About 20% of people infected with Zika virus develop symptoms. In Texas, by early February, 10 cases had been diagnosed statewide.

The Zika rash is characterized by blanchable macules and papules, which may start on the face or trunk 3-5 days after the febrile phase, and become more diffuse, said Dr. Tyring.

The erythematous macules with areas of sparing is similar to the rash seen with Chikungunya and dengue, two other viral infections that have cutaneous manifestations. With a Zika rash, macules are more likely than papules, but papules are certainly possible, he said.

In addition, someone with a Zika infection is more likely to have conjunctivitis than someone with dengue or Chikungunya, and may have red sclera, he noted. But all the other symptoms associated with dengue and Chikungunya, such as the arthralgias, headaches, and myalgias, could certainly be present with Zika as well, as the three diseases have similar clinical features.

Dr. Tyring referred to a study published in 2009 describing 31 cases in a 2007 Zika outbreak in Micronesia, which reported that 90% (28 patients) had a macular or papular rash. In addition, 20 (65%) had a mild fever, 20 (65%) had arthralgia of the small joints, and 17 (55%) had nonpurulent conjunctivitis (N Engl J Med. 2009 Jun 11;360[24]:2536-43).

In September, when Dr. Tyring was attending the Brazilian Society of Dermatology meeting in Sao Paolo, he visited some clinics and saw some of the first patients diagnosed with Zika virus – before the connection with the microcephaly or Guillain-Barre had been made. Serologic testing had confirmed that the cases were Zika infections, not Chikungunya or dengue.

At that time, cases were being viewed as a mild versions of Chikungunya or dengue, “in other words, nothing that they were fearing any more than all the other arboviruses that are so common,” Dr. Tyring said in an interview.

With some of the patients, “we saw a bit of desquamation of the extremities, such as the fingertips,” he said. (See photos.) “But generally, it’s not very distinguishable between dengue and Chikungunya.”

Health care providers are encourage to report suspected cases to their state health departments.

Dermatologists may be seeing patients who have recently traveled to an area affected by the current Zika outbreaks, who present with a rash and possibly a fever.

Before serology and possibly virology confirms the diagnosis, there are certain distinguishing characteristics that may help distinguish Zika initially from dengue and Chikungunya, according to Dr. Stephen K. Tyring.

Dr. Tyring, clinical professor of dermatology at the University of Texas, Houston, said in an interview that serology is required to confirm the diagnosis, and should be obtained via state and local health departments, which are increasingly being provided with test kits. Virology via polymerase chain reaction also may be needed to diagnose the infection.

About 20% of people infected with Zika virus develop symptoms. In Texas, by early February, 10 cases had been diagnosed statewide.

The Zika rash is characterized by blanchable macules and papules, which may start on the face or trunk 3-5 days after the febrile phase, and become more diffuse, said Dr. Tyring.

The erythematous macules with areas of sparing is similar to the rash seen with Chikungunya and dengue, two other viral infections that have cutaneous manifestations. With a Zika rash, macules are more likely than papules, but papules are certainly possible, he said.

In addition, someone with a Zika infection is more likely to have conjunctivitis than someone with dengue or Chikungunya, and may have red sclera, he noted. But all the other symptoms associated with dengue and Chikungunya, such as the arthralgias, headaches, and myalgias, could certainly be present with Zika as well, as the three diseases have similar clinical features.

Dr. Tyring referred to a study published in 2009 describing 31 cases in a 2007 Zika outbreak in Micronesia, which reported that 90% (28 patients) had a macular or papular rash. In addition, 20 (65%) had a mild fever, 20 (65%) had arthralgia of the small joints, and 17 (55%) had nonpurulent conjunctivitis (N Engl J Med. 2009 Jun 11;360[24]:2536-43).

In September, when Dr. Tyring was attending the Brazilian Society of Dermatology meeting in Sao Paolo, he visited some clinics and saw some of the first patients diagnosed with Zika virus – before the connection with the microcephaly or Guillain-Barre had been made. Serologic testing had confirmed that the cases were Zika infections, not Chikungunya or dengue.

At that time, cases were being viewed as a mild versions of Chikungunya or dengue, “in other words, nothing that they were fearing any more than all the other arboviruses that are so common,” Dr. Tyring said in an interview.

With some of the patients, “we saw a bit of desquamation of the extremities, such as the fingertips,” he said. (See photos.) “But generally, it’s not very distinguishable between dengue and Chikungunya.”

Health care providers are encourage to report suspected cases to their state health departments.

Dermatologists may be seeing patients who have recently traveled to an area affected by the current Zika outbreaks, who present with a rash and possibly a fever.

Before serology and possibly virology confirms the diagnosis, there are certain distinguishing characteristics that may help distinguish Zika initially from dengue and Chikungunya, according to Dr. Stephen K. Tyring.

Dr. Tyring, clinical professor of dermatology at the University of Texas, Houston, said in an interview that serology is required to confirm the diagnosis, and should be obtained via state and local health departments, which are increasingly being provided with test kits. Virology via polymerase chain reaction also may be needed to diagnose the infection.

About 20% of people infected with Zika virus develop symptoms. In Texas, by early February, 10 cases had been diagnosed statewide.

The Zika rash is characterized by blanchable macules and papules, which may start on the face or trunk 3-5 days after the febrile phase, and become more diffuse, said Dr. Tyring.

The erythematous macules with areas of sparing is similar to the rash seen with Chikungunya and dengue, two other viral infections that have cutaneous manifestations. With a Zika rash, macules are more likely than papules, but papules are certainly possible, he said.

In addition, someone with a Zika infection is more likely to have conjunctivitis than someone with dengue or Chikungunya, and may have red sclera, he noted. But all the other symptoms associated with dengue and Chikungunya, such as the arthralgias, headaches, and myalgias, could certainly be present with Zika as well, as the three diseases have similar clinical features.

Dr. Tyring referred to a study published in 2009 describing 31 cases in a 2007 Zika outbreak in Micronesia, which reported that 90% (28 patients) had a macular or papular rash. In addition, 20 (65%) had a mild fever, 20 (65%) had arthralgia of the small joints, and 17 (55%) had nonpurulent conjunctivitis (N Engl J Med. 2009 Jun 11;360[24]:2536-43).

In September, when Dr. Tyring was attending the Brazilian Society of Dermatology meeting in Sao Paolo, he visited some clinics and saw some of the first patients diagnosed with Zika virus – before the connection with the microcephaly or Guillain-Barre had been made. Serologic testing had confirmed that the cases were Zika infections, not Chikungunya or dengue.

At that time, cases were being viewed as a mild versions of Chikungunya or dengue, “in other words, nothing that they were fearing any more than all the other arboviruses that are so common,” Dr. Tyring said in an interview.

With some of the patients, “we saw a bit of desquamation of the extremities, such as the fingertips,” he said. (See photos.) “But generally, it’s not very distinguishable between dengue and Chikungunya.”

Health care providers are encourage to report suspected cases to their state health departments.

Borrelia mayonii is new cause of Lyme disease variant

A new species of Borrelia has been linked to a variant of Lyme disease with symptoms that differ somewhat from typical Lyme borreliosis.

Of 100,545 routine clinical specimens tested at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., for Lyme borreliosis between 2003 and 2014, six clinical specimens – all from 2012 or later – yielded an atypical oppA1 PCR result, according to a study published in Lancet Infectious Diseases.

In patients with specimens yielding atypical results, medical records were reviewed and additional samples were examined by a research team led by Dr. Bobbi Pritt of Mayo Clinic.

The researchers performed DNA sequencing, microscopy, or culturing of the diagnostic specimens (five blood and one synovial), as well as oppA1 PCR testing of Ixodes scapularis ticks (black-legged or “deer” ticks) from regions of suspected patient tick exposure. Among the five blood specimens tested, the median oppA1 copy number was 180 times higher than that found in 13 specimens testing positive for B. burgdorferi during the same time period.

Multigene sequencing identified the spirochete as a novel B. burgdorferi genospecies – the same genospecies detected in ticks collected at a probable patient exposure site.

The newly discovered bacteria, provisionally named Borrelia mayonii, caused Lyme disease with symptoms similar to those caused by B. burgdorferi, but with some distinct clinical features. Similar to classic Lyme disease, fever, headache, rash, and neck pain were experienced in the early stages of infection (days after exposure) and arthritis in the later stages (weeks after exposure). But patients infected with B. mayonii also presented with nausea and vomiting, diffuse rashes (as opposed to the typical “bull’s-eye” rash), and a higher concentration of bacteria in the blood.

“In view of the differing clinical manifestations for patients infected with the novel B. burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies, it is likely that Lyme borreliosis is not being considered – and therefore not diagnosed – in some patients with this infection,” said Dr. Pritt and her colleagues. They added that the clinical range of illness must be better defined in additional patients to ensure the infection is recognized and distinguished from other tick-borne infections, and oppA1 PCR is used for diagnosing infection with B. mayonii.

Read the full study in Lancet Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[15]00464-8).

On Twitter @richpizzi

A new species of Borrelia has been linked to a variant of Lyme disease with symptoms that differ somewhat from typical Lyme borreliosis.

Of 100,545 routine clinical specimens tested at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., for Lyme borreliosis between 2003 and 2014, six clinical specimens – all from 2012 or later – yielded an atypical oppA1 PCR result, according to a study published in Lancet Infectious Diseases.

In patients with specimens yielding atypical results, medical records were reviewed and additional samples were examined by a research team led by Dr. Bobbi Pritt of Mayo Clinic.

The researchers performed DNA sequencing, microscopy, or culturing of the diagnostic specimens (five blood and one synovial), as well as oppA1 PCR testing of Ixodes scapularis ticks (black-legged or “deer” ticks) from regions of suspected patient tick exposure. Among the five blood specimens tested, the median oppA1 copy number was 180 times higher than that found in 13 specimens testing positive for B. burgdorferi during the same time period.

Multigene sequencing identified the spirochete as a novel B. burgdorferi genospecies – the same genospecies detected in ticks collected at a probable patient exposure site.

The newly discovered bacteria, provisionally named Borrelia mayonii, caused Lyme disease with symptoms similar to those caused by B. burgdorferi, but with some distinct clinical features. Similar to classic Lyme disease, fever, headache, rash, and neck pain were experienced in the early stages of infection (days after exposure) and arthritis in the later stages (weeks after exposure). But patients infected with B. mayonii also presented with nausea and vomiting, diffuse rashes (as opposed to the typical “bull’s-eye” rash), and a higher concentration of bacteria in the blood.

“In view of the differing clinical manifestations for patients infected with the novel B. burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies, it is likely that Lyme borreliosis is not being considered – and therefore not diagnosed – in some patients with this infection,” said Dr. Pritt and her colleagues. They added that the clinical range of illness must be better defined in additional patients to ensure the infection is recognized and distinguished from other tick-borne infections, and oppA1 PCR is used for diagnosing infection with B. mayonii.

Read the full study in Lancet Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[15]00464-8).

On Twitter @richpizzi

A new species of Borrelia has been linked to a variant of Lyme disease with symptoms that differ somewhat from typical Lyme borreliosis.

Of 100,545 routine clinical specimens tested at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., for Lyme borreliosis between 2003 and 2014, six clinical specimens – all from 2012 or later – yielded an atypical oppA1 PCR result, according to a study published in Lancet Infectious Diseases.

In patients with specimens yielding atypical results, medical records were reviewed and additional samples were examined by a research team led by Dr. Bobbi Pritt of Mayo Clinic.

The researchers performed DNA sequencing, microscopy, or culturing of the diagnostic specimens (five blood and one synovial), as well as oppA1 PCR testing of Ixodes scapularis ticks (black-legged or “deer” ticks) from regions of suspected patient tick exposure. Among the five blood specimens tested, the median oppA1 copy number was 180 times higher than that found in 13 specimens testing positive for B. burgdorferi during the same time period.

Multigene sequencing identified the spirochete as a novel B. burgdorferi genospecies – the same genospecies detected in ticks collected at a probable patient exposure site.

The newly discovered bacteria, provisionally named Borrelia mayonii, caused Lyme disease with symptoms similar to those caused by B. burgdorferi, but with some distinct clinical features. Similar to classic Lyme disease, fever, headache, rash, and neck pain were experienced in the early stages of infection (days after exposure) and arthritis in the later stages (weeks after exposure). But patients infected with B. mayonii also presented with nausea and vomiting, diffuse rashes (as opposed to the typical “bull’s-eye” rash), and a higher concentration of bacteria in the blood.

“In view of the differing clinical manifestations for patients infected with the novel B. burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies, it is likely that Lyme borreliosis is not being considered – and therefore not diagnosed – in some patients with this infection,” said Dr. Pritt and her colleagues. They added that the clinical range of illness must be better defined in additional patients to ensure the infection is recognized and distinguished from other tick-borne infections, and oppA1 PCR is used for diagnosing infection with B. mayonii.

Read the full study in Lancet Infectious Diseases (doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099[15]00464-8).

On Twitter @richpizzi

FROM LANCET INFECTIOUS DISEASES

New evidence strengthens link between Zika and microcephaly

While scientists can’t say with certainty that congenital Zika virus is causing the massive spike in cases of microcephaly seen in Brazil, evidence of a strong association continues to mount.

Two reports, published Feb. 10 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report and in the New England Journal of Medicine, confirm through laboratory testing that fetuses and infants with microcephaly also were positive for Zika virus infection.

In the MMWR report, researchers from the United States and Brazil present evidence of a link between Zika virus infection and microcephaly and fetal demise through detection of viral RNA and antigens in brain tissues with infants with microcephaly, as well as placental tissues from early miscarriages.

The findings are based on laboratory testing of tissue samples from two newborns with microcephaly who died within 20 hours of birth and two miscarriages (at 11 and 13 weeks’ gestation). The samples were submitted to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from the state of Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil, in December 2015. All four mothers had clinical signs of Zika virus infection during the first trimester but did not have signs of active infection at the time of delivery or miscarriage.

Specimens from all four cases were positive by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing, and sequence analysis provided additional evidence of Zika virus infection (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Feb;65:1-2. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6506e1er).

“To better understand the pathogenesis of Zika virus infection and associated congenital anomalies and fetal death, it is necessary to evaluate autopsy and placental tissues from additional cases, and to determine the effect of gestational age during maternal illness on fetal outcomes,” the researchers wrote.

In the New England Journal of Medicine report, Dr. Jernej Mlakar of the University of Ljubljana, Slovenia, and colleagues, presented the case of a previously healthy 25-year-old pregnant woman who had become ill while living in Brazil. During the 13th week of gestation, she had a high fever, followed by severe musculoskeletal and retro-ocular pain, as well as an itchy generalized maculopapular rash. Zika virus was suspected at the time but virologic diagnostic testing was not performed.

Ultrasound at 14 weeks and 20 weeks showed normal fetal growth and anatomy, but ultrasound at 29 weeks showed signs of fetal abnormalities. At 32 weeks, physicians confirmed intrauterine growth retardation and microcephaly with calcifications in the fetal brain and placenta.

The woman requested termination of the pregnancy and an autopsy was performed on the fetus. Positive results for Zika virus were obtained on RT-PCR assay in the fetal brain sample. All autopsy samples were tested on PCR assay and found to be negative for other flaviviruses, including dengue, yellow fever, West Nile, and tick-borne encephalitis (N Engl J Med. 2016 Feb 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600651).

In an editorial accompanying the report, physicians from the Harvard School of Public Health and Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston, wrote that there are still many unanswered questions about Zika virus in pregnancy. Assuming the association between Zika virus and microcephaly exists, researchers do not know whether the timing of the infection during pregnancy has an effect on the risk of fetal abnormalities. Additionally, it’s unknown whether asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic disease poses a risk to the fetus (N Engl J Med. 2016 Feb 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1601862).

The researchers for both case reports had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @maryellenny

While scientists can’t say with certainty that congenital Zika virus is causing the massive spike in cases of microcephaly seen in Brazil, evidence of a strong association continues to mount.

Two reports, published Feb. 10 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report and in the New England Journal of Medicine, confirm through laboratory testing that fetuses and infants with microcephaly also were positive for Zika virus infection.

In the MMWR report, researchers from the United States and Brazil present evidence of a link between Zika virus infection and microcephaly and fetal demise through detection of viral RNA and antigens in brain tissues with infants with microcephaly, as well as placental tissues from early miscarriages.

The findings are based on laboratory testing of tissue samples from two newborns with microcephaly who died within 20 hours of birth and two miscarriages (at 11 and 13 weeks’ gestation). The samples were submitted to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from the state of Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil, in December 2015. All four mothers had clinical signs of Zika virus infection during the first trimester but did not have signs of active infection at the time of delivery or miscarriage.

Specimens from all four cases were positive by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing, and sequence analysis provided additional evidence of Zika virus infection (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Feb;65:1-2. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6506e1er).

“To better understand the pathogenesis of Zika virus infection and associated congenital anomalies and fetal death, it is necessary to evaluate autopsy and placental tissues from additional cases, and to determine the effect of gestational age during maternal illness on fetal outcomes,” the researchers wrote.

In the New England Journal of Medicine report, Dr. Jernej Mlakar of the University of Ljubljana, Slovenia, and colleagues, presented the case of a previously healthy 25-year-old pregnant woman who had become ill while living in Brazil. During the 13th week of gestation, she had a high fever, followed by severe musculoskeletal and retro-ocular pain, as well as an itchy generalized maculopapular rash. Zika virus was suspected at the time but virologic diagnostic testing was not performed.

Ultrasound at 14 weeks and 20 weeks showed normal fetal growth and anatomy, but ultrasound at 29 weeks showed signs of fetal abnormalities. At 32 weeks, physicians confirmed intrauterine growth retardation and microcephaly with calcifications in the fetal brain and placenta.

The woman requested termination of the pregnancy and an autopsy was performed on the fetus. Positive results for Zika virus were obtained on RT-PCR assay in the fetal brain sample. All autopsy samples were tested on PCR assay and found to be negative for other flaviviruses, including dengue, yellow fever, West Nile, and tick-borne encephalitis (N Engl J Med. 2016 Feb 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600651).

In an editorial accompanying the report, physicians from the Harvard School of Public Health and Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston, wrote that there are still many unanswered questions about Zika virus in pregnancy. Assuming the association between Zika virus and microcephaly exists, researchers do not know whether the timing of the infection during pregnancy has an effect on the risk of fetal abnormalities. Additionally, it’s unknown whether asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic disease poses a risk to the fetus (N Engl J Med. 2016 Feb 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1601862).

The researchers for both case reports had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @maryellenny

While scientists can’t say with certainty that congenital Zika virus is causing the massive spike in cases of microcephaly seen in Brazil, evidence of a strong association continues to mount.

Two reports, published Feb. 10 in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report and in the New England Journal of Medicine, confirm through laboratory testing that fetuses and infants with microcephaly also were positive for Zika virus infection.

In the MMWR report, researchers from the United States and Brazil present evidence of a link between Zika virus infection and microcephaly and fetal demise through detection of viral RNA and antigens in brain tissues with infants with microcephaly, as well as placental tissues from early miscarriages.

The findings are based on laboratory testing of tissue samples from two newborns with microcephaly who died within 20 hours of birth and two miscarriages (at 11 and 13 weeks’ gestation). The samples were submitted to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention from the state of Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil, in December 2015. All four mothers had clinical signs of Zika virus infection during the first trimester but did not have signs of active infection at the time of delivery or miscarriage.

Specimens from all four cases were positive by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing, and sequence analysis provided additional evidence of Zika virus infection (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Feb;65:1-2. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6506e1er).

“To better understand the pathogenesis of Zika virus infection and associated congenital anomalies and fetal death, it is necessary to evaluate autopsy and placental tissues from additional cases, and to determine the effect of gestational age during maternal illness on fetal outcomes,” the researchers wrote.

In the New England Journal of Medicine report, Dr. Jernej Mlakar of the University of Ljubljana, Slovenia, and colleagues, presented the case of a previously healthy 25-year-old pregnant woman who had become ill while living in Brazil. During the 13th week of gestation, she had a high fever, followed by severe musculoskeletal and retro-ocular pain, as well as an itchy generalized maculopapular rash. Zika virus was suspected at the time but virologic diagnostic testing was not performed.

Ultrasound at 14 weeks and 20 weeks showed normal fetal growth and anatomy, but ultrasound at 29 weeks showed signs of fetal abnormalities. At 32 weeks, physicians confirmed intrauterine growth retardation and microcephaly with calcifications in the fetal brain and placenta.

The woman requested termination of the pregnancy and an autopsy was performed on the fetus. Positive results for Zika virus were obtained on RT-PCR assay in the fetal brain sample. All autopsy samples were tested on PCR assay and found to be negative for other flaviviruses, including dengue, yellow fever, West Nile, and tick-borne encephalitis (N Engl J Med. 2016 Feb 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600651).

In an editorial accompanying the report, physicians from the Harvard School of Public Health and Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston, wrote that there are still many unanswered questions about Zika virus in pregnancy. Assuming the association between Zika virus and microcephaly exists, researchers do not know whether the timing of the infection during pregnancy has an effect on the risk of fetal abnormalities. Additionally, it’s unknown whether asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic disease poses a risk to the fetus (N Engl J Med. 2016 Feb 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1601862).

The researchers for both case reports had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @maryellenny

Ocular symptoms accompany microcephaly in Brazilian newborns

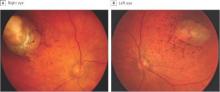

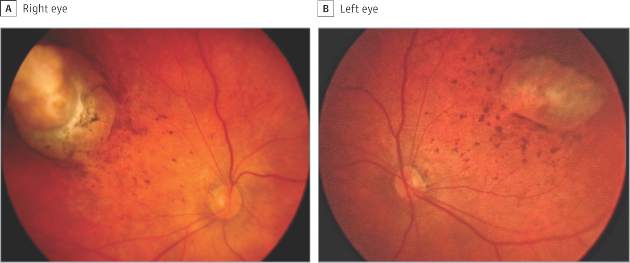

In a sample of infants born with microcephaly and a presumed diagnosis of congenital Zika virus, about one-third were found to have vision-threatening eye abnormalities, according to researchers working in a Zika hot spot in Brazil.

The group, led by Dr. Bruno de Paula Freitas of the Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, in Salvador, Brazil, evaluated 29 infants with microcephaly born at a single hospital in December following suspected maternal infection with the mosquito-borne Zika virus. In a paper published online Feb 9., Dr. de Paula Freitas and his colleagues reported eye abnormalities in 10 of these children (34.5%) (JAMA Ophthalmol. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.0267.).

Brazil first reported an outbreak of Zika virus infections in April 2015, followed months later by a spike in the number of infants born with microcephaly, a birth defect defined by a cephalic circumference of 32 cm or less in newborns. The most common ocular abnormalities seen in the cohort of affected infants were pigment mottling of the retina and chorioretinal atrophy (11 of 17 abnormal eyes); optic nerve abnormalities (8 eyes); and iris coloboma (affecting 2 eyes in one infant).

While a previous study of a Zika virus outbreak in Micronesia found conjunctivitis among infected individuals, none of the mothers of the current cohort of infants disclosed having had conjunctivitis. Altogether 23 of the mothers (79%) reported having had any symptoms of Zika virus infection during pregnancy.

Dr. de Paula Freitas and his colleagues acknowledged that their results were limited by a small sample size and single-site study design. However, the investigators noted, the findings suggest the possibility “that even oligosymptomatic or asymptomatic pregnant patients presumably infected [with Zika virus] may have microcephalic newborns with ophthalmoscopic lesions” and those newborns should be routinely evaluated for ocular symptoms.

An important question that requires further investigation, they noted, is whether newborns without microcephaly, but whose mothers may have been infected with the Zika virus, should be screened to identify possible ocular lesions.

Funding for the study came from Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, Federal University of São Paulo, Vision Institute, and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico in Brasília, Brazil. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

Ophthalmologic manifestations of congenital Zika virus infection are not yet well described. The report by de Paula Freitas et al. implicates this infection as the cause of chorioretinal scarring and possibly other ocular abnormalities in infants with microcephaly recently born in Brazil.

Microcephaly can be genetic, metabolic, drug related, or caused by perinatal insults such as hypoxia, malnutrition, or infection. The present 20-fold reported increase of microcephaly in parts of Brazil is temporally associated with the outbreak of Zika virus. However, this association is still presumptive because definitive serologic testing for Zika virus was not available in Brazil at the time of the outbreak, and confusion may occur with other causes of microcephaly. Similarly, the currently described eye lesions are presumptively associated with the virus.

Based on current information, in our opinion, clinicians in areas where Zika virus is present should perform ophthalmologic examinations on all microcephalic babies. Because it is still unclear whether the eye lesions occur in the absence of microcephaly, it is premature to suggest ophthalmic screening of all babies born in epidemic areas.

Dr. Lee M. Jampol and Dr. Debra A Goldstein are from the department of ophthalmology, Northwestern University, Chicago. These comments are excerpted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Ophthalmol. doi:10.1001/jamaopthalmol.2016.0284.). The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

Ophthalmologic manifestations of congenital Zika virus infection are not yet well described. The report by de Paula Freitas et al. implicates this infection as the cause of chorioretinal scarring and possibly other ocular abnormalities in infants with microcephaly recently born in Brazil.

Microcephaly can be genetic, metabolic, drug related, or caused by perinatal insults such as hypoxia, malnutrition, or infection. The present 20-fold reported increase of microcephaly in parts of Brazil is temporally associated with the outbreak of Zika virus. However, this association is still presumptive because definitive serologic testing for Zika virus was not available in Brazil at the time of the outbreak, and confusion may occur with other causes of microcephaly. Similarly, the currently described eye lesions are presumptively associated with the virus.

Based on current information, in our opinion, clinicians in areas where Zika virus is present should perform ophthalmologic examinations on all microcephalic babies. Because it is still unclear whether the eye lesions occur in the absence of microcephaly, it is premature to suggest ophthalmic screening of all babies born in epidemic areas.

Dr. Lee M. Jampol and Dr. Debra A Goldstein are from the department of ophthalmology, Northwestern University, Chicago. These comments are excerpted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Ophthalmol. doi:10.1001/jamaopthalmol.2016.0284.). The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

Ophthalmologic manifestations of congenital Zika virus infection are not yet well described. The report by de Paula Freitas et al. implicates this infection as the cause of chorioretinal scarring and possibly other ocular abnormalities in infants with microcephaly recently born in Brazil.

Microcephaly can be genetic, metabolic, drug related, or caused by perinatal insults such as hypoxia, malnutrition, or infection. The present 20-fold reported increase of microcephaly in parts of Brazil is temporally associated with the outbreak of Zika virus. However, this association is still presumptive because definitive serologic testing for Zika virus was not available in Brazil at the time of the outbreak, and confusion may occur with other causes of microcephaly. Similarly, the currently described eye lesions are presumptively associated with the virus.

Based on current information, in our opinion, clinicians in areas where Zika virus is present should perform ophthalmologic examinations on all microcephalic babies. Because it is still unclear whether the eye lesions occur in the absence of microcephaly, it is premature to suggest ophthalmic screening of all babies born in epidemic areas.

Dr. Lee M. Jampol and Dr. Debra A Goldstein are from the department of ophthalmology, Northwestern University, Chicago. These comments are excerpted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Ophthalmol. doi:10.1001/jamaopthalmol.2016.0284.). The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

In a sample of infants born with microcephaly and a presumed diagnosis of congenital Zika virus, about one-third were found to have vision-threatening eye abnormalities, according to researchers working in a Zika hot spot in Brazil.

The group, led by Dr. Bruno de Paula Freitas of the Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, in Salvador, Brazil, evaluated 29 infants with microcephaly born at a single hospital in December following suspected maternal infection with the mosquito-borne Zika virus. In a paper published online Feb 9., Dr. de Paula Freitas and his colleagues reported eye abnormalities in 10 of these children (34.5%) (JAMA Ophthalmol. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.0267.).

Brazil first reported an outbreak of Zika virus infections in April 2015, followed months later by a spike in the number of infants born with microcephaly, a birth defect defined by a cephalic circumference of 32 cm or less in newborns. The most common ocular abnormalities seen in the cohort of affected infants were pigment mottling of the retina and chorioretinal atrophy (11 of 17 abnormal eyes); optic nerve abnormalities (8 eyes); and iris coloboma (affecting 2 eyes in one infant).

While a previous study of a Zika virus outbreak in Micronesia found conjunctivitis among infected individuals, none of the mothers of the current cohort of infants disclosed having had conjunctivitis. Altogether 23 of the mothers (79%) reported having had any symptoms of Zika virus infection during pregnancy.

Dr. de Paula Freitas and his colleagues acknowledged that their results were limited by a small sample size and single-site study design. However, the investigators noted, the findings suggest the possibility “that even oligosymptomatic or asymptomatic pregnant patients presumably infected [with Zika virus] may have microcephalic newborns with ophthalmoscopic lesions” and those newborns should be routinely evaluated for ocular symptoms.

An important question that requires further investigation, they noted, is whether newborns without microcephaly, but whose mothers may have been infected with the Zika virus, should be screened to identify possible ocular lesions.

Funding for the study came from Hospital Geral Roberto Santos, Federal University of São Paulo, Vision Institute, and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico in Brasília, Brazil. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

In a sample of infants born with microcephaly and a presumed diagnosis of congenital Zika virus, about one-third were found to have vision-threatening eye abnormalities, according to researchers working in a Zika hot spot in Brazil.