User login

Trial of ofatumumab in FL stopped early

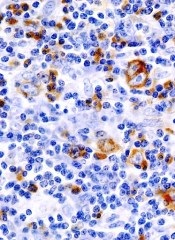

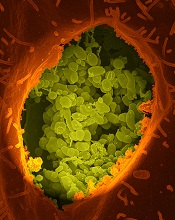

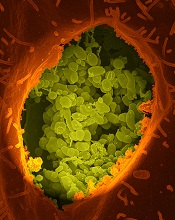

Photo courtesy of GSK

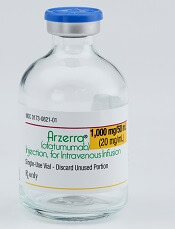

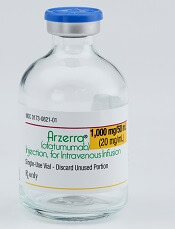

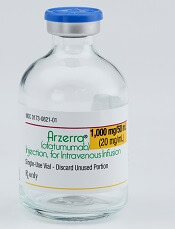

Genmab A/S said it is stopping a phase 3 trial of ofatumumab in follicular lymphoma (FL) after a planned interim analysis suggested the drug was unlikely to demonstrate superiority over rituximab.

The trial was designed to compare these 2 drugs as single-agent treatment in FL patients who had relapsed at least 6 months after completing treatment with a rituximab-containing regimen.

An interim analysis performed by an independent data monitoring committee indicated that, if the trial was to be completed as planned, it was unlikely that ofatumumab would improve progression-free survival (PFS) when compared to rituximab.

Genmab noted that this analysis did not reveal any new safety signals associated with ofatumumab, and no other ongoing trials of ofatumumab will be affected by the results of this analysis.

“The outcome of the interim analysis in this study is disappointing, as we had hoped to see superiority of ofatumumab,” said Jan van de Winkel, PhD, chief executive officer of Genmab. “The data from the study will now be prepared so that it can be presented at a future scientific conference.”

The goal of the study was to randomize up to 516 patients to receive ofatumumab (at 1000 mg) or rituximab (at 375 mg/m2) by intravenous infusion for 4 weekly doses.

Patients who had stable or responsive disease would then receive single infusions of ofatumumab or rituximab every 2 months for 4 additional doses—a total of 8 doses over 9 months. The primary endpoint of the study was PFS.

Past disappointments

This is not the first time ofatumumab has fallen short of expectations. Last year, the drug failed to meet the primary endpoint in two phase 3 trials.

In the OMB114242 trial, ofatumumab failed to improve PFS when compared to physicians’ choice in patients with bulky, fludarabine-refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

In the ORCHARRD trial, ofatumumab plus chemotherapy failed to improve PFS when compared to rituximab plus chemotherapy in patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

About ofatumumab

Ofatumumab is a human monoclonal antibody designed to target the CD20 molecule found on the surface of CLL cells and normal B lymphocytes.

In the US, ofatumumab is approved for use in combination with chlorambucil to treat previously untreated patients with CLL for whom fludarabine-based therapy is considered inappropriate.

In the European Union (EU), ofatumumab is approved for use in combination with chlorambucil or bendamustine to treat patients with CLL who have not received prior therapy and who are not eligible for fludarabine-based therapy.

In more than 50 countries worldwide, including the US and EU member countries, ofatumumab is approved as monotherapy for the treatment of patients with CLL who are refractory after prior treatment with fludarabine and alemtuzumab.

Ofatumumab is marketed as Arzerra under a collaboration agreement between Genmab and Novartis (formerly GSK). ![]()

Photo courtesy of GSK

Genmab A/S said it is stopping a phase 3 trial of ofatumumab in follicular lymphoma (FL) after a planned interim analysis suggested the drug was unlikely to demonstrate superiority over rituximab.

The trial was designed to compare these 2 drugs as single-agent treatment in FL patients who had relapsed at least 6 months after completing treatment with a rituximab-containing regimen.

An interim analysis performed by an independent data monitoring committee indicated that, if the trial was to be completed as planned, it was unlikely that ofatumumab would improve progression-free survival (PFS) when compared to rituximab.

Genmab noted that this analysis did not reveal any new safety signals associated with ofatumumab, and no other ongoing trials of ofatumumab will be affected by the results of this analysis.

“The outcome of the interim analysis in this study is disappointing, as we had hoped to see superiority of ofatumumab,” said Jan van de Winkel, PhD, chief executive officer of Genmab. “The data from the study will now be prepared so that it can be presented at a future scientific conference.”

The goal of the study was to randomize up to 516 patients to receive ofatumumab (at 1000 mg) or rituximab (at 375 mg/m2) by intravenous infusion for 4 weekly doses.

Patients who had stable or responsive disease would then receive single infusions of ofatumumab or rituximab every 2 months for 4 additional doses—a total of 8 doses over 9 months. The primary endpoint of the study was PFS.

Past disappointments

This is not the first time ofatumumab has fallen short of expectations. Last year, the drug failed to meet the primary endpoint in two phase 3 trials.

In the OMB114242 trial, ofatumumab failed to improve PFS when compared to physicians’ choice in patients with bulky, fludarabine-refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

In the ORCHARRD trial, ofatumumab plus chemotherapy failed to improve PFS when compared to rituximab plus chemotherapy in patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

About ofatumumab

Ofatumumab is a human monoclonal antibody designed to target the CD20 molecule found on the surface of CLL cells and normal B lymphocytes.

In the US, ofatumumab is approved for use in combination with chlorambucil to treat previously untreated patients with CLL for whom fludarabine-based therapy is considered inappropriate.

In the European Union (EU), ofatumumab is approved for use in combination with chlorambucil or bendamustine to treat patients with CLL who have not received prior therapy and who are not eligible for fludarabine-based therapy.

In more than 50 countries worldwide, including the US and EU member countries, ofatumumab is approved as monotherapy for the treatment of patients with CLL who are refractory after prior treatment with fludarabine and alemtuzumab.

Ofatumumab is marketed as Arzerra under a collaboration agreement between Genmab and Novartis (formerly GSK). ![]()

Photo courtesy of GSK

Genmab A/S said it is stopping a phase 3 trial of ofatumumab in follicular lymphoma (FL) after a planned interim analysis suggested the drug was unlikely to demonstrate superiority over rituximab.

The trial was designed to compare these 2 drugs as single-agent treatment in FL patients who had relapsed at least 6 months after completing treatment with a rituximab-containing regimen.

An interim analysis performed by an independent data monitoring committee indicated that, if the trial was to be completed as planned, it was unlikely that ofatumumab would improve progression-free survival (PFS) when compared to rituximab.

Genmab noted that this analysis did not reveal any new safety signals associated with ofatumumab, and no other ongoing trials of ofatumumab will be affected by the results of this analysis.

“The outcome of the interim analysis in this study is disappointing, as we had hoped to see superiority of ofatumumab,” said Jan van de Winkel, PhD, chief executive officer of Genmab. “The data from the study will now be prepared so that it can be presented at a future scientific conference.”

The goal of the study was to randomize up to 516 patients to receive ofatumumab (at 1000 mg) or rituximab (at 375 mg/m2) by intravenous infusion for 4 weekly doses.

Patients who had stable or responsive disease would then receive single infusions of ofatumumab or rituximab every 2 months for 4 additional doses—a total of 8 doses over 9 months. The primary endpoint of the study was PFS.

Past disappointments

This is not the first time ofatumumab has fallen short of expectations. Last year, the drug failed to meet the primary endpoint in two phase 3 trials.

In the OMB114242 trial, ofatumumab failed to improve PFS when compared to physicians’ choice in patients with bulky, fludarabine-refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

In the ORCHARRD trial, ofatumumab plus chemotherapy failed to improve PFS when compared to rituximab plus chemotherapy in patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

About ofatumumab

Ofatumumab is a human monoclonal antibody designed to target the CD20 molecule found on the surface of CLL cells and normal B lymphocytes.

In the US, ofatumumab is approved for use in combination with chlorambucil to treat previously untreated patients with CLL for whom fludarabine-based therapy is considered inappropriate.

In the European Union (EU), ofatumumab is approved for use in combination with chlorambucil or bendamustine to treat patients with CLL who have not received prior therapy and who are not eligible for fludarabine-based therapy.

In more than 50 countries worldwide, including the US and EU member countries, ofatumumab is approved as monotherapy for the treatment of patients with CLL who are refractory after prior treatment with fludarabine and alemtuzumab.

Ofatumumab is marketed as Arzerra under a collaboration agreement between Genmab and Novartis (formerly GSK). ![]()

Companies abuse orphan drug designation, team says

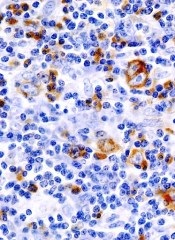

Photo by Steven Harbour

Health experts are calling on US lawmakers and regulators to “close loopholes” in the Orphan Drug Act.

The experts say the loopholes can provide pharmaceutical companies with millions of dollars in unintended subsidies and tax breaks and fuel skyrocketing medication costs.

They argue that companies are exploiting gaps in the law by claiming orphan status for drugs that end up being marketed for more common conditions.

“The industry has been gaming the system by slicing and dicing indications so that drugs qualify for lucrative orphan status benefits,” says Martin Makary, MD, of Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland.

“As a result, funding support intended for rare disease medicine is diverted to fund the development of blockbuster drugs.”

Dr Makary and his colleagues express this viewpoint in a commentary published in the American Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) grants orphan designation to encourage the development of drugs for diseases that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US. The Orphan Drug Act was enacted in 1983 to provide incentives for drug companies to develop treatments for so-called orphan diseases that would be unprofitable because of the limited market.

Dr Makary and his colleagues say the legislation has accomplished that mission and sparked the development of life-saving therapies for a range of rare disorders. However, the authors say the law has also invited abuse.

Under the terms of the act, companies can receive federal taxpayer subsidies of up to half a million dollars a year for up to 4 years per drug, large tax credits, and waivers of marketing application fees that can cost more than $2 million. In addition, the FDA can grant companies 7 years of marketing exclusivity for an orphan drug to ensure that companies recoup the costs of research and development.

Dr Makary says companies exploit the law by initially listing only a single indication for a drug’s use—one narrow enough to qualify for orphan disease benefits. After FDA approval, however, some such drugs are marketed and used off-label more broadly, thus turning large profits.

“This is a financially toxic practice that is also unethical,” says study author Michael Daniel, also of Johns Hopkins.

“It’s time to ensure that we also render it illegal. The practice inflates drug prices, and the costs are passed on to consumers in the form of higher health insurance premiums.”

For example, the drug rituximab was originally approved to treat follicular B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, a disease that affects about 14,000 patients a year. Now, rituximab is also used to treat several other types of cancer, organ rejection following kidney transplant, and autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, which affects 1.3 million Americans.

Rituximab, marketed under several trade names, is the top-selling medication approved as an orphan drug, the 12th all-time drug best-seller in the US, and it generated $3.7 billion in domestic sales in 2014.

In fact, 7 of the top 10 best-selling drugs in the US for 2014 came on the market with an orphan designation, according to Dr Makary and his colleagues.

Of the 41 drugs approved by the FDA in 2014, 18 had orphan status designations. The authors predict that, in 2015, orphan drugs will generate sales totaling $107 billion. And that number is expected to reach $176 billion by 2020.

Dr Makary says this projection represents a yearly growth rate of nearly 11%, or double the growth rate of the overall prescription drug market. The authors also cite data showing that, by 2020, orphan drugs are expected to account for 19% of global prescription drug sales, up from 6% in the year 2000.

Although the reasons for this boom in orphan drugs are likely multifactorial, the exploitation of the orphan drug act is an important catalyst behind this trend, the authors say.

Because orphan designation guarantees a 7-year exclusivity deal to market the drug and protects it from generic competition, the price tags for such medications often balloon rapidly.

For example, the drug imatinib was initially priced at $30,000 per year in 2001. By 2012, it cost $92,000 a year.

The drug’s original designation was for chronic myelogenous leukemia, and it would therefore treat 9000 patients a year in the US. Subsequently, imatinib was given 6 additional orphan designations for various conditions, including gastric cancers and immune disorders.

Dr Makary says, in essence, the exclusivity clause guarantees a hyperextended government-sponsored monopoly. So it’s not surprising that the median cost for orphan drugs is more than $98,000 per patient per year, compared with a median cost of just over $5000 per patient per year for drugs without orphan status.

Overall, nearly 15% of already approved orphan drugs subsequently add far more common diseases to their treatment repertoires.

Dr Makary and his colleagues recommend that, once a drug exceeds the basic tenets of the act—to treat fewer than 200,000 people—it should no longer receive government support or marketing exclusivity.

This can be achieved, the authors say, through pricing negotiations, clauses that reduce marketing exclusivity, and leveling of taxes once a medication becomes a blockbuster treatment for conditions not listed in the original FDA approval.

They say such measures would ensure the spirit of the original act is followed while continuing to provide critical economic incentives for truly rare diseases. ![]()

Photo by Steven Harbour

Health experts are calling on US lawmakers and regulators to “close loopholes” in the Orphan Drug Act.

The experts say the loopholes can provide pharmaceutical companies with millions of dollars in unintended subsidies and tax breaks and fuel skyrocketing medication costs.

They argue that companies are exploiting gaps in the law by claiming orphan status for drugs that end up being marketed for more common conditions.

“The industry has been gaming the system by slicing and dicing indications so that drugs qualify for lucrative orphan status benefits,” says Martin Makary, MD, of Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland.

“As a result, funding support intended for rare disease medicine is diverted to fund the development of blockbuster drugs.”

Dr Makary and his colleagues express this viewpoint in a commentary published in the American Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) grants orphan designation to encourage the development of drugs for diseases that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US. The Orphan Drug Act was enacted in 1983 to provide incentives for drug companies to develop treatments for so-called orphan diseases that would be unprofitable because of the limited market.

Dr Makary and his colleagues say the legislation has accomplished that mission and sparked the development of life-saving therapies for a range of rare disorders. However, the authors say the law has also invited abuse.

Under the terms of the act, companies can receive federal taxpayer subsidies of up to half a million dollars a year for up to 4 years per drug, large tax credits, and waivers of marketing application fees that can cost more than $2 million. In addition, the FDA can grant companies 7 years of marketing exclusivity for an orphan drug to ensure that companies recoup the costs of research and development.

Dr Makary says companies exploit the law by initially listing only a single indication for a drug’s use—one narrow enough to qualify for orphan disease benefits. After FDA approval, however, some such drugs are marketed and used off-label more broadly, thus turning large profits.

“This is a financially toxic practice that is also unethical,” says study author Michael Daniel, also of Johns Hopkins.

“It’s time to ensure that we also render it illegal. The practice inflates drug prices, and the costs are passed on to consumers in the form of higher health insurance premiums.”

For example, the drug rituximab was originally approved to treat follicular B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, a disease that affects about 14,000 patients a year. Now, rituximab is also used to treat several other types of cancer, organ rejection following kidney transplant, and autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, which affects 1.3 million Americans.

Rituximab, marketed under several trade names, is the top-selling medication approved as an orphan drug, the 12th all-time drug best-seller in the US, and it generated $3.7 billion in domestic sales in 2014.

In fact, 7 of the top 10 best-selling drugs in the US for 2014 came on the market with an orphan designation, according to Dr Makary and his colleagues.

Of the 41 drugs approved by the FDA in 2014, 18 had orphan status designations. The authors predict that, in 2015, orphan drugs will generate sales totaling $107 billion. And that number is expected to reach $176 billion by 2020.

Dr Makary says this projection represents a yearly growth rate of nearly 11%, or double the growth rate of the overall prescription drug market. The authors also cite data showing that, by 2020, orphan drugs are expected to account for 19% of global prescription drug sales, up from 6% in the year 2000.

Although the reasons for this boom in orphan drugs are likely multifactorial, the exploitation of the orphan drug act is an important catalyst behind this trend, the authors say.

Because orphan designation guarantees a 7-year exclusivity deal to market the drug and protects it from generic competition, the price tags for such medications often balloon rapidly.

For example, the drug imatinib was initially priced at $30,000 per year in 2001. By 2012, it cost $92,000 a year.

The drug’s original designation was for chronic myelogenous leukemia, and it would therefore treat 9000 patients a year in the US. Subsequently, imatinib was given 6 additional orphan designations for various conditions, including gastric cancers and immune disorders.

Dr Makary says, in essence, the exclusivity clause guarantees a hyperextended government-sponsored monopoly. So it’s not surprising that the median cost for orphan drugs is more than $98,000 per patient per year, compared with a median cost of just over $5000 per patient per year for drugs without orphan status.

Overall, nearly 15% of already approved orphan drugs subsequently add far more common diseases to their treatment repertoires.

Dr Makary and his colleagues recommend that, once a drug exceeds the basic tenets of the act—to treat fewer than 200,000 people—it should no longer receive government support or marketing exclusivity.

This can be achieved, the authors say, through pricing negotiations, clauses that reduce marketing exclusivity, and leveling of taxes once a medication becomes a blockbuster treatment for conditions not listed in the original FDA approval.

They say such measures would ensure the spirit of the original act is followed while continuing to provide critical economic incentives for truly rare diseases. ![]()

Photo by Steven Harbour

Health experts are calling on US lawmakers and regulators to “close loopholes” in the Orphan Drug Act.

The experts say the loopholes can provide pharmaceutical companies with millions of dollars in unintended subsidies and tax breaks and fuel skyrocketing medication costs.

They argue that companies are exploiting gaps in the law by claiming orphan status for drugs that end up being marketed for more common conditions.

“The industry has been gaming the system by slicing and dicing indications so that drugs qualify for lucrative orphan status benefits,” says Martin Makary, MD, of Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland.

“As a result, funding support intended for rare disease medicine is diverted to fund the development of blockbuster drugs.”

Dr Makary and his colleagues express this viewpoint in a commentary published in the American Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) grants orphan designation to encourage the development of drugs for diseases that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US. The Orphan Drug Act was enacted in 1983 to provide incentives for drug companies to develop treatments for so-called orphan diseases that would be unprofitable because of the limited market.

Dr Makary and his colleagues say the legislation has accomplished that mission and sparked the development of life-saving therapies for a range of rare disorders. However, the authors say the law has also invited abuse.

Under the terms of the act, companies can receive federal taxpayer subsidies of up to half a million dollars a year for up to 4 years per drug, large tax credits, and waivers of marketing application fees that can cost more than $2 million. In addition, the FDA can grant companies 7 years of marketing exclusivity for an orphan drug to ensure that companies recoup the costs of research and development.

Dr Makary says companies exploit the law by initially listing only a single indication for a drug’s use—one narrow enough to qualify for orphan disease benefits. After FDA approval, however, some such drugs are marketed and used off-label more broadly, thus turning large profits.

“This is a financially toxic practice that is also unethical,” says study author Michael Daniel, also of Johns Hopkins.

“It’s time to ensure that we also render it illegal. The practice inflates drug prices, and the costs are passed on to consumers in the form of higher health insurance premiums.”

For example, the drug rituximab was originally approved to treat follicular B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, a disease that affects about 14,000 patients a year. Now, rituximab is also used to treat several other types of cancer, organ rejection following kidney transplant, and autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, which affects 1.3 million Americans.

Rituximab, marketed under several trade names, is the top-selling medication approved as an orphan drug, the 12th all-time drug best-seller in the US, and it generated $3.7 billion in domestic sales in 2014.

In fact, 7 of the top 10 best-selling drugs in the US for 2014 came on the market with an orphan designation, according to Dr Makary and his colleagues.

Of the 41 drugs approved by the FDA in 2014, 18 had orphan status designations. The authors predict that, in 2015, orphan drugs will generate sales totaling $107 billion. And that number is expected to reach $176 billion by 2020.

Dr Makary says this projection represents a yearly growth rate of nearly 11%, or double the growth rate of the overall prescription drug market. The authors also cite data showing that, by 2020, orphan drugs are expected to account for 19% of global prescription drug sales, up from 6% in the year 2000.

Although the reasons for this boom in orphan drugs are likely multifactorial, the exploitation of the orphan drug act is an important catalyst behind this trend, the authors say.

Because orphan designation guarantees a 7-year exclusivity deal to market the drug and protects it from generic competition, the price tags for such medications often balloon rapidly.

For example, the drug imatinib was initially priced at $30,000 per year in 2001. By 2012, it cost $92,000 a year.

The drug’s original designation was for chronic myelogenous leukemia, and it would therefore treat 9000 patients a year in the US. Subsequently, imatinib was given 6 additional orphan designations for various conditions, including gastric cancers and immune disorders.

Dr Makary says, in essence, the exclusivity clause guarantees a hyperextended government-sponsored monopoly. So it’s not surprising that the median cost for orphan drugs is more than $98,000 per patient per year, compared with a median cost of just over $5000 per patient per year for drugs without orphan status.

Overall, nearly 15% of already approved orphan drugs subsequently add far more common diseases to their treatment repertoires.

Dr Makary and his colleagues recommend that, once a drug exceeds the basic tenets of the act—to treat fewer than 200,000 people—it should no longer receive government support or marketing exclusivity.

This can be achieved, the authors say, through pricing negotiations, clauses that reduce marketing exclusivity, and leveling of taxes once a medication becomes a blockbuster treatment for conditions not listed in the original FDA approval.

They say such measures would ensure the spirit of the original act is followed while continuing to provide critical economic incentives for truly rare diseases. ![]()

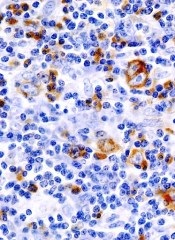

Inhibitor exhibits ‘modest’ activity in lymphoma

A small-molecule inhibitor has shown modest anticancer activity in a phase 1 trial of patients with relapsed/refractory lymphoma or multiple myeloma (MM), according to an investigator involved in the study.

A majority of patients who recieved the drug, pevonedistat, achieved stable disease, and a few patients with lymphoma experienced partial responses.

Investigators said pevonedistat could be given safely, although 100% of patients experienced adverse events (AEs), and a majority experienced grade 3 or higher AEs.

“The most important findings from our study are that pevonedistat hits its target in cancer cells in patients, can be given safely, and has modest activity in heavily pretreated patients with relapsed/refractory lymphoma, suggesting that we are on the right path,” said Jatin J. Shah, MD, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Dr Shah and his colleagues reported these findings in Clinical Cancer Research. The trial was sponsored by Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing pevonedistat.

Pevonedistat is a first-in-class, investigational, small-molecule inhibitor of the NEDD8-activating enzyme.

“This enzyme is part of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, which is the target of a number of FDA-approved anticancer therapeutics, including bortezomib . . . ,” Dr Shah explained. “Pevonedistat also alters the ability of cancer cells to repair damaged DNA.”

Patient and treatment characteristics

Dr Shah and his colleagues enrolled 44 patients on this trial. Seventeen patients had relapsed/refractory MM, and 27 had relapsed/refractory lymphoma.

The types of lymphoma were diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (n=10), follicular lymphoma (n=5), Hodgkin lymphoma (n=5), small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia (n=2), mantle cell lymphoma (n=1), lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (n=1), peripheral T-cell lymphoma (n=1), splenic marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (n=1), and “other” (n=1).

Twenty-seven patients received escalating doses of pevonedistat on schedule A, which was days 1, 2, 8, and 9 of a 21-day cycle, and 17 patients received escalating doses of the drug on schedule B, which was days 1, 4, 8, and 11 of a 21-day cycle.

Safety

The maximum tolerated doses were 110 mg/m2 and 196 mg/m2 on schedule A and B, respectively. The dose-limiting toxicities were febrile neutropenia, transaminase elevations, and muscle cramps on schedule A, and thrombocytopenia on schedule B.

On schedule A, 100% of patients experienced AEs, and 59% had AEs of grade 3 or higher. The grade 3 or higher AEs were anemia (19%), thrombocytopenia (4%), neutropenia (7%), fatigue (7%), ALT increase (4%), AST increase (7%), diarrhea (4%), pain (4%), dyspnea (4%), hypercalcemia (7%), hypophosphatemia (11%), hyperkalemia (4%), muscle spasms (4%), abdominal discomfort (4%), and pneumonia (4%).

On schedule B, 100% of patients experienced AEs, and 71% had grade 3 or higher AEs. The grade 3 or higher AEs were anemia (6%), thrombocytopenia (6%), neutropenia (12%), fatigue (6%), ALT increase (6%), pyrexia (6%), pain (6%), dyspnea (6%), hypophosphatemia (6%), muscle spasms (6%), upper respiratory tract infection (6%), dehydration (6%), hyperbilirubinemia (6%), and pneumonia (12%).

Efficacy

Three patients had a partial response to treatment, including 1 patient with relapsed nodular sclerosis Hodgkin lymphoma, 1 with relapsed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and 1 with relapsed peripheral T-cell lymphoma.

Another 30 patients, 17 with lymphoma and 13 with MM, had stable disease.

“Although pevonedistat had modest activity as a single-agent treatment, we expect greater activity when it is given in combination with standard therapy,” Dr Shah said.

“The pharmacodynamics data showed that pevonedistat hit its target in cancer cells in patients at low doses. This is important because it may mean that we do not need to escalate the dose in future trials to increase anticancer activity. This has the potential to increase the risk-benefit ratio of pevonedistat.”

Dr Shah said a limitation of this study is that it included a small number of patients, all of whom were very heavily pretreated, which may limit assessment of how active pevonedistat could be. ![]()

A small-molecule inhibitor has shown modest anticancer activity in a phase 1 trial of patients with relapsed/refractory lymphoma or multiple myeloma (MM), according to an investigator involved in the study.

A majority of patients who recieved the drug, pevonedistat, achieved stable disease, and a few patients with lymphoma experienced partial responses.

Investigators said pevonedistat could be given safely, although 100% of patients experienced adverse events (AEs), and a majority experienced grade 3 or higher AEs.

“The most important findings from our study are that pevonedistat hits its target in cancer cells in patients, can be given safely, and has modest activity in heavily pretreated patients with relapsed/refractory lymphoma, suggesting that we are on the right path,” said Jatin J. Shah, MD, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Dr Shah and his colleagues reported these findings in Clinical Cancer Research. The trial was sponsored by Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing pevonedistat.

Pevonedistat is a first-in-class, investigational, small-molecule inhibitor of the NEDD8-activating enzyme.

“This enzyme is part of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, which is the target of a number of FDA-approved anticancer therapeutics, including bortezomib . . . ,” Dr Shah explained. “Pevonedistat also alters the ability of cancer cells to repair damaged DNA.”

Patient and treatment characteristics

Dr Shah and his colleagues enrolled 44 patients on this trial. Seventeen patients had relapsed/refractory MM, and 27 had relapsed/refractory lymphoma.

The types of lymphoma were diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (n=10), follicular lymphoma (n=5), Hodgkin lymphoma (n=5), small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia (n=2), mantle cell lymphoma (n=1), lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (n=1), peripheral T-cell lymphoma (n=1), splenic marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (n=1), and “other” (n=1).

Twenty-seven patients received escalating doses of pevonedistat on schedule A, which was days 1, 2, 8, and 9 of a 21-day cycle, and 17 patients received escalating doses of the drug on schedule B, which was days 1, 4, 8, and 11 of a 21-day cycle.

Safety

The maximum tolerated doses were 110 mg/m2 and 196 mg/m2 on schedule A and B, respectively. The dose-limiting toxicities were febrile neutropenia, transaminase elevations, and muscle cramps on schedule A, and thrombocytopenia on schedule B.

On schedule A, 100% of patients experienced AEs, and 59% had AEs of grade 3 or higher. The grade 3 or higher AEs were anemia (19%), thrombocytopenia (4%), neutropenia (7%), fatigue (7%), ALT increase (4%), AST increase (7%), diarrhea (4%), pain (4%), dyspnea (4%), hypercalcemia (7%), hypophosphatemia (11%), hyperkalemia (4%), muscle spasms (4%), abdominal discomfort (4%), and pneumonia (4%).

On schedule B, 100% of patients experienced AEs, and 71% had grade 3 or higher AEs. The grade 3 or higher AEs were anemia (6%), thrombocytopenia (6%), neutropenia (12%), fatigue (6%), ALT increase (6%), pyrexia (6%), pain (6%), dyspnea (6%), hypophosphatemia (6%), muscle spasms (6%), upper respiratory tract infection (6%), dehydration (6%), hyperbilirubinemia (6%), and pneumonia (12%).

Efficacy

Three patients had a partial response to treatment, including 1 patient with relapsed nodular sclerosis Hodgkin lymphoma, 1 with relapsed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and 1 with relapsed peripheral T-cell lymphoma.

Another 30 patients, 17 with lymphoma and 13 with MM, had stable disease.

“Although pevonedistat had modest activity as a single-agent treatment, we expect greater activity when it is given in combination with standard therapy,” Dr Shah said.

“The pharmacodynamics data showed that pevonedistat hit its target in cancer cells in patients at low doses. This is important because it may mean that we do not need to escalate the dose in future trials to increase anticancer activity. This has the potential to increase the risk-benefit ratio of pevonedistat.”

Dr Shah said a limitation of this study is that it included a small number of patients, all of whom were very heavily pretreated, which may limit assessment of how active pevonedistat could be. ![]()

A small-molecule inhibitor has shown modest anticancer activity in a phase 1 trial of patients with relapsed/refractory lymphoma or multiple myeloma (MM), according to an investigator involved in the study.

A majority of patients who recieved the drug, pevonedistat, achieved stable disease, and a few patients with lymphoma experienced partial responses.

Investigators said pevonedistat could be given safely, although 100% of patients experienced adverse events (AEs), and a majority experienced grade 3 or higher AEs.

“The most important findings from our study are that pevonedistat hits its target in cancer cells in patients, can be given safely, and has modest activity in heavily pretreated patients with relapsed/refractory lymphoma, suggesting that we are on the right path,” said Jatin J. Shah, MD, of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Dr Shah and his colleagues reported these findings in Clinical Cancer Research. The trial was sponsored by Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing pevonedistat.

Pevonedistat is a first-in-class, investigational, small-molecule inhibitor of the NEDD8-activating enzyme.

“This enzyme is part of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, which is the target of a number of FDA-approved anticancer therapeutics, including bortezomib . . . ,” Dr Shah explained. “Pevonedistat also alters the ability of cancer cells to repair damaged DNA.”

Patient and treatment characteristics

Dr Shah and his colleagues enrolled 44 patients on this trial. Seventeen patients had relapsed/refractory MM, and 27 had relapsed/refractory lymphoma.

The types of lymphoma were diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (n=10), follicular lymphoma (n=5), Hodgkin lymphoma (n=5), small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia (n=2), mantle cell lymphoma (n=1), lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (n=1), peripheral T-cell lymphoma (n=1), splenic marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (n=1), and “other” (n=1).

Twenty-seven patients received escalating doses of pevonedistat on schedule A, which was days 1, 2, 8, and 9 of a 21-day cycle, and 17 patients received escalating doses of the drug on schedule B, which was days 1, 4, 8, and 11 of a 21-day cycle.

Safety

The maximum tolerated doses were 110 mg/m2 and 196 mg/m2 on schedule A and B, respectively. The dose-limiting toxicities were febrile neutropenia, transaminase elevations, and muscle cramps on schedule A, and thrombocytopenia on schedule B.

On schedule A, 100% of patients experienced AEs, and 59% had AEs of grade 3 or higher. The grade 3 or higher AEs were anemia (19%), thrombocytopenia (4%), neutropenia (7%), fatigue (7%), ALT increase (4%), AST increase (7%), diarrhea (4%), pain (4%), dyspnea (4%), hypercalcemia (7%), hypophosphatemia (11%), hyperkalemia (4%), muscle spasms (4%), abdominal discomfort (4%), and pneumonia (4%).

On schedule B, 100% of patients experienced AEs, and 71% had grade 3 or higher AEs. The grade 3 or higher AEs were anemia (6%), thrombocytopenia (6%), neutropenia (12%), fatigue (6%), ALT increase (6%), pyrexia (6%), pain (6%), dyspnea (6%), hypophosphatemia (6%), muscle spasms (6%), upper respiratory tract infection (6%), dehydration (6%), hyperbilirubinemia (6%), and pneumonia (12%).

Efficacy

Three patients had a partial response to treatment, including 1 patient with relapsed nodular sclerosis Hodgkin lymphoma, 1 with relapsed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and 1 with relapsed peripheral T-cell lymphoma.

Another 30 patients, 17 with lymphoma and 13 with MM, had stable disease.

“Although pevonedistat had modest activity as a single-agent treatment, we expect greater activity when it is given in combination with standard therapy,” Dr Shah said.

“The pharmacodynamics data showed that pevonedistat hit its target in cancer cells in patients at low doses. This is important because it may mean that we do not need to escalate the dose in future trials to increase anticancer activity. This has the potential to increase the risk-benefit ratio of pevonedistat.”

Dr Shah said a limitation of this study is that it included a small number of patients, all of whom were very heavily pretreated, which may limit assessment of how active pevonedistat could be. ![]()

Drug ‘life-changing’ for CLL patients in phase 1 trial

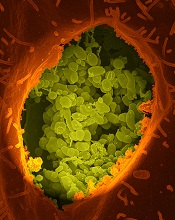

Photo courtesy of NIH

A novel Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor has proven life-changing for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who received the drug as part of a phase 1 trial, according to the study’s lead author.

The inhibitor, ONO/GS-4059, produced a response in 96% of evaluable CLL patients.

Most CLL patients are still on the study after 3 years, although a handful withdrew due to adverse events (AEs) or disease progression.

“These patients were confronted with a cruel reality: they had failed multiple chemotherapy lines, and there were no other treatment options available for them,” said lead study author Harriet Walter, MBChB, of the University of Leicester in the UK.

“This drug has changed their lives. From desperate and tired, they are now leading a normal and really active life. This is hugely rewarding and encouraging.”

Dr Walter and her colleagues reported these results in Blood. The trial was funded by ONO Pharmaceuticals, the company developing ONO/GS-4059.

This study opened in January 2012, and 90 patients were enrolled at centers in the UK and France. There were 28 patients with CLL and 62 with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), including 16 with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) and 35 with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

The study also included patients with follicular lymphoma, marginal zone lymphoma, small lymphocytic lymphoma, and Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia, but patient numbers were small for these groups, so the results were not discussed in detail.

There were 9 dose-escalation cohorts in this study. ONO/GS-4059 was given once-daily at doses ranging from 20 mg to 600 mg. Or the drug was given twice daily at doses of 240 mg or 300 mg.

Results

The maximum tolerated dose was not reached in the CLL cohort, but it was 480 mg once-daily in the NHL cohort. Four NHL patients had a dose-limiting toxicity.

In the CLL cohort, 2 patients went off study due to progression and 5 due to AEs.

In the NHL cohort, 49 patients discontinued treatment, 32 due to progression and 5 due to dose-limiting toxicities or AEs. The other 12 NHL patients discontinued due to patient or investigator decision, proceeding to transplant (n=1), or death due to progressive disease.

The median duration of follow-up was 560 days for CLL patients, 309 days for MCL patients, and 60 days for DLBCL patients.

The overall estimated mean progression-free survival was 874 days for CLL patients, 341 days for MCL patients, and 54 days for DLBCL patients.

CLL patients

Of all 28 CLL patients, 16 had relapsed CLL, 11 had refractory disease, and 1 had unknown status. The median number of prior therapies was 3.5 (range, 2-7).

Twenty-five patients were evaluable. Of the 3 who were not evaluable, 1 had not reached cycle 3 disease assessment at the time of data analysis, 1 progressed during cycle 1, and 1 was withdrawn due to an AE (idiopathic thrombocytopenia).

Of the 25 evaluable patients, 24 (96%) responded to ONO/GS-4059. The researchers said they observed rapid resolution of bulky lymphadenopathy within the first 3 months of treatment, but improvement in lymphadenopathy continued for up to 18 months in most patients.

The median treatment duration for these patients is 80 weeks, and 21 patients are still on treatment. Two of the evaluable patients progressed during therapy, one at cycle 3 and one at cycle 12.

MCL patients

Of the 16 MCL patients enrolled, 7 were refractory to their last course of immuno-chemotherapy. The median number of prior therapies was 3 (range, 2-7).

Eleven of 12 (92%) evaluable patients with MCL responded to ONO/GS-4059. Six patients had a partial response, and 5 had a complete response (CR) or unconfirmed CR.

Three patients progressed after an initial response. Four patients were not evaluable because they progressed.

The median treatment duration for MCL patients is 40 weeks, and 8 patients remain on study.

DLBCL patients

All 35 DLBCL patients had relapsed or refractory disease. The median number of prior treatments was 3

(range, 2-10), and 30 patients were refractory to their last line of chemotherapy.

Eleven of 31 (35%) patients with non-germinal center B-cell (non-GCB) DLBCL responded to ONO/GS-4059. Two non-GCB DLBCL patients had a confirmed CR, 1 had an unconfirmed CR, and the rest had partial responses.

The median duration of response was 54 days. And, among responders, the median treatment duration was 12 weeks.

The majority of non-GCB DLBCL patients progressed. There were no responses among the 2 patients with GCB DLBCL, and there were no responses among patients with primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma or plasmablastic DLBCL.

Toxicity

AEs in this study were mostly grade 1/2—75% in the CLL cohort and 50% in the NHL cohort. However, treatment-related grade 3/4 AEs occurred in 14.3% of CLL patients and 16.1% of NHL patients.

Grade 3/4 events were mainly hematologic in nature and included neutropenia (10%), anemia (13.3%), and thrombocytopenia (13.3%).

There was a grade 3 episode of drug-related hemorrhage in a CLL patient, which resulted in a psoas hematoma (with concomitant CLL progression) in the presence of a normal platelet count. This patient was among those taken off the study.

“The next step is now to see how best we can improve on these outstanding results,” said study author Martin Dyer, DPhil, of the University of Leicester.

“A further study using this drug in combination with additional targeted agents is shortly to open in Leicester with the aim of achieving cure. In parallel with the clinical development of the drug, our team of scientists at the Haematological Research Institute are studying how this drug is working and how to overcome potential resistance.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of NIH

A novel Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor has proven life-changing for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who received the drug as part of a phase 1 trial, according to the study’s lead author.

The inhibitor, ONO/GS-4059, produced a response in 96% of evaluable CLL patients.

Most CLL patients are still on the study after 3 years, although a handful withdrew due to adverse events (AEs) or disease progression.

“These patients were confronted with a cruel reality: they had failed multiple chemotherapy lines, and there were no other treatment options available for them,” said lead study author Harriet Walter, MBChB, of the University of Leicester in the UK.

“This drug has changed their lives. From desperate and tired, they are now leading a normal and really active life. This is hugely rewarding and encouraging.”

Dr Walter and her colleagues reported these results in Blood. The trial was funded by ONO Pharmaceuticals, the company developing ONO/GS-4059.

This study opened in January 2012, and 90 patients were enrolled at centers in the UK and France. There were 28 patients with CLL and 62 with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), including 16 with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) and 35 with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

The study also included patients with follicular lymphoma, marginal zone lymphoma, small lymphocytic lymphoma, and Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia, but patient numbers were small for these groups, so the results were not discussed in detail.

There were 9 dose-escalation cohorts in this study. ONO/GS-4059 was given once-daily at doses ranging from 20 mg to 600 mg. Or the drug was given twice daily at doses of 240 mg or 300 mg.

Results

The maximum tolerated dose was not reached in the CLL cohort, but it was 480 mg once-daily in the NHL cohort. Four NHL patients had a dose-limiting toxicity.

In the CLL cohort, 2 patients went off study due to progression and 5 due to AEs.

In the NHL cohort, 49 patients discontinued treatment, 32 due to progression and 5 due to dose-limiting toxicities or AEs. The other 12 NHL patients discontinued due to patient or investigator decision, proceeding to transplant (n=1), or death due to progressive disease.

The median duration of follow-up was 560 days for CLL patients, 309 days for MCL patients, and 60 days for DLBCL patients.

The overall estimated mean progression-free survival was 874 days for CLL patients, 341 days for MCL patients, and 54 days for DLBCL patients.

CLL patients

Of all 28 CLL patients, 16 had relapsed CLL, 11 had refractory disease, and 1 had unknown status. The median number of prior therapies was 3.5 (range, 2-7).

Twenty-five patients were evaluable. Of the 3 who were not evaluable, 1 had not reached cycle 3 disease assessment at the time of data analysis, 1 progressed during cycle 1, and 1 was withdrawn due to an AE (idiopathic thrombocytopenia).

Of the 25 evaluable patients, 24 (96%) responded to ONO/GS-4059. The researchers said they observed rapid resolution of bulky lymphadenopathy within the first 3 months of treatment, but improvement in lymphadenopathy continued for up to 18 months in most patients.

The median treatment duration for these patients is 80 weeks, and 21 patients are still on treatment. Two of the evaluable patients progressed during therapy, one at cycle 3 and one at cycle 12.

MCL patients

Of the 16 MCL patients enrolled, 7 were refractory to their last course of immuno-chemotherapy. The median number of prior therapies was 3 (range, 2-7).

Eleven of 12 (92%) evaluable patients with MCL responded to ONO/GS-4059. Six patients had a partial response, and 5 had a complete response (CR) or unconfirmed CR.

Three patients progressed after an initial response. Four patients were not evaluable because they progressed.

The median treatment duration for MCL patients is 40 weeks, and 8 patients remain on study.

DLBCL patients

All 35 DLBCL patients had relapsed or refractory disease. The median number of prior treatments was 3

(range, 2-10), and 30 patients were refractory to their last line of chemotherapy.

Eleven of 31 (35%) patients with non-germinal center B-cell (non-GCB) DLBCL responded to ONO/GS-4059. Two non-GCB DLBCL patients had a confirmed CR, 1 had an unconfirmed CR, and the rest had partial responses.

The median duration of response was 54 days. And, among responders, the median treatment duration was 12 weeks.

The majority of non-GCB DLBCL patients progressed. There were no responses among the 2 patients with GCB DLBCL, and there were no responses among patients with primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma or plasmablastic DLBCL.

Toxicity

AEs in this study were mostly grade 1/2—75% in the CLL cohort and 50% in the NHL cohort. However, treatment-related grade 3/4 AEs occurred in 14.3% of CLL patients and 16.1% of NHL patients.

Grade 3/4 events were mainly hematologic in nature and included neutropenia (10%), anemia (13.3%), and thrombocytopenia (13.3%).

There was a grade 3 episode of drug-related hemorrhage in a CLL patient, which resulted in a psoas hematoma (with concomitant CLL progression) in the presence of a normal platelet count. This patient was among those taken off the study.

“The next step is now to see how best we can improve on these outstanding results,” said study author Martin Dyer, DPhil, of the University of Leicester.

“A further study using this drug in combination with additional targeted agents is shortly to open in Leicester with the aim of achieving cure. In parallel with the clinical development of the drug, our team of scientists at the Haematological Research Institute are studying how this drug is working and how to overcome potential resistance.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of NIH

A novel Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor has proven life-changing for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) who received the drug as part of a phase 1 trial, according to the study’s lead author.

The inhibitor, ONO/GS-4059, produced a response in 96% of evaluable CLL patients.

Most CLL patients are still on the study after 3 years, although a handful withdrew due to adverse events (AEs) or disease progression.

“These patients were confronted with a cruel reality: they had failed multiple chemotherapy lines, and there were no other treatment options available for them,” said lead study author Harriet Walter, MBChB, of the University of Leicester in the UK.

“This drug has changed their lives. From desperate and tired, they are now leading a normal and really active life. This is hugely rewarding and encouraging.”

Dr Walter and her colleagues reported these results in Blood. The trial was funded by ONO Pharmaceuticals, the company developing ONO/GS-4059.

This study opened in January 2012, and 90 patients were enrolled at centers in the UK and France. There were 28 patients with CLL and 62 with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), including 16 with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) and 35 with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

The study also included patients with follicular lymphoma, marginal zone lymphoma, small lymphocytic lymphoma, and Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia, but patient numbers were small for these groups, so the results were not discussed in detail.

There were 9 dose-escalation cohorts in this study. ONO/GS-4059 was given once-daily at doses ranging from 20 mg to 600 mg. Or the drug was given twice daily at doses of 240 mg or 300 mg.

Results

The maximum tolerated dose was not reached in the CLL cohort, but it was 480 mg once-daily in the NHL cohort. Four NHL patients had a dose-limiting toxicity.

In the CLL cohort, 2 patients went off study due to progression and 5 due to AEs.

In the NHL cohort, 49 patients discontinued treatment, 32 due to progression and 5 due to dose-limiting toxicities or AEs. The other 12 NHL patients discontinued due to patient or investigator decision, proceeding to transplant (n=1), or death due to progressive disease.

The median duration of follow-up was 560 days for CLL patients, 309 days for MCL patients, and 60 days for DLBCL patients.

The overall estimated mean progression-free survival was 874 days for CLL patients, 341 days for MCL patients, and 54 days for DLBCL patients.

CLL patients

Of all 28 CLL patients, 16 had relapsed CLL, 11 had refractory disease, and 1 had unknown status. The median number of prior therapies was 3.5 (range, 2-7).

Twenty-five patients were evaluable. Of the 3 who were not evaluable, 1 had not reached cycle 3 disease assessment at the time of data analysis, 1 progressed during cycle 1, and 1 was withdrawn due to an AE (idiopathic thrombocytopenia).

Of the 25 evaluable patients, 24 (96%) responded to ONO/GS-4059. The researchers said they observed rapid resolution of bulky lymphadenopathy within the first 3 months of treatment, but improvement in lymphadenopathy continued for up to 18 months in most patients.

The median treatment duration for these patients is 80 weeks, and 21 patients are still on treatment. Two of the evaluable patients progressed during therapy, one at cycle 3 and one at cycle 12.

MCL patients

Of the 16 MCL patients enrolled, 7 were refractory to their last course of immuno-chemotherapy. The median number of prior therapies was 3 (range, 2-7).

Eleven of 12 (92%) evaluable patients with MCL responded to ONO/GS-4059. Six patients had a partial response, and 5 had a complete response (CR) or unconfirmed CR.

Three patients progressed after an initial response. Four patients were not evaluable because they progressed.

The median treatment duration for MCL patients is 40 weeks, and 8 patients remain on study.

DLBCL patients

All 35 DLBCL patients had relapsed or refractory disease. The median number of prior treatments was 3

(range, 2-10), and 30 patients were refractory to their last line of chemotherapy.

Eleven of 31 (35%) patients with non-germinal center B-cell (non-GCB) DLBCL responded to ONO/GS-4059. Two non-GCB DLBCL patients had a confirmed CR, 1 had an unconfirmed CR, and the rest had partial responses.

The median duration of response was 54 days. And, among responders, the median treatment duration was 12 weeks.

The majority of non-GCB DLBCL patients progressed. There were no responses among the 2 patients with GCB DLBCL, and there were no responses among patients with primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma or plasmablastic DLBCL.

Toxicity

AEs in this study were mostly grade 1/2—75% in the CLL cohort and 50% in the NHL cohort. However, treatment-related grade 3/4 AEs occurred in 14.3% of CLL patients and 16.1% of NHL patients.

Grade 3/4 events were mainly hematologic in nature and included neutropenia (10%), anemia (13.3%), and thrombocytopenia (13.3%).

There was a grade 3 episode of drug-related hemorrhage in a CLL patient, which resulted in a psoas hematoma (with concomitant CLL progression) in the presence of a normal platelet count. This patient was among those taken off the study.

“The next step is now to see how best we can improve on these outstanding results,” said study author Martin Dyer, DPhil, of the University of Leicester.

“A further study using this drug in combination with additional targeted agents is shortly to open in Leicester with the aim of achieving cure. In parallel with the clinical development of the drug, our team of scientists at the Haematological Research Institute are studying how this drug is working and how to overcome potential resistance.” ![]()

ITC 2015: Review IDs features to aid thyroid lymphoma diagnosis

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. – Rapidly enlarging thyroid masses with compressive symptoms may signal thyroid lymphoma, according to findings from a review of cases at the Mayo Clinic.

Radiologically, these masses tend to present as large, unilateral, thyroid-centered masses that are hypoechoic on ultrasound and that expand into adjacent soft tissue, Dr. Anu Sharma reported at the International Thyroid Congress.

The findings are based on a review of 75 patients with biopsy-proven thyroid lymphoma – a relatively rare disease, accounting for between 1% and 5% of all thyroid malignancies, and less than 1% of all lymphomas – who presented to the Mayo Clinic between 2000 and 2014.

“Thyroid lymphoma can sometimes present very similar to anaplastic carcinoma, and we wanted to see if there are any unique identification factors that you can use to increase your suspicion of thyroid lymphoma,” Dr. Sharma of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said.

Indeed, rapid enlargement and compressive symptoms are also common presenting features of anaplastic carcinoma, she said.

Of the 75 cases included in the review – compromising all cases presenting during the study period – 70.7% involved primary thyroid lymphoma. A neck mass was present in 88% of cases, dysphagia in 45%, and hoarseness in 37%.

The typical presentation included a solid, hypoechoic mass with mildly increased vascularity, no internal calcifications, and edge characteristics that ranged from well-defined (80%) to ill-defined (20%). Median tumor volume was 64 cm3, Dr. Sharma said.

This differs from anaplastic carcinoma in that most patients with anaplastic carcinoma have ill-defined edges, she noted.

Another difference between thyroid lymphoma and anaplastic carcinoma as noted in this study involves necrosis; none of the patients in the current study had areas of necrosis, whereas 78% of anaplastic carcinoma patients in another study had areas of necrosis, she explained.

The patients in the current study had a median age of 67 years, although the ages varied widely. About half (50.7%) were men, and 54.7% had a history of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Fifty-seven of the patients had an ultrasound before treatment.

The first diagnostic procedure performed was fine needle aspiration (FNA) in 65 subjects, and the FNA biopsies were abnormal in 69% of those, with 42% suggesting a specific lymphoma subtype. The subtype diagnosis was accurate, based on final tissue analysis, in 89% of those.

“While this is quite impressive, all patients who had FNA ended up having further tissue biopsy for subtype confirmation and for treatment, and this is important, because the subtype of the lymphoma is important in determining the type of treatment uses as well as determining prognosis,” she said.

The diagnosis was confirmed by core biopsy in 46.7% of cases, by incisional biopsy in 9.3%, by partial or total thyroidectomy in 25.3%, and by lymph node biopsy in 13.3%; percentages total 94.6% due to downward rounding. Histologic subtypes included diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) in 73.3% of cases, follicular lymphoma in 5.3%, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) in 10.7%, MALT/DLBCL in 2.6%, T-cell lymphoma in 2.6%, and Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 1.3%; percentages total 95.8% rather than 100% due to downward rounding.

In addition to rapid enlargement of a neck mass with compressive symptoms, findings that should raise suspicion of thyroid lymphoma include a history of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and the ultrasound findings characterized by this study, Dr. Sharma said.

“Once you have that increased suspicion, you should move toward going to core biopsy rather than FNA to save the patient from having two diagnostic steps rather than one,” she concluded.

Dr. Sharma reported having no disclosures.

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. – Rapidly enlarging thyroid masses with compressive symptoms may signal thyroid lymphoma, according to findings from a review of cases at the Mayo Clinic.

Radiologically, these masses tend to present as large, unilateral, thyroid-centered masses that are hypoechoic on ultrasound and that expand into adjacent soft tissue, Dr. Anu Sharma reported at the International Thyroid Congress.

The findings are based on a review of 75 patients with biopsy-proven thyroid lymphoma – a relatively rare disease, accounting for between 1% and 5% of all thyroid malignancies, and less than 1% of all lymphomas – who presented to the Mayo Clinic between 2000 and 2014.

“Thyroid lymphoma can sometimes present very similar to anaplastic carcinoma, and we wanted to see if there are any unique identification factors that you can use to increase your suspicion of thyroid lymphoma,” Dr. Sharma of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said.

Indeed, rapid enlargement and compressive symptoms are also common presenting features of anaplastic carcinoma, she said.

Of the 75 cases included in the review – compromising all cases presenting during the study period – 70.7% involved primary thyroid lymphoma. A neck mass was present in 88% of cases, dysphagia in 45%, and hoarseness in 37%.

The typical presentation included a solid, hypoechoic mass with mildly increased vascularity, no internal calcifications, and edge characteristics that ranged from well-defined (80%) to ill-defined (20%). Median tumor volume was 64 cm3, Dr. Sharma said.

This differs from anaplastic carcinoma in that most patients with anaplastic carcinoma have ill-defined edges, she noted.

Another difference between thyroid lymphoma and anaplastic carcinoma as noted in this study involves necrosis; none of the patients in the current study had areas of necrosis, whereas 78% of anaplastic carcinoma patients in another study had areas of necrosis, she explained.

The patients in the current study had a median age of 67 years, although the ages varied widely. About half (50.7%) were men, and 54.7% had a history of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Fifty-seven of the patients had an ultrasound before treatment.

The first diagnostic procedure performed was fine needle aspiration (FNA) in 65 subjects, and the FNA biopsies were abnormal in 69% of those, with 42% suggesting a specific lymphoma subtype. The subtype diagnosis was accurate, based on final tissue analysis, in 89% of those.

“While this is quite impressive, all patients who had FNA ended up having further tissue biopsy for subtype confirmation and for treatment, and this is important, because the subtype of the lymphoma is important in determining the type of treatment uses as well as determining prognosis,” she said.

The diagnosis was confirmed by core biopsy in 46.7% of cases, by incisional biopsy in 9.3%, by partial or total thyroidectomy in 25.3%, and by lymph node biopsy in 13.3%; percentages total 94.6% due to downward rounding. Histologic subtypes included diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) in 73.3% of cases, follicular lymphoma in 5.3%, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) in 10.7%, MALT/DLBCL in 2.6%, T-cell lymphoma in 2.6%, and Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 1.3%; percentages total 95.8% rather than 100% due to downward rounding.

In addition to rapid enlargement of a neck mass with compressive symptoms, findings that should raise suspicion of thyroid lymphoma include a history of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and the ultrasound findings characterized by this study, Dr. Sharma said.

“Once you have that increased suspicion, you should move toward going to core biopsy rather than FNA to save the patient from having two diagnostic steps rather than one,” she concluded.

Dr. Sharma reported having no disclosures.

LAKE BUENA VISTA, FLA. – Rapidly enlarging thyroid masses with compressive symptoms may signal thyroid lymphoma, according to findings from a review of cases at the Mayo Clinic.

Radiologically, these masses tend to present as large, unilateral, thyroid-centered masses that are hypoechoic on ultrasound and that expand into adjacent soft tissue, Dr. Anu Sharma reported at the International Thyroid Congress.

The findings are based on a review of 75 patients with biopsy-proven thyroid lymphoma – a relatively rare disease, accounting for between 1% and 5% of all thyroid malignancies, and less than 1% of all lymphomas – who presented to the Mayo Clinic between 2000 and 2014.

“Thyroid lymphoma can sometimes present very similar to anaplastic carcinoma, and we wanted to see if there are any unique identification factors that you can use to increase your suspicion of thyroid lymphoma,” Dr. Sharma of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said.

Indeed, rapid enlargement and compressive symptoms are also common presenting features of anaplastic carcinoma, she said.

Of the 75 cases included in the review – compromising all cases presenting during the study period – 70.7% involved primary thyroid lymphoma. A neck mass was present in 88% of cases, dysphagia in 45%, and hoarseness in 37%.

The typical presentation included a solid, hypoechoic mass with mildly increased vascularity, no internal calcifications, and edge characteristics that ranged from well-defined (80%) to ill-defined (20%). Median tumor volume was 64 cm3, Dr. Sharma said.

This differs from anaplastic carcinoma in that most patients with anaplastic carcinoma have ill-defined edges, she noted.

Another difference between thyroid lymphoma and anaplastic carcinoma as noted in this study involves necrosis; none of the patients in the current study had areas of necrosis, whereas 78% of anaplastic carcinoma patients in another study had areas of necrosis, she explained.

The patients in the current study had a median age of 67 years, although the ages varied widely. About half (50.7%) were men, and 54.7% had a history of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Fifty-seven of the patients had an ultrasound before treatment.

The first diagnostic procedure performed was fine needle aspiration (FNA) in 65 subjects, and the FNA biopsies were abnormal in 69% of those, with 42% suggesting a specific lymphoma subtype. The subtype diagnosis was accurate, based on final tissue analysis, in 89% of those.

“While this is quite impressive, all patients who had FNA ended up having further tissue biopsy for subtype confirmation and for treatment, and this is important, because the subtype of the lymphoma is important in determining the type of treatment uses as well as determining prognosis,” she said.

The diagnosis was confirmed by core biopsy in 46.7% of cases, by incisional biopsy in 9.3%, by partial or total thyroidectomy in 25.3%, and by lymph node biopsy in 13.3%; percentages total 94.6% due to downward rounding. Histologic subtypes included diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) in 73.3% of cases, follicular lymphoma in 5.3%, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) in 10.7%, MALT/DLBCL in 2.6%, T-cell lymphoma in 2.6%, and Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 1.3%; percentages total 95.8% rather than 100% due to downward rounding.

In addition to rapid enlargement of a neck mass with compressive symptoms, findings that should raise suspicion of thyroid lymphoma include a history of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and the ultrasound findings characterized by this study, Dr. Sharma said.

“Once you have that increased suspicion, you should move toward going to core biopsy rather than FNA to save the patient from having two diagnostic steps rather than one,” she concluded.

Dr. Sharma reported having no disclosures.

AT ITC 2015

Key clinical point: Rapidly enlarging thyroid masses with compressive symptoms may signal thyroid lymphoma, according to findings from a review of cases at the Mayo Clinic.

Major finding: Typical presentation included a solid, hypoechoic mass with mildly increased vascularity, no internal calcifications, and edge characteristics that ranged from well-defined (80%) to ill-defined (20%).

Data source: A retrospective review of 75 cases.

Disclosures: Dr. Sharma reported having no disclosures.

New therapies finding their place in management of follicular lymphoma

SAN FRANCISCO – A variety of emerging therapies are being incorporated into the management of follicular lymphoma, which is typically a long-term endeavor requiring strategic use of multiple treatments, Dr. Andrew D. Zelenetz said at the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) 10th Annual Congress: Hematologic Malignancies.

“Follicular lymphoma is a disease of paradox. The reality is that overall survival is excellent, but patients are not going to be able to do that with one treatment; they are going to get a series of treatments,” he said. “Survival is the sum of your exposures to treatment, time on active therapy, time in remission, and actually time with relapse not needing treatment.”

Risk stratification

Overall survival for patients with follicular lymphoma diagnosed today and treated with modern therapy is only slightly inferior to that for age-matched controls, noted Dr. Zelenetz of the department of medicine at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and professor of medicine at Cornell University, both in New York.

But patients who are faring poorly at 12 months (American Society of Hematology [ASH] 2014, Abstract 1664) or at 24 months (J Clin Oncol. 2015;33[23]:2516-22) into care have a much worse prognosis. “This shows the importance of identifying those patients with poor biology, and [the question of] whether we can identify them without treating them first and having them progress,” he said.

Hematologists have historically looked to the Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI) to estimate outcome. “The FLIPI clearly works; it’s an important clinical tool. But the FLIPI high-risk patients are still identifying more than those very high-risk patients,” he said.

Therefore, a clinicogenomic risk model was developed that incorporates seven mutations having poor prognostic impact, the m7-FLIPI (Lancet Oncol. 2015;16[9]:1111-22). Adding the mutations split the previously defined high-risk patients into a group with a prognosis similar to that of low-risk patients and a small group with a very poor prognosis.

“This actually represents something very close to the 20% of patients that we think have bad biology,” Dr. Zelenetz noted. “There will be some additional data at ASH looking at this exact question, because the holy grail is to know when you diagnose someone if they are in that bad-risk group because those are the patients you want to do novel clinical trials on. If your overall survival is equivalent to the general population, it’s going to be hard to ever prove an overall survival advantage for an intervention in an unselected group of patients.”

Advanced-stage disease with low tumor bulk

For patients who have advanced-stage follicular lymphoma but with low tumor bulk, the NCCN endorses a modification of criteria developed by the Follicular Lymphoma Study Group (GELF) in deciding when to start treatment (J Clin Oncol. 1998;16[7]:2332-8).

Roughly a fifth of patients who are eligible for and managed with a watch-and-wait approach will not need chemotherapy or die of their disease in the next 10 years (Lancet. 2003;362[9383]:516-22). Furthermore, this strategy nets a median delay in the need for chemotherapy of 2.6 years.

Compared with observation, treatment with the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab (Rituxan) improves progression-free survival but not overall survival in this setting (ASH 2010, Abstract 6). “Though in selected patients, rituximab may be appropriate as initial treatment for the observable patient, I would argue for the observable patient with no survival disadvantage, the standard of care remains observation,” Dr. Zelenetz said.

Advanced-stage disease requiring treatment

A meta-analysis has shown a clear survival benefit from adding rituximab to chemotherapy (R-chemo) in patients with advanced follicular lymphoma who need treatment (J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99[9]:706-14). “Based on the results, it is the standard of care to add rituximab to a chemotherapy backbone, but the optimum R-chemo actually remains undefined and would be customized to the individual clinical situation,” he commented.

A variety of emerging agents are being tested in this setting. Among the subset of patients with untreated follicular lymphoma in a single-center trial, the combination of rituximab with the immunomodulator lenalidomide (Revlimid) yielded an overall response rate of 98% and a complete response rate of 87%, as well as excellent progression-free and overall survival (Lancet Oncol. 2014;15[12]:1311-8). The main grade 3 or 4 toxicity was neutropenia, seen in 35% of all patients studied. Efficacy results were much the same in a multicenter trial (International Conference on Malignant Lymphoma [ICML] 2013, Abstract 63).

This combination is now being tested as front-line therapy for follicular lymphoma in the RELEVANCE (Rituximab and Lenalidomide Versus Any Chemotherapy) phase III trial. “The trial is now done, but we don’t have results, and we won’t have results until 2019, so don’t hold your breath,” Dr. Zelenetz commented. “That’s because this was an unselected trial; we took all patients, all comers. And if you don’t try to identify bad-risk patients, you actually have to do very large trials, and the effect size is relatively small.”

Relapsed and refractory disease

“Many times when patients with follicular lymphoma relapse, they are immediately started on treatment. It’s not necessary and probably in most cases not appropriate. If patients are asymptomatic and have a low tumor burden, they can have a second and a third and even a fourth period of observation, where they don’t need active treatment,” he said. “So I would encourage you to …wait until they actually meet GELF criteria again.”

A key question in this setting is whether patients previously given rituximab can derive benefit from an alternative anti-CD20 antibody. Taking on this question, the GADOLIN trial tested the addition of obinutuzumab (induction plus maintenance) to bendamustine among patients with rituximab-refractory disease (American Society of Clinical Oncology [ASCO] 2015, Abstract LBA8502; ICML 2015, Abstract 123).

Toxicities were generally similar by arm, except for a higher rate of infusion-related reactions with obinutuzumab. The overall response rates were comparable for the two arms, but progression-free survival was better with the combination (median event-free survival, not reached, vs. 14.9 months; hazard ratio, 0.55), and there was a trend for overall survival.

“These curves start separating after 6 months, and 6 months is the time of chemotherapy,” Dr. Zelenetz noted. “So I would argue from these data that the obinutuzumab didn’t add very much to the bendamustine backbone, but actually the obinutuzumab maintenance was effective even in rituximab-refractory patients.”

The combination of lenalidomide and rituximab has been compared with lenalidomide alone in patients with relapsed follicular lymphoma (ASCO 2012, Abstract 8000). The results showed a trend toward better median event-free survival with the combination (2.0 vs. 1.2 years; hazard ratio, 1.9; P = .061) but not overall survival.

In a phase II trial, idelalisib (Zydelig) was tested among patients with indolent non-Hodgkin lymphomas (60% with follicular lymphoma) that were refractory to both rituximab and an alkylator (N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1008-18). Noteworthy grade 3 or worse toxicities included pneumonia and transaminase elevations. The overall response rate was 57%, and the complete response rate was 6%; median progression-free survival was 11 months.

“Idelalisib can be safely combined with other agents including rituximab and bendamustine,” Dr. Zelenetz added (ASH 2014, Abstract 3063). “Interestingly, the overall response seems to be a little higher when you combine it, but it doesn’t seem to matter which drug you combine it with – rituximab, bendamustine, or [both] – you get good overall responses,” ranging from 71% to 85%.

The BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax (formerly ABT-199/GDC-199) has been tested in non-Hodgkin lymphomas, where it has not been associated with the life-threatening tumor lysis syndrome seen in some other hematologic malignancies (European Hematology Association [EHA] 2015, Davis et al). It yielded an overall response rate of 31% in patients with relatively refractory follicular lymphoma. “This will lead to additional studies in this area,” he predicted.

Finally, nivolumab (Opdivo), a PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, has been evaluated in a phase I study in relapsed or refractory hematologic malignancies, where it was well tolerated (ASH 2014, Abstract 291). Among the small subset of patients with follicular lymphoma, the overall response rate was 40%, prompting initiation of more trials.

Although chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy is showing promise in various malignancies, Dr. Zelenetz said that other options are probably better avenues for research in follicular lymphoma at present.

“I’m much more interested in the tools that we have now, between the checkpoint inhibitors, the T-cell activators, and the bispecific monoclonal antibodies. I think I can [apply these therapies] with less money for probably less toxicity without the complexity of having to make a customized drug for the patient,” he said. “So I’m not very enthusiastic about CAR T cells in follicular lymphoma.”

SAN FRANCISCO – A variety of emerging therapies are being incorporated into the management of follicular lymphoma, which is typically a long-term endeavor requiring strategic use of multiple treatments, Dr. Andrew D. Zelenetz said at the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) 10th Annual Congress: Hematologic Malignancies.

“Follicular lymphoma is a disease of paradox. The reality is that overall survival is excellent, but patients are not going to be able to do that with one treatment; they are going to get a series of treatments,” he said. “Survival is the sum of your exposures to treatment, time on active therapy, time in remission, and actually time with relapse not needing treatment.”

Risk stratification