User login

Lateral neck dissection morbidity high, but transient

CHICAGO – Lateral neck dissection for thyroid cancer is associated with significant early postoperative morbidity of 20%, even in the hands of experienced endocrine surgeons at a high-volume medical center.

Among 99 procedures, 20 patients had 26 complications, including surgical site infection in 10, chyle leak in 7, spinal accessory nerve dysfunction in 7, and seroma in 2.

Long-term complications were rare, however, occurring in just one patient with a spinal accessory nerve injury, Dr. Jason A. Glenn said at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association.

Using a prospectively collected thyroid database, the investigators reviewed 96 patients who underwent lateral neck dissection (LND) for suspicion of initial or recurrent lateral neck metastases by one of four experienced endocrine surgeons at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee.

Three patients had reoperations during the study period of February 2009 and June 2014, resulting in 99 procedures and 198 lateral necks evaluated preoperatively. Most patients were women (73%) and their median age was 45 years.

LND was performed on 127 necks and metastatic disease was confirmed in 111 (87%). This included all 82 patients who had positive preoperative fine needle aspiration (FNA), 25 of 37 patients operated on without FNA, and 4 of 8 patients with a negative or nondiagnostic FNA, Dr. Glenn said.

The median number of lymph nodes excised was 22 (range 1-122), with a median of 3 (range 0-39) malignant nodes per lateral neck.

“FNA is an important adjunct in the preoperative evaluation, especially when it returns a positive result,” he said. “However, when FNA is negative, not available, or not performed, you really must consider the entire clinical picture, as 64% of these patients were found to have lymph node metastases in our study.”

Surgical drains were placed in 94% of the 127 lateral neck dissections and remained in place for a median of 6 days. The median length of stay was 1 day.

There was no association between drain duration and surgical site infection, although chyle leak was associated with a significantly longer median drain duration (12 days vs. 6 days; P value < .01), Dr. Glenn said.

Two of the seven patients with chyle leak, defined by drain output that was milky white and/or exceeded 1,000 cc in 24 hours, underwent reoperation with ligation of the cervical thoracic duct and fibrin sealant application. Both leaks resolved and patients were discharge on postoperative day 2.

“Surgical drains allow for early leak recognition and monitoring of leak resolution,” he said. “Most of these complications were diagnosed and managed on an outpatient basis, highlighting the importance of continuity of care between the inpatient and outpatient setting for the treatment of thyroid cancer.”

Discussant Janice L. Pasieka, head of general surgery and a clinical professor of surgery and oncology at the University of Calgary (Alberta), said the retrospective review is a very valuable contribution to the literature because of its comprehensive follow-up.

“Today, most patients with this type of procedure are discharged within the 23 hours, and as such, complications such as nerve palsies, chyle leaks, and surgical site infections are not apparent for the majority of patients during their hospital stay,” Dr. Pasieka said. “Many times, the true incidences are lost unless the patient re-presents to the health care system, thus introducing your bias of only those significant enough to require intervention.”

Dr. Glenn and his coauthors reported no financial disclosures.

CHICAGO – Lateral neck dissection for thyroid cancer is associated with significant early postoperative morbidity of 20%, even in the hands of experienced endocrine surgeons at a high-volume medical center.

Among 99 procedures, 20 patients had 26 complications, including surgical site infection in 10, chyle leak in 7, spinal accessory nerve dysfunction in 7, and seroma in 2.

Long-term complications were rare, however, occurring in just one patient with a spinal accessory nerve injury, Dr. Jason A. Glenn said at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association.

Using a prospectively collected thyroid database, the investigators reviewed 96 patients who underwent lateral neck dissection (LND) for suspicion of initial or recurrent lateral neck metastases by one of four experienced endocrine surgeons at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee.

Three patients had reoperations during the study period of February 2009 and June 2014, resulting in 99 procedures and 198 lateral necks evaluated preoperatively. Most patients were women (73%) and their median age was 45 years.

LND was performed on 127 necks and metastatic disease was confirmed in 111 (87%). This included all 82 patients who had positive preoperative fine needle aspiration (FNA), 25 of 37 patients operated on without FNA, and 4 of 8 patients with a negative or nondiagnostic FNA, Dr. Glenn said.

The median number of lymph nodes excised was 22 (range 1-122), with a median of 3 (range 0-39) malignant nodes per lateral neck.

“FNA is an important adjunct in the preoperative evaluation, especially when it returns a positive result,” he said. “However, when FNA is negative, not available, or not performed, you really must consider the entire clinical picture, as 64% of these patients were found to have lymph node metastases in our study.”

Surgical drains were placed in 94% of the 127 lateral neck dissections and remained in place for a median of 6 days. The median length of stay was 1 day.

There was no association between drain duration and surgical site infection, although chyle leak was associated with a significantly longer median drain duration (12 days vs. 6 days; P value < .01), Dr. Glenn said.

Two of the seven patients with chyle leak, defined by drain output that was milky white and/or exceeded 1,000 cc in 24 hours, underwent reoperation with ligation of the cervical thoracic duct and fibrin sealant application. Both leaks resolved and patients were discharge on postoperative day 2.

“Surgical drains allow for early leak recognition and monitoring of leak resolution,” he said. “Most of these complications were diagnosed and managed on an outpatient basis, highlighting the importance of continuity of care between the inpatient and outpatient setting for the treatment of thyroid cancer.”

Discussant Janice L. Pasieka, head of general surgery and a clinical professor of surgery and oncology at the University of Calgary (Alberta), said the retrospective review is a very valuable contribution to the literature because of its comprehensive follow-up.

“Today, most patients with this type of procedure are discharged within the 23 hours, and as such, complications such as nerve palsies, chyle leaks, and surgical site infections are not apparent for the majority of patients during their hospital stay,” Dr. Pasieka said. “Many times, the true incidences are lost unless the patient re-presents to the health care system, thus introducing your bias of only those significant enough to require intervention.”

Dr. Glenn and his coauthors reported no financial disclosures.

CHICAGO – Lateral neck dissection for thyroid cancer is associated with significant early postoperative morbidity of 20%, even in the hands of experienced endocrine surgeons at a high-volume medical center.

Among 99 procedures, 20 patients had 26 complications, including surgical site infection in 10, chyle leak in 7, spinal accessory nerve dysfunction in 7, and seroma in 2.

Long-term complications were rare, however, occurring in just one patient with a spinal accessory nerve injury, Dr. Jason A. Glenn said at the annual meeting of the Central Surgical Association.

Using a prospectively collected thyroid database, the investigators reviewed 96 patients who underwent lateral neck dissection (LND) for suspicion of initial or recurrent lateral neck metastases by one of four experienced endocrine surgeons at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee.

Three patients had reoperations during the study period of February 2009 and June 2014, resulting in 99 procedures and 198 lateral necks evaluated preoperatively. Most patients were women (73%) and their median age was 45 years.

LND was performed on 127 necks and metastatic disease was confirmed in 111 (87%). This included all 82 patients who had positive preoperative fine needle aspiration (FNA), 25 of 37 patients operated on without FNA, and 4 of 8 patients with a negative or nondiagnostic FNA, Dr. Glenn said.

The median number of lymph nodes excised was 22 (range 1-122), with a median of 3 (range 0-39) malignant nodes per lateral neck.

“FNA is an important adjunct in the preoperative evaluation, especially when it returns a positive result,” he said. “However, when FNA is negative, not available, or not performed, you really must consider the entire clinical picture, as 64% of these patients were found to have lymph node metastases in our study.”

Surgical drains were placed in 94% of the 127 lateral neck dissections and remained in place for a median of 6 days. The median length of stay was 1 day.

There was no association between drain duration and surgical site infection, although chyle leak was associated with a significantly longer median drain duration (12 days vs. 6 days; P value < .01), Dr. Glenn said.

Two of the seven patients with chyle leak, defined by drain output that was milky white and/or exceeded 1,000 cc in 24 hours, underwent reoperation with ligation of the cervical thoracic duct and fibrin sealant application. Both leaks resolved and patients were discharge on postoperative day 2.

“Surgical drains allow for early leak recognition and monitoring of leak resolution,” he said. “Most of these complications were diagnosed and managed on an outpatient basis, highlighting the importance of continuity of care between the inpatient and outpatient setting for the treatment of thyroid cancer.”

Discussant Janice L. Pasieka, head of general surgery and a clinical professor of surgery and oncology at the University of Calgary (Alberta), said the retrospective review is a very valuable contribution to the literature because of its comprehensive follow-up.

“Today, most patients with this type of procedure are discharged within the 23 hours, and as such, complications such as nerve palsies, chyle leaks, and surgical site infections are not apparent for the majority of patients during their hospital stay,” Dr. Pasieka said. “Many times, the true incidences are lost unless the patient re-presents to the health care system, thus introducing your bias of only those significant enough to require intervention.”

Dr. Glenn and his coauthors reported no financial disclosures.

AT THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE CENTRAL SURGICAL ASSOCIATION

Key clinical point: Lateral neck dissections for thyroid cancer are associated with high early morbidity but few long-term complications.

Major finding: The overall complication rate was 20%, however, most were transient.

Data source: Retrospective observational series of 96 patients undergoing lateral neck dissection.

Disclosures: Dr. Glenn and his coauthors reported no financial disclosures.

Disruptive medicine: 3-D printing revolution

The emergence of 3-D printing is beginning to look like a case of ‘disruptive medicine.’ Exploratory research in this area is ongoing in cardiology and orthopaedic and plastic surgery, and the experimental applications multiply daily.

Currently, 3-D printed models are being used for simulation training, preprocedural planning, development of personalized surgical equipment, and in a few cases, temporary structures for insertion in patients. As 3-D printers become cheaper, costs for their use in medicine are expected to decline

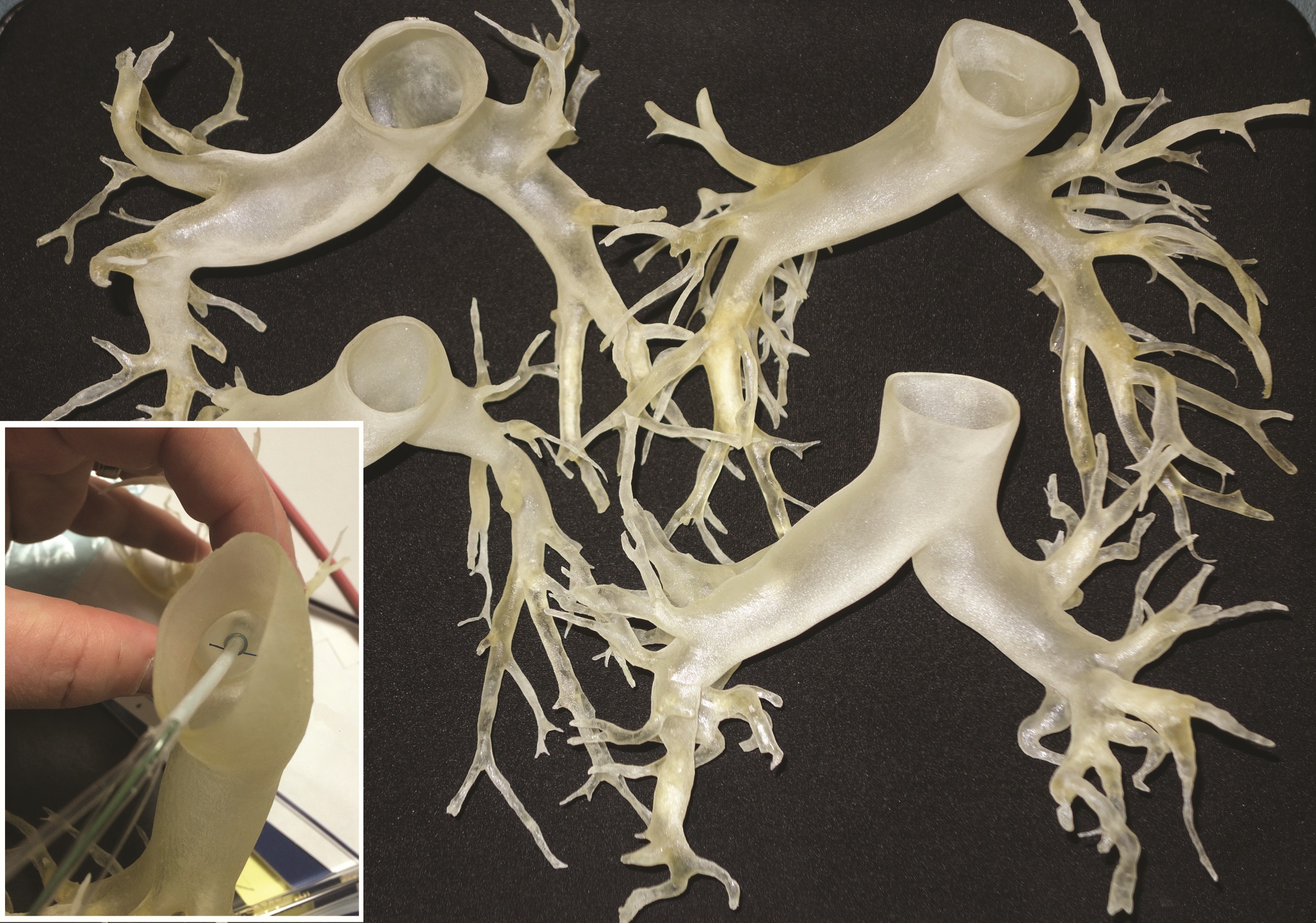

This rapidly developing technology is being applied in cardiothoracic surgery. The 3-D printing technology was used to construct flexible 3-D models of 10 human patient pulmonary arteries as part of a project to develop a new delivery catheter for regional lung chemotherapy.

Computed tomography and CT angiography in combination with software-driven segmentation techniques were used for generation and adjustment of 3-D polygon mesh to form reconstructed models of the pulmonary arteries. The reconstructed models were exported as stereolithographic data sets and further processed, according to Sergei N. Kurenov of the department of thoracic surgery, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, N.Y., and his colleagues.

How the process works

In this process, producing the anatomical pulmonary artery models required a series of steps: data acquisition from the patient CT digital data, 3-D visualization and segmentation, surface rendering and creating a 3-D polygon mesh, geometrical surface preparation – simplification, refinement, and geometry fixing, and the hollowing of an existing volume to “thicken” the walls.

Three contrast CT data sets with a 0.625-mm, 1-mm, and 2-mm slice thickness were gathered for each patient.

The scans were processed using commercial software packages. Because of the high variability of curvature and embedding in complex anatomical scenes with other vessels interference, the pulmary artery segmentation using the software tools required a clear understanding of the patient’s anatomy, which took 4-8 hours for the experienced operator, according to the researchers.

After further computer processing of the virtual reconstructed pulmonary model, it was sent to the 3-D printer, which used a rubberlike material that is elastic and semitransparent, behaving similarly to polyurethane.

The 10 unique models were successfully created with no print failures, although the original plan of using a 1-mm mural thickness proved too fragile, so the entire group was printed with a 1.5-mm wall. The design process took 8 hours from CT image to stereolithographic model, and printing required an overall total of 97 hours, according to the report published online in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery [doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.12.059].

Accurate models of individual patients’ anatomy

The physical measurements of the model were accurate for clinical purposes, with the 95% confidence levels for the 10 models demonstrating equivalence. Anatomic measurements using this process could be useful for general pulmonary artery catheter design, according to the authors. These measurements showed sufficient similarity for a design to be created that would be effective for most patients, although this finding would have to be validated with a larger sample of patients.

“While many of the measurements could have been made with software analysis of the 3-D files, some measurements were greatly facilitated by bending the model and aligning the physical catheter. These measurements represent distance beyond which a catheter might cause damage,” they added.

Biological 3-D printing of organs

Gut is a perfect beginning project for 3-D printing, Dr. John Geibel said at the 2015 American Gastroenterological Association Tech Summit, which was sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology. It has a very simple shape – just a long hollow tube. Epithelial cells grow and turn over very quickly, suggesting that a length of artificial intestine could be grown relatively quickly. And although intestine is composed of a number of distinct layers, a 3-D bioprinter would have no trouble laying down concentric circles of each one to recreate their natural morphology.

“It will take time. It will take planning. But this is going to happen,” said Dr. Geibel of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

To create a length of intestine, the print heads of a bioprinter would be loaded with cells from all of the gut layers – the serosa, the different muscle strata, the mucosa. Each would be laid down in its respective anatomic ring, supported all around by a hydrogel. The print sequence would be repeated over and over until the required length of intestine was created. From then, Dr. Geibel said, it would be only a matter of days before the cells knit themselves together so well that the gel could be dissolved and the new tissue ready for transplant.

Liver would likely be the next organ up for printing, with the ultimate goal of creating fully transplantable organs. The need is enormous, and can’t be overstated. Patients who need a new liver wait an average of 4 years before they receive one.

The liver is much more complicated than a length of gut. It is cellularly complex and highly vascularized. But liver-printing is already a reality. Bioprinted “3-D liver-in-a-dish,” created by San Diego–based Organovo, has function, if not form. The cells work together; they grow, divide, and secrete bile acids. However, they exist as a formless, nonvascular blob.

As it stands (or rather, lies) now, bioprinted liver is a perfect preclinical model – perfectly replicating how the liver would respond to drugs without any of the messy adverse events that hurt patients. But it needs some backbone, or more accurately, some matrix, in order to morph again and grow into a complete organ. A liver-shaped collagen matrix could provide the necessary frame for cells to grow in and around; tunnels through it would form pathways for a similarly engineered vasculature.

The project to create 3-D models of pulmonary arteries is one of many ongoing efforts in this field. “Going forward, this technology competes with virtual educational media for health care professionals, trainees, and patients. Complex anatomy can be visualized easily on a scale model at the operating table (rather than by manipulating a nonsterile pointing device on a computer). The [pulmonary arteries] we printed could be used in a relatively low-cost lifelike [video-assisted thoracoscopic] lobectomy trainer,” the authors stated, while acknowledging the current issue of cost and time.

Printing services were funded by an unrestricted grant from Incodema3D, which employs Dan Sammons, one of the authors of the study. The other authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

“Disruptive medicine: 3-D printing revolution” reports on an important new technology well worth surgeons’ attention. The basic process reported is a simple, but in many ways, revolutionary approach to manufacturing or assembly. 3-D printing is an additive manufacturing process, exactly the opposite from the usual subtractive process. As an example, a block of steel might be milled, drilled and machined into an engine block in a series of processes to remove material from the original piece of steel, a subtractive process.

3-D printing is an additive manufacturing process whereby materials (metal, plastic, other) are layered together to make a complex three-dimensional solid object. Working from a CAD file, material is laid down in successive layers until the entire object is created. Each layer deposited can be imagined as a thinly sliced horizontal cross-section of the eventual object. As such, 3-D printing is really a stack of 2-D prints. The technique was invented by Charles Hull in 1986 and is revolutionizing prototyping and, in some cases, manufacturing. Applications have included prototyping, metal casting, architectural design and building, and in 3-D design and visualization: this application is well-demonstrated in the medical application of pulmonary artery reconstruction outlined in this article. In this case, complex anatomy can be easily visualized on a solid full-scale model of the pulmonary vasculature, and treatment plans more easily formulated and even modeled.

An extensive, thoughtful discussion of medical 3-D printing can be found in the November 24, 2014 The New Yorker article entitled “Print Thyself: How 3-D printing is revolutionizing medicine.” Other medical applications described include 3-D reconstruction in complex craniofacial repairs, modeling of abnormalities in the tracheobronchial tree to design surgical strategies to manage airway stenosis, and in reconstructive modeling for complex traumatic injuries in bone and soft tissue.

Beyond such applications, concepts have evolved to areas of 3-D printing using mixtures of cells and matrix as an approach to the engineering and additive assembly of complex tissues, and even organs. Thus, functional organs might someday be produced; a massive step beyond simple prototyping.

As in many areas of science and technology, the field moves quickly. The March 20, 2015 issue of Science published a report on “Continuous liquid interface production (CLIP) of 3D objects.” This true 3-D printing process is up to 100 times faster than current technologies and is compatible with producing objects from soft elastic materials, ceramics and biologics! More to come…

Thomas M. Krummel, MD, FACS, is the Emile Holman Professor and Chair, Department of Surgery at Stanford University and the Co-Director, Biodesign Innovation Program at Stanford. He is also a member of the Board of Directors of the Fogarty Institute for Innovation.

“Disruptive medicine: 3-D printing revolution” reports on an important new technology well worth surgeons’ attention. The basic process reported is a simple, but in many ways, revolutionary approach to manufacturing or assembly. 3-D printing is an additive manufacturing process, exactly the opposite from the usual subtractive process. As an example, a block of steel might be milled, drilled and machined into an engine block in a series of processes to remove material from the original piece of steel, a subtractive process.

3-D printing is an additive manufacturing process whereby materials (metal, plastic, other) are layered together to make a complex three-dimensional solid object. Working from a CAD file, material is laid down in successive layers until the entire object is created. Each layer deposited can be imagined as a thinly sliced horizontal cross-section of the eventual object. As such, 3-D printing is really a stack of 2-D prints. The technique was invented by Charles Hull in 1986 and is revolutionizing prototyping and, in some cases, manufacturing. Applications have included prototyping, metal casting, architectural design and building, and in 3-D design and visualization: this application is well-demonstrated in the medical application of pulmonary artery reconstruction outlined in this article. In this case, complex anatomy can be easily visualized on a solid full-scale model of the pulmonary vasculature, and treatment plans more easily formulated and even modeled.

An extensive, thoughtful discussion of medical 3-D printing can be found in the November 24, 2014 The New Yorker article entitled “Print Thyself: How 3-D printing is revolutionizing medicine.” Other medical applications described include 3-D reconstruction in complex craniofacial repairs, modeling of abnormalities in the tracheobronchial tree to design surgical strategies to manage airway stenosis, and in reconstructive modeling for complex traumatic injuries in bone and soft tissue.

Beyond such applications, concepts have evolved to areas of 3-D printing using mixtures of cells and matrix as an approach to the engineering and additive assembly of complex tissues, and even organs. Thus, functional organs might someday be produced; a massive step beyond simple prototyping.

As in many areas of science and technology, the field moves quickly. The March 20, 2015 issue of Science published a report on “Continuous liquid interface production (CLIP) of 3D objects.” This true 3-D printing process is up to 100 times faster than current technologies and is compatible with producing objects from soft elastic materials, ceramics and biologics! More to come…

Thomas M. Krummel, MD, FACS, is the Emile Holman Professor and Chair, Department of Surgery at Stanford University and the Co-Director, Biodesign Innovation Program at Stanford. He is also a member of the Board of Directors of the Fogarty Institute for Innovation.

“Disruptive medicine: 3-D printing revolution” reports on an important new technology well worth surgeons’ attention. The basic process reported is a simple, but in many ways, revolutionary approach to manufacturing or assembly. 3-D printing is an additive manufacturing process, exactly the opposite from the usual subtractive process. As an example, a block of steel might be milled, drilled and machined into an engine block in a series of processes to remove material from the original piece of steel, a subtractive process.

3-D printing is an additive manufacturing process whereby materials (metal, plastic, other) are layered together to make a complex three-dimensional solid object. Working from a CAD file, material is laid down in successive layers until the entire object is created. Each layer deposited can be imagined as a thinly sliced horizontal cross-section of the eventual object. As such, 3-D printing is really a stack of 2-D prints. The technique was invented by Charles Hull in 1986 and is revolutionizing prototyping and, in some cases, manufacturing. Applications have included prototyping, metal casting, architectural design and building, and in 3-D design and visualization: this application is well-demonstrated in the medical application of pulmonary artery reconstruction outlined in this article. In this case, complex anatomy can be easily visualized on a solid full-scale model of the pulmonary vasculature, and treatment plans more easily formulated and even modeled.

An extensive, thoughtful discussion of medical 3-D printing can be found in the November 24, 2014 The New Yorker article entitled “Print Thyself: How 3-D printing is revolutionizing medicine.” Other medical applications described include 3-D reconstruction in complex craniofacial repairs, modeling of abnormalities in the tracheobronchial tree to design surgical strategies to manage airway stenosis, and in reconstructive modeling for complex traumatic injuries in bone and soft tissue.

Beyond such applications, concepts have evolved to areas of 3-D printing using mixtures of cells and matrix as an approach to the engineering and additive assembly of complex tissues, and even organs. Thus, functional organs might someday be produced; a massive step beyond simple prototyping.

As in many areas of science and technology, the field moves quickly. The March 20, 2015 issue of Science published a report on “Continuous liquid interface production (CLIP) of 3D objects.” This true 3-D printing process is up to 100 times faster than current technologies and is compatible with producing objects from soft elastic materials, ceramics and biologics! More to come…

Thomas M. Krummel, MD, FACS, is the Emile Holman Professor and Chair, Department of Surgery at Stanford University and the Co-Director, Biodesign Innovation Program at Stanford. He is also a member of the Board of Directors of the Fogarty Institute for Innovation.

The emergence of 3-D printing is beginning to look like a case of ‘disruptive medicine.’ Exploratory research in this area is ongoing in cardiology and orthopaedic and plastic surgery, and the experimental applications multiply daily.

Currently, 3-D printed models are being used for simulation training, preprocedural planning, development of personalized surgical equipment, and in a few cases, temporary structures for insertion in patients. As 3-D printers become cheaper, costs for their use in medicine are expected to decline

This rapidly developing technology is being applied in cardiothoracic surgery. The 3-D printing technology was used to construct flexible 3-D models of 10 human patient pulmonary arteries as part of a project to develop a new delivery catheter for regional lung chemotherapy.

Computed tomography and CT angiography in combination with software-driven segmentation techniques were used for generation and adjustment of 3-D polygon mesh to form reconstructed models of the pulmonary arteries. The reconstructed models were exported as stereolithographic data sets and further processed, according to Sergei N. Kurenov of the department of thoracic surgery, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, N.Y., and his colleagues.

How the process works

In this process, producing the anatomical pulmonary artery models required a series of steps: data acquisition from the patient CT digital data, 3-D visualization and segmentation, surface rendering and creating a 3-D polygon mesh, geometrical surface preparation – simplification, refinement, and geometry fixing, and the hollowing of an existing volume to “thicken” the walls.

Three contrast CT data sets with a 0.625-mm, 1-mm, and 2-mm slice thickness were gathered for each patient.

The scans were processed using commercial software packages. Because of the high variability of curvature and embedding in complex anatomical scenes with other vessels interference, the pulmary artery segmentation using the software tools required a clear understanding of the patient’s anatomy, which took 4-8 hours for the experienced operator, according to the researchers.

After further computer processing of the virtual reconstructed pulmonary model, it was sent to the 3-D printer, which used a rubberlike material that is elastic and semitransparent, behaving similarly to polyurethane.

The 10 unique models were successfully created with no print failures, although the original plan of using a 1-mm mural thickness proved too fragile, so the entire group was printed with a 1.5-mm wall. The design process took 8 hours from CT image to stereolithographic model, and printing required an overall total of 97 hours, according to the report published online in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery [doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.12.059].

Accurate models of individual patients’ anatomy

The physical measurements of the model were accurate for clinical purposes, with the 95% confidence levels for the 10 models demonstrating equivalence. Anatomic measurements using this process could be useful for general pulmonary artery catheter design, according to the authors. These measurements showed sufficient similarity for a design to be created that would be effective for most patients, although this finding would have to be validated with a larger sample of patients.

“While many of the measurements could have been made with software analysis of the 3-D files, some measurements were greatly facilitated by bending the model and aligning the physical catheter. These measurements represent distance beyond which a catheter might cause damage,” they added.

Biological 3-D printing of organs

Gut is a perfect beginning project for 3-D printing, Dr. John Geibel said at the 2015 American Gastroenterological Association Tech Summit, which was sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology. It has a very simple shape – just a long hollow tube. Epithelial cells grow and turn over very quickly, suggesting that a length of artificial intestine could be grown relatively quickly. And although intestine is composed of a number of distinct layers, a 3-D bioprinter would have no trouble laying down concentric circles of each one to recreate their natural morphology.

“It will take time. It will take planning. But this is going to happen,” said Dr. Geibel of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

To create a length of intestine, the print heads of a bioprinter would be loaded with cells from all of the gut layers – the serosa, the different muscle strata, the mucosa. Each would be laid down in its respective anatomic ring, supported all around by a hydrogel. The print sequence would be repeated over and over until the required length of intestine was created. From then, Dr. Geibel said, it would be only a matter of days before the cells knit themselves together so well that the gel could be dissolved and the new tissue ready for transplant.

Liver would likely be the next organ up for printing, with the ultimate goal of creating fully transplantable organs. The need is enormous, and can’t be overstated. Patients who need a new liver wait an average of 4 years before they receive one.

The liver is much more complicated than a length of gut. It is cellularly complex and highly vascularized. But liver-printing is already a reality. Bioprinted “3-D liver-in-a-dish,” created by San Diego–based Organovo, has function, if not form. The cells work together; they grow, divide, and secrete bile acids. However, they exist as a formless, nonvascular blob.

As it stands (or rather, lies) now, bioprinted liver is a perfect preclinical model – perfectly replicating how the liver would respond to drugs without any of the messy adverse events that hurt patients. But it needs some backbone, or more accurately, some matrix, in order to morph again and grow into a complete organ. A liver-shaped collagen matrix could provide the necessary frame for cells to grow in and around; tunnels through it would form pathways for a similarly engineered vasculature.

The project to create 3-D models of pulmonary arteries is one of many ongoing efforts in this field. “Going forward, this technology competes with virtual educational media for health care professionals, trainees, and patients. Complex anatomy can be visualized easily on a scale model at the operating table (rather than by manipulating a nonsterile pointing device on a computer). The [pulmonary arteries] we printed could be used in a relatively low-cost lifelike [video-assisted thoracoscopic] lobectomy trainer,” the authors stated, while acknowledging the current issue of cost and time.

Printing services were funded by an unrestricted grant from Incodema3D, which employs Dan Sammons, one of the authors of the study. The other authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

The emergence of 3-D printing is beginning to look like a case of ‘disruptive medicine.’ Exploratory research in this area is ongoing in cardiology and orthopaedic and plastic surgery, and the experimental applications multiply daily.

Currently, 3-D printed models are being used for simulation training, preprocedural planning, development of personalized surgical equipment, and in a few cases, temporary structures for insertion in patients. As 3-D printers become cheaper, costs for their use in medicine are expected to decline

This rapidly developing technology is being applied in cardiothoracic surgery. The 3-D printing technology was used to construct flexible 3-D models of 10 human patient pulmonary arteries as part of a project to develop a new delivery catheter for regional lung chemotherapy.

Computed tomography and CT angiography in combination with software-driven segmentation techniques were used for generation and adjustment of 3-D polygon mesh to form reconstructed models of the pulmonary arteries. The reconstructed models were exported as stereolithographic data sets and further processed, according to Sergei N. Kurenov of the department of thoracic surgery, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, N.Y., and his colleagues.

How the process works

In this process, producing the anatomical pulmonary artery models required a series of steps: data acquisition from the patient CT digital data, 3-D visualization and segmentation, surface rendering and creating a 3-D polygon mesh, geometrical surface preparation – simplification, refinement, and geometry fixing, and the hollowing of an existing volume to “thicken” the walls.

Three contrast CT data sets with a 0.625-mm, 1-mm, and 2-mm slice thickness were gathered for each patient.

The scans were processed using commercial software packages. Because of the high variability of curvature and embedding in complex anatomical scenes with other vessels interference, the pulmary artery segmentation using the software tools required a clear understanding of the patient’s anatomy, which took 4-8 hours for the experienced operator, according to the researchers.

After further computer processing of the virtual reconstructed pulmonary model, it was sent to the 3-D printer, which used a rubberlike material that is elastic and semitransparent, behaving similarly to polyurethane.

The 10 unique models were successfully created with no print failures, although the original plan of using a 1-mm mural thickness proved too fragile, so the entire group was printed with a 1.5-mm wall. The design process took 8 hours from CT image to stereolithographic model, and printing required an overall total of 97 hours, according to the report published online in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery [doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.12.059].

Accurate models of individual patients’ anatomy

The physical measurements of the model were accurate for clinical purposes, with the 95% confidence levels for the 10 models demonstrating equivalence. Anatomic measurements using this process could be useful for general pulmonary artery catheter design, according to the authors. These measurements showed sufficient similarity for a design to be created that would be effective for most patients, although this finding would have to be validated with a larger sample of patients.

“While many of the measurements could have been made with software analysis of the 3-D files, some measurements were greatly facilitated by bending the model and aligning the physical catheter. These measurements represent distance beyond which a catheter might cause damage,” they added.

Biological 3-D printing of organs

Gut is a perfect beginning project for 3-D printing, Dr. John Geibel said at the 2015 American Gastroenterological Association Tech Summit, which was sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology. It has a very simple shape – just a long hollow tube. Epithelial cells grow and turn over very quickly, suggesting that a length of artificial intestine could be grown relatively quickly. And although intestine is composed of a number of distinct layers, a 3-D bioprinter would have no trouble laying down concentric circles of each one to recreate their natural morphology.

“It will take time. It will take planning. But this is going to happen,” said Dr. Geibel of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

To create a length of intestine, the print heads of a bioprinter would be loaded with cells from all of the gut layers – the serosa, the different muscle strata, the mucosa. Each would be laid down in its respective anatomic ring, supported all around by a hydrogel. The print sequence would be repeated over and over until the required length of intestine was created. From then, Dr. Geibel said, it would be only a matter of days before the cells knit themselves together so well that the gel could be dissolved and the new tissue ready for transplant.

Liver would likely be the next organ up for printing, with the ultimate goal of creating fully transplantable organs. The need is enormous, and can’t be overstated. Patients who need a new liver wait an average of 4 years before they receive one.

The liver is much more complicated than a length of gut. It is cellularly complex and highly vascularized. But liver-printing is already a reality. Bioprinted “3-D liver-in-a-dish,” created by San Diego–based Organovo, has function, if not form. The cells work together; they grow, divide, and secrete bile acids. However, they exist as a formless, nonvascular blob.

As it stands (or rather, lies) now, bioprinted liver is a perfect preclinical model – perfectly replicating how the liver would respond to drugs without any of the messy adverse events that hurt patients. But it needs some backbone, or more accurately, some matrix, in order to morph again and grow into a complete organ. A liver-shaped collagen matrix could provide the necessary frame for cells to grow in and around; tunnels through it would form pathways for a similarly engineered vasculature.

The project to create 3-D models of pulmonary arteries is one of many ongoing efforts in this field. “Going forward, this technology competes with virtual educational media for health care professionals, trainees, and patients. Complex anatomy can be visualized easily on a scale model at the operating table (rather than by manipulating a nonsterile pointing device on a computer). The [pulmonary arteries] we printed could be used in a relatively low-cost lifelike [video-assisted thoracoscopic] lobectomy trainer,” the authors stated, while acknowledging the current issue of cost and time.

Printing services were funded by an unrestricted grant from Incodema3D, which employs Dan Sammons, one of the authors of the study. The other authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

Fibrin sealant patch cleared for use in liver surgery

The Food and Drug Administration has expanded the indication of Evarrest (fibrin sealant) to include use as an adjunct to hemostasis for control of bleeding during adult liver surgery.

The drug also has been indicated for use with manual compression as an adjunct to hemostasis for soft-tissue bleeding during open retroperitoneal, intra-abdominal, pelvic, and noncardiac thoracic surgery. Evarrest has not yet been approved for pediatric use.

Evarrest is made by Ethicon Biosurgery, a division of Ethicon.

The Food and Drug Administration has expanded the indication of Evarrest (fibrin sealant) to include use as an adjunct to hemostasis for control of bleeding during adult liver surgery.

The drug also has been indicated for use with manual compression as an adjunct to hemostasis for soft-tissue bleeding during open retroperitoneal, intra-abdominal, pelvic, and noncardiac thoracic surgery. Evarrest has not yet been approved for pediatric use.

Evarrest is made by Ethicon Biosurgery, a division of Ethicon.

The Food and Drug Administration has expanded the indication of Evarrest (fibrin sealant) to include use as an adjunct to hemostasis for control of bleeding during adult liver surgery.

The drug also has been indicated for use with manual compression as an adjunct to hemostasis for soft-tissue bleeding during open retroperitoneal, intra-abdominal, pelvic, and noncardiac thoracic surgery. Evarrest has not yet been approved for pediatric use.

Evarrest is made by Ethicon Biosurgery, a division of Ethicon.

Low mortality, good outcomes in octogenarian AAA repair sparks QOL vs. utility debate

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in patients 80 years and older can be performed safely and with good medium-term survival rates, a prospective single-site study has shown.

Perioperative mortality in elective and emergent AAA repair for octogenarians was 2% and 35%, respectively, with a median survival rate of 19 months in both groups.

According to these data, “Patients shouldn’t be turned down for aneurysm repair on the basis of their age alone,” Dr. Christopher M. Lamb, a vascular surgery fellow at the University of California Davis Medical Center in Sacramento, said during a presentation at this year’s Southern Association for Vascular Surgery annual meeting. “However, whether should we be doing these procedures is a different question, and I don’t think these data allow us to answer that question properly.”

Dr. Lamb and his colleagues reviewed the records of 847 consecutive patients aged 80 years or older, seen between April 2005 and February 2014 for any type of AAA repair. Cases were sorted according to whether they were elective, ruptured, or urgent but unruptured. A total of 226 patients met the study’s age criteria, there were nearly seven men for every woman, all with a median age of 83 years.

Of the elective AAA repair arm of the study, 131 patients (116 men) with a median age of 82 years had an endovascular repair, while the rest underwent open surgical repair. The combined 30-day mortality rate for these patients was 2.3%, with no significant difference between either the endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) or the open surgical repair (OSR) patients (1.9% vs. 4.2%; P = .458). The median survival of all elective repair patients was 19 months (interquartile range, 10-35), with no difference seen between the two groups (P = .113)

Of the 65 patients (53 men) with ruptured AAA, the median age was 83 years. A third had open repair (32.3%), while the rest had EVAR. The combined 30-day mortality rate was 35.4% but was significantly higher after OSR (52.4% vs. 27.3%; P = .048). The median survival rate was 6 months (IQR, 6-42) when 30-day mortality rates were excluded. The median survival rates in patients who lived longer than 30 days was significantly higher in OSR patients (42.5 months vs. 11 months; P = .019).

Of the 23 men and 7 women with symptomatic but unruptured AAA, all but 1 had EVAR. At 30 days, there was one diverticular perforation-related postoperative death in the EVAR group, which had a median survival rate of 29 months. There being only a single patient in the OSR group obviated a comparative median survival rate analysis.

A subanalysis of the final 20 months of the study showed that 41% of octogenarians seeking any type of AAA repair at the site were rejected (48 rejections vs. 69 repairs). Those who were rejected for repair tended to be older, with a median age of 86 years vs. 83 years for patients who underwent repair (P = .0004).

Dr. Lamb noted that although the findings demonstrate acceptable overall safety rates for the entire cohort, without a control group of patients that did not have AAA repair, it would be hard to draw a definite conclusion about the utility of the findings, and that more data was warranted; however, the potential for limited long-term survival with what previous reports have suggested may include “a reduced quality of life for a good part of it, possibly raises the question that these patients should be treated conservatively, more often.”

The rejection rate data prompted the presentation’s discussant, Dr. William D. Jordan Jr., section chief of vascular surgery at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and the presentation’s discussant, to challenge the findings and asked whether a single surgeon selected the patients.

“You said there is not a selection bias in your study, but I beg to differ. Perhaps all these kinds of studies have a selection bias, and I believe they should. We should select the appropriate patients for the appropriate procedure at the appropriate time, with the appropriate expectation of outcome. Bias in this setting may be seen as good,” Dr. Jordan said.

Dr. Lamb responded that the treatment algorithm at the site for all patients with a confirmed AAA of 5.5 cm or greater included CT imaging that is reviewed by a multidisciplinary team comprising vascular surgeons and interventional radiologists, who then evaluated the patients according to their physiology and anatomy, as well as their comorbidities, with the intention that whenever possible, EVAR rather than open repair would be performed.

As to whether there was a bias toward not repairing AAA in older patients, Dr. Lamb said it was incumbent on any health system to evaluate a procedure’s cost effectiveness, but that, “the life expectancy of a vascular patient is often more limited than I think we’d like to believe ... we don’t know what the natural history of these patients’ life expectancy is. We don’t know from these data what the cause of death was, but anecdotally, we didn’t see hundreds of patients return with ruptured aneurysms after an EVAR.”

“I would truly like to see how many [of these patients] who make it out of the hospital return to normal living within six months,” Dr. Samuel R. Money, chair of surgery at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz., said in an interview following the presentation. “At some point, the question becomes ‘Can we afford to spend $100,000 dollars to keep a 90-year-old patient alive for 6 more months?’ Can this society sustain the cost of that?”

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

This discussion is provocative and raises some interesting points. Obviously cost effectiveness considerations are important, and our country does not have unlimited funds to spend on medical care. And perhaps there are some elderly and frail individuals who should not have their AAAs repaired electively because the risk of rupture during the patients’ remaining months or years of life is small.

This is particularly true if the patient’s AAA is less than 7 cm and his or her anatomy and condition are unsuitable for an easy repair. However, if the AAA is large and threatening, and the patient has the possibility of living several years, elective repair is justified and reasonable – especially if it can be accomplished endovascularly. As someone who is near 80 [years old], I could not feel more strongly about this, and I would maintain this view if I were near 90 and healthy.

|

Dr. Frank J. Veith |

I hold the same view even more strongly regarding a ruptured AAA. In this setting, the alternative management is nontreatment, which is uniformly fatal. The common term “palliative treatment” for such nontreatment is a misleading misnomer. No sane, reasonably healthy elderly patient would knowingly choose such nontreatment when a good alternative with well over an even chance of living a lot longer is offered. That good alternative – again especially if it can be performed endovascularly – should be offered, and our health system should pay for it and compensate by saving money on unnecessary SFA [superficial femoral artery] stents and carotid procedures.

Dr. Frank J. Veith is professor of surgery at New York University Medical Center and the Cleveland Clinic and is an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

This discussion is provocative and raises some interesting points. Obviously cost effectiveness considerations are important, and our country does not have unlimited funds to spend on medical care. And perhaps there are some elderly and frail individuals who should not have their AAAs repaired electively because the risk of rupture during the patients’ remaining months or years of life is small.

This is particularly true if the patient’s AAA is less than 7 cm and his or her anatomy and condition are unsuitable for an easy repair. However, if the AAA is large and threatening, and the patient has the possibility of living several years, elective repair is justified and reasonable – especially if it can be accomplished endovascularly. As someone who is near 80 [years old], I could not feel more strongly about this, and I would maintain this view if I were near 90 and healthy.

|

Dr. Frank J. Veith |

I hold the same view even more strongly regarding a ruptured AAA. In this setting, the alternative management is nontreatment, which is uniformly fatal. The common term “palliative treatment” for such nontreatment is a misleading misnomer. No sane, reasonably healthy elderly patient would knowingly choose such nontreatment when a good alternative with well over an even chance of living a lot longer is offered. That good alternative – again especially if it can be performed endovascularly – should be offered, and our health system should pay for it and compensate by saving money on unnecessary SFA [superficial femoral artery] stents and carotid procedures.

Dr. Frank J. Veith is professor of surgery at New York University Medical Center and the Cleveland Clinic and is an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

This discussion is provocative and raises some interesting points. Obviously cost effectiveness considerations are important, and our country does not have unlimited funds to spend on medical care. And perhaps there are some elderly and frail individuals who should not have their AAAs repaired electively because the risk of rupture during the patients’ remaining months or years of life is small.

This is particularly true if the patient’s AAA is less than 7 cm and his or her anatomy and condition are unsuitable for an easy repair. However, if the AAA is large and threatening, and the patient has the possibility of living several years, elective repair is justified and reasonable – especially if it can be accomplished endovascularly. As someone who is near 80 [years old], I could not feel more strongly about this, and I would maintain this view if I were near 90 and healthy.

|

Dr. Frank J. Veith |

I hold the same view even more strongly regarding a ruptured AAA. In this setting, the alternative management is nontreatment, which is uniformly fatal. The common term “palliative treatment” for such nontreatment is a misleading misnomer. No sane, reasonably healthy elderly patient would knowingly choose such nontreatment when a good alternative with well over an even chance of living a lot longer is offered. That good alternative – again especially if it can be performed endovascularly – should be offered, and our health system should pay for it and compensate by saving money on unnecessary SFA [superficial femoral artery] stents and carotid procedures.

Dr. Frank J. Veith is professor of surgery at New York University Medical Center and the Cleveland Clinic and is an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in patients 80 years and older can be performed safely and with good medium-term survival rates, a prospective single-site study has shown.

Perioperative mortality in elective and emergent AAA repair for octogenarians was 2% and 35%, respectively, with a median survival rate of 19 months in both groups.

According to these data, “Patients shouldn’t be turned down for aneurysm repair on the basis of their age alone,” Dr. Christopher M. Lamb, a vascular surgery fellow at the University of California Davis Medical Center in Sacramento, said during a presentation at this year’s Southern Association for Vascular Surgery annual meeting. “However, whether should we be doing these procedures is a different question, and I don’t think these data allow us to answer that question properly.”

Dr. Lamb and his colleagues reviewed the records of 847 consecutive patients aged 80 years or older, seen between April 2005 and February 2014 for any type of AAA repair. Cases were sorted according to whether they were elective, ruptured, or urgent but unruptured. A total of 226 patients met the study’s age criteria, there were nearly seven men for every woman, all with a median age of 83 years.

Of the elective AAA repair arm of the study, 131 patients (116 men) with a median age of 82 years had an endovascular repair, while the rest underwent open surgical repair. The combined 30-day mortality rate for these patients was 2.3%, with no significant difference between either the endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) or the open surgical repair (OSR) patients (1.9% vs. 4.2%; P = .458). The median survival of all elective repair patients was 19 months (interquartile range, 10-35), with no difference seen between the two groups (P = .113)

Of the 65 patients (53 men) with ruptured AAA, the median age was 83 years. A third had open repair (32.3%), while the rest had EVAR. The combined 30-day mortality rate was 35.4% but was significantly higher after OSR (52.4% vs. 27.3%; P = .048). The median survival rate was 6 months (IQR, 6-42) when 30-day mortality rates were excluded. The median survival rates in patients who lived longer than 30 days was significantly higher in OSR patients (42.5 months vs. 11 months; P = .019).

Of the 23 men and 7 women with symptomatic but unruptured AAA, all but 1 had EVAR. At 30 days, there was one diverticular perforation-related postoperative death in the EVAR group, which had a median survival rate of 29 months. There being only a single patient in the OSR group obviated a comparative median survival rate analysis.

A subanalysis of the final 20 months of the study showed that 41% of octogenarians seeking any type of AAA repair at the site were rejected (48 rejections vs. 69 repairs). Those who were rejected for repair tended to be older, with a median age of 86 years vs. 83 years for patients who underwent repair (P = .0004).

Dr. Lamb noted that although the findings demonstrate acceptable overall safety rates for the entire cohort, without a control group of patients that did not have AAA repair, it would be hard to draw a definite conclusion about the utility of the findings, and that more data was warranted; however, the potential for limited long-term survival with what previous reports have suggested may include “a reduced quality of life for a good part of it, possibly raises the question that these patients should be treated conservatively, more often.”

The rejection rate data prompted the presentation’s discussant, Dr. William D. Jordan Jr., section chief of vascular surgery at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and the presentation’s discussant, to challenge the findings and asked whether a single surgeon selected the patients.

“You said there is not a selection bias in your study, but I beg to differ. Perhaps all these kinds of studies have a selection bias, and I believe they should. We should select the appropriate patients for the appropriate procedure at the appropriate time, with the appropriate expectation of outcome. Bias in this setting may be seen as good,” Dr. Jordan said.

Dr. Lamb responded that the treatment algorithm at the site for all patients with a confirmed AAA of 5.5 cm or greater included CT imaging that is reviewed by a multidisciplinary team comprising vascular surgeons and interventional radiologists, who then evaluated the patients according to their physiology and anatomy, as well as their comorbidities, with the intention that whenever possible, EVAR rather than open repair would be performed.

As to whether there was a bias toward not repairing AAA in older patients, Dr. Lamb said it was incumbent on any health system to evaluate a procedure’s cost effectiveness, but that, “the life expectancy of a vascular patient is often more limited than I think we’d like to believe ... we don’t know what the natural history of these patients’ life expectancy is. We don’t know from these data what the cause of death was, but anecdotally, we didn’t see hundreds of patients return with ruptured aneurysms after an EVAR.”

“I would truly like to see how many [of these patients] who make it out of the hospital return to normal living within six months,” Dr. Samuel R. Money, chair of surgery at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz., said in an interview following the presentation. “At some point, the question becomes ‘Can we afford to spend $100,000 dollars to keep a 90-year-old patient alive for 6 more months?’ Can this society sustain the cost of that?”

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – Abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in patients 80 years and older can be performed safely and with good medium-term survival rates, a prospective single-site study has shown.

Perioperative mortality in elective and emergent AAA repair for octogenarians was 2% and 35%, respectively, with a median survival rate of 19 months in both groups.

According to these data, “Patients shouldn’t be turned down for aneurysm repair on the basis of their age alone,” Dr. Christopher M. Lamb, a vascular surgery fellow at the University of California Davis Medical Center in Sacramento, said during a presentation at this year’s Southern Association for Vascular Surgery annual meeting. “However, whether should we be doing these procedures is a different question, and I don’t think these data allow us to answer that question properly.”

Dr. Lamb and his colleagues reviewed the records of 847 consecutive patients aged 80 years or older, seen between April 2005 and February 2014 for any type of AAA repair. Cases were sorted according to whether they were elective, ruptured, or urgent but unruptured. A total of 226 patients met the study’s age criteria, there were nearly seven men for every woman, all with a median age of 83 years.

Of the elective AAA repair arm of the study, 131 patients (116 men) with a median age of 82 years had an endovascular repair, while the rest underwent open surgical repair. The combined 30-day mortality rate for these patients was 2.3%, with no significant difference between either the endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) or the open surgical repair (OSR) patients (1.9% vs. 4.2%; P = .458). The median survival of all elective repair patients was 19 months (interquartile range, 10-35), with no difference seen between the two groups (P = .113)

Of the 65 patients (53 men) with ruptured AAA, the median age was 83 years. A third had open repair (32.3%), while the rest had EVAR. The combined 30-day mortality rate was 35.4% but was significantly higher after OSR (52.4% vs. 27.3%; P = .048). The median survival rate was 6 months (IQR, 6-42) when 30-day mortality rates were excluded. The median survival rates in patients who lived longer than 30 days was significantly higher in OSR patients (42.5 months vs. 11 months; P = .019).

Of the 23 men and 7 women with symptomatic but unruptured AAA, all but 1 had EVAR. At 30 days, there was one diverticular perforation-related postoperative death in the EVAR group, which had a median survival rate of 29 months. There being only a single patient in the OSR group obviated a comparative median survival rate analysis.

A subanalysis of the final 20 months of the study showed that 41% of octogenarians seeking any type of AAA repair at the site were rejected (48 rejections vs. 69 repairs). Those who were rejected for repair tended to be older, with a median age of 86 years vs. 83 years for patients who underwent repair (P = .0004).

Dr. Lamb noted that although the findings demonstrate acceptable overall safety rates for the entire cohort, without a control group of patients that did not have AAA repair, it would be hard to draw a definite conclusion about the utility of the findings, and that more data was warranted; however, the potential for limited long-term survival with what previous reports have suggested may include “a reduced quality of life for a good part of it, possibly raises the question that these patients should be treated conservatively, more often.”

The rejection rate data prompted the presentation’s discussant, Dr. William D. Jordan Jr., section chief of vascular surgery at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and the presentation’s discussant, to challenge the findings and asked whether a single surgeon selected the patients.

“You said there is not a selection bias in your study, but I beg to differ. Perhaps all these kinds of studies have a selection bias, and I believe they should. We should select the appropriate patients for the appropriate procedure at the appropriate time, with the appropriate expectation of outcome. Bias in this setting may be seen as good,” Dr. Jordan said.

Dr. Lamb responded that the treatment algorithm at the site for all patients with a confirmed AAA of 5.5 cm or greater included CT imaging that is reviewed by a multidisciplinary team comprising vascular surgeons and interventional radiologists, who then evaluated the patients according to their physiology and anatomy, as well as their comorbidities, with the intention that whenever possible, EVAR rather than open repair would be performed.

As to whether there was a bias toward not repairing AAA in older patients, Dr. Lamb said it was incumbent on any health system to evaluate a procedure’s cost effectiveness, but that, “the life expectancy of a vascular patient is often more limited than I think we’d like to believe ... we don’t know what the natural history of these patients’ life expectancy is. We don’t know from these data what the cause of death was, but anecdotally, we didn’t see hundreds of patients return with ruptured aneurysms after an EVAR.”

“I would truly like to see how many [of these patients] who make it out of the hospital return to normal living within six months,” Dr. Samuel R. Money, chair of surgery at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz., said in an interview following the presentation. “At some point, the question becomes ‘Can we afford to spend $100,000 dollars to keep a 90-year-old patient alive for 6 more months?’ Can this society sustain the cost of that?”

[email protected]

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT THE SAVS ANNUAL MEETING 2015

Key clinical point: EVAR and OSR outcomes for AAA were both shown safe and effective at 30 days and 6 months in patients 80 years and older.

Major finding: Perioperative mortality in elective and emergent AAA repair was 2% and 35%, respectively, with a median survival rate of 19 months in both groups.

Data source: Prospective study of 847 consecutive AAA-repair patients at a single site between May 2005 and February 2014.

Disclosures: Dr. Lamb did not have any relevant disclosures.

Four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy linked to less fatigue

Single-port and four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy were associated with similar self-reported pain scores and physiologic measures of recovery, according to a double-blinded, randomized trial published online in the Journal of the American College of Surgery.

But patients in the four-port arm reported significantly less fatigue (P = .009), and 40% needed postoperative narcotics, compared with 60% of patients who underwent single-port laparoscopy (P = .056), reported Dr. Juliane Bingener and her associates at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, N.Y.

“The data from this study may assist patients and surgeons in the discussion on how to choose a procedure,” said the researchers. “If fast postoperative recovery is the most important goal, four-port cholecystectomy may be more advantageous than single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy. If cosmesis is the most important factor, single-port entry may be chosen” (J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2015 March 2 [doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.02.022]).

The study comprised 110 patients, of whom half underwent single-port and half underwent four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy, all performed by the same surgeon. The primary outcome was patient-reported pain 7 days after the procedure, as measured by the visual analog scale (VAS). In all, 81% of patients were female, and median age was 47.5 years, the researchers reported.

Postoperative VAS pain scores rose significantly for both groups, compared with baseline, but did not significantly differ between the groups, said the investigators (single-port: 4.2 ± 2.4; four-port: 4.2 ± 2.2; P = .83). Cytokine levels and variations in heart rate also were similar between the groups.

However, measures of fatigue on the linear analog self-assessment were better with four-port entry, compared with the single-port approach (3.1 ± 2.1, versus 4.2 ± 2.2, respectively; P = .009), the investigators reported. And 49% of patients in the single-port group reported severe fatigue (a score greater than 5), compared with only 22% of the four-port group (P = .005).

“While this could be due to alpha-error, the fact that the group with the higher fatigue levels (single port) also seemed to be taking more oral narcotic pain medication before discharge … while maintaining similar pain scores in the postoperative period and otherwise having a similar distribution of factors affecting postoperative pain … suggests that the narcotic pain medication may have indeed had an influence on the fatigue scores,” the investigators said.

The National Institutes of Health and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences funded the research. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Single-port and four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy were associated with similar self-reported pain scores and physiologic measures of recovery, according to a double-blinded, randomized trial published online in the Journal of the American College of Surgery.

But patients in the four-port arm reported significantly less fatigue (P = .009), and 40% needed postoperative narcotics, compared with 60% of patients who underwent single-port laparoscopy (P = .056), reported Dr. Juliane Bingener and her associates at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, N.Y.

“The data from this study may assist patients and surgeons in the discussion on how to choose a procedure,” said the researchers. “If fast postoperative recovery is the most important goal, four-port cholecystectomy may be more advantageous than single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy. If cosmesis is the most important factor, single-port entry may be chosen” (J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2015 March 2 [doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.02.022]).

The study comprised 110 patients, of whom half underwent single-port and half underwent four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy, all performed by the same surgeon. The primary outcome was patient-reported pain 7 days after the procedure, as measured by the visual analog scale (VAS). In all, 81% of patients were female, and median age was 47.5 years, the researchers reported.

Postoperative VAS pain scores rose significantly for both groups, compared with baseline, but did not significantly differ between the groups, said the investigators (single-port: 4.2 ± 2.4; four-port: 4.2 ± 2.2; P = .83). Cytokine levels and variations in heart rate also were similar between the groups.

However, measures of fatigue on the linear analog self-assessment were better with four-port entry, compared with the single-port approach (3.1 ± 2.1, versus 4.2 ± 2.2, respectively; P = .009), the investigators reported. And 49% of patients in the single-port group reported severe fatigue (a score greater than 5), compared with only 22% of the four-port group (P = .005).

“While this could be due to alpha-error, the fact that the group with the higher fatigue levels (single port) also seemed to be taking more oral narcotic pain medication before discharge … while maintaining similar pain scores in the postoperative period and otherwise having a similar distribution of factors affecting postoperative pain … suggests that the narcotic pain medication may have indeed had an influence on the fatigue scores,” the investigators said.

The National Institutes of Health and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences funded the research. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Single-port and four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy were associated with similar self-reported pain scores and physiologic measures of recovery, according to a double-blinded, randomized trial published online in the Journal of the American College of Surgery.

But patients in the four-port arm reported significantly less fatigue (P = .009), and 40% needed postoperative narcotics, compared with 60% of patients who underwent single-port laparoscopy (P = .056), reported Dr. Juliane Bingener and her associates at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, N.Y.

“The data from this study may assist patients and surgeons in the discussion on how to choose a procedure,” said the researchers. “If fast postoperative recovery is the most important goal, four-port cholecystectomy may be more advantageous than single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy. If cosmesis is the most important factor, single-port entry may be chosen” (J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2015 March 2 [doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.02.022]).

The study comprised 110 patients, of whom half underwent single-port and half underwent four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy, all performed by the same surgeon. The primary outcome was patient-reported pain 7 days after the procedure, as measured by the visual analog scale (VAS). In all, 81% of patients were female, and median age was 47.5 years, the researchers reported.

Postoperative VAS pain scores rose significantly for both groups, compared with baseline, but did not significantly differ between the groups, said the investigators (single-port: 4.2 ± 2.4; four-port: 4.2 ± 2.2; P = .83). Cytokine levels and variations in heart rate also were similar between the groups.

However, measures of fatigue on the linear analog self-assessment were better with four-port entry, compared with the single-port approach (3.1 ± 2.1, versus 4.2 ± 2.2, respectively; P = .009), the investigators reported. And 49% of patients in the single-port group reported severe fatigue (a score greater than 5), compared with only 22% of the four-port group (P = .005).

“While this could be due to alpha-error, the fact that the group with the higher fatigue levels (single port) also seemed to be taking more oral narcotic pain medication before discharge … while maintaining similar pain scores in the postoperative period and otherwise having a similar distribution of factors affecting postoperative pain … suggests that the narcotic pain medication may have indeed had an influence on the fatigue scores,” the investigators said.

The National Institutes of Health and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences funded the research. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF SURGERY

Key clinical point: Four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy was associated with less fatigue than was single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Major finding: Seven days after surgery, self-reported fatigue was lower for the four-port entry group compared with the single-port group (P = .009).

Data source: Double-blinded, randomized controlled trial of 110 patients who underwent single-port or four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences funded the research. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Noisy OR linked to communication gaps, surgical site infections

Noise in the OR has been on the rise for decades, prompting researchers to look into the links between sound levels, health impacts on surgeons, and patient outcomes.

A recent literature review found that noise levels in operating rooms frequently exceed OSHA guidelines for safe work environments. The OSHA recommendation for hospitals in general is 45 time-weighted average decibels (dbA) with a maximum peak of 140 dbA for “impulsive noise” events (Anesthesiology 2014;121:894-8). The sources of noise are many: moving of equipment, clashing metal instruments, pumps, suction apparatus, air warming units, monitors, alarms, nonclinical conversation, and background music. The review found evidence of the impact of noise on communication among staff, concentration of the surgeon, performance of complex tasks by surgeons and anesthesiologists and, potentially, patient outcomes. Noise was found to be greater at the beginning and closing of procedures, and routine peak levels reported were in excess of 100 dBA for various procedures and as high as 131 dBA in some instances.

Another study linked communication gaps in the OR to high noise levels (J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2013:216:933-8). The amount of noise from equipment, staff conversation, and background music was found to have a negative impact on surgeon performance, especially when complex tasks were in process.

Noise pollution during surgery is now being studied in terms of patient outcomes, postop complications, and surgical-site infections (SSIs) in particular.

A pilot study in the United Kingdom looked at noise in the OR as a possible surrogate marker for intraoperative behavior and a potential predictor of SSIs. With a small sample of 35 elective open abdominal procedures, a significant correlation was detected between noise levels and the 30-day postop SSI rate in these patients (Br. J. Surg. 2011;98:1021-5).

Another study has found that high noise levels in the operating room were linked to surgical site infections after outpatient hernia repair (Surgery 2015 Feb. 28 [doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.12.026]). “Noise levels were substantially greater in patients with surgical site infections from time point of 50 minutes onwards, which correlated to when wound closure was occurring,” wrote Dr. Shamik Dholakia and his associates at the Milton Keynes General Hospital in Buckinghamshire, England.

The researchers found that music and conversation were the two main contributors to increased noise levels in the OR. “Both of these factors may have distracting influences on the operator and contribute to lower levels of concentration, and so need to be considered as potential issues that could be improved to reduce error,” they said.

Past studies have linked surgical site infections (SSI) with lapses in aseptic technique, which can occur if the OR team is distracted. To assess the role of OR noise in SSI risk, the investigators prospectively studied 64 male, otherwise healthy outpatients who underwent left-side inguinal hernia repair at a single hospital. All patients received a prophylactic dose of 1.2 grams of co-amoxiclav antibiotic, and the same kind of mesh and suture were used for all cases, the investigators said.

The researchers used a decibel meter to measure sound levels in the OR during surgeries, and interviewed patients weekly for the next 30 days to detect SSI.

Five patients (7.8%) developed SSI, all of which were superficial. Swabs from these patients grew mixed skin flora that were sensitive to penicillin, said the researchers.

The mean level for background noise was 47.6 dB before the procedure started. On average, noise levels during procedures for which patients developed SSI were 11.337 dB higher than during other procedures. “Although the actual formula is complex, the accepted rule is that an increase of 10 decibels is perceived to be approximately twice as loud,” the investigators said. “Hence, we believe that this increase in loudness is significant enough to effect the operation. On the basis of our results, we hypothesize that poor concentration caused by high levels of noise may affect one’s ability to perform adequate aseptic closure and increase the probability of developing SSI.”

Surgical assistants usually closed the surgical wounds, which was notable because music’s effects on concentration vary with experience, the researchers noted. “Music may have a soothing, calming, and positive effect on senior experienced operators, whereas it may be distracting and reduce ability to concentrate on junior operators who are not experienced and still learning how to perform the procedure,” they said. “This finding is an important one that the lead surgeon needs to be aware of.”The investigators reported no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

Hospitals are noisy. Noise intensities in operating rooms frequently exceed those found in the hospital’s boiler room.