User login

Esophageal cancer screen rarely incites legal claims

Physicians’ failure to screen patients for esophageal cancer rarely incites legal claims, according to a Research Letter published online September 30 in JAMA. Endoscopic screening for esophageal adenocarcinoma is recommended for patients with chronic symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease only if they have additional risk factors. But physician surveys indicate that many clinicians order or perform upper-GI endoscopy in symptomatic patients with no additional risk factors, out of fear of litigation for missing a cancer, said Dr. Megan A. Adams of the division of gastroenterology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and her associates.

To assess the actual risk of such litigation, the investigators analyzed information from “the largest U.S. medical professional liability claims database,” which includes insurance companies that collectively cover more than two-thirds of private-practice physicians across the country. They identified 278,220 claims filed against physicians in 1985-2012, of which 761 were related to upper-GI endoscopy. Of the 268 claims that involved esophageal malignancies, 19 were filed for failure to screen a low-risk patient for esophageal cancer, and only 4 of those were paid to the claimants.

In comparison, 17 claims were filed and 8 were paid for complications arising from upper-GI endoscopies done for “questionable” indications. Thus, clinicians who perform the procedure because of fear of litigation for missing an esophageal cancer are just as likely to be sued for complications of an unnecessary endoscopy, noted Dr. Adams and her associates (JAMA 2014;312:1348-9).

“There may be legitimate reasons to screen for esophageal cancer in some [low-risk] patients, but our findings suggest that the risk of a medical professional liability claim for failing to screen is not one of them,” they noted.

Physicians’ failure to screen patients for esophageal cancer rarely incites legal claims, according to a Research Letter published online September 30 in JAMA. Endoscopic screening for esophageal adenocarcinoma is recommended for patients with chronic symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease only if they have additional risk factors. But physician surveys indicate that many clinicians order or perform upper-GI endoscopy in symptomatic patients with no additional risk factors, out of fear of litigation for missing a cancer, said Dr. Megan A. Adams of the division of gastroenterology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and her associates.

To assess the actual risk of such litigation, the investigators analyzed information from “the largest U.S. medical professional liability claims database,” which includes insurance companies that collectively cover more than two-thirds of private-practice physicians across the country. They identified 278,220 claims filed against physicians in 1985-2012, of which 761 were related to upper-GI endoscopy. Of the 268 claims that involved esophageal malignancies, 19 were filed for failure to screen a low-risk patient for esophageal cancer, and only 4 of those were paid to the claimants.

In comparison, 17 claims were filed and 8 were paid for complications arising from upper-GI endoscopies done for “questionable” indications. Thus, clinicians who perform the procedure because of fear of litigation for missing an esophageal cancer are just as likely to be sued for complications of an unnecessary endoscopy, noted Dr. Adams and her associates (JAMA 2014;312:1348-9).

“There may be legitimate reasons to screen for esophageal cancer in some [low-risk] patients, but our findings suggest that the risk of a medical professional liability claim for failing to screen is not one of them,” they noted.

Physicians’ failure to screen patients for esophageal cancer rarely incites legal claims, according to a Research Letter published online September 30 in JAMA. Endoscopic screening for esophageal adenocarcinoma is recommended for patients with chronic symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease only if they have additional risk factors. But physician surveys indicate that many clinicians order or perform upper-GI endoscopy in symptomatic patients with no additional risk factors, out of fear of litigation for missing a cancer, said Dr. Megan A. Adams of the division of gastroenterology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and her associates.

To assess the actual risk of such litigation, the investigators analyzed information from “the largest U.S. medical professional liability claims database,” which includes insurance companies that collectively cover more than two-thirds of private-practice physicians across the country. They identified 278,220 claims filed against physicians in 1985-2012, of which 761 were related to upper-GI endoscopy. Of the 268 claims that involved esophageal malignancies, 19 were filed for failure to screen a low-risk patient for esophageal cancer, and only 4 of those were paid to the claimants.

In comparison, 17 claims were filed and 8 were paid for complications arising from upper-GI endoscopies done for “questionable” indications. Thus, clinicians who perform the procedure because of fear of litigation for missing an esophageal cancer are just as likely to be sued for complications of an unnecessary endoscopy, noted Dr. Adams and her associates (JAMA 2014;312:1348-9).

“There may be legitimate reasons to screen for esophageal cancer in some [low-risk] patients, but our findings suggest that the risk of a medical professional liability claim for failing to screen is not one of them,” they noted.

Key clinical point: Physicians are rarely sued for failure to screen for esophageal cancer.

Major finding: Among 278,220 legal claims against physicians in 1985-2012, 19 of the 268 that involved esophageal malignancies were filed for failure to screen.

Data source: A medical professional liability claims database.

Disclosures: Dr. Adams reported having no financial disclosures.

Lung-MAP trial launched, matching patients to treatments based on tumor profiles

A phase II/III trial using genomic profiling to match patients with investigational treatments is currently recruiting patients with advanced squamous cell lung cancer.

The Lung-MAP (Lung Cancer Master Protocol) trial is a public-private collaboration among the National Cancer Institute (NCI), SWOG Cancer Research, Friends of Cancer Research, the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health, Foundation Medicine, and five pharmaceutical companies (Amgen, Genentech, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and AstraZeneca’s global biologics R&D arm, MedImmune).

"Lung-MAP represents the first of several planned large, genomically driven treatment trials that will be conducted by NCI’s newly formed National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN)," Dr. Jeffrey S. Abrams, associate director of NCI’s Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program, said in a press release announcing the trial launch. "The restructuring and consolidation of NCI’s large trial treatment program, resulting in the formation of the NCTN, is quite timely, as it now can offer an ideal platform for bringing the benefits of more precise molecular diagnostics to cancer patients in communities large and small, " he said.

Lung-MAP is expected to enroll 10,000 patients and be completed in 2022. To be eligible, patients will have progressed after receiving exactly one front-line, platinum-containing metastatic chemotherapy regimen. Between 500 and 1,000 patients will be screened per year for more than 200 cancer-related gene alterations. Based on the tumor profiles, all patients will then be assigned to one of five initial treatment arms, testing four investigational targeted treatments and an anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy.

The trial will be conducted at more than 200 medical centers. As many as five to seven additional drugs may be evaluated over the next 5 years, the press release said. Information on enrolling patients can be found on the trial website.

A phase II/III trial using genomic profiling to match patients with investigational treatments is currently recruiting patients with advanced squamous cell lung cancer.

The Lung-MAP (Lung Cancer Master Protocol) trial is a public-private collaboration among the National Cancer Institute (NCI), SWOG Cancer Research, Friends of Cancer Research, the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health, Foundation Medicine, and five pharmaceutical companies (Amgen, Genentech, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and AstraZeneca’s global biologics R&D arm, MedImmune).

"Lung-MAP represents the first of several planned large, genomically driven treatment trials that will be conducted by NCI’s newly formed National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN)," Dr. Jeffrey S. Abrams, associate director of NCI’s Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program, said in a press release announcing the trial launch. "The restructuring and consolidation of NCI’s large trial treatment program, resulting in the formation of the NCTN, is quite timely, as it now can offer an ideal platform for bringing the benefits of more precise molecular diagnostics to cancer patients in communities large and small, " he said.

Lung-MAP is expected to enroll 10,000 patients and be completed in 2022. To be eligible, patients will have progressed after receiving exactly one front-line, platinum-containing metastatic chemotherapy regimen. Between 500 and 1,000 patients will be screened per year for more than 200 cancer-related gene alterations. Based on the tumor profiles, all patients will then be assigned to one of five initial treatment arms, testing four investigational targeted treatments and an anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy.

The trial will be conducted at more than 200 medical centers. As many as five to seven additional drugs may be evaluated over the next 5 years, the press release said. Information on enrolling patients can be found on the trial website.

A phase II/III trial using genomic profiling to match patients with investigational treatments is currently recruiting patients with advanced squamous cell lung cancer.

The Lung-MAP (Lung Cancer Master Protocol) trial is a public-private collaboration among the National Cancer Institute (NCI), SWOG Cancer Research, Friends of Cancer Research, the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health, Foundation Medicine, and five pharmaceutical companies (Amgen, Genentech, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and AstraZeneca’s global biologics R&D arm, MedImmune).

"Lung-MAP represents the first of several planned large, genomically driven treatment trials that will be conducted by NCI’s newly formed National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN)," Dr. Jeffrey S. Abrams, associate director of NCI’s Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program, said in a press release announcing the trial launch. "The restructuring and consolidation of NCI’s large trial treatment program, resulting in the formation of the NCTN, is quite timely, as it now can offer an ideal platform for bringing the benefits of more precise molecular diagnostics to cancer patients in communities large and small, " he said.

Lung-MAP is expected to enroll 10,000 patients and be completed in 2022. To be eligible, patients will have progressed after receiving exactly one front-line, platinum-containing metastatic chemotherapy regimen. Between 500 and 1,000 patients will be screened per year for more than 200 cancer-related gene alterations. Based on the tumor profiles, all patients will then be assigned to one of five initial treatment arms, testing four investigational targeted treatments and an anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy.

The trial will be conducted at more than 200 medical centers. As many as five to seven additional drugs may be evaluated over the next 5 years, the press release said. Information on enrolling patients can be found on the trial website.

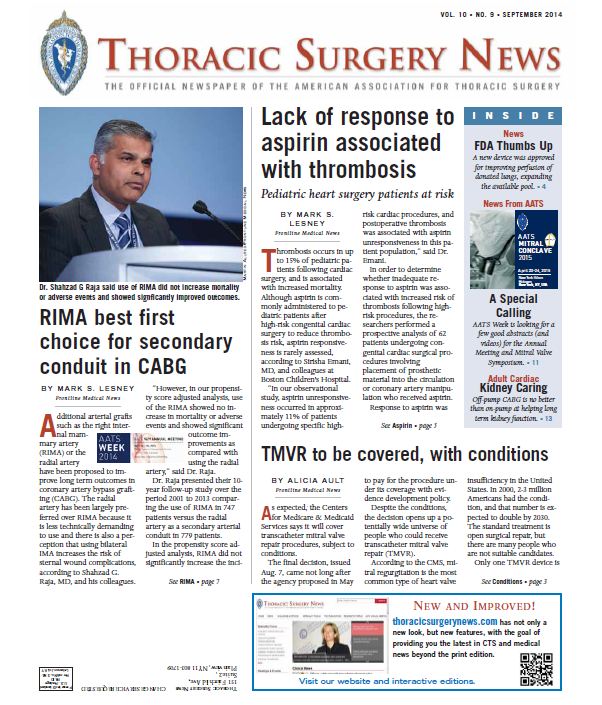

The September issue of Thoracic Surgery News is now available online

Be sure to visit our interactive digital or PDF version of the September issue of Thoracic Surgery News. This month we are featuring stories ranging from the risks of aspirin resistance in pediatric cardiac surgery patients to the recent Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services decision to cover transcatheter mitral valve repair (TMVR) procedures. Also, in our News from the AATS section there is a call for abstracts for AATS Week (comprising the 95th AATS Annual Meeting and the AATS Mitral Conclave), as well as several exciting cardiothoracic surgery fellowship opportunities.

To view our September PDF and interactive digital edition, click here.

Be sure to visit our interactive digital or PDF version of the September issue of Thoracic Surgery News. This month we are featuring stories ranging from the risks of aspirin resistance in pediatric cardiac surgery patients to the recent Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services decision to cover transcatheter mitral valve repair (TMVR) procedures. Also, in our News from the AATS section there is a call for abstracts for AATS Week (comprising the 95th AATS Annual Meeting and the AATS Mitral Conclave), as well as several exciting cardiothoracic surgery fellowship opportunities.

To view our September PDF and interactive digital edition, click here.

Be sure to visit our interactive digital or PDF version of the September issue of Thoracic Surgery News. This month we are featuring stories ranging from the risks of aspirin resistance in pediatric cardiac surgery patients to the recent Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services decision to cover transcatheter mitral valve repair (TMVR) procedures. Also, in our News from the AATS section there is a call for abstracts for AATS Week (comprising the 95th AATS Annual Meeting and the AATS Mitral Conclave), as well as several exciting cardiothoracic surgery fellowship opportunities.

To view our September PDF and interactive digital edition, click here.

Thoracic radiotherapy backed for extensive SCLC

CHICAGO – Thoracic radiotherapy improved overall survival, progression-free survival, and intrathoracic control in patients with extensive small-cell lung cancer who responded to chemotherapy, according to results from the randomized CREST study.

"Thoracic radiotherapy should be offered in addition to PCI [prophylactic cranial irradiation] to all extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer patients responding to initial chemotherapy," Dr. Ben J. Slotman said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

The rationale for CREST (Chest Radiotherapy Extensive Stage Trial) was based on an earlier trial by Dr. Slotman showing that prophylactic cranial irradiation not only lowered the risk of symptomatic brain metastases but also significantly improved 1-year overall survival compared with no additional therapy in patients with extensive small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) who had any response to chemotherapy (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:664-72).

Most patients, however, had persistent intrathoracic disease after chemotherapy or intrathoracic progression, said Dr. Slotman, professor and head of radiation oncology, VU Medical Center, Amsterdam.

CREST investigators at 42 centers in the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Norway, and Belgium randomly assigned 498 patients with any response after four to six cycles of initial platinum-based chemotherapy to thoracic radiotherapy (TRT) (30 Gy in 10 fractions) plus PCI or PCI only. Treatment began within 2-7 weeks of their last chemotherapy. Patients with brain or plural metastasis, pleuritis carcinomatosa, or prior radiotherapy (RT) to the brain or thorax were excluded.

About 70% of patients had a partial response to chemotherapy, and almost 90% still had persistent intrathoracic disease at the time of randomization. Their median age was 63 years.

Overall survival at 1 year was not statistically different between the TRT and no TRT arms (33% vs. 28%; hazard ratio, 0.84; P = .066). The survival curves began to diverge after 9 months, however, leading to a significant overall survival benefit favoring TRT at 18 months (P = .03) and 24 months (13% vs. 3%; P = .004), Dr. Slotman said.

A subgroup analysis found no influence on overall survival for treatment factors such as age, sex, response after chemotherapy, or presence of intrathoracic disease at randomization.

Discussant Dr. Walter J. Curran Jr., executive director of the Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University, Atlanta, said CREST was a well-executed and adequately powered trial, but argued that its conclusion that thoracic RT improves overall survival "is not supported by the presented data."

The hazard ratio of 0.84 failed to reach the HR goal of 0.76, and the comparison at 2 years was not the primary end point of the trial, he said.

Dr. Curran said there is a rationale for why sequential chemotherapy-radiation would work for patients with more extensive disease, even though every randomized limited disease small-cell trial has shown a benefit with concurrent vs. sequential chemotherapy-radiation therapy or early vs. delayed concurrent chemoradiation, and little to no benefit with sequential chemoradiation, compared with chemotherapy alone.

"The rationale behind it, and it’s a reasonable one, is that in the noncurative setting, which is what we’re dealing with if you remember the survival curves Dr. Slotman showed us, we really are probably talking about debulking chemoresistant disease," he said. "If one is able to do that with limited toxicity and without long-lasting morbidity, that might extend survival but certainly is not going to procure cure rates as thoracic radiation can do in limited disease."

Progression-free survival was significantly better in patients receiving TRT vs. no TRT (HR, 0.73; P = .001), Dr. Slotman said.

TRT-treated patients also had significantly less intrathoracic progression overall (43.7% vs. 80%; P less than .001), as the first site of relapse (41.7% vs. 78%; P less than .001), and as the only site of relapse (20% vs. 46%; P less than .001).

Going forward, Dr. Curran said it will be important to know whether patients with extensive-stage disease receiving TRT also have less progression of thoracic disease and to better understand quality of life and toxicity associated with the therapy.

Dr. Slotman said grade 3/4 toxicity was similar between groups, although those receiving radiation had a modest increased risk of grade 3 fatigue (11 vs. 8 events) and grade 3 esophagitis (4 events vs. 0 events).

CHICAGO – Thoracic radiotherapy improved overall survival, progression-free survival, and intrathoracic control in patients with extensive small-cell lung cancer who responded to chemotherapy, according to results from the randomized CREST study.

"Thoracic radiotherapy should be offered in addition to PCI [prophylactic cranial irradiation] to all extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer patients responding to initial chemotherapy," Dr. Ben J. Slotman said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

The rationale for CREST (Chest Radiotherapy Extensive Stage Trial) was based on an earlier trial by Dr. Slotman showing that prophylactic cranial irradiation not only lowered the risk of symptomatic brain metastases but also significantly improved 1-year overall survival compared with no additional therapy in patients with extensive small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) who had any response to chemotherapy (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:664-72).

Most patients, however, had persistent intrathoracic disease after chemotherapy or intrathoracic progression, said Dr. Slotman, professor and head of radiation oncology, VU Medical Center, Amsterdam.

CREST investigators at 42 centers in the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Norway, and Belgium randomly assigned 498 patients with any response after four to six cycles of initial platinum-based chemotherapy to thoracic radiotherapy (TRT) (30 Gy in 10 fractions) plus PCI or PCI only. Treatment began within 2-7 weeks of their last chemotherapy. Patients with brain or plural metastasis, pleuritis carcinomatosa, or prior radiotherapy (RT) to the brain or thorax were excluded.

About 70% of patients had a partial response to chemotherapy, and almost 90% still had persistent intrathoracic disease at the time of randomization. Their median age was 63 years.

Overall survival at 1 year was not statistically different between the TRT and no TRT arms (33% vs. 28%; hazard ratio, 0.84; P = .066). The survival curves began to diverge after 9 months, however, leading to a significant overall survival benefit favoring TRT at 18 months (P = .03) and 24 months (13% vs. 3%; P = .004), Dr. Slotman said.

A subgroup analysis found no influence on overall survival for treatment factors such as age, sex, response after chemotherapy, or presence of intrathoracic disease at randomization.

Discussant Dr. Walter J. Curran Jr., executive director of the Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University, Atlanta, said CREST was a well-executed and adequately powered trial, but argued that its conclusion that thoracic RT improves overall survival "is not supported by the presented data."

The hazard ratio of 0.84 failed to reach the HR goal of 0.76, and the comparison at 2 years was not the primary end point of the trial, he said.

Dr. Curran said there is a rationale for why sequential chemotherapy-radiation would work for patients with more extensive disease, even though every randomized limited disease small-cell trial has shown a benefit with concurrent vs. sequential chemotherapy-radiation therapy or early vs. delayed concurrent chemoradiation, and little to no benefit with sequential chemoradiation, compared with chemotherapy alone.

"The rationale behind it, and it’s a reasonable one, is that in the noncurative setting, which is what we’re dealing with if you remember the survival curves Dr. Slotman showed us, we really are probably talking about debulking chemoresistant disease," he said. "If one is able to do that with limited toxicity and without long-lasting morbidity, that might extend survival but certainly is not going to procure cure rates as thoracic radiation can do in limited disease."

Progression-free survival was significantly better in patients receiving TRT vs. no TRT (HR, 0.73; P = .001), Dr. Slotman said.

TRT-treated patients also had significantly less intrathoracic progression overall (43.7% vs. 80%; P less than .001), as the first site of relapse (41.7% vs. 78%; P less than .001), and as the only site of relapse (20% vs. 46%; P less than .001).

Going forward, Dr. Curran said it will be important to know whether patients with extensive-stage disease receiving TRT also have less progression of thoracic disease and to better understand quality of life and toxicity associated with the therapy.

Dr. Slotman said grade 3/4 toxicity was similar between groups, although those receiving radiation had a modest increased risk of grade 3 fatigue (11 vs. 8 events) and grade 3 esophagitis (4 events vs. 0 events).

CHICAGO – Thoracic radiotherapy improved overall survival, progression-free survival, and intrathoracic control in patients with extensive small-cell lung cancer who responded to chemotherapy, according to results from the randomized CREST study.

"Thoracic radiotherapy should be offered in addition to PCI [prophylactic cranial irradiation] to all extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer patients responding to initial chemotherapy," Dr. Ben J. Slotman said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

The rationale for CREST (Chest Radiotherapy Extensive Stage Trial) was based on an earlier trial by Dr. Slotman showing that prophylactic cranial irradiation not only lowered the risk of symptomatic brain metastases but also significantly improved 1-year overall survival compared with no additional therapy in patients with extensive small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) who had any response to chemotherapy (N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:664-72).

Most patients, however, had persistent intrathoracic disease after chemotherapy or intrathoracic progression, said Dr. Slotman, professor and head of radiation oncology, VU Medical Center, Amsterdam.

CREST investigators at 42 centers in the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Norway, and Belgium randomly assigned 498 patients with any response after four to six cycles of initial platinum-based chemotherapy to thoracic radiotherapy (TRT) (30 Gy in 10 fractions) plus PCI or PCI only. Treatment began within 2-7 weeks of their last chemotherapy. Patients with brain or plural metastasis, pleuritis carcinomatosa, or prior radiotherapy (RT) to the brain or thorax were excluded.

About 70% of patients had a partial response to chemotherapy, and almost 90% still had persistent intrathoracic disease at the time of randomization. Their median age was 63 years.

Overall survival at 1 year was not statistically different between the TRT and no TRT arms (33% vs. 28%; hazard ratio, 0.84; P = .066). The survival curves began to diverge after 9 months, however, leading to a significant overall survival benefit favoring TRT at 18 months (P = .03) and 24 months (13% vs. 3%; P = .004), Dr. Slotman said.

A subgroup analysis found no influence on overall survival for treatment factors such as age, sex, response after chemotherapy, or presence of intrathoracic disease at randomization.

Discussant Dr. Walter J. Curran Jr., executive director of the Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University, Atlanta, said CREST was a well-executed and adequately powered trial, but argued that its conclusion that thoracic RT improves overall survival "is not supported by the presented data."

The hazard ratio of 0.84 failed to reach the HR goal of 0.76, and the comparison at 2 years was not the primary end point of the trial, he said.

Dr. Curran said there is a rationale for why sequential chemotherapy-radiation would work for patients with more extensive disease, even though every randomized limited disease small-cell trial has shown a benefit with concurrent vs. sequential chemotherapy-radiation therapy or early vs. delayed concurrent chemoradiation, and little to no benefit with sequential chemoradiation, compared with chemotherapy alone.

"The rationale behind it, and it’s a reasonable one, is that in the noncurative setting, which is what we’re dealing with if you remember the survival curves Dr. Slotman showed us, we really are probably talking about debulking chemoresistant disease," he said. "If one is able to do that with limited toxicity and without long-lasting morbidity, that might extend survival but certainly is not going to procure cure rates as thoracic radiation can do in limited disease."

Progression-free survival was significantly better in patients receiving TRT vs. no TRT (HR, 0.73; P = .001), Dr. Slotman said.

TRT-treated patients also had significantly less intrathoracic progression overall (43.7% vs. 80%; P less than .001), as the first site of relapse (41.7% vs. 78%; P less than .001), and as the only site of relapse (20% vs. 46%; P less than .001).

Going forward, Dr. Curran said it will be important to know whether patients with extensive-stage disease receiving TRT also have less progression of thoracic disease and to better understand quality of life and toxicity associated with the therapy.

Dr. Slotman said grade 3/4 toxicity was similar between groups, although those receiving radiation had a modest increased risk of grade 3 fatigue (11 vs. 8 events) and grade 3 esophagitis (4 events vs. 0 events).

AT THE ASCO ANNUAL MEETING 2014

Key clinical point: Thoracic radiotherapy may improve survival when delivered after chemotherapy in extensive-stage lung cancer responding to chemotherapy.

Major finding: Overall survival at 1 year was not statistically different between the TRT and no TRT arms (HR, 0.84; P = .066) but was significantly different at 18 months (P = .03) and 24 months (P = .004).

Data source: A randomized study of 498 patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer responding to initial chemotherapy.

Disclosures: Dr. Slotman and his coauthors reported no financial disclosures.

Patient satisfaction not always linked to hospital safety, effectiveness

BOSTON – Hospital size and operative volume were significantly associated with satisfaction among general surgery patients in an analysis of 171 U.S. hospitals.

Surprisingly, all other safety and effectiveness measures, with the exception of low hospital mortality index, did not reliably reflect patient satisfaction, "indicating that the system plays perhaps a bigger role than anything else we can do," Dr. Gregory D. Kennedy said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

Moreover, a clean room and well-controlled pain were the best predictors of high patient satisfaction.

If it’s "the quality of the hotel, not the quality of the surgeon that drives patient satisfaction," and given that this is tied to reimbursement, what should the message be to hospital CEOs? asked discussant Dr. John J. Ricotta, chief of surgery at MedStar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center.

Dr. Kennedy said the message he takes to the C-suite is that patient satisfaction cannot be a surrogate marker for safety and effectiveness or the only measure of quality because, in doing the right thing, surgeons often make patients unhappy. As a colorectal surgeon, he said he has unhappy patients every day, and remarked that he sometimes feels like a used car salesman where the only thing that he worries about is whether the patient is having a good experience when they drive off the lot, not whether it’s a safe, reliable car.

Dr. Kennedy, vice chair of quality at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine, Madison, suggested that future quality measures also may need to make the distinction between satisfied and engaged, well-informed patients because a disengaged patient can be highly satisfied, while a highly engaged patient may not.

For the current study, the investigators examined federal Hospital Consumer Assessment Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey results from 171 hospitals in the University Health System Consortium database from 2011 to 2012. Patients can check one of four boxes for each question on the 27-item survey, with high satisfaction defined as median responses above the 75th percentile on the top box score. This cutoff was used because the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which developed the HCAHPS, uses only the top box score, Dr. Kennedy explained.

The median hospital size was 421 beds (range, 25-1,280 beds), the median operative volume was 6,341 cases (range, 192-24,258 cases), and the mortality index was 0.83 (range, 0-2.61).

In all, 62% of high-volume hospitals, defined as those with an operative volume above the median, achieved high patient satisfaction, compared with 38% of low-volume hospitals (P less than .001). Similar results were seen for operative volume, he said.

Other system measures such as number of ICU cases and Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP) compliance were not associated with high HCAHPS scores.

Among patient safety indicators, only low mortality index was associated with high satisfaction (P less than .001), while complications, early mortality, and overall mortality were not.

Interestingly, hospitals with a higher number of Patient Safety Indicator cases – those involving accidental puncture, laceration, and venous thromboembolism – had higher rates of patient satisfaction, "suggesting that unsafe care is perhaps correlated with high satisfaction," Dr. Kennedy said.

Discussant Dr. Fabrizio Michelassi, chair of surgery at Weill Cornell Medical College and surgeon-in-chief, New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, in New York City, questioned whether "unsafe care gives more options for physicians to show their compassionate side," and said the overall findings are not that surprising to practicing surgeons, who frequently hear patient complaints, despite having performed a quality operation.

Dr. Kennedy said a recent paper from the Cleveland Clinic (Dis. Colon Rectum. 2013;56:219-25) suggests that Patient Safety Indicator cases are really a reflection of surgical complexity and not unsafe care at all.

Finally, other discussants criticized the study for failing to tie satisfaction to patient outcomes; for failing to control for factors influencing patient satisfaction such as age, sex, or social status; and for not looking at geographic differences or nursing-to-staff ratios.

The complete manuscript of this study and its presentation at the American Surgical Association’s 134th Annual Meeting, April 2014, in Boston, is anticipated to be published in the Annals of Surgery, pending editorial review.

Dr. Kennedy reported no conflicting interests.

BOSTON – Hospital size and operative volume were significantly associated with satisfaction among general surgery patients in an analysis of 171 U.S. hospitals.

Surprisingly, all other safety and effectiveness measures, with the exception of low hospital mortality index, did not reliably reflect patient satisfaction, "indicating that the system plays perhaps a bigger role than anything else we can do," Dr. Gregory D. Kennedy said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

Moreover, a clean room and well-controlled pain were the best predictors of high patient satisfaction.

If it’s "the quality of the hotel, not the quality of the surgeon that drives patient satisfaction," and given that this is tied to reimbursement, what should the message be to hospital CEOs? asked discussant Dr. John J. Ricotta, chief of surgery at MedStar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center.

Dr. Kennedy said the message he takes to the C-suite is that patient satisfaction cannot be a surrogate marker for safety and effectiveness or the only measure of quality because, in doing the right thing, surgeons often make patients unhappy. As a colorectal surgeon, he said he has unhappy patients every day, and remarked that he sometimes feels like a used car salesman where the only thing that he worries about is whether the patient is having a good experience when they drive off the lot, not whether it’s a safe, reliable car.

Dr. Kennedy, vice chair of quality at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine, Madison, suggested that future quality measures also may need to make the distinction between satisfied and engaged, well-informed patients because a disengaged patient can be highly satisfied, while a highly engaged patient may not.

For the current study, the investigators examined federal Hospital Consumer Assessment Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey results from 171 hospitals in the University Health System Consortium database from 2011 to 2012. Patients can check one of four boxes for each question on the 27-item survey, with high satisfaction defined as median responses above the 75th percentile on the top box score. This cutoff was used because the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which developed the HCAHPS, uses only the top box score, Dr. Kennedy explained.

The median hospital size was 421 beds (range, 25-1,280 beds), the median operative volume was 6,341 cases (range, 192-24,258 cases), and the mortality index was 0.83 (range, 0-2.61).

In all, 62% of high-volume hospitals, defined as those with an operative volume above the median, achieved high patient satisfaction, compared with 38% of low-volume hospitals (P less than .001). Similar results were seen for operative volume, he said.

Other system measures such as number of ICU cases and Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP) compliance were not associated with high HCAHPS scores.

Among patient safety indicators, only low mortality index was associated with high satisfaction (P less than .001), while complications, early mortality, and overall mortality were not.

Interestingly, hospitals with a higher number of Patient Safety Indicator cases – those involving accidental puncture, laceration, and venous thromboembolism – had higher rates of patient satisfaction, "suggesting that unsafe care is perhaps correlated with high satisfaction," Dr. Kennedy said.

Discussant Dr. Fabrizio Michelassi, chair of surgery at Weill Cornell Medical College and surgeon-in-chief, New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, in New York City, questioned whether "unsafe care gives more options for physicians to show their compassionate side," and said the overall findings are not that surprising to practicing surgeons, who frequently hear patient complaints, despite having performed a quality operation.

Dr. Kennedy said a recent paper from the Cleveland Clinic (Dis. Colon Rectum. 2013;56:219-25) suggests that Patient Safety Indicator cases are really a reflection of surgical complexity and not unsafe care at all.

Finally, other discussants criticized the study for failing to tie satisfaction to patient outcomes; for failing to control for factors influencing patient satisfaction such as age, sex, or social status; and for not looking at geographic differences or nursing-to-staff ratios.

The complete manuscript of this study and its presentation at the American Surgical Association’s 134th Annual Meeting, April 2014, in Boston, is anticipated to be published in the Annals of Surgery, pending editorial review.

Dr. Kennedy reported no conflicting interests.

BOSTON – Hospital size and operative volume were significantly associated with satisfaction among general surgery patients in an analysis of 171 U.S. hospitals.

Surprisingly, all other safety and effectiveness measures, with the exception of low hospital mortality index, did not reliably reflect patient satisfaction, "indicating that the system plays perhaps a bigger role than anything else we can do," Dr. Gregory D. Kennedy said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

Moreover, a clean room and well-controlled pain were the best predictors of high patient satisfaction.

If it’s "the quality of the hotel, not the quality of the surgeon that drives patient satisfaction," and given that this is tied to reimbursement, what should the message be to hospital CEOs? asked discussant Dr. John J. Ricotta, chief of surgery at MedStar Washington (D.C.) Hospital Center.

Dr. Kennedy said the message he takes to the C-suite is that patient satisfaction cannot be a surrogate marker for safety and effectiveness or the only measure of quality because, in doing the right thing, surgeons often make patients unhappy. As a colorectal surgeon, he said he has unhappy patients every day, and remarked that he sometimes feels like a used car salesman where the only thing that he worries about is whether the patient is having a good experience when they drive off the lot, not whether it’s a safe, reliable car.

Dr. Kennedy, vice chair of quality at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine, Madison, suggested that future quality measures also may need to make the distinction between satisfied and engaged, well-informed patients because a disengaged patient can be highly satisfied, while a highly engaged patient may not.

For the current study, the investigators examined federal Hospital Consumer Assessment Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey results from 171 hospitals in the University Health System Consortium database from 2011 to 2012. Patients can check one of four boxes for each question on the 27-item survey, with high satisfaction defined as median responses above the 75th percentile on the top box score. This cutoff was used because the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which developed the HCAHPS, uses only the top box score, Dr. Kennedy explained.

The median hospital size was 421 beds (range, 25-1,280 beds), the median operative volume was 6,341 cases (range, 192-24,258 cases), and the mortality index was 0.83 (range, 0-2.61).

In all, 62% of high-volume hospitals, defined as those with an operative volume above the median, achieved high patient satisfaction, compared with 38% of low-volume hospitals (P less than .001). Similar results were seen for operative volume, he said.

Other system measures such as number of ICU cases and Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP) compliance were not associated with high HCAHPS scores.

Among patient safety indicators, only low mortality index was associated with high satisfaction (P less than .001), while complications, early mortality, and overall mortality were not.

Interestingly, hospitals with a higher number of Patient Safety Indicator cases – those involving accidental puncture, laceration, and venous thromboembolism – had higher rates of patient satisfaction, "suggesting that unsafe care is perhaps correlated with high satisfaction," Dr. Kennedy said.

Discussant Dr. Fabrizio Michelassi, chair of surgery at Weill Cornell Medical College and surgeon-in-chief, New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, in New York City, questioned whether "unsafe care gives more options for physicians to show their compassionate side," and said the overall findings are not that surprising to practicing surgeons, who frequently hear patient complaints, despite having performed a quality operation.

Dr. Kennedy said a recent paper from the Cleveland Clinic (Dis. Colon Rectum. 2013;56:219-25) suggests that Patient Safety Indicator cases are really a reflection of surgical complexity and not unsafe care at all.

Finally, other discussants criticized the study for failing to tie satisfaction to patient outcomes; for failing to control for factors influencing patient satisfaction such as age, sex, or social status; and for not looking at geographic differences or nursing-to-staff ratios.

The complete manuscript of this study and its presentation at the American Surgical Association’s 134th Annual Meeting, April 2014, in Boston, is anticipated to be published in the Annals of Surgery, pending editorial review.

Dr. Kennedy reported no conflicting interests.

AT ASA 2014

Major finding: In the sample, 62% of high-volume hospitals achieved high patient satisfaction, vs. 38% of low-volume hospitals. Other system measures such as number of ICU cases and Surgical Care Improvement Project (compliance were not associated with high HCAHPS scores.

Data source: A retrospective analysis of HCAHPS surveys at 171 U.S. hospitals.

Disclosures: Dr. Kennedy reported no conflicting interests.

Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy fails to boost survival

For patients with early-stage esophageal cancer, undergoing chemotherapy and radiotherapy before surgical excision failed to improve the rate of curative resection and, most importantly, failed to boost survival in a phase III clinical trial, according to a report published online June 30 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Unfortunately this treatment strategy also tripled postoperative mortality, making the risk-benefit ratio even more lopsided for this patient population, said Dr. Christophe Mariette of the department of digestive and oncologic surgery, University Hospital Claude Huriez-Regional University Hospital Center, Lille (France), and his associates.

Clinical trials examining neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for esophageal cancer have produced conflicting results, with some showing that the approach is effective, in some cases doubling median survival, while others showed no benefit. Most such studies have been limited by small sample sizes, heterogeneity of tumor types, variations in radiation doses and chemotherapy regiments, and differences in preoperative staging techniques and the adequacy of surgical resections. Moreover, the number of study participants with early-stage esophageal cancer has been very small because most patients already have more advanced disease at presentation, the investigators noted.

For their study, Dr. Mariette and his associates confined the cohort to patients younger than 75 years with treatment-naive esophageal adenocarcinoma or squamous-cell carcinoma judged to be stage I or II using thoracoabdominal CT and endoscopic ultrasound; additional preoperative assessments using PET scanning, cervical ultrasound, or radionuclide bone scanning were optional. It required 9 years to enroll 195 patients at 30 French medical centers. These study participants were randomly assigned to receive either neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus radiotherapy before potentially curative surgery (98 subjects) or potentially curative surgery alone (97 subjects).

In the intervention group, radiotherapy involved a total dose of 45 Gy delivered in 25 fractions over the course of 5 weeks. Chemotherapy was administered during the same time period and involved two cycles of fluorouracil and cisplatin infusions. All patients in this group were clinically reevaluated 2-4 weeks after completing this regimen, and surgery was performed soon afterward.

Surgery comprised a transthoracic esophagectomy with extended two-field lymphadenectomy and either high intrathoracic anastomosis (for tumors with an infracarinal proximal margin) or cervical anastomosis (for tumors with a proximal margin above the carina).

Median follow-up was 7.8 years. There were 125 deaths: 62.4% of the intervention group died, as did 66% of the surgery-only group, a nonsignificant difference, the investigators said (J. Clin. Oncol. 2014 June 30 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.53.6532]).

Median overall survival was 31.8 months in the intervention group and 41.2 months in the surgery-only group, a nonsignificant difference. Similarly, 3-year overall survival was 47.5% and 5-year overall survival was 41.1% in the intervention group, compared with 53% and 33.8%, respectively, in the surgery-only group, which were also nonsignificant differences.

The rate of curative resection also was not significantly different between the intervention group (93.8%) and the surgery-only group (92.1%), indicating that reducing the tumor with chemotherapy and radiotherapy had no beneficial effect in these early-stage cancers. Previous studies have demonstrated that such downsizing is effective in more advanced esophageal cancers, Dr. Mariette and his associates noted.

Postoperative mortality was more than threefold higher among patients who underwent preoperative chemoradiotherapy (11.1%) than in the surgery-only group (3.4%). The causes of postoperative death included aortic rupture, uncontrollable chylothorax, anastomotic leak, gastric conduit necrosis, mesenteric and lower limb ischemia, and acute RDS in the intervention group, compared with pneumonia and acute RDS in the surgery-only group.

These findings suggest that preoperative chemoradiotherapy "is not the appropriate neoadjuvant therapeutic strategy for stage I or II esophageal cancer," the investigators said.

Since patients with early-stage esophageal cancer don’t appear to benefit from preoperative neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, perhaps it is time to consider a different approach: definitive rather than neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy as the first-line treatment, said Dr. Brian G. Czito, Dr. Manisha Palta, and Dr. Christopher G. Willett.

Some medical centers have already adopted this approach for patients with potentially curable esophageal cancer, reserving surgery as salvage treatment. Compared with surgery as first-line treatment, definitive chemoradiotherapy is associated with a lower rate of treatment-related mortality and similar survival outcomes, they noted.

Dr. Czito, Dr. Palta, and Dr. Willett are in the department of radiation oncology at Duke Cancer Institute, Durham, N.C. They reported no financial conflicts of interest. These remarks were taken from their editorial accompanying Dr. Mariette’s report (J. Clin. Oncol. 2014 June 30 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.53.6532]).

Since patients with early-stage esophageal cancer don’t appear to benefit from preoperative neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, perhaps it is time to consider a different approach: definitive rather than neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy as the first-line treatment, said Dr. Brian G. Czito, Dr. Manisha Palta, and Dr. Christopher G. Willett.

Some medical centers have already adopted this approach for patients with potentially curable esophageal cancer, reserving surgery as salvage treatment. Compared with surgery as first-line treatment, definitive chemoradiotherapy is associated with a lower rate of treatment-related mortality and similar survival outcomes, they noted.

Dr. Czito, Dr. Palta, and Dr. Willett are in the department of radiation oncology at Duke Cancer Institute, Durham, N.C. They reported no financial conflicts of interest. These remarks were taken from their editorial accompanying Dr. Mariette’s report (J. Clin. Oncol. 2014 June 30 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.53.6532]).

Since patients with early-stage esophageal cancer don’t appear to benefit from preoperative neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, perhaps it is time to consider a different approach: definitive rather than neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy as the first-line treatment, said Dr. Brian G. Czito, Dr. Manisha Palta, and Dr. Christopher G. Willett.

Some medical centers have already adopted this approach for patients with potentially curable esophageal cancer, reserving surgery as salvage treatment. Compared with surgery as first-line treatment, definitive chemoradiotherapy is associated with a lower rate of treatment-related mortality and similar survival outcomes, they noted.

Dr. Czito, Dr. Palta, and Dr. Willett are in the department of radiation oncology at Duke Cancer Institute, Durham, N.C. They reported no financial conflicts of interest. These remarks were taken from their editorial accompanying Dr. Mariette’s report (J. Clin. Oncol. 2014 June 30 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.53.6532]).

For patients with early-stage esophageal cancer, undergoing chemotherapy and radiotherapy before surgical excision failed to improve the rate of curative resection and, most importantly, failed to boost survival in a phase III clinical trial, according to a report published online June 30 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Unfortunately this treatment strategy also tripled postoperative mortality, making the risk-benefit ratio even more lopsided for this patient population, said Dr. Christophe Mariette of the department of digestive and oncologic surgery, University Hospital Claude Huriez-Regional University Hospital Center, Lille (France), and his associates.

Clinical trials examining neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for esophageal cancer have produced conflicting results, with some showing that the approach is effective, in some cases doubling median survival, while others showed no benefit. Most such studies have been limited by small sample sizes, heterogeneity of tumor types, variations in radiation doses and chemotherapy regiments, and differences in preoperative staging techniques and the adequacy of surgical resections. Moreover, the number of study participants with early-stage esophageal cancer has been very small because most patients already have more advanced disease at presentation, the investigators noted.

For their study, Dr. Mariette and his associates confined the cohort to patients younger than 75 years with treatment-naive esophageal adenocarcinoma or squamous-cell carcinoma judged to be stage I or II using thoracoabdominal CT and endoscopic ultrasound; additional preoperative assessments using PET scanning, cervical ultrasound, or radionuclide bone scanning were optional. It required 9 years to enroll 195 patients at 30 French medical centers. These study participants were randomly assigned to receive either neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus radiotherapy before potentially curative surgery (98 subjects) or potentially curative surgery alone (97 subjects).

In the intervention group, radiotherapy involved a total dose of 45 Gy delivered in 25 fractions over the course of 5 weeks. Chemotherapy was administered during the same time period and involved two cycles of fluorouracil and cisplatin infusions. All patients in this group were clinically reevaluated 2-4 weeks after completing this regimen, and surgery was performed soon afterward.

Surgery comprised a transthoracic esophagectomy with extended two-field lymphadenectomy and either high intrathoracic anastomosis (for tumors with an infracarinal proximal margin) or cervical anastomosis (for tumors with a proximal margin above the carina).

Median follow-up was 7.8 years. There were 125 deaths: 62.4% of the intervention group died, as did 66% of the surgery-only group, a nonsignificant difference, the investigators said (J. Clin. Oncol. 2014 June 30 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.53.6532]).

Median overall survival was 31.8 months in the intervention group and 41.2 months in the surgery-only group, a nonsignificant difference. Similarly, 3-year overall survival was 47.5% and 5-year overall survival was 41.1% in the intervention group, compared with 53% and 33.8%, respectively, in the surgery-only group, which were also nonsignificant differences.

The rate of curative resection also was not significantly different between the intervention group (93.8%) and the surgery-only group (92.1%), indicating that reducing the tumor with chemotherapy and radiotherapy had no beneficial effect in these early-stage cancers. Previous studies have demonstrated that such downsizing is effective in more advanced esophageal cancers, Dr. Mariette and his associates noted.

Postoperative mortality was more than threefold higher among patients who underwent preoperative chemoradiotherapy (11.1%) than in the surgery-only group (3.4%). The causes of postoperative death included aortic rupture, uncontrollable chylothorax, anastomotic leak, gastric conduit necrosis, mesenteric and lower limb ischemia, and acute RDS in the intervention group, compared with pneumonia and acute RDS in the surgery-only group.

These findings suggest that preoperative chemoradiotherapy "is not the appropriate neoadjuvant therapeutic strategy for stage I or II esophageal cancer," the investigators said.

For patients with early-stage esophageal cancer, undergoing chemotherapy and radiotherapy before surgical excision failed to improve the rate of curative resection and, most importantly, failed to boost survival in a phase III clinical trial, according to a report published online June 30 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Unfortunately this treatment strategy also tripled postoperative mortality, making the risk-benefit ratio even more lopsided for this patient population, said Dr. Christophe Mariette of the department of digestive and oncologic surgery, University Hospital Claude Huriez-Regional University Hospital Center, Lille (France), and his associates.

Clinical trials examining neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for esophageal cancer have produced conflicting results, with some showing that the approach is effective, in some cases doubling median survival, while others showed no benefit. Most such studies have been limited by small sample sizes, heterogeneity of tumor types, variations in radiation doses and chemotherapy regiments, and differences in preoperative staging techniques and the adequacy of surgical resections. Moreover, the number of study participants with early-stage esophageal cancer has been very small because most patients already have more advanced disease at presentation, the investigators noted.

For their study, Dr. Mariette and his associates confined the cohort to patients younger than 75 years with treatment-naive esophageal adenocarcinoma or squamous-cell carcinoma judged to be stage I or II using thoracoabdominal CT and endoscopic ultrasound; additional preoperative assessments using PET scanning, cervical ultrasound, or radionuclide bone scanning were optional. It required 9 years to enroll 195 patients at 30 French medical centers. These study participants were randomly assigned to receive either neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus radiotherapy before potentially curative surgery (98 subjects) or potentially curative surgery alone (97 subjects).

In the intervention group, radiotherapy involved a total dose of 45 Gy delivered in 25 fractions over the course of 5 weeks. Chemotherapy was administered during the same time period and involved two cycles of fluorouracil and cisplatin infusions. All patients in this group were clinically reevaluated 2-4 weeks after completing this regimen, and surgery was performed soon afterward.

Surgery comprised a transthoracic esophagectomy with extended two-field lymphadenectomy and either high intrathoracic anastomosis (for tumors with an infracarinal proximal margin) or cervical anastomosis (for tumors with a proximal margin above the carina).

Median follow-up was 7.8 years. There were 125 deaths: 62.4% of the intervention group died, as did 66% of the surgery-only group, a nonsignificant difference, the investigators said (J. Clin. Oncol. 2014 June 30 [doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.53.6532]).

Median overall survival was 31.8 months in the intervention group and 41.2 months in the surgery-only group, a nonsignificant difference. Similarly, 3-year overall survival was 47.5% and 5-year overall survival was 41.1% in the intervention group, compared with 53% and 33.8%, respectively, in the surgery-only group, which were also nonsignificant differences.

The rate of curative resection also was not significantly different between the intervention group (93.8%) and the surgery-only group (92.1%), indicating that reducing the tumor with chemotherapy and radiotherapy had no beneficial effect in these early-stage cancers. Previous studies have demonstrated that such downsizing is effective in more advanced esophageal cancers, Dr. Mariette and his associates noted.

Postoperative mortality was more than threefold higher among patients who underwent preoperative chemoradiotherapy (11.1%) than in the surgery-only group (3.4%). The causes of postoperative death included aortic rupture, uncontrollable chylothorax, anastomotic leak, gastric conduit necrosis, mesenteric and lower limb ischemia, and acute RDS in the intervention group, compared with pneumonia and acute RDS in the surgery-only group.

These findings suggest that preoperative chemoradiotherapy "is not the appropriate neoadjuvant therapeutic strategy for stage I or II esophageal cancer," the investigators said.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Don’t postpone surgery for esophageal cancer to perform chemoradiotherapy.

Major finding: Median overall survival was 31.8 months in the intervention group and 41.2 months in the surgery-only group; 3-year overall survival was 47.5% and 5-year overall survival was 41.1% in the intervention group, compared with 53% and 33.8%, respectively, in the surgery-only group. All these differences are nonsignificant.

Data source: A multicenter randomized phase III clinical trial involving 98 patients treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and 97 treated with surgery alone for early-stage esophageal cancer, who were followed for a median of approximately 8 years.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the French National Cancer Institute’s Programme Hospitalier pour la Recherche Clinque and Lille University Hospital; it received no commercial support. Dr. Mariette reported no financial conflicts of interest; one of his associates reported ties to Roche and Merck.

Endofibrinolysis a 'game changer' in acute PE

WASHINGTON – Ultrasound-facilitated, catheter-directed, low-dose fibrinolysis for acute massive or submassive pulmonary embolism significantly improves right ventricular function, reduces pulmonary hypertension and angiographic evidence of obstruction, and lessens the risk of fibrinolysis-associated intracranial hemorrhage, according to a prospective multicenter clinical trial.

"By minimizing the risk of intracranial bleeding, ultrasound-facilitated, catheter-directed, low-dose fibrinolysis represents a potential game changer in the treatment of high-risk pulmonary embolism patients," Dr. Gregory Piazza said in presenting the results of the SEATTLE II study at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Full-dose systemic fibrinolysis has long been the go-to advanced therapy for high-risk pulmonary embolism (PE), but physicians are leery of the associated 2%-3% risk of catastrophic intracranial hemorrhage, noted Dr. Piazza of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard University, Boston.

SEATTLE II was a single-arm, 21-site, prospective study in which 150 patients with high-risk PE underwent treatment using the commercially available EKOS EkoSonic Endovascular System.

Twenty-one percent of patients had massive PE, defined as presentation with syncope, cardiogenic shock, resuscitated cardiac arrest, or persistent hypotension. The remaining 79% had submassive PE, with normal blood pressure but evidence of right ventricular dysfunction. All participants had to have a right ventricular/left ventricular ratio (RV/LV) of 0.9 or greater on the same chest CT scan used in diagnosing the PE. This CT documentation of RV dysfunction has been associated in a meta-analysis of patients with submassive PE with a 7.4-fold increased risk of death from PE, compared with normotensive PE patients with normal RV function (J. Thromb. Haemost. 2013;11:1823-32).

The primary endpoint was change in RV/LV on chest CT from baseline to 48 hours after initiation of fibrinolysis. This ratio improved from 1.55 to 1.13, for a statistically and clinically significant 27% reduction. A similar-size improvement was seen in pulmonary artery systolic pressure – a secondary efficacy endpoint – which decreased from 51.4 mm Hg before treatment to 37.5 mm Hg post procedure and 36.9 mm Hg at 48 hours. Both efficacy endpoints improved to a similar extent regardless of whether patients had massive or submassive PE.

The mean Modified Miller Pulmonary Artery Angiographic Obstruction Score improved by 30%, from 22.5 pretreatment to 15.8 at 48 hours.

Three in-hospital deaths occurred. One was due to massive PE that occurred before the fibrinolysis procedure could be completed. The others were not directly attributable to PE: One involved overwhelming sepsis and the other was due to progressive respiratory failure. Major bleeding occurred in 11% of patients; however, 16 of the 17 events were classified as GUSTO moderate bleeds, with only a single GUSTO severe hemorrhage.

There were no intracranial hemorrhages.

The fibrinolytic agent used in SEATTLE II was tissue plasminogen activator, delivered at 1 mg/hr for a total dose of 24 mg. Patients with unilateral PE received a single device and 24 hours of infusion time. The 86% of patients who had bilateral disease got two devices and 12 hours of therapy.

The proprietary EKOS system consists of two catheters: an outer infusion catheter with side holes that elute the fibrinolytic agent, and an inner-core catheter with ultrasound transducers placed at regular intervals. These transducers produce low-intensity ultrasound that serves two purposes. Through a process called acoustic streaming, the low-intensity ultrasound helps push the fibrinolytic agent closer to the thrombus. Plus, the ultrasound energy causes the clot fibrin to reconfigure from a tight lattice to a more porous structure that promotes deeper penetration of the fibrinolytic, Dr. Piazza explained.

Dr. Piazza said the next step in defining the EKOS system’s role in clinical practice will be to study briefer infusion times as a means of achieving faster patient improvement with reduced use of hospital resources.

The EKOS system has been approved in the United States since 2005 for treatment of blood clots in the arms and legs. In Europe it gained an additional indication for treatment of massive and submassive PE in 2011.

The SEATTLE II study was sponsored by EKOS Corp. Dr. Piazza reported receiving a research grant from the company.

WASHINGTON – Ultrasound-facilitated, catheter-directed, low-dose fibrinolysis for acute massive or submassive pulmonary embolism significantly improves right ventricular function, reduces pulmonary hypertension and angiographic evidence of obstruction, and lessens the risk of fibrinolysis-associated intracranial hemorrhage, according to a prospective multicenter clinical trial.

"By minimizing the risk of intracranial bleeding, ultrasound-facilitated, catheter-directed, low-dose fibrinolysis represents a potential game changer in the treatment of high-risk pulmonary embolism patients," Dr. Gregory Piazza said in presenting the results of the SEATTLE II study at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Full-dose systemic fibrinolysis has long been the go-to advanced therapy for high-risk pulmonary embolism (PE), but physicians are leery of the associated 2%-3% risk of catastrophic intracranial hemorrhage, noted Dr. Piazza of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard University, Boston.

SEATTLE II was a single-arm, 21-site, prospective study in which 150 patients with high-risk PE underwent treatment using the commercially available EKOS EkoSonic Endovascular System.

Twenty-one percent of patients had massive PE, defined as presentation with syncope, cardiogenic shock, resuscitated cardiac arrest, or persistent hypotension. The remaining 79% had submassive PE, with normal blood pressure but evidence of right ventricular dysfunction. All participants had to have a right ventricular/left ventricular ratio (RV/LV) of 0.9 or greater on the same chest CT scan used in diagnosing the PE. This CT documentation of RV dysfunction has been associated in a meta-analysis of patients with submassive PE with a 7.4-fold increased risk of death from PE, compared with normotensive PE patients with normal RV function (J. Thromb. Haemost. 2013;11:1823-32).

The primary endpoint was change in RV/LV on chest CT from baseline to 48 hours after initiation of fibrinolysis. This ratio improved from 1.55 to 1.13, for a statistically and clinically significant 27% reduction. A similar-size improvement was seen in pulmonary artery systolic pressure – a secondary efficacy endpoint – which decreased from 51.4 mm Hg before treatment to 37.5 mm Hg post procedure and 36.9 mm Hg at 48 hours. Both efficacy endpoints improved to a similar extent regardless of whether patients had massive or submassive PE.

The mean Modified Miller Pulmonary Artery Angiographic Obstruction Score improved by 30%, from 22.5 pretreatment to 15.8 at 48 hours.

Three in-hospital deaths occurred. One was due to massive PE that occurred before the fibrinolysis procedure could be completed. The others were not directly attributable to PE: One involved overwhelming sepsis and the other was due to progressive respiratory failure. Major bleeding occurred in 11% of patients; however, 16 of the 17 events were classified as GUSTO moderate bleeds, with only a single GUSTO severe hemorrhage.

There were no intracranial hemorrhages.

The fibrinolytic agent used in SEATTLE II was tissue plasminogen activator, delivered at 1 mg/hr for a total dose of 24 mg. Patients with unilateral PE received a single device and 24 hours of infusion time. The 86% of patients who had bilateral disease got two devices and 12 hours of therapy.

The proprietary EKOS system consists of two catheters: an outer infusion catheter with side holes that elute the fibrinolytic agent, and an inner-core catheter with ultrasound transducers placed at regular intervals. These transducers produce low-intensity ultrasound that serves two purposes. Through a process called acoustic streaming, the low-intensity ultrasound helps push the fibrinolytic agent closer to the thrombus. Plus, the ultrasound energy causes the clot fibrin to reconfigure from a tight lattice to a more porous structure that promotes deeper penetration of the fibrinolytic, Dr. Piazza explained.

Dr. Piazza said the next step in defining the EKOS system’s role in clinical practice will be to study briefer infusion times as a means of achieving faster patient improvement with reduced use of hospital resources.

The EKOS system has been approved in the United States since 2005 for treatment of blood clots in the arms and legs. In Europe it gained an additional indication for treatment of massive and submassive PE in 2011.

The SEATTLE II study was sponsored by EKOS Corp. Dr. Piazza reported receiving a research grant from the company.

WASHINGTON – Ultrasound-facilitated, catheter-directed, low-dose fibrinolysis for acute massive or submassive pulmonary embolism significantly improves right ventricular function, reduces pulmonary hypertension and angiographic evidence of obstruction, and lessens the risk of fibrinolysis-associated intracranial hemorrhage, according to a prospective multicenter clinical trial.

"By minimizing the risk of intracranial bleeding, ultrasound-facilitated, catheter-directed, low-dose fibrinolysis represents a potential game changer in the treatment of high-risk pulmonary embolism patients," Dr. Gregory Piazza said in presenting the results of the SEATTLE II study at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Full-dose systemic fibrinolysis has long been the go-to advanced therapy for high-risk pulmonary embolism (PE), but physicians are leery of the associated 2%-3% risk of catastrophic intracranial hemorrhage, noted Dr. Piazza of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard University, Boston.

SEATTLE II was a single-arm, 21-site, prospective study in which 150 patients with high-risk PE underwent treatment using the commercially available EKOS EkoSonic Endovascular System.

Twenty-one percent of patients had massive PE, defined as presentation with syncope, cardiogenic shock, resuscitated cardiac arrest, or persistent hypotension. The remaining 79% had submassive PE, with normal blood pressure but evidence of right ventricular dysfunction. All participants had to have a right ventricular/left ventricular ratio (RV/LV) of 0.9 or greater on the same chest CT scan used in diagnosing the PE. This CT documentation of RV dysfunction has been associated in a meta-analysis of patients with submassive PE with a 7.4-fold increased risk of death from PE, compared with normotensive PE patients with normal RV function (J. Thromb. Haemost. 2013;11:1823-32).

The primary endpoint was change in RV/LV on chest CT from baseline to 48 hours after initiation of fibrinolysis. This ratio improved from 1.55 to 1.13, for a statistically and clinically significant 27% reduction. A similar-size improvement was seen in pulmonary artery systolic pressure – a secondary efficacy endpoint – which decreased from 51.4 mm Hg before treatment to 37.5 mm Hg post procedure and 36.9 mm Hg at 48 hours. Both efficacy endpoints improved to a similar extent regardless of whether patients had massive or submassive PE.

The mean Modified Miller Pulmonary Artery Angiographic Obstruction Score improved by 30%, from 22.5 pretreatment to 15.8 at 48 hours.

Three in-hospital deaths occurred. One was due to massive PE that occurred before the fibrinolysis procedure could be completed. The others were not directly attributable to PE: One involved overwhelming sepsis and the other was due to progressive respiratory failure. Major bleeding occurred in 11% of patients; however, 16 of the 17 events were classified as GUSTO moderate bleeds, with only a single GUSTO severe hemorrhage.

There were no intracranial hemorrhages.

The fibrinolytic agent used in SEATTLE II was tissue plasminogen activator, delivered at 1 mg/hr for a total dose of 24 mg. Patients with unilateral PE received a single device and 24 hours of infusion time. The 86% of patients who had bilateral disease got two devices and 12 hours of therapy.

The proprietary EKOS system consists of two catheters: an outer infusion catheter with side holes that elute the fibrinolytic agent, and an inner-core catheter with ultrasound transducers placed at regular intervals. These transducers produce low-intensity ultrasound that serves two purposes. Through a process called acoustic streaming, the low-intensity ultrasound helps push the fibrinolytic agent closer to the thrombus. Plus, the ultrasound energy causes the clot fibrin to reconfigure from a tight lattice to a more porous structure that promotes deeper penetration of the fibrinolytic, Dr. Piazza explained.

Dr. Piazza said the next step in defining the EKOS system’s role in clinical practice will be to study briefer infusion times as a means of achieving faster patient improvement with reduced use of hospital resources.

The EKOS system has been approved in the United States since 2005 for treatment of blood clots in the arms and legs. In Europe it gained an additional indication for treatment of massive and submassive PE in 2011.

The SEATTLE II study was sponsored by EKOS Corp. Dr. Piazza reported receiving a research grant from the company.

Early endoscopic follow-up nets dysplasia in 9.5% of Barrett’s

CHICAGO – Early endoscopic follow-up within 24 months detected dysplasia in nearly one in 10 patients with nondysplastic or low-grade Barrett’s esophagus in a retrospective study at the Mayo Clinic.

Initial endoscopy missed four cases of high-grade dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma (1.9%) and 16 cases of low-grade dysplasia (7.6%) for an overall miss-rate of 9.5%.

Patients on proton pump inhibitors were less likely to have dysplasia missed than were those off PPIs (20% vs. 52.6%, P = .008).

Those with long- versus short-segment Barrett’s esophagus were more likely to have dysplasia overlooked (85% vs. 53.6%; P = .008; mean 6 mm vs. 4 mm; P = .006), Dr. Kavel Visrodia said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Current American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines recommend early repeat esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) to exclude the presence of missed dysplasia in newly diagnosed nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus (BE), while the ACG and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy call for repeat EGD within 6 months for those with low-grade dysplasia.

The yield for repeat EGD has not been established, and only one study exists in the literature, said Dr. Visrodia of the department of medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

That study (Dis. Esophagus 2012 Sept. 28. [doi:10.1111/j.1442-2050.2012.01431.x]) showed a miss-rate of 8.2% among 146 patients with newly diagnosed nondysplastic BE. Long-segment BE was the only significant predictor of dysplasia on follow-up (odds ratio, 9.18; P = .008).

The cohort was relatively small and had no long-term follow-up, and with an interval to follow-up of 36 months, "it’s possible that some of these were actually incident cases of dysplasia and not prevalent cases," he said.

To address these gaps, Dr. Visrodia and his colleagues identified 488 BE cases from 1977 to 2011 in the Rochester Epidemiology Project in Olmsted County, Minn. A total of 278 patients were excluded because of high-grade dysplasia (HGD) or esophageal cancer on index endoscopy or repeat endoscopy after 24 months, leaving 181 patients with nondysplastic BE and 29 with low-grade dysplasia (LGD).

Repeat endoscopy within 24 months revealed 2 cases of HGD or cancer and 16 cases of LGD in the nondysplastic BE group, and 2 cases of HGD or cancer in the LGD group, Dr. Visrodia said.

Three of the four HGD/cancer cases were in patients with long-segment BE, defined as at least 3 cm of columnar mucosa.

Biopsies were insufficient in 63% of patients with missed dysplasia, compared with 55% in the group without missed dysplasia. Biopsies were considered adequate if the number of biopsies divided by the BE length was at least 2, indicating that samples were taken every 2 cm in accordance with guidelines. This risk factor is noteworthy, although the difference between groups was not statistically significant, possibly because of the small sample size, he said.

Finally, after a median of 6.8 years of follow-up, 30 asymptomatic, prevalent HGDs or cancers were detected within 24 months, compared with 22 incident cases detected after 24 months. This suggests that "a greater number of high-grade dysplasias and cancers were detected up front rather than during long-term careful surveillance," Dr. Visrodia said.

During a discussion of the study, one attendee asked whether the results make a better case for aggressive ablation up front rather than for surveillance, while others expressed surprise at the high miss rate at an institution such as the Mayo Clinic.

Dr. Visrodia replied that the results do give them pause, and suggested that tighter early endoscopic surveillance may be warranted, particularly in those with long-segment BE.

Dr. Visrodia and his coauthors reported no financial disclosures.

CHICAGO – Early endoscopic follow-up within 24 months detected dysplasia in nearly one in 10 patients with nondysplastic or low-grade Barrett’s esophagus in a retrospective study at the Mayo Clinic.

Initial endoscopy missed four cases of high-grade dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma (1.9%) and 16 cases of low-grade dysplasia (7.6%) for an overall miss-rate of 9.5%.

Patients on proton pump inhibitors were less likely to have dysplasia missed than were those off PPIs (20% vs. 52.6%, P = .008).

Those with long- versus short-segment Barrett’s esophagus were more likely to have dysplasia overlooked (85% vs. 53.6%; P = .008; mean 6 mm vs. 4 mm; P = .006), Dr. Kavel Visrodia said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Current American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines recommend early repeat esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) to exclude the presence of missed dysplasia in newly diagnosed nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus (BE), while the ACG and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy call for repeat EGD within 6 months for those with low-grade dysplasia.

The yield for repeat EGD has not been established, and only one study exists in the literature, said Dr. Visrodia of the department of medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

That study (Dis. Esophagus 2012 Sept. 28. [doi:10.1111/j.1442-2050.2012.01431.x]) showed a miss-rate of 8.2% among 146 patients with newly diagnosed nondysplastic BE. Long-segment BE was the only significant predictor of dysplasia on follow-up (odds ratio, 9.18; P = .008).

The cohort was relatively small and had no long-term follow-up, and with an interval to follow-up of 36 months, "it’s possible that some of these were actually incident cases of dysplasia and not prevalent cases," he said.