User login

C. difficile risk score identifies high-risk patients

Researchers have created a risk score to help identify patients at high risk for Clostridium difficile infection after hospitalization, for future use in vaccine trials, according to a new study.

C. difficile is the most common pathogen type in health care–associated infections and the leading cause of enterocolitis-associated deaths. Identification of patients who are at high risk for C. difficile is important in the development of future vaccines.

Dr. James Baggs, epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and his colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study to identify groups at high risk for C. difficile infection (CDI) for future vaccine trials. Their results were published in Vaccine online Oct. 9.

Data on medications and discharge were obtained from two large academic medical centers in Connecticut and New York. This information was linked to surveillance data from the Emerging Infections Program on active population-based CDIs. Participants were included if they had a hospital stay without a history of CDI with a primary outcome of infection 28 days or more after discharge.

To identify predictors of CDI after discharge, the investigators used a backward elimination employing a Cox proportional hazards model. They then created a CDI risk index based on the predictors.

During the study period, a total of 35,186 index hospitalizations were identified in Connecticut and New York. CDI diagnosis 28 days or more after discharge was observed in 288 patients (0.82%).

Initial models did not perform well in cross-site validation; however, a combined model that included age, past hospitalizations, use of 3rd/4th generation cephalosporin, clindamycin, or fluoroquinolone antibiotics was developed. This validation cohort resulted in a risk score that was predictive (P less than .001).

Finally, the study participants were divided into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the distribution of scores in the cohort. The low-risk group experienced CDI diagnosis 28 days or more after hospitalization at a rate of 0.3% versus 1.6% in the high-risk group.

“Our study identified specific parameters for a risk index that can be applied at hospital discharge to identify a patient population with increased risk of CDI [greater than or equal to] 28 days after discharge that could be targeted for vaccine trials,” Dr. Braggs and his coauthors wrote.

The authors noted several limitations to the study. For example, they indicated that data was obtained from two hospitals which may not represent some minority populations. Therefore, data from other hospitals may be able to help identify if the risk index is generalizable.

No conflicts of interest were reported. The study was partially funded by GlaxoSmithKline through the CDC Foundation, and GSK had the opportunity to review the preliminary manuscript.

Researchers have created a risk score to help identify patients at high risk for Clostridium difficile infection after hospitalization, for future use in vaccine trials, according to a new study.

C. difficile is the most common pathogen type in health care–associated infections and the leading cause of enterocolitis-associated deaths. Identification of patients who are at high risk for C. difficile is important in the development of future vaccines.

Dr. James Baggs, epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and his colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study to identify groups at high risk for C. difficile infection (CDI) for future vaccine trials. Their results were published in Vaccine online Oct. 9.

Data on medications and discharge were obtained from two large academic medical centers in Connecticut and New York. This information was linked to surveillance data from the Emerging Infections Program on active population-based CDIs. Participants were included if they had a hospital stay without a history of CDI with a primary outcome of infection 28 days or more after discharge.

To identify predictors of CDI after discharge, the investigators used a backward elimination employing a Cox proportional hazards model. They then created a CDI risk index based on the predictors.

During the study period, a total of 35,186 index hospitalizations were identified in Connecticut and New York. CDI diagnosis 28 days or more after discharge was observed in 288 patients (0.82%).

Initial models did not perform well in cross-site validation; however, a combined model that included age, past hospitalizations, use of 3rd/4th generation cephalosporin, clindamycin, or fluoroquinolone antibiotics was developed. This validation cohort resulted in a risk score that was predictive (P less than .001).

Finally, the study participants were divided into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the distribution of scores in the cohort. The low-risk group experienced CDI diagnosis 28 days or more after hospitalization at a rate of 0.3% versus 1.6% in the high-risk group.

“Our study identified specific parameters for a risk index that can be applied at hospital discharge to identify a patient population with increased risk of CDI [greater than or equal to] 28 days after discharge that could be targeted for vaccine trials,” Dr. Braggs and his coauthors wrote.

The authors noted several limitations to the study. For example, they indicated that data was obtained from two hospitals which may not represent some minority populations. Therefore, data from other hospitals may be able to help identify if the risk index is generalizable.

No conflicts of interest were reported. The study was partially funded by GlaxoSmithKline through the CDC Foundation, and GSK had the opportunity to review the preliminary manuscript.

Researchers have created a risk score to help identify patients at high risk for Clostridium difficile infection after hospitalization, for future use in vaccine trials, according to a new study.

C. difficile is the most common pathogen type in health care–associated infections and the leading cause of enterocolitis-associated deaths. Identification of patients who are at high risk for C. difficile is important in the development of future vaccines.

Dr. James Baggs, epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and his colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study to identify groups at high risk for C. difficile infection (CDI) for future vaccine trials. Their results were published in Vaccine online Oct. 9.

Data on medications and discharge were obtained from two large academic medical centers in Connecticut and New York. This information was linked to surveillance data from the Emerging Infections Program on active population-based CDIs. Participants were included if they had a hospital stay without a history of CDI with a primary outcome of infection 28 days or more after discharge.

To identify predictors of CDI after discharge, the investigators used a backward elimination employing a Cox proportional hazards model. They then created a CDI risk index based on the predictors.

During the study period, a total of 35,186 index hospitalizations were identified in Connecticut and New York. CDI diagnosis 28 days or more after discharge was observed in 288 patients (0.82%).

Initial models did not perform well in cross-site validation; however, a combined model that included age, past hospitalizations, use of 3rd/4th generation cephalosporin, clindamycin, or fluoroquinolone antibiotics was developed. This validation cohort resulted in a risk score that was predictive (P less than .001).

Finally, the study participants were divided into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the distribution of scores in the cohort. The low-risk group experienced CDI diagnosis 28 days or more after hospitalization at a rate of 0.3% versus 1.6% in the high-risk group.

“Our study identified specific parameters for a risk index that can be applied at hospital discharge to identify a patient population with increased risk of CDI [greater than or equal to] 28 days after discharge that could be targeted for vaccine trials,” Dr. Braggs and his coauthors wrote.

The authors noted several limitations to the study. For example, they indicated that data was obtained from two hospitals which may not represent some minority populations. Therefore, data from other hospitals may be able to help identify if the risk index is generalizable.

No conflicts of interest were reported. The study was partially funded by GlaxoSmithKline through the CDC Foundation, and GSK had the opportunity to review the preliminary manuscript.

FROM VACCINE

Key clinical point: Researchers have created a risk score identifying patients at high risk for C. difficile infection after hospitalization, for future use in vaccine trials.

Major finding: A combined model which included age, past hospitalizations, use of 3rd/4th generation cephalosporin, clindamycin, or fluoroquinolone antibiotics resulted in a predictive risk score (P less than .001).

Data source: A retrospective cohort study with data from two large academic medical centers in Connecticut and New York which was linked to surveillance data from the Emerging Infections Program.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were reported. The study was partially funded by GlaxoSmithKline through the CDC Foundation, and GSK had the opportunity to review the preliminary manuscript.

Experts debate infection control merits of ‘bare beneath the elbows’

SAN DIEGO – Going tieless and “bare beneath the elbows” has been touted for infection control. But while some clinicians endorse the practice, others call it inconvenient, unprofessional, and distracting. At an annual conference on infectious diseases, two specialists in the field debated going “BBE” and its evidence base.

Widespread practice of BBE dates to at least 2008, when the National Health Service in the United Kingdom mandated it as part of a set of measures to decrease nosocomial transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Clostridium difficile. Clinicians at NHS were directed to leave jewelry, neckties, and wrist watches at home, hang up their lab coats, and wear short sleeves. The policy aims not only to reduce points of physical contact between providers and patients, but also to improve hand and wrist washing, said Dr. Michael Edmond, who is at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics in Iowa City.

Some evidence supports going BBE, said Dr. Edmond. Pathogenic gram-negative rods have been cultured from neckties, scrubs, uniforms, and white coats in multiple studies, he added. Inadequate laundering is part of the problem – clinical faculty in one study reported washing their coats about once every 2 weeks, even less often than medical students did.

“So when is biological plausibility enough to support a change in practice?” Dr. Edmond asked. “There is a potential for benefit in going BBE. There is no risk for harm. And there is minimal cost. On the basis of the same evidence and assumptions, we are willing to wrap ourselves in plastic and confine patients to their hospital rooms – that is, to use contact precautions. And yet, we are not willing to eliminate white coats and ties.”

Patient perception is not at issue, Dr. Edmond argued. Only about half of patients at one British hospital said they wanted physicians to wear traditional white coats, and that proportion dropped to 22% after patients received educational materials on clothing contamination, he noted. In another study, patients ranked their physician’s appearance behind knowledge, compassion, and politeness when asked which characteristics they valued most.

“Without strong evidence for benefit, we should recommend – not mandate – this new practice,” Dr. Edmond concluded.

But Dr. Neil O. Fishman disagreed, calling BBE “an evidence-free zone.” Dr. Fishman, who is at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, noted a total lack of randomized, controlled trials or well-performed observational studies supporting BBE. “No clinical studies have demonstrated cross-transmission of health care–associated pathogens from a health care provider to a patient,” he said.

Moreover, BBE does not prevent contamination, Dr. Fishman said. Bacterial cultures of the hands of BBE clinicians and controls revealed no differences in total bacteria counts or numbers of clinically significant pathogens, he said. Cultures of white coats and the undersides of wrists also were similar in terms of total bacteria and MRSA counts, he added.

Despite the lack of evidence, BBE has been implemented at NHS “mainly as a political gesture and has had unintended consequences,” Dr. Fishman said. Informal attire has promoted a less-robust view of infection control, junior doctors have adopted scruffy attire and “slovenly” personal hygiene, and all the focus on clothing has distracted from hand washing, he added.

Furthermore, less than 12% of clinicians have complied with BBE, according to Dr. Fishman. Abstainers report feeling cold and not knowing what time it is. Women, in particular, say they have no pockets to carry work essentials. “This is a gender equity issue,” Dr. Fishman said. “Can we afford to promote practices based on limited evidence, a theoretical rationale, or individual opinions? This is a lack of focus on what really matters.”

Dr. Edmond and Dr. Fishman reported no disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Going tieless and “bare beneath the elbows” has been touted for infection control. But while some clinicians endorse the practice, others call it inconvenient, unprofessional, and distracting. At an annual conference on infectious diseases, two specialists in the field debated going “BBE” and its evidence base.

Widespread practice of BBE dates to at least 2008, when the National Health Service in the United Kingdom mandated it as part of a set of measures to decrease nosocomial transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Clostridium difficile. Clinicians at NHS were directed to leave jewelry, neckties, and wrist watches at home, hang up their lab coats, and wear short sleeves. The policy aims not only to reduce points of physical contact between providers and patients, but also to improve hand and wrist washing, said Dr. Michael Edmond, who is at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics in Iowa City.

Some evidence supports going BBE, said Dr. Edmond. Pathogenic gram-negative rods have been cultured from neckties, scrubs, uniforms, and white coats in multiple studies, he added. Inadequate laundering is part of the problem – clinical faculty in one study reported washing their coats about once every 2 weeks, even less often than medical students did.

“So when is biological plausibility enough to support a change in practice?” Dr. Edmond asked. “There is a potential for benefit in going BBE. There is no risk for harm. And there is minimal cost. On the basis of the same evidence and assumptions, we are willing to wrap ourselves in plastic and confine patients to their hospital rooms – that is, to use contact precautions. And yet, we are not willing to eliminate white coats and ties.”

Patient perception is not at issue, Dr. Edmond argued. Only about half of patients at one British hospital said they wanted physicians to wear traditional white coats, and that proportion dropped to 22% after patients received educational materials on clothing contamination, he noted. In another study, patients ranked their physician’s appearance behind knowledge, compassion, and politeness when asked which characteristics they valued most.

“Without strong evidence for benefit, we should recommend – not mandate – this new practice,” Dr. Edmond concluded.

But Dr. Neil O. Fishman disagreed, calling BBE “an evidence-free zone.” Dr. Fishman, who is at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, noted a total lack of randomized, controlled trials or well-performed observational studies supporting BBE. “No clinical studies have demonstrated cross-transmission of health care–associated pathogens from a health care provider to a patient,” he said.

Moreover, BBE does not prevent contamination, Dr. Fishman said. Bacterial cultures of the hands of BBE clinicians and controls revealed no differences in total bacteria counts or numbers of clinically significant pathogens, he said. Cultures of white coats and the undersides of wrists also were similar in terms of total bacteria and MRSA counts, he added.

Despite the lack of evidence, BBE has been implemented at NHS “mainly as a political gesture and has had unintended consequences,” Dr. Fishman said. Informal attire has promoted a less-robust view of infection control, junior doctors have adopted scruffy attire and “slovenly” personal hygiene, and all the focus on clothing has distracted from hand washing, he added.

Furthermore, less than 12% of clinicians have complied with BBE, according to Dr. Fishman. Abstainers report feeling cold and not knowing what time it is. Women, in particular, say they have no pockets to carry work essentials. “This is a gender equity issue,” Dr. Fishman said. “Can we afford to promote practices based on limited evidence, a theoretical rationale, or individual opinions? This is a lack of focus on what really matters.”

Dr. Edmond and Dr. Fishman reported no disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Going tieless and “bare beneath the elbows” has been touted for infection control. But while some clinicians endorse the practice, others call it inconvenient, unprofessional, and distracting. At an annual conference on infectious diseases, two specialists in the field debated going “BBE” and its evidence base.

Widespread practice of BBE dates to at least 2008, when the National Health Service in the United Kingdom mandated it as part of a set of measures to decrease nosocomial transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Clostridium difficile. Clinicians at NHS were directed to leave jewelry, neckties, and wrist watches at home, hang up their lab coats, and wear short sleeves. The policy aims not only to reduce points of physical contact between providers and patients, but also to improve hand and wrist washing, said Dr. Michael Edmond, who is at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics in Iowa City.

Some evidence supports going BBE, said Dr. Edmond. Pathogenic gram-negative rods have been cultured from neckties, scrubs, uniforms, and white coats in multiple studies, he added. Inadequate laundering is part of the problem – clinical faculty in one study reported washing their coats about once every 2 weeks, even less often than medical students did.

“So when is biological plausibility enough to support a change in practice?” Dr. Edmond asked. “There is a potential for benefit in going BBE. There is no risk for harm. And there is minimal cost. On the basis of the same evidence and assumptions, we are willing to wrap ourselves in plastic and confine patients to their hospital rooms – that is, to use contact precautions. And yet, we are not willing to eliminate white coats and ties.”

Patient perception is not at issue, Dr. Edmond argued. Only about half of patients at one British hospital said they wanted physicians to wear traditional white coats, and that proportion dropped to 22% after patients received educational materials on clothing contamination, he noted. In another study, patients ranked their physician’s appearance behind knowledge, compassion, and politeness when asked which characteristics they valued most.

“Without strong evidence for benefit, we should recommend – not mandate – this new practice,” Dr. Edmond concluded.

But Dr. Neil O. Fishman disagreed, calling BBE “an evidence-free zone.” Dr. Fishman, who is at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, noted a total lack of randomized, controlled trials or well-performed observational studies supporting BBE. “No clinical studies have demonstrated cross-transmission of health care–associated pathogens from a health care provider to a patient,” he said.

Moreover, BBE does not prevent contamination, Dr. Fishman said. Bacterial cultures of the hands of BBE clinicians and controls revealed no differences in total bacteria counts or numbers of clinically significant pathogens, he said. Cultures of white coats and the undersides of wrists also were similar in terms of total bacteria and MRSA counts, he added.

Despite the lack of evidence, BBE has been implemented at NHS “mainly as a political gesture and has had unintended consequences,” Dr. Fishman said. Informal attire has promoted a less-robust view of infection control, junior doctors have adopted scruffy attire and “slovenly” personal hygiene, and all the focus on clothing has distracted from hand washing, he added.

Furthermore, less than 12% of clinicians have complied with BBE, according to Dr. Fishman. Abstainers report feeling cold and not knowing what time it is. Women, in particular, say they have no pockets to carry work essentials. “This is a gender equity issue,” Dr. Fishman said. “Can we afford to promote practices based on limited evidence, a theoretical rationale, or individual opinions? This is a lack of focus on what really matters.”

Dr. Edmond and Dr. Fishman reported no disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT IDWEEK 2015

IDWeek: VA found no evidence of CRE transmission through duodenoscopes

SAN DIEGO – Researchers found “no compelling evidence” that carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae were transmitted to Veterans Affairs patients during more than 55,000 endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and ultrasonography (EUS) procedures, Dr. Russell Ryono said at an annual meeting on infectious diseases.

The few clusters of cases uncovered by the 5-year retrospective analysis were separated not only in time, but by culture-negative patients treated with the same duodenoscopes at the same facilities, said Dr. Ryono of the public health surveillance and research office at the Department of Veterans Affairs in Palo Alto, Calif. “Our findings do not provide evidence of CRE transmission related to ERCP or EUS in Veterans Affairs,” Dr. Ryono and his associates concluded.

Contaminated duodenoscopes made headlines across the country this year after they caused outbreaks of fatal CRE infections in Los Angeles County. The Food and Drug Administration later acknowledged that the “complex design of the devices makes it difficult to remove contaminants compared to other types of endoscopes,” and both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and FDA recommended surveillance and reprocessing practices to help keep the scopes from transmitting serious infections.

In response to these concerns, the VA mined its data warehouses for ERCP and EUS procedures and CRE isolates recovered between January 2010 and the end of February 2015. Investigators looked for patients who were culture positive for the same type of CRE, underwent ERCP/EUS at the same facility within 6 months of each other, and were treated with the same scope or with an unidentified scope. Within this group, researchers honed in on “pairs” – or clusters – of patients in which the second patient exposed to the scope was CRE negative before the procedure and CRE positive afterward.

The initial query yielded more than 55,600 procedures among 40,329 veterans at 38 VA centers, as well as nearly 5,000 CRE isolates, more than half of which were cultured from urine samples, said Dr. Ryono. However, only 81 ERCP/EUS patients had CRE cultured from any anatomical site at any time. Among them, 57 patients were CRE negative before their procedure but CRE positive afterward, Dr. Ryono said.

There were 10 pairs of culture-positive patients treated at four facilities, one of which did not track serial numbers of duodenoscopes, according to Dr. Ryono. At that facility, procedure dates for pairs were 68-143 days apart, he said. Procedure dates for pairs at the other three facilities were spaced at least 82 days apart. Based on such extensive temporal spacing and the fact that the same scopes were used on culture-negative patients during intervening times, the investigators concluded that duodenoscopes were unlikely to have caused CRE infection or colonization.

Dr. Ryono noted several study limitations, however. Not only were CRE isolates unavailable for epidemiologic testing, but researchers also could not determine the extent to which facilities had implemented the 2010 guidelines for CLSI breakpoints. “Certainly, those facilities that have implemented those guidelines are more likely to catch CRE,” he said. Also, VA does not routinely screen patients for CRE before they undergo ERCP or EUS, “so it is very possible that some of our patients might have been colonized with CRE before the procedure, and we would not have been able to capture that,” he added. “Given the limitations of this review, the possibility that there was some transmission certainly cannot be completely excluded.”

Dr. Ryono reported these findings at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

The researchers declared no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Researchers found “no compelling evidence” that carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae were transmitted to Veterans Affairs patients during more than 55,000 endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and ultrasonography (EUS) procedures, Dr. Russell Ryono said at an annual meeting on infectious diseases.

The few clusters of cases uncovered by the 5-year retrospective analysis were separated not only in time, but by culture-negative patients treated with the same duodenoscopes at the same facilities, said Dr. Ryono of the public health surveillance and research office at the Department of Veterans Affairs in Palo Alto, Calif. “Our findings do not provide evidence of CRE transmission related to ERCP or EUS in Veterans Affairs,” Dr. Ryono and his associates concluded.

Contaminated duodenoscopes made headlines across the country this year after they caused outbreaks of fatal CRE infections in Los Angeles County. The Food and Drug Administration later acknowledged that the “complex design of the devices makes it difficult to remove contaminants compared to other types of endoscopes,” and both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and FDA recommended surveillance and reprocessing practices to help keep the scopes from transmitting serious infections.

In response to these concerns, the VA mined its data warehouses for ERCP and EUS procedures and CRE isolates recovered between January 2010 and the end of February 2015. Investigators looked for patients who were culture positive for the same type of CRE, underwent ERCP/EUS at the same facility within 6 months of each other, and were treated with the same scope or with an unidentified scope. Within this group, researchers honed in on “pairs” – or clusters – of patients in which the second patient exposed to the scope was CRE negative before the procedure and CRE positive afterward.

The initial query yielded more than 55,600 procedures among 40,329 veterans at 38 VA centers, as well as nearly 5,000 CRE isolates, more than half of which were cultured from urine samples, said Dr. Ryono. However, only 81 ERCP/EUS patients had CRE cultured from any anatomical site at any time. Among them, 57 patients were CRE negative before their procedure but CRE positive afterward, Dr. Ryono said.

There were 10 pairs of culture-positive patients treated at four facilities, one of which did not track serial numbers of duodenoscopes, according to Dr. Ryono. At that facility, procedure dates for pairs were 68-143 days apart, he said. Procedure dates for pairs at the other three facilities were spaced at least 82 days apart. Based on such extensive temporal spacing and the fact that the same scopes were used on culture-negative patients during intervening times, the investigators concluded that duodenoscopes were unlikely to have caused CRE infection or colonization.

Dr. Ryono noted several study limitations, however. Not only were CRE isolates unavailable for epidemiologic testing, but researchers also could not determine the extent to which facilities had implemented the 2010 guidelines for CLSI breakpoints. “Certainly, those facilities that have implemented those guidelines are more likely to catch CRE,” he said. Also, VA does not routinely screen patients for CRE before they undergo ERCP or EUS, “so it is very possible that some of our patients might have been colonized with CRE before the procedure, and we would not have been able to capture that,” he added. “Given the limitations of this review, the possibility that there was some transmission certainly cannot be completely excluded.”

Dr. Ryono reported these findings at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

The researchers declared no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Researchers found “no compelling evidence” that carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae were transmitted to Veterans Affairs patients during more than 55,000 endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and ultrasonography (EUS) procedures, Dr. Russell Ryono said at an annual meeting on infectious diseases.

The few clusters of cases uncovered by the 5-year retrospective analysis were separated not only in time, but by culture-negative patients treated with the same duodenoscopes at the same facilities, said Dr. Ryono of the public health surveillance and research office at the Department of Veterans Affairs in Palo Alto, Calif. “Our findings do not provide evidence of CRE transmission related to ERCP or EUS in Veterans Affairs,” Dr. Ryono and his associates concluded.

Contaminated duodenoscopes made headlines across the country this year after they caused outbreaks of fatal CRE infections in Los Angeles County. The Food and Drug Administration later acknowledged that the “complex design of the devices makes it difficult to remove contaminants compared to other types of endoscopes,” and both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and FDA recommended surveillance and reprocessing practices to help keep the scopes from transmitting serious infections.

In response to these concerns, the VA mined its data warehouses for ERCP and EUS procedures and CRE isolates recovered between January 2010 and the end of February 2015. Investigators looked for patients who were culture positive for the same type of CRE, underwent ERCP/EUS at the same facility within 6 months of each other, and were treated with the same scope or with an unidentified scope. Within this group, researchers honed in on “pairs” – or clusters – of patients in which the second patient exposed to the scope was CRE negative before the procedure and CRE positive afterward.

The initial query yielded more than 55,600 procedures among 40,329 veterans at 38 VA centers, as well as nearly 5,000 CRE isolates, more than half of which were cultured from urine samples, said Dr. Ryono. However, only 81 ERCP/EUS patients had CRE cultured from any anatomical site at any time. Among them, 57 patients were CRE negative before their procedure but CRE positive afterward, Dr. Ryono said.

There were 10 pairs of culture-positive patients treated at four facilities, one of which did not track serial numbers of duodenoscopes, according to Dr. Ryono. At that facility, procedure dates for pairs were 68-143 days apart, he said. Procedure dates for pairs at the other three facilities were spaced at least 82 days apart. Based on such extensive temporal spacing and the fact that the same scopes were used on culture-negative patients during intervening times, the investigators concluded that duodenoscopes were unlikely to have caused CRE infection or colonization.

Dr. Ryono noted several study limitations, however. Not only were CRE isolates unavailable for epidemiologic testing, but researchers also could not determine the extent to which facilities had implemented the 2010 guidelines for CLSI breakpoints. “Certainly, those facilities that have implemented those guidelines are more likely to catch CRE,” he said. Also, VA does not routinely screen patients for CRE before they undergo ERCP or EUS, “so it is very possible that some of our patients might have been colonized with CRE before the procedure, and we would not have been able to capture that,” he added. “Given the limitations of this review, the possibility that there was some transmission certainly cannot be completely excluded.”

Dr. Ryono reported these findings at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

The researchers declared no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

AT IDWEEK 2015

Key clinical point: In a large retrospective review, the Department of Veterans Affairs found no evidence of transmission of carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae through ERCP or EUS.

Major finding: The review found no compelling evidence of CRE transmission.

Data source: Retrospective study of 55,676 ERCP/EUS procedures in 40,329 veterans and 4,914 CRE isolates from 2,383 patients.

Disclosures:. The researchers reported no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

IDWeek: Testing delays linked to misclassification of hospital-onset C. difficile

SAN DIEGO – Delays in laboratory testing led a hospital to misclassify the origin of nearly a quarter of Clostridium difficile infections, Dr. Christopher Polage said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“Many patients with symptoms and risk factors are not being tested within 3 days of admission, leading to overreporting of hospital-onset [Clostridium difficile infections] and underreporting of community-onset CDI,” said Dr. Polage of the UC Davis (Calif.) Health System. By testing patients who have diarrhea and risk factors for CDI sooner after admission, hospitals can prevent outbreaks and improve their standardized infection ratio for CDI, he added.

Clostridium difficile is implicated in about 29,000 deaths every year in the United States. The vast majority of such cases are classified as hospital onset, based on the “3-day rule,” meaning that patients were tested more than 3 days after admission. “This is the preventable hospital outcome that we’re all trying to bring down,” Dr. Polage said.

As part of that effort, he and his colleagues studied 11 hospital units that were considered high risk for CDI. To identify toxigenic C. difficile, they performed culture and polymerase chain reaction testing on perianal swabs collected from all adult patients admitted to these units. They also analyzed toxin immunoassays of stool samples when physicians requested them for patients with diarrhea.

“The question was, how often was misclassification happening?” said Dr. Polage. Among 48 cases that the laboratory reported as hospital onset, based on the “3-day rule,” close to half (44%) actually had CD-positive perianal swabs when admitted, he said. And half of these swab-positive patients waited more than 3 days for a CD stool test even though they had current or recent diarrhea, he added. In fact, swab-positive patients with diarrhea went a median of 6 days without a CD stool test, and some went untested for 10 days, Dr. Polage said.

“Anyone who has tried to determine if a hospitalized patient is having diarrhea knows that this can be very hard to pin down,” Dr. Polage noted. But some patients with positive swabs on admission met three different definitions for diarrhea, “making it pretty clear that they had community-onset CDI,” he said. This most conservative approach found that 23% of “hospital-onset” cases were actually community onset, he said.

Thus far, UC Davis Health System seems not to have had an increase in antibiotic prescriptions in response to greater detection of community-onset CDI, Dr. Polage said. “This is not something we take lightly,” he added. “We put together a lot of educational materials for patients, physicians, and providers, and work with our antibiotic stewardship team. We found that we might be able to focus on patients who had CDI at time of admission, and intervene with them individually to more carefully monitor what antibiotic they were using.”

Dr. Polage reported these findings at IDWeek, the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation helped fund the study. Dr. Polage reported having received research materials or honoraria from Cepheid, TechLab, Alere, Meridian, and ACEA Biosciences.

SAN DIEGO – Delays in laboratory testing led a hospital to misclassify the origin of nearly a quarter of Clostridium difficile infections, Dr. Christopher Polage said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“Many patients with symptoms and risk factors are not being tested within 3 days of admission, leading to overreporting of hospital-onset [Clostridium difficile infections] and underreporting of community-onset CDI,” said Dr. Polage of the UC Davis (Calif.) Health System. By testing patients who have diarrhea and risk factors for CDI sooner after admission, hospitals can prevent outbreaks and improve their standardized infection ratio for CDI, he added.

Clostridium difficile is implicated in about 29,000 deaths every year in the United States. The vast majority of such cases are classified as hospital onset, based on the “3-day rule,” meaning that patients were tested more than 3 days after admission. “This is the preventable hospital outcome that we’re all trying to bring down,” Dr. Polage said.

As part of that effort, he and his colleagues studied 11 hospital units that were considered high risk for CDI. To identify toxigenic C. difficile, they performed culture and polymerase chain reaction testing on perianal swabs collected from all adult patients admitted to these units. They also analyzed toxin immunoassays of stool samples when physicians requested them for patients with diarrhea.

“The question was, how often was misclassification happening?” said Dr. Polage. Among 48 cases that the laboratory reported as hospital onset, based on the “3-day rule,” close to half (44%) actually had CD-positive perianal swabs when admitted, he said. And half of these swab-positive patients waited more than 3 days for a CD stool test even though they had current or recent diarrhea, he added. In fact, swab-positive patients with diarrhea went a median of 6 days without a CD stool test, and some went untested for 10 days, Dr. Polage said.

“Anyone who has tried to determine if a hospitalized patient is having diarrhea knows that this can be very hard to pin down,” Dr. Polage noted. But some patients with positive swabs on admission met three different definitions for diarrhea, “making it pretty clear that they had community-onset CDI,” he said. This most conservative approach found that 23% of “hospital-onset” cases were actually community onset, he said.

Thus far, UC Davis Health System seems not to have had an increase in antibiotic prescriptions in response to greater detection of community-onset CDI, Dr. Polage said. “This is not something we take lightly,” he added. “We put together a lot of educational materials for patients, physicians, and providers, and work with our antibiotic stewardship team. We found that we might be able to focus on patients who had CDI at time of admission, and intervene with them individually to more carefully monitor what antibiotic they were using.”

Dr. Polage reported these findings at IDWeek, the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation helped fund the study. Dr. Polage reported having received research materials or honoraria from Cepheid, TechLab, Alere, Meridian, and ACEA Biosciences.

SAN DIEGO – Delays in laboratory testing led a hospital to misclassify the origin of nearly a quarter of Clostridium difficile infections, Dr. Christopher Polage said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“Many patients with symptoms and risk factors are not being tested within 3 days of admission, leading to overreporting of hospital-onset [Clostridium difficile infections] and underreporting of community-onset CDI,” said Dr. Polage of the UC Davis (Calif.) Health System. By testing patients who have diarrhea and risk factors for CDI sooner after admission, hospitals can prevent outbreaks and improve their standardized infection ratio for CDI, he added.

Clostridium difficile is implicated in about 29,000 deaths every year in the United States. The vast majority of such cases are classified as hospital onset, based on the “3-day rule,” meaning that patients were tested more than 3 days after admission. “This is the preventable hospital outcome that we’re all trying to bring down,” Dr. Polage said.

As part of that effort, he and his colleagues studied 11 hospital units that were considered high risk for CDI. To identify toxigenic C. difficile, they performed culture and polymerase chain reaction testing on perianal swabs collected from all adult patients admitted to these units. They also analyzed toxin immunoassays of stool samples when physicians requested them for patients with diarrhea.

“The question was, how often was misclassification happening?” said Dr. Polage. Among 48 cases that the laboratory reported as hospital onset, based on the “3-day rule,” close to half (44%) actually had CD-positive perianal swabs when admitted, he said. And half of these swab-positive patients waited more than 3 days for a CD stool test even though they had current or recent diarrhea, he added. In fact, swab-positive patients with diarrhea went a median of 6 days without a CD stool test, and some went untested for 10 days, Dr. Polage said.

“Anyone who has tried to determine if a hospitalized patient is having diarrhea knows that this can be very hard to pin down,” Dr. Polage noted. But some patients with positive swabs on admission met three different definitions for diarrhea, “making it pretty clear that they had community-onset CDI,” he said. This most conservative approach found that 23% of “hospital-onset” cases were actually community onset, he said.

Thus far, UC Davis Health System seems not to have had an increase in antibiotic prescriptions in response to greater detection of community-onset CDI, Dr. Polage said. “This is not something we take lightly,” he added. “We put together a lot of educational materials for patients, physicians, and providers, and work with our antibiotic stewardship team. We found that we might be able to focus on patients who had CDI at time of admission, and intervene with them individually to more carefully monitor what antibiotic they were using.”

Dr. Polage reported these findings at IDWeek, the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation helped fund the study. Dr. Polage reported having received research materials or honoraria from Cepheid, TechLab, Alere, Meridian, and ACEA Biosciences.

AT IDWEEK 2015

Key clinical point: Delays in laboratory testing led to misclassification of Clostridium difficile infections.

Major finding: At least 23% of cases that were reported as hospital onset were actually community onset.

Data source: An analysis of 12 months of C. difficile infection surveillance data from one academic medical center.

Disclosures: The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation helped fund the study. Dr. Polage reported having received research materials or honoraria from Cepheid, TechLab, Alere, Meridian, and ACEA Biosciences.

Software picked up HAI clusters faster than hospitals

SAN DIEGO – An automated outbreak detection system was popular among infection preventionists and detected pathogenic clusters about 5 days sooner than did hospitals themselves, researchers said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“The vast majority of hospitals were very pleased to expand surveillance beyond multidrug-resistant organisms, and most thought this system would improve their ability to detect outbreaks and streamline their work,” said Dr. Meghan Baker of Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston.

Patients in acute-care hospitals acquired almost 782,000 healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) in 2011, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Traditionally, infection preventionists at these hospitals look for HAIs by identifying temporal or spatial clusters of “a limited number of prespecified pathogens,” Dr. Baker said. But some real clusters do not meet these empirical rules, leading to more cases and potentially severe consequences for patients. Automated HAI outbreak detection systems can help, but not if they constantly trigger false alarms or, conversely, are so specific that they miss outbreaks.

Using the Premier SafetySurveillor infection control tool and free statistical software, Dr. Baker and her associates analyzed 83 years of historical microbiology data from 44 hospitals. The system signaled for any cluster involving at least three cases, even if cases occurred by chance less than once a year, she said. The researchers compared the results with outbreak data submitted by a convenience sample of hospitals that used their usual surveillance methods.

The automated approach identified 230 clusters. Most were detected based on antimicrobial resistance, but others shared the same ward or specialty service and some produced more than one signal. Clusters most often involved Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus, Pseudomonas, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella, but most organisms were not under routine surveillance. As a result, 89% of clusters detected by the automated tool were not detected by hospitals using their usual methods, she emphasized. “Some were not real breaks, as determined later by genetic typing,” she added. “Most real clusters were [methicillin-resistant S. aureus], Clostridium difficile, and some were resistant gram-negative rods.”

When surveyed, 76% of infection preventionists said the automated tool moderately or greatly improved their ability to detect outbreaks, Dr. Baker reported. They would have wanted notification about 81% of the clusters, and considered 47% to be moderately or highly concerning. Notably, 51% of clusters expanded after detection.

“If these had been detected in real time, it would have been possible to intervene and possibly curtail the outbreak,” and 237 (42%) of 559 infections might have been avoided if these interventions were successful, she said.

Dr. Baker and her associates reported their findings at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

Dr. Baker reported no competing interests. Two of her associates reported financial and relationships with Premier, Sage, Molnycke, and 3M.

SAN DIEGO – An automated outbreak detection system was popular among infection preventionists and detected pathogenic clusters about 5 days sooner than did hospitals themselves, researchers said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“The vast majority of hospitals were very pleased to expand surveillance beyond multidrug-resistant organisms, and most thought this system would improve their ability to detect outbreaks and streamline their work,” said Dr. Meghan Baker of Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston.

Patients in acute-care hospitals acquired almost 782,000 healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) in 2011, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Traditionally, infection preventionists at these hospitals look for HAIs by identifying temporal or spatial clusters of “a limited number of prespecified pathogens,” Dr. Baker said. But some real clusters do not meet these empirical rules, leading to more cases and potentially severe consequences for patients. Automated HAI outbreak detection systems can help, but not if they constantly trigger false alarms or, conversely, are so specific that they miss outbreaks.

Using the Premier SafetySurveillor infection control tool and free statistical software, Dr. Baker and her associates analyzed 83 years of historical microbiology data from 44 hospitals. The system signaled for any cluster involving at least three cases, even if cases occurred by chance less than once a year, she said. The researchers compared the results with outbreak data submitted by a convenience sample of hospitals that used their usual surveillance methods.

The automated approach identified 230 clusters. Most were detected based on antimicrobial resistance, but others shared the same ward or specialty service and some produced more than one signal. Clusters most often involved Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus, Pseudomonas, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella, but most organisms were not under routine surveillance. As a result, 89% of clusters detected by the automated tool were not detected by hospitals using their usual methods, she emphasized. “Some were not real breaks, as determined later by genetic typing,” she added. “Most real clusters were [methicillin-resistant S. aureus], Clostridium difficile, and some were resistant gram-negative rods.”

When surveyed, 76% of infection preventionists said the automated tool moderately or greatly improved their ability to detect outbreaks, Dr. Baker reported. They would have wanted notification about 81% of the clusters, and considered 47% to be moderately or highly concerning. Notably, 51% of clusters expanded after detection.

“If these had been detected in real time, it would have been possible to intervene and possibly curtail the outbreak,” and 237 (42%) of 559 infections might have been avoided if these interventions were successful, she said.

Dr. Baker and her associates reported their findings at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

Dr. Baker reported no competing interests. Two of her associates reported financial and relationships with Premier, Sage, Molnycke, and 3M.

SAN DIEGO – An automated outbreak detection system was popular among infection preventionists and detected pathogenic clusters about 5 days sooner than did hospitals themselves, researchers said at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

“The vast majority of hospitals were very pleased to expand surveillance beyond multidrug-resistant organisms, and most thought this system would improve their ability to detect outbreaks and streamline their work,” said Dr. Meghan Baker of Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston.

Patients in acute-care hospitals acquired almost 782,000 healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) in 2011, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Traditionally, infection preventionists at these hospitals look for HAIs by identifying temporal or spatial clusters of “a limited number of prespecified pathogens,” Dr. Baker said. But some real clusters do not meet these empirical rules, leading to more cases and potentially severe consequences for patients. Automated HAI outbreak detection systems can help, but not if they constantly trigger false alarms or, conversely, are so specific that they miss outbreaks.

Using the Premier SafetySurveillor infection control tool and free statistical software, Dr. Baker and her associates analyzed 83 years of historical microbiology data from 44 hospitals. The system signaled for any cluster involving at least three cases, even if cases occurred by chance less than once a year, she said. The researchers compared the results with outbreak data submitted by a convenience sample of hospitals that used their usual surveillance methods.

The automated approach identified 230 clusters. Most were detected based on antimicrobial resistance, but others shared the same ward or specialty service and some produced more than one signal. Clusters most often involved Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus, Pseudomonas, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella, but most organisms were not under routine surveillance. As a result, 89% of clusters detected by the automated tool were not detected by hospitals using their usual methods, she emphasized. “Some were not real breaks, as determined later by genetic typing,” she added. “Most real clusters were [methicillin-resistant S. aureus], Clostridium difficile, and some were resistant gram-negative rods.”

When surveyed, 76% of infection preventionists said the automated tool moderately or greatly improved their ability to detect outbreaks, Dr. Baker reported. They would have wanted notification about 81% of the clusters, and considered 47% to be moderately or highly concerning. Notably, 51% of clusters expanded after detection.

“If these had been detected in real time, it would have been possible to intervene and possibly curtail the outbreak,” and 237 (42%) of 559 infections might have been avoided if these interventions were successful, she said.

Dr. Baker and her associates reported their findings at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

Dr. Baker reported no competing interests. Two of her associates reported financial and relationships with Premier, Sage, Molnycke, and 3M.

AT IDWEEK 2015

Key clinical point: An automated outbreak detection system can augment traditional methods for detecting pathogenic clusters.

Major finding: The software tool identified clusters about 5 days sooner than did hospitals themselves.

Data source: Comparison of an automated outbreak detection tool with usual hospital surveillance methods, and surveys of infection preventionists.

Disclosures: Dr. Baker reported no competing interests. Two of her associates reported financial and relationships with Premier, Sage, Molnycke, and 3M.

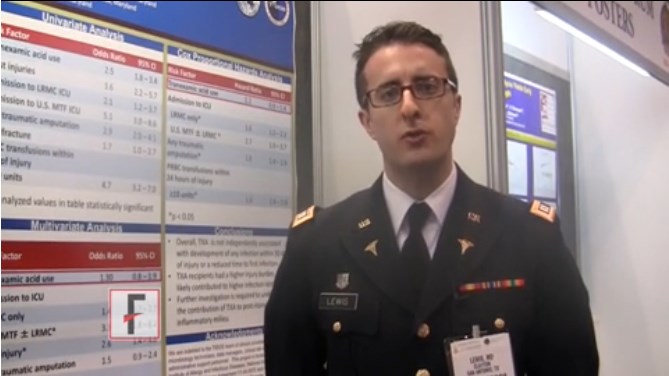

VIDEO: Tranexamic acid didn’t increase postop infections

CHICAGO – Tranexamic acid was not independently associated with any infection within 30 days of injury in U.S. soldiers undergoing trauma surgery, a case-control study showed.

The antifibrinolytic has been used for years to reduce morbidity and the risk of death associated with hemorrhage in the military setting. Tranexamic acid (TXA) made its way into the civilian setting after the 2010 provocative CRASH-2 trial in adult trauma patients.

Because TXA (Cyklokapron, Lysteda) also has anti-inflammatory properties, Dr. Clayton Lewis of Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio and his colleagues decided to evaluate the effect of TXA on the development of posttraumatic infections, including time to first infection, in combat casualties.

The findings were presented at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons, where we caught up with Dr. Lewis for an interview.

Dr. Lewis reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

CHICAGO – Tranexamic acid was not independently associated with any infection within 30 days of injury in U.S. soldiers undergoing trauma surgery, a case-control study showed.

The antifibrinolytic has been used for years to reduce morbidity and the risk of death associated with hemorrhage in the military setting. Tranexamic acid (TXA) made its way into the civilian setting after the 2010 provocative CRASH-2 trial in adult trauma patients.

Because TXA (Cyklokapron, Lysteda) also has anti-inflammatory properties, Dr. Clayton Lewis of Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio and his colleagues decided to evaluate the effect of TXA on the development of posttraumatic infections, including time to first infection, in combat casualties.

The findings were presented at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons, where we caught up with Dr. Lewis for an interview.

Dr. Lewis reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

CHICAGO – Tranexamic acid was not independently associated with any infection within 30 days of injury in U.S. soldiers undergoing trauma surgery, a case-control study showed.

The antifibrinolytic has been used for years to reduce morbidity and the risk of death associated with hemorrhage in the military setting. Tranexamic acid (TXA) made its way into the civilian setting after the 2010 provocative CRASH-2 trial in adult trauma patients.

Because TXA (Cyklokapron, Lysteda) also has anti-inflammatory properties, Dr. Clayton Lewis of Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio and his colleagues decided to evaluate the effect of TXA on the development of posttraumatic infections, including time to first infection, in combat casualties.

The findings were presented at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons, where we caught up with Dr. Lewis for an interview.

Dr. Lewis reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE ACS CLINICAL CONGRESS

Hospitals report inadequate duodenoscope reprocessing practices

SAN DIEGO – Less than a third of hospitals reprocessed duodenoscopes adequately to prevent potential transmission of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) and other pathogens, investigators reported at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

Moreover, only a third of facilities had conducted active surveillance for multidrug-resistant infections related to use of their duodenoscopes in the past year, reported Susan Beekmann of the Emerging Infections Network of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. “These findings suggest that endemic bacterial transmission associated with duodenoscopy may occur and may go unrecognized,” said Ms. Beekmann, program coordinator for EIN at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine in Iowa City.

Duodenoscopes, which are used in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), became a hot topic earlier this year after causing outbreaks of fatal CRE infections in Los Angeles County. The Food and Drug Administration has acknowledged that the “complex design of the devices makes it difficult to remove contaminants compared to other types of endoscopes,” and both the CDC and the FDA have recommended specific reprocessing and surveillance steps to reduce the chances that the scopes transmit serious infections.

To understand how hospitals were actually reprocessing and culturing the scopes at the time CDC released its guidance, Ms. Beekmann and her colleagues electronically surveyed 740 hospital epidemiologists through IDSA-EIN. They received responses from 378 physicians (52%), of which half said their facilities used duodenoscopes, Ms. Beekmann reported at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

Only 55 (29%) of these respondents said their facilities reprocessed duodenoscopes to an extent that the IDSA researchers defined as adequate – that is, manual reprocessing with high-level disinfection, either alone or in combination with other options, Ms. Beekmann said. Furthermore, only a third of facilities had cultured their duodenoscopes or done any other surveillance for bacterial transmission after duodenoscopy in the past year, even though most said they reviewed their reprocessing policies and procedures more often than once a year.

Respondents also described widely varying methodologies for sampling and culturing, Ms. Beekmann said. “Although we did not ask about them, ten respondents mentioned ATP bioluminescence assays,” she added. Based on the findings, better reprocessing technologies and consistent, real-time strategies to monitor the effectiveness of scope reprocessing are “urgent patient safety needs,” she and her colleagues concluded.

Ms. Beekmann and her associates reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Less than a third of hospitals reprocessed duodenoscopes adequately to prevent potential transmission of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) and other pathogens, investigators reported at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

Moreover, only a third of facilities had conducted active surveillance for multidrug-resistant infections related to use of their duodenoscopes in the past year, reported Susan Beekmann of the Emerging Infections Network of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. “These findings suggest that endemic bacterial transmission associated with duodenoscopy may occur and may go unrecognized,” said Ms. Beekmann, program coordinator for EIN at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine in Iowa City.

Duodenoscopes, which are used in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), became a hot topic earlier this year after causing outbreaks of fatal CRE infections in Los Angeles County. The Food and Drug Administration has acknowledged that the “complex design of the devices makes it difficult to remove contaminants compared to other types of endoscopes,” and both the CDC and the FDA have recommended specific reprocessing and surveillance steps to reduce the chances that the scopes transmit serious infections.

To understand how hospitals were actually reprocessing and culturing the scopes at the time CDC released its guidance, Ms. Beekmann and her colleagues electronically surveyed 740 hospital epidemiologists through IDSA-EIN. They received responses from 378 physicians (52%), of which half said their facilities used duodenoscopes, Ms. Beekmann reported at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

Only 55 (29%) of these respondents said their facilities reprocessed duodenoscopes to an extent that the IDSA researchers defined as adequate – that is, manual reprocessing with high-level disinfection, either alone or in combination with other options, Ms. Beekmann said. Furthermore, only a third of facilities had cultured their duodenoscopes or done any other surveillance for bacterial transmission after duodenoscopy in the past year, even though most said they reviewed their reprocessing policies and procedures more often than once a year.

Respondents also described widely varying methodologies for sampling and culturing, Ms. Beekmann said. “Although we did not ask about them, ten respondents mentioned ATP bioluminescence assays,” she added. Based on the findings, better reprocessing technologies and consistent, real-time strategies to monitor the effectiveness of scope reprocessing are “urgent patient safety needs,” she and her colleagues concluded.

Ms. Beekmann and her associates reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Less than a third of hospitals reprocessed duodenoscopes adequately to prevent potential transmission of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) and other pathogens, investigators reported at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

Moreover, only a third of facilities had conducted active surveillance for multidrug-resistant infections related to use of their duodenoscopes in the past year, reported Susan Beekmann of the Emerging Infections Network of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. “These findings suggest that endemic bacterial transmission associated with duodenoscopy may occur and may go unrecognized,” said Ms. Beekmann, program coordinator for EIN at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine in Iowa City.

Duodenoscopes, which are used in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), became a hot topic earlier this year after causing outbreaks of fatal CRE infections in Los Angeles County. The Food and Drug Administration has acknowledged that the “complex design of the devices makes it difficult to remove contaminants compared to other types of endoscopes,” and both the CDC and the FDA have recommended specific reprocessing and surveillance steps to reduce the chances that the scopes transmit serious infections.

To understand how hospitals were actually reprocessing and culturing the scopes at the time CDC released its guidance, Ms. Beekmann and her colleagues electronically surveyed 740 hospital epidemiologists through IDSA-EIN. They received responses from 378 physicians (52%), of which half said their facilities used duodenoscopes, Ms. Beekmann reported at the combined annual meetings of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, the HIV Medicine Association, and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

Only 55 (29%) of these respondents said their facilities reprocessed duodenoscopes to an extent that the IDSA researchers defined as adequate – that is, manual reprocessing with high-level disinfection, either alone or in combination with other options, Ms. Beekmann said. Furthermore, only a third of facilities had cultured their duodenoscopes or done any other surveillance for bacterial transmission after duodenoscopy in the past year, even though most said they reviewed their reprocessing policies and procedures more often than once a year.

Respondents also described widely varying methodologies for sampling and culturing, Ms. Beekmann said. “Although we did not ask about them, ten respondents mentioned ATP bioluminescence assays,” she added. Based on the findings, better reprocessing technologies and consistent, real-time strategies to monitor the effectiveness of scope reprocessing are “urgent patient safety needs,” she and her colleagues concluded.

Ms. Beekmann and her associates reported no relevant financial disclosures.

AT IDWEEK 2015

Key clinical point: Most hospitals did not reprocess duodenoscopes in a way that the Infectious Diseases Society of America considers adequate.

Major finding: Only 29% of facilities followed the minimum adequate practices.

Data source: A cross-sectional electronic survey of 378 physician members of the Emerging Infections Network of the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Disclosures: Susan Beekmann reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Results mixed in hospital efforts to tackle antimicrobial resistance

SAN DIEGO – Canadian hospitals are making progress in reducing the rates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, but the rates of antimicrobial resistance in Canadian hospitals increased significantly for extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, as well as vancomycin-resistant enterococci.

Those are among the key findings from a large national analysis known as CANWARD that were presented at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. “What it’s telling us is that some of the things that we’re doing on the antimicrobial resistance side are working,” lead study author George G. Zhanel, Pharm.D., professor of microbiology and infectious diseases at the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, said in an interview. “But it also tells us that some of these pathogens like [vancomycin-resistant enterococci] and [extended-spectrum beta-lactamase]–producing E. coli continue to go up. So there is some good news and some bad news, but it tells us that it’s not all just doom and gloom. Some progress has been made, but there’s still a long way to go.”

Conducted annually, CANWARD is a national health surveillance study that assesses pathogens causing infections in Canadian hospitals and their patterns of antimicrobial resistance. For the current analysis, Dr. Zhanel and his associates collected 36,607 isolates from patients in tertiary care hospitals in Canada from January 2007 to December 2014. They used Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute broth microdilution methods to perform antimicrobial susceptibility testing on more than 45 marketed and investigational agents.

Slightly more than half of the patients (55%) were male, and 87% were over age 18. The most common pathogens were E. coli (19.7%), methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA; 16.4%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (8.7%), S. pneumoniae (6.5%), K. pneumoniae (6.1%), methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA; 4.7%), Enterococcus species (4.0%), and Hemophilus influenzae (4.0%). Susceptibility rates for E. coli were 99.9% for meropenem and tigecycline, 99.7% for ertapenem, 97.7% for piperacillin/tazobactam, 92.5% for ceftriaxone, 90.4% for gentamicin, 77.2% for ciprofloxacin, and 73.0% for trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole. Susceptibility rates for P. aeruginosa were 94.2% for colistin, 84.3% for piperacillin/tazobactam, 83.3% for ceftazidime, 81.2% for meropenem, 77.6% for gentamicin, and 74.1% for ciprofloxacin. Susceptibility rates for MRSA were 100% for linezolid and telavancin, 99.9% for daptomycin, 99.4% for tigecycline, 99.1% for vancomycin, and 93.3% for trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole. The rates of resistant organisms between 2007 and 2014 increased significantly for extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing E. coli (from 3.4% to 11.6%) and K. pneumoniae (from 1.5% to 6.5%), as well as vancomycin-resistant enterococci (from 1.8% to 7.0%), while rates of MRSA significantly declined (from 26.1% to 20.2%).

“The biggest surprise to me is that the hospital-acquired genotype of MRSA is going down,” Dr. Zhanel commented. “The community-acquired genotype is still going up, but the hospital-acquired [genotype] has plummeted in hospitals.”

He noted that CANWARD data suggest that antimicrobial resistance “is not confined to one part of the hospital. We have resistance happening in medical wards, ICUs, and hospital emergency rooms. We consistently find that resistance is highest in the ICU and by far the lowest in the ER. With clinics we find that it’s a variable scenario.”

The study was supported in part by Abbott, Achaogen, Affinium, Astellas, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Cerexa/Forest, Cubist, Galderma Laboratories, Merck, Paladin Labs, Pfizer/Wyeth, Sunovion, and the Medicines Co. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Canadian hospitals are making progress in reducing the rates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, but the rates of antimicrobial resistance in Canadian hospitals increased significantly for extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, as well as vancomycin-resistant enterococci.

Those are among the key findings from a large national analysis known as CANWARD that were presented at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. “What it’s telling us is that some of the things that we’re doing on the antimicrobial resistance side are working,” lead study author George G. Zhanel, Pharm.D., professor of microbiology and infectious diseases at the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, said in an interview. “But it also tells us that some of these pathogens like [vancomycin-resistant enterococci] and [extended-spectrum beta-lactamase]–producing E. coli continue to go up. So there is some good news and some bad news, but it tells us that it’s not all just doom and gloom. Some progress has been made, but there’s still a long way to go.”

Conducted annually, CANWARD is a national health surveillance study that assesses pathogens causing infections in Canadian hospitals and their patterns of antimicrobial resistance. For the current analysis, Dr. Zhanel and his associates collected 36,607 isolates from patients in tertiary care hospitals in Canada from January 2007 to December 2014. They used Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute broth microdilution methods to perform antimicrobial susceptibility testing on more than 45 marketed and investigational agents.

Slightly more than half of the patients (55%) were male, and 87% were over age 18. The most common pathogens were E. coli (19.7%), methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA; 16.4%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (8.7%), S. pneumoniae (6.5%), K. pneumoniae (6.1%), methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA; 4.7%), Enterococcus species (4.0%), and Hemophilus influenzae (4.0%). Susceptibility rates for E. coli were 99.9% for meropenem and tigecycline, 99.7% for ertapenem, 97.7% for piperacillin/tazobactam, 92.5% for ceftriaxone, 90.4% for gentamicin, 77.2% for ciprofloxacin, and 73.0% for trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole. Susceptibility rates for P. aeruginosa were 94.2% for colistin, 84.3% for piperacillin/tazobactam, 83.3% for ceftazidime, 81.2% for meropenem, 77.6% for gentamicin, and 74.1% for ciprofloxacin. Susceptibility rates for MRSA were 100% for linezolid and telavancin, 99.9% for daptomycin, 99.4% for tigecycline, 99.1% for vancomycin, and 93.3% for trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole. The rates of resistant organisms between 2007 and 2014 increased significantly for extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing E. coli (from 3.4% to 11.6%) and K. pneumoniae (from 1.5% to 6.5%), as well as vancomycin-resistant enterococci (from 1.8% to 7.0%), while rates of MRSA significantly declined (from 26.1% to 20.2%).

“The biggest surprise to me is that the hospital-acquired genotype of MRSA is going down,” Dr. Zhanel commented. “The community-acquired genotype is still going up, but the hospital-acquired [genotype] has plummeted in hospitals.”

He noted that CANWARD data suggest that antimicrobial resistance “is not confined to one part of the hospital. We have resistance happening in medical wards, ICUs, and hospital emergency rooms. We consistently find that resistance is highest in the ICU and by far the lowest in the ER. With clinics we find that it’s a variable scenario.”

The study was supported in part by Abbott, Achaogen, Affinium, Astellas, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Cerexa/Forest, Cubist, Galderma Laboratories, Merck, Paladin Labs, Pfizer/Wyeth, Sunovion, and the Medicines Co. The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Canadian hospitals are making progress in reducing the rates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, but the rates of antimicrobial resistance in Canadian hospitals increased significantly for extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, as well as vancomycin-resistant enterococci.

Those are among the key findings from a large national analysis known as CANWARD that were presented at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. “What it’s telling us is that some of the things that we’re doing on the antimicrobial resistance side are working,” lead study author George G. Zhanel, Pharm.D., professor of microbiology and infectious diseases at the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, said in an interview. “But it also tells us that some of these pathogens like [vancomycin-resistant enterococci] and [extended-spectrum beta-lactamase]–producing E. coli continue to go up. So there is some good news and some bad news, but it tells us that it’s not all just doom and gloom. Some progress has been made, but there’s still a long way to go.”

Conducted annually, CANWARD is a national health surveillance study that assesses pathogens causing infections in Canadian hospitals and their patterns of antimicrobial resistance. For the current analysis, Dr. Zhanel and his associates collected 36,607 isolates from patients in tertiary care hospitals in Canada from January 2007 to December 2014. They used Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute broth microdilution methods to perform antimicrobial susceptibility testing on more than 45 marketed and investigational agents.

Slightly more than half of the patients (55%) were male, and 87% were over age 18. The most common pathogens were E. coli (19.7%), methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA; 16.4%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (8.7%), S. pneumoniae (6.5%), K. pneumoniae (6.1%), methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA; 4.7%), Enterococcus species (4.0%), and Hemophilus influenzae (4.0%). Susceptibility rates for E. coli were 99.9% for meropenem and tigecycline, 99.7% for ertapenem, 97.7% for piperacillin/tazobactam, 92.5% for ceftriaxone, 90.4% for gentamicin, 77.2% for ciprofloxacin, and 73.0% for trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole. Susceptibility rates for P. aeruginosa were 94.2% for colistin, 84.3% for piperacillin/tazobactam, 83.3% for ceftazidime, 81.2% for meropenem, 77.6% for gentamicin, and 74.1% for ciprofloxacin. Susceptibility rates for MRSA were 100% for linezolid and telavancin, 99.9% for daptomycin, 99.4% for tigecycline, 99.1% for vancomycin, and 93.3% for trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole. The rates of resistant organisms between 2007 and 2014 increased significantly for extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing E. coli (from 3.4% to 11.6%) and K. pneumoniae (from 1.5% to 6.5%), as well as vancomycin-resistant enterococci (from 1.8% to 7.0%), while rates of MRSA significantly declined (from 26.1% to 20.2%).

“The biggest surprise to me is that the hospital-acquired genotype of MRSA is going down,” Dr. Zhanel commented. “The community-acquired genotype is still going up, but the hospital-acquired [genotype] has plummeted in hospitals.”