User login

Harnessing the HIV care continuum model to improve HCV treatment success

Better linkage to care with providers who are familiar with both the HCV and HIV treatment cascade may not only improve access to HCV treatment, but it may also support patient retention, treatment adherence, and achievement of sustained virologic response (SVR) and viral suppression, said Stephanie LaMoy, CAN Community Health, North Point, Florida. She presented the results of a pilot study at the virtual Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 2020 Annual Meeting.

In an effort to identify strategies most important for improving care access among their patients with HCV, LaMoy and her colleagues assessed 12-month patient data collected from three of their clinics. These data were evaluated for HCV treatment access, engagement, and outcomes.

The pilot study included 126 patients who were reactive and another 24 HCV-positive patients who were referred from other sources. Active HCV infections requiring treatment were reported in 144 patients.

A total of 59 patients were linked to care but did not initiate treatment for their active infection. LaMoy said there were multiple causes, including homelessness, substance abuse, and inability to maintain contact.

In contrast, 85 patients with HCV infection started treatment, but 35 of these patients did not complete their regimen. Out of the 50 patients who reported completing treatment, 30 did not return to the clinic to confirm sustained viral suppression.

According to LaMoy, this raised a red flag, causing the investigators to consider a different approach to care.

HIV care continuum model and its role in HCV

To improve the rate at which patients with HCV infection complete treatment within their clinics, the researchers formed a panel to determine necessary interventions that could reduce barriers to care.

The HIV care continuum came into play. They chose this model based on knowledge that HCV and HIV share the same care continuum with similar goals in diagnosis, linkage to care, retention, and suppression.

Based on the consensus of the panel and consideration of the HIV care continuum model, they identified a number of interventions needed to mitigate HCV treatment barriers. These included the incorporation of peer navigators or linkage-to-care (LCC) coordinators, use of the mobile medical unit, greater implementation of onsite lab visits, and medication-assisted treatment.

The LCC coordinators proved to be particularly important, as these team members helped assist patients with social and financial support to address challenges with access to treatment. These coordinators can also help patients gain access to specialized providers, ultimately improving the chance of successful HCV management.

Additionally, LCC coordinators may help identify and reduce barriers associated with housing, transportation, and nutrition. Frequent patient contact by the LCC coordinators can encourage adherence and promote risk reduction education, such as providing referrals to needle exchange services.

“Linking individuals to care with providers who are familiar with the treatment cascade could help improve retention and should be a top priority for those involved in HCV screening and treatment,” said LaMoy. “An environment with knowledge, lack of judgment, and a tenacious need to heal the community that welcomes those with barriers to care is exactly what is needed for the patients in our program.”

National, community challenges fuel barriers to HCV treatment access

Substance use, trauma histories, and mental health problems can negatively affect care engagement and must be addressed before the benefits of HCV therapy can be realized.

Addressing these issues isn’t always easy, said Kathleen Bernock, FNP-BC, AACRN, AAHIVS, of the Bedford-Stuyvesant Family Health Center in New York City, in an email to Medscape Medical News. She pointed out that several states have harsh restrictions on who is able to access HCV treatment, and some states will not approve certain medications for people who actively use drugs.

“Even for states without these restrictions, many health systems are difficult to navigate and may not be welcoming to persons actively using,” said Bernock. Trauma-informed care can also be difficult to translate into clinics, she added.

“Decentralizing care to the communities most affected would greatly help mitigate these barriers,” suggested Bernock. Decentralization, she explained, might include co-locating services such as syringe exchanges, utilizing community health workers and patient navigators, and expanding capacity-to-treat to community-based providers.

“[And] with the expansion of telehealth services in the US,” said Bernock, “we now have even more avenues to reach people that we never had before.”

LaMoy and Bernock have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Better linkage to care with providers who are familiar with both the HCV and HIV treatment cascade may not only improve access to HCV treatment, but it may also support patient retention, treatment adherence, and achievement of sustained virologic response (SVR) and viral suppression, said Stephanie LaMoy, CAN Community Health, North Point, Florida. She presented the results of a pilot study at the virtual Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 2020 Annual Meeting.

In an effort to identify strategies most important for improving care access among their patients with HCV, LaMoy and her colleagues assessed 12-month patient data collected from three of their clinics. These data were evaluated for HCV treatment access, engagement, and outcomes.

The pilot study included 126 patients who were reactive and another 24 HCV-positive patients who were referred from other sources. Active HCV infections requiring treatment were reported in 144 patients.

A total of 59 patients were linked to care but did not initiate treatment for their active infection. LaMoy said there were multiple causes, including homelessness, substance abuse, and inability to maintain contact.

In contrast, 85 patients with HCV infection started treatment, but 35 of these patients did not complete their regimen. Out of the 50 patients who reported completing treatment, 30 did not return to the clinic to confirm sustained viral suppression.

According to LaMoy, this raised a red flag, causing the investigators to consider a different approach to care.

HIV care continuum model and its role in HCV

To improve the rate at which patients with HCV infection complete treatment within their clinics, the researchers formed a panel to determine necessary interventions that could reduce barriers to care.

The HIV care continuum came into play. They chose this model based on knowledge that HCV and HIV share the same care continuum with similar goals in diagnosis, linkage to care, retention, and suppression.

Based on the consensus of the panel and consideration of the HIV care continuum model, they identified a number of interventions needed to mitigate HCV treatment barriers. These included the incorporation of peer navigators or linkage-to-care (LCC) coordinators, use of the mobile medical unit, greater implementation of onsite lab visits, and medication-assisted treatment.

The LCC coordinators proved to be particularly important, as these team members helped assist patients with social and financial support to address challenges with access to treatment. These coordinators can also help patients gain access to specialized providers, ultimately improving the chance of successful HCV management.

Additionally, LCC coordinators may help identify and reduce barriers associated with housing, transportation, and nutrition. Frequent patient contact by the LCC coordinators can encourage adherence and promote risk reduction education, such as providing referrals to needle exchange services.

“Linking individuals to care with providers who are familiar with the treatment cascade could help improve retention and should be a top priority for those involved in HCV screening and treatment,” said LaMoy. “An environment with knowledge, lack of judgment, and a tenacious need to heal the community that welcomes those with barriers to care is exactly what is needed for the patients in our program.”

National, community challenges fuel barriers to HCV treatment access

Substance use, trauma histories, and mental health problems can negatively affect care engagement and must be addressed before the benefits of HCV therapy can be realized.

Addressing these issues isn’t always easy, said Kathleen Bernock, FNP-BC, AACRN, AAHIVS, of the Bedford-Stuyvesant Family Health Center in New York City, in an email to Medscape Medical News. She pointed out that several states have harsh restrictions on who is able to access HCV treatment, and some states will not approve certain medications for people who actively use drugs.

“Even for states without these restrictions, many health systems are difficult to navigate and may not be welcoming to persons actively using,” said Bernock. Trauma-informed care can also be difficult to translate into clinics, she added.

“Decentralizing care to the communities most affected would greatly help mitigate these barriers,” suggested Bernock. Decentralization, she explained, might include co-locating services such as syringe exchanges, utilizing community health workers and patient navigators, and expanding capacity-to-treat to community-based providers.

“[And] with the expansion of telehealth services in the US,” said Bernock, “we now have even more avenues to reach people that we never had before.”

LaMoy and Bernock have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Better linkage to care with providers who are familiar with both the HCV and HIV treatment cascade may not only improve access to HCV treatment, but it may also support patient retention, treatment adherence, and achievement of sustained virologic response (SVR) and viral suppression, said Stephanie LaMoy, CAN Community Health, North Point, Florida. She presented the results of a pilot study at the virtual Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 2020 Annual Meeting.

In an effort to identify strategies most important for improving care access among their patients with HCV, LaMoy and her colleagues assessed 12-month patient data collected from three of their clinics. These data were evaluated for HCV treatment access, engagement, and outcomes.

The pilot study included 126 patients who were reactive and another 24 HCV-positive patients who were referred from other sources. Active HCV infections requiring treatment were reported in 144 patients.

A total of 59 patients were linked to care but did not initiate treatment for their active infection. LaMoy said there were multiple causes, including homelessness, substance abuse, and inability to maintain contact.

In contrast, 85 patients with HCV infection started treatment, but 35 of these patients did not complete their regimen. Out of the 50 patients who reported completing treatment, 30 did not return to the clinic to confirm sustained viral suppression.

According to LaMoy, this raised a red flag, causing the investigators to consider a different approach to care.

HIV care continuum model and its role in HCV

To improve the rate at which patients with HCV infection complete treatment within their clinics, the researchers formed a panel to determine necessary interventions that could reduce barriers to care.

The HIV care continuum came into play. They chose this model based on knowledge that HCV and HIV share the same care continuum with similar goals in diagnosis, linkage to care, retention, and suppression.

Based on the consensus of the panel and consideration of the HIV care continuum model, they identified a number of interventions needed to mitigate HCV treatment barriers. These included the incorporation of peer navigators or linkage-to-care (LCC) coordinators, use of the mobile medical unit, greater implementation of onsite lab visits, and medication-assisted treatment.

The LCC coordinators proved to be particularly important, as these team members helped assist patients with social and financial support to address challenges with access to treatment. These coordinators can also help patients gain access to specialized providers, ultimately improving the chance of successful HCV management.

Additionally, LCC coordinators may help identify and reduce barriers associated with housing, transportation, and nutrition. Frequent patient contact by the LCC coordinators can encourage adherence and promote risk reduction education, such as providing referrals to needle exchange services.

“Linking individuals to care with providers who are familiar with the treatment cascade could help improve retention and should be a top priority for those involved in HCV screening and treatment,” said LaMoy. “An environment with knowledge, lack of judgment, and a tenacious need to heal the community that welcomes those with barriers to care is exactly what is needed for the patients in our program.”

National, community challenges fuel barriers to HCV treatment access

Substance use, trauma histories, and mental health problems can negatively affect care engagement and must be addressed before the benefits of HCV therapy can be realized.

Addressing these issues isn’t always easy, said Kathleen Bernock, FNP-BC, AACRN, AAHIVS, of the Bedford-Stuyvesant Family Health Center in New York City, in an email to Medscape Medical News. She pointed out that several states have harsh restrictions on who is able to access HCV treatment, and some states will not approve certain medications for people who actively use drugs.

“Even for states without these restrictions, many health systems are difficult to navigate and may not be welcoming to persons actively using,” said Bernock. Trauma-informed care can also be difficult to translate into clinics, she added.

“Decentralizing care to the communities most affected would greatly help mitigate these barriers,” suggested Bernock. Decentralization, she explained, might include co-locating services such as syringe exchanges, utilizing community health workers and patient navigators, and expanding capacity-to-treat to community-based providers.

“[And] with the expansion of telehealth services in the US,” said Bernock, “we now have even more avenues to reach people that we never had before.”

LaMoy and Bernock have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

GLIMMER of hope for itch in primary biliary cholangitis

Patients with primary biliary cholangitis experienced rapid improvements in itch and quality of life after treatment with linerixibat in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of the small-molecule drug.

Moderate to severe pruritus “affects patients’ quality of life and is a huge burden for them,” said investigator Cynthia Levy, MD, from the University of Miami Health System.

“Finally having a medication that controls those symptoms is really important,” she said in an interview.

With a twice-daily mid-range dose of the drug for 12 weeks, patients with moderate to severe itch reported significantly less itch and better social and emotional quality of life, Dr. Levy reported at the Liver Meeting, where she presented findings from the phase 2 GLIMMER trial.

After a single-blind 4-week placebo run-in period for patients with itch scores of at least 4 on a 10-point rating scale, those with itch scores of at least 3 were then randomly assigned to one of five treatment regimens – once-daily linerixibat at doses of 20 mg, 90 mg, or 180 mg, or twice-daily doses of 40 mg or 90 mg – or to placebo.

After 12 weeks of treatment, all 147 participants once again received placebo for 4 weeks.

During the trial, participants recorded itch levels twice daily. The worst of these daily scores was averaged every 7 days to determine the mean worst daily itch.

The primary study endpoint was the change in worst daily itch from baseline after 12 weeks of treatment. Participants whose self-rated itch improved by 2 points on the 10-point scale were considered to have had a response to the drug.

Participants also completed the PBC-40, an instrument to measure quality of life in patients with primary biliary cholangitis, answering questions about itch and social and emotional status.

Reductions in worst daily itch from baseline to 12 weeks were steepest in the 40-mg twice-daily group, at 2.86 points, and in the 90-mg twice-daily group, at 2.25 points. In the placebo group, the mean decrease was 1.73 points.

During the subsequent 4 weeks of placebo, after treatment ended, the itch relief faded in all groups.

Scores on the PBC-40 itch domain improved significantly in every group, including placebo. However, only those in the twice-daily 40-mg group saw significant improvements on the social (P = .0016) and emotional (P = .0025) domains.

‘Between incremental and revolutionary’

The results are on a “kind of continuum between incremental and revolutionary,” said Jonathan A. Dranoff, MD, from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, who was not involved in the study. “It doesn’t hit either extreme, but it’s the first new drug for this purpose in forever, which by itself is a good thing.”

The placebo effect suggests that “maybe the actual contribution of the noncognitive brain to pruritus is bigger than we thought, and that’s worth noting,” he added. Nevertheless, “the drug still appears to have effects that are statistically different from placebo.”

The placebo effect in itching studies is always high but tends to wane over time, said Dr. Levy. This trial had a 4-week placebo run-in period to allow that effect to fade somewhat, she explained.

About 10% of the study cohort experienced drug-related diarrhea, which was expected, and about 10% dropped out of the trial because of drug-related adverse events.

Linerixibat is an ileal sodium-dependent bile acid transporter inhibitor, so the gut has to deal with the excess bile acid fallout, but the diarrhea is likely manageable with antidiarrheals, said Dr. Levy.

It is unlikely that diarrhea will deter patients with severe itch from using an effective drug when other drugs have failed them. “These patients are consumed by itch most of the time,” said Dr. Dranoff. “I think for people who don’t regularly treat patients with primary biliary cholangitis, it’s one of the underappreciated aspects of the disease.”

The improvements in social and emotional quality of life seen with linerixibat are not only statistically significant, they are also clinically significant, said Dr. Levy. “We are really expecting this to impact the lives of our patients and are looking forward to phase 3.”

Dr. Levy disclosed support from GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Dranoff disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with primary biliary cholangitis experienced rapid improvements in itch and quality of life after treatment with linerixibat in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of the small-molecule drug.

Moderate to severe pruritus “affects patients’ quality of life and is a huge burden for them,” said investigator Cynthia Levy, MD, from the University of Miami Health System.

“Finally having a medication that controls those symptoms is really important,” she said in an interview.

With a twice-daily mid-range dose of the drug for 12 weeks, patients with moderate to severe itch reported significantly less itch and better social and emotional quality of life, Dr. Levy reported at the Liver Meeting, where she presented findings from the phase 2 GLIMMER trial.

After a single-blind 4-week placebo run-in period for patients with itch scores of at least 4 on a 10-point rating scale, those with itch scores of at least 3 were then randomly assigned to one of five treatment regimens – once-daily linerixibat at doses of 20 mg, 90 mg, or 180 mg, or twice-daily doses of 40 mg or 90 mg – or to placebo.

After 12 weeks of treatment, all 147 participants once again received placebo for 4 weeks.

During the trial, participants recorded itch levels twice daily. The worst of these daily scores was averaged every 7 days to determine the mean worst daily itch.

The primary study endpoint was the change in worst daily itch from baseline after 12 weeks of treatment. Participants whose self-rated itch improved by 2 points on the 10-point scale were considered to have had a response to the drug.

Participants also completed the PBC-40, an instrument to measure quality of life in patients with primary biliary cholangitis, answering questions about itch and social and emotional status.

Reductions in worst daily itch from baseline to 12 weeks were steepest in the 40-mg twice-daily group, at 2.86 points, and in the 90-mg twice-daily group, at 2.25 points. In the placebo group, the mean decrease was 1.73 points.

During the subsequent 4 weeks of placebo, after treatment ended, the itch relief faded in all groups.

Scores on the PBC-40 itch domain improved significantly in every group, including placebo. However, only those in the twice-daily 40-mg group saw significant improvements on the social (P = .0016) and emotional (P = .0025) domains.

‘Between incremental and revolutionary’

The results are on a “kind of continuum between incremental and revolutionary,” said Jonathan A. Dranoff, MD, from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, who was not involved in the study. “It doesn’t hit either extreme, but it’s the first new drug for this purpose in forever, which by itself is a good thing.”

The placebo effect suggests that “maybe the actual contribution of the noncognitive brain to pruritus is bigger than we thought, and that’s worth noting,” he added. Nevertheless, “the drug still appears to have effects that are statistically different from placebo.”

The placebo effect in itching studies is always high but tends to wane over time, said Dr. Levy. This trial had a 4-week placebo run-in period to allow that effect to fade somewhat, she explained.

About 10% of the study cohort experienced drug-related diarrhea, which was expected, and about 10% dropped out of the trial because of drug-related adverse events.

Linerixibat is an ileal sodium-dependent bile acid transporter inhibitor, so the gut has to deal with the excess bile acid fallout, but the diarrhea is likely manageable with antidiarrheals, said Dr. Levy.

It is unlikely that diarrhea will deter patients with severe itch from using an effective drug when other drugs have failed them. “These patients are consumed by itch most of the time,” said Dr. Dranoff. “I think for people who don’t regularly treat patients with primary biliary cholangitis, it’s one of the underappreciated aspects of the disease.”

The improvements in social and emotional quality of life seen with linerixibat are not only statistically significant, they are also clinically significant, said Dr. Levy. “We are really expecting this to impact the lives of our patients and are looking forward to phase 3.”

Dr. Levy disclosed support from GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Dranoff disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with primary biliary cholangitis experienced rapid improvements in itch and quality of life after treatment with linerixibat in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of the small-molecule drug.

Moderate to severe pruritus “affects patients’ quality of life and is a huge burden for them,” said investigator Cynthia Levy, MD, from the University of Miami Health System.

“Finally having a medication that controls those symptoms is really important,” she said in an interview.

With a twice-daily mid-range dose of the drug for 12 weeks, patients with moderate to severe itch reported significantly less itch and better social and emotional quality of life, Dr. Levy reported at the Liver Meeting, where she presented findings from the phase 2 GLIMMER trial.

After a single-blind 4-week placebo run-in period for patients with itch scores of at least 4 on a 10-point rating scale, those with itch scores of at least 3 were then randomly assigned to one of five treatment regimens – once-daily linerixibat at doses of 20 mg, 90 mg, or 180 mg, or twice-daily doses of 40 mg or 90 mg – or to placebo.

After 12 weeks of treatment, all 147 participants once again received placebo for 4 weeks.

During the trial, participants recorded itch levels twice daily. The worst of these daily scores was averaged every 7 days to determine the mean worst daily itch.

The primary study endpoint was the change in worst daily itch from baseline after 12 weeks of treatment. Participants whose self-rated itch improved by 2 points on the 10-point scale were considered to have had a response to the drug.

Participants also completed the PBC-40, an instrument to measure quality of life in patients with primary biliary cholangitis, answering questions about itch and social and emotional status.

Reductions in worst daily itch from baseline to 12 weeks were steepest in the 40-mg twice-daily group, at 2.86 points, and in the 90-mg twice-daily group, at 2.25 points. In the placebo group, the mean decrease was 1.73 points.

During the subsequent 4 weeks of placebo, after treatment ended, the itch relief faded in all groups.

Scores on the PBC-40 itch domain improved significantly in every group, including placebo. However, only those in the twice-daily 40-mg group saw significant improvements on the social (P = .0016) and emotional (P = .0025) domains.

‘Between incremental and revolutionary’

The results are on a “kind of continuum between incremental and revolutionary,” said Jonathan A. Dranoff, MD, from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, who was not involved in the study. “It doesn’t hit either extreme, but it’s the first new drug for this purpose in forever, which by itself is a good thing.”

The placebo effect suggests that “maybe the actual contribution of the noncognitive brain to pruritus is bigger than we thought, and that’s worth noting,” he added. Nevertheless, “the drug still appears to have effects that are statistically different from placebo.”

The placebo effect in itching studies is always high but tends to wane over time, said Dr. Levy. This trial had a 4-week placebo run-in period to allow that effect to fade somewhat, she explained.

About 10% of the study cohort experienced drug-related diarrhea, which was expected, and about 10% dropped out of the trial because of drug-related adverse events.

Linerixibat is an ileal sodium-dependent bile acid transporter inhibitor, so the gut has to deal with the excess bile acid fallout, but the diarrhea is likely manageable with antidiarrheals, said Dr. Levy.

It is unlikely that diarrhea will deter patients with severe itch from using an effective drug when other drugs have failed them. “These patients are consumed by itch most of the time,” said Dr. Dranoff. “I think for people who don’t regularly treat patients with primary biliary cholangitis, it’s one of the underappreciated aspects of the disease.”

The improvements in social and emotional quality of life seen with linerixibat are not only statistically significant, they are also clinically significant, said Dr. Levy. “We are really expecting this to impact the lives of our patients and are looking forward to phase 3.”

Dr. Levy disclosed support from GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Dranoff disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mixed outcomes in tenofovir trial for chronic hepatitis B

About one-third of patients with chronic hepatitis B maintained a profile consistent with inactive disease 1 year after withdrawal from treatment in the randomized HBRN trial, which compared tenofovir with and without pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN). The two treatment groups, however, had similarly low rates of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) loss, the trial’s primary end point.

The successful withdrawals could inform discussions with patients who are “very motivated to have a finite treatment course,” said investigator Norah Terrault, MD, from the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. The results might “help patients in talking about expectations,” she said, because “there’s a one in three chance they won’t go back on treatment” if they meet specific metrics.

In HBRN, the metrics for withdrawal from treatment after 192 weeks included low levels of viral DNA (<1,000 IU/mL) for at least 24 weeks, no cirrhosis, negative week 144 test results for the hepatitis B envelope antigen (HBeAg), and week 180 conversion to anti-HBe positivity.

Of 102 patients who received tenofovir monotherapy for 192 weeks and who completed the trial, 51 met these criteria. After withdrawal from treatment, 30% still had DNA levels below 1,000 IU/mL and normal ALT at week 240, which is consistent with inactive chronic hepatitis B.

Of the 99 participants in the combination group – who received PEG-IFN for the first 24 of 192 weeks in addition to tenofovir – 60 met the withdrawal criteria at 192 weeks. At week 240, 39% of this withdrawal group still had DNA and ALT values consistent with inactive disease.

Rates of HBsAg loss, which signals functional cure, were low in the two groups, however. At week 240, fewer patients in the tenofovir monotherapy group tested negative for HBsAg than in the tenofovir plus PEG-IFN combination group, but the difference was not significant (4.5% vs. 5.7%).

The timing of HBsAg loss differed between the groups. In the combination group, the loss largely occurred before treatment withdrawal, likely because of the antiviral effects of interferon, Dr. Terrault said in an interview. In the monotherapy group, the loss occurred after 192 weeks, possibly reflecting the immunologic consequences of treatment withdrawal.

The timing of ALT flares also differed between groups. In the combination group, 58% of flares occurred during the 24-week PEG-IFN period. In the monotherapy group, 70% of flares occurred after tenofovir was stopped at 192 weeks.

The flare picture is a tricky one, said Dr. Terrault. The episodes might be a positive factor in HBsAg loss, but severe flares carry a risk for decompensation. Good predictors of the severity of flares are lacking, and “that is the hurdle” to finding a balance with these trade-offs.

‘Partially a failure and partially a success’

The findings are “partially a failure and partially a success,” said Robert Gish, MD, from Loma Linda (Calif.) University of Health, who was not involved in the study.

The low rates of HBsAg loss and the similarity between the two treatment groups represent the failure, he explained. The success is for the patients who were HBeAg-positive when the study began because they had high HBeAg loss rates in both the monotherapy and combination groups (41% vs. 61%; P = .06).

Loss of HBeAg was numerically higher in the combination group because of the interferon effect. That could be viewed as a “subjective benefit” of PEG-IFN, even though the difference wasn’t statistically significant, said Dr. Gish.

The low rates of HBsAg loss could relate to two features of the patient profile, he explained. At study entry, the participants had moderately high levels of quantitative HBsAg and were predominately of Asian ancestry, which are predisposing factors for limited HBsAg loss.

Previous studies have suggested that peak HBsAg loss could take 2-3 years to develop after treatment withdrawal in a trial population. In the HBRN trial, rates almost 1 year after withdrawal are similar to 1-year rates from other studies, Dr. Terrault said. How these results for HBsAg loss in the two treatment groups will look at the 3-year mark is not known.

The trial design standardized withdrawal protocol and the length of time patients were on treatment before withdrawal was attempted, which are strengths of this study, said Dr. Terrault. And “a triumph of this study is execution of a standard for nucleic acid treatment in a protocolized way, followed by withdrawal. That is something we are happy about.”

Dr. Terrault reported receiving institutional grant support from Roche/Genentech and Gilead Sciences. Dr. Gish reported receiving research support from Gilead Sciences and serving as a consultant and on advisory boards for several pharmaceutical companies.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

About one-third of patients with chronic hepatitis B maintained a profile consistent with inactive disease 1 year after withdrawal from treatment in the randomized HBRN trial, which compared tenofovir with and without pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN). The two treatment groups, however, had similarly low rates of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) loss, the trial’s primary end point.

The successful withdrawals could inform discussions with patients who are “very motivated to have a finite treatment course,” said investigator Norah Terrault, MD, from the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. The results might “help patients in talking about expectations,” she said, because “there’s a one in three chance they won’t go back on treatment” if they meet specific metrics.

In HBRN, the metrics for withdrawal from treatment after 192 weeks included low levels of viral DNA (<1,000 IU/mL) for at least 24 weeks, no cirrhosis, negative week 144 test results for the hepatitis B envelope antigen (HBeAg), and week 180 conversion to anti-HBe positivity.

Of 102 patients who received tenofovir monotherapy for 192 weeks and who completed the trial, 51 met these criteria. After withdrawal from treatment, 30% still had DNA levels below 1,000 IU/mL and normal ALT at week 240, which is consistent with inactive chronic hepatitis B.

Of the 99 participants in the combination group – who received PEG-IFN for the first 24 of 192 weeks in addition to tenofovir – 60 met the withdrawal criteria at 192 weeks. At week 240, 39% of this withdrawal group still had DNA and ALT values consistent with inactive disease.

Rates of HBsAg loss, which signals functional cure, were low in the two groups, however. At week 240, fewer patients in the tenofovir monotherapy group tested negative for HBsAg than in the tenofovir plus PEG-IFN combination group, but the difference was not significant (4.5% vs. 5.7%).

The timing of HBsAg loss differed between the groups. In the combination group, the loss largely occurred before treatment withdrawal, likely because of the antiviral effects of interferon, Dr. Terrault said in an interview. In the monotherapy group, the loss occurred after 192 weeks, possibly reflecting the immunologic consequences of treatment withdrawal.

The timing of ALT flares also differed between groups. In the combination group, 58% of flares occurred during the 24-week PEG-IFN period. In the monotherapy group, 70% of flares occurred after tenofovir was stopped at 192 weeks.

The flare picture is a tricky one, said Dr. Terrault. The episodes might be a positive factor in HBsAg loss, but severe flares carry a risk for decompensation. Good predictors of the severity of flares are lacking, and “that is the hurdle” to finding a balance with these trade-offs.

‘Partially a failure and partially a success’

The findings are “partially a failure and partially a success,” said Robert Gish, MD, from Loma Linda (Calif.) University of Health, who was not involved in the study.

The low rates of HBsAg loss and the similarity between the two treatment groups represent the failure, he explained. The success is for the patients who were HBeAg-positive when the study began because they had high HBeAg loss rates in both the monotherapy and combination groups (41% vs. 61%; P = .06).

Loss of HBeAg was numerically higher in the combination group because of the interferon effect. That could be viewed as a “subjective benefit” of PEG-IFN, even though the difference wasn’t statistically significant, said Dr. Gish.

The low rates of HBsAg loss could relate to two features of the patient profile, he explained. At study entry, the participants had moderately high levels of quantitative HBsAg and were predominately of Asian ancestry, which are predisposing factors for limited HBsAg loss.

Previous studies have suggested that peak HBsAg loss could take 2-3 years to develop after treatment withdrawal in a trial population. In the HBRN trial, rates almost 1 year after withdrawal are similar to 1-year rates from other studies, Dr. Terrault said. How these results for HBsAg loss in the two treatment groups will look at the 3-year mark is not known.

The trial design standardized withdrawal protocol and the length of time patients were on treatment before withdrawal was attempted, which are strengths of this study, said Dr. Terrault. And “a triumph of this study is execution of a standard for nucleic acid treatment in a protocolized way, followed by withdrawal. That is something we are happy about.”

Dr. Terrault reported receiving institutional grant support from Roche/Genentech and Gilead Sciences. Dr. Gish reported receiving research support from Gilead Sciences and serving as a consultant and on advisory boards for several pharmaceutical companies.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

About one-third of patients with chronic hepatitis B maintained a profile consistent with inactive disease 1 year after withdrawal from treatment in the randomized HBRN trial, which compared tenofovir with and without pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN). The two treatment groups, however, had similarly low rates of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) loss, the trial’s primary end point.

The successful withdrawals could inform discussions with patients who are “very motivated to have a finite treatment course,” said investigator Norah Terrault, MD, from the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. The results might “help patients in talking about expectations,” she said, because “there’s a one in three chance they won’t go back on treatment” if they meet specific metrics.

In HBRN, the metrics for withdrawal from treatment after 192 weeks included low levels of viral DNA (<1,000 IU/mL) for at least 24 weeks, no cirrhosis, negative week 144 test results for the hepatitis B envelope antigen (HBeAg), and week 180 conversion to anti-HBe positivity.

Of 102 patients who received tenofovir monotherapy for 192 weeks and who completed the trial, 51 met these criteria. After withdrawal from treatment, 30% still had DNA levels below 1,000 IU/mL and normal ALT at week 240, which is consistent with inactive chronic hepatitis B.

Of the 99 participants in the combination group – who received PEG-IFN for the first 24 of 192 weeks in addition to tenofovir – 60 met the withdrawal criteria at 192 weeks. At week 240, 39% of this withdrawal group still had DNA and ALT values consistent with inactive disease.

Rates of HBsAg loss, which signals functional cure, were low in the two groups, however. At week 240, fewer patients in the tenofovir monotherapy group tested negative for HBsAg than in the tenofovir plus PEG-IFN combination group, but the difference was not significant (4.5% vs. 5.7%).

The timing of HBsAg loss differed between the groups. In the combination group, the loss largely occurred before treatment withdrawal, likely because of the antiviral effects of interferon, Dr. Terrault said in an interview. In the monotherapy group, the loss occurred after 192 weeks, possibly reflecting the immunologic consequences of treatment withdrawal.

The timing of ALT flares also differed between groups. In the combination group, 58% of flares occurred during the 24-week PEG-IFN period. In the monotherapy group, 70% of flares occurred after tenofovir was stopped at 192 weeks.

The flare picture is a tricky one, said Dr. Terrault. The episodes might be a positive factor in HBsAg loss, but severe flares carry a risk for decompensation. Good predictors of the severity of flares are lacking, and “that is the hurdle” to finding a balance with these trade-offs.

‘Partially a failure and partially a success’

The findings are “partially a failure and partially a success,” said Robert Gish, MD, from Loma Linda (Calif.) University of Health, who was not involved in the study.

The low rates of HBsAg loss and the similarity between the two treatment groups represent the failure, he explained. The success is for the patients who were HBeAg-positive when the study began because they had high HBeAg loss rates in both the monotherapy and combination groups (41% vs. 61%; P = .06).

Loss of HBeAg was numerically higher in the combination group because of the interferon effect. That could be viewed as a “subjective benefit” of PEG-IFN, even though the difference wasn’t statistically significant, said Dr. Gish.

The low rates of HBsAg loss could relate to two features of the patient profile, he explained. At study entry, the participants had moderately high levels of quantitative HBsAg and were predominately of Asian ancestry, which are predisposing factors for limited HBsAg loss.

Previous studies have suggested that peak HBsAg loss could take 2-3 years to develop after treatment withdrawal in a trial population. In the HBRN trial, rates almost 1 year after withdrawal are similar to 1-year rates from other studies, Dr. Terrault said. How these results for HBsAg loss in the two treatment groups will look at the 3-year mark is not known.

The trial design standardized withdrawal protocol and the length of time patients were on treatment before withdrawal was attempted, which are strengths of this study, said Dr. Terrault. And “a triumph of this study is execution of a standard for nucleic acid treatment in a protocolized way, followed by withdrawal. That is something we are happy about.”

Dr. Terrault reported receiving institutional grant support from Roche/Genentech and Gilead Sciences. Dr. Gish reported receiving research support from Gilead Sciences and serving as a consultant and on advisory boards for several pharmaceutical companies.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Liver-related deaths decline after Medicaid expansion under ACA

Liver-related deaths declined and liver transplant waitlist inequities decreased in states that implemented Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), results of an innovative study showed.

About 1 year after Medicaid expansion began on Jan. 1, 2014, the rate of liver-related mortality in 18 states that took advantage of expanded coverage began to decline, whereas the rate of liver-related deaths in 14 states that did not expand Medicaid continued to climb, reported Nabeel Wahid, MD, a resident at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

The differences in liver-related mortality between Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states was particularly pronounced in people of Asian background, in Whites, and in African Americans, he said in an oral abstract presentation during the virtual annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

“The expansion of government health care programs such as Medicaid may improve liver-related mortality and liver transplant waitlist placement,” he said.

The implementation of the ACA, also known as Obamacare, resulted in “a pretty dramatic increase in the number of Americans with health insurance today, and there’s a lot of literature out there looking at a variety of domains throughout health care that have found that Medicaid expansion increased access and decreased disparities in care,” he added.

For example, a report published in 2019 by the nonpartisan National Bureau of Economic Research Priorities showed a significant reduction in disease-related deaths in Americans aged 55-64 in Medicaid expansion states compared with nonexpansion states.

In addition as previously reported, before Medicaid expansion African Americans were 4.8% less likely than were Whites to receive timely cancer treatment, defined as treatment starting within 30 days of diagnosis of an advanced or metastatic solid tumor. After Medicaid expansion, however, the difference between the racial groups had dwindled to just 0.8% and was no longer statistically significant.

“However, specifically in the realm of liver transplantation and liver disease, there’s very limited literature showing any sort of significant impact on care resulting from Medicaid expansion,” Dr. Wahid said.

Listing-to-death ratio

To test their hypothesis that Medicaid expansion decreased racial disparities and improved liver-related deaths and transplant waitlist placement, Dr. Wahid and colleagues compared liver-related deaths and liver transplants listings between Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states in the 5 years before expansion (2009-2013) and in the 5 years after expansion (2014-2018). They excluded all states without transplant centers as well as patients younger than 25 or older than 64, who were likely to be covered by other types of insurance.

They obtained data for listing from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) and on end-stage liver disease from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s WONDER database.

They also used a novel measure called the listing-to-death ratio (LDR), a surrogate endpoint for waitlist placement calculated as the ratio of listings for liver transplantation relative to the number of deaths from liver disease, with a higher LDR score corresponding to improved waitlist placement.

They found that throughout the entire study period, Medicaid expansion states had lower liver-related deaths, higher liver transplant listings, and higher LDR.

Using joinpoint regression to examine changes at a specific time point, the investigators determined that the annual percentage change in liver-related deaths increased in both nonexpansion states (mean 4.3%) and expansion states (3.0%) before 2014. However, beginning around 2015, liver-related deaths began to decline in expansion states by a mean of –0.6%, while they continued on an upward trajectory in the nonexpansion states, albeit at a somewhat slower pace (mean APC 2% from 2014 through 2018).

Among all racial and ethnic groups (Whites, African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians) liver-related deaths increased from 2014 to 2018 in nonexpansion states, with the highest annual percentage change in Asians, at slightly more than 8%.

In contrast, among Asians in the expansion states, liver-related deaths over the same period increased by less than 1%, and in both Whites and African Americans liver-related deaths declined.

In addition, starting in 2015, the annual percent change in LDR increased only in expansion states primarily because of fewer end-stage liver disease deaths (the denominator in the LDR equation) rather than increased listings (the numerator).

‘No-brainer’

A gastroenterologist who was not involved in the study said that there are two key points in favor of the study.

“The obvious message is that transplant is costly, and patients need to be insured to get a liver transplant, because nobody is paying for this out of pocket. So if more candidates are insured that will reduce disparities and improve access to liver transplant for those who need it,” said Elliot Benjamin Tapper, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

“It’s a no-brainer that the lack of insurance accessibility for the most vulnerable people in the United States meant that they were dying of cirrhosis instead of being transplanted,” he said in an interview.

He also commended the authors on their use of population-based data to identify outcomes.

“We know how many people are listed for liver transplant, but we don’t know how many people could have been listed. We know how many people are transplanted, but we don’t know how many people with decompensated cirrhosis should have been given that chance. We lacked that denominator,” he said.

“The innovation that makes this particular paper worthwhile is that in the absence of that denominator, they were able to construct it, so we can know from other data sources distinct from the waitlist rolls how many people are dying of cirrhosis,” he added.

No study funding source was reported. Dr. Wahid and Dr. Tapper reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Wahid N et al. AASLD 2020. Abstract 153.

Liver-related deaths declined and liver transplant waitlist inequities decreased in states that implemented Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), results of an innovative study showed.

About 1 year after Medicaid expansion began on Jan. 1, 2014, the rate of liver-related mortality in 18 states that took advantage of expanded coverage began to decline, whereas the rate of liver-related deaths in 14 states that did not expand Medicaid continued to climb, reported Nabeel Wahid, MD, a resident at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

The differences in liver-related mortality between Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states was particularly pronounced in people of Asian background, in Whites, and in African Americans, he said in an oral abstract presentation during the virtual annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

“The expansion of government health care programs such as Medicaid may improve liver-related mortality and liver transplant waitlist placement,” he said.

The implementation of the ACA, also known as Obamacare, resulted in “a pretty dramatic increase in the number of Americans with health insurance today, and there’s a lot of literature out there looking at a variety of domains throughout health care that have found that Medicaid expansion increased access and decreased disparities in care,” he added.

For example, a report published in 2019 by the nonpartisan National Bureau of Economic Research Priorities showed a significant reduction in disease-related deaths in Americans aged 55-64 in Medicaid expansion states compared with nonexpansion states.

In addition as previously reported, before Medicaid expansion African Americans were 4.8% less likely than were Whites to receive timely cancer treatment, defined as treatment starting within 30 days of diagnosis of an advanced or metastatic solid tumor. After Medicaid expansion, however, the difference between the racial groups had dwindled to just 0.8% and was no longer statistically significant.

“However, specifically in the realm of liver transplantation and liver disease, there’s very limited literature showing any sort of significant impact on care resulting from Medicaid expansion,” Dr. Wahid said.

Listing-to-death ratio

To test their hypothesis that Medicaid expansion decreased racial disparities and improved liver-related deaths and transplant waitlist placement, Dr. Wahid and colleagues compared liver-related deaths and liver transplants listings between Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states in the 5 years before expansion (2009-2013) and in the 5 years after expansion (2014-2018). They excluded all states without transplant centers as well as patients younger than 25 or older than 64, who were likely to be covered by other types of insurance.

They obtained data for listing from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) and on end-stage liver disease from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s WONDER database.

They also used a novel measure called the listing-to-death ratio (LDR), a surrogate endpoint for waitlist placement calculated as the ratio of listings for liver transplantation relative to the number of deaths from liver disease, with a higher LDR score corresponding to improved waitlist placement.

They found that throughout the entire study period, Medicaid expansion states had lower liver-related deaths, higher liver transplant listings, and higher LDR.

Using joinpoint regression to examine changes at a specific time point, the investigators determined that the annual percentage change in liver-related deaths increased in both nonexpansion states (mean 4.3%) and expansion states (3.0%) before 2014. However, beginning around 2015, liver-related deaths began to decline in expansion states by a mean of –0.6%, while they continued on an upward trajectory in the nonexpansion states, albeit at a somewhat slower pace (mean APC 2% from 2014 through 2018).

Among all racial and ethnic groups (Whites, African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians) liver-related deaths increased from 2014 to 2018 in nonexpansion states, with the highest annual percentage change in Asians, at slightly more than 8%.

In contrast, among Asians in the expansion states, liver-related deaths over the same period increased by less than 1%, and in both Whites and African Americans liver-related deaths declined.

In addition, starting in 2015, the annual percent change in LDR increased only in expansion states primarily because of fewer end-stage liver disease deaths (the denominator in the LDR equation) rather than increased listings (the numerator).

‘No-brainer’

A gastroenterologist who was not involved in the study said that there are two key points in favor of the study.

“The obvious message is that transplant is costly, and patients need to be insured to get a liver transplant, because nobody is paying for this out of pocket. So if more candidates are insured that will reduce disparities and improve access to liver transplant for those who need it,” said Elliot Benjamin Tapper, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

“It’s a no-brainer that the lack of insurance accessibility for the most vulnerable people in the United States meant that they were dying of cirrhosis instead of being transplanted,” he said in an interview.

He also commended the authors on their use of population-based data to identify outcomes.

“We know how many people are listed for liver transplant, but we don’t know how many people could have been listed. We know how many people are transplanted, but we don’t know how many people with decompensated cirrhosis should have been given that chance. We lacked that denominator,” he said.

“The innovation that makes this particular paper worthwhile is that in the absence of that denominator, they were able to construct it, so we can know from other data sources distinct from the waitlist rolls how many people are dying of cirrhosis,” he added.

No study funding source was reported. Dr. Wahid and Dr. Tapper reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Wahid N et al. AASLD 2020. Abstract 153.

Liver-related deaths declined and liver transplant waitlist inequities decreased in states that implemented Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), results of an innovative study showed.

About 1 year after Medicaid expansion began on Jan. 1, 2014, the rate of liver-related mortality in 18 states that took advantage of expanded coverage began to decline, whereas the rate of liver-related deaths in 14 states that did not expand Medicaid continued to climb, reported Nabeel Wahid, MD, a resident at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

The differences in liver-related mortality between Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states was particularly pronounced in people of Asian background, in Whites, and in African Americans, he said in an oral abstract presentation during the virtual annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

“The expansion of government health care programs such as Medicaid may improve liver-related mortality and liver transplant waitlist placement,” he said.

The implementation of the ACA, also known as Obamacare, resulted in “a pretty dramatic increase in the number of Americans with health insurance today, and there’s a lot of literature out there looking at a variety of domains throughout health care that have found that Medicaid expansion increased access and decreased disparities in care,” he added.

For example, a report published in 2019 by the nonpartisan National Bureau of Economic Research Priorities showed a significant reduction in disease-related deaths in Americans aged 55-64 in Medicaid expansion states compared with nonexpansion states.

In addition as previously reported, before Medicaid expansion African Americans were 4.8% less likely than were Whites to receive timely cancer treatment, defined as treatment starting within 30 days of diagnosis of an advanced or metastatic solid tumor. After Medicaid expansion, however, the difference between the racial groups had dwindled to just 0.8% and was no longer statistically significant.

“However, specifically in the realm of liver transplantation and liver disease, there’s very limited literature showing any sort of significant impact on care resulting from Medicaid expansion,” Dr. Wahid said.

Listing-to-death ratio

To test their hypothesis that Medicaid expansion decreased racial disparities and improved liver-related deaths and transplant waitlist placement, Dr. Wahid and colleagues compared liver-related deaths and liver transplants listings between Medicaid expansion and nonexpansion states in the 5 years before expansion (2009-2013) and in the 5 years after expansion (2014-2018). They excluded all states without transplant centers as well as patients younger than 25 or older than 64, who were likely to be covered by other types of insurance.

They obtained data for listing from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) and on end-stage liver disease from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s WONDER database.

They also used a novel measure called the listing-to-death ratio (LDR), a surrogate endpoint for waitlist placement calculated as the ratio of listings for liver transplantation relative to the number of deaths from liver disease, with a higher LDR score corresponding to improved waitlist placement.

They found that throughout the entire study period, Medicaid expansion states had lower liver-related deaths, higher liver transplant listings, and higher LDR.

Using joinpoint regression to examine changes at a specific time point, the investigators determined that the annual percentage change in liver-related deaths increased in both nonexpansion states (mean 4.3%) and expansion states (3.0%) before 2014. However, beginning around 2015, liver-related deaths began to decline in expansion states by a mean of –0.6%, while they continued on an upward trajectory in the nonexpansion states, albeit at a somewhat slower pace (mean APC 2% from 2014 through 2018).

Among all racial and ethnic groups (Whites, African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians) liver-related deaths increased from 2014 to 2018 in nonexpansion states, with the highest annual percentage change in Asians, at slightly more than 8%.

In contrast, among Asians in the expansion states, liver-related deaths over the same period increased by less than 1%, and in both Whites and African Americans liver-related deaths declined.

In addition, starting in 2015, the annual percent change in LDR increased only in expansion states primarily because of fewer end-stage liver disease deaths (the denominator in the LDR equation) rather than increased listings (the numerator).

‘No-brainer’

A gastroenterologist who was not involved in the study said that there are two key points in favor of the study.

“The obvious message is that transplant is costly, and patients need to be insured to get a liver transplant, because nobody is paying for this out of pocket. So if more candidates are insured that will reduce disparities and improve access to liver transplant for those who need it,” said Elliot Benjamin Tapper, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

“It’s a no-brainer that the lack of insurance accessibility for the most vulnerable people in the United States meant that they were dying of cirrhosis instead of being transplanted,” he said in an interview.

He also commended the authors on their use of population-based data to identify outcomes.

“We know how many people are listed for liver transplant, but we don’t know how many people could have been listed. We know how many people are transplanted, but we don’t know how many people with decompensated cirrhosis should have been given that chance. We lacked that denominator,” he said.

“The innovation that makes this particular paper worthwhile is that in the absence of that denominator, they were able to construct it, so we can know from other data sources distinct from the waitlist rolls how many people are dying of cirrhosis,” he added.

No study funding source was reported. Dr. Wahid and Dr. Tapper reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Wahid N et al. AASLD 2020. Abstract 153.

FROM THE LIVER MEETING DIGITAL EXPERIENCE

Liver injury linked to COVID-19–related coagulopathy

There is a link between liver injury and a tendency toward excessive clotting in patients with COVID-19, and the organ’s own blood vessels could be responsible, new research shows.

Cells that line the liver’s blood vessels produce high levels of factor VIII, a coagulation factor, when they are exposed to interleukin-6, an inflammatory molecule associated with COVID-19.

These findings “center the liver in global coagulopathy of COVID-19 and define a mechanism for increased coagulation factor levels that may be treatment targets,” said investigator Matthew McConnell, MD, from the Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The effect of IL-6 on the liver sinusoidal endothelial cells lining the liver blood vessels creates a prothrombotic environment that includes the release of factor VIII, said Dr. McConnell, who presented the results at the virtual annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

These associations offer insights into why COVID-19 patients with underlying liver disease can experience “devastating complications” related to improper blood vessel function in the organ, he added.

For their study, Dr. McConnell and colleagues analyzed data on ALT and hypercoagulability from 68 adults treated at the Yale–New Haven Hospital. The liver and coagulation tests were administered within 5 days of each other.

The team set the ALT cutoff for liver injury at three times the upper limit of normal. Patients with two or more parameters indicating excessive clotting were considered to have a hypercoagulable profile, which Dr. McConnell called “a signature clinical finding of COVID-19 infection.”

Patients with high levels of ALT also experienced elevations in clotting-related factors, such as fibrinogen levels and the activity of factor VIII and factor II. Furthermore, liver injury was significantly associated with hypercoagulability (P < .05).

Because COVID-19 is linked to the proinflammatory IL-6, the investigators examined how this cytokine and its receptor affect human liver sinusoidal cells. Cells exposed to IL-6 and its receptor pumped out factor VIII at levels that were significantly higher than in unexposed cells (P < .01). Exposed cells also produced significantly more von Willebrand factor (P < .05), another prothrombotic molecule, and showed increased expression of genes that induce the expression of factor VIII.

“As we learn more about COVID-19, we find that it is as much a coagulatory as a respiratory disease,” said Tien Dong, MD, PhD, from the University of California, Los Angeles, who was not involved in the study.

These findings are in line with a lot of other COVID-19-related research that suggests a link between hepatocyte injury and clotting disorders, he added.

One important factor is existing liver disease, said Dr. Dong. “If you have COVID-19 on top of that, you’re probably at risk of developing acute liver injury from the infection itself.”

That said, it’s still a good idea to check liver function in patients with COVID-19 and no known liver disease, he advised. Staying on top of these measures will keep the odds of long-term problems “a lot lower.”

There is utility in the findings beyond COVID-19, said Dr. McConnell. They provide “insights into complications of critical illness, in general, in the liver blood vessels” of patients with underlying liver disease.

Dr. McConnell and Dr. Dong have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

There is a link between liver injury and a tendency toward excessive clotting in patients with COVID-19, and the organ’s own blood vessels could be responsible, new research shows.

Cells that line the liver’s blood vessels produce high levels of factor VIII, a coagulation factor, when they are exposed to interleukin-6, an inflammatory molecule associated with COVID-19.

These findings “center the liver in global coagulopathy of COVID-19 and define a mechanism for increased coagulation factor levels that may be treatment targets,” said investigator Matthew McConnell, MD, from the Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The effect of IL-6 on the liver sinusoidal endothelial cells lining the liver blood vessels creates a prothrombotic environment that includes the release of factor VIII, said Dr. McConnell, who presented the results at the virtual annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

These associations offer insights into why COVID-19 patients with underlying liver disease can experience “devastating complications” related to improper blood vessel function in the organ, he added.

For their study, Dr. McConnell and colleagues analyzed data on ALT and hypercoagulability from 68 adults treated at the Yale–New Haven Hospital. The liver and coagulation tests were administered within 5 days of each other.

The team set the ALT cutoff for liver injury at three times the upper limit of normal. Patients with two or more parameters indicating excessive clotting were considered to have a hypercoagulable profile, which Dr. McConnell called “a signature clinical finding of COVID-19 infection.”

Patients with high levels of ALT also experienced elevations in clotting-related factors, such as fibrinogen levels and the activity of factor VIII and factor II. Furthermore, liver injury was significantly associated with hypercoagulability (P < .05).

Because COVID-19 is linked to the proinflammatory IL-6, the investigators examined how this cytokine and its receptor affect human liver sinusoidal cells. Cells exposed to IL-6 and its receptor pumped out factor VIII at levels that were significantly higher than in unexposed cells (P < .01). Exposed cells also produced significantly more von Willebrand factor (P < .05), another prothrombotic molecule, and showed increased expression of genes that induce the expression of factor VIII.

“As we learn more about COVID-19, we find that it is as much a coagulatory as a respiratory disease,” said Tien Dong, MD, PhD, from the University of California, Los Angeles, who was not involved in the study.

These findings are in line with a lot of other COVID-19-related research that suggests a link between hepatocyte injury and clotting disorders, he added.

One important factor is existing liver disease, said Dr. Dong. “If you have COVID-19 on top of that, you’re probably at risk of developing acute liver injury from the infection itself.”

That said, it’s still a good idea to check liver function in patients with COVID-19 and no known liver disease, he advised. Staying on top of these measures will keep the odds of long-term problems “a lot lower.”

There is utility in the findings beyond COVID-19, said Dr. McConnell. They provide “insights into complications of critical illness, in general, in the liver blood vessels” of patients with underlying liver disease.

Dr. McConnell and Dr. Dong have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

There is a link between liver injury and a tendency toward excessive clotting in patients with COVID-19, and the organ’s own blood vessels could be responsible, new research shows.

Cells that line the liver’s blood vessels produce high levels of factor VIII, a coagulation factor, when they are exposed to interleukin-6, an inflammatory molecule associated with COVID-19.

These findings “center the liver in global coagulopathy of COVID-19 and define a mechanism for increased coagulation factor levels that may be treatment targets,” said investigator Matthew McConnell, MD, from the Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The effect of IL-6 on the liver sinusoidal endothelial cells lining the liver blood vessels creates a prothrombotic environment that includes the release of factor VIII, said Dr. McConnell, who presented the results at the virtual annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

These associations offer insights into why COVID-19 patients with underlying liver disease can experience “devastating complications” related to improper blood vessel function in the organ, he added.

For their study, Dr. McConnell and colleagues analyzed data on ALT and hypercoagulability from 68 adults treated at the Yale–New Haven Hospital. The liver and coagulation tests were administered within 5 days of each other.

The team set the ALT cutoff for liver injury at three times the upper limit of normal. Patients with two or more parameters indicating excessive clotting were considered to have a hypercoagulable profile, which Dr. McConnell called “a signature clinical finding of COVID-19 infection.”

Patients with high levels of ALT also experienced elevations in clotting-related factors, such as fibrinogen levels and the activity of factor VIII and factor II. Furthermore, liver injury was significantly associated with hypercoagulability (P < .05).

Because COVID-19 is linked to the proinflammatory IL-6, the investigators examined how this cytokine and its receptor affect human liver sinusoidal cells. Cells exposed to IL-6 and its receptor pumped out factor VIII at levels that were significantly higher than in unexposed cells (P < .01). Exposed cells also produced significantly more von Willebrand factor (P < .05), another prothrombotic molecule, and showed increased expression of genes that induce the expression of factor VIII.

“As we learn more about COVID-19, we find that it is as much a coagulatory as a respiratory disease,” said Tien Dong, MD, PhD, from the University of California, Los Angeles, who was not involved in the study.

These findings are in line with a lot of other COVID-19-related research that suggests a link between hepatocyte injury and clotting disorders, he added.

One important factor is existing liver disease, said Dr. Dong. “If you have COVID-19 on top of that, you’re probably at risk of developing acute liver injury from the infection itself.”

That said, it’s still a good idea to check liver function in patients with COVID-19 and no known liver disease, he advised. Staying on top of these measures will keep the odds of long-term problems “a lot lower.”

There is utility in the findings beyond COVID-19, said Dr. McConnell. They provide “insights into complications of critical illness, in general, in the liver blood vessels” of patients with underlying liver disease.

Dr. McConnell and Dr. Dong have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

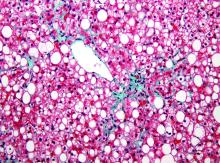

Liquid biopsy captures key NASH pathology hallmarks

Large-scale scanning of serum proteins offers a potential method for noninvasive screening and monitoring of patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), the technique’s developers claim.

By scanning for about 5,000 proteins in nearly 3,000 samples from patients enrolled in studies from the Clinical Research Network in NASH (NASH CRN), Rachel Ostroff, PhD, and colleagues from SomaLogic in Boulder, Colo., created four protein models that mimic results of the major pathologic findings in liver tissue biopsy.

“Concurrent positive results from the protein models had performance characteristics of ‘rule-out’ tests for pathologists’ diagnosis of NASH. These tests may assist in new drug development and medical intervention decisions,” they wrote in a late-breaking poster presented at the virtual annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

“There is no single noninvasive method that can accurately and simultaneously capture steatosis, inflammation, hepatocyte ballooning and fibrosis, the four major pathologic components assessed by biopsy. Each of these is relevant to the multiple mechanisms targeted in drug development for NASH,” they wrote.

To see whether large-scale protemoics could serve as an alternative to invasive liver biopsy for use in clinical trials or in longitudinal studies of NASH, they used a modified aptamer proteomics platform to scan for liver-related proteins. Aptamers are olignonucleotide or peptide molecules designed to home in on a specific target.

They scanned for approximately 5,000 proteins in 2,852 serum samples from 638 patients in a NASH CRN natural history cohort, and in patients enrolled in two NASH treatment trials: the PIVENS trial, which is evaluating pioglitazone versus vitamin E and placebo in nondiabetic patients, and the FLINT trial, which is comparing obeticholic acid with placebo. All of the patients in the natural history cohort and half of all patients in the clinical trial cohorts were included in the training sets, with the remaining half included in the validation set.

The accuracy of the models, as measured by the area under the curve (AUC) of receiver operating characteristics in the training and validation sets, respectively, were as follows:

- Fibrosis: AUC 0.92/0.85.

- Steatosis: AUC 0.95/0.79.

- Inflammation: AUC 0.83/0.72.

- Hepatocyte Ballooning: AUC 0.87/0.83.

“A concurrent positive score for steatosis, inflammation and ballooning predicted the biopsy diagnosis of NASH with an accuracy of 73%,” Ostroff and colleagues wrote.

They also found that model scores applied over time showed improvements in symptoms in the patients on active therapies in the clinical trials, compared with patients on placebo.

A specialist in liver pathology and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease who was not involved in the study said in an interview that she finds the results highly promising.

Impressive results

Elizabeth M. Brunt, MD, emeritus professor of pathology and immunology at Washington University in St. Louis, was a member of the NASH CRN when SomaLogic first proposed using the groups’ data for this study.

“I was impressed with them then, and I am very impressed with what they’re presenting here, and I can’t say that about all the noninvasive tests,” she said. “I think a lot of noninvasive tests are way over-simplifying what NASH is.”

She acknowledged that, although she spent much of her career performing liver biopsies, “you can’t biopsy every single patients who you suspect of having NASH, or certainly if you want to follow them over time – it’s unrealistic,” she said in an interview.

Although the protein scanning method cannot – and is not intended to – replace a well-conducted biopsy with the interpretation of a skilled pathologist, the proteins the company investigators identified can reflect the dynamic nature of liver disease and the liver’s ability to heal itself with a high degree of accuracy and hold promise for both screening patients and for monitoring responses to therapy, Dr. Brunt said.

The study was sponsored by SomaLogic. The authors are employees of the company. Dr. Brunt had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Ostroff R et al. The Liver Disease Meeting Digital Experience, Abstract LP11

Large-scale scanning of serum proteins offers a potential method for noninvasive screening and monitoring of patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), the technique’s developers claim.

By scanning for about 5,000 proteins in nearly 3,000 samples from patients enrolled in studies from the Clinical Research Network in NASH (NASH CRN), Rachel Ostroff, PhD, and colleagues from SomaLogic in Boulder, Colo., created four protein models that mimic results of the major pathologic findings in liver tissue biopsy.

“Concurrent positive results from the protein models had performance characteristics of ‘rule-out’ tests for pathologists’ diagnosis of NASH. These tests may assist in new drug development and medical intervention decisions,” they wrote in a late-breaking poster presented at the virtual annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

“There is no single noninvasive method that can accurately and simultaneously capture steatosis, inflammation, hepatocyte ballooning and fibrosis, the four major pathologic components assessed by biopsy. Each of these is relevant to the multiple mechanisms targeted in drug development for NASH,” they wrote.

To see whether large-scale protemoics could serve as an alternative to invasive liver biopsy for use in clinical trials or in longitudinal studies of NASH, they used a modified aptamer proteomics platform to scan for liver-related proteins. Aptamers are olignonucleotide or peptide molecules designed to home in on a specific target.

They scanned for approximately 5,000 proteins in 2,852 serum samples from 638 patients in a NASH CRN natural history cohort, and in patients enrolled in two NASH treatment trials: the PIVENS trial, which is evaluating pioglitazone versus vitamin E and placebo in nondiabetic patients, and the FLINT trial, which is comparing obeticholic acid with placebo. All of the patients in the natural history cohort and half of all patients in the clinical trial cohorts were included in the training sets, with the remaining half included in the validation set.

The accuracy of the models, as measured by the area under the curve (AUC) of receiver operating characteristics in the training and validation sets, respectively, were as follows:

- Fibrosis: AUC 0.92/0.85.

- Steatosis: AUC 0.95/0.79.

- Inflammation: AUC 0.83/0.72.

- Hepatocyte Ballooning: AUC 0.87/0.83.