User login

Liver steatosis common in English young adults

VIENNA – The prevalence of liver steatosis among unselected English young adults was 21% in a study of just over 4,000 people. The prevalence of apparent liver fibrosis was 2.4%, and among the 21% with steatosis, nearly half – 10% of the studied cohort – had severe, S3 steatosis.

The prevalence of steatosis, a marker of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), seemed to be linked with obesity. Among the 79% of the study group who had no steatosis the obesity prevalence was 6%, compared with a 26% prevalence among those with S1 steatosis, a 33% obesity rate among those with S2 steatosis, and a 57% obesity prevalence among those with S3 steatosis, Kushala Abeysekera, MBBS, said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

He and his associates determined these prevalence rates in a population that excluded people who reported consuming what was deemed “excessive” alcohol use.

Another notable finding was that 1,874 of the same people had undergone ultrasound assessment for NAFLD when they were 18 years old, and that assessment found a prevalence of 2.5% (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 March;99[3]:e410-7), which meant that during the subsequent 6 years prevalence of NAFLD jumped nearly 900%.

Both the 2014 report and the current study used people who had been enrolled in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, a prospective population-based study that began by recruiting a cohort of more than 14,000 pregnant women during 1991-1992, and then followed the more than 13,000 children who resulted from those pregnancies. The study reported by Dr. Abeysekera focused on 4,021 of these children – now young adults – who responded to an invitation to participate in this follow-up, a number that then reduced to 3,600 with informative transient elastography results that quantified fibrosis, and 3,768 with valid Controlled Attenuated Parameter scores from elastography that reflected steatosis extent. Transient elastography is a noninvasive method of measuring liver stiffness using ultrasound and an elastic shear wave (Clin Mol Hepatol. 2012 June;18[2]:163-73).

“To the best of my knowledge, this is the only study that has assessed NAFLD in young adults using transient elastography,” said Dr. Abeysekera, an epidemiologist at the University of Bristol (England).

After subtracting from the study cohort people with excessive alcohol use, the study had transient elastography data from 3,277 24-year-olds that could calculate steatosis severity, and data from 3,128 that could quantify fibrosis.

The analysis also showed a statistically significant link between sex and the presence and severity of steatosis. Among women, 18% had steatosis, including 7% with S3 steatosis, defined as involving at least two-thirds of the liver. Among men, 26% had some degree of steatosis and 14% had the most severe form.

The presence of more severe liver fibrosis also showed a strong link to obesity. The eight people identified with F4 fibrosis (with cirrhosis) had a median body mass index of 32 kg/m2, compared with a median body mass index of 25 kg/m2 or less among those either without fibrosis or with a milder form of F1, F2, or F3 fibrosis.

Dr. Abeysekera reported no disclosures.

VIENNA – The prevalence of liver steatosis among unselected English young adults was 21% in a study of just over 4,000 people. The prevalence of apparent liver fibrosis was 2.4%, and among the 21% with steatosis, nearly half – 10% of the studied cohort – had severe, S3 steatosis.

The prevalence of steatosis, a marker of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), seemed to be linked with obesity. Among the 79% of the study group who had no steatosis the obesity prevalence was 6%, compared with a 26% prevalence among those with S1 steatosis, a 33% obesity rate among those with S2 steatosis, and a 57% obesity prevalence among those with S3 steatosis, Kushala Abeysekera, MBBS, said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

He and his associates determined these prevalence rates in a population that excluded people who reported consuming what was deemed “excessive” alcohol use.

Another notable finding was that 1,874 of the same people had undergone ultrasound assessment for NAFLD when they were 18 years old, and that assessment found a prevalence of 2.5% (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 March;99[3]:e410-7), which meant that during the subsequent 6 years prevalence of NAFLD jumped nearly 900%.

Both the 2014 report and the current study used people who had been enrolled in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, a prospective population-based study that began by recruiting a cohort of more than 14,000 pregnant women during 1991-1992, and then followed the more than 13,000 children who resulted from those pregnancies. The study reported by Dr. Abeysekera focused on 4,021 of these children – now young adults – who responded to an invitation to participate in this follow-up, a number that then reduced to 3,600 with informative transient elastography results that quantified fibrosis, and 3,768 with valid Controlled Attenuated Parameter scores from elastography that reflected steatosis extent. Transient elastography is a noninvasive method of measuring liver stiffness using ultrasound and an elastic shear wave (Clin Mol Hepatol. 2012 June;18[2]:163-73).

“To the best of my knowledge, this is the only study that has assessed NAFLD in young adults using transient elastography,” said Dr. Abeysekera, an epidemiologist at the University of Bristol (England).

After subtracting from the study cohort people with excessive alcohol use, the study had transient elastography data from 3,277 24-year-olds that could calculate steatosis severity, and data from 3,128 that could quantify fibrosis.

The analysis also showed a statistically significant link between sex and the presence and severity of steatosis. Among women, 18% had steatosis, including 7% with S3 steatosis, defined as involving at least two-thirds of the liver. Among men, 26% had some degree of steatosis and 14% had the most severe form.

The presence of more severe liver fibrosis also showed a strong link to obesity. The eight people identified with F4 fibrosis (with cirrhosis) had a median body mass index of 32 kg/m2, compared with a median body mass index of 25 kg/m2 or less among those either without fibrosis or with a milder form of F1, F2, or F3 fibrosis.

Dr. Abeysekera reported no disclosures.

VIENNA – The prevalence of liver steatosis among unselected English young adults was 21% in a study of just over 4,000 people. The prevalence of apparent liver fibrosis was 2.4%, and among the 21% with steatosis, nearly half – 10% of the studied cohort – had severe, S3 steatosis.

The prevalence of steatosis, a marker of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), seemed to be linked with obesity. Among the 79% of the study group who had no steatosis the obesity prevalence was 6%, compared with a 26% prevalence among those with S1 steatosis, a 33% obesity rate among those with S2 steatosis, and a 57% obesity prevalence among those with S3 steatosis, Kushala Abeysekera, MBBS, said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver.

He and his associates determined these prevalence rates in a population that excluded people who reported consuming what was deemed “excessive” alcohol use.

Another notable finding was that 1,874 of the same people had undergone ultrasound assessment for NAFLD when they were 18 years old, and that assessment found a prevalence of 2.5% (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014 March;99[3]:e410-7), which meant that during the subsequent 6 years prevalence of NAFLD jumped nearly 900%.

Both the 2014 report and the current study used people who had been enrolled in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, a prospective population-based study that began by recruiting a cohort of more than 14,000 pregnant women during 1991-1992, and then followed the more than 13,000 children who resulted from those pregnancies. The study reported by Dr. Abeysekera focused on 4,021 of these children – now young adults – who responded to an invitation to participate in this follow-up, a number that then reduced to 3,600 with informative transient elastography results that quantified fibrosis, and 3,768 with valid Controlled Attenuated Parameter scores from elastography that reflected steatosis extent. Transient elastography is a noninvasive method of measuring liver stiffness using ultrasound and an elastic shear wave (Clin Mol Hepatol. 2012 June;18[2]:163-73).

“To the best of my knowledge, this is the only study that has assessed NAFLD in young adults using transient elastography,” said Dr. Abeysekera, an epidemiologist at the University of Bristol (England).

After subtracting from the study cohort people with excessive alcohol use, the study had transient elastography data from 3,277 24-year-olds that could calculate steatosis severity, and data from 3,128 that could quantify fibrosis.

The analysis also showed a statistically significant link between sex and the presence and severity of steatosis. Among women, 18% had steatosis, including 7% with S3 steatosis, defined as involving at least two-thirds of the liver. Among men, 26% had some degree of steatosis and 14% had the most severe form.

The presence of more severe liver fibrosis also showed a strong link to obesity. The eight people identified with F4 fibrosis (with cirrhosis) had a median body mass index of 32 kg/m2, compared with a median body mass index of 25 kg/m2 or less among those either without fibrosis or with a milder form of F1, F2, or F3 fibrosis.

Dr. Abeysekera reported no disclosures.

REPORTING FROM ILC 2019

Obeticholic acid reversed NASH liver fibrosis in phase 3 trial

VIENNA – making obeticholic acid the first agent proven to improve the course of this disease.

“There is no doubt that with these data we have changed the treatment” of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), Zobair M. Younossi, MD, of Inova Fairfax Medical Campus in Falls Church, Va., said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver. “We are at a watershed moment” in NASH treatment, Dr. Younossi added in a video interview.

Until now “we have had no effective treatments for NASH. This is the first success in a phase 3 trial; obeticholic acid looks very promising,” commented Philip N. Newsome, PhD, professor of experimental hepatology at the University of Birmingham (England).

Obeticholic acid (OCA), an agonist of the farnesoid X receptor, already has Food and Drug Administration marketing approval for the indication of primary biliary cholangitis, a much rarer disease than NASH.

The REGENERATE (Randomized Global Phase 3 Study to Evaluate the Impact on NASH With Fibrosis of Obeticholic Acid Treatment) trial has so far enrolled 931 patients at about 350 sites in 20 countries, including the United States, and followed them during 18 months of treatment, the prespecified time for an interim analysis. The study enrolled adults with biopsy-proven NASH and generally focused on patients with either stage 2 or 3 liver fibrosis and a nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity score of at least 4. Enrolled patients averaged about 55 years old, slightly more than half the enrolled patients had type 2 diabetes, and more than half had stage 3 fibrosis.

The study design included two coprimary endpoints, and specified that a statistically significant finding for either outcome meant a positive trial result, but the design also prespecified that the benefit would need to meet a stringent definition of statistical significance, compared with placebo patients, with a P value of no more than .01. REGENERATE tested two different OCA dosages, 10 mg or 25 mg, once daily. The results showed a trend for benefit from the smaller dosage, but these effects did not achieve statistical significance.

For the primary endpoint of regression of liver fibrosis by at least one stage with no worsening of NASH the intention-to-treat analysis showed after 18 months a 13% rate with placebo, a 21% rate with the 10-mg dosage, and a 23% rate with the 25-mg dosage, a statistically significant improvement over placebo for the higher dosage.

The second primary endpoint was resolution of NASH without worsening liver fibrosis, which occurred in 8% of placebo patients, 11% of patients on 10 mg OCA/day and 12% of those on 25 mg/day. The differences between each of the active groups and the controls were not statistically significant for this endpoint.

Among the 931 enrolled patients 668 (72%) actually received treatment fully consistent with the study protocol, and among these per-protocol patients the benefit from 25 mg/day OCA was even more striking: a 28% rate of fibrosis regression, compared with 13% in the control patients. Regression by at least two fibrotic stages occurred in 5% of placebo patients and 13% of those on 25 mg/day OCA. Many treated patients also showed normalizations of liver enzyme levels.

Adverse events on OCA were mostly mild or moderate, with similar rates of serious adverse events in the OCA groups and in control patients. The most common adverse effect on OCA treatment was pruritus, a previously described effect, reported by 51% of patients on the 25 mg/day dosage and by 19% of control patients.

REGENERATE will continue until a goal level of endpoint events occur, and may eventually enroll as many as 2,400 patients and extend for a few more years. By then, Dr. Younossi said, he hopes that an analysis will be possible of “harder” endpoints than fibrosis, such as development of cirrhosis. He noted, however, that the FDA has designated fibrosis regression as a valid surrogate endpoint for assessing treatment efficacy for NASH.

Already on the U.S. market, a single 10-mg OCA pill currently retails for almost $230; a 25-mg formulation is not currently marketed. Dr. Younossi said that subsequent studies will assess the cost-effectiveness of OCA treatment for NASH. He also hopes that further study of patient characteristics will identify which NASH patients are most likely to respond to OCA. Eventually, OCA may be part of a multidrug strategy for treating this disease, Dr. Younossi said.

REGENERATE was sponsored by Intercept, the company that markets obeticholic acid (Ocaliva). Dr. Younossi is a consultant to and has received research funding from Intercept. He has also been a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Quest, Siemens, Terns Pharmaceutical, and Viking Therapeutics. Dr. Newsome has been a consultant or speaker for Intercept as well as Boehringer Ingelheim, Dignity Sciences, Johnson & Johnson, Novo Nordisk, and Shire, and he has received research funding from Pharmaxis and Boehringer Ingelheim.

VIENNA – making obeticholic acid the first agent proven to improve the course of this disease.

“There is no doubt that with these data we have changed the treatment” of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), Zobair M. Younossi, MD, of Inova Fairfax Medical Campus in Falls Church, Va., said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver. “We are at a watershed moment” in NASH treatment, Dr. Younossi added in a video interview.

Until now “we have had no effective treatments for NASH. This is the first success in a phase 3 trial; obeticholic acid looks very promising,” commented Philip N. Newsome, PhD, professor of experimental hepatology at the University of Birmingham (England).

Obeticholic acid (OCA), an agonist of the farnesoid X receptor, already has Food and Drug Administration marketing approval for the indication of primary biliary cholangitis, a much rarer disease than NASH.

The REGENERATE (Randomized Global Phase 3 Study to Evaluate the Impact on NASH With Fibrosis of Obeticholic Acid Treatment) trial has so far enrolled 931 patients at about 350 sites in 20 countries, including the United States, and followed them during 18 months of treatment, the prespecified time for an interim analysis. The study enrolled adults with biopsy-proven NASH and generally focused on patients with either stage 2 or 3 liver fibrosis and a nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity score of at least 4. Enrolled patients averaged about 55 years old, slightly more than half the enrolled patients had type 2 diabetes, and more than half had stage 3 fibrosis.

The study design included two coprimary endpoints, and specified that a statistically significant finding for either outcome meant a positive trial result, but the design also prespecified that the benefit would need to meet a stringent definition of statistical significance, compared with placebo patients, with a P value of no more than .01. REGENERATE tested two different OCA dosages, 10 mg or 25 mg, once daily. The results showed a trend for benefit from the smaller dosage, but these effects did not achieve statistical significance.

For the primary endpoint of regression of liver fibrosis by at least one stage with no worsening of NASH the intention-to-treat analysis showed after 18 months a 13% rate with placebo, a 21% rate with the 10-mg dosage, and a 23% rate with the 25-mg dosage, a statistically significant improvement over placebo for the higher dosage.

The second primary endpoint was resolution of NASH without worsening liver fibrosis, which occurred in 8% of placebo patients, 11% of patients on 10 mg OCA/day and 12% of those on 25 mg/day. The differences between each of the active groups and the controls were not statistically significant for this endpoint.

Among the 931 enrolled patients 668 (72%) actually received treatment fully consistent with the study protocol, and among these per-protocol patients the benefit from 25 mg/day OCA was even more striking: a 28% rate of fibrosis regression, compared with 13% in the control patients. Regression by at least two fibrotic stages occurred in 5% of placebo patients and 13% of those on 25 mg/day OCA. Many treated patients also showed normalizations of liver enzyme levels.

Adverse events on OCA were mostly mild or moderate, with similar rates of serious adverse events in the OCA groups and in control patients. The most common adverse effect on OCA treatment was pruritus, a previously described effect, reported by 51% of patients on the 25 mg/day dosage and by 19% of control patients.

REGENERATE will continue until a goal level of endpoint events occur, and may eventually enroll as many as 2,400 patients and extend for a few more years. By then, Dr. Younossi said, he hopes that an analysis will be possible of “harder” endpoints than fibrosis, such as development of cirrhosis. He noted, however, that the FDA has designated fibrosis regression as a valid surrogate endpoint for assessing treatment efficacy for NASH.

Already on the U.S. market, a single 10-mg OCA pill currently retails for almost $230; a 25-mg formulation is not currently marketed. Dr. Younossi said that subsequent studies will assess the cost-effectiveness of OCA treatment for NASH. He also hopes that further study of patient characteristics will identify which NASH patients are most likely to respond to OCA. Eventually, OCA may be part of a multidrug strategy for treating this disease, Dr. Younossi said.

REGENERATE was sponsored by Intercept, the company that markets obeticholic acid (Ocaliva). Dr. Younossi is a consultant to and has received research funding from Intercept. He has also been a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Quest, Siemens, Terns Pharmaceutical, and Viking Therapeutics. Dr. Newsome has been a consultant or speaker for Intercept as well as Boehringer Ingelheim, Dignity Sciences, Johnson & Johnson, Novo Nordisk, and Shire, and he has received research funding from Pharmaxis and Boehringer Ingelheim.

VIENNA – making obeticholic acid the first agent proven to improve the course of this disease.

“There is no doubt that with these data we have changed the treatment” of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), Zobair M. Younossi, MD, of Inova Fairfax Medical Campus in Falls Church, Va., said at the meeting sponsored by the European Association for the Study of the Liver. “We are at a watershed moment” in NASH treatment, Dr. Younossi added in a video interview.

Until now “we have had no effective treatments for NASH. This is the first success in a phase 3 trial; obeticholic acid looks very promising,” commented Philip N. Newsome, PhD, professor of experimental hepatology at the University of Birmingham (England).

Obeticholic acid (OCA), an agonist of the farnesoid X receptor, already has Food and Drug Administration marketing approval for the indication of primary biliary cholangitis, a much rarer disease than NASH.

The REGENERATE (Randomized Global Phase 3 Study to Evaluate the Impact on NASH With Fibrosis of Obeticholic Acid Treatment) trial has so far enrolled 931 patients at about 350 sites in 20 countries, including the United States, and followed them during 18 months of treatment, the prespecified time for an interim analysis. The study enrolled adults with biopsy-proven NASH and generally focused on patients with either stage 2 or 3 liver fibrosis and a nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity score of at least 4. Enrolled patients averaged about 55 years old, slightly more than half the enrolled patients had type 2 diabetes, and more than half had stage 3 fibrosis.

The study design included two coprimary endpoints, and specified that a statistically significant finding for either outcome meant a positive trial result, but the design also prespecified that the benefit would need to meet a stringent definition of statistical significance, compared with placebo patients, with a P value of no more than .01. REGENERATE tested two different OCA dosages, 10 mg or 25 mg, once daily. The results showed a trend for benefit from the smaller dosage, but these effects did not achieve statistical significance.

For the primary endpoint of regression of liver fibrosis by at least one stage with no worsening of NASH the intention-to-treat analysis showed after 18 months a 13% rate with placebo, a 21% rate with the 10-mg dosage, and a 23% rate with the 25-mg dosage, a statistically significant improvement over placebo for the higher dosage.

The second primary endpoint was resolution of NASH without worsening liver fibrosis, which occurred in 8% of placebo patients, 11% of patients on 10 mg OCA/day and 12% of those on 25 mg/day. The differences between each of the active groups and the controls were not statistically significant for this endpoint.

Among the 931 enrolled patients 668 (72%) actually received treatment fully consistent with the study protocol, and among these per-protocol patients the benefit from 25 mg/day OCA was even more striking: a 28% rate of fibrosis regression, compared with 13% in the control patients. Regression by at least two fibrotic stages occurred in 5% of placebo patients and 13% of those on 25 mg/day OCA. Many treated patients also showed normalizations of liver enzyme levels.

Adverse events on OCA were mostly mild or moderate, with similar rates of serious adverse events in the OCA groups and in control patients. The most common adverse effect on OCA treatment was pruritus, a previously described effect, reported by 51% of patients on the 25 mg/day dosage and by 19% of control patients.

REGENERATE will continue until a goal level of endpoint events occur, and may eventually enroll as many as 2,400 patients and extend for a few more years. By then, Dr. Younossi said, he hopes that an analysis will be possible of “harder” endpoints than fibrosis, such as development of cirrhosis. He noted, however, that the FDA has designated fibrosis regression as a valid surrogate endpoint for assessing treatment efficacy for NASH.

Already on the U.S. market, a single 10-mg OCA pill currently retails for almost $230; a 25-mg formulation is not currently marketed. Dr. Younossi said that subsequent studies will assess the cost-effectiveness of OCA treatment for NASH. He also hopes that further study of patient characteristics will identify which NASH patients are most likely to respond to OCA. Eventually, OCA may be part of a multidrug strategy for treating this disease, Dr. Younossi said.

REGENERATE was sponsored by Intercept, the company that markets obeticholic acid (Ocaliva). Dr. Younossi is a consultant to and has received research funding from Intercept. He has also been a consultant to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Quest, Siemens, Terns Pharmaceutical, and Viking Therapeutics. Dr. Newsome has been a consultant or speaker for Intercept as well as Boehringer Ingelheim, Dignity Sciences, Johnson & Johnson, Novo Nordisk, and Shire, and he has received research funding from Pharmaxis and Boehringer Ingelheim.

REPORTING FROM ILC 2019

An HCV-infected population showed gaps in HBV testing, vaccination, and care

Assessment of a large cohort of hepatitis C virus (HCV)–infected patients revealed a high prevalence of current or past hepatitis B virus. However, within this cohort, there were notable gaps in HBV testing, directed care, and vaccination, according to Aaron M. Harris, MD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dr. Harris and his colleagues abstracted patient-level data from the Grady Health System EHR in August 2016 to create an HCV patient registry. They found that, among 4,224 HCV-infected patients, 3,629 (86%) had test results for the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), with 43 (1.2%) being HBsAg positive.

“Our results identified a gap in care as a minority of HBsAg-positive patients with HCV coinfection received HBV DNA and/or e-antigen [HBeAg] testing,” the researchers stated.

Overall, only 2,342 (55.4%) patients had test results for all three HBV serologic markers. Among these, 789 (33.7%) were anti-HBc positive only, 678 (28.9%) were anti-HBc/anti-HBs positive, 190 (8.1%) were anti-HBs positive only, and 642 (27.4%) were HBV susceptible. In addition, only 50% of the HBV-susceptible patients received at least one dose of hepatitis B vaccine, according to the report published in Vaccine.

“Strategies are needed to increase hepatitis B testing, linkage to hepatitis B–directed care of HBV/HCV-coinfected patients, and to increase uptake in hepatitis B vaccination for HCV-infected patients within the Grady Health System,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the CDC and the authors reported that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Harris AM et al. Vaccine. 2019;37:2188-93.

Assessment of a large cohort of hepatitis C virus (HCV)–infected patients revealed a high prevalence of current or past hepatitis B virus. However, within this cohort, there were notable gaps in HBV testing, directed care, and vaccination, according to Aaron M. Harris, MD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dr. Harris and his colleagues abstracted patient-level data from the Grady Health System EHR in August 2016 to create an HCV patient registry. They found that, among 4,224 HCV-infected patients, 3,629 (86%) had test results for the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), with 43 (1.2%) being HBsAg positive.

“Our results identified a gap in care as a minority of HBsAg-positive patients with HCV coinfection received HBV DNA and/or e-antigen [HBeAg] testing,” the researchers stated.

Overall, only 2,342 (55.4%) patients had test results for all three HBV serologic markers. Among these, 789 (33.7%) were anti-HBc positive only, 678 (28.9%) were anti-HBc/anti-HBs positive, 190 (8.1%) were anti-HBs positive only, and 642 (27.4%) were HBV susceptible. In addition, only 50% of the HBV-susceptible patients received at least one dose of hepatitis B vaccine, according to the report published in Vaccine.

“Strategies are needed to increase hepatitis B testing, linkage to hepatitis B–directed care of HBV/HCV-coinfected patients, and to increase uptake in hepatitis B vaccination for HCV-infected patients within the Grady Health System,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the CDC and the authors reported that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Harris AM et al. Vaccine. 2019;37:2188-93.

Assessment of a large cohort of hepatitis C virus (HCV)–infected patients revealed a high prevalence of current or past hepatitis B virus. However, within this cohort, there were notable gaps in HBV testing, directed care, and vaccination, according to Aaron M. Harris, MD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dr. Harris and his colleagues abstracted patient-level data from the Grady Health System EHR in August 2016 to create an HCV patient registry. They found that, among 4,224 HCV-infected patients, 3,629 (86%) had test results for the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), with 43 (1.2%) being HBsAg positive.

“Our results identified a gap in care as a minority of HBsAg-positive patients with HCV coinfection received HBV DNA and/or e-antigen [HBeAg] testing,” the researchers stated.

Overall, only 2,342 (55.4%) patients had test results for all three HBV serologic markers. Among these, 789 (33.7%) were anti-HBc positive only, 678 (28.9%) were anti-HBc/anti-HBs positive, 190 (8.1%) were anti-HBs positive only, and 642 (27.4%) were HBV susceptible. In addition, only 50% of the HBV-susceptible patients received at least one dose of hepatitis B vaccine, according to the report published in Vaccine.

“Strategies are needed to increase hepatitis B testing, linkage to hepatitis B–directed care of HBV/HCV-coinfected patients, and to increase uptake in hepatitis B vaccination for HCV-infected patients within the Grady Health System,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the CDC and the authors reported that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Harris AM et al. Vaccine. 2019;37:2188-93.

FROM VACCINE

DDNA19: The role of the microbiome in liver disease

Stephen Brant, MD, and Nikolaos Pyrsopoulos, MD, discuss the latest news and the role of the microbiome in liver diseases at Digestive Diseases: New Advances, jointly provided by Rutgers and Global Academy for Medical Education.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

Stephen Brant, MD, and Nikolaos Pyrsopoulos, MD, discuss the latest news and the role of the microbiome in liver diseases at Digestive Diseases: New Advances, jointly provided by Rutgers and Global Academy for Medical Education.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

Stephen Brant, MD, and Nikolaos Pyrsopoulos, MD, discuss the latest news and the role of the microbiome in liver diseases at Digestive Diseases: New Advances, jointly provided by Rutgers and Global Academy for Medical Education.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

REPORTING FROM DIGESTIVE DISEASES: NEW ADVANCES

Future of NASH care means multiple targets, multiple providers, expert says

PHILADELPHIA – While current treatment options are limited for patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), a number of potential agents in clinical trials, Zobair M. Younossi, MD, MPH, said here at the 6th annual Digestive Diseases: New Advances conference.

With agents currently available and those to come, the future will be focused on long-term management of NASH as a chronic disease in specialized centers, according to Dr. Younossi, chairman in the department of medicine at Inova Fairfax Hospital and vice president for research at Inova Health System, both in Falls Church, Va.

“We are not going to be able to cure NASH – we need to manage it,” Dr. Younossi said in a podium presentation. “NASH will be managed like type 2 diabetes. It’s not going to be treated like hepatitis C.”

Current treatment options are limited, with no Food and Drug Administration–approved options, and just two agents, vitamin E and pioglitazone, supported by guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), Dr. Younossi said.

Public health interventions are needed to address the obesity and type 2 diabetes that are “the root of this disease,” Dr. Younossi said at the meeting, which was jointly provided by Rutgers and Global Academy for Medical Education.

Current AASLD guidance is based on studies suggesting that weight loss in the 3%-5% range may improve steatosis, and a 7%-10% weight loss can improve most histologic features of NASH, including fibrosis.

“The problem is that this is very hard to achieve,” Dr. Younossi said, adding that it is also hard to maintain. In a 2011 meta-analysis of clinical trials for reduction in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, only a small minority of patients were able to maintain weight loss.

Bariatric surgery may be “very effective” for weight loss in the right patients, with some trials showing a proportion of patients maintaining improvement at 5-year follow-up, he said.

Exercise alone might prevent or reduce steatosis, but its effects on other aspects of liver histology, such as fibrosis, remain unknown, Dr. Younossi said.

Pioglitazone improves liver histology in patients with biopsy-proven NASH, although the benefits and risks, including potential adverse effects such as bone loss, diastolic dysfunction, or weight gain, should be discussed with each individual patient, he said.

Dr. Younossi highlighted randomized phase 3 trials for several agents that could figure into the treatment paradigm of NASH in the future by targeting different promoters of NASH and fibrosis progression. One of those was elafibranor, which targets the PPAR alpha/gamma pathways and is being evaluated versus placebo in NASH patients in the phase 3 RESOLVE-IT study. In a post hoc analysis of a previous randomized trial, the treatment resolved NASH without fibrosis worsening.

Other agents being evaluated in phase 3 trials include the CCR2/CCR5 receptor blocker cenicriviroc, the FXR agonist obeticholic acid, and the ASK-1 inhibitor selonsertib, Dr. Younossi said.

Optimal NASH care in the future may be based on targeting multiple such pathways, with patients increasingly treated at specialized centers that incorporate not only hepatologists, but also diabetes experts, dietitians, and exercise specialists.

“My own belief is that you have to treat this in the long term and also in a multidisciplinary sort of approach,” he said.

Dr. Younossi indicated that he is a consultant for Gilead, Intercept, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novo Nordisk, Viking, Terms, Shionogi, AbbVie, Merck, and Novartis.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

PHILADELPHIA – While current treatment options are limited for patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), a number of potential agents in clinical trials, Zobair M. Younossi, MD, MPH, said here at the 6th annual Digestive Diseases: New Advances conference.

With agents currently available and those to come, the future will be focused on long-term management of NASH as a chronic disease in specialized centers, according to Dr. Younossi, chairman in the department of medicine at Inova Fairfax Hospital and vice president for research at Inova Health System, both in Falls Church, Va.

“We are not going to be able to cure NASH – we need to manage it,” Dr. Younossi said in a podium presentation. “NASH will be managed like type 2 diabetes. It’s not going to be treated like hepatitis C.”

Current treatment options are limited, with no Food and Drug Administration–approved options, and just two agents, vitamin E and pioglitazone, supported by guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), Dr. Younossi said.

Public health interventions are needed to address the obesity and type 2 diabetes that are “the root of this disease,” Dr. Younossi said at the meeting, which was jointly provided by Rutgers and Global Academy for Medical Education.

Current AASLD guidance is based on studies suggesting that weight loss in the 3%-5% range may improve steatosis, and a 7%-10% weight loss can improve most histologic features of NASH, including fibrosis.

“The problem is that this is very hard to achieve,” Dr. Younossi said, adding that it is also hard to maintain. In a 2011 meta-analysis of clinical trials for reduction in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, only a small minority of patients were able to maintain weight loss.

Bariatric surgery may be “very effective” for weight loss in the right patients, with some trials showing a proportion of patients maintaining improvement at 5-year follow-up, he said.

Exercise alone might prevent or reduce steatosis, but its effects on other aspects of liver histology, such as fibrosis, remain unknown, Dr. Younossi said.

Pioglitazone improves liver histology in patients with biopsy-proven NASH, although the benefits and risks, including potential adverse effects such as bone loss, diastolic dysfunction, or weight gain, should be discussed with each individual patient, he said.

Dr. Younossi highlighted randomized phase 3 trials for several agents that could figure into the treatment paradigm of NASH in the future by targeting different promoters of NASH and fibrosis progression. One of those was elafibranor, which targets the PPAR alpha/gamma pathways and is being evaluated versus placebo in NASH patients in the phase 3 RESOLVE-IT study. In a post hoc analysis of a previous randomized trial, the treatment resolved NASH without fibrosis worsening.

Other agents being evaluated in phase 3 trials include the CCR2/CCR5 receptor blocker cenicriviroc, the FXR agonist obeticholic acid, and the ASK-1 inhibitor selonsertib, Dr. Younossi said.

Optimal NASH care in the future may be based on targeting multiple such pathways, with patients increasingly treated at specialized centers that incorporate not only hepatologists, but also diabetes experts, dietitians, and exercise specialists.

“My own belief is that you have to treat this in the long term and also in a multidisciplinary sort of approach,” he said.

Dr. Younossi indicated that he is a consultant for Gilead, Intercept, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novo Nordisk, Viking, Terms, Shionogi, AbbVie, Merck, and Novartis.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

PHILADELPHIA – While current treatment options are limited for patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), a number of potential agents in clinical trials, Zobair M. Younossi, MD, MPH, said here at the 6th annual Digestive Diseases: New Advances conference.

With agents currently available and those to come, the future will be focused on long-term management of NASH as a chronic disease in specialized centers, according to Dr. Younossi, chairman in the department of medicine at Inova Fairfax Hospital and vice president for research at Inova Health System, both in Falls Church, Va.

“We are not going to be able to cure NASH – we need to manage it,” Dr. Younossi said in a podium presentation. “NASH will be managed like type 2 diabetes. It’s not going to be treated like hepatitis C.”

Current treatment options are limited, with no Food and Drug Administration–approved options, and just two agents, vitamin E and pioglitazone, supported by guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), Dr. Younossi said.

Public health interventions are needed to address the obesity and type 2 diabetes that are “the root of this disease,” Dr. Younossi said at the meeting, which was jointly provided by Rutgers and Global Academy for Medical Education.

Current AASLD guidance is based on studies suggesting that weight loss in the 3%-5% range may improve steatosis, and a 7%-10% weight loss can improve most histologic features of NASH, including fibrosis.

“The problem is that this is very hard to achieve,” Dr. Younossi said, adding that it is also hard to maintain. In a 2011 meta-analysis of clinical trials for reduction in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, only a small minority of patients were able to maintain weight loss.

Bariatric surgery may be “very effective” for weight loss in the right patients, with some trials showing a proportion of patients maintaining improvement at 5-year follow-up, he said.

Exercise alone might prevent or reduce steatosis, but its effects on other aspects of liver histology, such as fibrosis, remain unknown, Dr. Younossi said.

Pioglitazone improves liver histology in patients with biopsy-proven NASH, although the benefits and risks, including potential adverse effects such as bone loss, diastolic dysfunction, or weight gain, should be discussed with each individual patient, he said.

Dr. Younossi highlighted randomized phase 3 trials for several agents that could figure into the treatment paradigm of NASH in the future by targeting different promoters of NASH and fibrosis progression. One of those was elafibranor, which targets the PPAR alpha/gamma pathways and is being evaluated versus placebo in NASH patients in the phase 3 RESOLVE-IT study. In a post hoc analysis of a previous randomized trial, the treatment resolved NASH without fibrosis worsening.

Other agents being evaluated in phase 3 trials include the CCR2/CCR5 receptor blocker cenicriviroc, the FXR agonist obeticholic acid, and the ASK-1 inhibitor selonsertib, Dr. Younossi said.

Optimal NASH care in the future may be based on targeting multiple such pathways, with patients increasingly treated at specialized centers that incorporate not only hepatologists, but also diabetes experts, dietitians, and exercise specialists.

“My own belief is that you have to treat this in the long term and also in a multidisciplinary sort of approach,” he said.

Dr. Younossi indicated that he is a consultant for Gilead, Intercept, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novo Nordisk, Viking, Terms, Shionogi, AbbVie, Merck, and Novartis.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM DIGESTIVE DISEASES: NEW ADVANCES

Novel microbiome signature may detect NAFLD-cirrhosis

according to results from a study published in Nature Communications.

“Limited data exist concerning the diagnostic accuracy of gut microbiome–derived signatures for detecting NAFLD-cirrhosis,” wrote Cyrielle Caussy, MD, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, along with her colleagues.

The researchers conducted a cross-sectional analysis of 203 patients with NAFLD. Data was collected from a twin and family cohort with a total of 98 probands that included the complete spectrum of the disease. In addition, 105 first-degree relatives of the probands were also included.

The team analyzed stool samples of participants using MRI and assessed whether the novel signature could accurately identify cirrhosis in NAFLD.

After analysis, the researchers found that in a specific cohort of probands, the microbial biomarker showed strong diagnostic accuracy for identifying cirrhosis in patients with NAFLD (area under the ROC curve, 0.92). These findings were validated in another cohort of first-degree relatives of the proband group (AUROC, 0.87).

The authors acknowledged that a key limitation of the analysis was that it was only a single-center study. As a result, the widespread generalizability of the findings could be restricted.

“This conveniently assessed microbial biomarker could present an adjunct tool to current invasive approaches to determine stage of liver disease,” they concluded.

The study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health and Janssen. The authors reported financial affiliations with the American Gastroenterological Association, Atlantic Philanthropies, the John A. Hartford Foundation, and the Association of Specialty Professors.

SOURCE: Caussy C et al. Nat Commun. 2019 Mar 29. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09455-9.

according to results from a study published in Nature Communications.

“Limited data exist concerning the diagnostic accuracy of gut microbiome–derived signatures for detecting NAFLD-cirrhosis,” wrote Cyrielle Caussy, MD, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, along with her colleagues.

The researchers conducted a cross-sectional analysis of 203 patients with NAFLD. Data was collected from a twin and family cohort with a total of 98 probands that included the complete spectrum of the disease. In addition, 105 first-degree relatives of the probands were also included.

The team analyzed stool samples of participants using MRI and assessed whether the novel signature could accurately identify cirrhosis in NAFLD.

After analysis, the researchers found that in a specific cohort of probands, the microbial biomarker showed strong diagnostic accuracy for identifying cirrhosis in patients with NAFLD (area under the ROC curve, 0.92). These findings were validated in another cohort of first-degree relatives of the proband group (AUROC, 0.87).

The authors acknowledged that a key limitation of the analysis was that it was only a single-center study. As a result, the widespread generalizability of the findings could be restricted.

“This conveniently assessed microbial biomarker could present an adjunct tool to current invasive approaches to determine stage of liver disease,” they concluded.

The study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health and Janssen. The authors reported financial affiliations with the American Gastroenterological Association, Atlantic Philanthropies, the John A. Hartford Foundation, and the Association of Specialty Professors.

SOURCE: Caussy C et al. Nat Commun. 2019 Mar 29. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09455-9.

according to results from a study published in Nature Communications.

“Limited data exist concerning the diagnostic accuracy of gut microbiome–derived signatures for detecting NAFLD-cirrhosis,” wrote Cyrielle Caussy, MD, PhD, of the University of California, San Diego, along with her colleagues.

The researchers conducted a cross-sectional analysis of 203 patients with NAFLD. Data was collected from a twin and family cohort with a total of 98 probands that included the complete spectrum of the disease. In addition, 105 first-degree relatives of the probands were also included.

The team analyzed stool samples of participants using MRI and assessed whether the novel signature could accurately identify cirrhosis in NAFLD.

After analysis, the researchers found that in a specific cohort of probands, the microbial biomarker showed strong diagnostic accuracy for identifying cirrhosis in patients with NAFLD (area under the ROC curve, 0.92). These findings were validated in another cohort of first-degree relatives of the proband group (AUROC, 0.87).

The authors acknowledged that a key limitation of the analysis was that it was only a single-center study. As a result, the widespread generalizability of the findings could be restricted.

“This conveniently assessed microbial biomarker could present an adjunct tool to current invasive approaches to determine stage of liver disease,” they concluded.

The study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health and Janssen. The authors reported financial affiliations with the American Gastroenterological Association, Atlantic Philanthropies, the John A. Hartford Foundation, and the Association of Specialty Professors.

SOURCE: Caussy C et al. Nat Commun. 2019 Mar 29. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09455-9.

FROM NATURE COMMUNICATIONS

A woman, age 35, with new-onset ascites

A 35-year-old woman is admitted to the hospital with a 5-day history of abdominal distention and jaundice. She reports no history of fever, chills, night sweats, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, changes in urine color, change in stool color, weight loss, weight gain, or loss of appetite.

She is petite, with a body mass index of 19.4 kg/m2. She has no known history of medical conditions or surgery and is not taking any medications. Her family history is unremarkable, and she denies current or past tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use.

RECENT TRAVEL

She says that during a trip to Central America several months ago, she had suffered a seizure and was taken to a local hospital, where laboratory testing revealed elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels. She says that the rest of the workup at that time was normal.

About 1 week after that incident, she returned home and saw her primary care physician, who ordered further testing, which showed mild hyperbilirubinemia and mild elevation of AST and ALT levels. Her physician attributed the elevations to atovaquone, which she had been taking for malaria prophylaxis, as repeat testing 2 weeks later showed improvement in AST and ALT levels.

The patient says she returned to her normal state of health until about 5 days ago, when she noticed jaundice and abdominal distention, but without abdominal pain, dark urine, or clay-colored stools. She became concerned and went to her local hospital. Testing there noted mild elevation of AST and ALT, as well as an elevated international normalized ratio (INR) and hyperbilirubinemia. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis showed hepatomegaly with possible fatty liver. Because of these results, the patient was transferred to our institution for further evaluation.

EVALUATION AT OUR INSTITUTION

On examination at our institution, she is afebrile, and vital signs are within normal ranges. She has bilateral scleral icterus and diffuse jaundice, but no other skin finding such as rash or spider angioma. She has no lymphadenopathy. Her abdomen is distended, with tense ascites, and her liver is tender to palpation. The tip of the spleen is not palpable.

The cardiovascular examination reveals no murmurs, rubs, or gallops, but she has jugular venous distention and +2 pitting edema of both lower extremities.

On respiratory examination, there is dullness to percussion, with slight crackles on auscultation at the right lung base. The neurologic examination is normal.

Table 1 shows the results of initial laboratory testing.

1. Which study would provide the most information on the cause of ascites?

- Abdominal ultrasonography

- Abdominal paracentesis with ascitic fluid analysis

- Chest radiography

- Echocardiography

- Urine protein-to-creatinine ratio

Abdominal paracentesis with ascitic fluid analysis is the essential study for any patient with clinically apparent new-onset ascites.1–3 It is the study that provides the most information on the cause of ascites.

In our patient, abdominal paracentesis yields 1,000 mL of straw-colored ascitic fluid, and analysis shows 86 nucleated cells, 28 of which are polymorphonuclear cells, and 0 red blood cells, with negative Gram stain and culture. The ascitic albumin level is 0.85 g/dL, with an ascitic protein of 1.1 g/dL.

Abdominal ultrasonography shows a diffusely echogenic liver, no focal lesions, moderate ascites, normal portal vein flow, no intrahepatic or extrahepatic biliary duct dilation, normal kidney sizes, no hydronephrosis, and no intra-abdominal mass. Chest radiography is clear with no sign of consolidation, edema, or effusion. Echocardiography shows a normal left ventricular ejection fraction with no valvular disease or pericardial effusion. A random urine protein-creatinine ratio is normal at 0.1 (reference range < 0.2).

2. What is the most likely cause of her ascites based on the workup to this point?

- Cirrhosis

- Heart failure

- Nephrotic syndrome

- Portal vein thrombus

- Abdominal malignancy

- Malaria

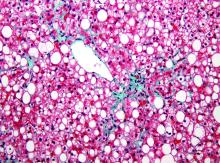

An initial approach to ascitic fluid analysis is to calculate the serum-ascites albumin gradient (SAAG). The SAAG is calculated as the serum albumin level minus the ascitic fluid albumin level.4,5 This is useful in determining the cause of the ascites (Figure 1).4,5 A gradient of 1.1 g/dL or higher indicates portal hypertension.4,5

Common causes of portal hypertension include cirrhosis, alcoholic hepatitis, heart failure, vascular occlusion syndromes (eg, Budd-Chiari syndrome, portal vein thrombosis), idiopathic portal fibrosis, and metastatic liver disease.5,6

If portal hypertension is present based on the SAAG, the next step is to review the ascitic protein level to help distinguish between a hepatic and a cardiac etiology of the ascites. An ascitic protein level less than 2.5 g/dL indicates a primary liver pathology (eg, cirrhosis). An ascitic protein level of 2.5 g/dL or greater typically indicates a cardiac condition (eg, heart failure, pericardial disease) with secondary congestive hepatopathy.5,6

If the SAAG is less than 1.1 g/dL, the ascites is likely not from portal hypertension. Typical causes of a low SAAG include infection, malignancy, pancreatic ascites, and nephrotic syndrome.5,6

In our patient, the SAAG is 1.35 g/dL (2.2 g/dL minus 0.85 g/dL), ie, elevated and due to portal hypertension. With an SAAG of 1.1 g/dL or greater and an ascitic fluid protein level less than 2.5 g/dL, as in our patient, the most likely cause is cirrhosis.

Heart failure is unlikely based on her normal brain natriuretic peptide level, an ascitic fluid protein level below 2.5 g/dL, and normal results on echocardiography. Nephrotic syndrome is also very unlikely based on the patient’s normal random urine protein-creatinine ratio. Portal vein thrombus and abdominal malignancy are essentially ruled out by the negative results of Doppler abdominal ultrasonography, with normal venous flow and no intra-abdominal mass and coupled with an elevated SAAG.

Although the patient has a history of travel, the incubation period for malaria would not fit the time frame of presentation. Also, she did not have typical malarial symptoms, her rapid malaria test was negative, and a peripheral blood smear for blood parasites was negative. It should be noted, however, that Plasmodium malariae infection classically presents with flulike symptoms and can resemble nephrotic syndrome, including peripheral edema, ascites, heavy proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, and hyperlipidemia.7

3. In which patients is antibiotic prophylaxis against spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) appropriate?

- Any patient with cirrhosis

- Any patient with cirrhosis who is hospitalized

- Any patient with cirrhosis and an ascitic fluid protein level below 2.0 g/dL

- Any patient with cirrhosis and a history of SBP

Any patient with cirrhosis and a history of SBP should receive prophylactic antibiotics,8 as should any patient deemed at high risk of SBP. It is indicated in the following patients:

- Patients with cirrhosis and gastrointestinal bleeding9,10

- Patients with cirrhosis and a previous episode of SBP8

- Patients with cirrhosis and an ascitic fluid protein level less than 1.5 g/dL with either impaired renal function (creatinine ≥ 1.2 mg/dL, blood urea nitrogen level ≥ 25 mg/dL, or serum sodium ≤ 130 mmol/L) or liver failure (Child-Pugh score ≥ 9 and a bilirubin ≥ 3 mg/dL)9

- Patients with cirrhosis who are hospitalized for other reasons and have an ascitic protein level < 1.0 g/dL.9

Our patient has no signs or symptoms of gastrointestinal bleeding and no history of SBP. Her ascitic fluid protein level is 1.1 g/dL, and she has normal renal function. However, her Child-Pugh score is 12 (3 points for total bilirubin > 3 mg/dL, 3 points for serum albumin < 2.8 g/dL, 2 points for an INR 1.7 to 2.2, 3 points for moderate ascites, and 1 point for no encephalopathy), with a bilirubin of 17.0 mg/dL. Based on this, she is placed on antibiotic prophylaxis for SBP.

Our patient then undergoes an extensive workup for liver disease. Results of tests for toxins, autoimmune diseases, and inheritable diseases are all within normal limits. At this point, despite the patient’s reported negative alcohol history, our leading diagnosis is alcoholic hepatitis.

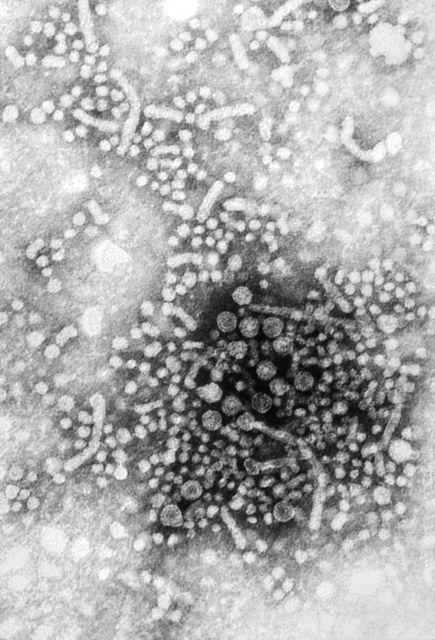

To confirm this diagnosis, she subsequently undergoes transjugular liver biopsy, considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis. During the procedure, the hepatic venous pressure gradient is measured at 18 mm Hg (reference range 1–5 mm Hg), suggestive of portal hypertension. The pathology study shows severe fatty change, active steatohepatitis with ballooning degeneration, easily identifiable Mallory-Denk bodies, and prominent neutrophilic infiltration, as well as extensive bridging fibrosis (Figure 2). These findings point to alcoholic hepatitis.

After the biopsy results, we speak with the patient further about her alcohol habits. At this point, she informs us that she has consumed significant amounts of alcohol since the age of 18 (6 to 12 alcoholic beverages per day, including beer and hard liquor). Therefore, based on this new information, on her jaundice and ascites, and on results of laboratory testing and biopsy, we confirmed our diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis.

4. When is drug treatment appropriate for alcoholic hepatitis?

- Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score greater than 12

- MELD score greater than 15

- Maddrey Discriminant Function score greater than 25

- Maddrey Discriminant Function score greater than 32

- Glasgow score greater than 5

- Glasgow score greater than 7

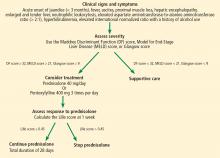

The best answer is a Maddrey Discriminant Function score greater than 32. A variety of scoring systems have been used to assess the severity of alcoholic hepatitis and to guide treatment, including the Maddrey Discriminant Function score, the MELD score, and the Glasgow score.11–16 They share similar laboratory values in their calculations, including prothrombin time (or INR) and total bilirubin.11–16 Typically, a Maddrey Discriminant Function score greater than 32, a Glasgow score of greater than 9, or a MELD score greater than 21 is used to determine whether pharmacologic treatment is indicated.11–16

The typical treatment is prednisolone or pentoxifylline.11,17–21 The Lille score is designed to help decide whether to stop corticosteroids after 1 week of administration due to lack of treatment response.22 It predicts mortality rates within 6 months; a score of 0.45 or less indicates a good prognosis, and corticosteroid therapy should continue for 28 days (Figure 3).22

Our patient’s discriminant function score is 50, her Glasgow score is 10, and her MELD score is 28; thus, she begins treatment with oral prednisolone. Her Lille score at 1 week is 0.119, indicating a good prognosis, and her corticosteroids are continued for a total of 28 days.

It should be highlighted that the most important treatment is abstinence from alcohol.11 Recent literature suggests that any benefit of prednisolone or pentoxifylline in terms of mortality rates is questionable,19–20 and there is evidence that giving both drugs simultaneously may improve mortality rates,11,21 but the evidence remains conflicting at this time.

ALCOHOLIC HEPATITIS

Alcoholic hepatitis is a clinical syndrome of jaundice and liver failure, often in the setting of heavy alcohol use for decades.11,12 The incidence is unknown, but the typical age of presentation is between 40 and 50.11,12 The chief sign is a rapid onset of jaundice (< 3 months); common signs and symptoms include fever, ascites, proximal muscle loss, and an enlarged, tender liver.12 Encephalopathy may be seen in severe alcoholic hepatitis.12

Our patient is 35 years old. She has jaundice with rapid onset, as well as ascites and a tender liver.

The diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis must take into account the patient’s history, physical examination, and laboratory findings. Until proven otherwise, the diagnosis should be presumed in the following scenario: ascites and jaundice on examination (usually with a duration < 3 months); a history of heavy alcohol use; neutrophilic leukocytosis; an AST level that is elevated but below 300 U/L; an ALT level above the normal range but below 300 U/L; an AST-ALT ratio greater than 2; a total serum bilirubin level above 5 mg/dL; and an elevated INR.11,12 Liver biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosis. Though not routinely done because of risks associated with the procedure, it may help confirm the diagnosis if it is in question.

CASE CONCLUDED

We start our patient on oral prednisolone 40 mg daily for alcoholic hepatitis. Her symptoms and laboratory testing results including bilirubin improve. Her Lille score at 7 days indicates a good prognosis, prompting continuation of corticosteroid treatment for the full 28 days.

She is referred to an outpatient alcohol rehabilitation program and has remained sober as of the last outpatient note.

Alcoholic hepatitis is extremely difficult to diagnose, and no single blood test or imaging study confirms the diagnosis. The history, physical examination findings, and laboratory findings are crucial. If the diagnosis is still in doubt, liver biopsy may help confirm the diagnosis.

- Ruyon BA; AASLD Practice Guidelines Committee. Management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis: an update. Hepatology 2009; 49(6):2087–2107. doi:10.1002/hep.22853

- Hoefs JC, Canawati HN, Sapico FL, Hopkins RR, Weiner J, Montgomerie JZ. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Hepatology 1982; 2(4):399–407. pmid:7095741

- Ginès P, Cárdenas A, Arroyo V, Rodés J. Management of cirrhosis and ascites. N Engl J Med 2004; 350(16):1646–1654. doi:10.1056/NEJMra035021

- Runyon BA, Montano AA, Akriviadis EA, Antillon MR, Irving MA, McHutchison JG. The serum-ascites albumin gradient is superior to the exudate-transudate concept in the differential diagnosis of ascites. Ann Intern Med 1992; 117(3):215–220. pmid:1616215

- Hernaez R, Hamilton JP. Unexplained ascites. Clin Liver Dis 2016; 7(3):53–56. https://aasldpubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/cld.537

- Huang LL, Xia HH, Zhu SL. Ascitic fluid analysis in the differential diagnosis of ascites: focus on cirrhotic ascites. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2014; 2(1):58–64. doi:10.14218/JCTH.2013.00010

- Bartoloni A, Zammarchi L. Clinical aspects of uncomplicated and severe malaria. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis 2012; 4(1):e2012026. doi:10.4084/MJHID.2012.026

- Titó L, Rimola A, Ginès P, Llach J, Arroyo V, Rodés J. Recurrence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhosis: frequency and predictive factors. Hepatology 1988; 8(1):27–31. pmid:3257456

- Fernández J, Ruiz del Arbol L, Gómez C, et al. Norfloxacin vs ceftriaxone in the prophylaxis of infections in patients with advanced cirrhosis and hemorrhage. Gastroenterology 2006; 131(4):1049–1056. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2006.07.010

- Runyon B; The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD). Management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis: update 2012. https://www.aasld.org/sites/default/files/guideline_documents/141020_Guideline_Ascites_4UFb_2015.pdf. Accessed September 4, 2018.

- Sidhu SS, Goyal O, Kishore H, Sidhu S. New paradigms in management of alcoholic hepatitis: a review. Hepatol Int 2017; 11(3):255–267. doi:10.1007/s12072-017-9790-5

- Lucey MR, Mathurin P, Morgan TR. Alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med 2009; 360(26):2758–2769. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0805786

- Maddrey WC, Boitnott JK, Bedine MS, Weber FL Jr, Mezey E, White RI Jr. Corticosteroid therapy of alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology 1978; 75(2):193–199. pmid:352788

- Forrest EH, Evans CD, Stewart S, et al. Analysis of factors predictive of mortality in alcoholic hepatitis and derivation and validation of the Glasgow alcoholic hepatitis score. Gut 2005; 54(8):1174–1179. doi:10.1136/gut.2004.050781

- Dunn W, Jamil LH, Brown LS, et al. MELD accurately predicts mortality in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology 2005; 41(2):353–358. doi:10.1002/hep.20503

- Sheth M, Riggs M, Patel T. Utility of the Mayo end-stage liver disease (MELD) score in assessing prognosis of patients with alcoholic hepatitis. BMC Gastroenterol 2002; 2:2. pmid:11835693

- Akriviadis E, Botla R, Briggs W, Han S, Reynolds T, Shakil O. Pentoxifylline improves short-term survival in severe acute alcoholic hepatitis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2000; 119(6):1637–1648. pmid:11113085

- Mathurin P, O’Grady J, Carithers RL, et al. Corticosteroids improve short-term survival in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis: meta-analysis of individual patient data. Gut 2011; 60(2):255–260. doi:10.1136/gut.2010.224097

- Thursz MR, Richardson P, Allison M, et al; STOPAH Trial. Prednisolone or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med 2015; 372(17):1619–1628. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1412278

- Thursz M, Forrest E, Roderick P, et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of steroids or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis (STOPAH): a 2 × 2 factorial randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Assess 2015; 19(102):1–104. doi:10.3310/hta191020

- Lee YS, Kim HJ, Kim JH, et al. Treatment of severe alcoholic hepatitis with corticosteroid, pentoxifylline, or dual therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2017; 51(4):364–377. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000000674

- Louvet A, Naveau S, Abdelnour M, et al. The Lille model: a new tool for therapeutic strategy in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis treated with steroids. Hepatology 2007; 45(6):1348–1354. doi:10.1002/hep.21607

A 35-year-old woman is admitted to the hospital with a 5-day history of abdominal distention and jaundice. She reports no history of fever, chills, night sweats, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, changes in urine color, change in stool color, weight loss, weight gain, or loss of appetite.

She is petite, with a body mass index of 19.4 kg/m2. She has no known history of medical conditions or surgery and is not taking any medications. Her family history is unremarkable, and she denies current or past tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use.

RECENT TRAVEL

She says that during a trip to Central America several months ago, she had suffered a seizure and was taken to a local hospital, where laboratory testing revealed elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels. She says that the rest of the workup at that time was normal.

About 1 week after that incident, she returned home and saw her primary care physician, who ordered further testing, which showed mild hyperbilirubinemia and mild elevation of AST and ALT levels. Her physician attributed the elevations to atovaquone, which she had been taking for malaria prophylaxis, as repeat testing 2 weeks later showed improvement in AST and ALT levels.

The patient says she returned to her normal state of health until about 5 days ago, when she noticed jaundice and abdominal distention, but without abdominal pain, dark urine, or clay-colored stools. She became concerned and went to her local hospital. Testing there noted mild elevation of AST and ALT, as well as an elevated international normalized ratio (INR) and hyperbilirubinemia. Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis showed hepatomegaly with possible fatty liver. Because of these results, the patient was transferred to our institution for further evaluation.

EVALUATION AT OUR INSTITUTION

On examination at our institution, she is afebrile, and vital signs are within normal ranges. She has bilateral scleral icterus and diffuse jaundice, but no other skin finding such as rash or spider angioma. She has no lymphadenopathy. Her abdomen is distended, with tense ascites, and her liver is tender to palpation. The tip of the spleen is not palpable.

The cardiovascular examination reveals no murmurs, rubs, or gallops, but she has jugular venous distention and +2 pitting edema of both lower extremities.

On respiratory examination, there is dullness to percussion, with slight crackles on auscultation at the right lung base. The neurologic examination is normal.

Table 1 shows the results of initial laboratory testing.

1. Which study would provide the most information on the cause of ascites?

- Abdominal ultrasonography

- Abdominal paracentesis with ascitic fluid analysis

- Chest radiography

- Echocardiography

- Urine protein-to-creatinine ratio

Abdominal paracentesis with ascitic fluid analysis is the essential study for any patient with clinically apparent new-onset ascites.1–3 It is the study that provides the most information on the cause of ascites.

In our patient, abdominal paracentesis yields 1,000 mL of straw-colored ascitic fluid, and analysis shows 86 nucleated cells, 28 of which are polymorphonuclear cells, and 0 red blood cells, with negative Gram stain and culture. The ascitic albumin level is 0.85 g/dL, with an ascitic protein of 1.1 g/dL.

Abdominal ultrasonography shows a diffusely echogenic liver, no focal lesions, moderate ascites, normal portal vein flow, no intrahepatic or extrahepatic biliary duct dilation, normal kidney sizes, no hydronephrosis, and no intra-abdominal mass. Chest radiography is clear with no sign of consolidation, edema, or effusion. Echocardiography shows a normal left ventricular ejection fraction with no valvular disease or pericardial effusion. A random urine protein-creatinine ratio is normal at 0.1 (reference range < 0.2).

2. What is the most likely cause of her ascites based on the workup to this point?

- Cirrhosis

- Heart failure

- Nephrotic syndrome

- Portal vein thrombus

- Abdominal malignancy

- Malaria

An initial approach to ascitic fluid analysis is to calculate the serum-ascites albumin gradient (SAAG). The SAAG is calculated as the serum albumin level minus the ascitic fluid albumin level.4,5 This is useful in determining the cause of the ascites (Figure 1).4,5 A gradient of 1.1 g/dL or higher indicates portal hypertension.4,5

Common causes of portal hypertension include cirrhosis, alcoholic hepatitis, heart failure, vascular occlusion syndromes (eg, Budd-Chiari syndrome, portal vein thrombosis), idiopathic portal fibrosis, and metastatic liver disease.5,6

If portal hypertension is present based on the SAAG, the next step is to review the ascitic protein level to help distinguish between a hepatic and a cardiac etiology of the ascites. An ascitic protein level less than 2.5 g/dL indicates a primary liver pathology (eg, cirrhosis). An ascitic protein level of 2.5 g/dL or greater typically indicates a cardiac condition (eg, heart failure, pericardial disease) with secondary congestive hepatopathy.5,6

If the SAAG is less than 1.1 g/dL, the ascites is likely not from portal hypertension. Typical causes of a low SAAG include infection, malignancy, pancreatic ascites, and nephrotic syndrome.5,6

In our patient, the SAAG is 1.35 g/dL (2.2 g/dL minus 0.85 g/dL), ie, elevated and due to portal hypertension. With an SAAG of 1.1 g/dL or greater and an ascitic fluid protein level less than 2.5 g/dL, as in our patient, the most likely cause is cirrhosis.

Heart failure is unlikely based on her normal brain natriuretic peptide level, an ascitic fluid protein level below 2.5 g/dL, and normal results on echocardiography. Nephrotic syndrome is also very unlikely based on the patient’s normal random urine protein-creatinine ratio. Portal vein thrombus and abdominal malignancy are essentially ruled out by the negative results of Doppler abdominal ultrasonography, with normal venous flow and no intra-abdominal mass and coupled with an elevated SAAG.

Although the patient has a history of travel, the incubation period for malaria would not fit the time frame of presentation. Also, she did not have typical malarial symptoms, her rapid malaria test was negative, and a peripheral blood smear for blood parasites was negative. It should be noted, however, that Plasmodium malariae infection classically presents with flulike symptoms and can resemble nephrotic syndrome, including peripheral edema, ascites, heavy proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, and hyperlipidemia.7

3. In which patients is antibiotic prophylaxis against spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) appropriate?

- Any patient with cirrhosis

- Any patient with cirrhosis who is hospitalized

- Any patient with cirrhosis and an ascitic fluid protein level below 2.0 g/dL

- Any patient with cirrhosis and a history of SBP

Any patient with cirrhosis and a history of SBP should receive prophylactic antibiotics,8 as should any patient deemed at high risk of SBP. It is indicated in the following patients:

- Patients with cirrhosis and gastrointestinal bleeding9,10

- Patients with cirrhosis and a previous episode of SBP8

- Patients with cirrhosis and an ascitic fluid protein level less than 1.5 g/dL with either impaired renal function (creatinine ≥ 1.2 mg/dL, blood urea nitrogen level ≥ 25 mg/dL, or serum sodium ≤ 130 mmol/L) or liver failure (Child-Pugh score ≥ 9 and a bilirubin ≥ 3 mg/dL)9

- Patients with cirrhosis who are hospitalized for other reasons and have an ascitic protein level < 1.0 g/dL.9

Our patient has no signs or symptoms of gastrointestinal bleeding and no history of SBP. Her ascitic fluid protein level is 1.1 g/dL, and she has normal renal function. However, her Child-Pugh score is 12 (3 points for total bilirubin > 3 mg/dL, 3 points for serum albumin < 2.8 g/dL, 2 points for an INR 1.7 to 2.2, 3 points for moderate ascites, and 1 point for no encephalopathy), with a bilirubin of 17.0 mg/dL. Based on this, she is placed on antibiotic prophylaxis for SBP.

Our patient then undergoes an extensive workup for liver disease. Results of tests for toxins, autoimmune diseases, and inheritable diseases are all within normal limits. At this point, despite the patient’s reported negative alcohol history, our leading diagnosis is alcoholic hepatitis.

To confirm this diagnosis, she subsequently undergoes transjugular liver biopsy, considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis. During the procedure, the hepatic venous pressure gradient is measured at 18 mm Hg (reference range 1–5 mm Hg), suggestive of portal hypertension. The pathology study shows severe fatty change, active steatohepatitis with ballooning degeneration, easily identifiable Mallory-Denk bodies, and prominent neutrophilic infiltration, as well as extensive bridging fibrosis (Figure 2). These findings point to alcoholic hepatitis.

After the biopsy results, we speak with the patient further about her alcohol habits. At this point, she informs us that she has consumed significant amounts of alcohol since the age of 18 (6 to 12 alcoholic beverages per day, including beer and hard liquor). Therefore, based on this new information, on her jaundice and ascites, and on results of laboratory testing and biopsy, we confirmed our diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis.

4. When is drug treatment appropriate for alcoholic hepatitis?

- Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score greater than 12

- MELD score greater than 15

- Maddrey Discriminant Function score greater than 25

- Maddrey Discriminant Function score greater than 32

- Glasgow score greater than 5

- Glasgow score greater than 7

The best answer is a Maddrey Discriminant Function score greater than 32. A variety of scoring systems have been used to assess the severity of alcoholic hepatitis and to guide treatment, including the Maddrey Discriminant Function score, the MELD score, and the Glasgow score.11–16 They share similar laboratory values in their calculations, including prothrombin time (or INR) and total bilirubin.11–16 Typically, a Maddrey Discriminant Function score greater than 32, a Glasgow score of greater than 9, or a MELD score greater than 21 is used to determine whether pharmacologic treatment is indicated.11–16

The typical treatment is prednisolone or pentoxifylline.11,17–21 The Lille score is designed to help decide whether to stop corticosteroids after 1 week of administration due to lack of treatment response.22 It predicts mortality rates within 6 months; a score of 0.45 or less indicates a good prognosis, and corticosteroid therapy should continue for 28 days (Figure 3).22

Our patient’s discriminant function score is 50, her Glasgow score is 10, and her MELD score is 28; thus, she begins treatment with oral prednisolone. Her Lille score at 1 week is 0.119, indicating a good prognosis, and her corticosteroids are continued for a total of 28 days.

It should be highlighted that the most important treatment is abstinence from alcohol.11 Recent literature suggests that any benefit of prednisolone or pentoxifylline in terms of mortality rates is questionable,19–20 and there is evidence that giving both drugs simultaneously may improve mortality rates,11,21 but the evidence remains conflicting at this time.

ALCOHOLIC HEPATITIS

Alcoholic hepatitis is a clinical syndrome of jaundice and liver failure, often in the setting of heavy alcohol use for decades.11,12 The incidence is unknown, but the typical age of presentation is between 40 and 50.11,12 The chief sign is a rapid onset of jaundice (< 3 months); common signs and symptoms include fever, ascites, proximal muscle loss, and an enlarged, tender liver.12 Encephalopathy may be seen in severe alcoholic hepatitis.12

Our patient is 35 years old. She has jaundice with rapid onset, as well as ascites and a tender liver.

The diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis must take into account the patient’s history, physical examination, and laboratory findings. Until proven otherwise, the diagnosis should be presumed in the following scenario: ascites and jaundice on examination (usually with a duration < 3 months); a history of heavy alcohol use; neutrophilic leukocytosis; an AST level that is elevated but below 300 U/L; an ALT level above the normal range but below 300 U/L; an AST-ALT ratio greater than 2; a total serum bilirubin level above 5 mg/dL; and an elevated INR.11,12 Liver biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosis. Though not routinely done because of risks associated with the procedure, it may help confirm the diagnosis if it is in question.

CASE CONCLUDED

We start our patient on oral prednisolone 40 mg daily for alcoholic hepatitis. Her symptoms and laboratory testing results including bilirubin improve. Her Lille score at 7 days indicates a good prognosis, prompting continuation of corticosteroid treatment for the full 28 days.