User login

DDNA19: The NASH conundrum

Zobair Younossi, MD, MPH, chairman of the department of medicine at Inova Fairfax (Va.) Medical Campus, discusses the progressive form of NAFLD -- NASH -- and its optimal treatment.

Zobair Younossi, MD, MPH, chairman of the department of medicine at Inova Fairfax (Va.) Medical Campus, discusses the progressive form of NAFLD -- NASH -- and its optimal treatment.

Zobair Younossi, MD, MPH, chairman of the department of medicine at Inova Fairfax (Va.) Medical Campus, discusses the progressive form of NAFLD -- NASH -- and its optimal treatment.

AT DIGESTIVE DISEASES: NEW ADVANCES 2019

Cirrhosis model predicts decompensation across diverse populations

A prognostic model that uses serum albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) and Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) scores can identify patients with cirrhosis who are at high risk of liver decompensation, according to investigators.

During validation testing, the scoring system performed well among European and Middle Eastern patients, which supports prognostic value across diverse populations, reported lead author Neil Guha, MRCP, PhD, of the University of Nottingham (U.K.) and his colleagues, who suggested that the scoring system could fix an important practice gap.

“Identification of patients [with chronic liver disease] that need intensive monitoring and timely intervention is challenging,” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “Robust prognostic tools using simple laboratory variables, with potential for implementation in nonspecialist settings and across different health care systems, have significant appeal.”

Although existing scoring systems have been used for decades, they have clear limitations, the investigators noted, referring to predictive ability that may be too little, too late.

“[T]hese scoring systems provide value after synthetic liver function has become significantly deranged and provide only short-term prognostic value,” the investigators wrote. “Presently, there are no scores, performed in routine clinical practice, that provide robust prognostic stratification within early, compensated cirrhosis over the medium/long term.”

To fulfill this need, the investigators developed and validated a prognostic model that incorporates data from the ALBI and FIB-4 scoring systems because these tests measure both fibrosis and function. The development phase involved 145 patients with compensated cirrhosis from Nottingham. Almost half of the cohort had liver disease because of alcohol (44.8%), while about one out of three patients had nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (29.7%). After investigators collected baseline clinical features and scores, patients were followed for a median of 4.59 years, during which time decompensation events were recorded (ascites, variceal bleeding, and encephalopathy). Decompensation occurred in about one out of five patients (19.3%) in the U.K. group, with ascites being the most common (71.4%). Using these findings, the investigators created the prognostic model, which classified patients as having either low or high risk of decompensation. In the development cohort, patients with high risk scores had a hazard ratio for decompensation of 7.10.

In the second part of the study, the investigators validated their model with two clinically distinct groups in Dublin, Ireland (prospective; n = 141), and Menoufia, Egypt (retrospective; n = 93).

In the Dublin cohort, the most common etiologies were alcohol (39.7%) and hepatitis C (29.8%). Over a maximum observational period of 6.4 years, the decompensation rate was lower than the development group, at 12.1%. Types of decompensation also differed, with variceal bleeding being the most common (47.1%). Patients with high risk scores had a higher HR for decompensation than the U.K. cohort, at 12.54.

In the Egypt group, the most common causes of liver disease were nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (47.3%) and hepatitis C (34.4%). The maximum follow-up period was 10.6 years, during which time 38.7% of patients experienced decompensation, with ascites being the most common form (57.1%). The HR of 5.10 was the lowest of all cohorts.

The investigators noted that the cohorts represented unique patient populations with different etiological patterns. “This provides reassurance that the model has generalizability for stratifying liver disease at an international level,” the investigators wrote, suggesting that ALBI and FIB-4 can be used in low-resource and community settings.

“A frequently leveled criticism of algorithms such as ALBI-FIB-4 is that they are too complicated to be applied routinely in the clinical setting,” the investigators wrote. “To overcome this problem we developed a simple online calculator which can be accessed using the following link: https://jscalc.io/calc/gdEJj89Wz5PirkSL.”

“We have shown that routinely available laboratory variables, combined in a novel algorithm, ALBI-FIB-4, can stratify patients with cirrhosis for future risk of liver decompensation,” the investigators concluded. “The ability to do this in the context of early, compensated cirrhosis with preserved liver synthetic function whilst also predicting long-term clinical outcomes has clinical utility for international health care systems.”

The study was funded by National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Nottingham Digestive Diseases Biomedical Research Centre based at Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust and the University of Nottingham. The investigators declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Guha N et al. CGH. 2019 Feb 1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.01.042.

A prognostic model that uses serum albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) and Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) scores can identify patients with cirrhosis who are at high risk of liver decompensation, according to investigators.

During validation testing, the scoring system performed well among European and Middle Eastern patients, which supports prognostic value across diverse populations, reported lead author Neil Guha, MRCP, PhD, of the University of Nottingham (U.K.) and his colleagues, who suggested that the scoring system could fix an important practice gap.

“Identification of patients [with chronic liver disease] that need intensive monitoring and timely intervention is challenging,” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “Robust prognostic tools using simple laboratory variables, with potential for implementation in nonspecialist settings and across different health care systems, have significant appeal.”

Although existing scoring systems have been used for decades, they have clear limitations, the investigators noted, referring to predictive ability that may be too little, too late.

“[T]hese scoring systems provide value after synthetic liver function has become significantly deranged and provide only short-term prognostic value,” the investigators wrote. “Presently, there are no scores, performed in routine clinical practice, that provide robust prognostic stratification within early, compensated cirrhosis over the medium/long term.”

To fulfill this need, the investigators developed and validated a prognostic model that incorporates data from the ALBI and FIB-4 scoring systems because these tests measure both fibrosis and function. The development phase involved 145 patients with compensated cirrhosis from Nottingham. Almost half of the cohort had liver disease because of alcohol (44.8%), while about one out of three patients had nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (29.7%). After investigators collected baseline clinical features and scores, patients were followed for a median of 4.59 years, during which time decompensation events were recorded (ascites, variceal bleeding, and encephalopathy). Decompensation occurred in about one out of five patients (19.3%) in the U.K. group, with ascites being the most common (71.4%). Using these findings, the investigators created the prognostic model, which classified patients as having either low or high risk of decompensation. In the development cohort, patients with high risk scores had a hazard ratio for decompensation of 7.10.

In the second part of the study, the investigators validated their model with two clinically distinct groups in Dublin, Ireland (prospective; n = 141), and Menoufia, Egypt (retrospective; n = 93).

In the Dublin cohort, the most common etiologies were alcohol (39.7%) and hepatitis C (29.8%). Over a maximum observational period of 6.4 years, the decompensation rate was lower than the development group, at 12.1%. Types of decompensation also differed, with variceal bleeding being the most common (47.1%). Patients with high risk scores had a higher HR for decompensation than the U.K. cohort, at 12.54.

In the Egypt group, the most common causes of liver disease were nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (47.3%) and hepatitis C (34.4%). The maximum follow-up period was 10.6 years, during which time 38.7% of patients experienced decompensation, with ascites being the most common form (57.1%). The HR of 5.10 was the lowest of all cohorts.

The investigators noted that the cohorts represented unique patient populations with different etiological patterns. “This provides reassurance that the model has generalizability for stratifying liver disease at an international level,” the investigators wrote, suggesting that ALBI and FIB-4 can be used in low-resource and community settings.

“A frequently leveled criticism of algorithms such as ALBI-FIB-4 is that they are too complicated to be applied routinely in the clinical setting,” the investigators wrote. “To overcome this problem we developed a simple online calculator which can be accessed using the following link: https://jscalc.io/calc/gdEJj89Wz5PirkSL.”

“We have shown that routinely available laboratory variables, combined in a novel algorithm, ALBI-FIB-4, can stratify patients with cirrhosis for future risk of liver decompensation,” the investigators concluded. “The ability to do this in the context of early, compensated cirrhosis with preserved liver synthetic function whilst also predicting long-term clinical outcomes has clinical utility for international health care systems.”

The study was funded by National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Nottingham Digestive Diseases Biomedical Research Centre based at Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust and the University of Nottingham. The investigators declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Guha N et al. CGH. 2019 Feb 1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.01.042.

A prognostic model that uses serum albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) and Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) scores can identify patients with cirrhosis who are at high risk of liver decompensation, according to investigators.

During validation testing, the scoring system performed well among European and Middle Eastern patients, which supports prognostic value across diverse populations, reported lead author Neil Guha, MRCP, PhD, of the University of Nottingham (U.K.) and his colleagues, who suggested that the scoring system could fix an important practice gap.

“Identification of patients [with chronic liver disease] that need intensive monitoring and timely intervention is challenging,” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. “Robust prognostic tools using simple laboratory variables, with potential for implementation in nonspecialist settings and across different health care systems, have significant appeal.”

Although existing scoring systems have been used for decades, they have clear limitations, the investigators noted, referring to predictive ability that may be too little, too late.

“[T]hese scoring systems provide value after synthetic liver function has become significantly deranged and provide only short-term prognostic value,” the investigators wrote. “Presently, there are no scores, performed in routine clinical practice, that provide robust prognostic stratification within early, compensated cirrhosis over the medium/long term.”

To fulfill this need, the investigators developed and validated a prognostic model that incorporates data from the ALBI and FIB-4 scoring systems because these tests measure both fibrosis and function. The development phase involved 145 patients with compensated cirrhosis from Nottingham. Almost half of the cohort had liver disease because of alcohol (44.8%), while about one out of three patients had nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (29.7%). After investigators collected baseline clinical features and scores, patients were followed for a median of 4.59 years, during which time decompensation events were recorded (ascites, variceal bleeding, and encephalopathy). Decompensation occurred in about one out of five patients (19.3%) in the U.K. group, with ascites being the most common (71.4%). Using these findings, the investigators created the prognostic model, which classified patients as having either low or high risk of decompensation. In the development cohort, patients with high risk scores had a hazard ratio for decompensation of 7.10.

In the second part of the study, the investigators validated their model with two clinically distinct groups in Dublin, Ireland (prospective; n = 141), and Menoufia, Egypt (retrospective; n = 93).

In the Dublin cohort, the most common etiologies were alcohol (39.7%) and hepatitis C (29.8%). Over a maximum observational period of 6.4 years, the decompensation rate was lower than the development group, at 12.1%. Types of decompensation also differed, with variceal bleeding being the most common (47.1%). Patients with high risk scores had a higher HR for decompensation than the U.K. cohort, at 12.54.

In the Egypt group, the most common causes of liver disease were nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (47.3%) and hepatitis C (34.4%). The maximum follow-up period was 10.6 years, during which time 38.7% of patients experienced decompensation, with ascites being the most common form (57.1%). The HR of 5.10 was the lowest of all cohorts.

The investigators noted that the cohorts represented unique patient populations with different etiological patterns. “This provides reassurance that the model has generalizability for stratifying liver disease at an international level,” the investigators wrote, suggesting that ALBI and FIB-4 can be used in low-resource and community settings.

“A frequently leveled criticism of algorithms such as ALBI-FIB-4 is that they are too complicated to be applied routinely in the clinical setting,” the investigators wrote. “To overcome this problem we developed a simple online calculator which can be accessed using the following link: https://jscalc.io/calc/gdEJj89Wz5PirkSL.”

“We have shown that routinely available laboratory variables, combined in a novel algorithm, ALBI-FIB-4, can stratify patients with cirrhosis for future risk of liver decompensation,” the investigators concluded. “The ability to do this in the context of early, compensated cirrhosis with preserved liver synthetic function whilst also predicting long-term clinical outcomes has clinical utility for international health care systems.”

The study was funded by National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Nottingham Digestive Diseases Biomedical Research Centre based at Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust and the University of Nottingham. The investigators declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Guha N et al. CGH. 2019 Feb 1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.01.042.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Will inpatient albumin help in decompensated cirrhosis?

PHILADELPHIA – , according to Vijay Shah, MD, chair of the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

“These are interesting studies, but I don’t think we’re ready yet to use this broadly,” Dr. Shah said at the meeting jointly provided by Rutgers and Global Academy for Medical Education.

Current guidelines do describe the use of albumin for large-volume paracentesis and other specific inpatient situations; however, extrapolating its long-term use has been explored in two major studies that recently came out with contradictory findings.

In the ANSWER trial, as reported in the Lancet, investigators at 33 centers randomized patients with cirrhosis and uncomplicated ascites to either standard medical treatment with or without human albumin, at 40 g twice weekly for 2 weeks, followed by 40 g weekly for up to 18 months.

Those investigators found that long-term albumin prolonged overall survival, with a 38% reduction in the mortality hazard ratio, with similar rates of serious, nonliver adverse events, leading them to conclude that this intervention may act as a disease-modifying treatment in decompensated cirrhosis patients.

By contrast, however, a recent randomized, placebo-controlled trial reported in the Journal of Hepatology showed that albumin plus midodrine, an alpha-adrenergic vasoconstrictor, did not improve survival among patients with decompensated cirrhosis on the liver transplant waiting list, at least at the doses administered (midodrine 15-30 mg/day and albumin 40 g every 15 days for a year).

While this particular combination of albumin plus midodrine did decrease renin and aldosterone levels, the intervention did not prevent complications or improve survival, investigators said at the time. Complication rates were 37% and 43% for treatment and placebo, respectively (P = .402), with low rates of death in both groups and no significant difference in mortality at 1 year (P = .527).

Dr. Shah said the discrepant results may be attributable to specific differences in study design or enrollment.

“It’s just hand waving, but it may be related to the dose of albumin, or may be related to the types of patients – the second study was in patients who are waiting for liver transplantation,” he told attendees. “But I don’t think that there’s currently enough evidence to use albumin in your patients in the outpatient setting.”

There is a third study, recently published in the American Journal of Gastroenterology, looking at data for a large end-stage liver disease cohort with hyponatremia. Investigators observed a higher rate of hyponatremia resolution and improved 30-day survival in those who had received albumin (total mean amount, 225 g) versus those who had not.

Considering all of this evidence taken together, Dr. Shah said he would not favor using outpatient albumin at this point – though he advised attendees to watch for a currently recruiting phase 3 randomized study, known as PRECIOSA, which is evaluating long-term administration of human albumin 20% injectable solution, dosed by body weight, in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites.

Dr. Shah indicated that he is a consultant for Afimmune, Durect Corporation, Enterome, GRI Bio, Merck Research Laboratories, Novartis Pharma, and Vital Therapeutics. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

PHILADELPHIA – , according to Vijay Shah, MD, chair of the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

“These are interesting studies, but I don’t think we’re ready yet to use this broadly,” Dr. Shah said at the meeting jointly provided by Rutgers and Global Academy for Medical Education.

Current guidelines do describe the use of albumin for large-volume paracentesis and other specific inpatient situations; however, extrapolating its long-term use has been explored in two major studies that recently came out with contradictory findings.

In the ANSWER trial, as reported in the Lancet, investigators at 33 centers randomized patients with cirrhosis and uncomplicated ascites to either standard medical treatment with or without human albumin, at 40 g twice weekly for 2 weeks, followed by 40 g weekly for up to 18 months.

Those investigators found that long-term albumin prolonged overall survival, with a 38% reduction in the mortality hazard ratio, with similar rates of serious, nonliver adverse events, leading them to conclude that this intervention may act as a disease-modifying treatment in decompensated cirrhosis patients.

By contrast, however, a recent randomized, placebo-controlled trial reported in the Journal of Hepatology showed that albumin plus midodrine, an alpha-adrenergic vasoconstrictor, did not improve survival among patients with decompensated cirrhosis on the liver transplant waiting list, at least at the doses administered (midodrine 15-30 mg/day and albumin 40 g every 15 days for a year).

While this particular combination of albumin plus midodrine did decrease renin and aldosterone levels, the intervention did not prevent complications or improve survival, investigators said at the time. Complication rates were 37% and 43% for treatment and placebo, respectively (P = .402), with low rates of death in both groups and no significant difference in mortality at 1 year (P = .527).

Dr. Shah said the discrepant results may be attributable to specific differences in study design or enrollment.

“It’s just hand waving, but it may be related to the dose of albumin, or may be related to the types of patients – the second study was in patients who are waiting for liver transplantation,” he told attendees. “But I don’t think that there’s currently enough evidence to use albumin in your patients in the outpatient setting.”

There is a third study, recently published in the American Journal of Gastroenterology, looking at data for a large end-stage liver disease cohort with hyponatremia. Investigators observed a higher rate of hyponatremia resolution and improved 30-day survival in those who had received albumin (total mean amount, 225 g) versus those who had not.

Considering all of this evidence taken together, Dr. Shah said he would not favor using outpatient albumin at this point – though he advised attendees to watch for a currently recruiting phase 3 randomized study, known as PRECIOSA, which is evaluating long-term administration of human albumin 20% injectable solution, dosed by body weight, in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites.

Dr. Shah indicated that he is a consultant for Afimmune, Durect Corporation, Enterome, GRI Bio, Merck Research Laboratories, Novartis Pharma, and Vital Therapeutics. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

PHILADELPHIA – , according to Vijay Shah, MD, chair of the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

“These are interesting studies, but I don’t think we’re ready yet to use this broadly,” Dr. Shah said at the meeting jointly provided by Rutgers and Global Academy for Medical Education.

Current guidelines do describe the use of albumin for large-volume paracentesis and other specific inpatient situations; however, extrapolating its long-term use has been explored in two major studies that recently came out with contradictory findings.

In the ANSWER trial, as reported in the Lancet, investigators at 33 centers randomized patients with cirrhosis and uncomplicated ascites to either standard medical treatment with or without human albumin, at 40 g twice weekly for 2 weeks, followed by 40 g weekly for up to 18 months.

Those investigators found that long-term albumin prolonged overall survival, with a 38% reduction in the mortality hazard ratio, with similar rates of serious, nonliver adverse events, leading them to conclude that this intervention may act as a disease-modifying treatment in decompensated cirrhosis patients.

By contrast, however, a recent randomized, placebo-controlled trial reported in the Journal of Hepatology showed that albumin plus midodrine, an alpha-adrenergic vasoconstrictor, did not improve survival among patients with decompensated cirrhosis on the liver transplant waiting list, at least at the doses administered (midodrine 15-30 mg/day and albumin 40 g every 15 days for a year).

While this particular combination of albumin plus midodrine did decrease renin and aldosterone levels, the intervention did not prevent complications or improve survival, investigators said at the time. Complication rates were 37% and 43% for treatment and placebo, respectively (P = .402), with low rates of death in both groups and no significant difference in mortality at 1 year (P = .527).

Dr. Shah said the discrepant results may be attributable to specific differences in study design or enrollment.

“It’s just hand waving, but it may be related to the dose of albumin, or may be related to the types of patients – the second study was in patients who are waiting for liver transplantation,” he told attendees. “But I don’t think that there’s currently enough evidence to use albumin in your patients in the outpatient setting.”

There is a third study, recently published in the American Journal of Gastroenterology, looking at data for a large end-stage liver disease cohort with hyponatremia. Investigators observed a higher rate of hyponatremia resolution and improved 30-day survival in those who had received albumin (total mean amount, 225 g) versus those who had not.

Considering all of this evidence taken together, Dr. Shah said he would not favor using outpatient albumin at this point – though he advised attendees to watch for a currently recruiting phase 3 randomized study, known as PRECIOSA, which is evaluating long-term administration of human albumin 20% injectable solution, dosed by body weight, in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and ascites.

Dr. Shah indicated that he is a consultant for Afimmune, Durect Corporation, Enterome, GRI Bio, Merck Research Laboratories, Novartis Pharma, and Vital Therapeutics. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

REPORTING FROM DIGESTIVE DISEASES: NEW ADVANCES

DDNA19: Cardiac Complications in Liver Disease Patients

Dr. Marc Klapholz of Rutgers University, Newark, N.J., explains the latest developments in portopulmonary arterial hypertension, hepatopulmonary syndrome, and cirrhotic cardiomyopathy, as well as the emerging field and association between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Marc Klapholz of Rutgers University, Newark, N.J., explains the latest developments in portopulmonary arterial hypertension, hepatopulmonary syndrome, and cirrhotic cardiomyopathy, as well as the emerging field and association between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Marc Klapholz of Rutgers University, Newark, N.J., explains the latest developments in portopulmonary arterial hypertension, hepatopulmonary syndrome, and cirrhotic cardiomyopathy, as well as the emerging field and association between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular disease.

AT DIGESTIVE DISEASES: NEW ADVANCES

One-time, universal hepatitis C testing cost effective, researchers say

Universal one-time screening for hepatitis C virus infection is cost effective, compared with birth cohort screening alone, according to the results of a study published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommend testing all individuals born between 1945 and 1965 in addition to injection drug users and other high-risk individuals. But so-called birth cohort screening does not reflect the recent spike in hepatitis C virus (HCV) cases among younger persons in the United States, nor the current recommendation to treat nearly all chronic HCV cases, wrote Mark H. Eckman, MD, of the University of Cincinnati, and his associates.

Using a computer program called Decision Maker, they modeled the cost-effectiveness of universal one-time testing, birth cohort screening, and no screening based on quality-adjusted life-years (QALYS) and 2017 U.S. dollars. They assumed that all HCV-infected patients were treatment naive, treatment eligible, and asymptomatic (for example, had no decompensated cirrhosis). They used efficacy data from the ASTRAL trials of sofosbuvir-velpatasvir as well as the ENDURANCE, SURVEYOR, and EXPEDITION trials of glecaprevir-pibrentasvir. In the model, patients who did not achieve a sustained viral response to treatment went on to complete a 12-week triple direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimen (sofosbuvir, velpatasvir, and voxilaprevir).

Based on these assumptions, universal one-time screening and treatment of infected individuals cost less than $50,000 per QALY gained, making it highly cost effective, compared with no screening, the investigators wrote. Universal screening also was highly cost effective when compared with birth cohort screening, costing $11,378 for each QALY gained.

“Analyses performed during the era of first-generation DAAs and interferon-based treatment regimens found birth-cohort screening to be ‘cost effective,’ ” the researchers wrote. “However, the availability of a new generation of highly effective, non–interferon-based oral regimens, with fewer side effects and shorter treatment courses, has altered the dynamic around the question of screening.” They pointed to another recent study in which universal one-time HCV testing was more cost effective than birth cohort screening.

Such findings have spurred experts to revisit guidelines on HCV screening, but universal testing is controversial when some states, counties, and communities have a low HCV prevalence. In the model, universal one-time HCV screening was cost effective (less than $50,000 per QALY gained), compared with birth cohort screening as long as prevalence exceeded 0.07% among adults not born between 1945 and 1965. The current prevalence estimate in this group is 0.29%, which is probably low because it does not account for the rising incidence among younger adults, the researchers wrote. In an ideal world, all clinics and hospitals would implement an HCV testing program, but in the real world of scarce resources, “data regarding the cost-effectiveness threshold can guide local policy decisions by directing testing services to settings in which they generate sufficient benefit for the cost.”

Partial funding came from the National Foundation for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC Foundation), with funding provided through multiple donors to the CDC Foundation’s Viral Hepatitis Action Coalition. Dr. Eckman reported grant support from Merck and one coinvestigator reported ties to AbbVie, Gilead, Merck, and several other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Eckman MH et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Sep 7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.08.080.

Universal one-time screening for hepatitis C virus infection is cost effective, compared with birth cohort screening alone, according to the results of a study published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommend testing all individuals born between 1945 and 1965 in addition to injection drug users and other high-risk individuals. But so-called birth cohort screening does not reflect the recent spike in hepatitis C virus (HCV) cases among younger persons in the United States, nor the current recommendation to treat nearly all chronic HCV cases, wrote Mark H. Eckman, MD, of the University of Cincinnati, and his associates.

Using a computer program called Decision Maker, they modeled the cost-effectiveness of universal one-time testing, birth cohort screening, and no screening based on quality-adjusted life-years (QALYS) and 2017 U.S. dollars. They assumed that all HCV-infected patients were treatment naive, treatment eligible, and asymptomatic (for example, had no decompensated cirrhosis). They used efficacy data from the ASTRAL trials of sofosbuvir-velpatasvir as well as the ENDURANCE, SURVEYOR, and EXPEDITION trials of glecaprevir-pibrentasvir. In the model, patients who did not achieve a sustained viral response to treatment went on to complete a 12-week triple direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimen (sofosbuvir, velpatasvir, and voxilaprevir).

Based on these assumptions, universal one-time screening and treatment of infected individuals cost less than $50,000 per QALY gained, making it highly cost effective, compared with no screening, the investigators wrote. Universal screening also was highly cost effective when compared with birth cohort screening, costing $11,378 for each QALY gained.

“Analyses performed during the era of first-generation DAAs and interferon-based treatment regimens found birth-cohort screening to be ‘cost effective,’ ” the researchers wrote. “However, the availability of a new generation of highly effective, non–interferon-based oral regimens, with fewer side effects and shorter treatment courses, has altered the dynamic around the question of screening.” They pointed to another recent study in which universal one-time HCV testing was more cost effective than birth cohort screening.

Such findings have spurred experts to revisit guidelines on HCV screening, but universal testing is controversial when some states, counties, and communities have a low HCV prevalence. In the model, universal one-time HCV screening was cost effective (less than $50,000 per QALY gained), compared with birth cohort screening as long as prevalence exceeded 0.07% among adults not born between 1945 and 1965. The current prevalence estimate in this group is 0.29%, which is probably low because it does not account for the rising incidence among younger adults, the researchers wrote. In an ideal world, all clinics and hospitals would implement an HCV testing program, but in the real world of scarce resources, “data regarding the cost-effectiveness threshold can guide local policy decisions by directing testing services to settings in which they generate sufficient benefit for the cost.”

Partial funding came from the National Foundation for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC Foundation), with funding provided through multiple donors to the CDC Foundation’s Viral Hepatitis Action Coalition. Dr. Eckman reported grant support from Merck and one coinvestigator reported ties to AbbVie, Gilead, Merck, and several other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Eckman MH et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Sep 7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.08.080.

Universal one-time screening for hepatitis C virus infection is cost effective, compared with birth cohort screening alone, according to the results of a study published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommend testing all individuals born between 1945 and 1965 in addition to injection drug users and other high-risk individuals. But so-called birth cohort screening does not reflect the recent spike in hepatitis C virus (HCV) cases among younger persons in the United States, nor the current recommendation to treat nearly all chronic HCV cases, wrote Mark H. Eckman, MD, of the University of Cincinnati, and his associates.

Using a computer program called Decision Maker, they modeled the cost-effectiveness of universal one-time testing, birth cohort screening, and no screening based on quality-adjusted life-years (QALYS) and 2017 U.S. dollars. They assumed that all HCV-infected patients were treatment naive, treatment eligible, and asymptomatic (for example, had no decompensated cirrhosis). They used efficacy data from the ASTRAL trials of sofosbuvir-velpatasvir as well as the ENDURANCE, SURVEYOR, and EXPEDITION trials of glecaprevir-pibrentasvir. In the model, patients who did not achieve a sustained viral response to treatment went on to complete a 12-week triple direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimen (sofosbuvir, velpatasvir, and voxilaprevir).

Based on these assumptions, universal one-time screening and treatment of infected individuals cost less than $50,000 per QALY gained, making it highly cost effective, compared with no screening, the investigators wrote. Universal screening also was highly cost effective when compared with birth cohort screening, costing $11,378 for each QALY gained.

“Analyses performed during the era of first-generation DAAs and interferon-based treatment regimens found birth-cohort screening to be ‘cost effective,’ ” the researchers wrote. “However, the availability of a new generation of highly effective, non–interferon-based oral regimens, with fewer side effects and shorter treatment courses, has altered the dynamic around the question of screening.” They pointed to another recent study in which universal one-time HCV testing was more cost effective than birth cohort screening.

Such findings have spurred experts to revisit guidelines on HCV screening, but universal testing is controversial when some states, counties, and communities have a low HCV prevalence. In the model, universal one-time HCV screening was cost effective (less than $50,000 per QALY gained), compared with birth cohort screening as long as prevalence exceeded 0.07% among adults not born between 1945 and 1965. The current prevalence estimate in this group is 0.29%, which is probably low because it does not account for the rising incidence among younger adults, the researchers wrote. In an ideal world, all clinics and hospitals would implement an HCV testing program, but in the real world of scarce resources, “data regarding the cost-effectiveness threshold can guide local policy decisions by directing testing services to settings in which they generate sufficient benefit for the cost.”

Partial funding came from the National Foundation for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC Foundation), with funding provided through multiple donors to the CDC Foundation’s Viral Hepatitis Action Coalition. Dr. Eckman reported grant support from Merck and one coinvestigator reported ties to AbbVie, Gilead, Merck, and several other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Eckman MH et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Sep 7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.08.080.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Women survive more often than men do when hospitalized with cirrhosis

Women hospitalized with cirrhosis are less likely to die in the hospital than are men, according to a retrospective analysis of more than half a million patients.

Although women more often had infections and comorbidities, men more often had liver decompensation, which contributed most significantly to their higher mortality rate, reported lead author Jessica Rubin, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues.

Their findings add to an existing body of knowledge about sex-related differences in chronic liver disease. Women are less likely to develop chronic liver disease; however, when women do develop disease, it often follows a unique clinical course, with milder early disease followed by more severe end-stage disease, meaning many women are too sick for a transplant, or die on the waiting list.

“The reasons behind this ‘reversal’ in [sex] disparities is unknown,” the investigators wrote in Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology.

Considering recent findings that showed a correlation between hospitalization and mortality rates in chronic liver disease, the investigators believed that a comparison of hospital-related outcomes in men and women could explain why women apparently fare worse when dealing with end-stage disease.

The retrospective, cross-sectional study involved 553,017 patients (median age, 57 years) who were hospitalized for cirrhosis between 2009 and 2013. Data were drawn from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS). Inpatient mortality was the primary outcome.

In agreement with previous findings, the minority of patients were women (39%). Against expectations, however, women had a significantly lower mortality rate than that of men (5.7% vs. 6.4%; multivariable analysis odds ratio, 0.86). Better survival was associated with lower rates of decompensation (Baveno IV criteria; 34% vs. 38.8%) and other cirrhosis complications, such as hepatorenal syndrome, variceal bleeding, ascites, and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. The only cirrhosis complication more common in women than men was hepatic encephalopathy (17.8% vs. 16.8%). Owing to fewer complications, fewer women required liver-related interventions, including transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (0.8% vs. 1.0%), upper endoscopy (12.8% vs. 13.0%), or paracentesis (17.6% vs. 20.6%).

While less frequent complications and a lower mortality rate might suggest that women were admitted with better overall clinical pictures, not all data supported this conclusion. For instance, women were more likely to have noncirrhosis comorbidities, including diabetes, hypertension, heart failure, stroke, and cancer. Furthermore, women had a higher rate of acute bacterial infection than that of men (34.9% vs. 28.2%), although this disparity should be considered in light of urinary tract infections (UTIs), which were significantly more common among women (18.8% vs. 8.0%).

“Interestingly, infections were a stronger predictor of inpatient mortality in women than men,” the investigators wrote. “Despite this, women in our cohort were less likely to die in the hospital than men.”

Additional analysis revealed etiological differences that may have contributed to differences in mortality rates. For instance, women less often had liver disease due to viral hepatitis (27.6% vs. 35.2%) or alcohol (24.1% vs. 38.7%). In contrast, women more often had autoimmune hepatitis (2.5% vs. 0.4%) or cirrhosis due to unspecified or miscellaneous reasons (45.7% vs. 25.7%).

“Our data suggest that differential rates of ongoing liver injury – including by cofactors such as active alcohol use – explain some but not all of the [sex] difference we observed in hepatic decompensation,” the investigators wrote, before redirecting focus to a clearer clinical finding. “The poor prognosis of decompensated cirrhosis ... provides a reasonable explanation for the higher rates of in-hospital mortality seen among men versus women,” they concluded.

Considering the surprising findings and previously known sex disparities, Dr. Rubin and her colleagues suggested that more research in this area is needed, along with efforts to deliver sex-appropriate care.

“The development of [sex]-specific cirrhosis management programs – focused on interventions to manage the interaction between cirrhosis and other common comorbidities, improving physical function both before and during hospitalization, and postacute discharge programs to facilitate resumption of independent living – would target differential needs of women and men living with cirrhosis, with the ultimate goal of improving long-term outcomes in these patients,” the investigators wrote.

The study was funded by a National Institute on Aging Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award in Aging and a National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases National Research Service Award hepatology training grant. The investigators declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Rubin et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019 Feb 22. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001192.

Women hospitalized with cirrhosis are less likely to die in the hospital than are men, according to a retrospective analysis of more than half a million patients.

Although women more often had infections and comorbidities, men more often had liver decompensation, which contributed most significantly to their higher mortality rate, reported lead author Jessica Rubin, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues.

Their findings add to an existing body of knowledge about sex-related differences in chronic liver disease. Women are less likely to develop chronic liver disease; however, when women do develop disease, it often follows a unique clinical course, with milder early disease followed by more severe end-stage disease, meaning many women are too sick for a transplant, or die on the waiting list.

“The reasons behind this ‘reversal’ in [sex] disparities is unknown,” the investigators wrote in Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology.

Considering recent findings that showed a correlation between hospitalization and mortality rates in chronic liver disease, the investigators believed that a comparison of hospital-related outcomes in men and women could explain why women apparently fare worse when dealing with end-stage disease.

The retrospective, cross-sectional study involved 553,017 patients (median age, 57 years) who were hospitalized for cirrhosis between 2009 and 2013. Data were drawn from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS). Inpatient mortality was the primary outcome.

In agreement with previous findings, the minority of patients were women (39%). Against expectations, however, women had a significantly lower mortality rate than that of men (5.7% vs. 6.4%; multivariable analysis odds ratio, 0.86). Better survival was associated with lower rates of decompensation (Baveno IV criteria; 34% vs. 38.8%) and other cirrhosis complications, such as hepatorenal syndrome, variceal bleeding, ascites, and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. The only cirrhosis complication more common in women than men was hepatic encephalopathy (17.8% vs. 16.8%). Owing to fewer complications, fewer women required liver-related interventions, including transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (0.8% vs. 1.0%), upper endoscopy (12.8% vs. 13.0%), or paracentesis (17.6% vs. 20.6%).

While less frequent complications and a lower mortality rate might suggest that women were admitted with better overall clinical pictures, not all data supported this conclusion. For instance, women were more likely to have noncirrhosis comorbidities, including diabetes, hypertension, heart failure, stroke, and cancer. Furthermore, women had a higher rate of acute bacterial infection than that of men (34.9% vs. 28.2%), although this disparity should be considered in light of urinary tract infections (UTIs), which were significantly more common among women (18.8% vs. 8.0%).

“Interestingly, infections were a stronger predictor of inpatient mortality in women than men,” the investigators wrote. “Despite this, women in our cohort were less likely to die in the hospital than men.”

Additional analysis revealed etiological differences that may have contributed to differences in mortality rates. For instance, women less often had liver disease due to viral hepatitis (27.6% vs. 35.2%) or alcohol (24.1% vs. 38.7%). In contrast, women more often had autoimmune hepatitis (2.5% vs. 0.4%) or cirrhosis due to unspecified or miscellaneous reasons (45.7% vs. 25.7%).

“Our data suggest that differential rates of ongoing liver injury – including by cofactors such as active alcohol use – explain some but not all of the [sex] difference we observed in hepatic decompensation,” the investigators wrote, before redirecting focus to a clearer clinical finding. “The poor prognosis of decompensated cirrhosis ... provides a reasonable explanation for the higher rates of in-hospital mortality seen among men versus women,” they concluded.

Considering the surprising findings and previously known sex disparities, Dr. Rubin and her colleagues suggested that more research in this area is needed, along with efforts to deliver sex-appropriate care.

“The development of [sex]-specific cirrhosis management programs – focused on interventions to manage the interaction between cirrhosis and other common comorbidities, improving physical function both before and during hospitalization, and postacute discharge programs to facilitate resumption of independent living – would target differential needs of women and men living with cirrhosis, with the ultimate goal of improving long-term outcomes in these patients,” the investigators wrote.

The study was funded by a National Institute on Aging Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award in Aging and a National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases National Research Service Award hepatology training grant. The investigators declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Rubin et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019 Feb 22. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001192.

Women hospitalized with cirrhosis are less likely to die in the hospital than are men, according to a retrospective analysis of more than half a million patients.

Although women more often had infections and comorbidities, men more often had liver decompensation, which contributed most significantly to their higher mortality rate, reported lead author Jessica Rubin, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues.

Their findings add to an existing body of knowledge about sex-related differences in chronic liver disease. Women are less likely to develop chronic liver disease; however, when women do develop disease, it often follows a unique clinical course, with milder early disease followed by more severe end-stage disease, meaning many women are too sick for a transplant, or die on the waiting list.

“The reasons behind this ‘reversal’ in [sex] disparities is unknown,” the investigators wrote in Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology.

Considering recent findings that showed a correlation between hospitalization and mortality rates in chronic liver disease, the investigators believed that a comparison of hospital-related outcomes in men and women could explain why women apparently fare worse when dealing with end-stage disease.

The retrospective, cross-sectional study involved 553,017 patients (median age, 57 years) who were hospitalized for cirrhosis between 2009 and 2013. Data were drawn from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS). Inpatient mortality was the primary outcome.

In agreement with previous findings, the minority of patients were women (39%). Against expectations, however, women had a significantly lower mortality rate than that of men (5.7% vs. 6.4%; multivariable analysis odds ratio, 0.86). Better survival was associated with lower rates of decompensation (Baveno IV criteria; 34% vs. 38.8%) and other cirrhosis complications, such as hepatorenal syndrome, variceal bleeding, ascites, and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. The only cirrhosis complication more common in women than men was hepatic encephalopathy (17.8% vs. 16.8%). Owing to fewer complications, fewer women required liver-related interventions, including transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (0.8% vs. 1.0%), upper endoscopy (12.8% vs. 13.0%), or paracentesis (17.6% vs. 20.6%).

While less frequent complications and a lower mortality rate might suggest that women were admitted with better overall clinical pictures, not all data supported this conclusion. For instance, women were more likely to have noncirrhosis comorbidities, including diabetes, hypertension, heart failure, stroke, and cancer. Furthermore, women had a higher rate of acute bacterial infection than that of men (34.9% vs. 28.2%), although this disparity should be considered in light of urinary tract infections (UTIs), which were significantly more common among women (18.8% vs. 8.0%).

“Interestingly, infections were a stronger predictor of inpatient mortality in women than men,” the investigators wrote. “Despite this, women in our cohort were less likely to die in the hospital than men.”

Additional analysis revealed etiological differences that may have contributed to differences in mortality rates. For instance, women less often had liver disease due to viral hepatitis (27.6% vs. 35.2%) or alcohol (24.1% vs. 38.7%). In contrast, women more often had autoimmune hepatitis (2.5% vs. 0.4%) or cirrhosis due to unspecified or miscellaneous reasons (45.7% vs. 25.7%).

“Our data suggest that differential rates of ongoing liver injury – including by cofactors such as active alcohol use – explain some but not all of the [sex] difference we observed in hepatic decompensation,” the investigators wrote, before redirecting focus to a clearer clinical finding. “The poor prognosis of decompensated cirrhosis ... provides a reasonable explanation for the higher rates of in-hospital mortality seen among men versus women,” they concluded.

Considering the surprising findings and previously known sex disparities, Dr. Rubin and her colleagues suggested that more research in this area is needed, along with efforts to deliver sex-appropriate care.

“The development of [sex]-specific cirrhosis management programs – focused on interventions to manage the interaction between cirrhosis and other common comorbidities, improving physical function both before and during hospitalization, and postacute discharge programs to facilitate resumption of independent living – would target differential needs of women and men living with cirrhosis, with the ultimate goal of improving long-term outcomes in these patients,” the investigators wrote.

The study was funded by a National Institute on Aging Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award in Aging and a National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases National Research Service Award hepatology training grant. The investigators declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Rubin et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019 Feb 22. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001192.

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY

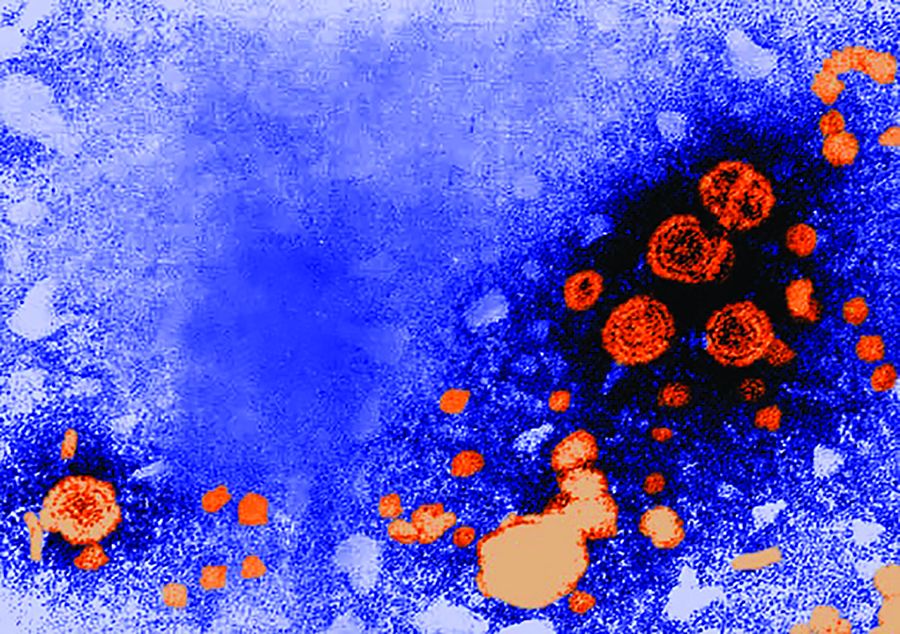

Developing an HCV vaccine faces significant challenges

The development of a prophylactic hepatitis C vaccine faces significant challenges, according to a Justin R. Bailey, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his colleagues.

Barriers to developing a prophylactic HCV vaccine include the great diversity of the virus, the limited models that are available for vaccine testing, and the currently incomplete understanding of protective immune responses, according to their review published in Gastroenterology.

Functionally, the inability to culture HCV, until recently, and continuing limitations of HCV culture systems pose challenges to standard production of a live-attenuated or inactivated whole HCV vaccine. In addition, there is the risk of causing HCV infection with live-attenuated vaccines.

On a practical level for all forms of vaccine development, a principal challenge “is the extraordinary genetic diversity of the virus. With 7 known genotypes and more than 80 subtypes, the genetic diversity of HCV exceeds that of human immunodeficiency virus-1,” according to the authors (Gastroenterology 2019;156[2]:418-30).

With regard to vaccine testing, there are also significant difficulties: There is a lack of in vitro systems and immunocompetent small-animal models useful for determining whether vaccination induces protective immunity. Although a use of an HCV-like virus, the rat Hepacivirus, provides a new small-animal model for vaccine testing, this virus has limited sequence analogy to HCV.

The development of immunity to HCV in humans is complex and under broad investigation. However, decades of research have revealed that HCV-specific CD4+ helper T cells, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, and antibodies all play a role in protection against persistent HCV infection, according to the authors, and vaccine strategies to induce all three adaptive immune responses are in development.

“A prophylactic HCV vaccine is an important part of a successful strategy for global control. Although development is not easy, the quest is a worthy challenge,” the authors concluded.

Dr. Bailey and his colleagues reported that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Bailey JR et al. Gastroenterology 2019(2);156:418-30.

The development of a prophylactic hepatitis C vaccine faces significant challenges, according to a Justin R. Bailey, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his colleagues.

Barriers to developing a prophylactic HCV vaccine include the great diversity of the virus, the limited models that are available for vaccine testing, and the currently incomplete understanding of protective immune responses, according to their review published in Gastroenterology.

Functionally, the inability to culture HCV, until recently, and continuing limitations of HCV culture systems pose challenges to standard production of a live-attenuated or inactivated whole HCV vaccine. In addition, there is the risk of causing HCV infection with live-attenuated vaccines.

On a practical level for all forms of vaccine development, a principal challenge “is the extraordinary genetic diversity of the virus. With 7 known genotypes and more than 80 subtypes, the genetic diversity of HCV exceeds that of human immunodeficiency virus-1,” according to the authors (Gastroenterology 2019;156[2]:418-30).

With regard to vaccine testing, there are also significant difficulties: There is a lack of in vitro systems and immunocompetent small-animal models useful for determining whether vaccination induces protective immunity. Although a use of an HCV-like virus, the rat Hepacivirus, provides a new small-animal model for vaccine testing, this virus has limited sequence analogy to HCV.

The development of immunity to HCV in humans is complex and under broad investigation. However, decades of research have revealed that HCV-specific CD4+ helper T cells, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, and antibodies all play a role in protection against persistent HCV infection, according to the authors, and vaccine strategies to induce all three adaptive immune responses are in development.

“A prophylactic HCV vaccine is an important part of a successful strategy for global control. Although development is not easy, the quest is a worthy challenge,” the authors concluded.

Dr. Bailey and his colleagues reported that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Bailey JR et al. Gastroenterology 2019(2);156:418-30.

The development of a prophylactic hepatitis C vaccine faces significant challenges, according to a Justin R. Bailey, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and his colleagues.

Barriers to developing a prophylactic HCV vaccine include the great diversity of the virus, the limited models that are available for vaccine testing, and the currently incomplete understanding of protective immune responses, according to their review published in Gastroenterology.

Functionally, the inability to culture HCV, until recently, and continuing limitations of HCV culture systems pose challenges to standard production of a live-attenuated or inactivated whole HCV vaccine. In addition, there is the risk of causing HCV infection with live-attenuated vaccines.

On a practical level for all forms of vaccine development, a principal challenge “is the extraordinary genetic diversity of the virus. With 7 known genotypes and more than 80 subtypes, the genetic diversity of HCV exceeds that of human immunodeficiency virus-1,” according to the authors (Gastroenterology 2019;156[2]:418-30).

With regard to vaccine testing, there are also significant difficulties: There is a lack of in vitro systems and immunocompetent small-animal models useful for determining whether vaccination induces protective immunity. Although a use of an HCV-like virus, the rat Hepacivirus, provides a new small-animal model for vaccine testing, this virus has limited sequence analogy to HCV.

The development of immunity to HCV in humans is complex and under broad investigation. However, decades of research have revealed that HCV-specific CD4+ helper T cells, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, and antibodies all play a role in protection against persistent HCV infection, according to the authors, and vaccine strategies to induce all three adaptive immune responses are in development.

“A prophylactic HCV vaccine is an important part of a successful strategy for global control. Although development is not easy, the quest is a worthy challenge,” the authors concluded.

Dr. Bailey and his colleagues reported that they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Bailey JR et al. Gastroenterology 2019(2);156:418-30.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Possible biomarkers found for progression to liver cancer in chronic HCV infection

according to the results of a biochemical analysis of human blood samples performed by PhD student Paywast J. Jalal of the University of Sulaimani (Iraq) and colleagues.

Archived HCV-positive serum samples, including those from 31 patients who had developed HCC, were retrieved from the Trent HCV clinical cohort. They were compared with each other over time and against samples from HCV-infected individuals in the cohort who did not develop HCC. In addition, HCV-negative serum samples were obtained commercially and assessed identically. Circulating liver-expressed lectins, ficolin-2, ficolin-3, and MBL were all examined as potential biomarkers for the development of HCC, the authors wrote in Virology.

Binding of ficolin-3 to reference ligands was greater in chronic HCV infection, while ficolin-2 and MBL were significantly elevated in individuals who develop HCC, compared with HCV-infected individuals without HCC. Ficolin-2 and MBL were found to be elevated at 1 and 3 years prior to HCC diagnosis, respectively, suggesting they could be used as prognostic serum markers for the development of HCC.

“The strong evidence for an association between elevated MBL binding activity and the development of HCC is supportive for a larger prospective study of these biomarkers in HCV-induced liver cancer,” the researchers concluded.

This study was funded by a split-site PhD scholarship between the University of Sulaimani and the University of Nottingham (England). The authors reported they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Jalal PJ et al. Virology. 2019;530:99-106.

according to the results of a biochemical analysis of human blood samples performed by PhD student Paywast J. Jalal of the University of Sulaimani (Iraq) and colleagues.

Archived HCV-positive serum samples, including those from 31 patients who had developed HCC, were retrieved from the Trent HCV clinical cohort. They were compared with each other over time and against samples from HCV-infected individuals in the cohort who did not develop HCC. In addition, HCV-negative serum samples were obtained commercially and assessed identically. Circulating liver-expressed lectins, ficolin-2, ficolin-3, and MBL were all examined as potential biomarkers for the development of HCC, the authors wrote in Virology.

Binding of ficolin-3 to reference ligands was greater in chronic HCV infection, while ficolin-2 and MBL were significantly elevated in individuals who develop HCC, compared with HCV-infected individuals without HCC. Ficolin-2 and MBL were found to be elevated at 1 and 3 years prior to HCC diagnosis, respectively, suggesting they could be used as prognostic serum markers for the development of HCC.

“The strong evidence for an association between elevated MBL binding activity and the development of HCC is supportive for a larger prospective study of these biomarkers in HCV-induced liver cancer,” the researchers concluded.

This study was funded by a split-site PhD scholarship between the University of Sulaimani and the University of Nottingham (England). The authors reported they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Jalal PJ et al. Virology. 2019;530:99-106.

according to the results of a biochemical analysis of human blood samples performed by PhD student Paywast J. Jalal of the University of Sulaimani (Iraq) and colleagues.

Archived HCV-positive serum samples, including those from 31 patients who had developed HCC, were retrieved from the Trent HCV clinical cohort. They were compared with each other over time and against samples from HCV-infected individuals in the cohort who did not develop HCC. In addition, HCV-negative serum samples were obtained commercially and assessed identically. Circulating liver-expressed lectins, ficolin-2, ficolin-3, and MBL were all examined as potential biomarkers for the development of HCC, the authors wrote in Virology.

Binding of ficolin-3 to reference ligands was greater in chronic HCV infection, while ficolin-2 and MBL were significantly elevated in individuals who develop HCC, compared with HCV-infected individuals without HCC. Ficolin-2 and MBL were found to be elevated at 1 and 3 years prior to HCC diagnosis, respectively, suggesting they could be used as prognostic serum markers for the development of HCC.

“The strong evidence for an association between elevated MBL binding activity and the development of HCC is supportive for a larger prospective study of these biomarkers in HCV-induced liver cancer,” the researchers concluded.

This study was funded by a split-site PhD scholarship between the University of Sulaimani and the University of Nottingham (England). The authors reported they had no conflicts.

SOURCE: Jalal PJ et al. Virology. 2019;530:99-106.

FROM VIROLOGY

Novel capsid assembly modulator shows promise in HBV

For adults with chronic hepatitis B virus infection, treatment with a novel investigational capsid assembly modulator was well tolerated and showed antiviral activity against HBV, according to the results of a phase 1 study of 73 patients.

“Substantial and correlated reductions in serum HBV DNA and HBV RNA levels were observed consistently with the higher-dose cohorts and were notably greatest for combination treatment with NVR 3-778 and pegIFN [pegylated interferon],” Man Fung Yuen, MD, of the University of Hong Kong, and his associates wrote in a report published in Gastroenterology. Hence, this first-in-class capsid assembly modulator might help prolong treatment responses, “most likely as a component of new combination treatment regimens for HBV-infected patients.” However, one patient developed severe rash immediately after completing treatment that took 6 months of intensive outpatient treatment to resolve, they noted.

Chronic viral hepatitis due to HBV is a major cause of early death worldwide, and new therapies are needed to help prevent severe liver disease and liver death from this infection. Current treatments for HBV infection consist of nucleoside or nucleotide analogs or pegylated interferon. These suppress HBV replication in many patients, but most patients do not achieve durable responses. Consequently, most patients require long-term treatment with HBV nucleosides and nucleotide analogs, which they may find difficult to tolerate or adhere to and to which their infections can become resistant, the researchers said.

The HBV virion contains a viral core protein (HBc) that is required to encapsidate viral polymerase and pregenomic HBV RNA into a nucleocapsid. To target this process, researchers developed NVR 3-778, a first-in-class, orally bioavailable small molecule that binds HBc so that HBc forms a defective capsid that lacks nuclear material. Hence, NVR 3-778 is intended to stop the production of HBV nucleocapsids and keep infected cells from releasing the enveloped infectious viral particles that perpetuate HBV infection.

To assess the safety, pharmacokinetics, and antiviral activity of NVR 3-778, the researchers conducted a phase 1 study of 73 patients with chronic HBV infection who tested positive for hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg) and had no detectable cirrhosis. Patients were randomly assigned to receive oral NVR 3-778 (100 mg, 200 mg, or 400 mg daily or 600 mg or 1,000 mg twice daily ) or placebo for 28 days. Some patients received combination therapy with pegylated interferon plus either NVR 3-778 (600 mg twice daily) or placebo. Treatment was generally well tolerated, and adverse events were usually mild and deemed unrelated to therapy. No patient stopped treatment for adverse effects.

The only serious adverse event in the study consisted of grade 3 rash that developed in a 42-year-old male after 22 days of treatment at the lowest dose of NVR 3-778 (100 mg per day). This patient completed treatment and ultimately developed a severe papulovesicular rash with a predominantly acral distribution over the hands, arm, side of neck, and one leg (palmar plantar erythrodysesthesia), the researchers said. “There were no perioral or mucosal lesions, no ecchymotic skin involvement, no bullae, and no systemic manifestations or hematological abnormalities,” they wrote. “The rash was subsequently managed with a psoriasis-like treatment regimen of psoralen, ultraviolet light, and topical steroid ointment during outpatient follow-up and resolved after approximately 6 months.”

Another three cases of “minor” skin rash were considered probably related to treatment in the cohort that received 600 mg NVR 3-778 b.i.d. plus pegylated interferon, the investigators said. Two additional cases of mild rash were deemed unrelated to treatment.

“The observed reductions in HBV RNA confirmed the novel mechanism of NVR 3-778,” the researchers concluded. “This class of compounds can also inhibit replenishment of intranuclear covalently closed circular DNA over time and may have immunomodulatory properties.” Longer treatment periods would be needed to study these mechanisms and to quantify reductions in serum HBsAg and HBeAG, they noted.

Novira Therapeutics developed NVR 3-778 and is a Janssen Pharmaceutical Company. Janssen provided funding for editorial support. Dr. Yuen disclosed relationships with AbbVie, Biocartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Ionis, Roche, Vir Biotechnology, and several other pharmaceutical companies. Other coinvestigators disclosed ties to pharmaceutical companies; eight reported employment by Novira or a Janssen company.

SOURCE: Yuen MF et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jan 5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.023.

For adults with chronic hepatitis B virus infection, treatment with a novel investigational capsid assembly modulator was well tolerated and showed antiviral activity against HBV, according to the results of a phase 1 study of 73 patients.

“Substantial and correlated reductions in serum HBV DNA and HBV RNA levels were observed consistently with the higher-dose cohorts and were notably greatest for combination treatment with NVR 3-778 and pegIFN [pegylated interferon],” Man Fung Yuen, MD, of the University of Hong Kong, and his associates wrote in a report published in Gastroenterology. Hence, this first-in-class capsid assembly modulator might help prolong treatment responses, “most likely as a component of new combination treatment regimens for HBV-infected patients.” However, one patient developed severe rash immediately after completing treatment that took 6 months of intensive outpatient treatment to resolve, they noted.

Chronic viral hepatitis due to HBV is a major cause of early death worldwide, and new therapies are needed to help prevent severe liver disease and liver death from this infection. Current treatments for HBV infection consist of nucleoside or nucleotide analogs or pegylated interferon. These suppress HBV replication in many patients, but most patients do not achieve durable responses. Consequently, most patients require long-term treatment with HBV nucleosides and nucleotide analogs, which they may find difficult to tolerate or adhere to and to which their infections can become resistant, the researchers said.

The HBV virion contains a viral core protein (HBc) that is required to encapsidate viral polymerase and pregenomic HBV RNA into a nucleocapsid. To target this process, researchers developed NVR 3-778, a first-in-class, orally bioavailable small molecule that binds HBc so that HBc forms a defective capsid that lacks nuclear material. Hence, NVR 3-778 is intended to stop the production of HBV nucleocapsids and keep infected cells from releasing the enveloped infectious viral particles that perpetuate HBV infection.

To assess the safety, pharmacokinetics, and antiviral activity of NVR 3-778, the researchers conducted a phase 1 study of 73 patients with chronic HBV infection who tested positive for hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg) and had no detectable cirrhosis. Patients were randomly assigned to receive oral NVR 3-778 (100 mg, 200 mg, or 400 mg daily or 600 mg or 1,000 mg twice daily ) or placebo for 28 days. Some patients received combination therapy with pegylated interferon plus either NVR 3-778 (600 mg twice daily) or placebo. Treatment was generally well tolerated, and adverse events were usually mild and deemed unrelated to therapy. No patient stopped treatment for adverse effects.

The only serious adverse event in the study consisted of grade 3 rash that developed in a 42-year-old male after 22 days of treatment at the lowest dose of NVR 3-778 (100 mg per day). This patient completed treatment and ultimately developed a severe papulovesicular rash with a predominantly acral distribution over the hands, arm, side of neck, and one leg (palmar plantar erythrodysesthesia), the researchers said. “There were no perioral or mucosal lesions, no ecchymotic skin involvement, no bullae, and no systemic manifestations or hematological abnormalities,” they wrote. “The rash was subsequently managed with a psoriasis-like treatment regimen of psoralen, ultraviolet light, and topical steroid ointment during outpatient follow-up and resolved after approximately 6 months.”

Another three cases of “minor” skin rash were considered probably related to treatment in the cohort that received 600 mg NVR 3-778 b.i.d. plus pegylated interferon, the investigators said. Two additional cases of mild rash were deemed unrelated to treatment.

“The observed reductions in HBV RNA confirmed the novel mechanism of NVR 3-778,” the researchers concluded. “This class of compounds can also inhibit replenishment of intranuclear covalently closed circular DNA over time and may have immunomodulatory properties.” Longer treatment periods would be needed to study these mechanisms and to quantify reductions in serum HBsAg and HBeAG, they noted.

Novira Therapeutics developed NVR 3-778 and is a Janssen Pharmaceutical Company. Janssen provided funding for editorial support. Dr. Yuen disclosed relationships with AbbVie, Biocartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Ionis, Roche, Vir Biotechnology, and several other pharmaceutical companies. Other coinvestigators disclosed ties to pharmaceutical companies; eight reported employment by Novira or a Janssen company.

SOURCE: Yuen MF et al. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jan 5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.023.

For adults with chronic hepatitis B virus infection, treatment with a novel investigational capsid assembly modulator was well tolerated and showed antiviral activity against HBV, according to the results of a phase 1 study of 73 patients.

“Substantial and correlated reductions in serum HBV DNA and HBV RNA levels were observed consistently with the higher-dose cohorts and were notably greatest for combination treatment with NVR 3-778 and pegIFN [pegylated interferon],” Man Fung Yuen, MD, of the University of Hong Kong, and his associates wrote in a report published in Gastroenterology. Hence, this first-in-class capsid assembly modulator might help prolong treatment responses, “most likely as a component of new combination treatment regimens for HBV-infected patients.” However, one patient developed severe rash immediately after completing treatment that took 6 months of intensive outpatient treatment to resolve, they noted.

Chronic viral hepatitis due to HBV is a major cause of early death worldwide, and new therapies are needed to help prevent severe liver disease and liver death from this infection. Current treatments for HBV infection consist of nucleoside or nucleotide analogs or pegylated interferon. These suppress HBV replication in many patients, but most patients do not achieve durable responses. Consequently, most patients require long-term treatment with HBV nucleosides and nucleotide analogs, which they may find difficult to tolerate or adhere to and to which their infections can become resistant, the researchers said.

The HBV virion contains a viral core protein (HBc) that is required to encapsidate viral polymerase and pregenomic HBV RNA into a nucleocapsid. To target this process, researchers developed NVR 3-778, a first-in-class, orally bioavailable small molecule that binds HBc so that HBc forms a defective capsid that lacks nuclear material. Hence, NVR 3-778 is intended to stop the production of HBV nucleocapsids and keep infected cells from releasing the enveloped infectious viral particles that perpetuate HBV infection.

To assess the safety, pharmacokinetics, and antiviral activity of NVR 3-778, the researchers conducted a phase 1 study of 73 patients with chronic HBV infection who tested positive for hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg) and had no detectable cirrhosis. Patients were randomly assigned to receive oral NVR 3-778 (100 mg, 200 mg, or 400 mg daily or 600 mg or 1,000 mg twice daily ) or placebo for 28 days. Some patients received combination therapy with pegylated interferon plus either NVR 3-778 (600 mg twice daily) or placebo. Treatment was generally well tolerated, and adverse events were usually mild and deemed unrelated to therapy. No patient stopped treatment for adverse effects.

The only serious adverse event in the study consisted of grade 3 rash that developed in a 42-year-old male after 22 days of treatment at the lowest dose of NVR 3-778 (100 mg per day). This patient completed treatment and ultimately developed a severe papulovesicular rash with a predominantly acral distribution over the hands, arm, side of neck, and one leg (palmar plantar erythrodysesthesia), the researchers said. “There were no perioral or mucosal lesions, no ecchymotic skin involvement, no bullae, and no systemic manifestations or hematological abnormalities,” they wrote. “The rash was subsequently managed with a psoriasis-like treatment regimen of psoralen, ultraviolet light, and topical steroid ointment during outpatient follow-up and resolved after approximately 6 months.”

Another three cases of “minor” skin rash were considered probably related to treatment in the cohort that received 600 mg NVR 3-778 b.i.d. plus pegylated interferon, the investigators said. Two additional cases of mild rash were deemed unrelated to treatment.

“The observed reductions in HBV RNA confirmed the novel mechanism of NVR 3-778,” the researchers concluded. “This class of compounds can also inhibit replenishment of intranuclear covalently closed circular DNA over time and may have immunomodulatory properties.” Longer treatment periods would be needed to study these mechanisms and to quantify reductions in serum HBsAg and HBeAG, they noted.