User login

Malawi declares polio outbreak after girl, 3, paralyzed

Health authorities in Malawi have declared an outbreak of wild poliovirus type 1 after a case was confirmed in a 3-year-old girl in the capital, Lilongwe. It was the first case in Africa in 5 years, according to the World Health Organization.

Globally, there were only five cases of wild poliovirus in 2021, the WHO states.

“As long as wild polio exists anywhere in the world all countries remain at risk of importation of the virus,” Matshidiso Moeti, MBBS, WHO regional director for Africa, said in the statement.

Girl paralyzed in November

The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) said in a statement that the 3-year-old girl experienced paralysis in November, and stool specimens were collected. Sequencing of the virus was conducted in February, 2022, by the National Institute for Communicable Diseases in South Africa, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the case as WPV1.

According to the WHO announcement, laboratory analysis shows that the strain identified in Malawi is linked to one circulating in Sindh Province in Pakistan. Polio remains endemic only in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Kacey C. Ernst, PhD, MPH, professor and infectious disease epidemiologist at the University of Arizona’s Zuckerman College of Public Health in Tucson, pointed out that what is not clear from the press release is whether the girl had traveled to Pakistan or was infected in Malawi.

“This is a very significant detail that would indicate whether or not transmission was actively occurring in Malawi. Until that information is released, it is hard to judge the extent of the possible outbreak,” she said in an interview. “The good news is that this case was in fact detected. The surveillance systems are in place and they were able to identify wild-type cases.”

Dr. Ernst said that although there is cause for concern, it is “not a reason to panic. Malawi has very high polio vaccination rates and it is quite possible that this will be a very small defined outbreak that will be well contained.”

She added that the medical community should be alerted that this case has been identified so travelers who have been to affected areas who have any symptoms can be appropriately screened.

The WHO said it is helping Malawi health authorities in the response, including increasing immunizations.

However, a vaccination campaign comes at a time of health system upheaval in Malawi.

“Malawi, like countries all over the world, has seen an interruption in services due to COVID,” Joia S. Mukherjee, MD, MPH, chief medical officer with Partners in Health and associate professor with the division of global health equity at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and in the department of global health and social medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview. “In addition, Malawi is currently dealing with the aftermath of a cyclone – where nearly a million people were displaced. Vaccination campaigns work best if there is solid infrastructure. Both COVID and the impact of climate change have shaken the health system.”

UN health agencies warned last year that millions of children who have not received immunizations during the pandemic, especially in Africa, “are now at risk from life-threatening diseases such as measles, polio, yellow fever, and diphtheria,” Reuters reported.

Africa was certified as wild poliovirus free on Aug. 25, 2020. The CDC had served as the lead partner over 3 decades in helping Africa reach the milestone. Africa will retain that status, the WHO stated, because the strain originated in Pakistan.

Five of six WHO regions have been certified polio free. The Americas received eradication certification in 1994.

There is no cure for polio, which can cause irreversible paralysis within hours, but the disease has been largely eradicated globally with an effective vaccine.

GPEI sending teams

The GPEI is sending a team to Malawi to support emergency operations, communications, and surveillance. Partner organizations will also send teams to support operations and innovative vaccination campaign solutions.

GPEI was launched in 1988 with the combined efforts of national governments, WHO, Rotary International, the CDC, and UNICEF. The GPEI partnership has included the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and, in recent years, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

The CDC states, “[G]lobal incidence of polio has decreased by 99.9% since GPEI’s foundation. An estimated 16 million people today are walking who would otherwise have been paralyzed by the disease, and more than 1.5 million people are alive, whose lives would otherwise have been lost. Now the task remains to tackle polio in its last few strongholds and get rid of the final 0.1% of polio cases.”

Three wild poliovirus strains

There are three wild poliovirus strains: type 1 (WPV1), type 2 (WPV2), and type 3 (WPV3).

“Symptomatically, all three strains are identical, in that they cause irreversible paralysis or even death. But there are genetic and virologic differences which make these three strains three separate viruses that must each be eradicated individually,” according to WHO.

WPV3 is the second strain to be wiped out, following the certification of the eradication of WPV2 in 2015.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Health authorities in Malawi have declared an outbreak of wild poliovirus type 1 after a case was confirmed in a 3-year-old girl in the capital, Lilongwe. It was the first case in Africa in 5 years, according to the World Health Organization.

Globally, there were only five cases of wild poliovirus in 2021, the WHO states.

“As long as wild polio exists anywhere in the world all countries remain at risk of importation of the virus,” Matshidiso Moeti, MBBS, WHO regional director for Africa, said in the statement.

Girl paralyzed in November

The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) said in a statement that the 3-year-old girl experienced paralysis in November, and stool specimens were collected. Sequencing of the virus was conducted in February, 2022, by the National Institute for Communicable Diseases in South Africa, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the case as WPV1.

According to the WHO announcement, laboratory analysis shows that the strain identified in Malawi is linked to one circulating in Sindh Province in Pakistan. Polio remains endemic only in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Kacey C. Ernst, PhD, MPH, professor and infectious disease epidemiologist at the University of Arizona’s Zuckerman College of Public Health in Tucson, pointed out that what is not clear from the press release is whether the girl had traveled to Pakistan or was infected in Malawi.

“This is a very significant detail that would indicate whether or not transmission was actively occurring in Malawi. Until that information is released, it is hard to judge the extent of the possible outbreak,” she said in an interview. “The good news is that this case was in fact detected. The surveillance systems are in place and they were able to identify wild-type cases.”

Dr. Ernst said that although there is cause for concern, it is “not a reason to panic. Malawi has very high polio vaccination rates and it is quite possible that this will be a very small defined outbreak that will be well contained.”

She added that the medical community should be alerted that this case has been identified so travelers who have been to affected areas who have any symptoms can be appropriately screened.

The WHO said it is helping Malawi health authorities in the response, including increasing immunizations.

However, a vaccination campaign comes at a time of health system upheaval in Malawi.

“Malawi, like countries all over the world, has seen an interruption in services due to COVID,” Joia S. Mukherjee, MD, MPH, chief medical officer with Partners in Health and associate professor with the division of global health equity at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and in the department of global health and social medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview. “In addition, Malawi is currently dealing with the aftermath of a cyclone – where nearly a million people were displaced. Vaccination campaigns work best if there is solid infrastructure. Both COVID and the impact of climate change have shaken the health system.”

UN health agencies warned last year that millions of children who have not received immunizations during the pandemic, especially in Africa, “are now at risk from life-threatening diseases such as measles, polio, yellow fever, and diphtheria,” Reuters reported.

Africa was certified as wild poliovirus free on Aug. 25, 2020. The CDC had served as the lead partner over 3 decades in helping Africa reach the milestone. Africa will retain that status, the WHO stated, because the strain originated in Pakistan.

Five of six WHO regions have been certified polio free. The Americas received eradication certification in 1994.

There is no cure for polio, which can cause irreversible paralysis within hours, but the disease has been largely eradicated globally with an effective vaccine.

GPEI sending teams

The GPEI is sending a team to Malawi to support emergency operations, communications, and surveillance. Partner organizations will also send teams to support operations and innovative vaccination campaign solutions.

GPEI was launched in 1988 with the combined efforts of national governments, WHO, Rotary International, the CDC, and UNICEF. The GPEI partnership has included the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and, in recent years, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

The CDC states, “[G]lobal incidence of polio has decreased by 99.9% since GPEI’s foundation. An estimated 16 million people today are walking who would otherwise have been paralyzed by the disease, and more than 1.5 million people are alive, whose lives would otherwise have been lost. Now the task remains to tackle polio in its last few strongholds and get rid of the final 0.1% of polio cases.”

Three wild poliovirus strains

There are three wild poliovirus strains: type 1 (WPV1), type 2 (WPV2), and type 3 (WPV3).

“Symptomatically, all three strains are identical, in that they cause irreversible paralysis or even death. But there are genetic and virologic differences which make these three strains three separate viruses that must each be eradicated individually,” according to WHO.

WPV3 is the second strain to be wiped out, following the certification of the eradication of WPV2 in 2015.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Health authorities in Malawi have declared an outbreak of wild poliovirus type 1 after a case was confirmed in a 3-year-old girl in the capital, Lilongwe. It was the first case in Africa in 5 years, according to the World Health Organization.

Globally, there were only five cases of wild poliovirus in 2021, the WHO states.

“As long as wild polio exists anywhere in the world all countries remain at risk of importation of the virus,” Matshidiso Moeti, MBBS, WHO regional director for Africa, said in the statement.

Girl paralyzed in November

The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) said in a statement that the 3-year-old girl experienced paralysis in November, and stool specimens were collected. Sequencing of the virus was conducted in February, 2022, by the National Institute for Communicable Diseases in South Africa, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed the case as WPV1.

According to the WHO announcement, laboratory analysis shows that the strain identified in Malawi is linked to one circulating in Sindh Province in Pakistan. Polio remains endemic only in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Kacey C. Ernst, PhD, MPH, professor and infectious disease epidemiologist at the University of Arizona’s Zuckerman College of Public Health in Tucson, pointed out that what is not clear from the press release is whether the girl had traveled to Pakistan or was infected in Malawi.

“This is a very significant detail that would indicate whether or not transmission was actively occurring in Malawi. Until that information is released, it is hard to judge the extent of the possible outbreak,” she said in an interview. “The good news is that this case was in fact detected. The surveillance systems are in place and they were able to identify wild-type cases.”

Dr. Ernst said that although there is cause for concern, it is “not a reason to panic. Malawi has very high polio vaccination rates and it is quite possible that this will be a very small defined outbreak that will be well contained.”

She added that the medical community should be alerted that this case has been identified so travelers who have been to affected areas who have any symptoms can be appropriately screened.

The WHO said it is helping Malawi health authorities in the response, including increasing immunizations.

However, a vaccination campaign comes at a time of health system upheaval in Malawi.

“Malawi, like countries all over the world, has seen an interruption in services due to COVID,” Joia S. Mukherjee, MD, MPH, chief medical officer with Partners in Health and associate professor with the division of global health equity at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and in the department of global health and social medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview. “In addition, Malawi is currently dealing with the aftermath of a cyclone – where nearly a million people were displaced. Vaccination campaigns work best if there is solid infrastructure. Both COVID and the impact of climate change have shaken the health system.”

UN health agencies warned last year that millions of children who have not received immunizations during the pandemic, especially in Africa, “are now at risk from life-threatening diseases such as measles, polio, yellow fever, and diphtheria,” Reuters reported.

Africa was certified as wild poliovirus free on Aug. 25, 2020. The CDC had served as the lead partner over 3 decades in helping Africa reach the milestone. Africa will retain that status, the WHO stated, because the strain originated in Pakistan.

Five of six WHO regions have been certified polio free. The Americas received eradication certification in 1994.

There is no cure for polio, which can cause irreversible paralysis within hours, but the disease has been largely eradicated globally with an effective vaccine.

GPEI sending teams

The GPEI is sending a team to Malawi to support emergency operations, communications, and surveillance. Partner organizations will also send teams to support operations and innovative vaccination campaign solutions.

GPEI was launched in 1988 with the combined efforts of national governments, WHO, Rotary International, the CDC, and UNICEF. The GPEI partnership has included the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and, in recent years, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

The CDC states, “[G]lobal incidence of polio has decreased by 99.9% since GPEI’s foundation. An estimated 16 million people today are walking who would otherwise have been paralyzed by the disease, and more than 1.5 million people are alive, whose lives would otherwise have been lost. Now the task remains to tackle polio in its last few strongholds and get rid of the final 0.1% of polio cases.”

Three wild poliovirus strains

There are three wild poliovirus strains: type 1 (WPV1), type 2 (WPV2), and type 3 (WPV3).

“Symptomatically, all three strains are identical, in that they cause irreversible paralysis or even death. But there are genetic and virologic differences which make these three strains three separate viruses that must each be eradicated individually,” according to WHO.

WPV3 is the second strain to be wiped out, following the certification of the eradication of WPV2 in 2015.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mosquito nets do prevent malaria, longitudinal study confirms

It seems obvious that increased use of mosquito bed nets in sub-Saharan Africa would decrease the incidence of malaria, but a lingering question remained:

Malaria from Plasmodium falciparum infection exacts a significant toll in sub-Saharan Africa. According to the World Health Organization, there were about 228 million cases and 602,000 deaths from malaria in 2020 alone. About 80% of those deaths were in children less than 5 years old. In some areas, as many as 5% of children die from malaria by age 5.

Efforts to reduce the burden of malaria have been ongoing for decades. In the 1990s, insecticide-treated nets were shown to reduce illness and deaths from malaria in children.

As a result, the use of bed nets has grown significantly. In 2000, only 5% of households in sub-Saharan Africa had a net in the house. By 2020, that number had risen to 65%. From 2004 to 2019 about 1.9 billion nets were distributed in this region. The nets are estimated to have prevented more than 663 million malaria cases between 2000 and 2015.

As described in the NEJM report, public health researchers conducted a 22-year prospective longitudinal cohort study in rural southern Tanzania following 6,706 children born between 1998 and 2000. Initially, home visits were made every 4 months from May 1998 to April 2003. Remarkably, in 2019, they were able to verify the status of fully 89% of those people by reaching out to families and community/village leaders.

Günther Fink, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology and household economics, University of Basel (Switzerland), explained the approach and primary findings to this news organization. The analysis looked at three main groups – children whose parents said they always slept under treated nets, those who slept protected most of the time, and those who spent less than half the time under bed nets. The hazard ratio for death was 0.57 (95% confidence interval, 0.45-0.72) for the first two groups, compared with the least protected. The corresponding hazard ratio between age 5 and adulthood was 0.93 (95% CI, 0.58-1.49).

The findings confirmed what they had suspected. Dr. Fink summarized simply, “If you always slept under a net, you did much better than if you never slept under the net. If you slept [under a net] more than half of the time, it was much better than if you slept [under a net] less than half the time.” So the more time children slept under bed nets, the less likely they were to acquire malaria. Dr. Fink stressed that the findings showing protective efficacy persisted into adulthood. “It seems just having a healthier early life actually makes you more resilient against other future infections.”

One of the theoretical concerns was that using nets would delay developing functional immunity and that there might be an increase in mortality seen later. This study showed that did not happen.

An accompanying commentary noted that there was some potential that families receiving nets were better off than those that didn’t but concluded that such confounding had been accounted for in other analyses.

Mark Wilson, ScD, professor emeritus of epidemiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, concurred. He told this news organization that the study was “very well designed,” and the researchers “did a fantastic job” in tracking patients 20 years later.

“This is astounding!” he added. “It’s very rare to find this amount of follow-up.”

Dr. Fink’s conclusion? “Bed nets protect you in the short run, and being protected in the short run is also beneficial in the long run. There is no evidence that protecting kids in early childhood is weakening them in any way. So we should keep doing this.”

Dr. Fink and Dr. Wilson report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It seems obvious that increased use of mosquito bed nets in sub-Saharan Africa would decrease the incidence of malaria, but a lingering question remained:

Malaria from Plasmodium falciparum infection exacts a significant toll in sub-Saharan Africa. According to the World Health Organization, there were about 228 million cases and 602,000 deaths from malaria in 2020 alone. About 80% of those deaths were in children less than 5 years old. In some areas, as many as 5% of children die from malaria by age 5.

Efforts to reduce the burden of malaria have been ongoing for decades. In the 1990s, insecticide-treated nets were shown to reduce illness and deaths from malaria in children.

As a result, the use of bed nets has grown significantly. In 2000, only 5% of households in sub-Saharan Africa had a net in the house. By 2020, that number had risen to 65%. From 2004 to 2019 about 1.9 billion nets were distributed in this region. The nets are estimated to have prevented more than 663 million malaria cases between 2000 and 2015.

As described in the NEJM report, public health researchers conducted a 22-year prospective longitudinal cohort study in rural southern Tanzania following 6,706 children born between 1998 and 2000. Initially, home visits were made every 4 months from May 1998 to April 2003. Remarkably, in 2019, they were able to verify the status of fully 89% of those people by reaching out to families and community/village leaders.

Günther Fink, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology and household economics, University of Basel (Switzerland), explained the approach and primary findings to this news organization. The analysis looked at three main groups – children whose parents said they always slept under treated nets, those who slept protected most of the time, and those who spent less than half the time under bed nets. The hazard ratio for death was 0.57 (95% confidence interval, 0.45-0.72) for the first two groups, compared with the least protected. The corresponding hazard ratio between age 5 and adulthood was 0.93 (95% CI, 0.58-1.49).

The findings confirmed what they had suspected. Dr. Fink summarized simply, “If you always slept under a net, you did much better than if you never slept under the net. If you slept [under a net] more than half of the time, it was much better than if you slept [under a net] less than half the time.” So the more time children slept under bed nets, the less likely they were to acquire malaria. Dr. Fink stressed that the findings showing protective efficacy persisted into adulthood. “It seems just having a healthier early life actually makes you more resilient against other future infections.”

One of the theoretical concerns was that using nets would delay developing functional immunity and that there might be an increase in mortality seen later. This study showed that did not happen.

An accompanying commentary noted that there was some potential that families receiving nets were better off than those that didn’t but concluded that such confounding had been accounted for in other analyses.

Mark Wilson, ScD, professor emeritus of epidemiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, concurred. He told this news organization that the study was “very well designed,” and the researchers “did a fantastic job” in tracking patients 20 years later.

“This is astounding!” he added. “It’s very rare to find this amount of follow-up.”

Dr. Fink’s conclusion? “Bed nets protect you in the short run, and being protected in the short run is also beneficial in the long run. There is no evidence that protecting kids in early childhood is weakening them in any way. So we should keep doing this.”

Dr. Fink and Dr. Wilson report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It seems obvious that increased use of mosquito bed nets in sub-Saharan Africa would decrease the incidence of malaria, but a lingering question remained:

Malaria from Plasmodium falciparum infection exacts a significant toll in sub-Saharan Africa. According to the World Health Organization, there were about 228 million cases and 602,000 deaths from malaria in 2020 alone. About 80% of those deaths were in children less than 5 years old. In some areas, as many as 5% of children die from malaria by age 5.

Efforts to reduce the burden of malaria have been ongoing for decades. In the 1990s, insecticide-treated nets were shown to reduce illness and deaths from malaria in children.

As a result, the use of bed nets has grown significantly. In 2000, only 5% of households in sub-Saharan Africa had a net in the house. By 2020, that number had risen to 65%. From 2004 to 2019 about 1.9 billion nets were distributed in this region. The nets are estimated to have prevented more than 663 million malaria cases between 2000 and 2015.

As described in the NEJM report, public health researchers conducted a 22-year prospective longitudinal cohort study in rural southern Tanzania following 6,706 children born between 1998 and 2000. Initially, home visits were made every 4 months from May 1998 to April 2003. Remarkably, in 2019, they were able to verify the status of fully 89% of those people by reaching out to families and community/village leaders.

Günther Fink, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology and household economics, University of Basel (Switzerland), explained the approach and primary findings to this news organization. The analysis looked at three main groups – children whose parents said they always slept under treated nets, those who slept protected most of the time, and those who spent less than half the time under bed nets. The hazard ratio for death was 0.57 (95% confidence interval, 0.45-0.72) for the first two groups, compared with the least protected. The corresponding hazard ratio between age 5 and adulthood was 0.93 (95% CI, 0.58-1.49).

The findings confirmed what they had suspected. Dr. Fink summarized simply, “If you always slept under a net, you did much better than if you never slept under the net. If you slept [under a net] more than half of the time, it was much better than if you slept [under a net] less than half the time.” So the more time children slept under bed nets, the less likely they were to acquire malaria. Dr. Fink stressed that the findings showing protective efficacy persisted into adulthood. “It seems just having a healthier early life actually makes you more resilient against other future infections.”

One of the theoretical concerns was that using nets would delay developing functional immunity and that there might be an increase in mortality seen later. This study showed that did not happen.

An accompanying commentary noted that there was some potential that families receiving nets were better off than those that didn’t but concluded that such confounding had been accounted for in other analyses.

Mark Wilson, ScD, professor emeritus of epidemiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, concurred. He told this news organization that the study was “very well designed,” and the researchers “did a fantastic job” in tracking patients 20 years later.

“This is astounding!” he added. “It’s very rare to find this amount of follow-up.”

Dr. Fink’s conclusion? “Bed nets protect you in the short run, and being protected in the short run is also beneficial in the long run. There is no evidence that protecting kids in early childhood is weakening them in any way. So we should keep doing this.”

Dr. Fink and Dr. Wilson report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Drug-resistant malaria is emerging in Africa. Is the world ready?

In June 2017, Betty Balikagala, MD, PhD, traveled to a hospital in Gulu District, in northern Uganda. It was the rainy season: a peak time for malaria transmission. Dr. Balikagala, a researcher at Juntendo University in Japan, was back in her home country to hunt for mutations in the parasite that causes the disease.

For about 4 weeks, Dr. Balikagala and her colleagues collected blood from infected patients as they were treated with a powerful cocktail of antimalarial drugs. After initial analysis, the team then shipped their samples – glass slides smeared with blood, and filter papers with blood spots – back to Japan.

In their lab at Juntendo University, they looked for traces of malaria in the blood slides, which they had prepared by drawing blood from patients every few hours. In previous years, Dr. Balikagala and her colleagues had observed the drugs efficiently clearing the infection. This time, though, the parasite lingered in some patients. “We were very surprised when we first did the parasite reading for 2017, and we noticed that there were some patients who had delayed clearance,” recalled Dr. Balikagala. “For me, it was a shock.”

Malaria kills more than half a million people per year, most of them small children. Still, between 2000 and 2020, according to the World Health Organization, interventions prevented around 10.6 million malaria deaths, mostly in Africa. Bed nets and insecticides were responsible for most of the progress. But a fairly large number of lives were also saved by a new kind of antimalarial treatment: artemisinin-based combination therapies, or ACTs, that replaced older drugs such as chloroquine.

Used as a first-line treatment, ACTs have averted a significant number of malaria deaths since their introduction in the early 2000s. ACTs pair a derivative of the drug artemisinin with one of five partner drugs or drug combinations. Delivered together, the fast-acting artemisinin component wipes out most of the parasites within a few days, and the longer-acting partner drug clears out the stragglers.

ACTs quickly became a mainstay in malaria treatment. But in 2009, researchers observed signs of resistance to artemisinin along the Thailand-Cambodia border. The artemisinin component failed to clear the parasite quickly, which meant that the partner drug had to pick up that load, creating favorable conditions for partner drug resistance, too. The Greater Mekong Subregion now experiences high rates of multidrug resistance. Scientists have feared that the spread of such resistance to Africa, which accounts for more than 90% of global malaria cases, would be disastrous.

Now, in a pair of reports published last year, scientists have confirmed the emergence of artemisinin resistance in Africa. One study, published in April, reported that ACTs had failed to work quickly for more than 10% of participants at two sites in Rwanda. The prevalence of artemisinin resistance mutations was also higher than detected in previous reports.

In September, Dr. Balikagala’s team published the report from Uganda, which also identified mutations associated with artemisinin resistance. Alarmingly, the resistant malaria parasites had risen from 3.9% of cases in 2015 to nearly 20% in 2019. Genetic analysis shows that the resistance mutations in Rwanda and Uganda have emerged independently.

The latest malaria report from the WHO, published in December, also noted worrying signs of artemisinin resistance in the Horn of Africa, on the eastern side of the continent. No peer-reviewed studies confirming such resistance have been published.

So far, the ACTs still work. But in an experimental setting, as drug resistance sets in, it can lengthen treatment by 3 or 4 days. That may not sound like much, said Timothy Wells, PhD, chief scientific officer of the nonprofit Medicines for Malaria Venture. But “the more days of therapy you need,” he said, “then the more there is the risk that people don’t finish their course of therapy.” Dropping a treatment course midway exposes the parasites to the drug, but doesn’t clear all of them, potentially leaving behind survivors with a higher chance of being drug resistant. “That’s really bad news, because then that sets up a perfect storm for creating more resistance,” said Dr. Wells.

The reports from Uganda and Rwanda have yielded a grim consensus: “We are going to see more and more of such independent emergence,” said Pascal Ringwald, MD, PhD, coordinator at the director’s office for the WHO Global Malaria Program. “This is exactly what we saw in the Greater Mekong.” Luckily, Dr. Wells said, switching to other ACTs helped to combat resistance when it was detected there, avoiding the need for prolonged treatment.

A new malaria vaccine, which recently received the go-ahead from the WHO, may eventually help reduce the number of infections, but its rollout won’t have any significant impact on drug resistance. As for new drugs, even the most promising candidate in the pipeline would take at least 4 years to become widely available.

That leaves public health workers in Africa with only one solid option: Track and surveil resistance to artemisinin and its partner drugs. Effective surveillance systems, experts say, need to ramp up quickly and widely across the continent.

But most experts say that surveillance on the continent is patchy. Indeed, there is considerable uncertainty about how widespread antimalarial resistance already is in sub-Saharan Africa – and disagreement over how to interpret initial reports of emerging partner drug resistance in some countries.

“Our current systems are not as good as they should be,” said Philip Rosenthal, MD, a malaria researcher at the University of California, San Francisco. The new reports of artemisinin resistance, he added, “can be seen as a wake-up call to improve surveillance.”

Malaria drugs have failed before. In the early 20th century, chloroquine helped beat back the pathogen worldwide. Then, about a decade after World War II, resistance to chloroquine surfaced along the Thailand-Cambodia border.

By the 1970s, chloroquine-resistant malaria had spread across India and into Africa, where it killed millions, many of them children. “In retrospect, we know that chloroquine was used for many years after there was a huge resistance problem,” said Dr. Rosenthal. “This probably led to millions of excess deaths that could have been avoided if we were using other drugs.”

The scurry to find new drugs yielded artemisinin. Used by Chinese herbalists some 2,000 years ago to treat malaria-like symptoms, artemisinin was rediscovered in the 1970s by biomedical researchers in China, and its use became widespread in the 2000s.

Haunted by the failure of chloroquine, though, researchers have remained on the lookout for signs that the malaria parasite is evolving to resist artemisinin or its partner drugs. The gold-standard method is a therapeutic efficacy study, which involves closely monitoring infected patients as they are treated with antimalarial drugs, to see how well the drugs perform and if there are any signs of resistance.

The WHO recommends conducting these studies at several sites in a country every 2 years. But “each country interprets that with their capability,” said Philippe Guérin, MD, PhD, director of the WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network at the University of Oxford, England. Efficacy studies are slow, costly, and labor intensive. Also, “you don’t get a very good geographical representation,” said Dr. Guérin, because you can do a new clinical trial in only so many places at a time.

To get around the problems associated with efficacy studies, researchers also turn to molecular surveillance. Researchers draw a few drops of blood from an infected individual onto a filter paper, then scan it in the laboratory for certain genetic mutations associated with resistance. The technique is relatively easy and cheap.

With these kinds of surveillance data, policymakers can choose which drugs to use in a particular region. Moreover, early detection of resistance can prompt health authorities to take actions to limit the spread of resistance, including more aggressive screening and treatment campaigns, and expanded efforts to control the mosquitoes that spread malaria.

In practice, though, this warning system is frayed. “There is really no organized surveillance system for the continent,” said Dr. Rosenthal. “Surveillance is haphazard.”

In countries lacking a robust health care system or mired in political instability, experts say, resistance could be spreading undetected. For example, the border of South Sudan is just 60 miles from the site in northern Uganda where Dr. Balikagala and her colleagues confirmed resistance to artemisinin. “Because of the security issues and the refugee-weakened system, there is no surveillance that tells us what is happening in South Sudan,” said Dr. Guérin. The same applies in some parts of the nearby Democratic Republic of the Congo, he added.

In the past, regional antimalarial networks, such as the now defunct East African Network for Monitoring of Antimalarial Treatment, have addressed some surveillance gaps. These networks can help standardize protocols and coordinate surveillance efforts. But such networks have suffered from recent lapses in donor funding. The East African network “will be awakened,” Dr. Balikagala predicted, as concerns about artemisinin-resistant malaria grow.

In southern Africa, eight countries have come together to form the Elimination Eight Initiative, a coalition to facilitate malaria elimination efforts across national borders, which may help jump-start surveillance efforts there.

Dr. Ringwald said drug resistance is a priority for him and his WHO colleagues. At a malaria policy advisory committee meeting last fall, he said, the issue was “high on the agenda.” However, when pressed for answers on how the WHO plans to combat drug resistance in Africa, Dr. Ringwald emailed Undark an excerpt from the organization’s 2021 World Malaria Report. The report states that the WHO will “work with countries to develop a regional plan for a coordinated response,” but does not lay out any specifics on that response plan. The Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, part of the African Union, did not respond to requests for comment on its plans to bolster surveillance.

“There is an ethical obligation to researchers, and to people responsible for surveillance, that if you pick up these problems, share them as quickly as possible, react to them as strongly as possible,” said Karen Barnes, a clinical pharmacologist at the University of Cape Town who cochairs the South African Malaria Elimination Committee. “And try very, very hard” to make sure “that it’s not going to be the same as when we had chloroquine resistance in Africa.”

In absence of more robust surveillance, reports have also identified worrying – but, some scientists say, inconclusive – signs of partner drug resistance.

A series of four studies conducted between 2013 and 2019 at several sites in Angola found the efficacy of artemether-lumefantrine – the most widely used ACT in Africa – had dropped below 90%, the WHO threshold for acceptable malaria treatment. Peer-reviewed studies from Burkina Faso and the Democratic Republic of the Congo have reported similar results.

The studies have not found genes associated with artemisinin resistance, suggesting that the partner drug, lumefantrine, might be faltering. But several malaria researchers told Undark they were skeptical of the studies’ methods and viewed the results as preliminary. “I would have preferred that we look at data with a standardized protocol and exclude any confounding factors like poor microscopy or analytical method,” said Dr. Ringwald.

Mateusz Plucinski, PhD, an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Malaria Branch who participated in the Angola research, defended the findings. “The persistence of artemether-lumefantrine efficacy near or under 90% in Angola likely suggests that there is likely a true signal of decreased susceptibility of parasites to this drug,” he wrote in an email to this news organization. In response to the data, Angolan health officials have begun using a different ACT.

For now, it’s unclear how bad the situation is in Africa – or what the years ahead could bring. The research community and the authorities are “at the level of just watching and seeing what happens at this stage,” said Leann Tilley, PhD, a biochemist at the University of Melbourne who researches antimalarial resistance. But experts say that if artemisinin resistance does flare up and starts impinging on the partner drug, policymakers might need to consider changing to a different ACT, or even deploy triple ACTs, with two partner drugs.

Some experts are hopeful that artemisinin resistance will spread more slowly in Africa than it has in southeast Asia. But if high-grade resistance to artemisinin and partner drugs were to arise, it would put Africa in a bind. There are no immediate replacements for ACTs at the moment. The Medicines for Malaria Venture drug pipeline has about 30 molecules that show promise in preliminary testing, and about 15 molecules that are undergoing clinical trials for efficacy and safety, said Dr. Wells. But even the drugs that are at the end of the pipeline will take about 5-6 years from approval by regulatory authorities to be incorporated into WHO guidelines, he noted – if they make it through trials at all.

Dr. Wells cited one promising compound, from the drug maker Novartis, that recently performed well in early clinical trials. Still, Dr. Wells said, the drug won’t be ready to be deployed in Africa until around 2026.

Funds for malaria control and elimination programs remain limited, and scientists worry that, between COVID-19 and the malaria vaccine rollout, attention and resources for conducting surveillance and drug resistance work might dry up. “I really hope that those that do have resources available will understand that investing in Africa’s response to artemisinin resistance today, preferably yesterday, is probably one of the best places that they can put their money,” said Barnes.

The annals of malaria have shown time and again that once resistance emerges, it spreads widely and imperils progress against the deadly disease. For Africa, the writing is on the wall, she said. The bigger question, she asked, is this: “Are we capable of learning from history?”

A version of this article first appeared on Undark.com.

In June 2017, Betty Balikagala, MD, PhD, traveled to a hospital in Gulu District, in northern Uganda. It was the rainy season: a peak time for malaria transmission. Dr. Balikagala, a researcher at Juntendo University in Japan, was back in her home country to hunt for mutations in the parasite that causes the disease.

For about 4 weeks, Dr. Balikagala and her colleagues collected blood from infected patients as they were treated with a powerful cocktail of antimalarial drugs. After initial analysis, the team then shipped their samples – glass slides smeared with blood, and filter papers with blood spots – back to Japan.

In their lab at Juntendo University, they looked for traces of malaria in the blood slides, which they had prepared by drawing blood from patients every few hours. In previous years, Dr. Balikagala and her colleagues had observed the drugs efficiently clearing the infection. This time, though, the parasite lingered in some patients. “We were very surprised when we first did the parasite reading for 2017, and we noticed that there were some patients who had delayed clearance,” recalled Dr. Balikagala. “For me, it was a shock.”

Malaria kills more than half a million people per year, most of them small children. Still, between 2000 and 2020, according to the World Health Organization, interventions prevented around 10.6 million malaria deaths, mostly in Africa. Bed nets and insecticides were responsible for most of the progress. But a fairly large number of lives were also saved by a new kind of antimalarial treatment: artemisinin-based combination therapies, or ACTs, that replaced older drugs such as chloroquine.

Used as a first-line treatment, ACTs have averted a significant number of malaria deaths since their introduction in the early 2000s. ACTs pair a derivative of the drug artemisinin with one of five partner drugs or drug combinations. Delivered together, the fast-acting artemisinin component wipes out most of the parasites within a few days, and the longer-acting partner drug clears out the stragglers.

ACTs quickly became a mainstay in malaria treatment. But in 2009, researchers observed signs of resistance to artemisinin along the Thailand-Cambodia border. The artemisinin component failed to clear the parasite quickly, which meant that the partner drug had to pick up that load, creating favorable conditions for partner drug resistance, too. The Greater Mekong Subregion now experiences high rates of multidrug resistance. Scientists have feared that the spread of such resistance to Africa, which accounts for more than 90% of global malaria cases, would be disastrous.

Now, in a pair of reports published last year, scientists have confirmed the emergence of artemisinin resistance in Africa. One study, published in April, reported that ACTs had failed to work quickly for more than 10% of participants at two sites in Rwanda. The prevalence of artemisinin resistance mutations was also higher than detected in previous reports.

In September, Dr. Balikagala’s team published the report from Uganda, which also identified mutations associated with artemisinin resistance. Alarmingly, the resistant malaria parasites had risen from 3.9% of cases in 2015 to nearly 20% in 2019. Genetic analysis shows that the resistance mutations in Rwanda and Uganda have emerged independently.

The latest malaria report from the WHO, published in December, also noted worrying signs of artemisinin resistance in the Horn of Africa, on the eastern side of the continent. No peer-reviewed studies confirming such resistance have been published.

So far, the ACTs still work. But in an experimental setting, as drug resistance sets in, it can lengthen treatment by 3 or 4 days. That may not sound like much, said Timothy Wells, PhD, chief scientific officer of the nonprofit Medicines for Malaria Venture. But “the more days of therapy you need,” he said, “then the more there is the risk that people don’t finish their course of therapy.” Dropping a treatment course midway exposes the parasites to the drug, but doesn’t clear all of them, potentially leaving behind survivors with a higher chance of being drug resistant. “That’s really bad news, because then that sets up a perfect storm for creating more resistance,” said Dr. Wells.

The reports from Uganda and Rwanda have yielded a grim consensus: “We are going to see more and more of such independent emergence,” said Pascal Ringwald, MD, PhD, coordinator at the director’s office for the WHO Global Malaria Program. “This is exactly what we saw in the Greater Mekong.” Luckily, Dr. Wells said, switching to other ACTs helped to combat resistance when it was detected there, avoiding the need for prolonged treatment.

A new malaria vaccine, which recently received the go-ahead from the WHO, may eventually help reduce the number of infections, but its rollout won’t have any significant impact on drug resistance. As for new drugs, even the most promising candidate in the pipeline would take at least 4 years to become widely available.

That leaves public health workers in Africa with only one solid option: Track and surveil resistance to artemisinin and its partner drugs. Effective surveillance systems, experts say, need to ramp up quickly and widely across the continent.

But most experts say that surveillance on the continent is patchy. Indeed, there is considerable uncertainty about how widespread antimalarial resistance already is in sub-Saharan Africa – and disagreement over how to interpret initial reports of emerging partner drug resistance in some countries.

“Our current systems are not as good as they should be,” said Philip Rosenthal, MD, a malaria researcher at the University of California, San Francisco. The new reports of artemisinin resistance, he added, “can be seen as a wake-up call to improve surveillance.”

Malaria drugs have failed before. In the early 20th century, chloroquine helped beat back the pathogen worldwide. Then, about a decade after World War II, resistance to chloroquine surfaced along the Thailand-Cambodia border.

By the 1970s, chloroquine-resistant malaria had spread across India and into Africa, where it killed millions, many of them children. “In retrospect, we know that chloroquine was used for many years after there was a huge resistance problem,” said Dr. Rosenthal. “This probably led to millions of excess deaths that could have been avoided if we were using other drugs.”

The scurry to find new drugs yielded artemisinin. Used by Chinese herbalists some 2,000 years ago to treat malaria-like symptoms, artemisinin was rediscovered in the 1970s by biomedical researchers in China, and its use became widespread in the 2000s.

Haunted by the failure of chloroquine, though, researchers have remained on the lookout for signs that the malaria parasite is evolving to resist artemisinin or its partner drugs. The gold-standard method is a therapeutic efficacy study, which involves closely monitoring infected patients as they are treated with antimalarial drugs, to see how well the drugs perform and if there are any signs of resistance.

The WHO recommends conducting these studies at several sites in a country every 2 years. But “each country interprets that with their capability,” said Philippe Guérin, MD, PhD, director of the WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network at the University of Oxford, England. Efficacy studies are slow, costly, and labor intensive. Also, “you don’t get a very good geographical representation,” said Dr. Guérin, because you can do a new clinical trial in only so many places at a time.

To get around the problems associated with efficacy studies, researchers also turn to molecular surveillance. Researchers draw a few drops of blood from an infected individual onto a filter paper, then scan it in the laboratory for certain genetic mutations associated with resistance. The technique is relatively easy and cheap.

With these kinds of surveillance data, policymakers can choose which drugs to use in a particular region. Moreover, early detection of resistance can prompt health authorities to take actions to limit the spread of resistance, including more aggressive screening and treatment campaigns, and expanded efforts to control the mosquitoes that spread malaria.

In practice, though, this warning system is frayed. “There is really no organized surveillance system for the continent,” said Dr. Rosenthal. “Surveillance is haphazard.”

In countries lacking a robust health care system or mired in political instability, experts say, resistance could be spreading undetected. For example, the border of South Sudan is just 60 miles from the site in northern Uganda where Dr. Balikagala and her colleagues confirmed resistance to artemisinin. “Because of the security issues and the refugee-weakened system, there is no surveillance that tells us what is happening in South Sudan,” said Dr. Guérin. The same applies in some parts of the nearby Democratic Republic of the Congo, he added.

In the past, regional antimalarial networks, such as the now defunct East African Network for Monitoring of Antimalarial Treatment, have addressed some surveillance gaps. These networks can help standardize protocols and coordinate surveillance efforts. But such networks have suffered from recent lapses in donor funding. The East African network “will be awakened,” Dr. Balikagala predicted, as concerns about artemisinin-resistant malaria grow.

In southern Africa, eight countries have come together to form the Elimination Eight Initiative, a coalition to facilitate malaria elimination efforts across national borders, which may help jump-start surveillance efforts there.

Dr. Ringwald said drug resistance is a priority for him and his WHO colleagues. At a malaria policy advisory committee meeting last fall, he said, the issue was “high on the agenda.” However, when pressed for answers on how the WHO plans to combat drug resistance in Africa, Dr. Ringwald emailed Undark an excerpt from the organization’s 2021 World Malaria Report. The report states that the WHO will “work with countries to develop a regional plan for a coordinated response,” but does not lay out any specifics on that response plan. The Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, part of the African Union, did not respond to requests for comment on its plans to bolster surveillance.

“There is an ethical obligation to researchers, and to people responsible for surveillance, that if you pick up these problems, share them as quickly as possible, react to them as strongly as possible,” said Karen Barnes, a clinical pharmacologist at the University of Cape Town who cochairs the South African Malaria Elimination Committee. “And try very, very hard” to make sure “that it’s not going to be the same as when we had chloroquine resistance in Africa.”

In absence of more robust surveillance, reports have also identified worrying – but, some scientists say, inconclusive – signs of partner drug resistance.

A series of four studies conducted between 2013 and 2019 at several sites in Angola found the efficacy of artemether-lumefantrine – the most widely used ACT in Africa – had dropped below 90%, the WHO threshold for acceptable malaria treatment. Peer-reviewed studies from Burkina Faso and the Democratic Republic of the Congo have reported similar results.

The studies have not found genes associated with artemisinin resistance, suggesting that the partner drug, lumefantrine, might be faltering. But several malaria researchers told Undark they were skeptical of the studies’ methods and viewed the results as preliminary. “I would have preferred that we look at data with a standardized protocol and exclude any confounding factors like poor microscopy or analytical method,” said Dr. Ringwald.

Mateusz Plucinski, PhD, an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Malaria Branch who participated in the Angola research, defended the findings. “The persistence of artemether-lumefantrine efficacy near or under 90% in Angola likely suggests that there is likely a true signal of decreased susceptibility of parasites to this drug,” he wrote in an email to this news organization. In response to the data, Angolan health officials have begun using a different ACT.

For now, it’s unclear how bad the situation is in Africa – or what the years ahead could bring. The research community and the authorities are “at the level of just watching and seeing what happens at this stage,” said Leann Tilley, PhD, a biochemist at the University of Melbourne who researches antimalarial resistance. But experts say that if artemisinin resistance does flare up and starts impinging on the partner drug, policymakers might need to consider changing to a different ACT, or even deploy triple ACTs, with two partner drugs.

Some experts are hopeful that artemisinin resistance will spread more slowly in Africa than it has in southeast Asia. But if high-grade resistance to artemisinin and partner drugs were to arise, it would put Africa in a bind. There are no immediate replacements for ACTs at the moment. The Medicines for Malaria Venture drug pipeline has about 30 molecules that show promise in preliminary testing, and about 15 molecules that are undergoing clinical trials for efficacy and safety, said Dr. Wells. But even the drugs that are at the end of the pipeline will take about 5-6 years from approval by regulatory authorities to be incorporated into WHO guidelines, he noted – if they make it through trials at all.

Dr. Wells cited one promising compound, from the drug maker Novartis, that recently performed well in early clinical trials. Still, Dr. Wells said, the drug won’t be ready to be deployed in Africa until around 2026.

Funds for malaria control and elimination programs remain limited, and scientists worry that, between COVID-19 and the malaria vaccine rollout, attention and resources for conducting surveillance and drug resistance work might dry up. “I really hope that those that do have resources available will understand that investing in Africa’s response to artemisinin resistance today, preferably yesterday, is probably one of the best places that they can put their money,” said Barnes.

The annals of malaria have shown time and again that once resistance emerges, it spreads widely and imperils progress against the deadly disease. For Africa, the writing is on the wall, she said. The bigger question, she asked, is this: “Are we capable of learning from history?”

A version of this article first appeared on Undark.com.

In June 2017, Betty Balikagala, MD, PhD, traveled to a hospital in Gulu District, in northern Uganda. It was the rainy season: a peak time for malaria transmission. Dr. Balikagala, a researcher at Juntendo University in Japan, was back in her home country to hunt for mutations in the parasite that causes the disease.

For about 4 weeks, Dr. Balikagala and her colleagues collected blood from infected patients as they were treated with a powerful cocktail of antimalarial drugs. After initial analysis, the team then shipped their samples – glass slides smeared with blood, and filter papers with blood spots – back to Japan.

In their lab at Juntendo University, they looked for traces of malaria in the blood slides, which they had prepared by drawing blood from patients every few hours. In previous years, Dr. Balikagala and her colleagues had observed the drugs efficiently clearing the infection. This time, though, the parasite lingered in some patients. “We were very surprised when we first did the parasite reading for 2017, and we noticed that there were some patients who had delayed clearance,” recalled Dr. Balikagala. “For me, it was a shock.”

Malaria kills more than half a million people per year, most of them small children. Still, between 2000 and 2020, according to the World Health Organization, interventions prevented around 10.6 million malaria deaths, mostly in Africa. Bed nets and insecticides were responsible for most of the progress. But a fairly large number of lives were also saved by a new kind of antimalarial treatment: artemisinin-based combination therapies, or ACTs, that replaced older drugs such as chloroquine.

Used as a first-line treatment, ACTs have averted a significant number of malaria deaths since their introduction in the early 2000s. ACTs pair a derivative of the drug artemisinin with one of five partner drugs or drug combinations. Delivered together, the fast-acting artemisinin component wipes out most of the parasites within a few days, and the longer-acting partner drug clears out the stragglers.

ACTs quickly became a mainstay in malaria treatment. But in 2009, researchers observed signs of resistance to artemisinin along the Thailand-Cambodia border. The artemisinin component failed to clear the parasite quickly, which meant that the partner drug had to pick up that load, creating favorable conditions for partner drug resistance, too. The Greater Mekong Subregion now experiences high rates of multidrug resistance. Scientists have feared that the spread of such resistance to Africa, which accounts for more than 90% of global malaria cases, would be disastrous.

Now, in a pair of reports published last year, scientists have confirmed the emergence of artemisinin resistance in Africa. One study, published in April, reported that ACTs had failed to work quickly for more than 10% of participants at two sites in Rwanda. The prevalence of artemisinin resistance mutations was also higher than detected in previous reports.

In September, Dr. Balikagala’s team published the report from Uganda, which also identified mutations associated with artemisinin resistance. Alarmingly, the resistant malaria parasites had risen from 3.9% of cases in 2015 to nearly 20% in 2019. Genetic analysis shows that the resistance mutations in Rwanda and Uganda have emerged independently.

The latest malaria report from the WHO, published in December, also noted worrying signs of artemisinin resistance in the Horn of Africa, on the eastern side of the continent. No peer-reviewed studies confirming such resistance have been published.

So far, the ACTs still work. But in an experimental setting, as drug resistance sets in, it can lengthen treatment by 3 or 4 days. That may not sound like much, said Timothy Wells, PhD, chief scientific officer of the nonprofit Medicines for Malaria Venture. But “the more days of therapy you need,” he said, “then the more there is the risk that people don’t finish their course of therapy.” Dropping a treatment course midway exposes the parasites to the drug, but doesn’t clear all of them, potentially leaving behind survivors with a higher chance of being drug resistant. “That’s really bad news, because then that sets up a perfect storm for creating more resistance,” said Dr. Wells.

The reports from Uganda and Rwanda have yielded a grim consensus: “We are going to see more and more of such independent emergence,” said Pascal Ringwald, MD, PhD, coordinator at the director’s office for the WHO Global Malaria Program. “This is exactly what we saw in the Greater Mekong.” Luckily, Dr. Wells said, switching to other ACTs helped to combat resistance when it was detected there, avoiding the need for prolonged treatment.

A new malaria vaccine, which recently received the go-ahead from the WHO, may eventually help reduce the number of infections, but its rollout won’t have any significant impact on drug resistance. As for new drugs, even the most promising candidate in the pipeline would take at least 4 years to become widely available.

That leaves public health workers in Africa with only one solid option: Track and surveil resistance to artemisinin and its partner drugs. Effective surveillance systems, experts say, need to ramp up quickly and widely across the continent.

But most experts say that surveillance on the continent is patchy. Indeed, there is considerable uncertainty about how widespread antimalarial resistance already is in sub-Saharan Africa – and disagreement over how to interpret initial reports of emerging partner drug resistance in some countries.

“Our current systems are not as good as they should be,” said Philip Rosenthal, MD, a malaria researcher at the University of California, San Francisco. The new reports of artemisinin resistance, he added, “can be seen as a wake-up call to improve surveillance.”

Malaria drugs have failed before. In the early 20th century, chloroquine helped beat back the pathogen worldwide. Then, about a decade after World War II, resistance to chloroquine surfaced along the Thailand-Cambodia border.

By the 1970s, chloroquine-resistant malaria had spread across India and into Africa, where it killed millions, many of them children. “In retrospect, we know that chloroquine was used for many years after there was a huge resistance problem,” said Dr. Rosenthal. “This probably led to millions of excess deaths that could have been avoided if we were using other drugs.”

The scurry to find new drugs yielded artemisinin. Used by Chinese herbalists some 2,000 years ago to treat malaria-like symptoms, artemisinin was rediscovered in the 1970s by biomedical researchers in China, and its use became widespread in the 2000s.

Haunted by the failure of chloroquine, though, researchers have remained on the lookout for signs that the malaria parasite is evolving to resist artemisinin or its partner drugs. The gold-standard method is a therapeutic efficacy study, which involves closely monitoring infected patients as they are treated with antimalarial drugs, to see how well the drugs perform and if there are any signs of resistance.

The WHO recommends conducting these studies at several sites in a country every 2 years. But “each country interprets that with their capability,” said Philippe Guérin, MD, PhD, director of the WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network at the University of Oxford, England. Efficacy studies are slow, costly, and labor intensive. Also, “you don’t get a very good geographical representation,” said Dr. Guérin, because you can do a new clinical trial in only so many places at a time.

To get around the problems associated with efficacy studies, researchers also turn to molecular surveillance. Researchers draw a few drops of blood from an infected individual onto a filter paper, then scan it in the laboratory for certain genetic mutations associated with resistance. The technique is relatively easy and cheap.

With these kinds of surveillance data, policymakers can choose which drugs to use in a particular region. Moreover, early detection of resistance can prompt health authorities to take actions to limit the spread of resistance, including more aggressive screening and treatment campaigns, and expanded efforts to control the mosquitoes that spread malaria.

In practice, though, this warning system is frayed. “There is really no organized surveillance system for the continent,” said Dr. Rosenthal. “Surveillance is haphazard.”

In countries lacking a robust health care system or mired in political instability, experts say, resistance could be spreading undetected. For example, the border of South Sudan is just 60 miles from the site in northern Uganda where Dr. Balikagala and her colleagues confirmed resistance to artemisinin. “Because of the security issues and the refugee-weakened system, there is no surveillance that tells us what is happening in South Sudan,” said Dr. Guérin. The same applies in some parts of the nearby Democratic Republic of the Congo, he added.

In the past, regional antimalarial networks, such as the now defunct East African Network for Monitoring of Antimalarial Treatment, have addressed some surveillance gaps. These networks can help standardize protocols and coordinate surveillance efforts. But such networks have suffered from recent lapses in donor funding. The East African network “will be awakened,” Dr. Balikagala predicted, as concerns about artemisinin-resistant malaria grow.

In southern Africa, eight countries have come together to form the Elimination Eight Initiative, a coalition to facilitate malaria elimination efforts across national borders, which may help jump-start surveillance efforts there.

Dr. Ringwald said drug resistance is a priority for him and his WHO colleagues. At a malaria policy advisory committee meeting last fall, he said, the issue was “high on the agenda.” However, when pressed for answers on how the WHO plans to combat drug resistance in Africa, Dr. Ringwald emailed Undark an excerpt from the organization’s 2021 World Malaria Report. The report states that the WHO will “work with countries to develop a regional plan for a coordinated response,” but does not lay out any specifics on that response plan. The Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, part of the African Union, did not respond to requests for comment on its plans to bolster surveillance.

“There is an ethical obligation to researchers, and to people responsible for surveillance, that if you pick up these problems, share them as quickly as possible, react to them as strongly as possible,” said Karen Barnes, a clinical pharmacologist at the University of Cape Town who cochairs the South African Malaria Elimination Committee. “And try very, very hard” to make sure “that it’s not going to be the same as when we had chloroquine resistance in Africa.”

In absence of more robust surveillance, reports have also identified worrying – but, some scientists say, inconclusive – signs of partner drug resistance.

A series of four studies conducted between 2013 and 2019 at several sites in Angola found the efficacy of artemether-lumefantrine – the most widely used ACT in Africa – had dropped below 90%, the WHO threshold for acceptable malaria treatment. Peer-reviewed studies from Burkina Faso and the Democratic Republic of the Congo have reported similar results.

The studies have not found genes associated with artemisinin resistance, suggesting that the partner drug, lumefantrine, might be faltering. But several malaria researchers told Undark they were skeptical of the studies’ methods and viewed the results as preliminary. “I would have preferred that we look at data with a standardized protocol and exclude any confounding factors like poor microscopy or analytical method,” said Dr. Ringwald.

Mateusz Plucinski, PhD, an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Malaria Branch who participated in the Angola research, defended the findings. “The persistence of artemether-lumefantrine efficacy near or under 90% in Angola likely suggests that there is likely a true signal of decreased susceptibility of parasites to this drug,” he wrote in an email to this news organization. In response to the data, Angolan health officials have begun using a different ACT.

For now, it’s unclear how bad the situation is in Africa – or what the years ahead could bring. The research community and the authorities are “at the level of just watching and seeing what happens at this stage,” said Leann Tilley, PhD, a biochemist at the University of Melbourne who researches antimalarial resistance. But experts say that if artemisinin resistance does flare up and starts impinging on the partner drug, policymakers might need to consider changing to a different ACT, or even deploy triple ACTs, with two partner drugs.

Some experts are hopeful that artemisinin resistance will spread more slowly in Africa than it has in southeast Asia. But if high-grade resistance to artemisinin and partner drugs were to arise, it would put Africa in a bind. There are no immediate replacements for ACTs at the moment. The Medicines for Malaria Venture drug pipeline has about 30 molecules that show promise in preliminary testing, and about 15 molecules that are undergoing clinical trials for efficacy and safety, said Dr. Wells. But even the drugs that are at the end of the pipeline will take about 5-6 years from approval by regulatory authorities to be incorporated into WHO guidelines, he noted – if they make it through trials at all.

Dr. Wells cited one promising compound, from the drug maker Novartis, that recently performed well in early clinical trials. Still, Dr. Wells said, the drug won’t be ready to be deployed in Africa until around 2026.

Funds for malaria control and elimination programs remain limited, and scientists worry that, between COVID-19 and the malaria vaccine rollout, attention and resources for conducting surveillance and drug resistance work might dry up. “I really hope that those that do have resources available will understand that investing in Africa’s response to artemisinin resistance today, preferably yesterday, is probably one of the best places that they can put their money,” said Barnes.

The annals of malaria have shown time and again that once resistance emerges, it spreads widely and imperils progress against the deadly disease. For Africa, the writing is on the wall, she said. The bigger question, she asked, is this: “Are we capable of learning from history?”

A version of this article first appeared on Undark.com.

Antimicrobial resistance linked to 1.2 million global deaths in 2019

More than HIV, more than malaria.

In terms of preventable deaths, 1.27 million people could have been saved if drug-resistant infections were replaced with infections susceptible to current antibiotics. Furthermore, 4.95 million fewer people would have died if drug-resistant infections were replaced by no infections, researchers estimated.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic took some focus off the AMR burden worldwide over the past 2 years, the urgency to address risk to public health did not ebb. In fact, based on the findings, the researchers noted that AMR is now a leading cause of death worldwide.

“If left unchecked, the spread of AMR could make many bacterial pathogens much more lethal in the future than they are today,” the researchers noted in the study, published online Jan. 20, 2022, in The Lancet.

“These findings are a warning signal that antibiotic resistance is placing pressure on health care systems and leading to significant health loss,” study author Kevin Ikuta, MD, MPH, told this news organization.

“We need to continue to adhere to and support infection prevention and control programs, be thoughtful about our antibiotic use, and advocate for increased funding to vaccine discovery and the antibiotic development pipeline,” added Dr. Ikuta, health sciences assistant clinical professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Although many investigators have studied AMR, this study is the largest in scope, covering 204 countries and territories and incorporating data on a comprehensive range of pathogens and pathogen-drug combinations.

Dr. Ikuta, lead author Christopher J.L. Murray, DPhil, and colleagues estimated the global burden of AMR using the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2019. They specifically looked at rates of death directly attributed to and separately those associated with resistance.

Regional differences

Broken down by 21 regions, Australasia had 6.5 deaths per 100,000 people attributable to AMR, the lowest rate reported. This region also had 28 deaths per 100,000 associated with AMR.

Researchers found the highest rates in western sub-Saharan Africa. Deaths attributable to AMR were 27.3 per 100,000 and associated death rate was 114.8 per 100,000.

Lower- and middle-income regions had the highest AMR death rates, although resistance remains a high-priority issue for high-income countries as well.

“It’s important to take a global perspective on resistant infections because we can learn about regions and countries that are experiencing the greatest burden, information that was previously unknown,” Dr. Ikuta said. “With these estimates policy makers can prioritize regions that are hotspots and would most benefit from additional interventions.”

Furthermore, the study emphasized the global nature of AMR. “We’ve seen over the last 2 years with COVID-19 that this sort of problem doesn’t respect country borders, and high rates of resistance in one location can spread across a region or spread globally pretty quickly,” Dr. Ikuta said.

Leading resistant infections

Lower respiratory and thorax infections, bloodstream infections, and intra-abdominal infections together accounted for almost 79% of such deaths linked to AMR.

The six leading pathogens are likely household names among infectious disease specialists. The researchers found Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, each responsible for more than 250,000 AMR-associated deaths.

The study also revealed that resistance to several first-line antibiotic agents often used empirically to treat infections accounted for more than 70% of the AMR-attributable deaths. These included fluoroquinolones and beta-lactam antibiotics such as carbapenems, cephalosporins, and penicillins.

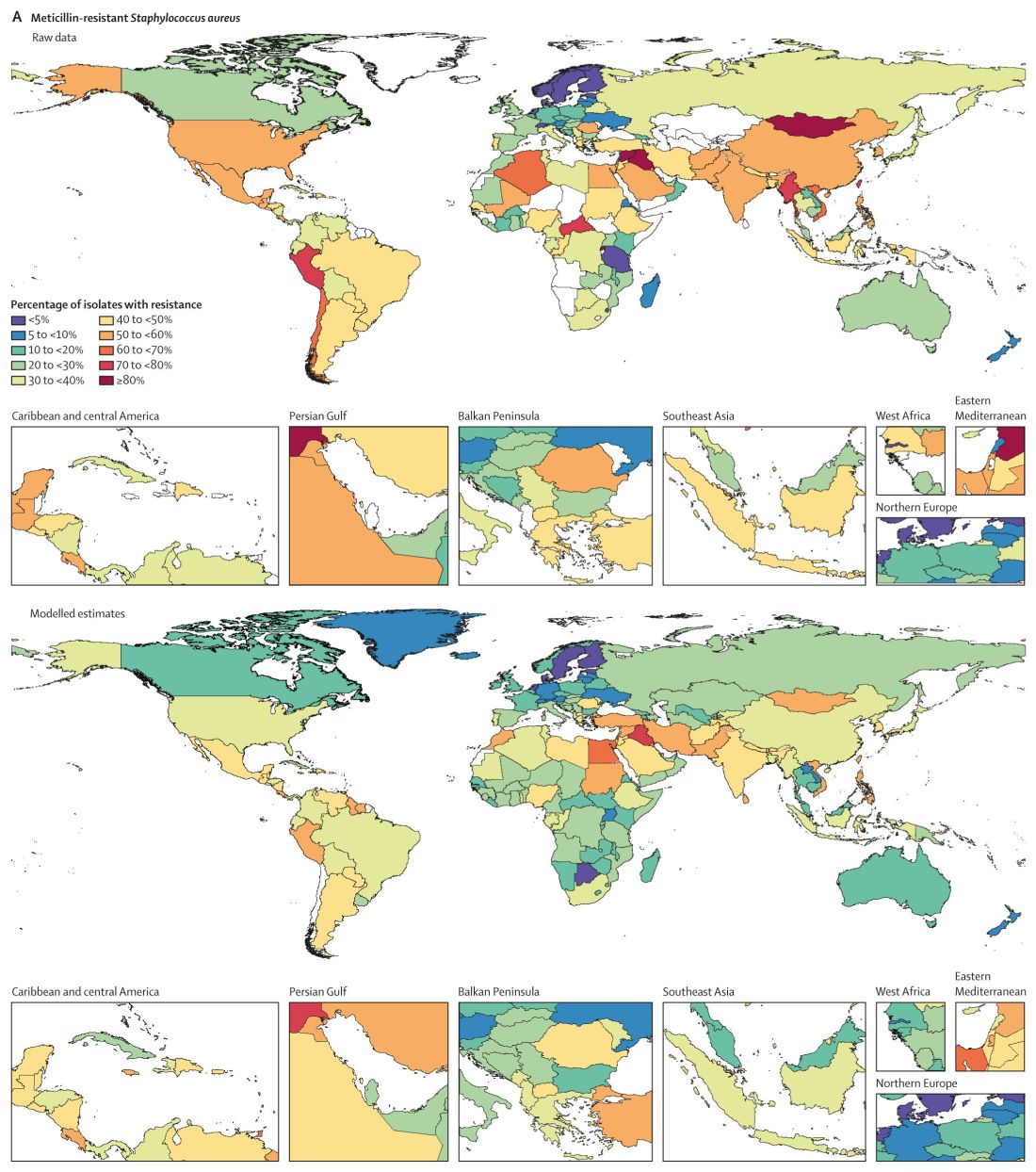

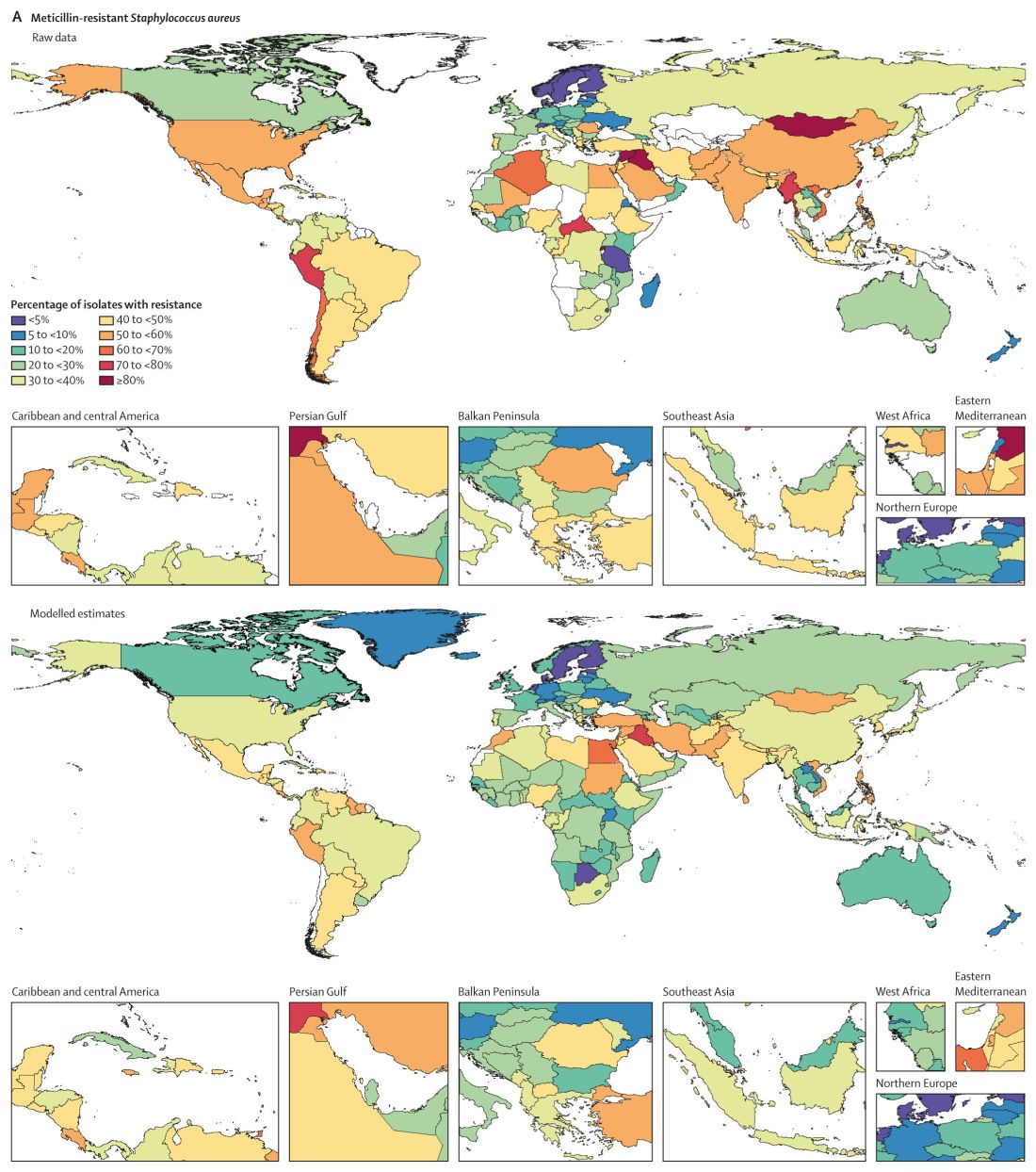

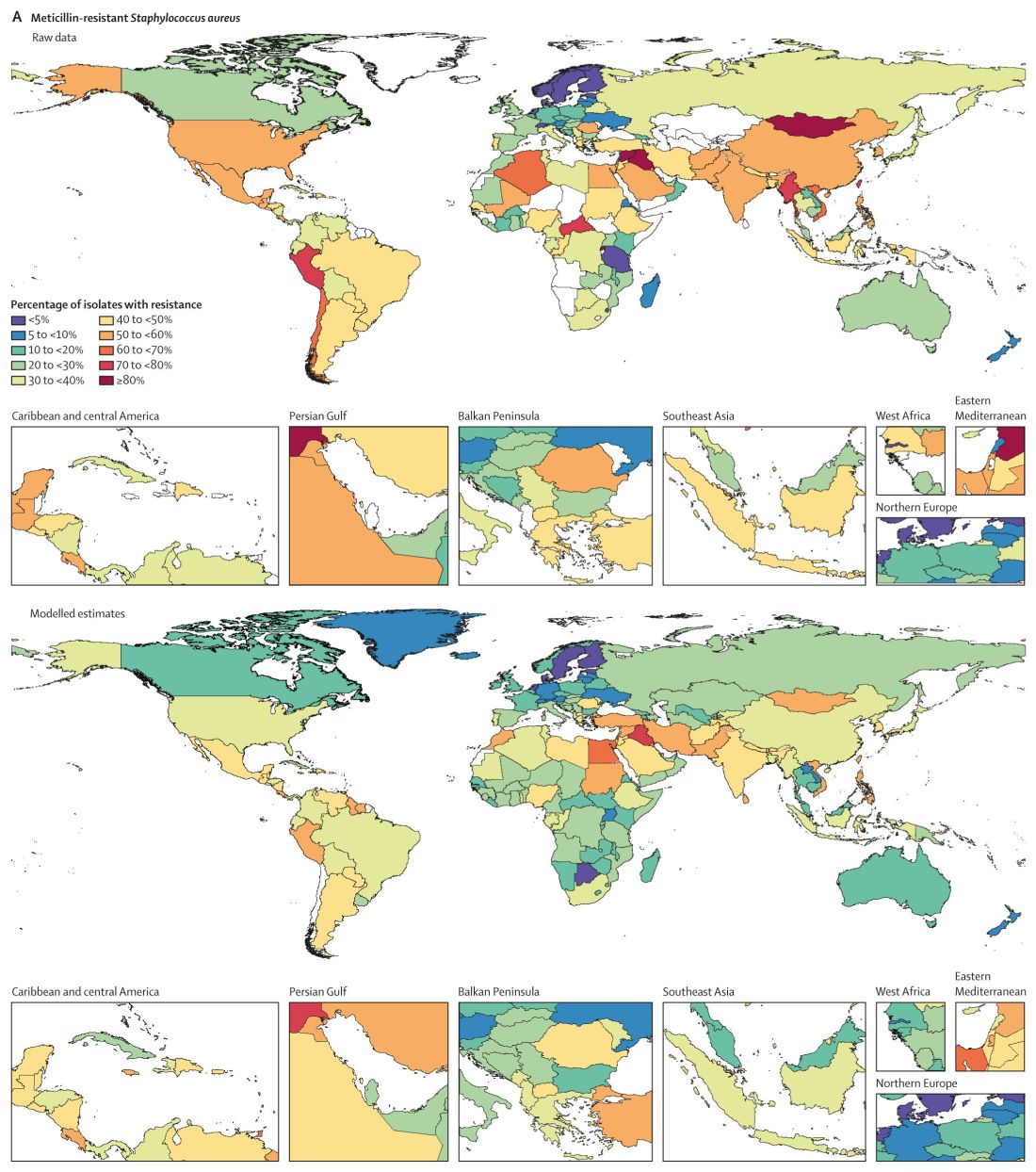

Consistent with previous studies, MRSA stood out as a major cause of mortality. Of 88 different pathogen-drug combinations evaluated, MRSA was responsible for the most mortality: more than 100,000 deaths and 3·5 million disability-adjusted life-years.

The current study findings on MRSA “being a particularly nasty culprit” in AMR infections validates previous work that reported similar results, Vance Fowler, MD, told this news organization when asked to comment on the research. “That is reassuring.”

Potential solutions offered

Dr. Murray and colleagues outlined five strategies to address the challenge of bacterial AMR:

- Infection prevention and control remain paramount in minimizing infections in general and AMR infections in particular.

- More vaccines are needed to reduce the need for antibiotics. “Vaccines are available for only one of the six leading pathogens (S. pneumoniae), although new vaccine programs are underway for S. aureus, E. coli, and others,” the researchers wrote.

- Reduce antibiotic use unrelated to treatment of human disease.

- Avoid using antibiotics for viral infections and other unnecessary indications.

- Invest in new antibiotic development and ensure access to second-line agents in areas without widespread access.

“Identifying strategies that can work to reduce the burden of bacterial AMR – either across a wide range of settings or those that are specifically tailored to the resources available and leading pathogen-drug combinations in a particular setting – is an urgent priority,” the researchers noted.

Admirable AMR research

The results of the study are “startling, but not surprising,” said Dr. Fowler, professor of medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

The authors did a “nice job” of addressing both deaths attributable and associated with AMR, Dr. Fowler added. “Those two categories unlock applications, not just in terms of how you interpret it but also what you do about it.”

The deaths attributable to AMR show that there is more work to be done regarding infection control and prevention, Dr. Fowler said, including in areas of the world like lower- and middle-income countries where infection resistance is most pronounced.

The deaths associated with AMR can be more challenging to calculate – people with infections can die for multiple reasons. However, Dr. Fowler applauded the researchers for doing “as good a job as you can” in estimating the extent of associated mortality.

‘The overlooked pandemic of antimicrobial resistance’

In an accompanying editorial in The Lancet, Ramanan Laxminarayan, PhD, MPH, wrote: “As COVID-19 rages on, the pandemic of antimicrobial resistance continues in the shadows. The toll taken by AMR on patients and their families is largely invisible but is reflected in prolonged bacterial infections that extend hospital stays and cause needless deaths.”

Dr. Laxminarayan pointed out an irony with AMR in different regions. Some of the AMR burden in sub-Saharan Africa is “probably due to inadequate access to antibiotics and high infection levels, albeit at low levels of resistance, whereas in south Asia and Latin America, it is because of high resistance even with good access to antibiotics.”