User login

Massive Baker Cyst Resulting in Tibial Nerve Compression Neuropathy Secondary to Polyethylene Wear Disease

Symptomatic synovial cyst formation is a rare, late occurrence after total knee arthroplasty (TKA); these cysts are generally discovered by chance. If they enlarge, they can result in significant pain and disability. A few case reports have described the development of very large cysts that required revision knee surgery. In this patient, polyethylene wear disease after TKA resulted in a massive synovial cyst that extended into the posterior compartment of the leg, as well as a progressive peripheral neuropathy. Revision of a loose patella component and worn polyethylene liner with complete synovectomy, plus decompression of the cyst via needle aspiration, resulted in an excellent short-term outcome.

To the author’s knowledge, this is the first case report of peripheral neuropathy of the tibial nerve secondary to a massive Baker cyst after total knee replacement. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

The patient was a 65-year-old woman with a complex medical history and multiple left knee surgeries, including a high tibial osteotomy and subsequent cemented TKA performed in the mid-1990s. She presented to the orthopedic department at a university hospital with complaints of knee pain 13 years after TKA. Observation was recommended; however, she was lost to follow-up.

The patient presented to her primary care physician (PCP) 16 years after TKA with a very large, painful mass in the back of her left leg. An ultrasound showed a large Baker cyst, and the patient was sent to interventional radiology. A few months later, she had an ultrasound-guided aspiration into the left calf, which produced 300 mL of thick synovial fluid. A cell count was not performed, but bacterial cultures were negative. Immediately after the aspiration, the pain was relieved.

Approximately 3 months after the aspiration, she presented again to her PCP with re-accumulation of fluid in the back of her left leg and severe leg pain. She was referred to a different orthopedic surgeon who determined that the risk of surgery was too great given her complex medical history.

The woman’s PCP referred the woman to our office 6 months after the aspiration. On presentation, her pain was localized to the posterior left leg. She reported the pain level as a constant 9 out of 10 on the visual analog scale, despite ingesting high doses of narcotics, including oxycontin and morphine. Her physical examination was remarkable for an ill-defined large calf mass. The posterior compartment of her left leg was firm and severely tender, similar to the characteristic findings seen in acute compartment syndrome.

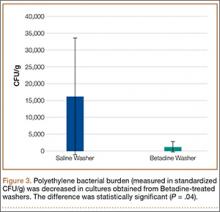

Radiographs showed evidence of asymmetric polyethylene wear on the medial side of the knee (Figures 1A, 1B). Serum labs were ordered to evaluate for infection. C-reactive protein was mildly elevated at 5.5 mg/L (normal range, 0-5 mg/L); however, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was normal at 12 mm/h (normal range, 0-20 mm/h). Magnetic resonance imaging of the left lower extremity with intravenous contrast showed the presence of a very large Baker cyst contained within the posterior compartment of the knee and a smaller surrounding cyst adjacent to the popliteal neurovascular bundle (Figure 2).

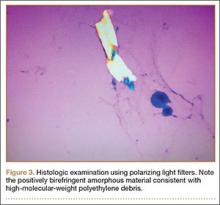

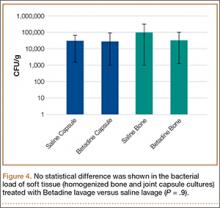

The Baker cyst was re-aspirated in the office. The automated synovial fluid cell count could not be performed because of high fluid viscosity. However, a manual review of the fluid specimen under light microscopy revealed proteinaceous, viscous tan-colored fluid containing no neutrophils and a few macrophages. Fluid cytology was also sent for review under polarizing light microscopy as described by Peterson and colleagues.1 Scattered fragments of polarizable foreign material were consistent with polyethylene debris (Figure 3).

The patient was counseled about the risks and benefits of surgery and was offered revision TKA with polyethylene liner exchange and synovectomy, only after complete cessation of smoking. She underwent serum nicotine monitoring to ensure tobacco cessation; however, she also reported the onset of a progressive sensory deficit over her left foot during this period. Although her medical history was remarkable for spinal stenosis, she noted a progressive decline in sensory function and new-onset paresthesia of her left foot.

An urgent consult to neurology was requested for nerve conduction studies. According to the electrodiagnostic study, the patient had a moderately severe left tibial neuropathy, likely at the popliteal fossa or distal to it. The nerve conduction study showed a chronic tibial nerve peripheral compressive mononeuropathy, and she was immediately scheduled for revision knee surgery with decompression of her Baker cyst to prevent further neurologic deficit.

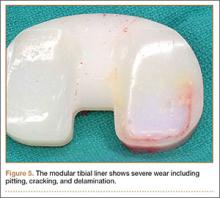

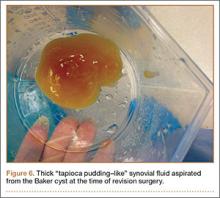

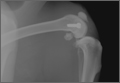

During surgery, the knee joint exhibited hypertrophic synovitis with a characteristic pale-yellowish discoloration secondary to significant polyethylene wear disease (Figure 4). The polyethylene liner was severely worn with pitting, cracking, and delamination (Figure 5). While the patellar component was grossly loose, the tibial and femoral components were stable. After a complete synovectomy, the loose patellar component and tibial polyethylene liner were replaced. Osteolytic areas within the tibia underwent curettage and allograft impaction grafting. Lastly, decompression of the ruptured Baker cyst was performed via a 16-gauge needle placed in the posterior compartment of the left leg. The calf was gently squeezed with a “milking” maneuver, which yielded approximately 200 mL of thick, mucoid yellowish-brown synovial fluid resembling tapioca pudding (Figure 6).

Postoperatively, all intraoperative cultures were negative, and the patient was followed closely at 1 week, 2 weeks, 6 weeks, and 3 months after the surgery. At her latest follow-up, the posterior leg compartment remained decompressed and her progressive sensory deficit had nearly resolved. Moreover, the left leg and posterior knee pain completely resolved.

Discussion

A leading cause of TKA failure is attributed to aseptic loosening from polyethylene wear disease.2 Implanted high-molecular-weight polyethylene (HMWPE) liners are known to undergo a variety of mechanical wear patterns within the knee. Observed patterns include pitting, scratching, burnishing, scratching, and delamination, which can all liberate numerous fine polyethylene particles.3 This wear debris induces macrophage phagocytosis that triggers an inflammatory reaction within the knee joint and can lead to synovitis, repeat effusions and, ultimately, to aseptic loosening.

Prior to 1996, polyethylene used in total knee replacement underwent a sterilization process in air. This oxygen-rich environment led to the development of free radical formation within the HMWPE. Ultimately, this had a detrimental effect on the polyethylene, leading to the formation of increased wear debris.4

Subsequently, orthopedic companies have changed their sterilization and manufacturing methods. Polyethylene components now undergo a variety of processes to eliminate or reduce oxidation, free-radical formation, and mechanical wear debris. Now, sterilization typically takes place in an inert atmospheric environment. Modern HMWPE implants often undergo higher irradiation to induce mechanical cross-linking, followed by either a re-annealing or remelting step. In other cases, manufacturers “dope” their polyethylene with vitamin E to quench free radicals within the material. While these steps have reduced the number of in vitro wear particles, the problem of wear debris, subsequent osteolysis, and aseptic loosening has not been eliminated.1-5

Polyethylene wear debris within the synovial fluid or tissue of failed TKAs can be identified with scanning electron microscopy or by light microscopy utilizing polarized light.1 In this particular case, wear debris was confirmed within the synovial tissue and in the fluid of the Baker cyst by microscopic analysis.

Formation of a popliteal or Baker cyst as a result of polyethylene wear disease is an infrequent but known complication of TKA. Reports have demonstrated variable success in cyst eradication when revision surgery is performed on knees with synovial cysts. Most of these reports indicate that cyst formation tends to occur as a late complication (7 or more years) after TKA.6-12

Treatment options may include skillful observation with close follow-up or revision surgery. Polyethylene exchange with synovectomy when feasible, as well as component revision with or without excision of the synovial cyst, are surgical options.

Niki and colleagues13 described a gigantic popliteal synovial cyst caused by wear particles after TKA. In this report, the surgeon performed a synovectomy and polyethylene liner exchange with retention of prosthetic components. At 12-month follow-up, the patient was reported to be doing well.

Mavrogenis and coauthors14 reported a wear debris–induced pseudotumor in the popliteal fossa and calf after TKA. In this case, in addition to the synovectomy, the surgeon removed all prosthetic components and used a semi-constrained implant to revise the knee. At 30-month follow-up, the patient reported having a painless knee.

While case reports have indicated that revision TKA for large, painful synovial cysts is a reasonable treatment option in carefully selected patients, there is a paucity of literature on this subject. Moreover, the present case appears to be the first literature report of a tibial nerve compressive neuropathy secondary to a synovial cyst after TKA.

Conclusion

In this report, polyethylene wear disease after TKA resulted in a massive synovial cyst extending into the posterior compartment of the leg. A progressive peripheral neuropathy confirmed by electromyography was also discovered. The patient underwent revision of a loose patellar component and worn polyethylene liner with complete synovectomy plus decompression of the cyst via needle aspiration. This resulted in an excellent short-term outcome with resolution of pain and significant improvement of the peripheral neuropathy 3 months after surgery.

1. Peterson C, Benjamin JB, Szivek JA, Anderson PL, Shriki J, Wong M. Polyethylene particle morphology in synovial fluid of failed knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 1999;359:167-175.

2. Sadoghi P, Liebensteiner M, Agreiter M, Leithner A, Böhler N, Labek G. Revision surgery after total joint arthroplasty: a complication-based analysis using worldwide arthroplasty registers. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8):1329-1332.

3. Calonius O, Saikko V. Analysis of polyethylene particles produced in different wear conditions in vitro. Clin Orthop. 2002;399:219-230.

4. Edwards BT, Leach PB, Zura R, Corpe RS, Young TR. Presentation of gamma-irradiated-in-air polyethylene wear in the form of a synovial cyst. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2003;13(5):413-417.

5. Bosco J, Benjamin J, Wallace D. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of polyethylene wear particles in synovial fluid of patients with total arthroplasty. A preliminary report. Clin Orthop. 1994;309:11-19.

6. Moretti B, Patella V, Mouhsine E, Pesce V, Spinarelli A, Garofalo R. Multilobulated popliteal cyst after a failed total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15(2):212-216.

7. Segura J, Palanca D, Bueno AL, Seral B, Castiella T, Seral F. Baker’s pseudocyst in the prosthetic knee affected with aggressive granulomatosis caused by polyethylene wear. Chir Organi Mov. 1996;81(4):421-426.

8. Ghanem G, Ghanem I, Dagher F. Popliteal cyst in a patient with total knee arthroplasty: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Liban. 2001;49(6):347-350.

9. Hsu WH, Hsu RW, Huang TJ, Lee KF. Dissecting popliteal cyst resulting from a fragmented, dislodged metal part of the patellar component after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17(6):792-797.

10. Chan YS, Wang CJ, Shin CH. Two-stage operation for treatment of a large dissecting popliteal cyst after failed total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15(8):1068-1072.

11. Dirschl DR, Lachiewicz PF. Dissecting popliteal cyst as the presenting symptom of a malfunctioning total knee arthroplasty. Report of four cases. J Arthroplasty. 1992;7(1):37-41.

12. Akisue T, Kurosaka M, Matsui N, et al. Paratibial cyst associated with wear debris after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16(3):389-393.

13. Niki Y, Matsumoto H, Otani T, Yoshimine F, Inokuchi W, Morisue H. Gigantic popliteal synovial cyst caused by wear particles after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(8):1071-1075.

14. Mavrogenis AF, Nomikos GN, Sakellariou VI, Karaliotas GI, Kontovazenitis P, Papagelopoulos PJ. Wear debris pseudotumor following total knee arthroplasty: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:9304.

Symptomatic synovial cyst formation is a rare, late occurrence after total knee arthroplasty (TKA); these cysts are generally discovered by chance. If they enlarge, they can result in significant pain and disability. A few case reports have described the development of very large cysts that required revision knee surgery. In this patient, polyethylene wear disease after TKA resulted in a massive synovial cyst that extended into the posterior compartment of the leg, as well as a progressive peripheral neuropathy. Revision of a loose patella component and worn polyethylene liner with complete synovectomy, plus decompression of the cyst via needle aspiration, resulted in an excellent short-term outcome.

To the author’s knowledge, this is the first case report of peripheral neuropathy of the tibial nerve secondary to a massive Baker cyst after total knee replacement. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

The patient was a 65-year-old woman with a complex medical history and multiple left knee surgeries, including a high tibial osteotomy and subsequent cemented TKA performed in the mid-1990s. She presented to the orthopedic department at a university hospital with complaints of knee pain 13 years after TKA. Observation was recommended; however, she was lost to follow-up.

The patient presented to her primary care physician (PCP) 16 years after TKA with a very large, painful mass in the back of her left leg. An ultrasound showed a large Baker cyst, and the patient was sent to interventional radiology. A few months later, she had an ultrasound-guided aspiration into the left calf, which produced 300 mL of thick synovial fluid. A cell count was not performed, but bacterial cultures were negative. Immediately after the aspiration, the pain was relieved.

Approximately 3 months after the aspiration, she presented again to her PCP with re-accumulation of fluid in the back of her left leg and severe leg pain. She was referred to a different orthopedic surgeon who determined that the risk of surgery was too great given her complex medical history.

The woman’s PCP referred the woman to our office 6 months after the aspiration. On presentation, her pain was localized to the posterior left leg. She reported the pain level as a constant 9 out of 10 on the visual analog scale, despite ingesting high doses of narcotics, including oxycontin and morphine. Her physical examination was remarkable for an ill-defined large calf mass. The posterior compartment of her left leg was firm and severely tender, similar to the characteristic findings seen in acute compartment syndrome.

Radiographs showed evidence of asymmetric polyethylene wear on the medial side of the knee (Figures 1A, 1B). Serum labs were ordered to evaluate for infection. C-reactive protein was mildly elevated at 5.5 mg/L (normal range, 0-5 mg/L); however, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was normal at 12 mm/h (normal range, 0-20 mm/h). Magnetic resonance imaging of the left lower extremity with intravenous contrast showed the presence of a very large Baker cyst contained within the posterior compartment of the knee and a smaller surrounding cyst adjacent to the popliteal neurovascular bundle (Figure 2).

The Baker cyst was re-aspirated in the office. The automated synovial fluid cell count could not be performed because of high fluid viscosity. However, a manual review of the fluid specimen under light microscopy revealed proteinaceous, viscous tan-colored fluid containing no neutrophils and a few macrophages. Fluid cytology was also sent for review under polarizing light microscopy as described by Peterson and colleagues.1 Scattered fragments of polarizable foreign material were consistent with polyethylene debris (Figure 3).

The patient was counseled about the risks and benefits of surgery and was offered revision TKA with polyethylene liner exchange and synovectomy, only after complete cessation of smoking. She underwent serum nicotine monitoring to ensure tobacco cessation; however, she also reported the onset of a progressive sensory deficit over her left foot during this period. Although her medical history was remarkable for spinal stenosis, she noted a progressive decline in sensory function and new-onset paresthesia of her left foot.

An urgent consult to neurology was requested for nerve conduction studies. According to the electrodiagnostic study, the patient had a moderately severe left tibial neuropathy, likely at the popliteal fossa or distal to it. The nerve conduction study showed a chronic tibial nerve peripheral compressive mononeuropathy, and she was immediately scheduled for revision knee surgery with decompression of her Baker cyst to prevent further neurologic deficit.

During surgery, the knee joint exhibited hypertrophic synovitis with a characteristic pale-yellowish discoloration secondary to significant polyethylene wear disease (Figure 4). The polyethylene liner was severely worn with pitting, cracking, and delamination (Figure 5). While the patellar component was grossly loose, the tibial and femoral components were stable. After a complete synovectomy, the loose patellar component and tibial polyethylene liner were replaced. Osteolytic areas within the tibia underwent curettage and allograft impaction grafting. Lastly, decompression of the ruptured Baker cyst was performed via a 16-gauge needle placed in the posterior compartment of the left leg. The calf was gently squeezed with a “milking” maneuver, which yielded approximately 200 mL of thick, mucoid yellowish-brown synovial fluid resembling tapioca pudding (Figure 6).

Postoperatively, all intraoperative cultures were negative, and the patient was followed closely at 1 week, 2 weeks, 6 weeks, and 3 months after the surgery. At her latest follow-up, the posterior leg compartment remained decompressed and her progressive sensory deficit had nearly resolved. Moreover, the left leg and posterior knee pain completely resolved.

Discussion

A leading cause of TKA failure is attributed to aseptic loosening from polyethylene wear disease.2 Implanted high-molecular-weight polyethylene (HMWPE) liners are known to undergo a variety of mechanical wear patterns within the knee. Observed patterns include pitting, scratching, burnishing, scratching, and delamination, which can all liberate numerous fine polyethylene particles.3 This wear debris induces macrophage phagocytosis that triggers an inflammatory reaction within the knee joint and can lead to synovitis, repeat effusions and, ultimately, to aseptic loosening.

Prior to 1996, polyethylene used in total knee replacement underwent a sterilization process in air. This oxygen-rich environment led to the development of free radical formation within the HMWPE. Ultimately, this had a detrimental effect on the polyethylene, leading to the formation of increased wear debris.4

Subsequently, orthopedic companies have changed their sterilization and manufacturing methods. Polyethylene components now undergo a variety of processes to eliminate or reduce oxidation, free-radical formation, and mechanical wear debris. Now, sterilization typically takes place in an inert atmospheric environment. Modern HMWPE implants often undergo higher irradiation to induce mechanical cross-linking, followed by either a re-annealing or remelting step. In other cases, manufacturers “dope” their polyethylene with vitamin E to quench free radicals within the material. While these steps have reduced the number of in vitro wear particles, the problem of wear debris, subsequent osteolysis, and aseptic loosening has not been eliminated.1-5

Polyethylene wear debris within the synovial fluid or tissue of failed TKAs can be identified with scanning electron microscopy or by light microscopy utilizing polarized light.1 In this particular case, wear debris was confirmed within the synovial tissue and in the fluid of the Baker cyst by microscopic analysis.

Formation of a popliteal or Baker cyst as a result of polyethylene wear disease is an infrequent but known complication of TKA. Reports have demonstrated variable success in cyst eradication when revision surgery is performed on knees with synovial cysts. Most of these reports indicate that cyst formation tends to occur as a late complication (7 or more years) after TKA.6-12

Treatment options may include skillful observation with close follow-up or revision surgery. Polyethylene exchange with synovectomy when feasible, as well as component revision with or without excision of the synovial cyst, are surgical options.

Niki and colleagues13 described a gigantic popliteal synovial cyst caused by wear particles after TKA. In this report, the surgeon performed a synovectomy and polyethylene liner exchange with retention of prosthetic components. At 12-month follow-up, the patient was reported to be doing well.

Mavrogenis and coauthors14 reported a wear debris–induced pseudotumor in the popliteal fossa and calf after TKA. In this case, in addition to the synovectomy, the surgeon removed all prosthetic components and used a semi-constrained implant to revise the knee. At 30-month follow-up, the patient reported having a painless knee.

While case reports have indicated that revision TKA for large, painful synovial cysts is a reasonable treatment option in carefully selected patients, there is a paucity of literature on this subject. Moreover, the present case appears to be the first literature report of a tibial nerve compressive neuropathy secondary to a synovial cyst after TKA.

Conclusion

In this report, polyethylene wear disease after TKA resulted in a massive synovial cyst extending into the posterior compartment of the leg. A progressive peripheral neuropathy confirmed by electromyography was also discovered. The patient underwent revision of a loose patellar component and worn polyethylene liner with complete synovectomy plus decompression of the cyst via needle aspiration. This resulted in an excellent short-term outcome with resolution of pain and significant improvement of the peripheral neuropathy 3 months after surgery.

Symptomatic synovial cyst formation is a rare, late occurrence after total knee arthroplasty (TKA); these cysts are generally discovered by chance. If they enlarge, they can result in significant pain and disability. A few case reports have described the development of very large cysts that required revision knee surgery. In this patient, polyethylene wear disease after TKA resulted in a massive synovial cyst that extended into the posterior compartment of the leg, as well as a progressive peripheral neuropathy. Revision of a loose patella component and worn polyethylene liner with complete synovectomy, plus decompression of the cyst via needle aspiration, resulted in an excellent short-term outcome.

To the author’s knowledge, this is the first case report of peripheral neuropathy of the tibial nerve secondary to a massive Baker cyst after total knee replacement. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

The patient was a 65-year-old woman with a complex medical history and multiple left knee surgeries, including a high tibial osteotomy and subsequent cemented TKA performed in the mid-1990s. She presented to the orthopedic department at a university hospital with complaints of knee pain 13 years after TKA. Observation was recommended; however, she was lost to follow-up.

The patient presented to her primary care physician (PCP) 16 years after TKA with a very large, painful mass in the back of her left leg. An ultrasound showed a large Baker cyst, and the patient was sent to interventional radiology. A few months later, she had an ultrasound-guided aspiration into the left calf, which produced 300 mL of thick synovial fluid. A cell count was not performed, but bacterial cultures were negative. Immediately after the aspiration, the pain was relieved.

Approximately 3 months after the aspiration, she presented again to her PCP with re-accumulation of fluid in the back of her left leg and severe leg pain. She was referred to a different orthopedic surgeon who determined that the risk of surgery was too great given her complex medical history.

The woman’s PCP referred the woman to our office 6 months after the aspiration. On presentation, her pain was localized to the posterior left leg. She reported the pain level as a constant 9 out of 10 on the visual analog scale, despite ingesting high doses of narcotics, including oxycontin and morphine. Her physical examination was remarkable for an ill-defined large calf mass. The posterior compartment of her left leg was firm and severely tender, similar to the characteristic findings seen in acute compartment syndrome.

Radiographs showed evidence of asymmetric polyethylene wear on the medial side of the knee (Figures 1A, 1B). Serum labs were ordered to evaluate for infection. C-reactive protein was mildly elevated at 5.5 mg/L (normal range, 0-5 mg/L); however, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was normal at 12 mm/h (normal range, 0-20 mm/h). Magnetic resonance imaging of the left lower extremity with intravenous contrast showed the presence of a very large Baker cyst contained within the posterior compartment of the knee and a smaller surrounding cyst adjacent to the popliteal neurovascular bundle (Figure 2).

The Baker cyst was re-aspirated in the office. The automated synovial fluid cell count could not be performed because of high fluid viscosity. However, a manual review of the fluid specimen under light microscopy revealed proteinaceous, viscous tan-colored fluid containing no neutrophils and a few macrophages. Fluid cytology was also sent for review under polarizing light microscopy as described by Peterson and colleagues.1 Scattered fragments of polarizable foreign material were consistent with polyethylene debris (Figure 3).

The patient was counseled about the risks and benefits of surgery and was offered revision TKA with polyethylene liner exchange and synovectomy, only after complete cessation of smoking. She underwent serum nicotine monitoring to ensure tobacco cessation; however, she also reported the onset of a progressive sensory deficit over her left foot during this period. Although her medical history was remarkable for spinal stenosis, she noted a progressive decline in sensory function and new-onset paresthesia of her left foot.

An urgent consult to neurology was requested for nerve conduction studies. According to the electrodiagnostic study, the patient had a moderately severe left tibial neuropathy, likely at the popliteal fossa or distal to it. The nerve conduction study showed a chronic tibial nerve peripheral compressive mononeuropathy, and she was immediately scheduled for revision knee surgery with decompression of her Baker cyst to prevent further neurologic deficit.

During surgery, the knee joint exhibited hypertrophic synovitis with a characteristic pale-yellowish discoloration secondary to significant polyethylene wear disease (Figure 4). The polyethylene liner was severely worn with pitting, cracking, and delamination (Figure 5). While the patellar component was grossly loose, the tibial and femoral components were stable. After a complete synovectomy, the loose patellar component and tibial polyethylene liner were replaced. Osteolytic areas within the tibia underwent curettage and allograft impaction grafting. Lastly, decompression of the ruptured Baker cyst was performed via a 16-gauge needle placed in the posterior compartment of the left leg. The calf was gently squeezed with a “milking” maneuver, which yielded approximately 200 mL of thick, mucoid yellowish-brown synovial fluid resembling tapioca pudding (Figure 6).

Postoperatively, all intraoperative cultures were negative, and the patient was followed closely at 1 week, 2 weeks, 6 weeks, and 3 months after the surgery. At her latest follow-up, the posterior leg compartment remained decompressed and her progressive sensory deficit had nearly resolved. Moreover, the left leg and posterior knee pain completely resolved.

Discussion

A leading cause of TKA failure is attributed to aseptic loosening from polyethylene wear disease.2 Implanted high-molecular-weight polyethylene (HMWPE) liners are known to undergo a variety of mechanical wear patterns within the knee. Observed patterns include pitting, scratching, burnishing, scratching, and delamination, which can all liberate numerous fine polyethylene particles.3 This wear debris induces macrophage phagocytosis that triggers an inflammatory reaction within the knee joint and can lead to synovitis, repeat effusions and, ultimately, to aseptic loosening.

Prior to 1996, polyethylene used in total knee replacement underwent a sterilization process in air. This oxygen-rich environment led to the development of free radical formation within the HMWPE. Ultimately, this had a detrimental effect on the polyethylene, leading to the formation of increased wear debris.4

Subsequently, orthopedic companies have changed their sterilization and manufacturing methods. Polyethylene components now undergo a variety of processes to eliminate or reduce oxidation, free-radical formation, and mechanical wear debris. Now, sterilization typically takes place in an inert atmospheric environment. Modern HMWPE implants often undergo higher irradiation to induce mechanical cross-linking, followed by either a re-annealing or remelting step. In other cases, manufacturers “dope” their polyethylene with vitamin E to quench free radicals within the material. While these steps have reduced the number of in vitro wear particles, the problem of wear debris, subsequent osteolysis, and aseptic loosening has not been eliminated.1-5

Polyethylene wear debris within the synovial fluid or tissue of failed TKAs can be identified with scanning electron microscopy or by light microscopy utilizing polarized light.1 In this particular case, wear debris was confirmed within the synovial tissue and in the fluid of the Baker cyst by microscopic analysis.

Formation of a popliteal or Baker cyst as a result of polyethylene wear disease is an infrequent but known complication of TKA. Reports have demonstrated variable success in cyst eradication when revision surgery is performed on knees with synovial cysts. Most of these reports indicate that cyst formation tends to occur as a late complication (7 or more years) after TKA.6-12

Treatment options may include skillful observation with close follow-up or revision surgery. Polyethylene exchange with synovectomy when feasible, as well as component revision with or without excision of the synovial cyst, are surgical options.

Niki and colleagues13 described a gigantic popliteal synovial cyst caused by wear particles after TKA. In this report, the surgeon performed a synovectomy and polyethylene liner exchange with retention of prosthetic components. At 12-month follow-up, the patient was reported to be doing well.

Mavrogenis and coauthors14 reported a wear debris–induced pseudotumor in the popliteal fossa and calf after TKA. In this case, in addition to the synovectomy, the surgeon removed all prosthetic components and used a semi-constrained implant to revise the knee. At 30-month follow-up, the patient reported having a painless knee.

While case reports have indicated that revision TKA for large, painful synovial cysts is a reasonable treatment option in carefully selected patients, there is a paucity of literature on this subject. Moreover, the present case appears to be the first literature report of a tibial nerve compressive neuropathy secondary to a synovial cyst after TKA.

Conclusion

In this report, polyethylene wear disease after TKA resulted in a massive synovial cyst extending into the posterior compartment of the leg. A progressive peripheral neuropathy confirmed by electromyography was also discovered. The patient underwent revision of a loose patellar component and worn polyethylene liner with complete synovectomy plus decompression of the cyst via needle aspiration. This resulted in an excellent short-term outcome with resolution of pain and significant improvement of the peripheral neuropathy 3 months after surgery.

1. Peterson C, Benjamin JB, Szivek JA, Anderson PL, Shriki J, Wong M. Polyethylene particle morphology in synovial fluid of failed knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 1999;359:167-175.

2. Sadoghi P, Liebensteiner M, Agreiter M, Leithner A, Böhler N, Labek G. Revision surgery after total joint arthroplasty: a complication-based analysis using worldwide arthroplasty registers. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8):1329-1332.

3. Calonius O, Saikko V. Analysis of polyethylene particles produced in different wear conditions in vitro. Clin Orthop. 2002;399:219-230.

4. Edwards BT, Leach PB, Zura R, Corpe RS, Young TR. Presentation of gamma-irradiated-in-air polyethylene wear in the form of a synovial cyst. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2003;13(5):413-417.

5. Bosco J, Benjamin J, Wallace D. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of polyethylene wear particles in synovial fluid of patients with total arthroplasty. A preliminary report. Clin Orthop. 1994;309:11-19.

6. Moretti B, Patella V, Mouhsine E, Pesce V, Spinarelli A, Garofalo R. Multilobulated popliteal cyst after a failed total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15(2):212-216.

7. Segura J, Palanca D, Bueno AL, Seral B, Castiella T, Seral F. Baker’s pseudocyst in the prosthetic knee affected with aggressive granulomatosis caused by polyethylene wear. Chir Organi Mov. 1996;81(4):421-426.

8. Ghanem G, Ghanem I, Dagher F. Popliteal cyst in a patient with total knee arthroplasty: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Liban. 2001;49(6):347-350.

9. Hsu WH, Hsu RW, Huang TJ, Lee KF. Dissecting popliteal cyst resulting from a fragmented, dislodged metal part of the patellar component after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17(6):792-797.

10. Chan YS, Wang CJ, Shin CH. Two-stage operation for treatment of a large dissecting popliteal cyst after failed total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15(8):1068-1072.

11. Dirschl DR, Lachiewicz PF. Dissecting popliteal cyst as the presenting symptom of a malfunctioning total knee arthroplasty. Report of four cases. J Arthroplasty. 1992;7(1):37-41.

12. Akisue T, Kurosaka M, Matsui N, et al. Paratibial cyst associated with wear debris after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16(3):389-393.

13. Niki Y, Matsumoto H, Otani T, Yoshimine F, Inokuchi W, Morisue H. Gigantic popliteal synovial cyst caused by wear particles after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(8):1071-1075.

14. Mavrogenis AF, Nomikos GN, Sakellariou VI, Karaliotas GI, Kontovazenitis P, Papagelopoulos PJ. Wear debris pseudotumor following total knee arthroplasty: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:9304.

1. Peterson C, Benjamin JB, Szivek JA, Anderson PL, Shriki J, Wong M. Polyethylene particle morphology in synovial fluid of failed knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 1999;359:167-175.

2. Sadoghi P, Liebensteiner M, Agreiter M, Leithner A, Böhler N, Labek G. Revision surgery after total joint arthroplasty: a complication-based analysis using worldwide arthroplasty registers. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8):1329-1332.

3. Calonius O, Saikko V. Analysis of polyethylene particles produced in different wear conditions in vitro. Clin Orthop. 2002;399:219-230.

4. Edwards BT, Leach PB, Zura R, Corpe RS, Young TR. Presentation of gamma-irradiated-in-air polyethylene wear in the form of a synovial cyst. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2003;13(5):413-417.

5. Bosco J, Benjamin J, Wallace D. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of polyethylene wear particles in synovial fluid of patients with total arthroplasty. A preliminary report. Clin Orthop. 1994;309:11-19.

6. Moretti B, Patella V, Mouhsine E, Pesce V, Spinarelli A, Garofalo R. Multilobulated popliteal cyst after a failed total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15(2):212-216.

7. Segura J, Palanca D, Bueno AL, Seral B, Castiella T, Seral F. Baker’s pseudocyst in the prosthetic knee affected with aggressive granulomatosis caused by polyethylene wear. Chir Organi Mov. 1996;81(4):421-426.

8. Ghanem G, Ghanem I, Dagher F. Popliteal cyst in a patient with total knee arthroplasty: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Liban. 2001;49(6):347-350.

9. Hsu WH, Hsu RW, Huang TJ, Lee KF. Dissecting popliteal cyst resulting from a fragmented, dislodged metal part of the patellar component after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17(6):792-797.

10. Chan YS, Wang CJ, Shin CH. Two-stage operation for treatment of a large dissecting popliteal cyst after failed total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15(8):1068-1072.

11. Dirschl DR, Lachiewicz PF. Dissecting popliteal cyst as the presenting symptom of a malfunctioning total knee arthroplasty. Report of four cases. J Arthroplasty. 1992;7(1):37-41.

12. Akisue T, Kurosaka M, Matsui N, et al. Paratibial cyst associated with wear debris after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16(3):389-393.

13. Niki Y, Matsumoto H, Otani T, Yoshimine F, Inokuchi W, Morisue H. Gigantic popliteal synovial cyst caused by wear particles after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(8):1071-1075.

14. Mavrogenis AF, Nomikos GN, Sakellariou VI, Karaliotas GI, Kontovazenitis P, Papagelopoulos PJ. Wear debris pseudotumor following total knee arthroplasty: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:9304.

Revision Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction With Bone–Patellar Tendon–Bone Allograft and Extra-Articular Iliotibial Band Tenodesis

Primary anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction has satisfactory outcomes in 75% to 97% of patients.1-3 Despite this high success rate, the number of revision ACL reconstructions has risen4 and is likely underreported.5 Recurrent instability occurs if the reconstructed ligament fails to provide adequate anterior and rotational knee stability. Causes of graft failure include repeat trauma, early return to high-demand activity, poor operative technique (including poor graft placement), failure to address concomitant pathology, and perioperative complications (eg, infection, stiffness).4 In addition, most patients who have revision ACL reconstruction received autograft tissue in the initial surgery, and allograft is thus not uncommon in revision ACL surgery. Allograft tissue has longer incorporation times6 and increased incidence of recurrent postoperative instability when compared with autograft tissue.7 Extra-articular tenodesis may thus be used to provide additional stability to the revision allograft tissue while it incorporates.

In this article, we describe our use of an extra-articular iliotibial band (ITB) tenodesis as an augmentative procedure in patients undergoing revision ACL reconstruction with bone–patellar tendon–bone (BPTB) allograft.

Surgical Technique

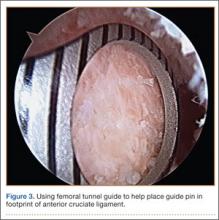

After induction of anesthesia and careful positioning, the patient is prepared and draped in the usual sterile fashion. Standard anteromedial, anterolateral, and superolateral outflow portals are established, and diagnostic arthroscopy is performed to inspect the cruciate ligaments, menisci, and articular cartilage (Figure 1). Peripheral meniscal tears should be repaired (Figure 2), and central or inner tears should be débrided to a stable rim. If meniscal repair is performed, sutures should be tied at the end of the case. Unstable articular cartilage defects should also be débrided. An 8- to 12-cm lateral hockey-stick incision is then made from the Gerdy tubercle to the inferior edge of the lateral femoral epicondyle in preparation for the ITB tenodesis (Figure 1). The lateral collateral ligament (LCL), the lateral head of the gastrocnemius, and the ITB are identified. The peroneal nerve should be significantly distal to the working field.

Remnants of the previous ACL graft are débrided, and, if necessary, a modified notchplasty is performed. A position for the new femoral tunnel is located and is confirmed with intraoperative fluoroscopy. This tunnel is established with compaction drill bits and dilated to the appropriate diameter through the anteromedial portal with the knee in 120° of flexion.

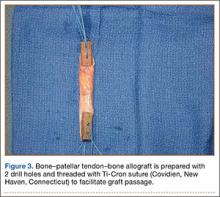

BPTB allograft is prepared first by cutting its central third to the desired diameter (Figure 3). The bone-plug ends are prepared with compaction pliers. Two 2.0-mm drill holes are made in each of the allograft bone plugs, and a No. 5 Ti-Cron suture (Covidien, New Haven, Connecticut) is placed through each of the holes. We typically use 2 sutures on each bone plug.

A tibial tunnel is then established with an ACL drill guide under arthroscopic visualization and intraoperative fluoroscopy for confirmation of correct pin placement. We use Kirschner wires (with parallel pin guides as needed), compaction drills, and dilators to create a well-positioned tunnel of the appropriate diameter. The allograft is then passed through the tibia and femur in retrograde fashion. We secure the femoral side with an AO (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen) 4.5-mm bicortical screw and washer. Our tibial fixation is secured after the ITB tenodesis. The knee is then cycled a dozen times.

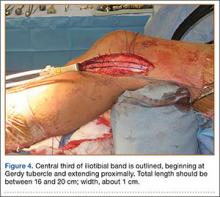

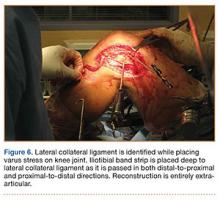

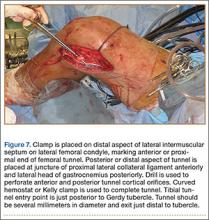

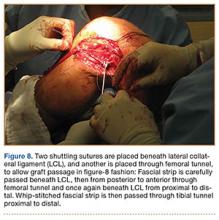

In preparation for the ITB tenodesis, we lengthen our previously made incision by about 4 cm proximally along the posterior aspect of the ITB. The central portion of the ITB is then outlined at the Gerdy tubercle and split with a No. 10 blade. This generally leaves an approximately 12- to 14-mm strip of ITB centrally (Figure 4). This portion should be gently lifted from the underlying tissue attachments distally at the insertion on the Gerdy tubercle. The interval between the LCL and lateral capsule of the knee is identified, and a No. 2 Ti-Cron whip-stitch is thrown through the free end of the ITB graft (Figure 5). The anterior aspect of the femoral tunnel is at the distal aspect of the lateral femoral condyle, and the posterior aspect is at the juncture of the proximal LCL and the lateral head of the gastrocnemius. The cortices of these landmarks should be perforated with a drill, and a curved instrument should be used to create a bone tunnel at this location (Figure 6). The tibial tunnel is just posterior and distal to the Gerdy tubercle and should be created in similar fashion. The graft is then passed underneath the LCL (Figure 7), through the proximal tunnel that has been created on the lateral femoral condyle, and then back down through the LCL and back onto itself after exiting the tibial tunnel (Figure 8). With the knee at 30° of flexion, the ITB graft is tensioned and sutured down to intact ITB fascia just proximal to the tibial tunnel orifice (Figure 9). We check knee range of motion (ROM) and then perform a Lachman test to assess changes in knee stability. The pivot shift examination is omitted to avoid placing excessive stress on the tenodesis. The tibial side of the patellar tendon allograft is then tensioned and secured over an AO 4.5-mm bicortical screw with washer with the knee in full extension. The screw is then tightened at 30° of knee flexion.

The ITB fascia is closed to the lateral femoral epicondyle with a running heavy suture, and all incisions are then irrigated and closed (Figures 10, 11). Standard sterile surgical dressing, Cryo/Cuff (Aircast, Vista, California), and brace are applied with the knee locked at 20°. Patients are generally discharged home the same day and followed up in clinic 1 week after surgery.

Complications

The peroneal nerve must be identified and protected during the open lateral procedure. In addition, the need for the extra lateral incision poses a slightly higher risk for infection compared with the traditional arthroscopic revision ACL procedure. Last, the additional tunnels required for the tenodesis can increase the theoretical potential for distal femur fracture and ACL graft fixation failure on the femoral side.

Postoperative Management

The operative knee is kept in extension in a brace locked at 20° for week 1 after surgery. Isometric quadriceps exercises are started immediately after surgery. Flexion to 90° is allowed starting week 2 after surgery, when the patient begins supervised active/passive flexion and progressive ROM exercises. In most cases, full ROM should be achieved by 6 to 8 weeks after surgery. Patients are progressed in their weight-bearing status by about 25% of their body weight per week, and use of crutches should be discontinued by week 4 after surgery. The brace should be discontinued by week 6 after surgery, when use of stationary bicycle and closed chain exercises begin. The patient may begin jogging when the operative leg regains 80% of contralateral quadriceps strength via Cybex strength testing. Functional drills begin in month 6, but patients should be counseled against returning to sport any earlier than 9 months after surgery.

Discussion

Achieving a successful outcome in revision ACL surgery (vs primary ACL surgery) is a significant challenge. Any of numerous factors can make the revision surgery more challenging, including existing poorly placed tunnels, tunnel expansion, lack of ideal graft choice, loss of secondary stabilizers, and deviations of the weight-bearing axis. Therefore, outcomes of revision surgery tend to be more moderate than outcomes of primary procedures.4,8-12

Revision ACL reconstruction techniques are varied and can involve use of autograft or allograft tissue as well as extra-articular augmentation techniques. Diamantopoulos and colleagues8 reported the outcomes of revision ACL reconstruction using bone–tendon–bone, hamstring, or quadriceps autografts in 107 patients. The majority of patients had improved outcome measures (mean Lysholm score improved from 51.5 to 88.5) and side-to-side laxity measurements. However, only 36.4% returned to preinjury activity level. Similarly, Noyes and Barber-Westin9 reported the outcomes of revision ACL reconstruction using quadriceps tendon–patellar bone autograft in 21 patients. Although there was significant improvement in terms of symptoms and activity level, 4 of the 21 knees were graded abnormal or severely abnormal on the IKDC (International Knee Documentation Committee) ligament rating. In a systematic review, pooled results of revision ACL reconstructions reiterated the above results.10 Eight hundred sixty-three patients from 21 studies were included in the analysis, which found significantly worse subjective outcomes than for primary procedures and a dramatically higher failure rate for the re-reconstructed ACL.

Several authors have directly compared primary cohorts with revision cohorts. Ahn and colleagues11 compared the outcomes of 59 revision ACL reconstructions with those of 117 primary reconstructions at a single institution. Although statistical comparison of stability between primary and revision ACL reconstructions showed no difference, revision reconstructions fared more poorly in terms of quality of life and return to activity compared with primary reconstructions. In a large cohort study of the Danish registry, revisions were found to have worse subjective outcomes than primary reconstructions as well.12 The study also found that the rerupture risk was significantly higher (relative risk, 2.05) when allograft was used.

Given the inferior results of revision surgery, our technique is recommended to augment the stability of reconstructed knees in the setting of revision ACL reconstruction. Adding the extra-articular procedure may augment the revised graft and protect it from excessive stress.13 A cadaver study compared double-bundle ACL reconstruction with single-bundle hamstring reconstruction plus extra-articular lateral tenodesis and found improved internal rotation control at 30° of flexion in the latter.14 Using contralateral 4-strand hamstring autograft in combination with an extra-articular lateral augment can have encouraging outcomes. Ferretti and colleagues15 reported an average Lysholm score of 95 in 12 patients who underwent this revision procedure and good anterior-to-posterior stability in 11 of the 12 patients. Trojani and colleagues16 reported on a cohort of 163 patients who underwent ACL revision surgery over a 10-year period. The authors found that 80% of patients with a lateral extra-articular tenodesis performed to augment their revision reconstruction had a negative pivot shift at long-term follow-up—versus only 63% of patients who underwent isolated revision ACL reconstruction. This finding was statistically significant, but the authors did not find any differences in IKDC scores between groups. These results support the initial biomechanical findings of Engebretsen and colleagues,17 who found that adding a lateral tenodesis decreased the forces on the reconstructed graft by 15%.

Conclusion

This technique allows for protection of the intra-articular allograft ligament reconstruction with improved rotational control that may potentially allow for improved subjective outcomes and protect against graft failure. Given the common pitfalls with stability in revision ACL surgery with allograft, this lateral extra-articular procedure can be an important structural augmentation in this challenging clinical issue in knee surgery.

1. Bach BR Jr. Revision anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(suppl 1):14-29.

2. Baer GS, Harner CD. Clinical outcomes of allograft versus autograft in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin Sports Med. 2007;26(4):661-681.

3. Spindler KP, Kuhn JE, Freedman KB, Matthews CE, Dittus RS, Harrell FE Jr. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction autograft choice: bone–tendon–bone versus hamstring: does it really matter? A systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(8):1986-1995.

4. Kamath GV, Redfern JC, Greis PE, Burks RT. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(1):199-217.

5. Gianotti SM, Marshall SW, Hume PA, Bunt L. Incidence of anterior cruciate ligament injury and other knee ligament injuries: a national population-based study. J Sci Med Sport. 2009;12(6):622-627.

6. Jackson DW, Grood ES, Goldstein JD, et al. A comparison of patellar tendon autograft and allograft used for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the goat model. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21(2):176-185.

7. Mascarenhas R, Tranovich M, Karpie JC, Irrgang JJ, Fu FH, Harner CD. Patellar tendon anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the high-demand patient: evaluation of autograft versus allograft reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(9 Suppl):S58-S66.

8. Diamantopoulos AP, Lorbach O, Paessler HH. Anterior cruciate ligament revision reconstruction: results in 107 patients. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(5):851-860.

9. Noyes FR, Barber-Westin SD. Anterior cruciate ligament revision reconstruction: results using a quadriceps tendon–patellar bone autograft. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(4):553-564.

10. Wright RW, Gill CS, Chen L, et al. Outcome of revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(6):531-536.

11. Ahn JH, Lee YS, Ha HC. Comparison of revision surgery with primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and outcome of revision surgery between different graft materials. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(10):1889-1895.

12. Lind M, Menhert F, Pedersen AB. Incidence and outcome after revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: results from the Danish registry for knee ligament reconstructions. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(7):1551-1557.

13. Ferretti A, Conteduca F, Monaco E, De Carli A, D’Arrigo C. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with doubled semitendinosus and gracilis tendons and lateral extra-articular reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(11):2373-2379.

14. Monaco E, Labianca L, Conteduca F, De Carli A, Ferretti A. Double bundle or single bundle plus extraarticular tenodesis in ACL reconstruction? A CAOS study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15(10):1168-1174.

15. Ferretti A, Monaco E, Caperna L, Palma T, Conteduca F. Revision ACL reconstruction using contralateral hamstrings. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(3):690-695.

16. Trojani C, Beaufils P, Burdin G, et al. Revision ACL reconstruction: influence of a lateral tenodesis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(8):1565-1570.

17. Engebretsen L, Lew WD, Lewis JL, Hunter RE. The effect of an iliotibial tenodesis on intraarticular graft forces and knee joint motion. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18(2):169-176.

Primary anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction has satisfactory outcomes in 75% to 97% of patients.1-3 Despite this high success rate, the number of revision ACL reconstructions has risen4 and is likely underreported.5 Recurrent instability occurs if the reconstructed ligament fails to provide adequate anterior and rotational knee stability. Causes of graft failure include repeat trauma, early return to high-demand activity, poor operative technique (including poor graft placement), failure to address concomitant pathology, and perioperative complications (eg, infection, stiffness).4 In addition, most patients who have revision ACL reconstruction received autograft tissue in the initial surgery, and allograft is thus not uncommon in revision ACL surgery. Allograft tissue has longer incorporation times6 and increased incidence of recurrent postoperative instability when compared with autograft tissue.7 Extra-articular tenodesis may thus be used to provide additional stability to the revision allograft tissue while it incorporates.

In this article, we describe our use of an extra-articular iliotibial band (ITB) tenodesis as an augmentative procedure in patients undergoing revision ACL reconstruction with bone–patellar tendon–bone (BPTB) allograft.

Surgical Technique

After induction of anesthesia and careful positioning, the patient is prepared and draped in the usual sterile fashion. Standard anteromedial, anterolateral, and superolateral outflow portals are established, and diagnostic arthroscopy is performed to inspect the cruciate ligaments, menisci, and articular cartilage (Figure 1). Peripheral meniscal tears should be repaired (Figure 2), and central or inner tears should be débrided to a stable rim. If meniscal repair is performed, sutures should be tied at the end of the case. Unstable articular cartilage defects should also be débrided. An 8- to 12-cm lateral hockey-stick incision is then made from the Gerdy tubercle to the inferior edge of the lateral femoral epicondyle in preparation for the ITB tenodesis (Figure 1). The lateral collateral ligament (LCL), the lateral head of the gastrocnemius, and the ITB are identified. The peroneal nerve should be significantly distal to the working field.

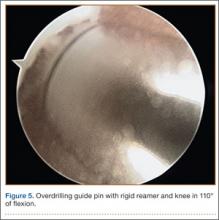

Remnants of the previous ACL graft are débrided, and, if necessary, a modified notchplasty is performed. A position for the new femoral tunnel is located and is confirmed with intraoperative fluoroscopy. This tunnel is established with compaction drill bits and dilated to the appropriate diameter through the anteromedial portal with the knee in 120° of flexion.

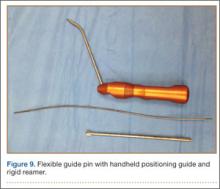

BPTB allograft is prepared first by cutting its central third to the desired diameter (Figure 3). The bone-plug ends are prepared with compaction pliers. Two 2.0-mm drill holes are made in each of the allograft bone plugs, and a No. 5 Ti-Cron suture (Covidien, New Haven, Connecticut) is placed through each of the holes. We typically use 2 sutures on each bone plug.

A tibial tunnel is then established with an ACL drill guide under arthroscopic visualization and intraoperative fluoroscopy for confirmation of correct pin placement. We use Kirschner wires (with parallel pin guides as needed), compaction drills, and dilators to create a well-positioned tunnel of the appropriate diameter. The allograft is then passed through the tibia and femur in retrograde fashion. We secure the femoral side with an AO (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen) 4.5-mm bicortical screw and washer. Our tibial fixation is secured after the ITB tenodesis. The knee is then cycled a dozen times.

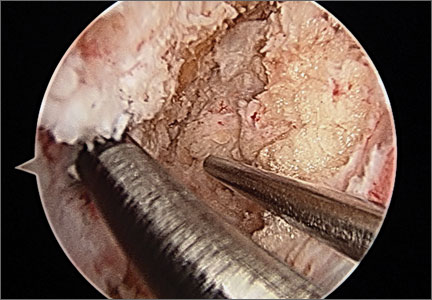

In preparation for the ITB tenodesis, we lengthen our previously made incision by about 4 cm proximally along the posterior aspect of the ITB. The central portion of the ITB is then outlined at the Gerdy tubercle and split with a No. 10 blade. This generally leaves an approximately 12- to 14-mm strip of ITB centrally (Figure 4). This portion should be gently lifted from the underlying tissue attachments distally at the insertion on the Gerdy tubercle. The interval between the LCL and lateral capsule of the knee is identified, and a No. 2 Ti-Cron whip-stitch is thrown through the free end of the ITB graft (Figure 5). The anterior aspect of the femoral tunnel is at the distal aspect of the lateral femoral condyle, and the posterior aspect is at the juncture of the proximal LCL and the lateral head of the gastrocnemius. The cortices of these landmarks should be perforated with a drill, and a curved instrument should be used to create a bone tunnel at this location (Figure 6). The tibial tunnel is just posterior and distal to the Gerdy tubercle and should be created in similar fashion. The graft is then passed underneath the LCL (Figure 7), through the proximal tunnel that has been created on the lateral femoral condyle, and then back down through the LCL and back onto itself after exiting the tibial tunnel (Figure 8). With the knee at 30° of flexion, the ITB graft is tensioned and sutured down to intact ITB fascia just proximal to the tibial tunnel orifice (Figure 9). We check knee range of motion (ROM) and then perform a Lachman test to assess changes in knee stability. The pivot shift examination is omitted to avoid placing excessive stress on the tenodesis. The tibial side of the patellar tendon allograft is then tensioned and secured over an AO 4.5-mm bicortical screw with washer with the knee in full extension. The screw is then tightened at 30° of knee flexion.

The ITB fascia is closed to the lateral femoral epicondyle with a running heavy suture, and all incisions are then irrigated and closed (Figures 10, 11). Standard sterile surgical dressing, Cryo/Cuff (Aircast, Vista, California), and brace are applied with the knee locked at 20°. Patients are generally discharged home the same day and followed up in clinic 1 week after surgery.

Complications

The peroneal nerve must be identified and protected during the open lateral procedure. In addition, the need for the extra lateral incision poses a slightly higher risk for infection compared with the traditional arthroscopic revision ACL procedure. Last, the additional tunnels required for the tenodesis can increase the theoretical potential for distal femur fracture and ACL graft fixation failure on the femoral side.

Postoperative Management

The operative knee is kept in extension in a brace locked at 20° for week 1 after surgery. Isometric quadriceps exercises are started immediately after surgery. Flexion to 90° is allowed starting week 2 after surgery, when the patient begins supervised active/passive flexion and progressive ROM exercises. In most cases, full ROM should be achieved by 6 to 8 weeks after surgery. Patients are progressed in their weight-bearing status by about 25% of their body weight per week, and use of crutches should be discontinued by week 4 after surgery. The brace should be discontinued by week 6 after surgery, when use of stationary bicycle and closed chain exercises begin. The patient may begin jogging when the operative leg regains 80% of contralateral quadriceps strength via Cybex strength testing. Functional drills begin in month 6, but patients should be counseled against returning to sport any earlier than 9 months after surgery.

Discussion

Achieving a successful outcome in revision ACL surgery (vs primary ACL surgery) is a significant challenge. Any of numerous factors can make the revision surgery more challenging, including existing poorly placed tunnels, tunnel expansion, lack of ideal graft choice, loss of secondary stabilizers, and deviations of the weight-bearing axis. Therefore, outcomes of revision surgery tend to be more moderate than outcomes of primary procedures.4,8-12

Revision ACL reconstruction techniques are varied and can involve use of autograft or allograft tissue as well as extra-articular augmentation techniques. Diamantopoulos and colleagues8 reported the outcomes of revision ACL reconstruction using bone–tendon–bone, hamstring, or quadriceps autografts in 107 patients. The majority of patients had improved outcome measures (mean Lysholm score improved from 51.5 to 88.5) and side-to-side laxity measurements. However, only 36.4% returned to preinjury activity level. Similarly, Noyes and Barber-Westin9 reported the outcomes of revision ACL reconstruction using quadriceps tendon–patellar bone autograft in 21 patients. Although there was significant improvement in terms of symptoms and activity level, 4 of the 21 knees were graded abnormal or severely abnormal on the IKDC (International Knee Documentation Committee) ligament rating. In a systematic review, pooled results of revision ACL reconstructions reiterated the above results.10 Eight hundred sixty-three patients from 21 studies were included in the analysis, which found significantly worse subjective outcomes than for primary procedures and a dramatically higher failure rate for the re-reconstructed ACL.

Several authors have directly compared primary cohorts with revision cohorts. Ahn and colleagues11 compared the outcomes of 59 revision ACL reconstructions with those of 117 primary reconstructions at a single institution. Although statistical comparison of stability between primary and revision ACL reconstructions showed no difference, revision reconstructions fared more poorly in terms of quality of life and return to activity compared with primary reconstructions. In a large cohort study of the Danish registry, revisions were found to have worse subjective outcomes than primary reconstructions as well.12 The study also found that the rerupture risk was significantly higher (relative risk, 2.05) when allograft was used.

Given the inferior results of revision surgery, our technique is recommended to augment the stability of reconstructed knees in the setting of revision ACL reconstruction. Adding the extra-articular procedure may augment the revised graft and protect it from excessive stress.13 A cadaver study compared double-bundle ACL reconstruction with single-bundle hamstring reconstruction plus extra-articular lateral tenodesis and found improved internal rotation control at 30° of flexion in the latter.14 Using contralateral 4-strand hamstring autograft in combination with an extra-articular lateral augment can have encouraging outcomes. Ferretti and colleagues15 reported an average Lysholm score of 95 in 12 patients who underwent this revision procedure and good anterior-to-posterior stability in 11 of the 12 patients. Trojani and colleagues16 reported on a cohort of 163 patients who underwent ACL revision surgery over a 10-year period. The authors found that 80% of patients with a lateral extra-articular tenodesis performed to augment their revision reconstruction had a negative pivot shift at long-term follow-up—versus only 63% of patients who underwent isolated revision ACL reconstruction. This finding was statistically significant, but the authors did not find any differences in IKDC scores between groups. These results support the initial biomechanical findings of Engebretsen and colleagues,17 who found that adding a lateral tenodesis decreased the forces on the reconstructed graft by 15%.

Conclusion

This technique allows for protection of the intra-articular allograft ligament reconstruction with improved rotational control that may potentially allow for improved subjective outcomes and protect against graft failure. Given the common pitfalls with stability in revision ACL surgery with allograft, this lateral extra-articular procedure can be an important structural augmentation in this challenging clinical issue in knee surgery.

Primary anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction has satisfactory outcomes in 75% to 97% of patients.1-3 Despite this high success rate, the number of revision ACL reconstructions has risen4 and is likely underreported.5 Recurrent instability occurs if the reconstructed ligament fails to provide adequate anterior and rotational knee stability. Causes of graft failure include repeat trauma, early return to high-demand activity, poor operative technique (including poor graft placement), failure to address concomitant pathology, and perioperative complications (eg, infection, stiffness).4 In addition, most patients who have revision ACL reconstruction received autograft tissue in the initial surgery, and allograft is thus not uncommon in revision ACL surgery. Allograft tissue has longer incorporation times6 and increased incidence of recurrent postoperative instability when compared with autograft tissue.7 Extra-articular tenodesis may thus be used to provide additional stability to the revision allograft tissue while it incorporates.

In this article, we describe our use of an extra-articular iliotibial band (ITB) tenodesis as an augmentative procedure in patients undergoing revision ACL reconstruction with bone–patellar tendon–bone (BPTB) allograft.

Surgical Technique

After induction of anesthesia and careful positioning, the patient is prepared and draped in the usual sterile fashion. Standard anteromedial, anterolateral, and superolateral outflow portals are established, and diagnostic arthroscopy is performed to inspect the cruciate ligaments, menisci, and articular cartilage (Figure 1). Peripheral meniscal tears should be repaired (Figure 2), and central or inner tears should be débrided to a stable rim. If meniscal repair is performed, sutures should be tied at the end of the case. Unstable articular cartilage defects should also be débrided. An 8- to 12-cm lateral hockey-stick incision is then made from the Gerdy tubercle to the inferior edge of the lateral femoral epicondyle in preparation for the ITB tenodesis (Figure 1). The lateral collateral ligament (LCL), the lateral head of the gastrocnemius, and the ITB are identified. The peroneal nerve should be significantly distal to the working field.

Remnants of the previous ACL graft are débrided, and, if necessary, a modified notchplasty is performed. A position for the new femoral tunnel is located and is confirmed with intraoperative fluoroscopy. This tunnel is established with compaction drill bits and dilated to the appropriate diameter through the anteromedial portal with the knee in 120° of flexion.

BPTB allograft is prepared first by cutting its central third to the desired diameter (Figure 3). The bone-plug ends are prepared with compaction pliers. Two 2.0-mm drill holes are made in each of the allograft bone plugs, and a No. 5 Ti-Cron suture (Covidien, New Haven, Connecticut) is placed through each of the holes. We typically use 2 sutures on each bone plug.

A tibial tunnel is then established with an ACL drill guide under arthroscopic visualization and intraoperative fluoroscopy for confirmation of correct pin placement. We use Kirschner wires (with parallel pin guides as needed), compaction drills, and dilators to create a well-positioned tunnel of the appropriate diameter. The allograft is then passed through the tibia and femur in retrograde fashion. We secure the femoral side with an AO (Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen) 4.5-mm bicortical screw and washer. Our tibial fixation is secured after the ITB tenodesis. The knee is then cycled a dozen times.

In preparation for the ITB tenodesis, we lengthen our previously made incision by about 4 cm proximally along the posterior aspect of the ITB. The central portion of the ITB is then outlined at the Gerdy tubercle and split with a No. 10 blade. This generally leaves an approximately 12- to 14-mm strip of ITB centrally (Figure 4). This portion should be gently lifted from the underlying tissue attachments distally at the insertion on the Gerdy tubercle. The interval between the LCL and lateral capsule of the knee is identified, and a No. 2 Ti-Cron whip-stitch is thrown through the free end of the ITB graft (Figure 5). The anterior aspect of the femoral tunnel is at the distal aspect of the lateral femoral condyle, and the posterior aspect is at the juncture of the proximal LCL and the lateral head of the gastrocnemius. The cortices of these landmarks should be perforated with a drill, and a curved instrument should be used to create a bone tunnel at this location (Figure 6). The tibial tunnel is just posterior and distal to the Gerdy tubercle and should be created in similar fashion. The graft is then passed underneath the LCL (Figure 7), through the proximal tunnel that has been created on the lateral femoral condyle, and then back down through the LCL and back onto itself after exiting the tibial tunnel (Figure 8). With the knee at 30° of flexion, the ITB graft is tensioned and sutured down to intact ITB fascia just proximal to the tibial tunnel orifice (Figure 9). We check knee range of motion (ROM) and then perform a Lachman test to assess changes in knee stability. The pivot shift examination is omitted to avoid placing excessive stress on the tenodesis. The tibial side of the patellar tendon allograft is then tensioned and secured over an AO 4.5-mm bicortical screw with washer with the knee in full extension. The screw is then tightened at 30° of knee flexion.

The ITB fascia is closed to the lateral femoral epicondyle with a running heavy suture, and all incisions are then irrigated and closed (Figures 10, 11). Standard sterile surgical dressing, Cryo/Cuff (Aircast, Vista, California), and brace are applied with the knee locked at 20°. Patients are generally discharged home the same day and followed up in clinic 1 week after surgery.

Complications

The peroneal nerve must be identified and protected during the open lateral procedure. In addition, the need for the extra lateral incision poses a slightly higher risk for infection compared with the traditional arthroscopic revision ACL procedure. Last, the additional tunnels required for the tenodesis can increase the theoretical potential for distal femur fracture and ACL graft fixation failure on the femoral side.

Postoperative Management

The operative knee is kept in extension in a brace locked at 20° for week 1 after surgery. Isometric quadriceps exercises are started immediately after surgery. Flexion to 90° is allowed starting week 2 after surgery, when the patient begins supervised active/passive flexion and progressive ROM exercises. In most cases, full ROM should be achieved by 6 to 8 weeks after surgery. Patients are progressed in their weight-bearing status by about 25% of their body weight per week, and use of crutches should be discontinued by week 4 after surgery. The brace should be discontinued by week 6 after surgery, when use of stationary bicycle and closed chain exercises begin. The patient may begin jogging when the operative leg regains 80% of contralateral quadriceps strength via Cybex strength testing. Functional drills begin in month 6, but patients should be counseled against returning to sport any earlier than 9 months after surgery.

Discussion

Achieving a successful outcome in revision ACL surgery (vs primary ACL surgery) is a significant challenge. Any of numerous factors can make the revision surgery more challenging, including existing poorly placed tunnels, tunnel expansion, lack of ideal graft choice, loss of secondary stabilizers, and deviations of the weight-bearing axis. Therefore, outcomes of revision surgery tend to be more moderate than outcomes of primary procedures.4,8-12

Revision ACL reconstruction techniques are varied and can involve use of autograft or allograft tissue as well as extra-articular augmentation techniques. Diamantopoulos and colleagues8 reported the outcomes of revision ACL reconstruction using bone–tendon–bone, hamstring, or quadriceps autografts in 107 patients. The majority of patients had improved outcome measures (mean Lysholm score improved from 51.5 to 88.5) and side-to-side laxity measurements. However, only 36.4% returned to preinjury activity level. Similarly, Noyes and Barber-Westin9 reported the outcomes of revision ACL reconstruction using quadriceps tendon–patellar bone autograft in 21 patients. Although there was significant improvement in terms of symptoms and activity level, 4 of the 21 knees were graded abnormal or severely abnormal on the IKDC (International Knee Documentation Committee) ligament rating. In a systematic review, pooled results of revision ACL reconstructions reiterated the above results.10 Eight hundred sixty-three patients from 21 studies were included in the analysis, which found significantly worse subjective outcomes than for primary procedures and a dramatically higher failure rate for the re-reconstructed ACL.

Several authors have directly compared primary cohorts with revision cohorts. Ahn and colleagues11 compared the outcomes of 59 revision ACL reconstructions with those of 117 primary reconstructions at a single institution. Although statistical comparison of stability between primary and revision ACL reconstructions showed no difference, revision reconstructions fared more poorly in terms of quality of life and return to activity compared with primary reconstructions. In a large cohort study of the Danish registry, revisions were found to have worse subjective outcomes than primary reconstructions as well.12 The study also found that the rerupture risk was significantly higher (relative risk, 2.05) when allograft was used.

Given the inferior results of revision surgery, our technique is recommended to augment the stability of reconstructed knees in the setting of revision ACL reconstruction. Adding the extra-articular procedure may augment the revised graft and protect it from excessive stress.13 A cadaver study compared double-bundle ACL reconstruction with single-bundle hamstring reconstruction plus extra-articular lateral tenodesis and found improved internal rotation control at 30° of flexion in the latter.14 Using contralateral 4-strand hamstring autograft in combination with an extra-articular lateral augment can have encouraging outcomes. Ferretti and colleagues15 reported an average Lysholm score of 95 in 12 patients who underwent this revision procedure and good anterior-to-posterior stability in 11 of the 12 patients. Trojani and colleagues16 reported on a cohort of 163 patients who underwent ACL revision surgery over a 10-year period. The authors found that 80% of patients with a lateral extra-articular tenodesis performed to augment their revision reconstruction had a negative pivot shift at long-term follow-up—versus only 63% of patients who underwent isolated revision ACL reconstruction. This finding was statistically significant, but the authors did not find any differences in IKDC scores between groups. These results support the initial biomechanical findings of Engebretsen and colleagues,17 who found that adding a lateral tenodesis decreased the forces on the reconstructed graft by 15%.

Conclusion

This technique allows for protection of the intra-articular allograft ligament reconstruction with improved rotational control that may potentially allow for improved subjective outcomes and protect against graft failure. Given the common pitfalls with stability in revision ACL surgery with allograft, this lateral extra-articular procedure can be an important structural augmentation in this challenging clinical issue in knee surgery.

1. Bach BR Jr. Revision anterior cruciate ligament surgery. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(suppl 1):14-29.

2. Baer GS, Harner CD. Clinical outcomes of allograft versus autograft in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin Sports Med. 2007;26(4):661-681.

3. Spindler KP, Kuhn JE, Freedman KB, Matthews CE, Dittus RS, Harrell FE Jr. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction autograft choice: bone–tendon–bone versus hamstring: does it really matter? A systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(8):1986-1995.

4. Kamath GV, Redfern JC, Greis PE, Burks RT. Revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(1):199-217.

5. Gianotti SM, Marshall SW, Hume PA, Bunt L. Incidence of anterior cruciate ligament injury and other knee ligament injuries: a national population-based study. J Sci Med Sport. 2009;12(6):622-627.

6. Jackson DW, Grood ES, Goldstein JD, et al. A comparison of patellar tendon autograft and allograft used for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the goat model. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21(2):176-185.

7. Mascarenhas R, Tranovich M, Karpie JC, Irrgang JJ, Fu FH, Harner CD. Patellar tendon anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the high-demand patient: evaluation of autograft versus allograft reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(9 Suppl):S58-S66.

8. Diamantopoulos AP, Lorbach O, Paessler HH. Anterior cruciate ligament revision reconstruction: results in 107 patients. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(5):851-860.

9. Noyes FR, Barber-Westin SD. Anterior cruciate ligament revision reconstruction: results using a quadriceps tendon–patellar bone autograft. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(4):553-564.

10. Wright RW, Gill CS, Chen L, et al. Outcome of revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(6):531-536.