User login

Rationale for Strategic Graft Placement in Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: I.D.E.A.L. Femoral Tunnel Position

In the United States, surgeons perform an estimated 200,000 anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions (ACLRs) each year. Over the past decade, there has been a surge in interest in defining anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) anatomy to guide ACLR. With this renewed interest in the anatomical features of the ACL, particularly the insertion site, many authors have advocated an approach for complete or near-complete “footprint restoration” for anatomical ACLR.1,2 Some have recommended a double-bundle (DB) technique that completely “fills” the footprint, but it is seldom used. Others have proposed centralizing the femoral tunnel position within the ACL footprint in the hope of capturing the function of both the anteromedial (AM) and posterolateral (PL) bundles.1,3,4 Indeed, a primary surgical goal of most anatomical ACLR techniques is creation of a femoral tunnel based off the anatomical centrum (center point) of the ACL femoral footprint.3,5 With a single-bundle technique, the femoral socket is localized in the center of the entire footprint; with a DB technique, sockets are created in the centrums of both the AM and PL bundles.

Because of the complex shape of the native ACL, however, the strategy of restoring the femoral footprint with use of either a central tunnel or a DB approach has been challenged. The femoral footprint is 3.5 times larger than the midsubstance of the ACL.6 Detailed anatomical dissections have recently demonstrated that the femoral origin of the ACL has a stout anterior band of fibers with a fanlike extension posteriorly.7 As the ACL fibers extend off the bony footprint, they form a flat, ribbonlike structure 9 to 16 mm wide and only 2 to 4 mm thick.2,8 Within this structure, there is no clear separation of the AM and PL bundles. The presence of this structure makes sense given the anatomical constraints inherent in the notch. Indeed, the space for the native ACL is narrow, as the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) occupies that largest portion of the notch with the knee in full extension, leaving only a thin, 5-mm slot through which the ACL must pass.9 Therefore, filling the femoral footprint with a tubular ACL graft probably does not reproduce the dynamic 3-dimensional morphology of the ACL.

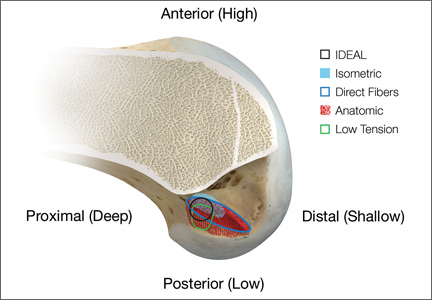

In light of the discrepancy between the sizes of the femoral footprint and the midsubstance of the native ACL, it seems reasonable that optimizing the position of the ACL femoral tunnel may be more complex than simply centralizing the tunnel within the footprint or attempting to maximize footprint coverage. In this article, we amalgamate the lessons of 4 decades of ACL research into 5 points for strategic femoral tunnel positioning, based on anatomical, histologic, isometric, biomechanical, and clinical data. These points are summarized by the acronym I.D.E.A.L., which refers to placing a femoral tunnel in a position that reproduces the Isometry of the native ACL, that covers the fibers of the Direct insertion histologically, that is Eccentrically located in the anterior (high) and proximal (deep) region of the footprint, that is Anatomical (within the footprint), and that replicates the Low tension-flexion pattern of the native ACL throughout the range of flexion and extension.

1. Anatomy Considerations

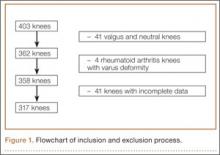

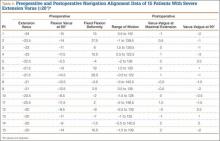

In response to study results demonstrating that some transtibial ACLRs were associated with nonanatomical placement of the femoral tunnel—resulting in vertical graft placement, PCL impingement, and recurrent rotational instability10-16—investigators have reexamined both the anatomy of the femoral origin of the native ACL and the ACL graft. Specifically, a large body of research has been devoted to characterizing the osseous landmarks of the femoral origin of the ACL17 and the dimensions of the femoral footprint.3 In addition, authors have supported the concept that the ACL contains 2 functional bundles, AM and PL.5,17 Several osseous landmarks have been identified as defining the boundaries of the femoral footprint. The lateral intercondylar ridge is the most anterior aspect of the femoral footprint and was first defined by Clancy.18 More recently, the lateral bifurcate ridge, which separates the AM and PL bundle insertion sites, was described19 (Figure 1A).

These osseous ridges delineate the location of the femoral footprint. Studies have shown that ACL fibers attach from the lateral intercondylar ridge on the anterior border of the femoral footprint and extend posteriorly to the cartilage of the lateral femoral condyle (Figure 1B).

ACL fibers from this oblong footprint are organized such that the midsubstance of the ACL is narrower than the femoral footprint. Anatomical dissections have demonstrated that, though the femoral footprint is oval, the native ACL forms a flat, ribbonlike structure 9 to 16 mm wide and only 2 to 4 mm thick as it takes off from the bone.8,20 There is a resulting discrepancy between the femoral footprint size and shape and the morphology of the native ACL, and placing a tunnel in the center of the footprint or “filling the footprint” with ACL graft may not reproduce the morphology or function of the native ACL. Given this size mismatch, strategic decisions need to be made to place the femoral tunnel in a specific region of the femoral footprint to optimize its function.

2. Histologic Findings

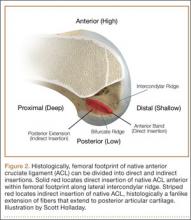

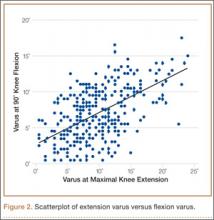

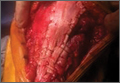

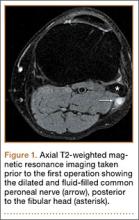

Histologic analysis has further clarified the relationship between the femoral footprint and functional aspects of the native ACL. The femoral origin of the ACL has distinct direct and indirect insertions, as demonstrated by histology and 3-dimensional volume-rendered computed tomography.21 The direct insertion consists of dense collagen fibers anterior in the footprint that is attached to a bony depression immediately posterior to the lateral intercondylar ridge.19 Sasaki and colleagues22 found that these direct fibers extended a mean (SD) of 5.3 (1.1) mm posteriorly but did not continue to the posterior femoral articular cartilage. The indirect insertion consists of more posterior collagen fibers that extend to and blend into the articular cartilage of the posterior aspect of the lateral femoral condyle. Mean (SD) width of this membrane-like tissue, located between the direct insertion and the posterior femoral articular cartilage, was found by Sasaki and colleagues22 to be 4.4 (0.5) mm anteroposteriorly(Figure 2). This anterior band of ACL tissue with the direct insertion histologically corresponds to the fibers in the anterior, more isometric region of the femoral footprint. Conversely, the more posterior band of fibers with its indirect insertion histologically corresponds to the more anisometric region and is seen macroscopically as a fanlike projection extending to the posterior articular cartilage.7

The dense collagen fibers of the direct insertion and the more membrane-like indirect insertion regions of the femoral footprint of the native ACL suggest that these regions have different load-sharing characteristics. The direct fibers of the insertion form a firm, fixed attachment that allows for gradual load distribution into the subchondral bone. From a biomechanical point of view, this attachment is extremely important, a key ligament–bone link transmitting mechanical load to the joint.23 A recent kinematic analysis revealed that the indirect fibers in the posterior region of the footprint, adjacent to the posterior articular cartilage, contribute minimally to restraint of tibial translation and rotations during stability examination.24 This suggests it may be strategically wise to place a tunnel in the direct insertion region of the footprint—eccentrically anterior (high) in the footprint rather than in the centrum.

3. Isometric Considerations

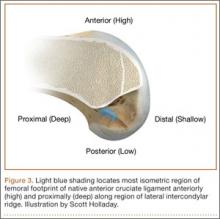

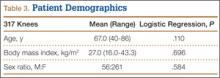

Forty years ago, Artmann and Wirth25 reported that a nearly isometric region existed in the femur such that there is minimal elongation of the native ACL during knee motion. The biomechanical rationale for choosing an isometric region of an ACL graft is that it will maintain function throughout the range of flexion and extension. A nonisometric graft would be expected to slacken during a large portion of the flexion cycle and not restrain anterior translation of the tibia, or, if fixed at the wrong flexion angle, it could capture the knee and cause graft failure by excessive tension. These 2 theoretical undesirable effects from nonisometric graft placement are supported by many experimental and clinical studies demonstrating that nonisometric femoral tunnel placement at time of surgery can cause recurrent anterior laxity of the knee.26-28 Multiple studies have further clarified that the isometric characteristics of an ACL graft are largely determined by femoral positioning. The most isometric region of the femoral footprint is consistently shown to be localized eccentrically within the footprint, in a relatively narrow bandlike region that is proximal (deep) and anterior (along the lateral intercondylar ridge within the footprint)19,29,30 (Figure 3).

A large body of literature has demonstrated that a tunnel placed in the center of the femoral footprint is less isometric than a tunnel in the more anterior region.25,29,31,32 Indeed, the anterior position (high in the footprint) identified by Hefzy and colleagues29 demonstrated minimal anisometry with 1 to 4 mm of length change through the range of motion. In contrast, a central tunnel would be expected to demonstrate 5 to 7 mm of length change, whereas a lower graft (in the PL region of the footprint) would demonstrate about 1 cm of length change through the range of motion.31,32 As such, central grafts, or grafts placed in the PL portion of the femoral footprint, would be expected to see high tension or graft forces as the knee is flexed, or to lose tension completely if the graft is fixed at full extension.32

Importantly, Markolf and colleagues33 reported that the native ACL does not behave exactly in a so-called isometric fashion during the last 30° of extension. They showed that about 3 mm of retraction of a trial wire into the joint during the last 30° of extension (as measured with an isometer) is reasonable to achieve graft length changes approximating those of the intact ACL. Given this important caveat, a primary goal for ACLR is placement of the femoral tunnel within this isometric region so that the length change in the ACL graft is minimized to 3 mm from 30° to full flexion. In addition, results of a time-zero biomechanical study suggested better rotational control with anatomical femoral tunnel position than with an isometric femoral tunnel34 placed outside the femoral footprint. Therefore, maximizing isometry alone is not the goal; placing the graft in the most isometric region within the anatomical femoral footprint is desired. This isometric region in the footprint is in the histologic region that corresponds to the direct fibers. Again, this region is eccentrically located in the anterior (high) and proximal (deep) portion of the footprint.

4. Biomechanical Considerations

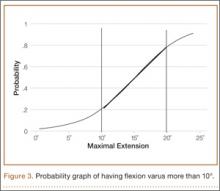

Multiple cadaveric studies have investigated the relationship between femoral tunnel positioning and time-zero stability. These studies often demonstrated superior time-zero control of knee stability, particularly in pivot type maneuvers, with a femoral tunnel placed more centrally in the femoral footprint than with a tunnel placed outside the footprint.34-37 However, an emerging body of literature is finding no significant difference in time-zero stability between an anteriorly placed femoral tunnel within the anatomical footprint (eccentrically located in the footprint) and a centrally placed graft.38,39 Returning to the more isometric tunnel position, still within the femoral footprint, would be expected to confer the benefits of an anatomically based graft position with the advantageous profile of improved isometry, as compared with a centrally placed or PL graft. Biomechanical studies40 have documented that ACL graft fibers placed posteriorly (low) in the footprint cause high graft forces in extension and, in some cases, graft rupture (Figure 4). Accordingly, the importance of reconstructing the posterior region of the footprint to better control time-zero stability is questioned.41

In addition to time-zero control of the stability examination, restoring the low tension-flexion pattern in the ACL graft to replicate the tension-flexion behavior of the native ACL is a fundamental biomechanical principle of ACLR.15,33,42,43 These studies have demonstrated that a femoral tunnel localized anterior (high) and proximal (deep) within the footprint better replicates the tension-flexion behavior of the native ACL, as compared with strategies that attempt to anatomically “fill the footprint.”40 Together, these studies have demonstrated that an eccentric position in the footprint, in the anterior (high) and proximal (deep) region, not only maximizes isometry and restores the direct fibers, but provides favorable time-zero stability and a low tension-flexion pattern biomechanically, particularly as compared with a tunnel in the more central or posterior region of the footprint.

5. Clinical Data

Clinical studies of the traditional transtibial ACLR have shown good results.44,45 However, when the tibial tunnel in the coronal plane was drilled vertical with respect to the medial joint line of the tibia, the transtibially placed femoral tunnel migrated anterior to the anatomical femoral footprint, often on the roof of the notch.10,14 This nonanatomical, vertical placement of the femoral tunnel led to failed normalization of knee kinematics.46-50 Indeed, a higher tension-flexion pattern was found in this nonanatomical “roof” position for the femoral tunnel as compared with the native ACL—a pattern that can result in either loss of flexion or recurrent instability.13,15,51

Clinical results of techniques used to create an anatomical ACLR centrally within the footprint have been mixed. Registry data showed that the revision rate at 4 years was higher with the AM portal technique (5.16%) than with transtibial drilling (3.20%).52 This higher rate may be associated with the more central placement of the femoral tunnel with the AM portal technique than with the transtibial technique, as shown in vivo with high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging.12 Recent reports have documented a higher rate of failure with DB or central ACLR approaches than with traditional transtibial techniques.53 As mentioned, in contrast to a more isometric position, a central femoral tunnel position would be expected to demonstrate 5 to 7 mm of length change, whereas moving the graft more posterior in the footprint (closer to the articular cartilage) would result in more than 1 cm of length change through the range of motion.31,32 As such, these more central grafts, or grafts placed even lower (more posterior) in the footprint, would be expected to see high tension in extension (if fixed in flexion), or to lose tension completely during flexion (if the graft is fixed at full extension).32 This may be a mechanistic cause of the high failure rate in the more posterior bundles of the DB approach.54

Together, these clinical data suggest that the femoral tunnel should be placed within the anatomical footprint of the ACL. However, within the footprint, a more eccentric femoral tunnel position capturing the isometric and direct region of the insertion may be preferable to a more central or posterior (low region) position.

Summary

Anatomical, histologic, isometric, biomechanical, and clinical data from more than 4 decades collectively point to an optimal position for the femoral tunnel within the femoral footprint. This position can be summarized by the acronym I.D.E.A.L., which refers to placing a femoral tunnel in a position that reproduces the Isometry of the native ACL, that covers the fibers of the Direct insertion histologically, that is Eccentrically located in the anterior (high) and proximal (deep) region of the footprint, that is Anatomical (within the footprint), and that replicates the Low tension-flexion pattern of the native ACL throughout the range of flexion and extension (Figure 5).

In vivo and in vitro studies as well as surgical experience suggest a need to avoid both (a) the nonanatomical vertical (roof) femoral tunnel placement that causes PCL impingement, high tension in the ACL graft in flexion, and ultimately graft stretch-out with instability and (b) the femoral tunnel placement in the posterior (lowest) region of the footprint that causes high tension in extension and can result in graft stretch-out with instability.13,15,39,40 The transtibial and AM portal techniques can both be effective in properly placing the femoral tunnel and restoring motion, stability, and function to the knee. Their effectiveness, however, depends on correct placement of the femoral tunnel. We think coming studies will focus on single-bundle ACLR and will be designed to improve the reliability of the transtibial and AM portal techniques for placing a femoral tunnel in keeping with the principles summarized by the I.D.E.A.L. acronym.

1. Siebold R. The concept of complete footprint restoration with guidelines for single- and double-bundle ACL reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(5):699-706.

2. Siebold R, Schuhmacher P. Restoration of the tibial ACL footprint area and geometry using the modified insertion site table. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(9):1845-1849.

3. Piefer JW, Pflugner TR, Hwang MD, Lubowitz JH. Anterior cruciate ligament femoral footprint anatomy: systematic review of the 21st century literature. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(6):872-881.

4. Wilson AJ, Yasen SK, Nancoo T, Stannard R, Smith JO, Logan JS. Anatomic all-inside anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using the translateral technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2013;2(2):e99-e104.

5. Colombet P, Robinson J, Christel P, et al. Morphology of anterior cruciate ligament attachments for anatomic reconstruction: a cadaveric dissection and radiographic study. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(9):984-992.

6. Harner CD, Baek GH, Vogrin TM, Carlin GJ, Kashiwaguchi S, Woo SL. Quantitative analysis of human cruciate ligament insertions. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(7):741-749.

7. Mochizuki T, Fujishiro H, Nimura A, et al. Anatomic and histologic analysis of the mid-substance and fan-like extension fibres of the anterior cruciate ligament during knee motion, with special reference to the femoral attachment. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(2):336-344.

8. Siebold R, Schuhmacher P, Fernandez F, et al. Flat midsubstance of the anterior cruciate ligament with tibial “C”-shaped insertion site [published correction appears in Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014 Aug 23. Epub ahead of print]. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014 May 20. [Epub ahead of print]

9. Triantafyllidi E, Paschos NK, Goussia A, et al. The shape and the thickness of the anterior cruciate ligament along its length in relation to the posterior cruciate ligament: a cadaveric study. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(12):1963-1973.

10. Arnold MP, Kooloos J, van Kampen A. Single-incision technique misses the anatomical femoral anterior cruciate ligament insertion: a cadaver study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2001;9(4):194-199.

11. Ayerza MA, Múscolo DL, Costa-Paz M, Makino A, Rondón L. Comparison of sagittal obliquity of the reconstructed anterior cruciate ligament with native anterior cruciate ligament using magnetic resonance imaging. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(3):257-261.

12. Bowers AL, Bedi A, Lipman JD, et al. Comparison of anterior cruciate ligament tunnel position and graft obliquity with transtibial and anteromedial portal femoral tunnel reaming techniques using high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(11):1511-1522.

13. Howell SM, Gittins ME, Gottlieb JE, Traina SM, Zoellner TM. The relationship between the angle of the tibial tunnel in the coronal plane and loss of flexion and anterior laxity after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(5):567-574.

14. Kopf S, Forsythe B, Wong AK, et al. Nonanatomic tunnel position in traditional transtibial single-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction evaluated by three-dimensional computed tomography. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(6):1427-1431.

15. Simmons R, Howell SM, Hull ML. Effect of the angle of the femoral and tibial tunnels in the coronal plane and incremental excision of the posterior cruciate ligament on tension of an anterior cruciate ligament graft: an in vitro study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(6):1018-1029.

16. Stanford FC, Kendoff D, Warren RF, Pearle AD. Native anterior cruciate ligament obliquity versus anterior cruciate ligament graft obliquity: an observational study using navigated measurements. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(1):114-119.

17. Ferretti M, Ekdahl M, Shen W, Fu FH. Osseous landmarks of the femoral attachment of the anterior cruciate ligament: an anatomic study. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(11):1218-1225.

18. Hutchinson MR, Ash SA. Resident’s ridge: assessing the cortical thickness of the lateral wall and roof of the intercondylar notch. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(9):931-935.

19. Fu FH, Jordan SS. The lateral intercondylar ridge—a key to anatomic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(10):2103-2104.

20. Smigielski R, Zdanowicz U, Drwięga M, Ciszek B, Ciszkowska-Łysoń B, Siebold R. Ribbon like appearance of the midsubstance fibres of the anterior cruciate ligament close to its femoral insertion site: a cadaveric study including 111 knees. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014 Jun 28. [Epub ahead of print]

21. Iwahashi T, Shino K, Nakata K, et al. Direct anterior cruciate ligament insertion to the femur assessed by histology and 3-dimensional volume-rendered computed tomography. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(9 suppl):S13-S20.

22. Sasaki N, Ishibashi Y, Tsuda E, et al. The femoral insertion of the anterior cruciate ligament: discrepancy between macroscopic and histological observations. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(8):1135-1146.

23. Benjamin M, Moriggl B, Brenner E, Emery P, McGonagle D, Redman S. The “enthesis organ” concept: why enthesopathies may not present as focal insertional disorders. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(10):3306-3313.

24. Pathare NP, Nicholas SJ, Colbrunn R, McHugh MP. Kinematic analysis of the indirect femoral insertion of the anterior cruciate ligament: implications for anatomic femoral tunnel placement. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(11):1430-1438.

25. Artmann M, Wirth CJ. Investigation of the appropriate functional replacement of the anterior cruciate ligament (author’s transl) [in German]. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1974;112(1):160-165.

26. Amis AA, Jakob RP. Anterior cruciate ligament graft positioning, tensioning and twisting. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1998;(6 suppl 1):S2-S12.

27. Beynnon BD, Uh BS, Johnson RJ, Fleming BC, Renström PA, Nichols CE. The elongation behavior of the anterior cruciate ligament graft in vivo. A long-term follow-up study. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(2):161-166.

28. O’Meara PM, O’Brien WR, Henning CE. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction stability with continuous passive motion. The role of isometric graft placement. Clin Orthop. 1992;(277):201-209.

29. Hefzy MS, Grood ES, Noyes FR. Factors affecting the region of most isometric femoral attachments. Part II: the anterior cruciate ligament. Am J Sports Med. 1989;17(2):208-216.

30. Zavras TD, Race A, Bull AM, Amis AA. A comparative study of ‘isometric’ points for anterior cruciate ligament graft attachment. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2001;9(1):28-33.

31. Pearle AD, Shannon FJ, Granchi C, Wickiewicz TL, Warren RF. Comparison of 3-dimensional obliquity and anisometric characteristics of anterior cruciate ligament graft positions using surgical navigation. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(8):1534-1541.

32. Lubowitz JH. Anatomic ACL reconstruction produces greater graft length change during knee range-of-motion than transtibial technique. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(5):1190-1195.

33. Markolf KL, Burchfield DM, Shapiro MM, Davis BR, Finerman GA, Slauterbeck JL. Biomechanical consequences of replacement of the anterior cruciate ligament with a patellar ligament allograft. Part I: insertion of the graft and anterior-posterior testing. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(11):1720-1727.

34. Musahl V, Plakseychuk A, VanScyoc A, et al. Varying femoral tunnels between the anatomical footprint and isometric positions: effect on kinematics of the anterior cruciate ligament-reconstructed knee. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(5):712-718.

35. Bedi A, Musahl V, Steuber V, et al. Transtibial versus anteromedial portal reaming in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: an anatomic and biomechanical evaluation of surgical technique. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(3):380-390.

36. Lim HC, Yoon YC, Wang JH, Bae JH. Anatomical versus non-anatomical single bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a cadaveric study of comparison of knee stability. Clin Orthop Surg. 2012;4(4):249-255.

37. Loh JC, Fukuda Y, Tsuda E, Steadman RJ, Fu FH, Woo SL. Knee stability and graft function following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: comparison between 11 o’clock and 10 o’clock femoral tunnel placement. 2002 Richard O’Connor Award paper. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(3):297-304.

38. Cross MB, Musahl V, Bedi A, et al. Anteromedial versus central single-bundle graft position: which anatomic graft position to choose? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(7):1276-1281.

39. Markolf KL, Jackson SR, McAllister DR. A comparison of 11 o’clock versus oblique femoral tunnels in the anterior cruciate ligament–reconstructed knee: knee kinematics during a simulated pivot test. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(5):912-917.

40. Markolf KL, Park S, Jackson SR, McAllister DR. Anterior-posterior and rotatory stability of single and double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(1):107-118.

41. Markolf KL, Park S, Jackson SR, McAllister DR. Contributions of the posterolateral bundle of the anterior cruciate ligament to anterior-posterior knee laxity and ligament forces. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(7):805-809.

42. Markolf KL, Burchfield DM, Shapiro MM, Cha CW, Finerman GA, Slauterbeck JL. Biomechanical consequences of replacement of the anterior cruciate ligament with a patellar ligament allograft. Part II: forces in the graft compared with forces in the intact ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(11):1728-1734.

43. Wallace MP, Howell SM, Hull ML. In vivo tensile behavior of a four-bundle hamstring graft as a replacement for the anterior cruciate ligament. J Orthop Res. 1997;15(4):539-545.

44. Harner CD, Marks PH, Fu FH, Irrgang JJ, Silby MB, Mengato R. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: endoscopic versus two-incision technique. Arthroscopy. 1994;10(5):502-512.

45. Howell SM, Deutsch ML. Comparison of endoscopic and two-incision technique for reconstructing a torn anterior cruciate ligament using hamstring tendons. J Arthroscopy. 1999;15(6):594-606.

46. Chouliaras V, Ristanis S, Moraiti C, Stergiou N, Georgoulis AD. Effectiveness of reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament with quadrupled hamstrings and bone–patellar tendon–bone autografts: an in vivo study comparing tibial internal–external rotation. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(2):189-196.

47. Logan MC, Williams A, Lavelle J, Gedroyc W, Freeman M. Tibiofemoral kinematics following successful anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using dynamic multiple resonance imaging. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(4):984-992.

48. Papannagari R, Gill TJ, Defrate LE, Moses JM, Petruska AJ, Li G. In vivo kinematics of the knee after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a clinical and functional evaluation. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(12):2006-2012.

49. Tashman S, Collon D, Anderson K, Kolowich P, Anderst W. Abnormal rotational knee motion during running after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(4):975-983.

50. Tashman S, Kolowich P, Collon D, Anderson K, Anderst W. Dynamic function of the ACL-reconstructed knee during running. Clin Orthop. 2007;(454):66-73.

51. Wallace MP, Hull ML, Howell SM. Can an isometer predict the tensile behavior of a double-looped hamstring graft during anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction? J Orthop Res. 1998;16(3):386-393.

52. Rahr-Wagner L, Thillemann TM, Pedersen AB, Lind MC. Increased risk of revision after anteromedial compared with transtibial drilling of the femoral tunnel during primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: results from the Danish Knee Ligament Reconstruction Register. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(1):98-105.

53. van Eck CF, Schkrohowsky JG, Working ZM, Irrgang JJ, Fu FH. Prospective analysis of failure rate and predictors of failure after anatomic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with allograft. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(4):800-807.

54. Ahn JH, Choi SH, Wang JH, Yoo JC, Yim HS, Chang MJ. Outcomes and second-look arthroscopic evaluation after double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with use of a single tibial tunnel. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(20):1865-1872.

In the United States, surgeons perform an estimated 200,000 anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions (ACLRs) each year. Over the past decade, there has been a surge in interest in defining anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) anatomy to guide ACLR. With this renewed interest in the anatomical features of the ACL, particularly the insertion site, many authors have advocated an approach for complete or near-complete “footprint restoration” for anatomical ACLR.1,2 Some have recommended a double-bundle (DB) technique that completely “fills” the footprint, but it is seldom used. Others have proposed centralizing the femoral tunnel position within the ACL footprint in the hope of capturing the function of both the anteromedial (AM) and posterolateral (PL) bundles.1,3,4 Indeed, a primary surgical goal of most anatomical ACLR techniques is creation of a femoral tunnel based off the anatomical centrum (center point) of the ACL femoral footprint.3,5 With a single-bundle technique, the femoral socket is localized in the center of the entire footprint; with a DB technique, sockets are created in the centrums of both the AM and PL bundles.

Because of the complex shape of the native ACL, however, the strategy of restoring the femoral footprint with use of either a central tunnel or a DB approach has been challenged. The femoral footprint is 3.5 times larger than the midsubstance of the ACL.6 Detailed anatomical dissections have recently demonstrated that the femoral origin of the ACL has a stout anterior band of fibers with a fanlike extension posteriorly.7 As the ACL fibers extend off the bony footprint, they form a flat, ribbonlike structure 9 to 16 mm wide and only 2 to 4 mm thick.2,8 Within this structure, there is no clear separation of the AM and PL bundles. The presence of this structure makes sense given the anatomical constraints inherent in the notch. Indeed, the space for the native ACL is narrow, as the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) occupies that largest portion of the notch with the knee in full extension, leaving only a thin, 5-mm slot through which the ACL must pass.9 Therefore, filling the femoral footprint with a tubular ACL graft probably does not reproduce the dynamic 3-dimensional morphology of the ACL.

In light of the discrepancy between the sizes of the femoral footprint and the midsubstance of the native ACL, it seems reasonable that optimizing the position of the ACL femoral tunnel may be more complex than simply centralizing the tunnel within the footprint or attempting to maximize footprint coverage. In this article, we amalgamate the lessons of 4 decades of ACL research into 5 points for strategic femoral tunnel positioning, based on anatomical, histologic, isometric, biomechanical, and clinical data. These points are summarized by the acronym I.D.E.A.L., which refers to placing a femoral tunnel in a position that reproduces the Isometry of the native ACL, that covers the fibers of the Direct insertion histologically, that is Eccentrically located in the anterior (high) and proximal (deep) region of the footprint, that is Anatomical (within the footprint), and that replicates the Low tension-flexion pattern of the native ACL throughout the range of flexion and extension.

1. Anatomy Considerations

In response to study results demonstrating that some transtibial ACLRs were associated with nonanatomical placement of the femoral tunnel—resulting in vertical graft placement, PCL impingement, and recurrent rotational instability10-16—investigators have reexamined both the anatomy of the femoral origin of the native ACL and the ACL graft. Specifically, a large body of research has been devoted to characterizing the osseous landmarks of the femoral origin of the ACL17 and the dimensions of the femoral footprint.3 In addition, authors have supported the concept that the ACL contains 2 functional bundles, AM and PL.5,17 Several osseous landmarks have been identified as defining the boundaries of the femoral footprint. The lateral intercondylar ridge is the most anterior aspect of the femoral footprint and was first defined by Clancy.18 More recently, the lateral bifurcate ridge, which separates the AM and PL bundle insertion sites, was described19 (Figure 1A).

These osseous ridges delineate the location of the femoral footprint. Studies have shown that ACL fibers attach from the lateral intercondylar ridge on the anterior border of the femoral footprint and extend posteriorly to the cartilage of the lateral femoral condyle (Figure 1B).

ACL fibers from this oblong footprint are organized such that the midsubstance of the ACL is narrower than the femoral footprint. Anatomical dissections have demonstrated that, though the femoral footprint is oval, the native ACL forms a flat, ribbonlike structure 9 to 16 mm wide and only 2 to 4 mm thick as it takes off from the bone.8,20 There is a resulting discrepancy between the femoral footprint size and shape and the morphology of the native ACL, and placing a tunnel in the center of the footprint or “filling the footprint” with ACL graft may not reproduce the morphology or function of the native ACL. Given this size mismatch, strategic decisions need to be made to place the femoral tunnel in a specific region of the femoral footprint to optimize its function.

2. Histologic Findings

Histologic analysis has further clarified the relationship between the femoral footprint and functional aspects of the native ACL. The femoral origin of the ACL has distinct direct and indirect insertions, as demonstrated by histology and 3-dimensional volume-rendered computed tomography.21 The direct insertion consists of dense collagen fibers anterior in the footprint that is attached to a bony depression immediately posterior to the lateral intercondylar ridge.19 Sasaki and colleagues22 found that these direct fibers extended a mean (SD) of 5.3 (1.1) mm posteriorly but did not continue to the posterior femoral articular cartilage. The indirect insertion consists of more posterior collagen fibers that extend to and blend into the articular cartilage of the posterior aspect of the lateral femoral condyle. Mean (SD) width of this membrane-like tissue, located between the direct insertion and the posterior femoral articular cartilage, was found by Sasaki and colleagues22 to be 4.4 (0.5) mm anteroposteriorly(Figure 2). This anterior band of ACL tissue with the direct insertion histologically corresponds to the fibers in the anterior, more isometric region of the femoral footprint. Conversely, the more posterior band of fibers with its indirect insertion histologically corresponds to the more anisometric region and is seen macroscopically as a fanlike projection extending to the posterior articular cartilage.7

The dense collagen fibers of the direct insertion and the more membrane-like indirect insertion regions of the femoral footprint of the native ACL suggest that these regions have different load-sharing characteristics. The direct fibers of the insertion form a firm, fixed attachment that allows for gradual load distribution into the subchondral bone. From a biomechanical point of view, this attachment is extremely important, a key ligament–bone link transmitting mechanical load to the joint.23 A recent kinematic analysis revealed that the indirect fibers in the posterior region of the footprint, adjacent to the posterior articular cartilage, contribute minimally to restraint of tibial translation and rotations during stability examination.24 This suggests it may be strategically wise to place a tunnel in the direct insertion region of the footprint—eccentrically anterior (high) in the footprint rather than in the centrum.

3. Isometric Considerations

Forty years ago, Artmann and Wirth25 reported that a nearly isometric region existed in the femur such that there is minimal elongation of the native ACL during knee motion. The biomechanical rationale for choosing an isometric region of an ACL graft is that it will maintain function throughout the range of flexion and extension. A nonisometric graft would be expected to slacken during a large portion of the flexion cycle and not restrain anterior translation of the tibia, or, if fixed at the wrong flexion angle, it could capture the knee and cause graft failure by excessive tension. These 2 theoretical undesirable effects from nonisometric graft placement are supported by many experimental and clinical studies demonstrating that nonisometric femoral tunnel placement at time of surgery can cause recurrent anterior laxity of the knee.26-28 Multiple studies have further clarified that the isometric characteristics of an ACL graft are largely determined by femoral positioning. The most isometric region of the femoral footprint is consistently shown to be localized eccentrically within the footprint, in a relatively narrow bandlike region that is proximal (deep) and anterior (along the lateral intercondylar ridge within the footprint)19,29,30 (Figure 3).

A large body of literature has demonstrated that a tunnel placed in the center of the femoral footprint is less isometric than a tunnel in the more anterior region.25,29,31,32 Indeed, the anterior position (high in the footprint) identified by Hefzy and colleagues29 demonstrated minimal anisometry with 1 to 4 mm of length change through the range of motion. In contrast, a central tunnel would be expected to demonstrate 5 to 7 mm of length change, whereas a lower graft (in the PL region of the footprint) would demonstrate about 1 cm of length change through the range of motion.31,32 As such, central grafts, or grafts placed in the PL portion of the femoral footprint, would be expected to see high tension or graft forces as the knee is flexed, or to lose tension completely if the graft is fixed at full extension.32

Importantly, Markolf and colleagues33 reported that the native ACL does not behave exactly in a so-called isometric fashion during the last 30° of extension. They showed that about 3 mm of retraction of a trial wire into the joint during the last 30° of extension (as measured with an isometer) is reasonable to achieve graft length changes approximating those of the intact ACL. Given this important caveat, a primary goal for ACLR is placement of the femoral tunnel within this isometric region so that the length change in the ACL graft is minimized to 3 mm from 30° to full flexion. In addition, results of a time-zero biomechanical study suggested better rotational control with anatomical femoral tunnel position than with an isometric femoral tunnel34 placed outside the femoral footprint. Therefore, maximizing isometry alone is not the goal; placing the graft in the most isometric region within the anatomical femoral footprint is desired. This isometric region in the footprint is in the histologic region that corresponds to the direct fibers. Again, this region is eccentrically located in the anterior (high) and proximal (deep) portion of the footprint.

4. Biomechanical Considerations

Multiple cadaveric studies have investigated the relationship between femoral tunnel positioning and time-zero stability. These studies often demonstrated superior time-zero control of knee stability, particularly in pivot type maneuvers, with a femoral tunnel placed more centrally in the femoral footprint than with a tunnel placed outside the footprint.34-37 However, an emerging body of literature is finding no significant difference in time-zero stability between an anteriorly placed femoral tunnel within the anatomical footprint (eccentrically located in the footprint) and a centrally placed graft.38,39 Returning to the more isometric tunnel position, still within the femoral footprint, would be expected to confer the benefits of an anatomically based graft position with the advantageous profile of improved isometry, as compared with a centrally placed or PL graft. Biomechanical studies40 have documented that ACL graft fibers placed posteriorly (low) in the footprint cause high graft forces in extension and, in some cases, graft rupture (Figure 4). Accordingly, the importance of reconstructing the posterior region of the footprint to better control time-zero stability is questioned.41

In addition to time-zero control of the stability examination, restoring the low tension-flexion pattern in the ACL graft to replicate the tension-flexion behavior of the native ACL is a fundamental biomechanical principle of ACLR.15,33,42,43 These studies have demonstrated that a femoral tunnel localized anterior (high) and proximal (deep) within the footprint better replicates the tension-flexion behavior of the native ACL, as compared with strategies that attempt to anatomically “fill the footprint.”40 Together, these studies have demonstrated that an eccentric position in the footprint, in the anterior (high) and proximal (deep) region, not only maximizes isometry and restores the direct fibers, but provides favorable time-zero stability and a low tension-flexion pattern biomechanically, particularly as compared with a tunnel in the more central or posterior region of the footprint.

5. Clinical Data

Clinical studies of the traditional transtibial ACLR have shown good results.44,45 However, when the tibial tunnel in the coronal plane was drilled vertical with respect to the medial joint line of the tibia, the transtibially placed femoral tunnel migrated anterior to the anatomical femoral footprint, often on the roof of the notch.10,14 This nonanatomical, vertical placement of the femoral tunnel led to failed normalization of knee kinematics.46-50 Indeed, a higher tension-flexion pattern was found in this nonanatomical “roof” position for the femoral tunnel as compared with the native ACL—a pattern that can result in either loss of flexion or recurrent instability.13,15,51

Clinical results of techniques used to create an anatomical ACLR centrally within the footprint have been mixed. Registry data showed that the revision rate at 4 years was higher with the AM portal technique (5.16%) than with transtibial drilling (3.20%).52 This higher rate may be associated with the more central placement of the femoral tunnel with the AM portal technique than with the transtibial technique, as shown in vivo with high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging.12 Recent reports have documented a higher rate of failure with DB or central ACLR approaches than with traditional transtibial techniques.53 As mentioned, in contrast to a more isometric position, a central femoral tunnel position would be expected to demonstrate 5 to 7 mm of length change, whereas moving the graft more posterior in the footprint (closer to the articular cartilage) would result in more than 1 cm of length change through the range of motion.31,32 As such, these more central grafts, or grafts placed even lower (more posterior) in the footprint, would be expected to see high tension in extension (if fixed in flexion), or to lose tension completely during flexion (if the graft is fixed at full extension).32 This may be a mechanistic cause of the high failure rate in the more posterior bundles of the DB approach.54

Together, these clinical data suggest that the femoral tunnel should be placed within the anatomical footprint of the ACL. However, within the footprint, a more eccentric femoral tunnel position capturing the isometric and direct region of the insertion may be preferable to a more central or posterior (low region) position.

Summary

Anatomical, histologic, isometric, biomechanical, and clinical data from more than 4 decades collectively point to an optimal position for the femoral tunnel within the femoral footprint. This position can be summarized by the acronym I.D.E.A.L., which refers to placing a femoral tunnel in a position that reproduces the Isometry of the native ACL, that covers the fibers of the Direct insertion histologically, that is Eccentrically located in the anterior (high) and proximal (deep) region of the footprint, that is Anatomical (within the footprint), and that replicates the Low tension-flexion pattern of the native ACL throughout the range of flexion and extension (Figure 5).

In vivo and in vitro studies as well as surgical experience suggest a need to avoid both (a) the nonanatomical vertical (roof) femoral tunnel placement that causes PCL impingement, high tension in the ACL graft in flexion, and ultimately graft stretch-out with instability and (b) the femoral tunnel placement in the posterior (lowest) region of the footprint that causes high tension in extension and can result in graft stretch-out with instability.13,15,39,40 The transtibial and AM portal techniques can both be effective in properly placing the femoral tunnel and restoring motion, stability, and function to the knee. Their effectiveness, however, depends on correct placement of the femoral tunnel. We think coming studies will focus on single-bundle ACLR and will be designed to improve the reliability of the transtibial and AM portal techniques for placing a femoral tunnel in keeping with the principles summarized by the I.D.E.A.L. acronym.

In the United States, surgeons perform an estimated 200,000 anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions (ACLRs) each year. Over the past decade, there has been a surge in interest in defining anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) anatomy to guide ACLR. With this renewed interest in the anatomical features of the ACL, particularly the insertion site, many authors have advocated an approach for complete or near-complete “footprint restoration” for anatomical ACLR.1,2 Some have recommended a double-bundle (DB) technique that completely “fills” the footprint, but it is seldom used. Others have proposed centralizing the femoral tunnel position within the ACL footprint in the hope of capturing the function of both the anteromedial (AM) and posterolateral (PL) bundles.1,3,4 Indeed, a primary surgical goal of most anatomical ACLR techniques is creation of a femoral tunnel based off the anatomical centrum (center point) of the ACL femoral footprint.3,5 With a single-bundle technique, the femoral socket is localized in the center of the entire footprint; with a DB technique, sockets are created in the centrums of both the AM and PL bundles.

Because of the complex shape of the native ACL, however, the strategy of restoring the femoral footprint with use of either a central tunnel or a DB approach has been challenged. The femoral footprint is 3.5 times larger than the midsubstance of the ACL.6 Detailed anatomical dissections have recently demonstrated that the femoral origin of the ACL has a stout anterior band of fibers with a fanlike extension posteriorly.7 As the ACL fibers extend off the bony footprint, they form a flat, ribbonlike structure 9 to 16 mm wide and only 2 to 4 mm thick.2,8 Within this structure, there is no clear separation of the AM and PL bundles. The presence of this structure makes sense given the anatomical constraints inherent in the notch. Indeed, the space for the native ACL is narrow, as the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) occupies that largest portion of the notch with the knee in full extension, leaving only a thin, 5-mm slot through which the ACL must pass.9 Therefore, filling the femoral footprint with a tubular ACL graft probably does not reproduce the dynamic 3-dimensional morphology of the ACL.

In light of the discrepancy between the sizes of the femoral footprint and the midsubstance of the native ACL, it seems reasonable that optimizing the position of the ACL femoral tunnel may be more complex than simply centralizing the tunnel within the footprint or attempting to maximize footprint coverage. In this article, we amalgamate the lessons of 4 decades of ACL research into 5 points for strategic femoral tunnel positioning, based on anatomical, histologic, isometric, biomechanical, and clinical data. These points are summarized by the acronym I.D.E.A.L., which refers to placing a femoral tunnel in a position that reproduces the Isometry of the native ACL, that covers the fibers of the Direct insertion histologically, that is Eccentrically located in the anterior (high) and proximal (deep) region of the footprint, that is Anatomical (within the footprint), and that replicates the Low tension-flexion pattern of the native ACL throughout the range of flexion and extension.

1. Anatomy Considerations

In response to study results demonstrating that some transtibial ACLRs were associated with nonanatomical placement of the femoral tunnel—resulting in vertical graft placement, PCL impingement, and recurrent rotational instability10-16—investigators have reexamined both the anatomy of the femoral origin of the native ACL and the ACL graft. Specifically, a large body of research has been devoted to characterizing the osseous landmarks of the femoral origin of the ACL17 and the dimensions of the femoral footprint.3 In addition, authors have supported the concept that the ACL contains 2 functional bundles, AM and PL.5,17 Several osseous landmarks have been identified as defining the boundaries of the femoral footprint. The lateral intercondylar ridge is the most anterior aspect of the femoral footprint and was first defined by Clancy.18 More recently, the lateral bifurcate ridge, which separates the AM and PL bundle insertion sites, was described19 (Figure 1A).

These osseous ridges delineate the location of the femoral footprint. Studies have shown that ACL fibers attach from the lateral intercondylar ridge on the anterior border of the femoral footprint and extend posteriorly to the cartilage of the lateral femoral condyle (Figure 1B).

ACL fibers from this oblong footprint are organized such that the midsubstance of the ACL is narrower than the femoral footprint. Anatomical dissections have demonstrated that, though the femoral footprint is oval, the native ACL forms a flat, ribbonlike structure 9 to 16 mm wide and only 2 to 4 mm thick as it takes off from the bone.8,20 There is a resulting discrepancy between the femoral footprint size and shape and the morphology of the native ACL, and placing a tunnel in the center of the footprint or “filling the footprint” with ACL graft may not reproduce the morphology or function of the native ACL. Given this size mismatch, strategic decisions need to be made to place the femoral tunnel in a specific region of the femoral footprint to optimize its function.

2. Histologic Findings

Histologic analysis has further clarified the relationship between the femoral footprint and functional aspects of the native ACL. The femoral origin of the ACL has distinct direct and indirect insertions, as demonstrated by histology and 3-dimensional volume-rendered computed tomography.21 The direct insertion consists of dense collagen fibers anterior in the footprint that is attached to a bony depression immediately posterior to the lateral intercondylar ridge.19 Sasaki and colleagues22 found that these direct fibers extended a mean (SD) of 5.3 (1.1) mm posteriorly but did not continue to the posterior femoral articular cartilage. The indirect insertion consists of more posterior collagen fibers that extend to and blend into the articular cartilage of the posterior aspect of the lateral femoral condyle. Mean (SD) width of this membrane-like tissue, located between the direct insertion and the posterior femoral articular cartilage, was found by Sasaki and colleagues22 to be 4.4 (0.5) mm anteroposteriorly(Figure 2). This anterior band of ACL tissue with the direct insertion histologically corresponds to the fibers in the anterior, more isometric region of the femoral footprint. Conversely, the more posterior band of fibers with its indirect insertion histologically corresponds to the more anisometric region and is seen macroscopically as a fanlike projection extending to the posterior articular cartilage.7

The dense collagen fibers of the direct insertion and the more membrane-like indirect insertion regions of the femoral footprint of the native ACL suggest that these regions have different load-sharing characteristics. The direct fibers of the insertion form a firm, fixed attachment that allows for gradual load distribution into the subchondral bone. From a biomechanical point of view, this attachment is extremely important, a key ligament–bone link transmitting mechanical load to the joint.23 A recent kinematic analysis revealed that the indirect fibers in the posterior region of the footprint, adjacent to the posterior articular cartilage, contribute minimally to restraint of tibial translation and rotations during stability examination.24 This suggests it may be strategically wise to place a tunnel in the direct insertion region of the footprint—eccentrically anterior (high) in the footprint rather than in the centrum.

3. Isometric Considerations

Forty years ago, Artmann and Wirth25 reported that a nearly isometric region existed in the femur such that there is minimal elongation of the native ACL during knee motion. The biomechanical rationale for choosing an isometric region of an ACL graft is that it will maintain function throughout the range of flexion and extension. A nonisometric graft would be expected to slacken during a large portion of the flexion cycle and not restrain anterior translation of the tibia, or, if fixed at the wrong flexion angle, it could capture the knee and cause graft failure by excessive tension. These 2 theoretical undesirable effects from nonisometric graft placement are supported by many experimental and clinical studies demonstrating that nonisometric femoral tunnel placement at time of surgery can cause recurrent anterior laxity of the knee.26-28 Multiple studies have further clarified that the isometric characteristics of an ACL graft are largely determined by femoral positioning. The most isometric region of the femoral footprint is consistently shown to be localized eccentrically within the footprint, in a relatively narrow bandlike region that is proximal (deep) and anterior (along the lateral intercondylar ridge within the footprint)19,29,30 (Figure 3).

A large body of literature has demonstrated that a tunnel placed in the center of the femoral footprint is less isometric than a tunnel in the more anterior region.25,29,31,32 Indeed, the anterior position (high in the footprint) identified by Hefzy and colleagues29 demonstrated minimal anisometry with 1 to 4 mm of length change through the range of motion. In contrast, a central tunnel would be expected to demonstrate 5 to 7 mm of length change, whereas a lower graft (in the PL region of the footprint) would demonstrate about 1 cm of length change through the range of motion.31,32 As such, central grafts, or grafts placed in the PL portion of the femoral footprint, would be expected to see high tension or graft forces as the knee is flexed, or to lose tension completely if the graft is fixed at full extension.32

Importantly, Markolf and colleagues33 reported that the native ACL does not behave exactly in a so-called isometric fashion during the last 30° of extension. They showed that about 3 mm of retraction of a trial wire into the joint during the last 30° of extension (as measured with an isometer) is reasonable to achieve graft length changes approximating those of the intact ACL. Given this important caveat, a primary goal for ACLR is placement of the femoral tunnel within this isometric region so that the length change in the ACL graft is minimized to 3 mm from 30° to full flexion. In addition, results of a time-zero biomechanical study suggested better rotational control with anatomical femoral tunnel position than with an isometric femoral tunnel34 placed outside the femoral footprint. Therefore, maximizing isometry alone is not the goal; placing the graft in the most isometric region within the anatomical femoral footprint is desired. This isometric region in the footprint is in the histologic region that corresponds to the direct fibers. Again, this region is eccentrically located in the anterior (high) and proximal (deep) portion of the footprint.

4. Biomechanical Considerations

Multiple cadaveric studies have investigated the relationship between femoral tunnel positioning and time-zero stability. These studies often demonstrated superior time-zero control of knee stability, particularly in pivot type maneuvers, with a femoral tunnel placed more centrally in the femoral footprint than with a tunnel placed outside the footprint.34-37 However, an emerging body of literature is finding no significant difference in time-zero stability between an anteriorly placed femoral tunnel within the anatomical footprint (eccentrically located in the footprint) and a centrally placed graft.38,39 Returning to the more isometric tunnel position, still within the femoral footprint, would be expected to confer the benefits of an anatomically based graft position with the advantageous profile of improved isometry, as compared with a centrally placed or PL graft. Biomechanical studies40 have documented that ACL graft fibers placed posteriorly (low) in the footprint cause high graft forces in extension and, in some cases, graft rupture (Figure 4). Accordingly, the importance of reconstructing the posterior region of the footprint to better control time-zero stability is questioned.41

In addition to time-zero control of the stability examination, restoring the low tension-flexion pattern in the ACL graft to replicate the tension-flexion behavior of the native ACL is a fundamental biomechanical principle of ACLR.15,33,42,43 These studies have demonstrated that a femoral tunnel localized anterior (high) and proximal (deep) within the footprint better replicates the tension-flexion behavior of the native ACL, as compared with strategies that attempt to anatomically “fill the footprint.”40 Together, these studies have demonstrated that an eccentric position in the footprint, in the anterior (high) and proximal (deep) region, not only maximizes isometry and restores the direct fibers, but provides favorable time-zero stability and a low tension-flexion pattern biomechanically, particularly as compared with a tunnel in the more central or posterior region of the footprint.

5. Clinical Data

Clinical studies of the traditional transtibial ACLR have shown good results.44,45 However, when the tibial tunnel in the coronal plane was drilled vertical with respect to the medial joint line of the tibia, the transtibially placed femoral tunnel migrated anterior to the anatomical femoral footprint, often on the roof of the notch.10,14 This nonanatomical, vertical placement of the femoral tunnel led to failed normalization of knee kinematics.46-50 Indeed, a higher tension-flexion pattern was found in this nonanatomical “roof” position for the femoral tunnel as compared with the native ACL—a pattern that can result in either loss of flexion or recurrent instability.13,15,51

Clinical results of techniques used to create an anatomical ACLR centrally within the footprint have been mixed. Registry data showed that the revision rate at 4 years was higher with the AM portal technique (5.16%) than with transtibial drilling (3.20%).52 This higher rate may be associated with the more central placement of the femoral tunnel with the AM portal technique than with the transtibial technique, as shown in vivo with high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging.12 Recent reports have documented a higher rate of failure with DB or central ACLR approaches than with traditional transtibial techniques.53 As mentioned, in contrast to a more isometric position, a central femoral tunnel position would be expected to demonstrate 5 to 7 mm of length change, whereas moving the graft more posterior in the footprint (closer to the articular cartilage) would result in more than 1 cm of length change through the range of motion.31,32 As such, these more central grafts, or grafts placed even lower (more posterior) in the footprint, would be expected to see high tension in extension (if fixed in flexion), or to lose tension completely during flexion (if the graft is fixed at full extension).32 This may be a mechanistic cause of the high failure rate in the more posterior bundles of the DB approach.54

Together, these clinical data suggest that the femoral tunnel should be placed within the anatomical footprint of the ACL. However, within the footprint, a more eccentric femoral tunnel position capturing the isometric and direct region of the insertion may be preferable to a more central or posterior (low region) position.

Summary

Anatomical, histologic, isometric, biomechanical, and clinical data from more than 4 decades collectively point to an optimal position for the femoral tunnel within the femoral footprint. This position can be summarized by the acronym I.D.E.A.L., which refers to placing a femoral tunnel in a position that reproduces the Isometry of the native ACL, that covers the fibers of the Direct insertion histologically, that is Eccentrically located in the anterior (high) and proximal (deep) region of the footprint, that is Anatomical (within the footprint), and that replicates the Low tension-flexion pattern of the native ACL throughout the range of flexion and extension (Figure 5).

In vivo and in vitro studies as well as surgical experience suggest a need to avoid both (a) the nonanatomical vertical (roof) femoral tunnel placement that causes PCL impingement, high tension in the ACL graft in flexion, and ultimately graft stretch-out with instability and (b) the femoral tunnel placement in the posterior (lowest) region of the footprint that causes high tension in extension and can result in graft stretch-out with instability.13,15,39,40 The transtibial and AM portal techniques can both be effective in properly placing the femoral tunnel and restoring motion, stability, and function to the knee. Their effectiveness, however, depends on correct placement of the femoral tunnel. We think coming studies will focus on single-bundle ACLR and will be designed to improve the reliability of the transtibial and AM portal techniques for placing a femoral tunnel in keeping with the principles summarized by the I.D.E.A.L. acronym.

1. Siebold R. The concept of complete footprint restoration with guidelines for single- and double-bundle ACL reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(5):699-706.

2. Siebold R, Schuhmacher P. Restoration of the tibial ACL footprint area and geometry using the modified insertion site table. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(9):1845-1849.

3. Piefer JW, Pflugner TR, Hwang MD, Lubowitz JH. Anterior cruciate ligament femoral footprint anatomy: systematic review of the 21st century literature. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(6):872-881.

4. Wilson AJ, Yasen SK, Nancoo T, Stannard R, Smith JO, Logan JS. Anatomic all-inside anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using the translateral technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2013;2(2):e99-e104.

5. Colombet P, Robinson J, Christel P, et al. Morphology of anterior cruciate ligament attachments for anatomic reconstruction: a cadaveric dissection and radiographic study. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(9):984-992.

6. Harner CD, Baek GH, Vogrin TM, Carlin GJ, Kashiwaguchi S, Woo SL. Quantitative analysis of human cruciate ligament insertions. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(7):741-749.

7. Mochizuki T, Fujishiro H, Nimura A, et al. Anatomic and histologic analysis of the mid-substance and fan-like extension fibres of the anterior cruciate ligament during knee motion, with special reference to the femoral attachment. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(2):336-344.

8. Siebold R, Schuhmacher P, Fernandez F, et al. Flat midsubstance of the anterior cruciate ligament with tibial “C”-shaped insertion site [published correction appears in Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014 Aug 23. Epub ahead of print]. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014 May 20. [Epub ahead of print]

9. Triantafyllidi E, Paschos NK, Goussia A, et al. The shape and the thickness of the anterior cruciate ligament along its length in relation to the posterior cruciate ligament: a cadaveric study. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(12):1963-1973.

10. Arnold MP, Kooloos J, van Kampen A. Single-incision technique misses the anatomical femoral anterior cruciate ligament insertion: a cadaver study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2001;9(4):194-199.

11. Ayerza MA, Múscolo DL, Costa-Paz M, Makino A, Rondón L. Comparison of sagittal obliquity of the reconstructed anterior cruciate ligament with native anterior cruciate ligament using magnetic resonance imaging. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(3):257-261.

12. Bowers AL, Bedi A, Lipman JD, et al. Comparison of anterior cruciate ligament tunnel position and graft obliquity with transtibial and anteromedial portal femoral tunnel reaming techniques using high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(11):1511-1522.

13. Howell SM, Gittins ME, Gottlieb JE, Traina SM, Zoellner TM. The relationship between the angle of the tibial tunnel in the coronal plane and loss of flexion and anterior laxity after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(5):567-574.

14. Kopf S, Forsythe B, Wong AK, et al. Nonanatomic tunnel position in traditional transtibial single-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction evaluated by three-dimensional computed tomography. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(6):1427-1431.

15. Simmons R, Howell SM, Hull ML. Effect of the angle of the femoral and tibial tunnels in the coronal plane and incremental excision of the posterior cruciate ligament on tension of an anterior cruciate ligament graft: an in vitro study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85(6):1018-1029.

16. Stanford FC, Kendoff D, Warren RF, Pearle AD. Native anterior cruciate ligament obliquity versus anterior cruciate ligament graft obliquity: an observational study using navigated measurements. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(1):114-119.

17. Ferretti M, Ekdahl M, Shen W, Fu FH. Osseous landmarks of the femoral attachment of the anterior cruciate ligament: an anatomic study. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(11):1218-1225.

18. Hutchinson MR, Ash SA. Resident’s ridge: assessing the cortical thickness of the lateral wall and roof of the intercondylar notch. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(9):931-935.

19. Fu FH, Jordan SS. The lateral intercondylar ridge—a key to anatomic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(10):2103-2104.

20. Smigielski R, Zdanowicz U, Drwięga M, Ciszek B, Ciszkowska-Łysoń B, Siebold R. Ribbon like appearance of the midsubstance fibres of the anterior cruciate ligament close to its femoral insertion site: a cadaveric study including 111 knees. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014 Jun 28. [Epub ahead of print]

21. Iwahashi T, Shino K, Nakata K, et al. Direct anterior cruciate ligament insertion to the femur assessed by histology and 3-dimensional volume-rendered computed tomography. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(9 suppl):S13-S20.

22. Sasaki N, Ishibashi Y, Tsuda E, et al. The femoral insertion of the anterior cruciate ligament: discrepancy between macroscopic and histological observations. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(8):1135-1146.

23. Benjamin M, Moriggl B, Brenner E, Emery P, McGonagle D, Redman S. The “enthesis organ” concept: why enthesopathies may not present as focal insertional disorders. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(10):3306-3313.

24. Pathare NP, Nicholas SJ, Colbrunn R, McHugh MP. Kinematic analysis of the indirect femoral insertion of the anterior cruciate ligament: implications for anatomic femoral tunnel placement. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(11):1430-1438.

25. Artmann M, Wirth CJ. Investigation of the appropriate functional replacement of the anterior cruciate ligament (author’s transl) [in German]. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1974;112(1):160-165.

26. Amis AA, Jakob RP. Anterior cruciate ligament graft positioning, tensioning and twisting. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1998;(6 suppl 1):S2-S12.

27. Beynnon BD, Uh BS, Johnson RJ, Fleming BC, Renström PA, Nichols CE. The elongation behavior of the anterior cruciate ligament graft in vivo. A long-term follow-up study. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(2):161-166.

28. O’Meara PM, O’Brien WR, Henning CE. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction stability with continuous passive motion. The role of isometric graft placement. Clin Orthop. 1992;(277):201-209.

29. Hefzy MS, Grood ES, Noyes FR. Factors affecting the region of most isometric femoral attachments. Part II: the anterior cruciate ligament. Am J Sports Med. 1989;17(2):208-216.

30. Zavras TD, Race A, Bull AM, Amis AA. A comparative study of ‘isometric’ points for anterior cruciate ligament graft attachment. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2001;9(1):28-33.

31. Pearle AD, Shannon FJ, Granchi C, Wickiewicz TL, Warren RF. Comparison of 3-dimensional obliquity and anisometric characteristics of anterior cruciate ligament graft positions using surgical navigation. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(8):1534-1541.

32. Lubowitz JH. Anatomic ACL reconstruction produces greater graft length change during knee range-of-motion than transtibial technique. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(5):1190-1195.

33. Markolf KL, Burchfield DM, Shapiro MM, Davis BR, Finerman GA, Slauterbeck JL. Biomechanical consequences of replacement of the anterior cruciate ligament with a patellar ligament allograft. Part I: insertion of the graft and anterior-posterior testing. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(11):1720-1727.

34. Musahl V, Plakseychuk A, VanScyoc A, et al. Varying femoral tunnels between the anatomical footprint and isometric positions: effect on kinematics of the anterior cruciate ligament-reconstructed knee. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(5):712-718.

35. Bedi A, Musahl V, Steuber V, et al. Transtibial versus anteromedial portal reaming in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: an anatomic and biomechanical evaluation of surgical technique. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(3):380-390.

36. Lim HC, Yoon YC, Wang JH, Bae JH. Anatomical versus non-anatomical single bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a cadaveric study of comparison of knee stability. Clin Orthop Surg. 2012;4(4):249-255.

37. Loh JC, Fukuda Y, Tsuda E, Steadman RJ, Fu FH, Woo SL. Knee stability and graft function following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: comparison between 11 o’clock and 10 o’clock femoral tunnel placement. 2002 Richard O’Connor Award paper. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(3):297-304.

38. Cross MB, Musahl V, Bedi A, et al. Anteromedial versus central single-bundle graft position: which anatomic graft position to choose? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(7):1276-1281.

39. Markolf KL, Jackson SR, McAllister DR. A comparison of 11 o’clock versus oblique femoral tunnels in the anterior cruciate ligament–reconstructed knee: knee kinematics during a simulated pivot test. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(5):912-917.

40. Markolf KL, Park S, Jackson SR, McAllister DR. Anterior-posterior and rotatory stability of single and double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(1):107-118.

41. Markolf KL, Park S, Jackson SR, McAllister DR. Contributions of the posterolateral bundle of the anterior cruciate ligament to anterior-posterior knee laxity and ligament forces. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(7):805-809.

42. Markolf KL, Burchfield DM, Shapiro MM, Cha CW, Finerman GA, Slauterbeck JL. Biomechanical consequences of replacement of the anterior cruciate ligament with a patellar ligament allograft. Part II: forces in the graft compared with forces in the intact ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(11):1728-1734.

43. Wallace MP, Howell SM, Hull ML. In vivo tensile behavior of a four-bundle hamstring graft as a replacement for the anterior cruciate ligament. J Orthop Res. 1997;15(4):539-545.

44. Harner CD, Marks PH, Fu FH, Irrgang JJ, Silby MB, Mengato R. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: endoscopic versus two-incision technique. Arthroscopy. 1994;10(5):502-512.

45. Howell SM, Deutsch ML. Comparison of endoscopic and two-incision technique for reconstructing a torn anterior cruciate ligament using hamstring tendons. J Arthroscopy. 1999;15(6):594-606.

46. Chouliaras V, Ristanis S, Moraiti C, Stergiou N, Georgoulis AD. Effectiveness of reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament with quadrupled hamstrings and bone–patellar tendon–bone autografts: an in vivo study comparing tibial internal–external rotation. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(2):189-196.

47. Logan MC, Williams A, Lavelle J, Gedroyc W, Freeman M. Tibiofemoral kinematics following successful anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using dynamic multiple resonance imaging. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(4):984-992.

48. Papannagari R, Gill TJ, Defrate LE, Moses JM, Petruska AJ, Li G. In vivo kinematics of the knee after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a clinical and functional evaluation. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(12):2006-2012.

49. Tashman S, Collon D, Anderson K, Kolowich P, Anderst W. Abnormal rotational knee motion during running after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(4):975-983.

50. Tashman S, Kolowich P, Collon D, Anderson K, Anderst W. Dynamic function of the ACL-reconstructed knee during running. Clin Orthop. 2007;(454):66-73.

51. Wallace MP, Hull ML, Howell SM. Can an isometer predict the tensile behavior of a double-looped hamstring graft during anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction? J Orthop Res. 1998;16(3):386-393.

52. Rahr-Wagner L, Thillemann TM, Pedersen AB, Lind MC. Increased risk of revision after anteromedial compared with transtibial drilling of the femoral tunnel during primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: results from the Danish Knee Ligament Reconstruction Register. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(1):98-105.

53. van Eck CF, Schkrohowsky JG, Working ZM, Irrgang JJ, Fu FH. Prospective analysis of failure rate and predictors of failure after anatomic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with allograft. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(4):800-807.

54. Ahn JH, Choi SH, Wang JH, Yoo JC, Yim HS, Chang MJ. Outcomes and second-look arthroscopic evaluation after double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with use of a single tibial tunnel. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(20):1865-1872.

1. Siebold R. The concept of complete footprint restoration with guidelines for single- and double-bundle ACL reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(5):699-706.

2. Siebold R, Schuhmacher P. Restoration of the tibial ACL footprint area and geometry using the modified insertion site table. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(9):1845-1849.

3. Piefer JW, Pflugner TR, Hwang MD, Lubowitz JH. Anterior cruciate ligament femoral footprint anatomy: systematic review of the 21st century literature. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(6):872-881.

4. Wilson AJ, Yasen SK, Nancoo T, Stannard R, Smith JO, Logan JS. Anatomic all-inside anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using the translateral technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2013;2(2):e99-e104.

5. Colombet P, Robinson J, Christel P, et al. Morphology of anterior cruciate ligament attachments for anatomic reconstruction: a cadaveric dissection and radiographic study. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(9):984-992.

6. Harner CD, Baek GH, Vogrin TM, Carlin GJ, Kashiwaguchi S, Woo SL. Quantitative analysis of human cruciate ligament insertions. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(7):741-749.

7. Mochizuki T, Fujishiro H, Nimura A, et al. Anatomic and histologic analysis of the mid-substance and fan-like extension fibres of the anterior cruciate ligament during knee motion, with special reference to the femoral attachment. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(2):336-344.

8. Siebold R, Schuhmacher P, Fernandez F, et al. Flat midsubstance of the anterior cruciate ligament with tibial “C”-shaped insertion site [published correction appears in Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014 Aug 23. Epub ahead of print]. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014 May 20. [Epub ahead of print]

9. Triantafyllidi E, Paschos NK, Goussia A, et al. The shape and the thickness of the anterior cruciate ligament along its length in relation to the posterior cruciate ligament: a cadaveric study. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(12):1963-1973.

10. Arnold MP, Kooloos J, van Kampen A. Single-incision technique misses the anatomical femoral anterior cruciate ligament insertion: a cadaver study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2001;9(4):194-199.

11. Ayerza MA, Múscolo DL, Costa-Paz M, Makino A, Rondón L. Comparison of sagittal obliquity of the reconstructed anterior cruciate ligament with native anterior cruciate ligament using magnetic resonance imaging. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(3):257-261.

12. Bowers AL, Bedi A, Lipman JD, et al. Comparison of anterior cruciate ligament tunnel position and graft obliquity with transtibial and anteromedial portal femoral tunnel reaming techniques using high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(11):1511-1522.

13. Howell SM, Gittins ME, Gottlieb JE, Traina SM, Zoellner TM. The relationship between the angle of the tibial tunnel in the coronal plane and loss of flexion and anterior laxity after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(5):567-574.

14. Kopf S, Forsythe B, Wong AK, et al. Nonanatomic tunnel position in traditional transtibial single-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction evaluated by three-dimensional computed tomography. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(6):1427-1431.