User login

Following the path of leadership

VA Hospitalist Dr. Matthew Tuck

For Matthew Tuck, MD, MEd, FACP, associate section chief for hospital medicine at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in Washington, leadership is something that hospitalists can and should be learning at every opportunity.

Some of the best insights about effective leadership, teamwork, and process improvement come from the business world and have been slower to infiltrate into hospital settings and hospitalist groups, he says. But Dr. Tuck has tried to take advantage of numerous opportunities for leadership development in his own career.

He has been a hospitalist since 2010 and is part of a group of 13 physicians, all of whom carry clinical, teaching, and research responsibilities while pursuing a variety of education, quality improvement, and performance improvement topics.

“My chair has been generous about giving me time to do teaching and research and to pursue opportunities for career development,” he said. The Washington VAMC works with four affiliate medical schools in the area, and its six daily hospital medicine services are all 100% teaching services with assigned residents and interns.

Dr. Tuck divides his professional time roughly one-third each between clinical – seeing patients 5 months a year on a consultative or inpatient basis with resident teams; administrative in a variety of roles; and research. He has academic appointments at the George Washington University (GWU) School of Medicine and at the Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md. He developed the coursework for teaching evidence-based medicine to first- and second-year medical students at GWU.

He is also part of a large research consortium with five sites and $7.5 million in funding over 5 years from NIH’s National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities to study how genetic information from African American patients can predict their response to cardiovascular medications. He serves as the study’s site Principal Investigator at the VAMC.

Opportunities to advance his leadership skills have included the VA’s Aspiring Leaders Program and Leadership Development Mentoring Program, which teach leadership skills on topical subjects such as teaching, communications skills, and finance. The Master Teacher Leadership Development Program for medical faculty at GWU, where he attended medical school and did his internship and residency, offers six intensive, classroom-based 8-week courses over a 1-year period. They cover various topical subjects with faculty from the business world teaching principles of leadership. The program includes a mentoring action plan for participants and leads to a graduate certificate in leadership development from GWU’s Graduate School of Education and Human Development at the end of the year’s studies.

Dr. Tuck credits completing this kind of coursework for his current position of leadership in the VA and he tries to share what he has learned with the medical students he teaches.

“When I was starting out as a physician, I never received training in how to lead a team. I found myself trying to get everything done for my patients while teaching my learners, and I really struggled for the first couple of years to manage these competing demands on my time,” he said.

Now, on the first day of a new clinical rotation, he meets one-on-one with his residents to set out goals and expectations. “I say: ‘This is how I want rounds to be run. What are your expectations?’ That way we make sure we’re collaborating as a team. I don’t know that medical school prepares you for this kind of teamwork. Unless you bring a background in business, you can really struggle.”

Interest in hospital medicine

“Throughout our medical training we do a variety of rotations and clerkships. I found myself falling in love with all of them – surgery, psychiatry, obstetrics, and gynecology,” Dr. Tuck explained, as he reflected on how he ended up in hospital medicine. “As someone who was interested in all of these different fields of medicine, I considered myself a true medical generalist. And in hospitalized patients, who struggle with all of the different issues that bring them to the hospital, I saw a compilation of all my experiences in residency training combined in one setting.”

Hospital medicine was a relatively young field at that time, with few academic hospitalists, he said. “But I had good mentors who encouraged me to pursue my educational, research, and administrative interests. My affinity for the VA was also largely due to my training. We worked in multiple settings – academic, community-based, National Institutes of Health, and at the VA.”

Dr. Tuck said that, of all the settings in which he practiced, he felt the VA truly trained him best to be a doctor. “The experience made me feel like a holistic practitioner,” he said. “The system allowed me to take the best care of my patients, since I didn’t have to worry about whether I could make needed referrals to specialists. Very early in my internship year we were seeing very sick patients with multiple comorbidities, but it was easy to get a social worker or case manager involved, compared to other settings, which can be more difficult to navigate.”

While the VA is a “great health system,” Dr. Tuck said, the challenge is learning how to work with its bureaucracy. “If you don’t know how the system works, it can seem to get in your way.” But overall, he said, the VA functions well and compares favorably with private sector hospitals and health systems. That was also the conclusion of a recent study in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, which compared the quality of outpatient and inpatient care in VA and non-VA settings using recent performance measure data.1 The authors concluded that the VA system performed similarly or better than non-VA health care on most nationally recognized measures of inpatient and outpatient care quality, although there is wide variation between VA facilities.

Working with the team

Another major interest for Dr. Tuck is team-based learning, which also grew out of his GWU leadership certificate course work on teaching teams and team development. He is working on a draft paper for publication with coauthor Patrick Rendon, MD, associate program director for the University of New Mexico’s internal medicine residency program, building on the group development stage theory – “Forming/Storming/Norming/Performing” – developed by Tuckman and Jenson.2

The theory offers 12 tips for optimizing inpatient ward team performance, such as getting the learners to buy in at an early stage of a project. “Everyone I talk to about our research is eager to learn how to apply these principles. I don’t think we’re unique at this center. We’re constantly rotating learners through the program. If you apply these principles, you can get learners to be more efficient starting from the first day,” he said.

The current inpatient team model at the Washington VAMC involves a broadly representative team from nursing, case management, social work, the business office, medical coding, utilization management, and administration that convenes every morning to discuss patient navigation and difficult discharges. “Everyone sits around a big table, and the six hospital medicine teams rotate through every fifteen minutes to review their patients’ admitting diagnoses, barriers to discharge and plans of care.”

At the patient’s bedside, a Focused Interdisciplinary Team (FIT) model, which Dr. Tuck helped to implement, incorporates a four-step process with clearly defined roles for the attending, nurse, pharmacist, and case manager or social worker. “Since implementation, our data show overall reductions in lengths of stay,” he said.

Dr. Tuck urges other hospitalists to pursue opportunities available to them to develop their leadership skills. “Look to your professional societies such as the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) or SHM.” For example, SGIM’s Academic Hospitalist Commission, which he cochairs, provides a voice on the national stage for academic hospitalists and cosponsors with SHM an annual Academic Hospitalist Academy to support career development for junior academic hospitalists as educational leaders. Since 2016, its Distinguished Professor of Hospital Medicine recognizes a professor of hospital medicine to give a plenary address at the SGIM national meeting.

SGIM’s SCHOLAR Project, a subgroup of its Academic Hospitalist Commission, has worked to identify features of successful academic hospitalist programs, with the results published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.3

“We learned that what sets successful programs apart is their leadership – as well as protected time for scholarly pursuits,” he said. “We’re all leaders in this field, whether we view ourselves that way or not.”

References

1. Price RA et al. Comparing quality of care in Veterans Affairs and Non–Veterans Affairs settings. J Gen Intern Med. 2018 Oct;33(10):1631-38.

2. Tuckman B, Jensen M. Stages of small group development revisited. Group and Organizational Studies. 1977;2:419-427.

3. Seymann GB et al. Features of successful academic hospitalist programs: Insights from the SCHOLAR (Successful hospitalists in academics and research) project. J Hosp Med. 2016 Oct;11(10):708-13.

VA Hospitalist Dr. Matthew Tuck

VA Hospitalist Dr. Matthew Tuck

For Matthew Tuck, MD, MEd, FACP, associate section chief for hospital medicine at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in Washington, leadership is something that hospitalists can and should be learning at every opportunity.

Some of the best insights about effective leadership, teamwork, and process improvement come from the business world and have been slower to infiltrate into hospital settings and hospitalist groups, he says. But Dr. Tuck has tried to take advantage of numerous opportunities for leadership development in his own career.

He has been a hospitalist since 2010 and is part of a group of 13 physicians, all of whom carry clinical, teaching, and research responsibilities while pursuing a variety of education, quality improvement, and performance improvement topics.

“My chair has been generous about giving me time to do teaching and research and to pursue opportunities for career development,” he said. The Washington VAMC works with four affiliate medical schools in the area, and its six daily hospital medicine services are all 100% teaching services with assigned residents and interns.

Dr. Tuck divides his professional time roughly one-third each between clinical – seeing patients 5 months a year on a consultative or inpatient basis with resident teams; administrative in a variety of roles; and research. He has academic appointments at the George Washington University (GWU) School of Medicine and at the Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md. He developed the coursework for teaching evidence-based medicine to first- and second-year medical students at GWU.

He is also part of a large research consortium with five sites and $7.5 million in funding over 5 years from NIH’s National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities to study how genetic information from African American patients can predict their response to cardiovascular medications. He serves as the study’s site Principal Investigator at the VAMC.

Opportunities to advance his leadership skills have included the VA’s Aspiring Leaders Program and Leadership Development Mentoring Program, which teach leadership skills on topical subjects such as teaching, communications skills, and finance. The Master Teacher Leadership Development Program for medical faculty at GWU, where he attended medical school and did his internship and residency, offers six intensive, classroom-based 8-week courses over a 1-year period. They cover various topical subjects with faculty from the business world teaching principles of leadership. The program includes a mentoring action plan for participants and leads to a graduate certificate in leadership development from GWU’s Graduate School of Education and Human Development at the end of the year’s studies.

Dr. Tuck credits completing this kind of coursework for his current position of leadership in the VA and he tries to share what he has learned with the medical students he teaches.

“When I was starting out as a physician, I never received training in how to lead a team. I found myself trying to get everything done for my patients while teaching my learners, and I really struggled for the first couple of years to manage these competing demands on my time,” he said.

Now, on the first day of a new clinical rotation, he meets one-on-one with his residents to set out goals and expectations. “I say: ‘This is how I want rounds to be run. What are your expectations?’ That way we make sure we’re collaborating as a team. I don’t know that medical school prepares you for this kind of teamwork. Unless you bring a background in business, you can really struggle.”

Interest in hospital medicine

“Throughout our medical training we do a variety of rotations and clerkships. I found myself falling in love with all of them – surgery, psychiatry, obstetrics, and gynecology,” Dr. Tuck explained, as he reflected on how he ended up in hospital medicine. “As someone who was interested in all of these different fields of medicine, I considered myself a true medical generalist. And in hospitalized patients, who struggle with all of the different issues that bring them to the hospital, I saw a compilation of all my experiences in residency training combined in one setting.”

Hospital medicine was a relatively young field at that time, with few academic hospitalists, he said. “But I had good mentors who encouraged me to pursue my educational, research, and administrative interests. My affinity for the VA was also largely due to my training. We worked in multiple settings – academic, community-based, National Institutes of Health, and at the VA.”

Dr. Tuck said that, of all the settings in which he practiced, he felt the VA truly trained him best to be a doctor. “The experience made me feel like a holistic practitioner,” he said. “The system allowed me to take the best care of my patients, since I didn’t have to worry about whether I could make needed referrals to specialists. Very early in my internship year we were seeing very sick patients with multiple comorbidities, but it was easy to get a social worker or case manager involved, compared to other settings, which can be more difficult to navigate.”

While the VA is a “great health system,” Dr. Tuck said, the challenge is learning how to work with its bureaucracy. “If you don’t know how the system works, it can seem to get in your way.” But overall, he said, the VA functions well and compares favorably with private sector hospitals and health systems. That was also the conclusion of a recent study in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, which compared the quality of outpatient and inpatient care in VA and non-VA settings using recent performance measure data.1 The authors concluded that the VA system performed similarly or better than non-VA health care on most nationally recognized measures of inpatient and outpatient care quality, although there is wide variation between VA facilities.

Working with the team

Another major interest for Dr. Tuck is team-based learning, which also grew out of his GWU leadership certificate course work on teaching teams and team development. He is working on a draft paper for publication with coauthor Patrick Rendon, MD, associate program director for the University of New Mexico’s internal medicine residency program, building on the group development stage theory – “Forming/Storming/Norming/Performing” – developed by Tuckman and Jenson.2

The theory offers 12 tips for optimizing inpatient ward team performance, such as getting the learners to buy in at an early stage of a project. “Everyone I talk to about our research is eager to learn how to apply these principles. I don’t think we’re unique at this center. We’re constantly rotating learners through the program. If you apply these principles, you can get learners to be more efficient starting from the first day,” he said.

The current inpatient team model at the Washington VAMC involves a broadly representative team from nursing, case management, social work, the business office, medical coding, utilization management, and administration that convenes every morning to discuss patient navigation and difficult discharges. “Everyone sits around a big table, and the six hospital medicine teams rotate through every fifteen minutes to review their patients’ admitting diagnoses, barriers to discharge and plans of care.”

At the patient’s bedside, a Focused Interdisciplinary Team (FIT) model, which Dr. Tuck helped to implement, incorporates a four-step process with clearly defined roles for the attending, nurse, pharmacist, and case manager or social worker. “Since implementation, our data show overall reductions in lengths of stay,” he said.

Dr. Tuck urges other hospitalists to pursue opportunities available to them to develop their leadership skills. “Look to your professional societies such as the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) or SHM.” For example, SGIM’s Academic Hospitalist Commission, which he cochairs, provides a voice on the national stage for academic hospitalists and cosponsors with SHM an annual Academic Hospitalist Academy to support career development for junior academic hospitalists as educational leaders. Since 2016, its Distinguished Professor of Hospital Medicine recognizes a professor of hospital medicine to give a plenary address at the SGIM national meeting.

SGIM’s SCHOLAR Project, a subgroup of its Academic Hospitalist Commission, has worked to identify features of successful academic hospitalist programs, with the results published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.3

“We learned that what sets successful programs apart is their leadership – as well as protected time for scholarly pursuits,” he said. “We’re all leaders in this field, whether we view ourselves that way or not.”

References

1. Price RA et al. Comparing quality of care in Veterans Affairs and Non–Veterans Affairs settings. J Gen Intern Med. 2018 Oct;33(10):1631-38.

2. Tuckman B, Jensen M. Stages of small group development revisited. Group and Organizational Studies. 1977;2:419-427.

3. Seymann GB et al. Features of successful academic hospitalist programs: Insights from the SCHOLAR (Successful hospitalists in academics and research) project. J Hosp Med. 2016 Oct;11(10):708-13.

For Matthew Tuck, MD, MEd, FACP, associate section chief for hospital medicine at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) in Washington, leadership is something that hospitalists can and should be learning at every opportunity.

Some of the best insights about effective leadership, teamwork, and process improvement come from the business world and have been slower to infiltrate into hospital settings and hospitalist groups, he says. But Dr. Tuck has tried to take advantage of numerous opportunities for leadership development in his own career.

He has been a hospitalist since 2010 and is part of a group of 13 physicians, all of whom carry clinical, teaching, and research responsibilities while pursuing a variety of education, quality improvement, and performance improvement topics.

“My chair has been generous about giving me time to do teaching and research and to pursue opportunities for career development,” he said. The Washington VAMC works with four affiliate medical schools in the area, and its six daily hospital medicine services are all 100% teaching services with assigned residents and interns.

Dr. Tuck divides his professional time roughly one-third each between clinical – seeing patients 5 months a year on a consultative or inpatient basis with resident teams; administrative in a variety of roles; and research. He has academic appointments at the George Washington University (GWU) School of Medicine and at the Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md. He developed the coursework for teaching evidence-based medicine to first- and second-year medical students at GWU.

He is also part of a large research consortium with five sites and $7.5 million in funding over 5 years from NIH’s National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities to study how genetic information from African American patients can predict their response to cardiovascular medications. He serves as the study’s site Principal Investigator at the VAMC.

Opportunities to advance his leadership skills have included the VA’s Aspiring Leaders Program and Leadership Development Mentoring Program, which teach leadership skills on topical subjects such as teaching, communications skills, and finance. The Master Teacher Leadership Development Program for medical faculty at GWU, where he attended medical school and did his internship and residency, offers six intensive, classroom-based 8-week courses over a 1-year period. They cover various topical subjects with faculty from the business world teaching principles of leadership. The program includes a mentoring action plan for participants and leads to a graduate certificate in leadership development from GWU’s Graduate School of Education and Human Development at the end of the year’s studies.

Dr. Tuck credits completing this kind of coursework for his current position of leadership in the VA and he tries to share what he has learned with the medical students he teaches.

“When I was starting out as a physician, I never received training in how to lead a team. I found myself trying to get everything done for my patients while teaching my learners, and I really struggled for the first couple of years to manage these competing demands on my time,” he said.

Now, on the first day of a new clinical rotation, he meets one-on-one with his residents to set out goals and expectations. “I say: ‘This is how I want rounds to be run. What are your expectations?’ That way we make sure we’re collaborating as a team. I don’t know that medical school prepares you for this kind of teamwork. Unless you bring a background in business, you can really struggle.”

Interest in hospital medicine

“Throughout our medical training we do a variety of rotations and clerkships. I found myself falling in love with all of them – surgery, psychiatry, obstetrics, and gynecology,” Dr. Tuck explained, as he reflected on how he ended up in hospital medicine. “As someone who was interested in all of these different fields of medicine, I considered myself a true medical generalist. And in hospitalized patients, who struggle with all of the different issues that bring them to the hospital, I saw a compilation of all my experiences in residency training combined in one setting.”

Hospital medicine was a relatively young field at that time, with few academic hospitalists, he said. “But I had good mentors who encouraged me to pursue my educational, research, and administrative interests. My affinity for the VA was also largely due to my training. We worked in multiple settings – academic, community-based, National Institutes of Health, and at the VA.”

Dr. Tuck said that, of all the settings in which he practiced, he felt the VA truly trained him best to be a doctor. “The experience made me feel like a holistic practitioner,” he said. “The system allowed me to take the best care of my patients, since I didn’t have to worry about whether I could make needed referrals to specialists. Very early in my internship year we were seeing very sick patients with multiple comorbidities, but it was easy to get a social worker or case manager involved, compared to other settings, which can be more difficult to navigate.”

While the VA is a “great health system,” Dr. Tuck said, the challenge is learning how to work with its bureaucracy. “If you don’t know how the system works, it can seem to get in your way.” But overall, he said, the VA functions well and compares favorably with private sector hospitals and health systems. That was also the conclusion of a recent study in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, which compared the quality of outpatient and inpatient care in VA and non-VA settings using recent performance measure data.1 The authors concluded that the VA system performed similarly or better than non-VA health care on most nationally recognized measures of inpatient and outpatient care quality, although there is wide variation between VA facilities.

Working with the team

Another major interest for Dr. Tuck is team-based learning, which also grew out of his GWU leadership certificate course work on teaching teams and team development. He is working on a draft paper for publication with coauthor Patrick Rendon, MD, associate program director for the University of New Mexico’s internal medicine residency program, building on the group development stage theory – “Forming/Storming/Norming/Performing” – developed by Tuckman and Jenson.2

The theory offers 12 tips for optimizing inpatient ward team performance, such as getting the learners to buy in at an early stage of a project. “Everyone I talk to about our research is eager to learn how to apply these principles. I don’t think we’re unique at this center. We’re constantly rotating learners through the program. If you apply these principles, you can get learners to be more efficient starting from the first day,” he said.

The current inpatient team model at the Washington VAMC involves a broadly representative team from nursing, case management, social work, the business office, medical coding, utilization management, and administration that convenes every morning to discuss patient navigation and difficult discharges. “Everyone sits around a big table, and the six hospital medicine teams rotate through every fifteen minutes to review their patients’ admitting diagnoses, barriers to discharge and plans of care.”

At the patient’s bedside, a Focused Interdisciplinary Team (FIT) model, which Dr. Tuck helped to implement, incorporates a four-step process with clearly defined roles for the attending, nurse, pharmacist, and case manager or social worker. “Since implementation, our data show overall reductions in lengths of stay,” he said.

Dr. Tuck urges other hospitalists to pursue opportunities available to them to develop their leadership skills. “Look to your professional societies such as the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) or SHM.” For example, SGIM’s Academic Hospitalist Commission, which he cochairs, provides a voice on the national stage for academic hospitalists and cosponsors with SHM an annual Academic Hospitalist Academy to support career development for junior academic hospitalists as educational leaders. Since 2016, its Distinguished Professor of Hospital Medicine recognizes a professor of hospital medicine to give a plenary address at the SGIM national meeting.

SGIM’s SCHOLAR Project, a subgroup of its Academic Hospitalist Commission, has worked to identify features of successful academic hospitalist programs, with the results published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.3

“We learned that what sets successful programs apart is their leadership – as well as protected time for scholarly pursuits,” he said. “We’re all leaders in this field, whether we view ourselves that way or not.”

References

1. Price RA et al. Comparing quality of care in Veterans Affairs and Non–Veterans Affairs settings. J Gen Intern Med. 2018 Oct;33(10):1631-38.

2. Tuckman B, Jensen M. Stages of small group development revisited. Group and Organizational Studies. 1977;2:419-427.

3. Seymann GB et al. Features of successful academic hospitalist programs: Insights from the SCHOLAR (Successful hospitalists in academics and research) project. J Hosp Med. 2016 Oct;11(10):708-13.

Culture: An unseen force in the hospital workplace

Parallels from the airline industry

“Workplace culture” has a profound influence on the success or failure of a team in the modern-day work environment, where teamwork and interpersonal interactions have paramount importance. Crew resource management (CRM), a technique developed originally by the airline industry, has been used as a tool to improve safety and quality in ICUs, trauma rooms, and operating rooms.1,2 This article discusses the use of CRM in hospital medicine as a tool for training and maintaining a favorable workplace culture.

Origin and evolution of CRM

United Airlines instituted the airline industry’s first crew resource management for pilots in 1981, following the 1978 crash of United Flight 173 in Portland, Ore. CRM was created based on recommendations from the National Transportation Safety Board and from a NASA workshop held subsequently.3 CRM has since evolved through five generations, and is a required annual training for most major commercial airline companies around the world. It also has been adapted for personnel training by several modern international industries.4

From the airline industry to the hospital

The health care industry is similar to the airline industry in that there is absolutely no margin of error, and that workplace culture plays a very important role. The culture being referred to here is the sum total of values, beliefs, work ethics, work strategies, strengths, and weaknesses of a group of people, and how they interact as a group. In other words, it is the dynamics of a group.

According to Donelson R. Forsyth, a social and personality psychologist at the University of Richmond (Virginia), the two key determinants of successful teamwork are a “shared mental representation of the task,” which refers to an in-depth understanding of the team and the tasks they are attempting; and “group unity/cohesion,” which means that, generally, members of cohesive groups like each other and the group, and they also are united in their pursuit of collective, group-level goals.5

Understanding the culture of a hospitalist team

Analyzing group dynamics and actively managing them toward both the institutional and global goals of health care is critical for the success of an organization. This is the core of successfully managing any team in any industry.

Additionally, the rapidly changing health care climate and insurance payment systems requires hospital medicine groups to rapidly adapt to the constantly changing health care business environment. As a result, there are a couple of ways to evaluate the effectiveness of the team:

- Measure tangible outcomes. The outcomes have to be well defined, important and measurable. These could be cost of care, quality of care, engagement of the team etc. These tangible measures’ outcome over a period of time can be used as a measure of how effective the team is.

- Simply ask your team! It is very important to know what core values the team holds dear. The best way to get that information from the team is to find out the de facto leaders of the team. They should be involved in the decision-making process, thus making them valuable to the management as well as the team.

Culture shapes outcomes

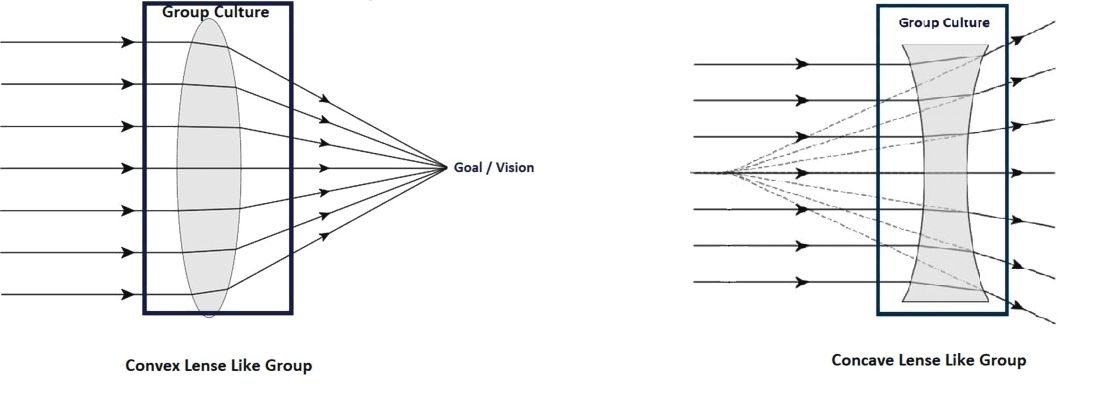

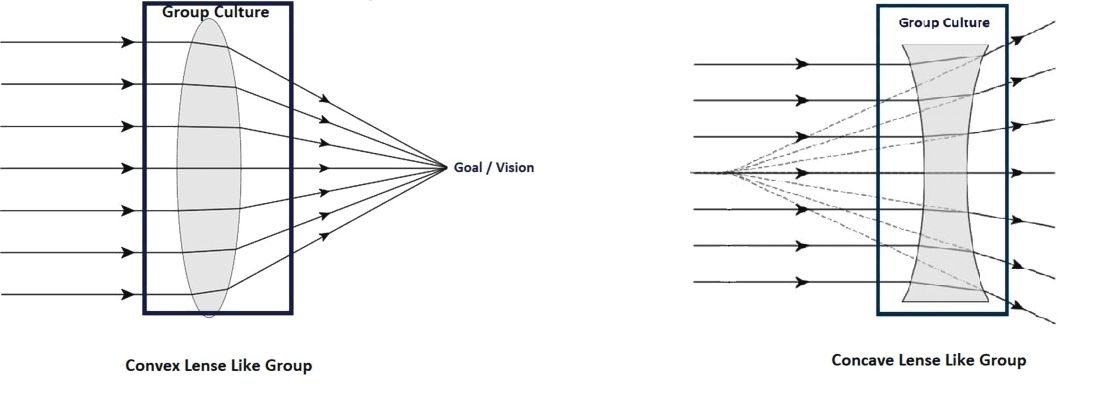

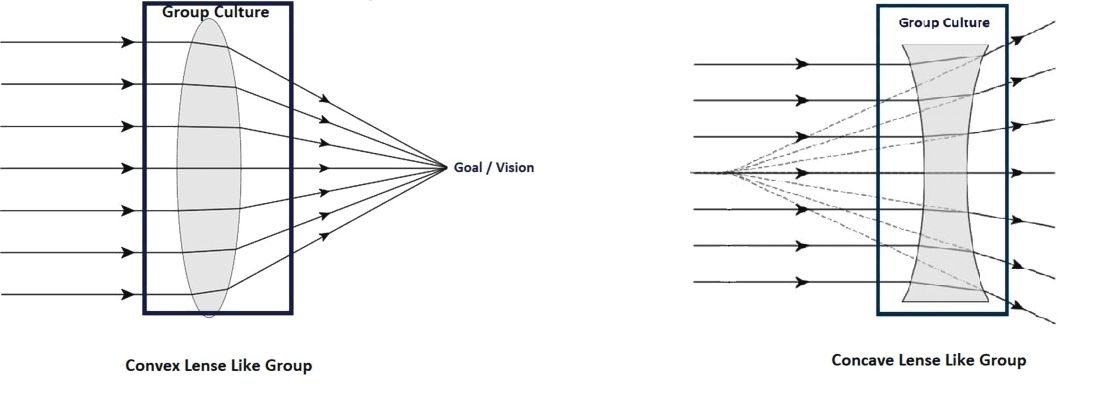

We have used the analogy of a convex and concave lens to help understand this better. A well-developed and well-coordinated team is like convex lens. A lens’ ability to converge or diverge light rays depends on certain characteristics like the curvature of surfaces and refractory index. Likewise, the culture of a group determines its ability to transform all the demands of the collective workload toward a unified goal/outcome. If it is favorable, the group will work as one and success will happen automatically.

Unfortunately, the opposite of this, (the concave lens effect), is more commonplace, where the dynamics of a team prevent the goals being achieved, as there is discordance, poor coordination of ideas and values, and team members not liking each other.

Most teams would fall somewhere within this spectrum, spanning the most favorable convex lens–like group to the least favorable concave lens–like group.

Change team dynamics using CRM principles

The concept of using CRM principles in health care is not entirely new. Such agencies as the Joint Commission and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality recommend using principles of CRM to improve communications, and as an error-prevention tool in health care.6

This approach can be broken down into four important steps:

1. Recruit right. It is important to make sure that the new recruit is the right fit for the team and that the de facto leaders and a few other team members are involved in interviewing the candidates. Their assessment should be given due consideration in making the decision to give the new recruit the job.

Every program looks for aspects like clinical competence, interpersonal communication, teamwork, etc., in a candidate, but it is even more important to make sure the candidate has the tenets that would make him/her a part of that particular team.

2. Train well. The newly recruited providers should be given focused training and the seasoned providers should be given refresher training at regular intervals. Care should be taken in designing the training programs in such a way that the providers are trained in skills that they don’t always think about, things that aren’t readily obvious, and in skills that they never get trained in during medical school and residency.

Specifically, they should be trained in:

- Values. These should include the values of both the organization and the team.

- Safety. This should include all the safety protocols that are in place in the organization - where to get help, how to report unsafe events etc.

- Communication.

Within the group: Have a mentor for the new provider, and also develop a culture where he/she feels comfortable to reach out to anyone in the team for help.

With patients and families: This training should ideally be done in a simulated environment if possible.

With other groups in the hospital: Consultants, nurses, other ancillary staff. Give them an idea about the prevailing culture in the organization with regard to these groups, so that they know what to expect when dealing with them.

- Managing perceptions. How the providers are viewed in the hospital, and how to improve it or maintain it.

- Nurturing the good. Use positive reinforcements to solidify the positive aspects of group dynamics these individuals might possess.

- Weeding out the bad. Use training and feedback to alter the negative group dynamic aspects.

3. Intervene. This is necessary either to maintain the positive aspects of a team that is already high-functioning, or to transform a poorly functioning team into a well-coordinated team. This is where the principles of CRM are going to be most useful.

There are five generations of CRM, each with a different focus.6 Only the aspects relevant to hospital medicine training are mentioned here.

- Communication. Address the gaps in communication. It is important to include people who are trusted by the team in designing and executing these sessions.

- Leadership. The goal should be to encourage the team to take ownership of the program. This will make a tremendous change in the ability of a team to deliver and rise up to challenges. The organizational leadership has to be willing to elevate the leaders of the group to positions where they can meaningfully take part in managing the team and making decisions that are critical to the team.

- Burnout management. Providers getting disillusioned: having no work-life balance; not getting enough respect from management, as well as other groups of doctors/nurses/etc. in the hospital; they are subject to bad scheduling and poor pay – all of which can all lead to career-ending burnout. It is important to recognize this and mitigate the factors that cause burnout.

- Organizational culture. If the team feels valued and supported, they will, in turn, work hard toward success. Creative leadership and a willingness to accommodate what matters the most to the team is essential for achieving this.

- Simulated training. These can be done in simulation labs, or in-group sessions with the team, re-creating difficult scenarios or problems in which the whole team can come together and solve them.

- Error containment and management. The team needs to identify possible sources of error and contain them before errors happen. The group should get together if a serious event happens and brainstorm why it happened and take measures to prevent it.

4. Reevaluate. Team dynamics tend to change over time. It is important to constantly re-evaluate the team and make sure that the team’s culture remains favorable. There should be recurrent cycles of retraining and interventions to maintain the positive growth that has been attained, as depicted in the schematic below:

Conclusion

CRM is widely accepted as an effective tool in training individuals in many high performing industries. This article describes a framework in which the principles of CRM can be applied to hospital medicine to maintain positive work culture.

Dr. Prabhakaran is director of hospital medicine transitions of care, Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Mass., and assistant professor of medicine, University of Massachusetts, Worcester. Dr. Medarametla is medical director, hospital medicine, Baystate Medical Center, and assistant professor of medicine, University of Massachusetts.

References

1. Haerkens MH et al. Crew Resource Management in the ICU: The need for culture change. Ann Intensive Care. 2012 Aug 22;2:39.

2. Haerkens MH et al. Crew Resource Management in the trauma room: A prospective 3-year cohort study. Eur J Emerg Med. 2018 Aug;25(4):281-7.

3. Malcolm Gladwell. The ethnic theory of plane crashes. Outliers: The Story of Success. (Boston: Little, Brown and Company; 2008:177-223).

4. Helmreich RL et al. The evolution of Crew Resource Management training in commercial aviation. Int J Aviat Psychol. 1999;9(1):19-32.

5. Forsyth DR. The psychology of groups. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, Ill: DEF publishers; 2017.

6. Crew Resource Management. Available at Aviation Knowledge. Accessed Dec. 20, 2017.

Parallels from the airline industry

Parallels from the airline industry

“Workplace culture” has a profound influence on the success or failure of a team in the modern-day work environment, where teamwork and interpersonal interactions have paramount importance. Crew resource management (CRM), a technique developed originally by the airline industry, has been used as a tool to improve safety and quality in ICUs, trauma rooms, and operating rooms.1,2 This article discusses the use of CRM in hospital medicine as a tool for training and maintaining a favorable workplace culture.

Origin and evolution of CRM

United Airlines instituted the airline industry’s first crew resource management for pilots in 1981, following the 1978 crash of United Flight 173 in Portland, Ore. CRM was created based on recommendations from the National Transportation Safety Board and from a NASA workshop held subsequently.3 CRM has since evolved through five generations, and is a required annual training for most major commercial airline companies around the world. It also has been adapted for personnel training by several modern international industries.4

From the airline industry to the hospital

The health care industry is similar to the airline industry in that there is absolutely no margin of error, and that workplace culture plays a very important role. The culture being referred to here is the sum total of values, beliefs, work ethics, work strategies, strengths, and weaknesses of a group of people, and how they interact as a group. In other words, it is the dynamics of a group.

According to Donelson R. Forsyth, a social and personality psychologist at the University of Richmond (Virginia), the two key determinants of successful teamwork are a “shared mental representation of the task,” which refers to an in-depth understanding of the team and the tasks they are attempting; and “group unity/cohesion,” which means that, generally, members of cohesive groups like each other and the group, and they also are united in their pursuit of collective, group-level goals.5

Understanding the culture of a hospitalist team

Analyzing group dynamics and actively managing them toward both the institutional and global goals of health care is critical for the success of an organization. This is the core of successfully managing any team in any industry.

Additionally, the rapidly changing health care climate and insurance payment systems requires hospital medicine groups to rapidly adapt to the constantly changing health care business environment. As a result, there are a couple of ways to evaluate the effectiveness of the team:

- Measure tangible outcomes. The outcomes have to be well defined, important and measurable. These could be cost of care, quality of care, engagement of the team etc. These tangible measures’ outcome over a period of time can be used as a measure of how effective the team is.

- Simply ask your team! It is very important to know what core values the team holds dear. The best way to get that information from the team is to find out the de facto leaders of the team. They should be involved in the decision-making process, thus making them valuable to the management as well as the team.

Culture shapes outcomes

We have used the analogy of a convex and concave lens to help understand this better. A well-developed and well-coordinated team is like convex lens. A lens’ ability to converge or diverge light rays depends on certain characteristics like the curvature of surfaces and refractory index. Likewise, the culture of a group determines its ability to transform all the demands of the collective workload toward a unified goal/outcome. If it is favorable, the group will work as one and success will happen automatically.

Unfortunately, the opposite of this, (the concave lens effect), is more commonplace, where the dynamics of a team prevent the goals being achieved, as there is discordance, poor coordination of ideas and values, and team members not liking each other.

Most teams would fall somewhere within this spectrum, spanning the most favorable convex lens–like group to the least favorable concave lens–like group.

Change team dynamics using CRM principles

The concept of using CRM principles in health care is not entirely new. Such agencies as the Joint Commission and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality recommend using principles of CRM to improve communications, and as an error-prevention tool in health care.6

This approach can be broken down into four important steps:

1. Recruit right. It is important to make sure that the new recruit is the right fit for the team and that the de facto leaders and a few other team members are involved in interviewing the candidates. Their assessment should be given due consideration in making the decision to give the new recruit the job.

Every program looks for aspects like clinical competence, interpersonal communication, teamwork, etc., in a candidate, but it is even more important to make sure the candidate has the tenets that would make him/her a part of that particular team.

2. Train well. The newly recruited providers should be given focused training and the seasoned providers should be given refresher training at regular intervals. Care should be taken in designing the training programs in such a way that the providers are trained in skills that they don’t always think about, things that aren’t readily obvious, and in skills that they never get trained in during medical school and residency.

Specifically, they should be trained in:

- Values. These should include the values of both the organization and the team.

- Safety. This should include all the safety protocols that are in place in the organization - where to get help, how to report unsafe events etc.

- Communication.

Within the group: Have a mentor for the new provider, and also develop a culture where he/she feels comfortable to reach out to anyone in the team for help.

With patients and families: This training should ideally be done in a simulated environment if possible.

With other groups in the hospital: Consultants, nurses, other ancillary staff. Give them an idea about the prevailing culture in the organization with regard to these groups, so that they know what to expect when dealing with them.

- Managing perceptions. How the providers are viewed in the hospital, and how to improve it or maintain it.

- Nurturing the good. Use positive reinforcements to solidify the positive aspects of group dynamics these individuals might possess.

- Weeding out the bad. Use training and feedback to alter the negative group dynamic aspects.

3. Intervene. This is necessary either to maintain the positive aspects of a team that is already high-functioning, or to transform a poorly functioning team into a well-coordinated team. This is where the principles of CRM are going to be most useful.

There are five generations of CRM, each with a different focus.6 Only the aspects relevant to hospital medicine training are mentioned here.

- Communication. Address the gaps in communication. It is important to include people who are trusted by the team in designing and executing these sessions.

- Leadership. The goal should be to encourage the team to take ownership of the program. This will make a tremendous change in the ability of a team to deliver and rise up to challenges. The organizational leadership has to be willing to elevate the leaders of the group to positions where they can meaningfully take part in managing the team and making decisions that are critical to the team.

- Burnout management. Providers getting disillusioned: having no work-life balance; not getting enough respect from management, as well as other groups of doctors/nurses/etc. in the hospital; they are subject to bad scheduling and poor pay – all of which can all lead to career-ending burnout. It is important to recognize this and mitigate the factors that cause burnout.

- Organizational culture. If the team feels valued and supported, they will, in turn, work hard toward success. Creative leadership and a willingness to accommodate what matters the most to the team is essential for achieving this.

- Simulated training. These can be done in simulation labs, or in-group sessions with the team, re-creating difficult scenarios or problems in which the whole team can come together and solve them.

- Error containment and management. The team needs to identify possible sources of error and contain them before errors happen. The group should get together if a serious event happens and brainstorm why it happened and take measures to prevent it.

4. Reevaluate. Team dynamics tend to change over time. It is important to constantly re-evaluate the team and make sure that the team’s culture remains favorable. There should be recurrent cycles of retraining and interventions to maintain the positive growth that has been attained, as depicted in the schematic below:

Conclusion

CRM is widely accepted as an effective tool in training individuals in many high performing industries. This article describes a framework in which the principles of CRM can be applied to hospital medicine to maintain positive work culture.

Dr. Prabhakaran is director of hospital medicine transitions of care, Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Mass., and assistant professor of medicine, University of Massachusetts, Worcester. Dr. Medarametla is medical director, hospital medicine, Baystate Medical Center, and assistant professor of medicine, University of Massachusetts.

References

1. Haerkens MH et al. Crew Resource Management in the ICU: The need for culture change. Ann Intensive Care. 2012 Aug 22;2:39.

2. Haerkens MH et al. Crew Resource Management in the trauma room: A prospective 3-year cohort study. Eur J Emerg Med. 2018 Aug;25(4):281-7.

3. Malcolm Gladwell. The ethnic theory of plane crashes. Outliers: The Story of Success. (Boston: Little, Brown and Company; 2008:177-223).

4. Helmreich RL et al. The evolution of Crew Resource Management training in commercial aviation. Int J Aviat Psychol. 1999;9(1):19-32.

5. Forsyth DR. The psychology of groups. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, Ill: DEF publishers; 2017.

6. Crew Resource Management. Available at Aviation Knowledge. Accessed Dec. 20, 2017.

“Workplace culture” has a profound influence on the success or failure of a team in the modern-day work environment, where teamwork and interpersonal interactions have paramount importance. Crew resource management (CRM), a technique developed originally by the airline industry, has been used as a tool to improve safety and quality in ICUs, trauma rooms, and operating rooms.1,2 This article discusses the use of CRM in hospital medicine as a tool for training and maintaining a favorable workplace culture.

Origin and evolution of CRM

United Airlines instituted the airline industry’s first crew resource management for pilots in 1981, following the 1978 crash of United Flight 173 in Portland, Ore. CRM was created based on recommendations from the National Transportation Safety Board and from a NASA workshop held subsequently.3 CRM has since evolved through five generations, and is a required annual training for most major commercial airline companies around the world. It also has been adapted for personnel training by several modern international industries.4

From the airline industry to the hospital

The health care industry is similar to the airline industry in that there is absolutely no margin of error, and that workplace culture plays a very important role. The culture being referred to here is the sum total of values, beliefs, work ethics, work strategies, strengths, and weaknesses of a group of people, and how they interact as a group. In other words, it is the dynamics of a group.

According to Donelson R. Forsyth, a social and personality psychologist at the University of Richmond (Virginia), the two key determinants of successful teamwork are a “shared mental representation of the task,” which refers to an in-depth understanding of the team and the tasks they are attempting; and “group unity/cohesion,” which means that, generally, members of cohesive groups like each other and the group, and they also are united in their pursuit of collective, group-level goals.5

Understanding the culture of a hospitalist team

Analyzing group dynamics and actively managing them toward both the institutional and global goals of health care is critical for the success of an organization. This is the core of successfully managing any team in any industry.

Additionally, the rapidly changing health care climate and insurance payment systems requires hospital medicine groups to rapidly adapt to the constantly changing health care business environment. As a result, there are a couple of ways to evaluate the effectiveness of the team:

- Measure tangible outcomes. The outcomes have to be well defined, important and measurable. These could be cost of care, quality of care, engagement of the team etc. These tangible measures’ outcome over a period of time can be used as a measure of how effective the team is.

- Simply ask your team! It is very important to know what core values the team holds dear. The best way to get that information from the team is to find out the de facto leaders of the team. They should be involved in the decision-making process, thus making them valuable to the management as well as the team.

Culture shapes outcomes

We have used the analogy of a convex and concave lens to help understand this better. A well-developed and well-coordinated team is like convex lens. A lens’ ability to converge or diverge light rays depends on certain characteristics like the curvature of surfaces and refractory index. Likewise, the culture of a group determines its ability to transform all the demands of the collective workload toward a unified goal/outcome. If it is favorable, the group will work as one and success will happen automatically.

Unfortunately, the opposite of this, (the concave lens effect), is more commonplace, where the dynamics of a team prevent the goals being achieved, as there is discordance, poor coordination of ideas and values, and team members not liking each other.

Most teams would fall somewhere within this spectrum, spanning the most favorable convex lens–like group to the least favorable concave lens–like group.

Change team dynamics using CRM principles

The concept of using CRM principles in health care is not entirely new. Such agencies as the Joint Commission and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality recommend using principles of CRM to improve communications, and as an error-prevention tool in health care.6

This approach can be broken down into four important steps:

1. Recruit right. It is important to make sure that the new recruit is the right fit for the team and that the de facto leaders and a few other team members are involved in interviewing the candidates. Their assessment should be given due consideration in making the decision to give the new recruit the job.

Every program looks for aspects like clinical competence, interpersonal communication, teamwork, etc., in a candidate, but it is even more important to make sure the candidate has the tenets that would make him/her a part of that particular team.

2. Train well. The newly recruited providers should be given focused training and the seasoned providers should be given refresher training at regular intervals. Care should be taken in designing the training programs in such a way that the providers are trained in skills that they don’t always think about, things that aren’t readily obvious, and in skills that they never get trained in during medical school and residency.

Specifically, they should be trained in:

- Values. These should include the values of both the organization and the team.

- Safety. This should include all the safety protocols that are in place in the organization - where to get help, how to report unsafe events etc.

- Communication.

Within the group: Have a mentor for the new provider, and also develop a culture where he/she feels comfortable to reach out to anyone in the team for help.

With patients and families: This training should ideally be done in a simulated environment if possible.

With other groups in the hospital: Consultants, nurses, other ancillary staff. Give them an idea about the prevailing culture in the organization with regard to these groups, so that they know what to expect when dealing with them.

- Managing perceptions. How the providers are viewed in the hospital, and how to improve it or maintain it.

- Nurturing the good. Use positive reinforcements to solidify the positive aspects of group dynamics these individuals might possess.

- Weeding out the bad. Use training and feedback to alter the negative group dynamic aspects.

3. Intervene. This is necessary either to maintain the positive aspects of a team that is already high-functioning, or to transform a poorly functioning team into a well-coordinated team. This is where the principles of CRM are going to be most useful.

There are five generations of CRM, each with a different focus.6 Only the aspects relevant to hospital medicine training are mentioned here.

- Communication. Address the gaps in communication. It is important to include people who are trusted by the team in designing and executing these sessions.

- Leadership. The goal should be to encourage the team to take ownership of the program. This will make a tremendous change in the ability of a team to deliver and rise up to challenges. The organizational leadership has to be willing to elevate the leaders of the group to positions where they can meaningfully take part in managing the team and making decisions that are critical to the team.

- Burnout management. Providers getting disillusioned: having no work-life balance; not getting enough respect from management, as well as other groups of doctors/nurses/etc. in the hospital; they are subject to bad scheduling and poor pay – all of which can all lead to career-ending burnout. It is important to recognize this and mitigate the factors that cause burnout.

- Organizational culture. If the team feels valued and supported, they will, in turn, work hard toward success. Creative leadership and a willingness to accommodate what matters the most to the team is essential for achieving this.

- Simulated training. These can be done in simulation labs, or in-group sessions with the team, re-creating difficult scenarios or problems in which the whole team can come together and solve them.

- Error containment and management. The team needs to identify possible sources of error and contain them before errors happen. The group should get together if a serious event happens and brainstorm why it happened and take measures to prevent it.

4. Reevaluate. Team dynamics tend to change over time. It is important to constantly re-evaluate the team and make sure that the team’s culture remains favorable. There should be recurrent cycles of retraining and interventions to maintain the positive growth that has been attained, as depicted in the schematic below:

Conclusion

CRM is widely accepted as an effective tool in training individuals in many high performing industries. This article describes a framework in which the principles of CRM can be applied to hospital medicine to maintain positive work culture.

Dr. Prabhakaran is director of hospital medicine transitions of care, Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Mass., and assistant professor of medicine, University of Massachusetts, Worcester. Dr. Medarametla is medical director, hospital medicine, Baystate Medical Center, and assistant professor of medicine, University of Massachusetts.

References

1. Haerkens MH et al. Crew Resource Management in the ICU: The need for culture change. Ann Intensive Care. 2012 Aug 22;2:39.

2. Haerkens MH et al. Crew Resource Management in the trauma room: A prospective 3-year cohort study. Eur J Emerg Med. 2018 Aug;25(4):281-7.

3. Malcolm Gladwell. The ethnic theory of plane crashes. Outliers: The Story of Success. (Boston: Little, Brown and Company; 2008:177-223).

4. Helmreich RL et al. The evolution of Crew Resource Management training in commercial aviation. Int J Aviat Psychol. 1999;9(1):19-32.

5. Forsyth DR. The psychology of groups. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, Ill: DEF publishers; 2017.

6. Crew Resource Management. Available at Aviation Knowledge. Accessed Dec. 20, 2017.

Living into your legacy

What I learned from women of impact

The word legacy has been synonymous with death to me. When so and so dies, we discuss their legacy. I had a powerful experience that changed my mind on this word that is befitting for this Legacies column.

Seven years ago, I was sitting in a room of powerful women and I was the youngest one there. I wasn’t sure how I got there, but I was glad I did because it changed my life. At the time, I was panicked. The exercise was called “Craft your legacy statement.”

But, this exercise was different. The ask was to “live into your legacy.” Craft a legacy statement in THREE minutes that summarizes what you want your legacy to be … and then decide the three things you need to do now to get there. So, here is my exact legacy 3-minute statement: I am an innovator pushing teaching hospitals to optimize training and patient care delivery through novel technologies and systems science. Clearly, I did not aim high enough. One of the other attendees stated her legacy simply as “Unleash the impossible!” So clearly, I was not able to think big at that moment, but I trudged on.

Next, I had to write the three things I was going to do to enact my legacy today. Things went from bad to worse quickly since I knew this was not going to be easy. The #1 thing had to be something I was going to stop doing because it did not fit with my legacy; #2 was what I was going to start doing to enact this legacy now; and, #3 was something I was going to do to get me closer to what I wanted to be doing. So, my #1, resign my current leadership role that I had had for 8 years; #2, start joining national committees that bridge education and quality; and #3, meet with senior leadership to pitch this new role as a bridging leader, aligning education and quality.

Like all conferences, I went home and forgot what I had done and learned. I settled back into my old life and routines. A few weeks later, a plain looking envelope with awful penmanship showed up at my doorstep addressed to me. It wasn’t until after I opened it and read what was inside that I realized I was the one with horrible penmanship! I completely forgot that I wrote this letter to myself even though they told me it would come and I would forget I wrote it! So, how did I do? Let’s just say if the letter did not arrive, I am not sure where I would be. Fortunately, it did come, and I followed my own orders. Fast forward to present day and I recently stepped into a new role – associate chief medical officer: clinical learning environment – a bridging leader who aligns education and clinical care missions for our health system. Let’s just say again, had that letter not arrived, I am not sure where I would be now.

I have been fortunate to do many things in hospital medicine – clinician, researcher, educator, and my latest role as a leader. Through it all, I would say that there are some lessons that I have picked up along the way that helped me advance, in ways I did not realize:

- Be bold. Years ago, when I was asked by my chair who they should pick to be chief resident, I thought “This must be a trick question – I should definitely tell him why I should be chosen – and then pick the next best person who I want to work with.” Apparently, I was the only person who did that, and that is why my chair chose me. Everyone else picked two other people. So the take-home point here is do not sell yourself short … ever.

- Look for the hidden gateways. A few years ago, I was asked if I wanted to be an institutional leader by the person who currently had that role. I was kind of thrown for a loop, since of course I would not want to appear like I wanted to take his job. I said everything was fine and I felt pretty good about my current positions. It was only a few weeks later that I realized that he was ascertaining my interest in his job since he was leaving. They gave the job to someone else and the word on the street was I was not interested. I totally missed the gate! While it wasn’t necessarily the job I missed out on, it was the opportunity to consider the job because I was afraid. So, don’t miss the gate. It’s the wormhole to a different life that may be the right one for you, but you need to “see it” to seize it.

- Work hard for the money and for the fun. There are many things Gwyneth Paltrow does that I do not agree with, but I will give her credit for one important lesson: she divides her movie roles into those she does for love (for example, The Royal Tenenbaums) and those she does for money (for example, Shallow Hal). It made me realize that even a Hollywood starlet has to do the stuff she may not want to do for the money. So, as a young person, you have to work hard for the money, but ideally it will help you take on a project you love, whatever it is. You’ve won the game when you’re mostly paid to work for the fun ... but that may take some time.

- Always optimize what is best for you personally AND professionally. While I was on maternity leave, the job of my dreams presented itself – or so I thought it did. It was at the intersection of policy, quality, and education, with a national stage, and I would not need to move. But, I knew I could not accept the travel commitment with a young child. While I wondered if I would have regrets, it turns out the right decision professionally also has to work personally. Likewise, there are professional obligations that I take on because it works personally.

- Figure out who your tea house pals are. A few years ago, I was in San Francisco with two close friends having an epic moment about what to do with our lives as adults. We were all on the cusp of changing our directions. Not surprisingly, we could see what the other needed to do, but we could not see it for ourselves. We still text each other sometimes about the need to go back to the Tea House. Sometimes your “tea house pals” are not necessarily those around you every day. They know you, but not everyone in your work place. This “arm’s length” or distance gives them the rational, unbiased perspective to advise you, that you or your colleagues will never have.

- Look for ways to enjoy the journey. Medicine is a very long road. I routinely think about this working with all the trainees and junior faculty I encounter. You can’t be in this solely for the end of the journey. The key is to find the joy in the journey. For me, that has always come from seeking out like-minded fellow travelers to share my highs and lows. While I tweet for many reasons, a big reason is that I take pleasure in watching others on the journey and also sharing my own journey.

Here’s to your journey and living your legacy!

Dr. Arora is associate chief medical officer, clinical learning environment, at University of Chicago Medicine, and assistant dean for scholarship and discovery at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine. You can follow her journey on Twitter.

What I learned from women of impact

What I learned from women of impact

The word legacy has been synonymous with death to me. When so and so dies, we discuss their legacy. I had a powerful experience that changed my mind on this word that is befitting for this Legacies column.

Seven years ago, I was sitting in a room of powerful women and I was the youngest one there. I wasn’t sure how I got there, but I was glad I did because it changed my life. At the time, I was panicked. The exercise was called “Craft your legacy statement.”

But, this exercise was different. The ask was to “live into your legacy.” Craft a legacy statement in THREE minutes that summarizes what you want your legacy to be … and then decide the three things you need to do now to get there. So, here is my exact legacy 3-minute statement: I am an innovator pushing teaching hospitals to optimize training and patient care delivery through novel technologies and systems science. Clearly, I did not aim high enough. One of the other attendees stated her legacy simply as “Unleash the impossible!” So clearly, I was not able to think big at that moment, but I trudged on.

Next, I had to write the three things I was going to do to enact my legacy today. Things went from bad to worse quickly since I knew this was not going to be easy. The #1 thing had to be something I was going to stop doing because it did not fit with my legacy; #2 was what I was going to start doing to enact this legacy now; and, #3 was something I was going to do to get me closer to what I wanted to be doing. So, my #1, resign my current leadership role that I had had for 8 years; #2, start joining national committees that bridge education and quality; and #3, meet with senior leadership to pitch this new role as a bridging leader, aligning education and quality.

Like all conferences, I went home and forgot what I had done and learned. I settled back into my old life and routines. A few weeks later, a plain looking envelope with awful penmanship showed up at my doorstep addressed to me. It wasn’t until after I opened it and read what was inside that I realized I was the one with horrible penmanship! I completely forgot that I wrote this letter to myself even though they told me it would come and I would forget I wrote it! So, how did I do? Let’s just say if the letter did not arrive, I am not sure where I would be. Fortunately, it did come, and I followed my own orders. Fast forward to present day and I recently stepped into a new role – associate chief medical officer: clinical learning environment – a bridging leader who aligns education and clinical care missions for our health system. Let’s just say again, had that letter not arrived, I am not sure where I would be now.

I have been fortunate to do many things in hospital medicine – clinician, researcher, educator, and my latest role as a leader. Through it all, I would say that there are some lessons that I have picked up along the way that helped me advance, in ways I did not realize:

- Be bold. Years ago, when I was asked by my chair who they should pick to be chief resident, I thought “This must be a trick question – I should definitely tell him why I should be chosen – and then pick the next best person who I want to work with.” Apparently, I was the only person who did that, and that is why my chair chose me. Everyone else picked two other people. So the take-home point here is do not sell yourself short … ever.

- Look for the hidden gateways. A few years ago, I was asked if I wanted to be an institutional leader by the person who currently had that role. I was kind of thrown for a loop, since of course I would not want to appear like I wanted to take his job. I said everything was fine and I felt pretty good about my current positions. It was only a few weeks later that I realized that he was ascertaining my interest in his job since he was leaving. They gave the job to someone else and the word on the street was I was not interested. I totally missed the gate! While it wasn’t necessarily the job I missed out on, it was the opportunity to consider the job because I was afraid. So, don’t miss the gate. It’s the wormhole to a different life that may be the right one for you, but you need to “see it” to seize it.

- Work hard for the money and for the fun. There are many things Gwyneth Paltrow does that I do not agree with, but I will give her credit for one important lesson: she divides her movie roles into those she does for love (for example, The Royal Tenenbaums) and those she does for money (for example, Shallow Hal). It made me realize that even a Hollywood starlet has to do the stuff she may not want to do for the money. So, as a young person, you have to work hard for the money, but ideally it will help you take on a project you love, whatever it is. You’ve won the game when you’re mostly paid to work for the fun ... but that may take some time.

- Always optimize what is best for you personally AND professionally. While I was on maternity leave, the job of my dreams presented itself – or so I thought it did. It was at the intersection of policy, quality, and education, with a national stage, and I would not need to move. But, I knew I could not accept the travel commitment with a young child. While I wondered if I would have regrets, it turns out the right decision professionally also has to work personally. Likewise, there are professional obligations that I take on because it works personally.

- Figure out who your tea house pals are. A few years ago, I was in San Francisco with two close friends having an epic moment about what to do with our lives as adults. We were all on the cusp of changing our directions. Not surprisingly, we could see what the other needed to do, but we could not see it for ourselves. We still text each other sometimes about the need to go back to the Tea House. Sometimes your “tea house pals” are not necessarily those around you every day. They know you, but not everyone in your work place. This “arm’s length” or distance gives them the rational, unbiased perspective to advise you, that you or your colleagues will never have.

- Look for ways to enjoy the journey. Medicine is a very long road. I routinely think about this working with all the trainees and junior faculty I encounter. You can’t be in this solely for the end of the journey. The key is to find the joy in the journey. For me, that has always come from seeking out like-minded fellow travelers to share my highs and lows. While I tweet for many reasons, a big reason is that I take pleasure in watching others on the journey and also sharing my own journey.

Here’s to your journey and living your legacy!

Dr. Arora is associate chief medical officer, clinical learning environment, at University of Chicago Medicine, and assistant dean for scholarship and discovery at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine. You can follow her journey on Twitter.

The word legacy has been synonymous with death to me. When so and so dies, we discuss their legacy. I had a powerful experience that changed my mind on this word that is befitting for this Legacies column.

Seven years ago, I was sitting in a room of powerful women and I was the youngest one there. I wasn’t sure how I got there, but I was glad I did because it changed my life. At the time, I was panicked. The exercise was called “Craft your legacy statement.”

But, this exercise was different. The ask was to “live into your legacy.” Craft a legacy statement in THREE minutes that summarizes what you want your legacy to be … and then decide the three things you need to do now to get there. So, here is my exact legacy 3-minute statement: I am an innovator pushing teaching hospitals to optimize training and patient care delivery through novel technologies and systems science. Clearly, I did not aim high enough. One of the other attendees stated her legacy simply as “Unleash the impossible!” So clearly, I was not able to think big at that moment, but I trudged on.

Next, I had to write the three things I was going to do to enact my legacy today. Things went from bad to worse quickly since I knew this was not going to be easy. The #1 thing had to be something I was going to stop doing because it did not fit with my legacy; #2 was what I was going to start doing to enact this legacy now; and, #3 was something I was going to do to get me closer to what I wanted to be doing. So, my #1, resign my current leadership role that I had had for 8 years; #2, start joining national committees that bridge education and quality; and #3, meet with senior leadership to pitch this new role as a bridging leader, aligning education and quality.

Like all conferences, I went home and forgot what I had done and learned. I settled back into my old life and routines. A few weeks later, a plain looking envelope with awful penmanship showed up at my doorstep addressed to me. It wasn’t until after I opened it and read what was inside that I realized I was the one with horrible penmanship! I completely forgot that I wrote this letter to myself even though they told me it would come and I would forget I wrote it! So, how did I do? Let’s just say if the letter did not arrive, I am not sure where I would be. Fortunately, it did come, and I followed my own orders. Fast forward to present day and I recently stepped into a new role – associate chief medical officer: clinical learning environment – a bridging leader who aligns education and clinical care missions for our health system. Let’s just say again, had that letter not arrived, I am not sure where I would be now.

I have been fortunate to do many things in hospital medicine – clinician, researcher, educator, and my latest role as a leader. Through it all, I would say that there are some lessons that I have picked up along the way that helped me advance, in ways I did not realize:

- Be bold. Years ago, when I was asked by my chair who they should pick to be chief resident, I thought “This must be a trick question – I should definitely tell him why I should be chosen – and then pick the next best person who I want to work with.” Apparently, I was the only person who did that, and that is why my chair chose me. Everyone else picked two other people. So the take-home point here is do not sell yourself short … ever.

- Look for the hidden gateways. A few years ago, I was asked if I wanted to be an institutional leader by the person who currently had that role. I was kind of thrown for a loop, since of course I would not want to appear like I wanted to take his job. I said everything was fine and I felt pretty good about my current positions. It was only a few weeks later that I realized that he was ascertaining my interest in his job since he was leaving. They gave the job to someone else and the word on the street was I was not interested. I totally missed the gate! While it wasn’t necessarily the job I missed out on, it was the opportunity to consider the job because I was afraid. So, don’t miss the gate. It’s the wormhole to a different life that may be the right one for you, but you need to “see it” to seize it.

- Work hard for the money and for the fun. There are many things Gwyneth Paltrow does that I do not agree with, but I will give her credit for one important lesson: she divides her movie roles into those she does for love (for example, The Royal Tenenbaums) and those she does for money (for example, Shallow Hal). It made me realize that even a Hollywood starlet has to do the stuff she may not want to do for the money. So, as a young person, you have to work hard for the money, but ideally it will help you take on a project you love, whatever it is. You’ve won the game when you’re mostly paid to work for the fun ... but that may take some time.

- Always optimize what is best for you personally AND professionally. While I was on maternity leave, the job of my dreams presented itself – or so I thought it did. It was at the intersection of policy, quality, and education, with a national stage, and I would not need to move. But, I knew I could not accept the travel commitment with a young child. While I wondered if I would have regrets, it turns out the right decision professionally also has to work personally. Likewise, there are professional obligations that I take on because it works personally.