User login

Studies need to address best follow-on therapy to ibrutinib in CLL

Reporting AT LYMPHOMA & MYELOMA 2017

NEW YORK – Clinical trials are needed to determine the best follow-on therapies when patients discontinue the ibrutinib due to adverse events or disease progression, according to a leading expert on chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Anthony Mato, MD, MSCE, from the Abramson Cancer Center at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, discussed how real-world experience with the use of ibrutinib (Imbruvica) can fill the gaps in knowledge left by clinical trials and point to the need for further study.

“Regulatory bodies around the world are more and more interested in what’s going on in the clinic, and there is a question about whether or not the experiences for patients that we take care of might actually answer some important questions that aren’t easily answered in the context of clinical research,” he said at the annual Lymphoma & Myeloma International Congress on Hematologic Malignancies here.

“Are the experiences in practice with novel agents similar to experiences from clinical trials? I think that’s very important,” he added.

Other important questions that real-world experience may help to answer include whether it’s possible to refine adverse event profiles and reasons for ibrutinib discontinuation, what therapies should be prescribed after ibrutinib, and what is the optimal sequencing of therapies for CLL.

For example, in the RESONATE-2 trial, an open-label, international phase 3 study comparing ibrutinib with chlorambucil in previously untreated patients 65 and older, ibrutinib was found to be superior to chlorambucil in terms of progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), response rate, and improvements in hematologic variables.

However, this trial excluded patients with the deleterious chromosome 17p deletion (del17p) and included only patients 65 and older, a population that does not necessarily reflect clinical experience.

To get a better sense of how ibrutinib is used to treat CLL in the front-line setting Dr. Mato and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study of 391 patients treated in 19 US and international academic and community centers.

The median age of the sample was 68 years, but 41% of the patients were younger than 65. In all, 62% were male, and 80% had Rai stage 2 or greater disease. Genetic analyses showed that 30% of the patients were positive for del17p, and 17% had both del17p and the 11q deletion (del11q). Mutations in TP53 were seen in 20% of patients, 23% had a complex karyotype, and 67% had an unmutated immuglobulin heavy chain variable region (IGHV). Only 57 patients (14.5%) were classified as genetically low risk.

Additionally, only 79 of the 391 patients had complete data for CLL International Prognostic Index (CLL-IPI) scoring, “which goes, I think, to show how often this is actually being tested and utilized in clinical practice,” Dr. Mato said.

Off-label use of ibrutinib in combination therapy was given to 16% of patients, most commonly with an anti-CD20 inhibitor such as rituximab.

In all, 17% of patients required permanent dose reductions; and 42% had a dose interruption, with a median hiatus of 12 days.

Grade 3 or 4 adverse events were uncommon, but more than 20% of patients experienced arthralgias or myalgias of any kind, about 19% reported fatigue, 18% had dermatologic toxicities, 18% reported bruising, 17% had diarrhea or colitis and 15% had infections.

The toxicities seen in RESONATE-2 were somewhat similar, but generally occurred in higher frequencies in the trial than in real-world practice.

Dr. Mato and colleagues found that at a median of 12 months of follow-up, 24% of patients had discontinued ibrutinib. In contrast, in RESONATE-2, after 18 months of follow-up, 13% of patients had discontinued the drug.

The most common reasons for discontinuation in clinical practice were for toxicities (59.5% of 94 discontinuations) including atrial fibrillation in 20% of the patients who discontinued, arthralgias/myalgias and skin toxicities in 14.5% each, and bleeding in 9.1%.

Other reasons for discontinuation included Richter’s transformation in 9.6%, doctor or patient preference in 7.4%, and deaths that were not secondary to CLL progression in 3.2%.

“We also tried to get a sense of whether or not cost was a factor for patients, and in this series and the relapsed refractory setting, 1% or less of patients discontinued due to financial issues,” Dr. Mato said.

Outcomes in the real word were quite good, he noted, with an overall response rate (ORR) of 81.7%, which included 17.4% complete responses (CR), Neither median PFS nor OS have been reached and the respective PFS and OS at 12 months were 92% and 95%. The respective PFS and OS rates for patients with del17p were 87% and 89%. An analysis of predictors of survival showed that only the presence of del17p was associated with inferior PFS (odds ratio 1.91, P = .035)

Dr. Mato noted that there was no clear standard treatment approach for patients who discontinued ibrutinib or for whom ibrutinib did not work. The top three second-line approaches used included an anti-CD20 agent combined with chlorambucil, venetoclax (Venclexta), or a different kinase inhibitor. Chemoimmunotherapy with either fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab or bendamustine and rituximab was given to only 5 patients as a second line therapy.

Dr. Mato disclosed serving as a consultant for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Janssen/Pharmacyclics, and TG Therapeutics.

Reporting AT LYMPHOMA & MYELOMA 2017

NEW YORK – Clinical trials are needed to determine the best follow-on therapies when patients discontinue the ibrutinib due to adverse events or disease progression, according to a leading expert on chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Anthony Mato, MD, MSCE, from the Abramson Cancer Center at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, discussed how real-world experience with the use of ibrutinib (Imbruvica) can fill the gaps in knowledge left by clinical trials and point to the need for further study.

“Regulatory bodies around the world are more and more interested in what’s going on in the clinic, and there is a question about whether or not the experiences for patients that we take care of might actually answer some important questions that aren’t easily answered in the context of clinical research,” he said at the annual Lymphoma & Myeloma International Congress on Hematologic Malignancies here.

“Are the experiences in practice with novel agents similar to experiences from clinical trials? I think that’s very important,” he added.

Other important questions that real-world experience may help to answer include whether it’s possible to refine adverse event profiles and reasons for ibrutinib discontinuation, what therapies should be prescribed after ibrutinib, and what is the optimal sequencing of therapies for CLL.

For example, in the RESONATE-2 trial, an open-label, international phase 3 study comparing ibrutinib with chlorambucil in previously untreated patients 65 and older, ibrutinib was found to be superior to chlorambucil in terms of progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), response rate, and improvements in hematologic variables.

However, this trial excluded patients with the deleterious chromosome 17p deletion (del17p) and included only patients 65 and older, a population that does not necessarily reflect clinical experience.

To get a better sense of how ibrutinib is used to treat CLL in the front-line setting Dr. Mato and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study of 391 patients treated in 19 US and international academic and community centers.

The median age of the sample was 68 years, but 41% of the patients were younger than 65. In all, 62% were male, and 80% had Rai stage 2 or greater disease. Genetic analyses showed that 30% of the patients were positive for del17p, and 17% had both del17p and the 11q deletion (del11q). Mutations in TP53 were seen in 20% of patients, 23% had a complex karyotype, and 67% had an unmutated immuglobulin heavy chain variable region (IGHV). Only 57 patients (14.5%) were classified as genetically low risk.

Additionally, only 79 of the 391 patients had complete data for CLL International Prognostic Index (CLL-IPI) scoring, “which goes, I think, to show how often this is actually being tested and utilized in clinical practice,” Dr. Mato said.

Off-label use of ibrutinib in combination therapy was given to 16% of patients, most commonly with an anti-CD20 inhibitor such as rituximab.

In all, 17% of patients required permanent dose reductions; and 42% had a dose interruption, with a median hiatus of 12 days.

Grade 3 or 4 adverse events were uncommon, but more than 20% of patients experienced arthralgias or myalgias of any kind, about 19% reported fatigue, 18% had dermatologic toxicities, 18% reported bruising, 17% had diarrhea or colitis and 15% had infections.

The toxicities seen in RESONATE-2 were somewhat similar, but generally occurred in higher frequencies in the trial than in real-world practice.

Dr. Mato and colleagues found that at a median of 12 months of follow-up, 24% of patients had discontinued ibrutinib. In contrast, in RESONATE-2, after 18 months of follow-up, 13% of patients had discontinued the drug.

The most common reasons for discontinuation in clinical practice were for toxicities (59.5% of 94 discontinuations) including atrial fibrillation in 20% of the patients who discontinued, arthralgias/myalgias and skin toxicities in 14.5% each, and bleeding in 9.1%.

Other reasons for discontinuation included Richter’s transformation in 9.6%, doctor or patient preference in 7.4%, and deaths that were not secondary to CLL progression in 3.2%.

“We also tried to get a sense of whether or not cost was a factor for patients, and in this series and the relapsed refractory setting, 1% or less of patients discontinued due to financial issues,” Dr. Mato said.

Outcomes in the real word were quite good, he noted, with an overall response rate (ORR) of 81.7%, which included 17.4% complete responses (CR), Neither median PFS nor OS have been reached and the respective PFS and OS at 12 months were 92% and 95%. The respective PFS and OS rates for patients with del17p were 87% and 89%. An analysis of predictors of survival showed that only the presence of del17p was associated with inferior PFS (odds ratio 1.91, P = .035)

Dr. Mato noted that there was no clear standard treatment approach for patients who discontinued ibrutinib or for whom ibrutinib did not work. The top three second-line approaches used included an anti-CD20 agent combined with chlorambucil, venetoclax (Venclexta), or a different kinase inhibitor. Chemoimmunotherapy with either fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab or bendamustine and rituximab was given to only 5 patients as a second line therapy.

Dr. Mato disclosed serving as a consultant for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Janssen/Pharmacyclics, and TG Therapeutics.

Reporting AT LYMPHOMA & MYELOMA 2017

NEW YORK – Clinical trials are needed to determine the best follow-on therapies when patients discontinue the ibrutinib due to adverse events or disease progression, according to a leading expert on chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Anthony Mato, MD, MSCE, from the Abramson Cancer Center at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, discussed how real-world experience with the use of ibrutinib (Imbruvica) can fill the gaps in knowledge left by clinical trials and point to the need for further study.

“Regulatory bodies around the world are more and more interested in what’s going on in the clinic, and there is a question about whether or not the experiences for patients that we take care of might actually answer some important questions that aren’t easily answered in the context of clinical research,” he said at the annual Lymphoma & Myeloma International Congress on Hematologic Malignancies here.

“Are the experiences in practice with novel agents similar to experiences from clinical trials? I think that’s very important,” he added.

Other important questions that real-world experience may help to answer include whether it’s possible to refine adverse event profiles and reasons for ibrutinib discontinuation, what therapies should be prescribed after ibrutinib, and what is the optimal sequencing of therapies for CLL.

For example, in the RESONATE-2 trial, an open-label, international phase 3 study comparing ibrutinib with chlorambucil in previously untreated patients 65 and older, ibrutinib was found to be superior to chlorambucil in terms of progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), response rate, and improvements in hematologic variables.

However, this trial excluded patients with the deleterious chromosome 17p deletion (del17p) and included only patients 65 and older, a population that does not necessarily reflect clinical experience.

To get a better sense of how ibrutinib is used to treat CLL in the front-line setting Dr. Mato and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study of 391 patients treated in 19 US and international academic and community centers.

The median age of the sample was 68 years, but 41% of the patients were younger than 65. In all, 62% were male, and 80% had Rai stage 2 or greater disease. Genetic analyses showed that 30% of the patients were positive for del17p, and 17% had both del17p and the 11q deletion (del11q). Mutations in TP53 were seen in 20% of patients, 23% had a complex karyotype, and 67% had an unmutated immuglobulin heavy chain variable region (IGHV). Only 57 patients (14.5%) were classified as genetically low risk.

Additionally, only 79 of the 391 patients had complete data for CLL International Prognostic Index (CLL-IPI) scoring, “which goes, I think, to show how often this is actually being tested and utilized in clinical practice,” Dr. Mato said.

Off-label use of ibrutinib in combination therapy was given to 16% of patients, most commonly with an anti-CD20 inhibitor such as rituximab.

In all, 17% of patients required permanent dose reductions; and 42% had a dose interruption, with a median hiatus of 12 days.

Grade 3 or 4 adverse events were uncommon, but more than 20% of patients experienced arthralgias or myalgias of any kind, about 19% reported fatigue, 18% had dermatologic toxicities, 18% reported bruising, 17% had diarrhea or colitis and 15% had infections.

The toxicities seen in RESONATE-2 were somewhat similar, but generally occurred in higher frequencies in the trial than in real-world practice.

Dr. Mato and colleagues found that at a median of 12 months of follow-up, 24% of patients had discontinued ibrutinib. In contrast, in RESONATE-2, after 18 months of follow-up, 13% of patients had discontinued the drug.

The most common reasons for discontinuation in clinical practice were for toxicities (59.5% of 94 discontinuations) including atrial fibrillation in 20% of the patients who discontinued, arthralgias/myalgias and skin toxicities in 14.5% each, and bleeding in 9.1%.

Other reasons for discontinuation included Richter’s transformation in 9.6%, doctor or patient preference in 7.4%, and deaths that were not secondary to CLL progression in 3.2%.

“We also tried to get a sense of whether or not cost was a factor for patients, and in this series and the relapsed refractory setting, 1% or less of patients discontinued due to financial issues,” Dr. Mato said.

Outcomes in the real word were quite good, he noted, with an overall response rate (ORR) of 81.7%, which included 17.4% complete responses (CR), Neither median PFS nor OS have been reached and the respective PFS and OS at 12 months were 92% and 95%. The respective PFS and OS rates for patients with del17p were 87% and 89%. An analysis of predictors of survival showed that only the presence of del17p was associated with inferior PFS (odds ratio 1.91, P = .035)

Dr. Mato noted that there was no clear standard treatment approach for patients who discontinued ibrutinib or for whom ibrutinib did not work. The top three second-line approaches used included an anti-CD20 agent combined with chlorambucil, venetoclax (Venclexta), or a different kinase inhibitor. Chemoimmunotherapy with either fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab or bendamustine and rituximab was given to only 5 patients as a second line therapy.

Dr. Mato disclosed serving as a consultant for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Janssen/Pharmacyclics, and TG Therapeutics.

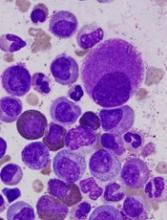

Team discovers mechanism of resistance in AML

Researchers say they have uncovered a target to overcome drug resistance in acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

The team discovered how a linkage between 2 proteins enables AML cells to resist chemotherapy and showed that disrupting the linkage could render the cells vulnerable to treatment.

The researchers believe their discovery could lead to drugs to enhance chemotherapy in patients with AML and other cancers.

John Schuetz, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, and his colleagues described this research in Nature Communications.

The team launched their experiments based on previous findings that a protein called ABCC4 was greatly elevated in aggressive cases of AML.

Dr Schuetz and his colleagues searched for other proteins that might interact with ABCC4 and enable its function. The team’s screening of candidate proteins yielded one, MPP1, which was also greatly increased in AML.

The researchers found the 2 proteins are connected, and the connection enables cells to assume the characteristics of highly proliferative leukemia cells.

These experiments involved genetically altering hematopoietic progenitor cells to have high MPP1 and ABCC4 levels. The cells were grown in culture and then replated to see if they would continue to grow, as such self-renewal is a hallmark of leukemia cells.

The researchers found that serial regrowth depended on the cells having high levels of both ABCC4 and MPP1.

“Typically, if you take normal progenitors and you replate, you could do that one time, maybe twice,” Dr Schuetz said. “But our big surprise was that overexpressing MPP1—analogous to what you would see in leukemia—allows those progenitors to self-renew, to be replated over and over, to form new colonies.”

The experiments also revealed that MPP1 and ABCC4 functioned at the cell membrane, where they could play a role in the machinery that would rid the leukemia cells of chemotherapy drugs.

“When we disrupted their interaction, ABCC4 moved off the membrane and the cells became more sensitive to drugs used in AML—drugs that are pumped out of the cell by ABCC4,” Dr Schuetz said.

By screening thousands of compounds, the researchers identified some that could disrupt the ABCC4-MPP1 connection. One, called Antimycin-A, reversed drug resistance in AML cell lines and in cells from AML patients.

Antimycin-A is too toxic to be used in chemotherapy, but the researchers believe identification of the compound should aid the search for other, less-toxic drugs to disrupt the ABCC4-MPP1 interaction.

The team’s findings could also enable clinicians to identify AML patients with high levels of ABCC4 and MPP1. In such patients, drugs that disrupt ABCC4-MPP1 might enhance the effectiveness of standard chemotherapy, Dr Schuetz said.

He also noted that other cancers, including breast and colon cancer and medulloblastoma, show high levels of both ABCC4 and MPP1. Chemotherapy for those cancers might also be enhanced by drugs that disrupt ABCC4-MPP1. ![]()

Researchers say they have uncovered a target to overcome drug resistance in acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

The team discovered how a linkage between 2 proteins enables AML cells to resist chemotherapy and showed that disrupting the linkage could render the cells vulnerable to treatment.

The researchers believe their discovery could lead to drugs to enhance chemotherapy in patients with AML and other cancers.

John Schuetz, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, and his colleagues described this research in Nature Communications.

The team launched their experiments based on previous findings that a protein called ABCC4 was greatly elevated in aggressive cases of AML.

Dr Schuetz and his colleagues searched for other proteins that might interact with ABCC4 and enable its function. The team’s screening of candidate proteins yielded one, MPP1, which was also greatly increased in AML.

The researchers found the 2 proteins are connected, and the connection enables cells to assume the characteristics of highly proliferative leukemia cells.

These experiments involved genetically altering hematopoietic progenitor cells to have high MPP1 and ABCC4 levels. The cells were grown in culture and then replated to see if they would continue to grow, as such self-renewal is a hallmark of leukemia cells.

The researchers found that serial regrowth depended on the cells having high levels of both ABCC4 and MPP1.

“Typically, if you take normal progenitors and you replate, you could do that one time, maybe twice,” Dr Schuetz said. “But our big surprise was that overexpressing MPP1—analogous to what you would see in leukemia—allows those progenitors to self-renew, to be replated over and over, to form new colonies.”

The experiments also revealed that MPP1 and ABCC4 functioned at the cell membrane, where they could play a role in the machinery that would rid the leukemia cells of chemotherapy drugs.

“When we disrupted their interaction, ABCC4 moved off the membrane and the cells became more sensitive to drugs used in AML—drugs that are pumped out of the cell by ABCC4,” Dr Schuetz said.

By screening thousands of compounds, the researchers identified some that could disrupt the ABCC4-MPP1 connection. One, called Antimycin-A, reversed drug resistance in AML cell lines and in cells from AML patients.

Antimycin-A is too toxic to be used in chemotherapy, but the researchers believe identification of the compound should aid the search for other, less-toxic drugs to disrupt the ABCC4-MPP1 interaction.

The team’s findings could also enable clinicians to identify AML patients with high levels of ABCC4 and MPP1. In such patients, drugs that disrupt ABCC4-MPP1 might enhance the effectiveness of standard chemotherapy, Dr Schuetz said.

He also noted that other cancers, including breast and colon cancer and medulloblastoma, show high levels of both ABCC4 and MPP1. Chemotherapy for those cancers might also be enhanced by drugs that disrupt ABCC4-MPP1. ![]()

Researchers say they have uncovered a target to overcome drug resistance in acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

The team discovered how a linkage between 2 proteins enables AML cells to resist chemotherapy and showed that disrupting the linkage could render the cells vulnerable to treatment.

The researchers believe their discovery could lead to drugs to enhance chemotherapy in patients with AML and other cancers.

John Schuetz, PhD, of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, and his colleagues described this research in Nature Communications.

The team launched their experiments based on previous findings that a protein called ABCC4 was greatly elevated in aggressive cases of AML.

Dr Schuetz and his colleagues searched for other proteins that might interact with ABCC4 and enable its function. The team’s screening of candidate proteins yielded one, MPP1, which was also greatly increased in AML.

The researchers found the 2 proteins are connected, and the connection enables cells to assume the characteristics of highly proliferative leukemia cells.

These experiments involved genetically altering hematopoietic progenitor cells to have high MPP1 and ABCC4 levels. The cells were grown in culture and then replated to see if they would continue to grow, as such self-renewal is a hallmark of leukemia cells.

The researchers found that serial regrowth depended on the cells having high levels of both ABCC4 and MPP1.

“Typically, if you take normal progenitors and you replate, you could do that one time, maybe twice,” Dr Schuetz said. “But our big surprise was that overexpressing MPP1—analogous to what you would see in leukemia—allows those progenitors to self-renew, to be replated over and over, to form new colonies.”

The experiments also revealed that MPP1 and ABCC4 functioned at the cell membrane, where they could play a role in the machinery that would rid the leukemia cells of chemotherapy drugs.

“When we disrupted their interaction, ABCC4 moved off the membrane and the cells became more sensitive to drugs used in AML—drugs that are pumped out of the cell by ABCC4,” Dr Schuetz said.

By screening thousands of compounds, the researchers identified some that could disrupt the ABCC4-MPP1 connection. One, called Antimycin-A, reversed drug resistance in AML cell lines and in cells from AML patients.

Antimycin-A is too toxic to be used in chemotherapy, but the researchers believe identification of the compound should aid the search for other, less-toxic drugs to disrupt the ABCC4-MPP1 interaction.

The team’s findings could also enable clinicians to identify AML patients with high levels of ABCC4 and MPP1. In such patients, drugs that disrupt ABCC4-MPP1 might enhance the effectiveness of standard chemotherapy, Dr Schuetz said.

He also noted that other cancers, including breast and colon cancer and medulloblastoma, show high levels of both ABCC4 and MPP1. Chemotherapy for those cancers might also be enhanced by drugs that disrupt ABCC4-MPP1. ![]()

Rigosertib produces better OS in MDS than tAML

Rigosertib has demonstrated activity and tolerability in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia transformed from MDS (tAML), according to researchers.

In a phase 1/2 study, rigosertib produced responses in a quarter of MDS/tAML patients and enabled stable disease in another quarter.

Overall survival (OS) was about a year longer for responders than for non-responders.

MDS patients were more likely to respond to rigosertib and therefore enjoyed longer OS than tAML patients.

Overall, rigosertib was considered well-tolerated. There were no treatment-related deaths, though 18% of patients experienced treatment-related serious adverse events (AEs).

Lewis Silverman, MD, of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, New York, and his colleagues described these results in Leukemia Research.

The study was sponsored by Onconova Therapeutics, Inc., the company developing rigosertib.

Rigosertib is an inhibitor of Ras-effector pathways that interacts with the Ras binding domains common to several signaling proteins, including Raf and PI3 kinase.

Dr Silverman and his colleagues tested intravenous rigosertib in a dose-escalation, phase 1/2 study of 22 patients. Patients had tAML (n=13), high-risk MDS (n=6), intermediate-2-risk MDS (n=2), or chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (n=1).

All patients had relapsed or were refractory to standard therapy and had no approved options for second-line therapies. The patients’ median age was 78 (range, 59-84), and 90% were male.

Patients received 3- to 7-day continuous infusions of rigosertib at doses ranging from 650 mg/m2/day to 1700 mg/m2/day in 14-day cycles.

The mean number of treatment cycles was 5.6 ± 5.8 (range, 1-23). The maximum tolerated dose of rigosertib was 1700 mg/m2/day, and the recommended phase 2 dose was 1375 mg/m2/day.

Safety

All patients had at least 1 AE. The most common AEs of any grade were fatigue (n=16, 73%), diarrhea (n=12, 55%), pyrexia (n=12, 55%), dyspnea (n=11, 50%), insomnia (n=11, 50%), anemia (n=10, 46%), constipation (n=9, 41%), nausea (n=9, 41%), cough (n=9, 41%), and decreased appetite (n=9, 41%).

The most common grade 3 or higher AEs were anemia (n=9, 41%), thrombocytopenia (n=5, 23%), pneumonia (n=5, 23%), hypoglycemia (n=4, 18%), hyponatremia (n=4, 18%), and hypophosphatemia (n=4, 18%).

Four patients (18%) had treatment-related serious AEs. This included hematuria and pollakiuria (n=1), dysuria and pollakiuria (n=1), asthenia (n=1), and dyspnea (n=1). Thirteen patients (59%) stopped treatment due to AEs.

Ten patients, who remained on study from 1 to 19 months, died within 30 days of stopping rigosertib. There were no treatment-related deaths.

Efficacy

Nineteen patients were evaluable for efficacy.

Five patients responded to treatment. Four patients with MDS had a marrow complete response, and 1 with tAML had a marrow partial response. Two of the patients with marrow complete response also had hematologic improvements.

Five patients had stable disease, 3 with MDS and 2 with tAML.

The median OS was 15.7 months for responders and 2.0 months for non-responders (P=0.0070). The median OS was 12.0 months for MDS patients and 2.0 months for tAML patients (P<0.0001).

“The publication of results from this historical study provides support of the relationship between bone marrow blast response and improvement in overall survival in this group of patients with MDS and acute myeloid leukemia for whom no FDA-approved treatments are currently available,” said Ramesh Kumar, president and chief executive officer of Onconova Therapeutics, Inc.

He added that these data are “fundamental to the rationale” of ongoing studies of rigosertib in high-risk MDS patients. ![]()

Rigosertib has demonstrated activity and tolerability in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia transformed from MDS (tAML), according to researchers.

In a phase 1/2 study, rigosertib produced responses in a quarter of MDS/tAML patients and enabled stable disease in another quarter.

Overall survival (OS) was about a year longer for responders than for non-responders.

MDS patients were more likely to respond to rigosertib and therefore enjoyed longer OS than tAML patients.

Overall, rigosertib was considered well-tolerated. There were no treatment-related deaths, though 18% of patients experienced treatment-related serious adverse events (AEs).

Lewis Silverman, MD, of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, New York, and his colleagues described these results in Leukemia Research.

The study was sponsored by Onconova Therapeutics, Inc., the company developing rigosertib.

Rigosertib is an inhibitor of Ras-effector pathways that interacts with the Ras binding domains common to several signaling proteins, including Raf and PI3 kinase.

Dr Silverman and his colleagues tested intravenous rigosertib in a dose-escalation, phase 1/2 study of 22 patients. Patients had tAML (n=13), high-risk MDS (n=6), intermediate-2-risk MDS (n=2), or chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (n=1).

All patients had relapsed or were refractory to standard therapy and had no approved options for second-line therapies. The patients’ median age was 78 (range, 59-84), and 90% were male.

Patients received 3- to 7-day continuous infusions of rigosertib at doses ranging from 650 mg/m2/day to 1700 mg/m2/day in 14-day cycles.

The mean number of treatment cycles was 5.6 ± 5.8 (range, 1-23). The maximum tolerated dose of rigosertib was 1700 mg/m2/day, and the recommended phase 2 dose was 1375 mg/m2/day.

Safety

All patients had at least 1 AE. The most common AEs of any grade were fatigue (n=16, 73%), diarrhea (n=12, 55%), pyrexia (n=12, 55%), dyspnea (n=11, 50%), insomnia (n=11, 50%), anemia (n=10, 46%), constipation (n=9, 41%), nausea (n=9, 41%), cough (n=9, 41%), and decreased appetite (n=9, 41%).

The most common grade 3 or higher AEs were anemia (n=9, 41%), thrombocytopenia (n=5, 23%), pneumonia (n=5, 23%), hypoglycemia (n=4, 18%), hyponatremia (n=4, 18%), and hypophosphatemia (n=4, 18%).

Four patients (18%) had treatment-related serious AEs. This included hematuria and pollakiuria (n=1), dysuria and pollakiuria (n=1), asthenia (n=1), and dyspnea (n=1). Thirteen patients (59%) stopped treatment due to AEs.

Ten patients, who remained on study from 1 to 19 months, died within 30 days of stopping rigosertib. There were no treatment-related deaths.

Efficacy

Nineteen patients were evaluable for efficacy.

Five patients responded to treatment. Four patients with MDS had a marrow complete response, and 1 with tAML had a marrow partial response. Two of the patients with marrow complete response also had hematologic improvements.

Five patients had stable disease, 3 with MDS and 2 with tAML.

The median OS was 15.7 months for responders and 2.0 months for non-responders (P=0.0070). The median OS was 12.0 months for MDS patients and 2.0 months for tAML patients (P<0.0001).

“The publication of results from this historical study provides support of the relationship between bone marrow blast response and improvement in overall survival in this group of patients with MDS and acute myeloid leukemia for whom no FDA-approved treatments are currently available,” said Ramesh Kumar, president and chief executive officer of Onconova Therapeutics, Inc.

He added that these data are “fundamental to the rationale” of ongoing studies of rigosertib in high-risk MDS patients. ![]()

Rigosertib has demonstrated activity and tolerability in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia transformed from MDS (tAML), according to researchers.

In a phase 1/2 study, rigosertib produced responses in a quarter of MDS/tAML patients and enabled stable disease in another quarter.

Overall survival (OS) was about a year longer for responders than for non-responders.

MDS patients were more likely to respond to rigosertib and therefore enjoyed longer OS than tAML patients.

Overall, rigosertib was considered well-tolerated. There were no treatment-related deaths, though 18% of patients experienced treatment-related serious adverse events (AEs).

Lewis Silverman, MD, of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, New York, and his colleagues described these results in Leukemia Research.

The study was sponsored by Onconova Therapeutics, Inc., the company developing rigosertib.

Rigosertib is an inhibitor of Ras-effector pathways that interacts with the Ras binding domains common to several signaling proteins, including Raf and PI3 kinase.

Dr Silverman and his colleagues tested intravenous rigosertib in a dose-escalation, phase 1/2 study of 22 patients. Patients had tAML (n=13), high-risk MDS (n=6), intermediate-2-risk MDS (n=2), or chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (n=1).

All patients had relapsed or were refractory to standard therapy and had no approved options for second-line therapies. The patients’ median age was 78 (range, 59-84), and 90% were male.

Patients received 3- to 7-day continuous infusions of rigosertib at doses ranging from 650 mg/m2/day to 1700 mg/m2/day in 14-day cycles.

The mean number of treatment cycles was 5.6 ± 5.8 (range, 1-23). The maximum tolerated dose of rigosertib was 1700 mg/m2/day, and the recommended phase 2 dose was 1375 mg/m2/day.

Safety

All patients had at least 1 AE. The most common AEs of any grade were fatigue (n=16, 73%), diarrhea (n=12, 55%), pyrexia (n=12, 55%), dyspnea (n=11, 50%), insomnia (n=11, 50%), anemia (n=10, 46%), constipation (n=9, 41%), nausea (n=9, 41%), cough (n=9, 41%), and decreased appetite (n=9, 41%).

The most common grade 3 or higher AEs were anemia (n=9, 41%), thrombocytopenia (n=5, 23%), pneumonia (n=5, 23%), hypoglycemia (n=4, 18%), hyponatremia (n=4, 18%), and hypophosphatemia (n=4, 18%).

Four patients (18%) had treatment-related serious AEs. This included hematuria and pollakiuria (n=1), dysuria and pollakiuria (n=1), asthenia (n=1), and dyspnea (n=1). Thirteen patients (59%) stopped treatment due to AEs.

Ten patients, who remained on study from 1 to 19 months, died within 30 days of stopping rigosertib. There were no treatment-related deaths.

Efficacy

Nineteen patients were evaluable for efficacy.

Five patients responded to treatment. Four patients with MDS had a marrow complete response, and 1 with tAML had a marrow partial response. Two of the patients with marrow complete response also had hematologic improvements.

Five patients had stable disease, 3 with MDS and 2 with tAML.

The median OS was 15.7 months for responders and 2.0 months for non-responders (P=0.0070). The median OS was 12.0 months for MDS patients and 2.0 months for tAML patients (P<0.0001).

“The publication of results from this historical study provides support of the relationship between bone marrow blast response and improvement in overall survival in this group of patients with MDS and acute myeloid leukemia for whom no FDA-approved treatments are currently available,” said Ramesh Kumar, president and chief executive officer of Onconova Therapeutics, Inc.

He added that these data are “fundamental to the rationale” of ongoing studies of rigosertib in high-risk MDS patients. ![]()

FDA approves generic clofarabine

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories Ltd.’s Clofarabine Injection, a therapeutic equivalent generic version of Clolar® (clofarabine) Injection.

The generic drug is now approved to treat patients age 1 to 21 who have relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia and have received at least 2 prior treatment regimens.

Dr. Reddy’s Clofarabine Injection is available in single-dose, 20 mL flint vials containing 20 mg of clofarabine in 20 mL of solution (1 mg/mL). ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories Ltd.’s Clofarabine Injection, a therapeutic equivalent generic version of Clolar® (clofarabine) Injection.

The generic drug is now approved to treat patients age 1 to 21 who have relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia and have received at least 2 prior treatment regimens.

Dr. Reddy’s Clofarabine Injection is available in single-dose, 20 mL flint vials containing 20 mg of clofarabine in 20 mL of solution (1 mg/mL). ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories Ltd.’s Clofarabine Injection, a therapeutic equivalent generic version of Clolar® (clofarabine) Injection.

The generic drug is now approved to treat patients age 1 to 21 who have relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia and have received at least 2 prior treatment regimens.

Dr. Reddy’s Clofarabine Injection is available in single-dose, 20 mL flint vials containing 20 mg of clofarabine in 20 mL of solution (1 mg/mL). ![]()

Generic azacitidine approved in Canada

Health Canada has approved Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories Ltd.’s Azacitidine for Injection 100 mg/vial, a bioequivalent generic version of VIDAZA® (azacitidine for injection).

The generic drug is approved for the same indications as VIDAZA®.

This includes treating adults with intermediate-2 or high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (according to the International Prognostic Scoring System) who are not eligible for hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

It also includes treating adults who have acute myeloid leukemia with 20% to 30% blasts and multi-lineage dysplasia (according to World Health Organization classification) who are not eligible for hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

“The approval and launch of Azacitidine for Injection is an important milestone for Dr. Reddy’s in Canada,” said Vinod Ramachandran, PhD, country manager, Dr. Reddy’s Canada.

“The launch of the first generic azacitidine for injection is another step in our long-term commitment to bring more cost-effective options to Canadian patients.” ![]()

Health Canada has approved Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories Ltd.’s Azacitidine for Injection 100 mg/vial, a bioequivalent generic version of VIDAZA® (azacitidine for injection).

The generic drug is approved for the same indications as VIDAZA®.

This includes treating adults with intermediate-2 or high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (according to the International Prognostic Scoring System) who are not eligible for hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

It also includes treating adults who have acute myeloid leukemia with 20% to 30% blasts and multi-lineage dysplasia (according to World Health Organization classification) who are not eligible for hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

“The approval and launch of Azacitidine for Injection is an important milestone for Dr. Reddy’s in Canada,” said Vinod Ramachandran, PhD, country manager, Dr. Reddy’s Canada.

“The launch of the first generic azacitidine for injection is another step in our long-term commitment to bring more cost-effective options to Canadian patients.” ![]()

Health Canada has approved Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories Ltd.’s Azacitidine for Injection 100 mg/vial, a bioequivalent generic version of VIDAZA® (azacitidine for injection).

The generic drug is approved for the same indications as VIDAZA®.

This includes treating adults with intermediate-2 or high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (according to the International Prognostic Scoring System) who are not eligible for hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

It also includes treating adults who have acute myeloid leukemia with 20% to 30% blasts and multi-lineage dysplasia (according to World Health Organization classification) who are not eligible for hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

“The approval and launch of Azacitidine for Injection is an important milestone for Dr. Reddy’s in Canada,” said Vinod Ramachandran, PhD, country manager, Dr. Reddy’s Canada.

“The launch of the first generic azacitidine for injection is another step in our long-term commitment to bring more cost-effective options to Canadian patients.” ![]()

Cancer patients with TKI-induced hypothyroidism had better survival rates

VICTORIA, B.C. – When it comes to the adverse effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), hypothyroidism appears to have a bright side, according to a retrospective cohort study among patients with nonthyroid cancers.

While taking one of these targeted agents, roughly a quarter of patients became overtly hypothyroid, an adverse effect that appears to be due in part to immune destruction. Risk was higher for women and earlier in therapy.

Relative to counterparts who remained euthyroid, overtly hypothyroid patients were 44% less likely to die after other factors were taken into account.

Hypothyroidism may reflect changes in immune activation, Dr. Angell proposed. “Additional studies may be helpful, both prospectively looking at the clinical importance of this finding [of survival benefit], and also potentially mechanistically, to understand the relationship between hypothyroidism and survival in these patients.”

“This is an innovative study that looked at an interesting clinical question,” observed session cochair Angela M. Leung, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, and an endocrinologist at both UCLA and the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System.

Thyroid dysfunction is a well-known, common side effect of TKI therapy, Dr. Angell noted. “The possible mechanisms that have been suggested for this are direct toxicity on the thyroid gland, destructive thyroiditis, increased thyroid hormone clearance, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibition, among others.”

Some previous research has suggested a possible survival benefit of TKI-induced hypothyroidism. But “there are limitations in our understanding of hypothyroidism in this setting, including the timing of onset, what risk factors there may be, and the effect of additional clinical variables on the survival effect seen,” Dr. Angell pointed out.

He and his coinvestigators studied 538 adult patients with nonthyroid cancers (mostly stage III or IV) who received a first TKI during 2000-2013 and were followed up through 2017. They excluded those who had preexisting thyroid disease or were on thyroid-related medications.

During TKI therapy, 26.7% of patients developed overt hypothyroidism, and another 13.2% developed subclinical hypothyroidism.

“For a given drug, patients were less likely to develop hypothyroidism when they were given it subsequent to another TKI, as opposed to it being the initial TKI,” Dr. Angell reported. But median time to onset of hypothyroidism was about 2.5 months, regardless.

Cumulative months of all TKI exposure during cancer treatment were not significantly associated with development of hypothyroidism.

In a multivariate analysis, patients were significantly more likely to develop hypothyroidism if they were female (odds ratio, 1.99) and significantly less likely if they had a longer total time on treatment (OR, 0.98) or received a non-TKI VEGF inhibitor (OR, 0.43). Age, race, and cumulative TKI exposure did not influence the outcome.

In a second multivariate analysis, patients’ risk of death was significantly lower if they developed overt hypothyroidism (hazard ratio, 0.56; P less than .0001), but not if they developed subclinical hypothyroidism (HR, 0.79; P = .1655).

Treatment of hypothyroidism did not appear to influence survival, according to Dr. Angell. However, “there wasn’t a specific decision on who was treated, how they were treated, [or] when they were treated,” he said. “So, it is difficult within this cohort to look specifically at which cutoff would be ideal” for initiating treatment.

Similarly, thyroid function testing was not standardized in this retrospectively identified cohort, so it was not possible to determine how long patients were hypothyroid and whether that had an impact, according to Dr. Angell.

Dr. Angell had no relevant conflicts of interest.

VICTORIA, B.C. – When it comes to the adverse effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), hypothyroidism appears to have a bright side, according to a retrospective cohort study among patients with nonthyroid cancers.

While taking one of these targeted agents, roughly a quarter of patients became overtly hypothyroid, an adverse effect that appears to be due in part to immune destruction. Risk was higher for women and earlier in therapy.

Relative to counterparts who remained euthyroid, overtly hypothyroid patients were 44% less likely to die after other factors were taken into account.

Hypothyroidism may reflect changes in immune activation, Dr. Angell proposed. “Additional studies may be helpful, both prospectively looking at the clinical importance of this finding [of survival benefit], and also potentially mechanistically, to understand the relationship between hypothyroidism and survival in these patients.”

“This is an innovative study that looked at an interesting clinical question,” observed session cochair Angela M. Leung, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, and an endocrinologist at both UCLA and the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System.

Thyroid dysfunction is a well-known, common side effect of TKI therapy, Dr. Angell noted. “The possible mechanisms that have been suggested for this are direct toxicity on the thyroid gland, destructive thyroiditis, increased thyroid hormone clearance, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibition, among others.”

Some previous research has suggested a possible survival benefit of TKI-induced hypothyroidism. But “there are limitations in our understanding of hypothyroidism in this setting, including the timing of onset, what risk factors there may be, and the effect of additional clinical variables on the survival effect seen,” Dr. Angell pointed out.

He and his coinvestigators studied 538 adult patients with nonthyroid cancers (mostly stage III or IV) who received a first TKI during 2000-2013 and were followed up through 2017. They excluded those who had preexisting thyroid disease or were on thyroid-related medications.

During TKI therapy, 26.7% of patients developed overt hypothyroidism, and another 13.2% developed subclinical hypothyroidism.

“For a given drug, patients were less likely to develop hypothyroidism when they were given it subsequent to another TKI, as opposed to it being the initial TKI,” Dr. Angell reported. But median time to onset of hypothyroidism was about 2.5 months, regardless.

Cumulative months of all TKI exposure during cancer treatment were not significantly associated with development of hypothyroidism.

In a multivariate analysis, patients were significantly more likely to develop hypothyroidism if they were female (odds ratio, 1.99) and significantly less likely if they had a longer total time on treatment (OR, 0.98) or received a non-TKI VEGF inhibitor (OR, 0.43). Age, race, and cumulative TKI exposure did not influence the outcome.

In a second multivariate analysis, patients’ risk of death was significantly lower if they developed overt hypothyroidism (hazard ratio, 0.56; P less than .0001), but not if they developed subclinical hypothyroidism (HR, 0.79; P = .1655).

Treatment of hypothyroidism did not appear to influence survival, according to Dr. Angell. However, “there wasn’t a specific decision on who was treated, how they were treated, [or] when they were treated,” he said. “So, it is difficult within this cohort to look specifically at which cutoff would be ideal” for initiating treatment.

Similarly, thyroid function testing was not standardized in this retrospectively identified cohort, so it was not possible to determine how long patients were hypothyroid and whether that had an impact, according to Dr. Angell.

Dr. Angell had no relevant conflicts of interest.

VICTORIA, B.C. – When it comes to the adverse effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), hypothyroidism appears to have a bright side, according to a retrospective cohort study among patients with nonthyroid cancers.

While taking one of these targeted agents, roughly a quarter of patients became overtly hypothyroid, an adverse effect that appears to be due in part to immune destruction. Risk was higher for women and earlier in therapy.

Relative to counterparts who remained euthyroid, overtly hypothyroid patients were 44% less likely to die after other factors were taken into account.

Hypothyroidism may reflect changes in immune activation, Dr. Angell proposed. “Additional studies may be helpful, both prospectively looking at the clinical importance of this finding [of survival benefit], and also potentially mechanistically, to understand the relationship between hypothyroidism and survival in these patients.”

“This is an innovative study that looked at an interesting clinical question,” observed session cochair Angela M. Leung, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, and an endocrinologist at both UCLA and the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System.

Thyroid dysfunction is a well-known, common side effect of TKI therapy, Dr. Angell noted. “The possible mechanisms that have been suggested for this are direct toxicity on the thyroid gland, destructive thyroiditis, increased thyroid hormone clearance, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibition, among others.”

Some previous research has suggested a possible survival benefit of TKI-induced hypothyroidism. But “there are limitations in our understanding of hypothyroidism in this setting, including the timing of onset, what risk factors there may be, and the effect of additional clinical variables on the survival effect seen,” Dr. Angell pointed out.

He and his coinvestigators studied 538 adult patients with nonthyroid cancers (mostly stage III or IV) who received a first TKI during 2000-2013 and were followed up through 2017. They excluded those who had preexisting thyroid disease or were on thyroid-related medications.

During TKI therapy, 26.7% of patients developed overt hypothyroidism, and another 13.2% developed subclinical hypothyroidism.

“For a given drug, patients were less likely to develop hypothyroidism when they were given it subsequent to another TKI, as opposed to it being the initial TKI,” Dr. Angell reported. But median time to onset of hypothyroidism was about 2.5 months, regardless.

Cumulative months of all TKI exposure during cancer treatment were not significantly associated with development of hypothyroidism.

In a multivariate analysis, patients were significantly more likely to develop hypothyroidism if they were female (odds ratio, 1.99) and significantly less likely if they had a longer total time on treatment (OR, 0.98) or received a non-TKI VEGF inhibitor (OR, 0.43). Age, race, and cumulative TKI exposure did not influence the outcome.

In a second multivariate analysis, patients’ risk of death was significantly lower if they developed overt hypothyroidism (hazard ratio, 0.56; P less than .0001), but not if they developed subclinical hypothyroidism (HR, 0.79; P = .1655).

Treatment of hypothyroidism did not appear to influence survival, according to Dr. Angell. However, “there wasn’t a specific decision on who was treated, how they were treated, [or] when they were treated,” he said. “So, it is difficult within this cohort to look specifically at which cutoff would be ideal” for initiating treatment.

Similarly, thyroid function testing was not standardized in this retrospectively identified cohort, so it was not possible to determine how long patients were hypothyroid and whether that had an impact, according to Dr. Angell.

Dr. Angell had no relevant conflicts of interest.

AT ATA 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Relative to peers who remained euthyroid, patients who developed overt hypothyroidism had a reduced risk of death (HR, 0.56; P less than .0001).

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of 538 adult patients with mainly advanced nonthyroid cancers treated with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Disclosures: Dr. Angell had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Parity laws don’t lower oral cancer drug costs for everyone

US state laws intended to ensure fair prices for oral cancer drugs have had a mixed impact on patients’ pocketbooks, according to a study published in JAMA Oncology.

A total of 43 states and Washington, DC, have enacted parity laws, which require that patients pay no more for an oral cancer treatment than they would for an infusion of the same treatment.

Researchers analyzed the impact of these laws and observed modest improvements in costs for some patients.

However, patients who were already paying the most for their medications saw their monthly costs go up.

“Although parity laws appear to help reduce out-of-pocket spending for some patients, they may not fully address affordability for patients needing cancer drugs,” said study author Stacie B. Dusetzina, PhD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“We need to consider ways to address drug pricing directly and to improve benefit design to make sure that all patients can access prescribed drugs.”

To gauge the impact of parity laws on treatment costs, Dr Dusetzina and her colleagues analyzed health claims data for 63,780 adults from 3 large, nationwide insurance companies before and after the laws were enacted, from 2008 to 2012.

The team compared the cost of filling an oral cancer drug prescription for patients with health insurance plans that were covered by the state laws (fully insured) and patients whose plans were not (self-funded). All patients lived in 1 of 16 states that had passed parity laws at the time of the study.

About half of patients (51.4%) had fully insured plans, and the other half (48.6%) had self-funded plans.

For the entire cohort, the use of oral cancer drugs increased from 18% in the months before parity laws were passed to 22% in the months after (adjusted difference-in-differences risk ratio [aDDRR], 1.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.96-1.13; P=0.34).

The proportion of prescription fills for oral drugs without copayment increased from 15.0% to 53.0% for patients with fully insured plans and from 12.3% to 18.0% in patients with self-funded plans (aDDRR, 2.36; 95% CI, 2.00-2.79; P<0.001).

“From our results, it looks like many plans decided they would just set the co-pay for oral drugs to $0,” Dr Dusetzina said. “Instead of $30 per month, those fills were now $0.”

The proportion of prescription fills with out-of-pocket cost of more than $100 per month increased from 8.4% to 11.1% for patients with fully insured plans but decreased from 12.0% to 11.7% for those with self-funded plans (aDDRR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.11-1.68; P=0.004).

Patients paying the most for their oral cancer drug prescriptions experienced increases in their monthly out-of-pocket costs after parity laws were passed.

For patients whose costs were more expensive than 95% of other patients, their out-of-pocket costs increased an estimated $143.25 per month. Those paying more than 90% of what other patients paid saw their costs increase by $37.19 per month.

“One of the biggest problems with parity laws as they are written is that they don’t address the prices of these medications, which can be very high,” Dr Dusetzina noted.

“Parity can be reached as long as the coverage is the same for both oral and infused cancer therapies. Because we’re now seeing more people insured by plans with high deductibles or plans that require them to pay a percentage of their drug costs, parity may not reduce spending for some patients.”

However, Dr Dusetzina and her colleagues did find that patients who paid the least for their oral cancer treatments saw their estimated monthly out-of-pocket spending decrease.

Patients in the 25th percentile saw an estimated decrease of $19.44 per month, those in the 50th percentile saw a $32.13 decrease, and patients in the 75th percentile saw a decrease of $10.83.

On the other hand, the researchers also found that average 6-month healthcare costs—including what was paid by insurance companies and patients—did not change significantly as a result of parity laws.

The aDDRR was 0.96 (95% CI, 0.90-1.02; P=0.09) for all cancer treatments and 1.06 (95% CI, 0.93-1.20; P=0.40) for oral cancer drugs.

“One of the key arguments against passing parity, both for states that haven’t passed it and for legislation at the federal level, has been that it may increase costs to health plans,” Dr Dusetzina said. “But we didn’t find evidence of that.” ![]()

US state laws intended to ensure fair prices for oral cancer drugs have had a mixed impact on patients’ pocketbooks, according to a study published in JAMA Oncology.

A total of 43 states and Washington, DC, have enacted parity laws, which require that patients pay no more for an oral cancer treatment than they would for an infusion of the same treatment.

Researchers analyzed the impact of these laws and observed modest improvements in costs for some patients.

However, patients who were already paying the most for their medications saw their monthly costs go up.

“Although parity laws appear to help reduce out-of-pocket spending for some patients, they may not fully address affordability for patients needing cancer drugs,” said study author Stacie B. Dusetzina, PhD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“We need to consider ways to address drug pricing directly and to improve benefit design to make sure that all patients can access prescribed drugs.”

To gauge the impact of parity laws on treatment costs, Dr Dusetzina and her colleagues analyzed health claims data for 63,780 adults from 3 large, nationwide insurance companies before and after the laws were enacted, from 2008 to 2012.

The team compared the cost of filling an oral cancer drug prescription for patients with health insurance plans that were covered by the state laws (fully insured) and patients whose plans were not (self-funded). All patients lived in 1 of 16 states that had passed parity laws at the time of the study.

About half of patients (51.4%) had fully insured plans, and the other half (48.6%) had self-funded plans.

For the entire cohort, the use of oral cancer drugs increased from 18% in the months before parity laws were passed to 22% in the months after (adjusted difference-in-differences risk ratio [aDDRR], 1.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.96-1.13; P=0.34).

The proportion of prescription fills for oral drugs without copayment increased from 15.0% to 53.0% for patients with fully insured plans and from 12.3% to 18.0% in patients with self-funded plans (aDDRR, 2.36; 95% CI, 2.00-2.79; P<0.001).

“From our results, it looks like many plans decided they would just set the co-pay for oral drugs to $0,” Dr Dusetzina said. “Instead of $30 per month, those fills were now $0.”

The proportion of prescription fills with out-of-pocket cost of more than $100 per month increased from 8.4% to 11.1% for patients with fully insured plans but decreased from 12.0% to 11.7% for those with self-funded plans (aDDRR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.11-1.68; P=0.004).

Patients paying the most for their oral cancer drug prescriptions experienced increases in their monthly out-of-pocket costs after parity laws were passed.

For patients whose costs were more expensive than 95% of other patients, their out-of-pocket costs increased an estimated $143.25 per month. Those paying more than 90% of what other patients paid saw their costs increase by $37.19 per month.

“One of the biggest problems with parity laws as they are written is that they don’t address the prices of these medications, which can be very high,” Dr Dusetzina noted.

“Parity can be reached as long as the coverage is the same for both oral and infused cancer therapies. Because we’re now seeing more people insured by plans with high deductibles or plans that require them to pay a percentage of their drug costs, parity may not reduce spending for some patients.”

However, Dr Dusetzina and her colleagues did find that patients who paid the least for their oral cancer treatments saw their estimated monthly out-of-pocket spending decrease.

Patients in the 25th percentile saw an estimated decrease of $19.44 per month, those in the 50th percentile saw a $32.13 decrease, and patients in the 75th percentile saw a decrease of $10.83.

On the other hand, the researchers also found that average 6-month healthcare costs—including what was paid by insurance companies and patients—did not change significantly as a result of parity laws.

The aDDRR was 0.96 (95% CI, 0.90-1.02; P=0.09) for all cancer treatments and 1.06 (95% CI, 0.93-1.20; P=0.40) for oral cancer drugs.

“One of the key arguments against passing parity, both for states that haven’t passed it and for legislation at the federal level, has been that it may increase costs to health plans,” Dr Dusetzina said. “But we didn’t find evidence of that.” ![]()

US state laws intended to ensure fair prices for oral cancer drugs have had a mixed impact on patients’ pocketbooks, according to a study published in JAMA Oncology.

A total of 43 states and Washington, DC, have enacted parity laws, which require that patients pay no more for an oral cancer treatment than they would for an infusion of the same treatment.

Researchers analyzed the impact of these laws and observed modest improvements in costs for some patients.

However, patients who were already paying the most for their medications saw their monthly costs go up.

“Although parity laws appear to help reduce out-of-pocket spending for some patients, they may not fully address affordability for patients needing cancer drugs,” said study author Stacie B. Dusetzina, PhD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“We need to consider ways to address drug pricing directly and to improve benefit design to make sure that all patients can access prescribed drugs.”

To gauge the impact of parity laws on treatment costs, Dr Dusetzina and her colleagues analyzed health claims data for 63,780 adults from 3 large, nationwide insurance companies before and after the laws were enacted, from 2008 to 2012.

The team compared the cost of filling an oral cancer drug prescription for patients with health insurance plans that were covered by the state laws (fully insured) and patients whose plans were not (self-funded). All patients lived in 1 of 16 states that had passed parity laws at the time of the study.

About half of patients (51.4%) had fully insured plans, and the other half (48.6%) had self-funded plans.

For the entire cohort, the use of oral cancer drugs increased from 18% in the months before parity laws were passed to 22% in the months after (adjusted difference-in-differences risk ratio [aDDRR], 1.04; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.96-1.13; P=0.34).

The proportion of prescription fills for oral drugs without copayment increased from 15.0% to 53.0% for patients with fully insured plans and from 12.3% to 18.0% in patients with self-funded plans (aDDRR, 2.36; 95% CI, 2.00-2.79; P<0.001).

“From our results, it looks like many plans decided they would just set the co-pay for oral drugs to $0,” Dr Dusetzina said. “Instead of $30 per month, those fills were now $0.”

The proportion of prescription fills with out-of-pocket cost of more than $100 per month increased from 8.4% to 11.1% for patients with fully insured plans but decreased from 12.0% to 11.7% for those with self-funded plans (aDDRR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.11-1.68; P=0.004).

Patients paying the most for their oral cancer drug prescriptions experienced increases in their monthly out-of-pocket costs after parity laws were passed.

For patients whose costs were more expensive than 95% of other patients, their out-of-pocket costs increased an estimated $143.25 per month. Those paying more than 90% of what other patients paid saw their costs increase by $37.19 per month.

“One of the biggest problems with parity laws as they are written is that they don’t address the prices of these medications, which can be very high,” Dr Dusetzina noted.

“Parity can be reached as long as the coverage is the same for both oral and infused cancer therapies. Because we’re now seeing more people insured by plans with high deductibles or plans that require them to pay a percentage of their drug costs, parity may not reduce spending for some patients.”

However, Dr Dusetzina and her colleagues did find that patients who paid the least for their oral cancer treatments saw their estimated monthly out-of-pocket spending decrease.

Patients in the 25th percentile saw an estimated decrease of $19.44 per month, those in the 50th percentile saw a $32.13 decrease, and patients in the 75th percentile saw a decrease of $10.83.

On the other hand, the researchers also found that average 6-month healthcare costs—including what was paid by insurance companies and patients—did not change significantly as a result of parity laws.

The aDDRR was 0.96 (95% CI, 0.90-1.02; P=0.09) for all cancer treatments and 1.06 (95% CI, 0.93-1.20; P=0.40) for oral cancer drugs.

“One of the key arguments against passing parity, both for states that haven’t passed it and for legislation at the federal level, has been that it may increase costs to health plans,” Dr Dusetzina said. “But we didn’t find evidence of that.” ![]()

FDA approves dasatinib for pediatric Ph+ CML

(CML).

The tyrosine kinase inhibitor was approved for the treatment of newly diagnosed adult patients with chronic phase Ph+ CML in 2010.

Median follow-up was 4.5 years for newly diagnosed patients and 5.2 years for patients who were resistant to or intolerant of imatinib, the FDA reported. Because more than half of the responding patients had not progressed at the time of data cutoff, the investigators could not estimate median durations of complete cytogenetic response, major cytogenetic response, and major molecular response.

Adverse reactions to dasatinib included headache, nausea, diarrhea, skin rash, vomiting, pain in extremities, abdominal pain, fatigue, and arthralgia; these side effects were reported in approximately 10% of patients.

Dasatinib is marketed as Sprycel by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

The recommended dose of dasatinib for pediatric patients is based on their body weight. Full prescribing information is available here.

[email protected]

On Twitter @nikolaideslaura

(CML).

The tyrosine kinase inhibitor was approved for the treatment of newly diagnosed adult patients with chronic phase Ph+ CML in 2010.

Median follow-up was 4.5 years for newly diagnosed patients and 5.2 years for patients who were resistant to or intolerant of imatinib, the FDA reported. Because more than half of the responding patients had not progressed at the time of data cutoff, the investigators could not estimate median durations of complete cytogenetic response, major cytogenetic response, and major molecular response.

Adverse reactions to dasatinib included headache, nausea, diarrhea, skin rash, vomiting, pain in extremities, abdominal pain, fatigue, and arthralgia; these side effects were reported in approximately 10% of patients.

Dasatinib is marketed as Sprycel by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

The recommended dose of dasatinib for pediatric patients is based on their body weight. Full prescribing information is available here.

[email protected]

On Twitter @nikolaideslaura

(CML).

The tyrosine kinase inhibitor was approved for the treatment of newly diagnosed adult patients with chronic phase Ph+ CML in 2010.

Median follow-up was 4.5 years for newly diagnosed patients and 5.2 years for patients who were resistant to or intolerant of imatinib, the FDA reported. Because more than half of the responding patients had not progressed at the time of data cutoff, the investigators could not estimate median durations of complete cytogenetic response, major cytogenetic response, and major molecular response.

Adverse reactions to dasatinib included headache, nausea, diarrhea, skin rash, vomiting, pain in extremities, abdominal pain, fatigue, and arthralgia; these side effects were reported in approximately 10% of patients.

Dasatinib is marketed as Sprycel by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

The recommended dose of dasatinib for pediatric patients is based on their body weight. Full prescribing information is available here.

[email protected]

On Twitter @nikolaideslaura

In children with ALL, physical and emotional effects persist

Among children with average-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), those with impairments in physical and emotional functioning at 2 months after diagnosis are likely to have continuing difficulties over 2 years later, based on the results of a 594-patient study published online in Cancer (2017 Nov 7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31085).

Evaluations of quality of life and family functioning as early as 2 months after diagnosis identified those at highest risk of continued impairment, and can be used to target patients and their families for interventions and risk factor modification, the researchers said.

“These results provide a compelling rationale to screen patients for physical and emotional functioning early in therapy to target interventions toward patients at the highest risk of later impairment,” wrote lead author Daniel J. Zheng, MD, of the section of pediatric hematology-oncology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and coauthors.

Dr. Zheng and his colleagues measured impairments in children with average-risk ALL using the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Generic Core Scales Version 4.0 (PedsQL4.0), a 23-item survey that measures a child’s quality of life, and the 12-question General Functioning subscale of the McMaster Family Assessment Device (FAD-GF). Both are quick and low-cost screening measures that can be conducted in the clinic, they added. Evaluations occurred at approximately 2 months, 8 months, 17 months, 26 months, and 38 months (boys only) after diagnosis. The mean age of participants at diagnosis was 6.0 years (standard deviation, 1.6 years).

At 2 months after diagnosis, 36.5% of the children had impairments in physical functioning, and 26.2% had impairments in emotional functioning. The population norms for these measures are 2.3% for both scales, investigators wrote. At a 26-month evaluation, levels of impairment were still 11.9% for physical and 9.8% for emotional functioning.

Boys had an additional 38-month evaluation, at which time there were no significant differences in quality of life outcomes versus those observed at 26 months in the girls.

Unhealthy family functioning was a significant predictor of emotional impairment (odds ratio, 1.5; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.1) in multivariate models controlling for age and sex.

Strategies are needed to “intervene early and help the substantial proportion of children” with quality of life impairments, the researchers said. In particular, family functioning is “potentially modifiable with early intervention,” as suggested by a series of promising studies of techniques such as stress management sessions for parents. Most techniques feature a “targeted family-centered approach to psychosocial needs” that includes “embedded psychologists” as part of the multidisciplinary cancer care team.

Study funding came from the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, and the St. Baldrick’s Foundation. Dr. Zheng reported funding from a Yale Medical Student research fellowship, while coauthors reported conflict of interest disclosures from entities including Amgen, Takeda Pharmaceuticals International, and Shire Pharmaceuticals.

Among children with average-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), those with impairments in physical and emotional functioning at 2 months after diagnosis are likely to have continuing difficulties over 2 years later, based on the results of a 594-patient study published online in Cancer (2017 Nov 7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31085).

Evaluations of quality of life and family functioning as early as 2 months after diagnosis identified those at highest risk of continued impairment, and can be used to target patients and their families for interventions and risk factor modification, the researchers said.

“These results provide a compelling rationale to screen patients for physical and emotional functioning early in therapy to target interventions toward patients at the highest risk of later impairment,” wrote lead author Daniel J. Zheng, MD, of the section of pediatric hematology-oncology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and coauthors.

Dr. Zheng and his colleagues measured impairments in children with average-risk ALL using the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Generic Core Scales Version 4.0 (PedsQL4.0), a 23-item survey that measures a child’s quality of life, and the 12-question General Functioning subscale of the McMaster Family Assessment Device (FAD-GF). Both are quick and low-cost screening measures that can be conducted in the clinic, they added. Evaluations occurred at approximately 2 months, 8 months, 17 months, 26 months, and 38 months (boys only) after diagnosis. The mean age of participants at diagnosis was 6.0 years (standard deviation, 1.6 years).

At 2 months after diagnosis, 36.5% of the children had impairments in physical functioning, and 26.2% had impairments in emotional functioning. The population norms for these measures are 2.3% for both scales, investigators wrote. At a 26-month evaluation, levels of impairment were still 11.9% for physical and 9.8% for emotional functioning.

Boys had an additional 38-month evaluation, at which time there were no significant differences in quality of life outcomes versus those observed at 26 months in the girls.

Unhealthy family functioning was a significant predictor of emotional impairment (odds ratio, 1.5; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-2.1) in multivariate models controlling for age and sex.

Strategies are needed to “intervene early and help the substantial proportion of children” with quality of life impairments, the researchers said. In particular, family functioning is “potentially modifiable with early intervention,” as suggested by a series of promising studies of techniques such as stress management sessions for parents. Most techniques feature a “targeted family-centered approach to psychosocial needs” that includes “embedded psychologists” as part of the multidisciplinary cancer care team.

Study funding came from the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, and the St. Baldrick’s Foundation. Dr. Zheng reported funding from a Yale Medical Student research fellowship, while coauthors reported conflict of interest disclosures from entities including Amgen, Takeda Pharmaceuticals International, and Shire Pharmaceuticals.

Among children with average-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), those with impairments in physical and emotional functioning at 2 months after diagnosis are likely to have continuing difficulties over 2 years later, based on the results of a 594-patient study published online in Cancer (2017 Nov 7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31085).

Evaluations of quality of life and family functioning as early as 2 months after diagnosis identified those at highest risk of continued impairment, and can be used to target patients and their families for interventions and risk factor modification, the researchers said.

“These results provide a compelling rationale to screen patients for physical and emotional functioning early in therapy to target interventions toward patients at the highest risk of later impairment,” wrote lead author Daniel J. Zheng, MD, of the section of pediatric hematology-oncology at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and coauthors.

Dr. Zheng and his colleagues measured impairments in children with average-risk ALL using the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Generic Core Scales Version 4.0 (PedsQL4.0), a 23-item survey that measures a child’s quality of life, and the 12-question General Functioning subscale of the McMaster Family Assessment Device (FAD-GF). Both are quick and low-cost screening measures that can be conducted in the clinic, they added. Evaluations occurred at approximately 2 months, 8 months, 17 months, 26 months, and 38 months (boys only) after diagnosis. The mean age of participants at diagnosis was 6.0 years (standard deviation, 1.6 years).