User login

Repeat FIB-4 blood tests help predict cirrhosis

Repeat Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) scores can be used to identify people at greatest risk for cirrhosis of the liver, new research shows.

“Done repeatedly, this test can improve prediction capacity to identify who will develop cirrhosis of the liver later in life,” said lead researcher Hannes Hagström, MD, from the Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm.

A FIB-4 score that rises from one test to the next indicates that a person is at increased risk for severe liver disease, whereas a score that drops indicates a decreased risk, he told Medscape Medical News. The study results — published online July 1 in the Journal of Hepatology, was presented at the Digital International Liver Congress 2020.

The noninvasive, widely available, cheap FIB-4 test — which is calculated on the basis of age, transaminase level, and platelet count — is commonly used to identify the risk for advanced fibrosis in liver disease, but it has not been used to predict future risk.

To evaluate risk for cirrhosis, Hagström and his colleagues looked at 812,073 blood tests performed from 1985 to 1996 on people enrolled in the Swedish Apolipoprotein Mortality Risk (AMORIS) study.

They excluded people younger than 35 years and older than 79 years and anyone with a diagnosis of any liver disease at baseline.

The 40,729 people who had two FIB-4 measurements taken less than 5 years apart were included in the analysis. Test results were categorized into three risk groups: low (<1.30), intermediate (1.30 - 2.67), and high (>2.67).

After a median of 16.2 years, 11,929 people in the study cohort had died and 581 had a severe liver disease event.

Severe liver disease events were more common in people who had both tests categorized as high risk than in people who had both tests categorized as low risk (13.2% vs 1.0%; aHR, 17.04; 95% CI, 11.67 - 24.88).

The researchers found that a one-unit increase between the two test results was continuously predictive of a severe liver disease event (aHR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.67 - 1.96).

One test not enough

The absolute risk for severe liver disease in the general population is 2%, but the FIB-4 score is elevated in about one-third of people in the general population.

“A lot of people who have increased levels of this biomarker will never develop cirrhosis,” Hagström told Medscape Medical News.

Although two FIB-4 scores might not identify everyone who will get cirrhosis, comparing scores provides insight into who is at greatest risk, he explained.

This information can be useful, particularly for primary care doctors. If you know that someone is at higher risk, “you can send that patient for a FibroScan, which is a much more sensitive measurement,” but also much more expensive. “Now we can better know who to send,” he said.

However, “the main problem is that these tests are not widely known” or used enough by primary care doctors, Hagström said.

A lack of knowledge about the utility of this test is a problem, agreed Jérôme Boursier, MD, PhD, from Angers University in France.

“The younger doctors are using these tests more often,” he told Medscape Medical News, but “the older doctors are not aware they exist.”

This study supports repeating the tests. “One test offers quite poor prediction,” Boursier said. But “when you have a higher score on a second one, this can help the conversation with the patient.”

Hagström and Boursier have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Repeat Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) scores can be used to identify people at greatest risk for cirrhosis of the liver, new research shows.

“Done repeatedly, this test can improve prediction capacity to identify who will develop cirrhosis of the liver later in life,” said lead researcher Hannes Hagström, MD, from the Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm.

A FIB-4 score that rises from one test to the next indicates that a person is at increased risk for severe liver disease, whereas a score that drops indicates a decreased risk, he told Medscape Medical News. The study results — published online July 1 in the Journal of Hepatology, was presented at the Digital International Liver Congress 2020.

The noninvasive, widely available, cheap FIB-4 test — which is calculated on the basis of age, transaminase level, and platelet count — is commonly used to identify the risk for advanced fibrosis in liver disease, but it has not been used to predict future risk.

To evaluate risk for cirrhosis, Hagström and his colleagues looked at 812,073 blood tests performed from 1985 to 1996 on people enrolled in the Swedish Apolipoprotein Mortality Risk (AMORIS) study.

They excluded people younger than 35 years and older than 79 years and anyone with a diagnosis of any liver disease at baseline.

The 40,729 people who had two FIB-4 measurements taken less than 5 years apart were included in the analysis. Test results were categorized into three risk groups: low (<1.30), intermediate (1.30 - 2.67), and high (>2.67).

After a median of 16.2 years, 11,929 people in the study cohort had died and 581 had a severe liver disease event.

Severe liver disease events were more common in people who had both tests categorized as high risk than in people who had both tests categorized as low risk (13.2% vs 1.0%; aHR, 17.04; 95% CI, 11.67 - 24.88).

The researchers found that a one-unit increase between the two test results was continuously predictive of a severe liver disease event (aHR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.67 - 1.96).

One test not enough

The absolute risk for severe liver disease in the general population is 2%, but the FIB-4 score is elevated in about one-third of people in the general population.

“A lot of people who have increased levels of this biomarker will never develop cirrhosis,” Hagström told Medscape Medical News.

Although two FIB-4 scores might not identify everyone who will get cirrhosis, comparing scores provides insight into who is at greatest risk, he explained.

This information can be useful, particularly for primary care doctors. If you know that someone is at higher risk, “you can send that patient for a FibroScan, which is a much more sensitive measurement,” but also much more expensive. “Now we can better know who to send,” he said.

However, “the main problem is that these tests are not widely known” or used enough by primary care doctors, Hagström said.

A lack of knowledge about the utility of this test is a problem, agreed Jérôme Boursier, MD, PhD, from Angers University in France.

“The younger doctors are using these tests more often,” he told Medscape Medical News, but “the older doctors are not aware they exist.”

This study supports repeating the tests. “One test offers quite poor prediction,” Boursier said. But “when you have a higher score on a second one, this can help the conversation with the patient.”

Hagström and Boursier have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Repeat Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) scores can be used to identify people at greatest risk for cirrhosis of the liver, new research shows.

“Done repeatedly, this test can improve prediction capacity to identify who will develop cirrhosis of the liver later in life,” said lead researcher Hannes Hagström, MD, from the Karolinska University Hospital in Stockholm.

A FIB-4 score that rises from one test to the next indicates that a person is at increased risk for severe liver disease, whereas a score that drops indicates a decreased risk, he told Medscape Medical News. The study results — published online July 1 in the Journal of Hepatology, was presented at the Digital International Liver Congress 2020.

The noninvasive, widely available, cheap FIB-4 test — which is calculated on the basis of age, transaminase level, and platelet count — is commonly used to identify the risk for advanced fibrosis in liver disease, but it has not been used to predict future risk.

To evaluate risk for cirrhosis, Hagström and his colleagues looked at 812,073 blood tests performed from 1985 to 1996 on people enrolled in the Swedish Apolipoprotein Mortality Risk (AMORIS) study.

They excluded people younger than 35 years and older than 79 years and anyone with a diagnosis of any liver disease at baseline.

The 40,729 people who had two FIB-4 measurements taken less than 5 years apart were included in the analysis. Test results were categorized into three risk groups: low (<1.30), intermediate (1.30 - 2.67), and high (>2.67).

After a median of 16.2 years, 11,929 people in the study cohort had died and 581 had a severe liver disease event.

Severe liver disease events were more common in people who had both tests categorized as high risk than in people who had both tests categorized as low risk (13.2% vs 1.0%; aHR, 17.04; 95% CI, 11.67 - 24.88).

The researchers found that a one-unit increase between the two test results was continuously predictive of a severe liver disease event (aHR, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.67 - 1.96).

One test not enough

The absolute risk for severe liver disease in the general population is 2%, but the FIB-4 score is elevated in about one-third of people in the general population.

“A lot of people who have increased levels of this biomarker will never develop cirrhosis,” Hagström told Medscape Medical News.

Although two FIB-4 scores might not identify everyone who will get cirrhosis, comparing scores provides insight into who is at greatest risk, he explained.

This information can be useful, particularly for primary care doctors. If you know that someone is at higher risk, “you can send that patient for a FibroScan, which is a much more sensitive measurement,” but also much more expensive. “Now we can better know who to send,” he said.

However, “the main problem is that these tests are not widely known” or used enough by primary care doctors, Hagström said.

A lack of knowledge about the utility of this test is a problem, agreed Jérôme Boursier, MD, PhD, from Angers University in France.

“The younger doctors are using these tests more often,” he told Medscape Medical News, but “the older doctors are not aware they exist.”

This study supports repeating the tests. “One test offers quite poor prediction,” Boursier said. But “when you have a higher score on a second one, this can help the conversation with the patient.”

Hagström and Boursier have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fecal transplant shows promise in reducing alcohol craving

Fecal microbiota transplantation results in a short-term reduction in alcohol craving in patients with alcohol-induced cirrhosis who can’t stop drinking, results from a new study show.

And that reduction could lead to a better psychosocial quality of life for patients with cirrhosis and alcohol use disorder, said investigator Jasmohan Bajaj, MD, from Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond.

“This is the most common addiction disorder worldwide, but we have nothing to treat these patients with,” he said.

Cirrhosis is associated with an altered gut-brain axis. It leads to organ damage in several parts of the body, including the brain, gut, pancreas, and liver. This makes changing the gut microbes “an attractive target,” Dr. Bajaj said at the Digital International Liver Congress 2020.

For their phase 1, double-blind study, he and his colleagues assessed 20 men from a Virginia veteran’s hospital with untreatable alcohol use disorder who were not eligible for liver transplantation.

All had failed behavioral or pharmacologic therapy and were unwilling to try again. “That’s what made them good candidates to try something new,” Dr. Bajaj said during a press briefing.

Mean age in the study cohort was 65 years, mean Model for End-Stage Liver disease score was 8.9, and demographic characteristics were similar between the 10 men randomly assigned to fecal transplantation and the 10 assigned to placebo. One man in each group dropped out of the study.

The investigators evaluated cravings, microbiota, and quality of life during the 30-day study period.

At day 15, significantly more men in the transplant group than in the placebo group experienced a reduction in alcohol cravings (90% vs. 30%).

At 30 days, levels of creatinine, serum interleukin-6, and lipopolysaccharide-binding protein were lower in the transplant group than in the placebo group. In addition, levels of butyrate and isobutyrate increased, as did cognition and quality of life scores.

There was also a decrease in urinary ethyl glucuronide in the transplant group, which “is the objective criteria for alcohol intake,” Dr. Bajaj reported, noting that there was no change in ethyl glucuronide in the placebo group.

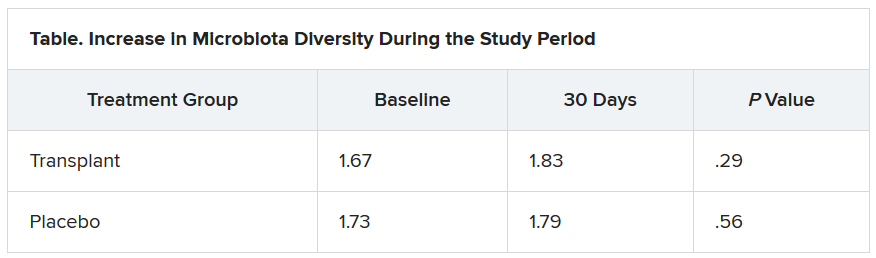

The increase in microbiota diversity was significant in the transplant group but not in the placebo group. Alistipes, Odoribacter, and Roseburia were more abundant in the transplant group than in the placebo group.

During the 30-day study period, two men in the placebo group required medical attention, one for hyponatremia and the other for atrial fibrillation. However, no adverse events were seen in any men in the transplant group. “This was the No. 1 result,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Liver disease and the microbiome

“Understanding of interactions between the human and microbiome genome [metagenome] in health and disease has represented one of the major areas of progress in the last few years,” said Luca Valenti, MD, from the University of Milan, who is a member of the scientific committee of the European Association the Study of the Liver, which organized the congress.

“These studies lay the groundwork for the exploitation of this new knowledge for the treatment of liver disease,” he said.

“We are [now] diagnosing liver disease and the stages of liver disease based on microbiome changes,” said Jonel Trebicka, MD, PhD, from University Hospital Frankfurt (Germany), who chaired a session at the congress on the role of the microbiome in liver disease.

“This and other studies have shown us that the microbiome itself may influence liver disease,” he added.

Dr. Bajaj is considered one of the world’s experts on cirrhosis and the microbiome, Dr. Trebicka explained. Last year, Dr. Bajaj and his team demonstrated that fecal microbiota transplantation can reduce the incidence of recurrent hepatic encephalopathy, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

The current study also “shows clearly that the microbiome plays a role in craving. FMT reduces the desire for alcohol,” said Dr. Trebicka.

“The way to the brain is through the gut,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Dr. Bajaj, Dr. Trebicka, and Dr. Valenti disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fecal microbiota transplantation results in a short-term reduction in alcohol craving in patients with alcohol-induced cirrhosis who can’t stop drinking, results from a new study show.

And that reduction could lead to a better psychosocial quality of life for patients with cirrhosis and alcohol use disorder, said investigator Jasmohan Bajaj, MD, from Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond.

“This is the most common addiction disorder worldwide, but we have nothing to treat these patients with,” he said.

Cirrhosis is associated with an altered gut-brain axis. It leads to organ damage in several parts of the body, including the brain, gut, pancreas, and liver. This makes changing the gut microbes “an attractive target,” Dr. Bajaj said at the Digital International Liver Congress 2020.

For their phase 1, double-blind study, he and his colleagues assessed 20 men from a Virginia veteran’s hospital with untreatable alcohol use disorder who were not eligible for liver transplantation.

All had failed behavioral or pharmacologic therapy and were unwilling to try again. “That’s what made them good candidates to try something new,” Dr. Bajaj said during a press briefing.

Mean age in the study cohort was 65 years, mean Model for End-Stage Liver disease score was 8.9, and demographic characteristics were similar between the 10 men randomly assigned to fecal transplantation and the 10 assigned to placebo. One man in each group dropped out of the study.

The investigators evaluated cravings, microbiota, and quality of life during the 30-day study period.

At day 15, significantly more men in the transplant group than in the placebo group experienced a reduction in alcohol cravings (90% vs. 30%).

At 30 days, levels of creatinine, serum interleukin-6, and lipopolysaccharide-binding protein were lower in the transplant group than in the placebo group. In addition, levels of butyrate and isobutyrate increased, as did cognition and quality of life scores.

There was also a decrease in urinary ethyl glucuronide in the transplant group, which “is the objective criteria for alcohol intake,” Dr. Bajaj reported, noting that there was no change in ethyl glucuronide in the placebo group.

The increase in microbiota diversity was significant in the transplant group but not in the placebo group. Alistipes, Odoribacter, and Roseburia were more abundant in the transplant group than in the placebo group.

During the 30-day study period, two men in the placebo group required medical attention, one for hyponatremia and the other for atrial fibrillation. However, no adverse events were seen in any men in the transplant group. “This was the No. 1 result,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Liver disease and the microbiome

“Understanding of interactions between the human and microbiome genome [metagenome] in health and disease has represented one of the major areas of progress in the last few years,” said Luca Valenti, MD, from the University of Milan, who is a member of the scientific committee of the European Association the Study of the Liver, which organized the congress.

“These studies lay the groundwork for the exploitation of this new knowledge for the treatment of liver disease,” he said.

“We are [now] diagnosing liver disease and the stages of liver disease based on microbiome changes,” said Jonel Trebicka, MD, PhD, from University Hospital Frankfurt (Germany), who chaired a session at the congress on the role of the microbiome in liver disease.

“This and other studies have shown us that the microbiome itself may influence liver disease,” he added.

Dr. Bajaj is considered one of the world’s experts on cirrhosis and the microbiome, Dr. Trebicka explained. Last year, Dr. Bajaj and his team demonstrated that fecal microbiota transplantation can reduce the incidence of recurrent hepatic encephalopathy, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

The current study also “shows clearly that the microbiome plays a role in craving. FMT reduces the desire for alcohol,” said Dr. Trebicka.

“The way to the brain is through the gut,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Dr. Bajaj, Dr. Trebicka, and Dr. Valenti disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fecal microbiota transplantation results in a short-term reduction in alcohol craving in patients with alcohol-induced cirrhosis who can’t stop drinking, results from a new study show.

And that reduction could lead to a better psychosocial quality of life for patients with cirrhosis and alcohol use disorder, said investigator Jasmohan Bajaj, MD, from Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond.

“This is the most common addiction disorder worldwide, but we have nothing to treat these patients with,” he said.

Cirrhosis is associated with an altered gut-brain axis. It leads to organ damage in several parts of the body, including the brain, gut, pancreas, and liver. This makes changing the gut microbes “an attractive target,” Dr. Bajaj said at the Digital International Liver Congress 2020.

For their phase 1, double-blind study, he and his colleagues assessed 20 men from a Virginia veteran’s hospital with untreatable alcohol use disorder who were not eligible for liver transplantation.

All had failed behavioral or pharmacologic therapy and were unwilling to try again. “That’s what made them good candidates to try something new,” Dr. Bajaj said during a press briefing.

Mean age in the study cohort was 65 years, mean Model for End-Stage Liver disease score was 8.9, and demographic characteristics were similar between the 10 men randomly assigned to fecal transplantation and the 10 assigned to placebo. One man in each group dropped out of the study.

The investigators evaluated cravings, microbiota, and quality of life during the 30-day study period.

At day 15, significantly more men in the transplant group than in the placebo group experienced a reduction in alcohol cravings (90% vs. 30%).

At 30 days, levels of creatinine, serum interleukin-6, and lipopolysaccharide-binding protein were lower in the transplant group than in the placebo group. In addition, levels of butyrate and isobutyrate increased, as did cognition and quality of life scores.

There was also a decrease in urinary ethyl glucuronide in the transplant group, which “is the objective criteria for alcohol intake,” Dr. Bajaj reported, noting that there was no change in ethyl glucuronide in the placebo group.

The increase in microbiota diversity was significant in the transplant group but not in the placebo group. Alistipes, Odoribacter, and Roseburia were more abundant in the transplant group than in the placebo group.

During the 30-day study period, two men in the placebo group required medical attention, one for hyponatremia and the other for atrial fibrillation. However, no adverse events were seen in any men in the transplant group. “This was the No. 1 result,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Liver disease and the microbiome

“Understanding of interactions between the human and microbiome genome [metagenome] in health and disease has represented one of the major areas of progress in the last few years,” said Luca Valenti, MD, from the University of Milan, who is a member of the scientific committee of the European Association the Study of the Liver, which organized the congress.

“These studies lay the groundwork for the exploitation of this new knowledge for the treatment of liver disease,” he said.

“We are [now] diagnosing liver disease and the stages of liver disease based on microbiome changes,” said Jonel Trebicka, MD, PhD, from University Hospital Frankfurt (Germany), who chaired a session at the congress on the role of the microbiome in liver disease.

“This and other studies have shown us that the microbiome itself may influence liver disease,” he added.

Dr. Bajaj is considered one of the world’s experts on cirrhosis and the microbiome, Dr. Trebicka explained. Last year, Dr. Bajaj and his team demonstrated that fecal microbiota transplantation can reduce the incidence of recurrent hepatic encephalopathy, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

The current study also “shows clearly that the microbiome plays a role in craving. FMT reduces the desire for alcohol,” said Dr. Trebicka.

“The way to the brain is through the gut,” Dr. Bajaj said.

Dr. Bajaj, Dr. Trebicka, and Dr. Valenti disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

NAFLD may predict arrhythmia recurrence post-AFib ablation

Increasingly recognized as an independent risk factor for new-onset atrial fibrillation (AFib), new research suggests for the first time that nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) also confers a higher risk for arrhythmia recurrence after AFib ablation.

Over 29 months of postablation follow-up, 56% of patients with NAFLD suffered bouts of arrhythmia, compared with 31% of patients without NAFLD, matched on the basis of age, sex, body mass index (BMI), ejection fraction within 5%, and AFib type (P < .0001).

The presence of NAFLD was an independent predictor of arrhythmia recurrence in multivariable analyses adjusted for several confounders, including hemoglobin A1c, BMI, and AFib type (hazard ratio, 3.0; 95% confidence interval, 1.94-4.68).

The association is concerning given that one in four adults in the United States has NAFLD, and up to 6.1 million Americans are estimated to have Afib. Previous studies, such as ARREST-AF and LEGACY, however, have demonstrated the benefits of aggressive preablation cardiometabolic risk factor modification on long-term AFib ablation success.

Indeed, none of the NAFLD patients in the present study who lost at least 10% of their body weight had recurrent arrhythmia, compared with 31% who lost less than 10%, and 91% who gained weight prior to ablation (P < .0001).

All 22 patients whose A1c increased during the 12 months prior to ablation had recurrent arrhythmia, compared with 36% of patients whose A1c improved (P < .0001).

“I don’t think the findings of the study were particularly surprising, given what we know. It’s just further reinforcement of the essential role of risk-factor modification,” lead author Eoin Donnellan, MD, Cleveland Clinic, said in an interview.

The results were published Augus 12 in JACC Clinical Electrophysiology.

For the study, the researchers examined data from 267 consecutive patients with a mean BMI of 32.7 kg/m2 who underwent radiofrequency ablation (98%) or cryoablation (2%) at the Cleveland Clinic between January 2013 and December 2017.

All patients were followed for at least 12 months after ablation and had scheduled clinic visits at 3, 6, and 12 months after pulmonary vein isolation, and annually thereafter.

NAFLD was diagnosed in 89 patients prior to ablation on the basis of CT imaging and abdominal ultrasound or MRI. On the basis of NAFLD-Fibrosis Score (NAFLD-FS), 13 patients had a low probability of liver fibrosis (F0-F2), 54 had an indeterminate probability, and 22 a high probability of fibrosis (F3-F4).

Compared with patients with no or early fibrosis (F0-F2), patients with advanced liver fibrosis (F3-F4) had almost a threefold increase in AFib recurrence (82% vs. 31%; P = .003).

“Cardiologists should make an effort to risk-stratify NAFLD patients either by NAFLD-FS or [an] alternative option, such as transient elastography or MR elastography, given these observations, rather than viewing it as either present or absence [sic] and involve expert multidisciplinary team care early in the clinical course of NAFLD patients with evidence of advanced fibrosis,” Dr. Donnellan and colleagues wrote.

Coauthor Thomas G. Cotter, MD, department of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Chicago, said in an interview that cardiologists could use just the NAFLD-FS as part of an algorithm for an AFib.

“Because if it shows low risk, then it’s very, very likely the patient will be fine,” he said. “To use more advanced noninvasive testing, there are subtleties in the interpretation that would require referral to a liver doctor or a gastroenterologist and the cost of referring might bulk up the costs. But the NAFLD-FS is freely available and is a validated tool.”

Although it hasn’t specifically been validated in patients with AFib, the NAFLD-FS has been shown to correlate with the development of coronary artery disease (CAD) and was recommended for clinical use in U.S. multisociety guidelines for NAFLD.

The score is calculated using six readily available clinical variables (age, BMI, hyperglycemia or diabetes, AST/ALT, platelets, and albumin). It does not include family history or alcohol consumption, which should be carefully detailed given the large overlap between NAFLD and alcohol-related liver disease, Dr. Cotter observed.

Of note, the study excluded patients with alcohol consumption of more than 30 g/day in men and more than 20 g/day in women, chronic viral hepatitis, Wilson’s disease, and hereditary hemochromatosis.

Finally, CT imaging revealed that epicardial fat volume (EFV) was greater in patients with NAFLD than in those without NAFLD (248 vs. 223 mL; P = .01).

Although increased amounts of epicardial fat have been associated with CAD, there was no significant difference in EFV between patients who did and did not develop recurrent arrhythmia (238 vs. 229 mL; P = .5). Nor was EFV associated with arrhythmia recurrence on Cox proportional hazards analysis (HR, 1.001; P = .17).

“We hypothesized that the increased risk of arrhythmia recurrence may be mediated in part by an increased epicardial fat volume,” Dr. Donnellan said. “The existing literature exploring the link between epicardial fat volume and A[Fib] burden and recurrence is conflicting. But in both this study and our bariatric surgery study, epicardial fat volume was not a significant predictor of arrhythmia recurrence on multivariable analysis.”

It’s likely that the increased recurrence risk is caused by several mechanisms, including NAFLD’s deleterious impact on cardiac structure and function, the bidirectional relationship between NAFLD and sleep apnea, and transcription of proinflammatory cytokines and low-grade systemic inflammation, he suggested.

“Patients with NAFLD represent a particularly high-risk population for arrhythmia recurrence. NAFLD is a reversible disease, and a multidisciplinary approach incorporating dietary and lifestyle interventions should by instituted prior to ablation,” Dr. Donnellan and colleagues concluded.

They noted that serial abdominal imaging to assess for preablation changes in NAFLD was limited in patients and that only 56% of control subjects underwent dedicated abdominal imaging to rule out hepatic steatosis. Also, the heterogeneity of imaging modalities used to diagnose NAFLD may have influenced the results and the study’s single-center, retrospective design limits their generalizability.

The authors reported having no relevant financial relationships.

Help your patients better understand their risk of NASH and NAFLD by sharing AGA patient education content at http://ow.ly/ZKi930r50am.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Increasingly recognized as an independent risk factor for new-onset atrial fibrillation (AFib), new research suggests for the first time that nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) also confers a higher risk for arrhythmia recurrence after AFib ablation.

Over 29 months of postablation follow-up, 56% of patients with NAFLD suffered bouts of arrhythmia, compared with 31% of patients without NAFLD, matched on the basis of age, sex, body mass index (BMI), ejection fraction within 5%, and AFib type (P < .0001).

The presence of NAFLD was an independent predictor of arrhythmia recurrence in multivariable analyses adjusted for several confounders, including hemoglobin A1c, BMI, and AFib type (hazard ratio, 3.0; 95% confidence interval, 1.94-4.68).

The association is concerning given that one in four adults in the United States has NAFLD, and up to 6.1 million Americans are estimated to have Afib. Previous studies, such as ARREST-AF and LEGACY, however, have demonstrated the benefits of aggressive preablation cardiometabolic risk factor modification on long-term AFib ablation success.

Indeed, none of the NAFLD patients in the present study who lost at least 10% of their body weight had recurrent arrhythmia, compared with 31% who lost less than 10%, and 91% who gained weight prior to ablation (P < .0001).

All 22 patients whose A1c increased during the 12 months prior to ablation had recurrent arrhythmia, compared with 36% of patients whose A1c improved (P < .0001).

“I don’t think the findings of the study were particularly surprising, given what we know. It’s just further reinforcement of the essential role of risk-factor modification,” lead author Eoin Donnellan, MD, Cleveland Clinic, said in an interview.

The results were published Augus 12 in JACC Clinical Electrophysiology.

For the study, the researchers examined data from 267 consecutive patients with a mean BMI of 32.7 kg/m2 who underwent radiofrequency ablation (98%) or cryoablation (2%) at the Cleveland Clinic between January 2013 and December 2017.

All patients were followed for at least 12 months after ablation and had scheduled clinic visits at 3, 6, and 12 months after pulmonary vein isolation, and annually thereafter.

NAFLD was diagnosed in 89 patients prior to ablation on the basis of CT imaging and abdominal ultrasound or MRI. On the basis of NAFLD-Fibrosis Score (NAFLD-FS), 13 patients had a low probability of liver fibrosis (F0-F2), 54 had an indeterminate probability, and 22 a high probability of fibrosis (F3-F4).

Compared with patients with no or early fibrosis (F0-F2), patients with advanced liver fibrosis (F3-F4) had almost a threefold increase in AFib recurrence (82% vs. 31%; P = .003).

“Cardiologists should make an effort to risk-stratify NAFLD patients either by NAFLD-FS or [an] alternative option, such as transient elastography or MR elastography, given these observations, rather than viewing it as either present or absence [sic] and involve expert multidisciplinary team care early in the clinical course of NAFLD patients with evidence of advanced fibrosis,” Dr. Donnellan and colleagues wrote.

Coauthor Thomas G. Cotter, MD, department of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Chicago, said in an interview that cardiologists could use just the NAFLD-FS as part of an algorithm for an AFib.

“Because if it shows low risk, then it’s very, very likely the patient will be fine,” he said. “To use more advanced noninvasive testing, there are subtleties in the interpretation that would require referral to a liver doctor or a gastroenterologist and the cost of referring might bulk up the costs. But the NAFLD-FS is freely available and is a validated tool.”

Although it hasn’t specifically been validated in patients with AFib, the NAFLD-FS has been shown to correlate with the development of coronary artery disease (CAD) and was recommended for clinical use in U.S. multisociety guidelines for NAFLD.

The score is calculated using six readily available clinical variables (age, BMI, hyperglycemia or diabetes, AST/ALT, platelets, and albumin). It does not include family history or alcohol consumption, which should be carefully detailed given the large overlap between NAFLD and alcohol-related liver disease, Dr. Cotter observed.

Of note, the study excluded patients with alcohol consumption of more than 30 g/day in men and more than 20 g/day in women, chronic viral hepatitis, Wilson’s disease, and hereditary hemochromatosis.

Finally, CT imaging revealed that epicardial fat volume (EFV) was greater in patients with NAFLD than in those without NAFLD (248 vs. 223 mL; P = .01).

Although increased amounts of epicardial fat have been associated with CAD, there was no significant difference in EFV between patients who did and did not develop recurrent arrhythmia (238 vs. 229 mL; P = .5). Nor was EFV associated with arrhythmia recurrence on Cox proportional hazards analysis (HR, 1.001; P = .17).

“We hypothesized that the increased risk of arrhythmia recurrence may be mediated in part by an increased epicardial fat volume,” Dr. Donnellan said. “The existing literature exploring the link between epicardial fat volume and A[Fib] burden and recurrence is conflicting. But in both this study and our bariatric surgery study, epicardial fat volume was not a significant predictor of arrhythmia recurrence on multivariable analysis.”

It’s likely that the increased recurrence risk is caused by several mechanisms, including NAFLD’s deleterious impact on cardiac structure and function, the bidirectional relationship between NAFLD and sleep apnea, and transcription of proinflammatory cytokines and low-grade systemic inflammation, he suggested.

“Patients with NAFLD represent a particularly high-risk population for arrhythmia recurrence. NAFLD is a reversible disease, and a multidisciplinary approach incorporating dietary and lifestyle interventions should by instituted prior to ablation,” Dr. Donnellan and colleagues concluded.

They noted that serial abdominal imaging to assess for preablation changes in NAFLD was limited in patients and that only 56% of control subjects underwent dedicated abdominal imaging to rule out hepatic steatosis. Also, the heterogeneity of imaging modalities used to diagnose NAFLD may have influenced the results and the study’s single-center, retrospective design limits their generalizability.

The authors reported having no relevant financial relationships.

Help your patients better understand their risk of NASH and NAFLD by sharing AGA patient education content at http://ow.ly/ZKi930r50am.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Increasingly recognized as an independent risk factor for new-onset atrial fibrillation (AFib), new research suggests for the first time that nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) also confers a higher risk for arrhythmia recurrence after AFib ablation.

Over 29 months of postablation follow-up, 56% of patients with NAFLD suffered bouts of arrhythmia, compared with 31% of patients without NAFLD, matched on the basis of age, sex, body mass index (BMI), ejection fraction within 5%, and AFib type (P < .0001).

The presence of NAFLD was an independent predictor of arrhythmia recurrence in multivariable analyses adjusted for several confounders, including hemoglobin A1c, BMI, and AFib type (hazard ratio, 3.0; 95% confidence interval, 1.94-4.68).

The association is concerning given that one in four adults in the United States has NAFLD, and up to 6.1 million Americans are estimated to have Afib. Previous studies, such as ARREST-AF and LEGACY, however, have demonstrated the benefits of aggressive preablation cardiometabolic risk factor modification on long-term AFib ablation success.

Indeed, none of the NAFLD patients in the present study who lost at least 10% of their body weight had recurrent arrhythmia, compared with 31% who lost less than 10%, and 91% who gained weight prior to ablation (P < .0001).

All 22 patients whose A1c increased during the 12 months prior to ablation had recurrent arrhythmia, compared with 36% of patients whose A1c improved (P < .0001).

“I don’t think the findings of the study were particularly surprising, given what we know. It’s just further reinforcement of the essential role of risk-factor modification,” lead author Eoin Donnellan, MD, Cleveland Clinic, said in an interview.

The results were published Augus 12 in JACC Clinical Electrophysiology.

For the study, the researchers examined data from 267 consecutive patients with a mean BMI of 32.7 kg/m2 who underwent radiofrequency ablation (98%) or cryoablation (2%) at the Cleveland Clinic between January 2013 and December 2017.

All patients were followed for at least 12 months after ablation and had scheduled clinic visits at 3, 6, and 12 months after pulmonary vein isolation, and annually thereafter.

NAFLD was diagnosed in 89 patients prior to ablation on the basis of CT imaging and abdominal ultrasound or MRI. On the basis of NAFLD-Fibrosis Score (NAFLD-FS), 13 patients had a low probability of liver fibrosis (F0-F2), 54 had an indeterminate probability, and 22 a high probability of fibrosis (F3-F4).

Compared with patients with no or early fibrosis (F0-F2), patients with advanced liver fibrosis (F3-F4) had almost a threefold increase in AFib recurrence (82% vs. 31%; P = .003).

“Cardiologists should make an effort to risk-stratify NAFLD patients either by NAFLD-FS or [an] alternative option, such as transient elastography or MR elastography, given these observations, rather than viewing it as either present or absence [sic] and involve expert multidisciplinary team care early in the clinical course of NAFLD patients with evidence of advanced fibrosis,” Dr. Donnellan and colleagues wrote.

Coauthor Thomas G. Cotter, MD, department of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Chicago, said in an interview that cardiologists could use just the NAFLD-FS as part of an algorithm for an AFib.

“Because if it shows low risk, then it’s very, very likely the patient will be fine,” he said. “To use more advanced noninvasive testing, there are subtleties in the interpretation that would require referral to a liver doctor or a gastroenterologist and the cost of referring might bulk up the costs. But the NAFLD-FS is freely available and is a validated tool.”

Although it hasn’t specifically been validated in patients with AFib, the NAFLD-FS has been shown to correlate with the development of coronary artery disease (CAD) and was recommended for clinical use in U.S. multisociety guidelines for NAFLD.

The score is calculated using six readily available clinical variables (age, BMI, hyperglycemia or diabetes, AST/ALT, platelets, and albumin). It does not include family history or alcohol consumption, which should be carefully detailed given the large overlap between NAFLD and alcohol-related liver disease, Dr. Cotter observed.

Of note, the study excluded patients with alcohol consumption of more than 30 g/day in men and more than 20 g/day in women, chronic viral hepatitis, Wilson’s disease, and hereditary hemochromatosis.

Finally, CT imaging revealed that epicardial fat volume (EFV) was greater in patients with NAFLD than in those without NAFLD (248 vs. 223 mL; P = .01).

Although increased amounts of epicardial fat have been associated with CAD, there was no significant difference in EFV between patients who did and did not develop recurrent arrhythmia (238 vs. 229 mL; P = .5). Nor was EFV associated with arrhythmia recurrence on Cox proportional hazards analysis (HR, 1.001; P = .17).

“We hypothesized that the increased risk of arrhythmia recurrence may be mediated in part by an increased epicardial fat volume,” Dr. Donnellan said. “The existing literature exploring the link between epicardial fat volume and A[Fib] burden and recurrence is conflicting. But in both this study and our bariatric surgery study, epicardial fat volume was not a significant predictor of arrhythmia recurrence on multivariable analysis.”

It’s likely that the increased recurrence risk is caused by several mechanisms, including NAFLD’s deleterious impact on cardiac structure and function, the bidirectional relationship between NAFLD and sleep apnea, and transcription of proinflammatory cytokines and low-grade systemic inflammation, he suggested.

“Patients with NAFLD represent a particularly high-risk population for arrhythmia recurrence. NAFLD is a reversible disease, and a multidisciplinary approach incorporating dietary and lifestyle interventions should by instituted prior to ablation,” Dr. Donnellan and colleagues concluded.

They noted that serial abdominal imaging to assess for preablation changes in NAFLD was limited in patients and that only 56% of control subjects underwent dedicated abdominal imaging to rule out hepatic steatosis. Also, the heterogeneity of imaging modalities used to diagnose NAFLD may have influenced the results and the study’s single-center, retrospective design limits their generalizability.

The authors reported having no relevant financial relationships.

Help your patients better understand their risk of NASH and NAFLD by sharing AGA patient education content at http://ow.ly/ZKi930r50am.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Hepatitis screening now for all patients with cancer on therapy

All patients with cancer who are candidates for systemic anticancer therapy should be screened for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection prior to or at the start of therapy, according to an updated provisional clinical opinion (PCO) from the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

“This is a new approach [that] will actively take system changes ... but it will ultimately be safer for patients – and that is crucial,” commented Jessica P. Hwang, MD, MPH, cochair of the American Society of Clinical Oncology HBV Screening Expert Panel and the first author of the PCO.

Uptake of this universal screening approach would streamline testing protocols and identify more patients at risk for HBV reactivation who should receive prophylactic antiviral therapy, Dr. Hwang said in an interview.

The PCO calls for antiviral prophylaxis during and for at least 12 months after therapy for those with chronic HBV infection who are receiving any systemic anticancer treatment and for those with have had HBV in the past and are receiving any therapies that pose a risk for HBV reactivation.

“Hepatitis B reactivation can cause really terrible outcomes, like organ failure and even death,” Dr. Hwang, who is also a professor at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, commented in an interview.

“This whole [issue of] reactivation and adverse outcomes with anticancer therapies is completely preventable with good planning, good communication, comanagement with specialists, and antiviral therapy and monitoring,” she added.

The updated opinion was published online July 27 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

It was developed in response to new data that call into question the previously recommended risk-adaptive approach to HBV screening of cancer patients, say the authors.

ASCO PCOs are developed “to provide timely clinical guidance” on the basis of emerging practice-changing information. This is the second update to follow the initial HBV screening PCO, published in 2010. In the absence of clear consensus because of limited data, the original PCO called for a risk-based approach to screening. A 2015 update extended the recommendation for screening to patients starting anti-CD20 therapy or who are to undergo stem cell transplant and to those with risk factors for HBV exposure.

The current update provides “a clinically pragmatic approach to HBV screening and management” that is based on the latest findings, say the authors. These include findings from a multicenter prospective cohort study of more than 3000 patients. In that study, 21% of patients with chronic HBV had no known risk factors for the infection. In another large prospective observational cohort study, led by Dr. Hwang, which included more than 2100 patients with cancer, 90% had one or more significant risk factors for HBV infection, making selective screening “inefficient and impractical,” she said.

“The results of these two studies suggest that a universal screening approach, its potential harms (e.g., patient and clinician anxiety about management, financial burden associated with antiviral therapy) notwithstanding, is the most efficient, clinically pragmatic approach to HBV screening in persons anticipating systemic anticancer treatment,” the authors comment.

The screening recommended in the PCO requires three tests: hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), core antibody total immunoglobulin or IgG, and antibody to HBsAg tests.

Anticancer therapy should not be delayed pending the results, they write.

Planning for monitoring and long-term prophylaxis for chronic HBV infection should involve a clinician experienced in HBV management, the authors write. Management of those with past infection should be individualized. Alternatively, patients with past infection can be carefully monitored rather than given prophylactic treatment, as long as frequent and consistent follow-up is possible to allow for rapid initiation of antiviral therapy in the event of reactivation, they say.

Hormonal therapy without systemic anticancer therapy is not likely to lead to HBV reactivation in patients with chronic or past infection; antiviral therapy and management of these patients should follow relevant national HBV guidelines, they note.

Challenges in implementing universal HBV screening

The expert panel acknowledges the challenges associated with implementation of universal HBV screening as recommended in their report and notes that electronic health record–based approaches that use alerts to prompt screening have demonstrated success. In one study of high-risk primary care patients, an EHR alert system significantly increased testing rates (odds ratio, 2.64 in comparison with a control group without alerts), and another study that used a simple “sticky-note” alert system to promote referral of HBsAg patients to hepatologists increased referrals from 28% to 73%.

In a cancer population, a “comprehensive set of multimodal interventions,” including pharmacy staff checks for screening prior to anti-CD20 therapy administration and electronic medication order reviews to assess for appropriate testing and treatment before anti-CD20 therapy, increased testing rates to greater than 90% and antiviral prophylaxis rates to more than 80%.

A study of 965 patients in Taiwan showed that a computer-assisted reminder system that prompted for testing prior to ordering anticancer therapy increased screening from 8% to 86% but was less effective for improving the rates of antiviral prophylaxis for those who tested positive for HBV, particularly among physicians treating patients with nonhematologic malignancies.

“Future studies will be needed to make universal HBV screening and linkage to care efficient and systematic, likely based in EHR systems,” the panel says. The authors note that “[o]ngoing studies of HBV tests such as ultrasensitive HBsAg, HBV RNA, and hepatitis B core antigen are being studied and may be useful in predicting risk of HBV reactivation.”

The panel also identified a research gap related to HBV reactivation risks “for the growing list of agents that deplete or modulate B cells.” It notes a need for additional research on the cost-effectiveness of HBV screening. The results of prior cost analyses have been inconsistent and vary with respect to the population studied. For example, universal screening and antiviral prophylaxis approaches have been shown to be cost-effective for patients with hematologic malignancies and high HBV reactivation risk but are less so for patients with solid tumors and lower reactivation risk, they explain.

Dr. Hwang said that not one of the more than 2100 patients in her HBV screening cohort study encountered problems with receiving insurance payment for their HBV screening.

“That’s a really strong statement that insurance payers are accepting of this kind of preventative service,” she said.

Expert panel cochair Andrew Artz, MD, commented that there is now greater acceptance of the need for HBV screening across medical specialties.

“There’s growing consensus among hepatologists, infectious disease specialists, oncologists, and HBV specialists that we need to do a better job of finding patients with hepatitis B [who are] about to receive immunocompromising treatment,” Dr. Artz said in an interview.

Dr. Artz is director of the Program for Aging and Blood Cancers and deputy director of the Center for Cancer and Aging at City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center, Duarte, California.

He suggested that the growing acceptance is due in part to the increasing number of anticancer therapies available and the resulting increase in the likelihood of patients receiving therapies that could cause reactivation.

More therapies – and more lines of therapy – could mean greater risk, he explained. He said that testing is easy and that universal screening is the simplest approach to determining who needs it. “There’s no question we will have to change practice,” Dr. Artz said in an interview. “But this is easier than the previous approach that essentially wasn’t being followed because it was too difficult to follow and patients were being missed.”

Most clinicians will appreciate having an approach that’s easier to follow, Dr. Artz predicted.

If there’s a challenge it will be in developing partnerships with HBV specialists, particularly in rural areas. In areas where there is a paucity of subspecialists, oncologists will have to “take some ownership of the issue,” as they often do in such settings, he said.

However, with support from pharmacists, administrators, and others in embracing this guidance, implementation can take place at a systems level rather than an individual clinician level, he added.

The recommendations in this updated PCO were all rated as “strong,” with the exception of the recommendation on hormonal therapy in the absence of systemic anticancer therapy, which was rated as “moderate.” All were based on “informal consensus,” with the exception of the key recommendation for universal HBV screening – use of three specific tests – which was “evidence based.”

The expert panel agreed that the benefits outweigh the harms for each recommendation in the update.

Dr. Hwang received research funding to her institution from Gilead Sciences and Merck Sharp & Dohme. She also has a relationship with the Asian Health Foundation. Dr. Artz received research funding from Miltenyi Biotec. All expert panel members’ disclosures are available in the PCO update.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

All patients with cancer who are candidates for systemic anticancer therapy should be screened for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection prior to or at the start of therapy, according to an updated provisional clinical opinion (PCO) from the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

“This is a new approach [that] will actively take system changes ... but it will ultimately be safer for patients – and that is crucial,” commented Jessica P. Hwang, MD, MPH, cochair of the American Society of Clinical Oncology HBV Screening Expert Panel and the first author of the PCO.

Uptake of this universal screening approach would streamline testing protocols and identify more patients at risk for HBV reactivation who should receive prophylactic antiviral therapy, Dr. Hwang said in an interview.

The PCO calls for antiviral prophylaxis during and for at least 12 months after therapy for those with chronic HBV infection who are receiving any systemic anticancer treatment and for those with have had HBV in the past and are receiving any therapies that pose a risk for HBV reactivation.

“Hepatitis B reactivation can cause really terrible outcomes, like organ failure and even death,” Dr. Hwang, who is also a professor at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, commented in an interview.

“This whole [issue of] reactivation and adverse outcomes with anticancer therapies is completely preventable with good planning, good communication, comanagement with specialists, and antiviral therapy and monitoring,” she added.

The updated opinion was published online July 27 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

It was developed in response to new data that call into question the previously recommended risk-adaptive approach to HBV screening of cancer patients, say the authors.

ASCO PCOs are developed “to provide timely clinical guidance” on the basis of emerging practice-changing information. This is the second update to follow the initial HBV screening PCO, published in 2010. In the absence of clear consensus because of limited data, the original PCO called for a risk-based approach to screening. A 2015 update extended the recommendation for screening to patients starting anti-CD20 therapy or who are to undergo stem cell transplant and to those with risk factors for HBV exposure.

The current update provides “a clinically pragmatic approach to HBV screening and management” that is based on the latest findings, say the authors. These include findings from a multicenter prospective cohort study of more than 3000 patients. In that study, 21% of patients with chronic HBV had no known risk factors for the infection. In another large prospective observational cohort study, led by Dr. Hwang, which included more than 2100 patients with cancer, 90% had one or more significant risk factors for HBV infection, making selective screening “inefficient and impractical,” she said.

“The results of these two studies suggest that a universal screening approach, its potential harms (e.g., patient and clinician anxiety about management, financial burden associated with antiviral therapy) notwithstanding, is the most efficient, clinically pragmatic approach to HBV screening in persons anticipating systemic anticancer treatment,” the authors comment.

The screening recommended in the PCO requires three tests: hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), core antibody total immunoglobulin or IgG, and antibody to HBsAg tests.

Anticancer therapy should not be delayed pending the results, they write.

Planning for monitoring and long-term prophylaxis for chronic HBV infection should involve a clinician experienced in HBV management, the authors write. Management of those with past infection should be individualized. Alternatively, patients with past infection can be carefully monitored rather than given prophylactic treatment, as long as frequent and consistent follow-up is possible to allow for rapid initiation of antiviral therapy in the event of reactivation, they say.

Hormonal therapy without systemic anticancer therapy is not likely to lead to HBV reactivation in patients with chronic or past infection; antiviral therapy and management of these patients should follow relevant national HBV guidelines, they note.

Challenges in implementing universal HBV screening

The expert panel acknowledges the challenges associated with implementation of universal HBV screening as recommended in their report and notes that electronic health record–based approaches that use alerts to prompt screening have demonstrated success. In one study of high-risk primary care patients, an EHR alert system significantly increased testing rates (odds ratio, 2.64 in comparison with a control group without alerts), and another study that used a simple “sticky-note” alert system to promote referral of HBsAg patients to hepatologists increased referrals from 28% to 73%.

In a cancer population, a “comprehensive set of multimodal interventions,” including pharmacy staff checks for screening prior to anti-CD20 therapy administration and electronic medication order reviews to assess for appropriate testing and treatment before anti-CD20 therapy, increased testing rates to greater than 90% and antiviral prophylaxis rates to more than 80%.

A study of 965 patients in Taiwan showed that a computer-assisted reminder system that prompted for testing prior to ordering anticancer therapy increased screening from 8% to 86% but was less effective for improving the rates of antiviral prophylaxis for those who tested positive for HBV, particularly among physicians treating patients with nonhematologic malignancies.

“Future studies will be needed to make universal HBV screening and linkage to care efficient and systematic, likely based in EHR systems,” the panel says. The authors note that “[o]ngoing studies of HBV tests such as ultrasensitive HBsAg, HBV RNA, and hepatitis B core antigen are being studied and may be useful in predicting risk of HBV reactivation.”

The panel also identified a research gap related to HBV reactivation risks “for the growing list of agents that deplete or modulate B cells.” It notes a need for additional research on the cost-effectiveness of HBV screening. The results of prior cost analyses have been inconsistent and vary with respect to the population studied. For example, universal screening and antiviral prophylaxis approaches have been shown to be cost-effective for patients with hematologic malignancies and high HBV reactivation risk but are less so for patients with solid tumors and lower reactivation risk, they explain.

Dr. Hwang said that not one of the more than 2100 patients in her HBV screening cohort study encountered problems with receiving insurance payment for their HBV screening.

“That’s a really strong statement that insurance payers are accepting of this kind of preventative service,” she said.

Expert panel cochair Andrew Artz, MD, commented that there is now greater acceptance of the need for HBV screening across medical specialties.

“There’s growing consensus among hepatologists, infectious disease specialists, oncologists, and HBV specialists that we need to do a better job of finding patients with hepatitis B [who are] about to receive immunocompromising treatment,” Dr. Artz said in an interview.

Dr. Artz is director of the Program for Aging and Blood Cancers and deputy director of the Center for Cancer and Aging at City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center, Duarte, California.

He suggested that the growing acceptance is due in part to the increasing number of anticancer therapies available and the resulting increase in the likelihood of patients receiving therapies that could cause reactivation.

More therapies – and more lines of therapy – could mean greater risk, he explained. He said that testing is easy and that universal screening is the simplest approach to determining who needs it. “There’s no question we will have to change practice,” Dr. Artz said in an interview. “But this is easier than the previous approach that essentially wasn’t being followed because it was too difficult to follow and patients were being missed.”

Most clinicians will appreciate having an approach that’s easier to follow, Dr. Artz predicted.

If there’s a challenge it will be in developing partnerships with HBV specialists, particularly in rural areas. In areas where there is a paucity of subspecialists, oncologists will have to “take some ownership of the issue,” as they often do in such settings, he said.

However, with support from pharmacists, administrators, and others in embracing this guidance, implementation can take place at a systems level rather than an individual clinician level, he added.

The recommendations in this updated PCO were all rated as “strong,” with the exception of the recommendation on hormonal therapy in the absence of systemic anticancer therapy, which was rated as “moderate.” All were based on “informal consensus,” with the exception of the key recommendation for universal HBV screening – use of three specific tests – which was “evidence based.”

The expert panel agreed that the benefits outweigh the harms for each recommendation in the update.

Dr. Hwang received research funding to her institution from Gilead Sciences and Merck Sharp & Dohme. She also has a relationship with the Asian Health Foundation. Dr. Artz received research funding from Miltenyi Biotec. All expert panel members’ disclosures are available in the PCO update.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

All patients with cancer who are candidates for systemic anticancer therapy should be screened for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection prior to or at the start of therapy, according to an updated provisional clinical opinion (PCO) from the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

“This is a new approach [that] will actively take system changes ... but it will ultimately be safer for patients – and that is crucial,” commented Jessica P. Hwang, MD, MPH, cochair of the American Society of Clinical Oncology HBV Screening Expert Panel and the first author of the PCO.

Uptake of this universal screening approach would streamline testing protocols and identify more patients at risk for HBV reactivation who should receive prophylactic antiviral therapy, Dr. Hwang said in an interview.

The PCO calls for antiviral prophylaxis during and for at least 12 months after therapy for those with chronic HBV infection who are receiving any systemic anticancer treatment and for those with have had HBV in the past and are receiving any therapies that pose a risk for HBV reactivation.

“Hepatitis B reactivation can cause really terrible outcomes, like organ failure and even death,” Dr. Hwang, who is also a professor at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, commented in an interview.

“This whole [issue of] reactivation and adverse outcomes with anticancer therapies is completely preventable with good planning, good communication, comanagement with specialists, and antiviral therapy and monitoring,” she added.

The updated opinion was published online July 27 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

It was developed in response to new data that call into question the previously recommended risk-adaptive approach to HBV screening of cancer patients, say the authors.

ASCO PCOs are developed “to provide timely clinical guidance” on the basis of emerging practice-changing information. This is the second update to follow the initial HBV screening PCO, published in 2010. In the absence of clear consensus because of limited data, the original PCO called for a risk-based approach to screening. A 2015 update extended the recommendation for screening to patients starting anti-CD20 therapy or who are to undergo stem cell transplant and to those with risk factors for HBV exposure.

The current update provides “a clinically pragmatic approach to HBV screening and management” that is based on the latest findings, say the authors. These include findings from a multicenter prospective cohort study of more than 3000 patients. In that study, 21% of patients with chronic HBV had no known risk factors for the infection. In another large prospective observational cohort study, led by Dr. Hwang, which included more than 2100 patients with cancer, 90% had one or more significant risk factors for HBV infection, making selective screening “inefficient and impractical,” she said.

“The results of these two studies suggest that a universal screening approach, its potential harms (e.g., patient and clinician anxiety about management, financial burden associated with antiviral therapy) notwithstanding, is the most efficient, clinically pragmatic approach to HBV screening in persons anticipating systemic anticancer treatment,” the authors comment.

The screening recommended in the PCO requires three tests: hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), core antibody total immunoglobulin or IgG, and antibody to HBsAg tests.

Anticancer therapy should not be delayed pending the results, they write.

Planning for monitoring and long-term prophylaxis for chronic HBV infection should involve a clinician experienced in HBV management, the authors write. Management of those with past infection should be individualized. Alternatively, patients with past infection can be carefully monitored rather than given prophylactic treatment, as long as frequent and consistent follow-up is possible to allow for rapid initiation of antiviral therapy in the event of reactivation, they say.

Hormonal therapy without systemic anticancer therapy is not likely to lead to HBV reactivation in patients with chronic or past infection; antiviral therapy and management of these patients should follow relevant national HBV guidelines, they note.

Challenges in implementing universal HBV screening

The expert panel acknowledges the challenges associated with implementation of universal HBV screening as recommended in their report and notes that electronic health record–based approaches that use alerts to prompt screening have demonstrated success. In one study of high-risk primary care patients, an EHR alert system significantly increased testing rates (odds ratio, 2.64 in comparison with a control group without alerts), and another study that used a simple “sticky-note” alert system to promote referral of HBsAg patients to hepatologists increased referrals from 28% to 73%.

In a cancer population, a “comprehensive set of multimodal interventions,” including pharmacy staff checks for screening prior to anti-CD20 therapy administration and electronic medication order reviews to assess for appropriate testing and treatment before anti-CD20 therapy, increased testing rates to greater than 90% and antiviral prophylaxis rates to more than 80%.

A study of 965 patients in Taiwan showed that a computer-assisted reminder system that prompted for testing prior to ordering anticancer therapy increased screening from 8% to 86% but was less effective for improving the rates of antiviral prophylaxis for those who tested positive for HBV, particularly among physicians treating patients with nonhematologic malignancies.

“Future studies will be needed to make universal HBV screening and linkage to care efficient and systematic, likely based in EHR systems,” the panel says. The authors note that “[o]ngoing studies of HBV tests such as ultrasensitive HBsAg, HBV RNA, and hepatitis B core antigen are being studied and may be useful in predicting risk of HBV reactivation.”

The panel also identified a research gap related to HBV reactivation risks “for the growing list of agents that deplete or modulate B cells.” It notes a need for additional research on the cost-effectiveness of HBV screening. The results of prior cost analyses have been inconsistent and vary with respect to the population studied. For example, universal screening and antiviral prophylaxis approaches have been shown to be cost-effective for patients with hematologic malignancies and high HBV reactivation risk but are less so for patients with solid tumors and lower reactivation risk, they explain.

Dr. Hwang said that not one of the more than 2100 patients in her HBV screening cohort study encountered problems with receiving insurance payment for their HBV screening.

“That’s a really strong statement that insurance payers are accepting of this kind of preventative service,” she said.

Expert panel cochair Andrew Artz, MD, commented that there is now greater acceptance of the need for HBV screening across medical specialties.

“There’s growing consensus among hepatologists, infectious disease specialists, oncologists, and HBV specialists that we need to do a better job of finding patients with hepatitis B [who are] about to receive immunocompromising treatment,” Dr. Artz said in an interview.

Dr. Artz is director of the Program for Aging and Blood Cancers and deputy director of the Center for Cancer and Aging at City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center, Duarte, California.

He suggested that the growing acceptance is due in part to the increasing number of anticancer therapies available and the resulting increase in the likelihood of patients receiving therapies that could cause reactivation.

More therapies – and more lines of therapy – could mean greater risk, he explained. He said that testing is easy and that universal screening is the simplest approach to determining who needs it. “There’s no question we will have to change practice,” Dr. Artz said in an interview. “But this is easier than the previous approach that essentially wasn’t being followed because it was too difficult to follow and patients were being missed.”

Most clinicians will appreciate having an approach that’s easier to follow, Dr. Artz predicted.

If there’s a challenge it will be in developing partnerships with HBV specialists, particularly in rural areas. In areas where there is a paucity of subspecialists, oncologists will have to “take some ownership of the issue,” as they often do in such settings, he said.

However, with support from pharmacists, administrators, and others in embracing this guidance, implementation can take place at a systems level rather than an individual clinician level, he added.

The recommendations in this updated PCO were all rated as “strong,” with the exception of the recommendation on hormonal therapy in the absence of systemic anticancer therapy, which was rated as “moderate.” All were based on “informal consensus,” with the exception of the key recommendation for universal HBV screening – use of three specific tests – which was “evidence based.”

The expert panel agreed that the benefits outweigh the harms for each recommendation in the update.

Dr. Hwang received research funding to her institution from Gilead Sciences and Merck Sharp & Dohme. She also has a relationship with the Asian Health Foundation. Dr. Artz received research funding from Miltenyi Biotec. All expert panel members’ disclosures are available in the PCO update.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Study finds no link between platelet count, surgery bleed risk in cirrhosis

The findings raise questions about current recommendations that call for transfusing platelet concentrates to reduce bleeding risk during surgery in cirrhosis patients with extremely low platelet counts, Gian Marco Podda, MD, PhD, said at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis virtual congress.

The overall rate of perioperative bleeding was 8.9% in 996 patients who underwent excision of hepatocellular carcinoma by resection (42%) or radiofrequency ablation (58%) without platelet transfusion between 1998 and 2018. The rates were slightly higher among 65 patients with platelet count of fewer than 50 × 109/L indicating severe thrombocytopenia, and in 292 patients with counts of 50-100 × 109/L, indicating moderate thrombocytopenia (10.8% and 10.2%, respectively), compared with those with a platelet count of higher than 100 × 109/L (8.1%), but the differences were not statistically significant, said Dr. Podda of the University of Milan (Italy).

The corresponding rates among those who underwent radiofrequency ablation were 8.6%, 5.9%, and 5%, and among those who underwent resection, they were 18.8%, 17.7%, and 15.9%.

On multivariate analysis, factors associated with an increased incidence of major bleeding were low hemoglobin level (odds ratio, 0.57), age over 65 years (OR, 1.19), aspartate aminotransferase level greater than twice the upper limit of normal (OR, 2.12), hepatitis B or C cirrhosis versus cryptogenic cirrhosis (OR, 0.08), and resection versus radiofrequency ablation (OR, 3.74), he noted. Logistic regression analysis showed no significant association between platelet count and major bleeding events.

Mortality, a secondary outcome measure, was significantly higher among those with moderate or severe thrombocytopenia (rate of 5.5% for each), compared with those with mild or no thrombocytopenia (2.4%), Dr. Podda said.

Factors associated with mortality on multivariate analysis were severe liver dysfunction as demonstrated by Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score of 10 or greater versus less than 10 (OR, 3.13) and Child-Pugh B and C score versus Child-Pugh A score (OR, 16.72), advanced tumor status as measured by Barcelona-Clínic Liver Cancer staging greater than A4 versus A1 (OR, 5.78), major bleeding (OR, 4.59), and resection versus radiofrequency ablation (OR, 3.31).

“Low platelet count was associated with an increased risk of mortality at 3 months. However, this association disappeared at the multivariate analysis, which took into account markers of severity of liver cirrhosis,” he said.

Dr. Podda and his colleagues conducted the study in light of a recommendation from a consensus conference of the Italian Association for the Study of Liver Disease and the Italian Society of Internal Medicine that called for increasing platelet count by platelet transfusions in patients with cirrhosis who undergo an invasive procedure and who have a platelet count lower than 50 × 109/L.

“This recommendation mostly stemmed from consideration of biological plausibility prospects rather than being based on hard experimental evidence,” he explained, noting that such severe thrombocytopenia affects about 10% of patients with liver cirrhosis.

Based on the findings of this study, the practice is not supported, he concluded.

Dr. Podda reported honoraria from Sanofi, Boehringer Ingelheim.

SOURCE: Ronca V et al. ISTH 2020, Abstract OC 13.4.

The findings raise questions about current recommendations that call for transfusing platelet concentrates to reduce bleeding risk during surgery in cirrhosis patients with extremely low platelet counts, Gian Marco Podda, MD, PhD, said at the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis virtual congress.

The overall rate of perioperative bleeding was 8.9% in 996 patients who underwent excision of hepatocellular carcinoma by resection (42%) or radiofrequency ablation (58%) without platelet transfusion between 1998 and 2018. The rates were slightly higher among 65 patients with platelet count of fewer than 50 × 109/L indicating severe thrombocytopenia, and in 292 patients with counts of 50-100 × 109/L, indicating moderate thrombocytopenia (10.8% and 10.2%, respectively), compared with those with a platelet count of higher than 100 × 109/L (8.1%), but the differences were not statistically significant, said Dr. Podda of the University of Milan (Italy).

The corresponding rates among those who underwent radiofrequency ablation were 8.6%, 5.9%, and 5%, and among those who underwent resection, they were 18.8%, 17.7%, and 15.9%.

On multivariate analysis, factors associated with an increased incidence of major bleeding were low hemoglobin level (odds ratio, 0.57), age over 65 years (OR, 1.19), aspartate aminotransferase level greater than twice the upper limit of normal (OR, 2.12), hepatitis B or C cirrhosis versus cryptogenic cirrhosis (OR, 0.08), and resection versus radiofrequency ablation (OR, 3.74), he noted. Logistic regression analysis showed no significant association between platelet count and major bleeding events.

Mortality, a secondary outcome measure, was significantly higher among those with moderate or severe thrombocytopenia (rate of 5.5% for each), compared with those with mild or no thrombocytopenia (2.4%), Dr. Podda said.

Factors associated with mortality on multivariate analysis were severe liver dysfunction as demonstrated by Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score of 10 or greater versus less than 10 (OR, 3.13) and Child-Pugh B and C score versus Child-Pugh A score (OR, 16.72), advanced tumor status as measured by Barcelona-Clínic Liver Cancer staging greater than A4 versus A1 (OR, 5.78), major bleeding (OR, 4.59), and resection versus radiofrequency ablation (OR, 3.31).

“Low platelet count was associated with an increased risk of mortality at 3 months. However, this association disappeared at the multivariate analysis, which took into account markers of severity of liver cirrhosis,” he said.