User login

Three-month history of fever

This patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of pleomorphic mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

MCL is a rare, clinically and biologically heterogeneous B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It accounts for approximately 5%-7% of all lymphomas. In North America and Europe, its incidence is akin to that of noncutaneous, peripheral T-cell lymphomas. The typical age at diagnosis is between 60 and 70 years. Approximately 70% of all cases are seen in men.

Little is known about risk factors for the development of MCL. Factors that have been associated with the development of other lymphomas (eg, familial risk, immunosuppression, other immune disorders, chemical and occupational exposures, and infectious agents) have not been convincingly identified as predisposing factors for MCL, with the possible exception of family history.

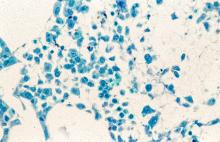

MCL is usually associated with reciprocal chromosomal translocation between chromosomes 11 and 14, t(11;14)(q13:q32), resulting in overexpression of cyclin D1, which plays a key role in tumor cell proliferation through cell-cycle dysregulation, chromosomal instability, and epigenetic regulation. Tumor cells (monoclonal B cells) express surface immunoglobulin, immunoglobulin M, or immunoglobulin D. Cells are usually CD5+ and pan B-cell antigen positive (eg, CD19, CD20, CD22) with no expression of CD10 and CD23. Histologic features include small-to-medium lymphocytes with scant cytoplasm, clumped chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and prominent nuclear clefts. Cytologic subtypes include classic MCL, the blastoid variant (large cells, dispersed chromatin, and a high mitotic rate), and the pleomorphic variant (cells of varying size, although many are large, with pale cytoplasm, oval irregular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli). Blastoid and pleomorphic MCL typically have a more aggressive natural history and are associated with inferior clinical outcomes.

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), an accurate pathologic diagnosis of the subtype is the most important initial step in the management of B-cell lymphomas, including pleomorphic MCL. The basic pathologic exam is the same for all subtypes, although additional testing may be needed in certain cases. An incisional or excisional lymph node biopsy is recommended. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy alone is typically not sufficient for the initial diagnosis of lymphoma; however, its diagnostic accuracy is significantly improved when it is used in combination with immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry. Immunohistochemistry is essential to differentiate MCL subtypes.

Essential workup procedures include a complete physical exam, with particular attention to node-bearing areas, including the Waldeyer ring, as well as the size of the liver and spleen, and assessment of performance status and B symptoms (fever, night sweats, unintentional weight loss). Laboratory studies should include complete blood count with differential, measurement of serum lactate dehydrogenase, hepatitis B virus testing, and a comprehensive metabolic panel. Required imaging studies include PET/CT (or chest/abdominal/pelvic CT with oral and intravenous contrast if PET/CT is not available) and multigated acquisition scanning or echocardiography when anthracyclines and anthracenedione-containing regimens are indicated.

A watch-and-wait approach may be appropriate for some patients with indolent MCL; however, patients with aggressive MCL, such as pleomorphic histology, require chemoimmunotherapy at diagnosis. For patients who relapse or achieve an incomplete response to first-line therapy, the NCCN guidelines recommend second-line treatment with a Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor–containing regimen. Available BTK inhibitors include acalabrutinib, ibrutinib ± rituximab, zanubrutinib, and pirtobrutinib. Chemoimmunotherapy with lenalidomide + rituximab is another second-line option and may be particularly helpful for patients in whom a BTK inhibitor is contraindicated. Anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy is a recommended option for the third line and beyond.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of pleomorphic mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

MCL is a rare, clinically and biologically heterogeneous B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It accounts for approximately 5%-7% of all lymphomas. In North America and Europe, its incidence is akin to that of noncutaneous, peripheral T-cell lymphomas. The typical age at diagnosis is between 60 and 70 years. Approximately 70% of all cases are seen in men.

Little is known about risk factors for the development of MCL. Factors that have been associated with the development of other lymphomas (eg, familial risk, immunosuppression, other immune disorders, chemical and occupational exposures, and infectious agents) have not been convincingly identified as predisposing factors for MCL, with the possible exception of family history.

MCL is usually associated with reciprocal chromosomal translocation between chromosomes 11 and 14, t(11;14)(q13:q32), resulting in overexpression of cyclin D1, which plays a key role in tumor cell proliferation through cell-cycle dysregulation, chromosomal instability, and epigenetic regulation. Tumor cells (monoclonal B cells) express surface immunoglobulin, immunoglobulin M, or immunoglobulin D. Cells are usually CD5+ and pan B-cell antigen positive (eg, CD19, CD20, CD22) with no expression of CD10 and CD23. Histologic features include small-to-medium lymphocytes with scant cytoplasm, clumped chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and prominent nuclear clefts. Cytologic subtypes include classic MCL, the blastoid variant (large cells, dispersed chromatin, and a high mitotic rate), and the pleomorphic variant (cells of varying size, although many are large, with pale cytoplasm, oval irregular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli). Blastoid and pleomorphic MCL typically have a more aggressive natural history and are associated with inferior clinical outcomes.

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), an accurate pathologic diagnosis of the subtype is the most important initial step in the management of B-cell lymphomas, including pleomorphic MCL. The basic pathologic exam is the same for all subtypes, although additional testing may be needed in certain cases. An incisional or excisional lymph node biopsy is recommended. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy alone is typically not sufficient for the initial diagnosis of lymphoma; however, its diagnostic accuracy is significantly improved when it is used in combination with immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry. Immunohistochemistry is essential to differentiate MCL subtypes.

Essential workup procedures include a complete physical exam, with particular attention to node-bearing areas, including the Waldeyer ring, as well as the size of the liver and spleen, and assessment of performance status and B symptoms (fever, night sweats, unintentional weight loss). Laboratory studies should include complete blood count with differential, measurement of serum lactate dehydrogenase, hepatitis B virus testing, and a comprehensive metabolic panel. Required imaging studies include PET/CT (or chest/abdominal/pelvic CT with oral and intravenous contrast if PET/CT is not available) and multigated acquisition scanning or echocardiography when anthracyclines and anthracenedione-containing regimens are indicated.

A watch-and-wait approach may be appropriate for some patients with indolent MCL; however, patients with aggressive MCL, such as pleomorphic histology, require chemoimmunotherapy at diagnosis. For patients who relapse or achieve an incomplete response to first-line therapy, the NCCN guidelines recommend second-line treatment with a Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor–containing regimen. Available BTK inhibitors include acalabrutinib, ibrutinib ± rituximab, zanubrutinib, and pirtobrutinib. Chemoimmunotherapy with lenalidomide + rituximab is another second-line option and may be particularly helpful for patients in whom a BTK inhibitor is contraindicated. Anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy is a recommended option for the third line and beyond.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

This patient's clinical presentation and laboratory findings are consistent with a diagnosis of pleomorphic mantle cell lymphoma (MCL).

MCL is a rare, clinically and biologically heterogeneous B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It accounts for approximately 5%-7% of all lymphomas. In North America and Europe, its incidence is akin to that of noncutaneous, peripheral T-cell lymphomas. The typical age at diagnosis is between 60 and 70 years. Approximately 70% of all cases are seen in men.

Little is known about risk factors for the development of MCL. Factors that have been associated with the development of other lymphomas (eg, familial risk, immunosuppression, other immune disorders, chemical and occupational exposures, and infectious agents) have not been convincingly identified as predisposing factors for MCL, with the possible exception of family history.

MCL is usually associated with reciprocal chromosomal translocation between chromosomes 11 and 14, t(11;14)(q13:q32), resulting in overexpression of cyclin D1, which plays a key role in tumor cell proliferation through cell-cycle dysregulation, chromosomal instability, and epigenetic regulation. Tumor cells (monoclonal B cells) express surface immunoglobulin, immunoglobulin M, or immunoglobulin D. Cells are usually CD5+ and pan B-cell antigen positive (eg, CD19, CD20, CD22) with no expression of CD10 and CD23. Histologic features include small-to-medium lymphocytes with scant cytoplasm, clumped chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and prominent nuclear clefts. Cytologic subtypes include classic MCL, the blastoid variant (large cells, dispersed chromatin, and a high mitotic rate), and the pleomorphic variant (cells of varying size, although many are large, with pale cytoplasm, oval irregular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli). Blastoid and pleomorphic MCL typically have a more aggressive natural history and are associated with inferior clinical outcomes.

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), an accurate pathologic diagnosis of the subtype is the most important initial step in the management of B-cell lymphomas, including pleomorphic MCL. The basic pathologic exam is the same for all subtypes, although additional testing may be needed in certain cases. An incisional or excisional lymph node biopsy is recommended. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy alone is typically not sufficient for the initial diagnosis of lymphoma; however, its diagnostic accuracy is significantly improved when it is used in combination with immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry. Immunohistochemistry is essential to differentiate MCL subtypes.

Essential workup procedures include a complete physical exam, with particular attention to node-bearing areas, including the Waldeyer ring, as well as the size of the liver and spleen, and assessment of performance status and B symptoms (fever, night sweats, unintentional weight loss). Laboratory studies should include complete blood count with differential, measurement of serum lactate dehydrogenase, hepatitis B virus testing, and a comprehensive metabolic panel. Required imaging studies include PET/CT (or chest/abdominal/pelvic CT with oral and intravenous contrast if PET/CT is not available) and multigated acquisition scanning or echocardiography when anthracyclines and anthracenedione-containing regimens are indicated.

A watch-and-wait approach may be appropriate for some patients with indolent MCL; however, patients with aggressive MCL, such as pleomorphic histology, require chemoimmunotherapy at diagnosis. For patients who relapse or achieve an incomplete response to first-line therapy, the NCCN guidelines recommend second-line treatment with a Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor–containing regimen. Available BTK inhibitors include acalabrutinib, ibrutinib ± rituximab, zanubrutinib, and pirtobrutinib. Chemoimmunotherapy with lenalidomide + rituximab is another second-line option and may be particularly helpful for patients in whom a BTK inhibitor is contraindicated. Anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy is a recommended option for the third line and beyond.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, Assistant Professor of Internal Medicine - Clinical, Division of Hematology, The Ohio State University James Comprehensive Cancer Center, Columbus, OH.

Timothy J. Voorhees, MD, MSCR, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Received research grant from: AstraZeneca; Morphosys; Incyte; Recordati.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 62-year-old man with no significant past medical history presents with a 3-month history of fever, night sweats, upper abdominal pain and bloating, and unintentional weight loss. He does not currently take any medications. His height and weight are 6 ft 2 in and 171 lb (BMI 22).

Physical examination reveals generalized lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly. Subsequently, an excisional lymph node biopsy is performed. Histologic examination of the specimen reveals sheets of mostly large cells of varying sizes, with nuclear overlap and extensive necrosis. Cytology findings include large lymphocytes with pale cytoplasm, clumped chromatin, oval irregular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. Pertinent findings from immunohistochemical staining include the presence of t(11:14), Ki67 > 30%, CD5 and CD20 positivity, and CD10 and CD23 negativity. Centroblasts are absent.

MCL Treatment

Upfront Transplants in Patients With Mantle Cell Lymphoma

What is your outlook on the role of upfront autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) for patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL)?

Dr. Barrientos: Most of the data that we have for upfront ASCT for young patients in frontline therapy come from the era when we did not use rituximab, and the data have not kept up with the pace of all the recent advances. Rituximab has changed the way we approach maintenance therapy after induction therapy. No randomized controlled trial data (in regimens that incorporate rituximab and cytarabine) have demonstrated a benefit in overall survival (OS) with ASCT in the modern era.

There is a lot to consider for every patient with MCL before we start therapy or discuss upfront transplant. MCL is one of these non-Hodgkin lymphomas that unfortunately can be aggressive in some patients depending on their prognostic markers and particular clinical features of the disease. Some patients have a more indolent form, whereas others have a more aggressive presentation at the time of diagnosis. The disease is heterogeneous and will respond differently to certain regimens. For example, patients with MCL who have a high proliferation rate, blastoid morphology, multiple chromosomal aberrations, complex karyotype, and/or the presence of tumor suppressor protein P53 (TP53) mutation will likely have a more aggressive course. Fitness for transplant is also an important consideration regardless of age; that is, a patient with comorbid end-stage chronic kidney or liver disease will not be able to tolerate a transplant.

Even with optimal therapy that incorporates rituximab and cytarabine, pursuing a transplant does not necessarily benefit survival in patients with a known TP53 mutation, as these patients typically experience increased toxicity without improved OS. We know they will not respond well, and we should discuss the available data so that the patients can make a sound decision and consider participation in a clinical trial that incorporates novel agents. Another type of mutation—cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A)—also has lower OS. Concurrent deletion of CDKN2A and TP53 aberration (deletion and/or mutation) are known to be associated with lower OS given their chemoresistant nature. Patients with these genetic mutations should not be offered standard ASCT, but rather they should be identified early on and prioritized to participate in clinical trials.

Importantly, the role of upfront ASCT is changing right now, based on a recent trial that was presented at the latest American Society of Hematology meeting in 2022. The TRIANGLE trial demonstrated the addition of ibrutinib (a first-generation Bruton tyrosine kinase [BTK] inhibitor) to standard chemoimmunotherapy induction and 2 years of ibrutinib maintenance can improve outcomes vs standard chemoimmunotherapy induction and ASCT alone for younger patients with MCL. However, longer follow-up is needed to fully elucidate the role of ASCT in the era of BTK inhibitors when incorporated early on into the treatment paradigm.

The TRIANGLE trial was an international, randomized 3-arm phase 3 trial (EudraCT-no. 2014-001363-12) for young (up to 65 years) fit patients with histologically confirmed, untreated, advanced stage II-IV MCL. In the control arm A, patients received an alternating R-CHOP/R-DHAP induction followed by myeloablative consolidation (ASCT). In arm A+I, ibrutinib was added to the R-CHOP cycles (560 mg day 1-19) and was applied as maintenance (continuous dosing) for 2 years. In arm I, the same induction and maintenance was applied but high-dose consolidation and ASCT was skipped. A rituximab maintenance (single doses every 2 months for up to 3 years) was allowed to be added in all study arms according to national clinical routine.

The study showed that failure-free survival at 3 years was 72% with chemotherapy alone, 86% with ibrutinib alone, and 88% with ibrutinib plus ASCT. However, the ibrutinib plus ASCT group seemed to have much more toxicity, comorbidities, and other complications from the transplant. The OS data are not mature yet, but looking at the available data, ibrutinib alone might be more beneficial to our patients— not only in terms of efficacy, but also in tolerability and response, with less toxicity over time.

To put things in perspective, we did not have good salvage therapies a decade ago. At the time ASCT was incorporated, it was a good option that allowed numerous patients to achieve a deep response with durable remission duration. Before ibrutinib was approved, the overall response rate for the best salvage therapies was not as encouraging as the initial therapy and, with each relapse, the duration of response shortened. When ibrutinib came along, the overall response rate improved significantly. But again, these patients had relapsed/refractory disease. Researchers have been investigating what would happen if we used such a drug in earlier lines of therapy. Can we get better outcomes? Can we get patients in remission longer, similar to what we have seen with ASCT, but without the ASCT?

There has never been a single modern trial that has demonstrated that transplant improves survival. Transplantation can improve progression-free survival, but not OS. For a disease for which we do not have a cure, if we can keep patients in remission with a good salvage therapy and give them a better quality of life, without subjecting them to an ASCT, then I might choose that. New targeted agents and novel therapies are in clinical development all the time, so the future is bright for patients with this diagnosis. Given the novel salvage therapies in the pipeline, we may be able to no longer recommend ASCT upfront for most patients soon.

Can you share more about the potential benefits of using salvage therapies over ASCT, and particularly any promising newer agents in the salvage therapy setting?

Dr. Barrientos: Recently we had the FDA approval of pirtobrutinib—a noncovalently bound BTK inhibitor—for patients with relapsed/refractory MCL in whom at least 2 lines of systemic therapy had failed, including another BTK inhibitor. In the trial that led to the accelerated approval, pirtobrutinib-treated patients showed an overall response rate of 50% in those who received the drug at 200 mg daily (n = 120); most of the responses were partial responses. The efficacy of other novel drugs are being studied in patients with MCL. For example, ROR1 (receptor tyrosine kinase–like orphan receptor 1) inhibitors and BTK degraders are currently in clinical trials. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy targeting CD19 has been approved for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed or refractory MCL, and this may be an option for some patients.

Multiple novel agents might be able to salvage our patients without subjecting them to an upfront transplant. My hope is to get away from using the intense chemotherapy regimens that might cause myelosuppression, infection risk, or other toxicities, and try to stay with the novel agents. We need to do better for our patients.

Based on the data we now have, until there is a trial that demonstrates a higher OS rate with ASCT, it is hard for me to tell a patient to blindly pursue ASCT without learning more about all the available options. If you have access to a good salvage therapy, especially with all these new promising agents, a patient might be able to stay in remission without having ASCT, which can still have an increased risk of morbidity.

Are there certain patient groups that should never be considered for ASCT?

Dr. Barrientos: Younger patients with the CDKN2A gene—which represents about 22% of patients—and those who have a TP53 mutation should not be considered for a standard transplant because they have a worse outcome independent of the treatment. I would also include complex karyotype patients because of the same nature of the chromosomal aberrations. The more genetic aberrations that a patient has, the more likelihood that any chemotherapy will damage the DNA further and create a more aggressive clone. Instead, I would recommend that young patients in this category participate in a clinical trial with novel agents.

With novel therapies in the pipeline, the availability of CAR T, and now the bispecific antibodies such as blinatumomab and HexAbs coming along, the number of patients who may opt out of ASCT may increase. I have a long discussion with my patients. The more educated they are, the better it is for the patient. At the end of the day, the most important thing for me, with any therapy, is: how does the patient feel? Because if we cannot cure a patient or provide a survival advantage, I do not want to give that patient something that will decrease their quality of life. I would rather keep the patient in some sort of stable disease remission, comfortable, and having a good quality of life. That is my goal for anyone who cannot be cured. Now if it is a curable disease, like a diffuse large cell lymphoma or a Burkitt’s lymphoma, then it is a different story. But for people with MCL, a disease that you cannot cure, or chronic lymphocytic leukemia or follicular lymphoma, then it becomes a different discussion. Undetectable minimal residual disease correlates with longer remission durations, but sometimes trying to achieve that, you can actually do a lot of harm to some patients.

Are there any other conversations you have with your patients in day-to-day practice?

Dr. Barrientos: I always tell my patients to be on top of the age-appropriate cancer screening recommendations. For example, they should see a dermatologist once a year. Men should make sure that their prostate is checked. I recommend women get breast mammograms, Pap smears, and most importantly to avoid smoking—and that includes vaping. It is important to lead a healthy life to minimize the risk of secondary malignancies.

For risk of infections, I recommend to all my patients to be up to date on their vaccinations, such as pneumonia if they are older than 65, Shingrix for prevention of reactivation of varicella or chickenpox, and the flu shot once a year. I also recommend the COVID-19 vaccine even now, as our patients with blood disorders might have a harder time fighting COVID-19 infection. I always tell my patients to please reach out to us because we can discuss the use of antivirals such as Paxlovid (nirmatrelvir/ritonavir), and if they are sick, then they can get remdesivir in the hospital.

I want to touch on health literacy and disparities for a moment. I have some younger patients who are Latin or Black with uncontrolled hypertension or diabetes, even at a young age, and do not realize that I can treat their cancer into remission, but if their blood glucose is in the 500 range, they could die from their diabetes. So talking with patients about their overall health is important. Survivorship issues are important, especially if patients are diagnosed at a young age. We have known for a long time that chemotherapy can create cardiac events, arrhythmias, and heart disease. Therefore, I always tell patients with metabolic syndrome to try to exercise and eat healthy. Patients should get an electrocardiogram and see an internist at least once a year to make sure their cholesterol is well controlled. I think now we are being more cognizant that many complications can happen even 10 years after cancer treatment.

What is your outlook on the role of upfront autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) for patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL)?

Dr. Barrientos: Most of the data that we have for upfront ASCT for young patients in frontline therapy come from the era when we did not use rituximab, and the data have not kept up with the pace of all the recent advances. Rituximab has changed the way we approach maintenance therapy after induction therapy. No randomized controlled trial data (in regimens that incorporate rituximab and cytarabine) have demonstrated a benefit in overall survival (OS) with ASCT in the modern era.

There is a lot to consider for every patient with MCL before we start therapy or discuss upfront transplant. MCL is one of these non-Hodgkin lymphomas that unfortunately can be aggressive in some patients depending on their prognostic markers and particular clinical features of the disease. Some patients have a more indolent form, whereas others have a more aggressive presentation at the time of diagnosis. The disease is heterogeneous and will respond differently to certain regimens. For example, patients with MCL who have a high proliferation rate, blastoid morphology, multiple chromosomal aberrations, complex karyotype, and/or the presence of tumor suppressor protein P53 (TP53) mutation will likely have a more aggressive course. Fitness for transplant is also an important consideration regardless of age; that is, a patient with comorbid end-stage chronic kidney or liver disease will not be able to tolerate a transplant.

Even with optimal therapy that incorporates rituximab and cytarabine, pursuing a transplant does not necessarily benefit survival in patients with a known TP53 mutation, as these patients typically experience increased toxicity without improved OS. We know they will not respond well, and we should discuss the available data so that the patients can make a sound decision and consider participation in a clinical trial that incorporates novel agents. Another type of mutation—cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A)—also has lower OS. Concurrent deletion of CDKN2A and TP53 aberration (deletion and/or mutation) are known to be associated with lower OS given their chemoresistant nature. Patients with these genetic mutations should not be offered standard ASCT, but rather they should be identified early on and prioritized to participate in clinical trials.

Importantly, the role of upfront ASCT is changing right now, based on a recent trial that was presented at the latest American Society of Hematology meeting in 2022. The TRIANGLE trial demonstrated the addition of ibrutinib (a first-generation Bruton tyrosine kinase [BTK] inhibitor) to standard chemoimmunotherapy induction and 2 years of ibrutinib maintenance can improve outcomes vs standard chemoimmunotherapy induction and ASCT alone for younger patients with MCL. However, longer follow-up is needed to fully elucidate the role of ASCT in the era of BTK inhibitors when incorporated early on into the treatment paradigm.

The TRIANGLE trial was an international, randomized 3-arm phase 3 trial (EudraCT-no. 2014-001363-12) for young (up to 65 years) fit patients with histologically confirmed, untreated, advanced stage II-IV MCL. In the control arm A, patients received an alternating R-CHOP/R-DHAP induction followed by myeloablative consolidation (ASCT). In arm A+I, ibrutinib was added to the R-CHOP cycles (560 mg day 1-19) and was applied as maintenance (continuous dosing) for 2 years. In arm I, the same induction and maintenance was applied but high-dose consolidation and ASCT was skipped. A rituximab maintenance (single doses every 2 months for up to 3 years) was allowed to be added in all study arms according to national clinical routine.

The study showed that failure-free survival at 3 years was 72% with chemotherapy alone, 86% with ibrutinib alone, and 88% with ibrutinib plus ASCT. However, the ibrutinib plus ASCT group seemed to have much more toxicity, comorbidities, and other complications from the transplant. The OS data are not mature yet, but looking at the available data, ibrutinib alone might be more beneficial to our patients— not only in terms of efficacy, but also in tolerability and response, with less toxicity over time.

To put things in perspective, we did not have good salvage therapies a decade ago. At the time ASCT was incorporated, it was a good option that allowed numerous patients to achieve a deep response with durable remission duration. Before ibrutinib was approved, the overall response rate for the best salvage therapies was not as encouraging as the initial therapy and, with each relapse, the duration of response shortened. When ibrutinib came along, the overall response rate improved significantly. But again, these patients had relapsed/refractory disease. Researchers have been investigating what would happen if we used such a drug in earlier lines of therapy. Can we get better outcomes? Can we get patients in remission longer, similar to what we have seen with ASCT, but without the ASCT?

There has never been a single modern trial that has demonstrated that transplant improves survival. Transplantation can improve progression-free survival, but not OS. For a disease for which we do not have a cure, if we can keep patients in remission with a good salvage therapy and give them a better quality of life, without subjecting them to an ASCT, then I might choose that. New targeted agents and novel therapies are in clinical development all the time, so the future is bright for patients with this diagnosis. Given the novel salvage therapies in the pipeline, we may be able to no longer recommend ASCT upfront for most patients soon.

Can you share more about the potential benefits of using salvage therapies over ASCT, and particularly any promising newer agents in the salvage therapy setting?

Dr. Barrientos: Recently we had the FDA approval of pirtobrutinib—a noncovalently bound BTK inhibitor—for patients with relapsed/refractory MCL in whom at least 2 lines of systemic therapy had failed, including another BTK inhibitor. In the trial that led to the accelerated approval, pirtobrutinib-treated patients showed an overall response rate of 50% in those who received the drug at 200 mg daily (n = 120); most of the responses were partial responses. The efficacy of other novel drugs are being studied in patients with MCL. For example, ROR1 (receptor tyrosine kinase–like orphan receptor 1) inhibitors and BTK degraders are currently in clinical trials. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy targeting CD19 has been approved for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed or refractory MCL, and this may be an option for some patients.

Multiple novel agents might be able to salvage our patients without subjecting them to an upfront transplant. My hope is to get away from using the intense chemotherapy regimens that might cause myelosuppression, infection risk, or other toxicities, and try to stay with the novel agents. We need to do better for our patients.

Based on the data we now have, until there is a trial that demonstrates a higher OS rate with ASCT, it is hard for me to tell a patient to blindly pursue ASCT without learning more about all the available options. If you have access to a good salvage therapy, especially with all these new promising agents, a patient might be able to stay in remission without having ASCT, which can still have an increased risk of morbidity.

Are there certain patient groups that should never be considered for ASCT?

Dr. Barrientos: Younger patients with the CDKN2A gene—which represents about 22% of patients—and those who have a TP53 mutation should not be considered for a standard transplant because they have a worse outcome independent of the treatment. I would also include complex karyotype patients because of the same nature of the chromosomal aberrations. The more genetic aberrations that a patient has, the more likelihood that any chemotherapy will damage the DNA further and create a more aggressive clone. Instead, I would recommend that young patients in this category participate in a clinical trial with novel agents.

With novel therapies in the pipeline, the availability of CAR T, and now the bispecific antibodies such as blinatumomab and HexAbs coming along, the number of patients who may opt out of ASCT may increase. I have a long discussion with my patients. The more educated they are, the better it is for the patient. At the end of the day, the most important thing for me, with any therapy, is: how does the patient feel? Because if we cannot cure a patient or provide a survival advantage, I do not want to give that patient something that will decrease their quality of life. I would rather keep the patient in some sort of stable disease remission, comfortable, and having a good quality of life. That is my goal for anyone who cannot be cured. Now if it is a curable disease, like a diffuse large cell lymphoma or a Burkitt’s lymphoma, then it is a different story. But for people with MCL, a disease that you cannot cure, or chronic lymphocytic leukemia or follicular lymphoma, then it becomes a different discussion. Undetectable minimal residual disease correlates with longer remission durations, but sometimes trying to achieve that, you can actually do a lot of harm to some patients.

Are there any other conversations you have with your patients in day-to-day practice?

Dr. Barrientos: I always tell my patients to be on top of the age-appropriate cancer screening recommendations. For example, they should see a dermatologist once a year. Men should make sure that their prostate is checked. I recommend women get breast mammograms, Pap smears, and most importantly to avoid smoking—and that includes vaping. It is important to lead a healthy life to minimize the risk of secondary malignancies.

For risk of infections, I recommend to all my patients to be up to date on their vaccinations, such as pneumonia if they are older than 65, Shingrix for prevention of reactivation of varicella or chickenpox, and the flu shot once a year. I also recommend the COVID-19 vaccine even now, as our patients with blood disorders might have a harder time fighting COVID-19 infection. I always tell my patients to please reach out to us because we can discuss the use of antivirals such as Paxlovid (nirmatrelvir/ritonavir), and if they are sick, then they can get remdesivir in the hospital.

I want to touch on health literacy and disparities for a moment. I have some younger patients who are Latin or Black with uncontrolled hypertension or diabetes, even at a young age, and do not realize that I can treat their cancer into remission, but if their blood glucose is in the 500 range, they could die from their diabetes. So talking with patients about their overall health is important. Survivorship issues are important, especially if patients are diagnosed at a young age. We have known for a long time that chemotherapy can create cardiac events, arrhythmias, and heart disease. Therefore, I always tell patients with metabolic syndrome to try to exercise and eat healthy. Patients should get an electrocardiogram and see an internist at least once a year to make sure their cholesterol is well controlled. I think now we are being more cognizant that many complications can happen even 10 years after cancer treatment.

What is your outlook on the role of upfront autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) for patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL)?

Dr. Barrientos: Most of the data that we have for upfront ASCT for young patients in frontline therapy come from the era when we did not use rituximab, and the data have not kept up with the pace of all the recent advances. Rituximab has changed the way we approach maintenance therapy after induction therapy. No randomized controlled trial data (in regimens that incorporate rituximab and cytarabine) have demonstrated a benefit in overall survival (OS) with ASCT in the modern era.

There is a lot to consider for every patient with MCL before we start therapy or discuss upfront transplant. MCL is one of these non-Hodgkin lymphomas that unfortunately can be aggressive in some patients depending on their prognostic markers and particular clinical features of the disease. Some patients have a more indolent form, whereas others have a more aggressive presentation at the time of diagnosis. The disease is heterogeneous and will respond differently to certain regimens. For example, patients with MCL who have a high proliferation rate, blastoid morphology, multiple chromosomal aberrations, complex karyotype, and/or the presence of tumor suppressor protein P53 (TP53) mutation will likely have a more aggressive course. Fitness for transplant is also an important consideration regardless of age; that is, a patient with comorbid end-stage chronic kidney or liver disease will not be able to tolerate a transplant.

Even with optimal therapy that incorporates rituximab and cytarabine, pursuing a transplant does not necessarily benefit survival in patients with a known TP53 mutation, as these patients typically experience increased toxicity without improved OS. We know they will not respond well, and we should discuss the available data so that the patients can make a sound decision and consider participation in a clinical trial that incorporates novel agents. Another type of mutation—cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A)—also has lower OS. Concurrent deletion of CDKN2A and TP53 aberration (deletion and/or mutation) are known to be associated with lower OS given their chemoresistant nature. Patients with these genetic mutations should not be offered standard ASCT, but rather they should be identified early on and prioritized to participate in clinical trials.

Importantly, the role of upfront ASCT is changing right now, based on a recent trial that was presented at the latest American Society of Hematology meeting in 2022. The TRIANGLE trial demonstrated the addition of ibrutinib (a first-generation Bruton tyrosine kinase [BTK] inhibitor) to standard chemoimmunotherapy induction and 2 years of ibrutinib maintenance can improve outcomes vs standard chemoimmunotherapy induction and ASCT alone for younger patients with MCL. However, longer follow-up is needed to fully elucidate the role of ASCT in the era of BTK inhibitors when incorporated early on into the treatment paradigm.

The TRIANGLE trial was an international, randomized 3-arm phase 3 trial (EudraCT-no. 2014-001363-12) for young (up to 65 years) fit patients with histologically confirmed, untreated, advanced stage II-IV MCL. In the control arm A, patients received an alternating R-CHOP/R-DHAP induction followed by myeloablative consolidation (ASCT). In arm A+I, ibrutinib was added to the R-CHOP cycles (560 mg day 1-19) and was applied as maintenance (continuous dosing) for 2 years. In arm I, the same induction and maintenance was applied but high-dose consolidation and ASCT was skipped. A rituximab maintenance (single doses every 2 months for up to 3 years) was allowed to be added in all study arms according to national clinical routine.

The study showed that failure-free survival at 3 years was 72% with chemotherapy alone, 86% with ibrutinib alone, and 88% with ibrutinib plus ASCT. However, the ibrutinib plus ASCT group seemed to have much more toxicity, comorbidities, and other complications from the transplant. The OS data are not mature yet, but looking at the available data, ibrutinib alone might be more beneficial to our patients— not only in terms of efficacy, but also in tolerability and response, with less toxicity over time.

To put things in perspective, we did not have good salvage therapies a decade ago. At the time ASCT was incorporated, it was a good option that allowed numerous patients to achieve a deep response with durable remission duration. Before ibrutinib was approved, the overall response rate for the best salvage therapies was not as encouraging as the initial therapy and, with each relapse, the duration of response shortened. When ibrutinib came along, the overall response rate improved significantly. But again, these patients had relapsed/refractory disease. Researchers have been investigating what would happen if we used such a drug in earlier lines of therapy. Can we get better outcomes? Can we get patients in remission longer, similar to what we have seen with ASCT, but without the ASCT?

There has never been a single modern trial that has demonstrated that transplant improves survival. Transplantation can improve progression-free survival, but not OS. For a disease for which we do not have a cure, if we can keep patients in remission with a good salvage therapy and give them a better quality of life, without subjecting them to an ASCT, then I might choose that. New targeted agents and novel therapies are in clinical development all the time, so the future is bright for patients with this diagnosis. Given the novel salvage therapies in the pipeline, we may be able to no longer recommend ASCT upfront for most patients soon.

Can you share more about the potential benefits of using salvage therapies over ASCT, and particularly any promising newer agents in the salvage therapy setting?

Dr. Barrientos: Recently we had the FDA approval of pirtobrutinib—a noncovalently bound BTK inhibitor—for patients with relapsed/refractory MCL in whom at least 2 lines of systemic therapy had failed, including another BTK inhibitor. In the trial that led to the accelerated approval, pirtobrutinib-treated patients showed an overall response rate of 50% in those who received the drug at 200 mg daily (n = 120); most of the responses were partial responses. The efficacy of other novel drugs are being studied in patients with MCL. For example, ROR1 (receptor tyrosine kinase–like orphan receptor 1) inhibitors and BTK degraders are currently in clinical trials. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy targeting CD19 has been approved for the treatment of adult patients with relapsed or refractory MCL, and this may be an option for some patients.

Multiple novel agents might be able to salvage our patients without subjecting them to an upfront transplant. My hope is to get away from using the intense chemotherapy regimens that might cause myelosuppression, infection risk, or other toxicities, and try to stay with the novel agents. We need to do better for our patients.

Based on the data we now have, until there is a trial that demonstrates a higher OS rate with ASCT, it is hard for me to tell a patient to blindly pursue ASCT without learning more about all the available options. If you have access to a good salvage therapy, especially with all these new promising agents, a patient might be able to stay in remission without having ASCT, which can still have an increased risk of morbidity.

Are there certain patient groups that should never be considered for ASCT?

Dr. Barrientos: Younger patients with the CDKN2A gene—which represents about 22% of patients—and those who have a TP53 mutation should not be considered for a standard transplant because they have a worse outcome independent of the treatment. I would also include complex karyotype patients because of the same nature of the chromosomal aberrations. The more genetic aberrations that a patient has, the more likelihood that any chemotherapy will damage the DNA further and create a more aggressive clone. Instead, I would recommend that young patients in this category participate in a clinical trial with novel agents.

With novel therapies in the pipeline, the availability of CAR T, and now the bispecific antibodies such as blinatumomab and HexAbs coming along, the number of patients who may opt out of ASCT may increase. I have a long discussion with my patients. The more educated they are, the better it is for the patient. At the end of the day, the most important thing for me, with any therapy, is: how does the patient feel? Because if we cannot cure a patient or provide a survival advantage, I do not want to give that patient something that will decrease their quality of life. I would rather keep the patient in some sort of stable disease remission, comfortable, and having a good quality of life. That is my goal for anyone who cannot be cured. Now if it is a curable disease, like a diffuse large cell lymphoma or a Burkitt’s lymphoma, then it is a different story. But for people with MCL, a disease that you cannot cure, or chronic lymphocytic leukemia or follicular lymphoma, then it becomes a different discussion. Undetectable minimal residual disease correlates with longer remission durations, but sometimes trying to achieve that, you can actually do a lot of harm to some patients.

Are there any other conversations you have with your patients in day-to-day practice?

Dr. Barrientos: I always tell my patients to be on top of the age-appropriate cancer screening recommendations. For example, they should see a dermatologist once a year. Men should make sure that their prostate is checked. I recommend women get breast mammograms, Pap smears, and most importantly to avoid smoking—and that includes vaping. It is important to lead a healthy life to minimize the risk of secondary malignancies.

For risk of infections, I recommend to all my patients to be up to date on their vaccinations, such as pneumonia if they are older than 65, Shingrix for prevention of reactivation of varicella or chickenpox, and the flu shot once a year. I also recommend the COVID-19 vaccine even now, as our patients with blood disorders might have a harder time fighting COVID-19 infection. I always tell my patients to please reach out to us because we can discuss the use of antivirals such as Paxlovid (nirmatrelvir/ritonavir), and if they are sick, then they can get remdesivir in the hospital.

I want to touch on health literacy and disparities for a moment. I have some younger patients who are Latin or Black with uncontrolled hypertension or diabetes, even at a young age, and do not realize that I can treat their cancer into remission, but if their blood glucose is in the 500 range, they could die from their diabetes. So talking with patients about their overall health is important. Survivorship issues are important, especially if patients are diagnosed at a young age. We have known for a long time that chemotherapy can create cardiac events, arrhythmias, and heart disease. Therefore, I always tell patients with metabolic syndrome to try to exercise and eat healthy. Patients should get an electrocardiogram and see an internist at least once a year to make sure their cholesterol is well controlled. I think now we are being more cognizant that many complications can happen even 10 years after cancer treatment.

Erythema extent predicts death in cutaneous GVHD

“There is value in collecting erythema serially over time as a continuous variable on a scale of 0%-100%” to identify high-risk patients for prophylactic and preemptive treatment, say investigators led by dermatologist Emily Baumrin, MD, director of the GVHD clinic at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

They report a study of more than 300 patients with ccGVHD, which found that the extent of skin erythema strongly predicted the risk for death from GVHD.

Of the 267 patients with cutaneous GVHD at baseline, 103 patients died, the majority without a relapse of their blood cancer.

With additional research, erythema body surface area (BSA) should be “introduced as an outcome measure in clinical practice and trials,” they conclude.

At the moment, the NIH Skin Score is commonly used for risk assessment in cutaneous GVHD, but the researchers found that erythema BSA out-predicts this score.

The investigators explain that the NIH Skin Score does incorporate erythema surface area, but it does so as a categorical variable, not a continuous variable. Among other additional factors, it also includes assessments of skin sclerosis, which the investigators found was not associated with GVHD mortality.

Overall, the composite score waters down the weight given to erythema BSA because the score is “driven by stable sclerotic features, and erythema changes are missed,” they explain.

The study was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

Study details

The study included 469 patients with chronic GVHD (cGVHD), of whom 267 (57%) had cutaneous cGVHD at enrollment and 89 (19%) developed skin involvement subsequently.

All of the patients were on systemic immunosuppression for GVHD after allogeneic stem cell transplants for various blood cancers.

They were enrolled from 2007 through 2012 at nine U.S. medical centers – all members of the Chronic Graft Versus Host Disease Consortium – and they were followed until 2018.

Erythema BSA and NIH Skin Score were assessed at baseline and then every 3-6 months. Erythema was the first manifestation of skin involvement in the majority of patients, with a median surface area involvement of 11% at baseline.

The study team found that the extent of erythema at first follow-up visit was associated with both nonrelapse mortality (hazard ratio, 1.33 per 10% BSA increase; P < .001) and overall survival (HR, 1.28 per 10% BSA increase; P < .001), whereas extent of sclerotic skin involvement was not associated with either.

Participants in the study were predominantly White. The investigators note that “BSA assessments of erythema may be less reliable in patients with darker skin.”

The work was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Baumrin had no disclosures; one coauthor is an employee of CorEvitas, and two others reported grants/adviser fees from several companies, including Janssen, Mallinckrodt, and Pfizer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“There is value in collecting erythema serially over time as a continuous variable on a scale of 0%-100%” to identify high-risk patients for prophylactic and preemptive treatment, say investigators led by dermatologist Emily Baumrin, MD, director of the GVHD clinic at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

They report a study of more than 300 patients with ccGVHD, which found that the extent of skin erythema strongly predicted the risk for death from GVHD.

Of the 267 patients with cutaneous GVHD at baseline, 103 patients died, the majority without a relapse of their blood cancer.

With additional research, erythema body surface area (BSA) should be “introduced as an outcome measure in clinical practice and trials,” they conclude.

At the moment, the NIH Skin Score is commonly used for risk assessment in cutaneous GVHD, but the researchers found that erythema BSA out-predicts this score.

The investigators explain that the NIH Skin Score does incorporate erythema surface area, but it does so as a categorical variable, not a continuous variable. Among other additional factors, it also includes assessments of skin sclerosis, which the investigators found was not associated with GVHD mortality.

Overall, the composite score waters down the weight given to erythema BSA because the score is “driven by stable sclerotic features, and erythema changes are missed,” they explain.

The study was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

Study details

The study included 469 patients with chronic GVHD (cGVHD), of whom 267 (57%) had cutaneous cGVHD at enrollment and 89 (19%) developed skin involvement subsequently.

All of the patients were on systemic immunosuppression for GVHD after allogeneic stem cell transplants for various blood cancers.

They were enrolled from 2007 through 2012 at nine U.S. medical centers – all members of the Chronic Graft Versus Host Disease Consortium – and they were followed until 2018.

Erythema BSA and NIH Skin Score were assessed at baseline and then every 3-6 months. Erythema was the first manifestation of skin involvement in the majority of patients, with a median surface area involvement of 11% at baseline.

The study team found that the extent of erythema at first follow-up visit was associated with both nonrelapse mortality (hazard ratio, 1.33 per 10% BSA increase; P < .001) and overall survival (HR, 1.28 per 10% BSA increase; P < .001), whereas extent of sclerotic skin involvement was not associated with either.

Participants in the study were predominantly White. The investigators note that “BSA assessments of erythema may be less reliable in patients with darker skin.”

The work was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Baumrin had no disclosures; one coauthor is an employee of CorEvitas, and two others reported grants/adviser fees from several companies, including Janssen, Mallinckrodt, and Pfizer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

“There is value in collecting erythema serially over time as a continuous variable on a scale of 0%-100%” to identify high-risk patients for prophylactic and preemptive treatment, say investigators led by dermatologist Emily Baumrin, MD, director of the GVHD clinic at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

They report a study of more than 300 patients with ccGVHD, which found that the extent of skin erythema strongly predicted the risk for death from GVHD.

Of the 267 patients with cutaneous GVHD at baseline, 103 patients died, the majority without a relapse of their blood cancer.

With additional research, erythema body surface area (BSA) should be “introduced as an outcome measure in clinical practice and trials,” they conclude.

At the moment, the NIH Skin Score is commonly used for risk assessment in cutaneous GVHD, but the researchers found that erythema BSA out-predicts this score.

The investigators explain that the NIH Skin Score does incorporate erythema surface area, but it does so as a categorical variable, not a continuous variable. Among other additional factors, it also includes assessments of skin sclerosis, which the investigators found was not associated with GVHD mortality.

Overall, the composite score waters down the weight given to erythema BSA because the score is “driven by stable sclerotic features, and erythema changes are missed,” they explain.

The study was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

Study details

The study included 469 patients with chronic GVHD (cGVHD), of whom 267 (57%) had cutaneous cGVHD at enrollment and 89 (19%) developed skin involvement subsequently.

All of the patients were on systemic immunosuppression for GVHD after allogeneic stem cell transplants for various blood cancers.

They were enrolled from 2007 through 2012 at nine U.S. medical centers – all members of the Chronic Graft Versus Host Disease Consortium – and they were followed until 2018.

Erythema BSA and NIH Skin Score were assessed at baseline and then every 3-6 months. Erythema was the first manifestation of skin involvement in the majority of patients, with a median surface area involvement of 11% at baseline.

The study team found that the extent of erythema at first follow-up visit was associated with both nonrelapse mortality (hazard ratio, 1.33 per 10% BSA increase; P < .001) and overall survival (HR, 1.28 per 10% BSA increase; P < .001), whereas extent of sclerotic skin involvement was not associated with either.

Participants in the study were predominantly White. The investigators note that “BSA assessments of erythema may be less reliable in patients with darker skin.”

The work was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Baumrin had no disclosures; one coauthor is an employee of CorEvitas, and two others reported grants/adviser fees from several companies, including Janssen, Mallinckrodt, and Pfizer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Evolving Role for Transplantation in Mantle Cell Lymphoma

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) has served as a paradigm of progress among the non-Hodgkin lymphomas over the past 30 years. It was originally defined within the Kiel classification as centrocytic lymphoma, then renamed MCL once the characteristic translocation and resulting cyclin D1 overexpression were identified. These diagnostic markers allowed for the characterization of MCL subtypes as well as the initiation of MCL-focused clinical trials which, in turn, led to regulatory approval of more effective regimens, new therapeutic agents, and an improvement in overall survival (OS) from around 3 years to more than 10 years for many patients.

Despite this progress, virtually all patients relapse, and a cure remains elusive for most. In younger (< 65 to 70 years), medically-fit patients who are transplant-eligible and have symptomatic MCL, a standard of care has been induction chemoimmunotherapy containing high-dose cytarabine followed by ASCT consolidation. For example, a clinical trial of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) alternating with R-DHAP (rituximab, dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, cisplatin; 3 cycles each) showed a significant benefit over R-CHOP x 6 cycles; at a median follow-up of 10.6 years, the time-to-treatment failure was 8.4 v 3.9 years. In another trial, all patients received induction R-DHAP (with cisplatin or an alternative platinum agent) x 4 cycles followed by ASCT. Those patients randomized to post-ASCT maintenance rituximab for 3 years had significantly improved, 4-year progression-free survival (PFS) as compared with observation only (83% vs 64%, p < 0.001); maintenance also significantly improved OS.

Although ASCT consolidation followed by maintenance became widely adopted on the basis of these and other clinical trials, important questions remain:

First, MCL is biologically and clinically quite heterogeneous. Several prognostic tools such as the MCL International Prognostic Index (MIPI) scoring system and biomarkers are available to define lower- versus higher-risk subtypes, but none is routinely used for treatment planning. About 15% of MCL patients present with a highly-aggressive blastoid or pleomorphic variant that usually carries a TP53 mutation or deletion. Given the short survival and limited benefit from dose-intensive chemotherapy and ASCT in TP53-mutated MCL, should transplant be avoided in these patients?

Second, if deep remission is achieved following front-line therapy, defined as positron emission tomography (PET) negative and measurable residual disease (MRD) negative, will high-dose chemotherapy and ASCT provide additional benefits or only toxicity? This question is being addressed by the ongoing ECOG 4151 study, a risk-adapted trial in which post-induction MRD-negative patients are randomized to standard ASCT consolidation plus maintenance rituximab vs maintenance only.

Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (BTKi) are now among the most used agents for relapsed MCL. Recent clinical trials testing the integration of a BTKi into first- or second-line therapy have shown increased response rates and variable clinical outcomes and toxicities for the combinations, depending upon the chemotherapy- and non-chemotherapy backbones utilized, as well as the BTKi. Combinations with the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax plus chemotherapy or BTKi are also showing promise.

The activity of BTKi in MCL led the European MCL Network (EMCL) to design the 3-arm TRIANGLE study to analyze the potential of ibrutinib to improve outcomes when given in conjunction with standard ASCT consolidation, and the ability to replace the need for ASCT. The TRIANGLE results were presented by Dr. Martin Dreyling in the Plenary Session at the December 2022 American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting. Transplant-eligible MCL patients < 65 years of age were randomized to the EMCL’s established front-line therapy of alternating R-CHOP/R-DHAP plus ASCT; the same regimen plus oral ibrutinib given with the R-CHOP induction cycles and then post-ASCT ibrutinib maintenance therapy for 2 years (Arm A+I); or the A+I regimen minus ASCT (Arm I). Maintenance rituximab was allowed in each arm, on the basis of the treating centers’ institutional guidelines. Overall, 54%-58% of patients in each study arm received rituximab maintenance, with no differential benefit in efficacy noted for those so treated.

The results showed that 94%-98% of patients responded by the end of induction (defined as R-chemo and ASCT), with complete remissions in 36%-45% (from computerized tomography imaging, not PET scan). With a median follow-up of 31 months, failure-free survival (FFS; the primary study endpoint) was significantly improved for A+I vs A (3 year FFS of 88% vs 72%, respectively; p = 0.0008). In a subgroup analysis, FFS was notably improved for A+I in patients with high-level TP53 overexpression by immunohistochemistry. Toxicity did not differ during the induction and ASCT periods among the 3 arms regarding cytopenia, gastrointestinal disorders, and infections. However, neutropenia and infections were increased in the ibrutinib-containing arms during maintenance therapy—especially for Arm A+I.

The authors concluded that ASCT plus ibrutinib (Arm A+I) is superior to ASCT only (Arm A), and that Arm A is not superior to ibrutinib without ASCT (Arm I). No decision can yet be made regarding A+I versus I for which FFS to date remains very similar; however, the authors favor ibrutinib without ASCT due to lower toxicity. OS is trending to favor the ibrutinib arms, but longer follow-up will be needed to fully assess.

Should ASCT consolidation now be replaced by ibrutinib-containing induction R-CHOP/R-DHAP and maintenance ibrutinib, with or without maintenance rituximab? A definitive answer will require the fully-published TRIANGLE results, as well as ongoing analysis with longer follow-up. However, it seems very likely that ASCT indeed will be replaced by the new approach. TP53-mutated MCL should be treated with ibrutinib plus R-CHOP/R-DHAP and ibrutinib maintenance as validated in this trial.

Many centers have begun using a second-generation BTKi, acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib, rather than ibrutinib due to equivalent response rates with more favorable side effect profiles and fewer treatment discontinuations. Caution is warranted regarding simply adding a BTKi to one’s favored MCL induction regimen and foregoing ASCT—pending additional studies and the safety of such alternative approaches.

These are indeed exciting times of therapeutic progress, as they have been improving outcomes and providing longer survival outcomes for MCL patients. Targeted agents facilitate this shift to less intensive and chemotherapy-free regimens that provide enhanced response and mitigate short- and longer-term toxicities. More results will be forthcoming for MRD as a treatment endpoint, guiding maintenance therapy, and for risk-adapted treatment of newly-diagnosed and relapsing patients (based upon MCL subtype and biomarker profiles). Enrolling patients into clinical trials is strongly encouraged as the best mechanism to help answer emerging questions in the field and open the pathway to continued progress.

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) has served as a paradigm of progress among the non-Hodgkin lymphomas over the past 30 years. It was originally defined within the Kiel classification as centrocytic lymphoma, then renamed MCL once the characteristic translocation and resulting cyclin D1 overexpression were identified. These diagnostic markers allowed for the characterization of MCL subtypes as well as the initiation of MCL-focused clinical trials which, in turn, led to regulatory approval of more effective regimens, new therapeutic agents, and an improvement in overall survival (OS) from around 3 years to more than 10 years for many patients.

Despite this progress, virtually all patients relapse, and a cure remains elusive for most. In younger (< 65 to 70 years), medically-fit patients who are transplant-eligible and have symptomatic MCL, a standard of care has been induction chemoimmunotherapy containing high-dose cytarabine followed by ASCT consolidation. For example, a clinical trial of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) alternating with R-DHAP (rituximab, dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, cisplatin; 3 cycles each) showed a significant benefit over R-CHOP x 6 cycles; at a median follow-up of 10.6 years, the time-to-treatment failure was 8.4 v 3.9 years. In another trial, all patients received induction R-DHAP (with cisplatin or an alternative platinum agent) x 4 cycles followed by ASCT. Those patients randomized to post-ASCT maintenance rituximab for 3 years had significantly improved, 4-year progression-free survival (PFS) as compared with observation only (83% vs 64%, p < 0.001); maintenance also significantly improved OS.

Although ASCT consolidation followed by maintenance became widely adopted on the basis of these and other clinical trials, important questions remain:

First, MCL is biologically and clinically quite heterogeneous. Several prognostic tools such as the MCL International Prognostic Index (MIPI) scoring system and biomarkers are available to define lower- versus higher-risk subtypes, but none is routinely used for treatment planning. About 15% of MCL patients present with a highly-aggressive blastoid or pleomorphic variant that usually carries a TP53 mutation or deletion. Given the short survival and limited benefit from dose-intensive chemotherapy and ASCT in TP53-mutated MCL, should transplant be avoided in these patients?

Second, if deep remission is achieved following front-line therapy, defined as positron emission tomography (PET) negative and measurable residual disease (MRD) negative, will high-dose chemotherapy and ASCT provide additional benefits or only toxicity? This question is being addressed by the ongoing ECOG 4151 study, a risk-adapted trial in which post-induction MRD-negative patients are randomized to standard ASCT consolidation plus maintenance rituximab vs maintenance only.

Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (BTKi) are now among the most used agents for relapsed MCL. Recent clinical trials testing the integration of a BTKi into first- or second-line therapy have shown increased response rates and variable clinical outcomes and toxicities for the combinations, depending upon the chemotherapy- and non-chemotherapy backbones utilized, as well as the BTKi. Combinations with the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax plus chemotherapy or BTKi are also showing promise.

The activity of BTKi in MCL led the European MCL Network (EMCL) to design the 3-arm TRIANGLE study to analyze the potential of ibrutinib to improve outcomes when given in conjunction with standard ASCT consolidation, and the ability to replace the need for ASCT. The TRIANGLE results were presented by Dr. Martin Dreyling in the Plenary Session at the December 2022 American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting. Transplant-eligible MCL patients < 65 years of age were randomized to the EMCL’s established front-line therapy of alternating R-CHOP/R-DHAP plus ASCT; the same regimen plus oral ibrutinib given with the R-CHOP induction cycles and then post-ASCT ibrutinib maintenance therapy for 2 years (Arm A+I); or the A+I regimen minus ASCT (Arm I). Maintenance rituximab was allowed in each arm, on the basis of the treating centers’ institutional guidelines. Overall, 54%-58% of patients in each study arm received rituximab maintenance, with no differential benefit in efficacy noted for those so treated.

The results showed that 94%-98% of patients responded by the end of induction (defined as R-chemo and ASCT), with complete remissions in 36%-45% (from computerized tomography imaging, not PET scan). With a median follow-up of 31 months, failure-free survival (FFS; the primary study endpoint) was significantly improved for A+I vs A (3 year FFS of 88% vs 72%, respectively; p = 0.0008). In a subgroup analysis, FFS was notably improved for A+I in patients with high-level TP53 overexpression by immunohistochemistry. Toxicity did not differ during the induction and ASCT periods among the 3 arms regarding cytopenia, gastrointestinal disorders, and infections. However, neutropenia and infections were increased in the ibrutinib-containing arms during maintenance therapy—especially for Arm A+I.

The authors concluded that ASCT plus ibrutinib (Arm A+I) is superior to ASCT only (Arm A), and that Arm A is not superior to ibrutinib without ASCT (Arm I). No decision can yet be made regarding A+I versus I for which FFS to date remains very similar; however, the authors favor ibrutinib without ASCT due to lower toxicity. OS is trending to favor the ibrutinib arms, but longer follow-up will be needed to fully assess.

Should ASCT consolidation now be replaced by ibrutinib-containing induction R-CHOP/R-DHAP and maintenance ibrutinib, with or without maintenance rituximab? A definitive answer will require the fully-published TRIANGLE results, as well as ongoing analysis with longer follow-up. However, it seems very likely that ASCT indeed will be replaced by the new approach. TP53-mutated MCL should be treated with ibrutinib plus R-CHOP/R-DHAP and ibrutinib maintenance as validated in this trial.

Many centers have begun using a second-generation BTKi, acalabrutinib or zanubrutinib, rather than ibrutinib due to equivalent response rates with more favorable side effect profiles and fewer treatment discontinuations. Caution is warranted regarding simply adding a BTKi to one’s favored MCL induction regimen and foregoing ASCT—pending additional studies and the safety of such alternative approaches.

These are indeed exciting times of therapeutic progress, as they have been improving outcomes and providing longer survival outcomes for MCL patients. Targeted agents facilitate this shift to less intensive and chemotherapy-free regimens that provide enhanced response and mitigate short- and longer-term toxicities. More results will be forthcoming for MRD as a treatment endpoint, guiding maintenance therapy, and for risk-adapted treatment of newly-diagnosed and relapsing patients (based upon MCL subtype and biomarker profiles). Enrolling patients into clinical trials is strongly encouraged as the best mechanism to help answer emerging questions in the field and open the pathway to continued progress.

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) has served as a paradigm of progress among the non-Hodgkin lymphomas over the past 30 years. It was originally defined within the Kiel classification as centrocytic lymphoma, then renamed MCL once the characteristic translocation and resulting cyclin D1 overexpression were identified. These diagnostic markers allowed for the characterization of MCL subtypes as well as the initiation of MCL-focused clinical trials which, in turn, led to regulatory approval of more effective regimens, new therapeutic agents, and an improvement in overall survival (OS) from around 3 years to more than 10 years for many patients.

Despite this progress, virtually all patients relapse, and a cure remains elusive for most. In younger (< 65 to 70 years), medically-fit patients who are transplant-eligible and have symptomatic MCL, a standard of care has been induction chemoimmunotherapy containing high-dose cytarabine followed by ASCT consolidation. For example, a clinical trial of R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) alternating with R-DHAP (rituximab, dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, cisplatin; 3 cycles each) showed a significant benefit over R-CHOP x 6 cycles; at a median follow-up of 10.6 years, the time-to-treatment failure was 8.4 v 3.9 years. In another trial, all patients received induction R-DHAP (with cisplatin or an alternative platinum agent) x 4 cycles followed by ASCT. Those patients randomized to post-ASCT maintenance rituximab for 3 years had significantly improved, 4-year progression-free survival (PFS) as compared with observation only (83% vs 64%, p < 0.001); maintenance also significantly improved OS.

Although ASCT consolidation followed by maintenance became widely adopted on the basis of these and other clinical trials, important questions remain:

First, MCL is biologically and clinically quite heterogeneous. Several prognostic tools such as the MCL International Prognostic Index (MIPI) scoring system and biomarkers are available to define lower- versus higher-risk subtypes, but none is routinely used for treatment planning. About 15% of MCL patients present with a highly-aggressive blastoid or pleomorphic variant that usually carries a TP53 mutation or deletion. Given the short survival and limited benefit from dose-intensive chemotherapy and ASCT in TP53-mutated MCL, should transplant be avoided in these patients?

Second, if deep remission is achieved following front-line therapy, defined as positron emission tomography (PET) negative and measurable residual disease (MRD) negative, will high-dose chemotherapy and ASCT provide additional benefits or only toxicity? This question is being addressed by the ongoing ECOG 4151 study, a risk-adapted trial in which post-induction MRD-negative patients are randomized to standard ASCT consolidation plus maintenance rituximab vs maintenance only.

Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (BTKi) are now among the most used agents for relapsed MCL. Recent clinical trials testing the integration of a BTKi into first- or second-line therapy have shown increased response rates and variable clinical outcomes and toxicities for the combinations, depending upon the chemotherapy- and non-chemotherapy backbones utilized, as well as the BTKi. Combinations with the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax plus chemotherapy or BTKi are also showing promise.

The activity of BTKi in MCL led the European MCL Network (EMCL) to design the 3-arm TRIANGLE study to analyze the potential of ibrutinib to improve outcomes when given in conjunction with standard ASCT consolidation, and the ability to replace the need for ASCT. The TRIANGLE results were presented by Dr. Martin Dreyling in the Plenary Session at the December 2022 American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting. Transplant-eligible MCL patients < 65 years of age were randomized to the EMCL’s established front-line therapy of alternating R-CHOP/R-DHAP plus ASCT; the same regimen plus oral ibrutinib given with the R-CHOP induction cycles and then post-ASCT ibrutinib maintenance therapy for 2 years (Arm A+I); or the A+I regimen minus ASCT (Arm I). Maintenance rituximab was allowed in each arm, on the basis of the treating centers’ institutional guidelines. Overall, 54%-58% of patients in each study arm received rituximab maintenance, with no differential benefit in efficacy noted for those so treated.

The results showed that 94%-98% of patients responded by the end of induction (defined as R-chemo and ASCT), with complete remissions in 36%-45% (from computerized tomography imaging, not PET scan). With a median follow-up of 31 months, failure-free survival (FFS; the primary study endpoint) was significantly improved for A+I vs A (3 year FFS of 88% vs 72%, respectively; p = 0.0008). In a subgroup analysis, FFS was notably improved for A+I in patients with high-level TP53 overexpression by immunohistochemistry. Toxicity did not differ during the induction and ASCT periods among the 3 arms regarding cytopenia, gastrointestinal disorders, and infections. However, neutropenia and infections were increased in the ibrutinib-containing arms during maintenance therapy—especially for Arm A+I.

The authors concluded that ASCT plus ibrutinib (Arm A+I) is superior to ASCT only (Arm A), and that Arm A is not superior to ibrutinib without ASCT (Arm I). No decision can yet be made regarding A+I versus I for which FFS to date remains very similar; however, the authors favor ibrutinib without ASCT due to lower toxicity. OS is trending to favor the ibrutinib arms, but longer follow-up will be needed to fully assess.

Should ASCT consolidation now be replaced by ibrutinib-containing induction R-CHOP/R-DHAP and maintenance ibrutinib, with or without maintenance rituximab? A definitive answer will require the fully-published TRIANGLE results, as well as ongoing analysis with longer follow-up. However, it seems very likely that ASCT indeed will be replaced by the new approach. TP53-mutated MCL should be treated with ibrutinib plus R-CHOP/R-DHAP and ibrutinib maintenance as validated in this trial.