User login

mAb granted breakthrough designation for MM

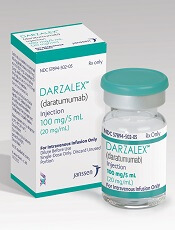

Photo courtesy of Janssen

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted breakthrough therapy designation for daratumumab (Darzalex), a CD38-directed monoclonal antibody (mAb), as part of combination therapy for patients with multiple myeloma (MM).

The designation is for daratumumab in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone or bortezomib and dexamethasone for the treatment of MM patients who have received at least 1 prior therapy.

This is the second breakthrough designation the FDA has granted to daratumumab.

The FDA’s breakthrough designation is intended to expedite the development and review of new therapies for serious or life-threatening conditions.

To earn the designation, a treatment must show encouraging early clinical results demonstrating substantial improvement over available therapies with regard to a clinically significant endpoint, or it must fulfill an unmet need.

In May 2013, the FDA granted daratumumab breakthrough designation for the treatment of MM patients who have received at least 3 prior lines of therapy, including a proteasome inhibitor and an immunomodulatory agent, or who are double-refractory to a proteasome inhibitor and an immunomodulatory agent.

In November 2015, daratumumab received accelerated approval from the FDA for this indication. Continued approval of the mAb may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in a confirmatory trial.

Phase 3 trials

The newest breakthrough designation for daratumumab was based on data from two phase 3 studies—CASTOR (MMY3004) and POLLUX (MMY3003). Both studies were sponsored by Janssen Biotech, Inc., the company developing daratumumab.

In the CASTOR trial, researchers compared daratumumab-bortezomib-dexamethasone to bortezomib-dexamethasone in MM patients who had received at least 1 prior therapy.

The researchers said the addition of daratumumab significantly improved progression-free survival without increasing the cumulative toxicity or the toxicity of the bortezomib-dexamethasone combination.

Results from this trial were presented at the 2016 ASCO Annual Meeting.

In the POLLUX trial, researchers compared daratumumab-lenalidomide-dexamethasone to lenalidomide-dexamethasone in MM patients who had received at least 1 prior therapy.

According to the researchers, daratumumab-lenalidomide-dexamethasone conferred the highest response rate reported to date in the treatment of relapsed/refractory MM, significantly improved progression-free survival compared to lenalidomide-dexamethasone, and had a manageable safety profile.

These results were presented at the 21st Congress of the European Hematology Association. ![]()

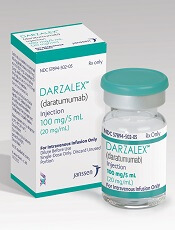

Photo courtesy of Janssen

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted breakthrough therapy designation for daratumumab (Darzalex), a CD38-directed monoclonal antibody (mAb), as part of combination therapy for patients with multiple myeloma (MM).

The designation is for daratumumab in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone or bortezomib and dexamethasone for the treatment of MM patients who have received at least 1 prior therapy.

This is the second breakthrough designation the FDA has granted to daratumumab.

The FDA’s breakthrough designation is intended to expedite the development and review of new therapies for serious or life-threatening conditions.

To earn the designation, a treatment must show encouraging early clinical results demonstrating substantial improvement over available therapies with regard to a clinically significant endpoint, or it must fulfill an unmet need.

In May 2013, the FDA granted daratumumab breakthrough designation for the treatment of MM patients who have received at least 3 prior lines of therapy, including a proteasome inhibitor and an immunomodulatory agent, or who are double-refractory to a proteasome inhibitor and an immunomodulatory agent.

In November 2015, daratumumab received accelerated approval from the FDA for this indication. Continued approval of the mAb may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in a confirmatory trial.

Phase 3 trials

The newest breakthrough designation for daratumumab was based on data from two phase 3 studies—CASTOR (MMY3004) and POLLUX (MMY3003). Both studies were sponsored by Janssen Biotech, Inc., the company developing daratumumab.

In the CASTOR trial, researchers compared daratumumab-bortezomib-dexamethasone to bortezomib-dexamethasone in MM patients who had received at least 1 prior therapy.

The researchers said the addition of daratumumab significantly improved progression-free survival without increasing the cumulative toxicity or the toxicity of the bortezomib-dexamethasone combination.

Results from this trial were presented at the 2016 ASCO Annual Meeting.

In the POLLUX trial, researchers compared daratumumab-lenalidomide-dexamethasone to lenalidomide-dexamethasone in MM patients who had received at least 1 prior therapy.

According to the researchers, daratumumab-lenalidomide-dexamethasone conferred the highest response rate reported to date in the treatment of relapsed/refractory MM, significantly improved progression-free survival compared to lenalidomide-dexamethasone, and had a manageable safety profile.

These results were presented at the 21st Congress of the European Hematology Association. ![]()

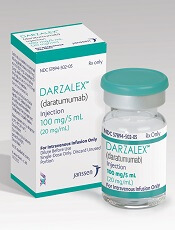

Photo courtesy of Janssen

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted breakthrough therapy designation for daratumumab (Darzalex), a CD38-directed monoclonal antibody (mAb), as part of combination therapy for patients with multiple myeloma (MM).

The designation is for daratumumab in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone or bortezomib and dexamethasone for the treatment of MM patients who have received at least 1 prior therapy.

This is the second breakthrough designation the FDA has granted to daratumumab.

The FDA’s breakthrough designation is intended to expedite the development and review of new therapies for serious or life-threatening conditions.

To earn the designation, a treatment must show encouraging early clinical results demonstrating substantial improvement over available therapies with regard to a clinically significant endpoint, or it must fulfill an unmet need.

In May 2013, the FDA granted daratumumab breakthrough designation for the treatment of MM patients who have received at least 3 prior lines of therapy, including a proteasome inhibitor and an immunomodulatory agent, or who are double-refractory to a proteasome inhibitor and an immunomodulatory agent.

In November 2015, daratumumab received accelerated approval from the FDA for this indication. Continued approval of the mAb may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in a confirmatory trial.

Phase 3 trials

The newest breakthrough designation for daratumumab was based on data from two phase 3 studies—CASTOR (MMY3004) and POLLUX (MMY3003). Both studies were sponsored by Janssen Biotech, Inc., the company developing daratumumab.

In the CASTOR trial, researchers compared daratumumab-bortezomib-dexamethasone to bortezomib-dexamethasone in MM patients who had received at least 1 prior therapy.

The researchers said the addition of daratumumab significantly improved progression-free survival without increasing the cumulative toxicity or the toxicity of the bortezomib-dexamethasone combination.

Results from this trial were presented at the 2016 ASCO Annual Meeting.

In the POLLUX trial, researchers compared daratumumab-lenalidomide-dexamethasone to lenalidomide-dexamethasone in MM patients who had received at least 1 prior therapy.

According to the researchers, daratumumab-lenalidomide-dexamethasone conferred the highest response rate reported to date in the treatment of relapsed/refractory MM, significantly improved progression-free survival compared to lenalidomide-dexamethasone, and had a manageable safety profile.

These results were presented at the 21st Congress of the European Hematology Association. ![]()

Blood disorders prove costly for European economy

chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Malignant and non-malignant blood disorders cost 31 European countries a total of €23 billion in 2012, according to a pair of papers published in The Lancet Haematology.

Healthcare costs accounted for €16 billion of the total costs, with €7 billion for hospital inpatient care and €4 billion for medications.

Informal care (from friends and relatives) cost €1.6 billion, productivity losses due to mortality cost €2.5 billion, and morbidity cost €3 billion.

Researchers determined these figures by analyzing data from international health organizations (WHO and EUROSTAT), as well as national ministries of health and statistical institutes.

The team estimated the economic burden of malignant and non-malignant blood disorders in 2012 for all 28 countries in the European Union (EU), as well as Iceland, Norway, and Switzerland.

The costs considered were healthcare costs (primary care, accident and emergency care, hospital inpatient and outpatient care, and drugs), informal care costs (from friends and relatives), and productivity losses (due to premature death and people being unable to work due to illness).

Malignant blood disorders

In one paper, the researchers noted that the total economic cost of blood cancers to the 31 countries studied was €12 billion in 2012. Healthcare costs measured €7.3 billion (62% of total costs), productivity losses cost €3.6 billion (30%), and informal care cost €1 billion (8%).

In the 28 EU countries, blood cancers represented 8% of the total cancer costs (€143 billion), meaning that blood cancers are the fourth most expensive type of cancer after lung (15%), breast (12%), and colorectal (10%) cancers.

When considering healthcare costs alone, blood cancers were second only to breast cancers (12% vs 13% of healthcare costs for all cancers).

In 2012, blood cancers cost, on average, €14,674 per patient in the EU (€15,126 in all 31 countries), which is almost 2 times higher than the average cost per patient across all cancers (€7929 in the EU).

The researchers said this difference may be due to the longer length of hospital stay observed for patients with blood cancers (14 days, on average, compared to 8 days across all cancers).

Another potential reason is that blood cancers are increasingly treated with complex, long-term treatments (including stem cell transplants, multi-agent chemotherapy, and radiotherapy) and diagnosed via extensive procedures.

The costs of blood cancers varied widely between the countries studied, but the reasons for this were unclear. For instance, the average healthcare costs in Finland were nearly twice as high as in Belgium (€18,014 vs €9596), despite both countries having similar national income per capita.

Non-malignant blood disorders

In the other paper, the researchers said the total economic cost of non-malignant blood disorders to the 31 countries studied was €11 billion in 2012. Healthcare costs accounted for €8 billion (75% of total costs), productivity losses for €2 billion (19%), and informal care for €618 million (6%).

Averaged across the population studied, non-malignant blood disorders represented an annual healthcare cost of €159 per 10 citizens.

“Non-malignant blood disorders cost the European economy nearly as much as all blood cancers combined,” said Jose Leal, DPhil, of the University of Oxford in the UK.

“We found wide differences in the cost of treating blood disorders in different countries, likely linked to the significant differences in the access and delivery of care for patients with blood disorders. Our findings suggest there is a need to harmonize care of blood disorders across Europe in a cost-effective way.” ![]()

chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Malignant and non-malignant blood disorders cost 31 European countries a total of €23 billion in 2012, according to a pair of papers published in The Lancet Haematology.

Healthcare costs accounted for €16 billion of the total costs, with €7 billion for hospital inpatient care and €4 billion for medications.

Informal care (from friends and relatives) cost €1.6 billion, productivity losses due to mortality cost €2.5 billion, and morbidity cost €3 billion.

Researchers determined these figures by analyzing data from international health organizations (WHO and EUROSTAT), as well as national ministries of health and statistical institutes.

The team estimated the economic burden of malignant and non-malignant blood disorders in 2012 for all 28 countries in the European Union (EU), as well as Iceland, Norway, and Switzerland.

The costs considered were healthcare costs (primary care, accident and emergency care, hospital inpatient and outpatient care, and drugs), informal care costs (from friends and relatives), and productivity losses (due to premature death and people being unable to work due to illness).

Malignant blood disorders

In one paper, the researchers noted that the total economic cost of blood cancers to the 31 countries studied was €12 billion in 2012. Healthcare costs measured €7.3 billion (62% of total costs), productivity losses cost €3.6 billion (30%), and informal care cost €1 billion (8%).

In the 28 EU countries, blood cancers represented 8% of the total cancer costs (€143 billion), meaning that blood cancers are the fourth most expensive type of cancer after lung (15%), breast (12%), and colorectal (10%) cancers.

When considering healthcare costs alone, blood cancers were second only to breast cancers (12% vs 13% of healthcare costs for all cancers).

In 2012, blood cancers cost, on average, €14,674 per patient in the EU (€15,126 in all 31 countries), which is almost 2 times higher than the average cost per patient across all cancers (€7929 in the EU).

The researchers said this difference may be due to the longer length of hospital stay observed for patients with blood cancers (14 days, on average, compared to 8 days across all cancers).

Another potential reason is that blood cancers are increasingly treated with complex, long-term treatments (including stem cell transplants, multi-agent chemotherapy, and radiotherapy) and diagnosed via extensive procedures.

The costs of blood cancers varied widely between the countries studied, but the reasons for this were unclear. For instance, the average healthcare costs in Finland were nearly twice as high as in Belgium (€18,014 vs €9596), despite both countries having similar national income per capita.

Non-malignant blood disorders

In the other paper, the researchers said the total economic cost of non-malignant blood disorders to the 31 countries studied was €11 billion in 2012. Healthcare costs accounted for €8 billion (75% of total costs), productivity losses for €2 billion (19%), and informal care for €618 million (6%).

Averaged across the population studied, non-malignant blood disorders represented an annual healthcare cost of €159 per 10 citizens.

“Non-malignant blood disorders cost the European economy nearly as much as all blood cancers combined,” said Jose Leal, DPhil, of the University of Oxford in the UK.

“We found wide differences in the cost of treating blood disorders in different countries, likely linked to the significant differences in the access and delivery of care for patients with blood disorders. Our findings suggest there is a need to harmonize care of blood disorders across Europe in a cost-effective way.” ![]()

chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

Malignant and non-malignant blood disorders cost 31 European countries a total of €23 billion in 2012, according to a pair of papers published in The Lancet Haematology.

Healthcare costs accounted for €16 billion of the total costs, with €7 billion for hospital inpatient care and €4 billion for medications.

Informal care (from friends and relatives) cost €1.6 billion, productivity losses due to mortality cost €2.5 billion, and morbidity cost €3 billion.

Researchers determined these figures by analyzing data from international health organizations (WHO and EUROSTAT), as well as national ministries of health and statistical institutes.

The team estimated the economic burden of malignant and non-malignant blood disorders in 2012 for all 28 countries in the European Union (EU), as well as Iceland, Norway, and Switzerland.

The costs considered were healthcare costs (primary care, accident and emergency care, hospital inpatient and outpatient care, and drugs), informal care costs (from friends and relatives), and productivity losses (due to premature death and people being unable to work due to illness).

Malignant blood disorders

In one paper, the researchers noted that the total economic cost of blood cancers to the 31 countries studied was €12 billion in 2012. Healthcare costs measured €7.3 billion (62% of total costs), productivity losses cost €3.6 billion (30%), and informal care cost €1 billion (8%).

In the 28 EU countries, blood cancers represented 8% of the total cancer costs (€143 billion), meaning that blood cancers are the fourth most expensive type of cancer after lung (15%), breast (12%), and colorectal (10%) cancers.

When considering healthcare costs alone, blood cancers were second only to breast cancers (12% vs 13% of healthcare costs for all cancers).

In 2012, blood cancers cost, on average, €14,674 per patient in the EU (€15,126 in all 31 countries), which is almost 2 times higher than the average cost per patient across all cancers (€7929 in the EU).

The researchers said this difference may be due to the longer length of hospital stay observed for patients with blood cancers (14 days, on average, compared to 8 days across all cancers).

Another potential reason is that blood cancers are increasingly treated with complex, long-term treatments (including stem cell transplants, multi-agent chemotherapy, and radiotherapy) and diagnosed via extensive procedures.

The costs of blood cancers varied widely between the countries studied, but the reasons for this were unclear. For instance, the average healthcare costs in Finland were nearly twice as high as in Belgium (€18,014 vs €9596), despite both countries having similar national income per capita.

Non-malignant blood disorders

In the other paper, the researchers said the total economic cost of non-malignant blood disorders to the 31 countries studied was €11 billion in 2012. Healthcare costs accounted for €8 billion (75% of total costs), productivity losses for €2 billion (19%), and informal care for €618 million (6%).

Averaged across the population studied, non-malignant blood disorders represented an annual healthcare cost of €159 per 10 citizens.

“Non-malignant blood disorders cost the European economy nearly as much as all blood cancers combined,” said Jose Leal, DPhil, of the University of Oxford in the UK.

“We found wide differences in the cost of treating blood disorders in different countries, likely linked to the significant differences in the access and delivery of care for patients with blood disorders. Our findings suggest there is a need to harmonize care of blood disorders across Europe in a cost-effective way.” ![]()

BTK inhibitor may treat ibrutinib-resistant cancers

Photo by Aaron Logan

KOLOA, HAWAII—Preclinical research suggests that ARQ 531, a reversible Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor, might prove effective against ibrutinib-resistant hematologic malignancies.

The study showed that ARQ 531 inhibits wild-type BTK and the ibrutinib-resistant BTK-C481S mutant with similar potency.

The compound also suppressed proliferation of hematologic cancer cells in vitro and inhibited tumor growth in a mouse model of B-cell lymphoma.

Researchers disclosed these results in a poster presentation at the 2016 Pan Pacific Lymphoma Conference. The research was supported by ArQule Inc., the company developing ARQ 531.

The researchers first demonstrated that ARQ 531 enacts biochemical inhibition of both wild-type and C481S-mutant BTK at sub-nanomolar levels and cellular inhibition in C481S-mutant BTK cells that are resistant to ibrutinib.

The team then tested ARQ 531 in a range of cell lines encompassing a variety of leukemias and lymphomas, as well as multiple myeloma.

They found that ARQ 531 can inhibit proliferation in many types of hematologic cancer cells, but it “potently inhibits” cell lines that are addicted to BCR, PI3K/AKT, and Notch signaling pathways.

The researchers also tested ARQ 531 in the BTK-driven TMD8 xenograft mouse model (B-cell lymphoma). They said the compound demonstrated strong target and pathway inhibition, with sustained tumor growth inhibition.

The team noted that ARQ 531 exhibits a distinct kinase selectivity profile, with strong inhibitory activity against several key oncogenic drivers from TEC, Trk, and Src family kinases. And the compound inhibits the RAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways.

The researchers said these results support further investigation of ARQ 531, particularly in the setting of ibrutinib resistance.

It is currently estimated that about 10% of patients treated with ibrutinib develop resistance, and more than 80% of these patients present with the C481S mutation.

“We are beginning to see increasing resistance to ibrutinib, which is creating the need for a BTK inhibitor, like ARQ 531, that targets the C481S mutation,” said Brian Schwartz, head of research and development and chief medical officer at ArQule.

“The preclinical profile of ARQ 531 as a potent and reversible inhibitor of wild-type and mutant BTK presents the potential for a first-in-class and best-in-class molecule. We are working toward completing GLP [good laboratory practice] toxicology studies and filing an IND [investigational new drug application] in early 2017.” ![]()

Photo by Aaron Logan

KOLOA, HAWAII—Preclinical research suggests that ARQ 531, a reversible Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor, might prove effective against ibrutinib-resistant hematologic malignancies.

The study showed that ARQ 531 inhibits wild-type BTK and the ibrutinib-resistant BTK-C481S mutant with similar potency.

The compound also suppressed proliferation of hematologic cancer cells in vitro and inhibited tumor growth in a mouse model of B-cell lymphoma.

Researchers disclosed these results in a poster presentation at the 2016 Pan Pacific Lymphoma Conference. The research was supported by ArQule Inc., the company developing ARQ 531.

The researchers first demonstrated that ARQ 531 enacts biochemical inhibition of both wild-type and C481S-mutant BTK at sub-nanomolar levels and cellular inhibition in C481S-mutant BTK cells that are resistant to ibrutinib.

The team then tested ARQ 531 in a range of cell lines encompassing a variety of leukemias and lymphomas, as well as multiple myeloma.

They found that ARQ 531 can inhibit proliferation in many types of hematologic cancer cells, but it “potently inhibits” cell lines that are addicted to BCR, PI3K/AKT, and Notch signaling pathways.

The researchers also tested ARQ 531 in the BTK-driven TMD8 xenograft mouse model (B-cell lymphoma). They said the compound demonstrated strong target and pathway inhibition, with sustained tumor growth inhibition.

The team noted that ARQ 531 exhibits a distinct kinase selectivity profile, with strong inhibitory activity against several key oncogenic drivers from TEC, Trk, and Src family kinases. And the compound inhibits the RAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways.

The researchers said these results support further investigation of ARQ 531, particularly in the setting of ibrutinib resistance.

It is currently estimated that about 10% of patients treated with ibrutinib develop resistance, and more than 80% of these patients present with the C481S mutation.

“We are beginning to see increasing resistance to ibrutinib, which is creating the need for a BTK inhibitor, like ARQ 531, that targets the C481S mutation,” said Brian Schwartz, head of research and development and chief medical officer at ArQule.

“The preclinical profile of ARQ 531 as a potent and reversible inhibitor of wild-type and mutant BTK presents the potential for a first-in-class and best-in-class molecule. We are working toward completing GLP [good laboratory practice] toxicology studies and filing an IND [investigational new drug application] in early 2017.” ![]()

Photo by Aaron Logan

KOLOA, HAWAII—Preclinical research suggests that ARQ 531, a reversible Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor, might prove effective against ibrutinib-resistant hematologic malignancies.

The study showed that ARQ 531 inhibits wild-type BTK and the ibrutinib-resistant BTK-C481S mutant with similar potency.

The compound also suppressed proliferation of hematologic cancer cells in vitro and inhibited tumor growth in a mouse model of B-cell lymphoma.

Researchers disclosed these results in a poster presentation at the 2016 Pan Pacific Lymphoma Conference. The research was supported by ArQule Inc., the company developing ARQ 531.

The researchers first demonstrated that ARQ 531 enacts biochemical inhibition of both wild-type and C481S-mutant BTK at sub-nanomolar levels and cellular inhibition in C481S-mutant BTK cells that are resistant to ibrutinib.

The team then tested ARQ 531 in a range of cell lines encompassing a variety of leukemias and lymphomas, as well as multiple myeloma.

They found that ARQ 531 can inhibit proliferation in many types of hematologic cancer cells, but it “potently inhibits” cell lines that are addicted to BCR, PI3K/AKT, and Notch signaling pathways.

The researchers also tested ARQ 531 in the BTK-driven TMD8 xenograft mouse model (B-cell lymphoma). They said the compound demonstrated strong target and pathway inhibition, with sustained tumor growth inhibition.

The team noted that ARQ 531 exhibits a distinct kinase selectivity profile, with strong inhibitory activity against several key oncogenic drivers from TEC, Trk, and Src family kinases. And the compound inhibits the RAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways.

The researchers said these results support further investigation of ARQ 531, particularly in the setting of ibrutinib resistance.

It is currently estimated that about 10% of patients treated with ibrutinib develop resistance, and more than 80% of these patients present with the C481S mutation.

“We are beginning to see increasing resistance to ibrutinib, which is creating the need for a BTK inhibitor, like ARQ 531, that targets the C481S mutation,” said Brian Schwartz, head of research and development and chief medical officer at ArQule.

“The preclinical profile of ARQ 531 as a potent and reversible inhibitor of wild-type and mutant BTK presents the potential for a first-in-class and best-in-class molecule. We are working toward completing GLP [good laboratory practice] toxicology studies and filing an IND [investigational new drug application] in early 2017.” ![]()

Cancer patients and docs disagree about prognosis

patient and her father

Photo by Rhoda Baer

In a survey of advanced cancer patients and their oncologists, differing opinions about prognosis were common.

And the vast majority of patients didn’t know their doctors held different opinions about how long the patients might live.

Results of the survey were published in JAMA Oncology.

“We’ve discovered 2 important things happening between oncologists and patients with advanced cancer,” said study author Ronald M. Epstein, MD, of the University of Rochester Medical Center in Rochester, New York.

“First, some patients might know the doctor’s prognosis estimate, but the patient chooses to disagree, often because they believe other sources. And, second, some patients think that their doctor agrees with their opinion about prognosis but, in fact, the doctor doesn’t.”

Dr Epstein and his colleagues surveyed 236 patients with stage 3 or 4 cancer. According to medical evidence, fewer than 5% of these patients would be expected to live for 5 years.

The 38 oncologists who treated these patients were also surveyed. The doctors were asked,“What do you believe are the chances that this patient will live for 2 years or more?” And the patients were asked, “What do you believe are the chances that you will live for 2 years or more?”

Additional survey questions gauged whether patients knew their prognosis opinions differed from their doctors and to what extent treatment options were discussed in the context of life expectancy.

Among the 236 patients, 68% rated their survival prognosis differently than their oncologists, and 89% of these patients did not realize their opinions differed from their oncologists. In nearly all cases (96%), the patients were more optimistic than their doctors.

“Of course, it’s only possible for doctors to provide a ball-park estimate about life expectancy, and some people do beat the odds,” Dr Epstein noted. “But when a patient with very advanced cancer says that he has a 90% to 100% chance of being alive in 2 years and his oncologist believes that chance is more like 10%, there’s a problem.”

The challenge, according to Dr Epstein and his colleagues, is that talking about a cancer prognosis is not a straightforward exchange of information. It occurs in the context of fear, confusion, and uncertainty.

The researchers said prognosis should be addressed in several conversations about personal values and treatment goals. When doctor-patient communication is poor, it can result in mutual regret about end-of-life circumstances.

For example, nearly all of the patients surveyed said they wanted to be involved in treatment decisions. And 70% said they preferred supportive care at the end of their lives as opposed to aggressive therapy. However, as the researchers pointed out, making an informed decision requires knowing when death is approaching.

“When people think they’ll live a very long time with cancer, despite evidence to the contrary, they may end up taking more aggressive chemotherapy and agreeing to be placed on ventilators or dialysis, paradoxically reducing their quality of life, keeping them from enjoying time with family, and sometimes even shortening their lives,” Dr Epstein said. “So it’s very important for doctors and patients to be on the same page.” ![]()

patient and her father

Photo by Rhoda Baer

In a survey of advanced cancer patients and their oncologists, differing opinions about prognosis were common.

And the vast majority of patients didn’t know their doctors held different opinions about how long the patients might live.

Results of the survey were published in JAMA Oncology.

“We’ve discovered 2 important things happening between oncologists and patients with advanced cancer,” said study author Ronald M. Epstein, MD, of the University of Rochester Medical Center in Rochester, New York.

“First, some patients might know the doctor’s prognosis estimate, but the patient chooses to disagree, often because they believe other sources. And, second, some patients think that their doctor agrees with their opinion about prognosis but, in fact, the doctor doesn’t.”

Dr Epstein and his colleagues surveyed 236 patients with stage 3 or 4 cancer. According to medical evidence, fewer than 5% of these patients would be expected to live for 5 years.

The 38 oncologists who treated these patients were also surveyed. The doctors were asked,“What do you believe are the chances that this patient will live for 2 years or more?” And the patients were asked, “What do you believe are the chances that you will live for 2 years or more?”

Additional survey questions gauged whether patients knew their prognosis opinions differed from their doctors and to what extent treatment options were discussed in the context of life expectancy.

Among the 236 patients, 68% rated their survival prognosis differently than their oncologists, and 89% of these patients did not realize their opinions differed from their oncologists. In nearly all cases (96%), the patients were more optimistic than their doctors.

“Of course, it’s only possible for doctors to provide a ball-park estimate about life expectancy, and some people do beat the odds,” Dr Epstein noted. “But when a patient with very advanced cancer says that he has a 90% to 100% chance of being alive in 2 years and his oncologist believes that chance is more like 10%, there’s a problem.”

The challenge, according to Dr Epstein and his colleagues, is that talking about a cancer prognosis is not a straightforward exchange of information. It occurs in the context of fear, confusion, and uncertainty.

The researchers said prognosis should be addressed in several conversations about personal values and treatment goals. When doctor-patient communication is poor, it can result in mutual regret about end-of-life circumstances.

For example, nearly all of the patients surveyed said they wanted to be involved in treatment decisions. And 70% said they preferred supportive care at the end of their lives as opposed to aggressive therapy. However, as the researchers pointed out, making an informed decision requires knowing when death is approaching.

“When people think they’ll live a very long time with cancer, despite evidence to the contrary, they may end up taking more aggressive chemotherapy and agreeing to be placed on ventilators or dialysis, paradoxically reducing their quality of life, keeping them from enjoying time with family, and sometimes even shortening their lives,” Dr Epstein said. “So it’s very important for doctors and patients to be on the same page.” ![]()

patient and her father

Photo by Rhoda Baer

In a survey of advanced cancer patients and their oncologists, differing opinions about prognosis were common.

And the vast majority of patients didn’t know their doctors held different opinions about how long the patients might live.

Results of the survey were published in JAMA Oncology.

“We’ve discovered 2 important things happening between oncologists and patients with advanced cancer,” said study author Ronald M. Epstein, MD, of the University of Rochester Medical Center in Rochester, New York.

“First, some patients might know the doctor’s prognosis estimate, but the patient chooses to disagree, often because they believe other sources. And, second, some patients think that their doctor agrees with their opinion about prognosis but, in fact, the doctor doesn’t.”

Dr Epstein and his colleagues surveyed 236 patients with stage 3 or 4 cancer. According to medical evidence, fewer than 5% of these patients would be expected to live for 5 years.

The 38 oncologists who treated these patients were also surveyed. The doctors were asked,“What do you believe are the chances that this patient will live for 2 years or more?” And the patients were asked, “What do you believe are the chances that you will live for 2 years or more?”

Additional survey questions gauged whether patients knew their prognosis opinions differed from their doctors and to what extent treatment options were discussed in the context of life expectancy.

Among the 236 patients, 68% rated their survival prognosis differently than their oncologists, and 89% of these patients did not realize their opinions differed from their oncologists. In nearly all cases (96%), the patients were more optimistic than their doctors.

“Of course, it’s only possible for doctors to provide a ball-park estimate about life expectancy, and some people do beat the odds,” Dr Epstein noted. “But when a patient with very advanced cancer says that he has a 90% to 100% chance of being alive in 2 years and his oncologist believes that chance is more like 10%, there’s a problem.”

The challenge, according to Dr Epstein and his colleagues, is that talking about a cancer prognosis is not a straightforward exchange of information. It occurs in the context of fear, confusion, and uncertainty.

The researchers said prognosis should be addressed in several conversations about personal values and treatment goals. When doctor-patient communication is poor, it can result in mutual regret about end-of-life circumstances.

For example, nearly all of the patients surveyed said they wanted to be involved in treatment decisions. And 70% said they preferred supportive care at the end of their lives as opposed to aggressive therapy. However, as the researchers pointed out, making an informed decision requires knowing when death is approaching.

“When people think they’ll live a very long time with cancer, despite evidence to the contrary, they may end up taking more aggressive chemotherapy and agreeing to be placed on ventilators or dialysis, paradoxically reducing their quality of life, keeping them from enjoying time with family, and sometimes even shortening their lives,” Dr Epstein said. “So it’s very important for doctors and patients to be on the same page.” ![]()

Weight loss lowers levels of cancer-associated proteins

A study of more than 400 women suggests that losing weight can reduce levels of cancer-promoting proteins in the blood.

Overweight or obese women who lost weight over a 12-month period—through diet alone or both diet and exercise—significantly lowered their levels of proteins that play a role in angiogenesis.

Researchers say this finding suggests that losing weight might help reduce the risk of developing certain cancers.

“We know that being overweight and having a sedentary lifestyle is associated with an increase in risk for developing certain types of cancer,” said Catherine Duggan, PhD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington.

“However, we don’t know exactly why. We wanted to investigate how levels of some biomarkers associated with angiogenesis were altered when overweight, sedentary, postmenopausal women enrolled in a research study lost weight and/or became physically active over the course of a year.”

Dr Duggan and her colleagues described this investigation in Cancer Research.

The team studied 439 women who were postmenopausal and overweight or obese but were otherwise healthy and ranged in age from 50 to 75.

The women were randomized to 1 of 4 study arms:

- A diet arm, in which women restricted their calorie intake to no more than 2000 kcal per day that included less than 30% of fat calories

- An aerobic exercise arm, in which women performed 45 minutes of moderate to vigorous exercise 5 days a week

- A combined diet and exercise arm

- A control arm.

The researchers collected blood samples at baseline and at 12 months, measuring levels of the angiogenesis-related proteins VEGF, PAI-1, and PEDF.

They also measured weight loss at 12 months and found that women in all 3 intervention arms had a significantly higher mean weight loss than women in the control arm.

The mean weight loss was 0.8% of body weight for women in the control arm, 2.4% for women in the exercise arm (P=0.03), 8.5% for women in the diet arm (P<0.001), and 10.8% for women in the diet and exercise arm (P<0.001).

Compared with women in the control arm, those in the diet-only arm and the diet and exercise arm had significantly lower levels of the angiogenesis-related proteins at 12 months. However, such effects were not apparent among women in the exercise-only arm.

Specifically, women in the diet and exercise arm had a significantly greater reduction in PAI-1 at 12 months than women in the control arm (-19.3% and +3.48%, respectively, P<0.0001).

Women in the diet-only arm and the diet and exercise arm had significantly greater reductions in PEDF than controls (-9.20%, -9.90%, and +0.18%, respectively, both P<0.0001).

And women in the diet-only arm (-8.25%, P=0.0005) and the diet and exercise arm (-9.98%, P<0.0001) had significantly greater reductions in VEGF than controls (-1.21%).

The researchers also observed a linear trend in the reductions. So the more weight loss the women experienced, the greater the reduction in angiogenesis-related protein levels.

“Our study shows that weight loss is a safe and effective method of improving the angiogenic profile in healthy individuals,” Dr Duggan said. “We were surprised by the magnitude of change in these biomarkers with weight loss.”

“While we can’t say for certain that reducing the circulating levels of angiogenic factors through weight loss would impact the growth of tumors, it is possible that they might be associated with a less favorable milieu for tumor growth and proliferation.”

Dr Duggan and her colleagues said limitations of this study include the fact that the researchers only measured 3 angiogenic factors and did not measure them in adipose or other tissues. ![]()

A study of more than 400 women suggests that losing weight can reduce levels of cancer-promoting proteins in the blood.

Overweight or obese women who lost weight over a 12-month period—through diet alone or both diet and exercise—significantly lowered their levels of proteins that play a role in angiogenesis.

Researchers say this finding suggests that losing weight might help reduce the risk of developing certain cancers.

“We know that being overweight and having a sedentary lifestyle is associated with an increase in risk for developing certain types of cancer,” said Catherine Duggan, PhD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington.

“However, we don’t know exactly why. We wanted to investigate how levels of some biomarkers associated with angiogenesis were altered when overweight, sedentary, postmenopausal women enrolled in a research study lost weight and/or became physically active over the course of a year.”

Dr Duggan and her colleagues described this investigation in Cancer Research.

The team studied 439 women who were postmenopausal and overweight or obese but were otherwise healthy and ranged in age from 50 to 75.

The women were randomized to 1 of 4 study arms:

- A diet arm, in which women restricted their calorie intake to no more than 2000 kcal per day that included less than 30% of fat calories

- An aerobic exercise arm, in which women performed 45 minutes of moderate to vigorous exercise 5 days a week

- A combined diet and exercise arm

- A control arm.

The researchers collected blood samples at baseline and at 12 months, measuring levels of the angiogenesis-related proteins VEGF, PAI-1, and PEDF.

They also measured weight loss at 12 months and found that women in all 3 intervention arms had a significantly higher mean weight loss than women in the control arm.

The mean weight loss was 0.8% of body weight for women in the control arm, 2.4% for women in the exercise arm (P=0.03), 8.5% for women in the diet arm (P<0.001), and 10.8% for women in the diet and exercise arm (P<0.001).

Compared with women in the control arm, those in the diet-only arm and the diet and exercise arm had significantly lower levels of the angiogenesis-related proteins at 12 months. However, such effects were not apparent among women in the exercise-only arm.

Specifically, women in the diet and exercise arm had a significantly greater reduction in PAI-1 at 12 months than women in the control arm (-19.3% and +3.48%, respectively, P<0.0001).

Women in the diet-only arm and the diet and exercise arm had significantly greater reductions in PEDF than controls (-9.20%, -9.90%, and +0.18%, respectively, both P<0.0001).

And women in the diet-only arm (-8.25%, P=0.0005) and the diet and exercise arm (-9.98%, P<0.0001) had significantly greater reductions in VEGF than controls (-1.21%).

The researchers also observed a linear trend in the reductions. So the more weight loss the women experienced, the greater the reduction in angiogenesis-related protein levels.

“Our study shows that weight loss is a safe and effective method of improving the angiogenic profile in healthy individuals,” Dr Duggan said. “We were surprised by the magnitude of change in these biomarkers with weight loss.”

“While we can’t say for certain that reducing the circulating levels of angiogenic factors through weight loss would impact the growth of tumors, it is possible that they might be associated with a less favorable milieu for tumor growth and proliferation.”

Dr Duggan and her colleagues said limitations of this study include the fact that the researchers only measured 3 angiogenic factors and did not measure them in adipose or other tissues. ![]()

A study of more than 400 women suggests that losing weight can reduce levels of cancer-promoting proteins in the blood.

Overweight or obese women who lost weight over a 12-month period—through diet alone or both diet and exercise—significantly lowered their levels of proteins that play a role in angiogenesis.

Researchers say this finding suggests that losing weight might help reduce the risk of developing certain cancers.

“We know that being overweight and having a sedentary lifestyle is associated with an increase in risk for developing certain types of cancer,” said Catherine Duggan, PhD, of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington.

“However, we don’t know exactly why. We wanted to investigate how levels of some biomarkers associated with angiogenesis were altered when overweight, sedentary, postmenopausal women enrolled in a research study lost weight and/or became physically active over the course of a year.”

Dr Duggan and her colleagues described this investigation in Cancer Research.

The team studied 439 women who were postmenopausal and overweight or obese but were otherwise healthy and ranged in age from 50 to 75.

The women were randomized to 1 of 4 study arms:

- A diet arm, in which women restricted their calorie intake to no more than 2000 kcal per day that included less than 30% of fat calories

- An aerobic exercise arm, in which women performed 45 minutes of moderate to vigorous exercise 5 days a week

- A combined diet and exercise arm

- A control arm.

The researchers collected blood samples at baseline and at 12 months, measuring levels of the angiogenesis-related proteins VEGF, PAI-1, and PEDF.

They also measured weight loss at 12 months and found that women in all 3 intervention arms had a significantly higher mean weight loss than women in the control arm.

The mean weight loss was 0.8% of body weight for women in the control arm, 2.4% for women in the exercise arm (P=0.03), 8.5% for women in the diet arm (P<0.001), and 10.8% for women in the diet and exercise arm (P<0.001).

Compared with women in the control arm, those in the diet-only arm and the diet and exercise arm had significantly lower levels of the angiogenesis-related proteins at 12 months. However, such effects were not apparent among women in the exercise-only arm.

Specifically, women in the diet and exercise arm had a significantly greater reduction in PAI-1 at 12 months than women in the control arm (-19.3% and +3.48%, respectively, P<0.0001).

Women in the diet-only arm and the diet and exercise arm had significantly greater reductions in PEDF than controls (-9.20%, -9.90%, and +0.18%, respectively, both P<0.0001).

And women in the diet-only arm (-8.25%, P=0.0005) and the diet and exercise arm (-9.98%, P<0.0001) had significantly greater reductions in VEGF than controls (-1.21%).

The researchers also observed a linear trend in the reductions. So the more weight loss the women experienced, the greater the reduction in angiogenesis-related protein levels.

“Our study shows that weight loss is a safe and effective method of improving the angiogenic profile in healthy individuals,” Dr Duggan said. “We were surprised by the magnitude of change in these biomarkers with weight loss.”

“While we can’t say for certain that reducing the circulating levels of angiogenic factors through weight loss would impact the growth of tumors, it is possible that they might be associated with a less favorable milieu for tumor growth and proliferation.”

Dr Duggan and her colleagues said limitations of this study include the fact that the researchers only measured 3 angiogenic factors and did not measure them in adipose or other tissues. ![]()

Immunotherapy may benefit relapsed HSCT recipients

Photo from Business Wire

Results of a phase 1 study suggest that repeated doses of the immunotherapy drug ipilimumab is a feasible treatment option for patients with hematologic diseases who relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Seven of the 28 patients studied responded to the treatment, but immune-mediated toxic effects and graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) occurred as well.

These results were published in NEJM.

Ipilimumab, which is already approved to treat unresectable or metastatic melanoma, works by blocking the immune checkpoint CTLA-4. Blockade of CTLA-4 has been shown to augment T-cell activation and proliferation.

“We believe [,in the case of relapse after HSCT,] the donor immune cells are present but can’t recognize the tumor cells because of inhibitory signals that disguise them,” said study author Matthew Davids, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts.

“By blocking the checkpoint, you allow the donor cells to see the cancer cells.”

Dr Davids and his colleagues tested this theory in 28 patients who had relapsed after allogeneic HSCT. The patients had acute myeloid leukemia (AML, n=12), Hodgkin lymphoma (n=7), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n=4), myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS, n=2), multiple myeloma (n=1), myeloproliferative neoplasm (n=1), or acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n=1).

Patients had received a median of 3 prior treatment regimens, excluding HSCT (range, 1 to 14), and 20 patients (71%) had received treatment for relapse after transplant. Eight patients (29%) previously had grade 1/2 acute GVHD, and 16 (57%) previously had chronic GVHD.

The median time from transplant to initial treatment with ipilimumab was 675 days (range, 198 to 1830), and the median time from relapse to initial treatment with ipilimumab was 97 days (range, 0 to

1415).

Patients received induction therapy with ipilimumab at a dose of 3 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg every 3 weeks for a total of 4 doses. Those who had a clinical benefit received additional doses every 12 weeks for up to 60 weeks.

Safety

Five patients discontinued ipilimumab due to dose-limiting toxic effects. Four of these patients had GVHD, and 1 had severe immune-related adverse events.

Dose-limiting GVHD presented as chronic GVHD of the liver in 3 patients and acute GVHD of the gut in 1 patient.

Immune-related adverse events included death (n=1), pneumonitis (2 grade 2 events, 1 grade 4 event), colitis (1 grade 3 event), immune thrombocytopenia (1 grade 2 event), and diarrhea (1 grade 2 event).

Efficacy

There were no responses in patients who received ipilimumab at 3 mg/kg. Among the 22 patients who received ipilimumab at 10 mg/kg, 5 had a complete response, and 2 had a partial response.

Six other patients did not qualify as having responses but had a decrease in their tumor burden. Altogether, ipilimumab reduced tumor burden in 59% of patients.

The complete responses occurred in 4 patients with extramedullary AML and 1 patient with MDS developing into AML. Two of the AML patients remained in complete response at 12 and 15 months, and the patient with MDS remained in complete response at 16 months.

At a median follow-up of 15 months (range, 8 to 27), the median duration of response had not been reached. Responses were associated with in situ infiltration of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, decreased activation of regulatory T cells, and expansion of subpopulations of effector T cells.

The 1-year overall survival rate was 49%.

The investigators said these encouraging results have set the stage for larger trials of checkpoint blockade in this patient population. Further research is planned to determine whether immunotherapy drugs could be given to high-risk patients to prevent relapse. ![]()

Photo from Business Wire

Results of a phase 1 study suggest that repeated doses of the immunotherapy drug ipilimumab is a feasible treatment option for patients with hematologic diseases who relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Seven of the 28 patients studied responded to the treatment, but immune-mediated toxic effects and graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) occurred as well.

These results were published in NEJM.

Ipilimumab, which is already approved to treat unresectable or metastatic melanoma, works by blocking the immune checkpoint CTLA-4. Blockade of CTLA-4 has been shown to augment T-cell activation and proliferation.

“We believe [,in the case of relapse after HSCT,] the donor immune cells are present but can’t recognize the tumor cells because of inhibitory signals that disguise them,” said study author Matthew Davids, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts.

“By blocking the checkpoint, you allow the donor cells to see the cancer cells.”

Dr Davids and his colleagues tested this theory in 28 patients who had relapsed after allogeneic HSCT. The patients had acute myeloid leukemia (AML, n=12), Hodgkin lymphoma (n=7), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n=4), myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS, n=2), multiple myeloma (n=1), myeloproliferative neoplasm (n=1), or acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n=1).

Patients had received a median of 3 prior treatment regimens, excluding HSCT (range, 1 to 14), and 20 patients (71%) had received treatment for relapse after transplant. Eight patients (29%) previously had grade 1/2 acute GVHD, and 16 (57%) previously had chronic GVHD.

The median time from transplant to initial treatment with ipilimumab was 675 days (range, 198 to 1830), and the median time from relapse to initial treatment with ipilimumab was 97 days (range, 0 to

1415).

Patients received induction therapy with ipilimumab at a dose of 3 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg every 3 weeks for a total of 4 doses. Those who had a clinical benefit received additional doses every 12 weeks for up to 60 weeks.

Safety

Five patients discontinued ipilimumab due to dose-limiting toxic effects. Four of these patients had GVHD, and 1 had severe immune-related adverse events.

Dose-limiting GVHD presented as chronic GVHD of the liver in 3 patients and acute GVHD of the gut in 1 patient.

Immune-related adverse events included death (n=1), pneumonitis (2 grade 2 events, 1 grade 4 event), colitis (1 grade 3 event), immune thrombocytopenia (1 grade 2 event), and diarrhea (1 grade 2 event).

Efficacy

There were no responses in patients who received ipilimumab at 3 mg/kg. Among the 22 patients who received ipilimumab at 10 mg/kg, 5 had a complete response, and 2 had a partial response.

Six other patients did not qualify as having responses but had a decrease in their tumor burden. Altogether, ipilimumab reduced tumor burden in 59% of patients.

The complete responses occurred in 4 patients with extramedullary AML and 1 patient with MDS developing into AML. Two of the AML patients remained in complete response at 12 and 15 months, and the patient with MDS remained in complete response at 16 months.

At a median follow-up of 15 months (range, 8 to 27), the median duration of response had not been reached. Responses were associated with in situ infiltration of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, decreased activation of regulatory T cells, and expansion of subpopulations of effector T cells.

The 1-year overall survival rate was 49%.

The investigators said these encouraging results have set the stage for larger trials of checkpoint blockade in this patient population. Further research is planned to determine whether immunotherapy drugs could be given to high-risk patients to prevent relapse. ![]()

Photo from Business Wire

Results of a phase 1 study suggest that repeated doses of the immunotherapy drug ipilimumab is a feasible treatment option for patients with hematologic diseases who relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Seven of the 28 patients studied responded to the treatment, but immune-mediated toxic effects and graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) occurred as well.

These results were published in NEJM.

Ipilimumab, which is already approved to treat unresectable or metastatic melanoma, works by blocking the immune checkpoint CTLA-4. Blockade of CTLA-4 has been shown to augment T-cell activation and proliferation.

“We believe [,in the case of relapse after HSCT,] the donor immune cells are present but can’t recognize the tumor cells because of inhibitory signals that disguise them,” said study author Matthew Davids, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts.

“By blocking the checkpoint, you allow the donor cells to see the cancer cells.”

Dr Davids and his colleagues tested this theory in 28 patients who had relapsed after allogeneic HSCT. The patients had acute myeloid leukemia (AML, n=12), Hodgkin lymphoma (n=7), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n=4), myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS, n=2), multiple myeloma (n=1), myeloproliferative neoplasm (n=1), or acute lymphoblastic leukemia (n=1).

Patients had received a median of 3 prior treatment regimens, excluding HSCT (range, 1 to 14), and 20 patients (71%) had received treatment for relapse after transplant. Eight patients (29%) previously had grade 1/2 acute GVHD, and 16 (57%) previously had chronic GVHD.

The median time from transplant to initial treatment with ipilimumab was 675 days (range, 198 to 1830), and the median time from relapse to initial treatment with ipilimumab was 97 days (range, 0 to

1415).

Patients received induction therapy with ipilimumab at a dose of 3 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg every 3 weeks for a total of 4 doses. Those who had a clinical benefit received additional doses every 12 weeks for up to 60 weeks.

Safety

Five patients discontinued ipilimumab due to dose-limiting toxic effects. Four of these patients had GVHD, and 1 had severe immune-related adverse events.

Dose-limiting GVHD presented as chronic GVHD of the liver in 3 patients and acute GVHD of the gut in 1 patient.

Immune-related adverse events included death (n=1), pneumonitis (2 grade 2 events, 1 grade 4 event), colitis (1 grade 3 event), immune thrombocytopenia (1 grade 2 event), and diarrhea (1 grade 2 event).

Efficacy

There were no responses in patients who received ipilimumab at 3 mg/kg. Among the 22 patients who received ipilimumab at 10 mg/kg, 5 had a complete response, and 2 had a partial response.

Six other patients did not qualify as having responses but had a decrease in their tumor burden. Altogether, ipilimumab reduced tumor burden in 59% of patients.

The complete responses occurred in 4 patients with extramedullary AML and 1 patient with MDS developing into AML. Two of the AML patients remained in complete response at 12 and 15 months, and the patient with MDS remained in complete response at 16 months.

At a median follow-up of 15 months (range, 8 to 27), the median duration of response had not been reached. Responses were associated with in situ infiltration of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, decreased activation of regulatory T cells, and expansion of subpopulations of effector T cells.

The 1-year overall survival rate was 49%.

The investigators said these encouraging results have set the stage for larger trials of checkpoint blockade in this patient population. Further research is planned to determine whether immunotherapy drugs could be given to high-risk patients to prevent relapse. ![]()

Ipilimumab may restore antitumor immunity after relapse from HSCT

Early data hint that immune checkpoint inhibitors may be able to restore antitumor activity in patients with hematologic malignancies that have relapsed after allogeneic transplant.

Among 22 patients with relapsed hematologic cancers following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in a phase I/Ib study, treatment with the anti-CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab (Yervoy) at a dose of 10 mg/kg was associated with complete responses in five patients, partial responses in two, and decreased tumor burden in six, reported Matthew S. Davids, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and his colleagues.

“CTLA-4 blockade was a feasible approach for the treatment of patients with relapsed hematologic cancer after transplantation. Complete remissions with some durability were observed, even in patients with refractory myeloid cancers,” they wrote (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jul 14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1601202).

More than one-third of patients who undergo HSCT for hematologic malignancies such as lymphoma, multiple myeloma, or leukemia will experience a relapse, and most will die within a year of relapse despite salvage therapies or retransplantation, the authors noted.

“Immune escape (i.e., tumor evasion of the donor immune system) contributes to relapse after allogeneic HSCT, and immune checkpoint inhibitory pathways probably play an important role,” they wrote.

Selective CTLA-4 blockade has been shown in mouse models to treat late relapse after transplantation by augmenting graft-versus-tumor response without apparent exacerbation of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). To see whether the use of a CTLA-4 inhibitor could have the same effect in humans, the investigators instituted a single-group, open-label, dose-finding, safety and efficacy study of ipilimumab in 28 patients from six treatment sites.

The patients had all undergone allogeneic HSCT more than 3 months before the start of the study. The diagnoses included acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in 12 patients (including 3 with leukemia cutis and 1 with a myeloid sarcoma), Hodgkin lymphoma in 7, non-Hodgkin lymphoma in 4, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) in 2, and multiple myeloma, myeloproliferative neoplasm, and acute lymphoblastic leukemia in 1 patient each. Eight of the patients had previously had either grade I or II acute GVHD; 16 had had chronic GVHD.

Patients received induction therapy with ipilimumab at a dose of either 3 mg/kg (6 patients), or 10 mg/kg (22 patients) every 3 weeks for a total of 4 doses. Patients who experienced a clinical benefit from the drug could receive additional doses every 12 weeks for up to 60 weeks.

There were no clinical responses meeting study criteria in any of the patients who received the 3-mg/kg dose. Among the 22 who received the 10-mg/kg dose, however, the rate of complete responses was 23% (5 of 22), partial responses 9% (2 of 22), and decreased tumor burden 27% (6 of 22). The remaining nine patients experienced disease progression.

Four of the complete responses occurred in patients with extramedullary AML, and one occurred in a patient with MDS transforming into AML.

The safety analysis, which included all 28 patients evaluable for adverse events, showed four discontinuations due to dose-limiting chronic GVHD of the liver in the 3 patients, and acute GVHD of the gut in 1, and to severe immune-related events in one additional patient, leading to the patient’s death.

Other grade 3 or greater adverse events possibly related to ipilimumab included acute kidney injury (one patient) , corneal ulcer (one), thrombocytopenia (nine), neutropenia (three), anemia and pleural effusion (two).

The investigators point out that therapy to stimulate a graft-versus-tumor effect has the potential to promote or exacerbate GVHD, as occurred in four patients in the study. The GVHD in these patients was effectively managed with glucocorticoids, however.

The National Institutes of Health, Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, Pasquarello Tissue Bank, and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute supported the study. Dr. Davids disclosed grants from ASCO, the Pasquarello Tissue Bank, NIH, NCI, and Leukemia and Lymphoma society, and personal fees from several companies outside the study. Several coauthors disclosed relationships with various pharmaceutical companies, including Bristol-Myers Squibb, maker of ipilimumab.

Early data hint that immune checkpoint inhibitors may be able to restore antitumor activity in patients with hematologic malignancies that have relapsed after allogeneic transplant.

Among 22 patients with relapsed hematologic cancers following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in a phase I/Ib study, treatment with the anti-CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab (Yervoy) at a dose of 10 mg/kg was associated with complete responses in five patients, partial responses in two, and decreased tumor burden in six, reported Matthew S. Davids, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and his colleagues.

“CTLA-4 blockade was a feasible approach for the treatment of patients with relapsed hematologic cancer after transplantation. Complete remissions with some durability were observed, even in patients with refractory myeloid cancers,” they wrote (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jul 14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1601202).

More than one-third of patients who undergo HSCT for hematologic malignancies such as lymphoma, multiple myeloma, or leukemia will experience a relapse, and most will die within a year of relapse despite salvage therapies or retransplantation, the authors noted.

“Immune escape (i.e., tumor evasion of the donor immune system) contributes to relapse after allogeneic HSCT, and immune checkpoint inhibitory pathways probably play an important role,” they wrote.

Selective CTLA-4 blockade has been shown in mouse models to treat late relapse after transplantation by augmenting graft-versus-tumor response without apparent exacerbation of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). To see whether the use of a CTLA-4 inhibitor could have the same effect in humans, the investigators instituted a single-group, open-label, dose-finding, safety and efficacy study of ipilimumab in 28 patients from six treatment sites.

The patients had all undergone allogeneic HSCT more than 3 months before the start of the study. The diagnoses included acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in 12 patients (including 3 with leukemia cutis and 1 with a myeloid sarcoma), Hodgkin lymphoma in 7, non-Hodgkin lymphoma in 4, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) in 2, and multiple myeloma, myeloproliferative neoplasm, and acute lymphoblastic leukemia in 1 patient each. Eight of the patients had previously had either grade I or II acute GVHD; 16 had had chronic GVHD.

Patients received induction therapy with ipilimumab at a dose of either 3 mg/kg (6 patients), or 10 mg/kg (22 patients) every 3 weeks for a total of 4 doses. Patients who experienced a clinical benefit from the drug could receive additional doses every 12 weeks for up to 60 weeks.

There were no clinical responses meeting study criteria in any of the patients who received the 3-mg/kg dose. Among the 22 who received the 10-mg/kg dose, however, the rate of complete responses was 23% (5 of 22), partial responses 9% (2 of 22), and decreased tumor burden 27% (6 of 22). The remaining nine patients experienced disease progression.

Four of the complete responses occurred in patients with extramedullary AML, and one occurred in a patient with MDS transforming into AML.

The safety analysis, which included all 28 patients evaluable for adverse events, showed four discontinuations due to dose-limiting chronic GVHD of the liver in the 3 patients, and acute GVHD of the gut in 1, and to severe immune-related events in one additional patient, leading to the patient’s death.

Other grade 3 or greater adverse events possibly related to ipilimumab included acute kidney injury (one patient) , corneal ulcer (one), thrombocytopenia (nine), neutropenia (three), anemia and pleural effusion (two).

The investigators point out that therapy to stimulate a graft-versus-tumor effect has the potential to promote or exacerbate GVHD, as occurred in four patients in the study. The GVHD in these patients was effectively managed with glucocorticoids, however.

The National Institutes of Health, Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, Pasquarello Tissue Bank, and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute supported the study. Dr. Davids disclosed grants from ASCO, the Pasquarello Tissue Bank, NIH, NCI, and Leukemia and Lymphoma society, and personal fees from several companies outside the study. Several coauthors disclosed relationships with various pharmaceutical companies, including Bristol-Myers Squibb, maker of ipilimumab.

Early data hint that immune checkpoint inhibitors may be able to restore antitumor activity in patients with hematologic malignancies that have relapsed after allogeneic transplant.

Among 22 patients with relapsed hematologic cancers following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in a phase I/Ib study, treatment with the anti-CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab (Yervoy) at a dose of 10 mg/kg was associated with complete responses in five patients, partial responses in two, and decreased tumor burden in six, reported Matthew S. Davids, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and his colleagues.

“CTLA-4 blockade was a feasible approach for the treatment of patients with relapsed hematologic cancer after transplantation. Complete remissions with some durability were observed, even in patients with refractory myeloid cancers,” they wrote (N Engl J Med. 2016 Jul 14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1601202).

More than one-third of patients who undergo HSCT for hematologic malignancies such as lymphoma, multiple myeloma, or leukemia will experience a relapse, and most will die within a year of relapse despite salvage therapies or retransplantation, the authors noted.

“Immune escape (i.e., tumor evasion of the donor immune system) contributes to relapse after allogeneic HSCT, and immune checkpoint inhibitory pathways probably play an important role,” they wrote.

Selective CTLA-4 blockade has been shown in mouse models to treat late relapse after transplantation by augmenting graft-versus-tumor response without apparent exacerbation of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). To see whether the use of a CTLA-4 inhibitor could have the same effect in humans, the investigators instituted a single-group, open-label, dose-finding, safety and efficacy study of ipilimumab in 28 patients from six treatment sites.

The patients had all undergone allogeneic HSCT more than 3 months before the start of the study. The diagnoses included acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in 12 patients (including 3 with leukemia cutis and 1 with a myeloid sarcoma), Hodgkin lymphoma in 7, non-Hodgkin lymphoma in 4, myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) in 2, and multiple myeloma, myeloproliferative neoplasm, and acute lymphoblastic leukemia in 1 patient each. Eight of the patients had previously had either grade I or II acute GVHD; 16 had had chronic GVHD.

Patients received induction therapy with ipilimumab at a dose of either 3 mg/kg (6 patients), or 10 mg/kg (22 patients) every 3 weeks for a total of 4 doses. Patients who experienced a clinical benefit from the drug could receive additional doses every 12 weeks for up to 60 weeks.

There were no clinical responses meeting study criteria in any of the patients who received the 3-mg/kg dose. Among the 22 who received the 10-mg/kg dose, however, the rate of complete responses was 23% (5 of 22), partial responses 9% (2 of 22), and decreased tumor burden 27% (6 of 22). The remaining nine patients experienced disease progression.

Four of the complete responses occurred in patients with extramedullary AML, and one occurred in a patient with MDS transforming into AML.

The safety analysis, which included all 28 patients evaluable for adverse events, showed four discontinuations due to dose-limiting chronic GVHD of the liver in the 3 patients, and acute GVHD of the gut in 1, and to severe immune-related events in one additional patient, leading to the patient’s death.

Other grade 3 or greater adverse events possibly related to ipilimumab included acute kidney injury (one patient) , corneal ulcer (one), thrombocytopenia (nine), neutropenia (three), anemia and pleural effusion (two).

The investigators point out that therapy to stimulate a graft-versus-tumor effect has the potential to promote or exacerbate GVHD, as occurred in four patients in the study. The GVHD in these patients was effectively managed with glucocorticoids, however.

The National Institutes of Health, Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, Pasquarello Tissue Bank, and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute supported the study. Dr. Davids disclosed grants from ASCO, the Pasquarello Tissue Bank, NIH, NCI, and Leukemia and Lymphoma society, and personal fees from several companies outside the study. Several coauthors disclosed relationships with various pharmaceutical companies, including Bristol-Myers Squibb, maker of ipilimumab.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Anti-CTLA-4 therapy may restore graft-versus-tumor effect in patients with hematologic malignancies relapsed after allogeneic transplantation.

Major finding: Five of 22 patients on a 10-mg/kg dose of ipilimumab had a complete response.

Data source: Phase I/Ib investigator-initiated study of 28 patients with hematologic malignancies relapsed after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health, Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, Pasquarello Tissue Bank, and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute supported the study. Dr. Davids disclosed grants from ASCO, the Pasquarello Tissue Bank, NIH, NCI, and Leukemia and Lymphoma society, and personal fees from several companies outside the study. Several coauthors disclosed relationships with various pharmaceutical companies, including Bristol-Myers Squibb, maker of ipilimumab.

SU2C announces researcher-industry collaboration on immunotherapy

Stand Up To Cancer is calling for proposals to investigate additional uses for nivolumab, ipilimumab, elotuzumab, and urelumab, as part of a new researcher-industry collaborative program.

As many as four projects will be funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb, maker of the four agents, in the range of $1 million to $3 million each, according to a written statement from the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR).

The company will provide access to the three drugs already approved for the treatement of various cancers –nivolumab, ipilimumab, and elotuzumab– and to urelumab, an investigational agent that is currently in early clinical trials.

Proposals can include the study of one or more of the products, alone or in combination with other treatments, and may include products from other companies, as well as explore potential new uses for the drug(s), AACR said in the statement.

Nivolumab (Opdivo) is currently approved to treat advanced melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, and classical Hodgkin lymphoma; Ipilimumab (Yervoy) is approved to treat melanoma; and elotuzumab (Empliciti) is approved to treat multiple myeloma, in conjunction with other drugs. Urelumab is being evaluated as a treatment for a range of cancers, including some hematological cancers, advanced colorectal cancer, and head and neck cancers.

The Stand Up To Cancer (SU2C) Catalyst program was launched in April to “use funding and materials from the pharmaceutical, biotechnology, diagnostic, and medical devices industries to accelerate research on cancer prevention, detection, and treatment,” according to a written statement from SU2C. Founding collaborators in addition to Bristol-Myers Squibb include Merck and Genentech.

The Catalyst projects must follow the SU2C model be carried out by a collaborative team, and be designed to accelerate the clinical use of therapeutic agents within the 3-year term of the grant, and to deliver near-term patient benefit.

The Request for Proposal for the Bristol-Myers Squibb agents is available at proposalCENTRAL, with proposals due by noon ET Monday, Aug. 15.

On Twitter @NikolaidesLaura

Stand Up To Cancer is calling for proposals to investigate additional uses for nivolumab, ipilimumab, elotuzumab, and urelumab, as part of a new researcher-industry collaborative program.

As many as four projects will be funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb, maker of the four agents, in the range of $1 million to $3 million each, according to a written statement from the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR).

The company will provide access to the three drugs already approved for the treatement of various cancers –nivolumab, ipilimumab, and elotuzumab– and to urelumab, an investigational agent that is currently in early clinical trials.

Proposals can include the study of one or more of the products, alone or in combination with other treatments, and may include products from other companies, as well as explore potential new uses for the drug(s), AACR said in the statement.

Nivolumab (Opdivo) is currently approved to treat advanced melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, and classical Hodgkin lymphoma; Ipilimumab (Yervoy) is approved to treat melanoma; and elotuzumab (Empliciti) is approved to treat multiple myeloma, in conjunction with other drugs. Urelumab is being evaluated as a treatment for a range of cancers, including some hematological cancers, advanced colorectal cancer, and head and neck cancers.

The Stand Up To Cancer (SU2C) Catalyst program was launched in April to “use funding and materials from the pharmaceutical, biotechnology, diagnostic, and medical devices industries to accelerate research on cancer prevention, detection, and treatment,” according to a written statement from SU2C. Founding collaborators in addition to Bristol-Myers Squibb include Merck and Genentech.

The Catalyst projects must follow the SU2C model be carried out by a collaborative team, and be designed to accelerate the clinical use of therapeutic agents within the 3-year term of the grant, and to deliver near-term patient benefit.

The Request for Proposal for the Bristol-Myers Squibb agents is available at proposalCENTRAL, with proposals due by noon ET Monday, Aug. 15.

On Twitter @NikolaidesLaura