User login

Are you familiar with the use of Tamiflu in pregnant women?

Do not delay tranexamic acid for hemorrhage

Immediate treatment improved survival by more than 70% (odds ratio, 1.72; 95%; confidence interval, 1.42-2.10; P less than .0001), but the survival benefit decreased by 10% for every 15 minutes of treatment delay until hour 3, after which there was no benefit with tranexamic acid.

“Even a short delay in treatment reduces the benefit of tranexamic acid administration. Patients must be treated immediately,” said investigators led by Angele Gayet-Ageron, MD, PhD, of University Hospitals of Geneva.

“Trauma patients should be treated at the scene of injury and postpartum hemorrhage should be treated as soon as the diagnosis is made. Clinical audit should record the time from bleeding onset to tranexamic acid treatment, with feedback and best practice benchmarking,” they said in the Lancet.

The team found no increase in vascular occlusive events with tranexamic acid and no evidence of other adverse effects, so “it can be given safely as soon as bleeding is suspected,” they said.

Antifibrinolytics like tranexamic acid are known to reduce death from bleeding, but the effects of treatment delay have been less clear. To get an idea, the investigators ran a meta-analysis of subjects from two, large randomized tranexamic acid trials, one for trauma hemorrhage and the other for postpartum hemorrhage.

There were 1,408 deaths from bleeding among the 40,000-plus subjects. Most of the bleeding deaths (63%) occurred within 12 hours of onset; deaths from postpartum hemorrhage peaked at 2-3 hours after childbirth.

The authors had no competing interests. The trials were funded by the Britain’s National Institute for Health Research and Pfizer, among others.

SOURCE: Gayet-Ageron A et al. Lancet. 2017 Nov 7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32455-8

Early administration of tranexamic acid appears to offer the best hope for a good outcome in a bleeding patient with hyperfibrinolysis. The effect of tranexamic acid on inflammation and other pathways in patients without active bleeding is less clear. It is also unclear whether thromboelastography will move out of the research laboratory and become a routine means of assessment for bleeding patients.

At present, the careful study of Dr. Gayet-Ageron and her coworkers suggests applicability of early administration of this agent in patients with substantial bleeding from multiple causes. As data from additional trials with tranexamic acid become available, the spectrum of applications for this agent should become apparent.

David Dries, MD, is a professor of surgery at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. He made his comments in an editorial (Lancet. 2017 Nov 7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32806-4) and had no competing interests.

Early administration of tranexamic acid appears to offer the best hope for a good outcome in a bleeding patient with hyperfibrinolysis. The effect of tranexamic acid on inflammation and other pathways in patients without active bleeding is less clear. It is also unclear whether thromboelastography will move out of the research laboratory and become a routine means of assessment for bleeding patients.

At present, the careful study of Dr. Gayet-Ageron and her coworkers suggests applicability of early administration of this agent in patients with substantial bleeding from multiple causes. As data from additional trials with tranexamic acid become available, the spectrum of applications for this agent should become apparent.

David Dries, MD, is a professor of surgery at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. He made his comments in an editorial (Lancet. 2017 Nov 7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32806-4) and had no competing interests.

Early administration of tranexamic acid appears to offer the best hope for a good outcome in a bleeding patient with hyperfibrinolysis. The effect of tranexamic acid on inflammation and other pathways in patients without active bleeding is less clear. It is also unclear whether thromboelastography will move out of the research laboratory and become a routine means of assessment for bleeding patients.

At present, the careful study of Dr. Gayet-Ageron and her coworkers suggests applicability of early administration of this agent in patients with substantial bleeding from multiple causes. As data from additional trials with tranexamic acid become available, the spectrum of applications for this agent should become apparent.

David Dries, MD, is a professor of surgery at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. He made his comments in an editorial (Lancet. 2017 Nov 7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32806-4) and had no competing interests.

Immediate treatment improved survival by more than 70% (odds ratio, 1.72; 95%; confidence interval, 1.42-2.10; P less than .0001), but the survival benefit decreased by 10% for every 15 minutes of treatment delay until hour 3, after which there was no benefit with tranexamic acid.

“Even a short delay in treatment reduces the benefit of tranexamic acid administration. Patients must be treated immediately,” said investigators led by Angele Gayet-Ageron, MD, PhD, of University Hospitals of Geneva.

“Trauma patients should be treated at the scene of injury and postpartum hemorrhage should be treated as soon as the diagnosis is made. Clinical audit should record the time from bleeding onset to tranexamic acid treatment, with feedback and best practice benchmarking,” they said in the Lancet.

The team found no increase in vascular occlusive events with tranexamic acid and no evidence of other adverse effects, so “it can be given safely as soon as bleeding is suspected,” they said.

Antifibrinolytics like tranexamic acid are known to reduce death from bleeding, but the effects of treatment delay have been less clear. To get an idea, the investigators ran a meta-analysis of subjects from two, large randomized tranexamic acid trials, one for trauma hemorrhage and the other for postpartum hemorrhage.

There were 1,408 deaths from bleeding among the 40,000-plus subjects. Most of the bleeding deaths (63%) occurred within 12 hours of onset; deaths from postpartum hemorrhage peaked at 2-3 hours after childbirth.

The authors had no competing interests. The trials were funded by the Britain’s National Institute for Health Research and Pfizer, among others.

SOURCE: Gayet-Ageron A et al. Lancet. 2017 Nov 7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32455-8

Immediate treatment improved survival by more than 70% (odds ratio, 1.72; 95%; confidence interval, 1.42-2.10; P less than .0001), but the survival benefit decreased by 10% for every 15 minutes of treatment delay until hour 3, after which there was no benefit with tranexamic acid.

“Even a short delay in treatment reduces the benefit of tranexamic acid administration. Patients must be treated immediately,” said investigators led by Angele Gayet-Ageron, MD, PhD, of University Hospitals of Geneva.

“Trauma patients should be treated at the scene of injury and postpartum hemorrhage should be treated as soon as the diagnosis is made. Clinical audit should record the time from bleeding onset to tranexamic acid treatment, with feedback and best practice benchmarking,” they said in the Lancet.

The team found no increase in vascular occlusive events with tranexamic acid and no evidence of other adverse effects, so “it can be given safely as soon as bleeding is suspected,” they said.

Antifibrinolytics like tranexamic acid are known to reduce death from bleeding, but the effects of treatment delay have been less clear. To get an idea, the investigators ran a meta-analysis of subjects from two, large randomized tranexamic acid trials, one for trauma hemorrhage and the other for postpartum hemorrhage.

There were 1,408 deaths from bleeding among the 40,000-plus subjects. Most of the bleeding deaths (63%) occurred within 12 hours of onset; deaths from postpartum hemorrhage peaked at 2-3 hours after childbirth.

The authors had no competing interests. The trials were funded by the Britain’s National Institute for Health Research and Pfizer, among others.

SOURCE: Gayet-Ageron A et al. Lancet. 2017 Nov 7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32455-8

FROM THE LANCET

Preterm intervention underused in at-risk women

A significant number of woman who delivered ahead of term and were already considered at risk for spontaneous preterm birth did not receive any sort of intervention to prevent the preterm birth, according to Yu Yang Feng and associates.

For the retrospective study, the researchers analyzed the medical records of 31 women who had been admitted to a primary, secondary, or tertiary prenatal care center and who had a history of spontaneous singleton preterm birth and/or cervical shortening before 24 weeks of gestation. Of the 23 women who were referred to a prenatal care center before reaching a gestational age of 24 weeks, only 13 were offered an intervention and only 12 received progesterone or cerclage as an intervention, while none received pessary. One of the 13 was offered and declined progesterone.

Of the 12 women who received an intervention before 24 weeks’ gestational age, 8 received progesterone, 2 received elective cerclage, and 2 received rescue cerclage. An additional woman who was referred to a prenatal care center after 24 weeks received progesterone, the only one in that group to receive an intervention.

Most of the women in the study were referred to a prenatal care center by their family physician, although two were referred by their midwife, one was referred by a nurse practitioner and fertility specialist, and three started their care with an obstetrician.

“Our findings that less than one in three women with a previous preterm birth or current short cervix received progesterone attest to the importance of improving knowledge translation with the latest evidence to encourage referral in time and use of this intervention for the prevention of preterm birth,” the study investigators concluded.

Find the full study in the Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada (2018 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2017.08.036).

A significant number of woman who delivered ahead of term and were already considered at risk for spontaneous preterm birth did not receive any sort of intervention to prevent the preterm birth, according to Yu Yang Feng and associates.

For the retrospective study, the researchers analyzed the medical records of 31 women who had been admitted to a primary, secondary, or tertiary prenatal care center and who had a history of spontaneous singleton preterm birth and/or cervical shortening before 24 weeks of gestation. Of the 23 women who were referred to a prenatal care center before reaching a gestational age of 24 weeks, only 13 were offered an intervention and only 12 received progesterone or cerclage as an intervention, while none received pessary. One of the 13 was offered and declined progesterone.

Of the 12 women who received an intervention before 24 weeks’ gestational age, 8 received progesterone, 2 received elective cerclage, and 2 received rescue cerclage. An additional woman who was referred to a prenatal care center after 24 weeks received progesterone, the only one in that group to receive an intervention.

Most of the women in the study were referred to a prenatal care center by their family physician, although two were referred by their midwife, one was referred by a nurse practitioner and fertility specialist, and three started their care with an obstetrician.

“Our findings that less than one in three women with a previous preterm birth or current short cervix received progesterone attest to the importance of improving knowledge translation with the latest evidence to encourage referral in time and use of this intervention for the prevention of preterm birth,” the study investigators concluded.

Find the full study in the Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada (2018 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2017.08.036).

A significant number of woman who delivered ahead of term and were already considered at risk for spontaneous preterm birth did not receive any sort of intervention to prevent the preterm birth, according to Yu Yang Feng and associates.

For the retrospective study, the researchers analyzed the medical records of 31 women who had been admitted to a primary, secondary, or tertiary prenatal care center and who had a history of spontaneous singleton preterm birth and/or cervical shortening before 24 weeks of gestation. Of the 23 women who were referred to a prenatal care center before reaching a gestational age of 24 weeks, only 13 were offered an intervention and only 12 received progesterone or cerclage as an intervention, while none received pessary. One of the 13 was offered and declined progesterone.

Of the 12 women who received an intervention before 24 weeks’ gestational age, 8 received progesterone, 2 received elective cerclage, and 2 received rescue cerclage. An additional woman who was referred to a prenatal care center after 24 weeks received progesterone, the only one in that group to receive an intervention.

Most of the women in the study were referred to a prenatal care center by their family physician, although two were referred by their midwife, one was referred by a nurse practitioner and fertility specialist, and three started their care with an obstetrician.

“Our findings that less than one in three women with a previous preterm birth or current short cervix received progesterone attest to the importance of improving knowledge translation with the latest evidence to encourage referral in time and use of this intervention for the prevention of preterm birth,” the study investigators concluded.

Find the full study in the Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada (2018 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2017.08.036).

FROM THE JOURNAL OF OBSTETRICS AND GYNAECOLOGY CANADA

Fetal fibronectin testing is infrequent

Fetal fibronectin testing was linked to longer gestation periods and a lower risk of delivery occurring within 3 days of the first hospital contact, but only about half of women with symptoms of preterm labor (PTL, weeks 24-37) received any testing at all for PTL, and just 14.0% received fFN, according to an analysis of administrative claims data from Medicaid enrollees in Texas.

Fetal fibronectin (fFN) testing can help determine the probability of spontaneous preterm birth in the following 14 days.

The results reinforce the value of fFN in predicting spontaneous preterm birth, but also underline the need for additional testing.

Women who received the fFN test incurred an additional cost of $2,252, compared with those who did not receive the test, but their gestation periods lasted an average of 9 additional days. The researchers point out that a conservative cost of time spent in the neonatal intensive care unit is $3,000-$3,500 per day, so that the increased cost of testing would be likely be offset by cost reductions in preterm births.

The study comprised 29,553 women aged 21 years and older who went to the emergency department or were admitted to the hospital with PTL between Jan. 1, 2012, and May 31, 2015. During the 5 months prior to delivery, 74.0% of the subjects received a PTL diagnosis, and 26.0% were diagnosed with threatened PTL, defined as early, threatened, or false labor. Nearly half of the patients (49.8%) underwent at least one PTL test, most often transvaginal ultrasound (44.1%). Just 14.0% of patients received fFN testing.

The researchers used propensity score matching to account for baseline differences in risk factors for the two groups, creating two groups of 4,098 patients (fFN and non-fFN) for the final cohort study.

Patients who received fFN testing were less likely to deliver during the initial health care visit (45.9% vs. 59.3%; P less than .0001) and had a longer mean time to delivery (24.6 days vs. 15.2 days; P less than .0001). They were less likely to deliver within 3 days of the initial visit (49.1% vs. 63.9%; P less than .0001).

Women who received fFN testing had higher all-cause maternal health care costs ($15,238.20 vs. $12,985.80; P less than .0001).

The study did not include newborn outcomes and health care costs. “It is unknown whether use of fFN testing is associated with improved newborn outcomes; if it is, fFN testing could potentially reduce newborn-incurred costs, offsetting the costs associated with testing,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE: Barner J et al. Am J Manag Care. 2017 Dec;23(19 Suppl):S363-70.

Fetal fibronectin testing was linked to longer gestation periods and a lower risk of delivery occurring within 3 days of the first hospital contact, but only about half of women with symptoms of preterm labor (PTL, weeks 24-37) received any testing at all for PTL, and just 14.0% received fFN, according to an analysis of administrative claims data from Medicaid enrollees in Texas.

Fetal fibronectin (fFN) testing can help determine the probability of spontaneous preterm birth in the following 14 days.

The results reinforce the value of fFN in predicting spontaneous preterm birth, but also underline the need for additional testing.

Women who received the fFN test incurred an additional cost of $2,252, compared with those who did not receive the test, but their gestation periods lasted an average of 9 additional days. The researchers point out that a conservative cost of time spent in the neonatal intensive care unit is $3,000-$3,500 per day, so that the increased cost of testing would be likely be offset by cost reductions in preterm births.

The study comprised 29,553 women aged 21 years and older who went to the emergency department or were admitted to the hospital with PTL between Jan. 1, 2012, and May 31, 2015. During the 5 months prior to delivery, 74.0% of the subjects received a PTL diagnosis, and 26.0% were diagnosed with threatened PTL, defined as early, threatened, or false labor. Nearly half of the patients (49.8%) underwent at least one PTL test, most often transvaginal ultrasound (44.1%). Just 14.0% of patients received fFN testing.

The researchers used propensity score matching to account for baseline differences in risk factors for the two groups, creating two groups of 4,098 patients (fFN and non-fFN) for the final cohort study.

Patients who received fFN testing were less likely to deliver during the initial health care visit (45.9% vs. 59.3%; P less than .0001) and had a longer mean time to delivery (24.6 days vs. 15.2 days; P less than .0001). They were less likely to deliver within 3 days of the initial visit (49.1% vs. 63.9%; P less than .0001).

Women who received fFN testing had higher all-cause maternal health care costs ($15,238.20 vs. $12,985.80; P less than .0001).

The study did not include newborn outcomes and health care costs. “It is unknown whether use of fFN testing is associated with improved newborn outcomes; if it is, fFN testing could potentially reduce newborn-incurred costs, offsetting the costs associated with testing,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE: Barner J et al. Am J Manag Care. 2017 Dec;23(19 Suppl):S363-70.

Fetal fibronectin testing was linked to longer gestation periods and a lower risk of delivery occurring within 3 days of the first hospital contact, but only about half of women with symptoms of preterm labor (PTL, weeks 24-37) received any testing at all for PTL, and just 14.0% received fFN, according to an analysis of administrative claims data from Medicaid enrollees in Texas.

Fetal fibronectin (fFN) testing can help determine the probability of spontaneous preterm birth in the following 14 days.

The results reinforce the value of fFN in predicting spontaneous preterm birth, but also underline the need for additional testing.

Women who received the fFN test incurred an additional cost of $2,252, compared with those who did not receive the test, but their gestation periods lasted an average of 9 additional days. The researchers point out that a conservative cost of time spent in the neonatal intensive care unit is $3,000-$3,500 per day, so that the increased cost of testing would be likely be offset by cost reductions in preterm births.

The study comprised 29,553 women aged 21 years and older who went to the emergency department or were admitted to the hospital with PTL between Jan. 1, 2012, and May 31, 2015. During the 5 months prior to delivery, 74.0% of the subjects received a PTL diagnosis, and 26.0% were diagnosed with threatened PTL, defined as early, threatened, or false labor. Nearly half of the patients (49.8%) underwent at least one PTL test, most often transvaginal ultrasound (44.1%). Just 14.0% of patients received fFN testing.

The researchers used propensity score matching to account for baseline differences in risk factors for the two groups, creating two groups of 4,098 patients (fFN and non-fFN) for the final cohort study.

Patients who received fFN testing were less likely to deliver during the initial health care visit (45.9% vs. 59.3%; P less than .0001) and had a longer mean time to delivery (24.6 days vs. 15.2 days; P less than .0001). They were less likely to deliver within 3 days of the initial visit (49.1% vs. 63.9%; P less than .0001).

Women who received fFN testing had higher all-cause maternal health care costs ($15,238.20 vs. $12,985.80; P less than .0001).

The study did not include newborn outcomes and health care costs. “It is unknown whether use of fFN testing is associated with improved newborn outcomes; if it is, fFN testing could potentially reduce newborn-incurred costs, offsetting the costs associated with testing,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE: Barner J et al. Am J Manag Care. 2017 Dec;23(19 Suppl):S363-70.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MANAGED CARE

Key clinical point: Fetal fibronectin testing in women presenting with preterm labor improves delivery outcomes, but is rarely applied in at-risk women.

Major finding: Fourteen percent of women who presented with symptoms of preterm labor received the fetal fibronectin test.

Data source: Retrospective analysis of claims data among Medicaid recipients in Texas (n = 29,553).

Disclosures: The study was funded by Hologic, which markets the Fetal Fibronectin Enzyme immunoassay and Rapid fFN Test. Some of the authors have financial ties to Hologic.

Source: Barner J et al. Am J Manag Care. 2017 Dec;23(19 Suppl):S363-70.

Influenza vaccination of pregnant women needs surveillance

Seasonal influenza vaccine is specifically recommended for women who are or who might become pregnant in the flu season. This special population is targeted for vaccination because pregnant women are at increased risks of serious complications if infected with influenza virus. Despite this recommendation, recent evidence indicates that still fewer than 50% of women in the United States are vaccinated during pregnancy (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Dec 9;65[48]:1370-3).

Potential reasons for this lack of uptake are concerns about safety of the vaccine for mothers and fetuses (Vaccine. 2012 Dec 17;31[1]:213-8). This has highlighted the need for systematic safety surveillance for influenza vaccination with each subsequent seasonal formulation. To that end, season-specific studies of birth and infant outcomes since the 2009 season have been conducted; findings have been generally reassuring (Vaccine. 2016 Aug 17;34[37]:4443-9; Vaccine. 2016 Aug 17;34[37]:4450-9).

The authors found a doubling of risk for spontaneous abortion within that 28-day exposure window, but no association if the vaccination took place outside that period. This was in contrast to null findings for a similar analysis that the same group had conducted for vaccination in the 2005-2006 and 2006-2007 seasons. Of further interest, the authors noted even higher risks among women who had also been vaccinated for influenza in the previous season (adjusted odds ratio, 7.7; 95% confidence interval, 2.2-27.3). The highest odds ratios were among women who had been vaccinated in the 2010-2011 season and had also been vaccinated with monovalent pandemic H1N1 vaccine in the 2009-2010 season (aOR, 32.5; 95% CI, 2.9-359.0).

The VSD findings raise interesting questions about the biologic plausibility of strain-specific risks for spontaneous abortion, and risks of receiving a second vaccine containing the same strain in a subsequent season. However, this study should be interpreted with caution. With respect to the overall finding of a doubling of risk for spontaneous abortion, this is inconsistent with previous studies. A systematic review of 19 observational studies, 14 of which included exposure to the 2009 monovalent pandemic H1N1 strain, noted hazard ratios or odds ratios for spontaneous abortion ranging from 0.45 to 1.23 and 95% confidence intervals that crossed or were below the null (Vaccine. 2015 Apr 27;33[18]:2108-17). More recently, the Vaccines and Medications in Pregnancy Surveillance System investigators evaluated spontaneous abortion in pregnancies exposed to influenza vaccine over four seasons from 2010 to 2014 and found an overall hazard ratio of 1.09 (95% CI, 0.49-2.40).

However, there are a number of limitations that must be considered. Many previous studies, including the VSD analysis, could have had misclassification of exposure, especially in recent years when vaccines are often received in nontraditional settings. The VSD study findings could have been influenced by unmeasured confounding. For example, there could be differential vaccine uptake in women with comorbidities that are also associated with spontaneous abortion, such as subfertility and psychiatric disorders.

In summary, at present the data viewed as a whole do not support a change to the current recommendation that pregnant women be vaccinated for influenza regardless of trimester. However, these data do call for continued surveillance for the safety of each seasonal formulation of influenza vaccine, and for further exploration of the association between repeat vaccination and spontaneous abortion in other datasets.

Dr. Chambers is professor of pediatrics and director of clinical research at Rady Children’s Hospital and associate director of the Clinical and Translational Research Institute at the University of California, San Diego. She is also director of MotherToBaby California, a past president of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, and past president of the Teratology Society. She has no direct conflicts of interest to disclose, but has received grant funding to study influenza vaccine from the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) in the Department of Health and Human Services, and from Seqirus Corporation.

Seasonal influenza vaccine is specifically recommended for women who are or who might become pregnant in the flu season. This special population is targeted for vaccination because pregnant women are at increased risks of serious complications if infected with influenza virus. Despite this recommendation, recent evidence indicates that still fewer than 50% of women in the United States are vaccinated during pregnancy (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Dec 9;65[48]:1370-3).

Potential reasons for this lack of uptake are concerns about safety of the vaccine for mothers and fetuses (Vaccine. 2012 Dec 17;31[1]:213-8). This has highlighted the need for systematic safety surveillance for influenza vaccination with each subsequent seasonal formulation. To that end, season-specific studies of birth and infant outcomes since the 2009 season have been conducted; findings have been generally reassuring (Vaccine. 2016 Aug 17;34[37]:4443-9; Vaccine. 2016 Aug 17;34[37]:4450-9).

The authors found a doubling of risk for spontaneous abortion within that 28-day exposure window, but no association if the vaccination took place outside that period. This was in contrast to null findings for a similar analysis that the same group had conducted for vaccination in the 2005-2006 and 2006-2007 seasons. Of further interest, the authors noted even higher risks among women who had also been vaccinated for influenza in the previous season (adjusted odds ratio, 7.7; 95% confidence interval, 2.2-27.3). The highest odds ratios were among women who had been vaccinated in the 2010-2011 season and had also been vaccinated with monovalent pandemic H1N1 vaccine in the 2009-2010 season (aOR, 32.5; 95% CI, 2.9-359.0).

The VSD findings raise interesting questions about the biologic plausibility of strain-specific risks for spontaneous abortion, and risks of receiving a second vaccine containing the same strain in a subsequent season. However, this study should be interpreted with caution. With respect to the overall finding of a doubling of risk for spontaneous abortion, this is inconsistent with previous studies. A systematic review of 19 observational studies, 14 of which included exposure to the 2009 monovalent pandemic H1N1 strain, noted hazard ratios or odds ratios for spontaneous abortion ranging from 0.45 to 1.23 and 95% confidence intervals that crossed or were below the null (Vaccine. 2015 Apr 27;33[18]:2108-17). More recently, the Vaccines and Medications in Pregnancy Surveillance System investigators evaluated spontaneous abortion in pregnancies exposed to influenza vaccine over four seasons from 2010 to 2014 and found an overall hazard ratio of 1.09 (95% CI, 0.49-2.40).

However, there are a number of limitations that must be considered. Many previous studies, including the VSD analysis, could have had misclassification of exposure, especially in recent years when vaccines are often received in nontraditional settings. The VSD study findings could have been influenced by unmeasured confounding. For example, there could be differential vaccine uptake in women with comorbidities that are also associated with spontaneous abortion, such as subfertility and psychiatric disorders.

In summary, at present the data viewed as a whole do not support a change to the current recommendation that pregnant women be vaccinated for influenza regardless of trimester. However, these data do call for continued surveillance for the safety of each seasonal formulation of influenza vaccine, and for further exploration of the association between repeat vaccination and spontaneous abortion in other datasets.

Dr. Chambers is professor of pediatrics and director of clinical research at Rady Children’s Hospital and associate director of the Clinical and Translational Research Institute at the University of California, San Diego. She is also director of MotherToBaby California, a past president of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, and past president of the Teratology Society. She has no direct conflicts of interest to disclose, but has received grant funding to study influenza vaccine from the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) in the Department of Health and Human Services, and from Seqirus Corporation.

Seasonal influenza vaccine is specifically recommended for women who are or who might become pregnant in the flu season. This special population is targeted for vaccination because pregnant women are at increased risks of serious complications if infected with influenza virus. Despite this recommendation, recent evidence indicates that still fewer than 50% of women in the United States are vaccinated during pregnancy (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Dec 9;65[48]:1370-3).

Potential reasons for this lack of uptake are concerns about safety of the vaccine for mothers and fetuses (Vaccine. 2012 Dec 17;31[1]:213-8). This has highlighted the need for systematic safety surveillance for influenza vaccination with each subsequent seasonal formulation. To that end, season-specific studies of birth and infant outcomes since the 2009 season have been conducted; findings have been generally reassuring (Vaccine. 2016 Aug 17;34[37]:4443-9; Vaccine. 2016 Aug 17;34[37]:4450-9).

The authors found a doubling of risk for spontaneous abortion within that 28-day exposure window, but no association if the vaccination took place outside that period. This was in contrast to null findings for a similar analysis that the same group had conducted for vaccination in the 2005-2006 and 2006-2007 seasons. Of further interest, the authors noted even higher risks among women who had also been vaccinated for influenza in the previous season (adjusted odds ratio, 7.7; 95% confidence interval, 2.2-27.3). The highest odds ratios were among women who had been vaccinated in the 2010-2011 season and had also been vaccinated with monovalent pandemic H1N1 vaccine in the 2009-2010 season (aOR, 32.5; 95% CI, 2.9-359.0).

The VSD findings raise interesting questions about the biologic plausibility of strain-specific risks for spontaneous abortion, and risks of receiving a second vaccine containing the same strain in a subsequent season. However, this study should be interpreted with caution. With respect to the overall finding of a doubling of risk for spontaneous abortion, this is inconsistent with previous studies. A systematic review of 19 observational studies, 14 of which included exposure to the 2009 monovalent pandemic H1N1 strain, noted hazard ratios or odds ratios for spontaneous abortion ranging from 0.45 to 1.23 and 95% confidence intervals that crossed or were below the null (Vaccine. 2015 Apr 27;33[18]:2108-17). More recently, the Vaccines and Medications in Pregnancy Surveillance System investigators evaluated spontaneous abortion in pregnancies exposed to influenza vaccine over four seasons from 2010 to 2014 and found an overall hazard ratio of 1.09 (95% CI, 0.49-2.40).

However, there are a number of limitations that must be considered. Many previous studies, including the VSD analysis, could have had misclassification of exposure, especially in recent years when vaccines are often received in nontraditional settings. The VSD study findings could have been influenced by unmeasured confounding. For example, there could be differential vaccine uptake in women with comorbidities that are also associated with spontaneous abortion, such as subfertility and psychiatric disorders.

In summary, at present the data viewed as a whole do not support a change to the current recommendation that pregnant women be vaccinated for influenza regardless of trimester. However, these data do call for continued surveillance for the safety of each seasonal formulation of influenza vaccine, and for further exploration of the association between repeat vaccination and spontaneous abortion in other datasets.

Dr. Chambers is professor of pediatrics and director of clinical research at Rady Children’s Hospital and associate director of the Clinical and Translational Research Institute at the University of California, San Diego. She is also director of MotherToBaby California, a past president of the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists, and past president of the Teratology Society. She has no direct conflicts of interest to disclose, but has received grant funding to study influenza vaccine from the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) in the Department of Health and Human Services, and from Seqirus Corporation.

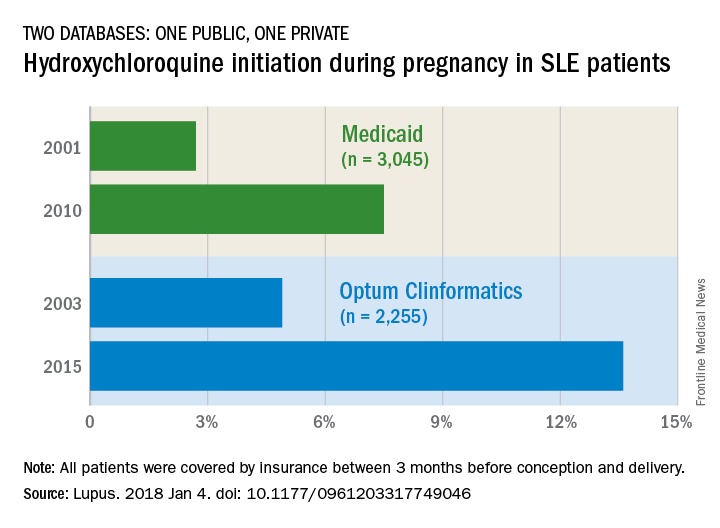

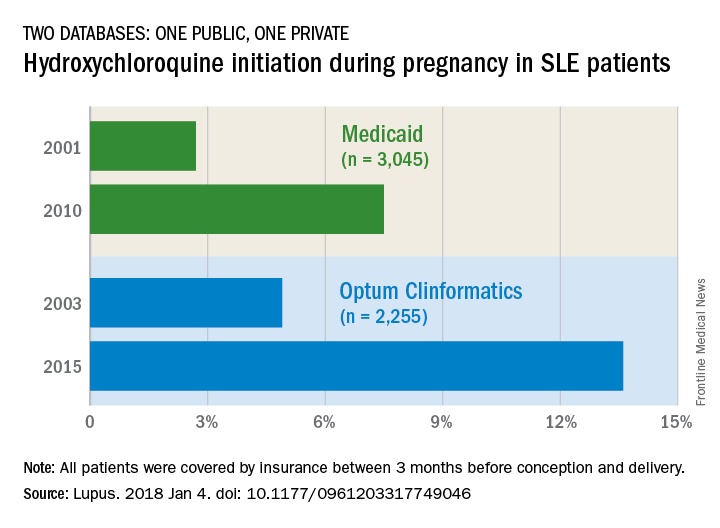

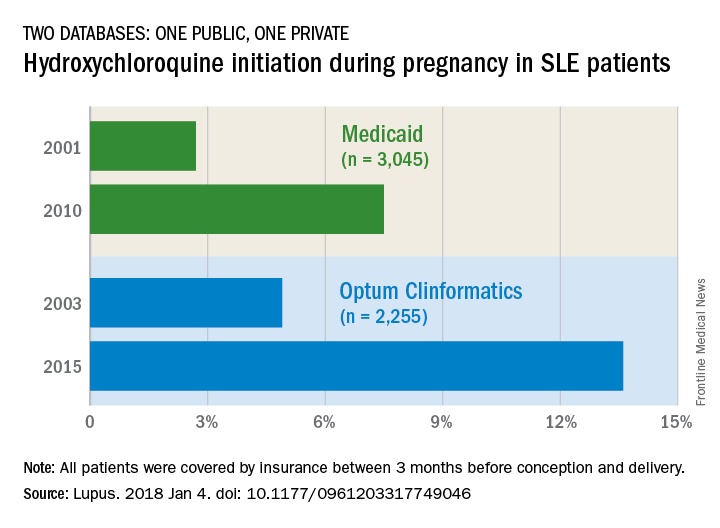

Hydroxychloroquine use rising in SLE pregnancies

but its use “remains low, and that is concerning for maternal and fetal well-being,” said investigators who analyzed one public and one private database.

The two databases showed increases of somewhat different scale. According to Medicaid data on 3,045 pregnancies among SLE women, initiation of hydroxychloroquine rose from 2.7% in 2001 to 7.5% (P = .0002) in 2010. The analysis of data for 2,255 SLE pregnancies from a large commercial insurance database (Optum Clinformatics) showed an increase from 4.9% in 2003 to 13.6% (P = .0001) in 2015, wrote Bonnie L. Bermas, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and her associates. The report was published in Lupus.

The study was funded by Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School. Dr. Bermas did not report any conflicts. Her associates reported unrelated projects with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Bermas BL et al. Lupus. 2018 Jan 4. doi: 10.1177/0961203317749046.

but its use “remains low, and that is concerning for maternal and fetal well-being,” said investigators who analyzed one public and one private database.

The two databases showed increases of somewhat different scale. According to Medicaid data on 3,045 pregnancies among SLE women, initiation of hydroxychloroquine rose from 2.7% in 2001 to 7.5% (P = .0002) in 2010. The analysis of data for 2,255 SLE pregnancies from a large commercial insurance database (Optum Clinformatics) showed an increase from 4.9% in 2003 to 13.6% (P = .0001) in 2015, wrote Bonnie L. Bermas, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and her associates. The report was published in Lupus.

The study was funded by Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School. Dr. Bermas did not report any conflicts. Her associates reported unrelated projects with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Bermas BL et al. Lupus. 2018 Jan 4. doi: 10.1177/0961203317749046.

but its use “remains low, and that is concerning for maternal and fetal well-being,” said investigators who analyzed one public and one private database.

The two databases showed increases of somewhat different scale. According to Medicaid data on 3,045 pregnancies among SLE women, initiation of hydroxychloroquine rose from 2.7% in 2001 to 7.5% (P = .0002) in 2010. The analysis of data for 2,255 SLE pregnancies from a large commercial insurance database (Optum Clinformatics) showed an increase from 4.9% in 2003 to 13.6% (P = .0001) in 2015, wrote Bonnie L. Bermas, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and her associates. The report was published in Lupus.

The study was funded by Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School. Dr. Bermas did not report any conflicts. Her associates reported unrelated projects with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Bermas BL et al. Lupus. 2018 Jan 4. doi: 10.1177/0961203317749046.

FROM LUPUS

Breastfeeding lowers later diabetes risk in women

Breastfeeding may reduce a woman’s risk of developing diabetes, with a prospective cohort study showing a strong, inverse association between lactation duration and risk of diabetes.

In a report published in the Jan. 16 online edition of JAMA Internal Medicine, researchers analyzed data from the Coronary Artery Risk Development Study in Young Adults (CARDIA), which followed 1,238 women aged 18-30 for 30 years, with multiple assessments of glucose tolerance over the course of the study.

Women who breastfed for 6-12 months had a 48% reduction in the risk of diabetes (95% CI, 0.31-0.87), and those who breastfed for up to 6 months had a 25% lower risk (95% CI, 0.51-1.09), with the trend being significant.

In women with a history of gestational diabetes, those who did not breastfeed at all had a 2.08% higher excess risk of incident diabetes per year, compared with women who breastfed for at least 12 months. The increase in excess risk for the same comparison in women without a history of gestational diabetes was 0.48% per year.

Erica P. Gunderson, PhD, of Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Oakland, and her coauthors noted that previous meta-analyses of the effect of lactation on diabetes incidence or prevalence pointed to protective summary estimates of 9%-11% per year of lactation.

“Lactating women have lower circulating glucose in both fasting and post absorptive states, as well as lower insulin secretion, despite increased glucose production rates,” the authors wrote. “About 50 g of glucose per 24 hours is diverted into the mammary gland for milk synthesis via non–insulin mediated pathways.”

Studies in mice have also suggested that lactating animals have greater pancreatic beta-cell proliferation.

While the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommend breastfeeding for 1 year, only 55% of women in the United States are still breastfeeding at 6 months and 33% are still breastfeeding at 1 year after birth. Black women are also less likely to breastfeed, regardless of socioeconomic status or body size.

“Lactation is a natural biological process with the enormous potential to provide long-term benefits to maternal health, but has been underappreciated as a potential key strategy for early primary prevention of metabolic diseases in women across the childbearing years and beyond.”

The study and analyses were supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and two authors declared funding from pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Jan 16. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7978.

Breastfeeding may reduce a woman’s risk of developing diabetes, with a prospective cohort study showing a strong, inverse association between lactation duration and risk of diabetes.

In a report published in the Jan. 16 online edition of JAMA Internal Medicine, researchers analyzed data from the Coronary Artery Risk Development Study in Young Adults (CARDIA), which followed 1,238 women aged 18-30 for 30 years, with multiple assessments of glucose tolerance over the course of the study.

Women who breastfed for 6-12 months had a 48% reduction in the risk of diabetes (95% CI, 0.31-0.87), and those who breastfed for up to 6 months had a 25% lower risk (95% CI, 0.51-1.09), with the trend being significant.

In women with a history of gestational diabetes, those who did not breastfeed at all had a 2.08% higher excess risk of incident diabetes per year, compared with women who breastfed for at least 12 months. The increase in excess risk for the same comparison in women without a history of gestational diabetes was 0.48% per year.

Erica P. Gunderson, PhD, of Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Oakland, and her coauthors noted that previous meta-analyses of the effect of lactation on diabetes incidence or prevalence pointed to protective summary estimates of 9%-11% per year of lactation.

“Lactating women have lower circulating glucose in both fasting and post absorptive states, as well as lower insulin secretion, despite increased glucose production rates,” the authors wrote. “About 50 g of glucose per 24 hours is diverted into the mammary gland for milk synthesis via non–insulin mediated pathways.”

Studies in mice have also suggested that lactating animals have greater pancreatic beta-cell proliferation.

While the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommend breastfeeding for 1 year, only 55% of women in the United States are still breastfeeding at 6 months and 33% are still breastfeeding at 1 year after birth. Black women are also less likely to breastfeed, regardless of socioeconomic status or body size.

“Lactation is a natural biological process with the enormous potential to provide long-term benefits to maternal health, but has been underappreciated as a potential key strategy for early primary prevention of metabolic diseases in women across the childbearing years and beyond.”

The study and analyses were supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and two authors declared funding from pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Jan 16. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7978.

Breastfeeding may reduce a woman’s risk of developing diabetes, with a prospective cohort study showing a strong, inverse association between lactation duration and risk of diabetes.

In a report published in the Jan. 16 online edition of JAMA Internal Medicine, researchers analyzed data from the Coronary Artery Risk Development Study in Young Adults (CARDIA), which followed 1,238 women aged 18-30 for 30 years, with multiple assessments of glucose tolerance over the course of the study.

Women who breastfed for 6-12 months had a 48% reduction in the risk of diabetes (95% CI, 0.31-0.87), and those who breastfed for up to 6 months had a 25% lower risk (95% CI, 0.51-1.09), with the trend being significant.

In women with a history of gestational diabetes, those who did not breastfeed at all had a 2.08% higher excess risk of incident diabetes per year, compared with women who breastfed for at least 12 months. The increase in excess risk for the same comparison in women without a history of gestational diabetes was 0.48% per year.

Erica P. Gunderson, PhD, of Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Oakland, and her coauthors noted that previous meta-analyses of the effect of lactation on diabetes incidence or prevalence pointed to protective summary estimates of 9%-11% per year of lactation.

“Lactating women have lower circulating glucose in both fasting and post absorptive states, as well as lower insulin secretion, despite increased glucose production rates,” the authors wrote. “About 50 g of glucose per 24 hours is diverted into the mammary gland for milk synthesis via non–insulin mediated pathways.”

Studies in mice have also suggested that lactating animals have greater pancreatic beta-cell proliferation.

While the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommend breastfeeding for 1 year, only 55% of women in the United States are still breastfeeding at 6 months and 33% are still breastfeeding at 1 year after birth. Black women are also less likely to breastfeed, regardless of socioeconomic status or body size.

“Lactation is a natural biological process with the enormous potential to provide long-term benefits to maternal health, but has been underappreciated as a potential key strategy for early primary prevention of metabolic diseases in women across the childbearing years and beyond.”

The study and analyses were supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and two authors declared funding from pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Jan 16. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7978.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Duration of breastfeeding is inversely associated with risk of developing diabetes.

Major finding: Women who breastfeed for 12 months or more have a 47% lower risk of developing diabetes compared with women who do not breastfeed at all.

Data source: Analysis of data from the CARDIA population-based prospective cohort study in 1,238 women.

Disclosures: The study and analyses were supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and two authors declared funding from pharmaceutical companies.

Source: JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Jan 16. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7978.

Does maternal sleep position affect risk of stillbirth?

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR PRACTICE?

Encourage pregnant patients to not go to sleep in the supine position, especially those who:

- are obese

- have medical complications of pregnancy

- have a history of prior stillbirth

- smoke

- are of advanced maternal age

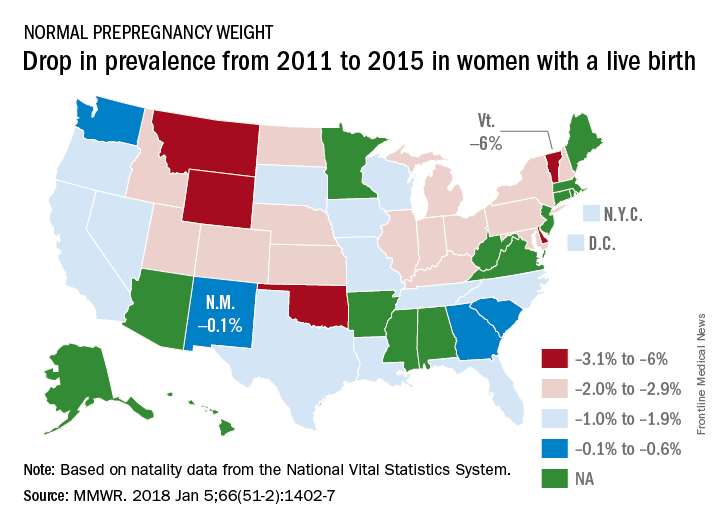

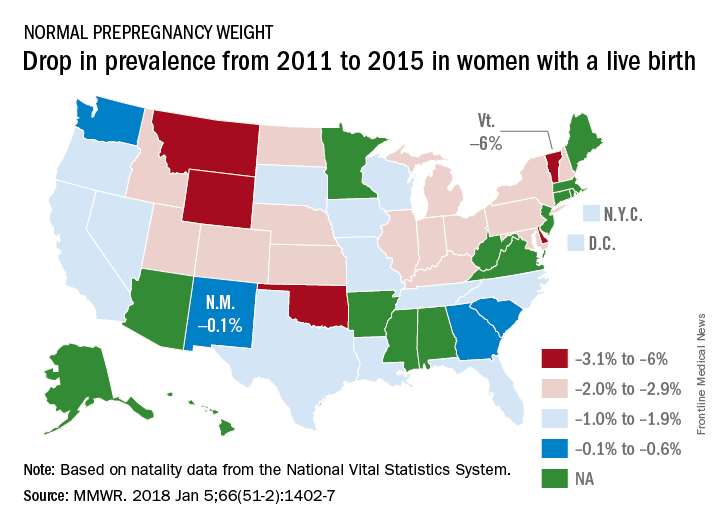

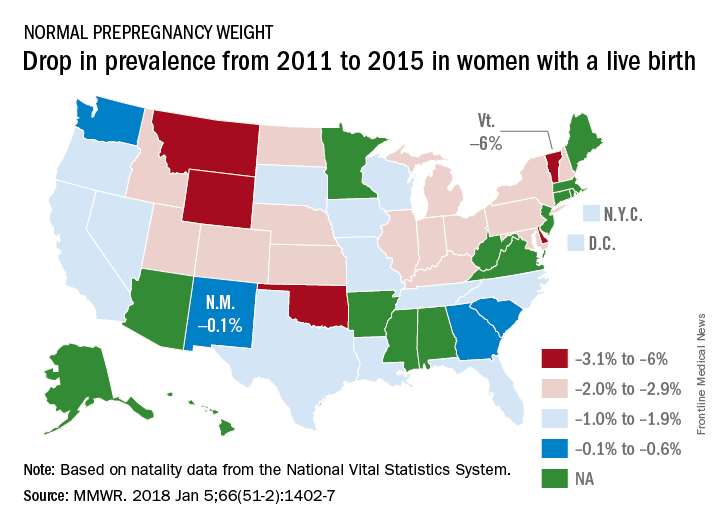

Normal prepregnancy weight becoming less normal

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The overall prevalence of normal prepregnancy weight declined from 47.3% to 45.1% over that period in 36 states, the District of Columbia, and New York City, which reports natality data separately from New York state. The decreases were statistically significant in 26 states and New York City, the CDC investigators reported (MMWR. 2018 Jan 5;66[51-2]:1402-7).

Based on data from 48 states, D.C., and New York City, the distribution of prevalence for the BMI categories in 2015 was 3.6% underweight, 45% normal weight, 25.8% overweight, and 25.6% obese, the investigators said.

The CDC analysis was based on natality data from the National Vital Statistics System. The standard birth certificate was revised in 2003 to include maternal height and prepregnancy weight, but only 38 jurisdictions were using it by 2011. By 2015, all states except Connecticut and New Jersey had adopted its use.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The overall prevalence of normal prepregnancy weight declined from 47.3% to 45.1% over that period in 36 states, the District of Columbia, and New York City, which reports natality data separately from New York state. The decreases were statistically significant in 26 states and New York City, the CDC investigators reported (MMWR. 2018 Jan 5;66[51-2]:1402-7).

Based on data from 48 states, D.C., and New York City, the distribution of prevalence for the BMI categories in 2015 was 3.6% underweight, 45% normal weight, 25.8% overweight, and 25.6% obese, the investigators said.

The CDC analysis was based on natality data from the National Vital Statistics System. The standard birth certificate was revised in 2003 to include maternal height and prepregnancy weight, but only 38 jurisdictions were using it by 2011. By 2015, all states except Connecticut and New Jersey had adopted its use.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The overall prevalence of normal prepregnancy weight declined from 47.3% to 45.1% over that period in 36 states, the District of Columbia, and New York City, which reports natality data separately from New York state. The decreases were statistically significant in 26 states and New York City, the CDC investigators reported (MMWR. 2018 Jan 5;66[51-2]:1402-7).

Based on data from 48 states, D.C., and New York City, the distribution of prevalence for the BMI categories in 2015 was 3.6% underweight, 45% normal weight, 25.8% overweight, and 25.6% obese, the investigators said.

The CDC analysis was based on natality data from the National Vital Statistics System. The standard birth certificate was revised in 2003 to include maternal height and prepregnancy weight, but only 38 jurisdictions were using it by 2011. By 2015, all states except Connecticut and New Jersey had adopted its use.

FROM MMWR

Prepregnancy obesity linked to bump in severe morbidity

Having a high or low prepregnancy body mass index was associated with a small absolute increase in severe maternal morbidity and mortality in a large, retrospective cohort study.

Some studies have suggested a link between obesity and pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, thromboembolism, and cesarean delivery. But one study suggested no link between higher BMI and risk of severe morbidity.

Adjustment for weight gain had no significant effect on the observed associations, Sarka Lisonkova, MD, PhD, of B.C. Women’s Hospital & Health Centre in Vancouver and her colleagues reported in JAMA.

Compared with normal weight women (BMI 18.5-24.9), women considered underweight (BMI less than 18.5) had an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) for mortality or severity morbidity of 1.2 (95% confidence interval, 1.0-1.3). Women who were overweight (BMI of 25.0-29.9) had an aOR of 1.1 (95% CI, 1.1-1.2).

The risk was also greater for women with class 1 obesity (BMI, 30.0-34.9; aOR, 1.1; 95% CI, 1.1-1.2), class 2 obesity (BMI, 35.0-39.9; aOR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1-1.3), and class 3 obesity (BMI, 40 or greater; aOR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.3-1.5).

In all cases, the absolute increases in mortality and severe morbidity, compared with normal weight women, were small, ranging from adjusted rated differences of 17.6 per 10,000 for overweight women to 61.1 per 10,000 women with class 3 obesity. Underweight women had an increase of 28.8 per 10,000.

Specifically, underweight women had a higher risk for antepartum and postpartum hemorrhage and acute renal failure, whereas women who were obese had increased risks for respiratory morbidity and thromboembolism, the researchers reported.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Lisonkova is supported by an award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. No other financial disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Lisonkova S et al. JAMA. 2017 Nov 14;318(18):1777-86.

Having a high or low prepregnancy body mass index was associated with a small absolute increase in severe maternal morbidity and mortality in a large, retrospective cohort study.

Some studies have suggested a link between obesity and pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, thromboembolism, and cesarean delivery. But one study suggested no link between higher BMI and risk of severe morbidity.

Adjustment for weight gain had no significant effect on the observed associations, Sarka Lisonkova, MD, PhD, of B.C. Women’s Hospital & Health Centre in Vancouver and her colleagues reported in JAMA.

Compared with normal weight women (BMI 18.5-24.9), women considered underweight (BMI less than 18.5) had an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) for mortality or severity morbidity of 1.2 (95% confidence interval, 1.0-1.3). Women who were overweight (BMI of 25.0-29.9) had an aOR of 1.1 (95% CI, 1.1-1.2).

The risk was also greater for women with class 1 obesity (BMI, 30.0-34.9; aOR, 1.1; 95% CI, 1.1-1.2), class 2 obesity (BMI, 35.0-39.9; aOR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1-1.3), and class 3 obesity (BMI, 40 or greater; aOR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.3-1.5).

In all cases, the absolute increases in mortality and severe morbidity, compared with normal weight women, were small, ranging from adjusted rated differences of 17.6 per 10,000 for overweight women to 61.1 per 10,000 women with class 3 obesity. Underweight women had an increase of 28.8 per 10,000.

Specifically, underweight women had a higher risk for antepartum and postpartum hemorrhage and acute renal failure, whereas women who were obese had increased risks for respiratory morbidity and thromboembolism, the researchers reported.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Lisonkova is supported by an award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. No other financial disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Lisonkova S et al. JAMA. 2017 Nov 14;318(18):1777-86.

Having a high or low prepregnancy body mass index was associated with a small absolute increase in severe maternal morbidity and mortality in a large, retrospective cohort study.

Some studies have suggested a link between obesity and pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, thromboembolism, and cesarean delivery. But one study suggested no link between higher BMI and risk of severe morbidity.

Adjustment for weight gain had no significant effect on the observed associations, Sarka Lisonkova, MD, PhD, of B.C. Women’s Hospital & Health Centre in Vancouver and her colleagues reported in JAMA.

Compared with normal weight women (BMI 18.5-24.9), women considered underweight (BMI less than 18.5) had an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) for mortality or severity morbidity of 1.2 (95% confidence interval, 1.0-1.3). Women who were overweight (BMI of 25.0-29.9) had an aOR of 1.1 (95% CI, 1.1-1.2).

The risk was also greater for women with class 1 obesity (BMI, 30.0-34.9; aOR, 1.1; 95% CI, 1.1-1.2), class 2 obesity (BMI, 35.0-39.9; aOR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1-1.3), and class 3 obesity (BMI, 40 or greater; aOR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.3-1.5).

In all cases, the absolute increases in mortality and severe morbidity, compared with normal weight women, were small, ranging from adjusted rated differences of 17.6 per 10,000 for overweight women to 61.1 per 10,000 women with class 3 obesity. Underweight women had an increase of 28.8 per 10,000.

Specifically, underweight women had a higher risk for antepartum and postpartum hemorrhage and acute renal failure, whereas women who were obese had increased risks for respiratory morbidity and thromboembolism, the researchers reported.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Lisonkova is supported by an award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. No other financial disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Lisonkova S et al. JAMA. 2017 Nov 14;318(18):1777-86.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Major finding: Severe morbidity and mortality risk was increased by 20% in women with prepregnancy class 2 obesity and 40% in women with class 3 obesity.

Study details: Retrospective analysis of 743,630 singleton pregnancies in Washington state between 2004 and 2013.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Lisonkova is supported by an award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. No other financial disclosures were reported.

Source: Lisonkova S et al. JAMA. 2017 Nov 14;318(18):1777-86.

views

There is a link between obesity and maternal complications during pregnancy, but a causal relationship has not been established. It could be that obese women are inherently at greater risk of mortality, or it could be that physicians have a harder time managing severe conditions in women who are obese.

One way to better understand the problem is to study obesity and severe maternal morbidity in pregnant women because the severe morbidity may precede and add to the increased mortality rates that are being seen among obese pregnant women.

The results of the current study support the idea that the association between class 3 obesity and severe complications in pregnancy may play a role in the increased risk of maternal mortality that was also observed.

The results also suggest that physicians caring for women of childbearing age should emphasize the importance of achieving optimal body mass index in reducing pregnancy complications.

Aaron B. Caughey, MD, PhD, is the chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Oregon Health and Science University, Portland. His comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2017;318[18]:1765-6). Dr. Caughey reported having no financial disclosures.