User login

Maternal short cervix and twins? Consider a pessary

DALLAS – Though cervical pessaries didn’t significantly reduce the rate of births before 34 weeks’ gestation when compared to vaginal progesterone for women with short cervixes and twin pregnancies, neonatal outcomes were improved with pessary use, according to the first randomized controlled trial that directly compared the two therapies.

Of 148 women who received pessaries, 24 (16.2%) delivered before 34 weeks’ gestation, compared with 33 of 149 women (22.1%) who received vaginal progesterone (relative risk 0.73, 95% confidence interval, 0.46-1.18; P = .24). Women who received pessaries were slightly more likely to carry their twin gestations to at least 37 weeks (79/148 versus 91/149; P = .05).

Certain perinatal outcomes were also better among the pessary group. The study measured a composite poor perinatal outcome of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission, intraventricular hemorrhage, respiratory distress syndrome, necrotizing enterocolitis, and neonatal sepsis. This composite poor outcome occurred in 18.6% of the pessary group, compared with 26.5% of the progesterone group (P = .02). Neonatal admissions were more common in the progesterone than in the pessary group (22.1% vs. 13.2%, P = .01)

The odds of having a baby with birth weight less than 2,500 g was also higher for those receiving progesterone, with 22.1% of the progesterone group and 13.2% of the pessary group delivering infants in this range (P less than .001).

Previous work has shown that vaginal progesterone was efficacious when compared with placebo in preventing preterm births for women who have a twin gestation and a short cervix, according to Vinh Dang, MD, the study’s first author. Similarly, he said, studies have shown that placement of a cervical pessary also reduces preterm births in the scenario of twin gestation and a short cervix.

“No randomized controlled trial has directly compared cervical pessary versus vaginal progesterone for the prevention of preterm birth” in this population, Dr. Dang said during a presentation at the Pregnancy Meeting, sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Accordingly, he and his colleagues at My Duc Hospital in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, conducted a comparative effectiveness trial to provide a head-to-head comparison of the use of cervical pessaries versus vaginal progesterone for women with twin gestations and short cervixes.

The investigators conducted a single-center, randomized controlled trial, enrolling women with either monochorionic or dichorionic twin pregnancies at between 16 and 22 weeks of gestation, with a cervix length of less than 38 mm, as assessed by two trained ultrasonographers.

At My Duc Hospital, 28.4% of women with twin pregnancies and cervical length less than 38 mm delivered earlier than 34 weeks. This meant that in order to detect a 14% reduction in preterm birth, the study would need to include 290 women for sufficient statistical power, Dr. Dang said.

Patients (n = 300) were randomized 1:1 to receive vaginal progesterone, begun on the day of enrollment, or cervical pessary placed within 1 week of study enrollment. Two patients in the pessary arm and one in the progesterone arm were lost to follow-up.

Patients were permitted to receive other therapies; 14 women in the pessary arm also received antibiotics and 1 received progesterone. In the progesterone group, 12 received antibiotics, and 4 patients were cotreated with cervical cerclage.

The study excluded women under 18 years of age, and those with a prior history of cervical surgery or cervical cerclage. Major known complications in the current pregnancy, such as twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, major congenital anomaly, fetal demise, and any symptoms of labor or late miscarriage were also grounds for exclusion.

Patient characteristics were similar between groups. The average age was 32 years. Most of the patients (83%-90%) were nulliparous, and more than 90% of the pregnancies were the result of assisted reproduction.

In addition to the primary outcome measure of preterm birth earlier than 34 weeks, the investigators tracked a number of obstetric and neonatal outcomes as secondary endpoints.

For the obstetric measures, Dr. Dang and his colleagues recorded deliveries that occurred before 28, 32, and 27 weeks’ gestation, whether labor was induced and if tocolytics or corticosteroids were used, mode of delivery, and proportion of live births. The number of days of admission for preterm labor, presence of chorioamnionitis, and occurrence of other maternal morbidity were also measured.

Dr. Dang and his colleagues also tracked birth weight, congenital anomalies, and 1- and 5-minute Apgar scores.

A prespecified subgroup analysis of women with even shorter cervixes – less than 28 mm – showed a significant reduction in preterm birth before 34 weeks in addition to the significant improvement in neonatal outcomes.

One author reported being a consultant for ObsEva, Merck, and Guerbet. The other authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Dang V et al. The Pregnancy Meeting Abstract LB03

DALLAS – Though cervical pessaries didn’t significantly reduce the rate of births before 34 weeks’ gestation when compared to vaginal progesterone for women with short cervixes and twin pregnancies, neonatal outcomes were improved with pessary use, according to the first randomized controlled trial that directly compared the two therapies.

Of 148 women who received pessaries, 24 (16.2%) delivered before 34 weeks’ gestation, compared with 33 of 149 women (22.1%) who received vaginal progesterone (relative risk 0.73, 95% confidence interval, 0.46-1.18; P = .24). Women who received pessaries were slightly more likely to carry their twin gestations to at least 37 weeks (79/148 versus 91/149; P = .05).

Certain perinatal outcomes were also better among the pessary group. The study measured a composite poor perinatal outcome of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission, intraventricular hemorrhage, respiratory distress syndrome, necrotizing enterocolitis, and neonatal sepsis. This composite poor outcome occurred in 18.6% of the pessary group, compared with 26.5% of the progesterone group (P = .02). Neonatal admissions were more common in the progesterone than in the pessary group (22.1% vs. 13.2%, P = .01)

The odds of having a baby with birth weight less than 2,500 g was also higher for those receiving progesterone, with 22.1% of the progesterone group and 13.2% of the pessary group delivering infants in this range (P less than .001).

Previous work has shown that vaginal progesterone was efficacious when compared with placebo in preventing preterm births for women who have a twin gestation and a short cervix, according to Vinh Dang, MD, the study’s first author. Similarly, he said, studies have shown that placement of a cervical pessary also reduces preterm births in the scenario of twin gestation and a short cervix.

“No randomized controlled trial has directly compared cervical pessary versus vaginal progesterone for the prevention of preterm birth” in this population, Dr. Dang said during a presentation at the Pregnancy Meeting, sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Accordingly, he and his colleagues at My Duc Hospital in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, conducted a comparative effectiveness trial to provide a head-to-head comparison of the use of cervical pessaries versus vaginal progesterone for women with twin gestations and short cervixes.

The investigators conducted a single-center, randomized controlled trial, enrolling women with either monochorionic or dichorionic twin pregnancies at between 16 and 22 weeks of gestation, with a cervix length of less than 38 mm, as assessed by two trained ultrasonographers.

At My Duc Hospital, 28.4% of women with twin pregnancies and cervical length less than 38 mm delivered earlier than 34 weeks. This meant that in order to detect a 14% reduction in preterm birth, the study would need to include 290 women for sufficient statistical power, Dr. Dang said.

Patients (n = 300) were randomized 1:1 to receive vaginal progesterone, begun on the day of enrollment, or cervical pessary placed within 1 week of study enrollment. Two patients in the pessary arm and one in the progesterone arm were lost to follow-up.

Patients were permitted to receive other therapies; 14 women in the pessary arm also received antibiotics and 1 received progesterone. In the progesterone group, 12 received antibiotics, and 4 patients were cotreated with cervical cerclage.

The study excluded women under 18 years of age, and those with a prior history of cervical surgery or cervical cerclage. Major known complications in the current pregnancy, such as twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, major congenital anomaly, fetal demise, and any symptoms of labor or late miscarriage were also grounds for exclusion.

Patient characteristics were similar between groups. The average age was 32 years. Most of the patients (83%-90%) were nulliparous, and more than 90% of the pregnancies were the result of assisted reproduction.

In addition to the primary outcome measure of preterm birth earlier than 34 weeks, the investigators tracked a number of obstetric and neonatal outcomes as secondary endpoints.

For the obstetric measures, Dr. Dang and his colleagues recorded deliveries that occurred before 28, 32, and 27 weeks’ gestation, whether labor was induced and if tocolytics or corticosteroids were used, mode of delivery, and proportion of live births. The number of days of admission for preterm labor, presence of chorioamnionitis, and occurrence of other maternal morbidity were also measured.

Dr. Dang and his colleagues also tracked birth weight, congenital anomalies, and 1- and 5-minute Apgar scores.

A prespecified subgroup analysis of women with even shorter cervixes – less than 28 mm – showed a significant reduction in preterm birth before 34 weeks in addition to the significant improvement in neonatal outcomes.

One author reported being a consultant for ObsEva, Merck, and Guerbet. The other authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Dang V et al. The Pregnancy Meeting Abstract LB03

DALLAS – Though cervical pessaries didn’t significantly reduce the rate of births before 34 weeks’ gestation when compared to vaginal progesterone for women with short cervixes and twin pregnancies, neonatal outcomes were improved with pessary use, according to the first randomized controlled trial that directly compared the two therapies.

Of 148 women who received pessaries, 24 (16.2%) delivered before 34 weeks’ gestation, compared with 33 of 149 women (22.1%) who received vaginal progesterone (relative risk 0.73, 95% confidence interval, 0.46-1.18; P = .24). Women who received pessaries were slightly more likely to carry their twin gestations to at least 37 weeks (79/148 versus 91/149; P = .05).

Certain perinatal outcomes were also better among the pessary group. The study measured a composite poor perinatal outcome of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission, intraventricular hemorrhage, respiratory distress syndrome, necrotizing enterocolitis, and neonatal sepsis. This composite poor outcome occurred in 18.6% of the pessary group, compared with 26.5% of the progesterone group (P = .02). Neonatal admissions were more common in the progesterone than in the pessary group (22.1% vs. 13.2%, P = .01)

The odds of having a baby with birth weight less than 2,500 g was also higher for those receiving progesterone, with 22.1% of the progesterone group and 13.2% of the pessary group delivering infants in this range (P less than .001).

Previous work has shown that vaginal progesterone was efficacious when compared with placebo in preventing preterm births for women who have a twin gestation and a short cervix, according to Vinh Dang, MD, the study’s first author. Similarly, he said, studies have shown that placement of a cervical pessary also reduces preterm births in the scenario of twin gestation and a short cervix.

“No randomized controlled trial has directly compared cervical pessary versus vaginal progesterone for the prevention of preterm birth” in this population, Dr. Dang said during a presentation at the Pregnancy Meeting, sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Accordingly, he and his colleagues at My Duc Hospital in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, conducted a comparative effectiveness trial to provide a head-to-head comparison of the use of cervical pessaries versus vaginal progesterone for women with twin gestations and short cervixes.

The investigators conducted a single-center, randomized controlled trial, enrolling women with either monochorionic or dichorionic twin pregnancies at between 16 and 22 weeks of gestation, with a cervix length of less than 38 mm, as assessed by two trained ultrasonographers.

At My Duc Hospital, 28.4% of women with twin pregnancies and cervical length less than 38 mm delivered earlier than 34 weeks. This meant that in order to detect a 14% reduction in preterm birth, the study would need to include 290 women for sufficient statistical power, Dr. Dang said.

Patients (n = 300) were randomized 1:1 to receive vaginal progesterone, begun on the day of enrollment, or cervical pessary placed within 1 week of study enrollment. Two patients in the pessary arm and one in the progesterone arm were lost to follow-up.

Patients were permitted to receive other therapies; 14 women in the pessary arm also received antibiotics and 1 received progesterone. In the progesterone group, 12 received antibiotics, and 4 patients were cotreated with cervical cerclage.

The study excluded women under 18 years of age, and those with a prior history of cervical surgery or cervical cerclage. Major known complications in the current pregnancy, such as twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, major congenital anomaly, fetal demise, and any symptoms of labor or late miscarriage were also grounds for exclusion.

Patient characteristics were similar between groups. The average age was 32 years. Most of the patients (83%-90%) were nulliparous, and more than 90% of the pregnancies were the result of assisted reproduction.

In addition to the primary outcome measure of preterm birth earlier than 34 weeks, the investigators tracked a number of obstetric and neonatal outcomes as secondary endpoints.

For the obstetric measures, Dr. Dang and his colleagues recorded deliveries that occurred before 28, 32, and 27 weeks’ gestation, whether labor was induced and if tocolytics or corticosteroids were used, mode of delivery, and proportion of live births. The number of days of admission for preterm labor, presence of chorioamnionitis, and occurrence of other maternal morbidity were also measured.

Dr. Dang and his colleagues also tracked birth weight, congenital anomalies, and 1- and 5-minute Apgar scores.

A prespecified subgroup analysis of women with even shorter cervixes – less than 28 mm – showed a significant reduction in preterm birth before 34 weeks in addition to the significant improvement in neonatal outcomes.

One author reported being a consultant for ObsEva, Merck, and Guerbet. The other authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Dang V et al. The Pregnancy Meeting Abstract LB03

REPORTING FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Poor neonatal outcome occurred in 18.6% of those receiving pessary, compared with 26.5% of those receiving vaginal progesterone (P = .02).

Study details: Randomized controlled trial of cervical pessary versus vaginal progesterone for women with twin gestation and cervical length less than 38 mm.

Disclosures: One author reported funding from Obseva, Merck, and Guerbet. The other authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Dang V et al. The Pregnancy Meeting Abstract LB03.

Ibuprofen appears safe with preeclampsia, study says

DALLAS – Compared to acetaminophen, ibuprofen does not prolong the time needed to control postpartum hypertension in women who experience preeclampsia with severe features, Nathan Blue MD, reported at the Pregnancy Meeting, sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Ibuprofen did not exacerbate postpartum hypertension, as some studies have suggested, and women randomized to it for postpartum pain control reached their target blood pressure at a mean of 35 hours after delivery, similar to the 38 hours needed among women receiving acetaminophen.

Dr. Blue’s findings contradict the recommendation by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists to avoid the use of ibuprofen and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for pain control in women who experience preeclampsia or other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

“While our study was not meant to answer all questions about the potential problems of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories [in this population], I would conclude from these results that providers and patients can make a decision together and feel good about the use of NSAIDs,” in the presence of postpartum hypertension, said Dr. Blue, a fellow at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

These concerns led ACOG to issue its recommendation in 2013 against the use of NSAIDs in pregnant women with hypertension.

“This is problematic, because NSAIDs are particularly well-suited to address obstetric pain,” Dr. Blue said at the meeting. “They have been shown to be better than acetaminophen for perineal injury and they are associated with a reduced use of opioids after cesarean section.”

To investigate the effect of ibuprofen on postpartum hypertension, Dr. Blue and his colleagues conducted a double-blind randomized controlled trial of 100 women with preeclampsia with severe features. The study population also included women who had chronic hypertension complicated by preeclampsia with severe features, and women with HELLP syndrome – a constellation of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count.

Women were randomized to either 600 mg ibuprofen or 650 mg acetaminophen every 6 hours, around the clock, with the first dose delivered within 6 hours of delivery. All patients received at least eight doses of their assigned medication. The primary endpoint was the time required to achieve blood pressure control. “We defined blood pressure control as the number of hours from delivery to the last reading of at least 160/110 mm Hg before discharge,” Dr. Blue said. “Our rationale here was that persistence of a blood pressure of that level would require a delay in discharge of at least 24 hours.”

The study had a number of secondary outcomes, including time from delivery to last blood pressure reading of at least 150/100 mm Hg; postpartum mean arterial pressure; any blood pressure reading of 160/110 mm Hg or higher; need for antihypertensive drugs at discharge; prolongation of hospital stay due to hypertension; and the need for postpartum opioids.

There was a 6-week follow-up assessment, at which time women reported any continued antihypertensive or opioid use, obstetrical triage visits after discharge, and hospital readmission.

The study cohort was well-balanced at baseline. Women were a mean of 30 years old; about a third were nulliparous, and half had a vaginal delivery. Chronic hypertension requiring medication was present in about 15%. The maximum blood pressure before delivery was about 180/107.

There was no significant difference between the ibuprofen group and the acetaminophen group in the primary endpoint of time to blood pressure of 160/110 mm Hg or below (35.3 vs. 38 hours). Nor were there significant differences in any of the secondary endpoints, including time to achieve a blood pressure of less than 150/100 mm Hg (58 vs. 57 hours), postpartum mean arterial pressure, maximum systolic and diastolic blood pressures, or the number of women who needed a short-acting antihypertensive (30 vs. 26) and who went home on an antihypertensive (33 vs. 31).

There were also no significant between-group differences in opioid use, either on postpartum days 0, 1, or 2. The total morphine equivalent dose for each group was likewise not significantly different (77 vs. 88 mg).

Dr. Blue was able to contact 77 women at 6 weeks’ postpartum. He found that 6-week outcomes were also similar. There were no significant differences in the number who required continuing antihypertensive or opioids, no difference in obstetric triage visits, and no difference in hospital readmission.

“Our study does not support the hypothesis that NSAIDs adversely affect blood pressure control in patients with preeclampsia,” he said. “Not only did we not find a difference in the primary outcome, we found not even a suggestion of difference in any measure of blood pressure control.”

The University of New Mexico sponsored the study. Dr. Blue reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Blue et al. The Pregnancy Meeting 2018 Abstract LB04.

DALLAS – Compared to acetaminophen, ibuprofen does not prolong the time needed to control postpartum hypertension in women who experience preeclampsia with severe features, Nathan Blue MD, reported at the Pregnancy Meeting, sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Ibuprofen did not exacerbate postpartum hypertension, as some studies have suggested, and women randomized to it for postpartum pain control reached their target blood pressure at a mean of 35 hours after delivery, similar to the 38 hours needed among women receiving acetaminophen.

Dr. Blue’s findings contradict the recommendation by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists to avoid the use of ibuprofen and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for pain control in women who experience preeclampsia or other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

“While our study was not meant to answer all questions about the potential problems of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories [in this population], I would conclude from these results that providers and patients can make a decision together and feel good about the use of NSAIDs,” in the presence of postpartum hypertension, said Dr. Blue, a fellow at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

These concerns led ACOG to issue its recommendation in 2013 against the use of NSAIDs in pregnant women with hypertension.

“This is problematic, because NSAIDs are particularly well-suited to address obstetric pain,” Dr. Blue said at the meeting. “They have been shown to be better than acetaminophen for perineal injury and they are associated with a reduced use of opioids after cesarean section.”

To investigate the effect of ibuprofen on postpartum hypertension, Dr. Blue and his colleagues conducted a double-blind randomized controlled trial of 100 women with preeclampsia with severe features. The study population also included women who had chronic hypertension complicated by preeclampsia with severe features, and women with HELLP syndrome – a constellation of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count.

Women were randomized to either 600 mg ibuprofen or 650 mg acetaminophen every 6 hours, around the clock, with the first dose delivered within 6 hours of delivery. All patients received at least eight doses of their assigned medication. The primary endpoint was the time required to achieve blood pressure control. “We defined blood pressure control as the number of hours from delivery to the last reading of at least 160/110 mm Hg before discharge,” Dr. Blue said. “Our rationale here was that persistence of a blood pressure of that level would require a delay in discharge of at least 24 hours.”

The study had a number of secondary outcomes, including time from delivery to last blood pressure reading of at least 150/100 mm Hg; postpartum mean arterial pressure; any blood pressure reading of 160/110 mm Hg or higher; need for antihypertensive drugs at discharge; prolongation of hospital stay due to hypertension; and the need for postpartum opioids.

There was a 6-week follow-up assessment, at which time women reported any continued antihypertensive or opioid use, obstetrical triage visits after discharge, and hospital readmission.

The study cohort was well-balanced at baseline. Women were a mean of 30 years old; about a third were nulliparous, and half had a vaginal delivery. Chronic hypertension requiring medication was present in about 15%. The maximum blood pressure before delivery was about 180/107.

There was no significant difference between the ibuprofen group and the acetaminophen group in the primary endpoint of time to blood pressure of 160/110 mm Hg or below (35.3 vs. 38 hours). Nor were there significant differences in any of the secondary endpoints, including time to achieve a blood pressure of less than 150/100 mm Hg (58 vs. 57 hours), postpartum mean arterial pressure, maximum systolic and diastolic blood pressures, or the number of women who needed a short-acting antihypertensive (30 vs. 26) and who went home on an antihypertensive (33 vs. 31).

There were also no significant between-group differences in opioid use, either on postpartum days 0, 1, or 2. The total morphine equivalent dose for each group was likewise not significantly different (77 vs. 88 mg).

Dr. Blue was able to contact 77 women at 6 weeks’ postpartum. He found that 6-week outcomes were also similar. There were no significant differences in the number who required continuing antihypertensive or opioids, no difference in obstetric triage visits, and no difference in hospital readmission.

“Our study does not support the hypothesis that NSAIDs adversely affect blood pressure control in patients with preeclampsia,” he said. “Not only did we not find a difference in the primary outcome, we found not even a suggestion of difference in any measure of blood pressure control.”

The University of New Mexico sponsored the study. Dr. Blue reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Blue et al. The Pregnancy Meeting 2018 Abstract LB04.

DALLAS – Compared to acetaminophen, ibuprofen does not prolong the time needed to control postpartum hypertension in women who experience preeclampsia with severe features, Nathan Blue MD, reported at the Pregnancy Meeting, sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

Ibuprofen did not exacerbate postpartum hypertension, as some studies have suggested, and women randomized to it for postpartum pain control reached their target blood pressure at a mean of 35 hours after delivery, similar to the 38 hours needed among women receiving acetaminophen.

Dr. Blue’s findings contradict the recommendation by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists to avoid the use of ibuprofen and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for pain control in women who experience preeclampsia or other hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

“While our study was not meant to answer all questions about the potential problems of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories [in this population], I would conclude from these results that providers and patients can make a decision together and feel good about the use of NSAIDs,” in the presence of postpartum hypertension, said Dr. Blue, a fellow at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

These concerns led ACOG to issue its recommendation in 2013 against the use of NSAIDs in pregnant women with hypertension.

“This is problematic, because NSAIDs are particularly well-suited to address obstetric pain,” Dr. Blue said at the meeting. “They have been shown to be better than acetaminophen for perineal injury and they are associated with a reduced use of opioids after cesarean section.”

To investigate the effect of ibuprofen on postpartum hypertension, Dr. Blue and his colleagues conducted a double-blind randomized controlled trial of 100 women with preeclampsia with severe features. The study population also included women who had chronic hypertension complicated by preeclampsia with severe features, and women with HELLP syndrome – a constellation of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count.

Women were randomized to either 600 mg ibuprofen or 650 mg acetaminophen every 6 hours, around the clock, with the first dose delivered within 6 hours of delivery. All patients received at least eight doses of their assigned medication. The primary endpoint was the time required to achieve blood pressure control. “We defined blood pressure control as the number of hours from delivery to the last reading of at least 160/110 mm Hg before discharge,” Dr. Blue said. “Our rationale here was that persistence of a blood pressure of that level would require a delay in discharge of at least 24 hours.”

The study had a number of secondary outcomes, including time from delivery to last blood pressure reading of at least 150/100 mm Hg; postpartum mean arterial pressure; any blood pressure reading of 160/110 mm Hg or higher; need for antihypertensive drugs at discharge; prolongation of hospital stay due to hypertension; and the need for postpartum opioids.

There was a 6-week follow-up assessment, at which time women reported any continued antihypertensive or opioid use, obstetrical triage visits after discharge, and hospital readmission.

The study cohort was well-balanced at baseline. Women were a mean of 30 years old; about a third were nulliparous, and half had a vaginal delivery. Chronic hypertension requiring medication was present in about 15%. The maximum blood pressure before delivery was about 180/107.

There was no significant difference between the ibuprofen group and the acetaminophen group in the primary endpoint of time to blood pressure of 160/110 mm Hg or below (35.3 vs. 38 hours). Nor were there significant differences in any of the secondary endpoints, including time to achieve a blood pressure of less than 150/100 mm Hg (58 vs. 57 hours), postpartum mean arterial pressure, maximum systolic and diastolic blood pressures, or the number of women who needed a short-acting antihypertensive (30 vs. 26) and who went home on an antihypertensive (33 vs. 31).

There were also no significant between-group differences in opioid use, either on postpartum days 0, 1, or 2. The total morphine equivalent dose for each group was likewise not significantly different (77 vs. 88 mg).

Dr. Blue was able to contact 77 women at 6 weeks’ postpartum. He found that 6-week outcomes were also similar. There were no significant differences in the number who required continuing antihypertensive or opioids, no difference in obstetric triage visits, and no difference in hospital readmission.

“Our study does not support the hypothesis that NSAIDs adversely affect blood pressure control in patients with preeclampsia,” he said. “Not only did we not find a difference in the primary outcome, we found not even a suggestion of difference in any measure of blood pressure control.”

The University of New Mexico sponsored the study. Dr. Blue reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Blue et al. The Pregnancy Meeting 2018 Abstract LB04.

REPORTING FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The mean time to achieve postpartum blood pressure control was 35 hours in the ibuprofen group and 38 hours in the acetaminophen group.

Study details: The randomized study comprised 100 women.

Disclosures: The University of New Mexico sponsored the study. Dr. Blue reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Blue N et al. The Pregnancy Meeting 2018 Abstract LB04.

Is elective induction at 39 weeks a good idea?

DALLAS – Elective inductions at 39 weeks’ gestation were safe for the newborn and conferred dual benefits upon first-time mothers, reducing the risk of cesarean delivery by 16% and pregnancy-related hypertensive disorder by 36%, compared with women managed expectantly.

Infants delivered by elective inductions were smaller than those born to expectantly managed women and experienced a 29% reduction in the need for respiratory support at birth, William A. Grobman, MD, reported at the meeting, sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. They were no more likely than infants in the comparator group to experience dangerous perinatal outcomes, including low Apgar scores, meconium inhalation, hypoxia, or birth trauma, said Dr. Grobman, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

The new data, however, may set a new standard by which to make this decision, Dr. Grobman said.

“I will leave it up to the professional organizations to determine the final outcome of these data, but it’s important to understand that the Choosing Wisely recommendation was based on observational data that essentially used an incorrect clinical comparator” of spontaneous labor, he said. The large study that Dr. Grobman and his colleagues conducted used expectant management (EM) as the comparator, allowing women to continue up to 42 weeks’ gestation. Using this comparator, he said, “Our data are largely with almost every observational study” and with a recently published randomized controlled trial by Kate F. Walker, a clinical research fellow at the University of Nottingham (England).

That study determined that labor induction between 39 weeks and 39 weeks, 6 days, in women older than 35 years had no significant effect on the rate of cesarean section and no adverse short-term effects on maternal or neonatal outcomes.

Dr. Grobman conducted his randomized trial at 41 hospitals in the National Institutes of Health’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network.

It randomized 6,106 healthy, nulliparous women to either elective induction from 39 weeks to 39 weeks, 4 days, or to EM. These women were asked to forgo elective delivery before 40 weeks, 5 days, but to be delivered by 42 weeks, 2 days.

The primary perinatal outcome was a composite endpoint that included fetal or neonatal death; respiratory support in the first 72 hours; 5-minute Apgar of 3 or lower; hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy; seizure; infection; meconium aspiration syndrome; birth trauma; intracranial or subgaleal hemorrhage; and hypotension requiring vasopressors.

The primary maternal outcome was a composite of cesarean delivery; hypertensive disorder of pregnancy; postpartum hemorrhage; chorioamnionitis; postpartum infection; labor pain; and the Labour Agentry Scale, a midwife-created measure of a laboring woman’s perception of her birth experience.

Women were a mean of 23.5 years old; about 44% of each group was privately insured. Prior pregnancy loss was more common among those randomized to EM (25.6% vs. 22.8%). Just over half were obese, with a body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2. Most (about 63%) had an unfavorable cervix, with a Bishop score of less than 5. The trial specified no particular induction regimen, Dr. Grobman said. “There were a variety of ripening agents and oxytocin regimens used.”

Infants in the elective induction group were born significantly earlier than were those in the EM group (39.3 vs. 40 weeks) and weighed significantly less (3,300 g vs. 3,380 g). Induction was safe for the newborn, with the primary endpoint occurring in 4.4%, compared with 5.4% of those in the EM group – not significantly different.

When investigators examined each outcome in the perinatal composite individually, only one – early respiratory support – was significantly different from the EM group. Infants in the induction group were 29% less likely to need respiratory support in the first 72 hours (3% vs. 4.2%; relative risk, 0.71). The rate of cesarean delivery also was significantly less among the induction group (18.6% vs. 22.2%; RR, 0.84).

None of these outcomes changed when the investigators controlled for race/ethnicity, Bishop score of less than 5, body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or more, or advanced maternal age.

Induction also was safe for mothers, and conferred a significant 36% reduction in the risk of pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders (9.1% vs. 14.1%; RR, 0.64). All other maternal outcomes were similar between the two groups.

The Agentry scale results also showed that women who were induced felt they were more in control of their birth experience, both at delivery and at 6 weeks’ postpartum. They also rated their worst labor pain and overall labor pain as significantly less than did women in the EM group.

“Our result suggest that policies directed toward avoidance of elective labor induction in nulliparous women would be unlikely to reduce the rate of cesarean section on a population level,” Dr. Grobman said. “To the contrary, our data show that, for every 28 nulliparous women to undergo elective induction at 39 weeks, one cesarean section would be avoided. Additionally, the number needed to treat to prevent one case of neonatal respiratory support is 83, and to prevent one case of hypertensive disease of pregnancy, 20. Our results should provide information useful to women as they consider their options, and can be incorporated into shared decision-making discussions with the provider.”

The study was sponsored by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Grobman had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Grobman W. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S601.

DALLAS – Elective inductions at 39 weeks’ gestation were safe for the newborn and conferred dual benefits upon first-time mothers, reducing the risk of cesarean delivery by 16% and pregnancy-related hypertensive disorder by 36%, compared with women managed expectantly.

Infants delivered by elective inductions were smaller than those born to expectantly managed women and experienced a 29% reduction in the need for respiratory support at birth, William A. Grobman, MD, reported at the meeting, sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. They were no more likely than infants in the comparator group to experience dangerous perinatal outcomes, including low Apgar scores, meconium inhalation, hypoxia, or birth trauma, said Dr. Grobman, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

The new data, however, may set a new standard by which to make this decision, Dr. Grobman said.

“I will leave it up to the professional organizations to determine the final outcome of these data, but it’s important to understand that the Choosing Wisely recommendation was based on observational data that essentially used an incorrect clinical comparator” of spontaneous labor, he said. The large study that Dr. Grobman and his colleagues conducted used expectant management (EM) as the comparator, allowing women to continue up to 42 weeks’ gestation. Using this comparator, he said, “Our data are largely with almost every observational study” and with a recently published randomized controlled trial by Kate F. Walker, a clinical research fellow at the University of Nottingham (England).

That study determined that labor induction between 39 weeks and 39 weeks, 6 days, in women older than 35 years had no significant effect on the rate of cesarean section and no adverse short-term effects on maternal or neonatal outcomes.

Dr. Grobman conducted his randomized trial at 41 hospitals in the National Institutes of Health’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network.

It randomized 6,106 healthy, nulliparous women to either elective induction from 39 weeks to 39 weeks, 4 days, or to EM. These women were asked to forgo elective delivery before 40 weeks, 5 days, but to be delivered by 42 weeks, 2 days.

The primary perinatal outcome was a composite endpoint that included fetal or neonatal death; respiratory support in the first 72 hours; 5-minute Apgar of 3 or lower; hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy; seizure; infection; meconium aspiration syndrome; birth trauma; intracranial or subgaleal hemorrhage; and hypotension requiring vasopressors.

The primary maternal outcome was a composite of cesarean delivery; hypertensive disorder of pregnancy; postpartum hemorrhage; chorioamnionitis; postpartum infection; labor pain; and the Labour Agentry Scale, a midwife-created measure of a laboring woman’s perception of her birth experience.

Women were a mean of 23.5 years old; about 44% of each group was privately insured. Prior pregnancy loss was more common among those randomized to EM (25.6% vs. 22.8%). Just over half were obese, with a body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2. Most (about 63%) had an unfavorable cervix, with a Bishop score of less than 5. The trial specified no particular induction regimen, Dr. Grobman said. “There were a variety of ripening agents and oxytocin regimens used.”

Infants in the elective induction group were born significantly earlier than were those in the EM group (39.3 vs. 40 weeks) and weighed significantly less (3,300 g vs. 3,380 g). Induction was safe for the newborn, with the primary endpoint occurring in 4.4%, compared with 5.4% of those in the EM group – not significantly different.

When investigators examined each outcome in the perinatal composite individually, only one – early respiratory support – was significantly different from the EM group. Infants in the induction group were 29% less likely to need respiratory support in the first 72 hours (3% vs. 4.2%; relative risk, 0.71). The rate of cesarean delivery also was significantly less among the induction group (18.6% vs. 22.2%; RR, 0.84).

None of these outcomes changed when the investigators controlled for race/ethnicity, Bishop score of less than 5, body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or more, or advanced maternal age.

Induction also was safe for mothers, and conferred a significant 36% reduction in the risk of pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders (9.1% vs. 14.1%; RR, 0.64). All other maternal outcomes were similar between the two groups.

The Agentry scale results also showed that women who were induced felt they were more in control of their birth experience, both at delivery and at 6 weeks’ postpartum. They also rated their worst labor pain and overall labor pain as significantly less than did women in the EM group.

“Our result suggest that policies directed toward avoidance of elective labor induction in nulliparous women would be unlikely to reduce the rate of cesarean section on a population level,” Dr. Grobman said. “To the contrary, our data show that, for every 28 nulliparous women to undergo elective induction at 39 weeks, one cesarean section would be avoided. Additionally, the number needed to treat to prevent one case of neonatal respiratory support is 83, and to prevent one case of hypertensive disease of pregnancy, 20. Our results should provide information useful to women as they consider their options, and can be incorporated into shared decision-making discussions with the provider.”

The study was sponsored by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Grobman had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Grobman W. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S601.

DALLAS – Elective inductions at 39 weeks’ gestation were safe for the newborn and conferred dual benefits upon first-time mothers, reducing the risk of cesarean delivery by 16% and pregnancy-related hypertensive disorder by 36%, compared with women managed expectantly.

Infants delivered by elective inductions were smaller than those born to expectantly managed women and experienced a 29% reduction in the need for respiratory support at birth, William A. Grobman, MD, reported at the meeting, sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. They were no more likely than infants in the comparator group to experience dangerous perinatal outcomes, including low Apgar scores, meconium inhalation, hypoxia, or birth trauma, said Dr. Grobman, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

The new data, however, may set a new standard by which to make this decision, Dr. Grobman said.

“I will leave it up to the professional organizations to determine the final outcome of these data, but it’s important to understand that the Choosing Wisely recommendation was based on observational data that essentially used an incorrect clinical comparator” of spontaneous labor, he said. The large study that Dr. Grobman and his colleagues conducted used expectant management (EM) as the comparator, allowing women to continue up to 42 weeks’ gestation. Using this comparator, he said, “Our data are largely with almost every observational study” and with a recently published randomized controlled trial by Kate F. Walker, a clinical research fellow at the University of Nottingham (England).

That study determined that labor induction between 39 weeks and 39 weeks, 6 days, in women older than 35 years had no significant effect on the rate of cesarean section and no adverse short-term effects on maternal or neonatal outcomes.

Dr. Grobman conducted his randomized trial at 41 hospitals in the National Institutes of Health’s Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network.

It randomized 6,106 healthy, nulliparous women to either elective induction from 39 weeks to 39 weeks, 4 days, or to EM. These women were asked to forgo elective delivery before 40 weeks, 5 days, but to be delivered by 42 weeks, 2 days.

The primary perinatal outcome was a composite endpoint that included fetal or neonatal death; respiratory support in the first 72 hours; 5-minute Apgar of 3 or lower; hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy; seizure; infection; meconium aspiration syndrome; birth trauma; intracranial or subgaleal hemorrhage; and hypotension requiring vasopressors.

The primary maternal outcome was a composite of cesarean delivery; hypertensive disorder of pregnancy; postpartum hemorrhage; chorioamnionitis; postpartum infection; labor pain; and the Labour Agentry Scale, a midwife-created measure of a laboring woman’s perception of her birth experience.

Women were a mean of 23.5 years old; about 44% of each group was privately insured. Prior pregnancy loss was more common among those randomized to EM (25.6% vs. 22.8%). Just over half were obese, with a body mass index of at least 30 kg/m2. Most (about 63%) had an unfavorable cervix, with a Bishop score of less than 5. The trial specified no particular induction regimen, Dr. Grobman said. “There were a variety of ripening agents and oxytocin regimens used.”

Infants in the elective induction group were born significantly earlier than were those in the EM group (39.3 vs. 40 weeks) and weighed significantly less (3,300 g vs. 3,380 g). Induction was safe for the newborn, with the primary endpoint occurring in 4.4%, compared with 5.4% of those in the EM group – not significantly different.

When investigators examined each outcome in the perinatal composite individually, only one – early respiratory support – was significantly different from the EM group. Infants in the induction group were 29% less likely to need respiratory support in the first 72 hours (3% vs. 4.2%; relative risk, 0.71). The rate of cesarean delivery also was significantly less among the induction group (18.6% vs. 22.2%; RR, 0.84).

None of these outcomes changed when the investigators controlled for race/ethnicity, Bishop score of less than 5, body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or more, or advanced maternal age.

Induction also was safe for mothers, and conferred a significant 36% reduction in the risk of pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders (9.1% vs. 14.1%; RR, 0.64). All other maternal outcomes were similar between the two groups.

The Agentry scale results also showed that women who were induced felt they were more in control of their birth experience, both at delivery and at 6 weeks’ postpartum. They also rated their worst labor pain and overall labor pain as significantly less than did women in the EM group.

“Our result suggest that policies directed toward avoidance of elective labor induction in nulliparous women would be unlikely to reduce the rate of cesarean section on a population level,” Dr. Grobman said. “To the contrary, our data show that, for every 28 nulliparous women to undergo elective induction at 39 weeks, one cesarean section would be avoided. Additionally, the number needed to treat to prevent one case of neonatal respiratory support is 83, and to prevent one case of hypertensive disease of pregnancy, 20. Our results should provide information useful to women as they consider their options, and can be incorporated into shared decision-making discussions with the provider.”

The study was sponsored by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Grobman had no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Grobman W. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S601.

AT THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Key clinical point: Induction at 39 weeks conferred some health benefits to nulliparous women and didn’t harm infants.

Major finding: Induction reduced risk of C-section by 16% and risk of pregnancy-related hypertensive disorder by 36%, compared with expectant management.

Study details: The study randomized 6,106 women to elective induction or expectant management with delivery by 42 weeks.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health sponsored the study; Dr. Grobman had no financial disclosures.

Source: Grobman W. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jan;218:S601.

2018 Update on fertility

Clinicians always should consider endometriosis in the diagnostic work-up of an infertility patient. But the diagnosis of endometriosis is often difficult, and management is complex. In this Update, we summarize international consensus documents on endometriosis with the aim of enhancing clinicians’ ability to make evidence-based decisions. In addition, we explore the interesting results of a large hysterosalpingography trial in which 2 different contrast mediums were used. Finally, we urge all clinicians to adapt the new standardized lexicon of infertility and fertility care terms that comprise the recently revised international glossary.

Endometriosis and infertility: The knowns and unknowns

Johnson NP, Hummelshoj L, Adamson GD, et al; World Endometriosis Society Sao Paulo Consortium. World Endometriosis Society consensus on the classification of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(2):315-324.

Johnson NP, Hummelshoj L; World Endometriosis Society Montpellier Consortium. Consensus on current management of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(6):1552-1568.

Rogers PA, Adamson GD, Al-Jefout M, et al; WES/WERF Consortium for Research Priorities in Endometriosis. Research priorities for endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2017;24(2):202-226.

Endometriosis is defined as "a disease characterized by the presence of endometrium-like epithelium and stroma outside the endometrium and myometrium. Intrapelvic endometriosis can be located superficially on the peritoneum (peritoneal endometriosis), can extend 5 mm or more beneath the peritoneum (deep endometriosis) or can be present as an ovarian endometriotic cyst (endometrioma)."1 Always consider endometriosis in the infertile patient.

Although many professional societies and numerous Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews have provided guidelines on endometriosis, controversy and uncertainty remain. The World Endometriosis Society (WES) and the World Endometriosis Research Foundation (WERF), however, have now published several consensus documents that assess the global literature and professional organization guidelines in a structured, consensus-driven process.2-4 These WES and WERF documents consolidate known information and can be used to inform the clinician in making evidence-linked diagnostic and treatment decisions. Recommendations offered in this discussion are based on those documents.

Establishing the diagnosis can be difficult

Diagnosis of endometriosis is often difficult and is delayed an average of 7 years from onset of symptoms. These include severe dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain, ovulation pain, cyclical or perimenstrual symptoms (bowel or bladder associated) with or without abnormal bleeding, chronic fatigue, and infertility. A major difficulty is that the predictive value of any one symptom or set of symptoms remains uncertain, as each of these symptoms can have other causes, and a significant proportion of affected women are asymptomatic.

For a definitive diagnosis of endometriosis, visual inspection of the pelvis at laparoscopy is the gold standard investigation, unless disease is visible in the vagina or elsewhere. Positive histology confirms the diagnosis of endometriosis; negative histology does not exclude it. Whether histology should be obtained if peritoneal disease alone is present is controversial: visual inspection usually is adequate, but histologic confirmation of at least one lesion is ideal. In cases of ovarian endometrioma (>4 cm in diameter) and in deeply infiltrating disease, histology should be obtained to identify endometriosis and to exclude rare instances of malignancy.

Compared with laparoscopy, transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) has no value in diagnosing peritoneal endometriosis, but it is a useful tool for both making and excluding the diagnosis of an ovarian endometrioma. TVUS may have a role in the diagnosis of disease involving the bladder or rectum.

At present, evidence is insufficient to indicate that magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is useful for diagnosing or excluding endometriosis compared with laparoscopy. MRI should be reserved for when ultrasound results are equivocal in cases of rectovaginal or bladder endometriosis.

Serum cancer antigen 125 (CA 125) levels may be elevated in endometriosis. However, measuring serum CA 125 levels has no value as a diagnostic tool.

No fertility benefit with ovarian suppression

More than 2 dozen randomized controlled trials (RCTs) provide strong evidence that there is no fertility benefit from ovarian suppression. The drug costs and delayed time to pregnancy mean that ovarian suppression with oral contraceptives, other progestational agents, or gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists before fertility treatment is not indicated, with the possible exception of using it prior to in vitro fertilization (IVF).

Ovarian suppression also has been suggested as beneficial in conjunction with surgery. However, at least 16 RCTs have failed to show fertility improvement when ovarian suppression is given either preoperatively or postoperatively. Again, the delay in attempting pregnancy, drug costs, and adverse effects render ovarian suppression not appropriate.

While ovarian suppression has not been shown to increase pregnancy rates, ovarian stimulation (OS) likely does, especially when combined with intrauterine insemination (IUI).5

Laparoscopy: Appropriate for selected patients

A major decision for clinicians and patients dealing with infertility is whether to perform a laparoscopy, both for diagnostic and for treatment reasons. Currently, data are insufficient to recommend laparoscopic surgery prior to OS/IUI unless there is a history of evidence of anatomic disease and/or the patient has sufficient pain to justify the physical, emotional, financial, and time costs of laparoscopy. Laparoscopy therefore can be considered as possibly appropriate in younger women (<37 years of age) with short duration of infertility (<4 years), normal male factor, normal or treatable uterus, normal or treatable ovulation disorder, and limited prior treatment.

It is important to consider what disease might be found and how much of an increase in fertility can be obtained by treatment, so that the number needed to treat (NNT) can be used as an estimate of the potential value of laparoscopy in a given patient. A patient also should have no contraindications to laparoscopy and accept 9 to 15 months of attempting pregnancy before undergoing IVF treatment.

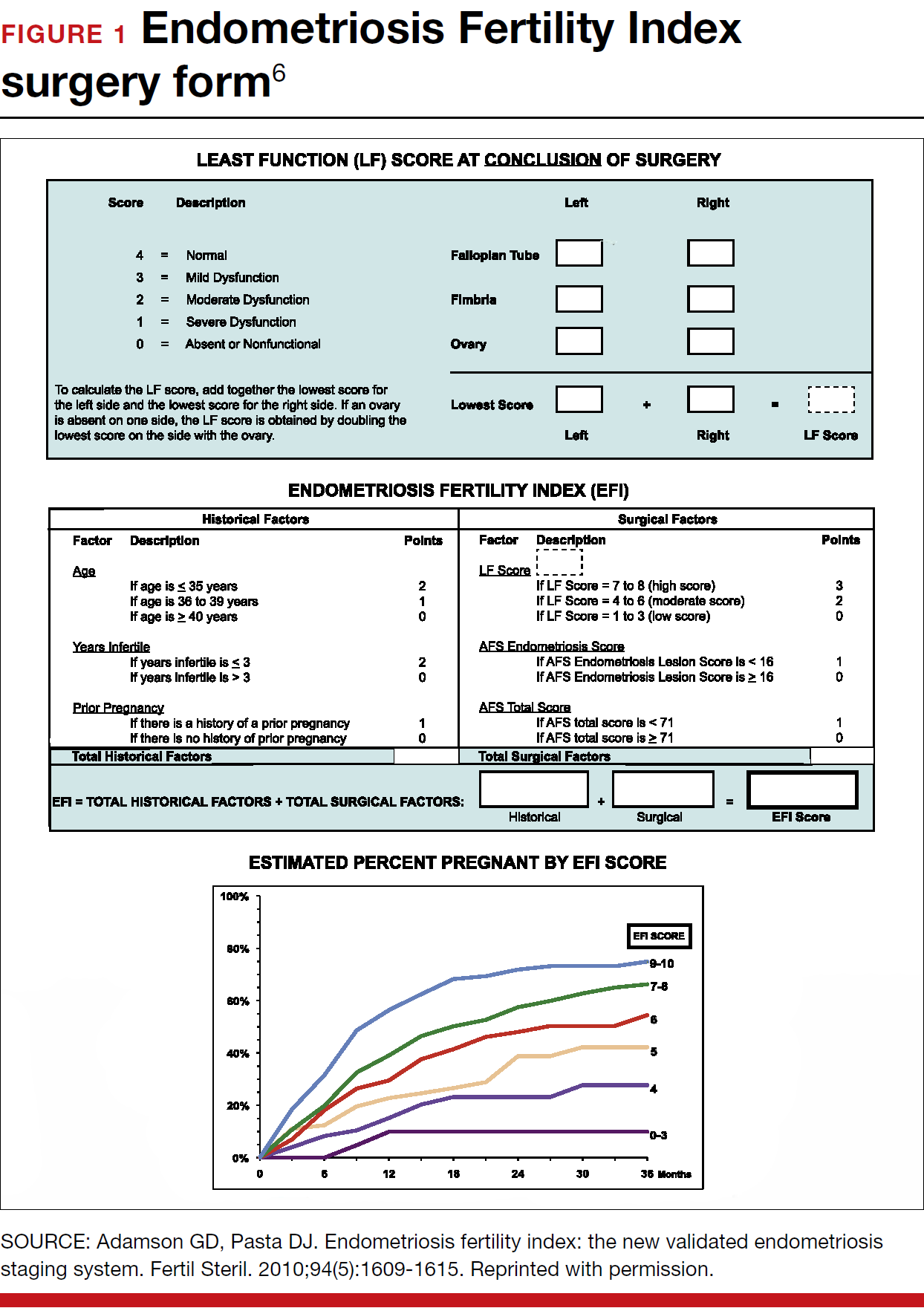

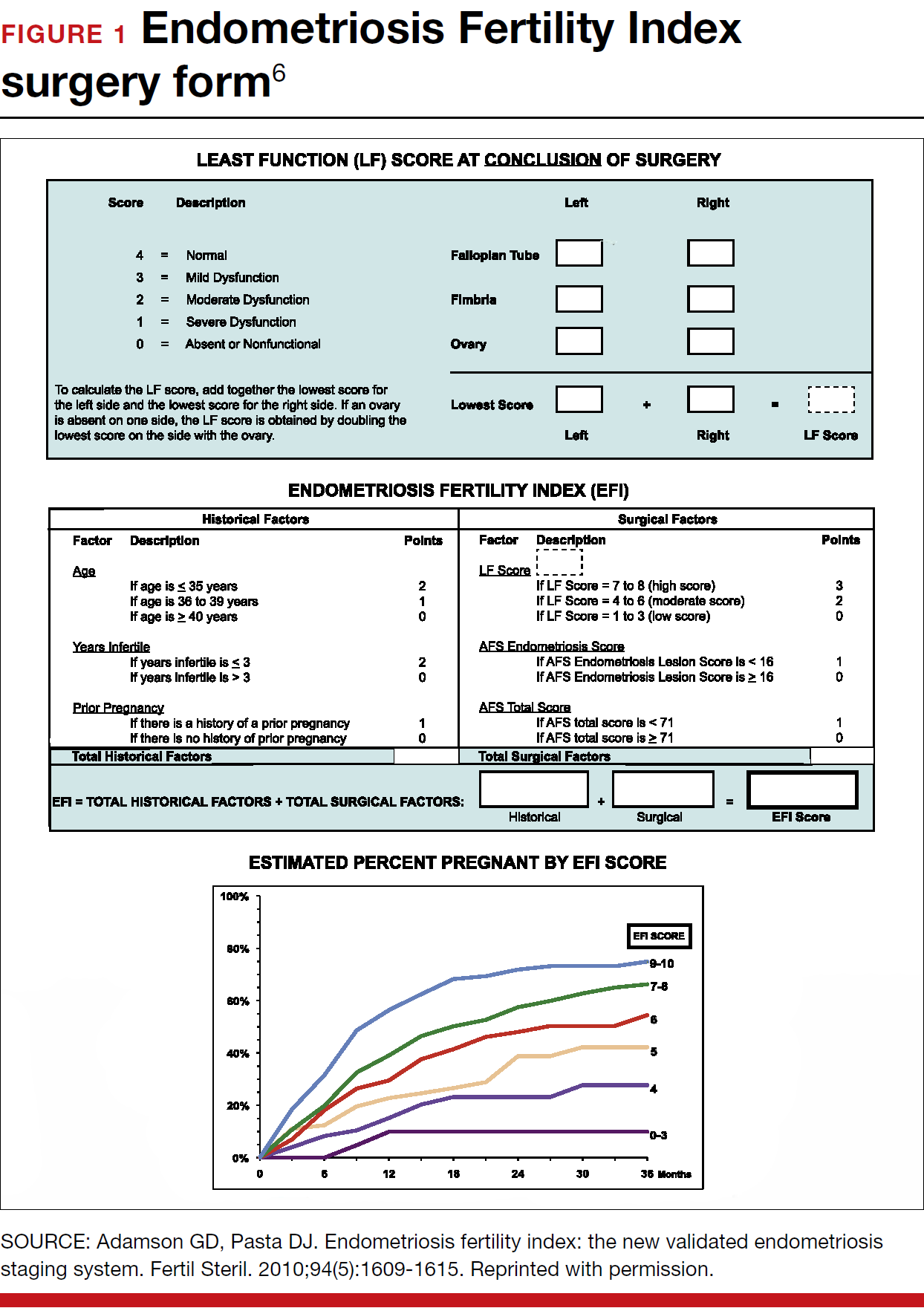

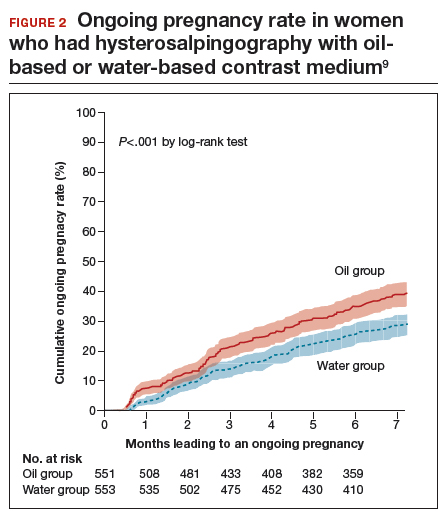

When laparoscopy is performed for minimal to mild disease, the odds ratio for pregnancy is 1.66 with treatment. It is important to remove all visible disease without injuring healthy tissue. When disease is moderate to severe, there is often severe anatomic distortion and a very low background pregnancy rate. Numerous uncontrolled trials show benefit of operative laparoscopy, especially for invasive, adhesive, and cystic endometriosis. However, repeat surgery is rarely indicated. After surgery, the Endometriosis Fertility Index (EFI) can be used to determine prognosis and plan management (FIGURE 1).6 An easy-to-use electronic EFI calculator is available online at www.endometriosisefi.com.

Management of endometriomas

Endometriomas are often operated on because of pain. Initial pain relief occurs in 60% to 100% of patients, but cysts recur following stripping about 10% of the time, and drainage without stripping, about 20%. With recurrence, pain is present about 75% of the time.

Pregnancy rates following endometrioma treatment depend on patient age and the status of the pelvis following operative intervention. This can be determined from the EFI. Often, the dilemma with endometriomas is how aggressive to be in removing them. The principles involved are to remove all the cyst wall if possible, but absolutely to minimize ovarian tissue damage, because reduced ovarian reserve is a possible major negative consequence of ovarian surgery.

Recommendations

While endometriosis is often a cause of infertility, often infertile patients do not have endometriosis. A careful history, physical examination, and ultrasonography, and possibly other imaging studies, are prerequisites to careful clinical judgment in diagnosing and treating infertile patients who might or do have endometriosis.

When pelvic pain is present, initially nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), oral contraceptives (OCs), progestational agents, or an intrauterine device can be helpful. These ovarian suppression medications do not increase fertility, however, and should be stopped in any patient who desires to get pregnant.

When pelvic and male fertility factors appear reasonably normal (even if minimal or mild endometriosis is suspected), treatment with clomiphene 100 mg on cycle days 3 through 7 and IUI for 3 to 6 cycles is an effective first step. However, if the patient has persistent pain and/or infertility without other significant infertility factors, then diagnostic laparoscopy with intraoperative treatment of disease is indicated.

Surgery well performed is effective treatment for all stages of endometriosis and endometriomas, both for infertility and for pain. Repeat surgery, however, is rarely indicated because of limited results, so it is important to obtain the best possible result on the first surgery. Surgery is indicated for large endometriomas (>4 cm). Endometriosis has almost no effect on the IVF live birth rate unless ovarian reserve has been reduced by endometriomas or surgery, so endometriosis surgery should be performed by skilled and experienced surgeons.

Endometriosis is a complex disease that can cause infertility. Its diagnosis and management are frequently difficult, requiring knowledge, experience, and good medical judgment and surgical skills. However, if evidence-linked principles are followed, effective treatment plans and good outcomes can be obtained for most patients.

Read about why oil-based contrast may be better than water-based contrast with HSG.

Oil-based contrast medium use in hysterosalpingography is associated with higher pregnancy rates compared with water-based contrast

Dreyer K, van Rijswijk J, Mijatovic V, et al. Oil-based or water-based contrast for hysterosalpingography in infertile women. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(21):2043-2052.

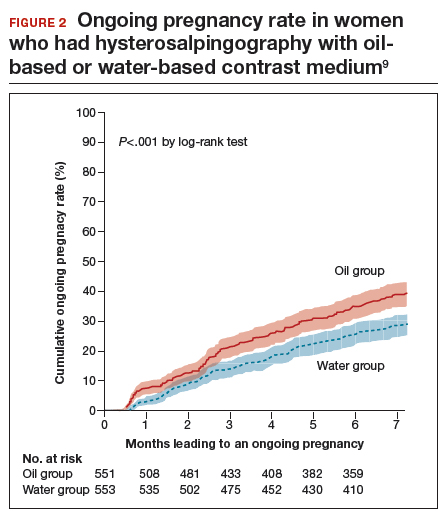

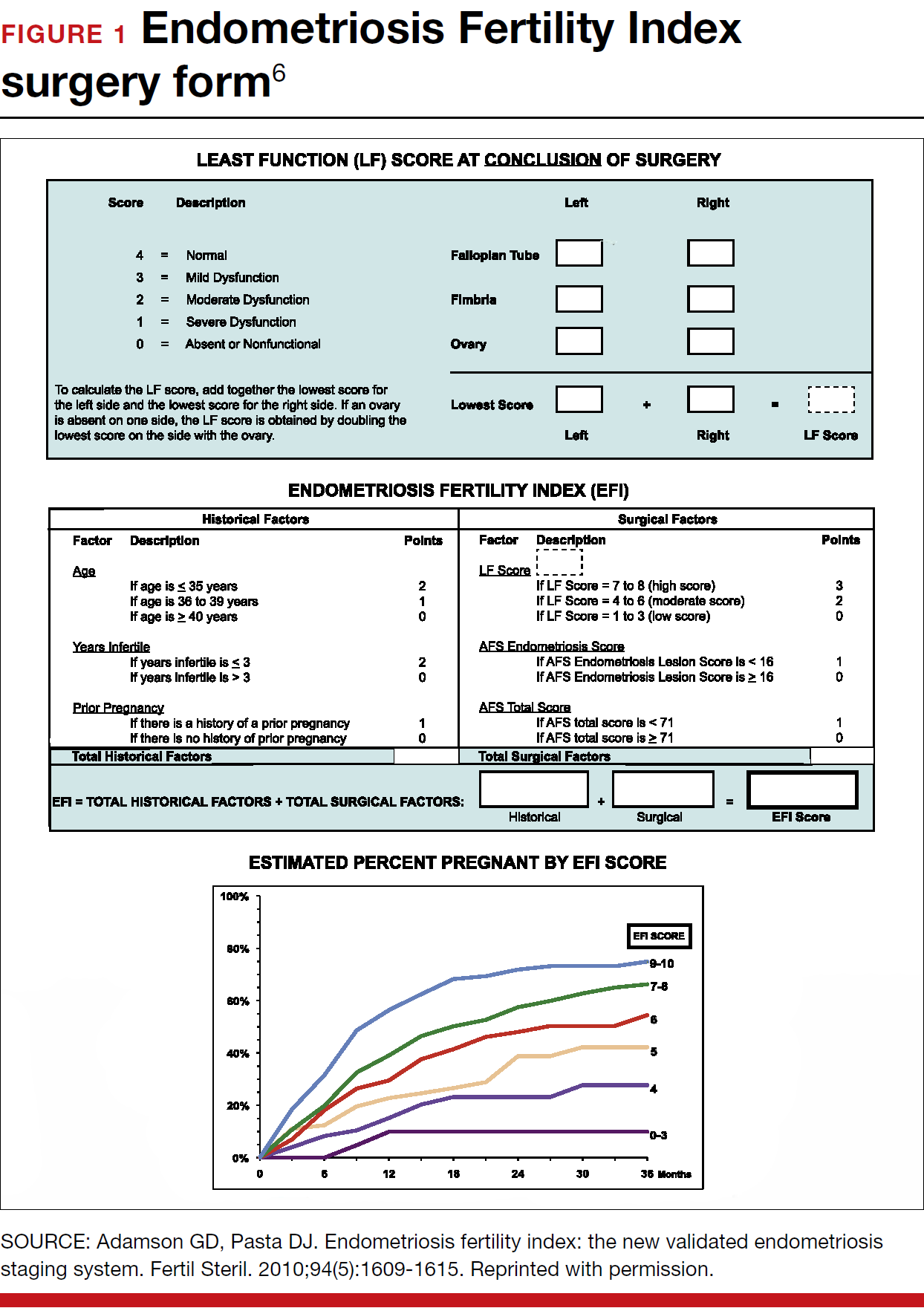

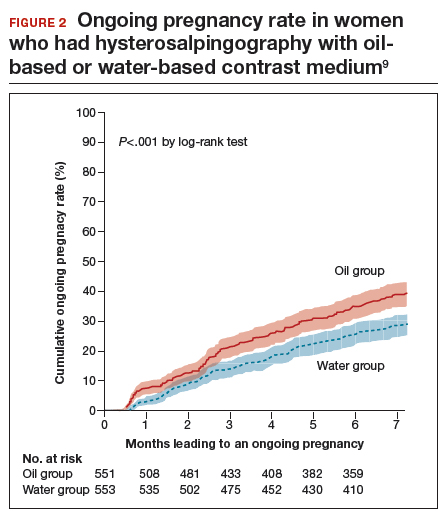

Hysterosalpingography (HSG) to assess tubal patency has been a mainstay of infertility diagnosis for decades. Some, but not all, studies also have suggested that pregnancy rates are higher after this tubal flushing procedure, especially if performed with oil contrast.7,8 A recent multicenter, randomized, controlled trial by Dreyer and colleagues that compared ongoing pregnancy rates and other outcomes among women who had HSG with oil contrast versus with water contrast provides additional valuable information.9

Trial details

In this study, 1,294 infertile women in 27 academic, teaching and nonteaching hospitals were screened for trial eligibility; 1,119 women provided written informed consent. Of these, 557 women were randomly assigned to HSG with oil contrast and 562 to water contrast. The women had spontaneous menstrual cycles, had been attempting pregnancy for at least 1 year, and had indications for HSG.

Exclusion criteria were known endocrine disorders, fewer than 8 menstrual cycles per year, a high risk of tubal disease, iodine allergy, and a total motile sperm count after sperm wash of less than 3 million/mL in the male partner (or a total motile sperm count of less than 1 million/mL when an analysis after sperm wash was not performed).

Just prior to undergoing HSG, the women were randomly assigned to receive either oil contrast or water contrast medium. (The trial was not blinded to participants or caregivers.) HSG was performed according to local protocols using cervical vacuum cup, metal cannula (hysterophore), or balloon catheter and approximately 5 to 10 mL of contrast medium.

After HSG, couples received expectant management when the predicted likelihood of pregnancy within 12 months, based on the prognostic model of Hunault, was 30% or greater.10 IUI was offered for pregnancy likelihood less than 30%, mild male infertility, or failure after a period of expectant management. IUI with or without mild ovarian stimulation (2-3 follicles) with clomiphene or gonadotropins was initiated after a minimum of 2 months of expectant management after HSG.

The primary outcome measure was ongoing pregnancy, defined as a positive fetal heartbeat on ultrasonographic examination after 12 weeks of gestation, with the first day of the last menstrual cycle for the pregnancy within 6 months after randomization. Secondary outcome measures were clinical pregnancy, live birth, miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, time to pregnancy, and pain scores after HSG. All data were analyzed according to intention-to-treat.

Pregnancy rates increased with oil-contrast HSG

The baseline characteristics of the 2 groups were similar. HSG showed bilateral tubal patency in 477 of 554 women (86.1%) in the oil contrast group and in 491 of 554 women (88.6%) who received the water contrast (rate ratio, 0.97; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.93-1.02). Bilateral tubal occlusion occurred in 9 women in the oil group (1.6%) and in 13 in the water group (2.3%) (relative risk, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.30-1.61).

A total of 58.3% of the women assigned to oil contrast and 57.2% of those assigned to water contrast received expectant management. Similar percentages of women in the oil group and in the water group underwent IUI (39.7% and 41.0%, respectively), IVF or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) (2.3% and 2.2%), laparoscopy (6.2% in each group), and hysteroscopy (4.4% and 4.2%).

Ongoing pregnancy occurred in 220 of 554 women (39.7%) in the oil contrast group and in 161 of 554 women (29.1%) in the water contrast group (rate ratio, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.16-1.61; P<.001). The median time to the onset of pregnancy in the oil group was 2.7 months (interquartile range, 1.5-4.7) (FIGURE 2), while in the water group it was 3.1 months (interquartile range, 1.6-4.8) (P = .44).

While the proportion of women getting pregnant with or without the different interventions was similar in both groups, the live birth rate was 38.8% in the oil group versus 28.1% in the water group (rate ratio, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.17-1.64; P<.001). Three of 554 women (0.5%) assigned to oil contrast and 4 of 554 women (0.7%) in the water contrast group had an adverse event during the trial period. Three women (1.4%), all in the oil group, delivered a child with a congenital anomaly.

Why this study is important

This is the largest and best methodologic study on this clinical issue. It showed higher pregnancy and live birth rates within 6 months of HSG performed with oil compared with water. Although the study was not blinded, the group similarities and objective outcomes support minimal bias. Importantly, these results can be generalized only to women with similar inclusion characteristics.

It is unclear why oil HSG might enhance fertility. Suggested mechanisms include flushing of debris and/or mucous plugs or an effect on peritoneal macrophages or endometrial receptivity. Since HSG is minimally invasive and inexpensive, and the 10% increase in pregnancy rates corresponds to an NNT of 10, it is reasonable to consider, although formal cost-effectiveness data are lacking.

Concerns include the rare theoretical risk of intravasation with subsequent allergic reaction or fat embolism. Three infants in the oil group and none in the water group had congenital anomalies. This is likely due to chance, since this rate is not higher than that in the general population and no other data suggest an increased risk. Comparison of these results with other new techniques, such as sonohysterography (saline infusion sonogram), awaits further studies.

Recommendation

HSG with oil contrast should be considered a potential therapeutic as well as diagnostic intervention in selected patients.

HSG is an important diagnostic test for most infertility patients. The fact that a therapeutic benefit probably also is associated with oil-based HSG increases the clinical indications for this test.

Read about new definitions of infertility terminology you should know.

Infertility glossary is newly updated

Zegers-Hochchild F, Adamson GD, Dyer S, et al. The International Glossary on Infertility and Fertility Care, 2017. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(3):393-406.

Terms and definitions used in infertility and fertility care frequently have had different meanings for different stakeholders, especially on a global basis. This can result in misunderstandings and inappropriate interpretation and comparison of published information and research. To help address these issues, international fertility organizations recently developed an updated glossary on infertilityterminology.

The consensus process for updating the glossary

The International Glossary on Infertility and Fertility Care, 2017, was recently published simultaneously in Fertility and Sterility and Human Reproduction. This is the second revision; the first glossary was published in 2006 and revised in 2009. This revision's 25 lead experts began work in 2014. Their teams of professionals interacted by electronic mail, at international and regional society meetings, and at 2 consultations held in Geneva, Switzerland. This glossary represents consensus agreement reached on 283 evidence-driven terms and definitions.

The work was led by the International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technologies in partnership with the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology, International Federation of Fertility Societies, March of Dimes, African Fertility Society, Groupe Inter-africain d'Etude de Recherche et d'Application sur la Fertilité, Asian Pacific Initiative on Reproduction, Middle East Fertility Society, Red Latinoamericana de Reproducción Asistida, and the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

All together, 108 international professional experts (clinicians, basic scientists, epidemiologists, and social scientists), along with national and regional representatives of infertile persons, participated in the development of this evidence-base driven glossary. As such, these definitions now set the standard for international communication among clinicians, scientists, and policymakers.

Definition of infertility is broadened

The definitions take account of ethics, human rights, cultural sensitivities, ethnic minorities, and gender equality. For example, the first modification included broadening the concept of infertility to be an "impairment of individuals" in their capacity to reproduce, irrespective of whether the individual has a partner. (See “Broadened definition of infertility” below). Reproductive rights are individual human rights and do not depend on a relationship with another individual. The revised definition also reinforces the concept of infertility as a disease that can generate an impairment of function.

Infertility: A disease characterized by the failure to establish a clinical pregnancy after 12 months of regular, unprotected sexual intercourse or due to an impairment of a person’s capacity to reproduce either as an individual or with his/her partner. Fertility interventions may be initiated in less than 1 year based on medical, sexual and reproductive history, age, physical findings and diagnostic testing. Infertility is a disease, which generates disability as an impairment of function.

Reference

- Zegers-Hochchild F, Adamson GD, Dyer S, et al. The International Glossary on Infertility and Fertility Care, 2017. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(3):393–406

New--and changed--definitions

Certain terms need to be consistent with those used currently internationally, for example, at which gestational age a miscarriage/abortion becomes a stillbirth.

Some terms are confusing, such as subfertility, which does not define a different or less severe fertility status than infertility, does not exist before infertility is diagnosed, and should not be confused with sterility, which is a permanent state of infertility. The term subfertility therefore is redundant and has been removed and replaced by infertility (See “Some terms with an important new definition” below).

- Clinical pregnancy

- Conception (removed from glossary)

- Diminished ovarian reserve

- Fertility care

- Hypospermia (replaces oligospermia)

- Ovarian reserve

- Pregnancy

- Preimplantation genetic testing

- Spontaneous abortion/miscarriage

- Subfertility (should be used interchangeably with infertility)

Reference

- Zegers-Hochchild F, Adamson GD, Dyer S, et al. The International Glossary on Infertility and Fertility Care, 2017. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(3):393–406.

In a different context, the term conception, and its derivatives such as conceiving or conceived, was removed because it cannot be described biologically during the process of reproduction. Instead, terms such as fertilization, implantation, pregnancy, and live birth should be used.

Important male terms also changed: oligospermia is a term for low semen volume that is now replaced by hypospermia to avoid confusion with oligozoospermia, which is low concentration of spermatozoa in the ejaculate below the lower reference limit. When reporting results, the reference criteria should be specified.

Lastly, owing to the lack of standardization in determining the burden of infertility, and to better ensure comparability of prevalence data published globally, this glossary includes definitions for terms frequently used in epidemiology and public health. Examples include voluntary and involuntary childlessness, primary and secondary infertility, fertility care, fecundity, and fecundability, among others.

Getting the word out

The glossary has been approved by all of the participating organizations who are assisting in its distribution. It is being presented at national and international meetings and is used in The FIGO Fertility Toolbox (www.fertilitytool.com). It is hoped that all professionals and other stakeholders will begin to use its terminology globally to provide quality care and ensure consistency in registering specific fertility care interventions and more accurate reporting of their outcomes.

The language we use determines our individual and collective understanding of the scientific and clinical care of our patients. This glossary provides an essential and comprehensive standardization of terms and definitions essential to quality reproductive health care.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Zegers-Hochchild F, Adamson GD, Dyer S, et al. The International Glossary on Infertility and Fertility Care, 2017. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(3):393–406.

- Johnson NP, Hummelshoj L; World Endometriosis Society Montpellier Consortium. Consensus on current management of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(6):1552–1568.

- Rogers PA, Adamson GD, Al-Jefout M, et al; WES/WERF Consortium for Research Priorities in Endometriosis. Research priorities for endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2017;24(2):202–226.

- Johnson NP, Hummelshoj L, Adamson GD, et al; World Endometriosis Society Sao Paulo Consortium. World Endometriosis Society consensus on the classification of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(2):315–324.

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Endometriosis and infertility: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(3):591–598.

- Adamson GD, Pasta DJ. Endometriosis fertility index: the new, validated endometriosis staging system. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(5):1609–1615.

- Weir WC, Weir DR. Therapeutic value of salpingograms in infertility. Fertil Steril. 1951;2(6);514–522.

- Johnson NP, Farquhar CM, Hadden WE, Suckling J, Yu Y, Sadler L. The FLUSH trial—flushing with lipiodol for unexplained (and endometriosis-related) subfertility by hysterosalpingography: a randomized trial. Hum Reprod. 2004;19(9):2043–2051.

- Dreyer K, van Rijswijk J, Mijatovic V, et al. Oil-based or water-based contrast for hysterosalpingography in infertile women. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(21):2043–2052.

- Van der Steeg JW, Steures P, Eijkemans MJ, et al; Collaborative Effort for Clinical Evaluation in Reproductive Medicine. Pregnancy is predictable: a large-scale prospective external validation of the prediction of spontaneous pregnancy in sub-fertile couples. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(2):536–542.

Clinicians always should consider endometriosis in the diagnostic work-up of an infertility patient. But the diagnosis of endometriosis is often difficult, and management is complex. In this Update, we summarize international consensus documents on endometriosis with the aim of enhancing clinicians’ ability to make evidence-based decisions. In addition, we explore the interesting results of a large hysterosalpingography trial in which 2 different contrast mediums were used. Finally, we urge all clinicians to adapt the new standardized lexicon of infertility and fertility care terms that comprise the recently revised international glossary.

Endometriosis and infertility: The knowns and unknowns

Johnson NP, Hummelshoj L, Adamson GD, et al; World Endometriosis Society Sao Paulo Consortium. World Endometriosis Society consensus on the classification of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(2):315-324.

Johnson NP, Hummelshoj L; World Endometriosis Society Montpellier Consortium. Consensus on current management of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(6):1552-1568.

Rogers PA, Adamson GD, Al-Jefout M, et al; WES/WERF Consortium for Research Priorities in Endometriosis. Research priorities for endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2017;24(2):202-226.

Endometriosis is defined as "a disease characterized by the presence of endometrium-like epithelium and stroma outside the endometrium and myometrium. Intrapelvic endometriosis can be located superficially on the peritoneum (peritoneal endometriosis), can extend 5 mm or more beneath the peritoneum (deep endometriosis) or can be present as an ovarian endometriotic cyst (endometrioma)."1 Always consider endometriosis in the infertile patient.

Although many professional societies and numerous Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews have provided guidelines on endometriosis, controversy and uncertainty remain. The World Endometriosis Society (WES) and the World Endometriosis Research Foundation (WERF), however, have now published several consensus documents that assess the global literature and professional organization guidelines in a structured, consensus-driven process.2-4 These WES and WERF documents consolidate known information and can be used to inform the clinician in making evidence-linked diagnostic and treatment decisions. Recommendations offered in this discussion are based on those documents.

Establishing the diagnosis can be difficult

Diagnosis of endometriosis is often difficult and is delayed an average of 7 years from onset of symptoms. These include severe dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain, ovulation pain, cyclical or perimenstrual symptoms (bowel or bladder associated) with or without abnormal bleeding, chronic fatigue, and infertility. A major difficulty is that the predictive value of any one symptom or set of symptoms remains uncertain, as each of these symptoms can have other causes, and a significant proportion of affected women are asymptomatic.

For a definitive diagnosis of endometriosis, visual inspection of the pelvis at laparoscopy is the gold standard investigation, unless disease is visible in the vagina or elsewhere. Positive histology confirms the diagnosis of endometriosis; negative histology does not exclude it. Whether histology should be obtained if peritoneal disease alone is present is controversial: visual inspection usually is adequate, but histologic confirmation of at least one lesion is ideal. In cases of ovarian endometrioma (>4 cm in diameter) and in deeply infiltrating disease, histology should be obtained to identify endometriosis and to exclude rare instances of malignancy.

Compared with laparoscopy, transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) has no value in diagnosing peritoneal endometriosis, but it is a useful tool for both making and excluding the diagnosis of an ovarian endometrioma. TVUS may have a role in the diagnosis of disease involving the bladder or rectum.

At present, evidence is insufficient to indicate that magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is useful for diagnosing or excluding endometriosis compared with laparoscopy. MRI should be reserved for when ultrasound results are equivocal in cases of rectovaginal or bladder endometriosis.

Serum cancer antigen 125 (CA 125) levels may be elevated in endometriosis. However, measuring serum CA 125 levels has no value as a diagnostic tool.

No fertility benefit with ovarian suppression

More than 2 dozen randomized controlled trials (RCTs) provide strong evidence that there is no fertility benefit from ovarian suppression. The drug costs and delayed time to pregnancy mean that ovarian suppression with oral contraceptives, other progestational agents, or gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists before fertility treatment is not indicated, with the possible exception of using it prior to in vitro fertilization (IVF).