User login

Immediate Treatment Best for DVT, Specialist Says

HOLLYWOOD, FLA. — The time to take care of deep vein thrombosis is when it happens, even if it's during pregnancy, Dr. Anthony J. Comerota said.

Women who develop DVT during pregnancy can be safely and effectively treated with thrombolysis while pregnant, thereby avoiding both the acute danger of pulmonary embolism and the risk of long-term complications of postthrombotic syndrome that can make their legs painful and swollen and can eventually disrupt their lives.

“Most physicians shy away from aggressive treatments during pregnancy and avoid using thrombolytic drugs that could increase the risk of bleeding,” Dr. Comerota said at ISET 2008, an international symposium on endovascular therapy.

“These are valid concerns, but it can leave women with an extensive clot burden that interventionalists would ordinarily treat. … If [DVT] progresses to chronic venous disease, it will completely change the patient's life,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Comerota reported his experience using catheter-delivered thrombolytic drugs, with or without additional procedures, to safely treat seven pregnant women with DVT. None of the women had a bleeding complication.

Five women subsequently gave birth to healthy infants by routine vaginal delivery, and one infant was delivered by a cesarean section. The seventh woman lost her fetus during the second trimester because of a very aggressive case of the prothrombotic condition known as antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, which boosted her risk for developing DVT during pregnancy, said Dr. Comerota, director of a vascular treatment and research center in Toledo, Ohio.

Pregnant women are four- to sixfold more likely to develop DVT than are nonpregnant women, and if the DVT persists they are also more likely to have a poor pregnancy outcome. DVT during pregnancy is more likely to occur in ilial veins and to be extensive and cause more sequelae. In nonpregnant women, DVT is usually less extensive and tends to form in the femoral-popliteal veins.

About two-thirds of women who develop DVT during pregnancy go on to have chronic venous insufficiency if their initial treatment during pregnancy is by anticoagulation alone.

Although many physicians are reluctant to use thrombolytic therapy during pregnancy, there is no indication of an elevated risk for major hemorrhage from lytic therapy in pregnant women, Dr. Comerota said. It is known that the placental penetration rates of urokinase (pregnancy category B), streptokinase (category C), and recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (category C) are too low to have any fibrinolytic effect in the fetus.

“Thrombolytic therapy appears to be low risk and compatible with pregnancy, but the human pregnancy experience is limited. No cases of fetal hemorrhage or loss secondary to thrombolytics have been reported,” said Gerald Briggs, a clinical pharmacist specializing in obstetrics at Long Beach (Calif.) Memorial Medical Center. He agreed that recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (rt-PA), urokinase, and streptokinase are not believed to cross to an embryo or fetus in amounts sufficient to cause hemorrhage.

Of the seven women treated by Dr. Comerota, one received intracatheter urokinase and six were treated with rt-PA. Five women were treated with endovascular devices only. In some cases, the endovascular treatments included Bacchus Vascular Inc.'s Trellis catheter (which uses a pair of balloons to isolate an artery segment, followed by the infusion of a lytic drug, agitation of the drug within the clot, and aspiration of the clot fragments and drug), EKOS Corp.'s EndoWave catheter (which combines lytic infusion with ultrasound), Possis Medical Inc.'s AngioJet system (a clot removal device), and stenting. One patient was treated with both endovascular devices and open surgery, and the seventh patient underwent open surgery only.

Five women were treated only during the antepartum period, and two women were treated both antepartum and postpartum. Five of the women were in the third trimester during their treatment. Two women were in the second trimester, and shielding was used to protect the uterus and fetus during radiologic procedures.

Five women did not have any postthrombotic symptoms. Two patients had mild leg swelling following pregnancy. After pregnancy, all women were placed on chronic warfarin therapy.

Three women later became pregnant again, and during pregnancy they were placed on prophylactic treatment with a low-molecular-weight heparin. None of these three women developed DVT during their subsequent pregnancies, Dr. Comerota said.

Dr. Comerota is a consultant to, on the speakers bureau for, and has received research grants from, Sanofi Aventis, and is also a consultant to and has received research grants from Bacchus Vascular.

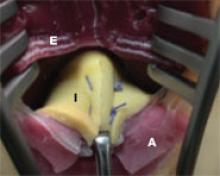

Surgery exposed a large thrombus embedded in a pregnant patient's iliofemoral vein. Photos courtesy Dr. Anthony J. Comerota

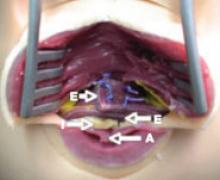

The size of the thrombus was better appreciated once it was removed and displayed by itself.

HOLLYWOOD, FLA. — The time to take care of deep vein thrombosis is when it happens, even if it's during pregnancy, Dr. Anthony J. Comerota said.

Women who develop DVT during pregnancy can be safely and effectively treated with thrombolysis while pregnant, thereby avoiding both the acute danger of pulmonary embolism and the risk of long-term complications of postthrombotic syndrome that can make their legs painful and swollen and can eventually disrupt their lives.

“Most physicians shy away from aggressive treatments during pregnancy and avoid using thrombolytic drugs that could increase the risk of bleeding,” Dr. Comerota said at ISET 2008, an international symposium on endovascular therapy.

“These are valid concerns, but it can leave women with an extensive clot burden that interventionalists would ordinarily treat. … If [DVT] progresses to chronic venous disease, it will completely change the patient's life,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Comerota reported his experience using catheter-delivered thrombolytic drugs, with or without additional procedures, to safely treat seven pregnant women with DVT. None of the women had a bleeding complication.

Five women subsequently gave birth to healthy infants by routine vaginal delivery, and one infant was delivered by a cesarean section. The seventh woman lost her fetus during the second trimester because of a very aggressive case of the prothrombotic condition known as antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, which boosted her risk for developing DVT during pregnancy, said Dr. Comerota, director of a vascular treatment and research center in Toledo, Ohio.

Pregnant women are four- to sixfold more likely to develop DVT than are nonpregnant women, and if the DVT persists they are also more likely to have a poor pregnancy outcome. DVT during pregnancy is more likely to occur in ilial veins and to be extensive and cause more sequelae. In nonpregnant women, DVT is usually less extensive and tends to form in the femoral-popliteal veins.

About two-thirds of women who develop DVT during pregnancy go on to have chronic venous insufficiency if their initial treatment during pregnancy is by anticoagulation alone.

Although many physicians are reluctant to use thrombolytic therapy during pregnancy, there is no indication of an elevated risk for major hemorrhage from lytic therapy in pregnant women, Dr. Comerota said. It is known that the placental penetration rates of urokinase (pregnancy category B), streptokinase (category C), and recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (category C) are too low to have any fibrinolytic effect in the fetus.

“Thrombolytic therapy appears to be low risk and compatible with pregnancy, but the human pregnancy experience is limited. No cases of fetal hemorrhage or loss secondary to thrombolytics have been reported,” said Gerald Briggs, a clinical pharmacist specializing in obstetrics at Long Beach (Calif.) Memorial Medical Center. He agreed that recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (rt-PA), urokinase, and streptokinase are not believed to cross to an embryo or fetus in amounts sufficient to cause hemorrhage.

Of the seven women treated by Dr. Comerota, one received intracatheter urokinase and six were treated with rt-PA. Five women were treated with endovascular devices only. In some cases, the endovascular treatments included Bacchus Vascular Inc.'s Trellis catheter (which uses a pair of balloons to isolate an artery segment, followed by the infusion of a lytic drug, agitation of the drug within the clot, and aspiration of the clot fragments and drug), EKOS Corp.'s EndoWave catheter (which combines lytic infusion with ultrasound), Possis Medical Inc.'s AngioJet system (a clot removal device), and stenting. One patient was treated with both endovascular devices and open surgery, and the seventh patient underwent open surgery only.

Five women were treated only during the antepartum period, and two women were treated both antepartum and postpartum. Five of the women were in the third trimester during their treatment. Two women were in the second trimester, and shielding was used to protect the uterus and fetus during radiologic procedures.

Five women did not have any postthrombotic symptoms. Two patients had mild leg swelling following pregnancy. After pregnancy, all women were placed on chronic warfarin therapy.

Three women later became pregnant again, and during pregnancy they were placed on prophylactic treatment with a low-molecular-weight heparin. None of these three women developed DVT during their subsequent pregnancies, Dr. Comerota said.

Dr. Comerota is a consultant to, on the speakers bureau for, and has received research grants from, Sanofi Aventis, and is also a consultant to and has received research grants from Bacchus Vascular.

Surgery exposed a large thrombus embedded in a pregnant patient's iliofemoral vein. Photos courtesy Dr. Anthony J. Comerota

The size of the thrombus was better appreciated once it was removed and displayed by itself.

HOLLYWOOD, FLA. — The time to take care of deep vein thrombosis is when it happens, even if it's during pregnancy, Dr. Anthony J. Comerota said.

Women who develop DVT during pregnancy can be safely and effectively treated with thrombolysis while pregnant, thereby avoiding both the acute danger of pulmonary embolism and the risk of long-term complications of postthrombotic syndrome that can make their legs painful and swollen and can eventually disrupt their lives.

“Most physicians shy away from aggressive treatments during pregnancy and avoid using thrombolytic drugs that could increase the risk of bleeding,” Dr. Comerota said at ISET 2008, an international symposium on endovascular therapy.

“These are valid concerns, but it can leave women with an extensive clot burden that interventionalists would ordinarily treat. … If [DVT] progresses to chronic venous disease, it will completely change the patient's life,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Comerota reported his experience using catheter-delivered thrombolytic drugs, with or without additional procedures, to safely treat seven pregnant women with DVT. None of the women had a bleeding complication.

Five women subsequently gave birth to healthy infants by routine vaginal delivery, and one infant was delivered by a cesarean section. The seventh woman lost her fetus during the second trimester because of a very aggressive case of the prothrombotic condition known as antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, which boosted her risk for developing DVT during pregnancy, said Dr. Comerota, director of a vascular treatment and research center in Toledo, Ohio.

Pregnant women are four- to sixfold more likely to develop DVT than are nonpregnant women, and if the DVT persists they are also more likely to have a poor pregnancy outcome. DVT during pregnancy is more likely to occur in ilial veins and to be extensive and cause more sequelae. In nonpregnant women, DVT is usually less extensive and tends to form in the femoral-popliteal veins.

About two-thirds of women who develop DVT during pregnancy go on to have chronic venous insufficiency if their initial treatment during pregnancy is by anticoagulation alone.

Although many physicians are reluctant to use thrombolytic therapy during pregnancy, there is no indication of an elevated risk for major hemorrhage from lytic therapy in pregnant women, Dr. Comerota said. It is known that the placental penetration rates of urokinase (pregnancy category B), streptokinase (category C), and recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (category C) are too low to have any fibrinolytic effect in the fetus.

“Thrombolytic therapy appears to be low risk and compatible with pregnancy, but the human pregnancy experience is limited. No cases of fetal hemorrhage or loss secondary to thrombolytics have been reported,” said Gerald Briggs, a clinical pharmacist specializing in obstetrics at Long Beach (Calif.) Memorial Medical Center. He agreed that recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator (rt-PA), urokinase, and streptokinase are not believed to cross to an embryo or fetus in amounts sufficient to cause hemorrhage.

Of the seven women treated by Dr. Comerota, one received intracatheter urokinase and six were treated with rt-PA. Five women were treated with endovascular devices only. In some cases, the endovascular treatments included Bacchus Vascular Inc.'s Trellis catheter (which uses a pair of balloons to isolate an artery segment, followed by the infusion of a lytic drug, agitation of the drug within the clot, and aspiration of the clot fragments and drug), EKOS Corp.'s EndoWave catheter (which combines lytic infusion with ultrasound), Possis Medical Inc.'s AngioJet system (a clot removal device), and stenting. One patient was treated with both endovascular devices and open surgery, and the seventh patient underwent open surgery only.

Five women were treated only during the antepartum period, and two women were treated both antepartum and postpartum. Five of the women were in the third trimester during their treatment. Two women were in the second trimester, and shielding was used to protect the uterus and fetus during radiologic procedures.

Five women did not have any postthrombotic symptoms. Two patients had mild leg swelling following pregnancy. After pregnancy, all women were placed on chronic warfarin therapy.

Three women later became pregnant again, and during pregnancy they were placed on prophylactic treatment with a low-molecular-weight heparin. None of these three women developed DVT during their subsequent pregnancies, Dr. Comerota said.

Dr. Comerota is a consultant to, on the speakers bureau for, and has received research grants from, Sanofi Aventis, and is also a consultant to and has received research grants from Bacchus Vascular.

Surgery exposed a large thrombus embedded in a pregnant patient's iliofemoral vein. Photos courtesy Dr. Anthony J. Comerota

The size of the thrombus was better appreciated once it was removed and displayed by itself.

Postpartum Depression Tied to Prior Obesity

DALLAS — Obese women may be at increased risk for postpartum depression, new research suggests.

In a prospective analysis of 1,282 women who gave birth to singleton infants at term, nearly 30% of women with a prepregnancy body mass index of 30 or more screened positive for postpartum depression 8 weeks after delivery.

The study is the first to use a validated screening tool to evaluate the risk of postpartum depression (PPD) by maternal BMI strata, according to the researchers, who used a score of 12 or more on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Screen to define a positive PPD screen.

Women at the extremes of BMI and those with greater weight gains in pregnancy were also at increased risk for PPD, Dr. Yvette LaCoursiere and colleagues at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

A positive PPD screen was reported in 19% of underweight women (BMI below 18.5), 13% of normal-weight (BMI 18.5–24.9), 16% of overweight women (BMI 25–29.9), 18% with class I obesity (BMI 30–34.9), 28% with class II obesity (BMI 35–39.9), and 29% with class III obesity (BMI greater than or equal to 40). The number of women in each BMI stratum was: 115, 724, 256, 116, 43, and 31, respectively, with incomplete data available on 3 others.

BMI remained a risk factor for PPD even after the researchers controlled for maternal age (mean 27 years), race (86% white, 9% Hispanic), parity (two children), education (mean 14 years), and stressors including financial, traumatic, partner associated, and emotional.

“We're not screening women aggressively for postpartum depression, in general,” Dr. LaCoursiere said in an interview. “When I look at how this changed my practice, if I have women who are obese before delivery I have them come back at a 2-week visit and make sure they get a screening test because they have a very high chance of developing depression.”

Weight gain during pregnancy also influenced a woman's chance of becoming depressed. A positive PPD screen was observed for 10% of normal-weight women who gained 24 pounds or less, 11% of those who gained 25–34 pounds, and 16% of those who gained more than 35 pounds. The rates were similar among overweight women (12%, 14%, and 20%, respectively), but did not increase in a stepwise fashion among the mildly obese (23%, 9%, and 21%, respectively). There were too few women with class II and III obesity to analyze.

Contrary to what one would expect, normal-weight women are more likely than are obese women to exceed the recommended pregnancy weight gain of 25–35 pounds, with obese women typically gaining only about 16–24 pounds during pregnancy, Dr. LaCoursiere said.

The modified Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ) was also used, and revealed that poor body image was associated with obesity and weight gain during pregnancy. Scores on the BSQ increased significantly with increasing BMI strata (32, 39, 44, 48, 51, and 49; P less than .05).

Surprisingly, only 54% of physicians discussed mood during the postpartum visit and 26% addressed weight, Dr. LaCoursiere said. Fewer than 30 women reported that their evaluation of mood was conducted with a written tool. During pregnancy, 77% of providers addressed weight and 53% discussed mood.

“It might be that we need to make this part of the nursing system so that a woman has to answer a survey when she first comes through the door, so the doctor has the information in hand,” she said. “Another thing that's tough for OBs is what to do with that result when you find it. Most should feel fairly comfortable treating at least mild depression and knowing what resources are available and whom to refer to.”

In all, 50 women (4%) reported using alcohol during pregnancy, 224 (17%) had a history of depression, 109 (9%) had a history of PPD, 23 (2%) had a history of other psychiatric diagnoses, and 175 (14%) had a family history of other psychiatric diagnoses.

At first glance, the percentage of women with a history of depression or PPD seems high. The data may be inflated because they are self-reported and thus do not necessarily reflect those who accessed care and were treated, Dr. LaCoursiere said.

DALLAS — Obese women may be at increased risk for postpartum depression, new research suggests.

In a prospective analysis of 1,282 women who gave birth to singleton infants at term, nearly 30% of women with a prepregnancy body mass index of 30 or more screened positive for postpartum depression 8 weeks after delivery.

The study is the first to use a validated screening tool to evaluate the risk of postpartum depression (PPD) by maternal BMI strata, according to the researchers, who used a score of 12 or more on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Screen to define a positive PPD screen.

Women at the extremes of BMI and those with greater weight gains in pregnancy were also at increased risk for PPD, Dr. Yvette LaCoursiere and colleagues at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

A positive PPD screen was reported in 19% of underweight women (BMI below 18.5), 13% of normal-weight (BMI 18.5–24.9), 16% of overweight women (BMI 25–29.9), 18% with class I obesity (BMI 30–34.9), 28% with class II obesity (BMI 35–39.9), and 29% with class III obesity (BMI greater than or equal to 40). The number of women in each BMI stratum was: 115, 724, 256, 116, 43, and 31, respectively, with incomplete data available on 3 others.

BMI remained a risk factor for PPD even after the researchers controlled for maternal age (mean 27 years), race (86% white, 9% Hispanic), parity (two children), education (mean 14 years), and stressors including financial, traumatic, partner associated, and emotional.

“We're not screening women aggressively for postpartum depression, in general,” Dr. LaCoursiere said in an interview. “When I look at how this changed my practice, if I have women who are obese before delivery I have them come back at a 2-week visit and make sure they get a screening test because they have a very high chance of developing depression.”

Weight gain during pregnancy also influenced a woman's chance of becoming depressed. A positive PPD screen was observed for 10% of normal-weight women who gained 24 pounds or less, 11% of those who gained 25–34 pounds, and 16% of those who gained more than 35 pounds. The rates were similar among overweight women (12%, 14%, and 20%, respectively), but did not increase in a stepwise fashion among the mildly obese (23%, 9%, and 21%, respectively). There were too few women with class II and III obesity to analyze.

Contrary to what one would expect, normal-weight women are more likely than are obese women to exceed the recommended pregnancy weight gain of 25–35 pounds, with obese women typically gaining only about 16–24 pounds during pregnancy, Dr. LaCoursiere said.

The modified Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ) was also used, and revealed that poor body image was associated with obesity and weight gain during pregnancy. Scores on the BSQ increased significantly with increasing BMI strata (32, 39, 44, 48, 51, and 49; P less than .05).

Surprisingly, only 54% of physicians discussed mood during the postpartum visit and 26% addressed weight, Dr. LaCoursiere said. Fewer than 30 women reported that their evaluation of mood was conducted with a written tool. During pregnancy, 77% of providers addressed weight and 53% discussed mood.

“It might be that we need to make this part of the nursing system so that a woman has to answer a survey when she first comes through the door, so the doctor has the information in hand,” she said. “Another thing that's tough for OBs is what to do with that result when you find it. Most should feel fairly comfortable treating at least mild depression and knowing what resources are available and whom to refer to.”

In all, 50 women (4%) reported using alcohol during pregnancy, 224 (17%) had a history of depression, 109 (9%) had a history of PPD, 23 (2%) had a history of other psychiatric diagnoses, and 175 (14%) had a family history of other psychiatric diagnoses.

At first glance, the percentage of women with a history of depression or PPD seems high. The data may be inflated because they are self-reported and thus do not necessarily reflect those who accessed care and were treated, Dr. LaCoursiere said.

DALLAS — Obese women may be at increased risk for postpartum depression, new research suggests.

In a prospective analysis of 1,282 women who gave birth to singleton infants at term, nearly 30% of women with a prepregnancy body mass index of 30 or more screened positive for postpartum depression 8 weeks after delivery.

The study is the first to use a validated screening tool to evaluate the risk of postpartum depression (PPD) by maternal BMI strata, according to the researchers, who used a score of 12 or more on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Screen to define a positive PPD screen.

Women at the extremes of BMI and those with greater weight gains in pregnancy were also at increased risk for PPD, Dr. Yvette LaCoursiere and colleagues at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, reported in a poster at the annual meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

A positive PPD screen was reported in 19% of underweight women (BMI below 18.5), 13% of normal-weight (BMI 18.5–24.9), 16% of overweight women (BMI 25–29.9), 18% with class I obesity (BMI 30–34.9), 28% with class II obesity (BMI 35–39.9), and 29% with class III obesity (BMI greater than or equal to 40). The number of women in each BMI stratum was: 115, 724, 256, 116, 43, and 31, respectively, with incomplete data available on 3 others.

BMI remained a risk factor for PPD even after the researchers controlled for maternal age (mean 27 years), race (86% white, 9% Hispanic), parity (two children), education (mean 14 years), and stressors including financial, traumatic, partner associated, and emotional.

“We're not screening women aggressively for postpartum depression, in general,” Dr. LaCoursiere said in an interview. “When I look at how this changed my practice, if I have women who are obese before delivery I have them come back at a 2-week visit and make sure they get a screening test because they have a very high chance of developing depression.”

Weight gain during pregnancy also influenced a woman's chance of becoming depressed. A positive PPD screen was observed for 10% of normal-weight women who gained 24 pounds or less, 11% of those who gained 25–34 pounds, and 16% of those who gained more than 35 pounds. The rates were similar among overweight women (12%, 14%, and 20%, respectively), but did not increase in a stepwise fashion among the mildly obese (23%, 9%, and 21%, respectively). There were too few women with class II and III obesity to analyze.

Contrary to what one would expect, normal-weight women are more likely than are obese women to exceed the recommended pregnancy weight gain of 25–35 pounds, with obese women typically gaining only about 16–24 pounds during pregnancy, Dr. LaCoursiere said.

The modified Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ) was also used, and revealed that poor body image was associated with obesity and weight gain during pregnancy. Scores on the BSQ increased significantly with increasing BMI strata (32, 39, 44, 48, 51, and 49; P less than .05).

Surprisingly, only 54% of physicians discussed mood during the postpartum visit and 26% addressed weight, Dr. LaCoursiere said. Fewer than 30 women reported that their evaluation of mood was conducted with a written tool. During pregnancy, 77% of providers addressed weight and 53% discussed mood.

“It might be that we need to make this part of the nursing system so that a woman has to answer a survey when she first comes through the door, so the doctor has the information in hand,” she said. “Another thing that's tough for OBs is what to do with that result when you find it. Most should feel fairly comfortable treating at least mild depression and knowing what resources are available and whom to refer to.”

In all, 50 women (4%) reported using alcohol during pregnancy, 224 (17%) had a history of depression, 109 (9%) had a history of PPD, 23 (2%) had a history of other psychiatric diagnoses, and 175 (14%) had a family history of other psychiatric diagnoses.

At first glance, the percentage of women with a history of depression or PPD seems high. The data may be inflated because they are self-reported and thus do not necessarily reflect those who accessed care and were treated, Dr. LaCoursiere said.

Hemangiomas Linked to Placental Abnormalities

Vascular abnormalities of the placenta were strongly correlated with the incidence of infantile hemangiomas in a small group of very-low-birth-weight infants, Dr. Juan Carlos Lopez Gutierrez and his colleagues reported.

Abnormalities such as infarcts and hematomas might create a hypoxic intraplacental environment that stimulates vasculogenesis and predisposes these infants to postnatal hemangioma growth, said Dr. Lopez and his associates of La Paz Children's Hospital, Madrid (Pediatr. Dermatol. 2007;24:353–5).

Although the study is too small to make absolute claims, it does seem to shed additional light on the prevailing theory of hemangioma pathogenesis: embolization of placental endothelial cells. “There are several different factors playing an important role in the pathogenesis of hemangiomas. Just embolization of placental cells as the origin of hemangiomas is too simple a theory,” Dr. Lopez said in an interview.

His case series suggests that placental lesions lead to a hypoxic environment that, in turn, stimulates the unopposed growth of escaped fetal endothelial cells. “Hypoxia is extremely important as a precursor lesion, and placental anomalies provoke a low-oxygen atmosphere, which is one—and probably the most important—of the suggested factors for hemangioma development,” Dr. Lopez said. His study included 26 very-low-birth-weight infants, 13 of whom developed infantile hemangiomas postnatally. The investigators examined each placenta macroscopically and microscopically.

Every placenta in the group of infants who developed hemangiomas was abnormal, they found. Two placentas showed massive retroplacental hematomas; seven showed extensive infarction; and four exhibited large dilated vascular cavitations, severe vasculitis, chorioamnionitis, and funiculitis. Cord insertion was marginal in eight, paracentral in three, and velamentous in two. Among the placentas showing infarcts, the area of ischemia was simple in two and multiple in five, with a mean infarct size of 15 mm. The infarcted areas resulted in decreased growth of peripheral villi in all tissues.

In contrast, all of the placentas of the infants without hemangiomas were free of lesions reflecting disturbed maternal-fetal circulation. Two placentas showed isolated villous immaturity. Cord insertion was central in four and paracentral in nine.

Hypoxia is an important angiogenic stimulator in fetal development. “The relatively low oxygen environment in which the human fetoplacental unit develops during the first trimester is necessary to induce vasculoangiogenesis via embryonic endothelial cells proliferation, as these cells are sensitive to hypoxia and acidosis,” Dr. Lopez and his associates noted.

Prior research suggests that abnormal placentas increase the likelihood of infantile hemangiomas through shearing and embolization of placental tissue. Thus, the hypoxic environment created by placental insufficiency could be the trigger that turns on a vasculogenic response in any endothelial cells that have escaped into a fetus's circulation, they wrote.

Dr. Paula North, chief of pediatric pathology at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, pioneered the embolization theory of hemangioma pathogenesis and said that Dr. Lopez's study raises some valid issues. “The evidence from this study is a little bit circumstantial in supporting the placental origin theory,” Dr. North said in an interview. “What it does suggest is the idea that any kind of placental injury would increase the shedding of vascular precursor cells from the placenta, which then migrate into the baby.”

Once the placental cells enter the fetus, their migratory path and growth are probably influenced by their phenotype. “The cells that make up a hemangioma express a very interesting pattern of molecules that are highly relevant to the immune system,” Dr. North said. “They express indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, which helps create a state of maternal immune tolerance to the fetus, and this could help protect the growing hemangioma from attack by activated T cells.”

Hemangioma cells also express chemokine receptor 6. Normally expressed in dendritic cells, it might influence the area where shed placental endothelial cells eventually lodge, working “like a homing mechanism to bring the cells to the skin and liver,” she said.

Vascular abnormalities of the placenta were strongly correlated with the incidence of infantile hemangiomas in a small group of very-low-birth-weight infants, Dr. Juan Carlos Lopez Gutierrez and his colleagues reported.

Abnormalities such as infarcts and hematomas might create a hypoxic intraplacental environment that stimulates vasculogenesis and predisposes these infants to postnatal hemangioma growth, said Dr. Lopez and his associates of La Paz Children's Hospital, Madrid (Pediatr. Dermatol. 2007;24:353–5).

Although the study is too small to make absolute claims, it does seem to shed additional light on the prevailing theory of hemangioma pathogenesis: embolization of placental endothelial cells. “There are several different factors playing an important role in the pathogenesis of hemangiomas. Just embolization of placental cells as the origin of hemangiomas is too simple a theory,” Dr. Lopez said in an interview.

His case series suggests that placental lesions lead to a hypoxic environment that, in turn, stimulates the unopposed growth of escaped fetal endothelial cells. “Hypoxia is extremely important as a precursor lesion, and placental anomalies provoke a low-oxygen atmosphere, which is one—and probably the most important—of the suggested factors for hemangioma development,” Dr. Lopez said. His study included 26 very-low-birth-weight infants, 13 of whom developed infantile hemangiomas postnatally. The investigators examined each placenta macroscopically and microscopically.

Every placenta in the group of infants who developed hemangiomas was abnormal, they found. Two placentas showed massive retroplacental hematomas; seven showed extensive infarction; and four exhibited large dilated vascular cavitations, severe vasculitis, chorioamnionitis, and funiculitis. Cord insertion was marginal in eight, paracentral in three, and velamentous in two. Among the placentas showing infarcts, the area of ischemia was simple in two and multiple in five, with a mean infarct size of 15 mm. The infarcted areas resulted in decreased growth of peripheral villi in all tissues.

In contrast, all of the placentas of the infants without hemangiomas were free of lesions reflecting disturbed maternal-fetal circulation. Two placentas showed isolated villous immaturity. Cord insertion was central in four and paracentral in nine.

Hypoxia is an important angiogenic stimulator in fetal development. “The relatively low oxygen environment in which the human fetoplacental unit develops during the first trimester is necessary to induce vasculoangiogenesis via embryonic endothelial cells proliferation, as these cells are sensitive to hypoxia and acidosis,” Dr. Lopez and his associates noted.

Prior research suggests that abnormal placentas increase the likelihood of infantile hemangiomas through shearing and embolization of placental tissue. Thus, the hypoxic environment created by placental insufficiency could be the trigger that turns on a vasculogenic response in any endothelial cells that have escaped into a fetus's circulation, they wrote.

Dr. Paula North, chief of pediatric pathology at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, pioneered the embolization theory of hemangioma pathogenesis and said that Dr. Lopez's study raises some valid issues. “The evidence from this study is a little bit circumstantial in supporting the placental origin theory,” Dr. North said in an interview. “What it does suggest is the idea that any kind of placental injury would increase the shedding of vascular precursor cells from the placenta, which then migrate into the baby.”

Once the placental cells enter the fetus, their migratory path and growth are probably influenced by their phenotype. “The cells that make up a hemangioma express a very interesting pattern of molecules that are highly relevant to the immune system,” Dr. North said. “They express indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, which helps create a state of maternal immune tolerance to the fetus, and this could help protect the growing hemangioma from attack by activated T cells.”

Hemangioma cells also express chemokine receptor 6. Normally expressed in dendritic cells, it might influence the area where shed placental endothelial cells eventually lodge, working “like a homing mechanism to bring the cells to the skin and liver,” she said.

Vascular abnormalities of the placenta were strongly correlated with the incidence of infantile hemangiomas in a small group of very-low-birth-weight infants, Dr. Juan Carlos Lopez Gutierrez and his colleagues reported.

Abnormalities such as infarcts and hematomas might create a hypoxic intraplacental environment that stimulates vasculogenesis and predisposes these infants to postnatal hemangioma growth, said Dr. Lopez and his associates of La Paz Children's Hospital, Madrid (Pediatr. Dermatol. 2007;24:353–5).

Although the study is too small to make absolute claims, it does seem to shed additional light on the prevailing theory of hemangioma pathogenesis: embolization of placental endothelial cells. “There are several different factors playing an important role in the pathogenesis of hemangiomas. Just embolization of placental cells as the origin of hemangiomas is too simple a theory,” Dr. Lopez said in an interview.

His case series suggests that placental lesions lead to a hypoxic environment that, in turn, stimulates the unopposed growth of escaped fetal endothelial cells. “Hypoxia is extremely important as a precursor lesion, and placental anomalies provoke a low-oxygen atmosphere, which is one—and probably the most important—of the suggested factors for hemangioma development,” Dr. Lopez said. His study included 26 very-low-birth-weight infants, 13 of whom developed infantile hemangiomas postnatally. The investigators examined each placenta macroscopically and microscopically.

Every placenta in the group of infants who developed hemangiomas was abnormal, they found. Two placentas showed massive retroplacental hematomas; seven showed extensive infarction; and four exhibited large dilated vascular cavitations, severe vasculitis, chorioamnionitis, and funiculitis. Cord insertion was marginal in eight, paracentral in three, and velamentous in two. Among the placentas showing infarcts, the area of ischemia was simple in two and multiple in five, with a mean infarct size of 15 mm. The infarcted areas resulted in decreased growth of peripheral villi in all tissues.

In contrast, all of the placentas of the infants without hemangiomas were free of lesions reflecting disturbed maternal-fetal circulation. Two placentas showed isolated villous immaturity. Cord insertion was central in four and paracentral in nine.

Hypoxia is an important angiogenic stimulator in fetal development. “The relatively low oxygen environment in which the human fetoplacental unit develops during the first trimester is necessary to induce vasculoangiogenesis via embryonic endothelial cells proliferation, as these cells are sensitive to hypoxia and acidosis,” Dr. Lopez and his associates noted.

Prior research suggests that abnormal placentas increase the likelihood of infantile hemangiomas through shearing and embolization of placental tissue. Thus, the hypoxic environment created by placental insufficiency could be the trigger that turns on a vasculogenic response in any endothelial cells that have escaped into a fetus's circulation, they wrote.

Dr. Paula North, chief of pediatric pathology at the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, pioneered the embolization theory of hemangioma pathogenesis and said that Dr. Lopez's study raises some valid issues. “The evidence from this study is a little bit circumstantial in supporting the placental origin theory,” Dr. North said in an interview. “What it does suggest is the idea that any kind of placental injury would increase the shedding of vascular precursor cells from the placenta, which then migrate into the baby.”

Once the placental cells enter the fetus, their migratory path and growth are probably influenced by their phenotype. “The cells that make up a hemangioma express a very interesting pattern of molecules that are highly relevant to the immune system,” Dr. North said. “They express indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, which helps create a state of maternal immune tolerance to the fetus, and this could help protect the growing hemangioma from attack by activated T cells.”

Hemangioma cells also express chemokine receptor 6. Normally expressed in dendritic cells, it might influence the area where shed placental endothelial cells eventually lodge, working “like a homing mechanism to bring the cells to the skin and liver,” she said.

IVF Twin Pregnancies Raise Anxiety, but Not Depression

WASHINGTON — Anxiety—but not depression—was higher among women with twin pregnancies than in women with singleton pregnancies after in vitro fertilization, reported Dr. Farnaz Jahangiri of Northwestern University, Chicago.

In this study, presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, Dr. Jahangiri and colleagues interviewed women at the confirmation of their pregnancies and again at 10–12 weeks' gestation and 21–22 weeks' gestation. The study included 48 singleton pregnancies and 13 sets of twins, and there were no significant demographic differences between the two groups.

The investigators found no differences in depression scores between the women with singleton vs. twin pregnancies at any of the three time points. By contrast, the women with twin pregnancies averaged higher (but not significantly higher) anxiety scores than the singleton group at 10–12 weeks and significantly higher anxiety scores at 22–23 weeks.

Psychological traits in singleton vs. twin IVF pregnancies have not been widely studied. But previous research has shown that women who are pregnant after IVF become less anxious as their pregnancies progress and their self-esteem increases.

The new findings of increased anxiety among women with IVF twin pregnancies during the second trimester can help clinicians discuss the risks associated with multiple gestations when they counsel women who are undergoing infertility treatments, according to the researchers. Depression was assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Anxiety was assessed using the Spielberger State and Trait Anxiety Inventory.

WASHINGTON — Anxiety—but not depression—was higher among women with twin pregnancies than in women with singleton pregnancies after in vitro fertilization, reported Dr. Farnaz Jahangiri of Northwestern University, Chicago.

In this study, presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, Dr. Jahangiri and colleagues interviewed women at the confirmation of their pregnancies and again at 10–12 weeks' gestation and 21–22 weeks' gestation. The study included 48 singleton pregnancies and 13 sets of twins, and there were no significant demographic differences between the two groups.

The investigators found no differences in depression scores between the women with singleton vs. twin pregnancies at any of the three time points. By contrast, the women with twin pregnancies averaged higher (but not significantly higher) anxiety scores than the singleton group at 10–12 weeks and significantly higher anxiety scores at 22–23 weeks.

Psychological traits in singleton vs. twin IVF pregnancies have not been widely studied. But previous research has shown that women who are pregnant after IVF become less anxious as their pregnancies progress and their self-esteem increases.

The new findings of increased anxiety among women with IVF twin pregnancies during the second trimester can help clinicians discuss the risks associated with multiple gestations when they counsel women who are undergoing infertility treatments, according to the researchers. Depression was assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Anxiety was assessed using the Spielberger State and Trait Anxiety Inventory.

WASHINGTON — Anxiety—but not depression—was higher among women with twin pregnancies than in women with singleton pregnancies after in vitro fertilization, reported Dr. Farnaz Jahangiri of Northwestern University, Chicago.

In this study, presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, Dr. Jahangiri and colleagues interviewed women at the confirmation of their pregnancies and again at 10–12 weeks' gestation and 21–22 weeks' gestation. The study included 48 singleton pregnancies and 13 sets of twins, and there were no significant demographic differences between the two groups.

The investigators found no differences in depression scores between the women with singleton vs. twin pregnancies at any of the three time points. By contrast, the women with twin pregnancies averaged higher (but not significantly higher) anxiety scores than the singleton group at 10–12 weeks and significantly higher anxiety scores at 22–23 weeks.

Psychological traits in singleton vs. twin IVF pregnancies have not been widely studied. But previous research has shown that women who are pregnant after IVF become less anxious as their pregnancies progress and their self-esteem increases.

The new findings of increased anxiety among women with IVF twin pregnancies during the second trimester can help clinicians discuss the risks associated with multiple gestations when they counsel women who are undergoing infertility treatments, according to the researchers. Depression was assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Anxiety was assessed using the Spielberger State and Trait Anxiety Inventory.

High OGTT in Pregnacy Ups Later Diabetes Risk

Women who have an abnormal glucose tolerance test result during pregnancy but do not develop gestational diabetes still face an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes later on, investigators reported.

The large retrospective study, published Jan. 25, concluded that even modestly elevated glucose levels double the risk of diabetes within the next 9 years. “The risk of subsequent diabetes … likely occurs since these women have an intermediate form of glucose intolerance” with impaired β-cell functioning, wrote Dr. Darcy B. Carr of the University of Washington, Seattle, and her coauthors (Diabetes Care 2008 Jan. 25 [doi 10.2337/dc07–1957]).

In this retrospective cohort study, the researchers analyzed diabetes risk over a mean 9-year follow-up period in 31,000 women without gestational diabetes who had an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) or oral glucose challenge test (OGCT) during their pregnancy. The mean age was 31 years; the median follow-up was 9 years.

The investigators found that the risk of later development of type 2 diabetes rose as the values of the OGCT rose. Compared with women whose levels were normal, women with glucose levels of 5.4–6.2 mmol/L and 6.4–7.3 mmol/L had double the risk of developing the disease, while women with levels greater than 7.3 mmol/L were three times more likely to do so. Women with no abnormal values on the OGTT were at no increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes, but those with one abnormal value were twice as likely to do so.

These associations remained significant even after the researchers controlled for age, primigravidity, and preterm delivery.

The finding is consistent with those from a previous, much smaller longitudinal study that reported higher frequencies of glucose intolerance in women with one abnormal OGTT value.

Dr. Carr and her colleagues noted that their study could not control for race, family history, or body mass index—all important factors to consider when assessing diabetes risk. In addition, subsequent diabetes was not systematically assessed, which may introduce bias in those who were selected for testing, they wrote.

They also said their conclusions are not sufficient for them to make any screening or treatment recommendations: “Whether women who fall within this intermediate range of glucose intolerance during pregnancy may benefit from increased diabetes surveillance as well as lifestyle recommendations proven to reduce the risk of developing diabetes is unknown.”

Women who have an abnormal glucose tolerance test result during pregnancy but do not develop gestational diabetes still face an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes later on, investigators reported.

The large retrospective study, published Jan. 25, concluded that even modestly elevated glucose levels double the risk of diabetes within the next 9 years. “The risk of subsequent diabetes … likely occurs since these women have an intermediate form of glucose intolerance” with impaired β-cell functioning, wrote Dr. Darcy B. Carr of the University of Washington, Seattle, and her coauthors (Diabetes Care 2008 Jan. 25 [doi 10.2337/dc07–1957]).

In this retrospective cohort study, the researchers analyzed diabetes risk over a mean 9-year follow-up period in 31,000 women without gestational diabetes who had an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) or oral glucose challenge test (OGCT) during their pregnancy. The mean age was 31 years; the median follow-up was 9 years.

The investigators found that the risk of later development of type 2 diabetes rose as the values of the OGCT rose. Compared with women whose levels were normal, women with glucose levels of 5.4–6.2 mmol/L and 6.4–7.3 mmol/L had double the risk of developing the disease, while women with levels greater than 7.3 mmol/L were three times more likely to do so. Women with no abnormal values on the OGTT were at no increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes, but those with one abnormal value were twice as likely to do so.

These associations remained significant even after the researchers controlled for age, primigravidity, and preterm delivery.

The finding is consistent with those from a previous, much smaller longitudinal study that reported higher frequencies of glucose intolerance in women with one abnormal OGTT value.

Dr. Carr and her colleagues noted that their study could not control for race, family history, or body mass index—all important factors to consider when assessing diabetes risk. In addition, subsequent diabetes was not systematically assessed, which may introduce bias in those who were selected for testing, they wrote.

They also said their conclusions are not sufficient for them to make any screening or treatment recommendations: “Whether women who fall within this intermediate range of glucose intolerance during pregnancy may benefit from increased diabetes surveillance as well as lifestyle recommendations proven to reduce the risk of developing diabetes is unknown.”

Women who have an abnormal glucose tolerance test result during pregnancy but do not develop gestational diabetes still face an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes later on, investigators reported.

The large retrospective study, published Jan. 25, concluded that even modestly elevated glucose levels double the risk of diabetes within the next 9 years. “The risk of subsequent diabetes … likely occurs since these women have an intermediate form of glucose intolerance” with impaired β-cell functioning, wrote Dr. Darcy B. Carr of the University of Washington, Seattle, and her coauthors (Diabetes Care 2008 Jan. 25 [doi 10.2337/dc07–1957]).

In this retrospective cohort study, the researchers analyzed diabetes risk over a mean 9-year follow-up period in 31,000 women without gestational diabetes who had an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) or oral glucose challenge test (OGCT) during their pregnancy. The mean age was 31 years; the median follow-up was 9 years.

The investigators found that the risk of later development of type 2 diabetes rose as the values of the OGCT rose. Compared with women whose levels were normal, women with glucose levels of 5.4–6.2 mmol/L and 6.4–7.3 mmol/L had double the risk of developing the disease, while women with levels greater than 7.3 mmol/L were three times more likely to do so. Women with no abnormal values on the OGTT were at no increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes, but those with one abnormal value were twice as likely to do so.

These associations remained significant even after the researchers controlled for age, primigravidity, and preterm delivery.

The finding is consistent with those from a previous, much smaller longitudinal study that reported higher frequencies of glucose intolerance in women with one abnormal OGTT value.

Dr. Carr and her colleagues noted that their study could not control for race, family history, or body mass index—all important factors to consider when assessing diabetes risk. In addition, subsequent diabetes was not systematically assessed, which may introduce bias in those who were selected for testing, they wrote.

They also said their conclusions are not sufficient for them to make any screening or treatment recommendations: “Whether women who fall within this intermediate range of glucose intolerance during pregnancy may benefit from increased diabetes surveillance as well as lifestyle recommendations proven to reduce the risk of developing diabetes is unknown.”

Peer Support May Avert Postpartum Depression

MONTREAL — Mother-to-mother support can significantly reduce the development of postpartum depression in women who are at high risk for the condition, Cindy-Lee Dennis, Ph.D., said at the annual conference of the Canadian Psychiatric Association.

“Meta-analyses and predictive studies have clearly suggested the importance of psychosocial variables in the development of postpartum depression,” said Dr. Dennis of the Lawrence S. Bloomberg Faculty of Nursing at the University of Toronto.

“When we look at support variables in particular, it's the lack of a confidante that places the mother at risk for postpartum depression,” she noted.

Her study involved 701 women who were less than 2 weeks post partum and considered to be at high risk for developing postpartum depression based on an Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) score of greater than 9.

The women were randomized to a control group (n = 352), which received usual postpartum care, or an intervention group (n = 349) that received usual postpartum care plus telephone peer support. A total of 205 peer-support volunteers, all of whom had recovered from self-reported postpartum depression, were recruited from the community through fliers and advertising. They were given a 4-hour training session and then matched to the new mothers based on health region, and, if the mother desired, on ethnicity.

For the primary outcome measure, an EPDS score of greater than 12, the study found a significant benefit to peer support. “Mothers who received the intervention were two times less likely to develop postpartum depression,” said Dr. Dennis, who reported an incidence of 13.5% in the intervention group and a 26% incidence in the control group.

A secondary outcome measure of anxiety also favored the intervention, with incidences of 20.6% in the intervention group and 26.9% in the control group. “This is bordering on statistical significance, but we think it is clinically relevant and suggests anxiety might be relieved with peer support,” she said.

There were no differences between the groups in their reports of loneliness.

Predictors of a baseline EPDS score of greater than 12 included non-Canadian ethnicity (reported by 19% of participants), not having been born in Canada (reported by 41% of participants), new immigrant status with less than 5 years in Canada (reported by 43% of those not born in Canada), and no family support (reported by 12% of participants). A total of 59% of the participants were primiparous, 31% had a history of depression, 18% had no mother to talk to, and almost 10% were very unhappy with the baby's father.

“Because this was a prevention trial, we felt it was unethical to leave a depressed mother in the community. So we administered the SCID [Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders), and if they were diagnosed with clinical depression or had an EPDS score greater than 20, then we referred them back to the public health department and public health did follow up with them,” said Dr. Dennis.

MONTREAL — Mother-to-mother support can significantly reduce the development of postpartum depression in women who are at high risk for the condition, Cindy-Lee Dennis, Ph.D., said at the annual conference of the Canadian Psychiatric Association.

“Meta-analyses and predictive studies have clearly suggested the importance of psychosocial variables in the development of postpartum depression,” said Dr. Dennis of the Lawrence S. Bloomberg Faculty of Nursing at the University of Toronto.

“When we look at support variables in particular, it's the lack of a confidante that places the mother at risk for postpartum depression,” she noted.

Her study involved 701 women who were less than 2 weeks post partum and considered to be at high risk for developing postpartum depression based on an Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) score of greater than 9.

The women were randomized to a control group (n = 352), which received usual postpartum care, or an intervention group (n = 349) that received usual postpartum care plus telephone peer support. A total of 205 peer-support volunteers, all of whom had recovered from self-reported postpartum depression, were recruited from the community through fliers and advertising. They were given a 4-hour training session and then matched to the new mothers based on health region, and, if the mother desired, on ethnicity.

For the primary outcome measure, an EPDS score of greater than 12, the study found a significant benefit to peer support. “Mothers who received the intervention were two times less likely to develop postpartum depression,” said Dr. Dennis, who reported an incidence of 13.5% in the intervention group and a 26% incidence in the control group.

A secondary outcome measure of anxiety also favored the intervention, with incidences of 20.6% in the intervention group and 26.9% in the control group. “This is bordering on statistical significance, but we think it is clinically relevant and suggests anxiety might be relieved with peer support,” she said.

There were no differences between the groups in their reports of loneliness.

Predictors of a baseline EPDS score of greater than 12 included non-Canadian ethnicity (reported by 19% of participants), not having been born in Canada (reported by 41% of participants), new immigrant status with less than 5 years in Canada (reported by 43% of those not born in Canada), and no family support (reported by 12% of participants). A total of 59% of the participants were primiparous, 31% had a history of depression, 18% had no mother to talk to, and almost 10% were very unhappy with the baby's father.

“Because this was a prevention trial, we felt it was unethical to leave a depressed mother in the community. So we administered the SCID [Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders), and if they were diagnosed with clinical depression or had an EPDS score greater than 20, then we referred them back to the public health department and public health did follow up with them,” said Dr. Dennis.

MONTREAL — Mother-to-mother support can significantly reduce the development of postpartum depression in women who are at high risk for the condition, Cindy-Lee Dennis, Ph.D., said at the annual conference of the Canadian Psychiatric Association.

“Meta-analyses and predictive studies have clearly suggested the importance of psychosocial variables in the development of postpartum depression,” said Dr. Dennis of the Lawrence S. Bloomberg Faculty of Nursing at the University of Toronto.

“When we look at support variables in particular, it's the lack of a confidante that places the mother at risk for postpartum depression,” she noted.

Her study involved 701 women who were less than 2 weeks post partum and considered to be at high risk for developing postpartum depression based on an Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) score of greater than 9.

The women were randomized to a control group (n = 352), which received usual postpartum care, or an intervention group (n = 349) that received usual postpartum care plus telephone peer support. A total of 205 peer-support volunteers, all of whom had recovered from self-reported postpartum depression, were recruited from the community through fliers and advertising. They were given a 4-hour training session and then matched to the new mothers based on health region, and, if the mother desired, on ethnicity.

For the primary outcome measure, an EPDS score of greater than 12, the study found a significant benefit to peer support. “Mothers who received the intervention were two times less likely to develop postpartum depression,” said Dr. Dennis, who reported an incidence of 13.5% in the intervention group and a 26% incidence in the control group.

A secondary outcome measure of anxiety also favored the intervention, with incidences of 20.6% in the intervention group and 26.9% in the control group. “This is bordering on statistical significance, but we think it is clinically relevant and suggests anxiety might be relieved with peer support,” she said.

There were no differences between the groups in their reports of loneliness.

Predictors of a baseline EPDS score of greater than 12 included non-Canadian ethnicity (reported by 19% of participants), not having been born in Canada (reported by 41% of participants), new immigrant status with less than 5 years in Canada (reported by 43% of those not born in Canada), and no family support (reported by 12% of participants). A total of 59% of the participants were primiparous, 31% had a history of depression, 18% had no mother to talk to, and almost 10% were very unhappy with the baby's father.

“Because this was a prevention trial, we felt it was unethical to leave a depressed mother in the community. So we administered the SCID [Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders), and if they were diagnosed with clinical depression or had an EPDS score greater than 20, then we referred them back to the public health department and public health did follow up with them,” said Dr. Dennis.

Update: Bacterial Vaginosis Screening in Pregnancy

Updated recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force advise against screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnant women who are asymptomatic and at low risk for preterm delivery.

However, the recommendations remain neutral about such screening in high-risk pregnancies because “current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms,” reported Dr. Ned Calonge, chair of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and his colleagues.

The new recommendations (Ann. Intern. Med. 2008;148:214–9) are an update of those compiled by the task force in 2001 (Am. J. Prev. Med. 2001;20:59–61). They are based on an analysis of new evidence, which was conducted for the task force by Peggy Nygren of the Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, and her associates and funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Ann. Intern. Med. 2008;148:220–33).

The analysis addressed “previously identified gaps, such as the characterization of patients most likely to benefit from screening and the optimal timing of screening and treatment in pregnancy outcomes,” said Dr. Calonge, who is also chief medical officer of the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, Denver, and his colleagues.

Ms. Nygren and her associates noted the recent concerns that metronidazole—the antibiotic most commonly used to treat bacterial vaginosis—might increase preterm births in certain populations. “The juxtaposition of these data, along with epidemiologic evidence associating bacterial vaginosis with preterm birth, leads to considerable confusion for clinicians and researchers alike. Whether to screen or treat multiple times, when to start, and at what interval during pregnancy are unanswered questions, as bacterial vaginosis may not necessarily persist throughout pregnancy,” they wrote.

The analysis included studies published after the release of the task force's 2001 recommendations to examine “new evidence on the benefits and harms of screening and treating bacterial vaginosis in asymptomatic pregnant women.”

Asymptomatic patients were defined as those presenting for routine prenatal care and not for evaluation of vaginal discharge, odor, or itching. Low-risk patients were defined as having no history of and no risk factors for preterm delivery, whereas average-risk patients were defined as “the general population,” regardless of risk status. Women with a history of preterm delivery related to spontaneous rupture of membranes or spontaneous preterm labor were categorized as high risk.

The analysis found no benefit in treating women with low- or average-risk pregnancies if they were asymptomatic. For high-risk asymptomatic pregnancies, Ms. Nygren and her colleagues noted that findings from one trial that had been published since the USPSTF 2001 recommendations showed “a significant adverse effect of treatment on delivery before 37 weeks” in 127 women, “indicating that treatment of bacterial vaginosis increased the chance of preterm delivery” significantly (S. Afr. Med. J. 2002;92:231–4).

However, when this study was considered with previous studies that had been included in the 2001 recommendations, the results were “heterogenous and conflicting,” they wrote.

For the outcome of delivery before 37 weeks, three of the trials reported a significant treatment benefit, one showed significant treatment harm, and one showed no benefit.

In keeping with the USPSTF recommendation against screening in low-risk pregnancies, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group, the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV/Clinical Effectiveness Group (BASHH), and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) have similar recommendations, according to the authors of the task force's report.

However, although the task force maintains its neutral position regarding high-risk pregnancies, the CDC, ACOG, AAFP and BASHH say there might be high-risk women for whom screening and treatment may be beneficial, the USPSTF authors wrote, noting that optimal treatment for bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy remains unclear.

Updated recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force advise against screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnant women who are asymptomatic and at low risk for preterm delivery.

However, the recommendations remain neutral about such screening in high-risk pregnancies because “current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms,” reported Dr. Ned Calonge, chair of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and his colleagues.

The new recommendations (Ann. Intern. Med. 2008;148:214–9) are an update of those compiled by the task force in 2001 (Am. J. Prev. Med. 2001;20:59–61). They are based on an analysis of new evidence, which was conducted for the task force by Peggy Nygren of the Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, and her associates and funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Ann. Intern. Med. 2008;148:220–33).

The analysis addressed “previously identified gaps, such as the characterization of patients most likely to benefit from screening and the optimal timing of screening and treatment in pregnancy outcomes,” said Dr. Calonge, who is also chief medical officer of the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, Denver, and his colleagues.

Ms. Nygren and her associates noted the recent concerns that metronidazole—the antibiotic most commonly used to treat bacterial vaginosis—might increase preterm births in certain populations. “The juxtaposition of these data, along with epidemiologic evidence associating bacterial vaginosis with preterm birth, leads to considerable confusion for clinicians and researchers alike. Whether to screen or treat multiple times, when to start, and at what interval during pregnancy are unanswered questions, as bacterial vaginosis may not necessarily persist throughout pregnancy,” they wrote.

The analysis included studies published after the release of the task force's 2001 recommendations to examine “new evidence on the benefits and harms of screening and treating bacterial vaginosis in asymptomatic pregnant women.”

Asymptomatic patients were defined as those presenting for routine prenatal care and not for evaluation of vaginal discharge, odor, or itching. Low-risk patients were defined as having no history of and no risk factors for preterm delivery, whereas average-risk patients were defined as “the general population,” regardless of risk status. Women with a history of preterm delivery related to spontaneous rupture of membranes or spontaneous preterm labor were categorized as high risk.

The analysis found no benefit in treating women with low- or average-risk pregnancies if they were asymptomatic. For high-risk asymptomatic pregnancies, Ms. Nygren and her colleagues noted that findings from one trial that had been published since the USPSTF 2001 recommendations showed “a significant adverse effect of treatment on delivery before 37 weeks” in 127 women, “indicating that treatment of bacterial vaginosis increased the chance of preterm delivery” significantly (S. Afr. Med. J. 2002;92:231–4).

However, when this study was considered with previous studies that had been included in the 2001 recommendations, the results were “heterogenous and conflicting,” they wrote.

For the outcome of delivery before 37 weeks, three of the trials reported a significant treatment benefit, one showed significant treatment harm, and one showed no benefit.

In keeping with the USPSTF recommendation against screening in low-risk pregnancies, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group, the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV/Clinical Effectiveness Group (BASHH), and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) have similar recommendations, according to the authors of the task force's report.

However, although the task force maintains its neutral position regarding high-risk pregnancies, the CDC, ACOG, AAFP and BASHH say there might be high-risk women for whom screening and treatment may be beneficial, the USPSTF authors wrote, noting that optimal treatment for bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy remains unclear.

Updated recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force advise against screening for bacterial vaginosis in pregnant women who are asymptomatic and at low risk for preterm delivery.

However, the recommendations remain neutral about such screening in high-risk pregnancies because “current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms,” reported Dr. Ned Calonge, chair of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and his colleagues.

The new recommendations (Ann. Intern. Med. 2008;148:214–9) are an update of those compiled by the task force in 2001 (Am. J. Prev. Med. 2001;20:59–61). They are based on an analysis of new evidence, which was conducted for the task force by Peggy Nygren of the Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, and her associates and funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Ann. Intern. Med. 2008;148:220–33).

The analysis addressed “previously identified gaps, such as the characterization of patients most likely to benefit from screening and the optimal timing of screening and treatment in pregnancy outcomes,” said Dr. Calonge, who is also chief medical officer of the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, Denver, and his colleagues.

Ms. Nygren and her associates noted the recent concerns that metronidazole—the antibiotic most commonly used to treat bacterial vaginosis—might increase preterm births in certain populations. “The juxtaposition of these data, along with epidemiologic evidence associating bacterial vaginosis with preterm birth, leads to considerable confusion for clinicians and researchers alike. Whether to screen or treat multiple times, when to start, and at what interval during pregnancy are unanswered questions, as bacterial vaginosis may not necessarily persist throughout pregnancy,” they wrote.

The analysis included studies published after the release of the task force's 2001 recommendations to examine “new evidence on the benefits and harms of screening and treating bacterial vaginosis in asymptomatic pregnant women.”

Asymptomatic patients were defined as those presenting for routine prenatal care and not for evaluation of vaginal discharge, odor, or itching. Low-risk patients were defined as having no history of and no risk factors for preterm delivery, whereas average-risk patients were defined as “the general population,” regardless of risk status. Women with a history of preterm delivery related to spontaneous rupture of membranes or spontaneous preterm labor were categorized as high risk.

The analysis found no benefit in treating women with low- or average-risk pregnancies if they were asymptomatic. For high-risk asymptomatic pregnancies, Ms. Nygren and her colleagues noted that findings from one trial that had been published since the USPSTF 2001 recommendations showed “a significant adverse effect of treatment on delivery before 37 weeks” in 127 women, “indicating that treatment of bacterial vaginosis increased the chance of preterm delivery” significantly (S. Afr. Med. J. 2002;92:231–4).

However, when this study was considered with previous studies that had been included in the 2001 recommendations, the results were “heterogenous and conflicting,” they wrote.

For the outcome of delivery before 37 weeks, three of the trials reported a significant treatment benefit, one showed significant treatment harm, and one showed no benefit.

In keeping with the USPSTF recommendation against screening in low-risk pregnancies, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group, the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV/Clinical Effectiveness Group (BASHH), and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) have similar recommendations, according to the authors of the task force's report.

However, although the task force maintains its neutral position regarding high-risk pregnancies, the CDC, ACOG, AAFP and BASHH say there might be high-risk women for whom screening and treatment may be beneficial, the USPSTF authors wrote, noting that optimal treatment for bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy remains unclear.

Malpractice Chronicle

Reprinted with permission from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements and Experts, Lewis Laska, Editor, (800) 298-6288.

Ethmoid Roof Penetrated During Sinus Surgery

The plaintiff, a 14-year-old boy, was evaluated by his pediatrician, then by a family physician, for pain in his left cheek and significant postnasal drip. He was given several courses of antibiotics, which did not relieve his symptoms. He was then referred to the defendant otolaryngologist, who recommended endoscopic sinus surgery.

The procedure, performed one month after the boy’s initial presentation, included four endoscopic bilateral procedures (total ethmoidectomy, maxillary sinus antrostomy, frontal sinusotomy, and reduction of inferior turbinates), in addition to partial resection of the left middle turbinate. The surgery left the patient with persistent bitemporal headaches, photophobia, and phonophobia.

The plaintiff claimed that during surgery, the right ethmoid roof was penetrated, causing a bone shard to become dislodged. A review of the materials sent to pathology after surgery, the plaintiff said, revealed the presence of brain matter. The plaintiff claimed negligence in the performance of the procedures and lack of informed consent.

According to a published report, a defense verdict was returned. Posttrial motions were pending.

”He Said, She Said” Over Obstetrics Patient

A 24-year-old woman expecting her second child went to the defendant hospital in labor. The defendant anesthesiologist, Dr. R., administered an epidural anesthetic block.

About 15 minutes later, the patient complained of difficulty breathing, and a nurse responded by raising the head of the bed, administering oxygen by mask, and calling Dr. R. to return to the room. The plaintiff soon complained of not being able to feel her legs and said she felt nauseous. She vomited and again complained of having trouble breathing.

The nurse made an emergency call for Dr. R. to return and began to administer oxygen using a manual ventilator. The anesthesiologist arrived, ordered the ventilation to be stopped, and pronounced the patient fine. The nurse, contesting this determination, placed a pulse oximetry clip on the patient; her oxygen saturation was measured at 62%.

The nurse urged intubation, but when Dr. R. attempted the intervention, he placed the tube into the esophagus rather than the trachea. The nurse then called a “code 99” emergency.

Responding members of the code team testified that Dr. R. had misplaced the intubation tube and that when the team leader attempted to reintubate the patient, Dr. R. shouted an expletive and shoved him away (which Dr. R. denied). Dr. R. then intubated the woman but did not secure the intubation tube. The code team leader also claimed that Dr. R. called for defibrillation, although the patient had a nonshockable rhythm.

An emergency cesarean delivery was performed, after which the code team defibrillated the patient. This maneuver apparently dislodged the intubation tube, necessitating a third intubation. The patient then began spontaneous respirations.

The plaintiff suffered anoxic brain injury. Despite three months of inpatient rehabilitation, she has the mental acuity of a five- to six-year-old and requires constant supervision.