User login

Appendix linked to Parkinson’s disease in series of unexpected findings

Appendectomy has been associated with a reduced risk of Parkinson’s disease (PD), which supports the potential for a reservoir of aggregated alpha-synuclein in the appendix to affect risk of the condition, according to new epidemiologic and translational evidence from two data sets that promotes a new and emerging theory for PD etiology.

When placed into the context of other recent studies, these epidemiologic data “point to the appendix as a site of origin for Parkinson’s and provide a path forward for devising new treatment strategies,” reported senior author Viviane Labrie, PhD, of the Van Andel Research Institute (VARI) in Grand Rapids, Mich.

The epidemiologic data was the most recent step in a series of findings summarized in a newly published paper in Science Translational Medicine. As the researchers explained, it is relevant to a separate body of evidence that alpha-synuclein, a protein that serves as the hallmark of PD when it appears in Lewy bodies, can be isolated in the nerve fibers and nerve cells of the appendix.

“We have shown that alpha-synuclein proteins, including the truncated forms observed in Lewy bodies, are abundant in the appendix,” reported first author Bryan A. Killinger, PhD, also at VARI, in a press teleconference. He said this finding is likely to explain the reduced risk of PD from appendectomy.

In the largest of the epidemiologic studies, the effect of appendectomy on subsequent risk of PD was evaluated through the health records from more than 1.6 million individuals in Sweden. The incidence of PD was found to be 19.3% lower among 551,647 patients who had an appendectomy, compared with controls.

In addition, the data showed that when PD did occur after appendectomy, it was delayed on average by 3.6 years. It is notable that appendectomy was not associated with protection from PD in patients with a familial link to PD, a group they said comprises less than 10% of cases.

In patients with PD, nonmotor symptoms often include GI tract dysfunction, which can, in some cases, be part of a prodromal presentation that precedes the onset of classical PD symptoms by several years, the authors reported. However, the new research upends previous conceptions of disease. The demonstration of abundant alpha-synuclein in the appendix coupled with the protective effect of appendectomy, suggests that PD may originate in the GI tract and then spread to the central nervous system (CNS) rather than the other way around.

“The vermiform appendix was once considered to be an unnecessary organ. Although there is now good evidence that the appendix plays a major role in the regulation of the immune system, including the regulation of gut bacteria, our work suggests it is also mediates risk of Parkinson’s,” Dr. Labrie said in the teleconference.

In the paper, numerous pieces of the puzzle are brought together to suggest that alpha-synuclein in the appendix is linked to alpha-synuclein in the CNS. Many of the findings along this investigative pathway were described as surprising. For example, immunohistochemistry studies revealed high amounts of alpha-synuclein in nearly every sample of appendiceal tissue examined, including normal and inflamed tissue, tissue from individuals with PD and those without, and tissues from young and old individuals.

“The normal tissue, as well as appendiceal tissue from PD patients, contained high levels of alpha-synuclein in the truncated forms analogous to those seen in Lewy body pathology,” Dr. Killinger said. Based on these and other findings, he believes that alpha-synuclein in the appendix forms a reservoir for seeding the aggregates involved in the pathology of PD, although he acknowledged that it is not yet clear how the proteins in the appendix find their way to the brain.

From these data, it appears that most individuals with an intact appendix have alpha-synuclein in the nerve fibers, but Dr. Labrie pointed out that the only about 1% of the population develops PD. She speculated that there is “some confluence of events,” such as an environmental trigger altering the GI microbiome, that mediates ultimate risk of PD, but she noted that these events may take place decades before signs and symptoms of PD develop. The data appear to be a substantial reorientation in understanding PD.

“We have shown that the appendix is a hub for the accumulation of clumped forms of alpha-synuclein proteins, which are implicated in Parkinson’s,” Dr. Killinger said. “This knowledge will be invaluable as we explore new prevention and treatment strategies.”

The research was funded by a variety of governmental and private grants to individual authors. Dr. Killinger and Dr. Labrie report no financial relationships relevant to this study.

SOURCE: Killinger BA et al. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10:eaar5380.

Appendectomy has been associated with a reduced risk of Parkinson’s disease (PD), which supports the potential for a reservoir of aggregated alpha-synuclein in the appendix to affect risk of the condition, according to new epidemiologic and translational evidence from two data sets that promotes a new and emerging theory for PD etiology.

When placed into the context of other recent studies, these epidemiologic data “point to the appendix as a site of origin for Parkinson’s and provide a path forward for devising new treatment strategies,” reported senior author Viviane Labrie, PhD, of the Van Andel Research Institute (VARI) in Grand Rapids, Mich.

The epidemiologic data was the most recent step in a series of findings summarized in a newly published paper in Science Translational Medicine. As the researchers explained, it is relevant to a separate body of evidence that alpha-synuclein, a protein that serves as the hallmark of PD when it appears in Lewy bodies, can be isolated in the nerve fibers and nerve cells of the appendix.

“We have shown that alpha-synuclein proteins, including the truncated forms observed in Lewy bodies, are abundant in the appendix,” reported first author Bryan A. Killinger, PhD, also at VARI, in a press teleconference. He said this finding is likely to explain the reduced risk of PD from appendectomy.

In the largest of the epidemiologic studies, the effect of appendectomy on subsequent risk of PD was evaluated through the health records from more than 1.6 million individuals in Sweden. The incidence of PD was found to be 19.3% lower among 551,647 patients who had an appendectomy, compared with controls.

In addition, the data showed that when PD did occur after appendectomy, it was delayed on average by 3.6 years. It is notable that appendectomy was not associated with protection from PD in patients with a familial link to PD, a group they said comprises less than 10% of cases.

In patients with PD, nonmotor symptoms often include GI tract dysfunction, which can, in some cases, be part of a prodromal presentation that precedes the onset of classical PD symptoms by several years, the authors reported. However, the new research upends previous conceptions of disease. The demonstration of abundant alpha-synuclein in the appendix coupled with the protective effect of appendectomy, suggests that PD may originate in the GI tract and then spread to the central nervous system (CNS) rather than the other way around.

“The vermiform appendix was once considered to be an unnecessary organ. Although there is now good evidence that the appendix plays a major role in the regulation of the immune system, including the regulation of gut bacteria, our work suggests it is also mediates risk of Parkinson’s,” Dr. Labrie said in the teleconference.

In the paper, numerous pieces of the puzzle are brought together to suggest that alpha-synuclein in the appendix is linked to alpha-synuclein in the CNS. Many of the findings along this investigative pathway were described as surprising. For example, immunohistochemistry studies revealed high amounts of alpha-synuclein in nearly every sample of appendiceal tissue examined, including normal and inflamed tissue, tissue from individuals with PD and those without, and tissues from young and old individuals.

“The normal tissue, as well as appendiceal tissue from PD patients, contained high levels of alpha-synuclein in the truncated forms analogous to those seen in Lewy body pathology,” Dr. Killinger said. Based on these and other findings, he believes that alpha-synuclein in the appendix forms a reservoir for seeding the aggregates involved in the pathology of PD, although he acknowledged that it is not yet clear how the proteins in the appendix find their way to the brain.

From these data, it appears that most individuals with an intact appendix have alpha-synuclein in the nerve fibers, but Dr. Labrie pointed out that the only about 1% of the population develops PD. She speculated that there is “some confluence of events,” such as an environmental trigger altering the GI microbiome, that mediates ultimate risk of PD, but she noted that these events may take place decades before signs and symptoms of PD develop. The data appear to be a substantial reorientation in understanding PD.

“We have shown that the appendix is a hub for the accumulation of clumped forms of alpha-synuclein proteins, which are implicated in Parkinson’s,” Dr. Killinger said. “This knowledge will be invaluable as we explore new prevention and treatment strategies.”

The research was funded by a variety of governmental and private grants to individual authors. Dr. Killinger and Dr. Labrie report no financial relationships relevant to this study.

SOURCE: Killinger BA et al. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10:eaar5380.

Appendectomy has been associated with a reduced risk of Parkinson’s disease (PD), which supports the potential for a reservoir of aggregated alpha-synuclein in the appendix to affect risk of the condition, according to new epidemiologic and translational evidence from two data sets that promotes a new and emerging theory for PD etiology.

When placed into the context of other recent studies, these epidemiologic data “point to the appendix as a site of origin for Parkinson’s and provide a path forward for devising new treatment strategies,” reported senior author Viviane Labrie, PhD, of the Van Andel Research Institute (VARI) in Grand Rapids, Mich.

The epidemiologic data was the most recent step in a series of findings summarized in a newly published paper in Science Translational Medicine. As the researchers explained, it is relevant to a separate body of evidence that alpha-synuclein, a protein that serves as the hallmark of PD when it appears in Lewy bodies, can be isolated in the nerve fibers and nerve cells of the appendix.

“We have shown that alpha-synuclein proteins, including the truncated forms observed in Lewy bodies, are abundant in the appendix,” reported first author Bryan A. Killinger, PhD, also at VARI, in a press teleconference. He said this finding is likely to explain the reduced risk of PD from appendectomy.

In the largest of the epidemiologic studies, the effect of appendectomy on subsequent risk of PD was evaluated through the health records from more than 1.6 million individuals in Sweden. The incidence of PD was found to be 19.3% lower among 551,647 patients who had an appendectomy, compared with controls.

In addition, the data showed that when PD did occur after appendectomy, it was delayed on average by 3.6 years. It is notable that appendectomy was not associated with protection from PD in patients with a familial link to PD, a group they said comprises less than 10% of cases.

In patients with PD, nonmotor symptoms often include GI tract dysfunction, which can, in some cases, be part of a prodromal presentation that precedes the onset of classical PD symptoms by several years, the authors reported. However, the new research upends previous conceptions of disease. The demonstration of abundant alpha-synuclein in the appendix coupled with the protective effect of appendectomy, suggests that PD may originate in the GI tract and then spread to the central nervous system (CNS) rather than the other way around.

“The vermiform appendix was once considered to be an unnecessary organ. Although there is now good evidence that the appendix plays a major role in the regulation of the immune system, including the regulation of gut bacteria, our work suggests it is also mediates risk of Parkinson’s,” Dr. Labrie said in the teleconference.

In the paper, numerous pieces of the puzzle are brought together to suggest that alpha-synuclein in the appendix is linked to alpha-synuclein in the CNS. Many of the findings along this investigative pathway were described as surprising. For example, immunohistochemistry studies revealed high amounts of alpha-synuclein in nearly every sample of appendiceal tissue examined, including normal and inflamed tissue, tissue from individuals with PD and those without, and tissues from young and old individuals.

“The normal tissue, as well as appendiceal tissue from PD patients, contained high levels of alpha-synuclein in the truncated forms analogous to those seen in Lewy body pathology,” Dr. Killinger said. Based on these and other findings, he believes that alpha-synuclein in the appendix forms a reservoir for seeding the aggregates involved in the pathology of PD, although he acknowledged that it is not yet clear how the proteins in the appendix find their way to the brain.

From these data, it appears that most individuals with an intact appendix have alpha-synuclein in the nerve fibers, but Dr. Labrie pointed out that the only about 1% of the population develops PD. She speculated that there is “some confluence of events,” such as an environmental trigger altering the GI microbiome, that mediates ultimate risk of PD, but she noted that these events may take place decades before signs and symptoms of PD develop. The data appear to be a substantial reorientation in understanding PD.

“We have shown that the appendix is a hub for the accumulation of clumped forms of alpha-synuclein proteins, which are implicated in Parkinson’s,” Dr. Killinger said. “This knowledge will be invaluable as we explore new prevention and treatment strategies.”

The research was funded by a variety of governmental and private grants to individual authors. Dr. Killinger and Dr. Labrie report no financial relationships relevant to this study.

SOURCE: Killinger BA et al. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10:eaar5380.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: A 19.3% reduction in risk of PD from appendectomy may relate to alpha-synuclein in the appendix.

Study details: Series of related epidemiologic and translational studies.

Disclosures: The research was funded by a variety of governmental and private grants to individual authors. Dr. Killinger and Dr. Labrie report no financial relationships relevant to this study.

Source: Killinger BA et al. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10:eaar5380.

Parkinson’s prevalence varies significantly from state to state

ATLANTA – The prevalence of Parkinson’s disease and associated health care spending on the condition vary significantly from state to state, an analysis of Medicare data showed.

“There is a big variation in not only the prevalence of Parkinson’s disease but also in spending and in health care utilization” among Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with the condition, lead study author Michelle E. Fullard, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association. “As neurologists, we should be aware of this. We can use this information to identify and target areas in which Parkinson’s patients may have increased need and require more resources. It can also inform planning at the state and federal levels.”

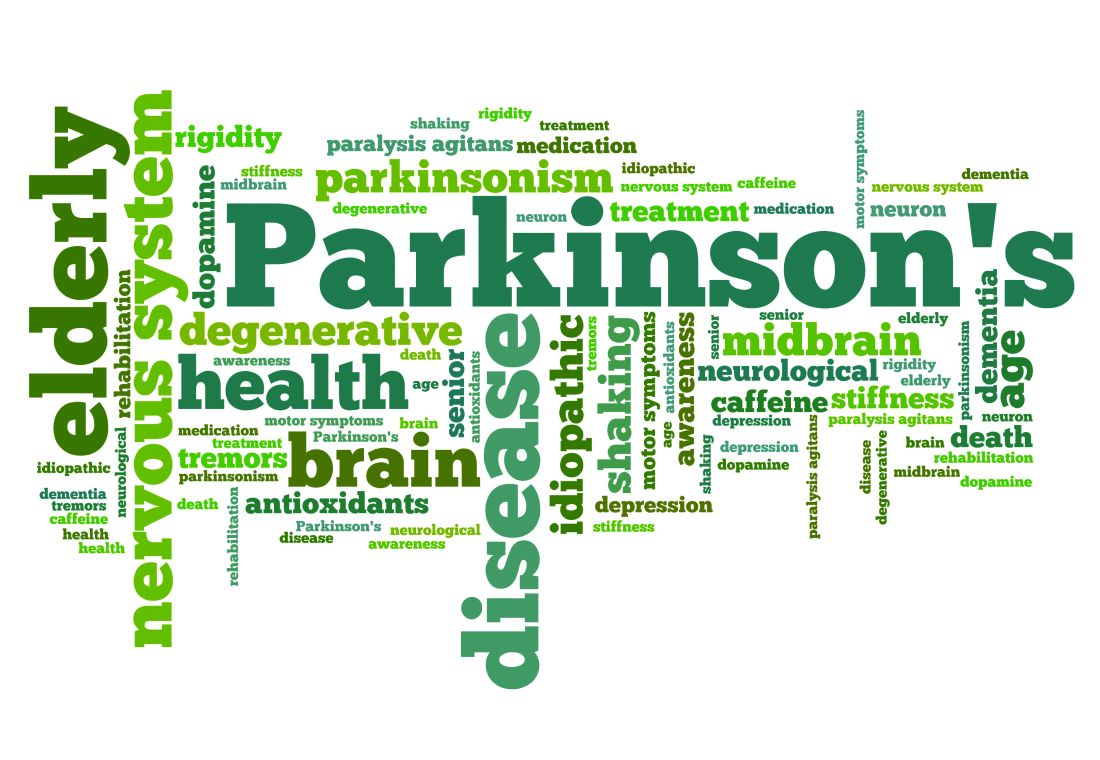

Dr. Fullard, formerly of the department of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and her colleagues evaluated data from Medicare Beneficiary Summary and Medicare Carrier Files for 27,538,023 individuals aged 65 years and older who were continuously enrolled in Medicare parts A and B during 2014. They calculated state-level differences in Parkinson’s disease prevalence, demographic and eligibility characteristics, costs, and health care use, including number of emergency room visits, number of outpatient clinic visits, and inpatient hospitalizations. The researchers used reimbursement data to calculate the mean out-of-pocket and Medicare cost per individual in each state, and compared direct costs and health service utilization for individuals with and without Parkinson’s disease.

Of all Medicare beneficiaries studied, 392,214 (1.42%) had a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Nearly half (46%) were women and 26% were aged 85 years and older. States with the highest prevalence of Parkinson’s disease included New York (1,720/100,000), Illinois (1,566/100,000), Connecticut (1,560/100,000), Florida (1,551/100,000), Pennsylvania (1,549/100,000), Rhode Island (1,543/100,000), New Jersey (1,541/100,000), Texas (1,522/100,000), California (1,520/100,000) and Louisiana (1,519/100,000). Minnesota had the lowest prevalence (803/100,000).

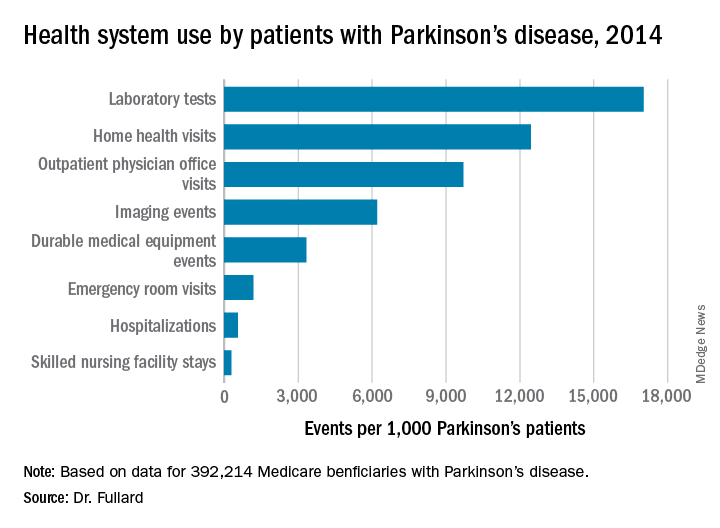

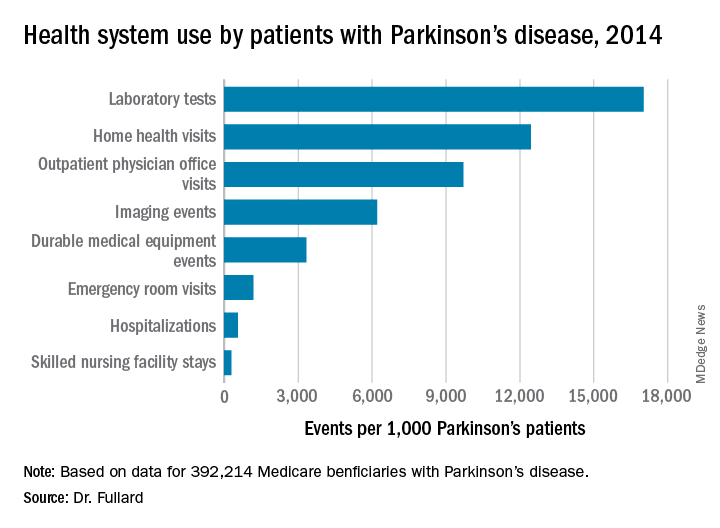

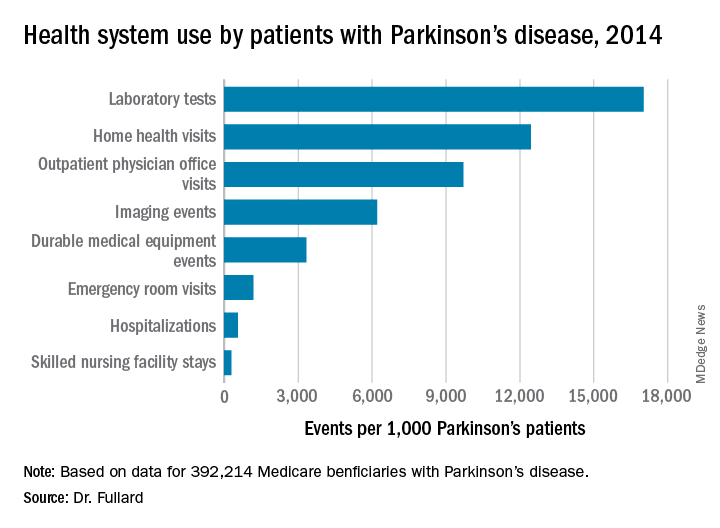

Among the national sample of patients with Parkinson’s disease, there were 219,049 hospitalizations (which represented 558/1,000 Parkinson’s patients), 37,839 readmissions (172/1,000 hospitalizations), 9,740,609 outpatient physician office visits (9,700/1,000 patients), 34,159 hospice stays (87/1,000 patients), 113,027 skilled nursing facility stays (288/1,000 patients), 466,160 emergency room visits (1,188/1,000 patients, 39% of which resulted in hospital admission). In addition, there were 1,308,934 durable medical equipment events (3,337/1,000 patients), 6,676,119 laboratory tests (17,021/1,000 patients), 2,435,654 imaging events (6,210/1,000 patients), and 4,879,538 home health visits (12,441/1,000 patients). The costliest services were inpatient care ($2.1 billion), skilled nursing facility care ($1.4 billion), prescription drugs used by those with prescription coverage ($974.8 million), hospital outpatient care ($881 million), and home health care ($776.5 million).

“States with a higher prevalence of Parkinson’s disease may have a larger proportion of high-risk factor patient groups, a higher concentration of providers who recognize and document Parkinson’s disease, increased public awareness of symptoms, or increased health care–seeking behaviors among people living in the state,” the researchers wrote in their abstract. “Among our top Parkinson’s disease prevalence states, Florida and New York also rank high in terms of absolute number of Medicare beneficiaries and have large supplies of health care providers.”

They also noted that Medicare beneficiaries with Parkinson’s had increased use of health care and spending, compared with their counterparts without the disease. “This was true across all sectors of care (inpatient, outpatient, skilled nursing, and ancillary services) and is in line with data demonstrating that PD, its complications, and the shift away from comorbid disease care and prevention that occurs after a Parkinson’s disease diagnosis drive health care spending and utilization among these individuals,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the Parkinson’s Foundation. Dr. Fullard, who now holds a faculty position at the University of Colorado, Aurora, reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Ann Neurol. 2018;84[S22]:S89-90, Abstract S215.

ATLANTA – The prevalence of Parkinson’s disease and associated health care spending on the condition vary significantly from state to state, an analysis of Medicare data showed.

“There is a big variation in not only the prevalence of Parkinson’s disease but also in spending and in health care utilization” among Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with the condition, lead study author Michelle E. Fullard, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association. “As neurologists, we should be aware of this. We can use this information to identify and target areas in which Parkinson’s patients may have increased need and require more resources. It can also inform planning at the state and federal levels.”

Dr. Fullard, formerly of the department of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and her colleagues evaluated data from Medicare Beneficiary Summary and Medicare Carrier Files for 27,538,023 individuals aged 65 years and older who were continuously enrolled in Medicare parts A and B during 2014. They calculated state-level differences in Parkinson’s disease prevalence, demographic and eligibility characteristics, costs, and health care use, including number of emergency room visits, number of outpatient clinic visits, and inpatient hospitalizations. The researchers used reimbursement data to calculate the mean out-of-pocket and Medicare cost per individual in each state, and compared direct costs and health service utilization for individuals with and without Parkinson’s disease.

Of all Medicare beneficiaries studied, 392,214 (1.42%) had a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Nearly half (46%) were women and 26% were aged 85 years and older. States with the highest prevalence of Parkinson’s disease included New York (1,720/100,000), Illinois (1,566/100,000), Connecticut (1,560/100,000), Florida (1,551/100,000), Pennsylvania (1,549/100,000), Rhode Island (1,543/100,000), New Jersey (1,541/100,000), Texas (1,522/100,000), California (1,520/100,000) and Louisiana (1,519/100,000). Minnesota had the lowest prevalence (803/100,000).

Among the national sample of patients with Parkinson’s disease, there were 219,049 hospitalizations (which represented 558/1,000 Parkinson’s patients), 37,839 readmissions (172/1,000 hospitalizations), 9,740,609 outpatient physician office visits (9,700/1,000 patients), 34,159 hospice stays (87/1,000 patients), 113,027 skilled nursing facility stays (288/1,000 patients), 466,160 emergency room visits (1,188/1,000 patients, 39% of which resulted in hospital admission). In addition, there were 1,308,934 durable medical equipment events (3,337/1,000 patients), 6,676,119 laboratory tests (17,021/1,000 patients), 2,435,654 imaging events (6,210/1,000 patients), and 4,879,538 home health visits (12,441/1,000 patients). The costliest services were inpatient care ($2.1 billion), skilled nursing facility care ($1.4 billion), prescription drugs used by those with prescription coverage ($974.8 million), hospital outpatient care ($881 million), and home health care ($776.5 million).

“States with a higher prevalence of Parkinson’s disease may have a larger proportion of high-risk factor patient groups, a higher concentration of providers who recognize and document Parkinson’s disease, increased public awareness of symptoms, or increased health care–seeking behaviors among people living in the state,” the researchers wrote in their abstract. “Among our top Parkinson’s disease prevalence states, Florida and New York also rank high in terms of absolute number of Medicare beneficiaries and have large supplies of health care providers.”

They also noted that Medicare beneficiaries with Parkinson’s had increased use of health care and spending, compared with their counterparts without the disease. “This was true across all sectors of care (inpatient, outpatient, skilled nursing, and ancillary services) and is in line with data demonstrating that PD, its complications, and the shift away from comorbid disease care and prevention that occurs after a Parkinson’s disease diagnosis drive health care spending and utilization among these individuals,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the Parkinson’s Foundation. Dr. Fullard, who now holds a faculty position at the University of Colorado, Aurora, reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Ann Neurol. 2018;84[S22]:S89-90, Abstract S215.

ATLANTA – The prevalence of Parkinson’s disease and associated health care spending on the condition vary significantly from state to state, an analysis of Medicare data showed.

“There is a big variation in not only the prevalence of Parkinson’s disease but also in spending and in health care utilization” among Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with the condition, lead study author Michelle E. Fullard, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association. “As neurologists, we should be aware of this. We can use this information to identify and target areas in which Parkinson’s patients may have increased need and require more resources. It can also inform planning at the state and federal levels.”

Dr. Fullard, formerly of the department of neurology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and her colleagues evaluated data from Medicare Beneficiary Summary and Medicare Carrier Files for 27,538,023 individuals aged 65 years and older who were continuously enrolled in Medicare parts A and B during 2014. They calculated state-level differences in Parkinson’s disease prevalence, demographic and eligibility characteristics, costs, and health care use, including number of emergency room visits, number of outpatient clinic visits, and inpatient hospitalizations. The researchers used reimbursement data to calculate the mean out-of-pocket and Medicare cost per individual in each state, and compared direct costs and health service utilization for individuals with and without Parkinson’s disease.

Of all Medicare beneficiaries studied, 392,214 (1.42%) had a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Nearly half (46%) were women and 26% were aged 85 years and older. States with the highest prevalence of Parkinson’s disease included New York (1,720/100,000), Illinois (1,566/100,000), Connecticut (1,560/100,000), Florida (1,551/100,000), Pennsylvania (1,549/100,000), Rhode Island (1,543/100,000), New Jersey (1,541/100,000), Texas (1,522/100,000), California (1,520/100,000) and Louisiana (1,519/100,000). Minnesota had the lowest prevalence (803/100,000).

Among the national sample of patients with Parkinson’s disease, there were 219,049 hospitalizations (which represented 558/1,000 Parkinson’s patients), 37,839 readmissions (172/1,000 hospitalizations), 9,740,609 outpatient physician office visits (9,700/1,000 patients), 34,159 hospice stays (87/1,000 patients), 113,027 skilled nursing facility stays (288/1,000 patients), 466,160 emergency room visits (1,188/1,000 patients, 39% of which resulted in hospital admission). In addition, there were 1,308,934 durable medical equipment events (3,337/1,000 patients), 6,676,119 laboratory tests (17,021/1,000 patients), 2,435,654 imaging events (6,210/1,000 patients), and 4,879,538 home health visits (12,441/1,000 patients). The costliest services were inpatient care ($2.1 billion), skilled nursing facility care ($1.4 billion), prescription drugs used by those with prescription coverage ($974.8 million), hospital outpatient care ($881 million), and home health care ($776.5 million).

“States with a higher prevalence of Parkinson’s disease may have a larger proportion of high-risk factor patient groups, a higher concentration of providers who recognize and document Parkinson’s disease, increased public awareness of symptoms, or increased health care–seeking behaviors among people living in the state,” the researchers wrote in their abstract. “Among our top Parkinson’s disease prevalence states, Florida and New York also rank high in terms of absolute number of Medicare beneficiaries and have large supplies of health care providers.”

They also noted that Medicare beneficiaries with Parkinson’s had increased use of health care and spending, compared with their counterparts without the disease. “This was true across all sectors of care (inpatient, outpatient, skilled nursing, and ancillary services) and is in line with data demonstrating that PD, its complications, and the shift away from comorbid disease care and prevention that occurs after a Parkinson’s disease diagnosis drive health care spending and utilization among these individuals,” they wrote.

The study was supported by the Parkinson’s Foundation. Dr. Fullard, who now holds a faculty position at the University of Colorado, Aurora, reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Ann Neurol. 2018;84[S22]:S89-90, Abstract S215.

REPORTING FROM ANA 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: States with the highest prevalence of Parkinson’s disease included New York (1,720/100,000), Illinois (1,566/100,000), and Connecticut (1,560/100,000), while Minnesota had the lowest prevalence (803/100,000).

Study details: An analysis of 392,214 Medicare beneficiaries who carried a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Parkinson’s Foundation. Dr. Fullard reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Ann Neurol. 2018;84[S22]:S89-90. Abstract S215.

Can boxing training improve Parkinson reaction times?

NEW YORK – A small pilot study has shown that patients with Parkinson’s disease who participated in the Rock Steady Boxing non-contact training program may have faster reaction times than PD patients who did not participate in the program, according to a poster presented at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

“The novelty of this is that it shows how Rock Steady Boxing and exercise programs that use sequences and the learning of sequences could possibly help slow the decline, or maintain a level of functioning longer, in Parkinson’s disease,” said Christopher McLeod, a second-year medical student at New York Institute of Technology (NYIT) College of Osteopathic Medicine, Old Westbury, N.Y.

Rock Steady Boxing is a non-contact program tailored to Parkinson’s patients founded in 2006 by Scott Newman, an Indiana lawyer who was diagnosed with early onset Parkinson’s at age 40. The regimen involves intense one-on-one training centered around boxing. Rock Steady Boxing offers classes from coast to coast in the United States and in 13 other countries. Mr. McLeod is a volunteer at the NYIT chapter of Rock Steady Boxing in Old Westbury, N.Y.

Mr. McLeod studied 28 PD patients – 14 who had been taking Rock Steady Boxing classes at NYIT for at least 6 months and 14 controls. The goal of the study was to evaluate if the Rock Steady Boxing participants showed any improvement in procedural motor learning. His coauthor was Adena Leder, DO, a faculty neurologist and movement disorder specialist at NYIT,

“What’s new about this research is the procedural memory component and the Rock Steady Boxing program is just more of the vessel, so to speak,” Mr. McLeod said. “This is a pilot study. We wanted to see if Rock Steady Boxing would show benefits in these patients. There are some trends in my research that [indicate] it would; it did not have statistical significance, but we did see trend lines.”

The researchers used a modified Serial Reaction Time Test (SRTT) composed of seven blocks of 10 stimuli each with 30-second breaks between blocks. Blocks consisted of a random familiarization block, four learning blocks repeating the same sequence of stimuli, a transfer block of random stimuli, and a posttransfer block presenting the same sequence of stimuli from the four learning blocks.

They assessed procedural learning by comparing the reduction in response time over the four identical learning blocks as well as by comparing changes in response time when the subjects were subsequently exposed to the random transfer block.

Experienced boxers demonstrated faster reaction time over the four learning blocks, ranging from 795.32 vs. 906.89 ms in the first learning block to 674.79 vs. 787.32 ms in the fourth learning block (P = .19). In the random sequence transfer block, controls showed a 93.5-ms decrease in median reaction time vs. a 27.3-ms increase in reaction time of experienced boxers. One possible explanation the investigators noted is that the controls simply got better at reading the stimuli over time without actually learning the repeated sequence.

Mr. McLeod noted that a typical Rock Steady Boxing session starts with a warmup and stretch, then learning the boxing stance with the nondominant foot back, shoulders over the body and the head over the feet. The boxing moves involve sequences of different punching combinations — jab, jab, cross; left, left, right; jab, cross, hook. Then the class divides into separate circuits for boxing and exercise. The boxing circuit involves punching the speed bag – the small, air-filled, pear-shaped bag attached to a hook at eye level – as well as heavy bag and partner-held focus mitts, all with the aim of reinforcing the learned sequences. The exercise circuit focuses on muscle training and exercise with the goal of improving balance and gait.

“The boxing sequences help not only with cognitive ability but motor control,” Mr. McLeod said. “The program also helps with some of the nonmotor aspects of Parkinson’s disease. Depression is almost synonymous with Parkinson’s disease; this brings people together and builds camaraderie.”

Mr. McLeod said he hopes the research continues. “I’m hoping that this can be a jumping-off point for research going forward with procedural memory, Parkinson’s, and Rock Steady Boxing or programs like it,” he said. Future research should involve more subjects, measure improvement within same subjects who participate in the program, and account for variables such as age and gender.

Mr. McLeod and Dr. Leder reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW YORK – A small pilot study has shown that patients with Parkinson’s disease who participated in the Rock Steady Boxing non-contact training program may have faster reaction times than PD patients who did not participate in the program, according to a poster presented at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

“The novelty of this is that it shows how Rock Steady Boxing and exercise programs that use sequences and the learning of sequences could possibly help slow the decline, or maintain a level of functioning longer, in Parkinson’s disease,” said Christopher McLeod, a second-year medical student at New York Institute of Technology (NYIT) College of Osteopathic Medicine, Old Westbury, N.Y.

Rock Steady Boxing is a non-contact program tailored to Parkinson’s patients founded in 2006 by Scott Newman, an Indiana lawyer who was diagnosed with early onset Parkinson’s at age 40. The regimen involves intense one-on-one training centered around boxing. Rock Steady Boxing offers classes from coast to coast in the United States and in 13 other countries. Mr. McLeod is a volunteer at the NYIT chapter of Rock Steady Boxing in Old Westbury, N.Y.

Mr. McLeod studied 28 PD patients – 14 who had been taking Rock Steady Boxing classes at NYIT for at least 6 months and 14 controls. The goal of the study was to evaluate if the Rock Steady Boxing participants showed any improvement in procedural motor learning. His coauthor was Adena Leder, DO, a faculty neurologist and movement disorder specialist at NYIT,

“What’s new about this research is the procedural memory component and the Rock Steady Boxing program is just more of the vessel, so to speak,” Mr. McLeod said. “This is a pilot study. We wanted to see if Rock Steady Boxing would show benefits in these patients. There are some trends in my research that [indicate] it would; it did not have statistical significance, but we did see trend lines.”

The researchers used a modified Serial Reaction Time Test (SRTT) composed of seven blocks of 10 stimuli each with 30-second breaks between blocks. Blocks consisted of a random familiarization block, four learning blocks repeating the same sequence of stimuli, a transfer block of random stimuli, and a posttransfer block presenting the same sequence of stimuli from the four learning blocks.

They assessed procedural learning by comparing the reduction in response time over the four identical learning blocks as well as by comparing changes in response time when the subjects were subsequently exposed to the random transfer block.

Experienced boxers demonstrated faster reaction time over the four learning blocks, ranging from 795.32 vs. 906.89 ms in the first learning block to 674.79 vs. 787.32 ms in the fourth learning block (P = .19). In the random sequence transfer block, controls showed a 93.5-ms decrease in median reaction time vs. a 27.3-ms increase in reaction time of experienced boxers. One possible explanation the investigators noted is that the controls simply got better at reading the stimuli over time without actually learning the repeated sequence.

Mr. McLeod noted that a typical Rock Steady Boxing session starts with a warmup and stretch, then learning the boxing stance with the nondominant foot back, shoulders over the body and the head over the feet. The boxing moves involve sequences of different punching combinations — jab, jab, cross; left, left, right; jab, cross, hook. Then the class divides into separate circuits for boxing and exercise. The boxing circuit involves punching the speed bag – the small, air-filled, pear-shaped bag attached to a hook at eye level – as well as heavy bag and partner-held focus mitts, all with the aim of reinforcing the learned sequences. The exercise circuit focuses on muscle training and exercise with the goal of improving balance and gait.

“The boxing sequences help not only with cognitive ability but motor control,” Mr. McLeod said. “The program also helps with some of the nonmotor aspects of Parkinson’s disease. Depression is almost synonymous with Parkinson’s disease; this brings people together and builds camaraderie.”

Mr. McLeod said he hopes the research continues. “I’m hoping that this can be a jumping-off point for research going forward with procedural memory, Parkinson’s, and Rock Steady Boxing or programs like it,” he said. Future research should involve more subjects, measure improvement within same subjects who participate in the program, and account for variables such as age and gender.

Mr. McLeod and Dr. Leder reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW YORK – A small pilot study has shown that patients with Parkinson’s disease who participated in the Rock Steady Boxing non-contact training program may have faster reaction times than PD patients who did not participate in the program, according to a poster presented at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

“The novelty of this is that it shows how Rock Steady Boxing and exercise programs that use sequences and the learning of sequences could possibly help slow the decline, or maintain a level of functioning longer, in Parkinson’s disease,” said Christopher McLeod, a second-year medical student at New York Institute of Technology (NYIT) College of Osteopathic Medicine, Old Westbury, N.Y.

Rock Steady Boxing is a non-contact program tailored to Parkinson’s patients founded in 2006 by Scott Newman, an Indiana lawyer who was diagnosed with early onset Parkinson’s at age 40. The regimen involves intense one-on-one training centered around boxing. Rock Steady Boxing offers classes from coast to coast in the United States and in 13 other countries. Mr. McLeod is a volunteer at the NYIT chapter of Rock Steady Boxing in Old Westbury, N.Y.

Mr. McLeod studied 28 PD patients – 14 who had been taking Rock Steady Boxing classes at NYIT for at least 6 months and 14 controls. The goal of the study was to evaluate if the Rock Steady Boxing participants showed any improvement in procedural motor learning. His coauthor was Adena Leder, DO, a faculty neurologist and movement disorder specialist at NYIT,

“What’s new about this research is the procedural memory component and the Rock Steady Boxing program is just more of the vessel, so to speak,” Mr. McLeod said. “This is a pilot study. We wanted to see if Rock Steady Boxing would show benefits in these patients. There are some trends in my research that [indicate] it would; it did not have statistical significance, but we did see trend lines.”

The researchers used a modified Serial Reaction Time Test (SRTT) composed of seven blocks of 10 stimuli each with 30-second breaks between blocks. Blocks consisted of a random familiarization block, four learning blocks repeating the same sequence of stimuli, a transfer block of random stimuli, and a posttransfer block presenting the same sequence of stimuli from the four learning blocks.

They assessed procedural learning by comparing the reduction in response time over the four identical learning blocks as well as by comparing changes in response time when the subjects were subsequently exposed to the random transfer block.

Experienced boxers demonstrated faster reaction time over the four learning blocks, ranging from 795.32 vs. 906.89 ms in the first learning block to 674.79 vs. 787.32 ms in the fourth learning block (P = .19). In the random sequence transfer block, controls showed a 93.5-ms decrease in median reaction time vs. a 27.3-ms increase in reaction time of experienced boxers. One possible explanation the investigators noted is that the controls simply got better at reading the stimuli over time without actually learning the repeated sequence.

Mr. McLeod noted that a typical Rock Steady Boxing session starts with a warmup and stretch, then learning the boxing stance with the nondominant foot back, shoulders over the body and the head over the feet. The boxing moves involve sequences of different punching combinations — jab, jab, cross; left, left, right; jab, cross, hook. Then the class divides into separate circuits for boxing and exercise. The boxing circuit involves punching the speed bag – the small, air-filled, pear-shaped bag attached to a hook at eye level – as well as heavy bag and partner-held focus mitts, all with the aim of reinforcing the learned sequences. The exercise circuit focuses on muscle training and exercise with the goal of improving balance and gait.

“The boxing sequences help not only with cognitive ability but motor control,” Mr. McLeod said. “The program also helps with some of the nonmotor aspects of Parkinson’s disease. Depression is almost synonymous with Parkinson’s disease; this brings people together and builds camaraderie.”

Mr. McLeod said he hopes the research continues. “I’m hoping that this can be a jumping-off point for research going forward with procedural memory, Parkinson’s, and Rock Steady Boxing or programs like it,” he said. Future research should involve more subjects, measure improvement within same subjects who participate in the program, and account for variables such as age and gender.

Mr. McLeod and Dr. Leder reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM ICPDMD 2018

Key clinical point: Exercise programs may help improve procedural learning in individuals with Parkinson’s disease.

Major finding: Rock Steady Boxing experienced boxers demonstrated reaction times ranging from 795.32 vs. 906.89 ms to 674.79 vs. 787.32 ms across four test blocks.

Study details: Pilot study of 14 Parkinson’s patients who participated in Rock Steady Boxing vs. 14 controls.

Disclosures: Mr. McLeod reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Investigational gene therapy for medically refractory Parkinson’s shows promise

ATLANTA – VY-AADC01, an investigational gene therapy for individuals with medically refractory Parkinson’s disease being developed by Voyager Therapeutics, was well tolerated and decreased the need for antiparkinsonian medications, results from an ongoing phase 1b study showed.

“Prior phase 1 trials also introduced the aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) gene using an adeno-associated virus serotype-2 (AAV2) vector into the putamen of people with Parkinson’s disease (PD),” lead study author Chad Christine, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association. “Unlike the previous trials, here we increased both vector genome concentration and volume of the AAV2-AADC vector (VY-AADC01) across cohorts and used intraoperative MRI guidance to administer the gene product.”

According to Dr. Christine, a neurologist at the University of California, San Francisco, Parkinson’s Disease Clinic and Research Center, prior trials showed that AAV2-AADC was safe, but there was limited clinical efficacy. This may have been because of the limited volume of putamen treated with the gene therapy. “In our current trial, we admixed VY-AADC01 with gadoteridol (ProHance), an MR imaging agent, which allowed both near real-time MRI monitoring of the location and volume of product infused and postsurgical assessment of the area of the putamen covered by VY-AADC01,” he said. “In addition, we used 18F-Dopa PET, which allowed us to assess the activity of the AADC enzyme in the putamen.”

The researchers enrolled three cohorts of patients who received bilateral infusions of VY-AADC01, admixed with gadoteridol to facilitate intraoperative MRI monitoring of the infusions. In cohort 1, five patients received up to 450 μL/putamen at a concentration of 8.3 × 1011 vg (viral genomes)/mL and were followed for 36 months. In cohort 2, five patients received up to 900 μL/putamen at 8.3 × 1011 vg/mL and were followed for 18 months. In cohort 3, five patients received up to 900 μL/putamen at 2.6 × 1012 vg/mL and were followed for 12 months.

At 12 months, Dr. Christine and his associates observed mean levodopa-equivalent dose (LED) reductions of –10.2%, –32.8%, and –39.3% in cohort 1, cohort 2, and cohort 3, respectively; LED reductions were sustained to 18 months in cohorts 1 and 2. “We were impressed by how well the decrease in need for antiparkinsonian medications paralleled the AADC activity we measured in the putamen of our subjects, which is consistent with the proposed mechanism of action of VY-AADC01,” he said.

In addition, subjects in cohort 1 showed a mean 2.3-hour improvement in Parkinson’s diary-“on” time without troublesome dyskinesia at 24 months, which was maintained at 36 months, while subjects in cohort 2 showed a clinically meaningful 3.5-hour improvement at 18 months. Subjects in cohort 3 showed somewhat less improvement than the other cohorts (1.5 hours at 12 months), but they also had more severe baseline dyskinesia on the Unified Dyskinesia Rating Scale (a mean of 30.2 vs. 19.2 and 17.4 in cohorts 1 and 2, respectively). One patient in the trial experienced two surgery-related serious adverse events (pulmonary embolism and related heart arrhythmia) which resolved completely.

“I think we were somewhat surprised by some of the challenges of the surgical administration,” Dr. Christine said. “Our surgeons improved the administration technique throughout the trial and made a major transition from administering VY-AADC01 using a frontal approach to the putamen to using a posterior approach in our second phase 1 trial.”

He concluded that findings of the current trial suggest that AAV2-AADC gene therapy, administered using intraoperative MRI guidance, appears to be safe and well tolerated. “A number of outcomes suggest that it may offer clinical benefit to patients with advancing Parkinson’s disease, but this will have to be tested in a randomized trial which has recently started,” he said.

Dr. Christine acknowledged that the small sample size and the open-label design of the study limits the generalizability of the findings. The trial received support from Voyager Therapeutics and the Michael J. Fox Foundation. Dr. Christine reported having no disclosures.

Source: Christine et al. ANA 2018, Abstract M300.

ATLANTA – VY-AADC01, an investigational gene therapy for individuals with medically refractory Parkinson’s disease being developed by Voyager Therapeutics, was well tolerated and decreased the need for antiparkinsonian medications, results from an ongoing phase 1b study showed.

“Prior phase 1 trials also introduced the aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) gene using an adeno-associated virus serotype-2 (AAV2) vector into the putamen of people with Parkinson’s disease (PD),” lead study author Chad Christine, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association. “Unlike the previous trials, here we increased both vector genome concentration and volume of the AAV2-AADC vector (VY-AADC01) across cohorts and used intraoperative MRI guidance to administer the gene product.”

According to Dr. Christine, a neurologist at the University of California, San Francisco, Parkinson’s Disease Clinic and Research Center, prior trials showed that AAV2-AADC was safe, but there was limited clinical efficacy. This may have been because of the limited volume of putamen treated with the gene therapy. “In our current trial, we admixed VY-AADC01 with gadoteridol (ProHance), an MR imaging agent, which allowed both near real-time MRI monitoring of the location and volume of product infused and postsurgical assessment of the area of the putamen covered by VY-AADC01,” he said. “In addition, we used 18F-Dopa PET, which allowed us to assess the activity of the AADC enzyme in the putamen.”

The researchers enrolled three cohorts of patients who received bilateral infusions of VY-AADC01, admixed with gadoteridol to facilitate intraoperative MRI monitoring of the infusions. In cohort 1, five patients received up to 450 μL/putamen at a concentration of 8.3 × 1011 vg (viral genomes)/mL and were followed for 36 months. In cohort 2, five patients received up to 900 μL/putamen at 8.3 × 1011 vg/mL and were followed for 18 months. In cohort 3, five patients received up to 900 μL/putamen at 2.6 × 1012 vg/mL and were followed for 12 months.

At 12 months, Dr. Christine and his associates observed mean levodopa-equivalent dose (LED) reductions of –10.2%, –32.8%, and –39.3% in cohort 1, cohort 2, and cohort 3, respectively; LED reductions were sustained to 18 months in cohorts 1 and 2. “We were impressed by how well the decrease in need for antiparkinsonian medications paralleled the AADC activity we measured in the putamen of our subjects, which is consistent with the proposed mechanism of action of VY-AADC01,” he said.

In addition, subjects in cohort 1 showed a mean 2.3-hour improvement in Parkinson’s diary-“on” time without troublesome dyskinesia at 24 months, which was maintained at 36 months, while subjects in cohort 2 showed a clinically meaningful 3.5-hour improvement at 18 months. Subjects in cohort 3 showed somewhat less improvement than the other cohorts (1.5 hours at 12 months), but they also had more severe baseline dyskinesia on the Unified Dyskinesia Rating Scale (a mean of 30.2 vs. 19.2 and 17.4 in cohorts 1 and 2, respectively). One patient in the trial experienced two surgery-related serious adverse events (pulmonary embolism and related heart arrhythmia) which resolved completely.

“I think we were somewhat surprised by some of the challenges of the surgical administration,” Dr. Christine said. “Our surgeons improved the administration technique throughout the trial and made a major transition from administering VY-AADC01 using a frontal approach to the putamen to using a posterior approach in our second phase 1 trial.”

He concluded that findings of the current trial suggest that AAV2-AADC gene therapy, administered using intraoperative MRI guidance, appears to be safe and well tolerated. “A number of outcomes suggest that it may offer clinical benefit to patients with advancing Parkinson’s disease, but this will have to be tested in a randomized trial which has recently started,” he said.

Dr. Christine acknowledged that the small sample size and the open-label design of the study limits the generalizability of the findings. The trial received support from Voyager Therapeutics and the Michael J. Fox Foundation. Dr. Christine reported having no disclosures.

Source: Christine et al. ANA 2018, Abstract M300.

ATLANTA – VY-AADC01, an investigational gene therapy for individuals with medically refractory Parkinson’s disease being developed by Voyager Therapeutics, was well tolerated and decreased the need for antiparkinsonian medications, results from an ongoing phase 1b study showed.

“Prior phase 1 trials also introduced the aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) gene using an adeno-associated virus serotype-2 (AAV2) vector into the putamen of people with Parkinson’s disease (PD),” lead study author Chad Christine, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association. “Unlike the previous trials, here we increased both vector genome concentration and volume of the AAV2-AADC vector (VY-AADC01) across cohorts and used intraoperative MRI guidance to administer the gene product.”

According to Dr. Christine, a neurologist at the University of California, San Francisco, Parkinson’s Disease Clinic and Research Center, prior trials showed that AAV2-AADC was safe, but there was limited clinical efficacy. This may have been because of the limited volume of putamen treated with the gene therapy. “In our current trial, we admixed VY-AADC01 with gadoteridol (ProHance), an MR imaging agent, which allowed both near real-time MRI monitoring of the location and volume of product infused and postsurgical assessment of the area of the putamen covered by VY-AADC01,” he said. “In addition, we used 18F-Dopa PET, which allowed us to assess the activity of the AADC enzyme in the putamen.”

The researchers enrolled three cohorts of patients who received bilateral infusions of VY-AADC01, admixed with gadoteridol to facilitate intraoperative MRI monitoring of the infusions. In cohort 1, five patients received up to 450 μL/putamen at a concentration of 8.3 × 1011 vg (viral genomes)/mL and were followed for 36 months. In cohort 2, five patients received up to 900 μL/putamen at 8.3 × 1011 vg/mL and were followed for 18 months. In cohort 3, five patients received up to 900 μL/putamen at 2.6 × 1012 vg/mL and were followed for 12 months.

At 12 months, Dr. Christine and his associates observed mean levodopa-equivalent dose (LED) reductions of –10.2%, –32.8%, and –39.3% in cohort 1, cohort 2, and cohort 3, respectively; LED reductions were sustained to 18 months in cohorts 1 and 2. “We were impressed by how well the decrease in need for antiparkinsonian medications paralleled the AADC activity we measured in the putamen of our subjects, which is consistent with the proposed mechanism of action of VY-AADC01,” he said.

In addition, subjects in cohort 1 showed a mean 2.3-hour improvement in Parkinson’s diary-“on” time without troublesome dyskinesia at 24 months, which was maintained at 36 months, while subjects in cohort 2 showed a clinically meaningful 3.5-hour improvement at 18 months. Subjects in cohort 3 showed somewhat less improvement than the other cohorts (1.5 hours at 12 months), but they also had more severe baseline dyskinesia on the Unified Dyskinesia Rating Scale (a mean of 30.2 vs. 19.2 and 17.4 in cohorts 1 and 2, respectively). One patient in the trial experienced two surgery-related serious adverse events (pulmonary embolism and related heart arrhythmia) which resolved completely.

“I think we were somewhat surprised by some of the challenges of the surgical administration,” Dr. Christine said. “Our surgeons improved the administration technique throughout the trial and made a major transition from administering VY-AADC01 using a frontal approach to the putamen to using a posterior approach in our second phase 1 trial.”

He concluded that findings of the current trial suggest that AAV2-AADC gene therapy, administered using intraoperative MRI guidance, appears to be safe and well tolerated. “A number of outcomes suggest that it may offer clinical benefit to patients with advancing Parkinson’s disease, but this will have to be tested in a randomized trial which has recently started,” he said.

Dr. Christine acknowledged that the small sample size and the open-label design of the study limits the generalizability of the findings. The trial received support from Voyager Therapeutics and the Michael J. Fox Foundation. Dr. Christine reported having no disclosures.

Source: Christine et al. ANA 2018, Abstract M300.

REPORTING FROM ANA 2018

Key clinical point: AAV2-AADC gene therapy, administered using intraoperative MRI guidance, appears to be safe and well tolerated.

Major finding: At 12 months, the researchers observed mean levodopa-equivalent dose (LED) reductions of –10.2%, –32.8%, and –39.3% in cohort 1, cohort 2, and cohort 3, respectively.

Study details: A study of 15 patients in three cohorts who received bilateral infusions of VY-AADC01, admixed with gadoteridol to facilitate intraoperative MRI monitoring of the infusions.

Disclosures: The trial received support from Voyager Therapeutics and the Michael J. Fox Foundation. Dr. Christine reported having no disclosures.

Source: Christine et al. ANA 2018, Abstract M300.

Novel imaging may differentiate dementia in Parkinson’s

NEW YORK – Making the clinical diagnosis of dementia in Parkinson’s patients has been confounding because of the difficulty of differentiating it from dementia in Alzheimer’s disease, but researchers have developed a novel imaging technique, known as single-scan dynamic molecular imaging, which uses positron emission tomography to identify the key differentiating factor between the two types of dementia, as reported at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

“We have a technique with which we can detect neurotransmitters in the brain, particularly in patients with dementia,” said Rajendra D. Badgaiyan, PhD, professor of psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. “This is important to not only understand the type of dementia you’re dealing with but also to understand the underlying neurocognitive problem.”

The technique is called single-scan dynamic molecular imaging technique (SDMIT) and uses PET to detect and measure dopamine release activity in the brain during cognitive or behavioral functioning, he said. After patients are placed in the PET scanner, they receive an IV injection of the radio-labeled ligand fallypride. While in the PET scanner, patients are asked to perform a cognitive task, and PET measures the ligand concentration before and after the task in the dorsal striatum of the brain. The rate of ligand displacement before and after the task are compared to determine the levels of dopamine activity in the brain.

A significant dysregulation of dopaminergic neurotransmission would indicate a diagnosis of Parkinson’s dementia, while dysregulation of acetylcholine neurotransmission is characteristic of Alzheimer’s dementia, Dr. Badgaiyan said.

He described the experimentation that went into developing SDMIT, including its use in patients with ADHD and how the technique evolved from obtaining two PET scans to measure dopamine levels. His research also found that fallypride was the most effective ligand because it has a high affinity for the dopamine-2 receptor.

“The bottom line is that this technique can be used to study those conditions that are dopamine dependent” Dr. Badgaiyan said. “We can also use this technique to study the neurocognitive basis of the clinical symptoms in dementia and other cognitive deficits.”

SDMIT can also help to identify novel therapeutics targets for dementia, he said. “Today there is no medication that can reverse dementia; all the drugs that we use can only reduce the progression,” he said. “But this technique can help us identify which area of the brain should be targeted and what symptoms should be targeted to reverse dementia, treat dementia, or to cure dementia.”

Dr. Badgaiyan disclosed receiving funding for his research from the National Institutes of Mental Health, Department of Veterans Affairs, the Dana Foundation and Shriners Foundation.

NEW YORK – Making the clinical diagnosis of dementia in Parkinson’s patients has been confounding because of the difficulty of differentiating it from dementia in Alzheimer’s disease, but researchers have developed a novel imaging technique, known as single-scan dynamic molecular imaging, which uses positron emission tomography to identify the key differentiating factor between the two types of dementia, as reported at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

“We have a technique with which we can detect neurotransmitters in the brain, particularly in patients with dementia,” said Rajendra D. Badgaiyan, PhD, professor of psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. “This is important to not only understand the type of dementia you’re dealing with but also to understand the underlying neurocognitive problem.”

The technique is called single-scan dynamic molecular imaging technique (SDMIT) and uses PET to detect and measure dopamine release activity in the brain during cognitive or behavioral functioning, he said. After patients are placed in the PET scanner, they receive an IV injection of the radio-labeled ligand fallypride. While in the PET scanner, patients are asked to perform a cognitive task, and PET measures the ligand concentration before and after the task in the dorsal striatum of the brain. The rate of ligand displacement before and after the task are compared to determine the levels of dopamine activity in the brain.

A significant dysregulation of dopaminergic neurotransmission would indicate a diagnosis of Parkinson’s dementia, while dysregulation of acetylcholine neurotransmission is characteristic of Alzheimer’s dementia, Dr. Badgaiyan said.

He described the experimentation that went into developing SDMIT, including its use in patients with ADHD and how the technique evolved from obtaining two PET scans to measure dopamine levels. His research also found that fallypride was the most effective ligand because it has a high affinity for the dopamine-2 receptor.

“The bottom line is that this technique can be used to study those conditions that are dopamine dependent” Dr. Badgaiyan said. “We can also use this technique to study the neurocognitive basis of the clinical symptoms in dementia and other cognitive deficits.”

SDMIT can also help to identify novel therapeutics targets for dementia, he said. “Today there is no medication that can reverse dementia; all the drugs that we use can only reduce the progression,” he said. “But this technique can help us identify which area of the brain should be targeted and what symptoms should be targeted to reverse dementia, treat dementia, or to cure dementia.”

Dr. Badgaiyan disclosed receiving funding for his research from the National Institutes of Mental Health, Department of Veterans Affairs, the Dana Foundation and Shriners Foundation.

NEW YORK – Making the clinical diagnosis of dementia in Parkinson’s patients has been confounding because of the difficulty of differentiating it from dementia in Alzheimer’s disease, but researchers have developed a novel imaging technique, known as single-scan dynamic molecular imaging, which uses positron emission tomography to identify the key differentiating factor between the two types of dementia, as reported at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

“We have a technique with which we can detect neurotransmitters in the brain, particularly in patients with dementia,” said Rajendra D. Badgaiyan, PhD, professor of psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. “This is important to not only understand the type of dementia you’re dealing with but also to understand the underlying neurocognitive problem.”

The technique is called single-scan dynamic molecular imaging technique (SDMIT) and uses PET to detect and measure dopamine release activity in the brain during cognitive or behavioral functioning, he said. After patients are placed in the PET scanner, they receive an IV injection of the radio-labeled ligand fallypride. While in the PET scanner, patients are asked to perform a cognitive task, and PET measures the ligand concentration before and after the task in the dorsal striatum of the brain. The rate of ligand displacement before and after the task are compared to determine the levels of dopamine activity in the brain.

A significant dysregulation of dopaminergic neurotransmission would indicate a diagnosis of Parkinson’s dementia, while dysregulation of acetylcholine neurotransmission is characteristic of Alzheimer’s dementia, Dr. Badgaiyan said.

He described the experimentation that went into developing SDMIT, including its use in patients with ADHD and how the technique evolved from obtaining two PET scans to measure dopamine levels. His research also found that fallypride was the most effective ligand because it has a high affinity for the dopamine-2 receptor.

“The bottom line is that this technique can be used to study those conditions that are dopamine dependent” Dr. Badgaiyan said. “We can also use this technique to study the neurocognitive basis of the clinical symptoms in dementia and other cognitive deficits.”

SDMIT can also help to identify novel therapeutics targets for dementia, he said. “Today there is no medication that can reverse dementia; all the drugs that we use can only reduce the progression,” he said. “But this technique can help us identify which area of the brain should be targeted and what symptoms should be targeted to reverse dementia, treat dementia, or to cure dementia.”

Dr. Badgaiyan disclosed receiving funding for his research from the National Institutes of Mental Health, Department of Veterans Affairs, the Dana Foundation and Shriners Foundation.

REPORTING FROM ICPDMD 2018

Key clinical point: A novel neuroimaging technique can differential dementia in Parkinson’s from that in Alzheimer’s disease.

Major finding: PET has been shown to detect dopamine levels in human brains.

Study details: Ongoing research involving humans at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, N.Y.

Disclosures: Dr. Badgaiyan disclosed receiving funding for his research from the National Institutes of Mental Health, Department of Veterans Affairs, the Dana Foundation and Shriners Foundation.

Antiepileptic drug shows neuroprotection in Parkinson’s

NEW YORK – The loss of dopaminergic neurons is known to be a pivotal mechanism in Parkinson’s disease (PD), but early research into the anticonvulsant drug valproic acid has found it may produce antioxidant and neuroprotective actions that enhance the effects of levodopa, as reported at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

“Levodopa had better activity than valproic aside, but when they are used together, they have really very effective results,” said Ece Genç, PhD, of Yeditepe University in Istanbul, who reported on the research conducted in her laboratory.

Dr. Genç noted her research in rats has focused on the possible mechanisms of neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease: mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress and tissue damage, disruption in protein organization, and cell death caused by inflammatory changes. “Dopamine metabolism can itself be a toxic compound for the neurons,” she said, explaining that dopamine is critical for stabilizing nerve synapses, but its dysregulation can cause oxidative stress of the neurons, leading to cell death.

A key mechanism in the tremors PD patients experience is histone deacetylase, Dr. Genç said. “Histone acetylation and deacetylation are extremely important in these processes,” she said (Neurosci Lett. 2018 Feb 14;666:48-57). “Valproic acid is an antiepileptic drug; it is used in bipolar disorder and migraine complexes, but one of the major actions of valproic acid is that it caused histone deacetylase in the patients.”

Previous research that has shown the rotenone model of valproic acid provided neuroprotection helped drive her research, she said (Neurotox Res. 2010;17:130-41).

Future directions in her research would aim to synchronize cell cultures and in-vivo studies, and try to develop a method to measure alpha-synucleinopathy – abnormal levels of alpha-synuclein protein in the nerves of people with neurodegenerative diseases. “I think that alpha-synucleinopathy is the key word here,” Dr. Genç said. “We have to be very careful with alpha-synuclein proteins and their presence in individuals and, of course, with the successful use of valproic acid and histone deacetylase in patients, we can look for new drugs with less adverse effects.”

One of the drawbacks of valproic acid is that it affects so many different channels in the body. “We have to find some drugs with more targeted action.” Dr. Genç said.

Dr. Genç did not report any relevant disclosures.

NEW YORK – The loss of dopaminergic neurons is known to be a pivotal mechanism in Parkinson’s disease (PD), but early research into the anticonvulsant drug valproic acid has found it may produce antioxidant and neuroprotective actions that enhance the effects of levodopa, as reported at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

“Levodopa had better activity than valproic aside, but when they are used together, they have really very effective results,” said Ece Genç, PhD, of Yeditepe University in Istanbul, who reported on the research conducted in her laboratory.

Dr. Genç noted her research in rats has focused on the possible mechanisms of neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease: mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress and tissue damage, disruption in protein organization, and cell death caused by inflammatory changes. “Dopamine metabolism can itself be a toxic compound for the neurons,” she said, explaining that dopamine is critical for stabilizing nerve synapses, but its dysregulation can cause oxidative stress of the neurons, leading to cell death.

A key mechanism in the tremors PD patients experience is histone deacetylase, Dr. Genç said. “Histone acetylation and deacetylation are extremely important in these processes,” she said (Neurosci Lett. 2018 Feb 14;666:48-57). “Valproic acid is an antiepileptic drug; it is used in bipolar disorder and migraine complexes, but one of the major actions of valproic acid is that it caused histone deacetylase in the patients.”

Previous research that has shown the rotenone model of valproic acid provided neuroprotection helped drive her research, she said (Neurotox Res. 2010;17:130-41).

Future directions in her research would aim to synchronize cell cultures and in-vivo studies, and try to develop a method to measure alpha-synucleinopathy – abnormal levels of alpha-synuclein protein in the nerves of people with neurodegenerative diseases. “I think that alpha-synucleinopathy is the key word here,” Dr. Genç said. “We have to be very careful with alpha-synuclein proteins and their presence in individuals and, of course, with the successful use of valproic acid and histone deacetylase in patients, we can look for new drugs with less adverse effects.”

One of the drawbacks of valproic acid is that it affects so many different channels in the body. “We have to find some drugs with more targeted action.” Dr. Genç said.

Dr. Genç did not report any relevant disclosures.

NEW YORK – The loss of dopaminergic neurons is known to be a pivotal mechanism in Parkinson’s disease (PD), but early research into the anticonvulsant drug valproic acid has found it may produce antioxidant and neuroprotective actions that enhance the effects of levodopa, as reported at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

“Levodopa had better activity than valproic aside, but when they are used together, they have really very effective results,” said Ece Genç, PhD, of Yeditepe University in Istanbul, who reported on the research conducted in her laboratory.

Dr. Genç noted her research in rats has focused on the possible mechanisms of neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease: mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress and tissue damage, disruption in protein organization, and cell death caused by inflammatory changes. “Dopamine metabolism can itself be a toxic compound for the neurons,” she said, explaining that dopamine is critical for stabilizing nerve synapses, but its dysregulation can cause oxidative stress of the neurons, leading to cell death.

A key mechanism in the tremors PD patients experience is histone deacetylase, Dr. Genç said. “Histone acetylation and deacetylation are extremely important in these processes,” she said (Neurosci Lett. 2018 Feb 14;666:48-57). “Valproic acid is an antiepileptic drug; it is used in bipolar disorder and migraine complexes, but one of the major actions of valproic acid is that it caused histone deacetylase in the patients.”

Previous research that has shown the rotenone model of valproic acid provided neuroprotection helped drive her research, she said (Neurotox Res. 2010;17:130-41).

Future directions in her research would aim to synchronize cell cultures and in-vivo studies, and try to develop a method to measure alpha-synucleinopathy – abnormal levels of alpha-synuclein protein in the nerves of people with neurodegenerative diseases. “I think that alpha-synucleinopathy is the key word here,” Dr. Genç said. “We have to be very careful with alpha-synuclein proteins and their presence in individuals and, of course, with the successful use of valproic acid and histone deacetylase in patients, we can look for new drugs with less adverse effects.”

One of the drawbacks of valproic acid is that it affects so many different channels in the body. “We have to find some drugs with more targeted action.” Dr. Genç said.

Dr. Genç did not report any relevant disclosures.

REPORTING FROM ICPDMD 2018

Key clinical point: Valproic acid may complement levodopa in Parkinson’s treatment.

Major finding: Valproic acid was found to produce antioxidant and cell-preserving effects.

Study details: Early results of laboratory studies and review of previously published studies.

Disclosures: Dr. Genç did not report any relevant disclosures.

Open mind essential to tackling diverse symptoms of Parkinson’s

NEW YORK – One reason to (PD) is that a small but substantial proportion of patients with PD-like symptoms have a different diagnosis, according to an expert overview at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

“Fifteen to 20% of patients treated for Parkinson’s disease, even in the most established centers of excellence, do not have Parkinson’s disease on necropsy,” said A.V. Srinivasan, MD, PhD, DSc, of The Tamil Nadu Dr. M.G.R. Medical University, Chennai, India.

This does not preclude benefit from antiparkinson drugs in those patients with PD-like symptoms but a different etiology. Many can benefit from increased dopamine availability, even in the absence of PD, but it emphasizes the complexity of clinical diseases associated with diminished dopamine function, according to Dr. Srinivasan. He characterized this complexity as a reason to avoid a regimented approach to PD management.

“You can just imagine how much this influences our data analysis,” said Dr. Srinivasan, referring to clinical trials designed to generate evidence-based treatment. “We should remember that we should not be too statistically oriented,” he added, citing the adage that “statistics can cause paralysis in your analysis.”

PD is associated with a vast array of neurologic and physical symptoms attributable to PD that overlap with other neurologic disorders, which is the reason that a definitive diagnosis is challenging, according to Dr. Srinivasan. Listing symptoms that should prompt consideration of an alternative diagnosis, Dr. Srinivasan said hallucinations suggest diffuse Lewy body disease, myoclonus suggests corticobasal degeneration, and amyotrophy suggests multiple system atrophy.

“These are only clues, however,” said Dr. Srinivasan, suggesting their presence should prompt consideration of alternative diagnoses, but their absence does not confirm PD.

In some cases, further work-up with one or more of the array of increasingly sophisticated imaging strategies, such as the combination of SPECT and PET, might help clinicians reach a more definitive diagnosis of the underlying pathology, a step that might guide use of dopaminergic therapies. However, effective treatment of PD symptoms does not depend on a definitive diagnosis.

Rather, Dr. Srinivasan advocated an open mind to the management of symptoms, which he indicated are best addressed empirically. As PD or other progressive movement disorders advance, the goal is to keep patients functional and comfortable.

This includes managing patients beyond prescription drugs to address such complications as dysphagia or impaired balance. He advocated practical solutions for causes of impaired quality of life such as soft foods to facilitate swallowing or walkers to keep patients ambulatory. No option that leads to symptom relief should be discounted, including alternative therapies.

“Some clinicians are strongly opposed to nontraditional therapies, such as naturopathy and homeopathy, but these have all been used in Parkinson’s,” Dr. Srinivasan said. Although he did not present data to show efficacy, he indicated that relief of symptoms and improvement of quality of life is the point of any treatment, which should be individualized by response in every patient.

And individualized therapy – in relationship to patient age – is particularly important, according to Dr. Srinivasan. While younger patients typically tolerate relatively aggressive therapies aimed at both PD and its specific symptoms, older patients may accept less ambitious functional improvements to achieve an adequate quality of life.

“After 70 years of age, every additional year is a bonus. After 80 years, every week is a bonus. After 90 years, every minute is a bonus,” said Dr. Srinivasan, in emphasizing an appropriate clinical perspective.

NEW YORK – One reason to (PD) is that a small but substantial proportion of patients with PD-like symptoms have a different diagnosis, according to an expert overview at the International Conference on Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders.

“Fifteen to 20% of patients treated for Parkinson’s disease, even in the most established centers of excellence, do not have Parkinson’s disease on necropsy,” said A.V. Srinivasan, MD, PhD, DSc, of The Tamil Nadu Dr. M.G.R. Medical University, Chennai, India.