User login

Win Whitcomb: Mortality Rates Become a Measuring Stick for Hospital Performance

—Blue Oyster Cult

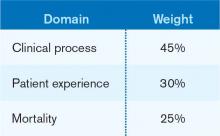

The designers of the hospital value-based purchasing (HVBP) program sought to include outcomes measures in 2014, and when they did, mortality was their choice. Specifically, HVBP for fiscal-year 2014 (starting October 2013) will include 30-day mortality rates for myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia. The weighting for the mortality domain will be 25% (see Table 1).

To review the requirements for the HVBP program in FY2014: All hospitals will have 1.25% of their Medicare inpatient payments withheld. They can earn back none, some, all, or an amount in excess of the 1.25%, depending on performance in the performance domains. To put it in perspective, 1.25% of Medicare inpatient payments for a 320-bed hospital are about $1 million. Such a hospital will have about $250,000 at risk in the mortality domain in FY2014.

Given the role hospitalists play in quality and safety initiatives, and the importance of medical record documentation in defining the risk of mortality and severity of illness, we can be crucial players in how our hospitals perform with regard to mortality.

Focus Areas for Mortality Reduction

Although many hospitalists might think that reducing mortality is like “boiling the ocean,” there are some areas where we can clearly focus our attention. There are four priority areas we should target in the coming years (also see Figure 1):

Reduce harm. This may take the form of reducing hospital-acquired infections, such as catheter-related UTIs, Clostridium difficile, and central-line-associated bloodstream infections, or reducing hospital-acquired VTE, falls, and delirium. Many hospital-acquired conditions have a collection, or bundle, of preventive practices. Hospitalists can work both in an institutional leadership capacity and in the course of daily clinical practice to implement bundles and best practices to reduce patient harm.

Improve teamwork. With hospitalists, “you started to have teams caring for inpatients in a coordinated way. So I regard this as [hospitalists] coming into their own, their vision of the future starting to really take hold,” said Brent James, coauthor of the recent Institute of Medicine report “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Partly, we’ve accomplished this through simply “showing up” and partly we’ve done it through becoming students of the art and science of teamwork. An example of teamwork training, developed by the Defense Department and the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ), is TeamSTEPPS, which offers a systematic approach to cooperation, coordination, and communication among team members. Optimal patient resuscitation, in-hospital handoffs, rapid-response teams, and early-warning systems are essential pieces of teamwork that may reduce mortality.

Improve evidence-based care. This domain covers process measures aimed at optimizing care, including reducing mortality. For HVBP in particular, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia are the focus.

Improve transitions of care. Best practices for care transitions and reducing readmissions, including advance-care planning, involvement of palliative care and hospice, and coordination with post-acute care, can be a key part of reducing 30-day mortality.

Documentation Integrity

Accurately capturing a patient’s condition in the medical record is crucial to assigning severity of illness and risk of mortality. Because mortality rates are severity-adjusted, accurate documentation is another important dimension to potentially improving a hospital’s performance with regard to the mortality domain. This is one more reason to work closely with your hospital’s documentation specialists.

Don’t Be Afraid...

Proponents of mortality as a quality measure point to it as the ultimate reflection of the care provided. While moving the needle might seem like a task too big to undertake, a disciplined approach to the elements of the driver diagram combined with a robust documentation program can provide your institution with a tangible focus on this definitive measure.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

—Blue Oyster Cult

The designers of the hospital value-based purchasing (HVBP) program sought to include outcomes measures in 2014, and when they did, mortality was their choice. Specifically, HVBP for fiscal-year 2014 (starting October 2013) will include 30-day mortality rates for myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia. The weighting for the mortality domain will be 25% (see Table 1).

To review the requirements for the HVBP program in FY2014: All hospitals will have 1.25% of their Medicare inpatient payments withheld. They can earn back none, some, all, or an amount in excess of the 1.25%, depending on performance in the performance domains. To put it in perspective, 1.25% of Medicare inpatient payments for a 320-bed hospital are about $1 million. Such a hospital will have about $250,000 at risk in the mortality domain in FY2014.

Given the role hospitalists play in quality and safety initiatives, and the importance of medical record documentation in defining the risk of mortality and severity of illness, we can be crucial players in how our hospitals perform with regard to mortality.

Focus Areas for Mortality Reduction

Although many hospitalists might think that reducing mortality is like “boiling the ocean,” there are some areas where we can clearly focus our attention. There are four priority areas we should target in the coming years (also see Figure 1):

Reduce harm. This may take the form of reducing hospital-acquired infections, such as catheter-related UTIs, Clostridium difficile, and central-line-associated bloodstream infections, or reducing hospital-acquired VTE, falls, and delirium. Many hospital-acquired conditions have a collection, or bundle, of preventive practices. Hospitalists can work both in an institutional leadership capacity and in the course of daily clinical practice to implement bundles and best practices to reduce patient harm.

Improve teamwork. With hospitalists, “you started to have teams caring for inpatients in a coordinated way. So I regard this as [hospitalists] coming into their own, their vision of the future starting to really take hold,” said Brent James, coauthor of the recent Institute of Medicine report “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Partly, we’ve accomplished this through simply “showing up” and partly we’ve done it through becoming students of the art and science of teamwork. An example of teamwork training, developed by the Defense Department and the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ), is TeamSTEPPS, which offers a systematic approach to cooperation, coordination, and communication among team members. Optimal patient resuscitation, in-hospital handoffs, rapid-response teams, and early-warning systems are essential pieces of teamwork that may reduce mortality.

Improve evidence-based care. This domain covers process measures aimed at optimizing care, including reducing mortality. For HVBP in particular, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia are the focus.

Improve transitions of care. Best practices for care transitions and reducing readmissions, including advance-care planning, involvement of palliative care and hospice, and coordination with post-acute care, can be a key part of reducing 30-day mortality.

Documentation Integrity

Accurately capturing a patient’s condition in the medical record is crucial to assigning severity of illness and risk of mortality. Because mortality rates are severity-adjusted, accurate documentation is another important dimension to potentially improving a hospital’s performance with regard to the mortality domain. This is one more reason to work closely with your hospital’s documentation specialists.

Don’t Be Afraid...

Proponents of mortality as a quality measure point to it as the ultimate reflection of the care provided. While moving the needle might seem like a task too big to undertake, a disciplined approach to the elements of the driver diagram combined with a robust documentation program can provide your institution with a tangible focus on this definitive measure.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

—Blue Oyster Cult

The designers of the hospital value-based purchasing (HVBP) program sought to include outcomes measures in 2014, and when they did, mortality was their choice. Specifically, HVBP for fiscal-year 2014 (starting October 2013) will include 30-day mortality rates for myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia. The weighting for the mortality domain will be 25% (see Table 1).

To review the requirements for the HVBP program in FY2014: All hospitals will have 1.25% of their Medicare inpatient payments withheld. They can earn back none, some, all, or an amount in excess of the 1.25%, depending on performance in the performance domains. To put it in perspective, 1.25% of Medicare inpatient payments for a 320-bed hospital are about $1 million. Such a hospital will have about $250,000 at risk in the mortality domain in FY2014.

Given the role hospitalists play in quality and safety initiatives, and the importance of medical record documentation in defining the risk of mortality and severity of illness, we can be crucial players in how our hospitals perform with regard to mortality.

Focus Areas for Mortality Reduction

Although many hospitalists might think that reducing mortality is like “boiling the ocean,” there are some areas where we can clearly focus our attention. There are four priority areas we should target in the coming years (also see Figure 1):

Reduce harm. This may take the form of reducing hospital-acquired infections, such as catheter-related UTIs, Clostridium difficile, and central-line-associated bloodstream infections, or reducing hospital-acquired VTE, falls, and delirium. Many hospital-acquired conditions have a collection, or bundle, of preventive practices. Hospitalists can work both in an institutional leadership capacity and in the course of daily clinical practice to implement bundles and best practices to reduce patient harm.

Improve teamwork. With hospitalists, “you started to have teams caring for inpatients in a coordinated way. So I regard this as [hospitalists] coming into their own, their vision of the future starting to really take hold,” said Brent James, coauthor of the recent Institute of Medicine report “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Partly, we’ve accomplished this through simply “showing up” and partly we’ve done it through becoming students of the art and science of teamwork. An example of teamwork training, developed by the Defense Department and the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ), is TeamSTEPPS, which offers a systematic approach to cooperation, coordination, and communication among team members. Optimal patient resuscitation, in-hospital handoffs, rapid-response teams, and early-warning systems are essential pieces of teamwork that may reduce mortality.

Improve evidence-based care. This domain covers process measures aimed at optimizing care, including reducing mortality. For HVBP in particular, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia are the focus.

Improve transitions of care. Best practices for care transitions and reducing readmissions, including advance-care planning, involvement of palliative care and hospice, and coordination with post-acute care, can be a key part of reducing 30-day mortality.

Documentation Integrity

Accurately capturing a patient’s condition in the medical record is crucial to assigning severity of illness and risk of mortality. Because mortality rates are severity-adjusted, accurate documentation is another important dimension to potentially improving a hospital’s performance with regard to the mortality domain. This is one more reason to work closely with your hospital’s documentation specialists.

Don’t Be Afraid...

Proponents of mortality as a quality measure point to it as the ultimate reflection of the care provided. While moving the needle might seem like a task too big to undertake, a disciplined approach to the elements of the driver diagram combined with a robust documentation program can provide your institution with a tangible focus on this definitive measure.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

Cardiologists Help Lower Readmission Rates for Hospitalized Heart Failure Patients

Data reported at the American Heart Association’s scientific sessions in Los Angeles in November suggest that when a cardiologist, rather than a hospitalist, is the attending physician for a hospitalized heart failure patient, readmission is less likely. Casey M. Lawler, MD, FACC, a cardiologist at the Minneapolis Heart Institute, says her center began establishing protocols to improve heart failure readmissions rates five years ago, after determining that many patients did not understand their diagnosis or treatment. “Thus, we became much more involved in post-discharge care,” including the phoning of discharged patients and follow-up with primary-care providers.

When the heart failure patients’ attending physicians were cardiologists, their readmission rate was 16%, versus 27.1% with hospitalists, even though their severity of illness was higher. Length of stay was similar for both groups and total mean costs were higher for the patients managed by cardiologists. “Although these results reveal that specialists have a positive impact on readmission rates, an overhaul to an entire healthcare system’s treatment of [heart failure] patients—from admission to post-discharge follow-up—is required to truly impact preventable readmissions,” Dr. Lawler asserted.

In the Minneapolis study, 65% of the 2,300 heart failure patients were managed by hospitalists, and 35% by cardiologists. A recent national survey of advanced heart failure programs found that cardiologists managed the care of acute HF patients more than 60 percent of the time.2

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

Data reported at the American Heart Association’s scientific sessions in Los Angeles in November suggest that when a cardiologist, rather than a hospitalist, is the attending physician for a hospitalized heart failure patient, readmission is less likely. Casey M. Lawler, MD, FACC, a cardiologist at the Minneapolis Heart Institute, says her center began establishing protocols to improve heart failure readmissions rates five years ago, after determining that many patients did not understand their diagnosis or treatment. “Thus, we became much more involved in post-discharge care,” including the phoning of discharged patients and follow-up with primary-care providers.

When the heart failure patients’ attending physicians were cardiologists, their readmission rate was 16%, versus 27.1% with hospitalists, even though their severity of illness was higher. Length of stay was similar for both groups and total mean costs were higher for the patients managed by cardiologists. “Although these results reveal that specialists have a positive impact on readmission rates, an overhaul to an entire healthcare system’s treatment of [heart failure] patients—from admission to post-discharge follow-up—is required to truly impact preventable readmissions,” Dr. Lawler asserted.

In the Minneapolis study, 65% of the 2,300 heart failure patients were managed by hospitalists, and 35% by cardiologists. A recent national survey of advanced heart failure programs found that cardiologists managed the care of acute HF patients more than 60 percent of the time.2

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

Data reported at the American Heart Association’s scientific sessions in Los Angeles in November suggest that when a cardiologist, rather than a hospitalist, is the attending physician for a hospitalized heart failure patient, readmission is less likely. Casey M. Lawler, MD, FACC, a cardiologist at the Minneapolis Heart Institute, says her center began establishing protocols to improve heart failure readmissions rates five years ago, after determining that many patients did not understand their diagnosis or treatment. “Thus, we became much more involved in post-discharge care,” including the phoning of discharged patients and follow-up with primary-care providers.

When the heart failure patients’ attending physicians were cardiologists, their readmission rate was 16%, versus 27.1% with hospitalists, even though their severity of illness was higher. Length of stay was similar for both groups and total mean costs were higher for the patients managed by cardiologists. “Although these results reveal that specialists have a positive impact on readmission rates, an overhaul to an entire healthcare system’s treatment of [heart failure] patients—from admission to post-discharge follow-up—is required to truly impact preventable readmissions,” Dr. Lawler asserted.

In the Minneapolis study, 65% of the 2,300 heart failure patients were managed by hospitalists, and 35% by cardiologists. A recent national survey of advanced heart failure programs found that cardiologists managed the care of acute HF patients more than 60 percent of the time.2

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: American Pain Society Board Member Discusses Opioid Risks, Rewards, and Why Continuing Education is a Must

Click here to listen to Scott Strassels, PhD, PharmD, BCPS, an assistant professor in the College of Pharmacy at the University of Texas at Austin and a board member of the American Pain Society, discuss the risks and rewards of opioid therapies, and why continuing education is important for all clinicians.

Click here to listen to Scott Strassels, PhD, PharmD, BCPS, an assistant professor in the College of Pharmacy at the University of Texas at Austin and a board member of the American Pain Society, discuss the risks and rewards of opioid therapies, and why continuing education is important for all clinicians.

Click here to listen to Scott Strassels, PhD, PharmD, BCPS, an assistant professor in the College of Pharmacy at the University of Texas at Austin and a board member of the American Pain Society, discuss the risks and rewards of opioid therapies, and why continuing education is important for all clinicians.

Quality Improvement Project Helps Hospital Patients Get Needed Prescriptions

A quality-improvement (QI) project to give high-risk patients ready access to prescribed medications at the time of hospital discharge achieved an 86% success rate, according to an abstract poster presented at HM12 in San Diego last April.1

Lead author Elizabeth Le, MD, then a resident at the University of California at San Francisco Medical Center (UCSF) and now a practicing hospitalist at the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Palo Alto, Calif., says the multidisciplinary “brown bag medications” project involved training house staff to recognize patients at risk. Staff meetings and rounds were used to identify appropriate candidates—those with limited mobility or cognitive issues, lacking insurance coverage or financial resources, a history of medication noncompliance, or leaving the hospital against medical advice—as well as those prescribed medications with a greater urgency for administration on schedule, such as anticoagulants or antibiotics.

About one-quarter of patients on the unit where this approach was first tested were found to need the service, which involved faxing prescriptions to an outpatient pharmacy across the street from the hospital for either pick-up by the family or delivery to the patient’s hospital room. For those with financial impediments, hospital social workers and case managers explored other options, including the social work department’s discretionary use fund, to pay for the drugs.

Dr. Le believes the project could be replicated in other facilities that lack access to in-house pharmacy services at discharge. She recommends involving social workers and case managers in the planning.

At UCSF, recent EHR implementation has automated the ordering of medications, but the challenge of recognizing who could benefit from extra help in obtaining their discharge medications remains a critical issue for hospitals trying to bring readmissions under control.

For more information about the brown bag medications program, contact Dr. Le at [email protected].

References

A quality-improvement (QI) project to give high-risk patients ready access to prescribed medications at the time of hospital discharge achieved an 86% success rate, according to an abstract poster presented at HM12 in San Diego last April.1

Lead author Elizabeth Le, MD, then a resident at the University of California at San Francisco Medical Center (UCSF) and now a practicing hospitalist at the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Palo Alto, Calif., says the multidisciplinary “brown bag medications” project involved training house staff to recognize patients at risk. Staff meetings and rounds were used to identify appropriate candidates—those with limited mobility or cognitive issues, lacking insurance coverage or financial resources, a history of medication noncompliance, or leaving the hospital against medical advice—as well as those prescribed medications with a greater urgency for administration on schedule, such as anticoagulants or antibiotics.

About one-quarter of patients on the unit where this approach was first tested were found to need the service, which involved faxing prescriptions to an outpatient pharmacy across the street from the hospital for either pick-up by the family or delivery to the patient’s hospital room. For those with financial impediments, hospital social workers and case managers explored other options, including the social work department’s discretionary use fund, to pay for the drugs.

Dr. Le believes the project could be replicated in other facilities that lack access to in-house pharmacy services at discharge. She recommends involving social workers and case managers in the planning.

At UCSF, recent EHR implementation has automated the ordering of medications, but the challenge of recognizing who could benefit from extra help in obtaining their discharge medications remains a critical issue for hospitals trying to bring readmissions under control.

For more information about the brown bag medications program, contact Dr. Le at [email protected].

References

A quality-improvement (QI) project to give high-risk patients ready access to prescribed medications at the time of hospital discharge achieved an 86% success rate, according to an abstract poster presented at HM12 in San Diego last April.1

Lead author Elizabeth Le, MD, then a resident at the University of California at San Francisco Medical Center (UCSF) and now a practicing hospitalist at the Veterans Administration Medical Center in Palo Alto, Calif., says the multidisciplinary “brown bag medications” project involved training house staff to recognize patients at risk. Staff meetings and rounds were used to identify appropriate candidates—those with limited mobility or cognitive issues, lacking insurance coverage or financial resources, a history of medication noncompliance, or leaving the hospital against medical advice—as well as those prescribed medications with a greater urgency for administration on schedule, such as anticoagulants or antibiotics.

About one-quarter of patients on the unit where this approach was first tested were found to need the service, which involved faxing prescriptions to an outpatient pharmacy across the street from the hospital for either pick-up by the family or delivery to the patient’s hospital room. For those with financial impediments, hospital social workers and case managers explored other options, including the social work department’s discretionary use fund, to pay for the drugs.

Dr. Le believes the project could be replicated in other facilities that lack access to in-house pharmacy services at discharge. She recommends involving social workers and case managers in the planning.

At UCSF, recent EHR implementation has automated the ordering of medications, but the challenge of recognizing who could benefit from extra help in obtaining their discharge medications remains a critical issue for hospitals trying to bring readmissions under control.

For more information about the brown bag medications program, contact Dr. Le at [email protected].

References

Smartphones Distract Hospital Staff on Rounds

Smartphone use by hospitalists and other hospital staff is becoming ubiquitous, with a recent survey showing 72% of physicians using these devices at work.1 At the same time, concerns are being raised about clinical distractions and threats to patient privacy, even while such benefits as rapid access to colleagues, medical references, and patient records are touted.

In a study published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Rachel Katz-Sidlow, MD, of the department of pediatrics at Jacobi Medical Center in Bronx, N.Y., and colleagues surveyed residents’ and attendings’ perceptions of the use of smartphones during inpatient rounds, both their own and observed behaviors of colleagues.2 Fifty-seven percent of residents and 28% of faculty reported using smartphones during inpatient rounds, while significantly higher percentages observed other team members doing so.

The most common smartphone uses were for patient care, but doctors also use them to read and reply to personal texts and emails, as well as for non-patient-care-related Web searches. The authors observe that smartphones “introduce another source of interruption, multitasking, and distraction into the hospital environment,” with potential negative consequences.

Nineteen percent of residents believed they had missed important clinical information because of smartphone distraction during rounds. After seeing the survey results, Jacobi Medical Center instituted a smartphone policy in February 2012, essentially requiring personal mobile communication devices to be silenced at the start of rounds, except for patient care communication or urgent family matters, Dr. Katz-Sidlow wrote in an email to the The Hospitalist.

Confirmation of the spread of communication technology in the hospital toward smartphones and away from traditional pagers comes from data presented at the American Academy of Pediatrics conference in New Orleans in October by Stephanie Kuhlmann, MD, pediatric hospitalist at the University of Kansas at Wichita.3 Dr. Kuhlmann conducted an electronic survey of pediatric hospitalists, with 60% reporting that they receive work-related text messages. Twelve percent sent more than 10 text messages per shift, while 40% expressed concern about HIPAA violations. Most text messages are not encrypted, and many hospitals have yet to implement appropriately secure programs and policies, Dr. Kuhlmann says.

“Hospitals need to be aware of this trend and need to find a way to secure these text messages,” she adds.

Another recent survey by the Orem, Utah-based firm KLAS Research found that while 70% of clinicians report using smartphones or tablets to look up electronic patient records, they are less likely to input information into the EHR on these devices because of the difficulty of entering data on their small screens.4

References

- Dolan B. 72 percent of US physicians use smartphones. Mobi Health News website. Available at: http://mobihealthnews.com/7505/72-percent-of-us-physicians-use-smartphones/. Accessed Dec. 8, 2012.

- Katz-Sidlow RJ, Ludwig A, Millers S, Sidlow R. Smartphone use during inpatient attending rounds: prevalence, patterns and potential for distraction. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(8):595-599.

- Miller NS. Text messages are a growing trend among pediatric hospitalists. Pediatric News Digital Network website. Available at: http://www.pediatricnews.com/news/top-news/single-article/text-messages-are-a-growing-trend-among-pediatric-hospitalists/3dabf7208c75c44d36f368a83221d320.html. Accessed Nov. 1, 2012.

- Westerlind E. Mobile healthcare applications: can enterprise vendors keep up? KLAS website. Available at: http://www.klasresearch.com/KLASreports. Accessed Dec. 8, 2012.

Smartphone use by hospitalists and other hospital staff is becoming ubiquitous, with a recent survey showing 72% of physicians using these devices at work.1 At the same time, concerns are being raised about clinical distractions and threats to patient privacy, even while such benefits as rapid access to colleagues, medical references, and patient records are touted.

In a study published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Rachel Katz-Sidlow, MD, of the department of pediatrics at Jacobi Medical Center in Bronx, N.Y., and colleagues surveyed residents’ and attendings’ perceptions of the use of smartphones during inpatient rounds, both their own and observed behaviors of colleagues.2 Fifty-seven percent of residents and 28% of faculty reported using smartphones during inpatient rounds, while significantly higher percentages observed other team members doing so.

The most common smartphone uses were for patient care, but doctors also use them to read and reply to personal texts and emails, as well as for non-patient-care-related Web searches. The authors observe that smartphones “introduce another source of interruption, multitasking, and distraction into the hospital environment,” with potential negative consequences.

Nineteen percent of residents believed they had missed important clinical information because of smartphone distraction during rounds. After seeing the survey results, Jacobi Medical Center instituted a smartphone policy in February 2012, essentially requiring personal mobile communication devices to be silenced at the start of rounds, except for patient care communication or urgent family matters, Dr. Katz-Sidlow wrote in an email to the The Hospitalist.

Confirmation of the spread of communication technology in the hospital toward smartphones and away from traditional pagers comes from data presented at the American Academy of Pediatrics conference in New Orleans in October by Stephanie Kuhlmann, MD, pediatric hospitalist at the University of Kansas at Wichita.3 Dr. Kuhlmann conducted an electronic survey of pediatric hospitalists, with 60% reporting that they receive work-related text messages. Twelve percent sent more than 10 text messages per shift, while 40% expressed concern about HIPAA violations. Most text messages are not encrypted, and many hospitals have yet to implement appropriately secure programs and policies, Dr. Kuhlmann says.

“Hospitals need to be aware of this trend and need to find a way to secure these text messages,” she adds.

Another recent survey by the Orem, Utah-based firm KLAS Research found that while 70% of clinicians report using smartphones or tablets to look up electronic patient records, they are less likely to input information into the EHR on these devices because of the difficulty of entering data on their small screens.4

References

- Dolan B. 72 percent of US physicians use smartphones. Mobi Health News website. Available at: http://mobihealthnews.com/7505/72-percent-of-us-physicians-use-smartphones/. Accessed Dec. 8, 2012.

- Katz-Sidlow RJ, Ludwig A, Millers S, Sidlow R. Smartphone use during inpatient attending rounds: prevalence, patterns and potential for distraction. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(8):595-599.

- Miller NS. Text messages are a growing trend among pediatric hospitalists. Pediatric News Digital Network website. Available at: http://www.pediatricnews.com/news/top-news/single-article/text-messages-are-a-growing-trend-among-pediatric-hospitalists/3dabf7208c75c44d36f368a83221d320.html. Accessed Nov. 1, 2012.

- Westerlind E. Mobile healthcare applications: can enterprise vendors keep up? KLAS website. Available at: http://www.klasresearch.com/KLASreports. Accessed Dec. 8, 2012.

Smartphone use by hospitalists and other hospital staff is becoming ubiquitous, with a recent survey showing 72% of physicians using these devices at work.1 At the same time, concerns are being raised about clinical distractions and threats to patient privacy, even while such benefits as rapid access to colleagues, medical references, and patient records are touted.

In a study published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Rachel Katz-Sidlow, MD, of the department of pediatrics at Jacobi Medical Center in Bronx, N.Y., and colleagues surveyed residents’ and attendings’ perceptions of the use of smartphones during inpatient rounds, both their own and observed behaviors of colleagues.2 Fifty-seven percent of residents and 28% of faculty reported using smartphones during inpatient rounds, while significantly higher percentages observed other team members doing so.

The most common smartphone uses were for patient care, but doctors also use them to read and reply to personal texts and emails, as well as for non-patient-care-related Web searches. The authors observe that smartphones “introduce another source of interruption, multitasking, and distraction into the hospital environment,” with potential negative consequences.

Nineteen percent of residents believed they had missed important clinical information because of smartphone distraction during rounds. After seeing the survey results, Jacobi Medical Center instituted a smartphone policy in February 2012, essentially requiring personal mobile communication devices to be silenced at the start of rounds, except for patient care communication or urgent family matters, Dr. Katz-Sidlow wrote in an email to the The Hospitalist.

Confirmation of the spread of communication technology in the hospital toward smartphones and away from traditional pagers comes from data presented at the American Academy of Pediatrics conference in New Orleans in October by Stephanie Kuhlmann, MD, pediatric hospitalist at the University of Kansas at Wichita.3 Dr. Kuhlmann conducted an electronic survey of pediatric hospitalists, with 60% reporting that they receive work-related text messages. Twelve percent sent more than 10 text messages per shift, while 40% expressed concern about HIPAA violations. Most text messages are not encrypted, and many hospitals have yet to implement appropriately secure programs and policies, Dr. Kuhlmann says.

“Hospitals need to be aware of this trend and need to find a way to secure these text messages,” she adds.

Another recent survey by the Orem, Utah-based firm KLAS Research found that while 70% of clinicians report using smartphones or tablets to look up electronic patient records, they are less likely to input information into the EHR on these devices because of the difficulty of entering data on their small screens.4

References

- Dolan B. 72 percent of US physicians use smartphones. Mobi Health News website. Available at: http://mobihealthnews.com/7505/72-percent-of-us-physicians-use-smartphones/. Accessed Dec. 8, 2012.

- Katz-Sidlow RJ, Ludwig A, Millers S, Sidlow R. Smartphone use during inpatient attending rounds: prevalence, patterns and potential for distraction. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(8):595-599.

- Miller NS. Text messages are a growing trend among pediatric hospitalists. Pediatric News Digital Network website. Available at: http://www.pediatricnews.com/news/top-news/single-article/text-messages-are-a-growing-trend-among-pediatric-hospitalists/3dabf7208c75c44d36f368a83221d320.html. Accessed Nov. 1, 2012.

- Westerlind E. Mobile healthcare applications: can enterprise vendors keep up? KLAS website. Available at: http://www.klasresearch.com/KLASreports. Accessed Dec. 8, 2012.

Society for Hospital Medicine Compiles List of Don'ts for Hospitalists

In hospital medicine, what a hospitalist doesn’t do can be just as important as what he or she does do.

That’s why SHM and hospitalist experts from across the country collaborated with the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation on its groundbreaking Choosing Wisely campaign to publish 10 procedures that hospitalists should think twice about before conducting. Together, with more than a dozen medical specialties, SHM will announce the list of procedures in Washington, D.C., on Feb. 21.

Of the medical specialties contributing lists to Choosing Wisely, SHM is unique in that it will publish two lists (each with five recommendations): one for adult HM and another for pediatric HM.

Once the recommendations have been made public, hospitalists will have multiple ways of learning about them. SHM will publish the recommendations online, via email, and in The Hospitalist. Details about the unique process of developing the Choosing Wisely lists—and the impact they will have on everyday hospitalist practice—will be published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

Others in healthcare, including patients and family members, will have a chance to learn about Choosing Wisely through a partnership with Consumer Reports and the public dialogue that the campaign hopes to generate.

SHM President Shaun Frost, MD, SFHM, has been unequivocal in his support for the campaign and has urged all hospitalists to support it as well. “Attention to care affordability and experience are essential to reforming our broken healthcare system, so let’s lead the charge in these areas and help others who are doing the same,” Dr. Frost wrote in the November 2012 issue of The Hospitalist.

To get more involved with this industry-changing campaign, visit www.choosingwisely.org and check out the upcoming Choosing Wisely pre-course at SHM’s annual meeting at www.hospitalmedicine2013.org.

In hospital medicine, what a hospitalist doesn’t do can be just as important as what he or she does do.

That’s why SHM and hospitalist experts from across the country collaborated with the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation on its groundbreaking Choosing Wisely campaign to publish 10 procedures that hospitalists should think twice about before conducting. Together, with more than a dozen medical specialties, SHM will announce the list of procedures in Washington, D.C., on Feb. 21.

Of the medical specialties contributing lists to Choosing Wisely, SHM is unique in that it will publish two lists (each with five recommendations): one for adult HM and another for pediatric HM.

Once the recommendations have been made public, hospitalists will have multiple ways of learning about them. SHM will publish the recommendations online, via email, and in The Hospitalist. Details about the unique process of developing the Choosing Wisely lists—and the impact they will have on everyday hospitalist practice—will be published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

Others in healthcare, including patients and family members, will have a chance to learn about Choosing Wisely through a partnership with Consumer Reports and the public dialogue that the campaign hopes to generate.

SHM President Shaun Frost, MD, SFHM, has been unequivocal in his support for the campaign and has urged all hospitalists to support it as well. “Attention to care affordability and experience are essential to reforming our broken healthcare system, so let’s lead the charge in these areas and help others who are doing the same,” Dr. Frost wrote in the November 2012 issue of The Hospitalist.

To get more involved with this industry-changing campaign, visit www.choosingwisely.org and check out the upcoming Choosing Wisely pre-course at SHM’s annual meeting at www.hospitalmedicine2013.org.

In hospital medicine, what a hospitalist doesn’t do can be just as important as what he or she does do.

That’s why SHM and hospitalist experts from across the country collaborated with the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation on its groundbreaking Choosing Wisely campaign to publish 10 procedures that hospitalists should think twice about before conducting. Together, with more than a dozen medical specialties, SHM will announce the list of procedures in Washington, D.C., on Feb. 21.

Of the medical specialties contributing lists to Choosing Wisely, SHM is unique in that it will publish two lists (each with five recommendations): one for adult HM and another for pediatric HM.

Once the recommendations have been made public, hospitalists will have multiple ways of learning about them. SHM will publish the recommendations online, via email, and in The Hospitalist. Details about the unique process of developing the Choosing Wisely lists—and the impact they will have on everyday hospitalist practice—will be published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

Others in healthcare, including patients and family members, will have a chance to learn about Choosing Wisely through a partnership with Consumer Reports and the public dialogue that the campaign hopes to generate.

SHM President Shaun Frost, MD, SFHM, has been unequivocal in his support for the campaign and has urged all hospitalists to support it as well. “Attention to care affordability and experience are essential to reforming our broken healthcare system, so let’s lead the charge in these areas and help others who are doing the same,” Dr. Frost wrote in the November 2012 issue of The Hospitalist.

To get more involved with this industry-changing campaign, visit www.choosingwisely.org and check out the upcoming Choosing Wisely pre-course at SHM’s annual meeting at www.hospitalmedicine2013.org.

Danielle Scheurer, MD: Hospital Providers Put Premium on Keeping Themselves, Hospital Patients Safe

It’s great to be a Tennessee Volunteer. I said, It’s great to be a Tennessee Volunteer!

The crowd, a sea of orange, packs into Neyland Stadium in Knoxville, Tenn., brimming with pride, dedicated to the team they call the Vols. Neyland Stadium, built in 1921, comfortably seats more than 100,000 brash fans on most fall weekends during the college football season. These die-hard fans pack the stadium regularly, hoping to catch a glimpse of victory.

Throughout the decades of Tennessee Volunteers football, numerous coaches have spent countless hours thinking about how to realize those victories. And they have also spent a lot time thinking about how to keep their players safe. Each coach has had different styles and tactics, but all had one thing in common: They were clearly invested in keeping their players safe. A safe player is a good player, one who can make the full season without injury. As such, before each practice and each game, the players don the gear required to play the safest game possible.

This gear is expensive, difficult to put on, difficult to keep on, makes them run slower, and makes them sweat heavier. When you think about it, it is a wonder that they wear it at all—unless you consider the fact that each precisely placed article takes them one step closer to surviving the game intact, and making it to the next victory. Just like any other type of protective equipment, football equipment has evolved over the course of time. The helmet, for example, is now custom-fit for each player with calipers, and then subsequent additions are applied to ensure durability, shock resistance, and comfort. Relatively new additions include eye shields (to protect the eyes and reduce glare) and even radio devices (to allow the coach to relay last-minute critical information to the quarterback). These helmets are all customized to the players’ position, to allow for the best balance between protection and visibility.

And the helmet is just the beginning. The remaining bare minimum amount of gear needed for standard player safety includes a mouthpiece, jaw pads, neck roll, shoulder pads, shock pads, rib pads, hip pads, knee pads, and cleats. All told, the weight of all this equipment is between 10 and 25 pounds and takes up to an hour to fully gear up. But nonetheless, it has become such a mainstay, of centralized importance to the game, that each team has a dedicated equipment manager. They are charged with providing, maintaining, and transporting the best gear for every member of the team. The equipment manager is a vital resource for the team and the sport.

Despite the extra weight and inconvenience that their gear can burden them with, you don’t see a single football player “skimp” on it. And it would certainly be obvious to all those around them if they ran onto the field without their helmet. Over the years, the football industry has not abandoned gear that they thought was less than perfect, too heavy, too bulky, or made the player perform with less agility. They just made the gear better, lighter, more comfortable, and more protective.

You Can Do This

In a similar fashion, hospital providers have become increasingly interested in keeping themselves—and the patient—safe. But have we come to consensus on who the coach and equipment managers should be, and what the essential elements of the gear should be? I would argue there are a number of coaches and equipment managers in the hospital setting whose mission is to keep their “players” safe. The players are both patients and providers, as generally a “safe provider” is one who makes and implements solid decisions, and who is housed within a safe, predictable, and highly-reliable system, is also one who can and will keep their patients safe.

We may not think of ourselves as such, but hospitalists can be extremely effective coaches and equipment managers. They can help create and maintain safe and effective gear for themselves and those patients and providers around them. They can be a mentor for displaying how vitally import this gear is and can work to improve it when it proves to be imperfect.

Although we don’t tend to think of these things as “safety gear,” these things do, in fact, keep us and our patients safe. Some of these include:

- Computerized physician order entry (CPOE) with decision support (or order sets without CPOE);

- Checklists;

- Procedural time-outs;

- Protocols;

- Medication dosing guidelines;

- Handheld devices (for quick lookup of medication doses, side effects, predictive scoring systems, medical calculators, etc.); and

- Gowns and gloves.

Additional “gear” for the patients can include:

- Arm bands for identification and medication scanning;

- Telemetry;

- Bed alarms;

- IV pumps with guard rails around dosing;

- Antibiotic impregnated central lines; and

- Early mobilization protocols.

The Next Level

To take the medical industry to the next level of safe reliability, we need all providers to accept and embrace the concept of “safety gear” for themselves and for their patients. We need to make it perfectly obvious when that gear is missing. It should invoke a reaction of ghastly fear when we witness anyone (provider, patient, or family) skimping on their gear: removing an armband for convenience, bypassing a smart pump, or skipping decision support in CPOE. And for the current gear that is imperfect, slows us down, beeps too often, or reduces our agility, the solution should include improving the gear, not ignoring it or discounting its importance.

So before you go to work today (every day?), think about what you need to keep yourself and your patients safe. And get your gear on.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

It’s great to be a Tennessee Volunteer. I said, It’s great to be a Tennessee Volunteer!

The crowd, a sea of orange, packs into Neyland Stadium in Knoxville, Tenn., brimming with pride, dedicated to the team they call the Vols. Neyland Stadium, built in 1921, comfortably seats more than 100,000 brash fans on most fall weekends during the college football season. These die-hard fans pack the stadium regularly, hoping to catch a glimpse of victory.

Throughout the decades of Tennessee Volunteers football, numerous coaches have spent countless hours thinking about how to realize those victories. And they have also spent a lot time thinking about how to keep their players safe. Each coach has had different styles and tactics, but all had one thing in common: They were clearly invested in keeping their players safe. A safe player is a good player, one who can make the full season without injury. As such, before each practice and each game, the players don the gear required to play the safest game possible.

This gear is expensive, difficult to put on, difficult to keep on, makes them run slower, and makes them sweat heavier. When you think about it, it is a wonder that they wear it at all—unless you consider the fact that each precisely placed article takes them one step closer to surviving the game intact, and making it to the next victory. Just like any other type of protective equipment, football equipment has evolved over the course of time. The helmet, for example, is now custom-fit for each player with calipers, and then subsequent additions are applied to ensure durability, shock resistance, and comfort. Relatively new additions include eye shields (to protect the eyes and reduce glare) and even radio devices (to allow the coach to relay last-minute critical information to the quarterback). These helmets are all customized to the players’ position, to allow for the best balance between protection and visibility.

And the helmet is just the beginning. The remaining bare minimum amount of gear needed for standard player safety includes a mouthpiece, jaw pads, neck roll, shoulder pads, shock pads, rib pads, hip pads, knee pads, and cleats. All told, the weight of all this equipment is between 10 and 25 pounds and takes up to an hour to fully gear up. But nonetheless, it has become such a mainstay, of centralized importance to the game, that each team has a dedicated equipment manager. They are charged with providing, maintaining, and transporting the best gear for every member of the team. The equipment manager is a vital resource for the team and the sport.

Despite the extra weight and inconvenience that their gear can burden them with, you don’t see a single football player “skimp” on it. And it would certainly be obvious to all those around them if they ran onto the field without their helmet. Over the years, the football industry has not abandoned gear that they thought was less than perfect, too heavy, too bulky, or made the player perform with less agility. They just made the gear better, lighter, more comfortable, and more protective.

You Can Do This

In a similar fashion, hospital providers have become increasingly interested in keeping themselves—and the patient—safe. But have we come to consensus on who the coach and equipment managers should be, and what the essential elements of the gear should be? I would argue there are a number of coaches and equipment managers in the hospital setting whose mission is to keep their “players” safe. The players are both patients and providers, as generally a “safe provider” is one who makes and implements solid decisions, and who is housed within a safe, predictable, and highly-reliable system, is also one who can and will keep their patients safe.

We may not think of ourselves as such, but hospitalists can be extremely effective coaches and equipment managers. They can help create and maintain safe and effective gear for themselves and those patients and providers around them. They can be a mentor for displaying how vitally import this gear is and can work to improve it when it proves to be imperfect.

Although we don’t tend to think of these things as “safety gear,” these things do, in fact, keep us and our patients safe. Some of these include:

- Computerized physician order entry (CPOE) with decision support (or order sets without CPOE);

- Checklists;

- Procedural time-outs;

- Protocols;

- Medication dosing guidelines;

- Handheld devices (for quick lookup of medication doses, side effects, predictive scoring systems, medical calculators, etc.); and

- Gowns and gloves.

Additional “gear” for the patients can include:

- Arm bands for identification and medication scanning;

- Telemetry;

- Bed alarms;

- IV pumps with guard rails around dosing;

- Antibiotic impregnated central lines; and

- Early mobilization protocols.

The Next Level

To take the medical industry to the next level of safe reliability, we need all providers to accept and embrace the concept of “safety gear” for themselves and for their patients. We need to make it perfectly obvious when that gear is missing. It should invoke a reaction of ghastly fear when we witness anyone (provider, patient, or family) skimping on their gear: removing an armband for convenience, bypassing a smart pump, or skipping decision support in CPOE. And for the current gear that is imperfect, slows us down, beeps too often, or reduces our agility, the solution should include improving the gear, not ignoring it or discounting its importance.

So before you go to work today (every day?), think about what you need to keep yourself and your patients safe. And get your gear on.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

It’s great to be a Tennessee Volunteer. I said, It’s great to be a Tennessee Volunteer!

The crowd, a sea of orange, packs into Neyland Stadium in Knoxville, Tenn., brimming with pride, dedicated to the team they call the Vols. Neyland Stadium, built in 1921, comfortably seats more than 100,000 brash fans on most fall weekends during the college football season. These die-hard fans pack the stadium regularly, hoping to catch a glimpse of victory.

Throughout the decades of Tennessee Volunteers football, numerous coaches have spent countless hours thinking about how to realize those victories. And they have also spent a lot time thinking about how to keep their players safe. Each coach has had different styles and tactics, but all had one thing in common: They were clearly invested in keeping their players safe. A safe player is a good player, one who can make the full season without injury. As such, before each practice and each game, the players don the gear required to play the safest game possible.

This gear is expensive, difficult to put on, difficult to keep on, makes them run slower, and makes them sweat heavier. When you think about it, it is a wonder that they wear it at all—unless you consider the fact that each precisely placed article takes them one step closer to surviving the game intact, and making it to the next victory. Just like any other type of protective equipment, football equipment has evolved over the course of time. The helmet, for example, is now custom-fit for each player with calipers, and then subsequent additions are applied to ensure durability, shock resistance, and comfort. Relatively new additions include eye shields (to protect the eyes and reduce glare) and even radio devices (to allow the coach to relay last-minute critical information to the quarterback). These helmets are all customized to the players’ position, to allow for the best balance between protection and visibility.

And the helmet is just the beginning. The remaining bare minimum amount of gear needed for standard player safety includes a mouthpiece, jaw pads, neck roll, shoulder pads, shock pads, rib pads, hip pads, knee pads, and cleats. All told, the weight of all this equipment is between 10 and 25 pounds and takes up to an hour to fully gear up. But nonetheless, it has become such a mainstay, of centralized importance to the game, that each team has a dedicated equipment manager. They are charged with providing, maintaining, and transporting the best gear for every member of the team. The equipment manager is a vital resource for the team and the sport.

Despite the extra weight and inconvenience that their gear can burden them with, you don’t see a single football player “skimp” on it. And it would certainly be obvious to all those around them if they ran onto the field without their helmet. Over the years, the football industry has not abandoned gear that they thought was less than perfect, too heavy, too bulky, or made the player perform with less agility. They just made the gear better, lighter, more comfortable, and more protective.

You Can Do This

In a similar fashion, hospital providers have become increasingly interested in keeping themselves—and the patient—safe. But have we come to consensus on who the coach and equipment managers should be, and what the essential elements of the gear should be? I would argue there are a number of coaches and equipment managers in the hospital setting whose mission is to keep their “players” safe. The players are both patients and providers, as generally a “safe provider” is one who makes and implements solid decisions, and who is housed within a safe, predictable, and highly-reliable system, is also one who can and will keep their patients safe.

We may not think of ourselves as such, but hospitalists can be extremely effective coaches and equipment managers. They can help create and maintain safe and effective gear for themselves and those patients and providers around them. They can be a mentor for displaying how vitally import this gear is and can work to improve it when it proves to be imperfect.

Although we don’t tend to think of these things as “safety gear,” these things do, in fact, keep us and our patients safe. Some of these include:

- Computerized physician order entry (CPOE) with decision support (or order sets without CPOE);

- Checklists;

- Procedural time-outs;

- Protocols;

- Medication dosing guidelines;

- Handheld devices (for quick lookup of medication doses, side effects, predictive scoring systems, medical calculators, etc.); and

- Gowns and gloves.

Additional “gear” for the patients can include:

- Arm bands for identification and medication scanning;

- Telemetry;

- Bed alarms;

- IV pumps with guard rails around dosing;

- Antibiotic impregnated central lines; and

- Early mobilization protocols.

The Next Level

To take the medical industry to the next level of safe reliability, we need all providers to accept and embrace the concept of “safety gear” for themselves and for their patients. We need to make it perfectly obvious when that gear is missing. It should invoke a reaction of ghastly fear when we witness anyone (provider, patient, or family) skimping on their gear: removing an armband for convenience, bypassing a smart pump, or skipping decision support in CPOE. And for the current gear that is imperfect, slows us down, beeps too often, or reduces our agility, the solution should include improving the gear, not ignoring it or discounting its importance.

So before you go to work today (every day?), think about what you need to keep yourself and your patients safe. And get your gear on.

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at [email protected].

TeamSTEPPS Initiative Teaches Teamwork to Healthcare Providers

University of Minnesota hospitalist Karyn Baum, MD, MSEd, directs one of six regional training centers for Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety (TeamSTEPPS), an evidence-based, multimedia curriculum, tool set, and system for healthcare organizations to improve their teamwork.

Using the TeamSTEPPS approach, Dr. Baum collaborated with hospitalist Albertine Beard, MD, and the charge nurse on a 28-bed medical unit at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center to present a half-day training session for all VA staff, including four hospitalists. The seminar mixed didactics, discussions, and simulations, similar to traditional role-playing techniques but using a high-fidelity manikin that talks and displays vital signs.

"Teamwork is a set of knowledge, skills, and attitudes that lead to the creation of a culture where it’s about us as a team, not about who is highest in the hierarchy," Dr. Baum says. Hospitalists want to be leaders, "but we have a responsibility to be intentional leaders, learning the skills and modeling them," she adds.

Improved teamwork benefits patients through more effective communication and reduction in medical errors, Dr. Baum says, "but it also helps to create a healthy environment in which to work, where we all have each other’s backs."

TeamSTEPPS, developed jointly by the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the Department of Defense, has reached 25% to 30% of U.S. hospitals by annually training about 700 masters. The masters then go back to their institutions and share the techniques.

Read more about why improving teamwork is good for your patients.

University of Minnesota hospitalist Karyn Baum, MD, MSEd, directs one of six regional training centers for Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety (TeamSTEPPS), an evidence-based, multimedia curriculum, tool set, and system for healthcare organizations to improve their teamwork.

Using the TeamSTEPPS approach, Dr. Baum collaborated with hospitalist Albertine Beard, MD, and the charge nurse on a 28-bed medical unit at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center to present a half-day training session for all VA staff, including four hospitalists. The seminar mixed didactics, discussions, and simulations, similar to traditional role-playing techniques but using a high-fidelity manikin that talks and displays vital signs.

"Teamwork is a set of knowledge, skills, and attitudes that lead to the creation of a culture where it’s about us as a team, not about who is highest in the hierarchy," Dr. Baum says. Hospitalists want to be leaders, "but we have a responsibility to be intentional leaders, learning the skills and modeling them," she adds.

Improved teamwork benefits patients through more effective communication and reduction in medical errors, Dr. Baum says, "but it also helps to create a healthy environment in which to work, where we all have each other’s backs."

TeamSTEPPS, developed jointly by the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the Department of Defense, has reached 25% to 30% of U.S. hospitals by annually training about 700 masters. The masters then go back to their institutions and share the techniques.

Read more about why improving teamwork is good for your patients.

University of Minnesota hospitalist Karyn Baum, MD, MSEd, directs one of six regional training centers for Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety (TeamSTEPPS), an evidence-based, multimedia curriculum, tool set, and system for healthcare organizations to improve their teamwork.

Using the TeamSTEPPS approach, Dr. Baum collaborated with hospitalist Albertine Beard, MD, and the charge nurse on a 28-bed medical unit at the Minneapolis VA Medical Center to present a half-day training session for all VA staff, including four hospitalists. The seminar mixed didactics, discussions, and simulations, similar to traditional role-playing techniques but using a high-fidelity manikin that talks and displays vital signs.

"Teamwork is a set of knowledge, skills, and attitudes that lead to the creation of a culture where it’s about us as a team, not about who is highest in the hierarchy," Dr. Baum says. Hospitalists want to be leaders, "but we have a responsibility to be intentional leaders, learning the skills and modeling them," she adds.

Improved teamwork benefits patients through more effective communication and reduction in medical errors, Dr. Baum says, "but it also helps to create a healthy environment in which to work, where we all have each other’s backs."

TeamSTEPPS, developed jointly by the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and the Department of Defense, has reached 25% to 30% of U.S. hospitals by annually training about 700 masters. The masters then go back to their institutions and share the techniques.

Read more about why improving teamwork is good for your patients.

Why Hospitalists Should Pay Special Attention to Kidney Disease

Need another reason to hone your skills in treating people with kidney disease?

Take a look at a study out of the University of Washington: Kidney disease, researchers there found, is the diagnosis associated with the highest rate of readmission to the hospital and the emergency room and hospital mortality—controlling for cardiovascular disease, infection, sepsis, encephalopathy and “all the usual suspects associated with readmission,” says Katherine Tuttle, MD, clinical professor of medicine in the University of Washington Division of Nephrology.

The reasons are not known.

“One reason we think is really important is this issue of medication management,” Dr. Tuttle says.

Researchers then did a pilot study showing that, at the time of discharge, if a pharmacist visited within the first week, the rates of readmission were reduced by 50 percent. “The goal of that visit was basically do what probably should have been done through the hospital, which is adjust drug doses properly for kidney function and address drug interaction,” Dr. Tuttle says.

The research team is working on a large study funded by the National Institutes of Health to validate those findings and look at a broader population of patients. This is more evidence pointing to the importance of handoffs, she says.

"These transitions in care are dangerous situations,” Dr. Tuttle says. “But they’re also opportunities for improvement. And I think anything we can do to enhance education management is likely to be very beneficial in people with chronic kidney disease.”

Hospitalists have "serious work to do in improving continuity in care, and handoffs in general,” she adds.

“So much of what they do in the hospital is influenced by kidney function, whether it’s the drugs they give or the diagnostic tests that they want to do,” she says. “I’m not being critical at all. It’s a new area, relatively speaking, and there are lots of opportunities for improvement in the system.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

Reference

1. Risks of subsequent hospitalization and death in patients with kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(3):409-416.

Need another reason to hone your skills in treating people with kidney disease?

Take a look at a study out of the University of Washington: Kidney disease, researchers there found, is the diagnosis associated with the highest rate of readmission to the hospital and the emergency room and hospital mortality—controlling for cardiovascular disease, infection, sepsis, encephalopathy and “all the usual suspects associated with readmission,” says Katherine Tuttle, MD, clinical professor of medicine in the University of Washington Division of Nephrology.

The reasons are not known.

“One reason we think is really important is this issue of medication management,” Dr. Tuttle says.

Researchers then did a pilot study showing that, at the time of discharge, if a pharmacist visited within the first week, the rates of readmission were reduced by 50 percent. “The goal of that visit was basically do what probably should have been done through the hospital, which is adjust drug doses properly for kidney function and address drug interaction,” Dr. Tuttle says.

The research team is working on a large study funded by the National Institutes of Health to validate those findings and look at a broader population of patients. This is more evidence pointing to the importance of handoffs, she says.

"These transitions in care are dangerous situations,” Dr. Tuttle says. “But they’re also opportunities for improvement. And I think anything we can do to enhance education management is likely to be very beneficial in people with chronic kidney disease.”

Hospitalists have "serious work to do in improving continuity in care, and handoffs in general,” she adds.

“So much of what they do in the hospital is influenced by kidney function, whether it’s the drugs they give or the diagnostic tests that they want to do,” she says. “I’m not being critical at all. It’s a new area, relatively speaking, and there are lots of opportunities for improvement in the system.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

Reference

1. Risks of subsequent hospitalization and death in patients with kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(3):409-416.

Need another reason to hone your skills in treating people with kidney disease?

Take a look at a study out of the University of Washington: Kidney disease, researchers there found, is the diagnosis associated with the highest rate of readmission to the hospital and the emergency room and hospital mortality—controlling for cardiovascular disease, infection, sepsis, encephalopathy and “all the usual suspects associated with readmission,” says Katherine Tuttle, MD, clinical professor of medicine in the University of Washington Division of Nephrology.

The reasons are not known.

“One reason we think is really important is this issue of medication management,” Dr. Tuttle says.

Researchers then did a pilot study showing that, at the time of discharge, if a pharmacist visited within the first week, the rates of readmission were reduced by 50 percent. “The goal of that visit was basically do what probably should have been done through the hospital, which is adjust drug doses properly for kidney function and address drug interaction,” Dr. Tuttle says.

The research team is working on a large study funded by the National Institutes of Health to validate those findings and look at a broader population of patients. This is more evidence pointing to the importance of handoffs, she says.

"These transitions in care are dangerous situations,” Dr. Tuttle says. “But they’re also opportunities for improvement. And I think anything we can do to enhance education management is likely to be very beneficial in people with chronic kidney disease.”

Hospitalists have "serious work to do in improving continuity in care, and handoffs in general,” she adds.

“So much of what they do in the hospital is influenced by kidney function, whether it’s the drugs they give or the diagnostic tests that they want to do,” she says. “I’m not being critical at all. It’s a new area, relatively speaking, and there are lots of opportunities for improvement in the system.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

Reference

1. Risks of subsequent hospitalization and death in patients with kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(3):409-416.

Performance Disconnect: Measures Don’t Improve Hospitals’ Readmissions Experience

Two recent studies have reached the same surprising conclusion: Adherence to national quality and performance guidelines does not translate into reduced readmissions rates.

Sula Mazimba, MD, MPH, and colleagues at Kettering Medical Center in Kettering, Ohio, focused on congestive heart failure (CHF) patients, documenting compliance with four core CHF performance measures at discharge and subsequent 30-day readmissions. Only one measure-assessment of left ventricular function-had a significant association with readmissions.

A second study published the same month looked at a wider range of diagnoses in a Medicare population at more than 2,000 hospitals nationwide. That study reached similar conclusions about the disconnect between hospitals that followed Hospital Compare process quality measures and their readmission rates.

Dr. Mazimba says hospitalists and other physicians involved in quality improvement (QI) should be more involved in defining quality measures that reflect quality of care for their patients.

“We should be looking for parameters that have a higher yield for outcomes, such as preventing readmissions,” he says, encouraging better symptom management before the CHF patient is hospitalized and enhanced coordination of care after discharge.

Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, SFHM, professor and chair of the department of medicine and executive director of the hospitalist program at the University of California at Irvine, says the findings are important, but he adds that the core quality measures studied were never designed to address readmissions.

“The challenge is to find a way to connect the dots between the core measures and readmissions,” he says.

Learn more about the four "core" heart failure quality measures for hospitals by visiting the Resource Rooms on the SHM website, or check out this 80-page implementation guide, “Improving Heart Failure Care for Hospitalized Patients [PDF],” also available on SHM’s website.

Read The Hospitalist columnist Win Whitcomb’s take on readmissions penalty programs.

Two recent studies have reached the same surprising conclusion: Adherence to national quality and performance guidelines does not translate into reduced readmissions rates.

Sula Mazimba, MD, MPH, and colleagues at Kettering Medical Center in Kettering, Ohio, focused on congestive heart failure (CHF) patients, documenting compliance with four core CHF performance measures at discharge and subsequent 30-day readmissions. Only one measure-assessment of left ventricular function-had a significant association with readmissions.

A second study published the same month looked at a wider range of diagnoses in a Medicare population at more than 2,000 hospitals nationwide. That study reached similar conclusions about the disconnect between hospitals that followed Hospital Compare process quality measures and their readmission rates.

Dr. Mazimba says hospitalists and other physicians involved in quality improvement (QI) should be more involved in defining quality measures that reflect quality of care for their patients.

“We should be looking for parameters that have a higher yield for outcomes, such as preventing readmissions,” he says, encouraging better symptom management before the CHF patient is hospitalized and enhanced coordination of care after discharge.

Alpesh Amin, MD, MBA, SFHM, professor and chair of the department of medicine and executive director of the hospitalist program at the University of California at Irvine, says the findings are important, but he adds that the core quality measures studied were never designed to address readmissions.