User login

Drive Change in an ACO

From informal polls I’ve recently conducted of hospitalists, many are not even aware they are part of an accountable-care organization (ACO). And if they are aware, they might not be engaging in meaningful dialogue with ACO leaders about their role in these organizations. But, in the long term, ACOs will need to bring hospitalists to the table in order to be successful.

Are You Part of an ACO?

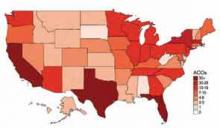

David Muhlestein, who blogs for Health Affairs, tracks the growth of ACOs around the country. He states that, as of Jan. 31, there were 428 ACOs in the U.S. (see Figure 1).1 In terms of numbers, Florida, Texas, and California lead the nation with 42, 33, and 46 ACOs, respectively. So it is likely that you are part of an ACO. If you are unsure, ask your chief medical officer or president of the medical staff.

How ACOs Work

All ACOs seek to manage a group, or population, of patients as efficiently as possible while maintaining or improving quality of care. For Medicare ACOs, the goal is to bring together hospitals and physicians in order to share savings derived from efficiencies in care. But before any savings can be shared, the Medicare ACO must demonstrate that it achieved high-quality care across four domains, totaling 33 individual quality measures. (see Table 1)

Main Flavors of ACOs

There are two types of ACOs: private ACOs and Medicare ACOs. Prior to Medicare ACOs, which were launched in January 2012, there were 150 private-sector ACOs, and this number continues to grow. Private ACOs represent a heterogeneous group in terms of reimbursement model. Some operate under shared savings programs; others use full or partial capitation, bundled payments, and/or other types of arrangements. But nearly all ACOs operate under the premise that the incentives used to make care more efficient and less costly can only be applied if measurable quality is maintained or improved. ACOs do not pay doctors or hospitals more unless high quality is demonstrated.

ACO Quality Measures and Hospitalists

Most of the 33 quality measures required by Medicare ACOs are based in ambulatory practice. These include measures related to blood pressure, immunizations, cancer, and fall-risk screening, and measures for diabetics, such as lipids and hemoglobin A1C. However, there are a few measures for which hospitalists should share in accountability, including:

- All-cause hospital readmission rate—risk-standardized;

- Ambulatory sensitive condition hospital admission rates (CHF, COPD); and

- Medication reconciliation after discharge from an inpatient facility.

Four Key Actions for Hospitalists

Hospitalists make a significant contribution to the quality and the financial performance of ACOs. In addition to the quality metrics cited above, hospitalists impact the inpatient portion of the overall population’s cost of care. Furthermore, hospitalists are vital partners in the care coordination required for an ACO to be successful.

Here are four actions I suggest taking in order for your hospitalist group to be effective as participants in an ACO:

- Have a representative from your group participate in ACO committees that address hospital utilization and related matters, such as care coordination impacting pre- and post-hospital care.

- Learn how to work with ACO case managers on care transitions, including post-discharge follow-up and information transfer.

- Understand an ACO’s approach to engagement of and coordination with post-acute-care facilities. The ability of a post-acute facility, such a skilled nursing facility, to accept patients who have complex care needs, to manage changes in condition in the facility when appropriate, and to send complete information upon transfer to the hospital are important strategies for an ACO’s success.

- Understand how an ACO reports quality and cost performance and how savings will be shared among participants.

Mindset Change

If hospitalists are part of the chain of ACO physicians and providers held accountable for the health of a population of patients, we must work more closely with the medical home/neighborhood, post-acute-care facilities, and home-care providers. The change in mindset will occur only if we have a set of tools to get the job done, such as case managers and information technology, and the appropriate incentives to support better care coordination. I encourage my fellow hospitalists to make things happen, instead of taking a passive role in this monumental transformation.

Reference

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

From informal polls I’ve recently conducted of hospitalists, many are not even aware they are part of an accountable-care organization (ACO). And if they are aware, they might not be engaging in meaningful dialogue with ACO leaders about their role in these organizations. But, in the long term, ACOs will need to bring hospitalists to the table in order to be successful.

Are You Part of an ACO?

David Muhlestein, who blogs for Health Affairs, tracks the growth of ACOs around the country. He states that, as of Jan. 31, there were 428 ACOs in the U.S. (see Figure 1).1 In terms of numbers, Florida, Texas, and California lead the nation with 42, 33, and 46 ACOs, respectively. So it is likely that you are part of an ACO. If you are unsure, ask your chief medical officer or president of the medical staff.

How ACOs Work

All ACOs seek to manage a group, or population, of patients as efficiently as possible while maintaining or improving quality of care. For Medicare ACOs, the goal is to bring together hospitals and physicians in order to share savings derived from efficiencies in care. But before any savings can be shared, the Medicare ACO must demonstrate that it achieved high-quality care across four domains, totaling 33 individual quality measures. (see Table 1)

Main Flavors of ACOs

There are two types of ACOs: private ACOs and Medicare ACOs. Prior to Medicare ACOs, which were launched in January 2012, there were 150 private-sector ACOs, and this number continues to grow. Private ACOs represent a heterogeneous group in terms of reimbursement model. Some operate under shared savings programs; others use full or partial capitation, bundled payments, and/or other types of arrangements. But nearly all ACOs operate under the premise that the incentives used to make care more efficient and less costly can only be applied if measurable quality is maintained or improved. ACOs do not pay doctors or hospitals more unless high quality is demonstrated.

ACO Quality Measures and Hospitalists

Most of the 33 quality measures required by Medicare ACOs are based in ambulatory practice. These include measures related to blood pressure, immunizations, cancer, and fall-risk screening, and measures for diabetics, such as lipids and hemoglobin A1C. However, there are a few measures for which hospitalists should share in accountability, including:

- All-cause hospital readmission rate—risk-standardized;

- Ambulatory sensitive condition hospital admission rates (CHF, COPD); and

- Medication reconciliation after discharge from an inpatient facility.

Four Key Actions for Hospitalists

Hospitalists make a significant contribution to the quality and the financial performance of ACOs. In addition to the quality metrics cited above, hospitalists impact the inpatient portion of the overall population’s cost of care. Furthermore, hospitalists are vital partners in the care coordination required for an ACO to be successful.

Here are four actions I suggest taking in order for your hospitalist group to be effective as participants in an ACO:

- Have a representative from your group participate in ACO committees that address hospital utilization and related matters, such as care coordination impacting pre- and post-hospital care.

- Learn how to work with ACO case managers on care transitions, including post-discharge follow-up and information transfer.

- Understand an ACO’s approach to engagement of and coordination with post-acute-care facilities. The ability of a post-acute facility, such a skilled nursing facility, to accept patients who have complex care needs, to manage changes in condition in the facility when appropriate, and to send complete information upon transfer to the hospital are important strategies for an ACO’s success.

- Understand how an ACO reports quality and cost performance and how savings will be shared among participants.

Mindset Change

If hospitalists are part of the chain of ACO physicians and providers held accountable for the health of a population of patients, we must work more closely with the medical home/neighborhood, post-acute-care facilities, and home-care providers. The change in mindset will occur only if we have a set of tools to get the job done, such as case managers and information technology, and the appropriate incentives to support better care coordination. I encourage my fellow hospitalists to make things happen, instead of taking a passive role in this monumental transformation.

Reference

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

From informal polls I’ve recently conducted of hospitalists, many are not even aware they are part of an accountable-care organization (ACO). And if they are aware, they might not be engaging in meaningful dialogue with ACO leaders about their role in these organizations. But, in the long term, ACOs will need to bring hospitalists to the table in order to be successful.

Are You Part of an ACO?

David Muhlestein, who blogs for Health Affairs, tracks the growth of ACOs around the country. He states that, as of Jan. 31, there were 428 ACOs in the U.S. (see Figure 1).1 In terms of numbers, Florida, Texas, and California lead the nation with 42, 33, and 46 ACOs, respectively. So it is likely that you are part of an ACO. If you are unsure, ask your chief medical officer or president of the medical staff.

How ACOs Work

All ACOs seek to manage a group, or population, of patients as efficiently as possible while maintaining or improving quality of care. For Medicare ACOs, the goal is to bring together hospitals and physicians in order to share savings derived from efficiencies in care. But before any savings can be shared, the Medicare ACO must demonstrate that it achieved high-quality care across four domains, totaling 33 individual quality measures. (see Table 1)

Main Flavors of ACOs

There are two types of ACOs: private ACOs and Medicare ACOs. Prior to Medicare ACOs, which were launched in January 2012, there were 150 private-sector ACOs, and this number continues to grow. Private ACOs represent a heterogeneous group in terms of reimbursement model. Some operate under shared savings programs; others use full or partial capitation, bundled payments, and/or other types of arrangements. But nearly all ACOs operate under the premise that the incentives used to make care more efficient and less costly can only be applied if measurable quality is maintained or improved. ACOs do not pay doctors or hospitals more unless high quality is demonstrated.

ACO Quality Measures and Hospitalists

Most of the 33 quality measures required by Medicare ACOs are based in ambulatory practice. These include measures related to blood pressure, immunizations, cancer, and fall-risk screening, and measures for diabetics, such as lipids and hemoglobin A1C. However, there are a few measures for which hospitalists should share in accountability, including:

- All-cause hospital readmission rate—risk-standardized;

- Ambulatory sensitive condition hospital admission rates (CHF, COPD); and

- Medication reconciliation after discharge from an inpatient facility.

Four Key Actions for Hospitalists

Hospitalists make a significant contribution to the quality and the financial performance of ACOs. In addition to the quality metrics cited above, hospitalists impact the inpatient portion of the overall population’s cost of care. Furthermore, hospitalists are vital partners in the care coordination required for an ACO to be successful.

Here are four actions I suggest taking in order for your hospitalist group to be effective as participants in an ACO:

- Have a representative from your group participate in ACO committees that address hospital utilization and related matters, such as care coordination impacting pre- and post-hospital care.

- Learn how to work with ACO case managers on care transitions, including post-discharge follow-up and information transfer.

- Understand an ACO’s approach to engagement of and coordination with post-acute-care facilities. The ability of a post-acute facility, such a skilled nursing facility, to accept patients who have complex care needs, to manage changes in condition in the facility when appropriate, and to send complete information upon transfer to the hospital are important strategies for an ACO’s success.

- Understand how an ACO reports quality and cost performance and how savings will be shared among participants.

Mindset Change

If hospitalists are part of the chain of ACO physicians and providers held accountable for the health of a population of patients, we must work more closely with the medical home/neighborhood, post-acute-care facilities, and home-care providers. The change in mindset will occur only if we have a set of tools to get the job done, such as case managers and information technology, and the appropriate incentives to support better care coordination. I encourage my fellow hospitalists to make things happen, instead of taking a passive role in this monumental transformation.

Reference

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

Win Whitcomb: Front-Line Hospitalists Fight Against Health Care-Associated Infections (HAIs)

2013 marks a turning point in the way hospitals are held accountable for the prevention of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs). It has been known for some time that HAIs are a serious cause of morbidity, with 1 in 20 hospital patients in the U.S. acquiring one. That represents 1.7 million Americans and accounts for about 100,000 lives lost each year. On a personal note, my father died of an HAI after surgery in 2000.

Now, with the Affordable Care Act coming into full swing, hospitals must get serious about preventing HAIs. This presents a major opportunity for hospitalists. There are three ways that hospitals will be affected:

- Since 2008, hospitals have not been reimbursed at a higher rate for vascular catheter-associated infections, catheter-associated urinary tract infections (UTIs), or surgical-site infections when acquired in the hospital.

- Over the next few years, Medicare’s Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (HVBP) program will begin to pay hospitals more or less, depending on how they perform, on six HAIs.

- Beginning in October 2014, in a roll-up measure for hospital-acquired conditions (which include infections), the worst-performing quartile of U.S. hospitals will be penalized 1% of their Medicare inpatient payments (see Table 1, below).

There are six HAIs that will be increasingly tied to hospital reimbursement. Each can be partially or completely prevented based on sets of practices, or care bundles, that require teamwork both in the planning stages and at the bedside. And, of course, the single most important way to reduce the spread of HAIs is to clean your hands before and after each patient encounter.

Clostridium-Difficile-Associated Disease (CDAD)

It is likely that your hospital has some type of CDAD prevention program. Here are a few things to keep in mind for CDAD prevention:

- Avoid alcohol-based hand rubs, because they do not kill C. diff spores. Vigorous hand washing with soap and water is the best approach.

- Use clindamycin, fluoroquinolones, and third-generation cephalosporins judiciously, as their restriction has been associated with reduced rates of CDAD.

- Place patients with suspected or proven C. diff infection on contact precautions, including gloves and gowns.

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA)

This includes hospital-acquired MRSA bacteremia. This topic will be discussed in future columns. Approaches to prevention include hand hygiene, cohorting patients, effective environmental cleaning, and antibiotic stewardship.

Central-Line-Associated Bloodstream Infection (CLABSI)

Adherence to the central-line insertion bundle has been conclusively shown to prevent CLABSI. It will become a process measure for HVBP in the near future. Prevention measures include hand hygiene, maximal barrier precautions during insertion, skin antisepsis with chlorhexidine, avoidance of the femoral vein, and daily assessment for readiness to discontinue the central line (which should involve every hospitalist).

Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection (CAUTI)

CAUTI has been mentioned frequently in this column, and for good reason: It is the most common HAI. Although the evidence supporting practices that prevent CAUTI is not as strong as for CLABSI, every institution should have a bundle of practices embedded in nurses’ and doctors’ workflow to prevent CAUTI (see “Quality Meets Finance,” January 2013, p. 31).

Surgical-Site Infection (SSI)

For the most part, SSI can be left to the surgeons and other operating room professionals. However, with increasing involvement of hospitalists in surgical cases, we must have an understanding of how SSIs are prevented. The World Health Organization surgical checklist (www.who.int/patientsafety/safesurgery) is a great starting point for any organization.

Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia (VAP)

For hospitalists who provide critical care, adherence to a VAP prevention bundle includes:

- Elevation of the head of the bed;

- Daily “sedation vacation” and readiness to extubate;

- Oral care with chlorhexidine; and

- Peptic ulcer disease and venous thromboembolism prophylaxis.

In 2009, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) launched an action plan to prevent HAIs. As part of this effort, the Agency for Health Research and Quality (AHRQ) created a comprehensive unit-based safety program (CUSP) aimed at preventing CLABSI and CAUTI. The effort also focuses on safety culture and teamwork. For those interested in participating, visit www.onthecuspstophai.org.

Another way to get involved is to work Partnership for Patients, a public-private partnership led by HHS (http://partnershipforpatients.cms.gov), if a team at your hospital is participating. The Partnership for Patients seeks to reduce harm, including HAIs, by 40% by the end of 2013 compared with a 2010 baseline.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

2013 marks a turning point in the way hospitals are held accountable for the prevention of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs). It has been known for some time that HAIs are a serious cause of morbidity, with 1 in 20 hospital patients in the U.S. acquiring one. That represents 1.7 million Americans and accounts for about 100,000 lives lost each year. On a personal note, my father died of an HAI after surgery in 2000.

Now, with the Affordable Care Act coming into full swing, hospitals must get serious about preventing HAIs. This presents a major opportunity for hospitalists. There are three ways that hospitals will be affected:

- Since 2008, hospitals have not been reimbursed at a higher rate for vascular catheter-associated infections, catheter-associated urinary tract infections (UTIs), or surgical-site infections when acquired in the hospital.

- Over the next few years, Medicare’s Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (HVBP) program will begin to pay hospitals more or less, depending on how they perform, on six HAIs.

- Beginning in October 2014, in a roll-up measure for hospital-acquired conditions (which include infections), the worst-performing quartile of U.S. hospitals will be penalized 1% of their Medicare inpatient payments (see Table 1, below).

There are six HAIs that will be increasingly tied to hospital reimbursement. Each can be partially or completely prevented based on sets of practices, or care bundles, that require teamwork both in the planning stages and at the bedside. And, of course, the single most important way to reduce the spread of HAIs is to clean your hands before and after each patient encounter.

Clostridium-Difficile-Associated Disease (CDAD)

It is likely that your hospital has some type of CDAD prevention program. Here are a few things to keep in mind for CDAD prevention:

- Avoid alcohol-based hand rubs, because they do not kill C. diff spores. Vigorous hand washing with soap and water is the best approach.

- Use clindamycin, fluoroquinolones, and third-generation cephalosporins judiciously, as their restriction has been associated with reduced rates of CDAD.

- Place patients with suspected or proven C. diff infection on contact precautions, including gloves and gowns.

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA)

This includes hospital-acquired MRSA bacteremia. This topic will be discussed in future columns. Approaches to prevention include hand hygiene, cohorting patients, effective environmental cleaning, and antibiotic stewardship.

Central-Line-Associated Bloodstream Infection (CLABSI)

Adherence to the central-line insertion bundle has been conclusively shown to prevent CLABSI. It will become a process measure for HVBP in the near future. Prevention measures include hand hygiene, maximal barrier precautions during insertion, skin antisepsis with chlorhexidine, avoidance of the femoral vein, and daily assessment for readiness to discontinue the central line (which should involve every hospitalist).

Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection (CAUTI)

CAUTI has been mentioned frequently in this column, and for good reason: It is the most common HAI. Although the evidence supporting practices that prevent CAUTI is not as strong as for CLABSI, every institution should have a bundle of practices embedded in nurses’ and doctors’ workflow to prevent CAUTI (see “Quality Meets Finance,” January 2013, p. 31).

Surgical-Site Infection (SSI)

For the most part, SSI can be left to the surgeons and other operating room professionals. However, with increasing involvement of hospitalists in surgical cases, we must have an understanding of how SSIs are prevented. The World Health Organization surgical checklist (www.who.int/patientsafety/safesurgery) is a great starting point for any organization.

Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia (VAP)

For hospitalists who provide critical care, adherence to a VAP prevention bundle includes:

- Elevation of the head of the bed;

- Daily “sedation vacation” and readiness to extubate;

- Oral care with chlorhexidine; and

- Peptic ulcer disease and venous thromboembolism prophylaxis.

In 2009, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) launched an action plan to prevent HAIs. As part of this effort, the Agency for Health Research and Quality (AHRQ) created a comprehensive unit-based safety program (CUSP) aimed at preventing CLABSI and CAUTI. The effort also focuses on safety culture and teamwork. For those interested in participating, visit www.onthecuspstophai.org.

Another way to get involved is to work Partnership for Patients, a public-private partnership led by HHS (http://partnershipforpatients.cms.gov), if a team at your hospital is participating. The Partnership for Patients seeks to reduce harm, including HAIs, by 40% by the end of 2013 compared with a 2010 baseline.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

2013 marks a turning point in the way hospitals are held accountable for the prevention of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs). It has been known for some time that HAIs are a serious cause of morbidity, with 1 in 20 hospital patients in the U.S. acquiring one. That represents 1.7 million Americans and accounts for about 100,000 lives lost each year. On a personal note, my father died of an HAI after surgery in 2000.

Now, with the Affordable Care Act coming into full swing, hospitals must get serious about preventing HAIs. This presents a major opportunity for hospitalists. There are three ways that hospitals will be affected:

- Since 2008, hospitals have not been reimbursed at a higher rate for vascular catheter-associated infections, catheter-associated urinary tract infections (UTIs), or surgical-site infections when acquired in the hospital.

- Over the next few years, Medicare’s Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (HVBP) program will begin to pay hospitals more or less, depending on how they perform, on six HAIs.

- Beginning in October 2014, in a roll-up measure for hospital-acquired conditions (which include infections), the worst-performing quartile of U.S. hospitals will be penalized 1% of their Medicare inpatient payments (see Table 1, below).

There are six HAIs that will be increasingly tied to hospital reimbursement. Each can be partially or completely prevented based on sets of practices, or care bundles, that require teamwork both in the planning stages and at the bedside. And, of course, the single most important way to reduce the spread of HAIs is to clean your hands before and after each patient encounter.

Clostridium-Difficile-Associated Disease (CDAD)

It is likely that your hospital has some type of CDAD prevention program. Here are a few things to keep in mind for CDAD prevention:

- Avoid alcohol-based hand rubs, because they do not kill C. diff spores. Vigorous hand washing with soap and water is the best approach.

- Use clindamycin, fluoroquinolones, and third-generation cephalosporins judiciously, as their restriction has been associated with reduced rates of CDAD.

- Place patients with suspected or proven C. diff infection on contact precautions, including gloves and gowns.

Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA)

This includes hospital-acquired MRSA bacteremia. This topic will be discussed in future columns. Approaches to prevention include hand hygiene, cohorting patients, effective environmental cleaning, and antibiotic stewardship.

Central-Line-Associated Bloodstream Infection (CLABSI)

Adherence to the central-line insertion bundle has been conclusively shown to prevent CLABSI. It will become a process measure for HVBP in the near future. Prevention measures include hand hygiene, maximal barrier precautions during insertion, skin antisepsis with chlorhexidine, avoidance of the femoral vein, and daily assessment for readiness to discontinue the central line (which should involve every hospitalist).

Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection (CAUTI)

CAUTI has been mentioned frequently in this column, and for good reason: It is the most common HAI. Although the evidence supporting practices that prevent CAUTI is not as strong as for CLABSI, every institution should have a bundle of practices embedded in nurses’ and doctors’ workflow to prevent CAUTI (see “Quality Meets Finance,” January 2013, p. 31).

Surgical-Site Infection (SSI)

For the most part, SSI can be left to the surgeons and other operating room professionals. However, with increasing involvement of hospitalists in surgical cases, we must have an understanding of how SSIs are prevented. The World Health Organization surgical checklist (www.who.int/patientsafety/safesurgery) is a great starting point for any organization.

Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia (VAP)

For hospitalists who provide critical care, adherence to a VAP prevention bundle includes:

- Elevation of the head of the bed;

- Daily “sedation vacation” and readiness to extubate;

- Oral care with chlorhexidine; and

- Peptic ulcer disease and venous thromboembolism prophylaxis.

In 2009, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) launched an action plan to prevent HAIs. As part of this effort, the Agency for Health Research and Quality (AHRQ) created a comprehensive unit-based safety program (CUSP) aimed at preventing CLABSI and CAUTI. The effort also focuses on safety culture and teamwork. For those interested in participating, visit www.onthecuspstophai.org.

Another way to get involved is to work Partnership for Patients, a public-private partnership led by HHS (http://partnershipforpatients.cms.gov), if a team at your hospital is participating. The Partnership for Patients seeks to reduce harm, including HAIs, by 40% by the end of 2013 compared with a 2010 baseline.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

Bob Wachter Puts Forward Spin on Patient Safety, Quality of Care at HM13

Most hospitalists have heard the adage “If you’ve seen one hospitalist group, you’ve seen one hospitalist group.” Another HM truism is “If you’ve seen one SHM annual meeting, then you’ve seen Bob Wachter, MD, MHM.”

Dr. Wachter, professor, chief of the division of hospital medicine, and chief of the medical service at the University of California at San Francisco Medical Center, is to HM conventions as warfarin is to anticoagulation. His keynote address is the finale to the yearly confab, and HM13’s version is scheduled for noon May 19 at the Gaylord National Harbor Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md.

This year’s address is titled “Quality, Safety, and IT: A Decade of Successes, Failures, Surprises, and Epiphanies.” Dr. Wachter spoke recently with The Hospitalist about his annual tradition.

Question: With your interest in the intersection between healthcare and politics, to be back in D.C. has to be something enjoyable for you to write and talk about.

Answer: It’s a very interesting time in the life of healthcare, in that now that everybody knows that the [Affordable Care Act] is real and not going away, and we’re actually beginning to implement parts of it, you can kind of see what the future is going to look like, and everybody’s responding. And there are parts of that that are very exciting, because they’re forcing us to think about value in new ways. [And] there are parts of it that are somewhat frustrating.

Q: Does that give the hospitalist community the chance to ride herd on more global issues?

A: I think that’s the most optimistic interpretation—that we stick to our knitting, that we continue to be the leaders in improvement, and eventually all of the deals will be done, lawyers will be dismissed, and people will turn back to focusing on performance and say to us, “Thank goodness you’ve been doing this work, because now we realize that it’s not just about contracts; it’s about how we deliver care, and you’re the ones that have been leading the way.”

Q: What’s the most realistic interpretation?

A: This work gets less attention and less support than it needs. … I think we’re going to go through three to five years where we’re continuing to do the work. It’s really important—in many ways, it’s as important as growing—but as its importance is growing, the importance of other things that require more tending-to by the senior leadership is growing even faster. The risk is that there will be a disconnect.

Q: When you see the literature that suggests just how difficult the nuts and bolts implementation of reform is, what message do you want to get across to the people who are going to be listening, in terms of actually implementing all of this?

A: The message I don’t want to get across is “frustration, burnout, and it’s not worth it.” The endgame is worth it. The endgame is not even elective. We have to get to a place where we’re delivering higher-quality, safer, more satisfying care to patients at a lower cost. We’re in a unique position to deliver on that promise. … This is really tough stuff, and it takes time and it takes learning.

Check out our 6-minute feature video: "Five Reasons You Should Attend HM13"

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Most hospitalists have heard the adage “If you’ve seen one hospitalist group, you’ve seen one hospitalist group.” Another HM truism is “If you’ve seen one SHM annual meeting, then you’ve seen Bob Wachter, MD, MHM.”

Dr. Wachter, professor, chief of the division of hospital medicine, and chief of the medical service at the University of California at San Francisco Medical Center, is to HM conventions as warfarin is to anticoagulation. His keynote address is the finale to the yearly confab, and HM13’s version is scheduled for noon May 19 at the Gaylord National Harbor Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md.

This year’s address is titled “Quality, Safety, and IT: A Decade of Successes, Failures, Surprises, and Epiphanies.” Dr. Wachter spoke recently with The Hospitalist about his annual tradition.

Question: With your interest in the intersection between healthcare and politics, to be back in D.C. has to be something enjoyable for you to write and talk about.

Answer: It’s a very interesting time in the life of healthcare, in that now that everybody knows that the [Affordable Care Act] is real and not going away, and we’re actually beginning to implement parts of it, you can kind of see what the future is going to look like, and everybody’s responding. And there are parts of that that are very exciting, because they’re forcing us to think about value in new ways. [And] there are parts of it that are somewhat frustrating.

Q: Does that give the hospitalist community the chance to ride herd on more global issues?

A: I think that’s the most optimistic interpretation—that we stick to our knitting, that we continue to be the leaders in improvement, and eventually all of the deals will be done, lawyers will be dismissed, and people will turn back to focusing on performance and say to us, “Thank goodness you’ve been doing this work, because now we realize that it’s not just about contracts; it’s about how we deliver care, and you’re the ones that have been leading the way.”

Q: What’s the most realistic interpretation?

A: This work gets less attention and less support than it needs. … I think we’re going to go through three to five years where we’re continuing to do the work. It’s really important—in many ways, it’s as important as growing—but as its importance is growing, the importance of other things that require more tending-to by the senior leadership is growing even faster. The risk is that there will be a disconnect.

Q: When you see the literature that suggests just how difficult the nuts and bolts implementation of reform is, what message do you want to get across to the people who are going to be listening, in terms of actually implementing all of this?

A: The message I don’t want to get across is “frustration, burnout, and it’s not worth it.” The endgame is worth it. The endgame is not even elective. We have to get to a place where we’re delivering higher-quality, safer, more satisfying care to patients at a lower cost. We’re in a unique position to deliver on that promise. … This is really tough stuff, and it takes time and it takes learning.

Check out our 6-minute feature video: "Five Reasons You Should Attend HM13"

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Most hospitalists have heard the adage “If you’ve seen one hospitalist group, you’ve seen one hospitalist group.” Another HM truism is “If you’ve seen one SHM annual meeting, then you’ve seen Bob Wachter, MD, MHM.”

Dr. Wachter, professor, chief of the division of hospital medicine, and chief of the medical service at the University of California at San Francisco Medical Center, is to HM conventions as warfarin is to anticoagulation. His keynote address is the finale to the yearly confab, and HM13’s version is scheduled for noon May 19 at the Gaylord National Harbor Resort & Convention Center in National Harbor, Md.

This year’s address is titled “Quality, Safety, and IT: A Decade of Successes, Failures, Surprises, and Epiphanies.” Dr. Wachter spoke recently with The Hospitalist about his annual tradition.

Question: With your interest in the intersection between healthcare and politics, to be back in D.C. has to be something enjoyable for you to write and talk about.

Answer: It’s a very interesting time in the life of healthcare, in that now that everybody knows that the [Affordable Care Act] is real and not going away, and we’re actually beginning to implement parts of it, you can kind of see what the future is going to look like, and everybody’s responding. And there are parts of that that are very exciting, because they’re forcing us to think about value in new ways. [And] there are parts of it that are somewhat frustrating.

Q: Does that give the hospitalist community the chance to ride herd on more global issues?

A: I think that’s the most optimistic interpretation—that we stick to our knitting, that we continue to be the leaders in improvement, and eventually all of the deals will be done, lawyers will be dismissed, and people will turn back to focusing on performance and say to us, “Thank goodness you’ve been doing this work, because now we realize that it’s not just about contracts; it’s about how we deliver care, and you’re the ones that have been leading the way.”

Q: What’s the most realistic interpretation?

A: This work gets less attention and less support than it needs. … I think we’re going to go through three to five years where we’re continuing to do the work. It’s really important—in many ways, it’s as important as growing—but as its importance is growing, the importance of other things that require more tending-to by the senior leadership is growing even faster. The risk is that there will be a disconnect.

Q: When you see the literature that suggests just how difficult the nuts and bolts implementation of reform is, what message do you want to get across to the people who are going to be listening, in terms of actually implementing all of this?

A: The message I don’t want to get across is “frustration, burnout, and it’s not worth it.” The endgame is worth it. The endgame is not even elective. We have to get to a place where we’re delivering higher-quality, safer, more satisfying care to patients at a lower cost. We’re in a unique position to deliver on that promise. … This is really tough stuff, and it takes time and it takes learning.

Check out our 6-minute feature video: "Five Reasons You Should Attend HM13"

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: The Medical Director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness Spotlights Hospitalist Communication, Attention to Discharge Details

Click here to listen to Dr. Duckworth

Click here to listen to Dr. Duckworth

Click here to listen to Dr. Duckworth

Robotic Vaporizers Reduce Hospital Bacterial Infections

Paired, robotlike devices that disperse a bleaching disinfectant into the air of hospital rooms, then detoxify the disinfecting chemical, were found to be highly effective at killing and preventing the spread of “superbug” bacteria, according to research from Johns Hopkins Hospital published in Clinical Infectious Diseases.5 Hydrogen peroxide vaporizers were first deployed in Singapore hospitals in 2002 during an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS).

Almost half of a study group of 6,350 patients in and out of 180 hospital rooms over a two-and-a-half-year period received the enhanced cleaning technology, while the others received routine cleaning only. Manufactured by Bioquell Inc. of Horsham, Pa. (www.bioquell.com), each device is about the size of a washing machine. They were deployed in hospital rooms with sealed vents, dispersing a thin film of hydrogen peroxide across all exposed surfaces, equipment, floors, and walls. This approach reduced by 64% the number of patients who later became contaminated with any of the most common drug-resistant organisms, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant enterococci, Clostridium difficile, and Acinetobacter baumannii.

Spreading the bleaching vapor this way “represents a major technological advance in preventing the spread of dangerous bacteria inside hospital rooms,” says senior investigator Trish Perl, MD, MSc, professor of medicine and an infectious disease specialist at Johns Hopkins. The hospital announced in December that it would begin decontaminating isolation rooms with these devices as standard practice starting in January.

Reference

Paired, robotlike devices that disperse a bleaching disinfectant into the air of hospital rooms, then detoxify the disinfecting chemical, were found to be highly effective at killing and preventing the spread of “superbug” bacteria, according to research from Johns Hopkins Hospital published in Clinical Infectious Diseases.5 Hydrogen peroxide vaporizers were first deployed in Singapore hospitals in 2002 during an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS).

Almost half of a study group of 6,350 patients in and out of 180 hospital rooms over a two-and-a-half-year period received the enhanced cleaning technology, while the others received routine cleaning only. Manufactured by Bioquell Inc. of Horsham, Pa. (www.bioquell.com), each device is about the size of a washing machine. They were deployed in hospital rooms with sealed vents, dispersing a thin film of hydrogen peroxide across all exposed surfaces, equipment, floors, and walls. This approach reduced by 64% the number of patients who later became contaminated with any of the most common drug-resistant organisms, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant enterococci, Clostridium difficile, and Acinetobacter baumannii.

Spreading the bleaching vapor this way “represents a major technological advance in preventing the spread of dangerous bacteria inside hospital rooms,” says senior investigator Trish Perl, MD, MSc, professor of medicine and an infectious disease specialist at Johns Hopkins. The hospital announced in December that it would begin decontaminating isolation rooms with these devices as standard practice starting in January.

Reference

Paired, robotlike devices that disperse a bleaching disinfectant into the air of hospital rooms, then detoxify the disinfecting chemical, were found to be highly effective at killing and preventing the spread of “superbug” bacteria, according to research from Johns Hopkins Hospital published in Clinical Infectious Diseases.5 Hydrogen peroxide vaporizers were first deployed in Singapore hospitals in 2002 during an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS).

Almost half of a study group of 6,350 patients in and out of 180 hospital rooms over a two-and-a-half-year period received the enhanced cleaning technology, while the others received routine cleaning only. Manufactured by Bioquell Inc. of Horsham, Pa. (www.bioquell.com), each device is about the size of a washing machine. They were deployed in hospital rooms with sealed vents, dispersing a thin film of hydrogen peroxide across all exposed surfaces, equipment, floors, and walls. This approach reduced by 64% the number of patients who later became contaminated with any of the most common drug-resistant organisms, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant enterococci, Clostridium difficile, and Acinetobacter baumannii.

Spreading the bleaching vapor this way “represents a major technological advance in preventing the spread of dangerous bacteria inside hospital rooms,” says senior investigator Trish Perl, MD, MSc, professor of medicine and an infectious disease specialist at Johns Hopkins. The hospital announced in December that it would begin decontaminating isolation rooms with these devices as standard practice starting in January.

Reference

Society of Hospital Medicine Launches Online Training Program for Hospitalists

Hospitalists play an increasingly pivotal role in ensuring the highest quality and safety for patients in hospitals. The implementation of healthcare reform has only heightened the importance of hospital quality and patient safety for hospitalists. To enable education and advancement of quality improvement (QI), SHM has developed the Hospital Quality & Patient Safety (HQPS) Online Academy (http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/hqps).

The HQPS Online Academy consists of Internet-based modules that provide training not included in traditional medical education. These modules bridge the gap between the conceptualization and practice of quality in hospitals, helping hospitalists to prepare and lead quality initiatives to improve patient outcomes. The modules allow healthcare providers to explore and evaluate current quality initiatives and practices, as well as reflect on ways to improve core measures within their hospital.

Each module focuses on a core principle of QI and patient safety, and provides three AMA PRA Category 1 credits.

SHM members who are insured with The Doctors Company can earn a 5% risk-management credit by completing the first five HQPS modules (see below). Eligible members also enjoy premium savings through a 5% program discount and a claims-free credit of up to 25%.

HQPS Online Academy modules

- Quality measurement and stakeholder interests

- Teamwork and communication

- Organizational knowledge and leadership skills

- Patient safety principles

- Quality and safety improvement methods and skills (RCA and FMEA)

Hospitalists play an increasingly pivotal role in ensuring the highest quality and safety for patients in hospitals. The implementation of healthcare reform has only heightened the importance of hospital quality and patient safety for hospitalists. To enable education and advancement of quality improvement (QI), SHM has developed the Hospital Quality & Patient Safety (HQPS) Online Academy (http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/hqps).

The HQPS Online Academy consists of Internet-based modules that provide training not included in traditional medical education. These modules bridge the gap between the conceptualization and practice of quality in hospitals, helping hospitalists to prepare and lead quality initiatives to improve patient outcomes. The modules allow healthcare providers to explore and evaluate current quality initiatives and practices, as well as reflect on ways to improve core measures within their hospital.

Each module focuses on a core principle of QI and patient safety, and provides three AMA PRA Category 1 credits.

SHM members who are insured with The Doctors Company can earn a 5% risk-management credit by completing the first five HQPS modules (see below). Eligible members also enjoy premium savings through a 5% program discount and a claims-free credit of up to 25%.

HQPS Online Academy modules

- Quality measurement and stakeholder interests

- Teamwork and communication

- Organizational knowledge and leadership skills

- Patient safety principles

- Quality and safety improvement methods and skills (RCA and FMEA)

Hospitalists play an increasingly pivotal role in ensuring the highest quality and safety for patients in hospitals. The implementation of healthcare reform has only heightened the importance of hospital quality and patient safety for hospitalists. To enable education and advancement of quality improvement (QI), SHM has developed the Hospital Quality & Patient Safety (HQPS) Online Academy (http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/hqps).

The HQPS Online Academy consists of Internet-based modules that provide training not included in traditional medical education. These modules bridge the gap between the conceptualization and practice of quality in hospitals, helping hospitalists to prepare and lead quality initiatives to improve patient outcomes. The modules allow healthcare providers to explore and evaluate current quality initiatives and practices, as well as reflect on ways to improve core measures within their hospital.

Each module focuses on a core principle of QI and patient safety, and provides three AMA PRA Category 1 credits.

SHM members who are insured with The Doctors Company can earn a 5% risk-management credit by completing the first five HQPS modules (see below). Eligible members also enjoy premium savings through a 5% program discount and a claims-free credit of up to 25%.

HQPS Online Academy modules

- Quality measurement and stakeholder interests

- Teamwork and communication

- Organizational knowledge and leadership skills

- Patient safety principles

- Quality and safety improvement methods and skills (RCA and FMEA)

Choosing Wisely Campaign Initiatives Grounded in Tenets of Hospital Medicine

The Choosing Wisely campaign is focused on better decision-making, improved quality, and decreased healthcare costs. Such focus on efficiency and cost-effectiveness also was part of the initial motivation for developing hospital medicine, says one of HM’s pioneering doctors.

Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, who heads the division of hospital medicine at the University of California at San Francisco, compares the current national obsession about healthcare waste with the medical quality and patient safety movements of the past decade.

“It’s the right time, the right message, and the right messenger,” says Dr. Wachter, who also chairs the American Board of Internal Medicine and sits on the board of the ABIM Foundation. “We’re a little scared about raised expectations. Delivering on them is going to be more difficult, even, than patient safety was, because ultimately it will require curtailing some income streams. You can’t reach the final outcome of cutting costs in healthcare without someone making less money.”

Dr. Wachter expects the medical community to hear “similar kinds of drumbeats about waste” from every corner of healthcare. “I think hospitalists should be active and enthusiastic partners in the Choosing Wisely campaign,” he says, “and leaders in American healthcare’s efforts to figure out how to purge waste from the system and decrease unnecessary expense.

The Choosing Wisely campaign is focused on better decision-making, improved quality, and decreased healthcare costs. Such focus on efficiency and cost-effectiveness also was part of the initial motivation for developing hospital medicine, says one of HM’s pioneering doctors.

Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, who heads the division of hospital medicine at the University of California at San Francisco, compares the current national obsession about healthcare waste with the medical quality and patient safety movements of the past decade.

“It’s the right time, the right message, and the right messenger,” says Dr. Wachter, who also chairs the American Board of Internal Medicine and sits on the board of the ABIM Foundation. “We’re a little scared about raised expectations. Delivering on them is going to be more difficult, even, than patient safety was, because ultimately it will require curtailing some income streams. You can’t reach the final outcome of cutting costs in healthcare without someone making less money.”

Dr. Wachter expects the medical community to hear “similar kinds of drumbeats about waste” from every corner of healthcare. “I think hospitalists should be active and enthusiastic partners in the Choosing Wisely campaign,” he says, “and leaders in American healthcare’s efforts to figure out how to purge waste from the system and decrease unnecessary expense.

The Choosing Wisely campaign is focused on better decision-making, improved quality, and decreased healthcare costs. Such focus on efficiency and cost-effectiveness also was part of the initial motivation for developing hospital medicine, says one of HM’s pioneering doctors.

Robert Wachter, MD, MHM, who heads the division of hospital medicine at the University of California at San Francisco, compares the current national obsession about healthcare waste with the medical quality and patient safety movements of the past decade.

“It’s the right time, the right message, and the right messenger,” says Dr. Wachter, who also chairs the American Board of Internal Medicine and sits on the board of the ABIM Foundation. “We’re a little scared about raised expectations. Delivering on them is going to be more difficult, even, than patient safety was, because ultimately it will require curtailing some income streams. You can’t reach the final outcome of cutting costs in healthcare without someone making less money.”

Dr. Wachter expects the medical community to hear “similar kinds of drumbeats about waste” from every corner of healthcare. “I think hospitalists should be active and enthusiastic partners in the Choosing Wisely campaign,” he says, “and leaders in American healthcare’s efforts to figure out how to purge waste from the system and decrease unnecessary expense.

Hospitalwide Reductions in Pediatric Patient Harm are Achievable

Clinical question: Can a broadly constructed improvement initiative significantly reduce serious safety events (SSEs)?

Study design: Single-institution quality-improvement initiative.

Setting: Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Synopsis: A multidisciplinary team supported by leadership was formed to reduce SSEs across the hospital by 80% within four years. A consulting firm with expertise in the field was also engaged for this process. Multifaceted interventions were clustered according to perceived key drivers of change in the institution: error prevention systems, improved safety governance, cause analysis programs, lessons-learned programs, and specific tactical interventions.

SSEs per 10,000 adjusted patient-days decreased significantly, to a mean of 0.3 from 0.9 (P<0.0001) after implementation, while days between SSEs increased to a mean of 55.2 from 19.4 (P<0.0001).

This work represents one of the most robust single-center approaches to improving patient safety that has been published to date. The authors attribute much of their success to culture change, which required “relentless clarity of vision by the organization.” Although this substantially limits immediate generalizability of any of the specific interventions, the work stands on its own as a prime example of what may be accomplished through focused dedication to reducing patient harm.

Bottom line: Patient harm is preventable through a widespread and multifaceted institutional initiative.

Citation: Muething SE, Goudie A, Schoettker PJ, et al. Quality improvement initiative to reduce serious safety events and improve patient safety culture. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e423-431.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Clinical question: Can a broadly constructed improvement initiative significantly reduce serious safety events (SSEs)?

Study design: Single-institution quality-improvement initiative.

Setting: Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Synopsis: A multidisciplinary team supported by leadership was formed to reduce SSEs across the hospital by 80% within four years. A consulting firm with expertise in the field was also engaged for this process. Multifaceted interventions were clustered according to perceived key drivers of change in the institution: error prevention systems, improved safety governance, cause analysis programs, lessons-learned programs, and specific tactical interventions.

SSEs per 10,000 adjusted patient-days decreased significantly, to a mean of 0.3 from 0.9 (P<0.0001) after implementation, while days between SSEs increased to a mean of 55.2 from 19.4 (P<0.0001).

This work represents one of the most robust single-center approaches to improving patient safety that has been published to date. The authors attribute much of their success to culture change, which required “relentless clarity of vision by the organization.” Although this substantially limits immediate generalizability of any of the specific interventions, the work stands on its own as a prime example of what may be accomplished through focused dedication to reducing patient harm.

Bottom line: Patient harm is preventable through a widespread and multifaceted institutional initiative.

Citation: Muething SE, Goudie A, Schoettker PJ, et al. Quality improvement initiative to reduce serious safety events and improve patient safety culture. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e423-431.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Clinical question: Can a broadly constructed improvement initiative significantly reduce serious safety events (SSEs)?

Study design: Single-institution quality-improvement initiative.

Setting: Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

Synopsis: A multidisciplinary team supported by leadership was formed to reduce SSEs across the hospital by 80% within four years. A consulting firm with expertise in the field was also engaged for this process. Multifaceted interventions were clustered according to perceived key drivers of change in the institution: error prevention systems, improved safety governance, cause analysis programs, lessons-learned programs, and specific tactical interventions.

SSEs per 10,000 adjusted patient-days decreased significantly, to a mean of 0.3 from 0.9 (P<0.0001) after implementation, while days between SSEs increased to a mean of 55.2 from 19.4 (P<0.0001).

This work represents one of the most robust single-center approaches to improving patient safety that has been published to date. The authors attribute much of their success to culture change, which required “relentless clarity of vision by the organization.” Although this substantially limits immediate generalizability of any of the specific interventions, the work stands on its own as a prime example of what may be accomplished through focused dedication to reducing patient harm.

Bottom line: Patient harm is preventable through a widespread and multifaceted institutional initiative.

Citation: Muething SE, Goudie A, Schoettker PJ, et al. Quality improvement initiative to reduce serious safety events and improve patient safety culture. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e423-431.

Reviewed by Pediatric Editor Mark Shen, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital medicine at Dell Children's Medical Center, Austin, Texas.

Post-Hospital Syndrome Contributes to Readmission Risk for Elderly

Post-hospital syndrome, as labeled in a recent, widely publicized opinion piece in the New England Journal of Medicine, is not a new concept, according to one hospitalist pioneer.1

Harlan Krumholz, MD, of the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn., writes in NEJM what others previously have described as “hospitalization-associated disability,” says Mark Williams, MD, MHM, chief of hospital medicine at Northwestern University School of Medicine and principal investigator of SHM’s Project BOOST (www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost).2

Dr. Krumholz found that the majority of 30-day readmissions for elderly patients with heart failure, pneumonia, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are for conditions other than the diagnosis named at discharge. He attributes this phenomenon to hospitalization-related sleep deprivation, malnourishment, pain and discomfort, cognition- and physical function-altering medications, deconditioning from bed rest or inactivity, and the experience of confronting stressful, mentally challenging situations in the hospital.1 Such stressors leave elderly patients with post-hospitalization disabilities comparable to a bad case of jet lag.

For Dr. Williams, the physical deterioration leading to rehospitalizations is better attributed to the underlying serious illness and comorbidities experienced by elderly patients—a kind of high-risk, post-illness syndrome. Prior research also has demonstrated the effects of bed rest for hospitalized elderly patients.

Regardless of the origins, is there anything hospitalists can do about this syndrome? “Absolutely,” Dr. Williams says. “Get elderly, hospitalized patients out of bed as quickly as possible, and be mindful of medications and their effects on elderly patients. But most hospitalists already think about these things when managing elderly patients.”

References

Post-hospital syndrome, as labeled in a recent, widely publicized opinion piece in the New England Journal of Medicine, is not a new concept, according to one hospitalist pioneer.1

Harlan Krumholz, MD, of the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn., writes in NEJM what others previously have described as “hospitalization-associated disability,” says Mark Williams, MD, MHM, chief of hospital medicine at Northwestern University School of Medicine and principal investigator of SHM’s Project BOOST (www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost).2

Dr. Krumholz found that the majority of 30-day readmissions for elderly patients with heart failure, pneumonia, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are for conditions other than the diagnosis named at discharge. He attributes this phenomenon to hospitalization-related sleep deprivation, malnourishment, pain and discomfort, cognition- and physical function-altering medications, deconditioning from bed rest or inactivity, and the experience of confronting stressful, mentally challenging situations in the hospital.1 Such stressors leave elderly patients with post-hospitalization disabilities comparable to a bad case of jet lag.

For Dr. Williams, the physical deterioration leading to rehospitalizations is better attributed to the underlying serious illness and comorbidities experienced by elderly patients—a kind of high-risk, post-illness syndrome. Prior research also has demonstrated the effects of bed rest for hospitalized elderly patients.

Regardless of the origins, is there anything hospitalists can do about this syndrome? “Absolutely,” Dr. Williams says. “Get elderly, hospitalized patients out of bed as quickly as possible, and be mindful of medications and their effects on elderly patients. But most hospitalists already think about these things when managing elderly patients.”

References

Post-hospital syndrome, as labeled in a recent, widely publicized opinion piece in the New England Journal of Medicine, is not a new concept, according to one hospitalist pioneer.1

Harlan Krumholz, MD, of the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn., writes in NEJM what others previously have described as “hospitalization-associated disability,” says Mark Williams, MD, MHM, chief of hospital medicine at Northwestern University School of Medicine and principal investigator of SHM’s Project BOOST (www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost).2

Dr. Krumholz found that the majority of 30-day readmissions for elderly patients with heart failure, pneumonia, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are for conditions other than the diagnosis named at discharge. He attributes this phenomenon to hospitalization-related sleep deprivation, malnourishment, pain and discomfort, cognition- and physical function-altering medications, deconditioning from bed rest or inactivity, and the experience of confronting stressful, mentally challenging situations in the hospital.1 Such stressors leave elderly patients with post-hospitalization disabilities comparable to a bad case of jet lag.

For Dr. Williams, the physical deterioration leading to rehospitalizations is better attributed to the underlying serious illness and comorbidities experienced by elderly patients—a kind of high-risk, post-illness syndrome. Prior research also has demonstrated the effects of bed rest for hospitalized elderly patients.

Regardless of the origins, is there anything hospitalists can do about this syndrome? “Absolutely,” Dr. Williams says. “Get elderly, hospitalized patients out of bed as quickly as possible, and be mindful of medications and their effects on elderly patients. But most hospitalists already think about these things when managing elderly patients.”

References

Hospital Medicine Experts Outline Criteria To Consider Before Growing Your Group

—Brian Hazen, MD, medical director, Inova Fairfax Hospital Group, Fairfax, Va.

Ilan Alhadeff, MD, SFHM, program medical director for Cogent HMG at Hackensack University Medical Center in Hackensack, N.J., pays a lot of attention to the work relative-value units (wRVUs) his hospitalists are producing and the number of encounters they’re tallying. But he’s not particularly worried about what he sees on a daily, weekly, or even monthly basis; he takes a monthslong view of his data when he wants to forecast whether he is going to need to think about adding staff.

“When you look at months, you can start seeing trends,” Dr. Alhadeff says. “Let’s say there’s 16 to 18 average encounters. If your average is 16, you’re saying, ‘OK, you’re on the lower end of your normal.’ And if your average is 18, you’re on the higher end of normal. But if you start seeing 18 every month, odds are you’re going to start getting to 19. So at that point, that’s raising the thought that we need to start thinking about bringing someone else on.”

It’s a dance HM group leaders around the country have to do when confronted with the age-old question: Should we expand our service? The answer is more art than science, experts say, as there is no standardized formula for knowing when your HM group should request more support from administration to add an FTE—or two or three. And, in a nod to the HM adage that if you’ve seen one HM group (HMG), then you’ve seen one HMG, the roadmap to expansion varies from place to place. But in a series of interviews with The Hospitalist, physicians, consultants, and management experts suggest there are broad themes that guide the process, including:

- Data. Dashboard metrics, such as average daily census (ADC), wRVUs, patient encounters, and length of stay (LOS), must be quantified. No discussion on expansion can be intelligibly made without a firm understanding of where a practice currently stands.

- Benchmarking. Collating figures isn’t enough. Measure your group against other local HMGs, regional groups, and national standards. SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report is a good place to start.

- Scope or schedule. Pushing into new business lines (e.g. orthopedic comanagement) often requires new staff, as does adding shifts to provide 24-hour on-site coverage. Those arguments are different from the case to be made for expanding based on increased patient encounters.

- Physician buy-in. Group leaders cannot unilaterally determine it’s time to add staff, particularly in small-group settings in which hiring a new physician means taking revenue away from the existing group, if only in the short term. Talk with group members before embarking on expansion. Keep track of physician turnover. If hospitalists are leaving often, it could be a sign the group is understaffed.

- Administrative buy-in. If a group leader’s request for a new hire comes without months of conversation ahead of it, it’s likely too late. Prepare C-suite executives in advance about potential growth needs so the discussion does not feel like a surprise.

- Know your market. Don’t wait until a new active-adult community floods the hospital with patients to begin analyzing the impact new residents might have. The same goes for companies that are bringing thousands of new workers to an area.

- Prepare to do nothing. Too often, group leaders think the easiest solution is hiring a physician to lessen workload. Instead, exhaust improved efficiency options and infrastructure improvements that could accomplish the same goal.

“There is no one specific measure,” says Burke Kealey, MD, SFHM, medical director of hospital specialties at HealthPartners Medical Group in St. Paul, Minn., and an SHM board member. “You have to look at it from several different aspects, and all or most need to line up and say that, yes, you could use more help.”

Practice Analysis

Dr. Kealey, board liaison to SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee, says that benchmarking might be among the most important first steps in determining the right time to grow a practice. Group leaders should keep in mind, though, that comparative analysis to outside measures is only step one of gauging a group’s performance.

“The external benchmarking is easy,” he says. “You can look at SHM survey data. There are a lot of places that will do local market surveys; that’s easy stuff to look at. It’s the internal stuff that’s a bit harder to make the case for, ‘OK, yes, I am a little below the national benchmarks, but here’s why.’”

In those instances, group leaders need to “look at the value equation” and engage hospital administrators in a discussion on why such metrics as wRVUs and ADC might not match local, regional, or national standards. Perhaps a hospital has a lower payor mix than the sample pool, or comparable regional institutions have a better mix of medical and surgical comanagement populations. Regardless of the details of the tailored explanation, the conversation must be one that’s ongoing between a group leader and the C-suite or it is likely to fail, Dr. Kealey says.

“It really gets to the partnership between the hospital and the hospitalist group and working together throughout the whole year, and not just looking at staffing needs, but looking at the hospital’s quality,” he adds. “It’s looking at [the hospital’s] ability to retain the surgeons and the specialists. It’s the leadership that you’re providing. It’s showing that you’re a real partner, so that when it does come time to make that value argument, that we need to grow...there is buy-in.

“If you’re not a true partner and you just come in as an adversary, I think your odds of success are not very high.”

Steve Sloan, MD, a partner at AIM Hospitalist Group of Westmont, Ill., says that group leaders would be wise to obtain input from all of their physicians before adding a new doctor, as each new hire impacts compensation for existing staff members. In Dr. Sloan’s 16-member group, 11 physicians are partners who discuss growth plans. The other doctors are on partnership tracks. And while that makes discussions more difficult than when nine physicians formed the group in 2007, up-front dialogue is crucial, Dr. Sloan says.

“We try to get all the partners together to make major decisions, such as hiring,” he says. “We don’t need everyone involved in every decision, but it’s not just one or two people making the decision.”

The conversation about growth also differs if new hires are needed to move the group into a new business line or if the group is adding staff to deal with its current patient load. Both require a business case for expansion to be made, but either way, codifying expectations with hospital clients is another way to streamline the growth process, says Dr. Alhadeff. His group contracts with his hospital to provide services and has the ability to autonomously add or delete staff as needed. Although personnel moves don’t require prior approval from the hospital, there is “an expected fiscal responsibility on our end and predetermined agreement do so.”

The group also keeps administrative stakeholders updated to make sure everyone is on the same page. Other groups might delineate in a contract what thresholds need to be met for expansion to be viable.

“It needs to be agreed upon,” Dr. Alhadeff says. “I like the flexibility of being able to determine within our company what we’re doing. But in answer to that, there are unintentional consequences. If we determine that we’re going to bring on someone else, and then we see after a few months that there is not enough volume to support this new physician, we could run into a problem. We will then have to make a financial decision, and the worst thing is to have to fire someone.”

Dr. Alhadeff also worries about the flipside: failing to hire when staff is overworked.

“We run that risk also,” he says. “We are walking a tightrope all the time, and we need to balance that tightrope.”

—Kenneth Hertz, FACMPE, principal, Medical Group Management Association Health Care Consulting Group, Denver

The Long View

Another tightrope is timing. Kenneth Hertz, FACMPE, principal of the Medical Group Management Association’s Health Care Consulting Group, says that it can take six months or longer to hire a physician, which means group leaders need to have a continual focus on whether growth is needed or will soon be needed. He suggests forecasting at least 12 to 18 months in advance to stay ahead of staffing needs.

Unfortunately, he says, analysis often gets put on hold in the shuffle of dealing with daily duties. “This is kind of generic to practice administrators, who are putting out fires almost every day. And when you’re putting out fires every day, you don’t have the luxury and the time to look out there and see what’s happening and know everything that’s going on,” he says. “They need to understand the importance of it and how all the pieces tie in together.”

Brian Hazen, MD, medical director of Inova Fairfax Hospital Group in Fairfax, Va., says an important approach is to realize growth isn’t always a good thing. HM group leaders often want to grow before they have stabilized their existing business lines, he says, and that can be the worst tack to take. He also notes that a group leader should ingratiate their program into the fabric of their hospital and not just rely on data to make the argument of the group’s value. That means putting hospitalists on committees, spearheading safety programs, and being seen as a partner in the institution.

“Job One is always patient safety and physician sanity,” he says. “If you are careful about growth and buy-in, and you do the committee work and support everybody so that you’re firmly entrenched in the hospital as a value, it’s much safer to grow. Growing for the sake of growing, you risk overexpansion, and that’s dangerous.”

Many hospitalist groups looking to grow will use locum tenens to bridge the staffing gap while they hire new employees (see “No Strings Attached,” December 2012, p. 36), but Dr. Hazen says without a longer view, that only serves as a Band-Aid.

Hertz, the consultant, often uses an analogy to show how important it is to be constantly planning ahead of the growth curve.

“It is a little bit like building roads,” he says. “Once you decide you need to add two lanes, by the time those are finished, you realize we really need to add two more lanes.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

—Brian Hazen, MD, medical director, Inova Fairfax Hospital Group, Fairfax, Va.

Ilan Alhadeff, MD, SFHM, program medical director for Cogent HMG at Hackensack University Medical Center in Hackensack, N.J., pays a lot of attention to the work relative-value units (wRVUs) his hospitalists are producing and the number of encounters they’re tallying. But he’s not particularly worried about what he sees on a daily, weekly, or even monthly basis; he takes a monthslong view of his data when he wants to forecast whether he is going to need to think about adding staff.

“When you look at months, you can start seeing trends,” Dr. Alhadeff says. “Let’s say there’s 16 to 18 average encounters. If your average is 16, you’re saying, ‘OK, you’re on the lower end of your normal.’ And if your average is 18, you’re on the higher end of normal. But if you start seeing 18 every month, odds are you’re going to start getting to 19. So at that point, that’s raising the thought that we need to start thinking about bringing someone else on.”

It’s a dance HM group leaders around the country have to do when confronted with the age-old question: Should we expand our service? The answer is more art than science, experts say, as there is no standardized formula for knowing when your HM group should request more support from administration to add an FTE—or two or three. And, in a nod to the HM adage that if you’ve seen one HM group (HMG), then you’ve seen one HMG, the roadmap to expansion varies from place to place. But in a series of interviews with The Hospitalist, physicians, consultants, and management experts suggest there are broad themes that guide the process, including:

- Data. Dashboard metrics, such as average daily census (ADC), wRVUs, patient encounters, and length of stay (LOS), must be quantified. No discussion on expansion can be intelligibly made without a firm understanding of where a practice currently stands.

- Benchmarking. Collating figures isn’t enough. Measure your group against other local HMGs, regional groups, and national standards. SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine report is a good place to start.

- Scope or schedule. Pushing into new business lines (e.g. orthopedic comanagement) often requires new staff, as does adding shifts to provide 24-hour on-site coverage. Those arguments are different from the case to be made for expanding based on increased patient encounters.

- Physician buy-in. Group leaders cannot unilaterally determine it’s time to add staff, particularly in small-group settings in which hiring a new physician means taking revenue away from the existing group, if only in the short term. Talk with group members before embarking on expansion. Keep track of physician turnover. If hospitalists are leaving often, it could be a sign the group is understaffed.

- Administrative buy-in. If a group leader’s request for a new hire comes without months of conversation ahead of it, it’s likely too late. Prepare C-suite executives in advance about potential growth needs so the discussion does not feel like a surprise.