User login

For MD-IQ only

Genetic differences by ancestry shouldn’t impact efficacy of prostate cancer therapies

, according to an analysis published in Clinical Cancer Research.

“[N]o significant differences were seen in clinically actionable DNA repair genes, MSI-high [microsatellite instability–high] status, and tumor mutation burden, suggesting that current therapeutic strategies may be equally beneficial in both populations,” wrote study author Yusuke Koga, of the Boston University, and colleagues.

“Since these findings suggest that the frequency of targetable genetic alterations is similar in patients of predominantly African versus European ancestry, offering comprehensive genomic profiling and biomarker-based therapies to all patients, including African American patients, is a critical component of promoting equity in the management of metastatic prostate cancer,” said Atish D. Choudhury, MD, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, who was not involved in this study.

Mr. Koga and colleagues noted that, when compared with European-American men, African American men have a higher incidence of prostate cancer, present with more advanced disease at an earlier age, and have increased mortality. These differences persist even after adjustment for socioeconomic covariates. That raises the question of the role of genetics.

“There is emerging evidence that, across some clinical trials and equal-access health systems, outcomes between AFR [African-American] men and European-American men with prostate cancer are similar,” the investigators wrote. “Although these data suggest that disparities can be ameliorated, there is limited knowledge of the genomic alterations that differ between groups and that could impact clinical outcomes.”

Study details and results

To get a handle on the issue, the investigators performed a meta-analysis of tumors from 250 African American men and 611 European-American men to compare the frequencies of somatic alterations across datasets from the Cancer Genome Atlas, the African Ancestry prostate cancer cohort, and the Memorial Sloan Kettering–Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets panel.

The team also compared prostate cancer sequencing data from a commercial platform, the Foundation Medicine assay, from 436 African-American men and 3,018 European-American men.

In the meta-analysis, mutations in ZFHX3 and focal deletions in ETV3 were more common in tumors from African American men than in tumors from European-American men. Both genes are putative prostate cancer tumor suppressors, the investigators noted.

TP53 mutations, meanwhile, were associated with increasing Gleason scores in both groups, suggesting “that if TP53 mutations are found in low-grade disease, they may potentially indicate a more aggressive clinical trajectory,” the investigators wrote.

In the analysis with the commercial assay, MYC amplifications were more frequent in African American men with metastatic disease, raising “the possibility that MYC amplifications may also contribute to high-risk disease in this population,” the team wrote.

Deletions in PTEN and rearrangements in TMPRSS2-ERG were less frequent in tumors from African American men, but KMT2D truncations and CCND1 amplifications were more frequent.

“Higher expression of CCND1 has been implicated with perineural invasion in prostate cancer, an aggressive histological feature in prostate cancer. Truncating mutations in KMT2D have been reported in both localized and metastatic prostate cancer patients with unclear clinical significance,” the investigators noted.

“The genomic differences seen in genes such as MYC, ZFHX3, PTEN, and TMPRSS2-ERG suggest that different pathways of carcinogenesis may be active in AFR [African American] men, which could lead to further disparities if targeted therapies for some of these alterations become available,” the team wrote.

They noted that the meta-analysis was limited by the fact that some cohorts lacked matched tumors from European-American men, which limited the investigators’ ability to control for differences in region, clinical setting, or sequencing assay. Furthermore, age, tumor stage, and Gleason grade were unavailable in the cohort analyzed with the commercial assay.

This research was funded by the Department of Defense, the National Cancer Institute, and the Prostate Cancer Foundation. Two authors are employees of Foundation Medicine.

SOURCE: Koga Y et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2020 Jul 10. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-4112.

, according to an analysis published in Clinical Cancer Research.

“[N]o significant differences were seen in clinically actionable DNA repair genes, MSI-high [microsatellite instability–high] status, and tumor mutation burden, suggesting that current therapeutic strategies may be equally beneficial in both populations,” wrote study author Yusuke Koga, of the Boston University, and colleagues.

“Since these findings suggest that the frequency of targetable genetic alterations is similar in patients of predominantly African versus European ancestry, offering comprehensive genomic profiling and biomarker-based therapies to all patients, including African American patients, is a critical component of promoting equity in the management of metastatic prostate cancer,” said Atish D. Choudhury, MD, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, who was not involved in this study.

Mr. Koga and colleagues noted that, when compared with European-American men, African American men have a higher incidence of prostate cancer, present with more advanced disease at an earlier age, and have increased mortality. These differences persist even after adjustment for socioeconomic covariates. That raises the question of the role of genetics.

“There is emerging evidence that, across some clinical trials and equal-access health systems, outcomes between AFR [African-American] men and European-American men with prostate cancer are similar,” the investigators wrote. “Although these data suggest that disparities can be ameliorated, there is limited knowledge of the genomic alterations that differ between groups and that could impact clinical outcomes.”

Study details and results

To get a handle on the issue, the investigators performed a meta-analysis of tumors from 250 African American men and 611 European-American men to compare the frequencies of somatic alterations across datasets from the Cancer Genome Atlas, the African Ancestry prostate cancer cohort, and the Memorial Sloan Kettering–Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets panel.

The team also compared prostate cancer sequencing data from a commercial platform, the Foundation Medicine assay, from 436 African-American men and 3,018 European-American men.

In the meta-analysis, mutations in ZFHX3 and focal deletions in ETV3 were more common in tumors from African American men than in tumors from European-American men. Both genes are putative prostate cancer tumor suppressors, the investigators noted.

TP53 mutations, meanwhile, were associated with increasing Gleason scores in both groups, suggesting “that if TP53 mutations are found in low-grade disease, they may potentially indicate a more aggressive clinical trajectory,” the investigators wrote.

In the analysis with the commercial assay, MYC amplifications were more frequent in African American men with metastatic disease, raising “the possibility that MYC amplifications may also contribute to high-risk disease in this population,” the team wrote.

Deletions in PTEN and rearrangements in TMPRSS2-ERG were less frequent in tumors from African American men, but KMT2D truncations and CCND1 amplifications were more frequent.

“Higher expression of CCND1 has been implicated with perineural invasion in prostate cancer, an aggressive histological feature in prostate cancer. Truncating mutations in KMT2D have been reported in both localized and metastatic prostate cancer patients with unclear clinical significance,” the investigators noted.

“The genomic differences seen in genes such as MYC, ZFHX3, PTEN, and TMPRSS2-ERG suggest that different pathways of carcinogenesis may be active in AFR [African American] men, which could lead to further disparities if targeted therapies for some of these alterations become available,” the team wrote.

They noted that the meta-analysis was limited by the fact that some cohorts lacked matched tumors from European-American men, which limited the investigators’ ability to control for differences in region, clinical setting, or sequencing assay. Furthermore, age, tumor stage, and Gleason grade were unavailable in the cohort analyzed with the commercial assay.

This research was funded by the Department of Defense, the National Cancer Institute, and the Prostate Cancer Foundation. Two authors are employees of Foundation Medicine.

SOURCE: Koga Y et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2020 Jul 10. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-4112.

, according to an analysis published in Clinical Cancer Research.

“[N]o significant differences were seen in clinically actionable DNA repair genes, MSI-high [microsatellite instability–high] status, and tumor mutation burden, suggesting that current therapeutic strategies may be equally beneficial in both populations,” wrote study author Yusuke Koga, of the Boston University, and colleagues.

“Since these findings suggest that the frequency of targetable genetic alterations is similar in patients of predominantly African versus European ancestry, offering comprehensive genomic profiling and biomarker-based therapies to all patients, including African American patients, is a critical component of promoting equity in the management of metastatic prostate cancer,” said Atish D. Choudhury, MD, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, who was not involved in this study.

Mr. Koga and colleagues noted that, when compared with European-American men, African American men have a higher incidence of prostate cancer, present with more advanced disease at an earlier age, and have increased mortality. These differences persist even after adjustment for socioeconomic covariates. That raises the question of the role of genetics.

“There is emerging evidence that, across some clinical trials and equal-access health systems, outcomes between AFR [African-American] men and European-American men with prostate cancer are similar,” the investigators wrote. “Although these data suggest that disparities can be ameliorated, there is limited knowledge of the genomic alterations that differ between groups and that could impact clinical outcomes.”

Study details and results

To get a handle on the issue, the investigators performed a meta-analysis of tumors from 250 African American men and 611 European-American men to compare the frequencies of somatic alterations across datasets from the Cancer Genome Atlas, the African Ancestry prostate cancer cohort, and the Memorial Sloan Kettering–Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets panel.

The team also compared prostate cancer sequencing data from a commercial platform, the Foundation Medicine assay, from 436 African-American men and 3,018 European-American men.

In the meta-analysis, mutations in ZFHX3 and focal deletions in ETV3 were more common in tumors from African American men than in tumors from European-American men. Both genes are putative prostate cancer tumor suppressors, the investigators noted.

TP53 mutations, meanwhile, were associated with increasing Gleason scores in both groups, suggesting “that if TP53 mutations are found in low-grade disease, they may potentially indicate a more aggressive clinical trajectory,” the investigators wrote.

In the analysis with the commercial assay, MYC amplifications were more frequent in African American men with metastatic disease, raising “the possibility that MYC amplifications may also contribute to high-risk disease in this population,” the team wrote.

Deletions in PTEN and rearrangements in TMPRSS2-ERG were less frequent in tumors from African American men, but KMT2D truncations and CCND1 amplifications were more frequent.

“Higher expression of CCND1 has been implicated with perineural invasion in prostate cancer, an aggressive histological feature in prostate cancer. Truncating mutations in KMT2D have been reported in both localized and metastatic prostate cancer patients with unclear clinical significance,” the investigators noted.

“The genomic differences seen in genes such as MYC, ZFHX3, PTEN, and TMPRSS2-ERG suggest that different pathways of carcinogenesis may be active in AFR [African American] men, which could lead to further disparities if targeted therapies for some of these alterations become available,” the team wrote.

They noted that the meta-analysis was limited by the fact that some cohorts lacked matched tumors from European-American men, which limited the investigators’ ability to control for differences in region, clinical setting, or sequencing assay. Furthermore, age, tumor stage, and Gleason grade were unavailable in the cohort analyzed with the commercial assay.

This research was funded by the Department of Defense, the National Cancer Institute, and the Prostate Cancer Foundation. Two authors are employees of Foundation Medicine.

SOURCE: Koga Y et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2020 Jul 10. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-4112.

FROM CLINICAL CANCER RESEARCH

Hypercalcemia Is of Uncertain Significance in Patients With Advanced Adenocarcinoma of the Prostate

Hypercalcemia is found when the corrected serum calcium level is > 10.5 mg/dL.1 Its symptoms are not specific and may include polyuria, dehydration, polydipsia, anorexia, nausea and/or vomiting, constipation, and other central nervous system manifestations, including confusion, delirium, cognitive impairment, muscle weakness, psychotic symptoms, and even coma.1,2

Hypercalcemia has varied etiologies; however, malignancy-induced hypercalcemia is one of the most common causes. In the US, the most common causes of malignancy-induced hypercalcemia are primary tumors of the lung or breast, multiple myeloma (MM), squamous cell carcinoma of the head or neck, renal cancer, and ovarian cancer.1

Men with prostate cancer and bone metastasis have relatively worse prognosis than do patient with no metastasis.3 In a recent meta-analysis of patients with bone-involved castration-resistant prostate cancer, the median survival was 21 months.3

Hypercalcemia is a rare manifestation of prostate cancer. In a retrospective study conducted between 2009 and 2013 using the Oncology Services Comprehensive Electronic Records (OSCER) warehouse of electronic health records (EHR), the rates of malignancy-induced hypercalcemia were the lowest among patients with prostate cancer, ranging from 1.4 to 2.1%.1

We present this case to discuss different pathophysiologic mechanisms leading to hypercalcemia in a patient with prostate cancer with bone metastasis and to study the role of humoral and growth factors in the pathogenesis of the disease.

Case Presentation

An African American man aged 69 years presented to the emergency department (ED) with generalized weakness, fatigue, and lower extremities muscle weakness. He reported a 40-lb weight loss over the past 3 months, intermittent lower back pain, and a 50 pack-year smoking history. A physical examination suggested clinical signs of dehydration.

Laboratory test results indicated hypercalcemia, macrocytic anemia, and thrombocytopenia: calcium 15.8 mg/dL, serum albumin 4.1 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase 139 μ/L, blood urea nitrogen 55 mg/dL, creatinine 3.4 mg/dL (baseline 1.4-1.5 mg/dL), hemoglobin 8 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume 99.6 fL, and platelets 100,000/μL. The patient was admitted for hypercalcemia. His intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH) was suppressed at 16 pg/mL, phosphorous was 3.8 mg/dL, parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP) was < 0.74 pmol/L, vitamin D (25 hydroxy cholecalciferol) was mildly decreased at 17.2 ng/mL, and 1,25 dihydroxy cholecalciferol (calcitriol) was < 5.0 (normal range 20-79.3 pg/mL).

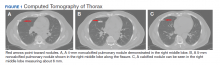

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest and abdomen was taken due to the patient’s heavy smoking history, an incidentally detected right lung base nodule on chest X-ray, and hypercalcemia. The CT scan showed multiple right middle lobe lung nodules with and without calcifications and calcified right hilar lymph nodes (Figure 1).

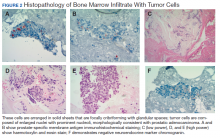

To evaluate the pancytopenia, a bone marrow biopsy was done, which showed that 80 to 90% of the marrow space was replaced by fibrosis and metastatic malignancy. Trilinear hematopoiesis was not seen (Figure 2). The tumor cells were positive for prostate- specific membrane antigen (PSMA) and negative for cytokeratin 7 and 20 (CK7 and CK20).4 The former is a membrane protein expressed on prostate tissues, including cancer; the latter is a form of protein used to identify adenocarcinoma of unknown primary origin (CK7 usually found in primary/ metastatic lung adenocarcinoma and CK20 usually in primary and some metastatic diseases of colon adenocarcinoma).5 A prostatic specific antigen (PSA) test was markedly elevated: 335.94 ng/mL (1.46 ng/mL on a previous 2011 test).

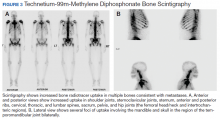

Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the prostate was diagnosed without a prostate biopsy. To determine the extent of bone metastases, a technetium-99m-methylene diphosphonate (MDP) bone scintigraphy demonstrated a superscan with intense foci of increased radiotracer uptake involving the bilateral shoulders, sternoclavicular joints, and sternum with heterogeneous uptake involving bilateral anterior and posterior ribs; cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spines; sacrum, pelvis, and bilateral hips, including the femoral head/neck and intertrochanteric regions. Also noted were several foci of radiotracer uptake involving the mandible and bilateral skull in the region of the temporomandibular joints (Figure 3).

The patient was initially treated with IV isotonic saline, followed by calcitonin and then pamidronate after kidney function improved. His calcium level responded to the therapy, and a plan was made by medical oncology to start androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) prior to discharge.

He was initially treated with bicalutamide, while a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist (leuprolide) was added 1 week later. Bicalutamide was then discontinued and a combined androgen blockade consisting of leuprolide, ketoconazole, and hydrocortisone was started. This therapy resulted in remission, and PSA declined to 1.73 ng/ mL 3 months later. At that time the patient enrolled in a clinical trial with leuprolide and bicalutamide combined therapy. About 6 months after his diagnosis, patient’s cancer progressed and became hormone refractory disease. At that time, bicalutamide was discontinued, and his therapy was switched to combined leuprolide and enzalutamide. After 6 months of therapy with enzalutamide, the patient’s cancer progressed again. He was later treated with docetaxel chemotherapy but died 16 months after diagnosis.

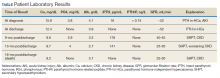

showed improvement of hypercalcemia at the time of discharge, but 9 months later and toward the time of expiration, our patient developed secondary hyperparathyroidism, with calcium maintained in the normal range, while iPTH was significantly elevated, a finding likely explained by a decline in kidney function and a fall in glomerular filtration rate (Table).

Discussion

Hypercalcemia in the setting of prostate cancer is a rare complication with an uncertain pathophysiology.6 Several mechanisms have been proposed for hypercalcemia of malignancy, these comprise humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy mediated by increased PTHrP; local osteolytic hypercalcemia with secretion of other humoral factors; excess extrarenal activation of vitamin D (1,25[OH]2D); PTH secretion, ectopic or primary; and multiple concurrent etiologies.7

PTHrP is the predominant mediator for hypercalcemia of malignancy and is estimated to account for 80% of hypercalcemia in patients with cancer. This protein shares a substantial sequence homology with PTH; in fact, 8 of the first 13 amino acids at the N-terminal portion of PTH were identical.8 PTHrP has multiple isoforms (PTHrP 141, PTHrP 139, and PTHrP 173). Like PTH, it enhances renal tubular reabsorption of calcium while increasing urinary phosphorus excretion.7 The result is both hypercalcemia and hypophosphatemia. However, unlike PTH, PTHrP does not increase 1,25(OH)2D and thus does not increase intestinal absorption of calcium and phosphorus. PTHrP acts on osteoblasts, leading to enhanced synthesis of receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL).7

In one study, PTHrP was detected immunohistochemically in prostate cancer cells. Iwamura and colleagues used 33 radical prostatectomy specimens from patients with clinically localized carcinoma of the prostate.9 None of these patients demonstrated hypercalcemia prior to the surgery. Using a mouse monoclonal antibody to an amino acid fragment, all cases demonstrated some degree of immunoreactivity throughout the cytoplasm of the tumor cells, but immunostaining was absent from inflammatory and stromal cells.9Furthermore, the intensity of the staining appeared to directly correlate with increasing tumor grade.9

Another study by Iwamura and colleagues suggested that PTHrP may play a significant role in the growth of prostate cancer by acting locally in an autocrine fashion.10 In this study, all prostate cancer cell lines from different sources expressed PTHrP immunoreactivity as well as evidence of DNA synthesis, the latter being measured by thymidine incorporation assay. Moreover, when these cells were incubated with various concentrations of mouse monoclonal antibody directed to PTHrP fragment, PTHrP-induced DNA synthesis was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner and almost completely neutralized at a specific concentration. Interestingly, the study demonstrated that cancer cell line derived from bone metastatic lesions secreted significantly greater amounts of PTHrP than did the cell line derived from the metastasis in the brain or in the lymph node. These findings suggest that PTHrP production may confer some advantage on the ability of prostate cancer cells to grow in bone.10

Ando and colleagues reported that neuroendocrine dedifferentiated prostate cancer can develop as a result of long-term ADT even after several years of therapy and has the potential to worsen and develop severe hypercalcemia.8 Neuron-specific enolase was used as the specific marker for the neuroendocrine cell, which suggested that the prostate cancer cell derived from the neuroendocrine cell might synthesize PTHrP and be responsible for the observed hypercalcemia.8

Other mechanisms cited for hypercalcemia of malignancy include other humoral factors associated with increased remodeling and comprise interleukin 1, 3, 6 (IL-1, IL-3, IL-6); tumor necrosis factor α; transforming growth factor A and B observed in metastatic bone lesions in breast cancer; lymphotoxin; E series prostaglandins; and macrophage inflammatory protein 1α seen in MM.

Local osteolytic hypercalcemia accounts for about 20% of cases and is usually associated with extensive bone metastases. It is most commonly seen in MM and metastatic breast cancer and less commonly in leukemia. The proposed mechanism is thought to be because of the release of local cytokines from the tumor, resulting in excess osteoclast activation and enhanced bone resorption often through RANK/RANKL interaction.

Extrarenal production of 1,25(OH)2D by the tumor accounts for about 1% of cases of hypercalcemia in malignancy. 1,25(OH)2D causes increased intestinal absorption of calcium and enhances osteolytic bone resorption, resulting in increased serum calcium. This mechanism is most commonly seen with Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma and had been reported in ovarian dysgerminoma.7

In our patient, bone imaging showed osteoblastic lesions, a finding that likely contrasts the local osteolytic bone destruction theory. PTHrP was not significantly elevated in the serum, and PTH levels ruled out any form of primary hyperparathyroidism. In addition, histopathology showed no evidence of mosaicism or neuroendocrine dedifferentiation.

Findings in aggregate tell us that an exact pathophysiologic mechanism leading to hypercalcemia in prostate cancer is still unclear and may involve an interplay between growth factors and possible osteolytic materials, yet it must be studied thoroughly.

Conclusions

Hypercalcemia in pure metastatic adenocarcinoma of prostate is a rare finding and is of uncertain significance. Some studies suggested a search for unusual histopathologies, including neuroendocrine cancer and neuroendocrine dedifferentiation.8,11 However, in adenocarcinoma alone, it has an uncertain pathophysiology that needs to be further studied. Studies needed to investigate the role of PTHrP as a growth factor for both prostate cancer cells and development of hypercalcemia and possibly target-directed monoclonal antibody therapies may need to be extensively researched.

1. Gastanaga VM, Schwartzberg LS, Jain RK, et al. Prevalence of hypercalcemia among cancer patients in the United States. Cancer Med. 2016;5(8):2091‐2100. doi:10.1002/cam4.749

2. Grill V, Martin TJ. Hypercalcemia of malignancy. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2000;1(4):253‐263. doi:10.1023/a:1026597816193

3. Halabi S, Kelly WK, Ma H, et al. Meta-analysis evaluating the impact of site of metastasis on overall survival in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(14):1652‐1659. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.65.7270

4. Chang SS. Overview of prostate-specific membrane antigen. Rev Urol. 2004;6(suppl 10):S13‐S18.

5. Kummar S, Fogarasi M, Canova A, Mota A, Ciesielski T. Cytokeratin 7 and 20 staining for the diagnosis of lung and colorectal adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2002;86(12):1884‐1887. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6600326

6. Avashia JH, Walsh TD, Thomas AJ Jr, Kaye M, Licata A. Metastatic carcinoma of the prostate with hypercalcemia [published correction appears in Cleve Clin J Med. 1991;58(3):284]. Cleve Clin J Med. 1990;57(7):636‐638. doi:10.3949/ccjm.57.7.636.

7. Goldner W. Cancer-related hypercalcemia. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(5):426‐432. doi:10.1200/JOP.2016.011155.

8. Ando T, Watanabe K, Mizusawa T, Katagiri A. Hypercalcemia due to parathyroid hormone-related peptide secreted by neuroendocrine dedifferentiated prostate cancer. Urol Case Rep. 2018;22:67‐69. doi:10.1016/j.eucr.2018.11.001

9. Iwamura M, di Sant’Agnese PA, Wu G, et al. Immunohistochemical localization of parathyroid hormonerelated protein in human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1993;53(8):1724‐1726.

10. Iwamura M, Abrahamsson PA, Foss KA, Wu G, Cockett AT, Deftos LJ. Parathyroid hormone-related protein: a potential autocrine growth regulator in human prostate cancer cell lines. Urology. 1994;43(5):675‐679. doi:10.1016/0090-4295(94)90183-x

11. Smith DC, Tucker JA, Trump DL. Hypercalcemia and neuroendocrine carcinoma of the prostate: a report of three cases and a review of the literature. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10(3):499‐505. doi:10.1200/JCO.1992.10.3.499.

Hypercalcemia is found when the corrected serum calcium level is > 10.5 mg/dL.1 Its symptoms are not specific and may include polyuria, dehydration, polydipsia, anorexia, nausea and/or vomiting, constipation, and other central nervous system manifestations, including confusion, delirium, cognitive impairment, muscle weakness, psychotic symptoms, and even coma.1,2

Hypercalcemia has varied etiologies; however, malignancy-induced hypercalcemia is one of the most common causes. In the US, the most common causes of malignancy-induced hypercalcemia are primary tumors of the lung or breast, multiple myeloma (MM), squamous cell carcinoma of the head or neck, renal cancer, and ovarian cancer.1

Men with prostate cancer and bone metastasis have relatively worse prognosis than do patient with no metastasis.3 In a recent meta-analysis of patients with bone-involved castration-resistant prostate cancer, the median survival was 21 months.3

Hypercalcemia is a rare manifestation of prostate cancer. In a retrospective study conducted between 2009 and 2013 using the Oncology Services Comprehensive Electronic Records (OSCER) warehouse of electronic health records (EHR), the rates of malignancy-induced hypercalcemia were the lowest among patients with prostate cancer, ranging from 1.4 to 2.1%.1

We present this case to discuss different pathophysiologic mechanisms leading to hypercalcemia in a patient with prostate cancer with bone metastasis and to study the role of humoral and growth factors in the pathogenesis of the disease.

Case Presentation

An African American man aged 69 years presented to the emergency department (ED) with generalized weakness, fatigue, and lower extremities muscle weakness. He reported a 40-lb weight loss over the past 3 months, intermittent lower back pain, and a 50 pack-year smoking history. A physical examination suggested clinical signs of dehydration.

Laboratory test results indicated hypercalcemia, macrocytic anemia, and thrombocytopenia: calcium 15.8 mg/dL, serum albumin 4.1 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase 139 μ/L, blood urea nitrogen 55 mg/dL, creatinine 3.4 mg/dL (baseline 1.4-1.5 mg/dL), hemoglobin 8 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume 99.6 fL, and platelets 100,000/μL. The patient was admitted for hypercalcemia. His intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH) was suppressed at 16 pg/mL, phosphorous was 3.8 mg/dL, parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP) was < 0.74 pmol/L, vitamin D (25 hydroxy cholecalciferol) was mildly decreased at 17.2 ng/mL, and 1,25 dihydroxy cholecalciferol (calcitriol) was < 5.0 (normal range 20-79.3 pg/mL).

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest and abdomen was taken due to the patient’s heavy smoking history, an incidentally detected right lung base nodule on chest X-ray, and hypercalcemia. The CT scan showed multiple right middle lobe lung nodules with and without calcifications and calcified right hilar lymph nodes (Figure 1).

To evaluate the pancytopenia, a bone marrow biopsy was done, which showed that 80 to 90% of the marrow space was replaced by fibrosis and metastatic malignancy. Trilinear hematopoiesis was not seen (Figure 2). The tumor cells were positive for prostate- specific membrane antigen (PSMA) and negative for cytokeratin 7 and 20 (CK7 and CK20).4 The former is a membrane protein expressed on prostate tissues, including cancer; the latter is a form of protein used to identify adenocarcinoma of unknown primary origin (CK7 usually found in primary/ metastatic lung adenocarcinoma and CK20 usually in primary and some metastatic diseases of colon adenocarcinoma).5 A prostatic specific antigen (PSA) test was markedly elevated: 335.94 ng/mL (1.46 ng/mL on a previous 2011 test).

Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the prostate was diagnosed without a prostate biopsy. To determine the extent of bone metastases, a technetium-99m-methylene diphosphonate (MDP) bone scintigraphy demonstrated a superscan with intense foci of increased radiotracer uptake involving the bilateral shoulders, sternoclavicular joints, and sternum with heterogeneous uptake involving bilateral anterior and posterior ribs; cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spines; sacrum, pelvis, and bilateral hips, including the femoral head/neck and intertrochanteric regions. Also noted were several foci of radiotracer uptake involving the mandible and bilateral skull in the region of the temporomandibular joints (Figure 3).

The patient was initially treated with IV isotonic saline, followed by calcitonin and then pamidronate after kidney function improved. His calcium level responded to the therapy, and a plan was made by medical oncology to start androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) prior to discharge.

He was initially treated with bicalutamide, while a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist (leuprolide) was added 1 week later. Bicalutamide was then discontinued and a combined androgen blockade consisting of leuprolide, ketoconazole, and hydrocortisone was started. This therapy resulted in remission, and PSA declined to 1.73 ng/ mL 3 months later. At that time the patient enrolled in a clinical trial with leuprolide and bicalutamide combined therapy. About 6 months after his diagnosis, patient’s cancer progressed and became hormone refractory disease. At that time, bicalutamide was discontinued, and his therapy was switched to combined leuprolide and enzalutamide. After 6 months of therapy with enzalutamide, the patient’s cancer progressed again. He was later treated with docetaxel chemotherapy but died 16 months after diagnosis.

showed improvement of hypercalcemia at the time of discharge, but 9 months later and toward the time of expiration, our patient developed secondary hyperparathyroidism, with calcium maintained in the normal range, while iPTH was significantly elevated, a finding likely explained by a decline in kidney function and a fall in glomerular filtration rate (Table).

Discussion

Hypercalcemia in the setting of prostate cancer is a rare complication with an uncertain pathophysiology.6 Several mechanisms have been proposed for hypercalcemia of malignancy, these comprise humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy mediated by increased PTHrP; local osteolytic hypercalcemia with secretion of other humoral factors; excess extrarenal activation of vitamin D (1,25[OH]2D); PTH secretion, ectopic or primary; and multiple concurrent etiologies.7

PTHrP is the predominant mediator for hypercalcemia of malignancy and is estimated to account for 80% of hypercalcemia in patients with cancer. This protein shares a substantial sequence homology with PTH; in fact, 8 of the first 13 amino acids at the N-terminal portion of PTH were identical.8 PTHrP has multiple isoforms (PTHrP 141, PTHrP 139, and PTHrP 173). Like PTH, it enhances renal tubular reabsorption of calcium while increasing urinary phosphorus excretion.7 The result is both hypercalcemia and hypophosphatemia. However, unlike PTH, PTHrP does not increase 1,25(OH)2D and thus does not increase intestinal absorption of calcium and phosphorus. PTHrP acts on osteoblasts, leading to enhanced synthesis of receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL).7

In one study, PTHrP was detected immunohistochemically in prostate cancer cells. Iwamura and colleagues used 33 radical prostatectomy specimens from patients with clinically localized carcinoma of the prostate.9 None of these patients demonstrated hypercalcemia prior to the surgery. Using a mouse monoclonal antibody to an amino acid fragment, all cases demonstrated some degree of immunoreactivity throughout the cytoplasm of the tumor cells, but immunostaining was absent from inflammatory and stromal cells.9Furthermore, the intensity of the staining appeared to directly correlate with increasing tumor grade.9

Another study by Iwamura and colleagues suggested that PTHrP may play a significant role in the growth of prostate cancer by acting locally in an autocrine fashion.10 In this study, all prostate cancer cell lines from different sources expressed PTHrP immunoreactivity as well as evidence of DNA synthesis, the latter being measured by thymidine incorporation assay. Moreover, when these cells were incubated with various concentrations of mouse monoclonal antibody directed to PTHrP fragment, PTHrP-induced DNA synthesis was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner and almost completely neutralized at a specific concentration. Interestingly, the study demonstrated that cancer cell line derived from bone metastatic lesions secreted significantly greater amounts of PTHrP than did the cell line derived from the metastasis in the brain or in the lymph node. These findings suggest that PTHrP production may confer some advantage on the ability of prostate cancer cells to grow in bone.10

Ando and colleagues reported that neuroendocrine dedifferentiated prostate cancer can develop as a result of long-term ADT even after several years of therapy and has the potential to worsen and develop severe hypercalcemia.8 Neuron-specific enolase was used as the specific marker for the neuroendocrine cell, which suggested that the prostate cancer cell derived from the neuroendocrine cell might synthesize PTHrP and be responsible for the observed hypercalcemia.8

Other mechanisms cited for hypercalcemia of malignancy include other humoral factors associated with increased remodeling and comprise interleukin 1, 3, 6 (IL-1, IL-3, IL-6); tumor necrosis factor α; transforming growth factor A and B observed in metastatic bone lesions in breast cancer; lymphotoxin; E series prostaglandins; and macrophage inflammatory protein 1α seen in MM.

Local osteolytic hypercalcemia accounts for about 20% of cases and is usually associated with extensive bone metastases. It is most commonly seen in MM and metastatic breast cancer and less commonly in leukemia. The proposed mechanism is thought to be because of the release of local cytokines from the tumor, resulting in excess osteoclast activation and enhanced bone resorption often through RANK/RANKL interaction.

Extrarenal production of 1,25(OH)2D by the tumor accounts for about 1% of cases of hypercalcemia in malignancy. 1,25(OH)2D causes increased intestinal absorption of calcium and enhances osteolytic bone resorption, resulting in increased serum calcium. This mechanism is most commonly seen with Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma and had been reported in ovarian dysgerminoma.7

In our patient, bone imaging showed osteoblastic lesions, a finding that likely contrasts the local osteolytic bone destruction theory. PTHrP was not significantly elevated in the serum, and PTH levels ruled out any form of primary hyperparathyroidism. In addition, histopathology showed no evidence of mosaicism or neuroendocrine dedifferentiation.

Findings in aggregate tell us that an exact pathophysiologic mechanism leading to hypercalcemia in prostate cancer is still unclear and may involve an interplay between growth factors and possible osteolytic materials, yet it must be studied thoroughly.

Conclusions

Hypercalcemia in pure metastatic adenocarcinoma of prostate is a rare finding and is of uncertain significance. Some studies suggested a search for unusual histopathologies, including neuroendocrine cancer and neuroendocrine dedifferentiation.8,11 However, in adenocarcinoma alone, it has an uncertain pathophysiology that needs to be further studied. Studies needed to investigate the role of PTHrP as a growth factor for both prostate cancer cells and development of hypercalcemia and possibly target-directed monoclonal antibody therapies may need to be extensively researched.

Hypercalcemia is found when the corrected serum calcium level is > 10.5 mg/dL.1 Its symptoms are not specific and may include polyuria, dehydration, polydipsia, anorexia, nausea and/or vomiting, constipation, and other central nervous system manifestations, including confusion, delirium, cognitive impairment, muscle weakness, psychotic symptoms, and even coma.1,2

Hypercalcemia has varied etiologies; however, malignancy-induced hypercalcemia is one of the most common causes. In the US, the most common causes of malignancy-induced hypercalcemia are primary tumors of the lung or breast, multiple myeloma (MM), squamous cell carcinoma of the head or neck, renal cancer, and ovarian cancer.1

Men with prostate cancer and bone metastasis have relatively worse prognosis than do patient with no metastasis.3 In a recent meta-analysis of patients with bone-involved castration-resistant prostate cancer, the median survival was 21 months.3

Hypercalcemia is a rare manifestation of prostate cancer. In a retrospective study conducted between 2009 and 2013 using the Oncology Services Comprehensive Electronic Records (OSCER) warehouse of electronic health records (EHR), the rates of malignancy-induced hypercalcemia were the lowest among patients with prostate cancer, ranging from 1.4 to 2.1%.1

We present this case to discuss different pathophysiologic mechanisms leading to hypercalcemia in a patient with prostate cancer with bone metastasis and to study the role of humoral and growth factors in the pathogenesis of the disease.

Case Presentation

An African American man aged 69 years presented to the emergency department (ED) with generalized weakness, fatigue, and lower extremities muscle weakness. He reported a 40-lb weight loss over the past 3 months, intermittent lower back pain, and a 50 pack-year smoking history. A physical examination suggested clinical signs of dehydration.

Laboratory test results indicated hypercalcemia, macrocytic anemia, and thrombocytopenia: calcium 15.8 mg/dL, serum albumin 4.1 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase 139 μ/L, blood urea nitrogen 55 mg/dL, creatinine 3.4 mg/dL (baseline 1.4-1.5 mg/dL), hemoglobin 8 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume 99.6 fL, and platelets 100,000/μL. The patient was admitted for hypercalcemia. His intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH) was suppressed at 16 pg/mL, phosphorous was 3.8 mg/dL, parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP) was < 0.74 pmol/L, vitamin D (25 hydroxy cholecalciferol) was mildly decreased at 17.2 ng/mL, and 1,25 dihydroxy cholecalciferol (calcitriol) was < 5.0 (normal range 20-79.3 pg/mL).

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest and abdomen was taken due to the patient’s heavy smoking history, an incidentally detected right lung base nodule on chest X-ray, and hypercalcemia. The CT scan showed multiple right middle lobe lung nodules with and without calcifications and calcified right hilar lymph nodes (Figure 1).

To evaluate the pancytopenia, a bone marrow biopsy was done, which showed that 80 to 90% of the marrow space was replaced by fibrosis and metastatic malignancy. Trilinear hematopoiesis was not seen (Figure 2). The tumor cells were positive for prostate- specific membrane antigen (PSMA) and negative for cytokeratin 7 and 20 (CK7 and CK20).4 The former is a membrane protein expressed on prostate tissues, including cancer; the latter is a form of protein used to identify adenocarcinoma of unknown primary origin (CK7 usually found in primary/ metastatic lung adenocarcinoma and CK20 usually in primary and some metastatic diseases of colon adenocarcinoma).5 A prostatic specific antigen (PSA) test was markedly elevated: 335.94 ng/mL (1.46 ng/mL on a previous 2011 test).

Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the prostate was diagnosed without a prostate biopsy. To determine the extent of bone metastases, a technetium-99m-methylene diphosphonate (MDP) bone scintigraphy demonstrated a superscan with intense foci of increased radiotracer uptake involving the bilateral shoulders, sternoclavicular joints, and sternum with heterogeneous uptake involving bilateral anterior and posterior ribs; cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spines; sacrum, pelvis, and bilateral hips, including the femoral head/neck and intertrochanteric regions. Also noted were several foci of radiotracer uptake involving the mandible and bilateral skull in the region of the temporomandibular joints (Figure 3).

The patient was initially treated with IV isotonic saline, followed by calcitonin and then pamidronate after kidney function improved. His calcium level responded to the therapy, and a plan was made by medical oncology to start androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) prior to discharge.

He was initially treated with bicalutamide, while a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist (leuprolide) was added 1 week later. Bicalutamide was then discontinued and a combined androgen blockade consisting of leuprolide, ketoconazole, and hydrocortisone was started. This therapy resulted in remission, and PSA declined to 1.73 ng/ mL 3 months later. At that time the patient enrolled in a clinical trial with leuprolide and bicalutamide combined therapy. About 6 months after his diagnosis, patient’s cancer progressed and became hormone refractory disease. At that time, bicalutamide was discontinued, and his therapy was switched to combined leuprolide and enzalutamide. After 6 months of therapy with enzalutamide, the patient’s cancer progressed again. He was later treated with docetaxel chemotherapy but died 16 months after diagnosis.

showed improvement of hypercalcemia at the time of discharge, but 9 months later and toward the time of expiration, our patient developed secondary hyperparathyroidism, with calcium maintained in the normal range, while iPTH was significantly elevated, a finding likely explained by a decline in kidney function and a fall in glomerular filtration rate (Table).

Discussion

Hypercalcemia in the setting of prostate cancer is a rare complication with an uncertain pathophysiology.6 Several mechanisms have been proposed for hypercalcemia of malignancy, these comprise humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy mediated by increased PTHrP; local osteolytic hypercalcemia with secretion of other humoral factors; excess extrarenal activation of vitamin D (1,25[OH]2D); PTH secretion, ectopic or primary; and multiple concurrent etiologies.7

PTHrP is the predominant mediator for hypercalcemia of malignancy and is estimated to account for 80% of hypercalcemia in patients with cancer. This protein shares a substantial sequence homology with PTH; in fact, 8 of the first 13 amino acids at the N-terminal portion of PTH were identical.8 PTHrP has multiple isoforms (PTHrP 141, PTHrP 139, and PTHrP 173). Like PTH, it enhances renal tubular reabsorption of calcium while increasing urinary phosphorus excretion.7 The result is both hypercalcemia and hypophosphatemia. However, unlike PTH, PTHrP does not increase 1,25(OH)2D and thus does not increase intestinal absorption of calcium and phosphorus. PTHrP acts on osteoblasts, leading to enhanced synthesis of receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL).7

In one study, PTHrP was detected immunohistochemically in prostate cancer cells. Iwamura and colleagues used 33 radical prostatectomy specimens from patients with clinically localized carcinoma of the prostate.9 None of these patients demonstrated hypercalcemia prior to the surgery. Using a mouse monoclonal antibody to an amino acid fragment, all cases demonstrated some degree of immunoreactivity throughout the cytoplasm of the tumor cells, but immunostaining was absent from inflammatory and stromal cells.9Furthermore, the intensity of the staining appeared to directly correlate with increasing tumor grade.9

Another study by Iwamura and colleagues suggested that PTHrP may play a significant role in the growth of prostate cancer by acting locally in an autocrine fashion.10 In this study, all prostate cancer cell lines from different sources expressed PTHrP immunoreactivity as well as evidence of DNA synthesis, the latter being measured by thymidine incorporation assay. Moreover, when these cells were incubated with various concentrations of mouse monoclonal antibody directed to PTHrP fragment, PTHrP-induced DNA synthesis was inhibited in a dose-dependent manner and almost completely neutralized at a specific concentration. Interestingly, the study demonstrated that cancer cell line derived from bone metastatic lesions secreted significantly greater amounts of PTHrP than did the cell line derived from the metastasis in the brain or in the lymph node. These findings suggest that PTHrP production may confer some advantage on the ability of prostate cancer cells to grow in bone.10

Ando and colleagues reported that neuroendocrine dedifferentiated prostate cancer can develop as a result of long-term ADT even after several years of therapy and has the potential to worsen and develop severe hypercalcemia.8 Neuron-specific enolase was used as the specific marker for the neuroendocrine cell, which suggested that the prostate cancer cell derived from the neuroendocrine cell might synthesize PTHrP and be responsible for the observed hypercalcemia.8

Other mechanisms cited for hypercalcemia of malignancy include other humoral factors associated with increased remodeling and comprise interleukin 1, 3, 6 (IL-1, IL-3, IL-6); tumor necrosis factor α; transforming growth factor A and B observed in metastatic bone lesions in breast cancer; lymphotoxin; E series prostaglandins; and macrophage inflammatory protein 1α seen in MM.

Local osteolytic hypercalcemia accounts for about 20% of cases and is usually associated with extensive bone metastases. It is most commonly seen in MM and metastatic breast cancer and less commonly in leukemia. The proposed mechanism is thought to be because of the release of local cytokines from the tumor, resulting in excess osteoclast activation and enhanced bone resorption often through RANK/RANKL interaction.

Extrarenal production of 1,25(OH)2D by the tumor accounts for about 1% of cases of hypercalcemia in malignancy. 1,25(OH)2D causes increased intestinal absorption of calcium and enhances osteolytic bone resorption, resulting in increased serum calcium. This mechanism is most commonly seen with Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma and had been reported in ovarian dysgerminoma.7

In our patient, bone imaging showed osteoblastic lesions, a finding that likely contrasts the local osteolytic bone destruction theory. PTHrP was not significantly elevated in the serum, and PTH levels ruled out any form of primary hyperparathyroidism. In addition, histopathology showed no evidence of mosaicism or neuroendocrine dedifferentiation.

Findings in aggregate tell us that an exact pathophysiologic mechanism leading to hypercalcemia in prostate cancer is still unclear and may involve an interplay between growth factors and possible osteolytic materials, yet it must be studied thoroughly.

Conclusions

Hypercalcemia in pure metastatic adenocarcinoma of prostate is a rare finding and is of uncertain significance. Some studies suggested a search for unusual histopathologies, including neuroendocrine cancer and neuroendocrine dedifferentiation.8,11 However, in adenocarcinoma alone, it has an uncertain pathophysiology that needs to be further studied. Studies needed to investigate the role of PTHrP as a growth factor for both prostate cancer cells and development of hypercalcemia and possibly target-directed monoclonal antibody therapies may need to be extensively researched.

1. Gastanaga VM, Schwartzberg LS, Jain RK, et al. Prevalence of hypercalcemia among cancer patients in the United States. Cancer Med. 2016;5(8):2091‐2100. doi:10.1002/cam4.749

2. Grill V, Martin TJ. Hypercalcemia of malignancy. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2000;1(4):253‐263. doi:10.1023/a:1026597816193

3. Halabi S, Kelly WK, Ma H, et al. Meta-analysis evaluating the impact of site of metastasis on overall survival in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(14):1652‐1659. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.65.7270

4. Chang SS. Overview of prostate-specific membrane antigen. Rev Urol. 2004;6(suppl 10):S13‐S18.

5. Kummar S, Fogarasi M, Canova A, Mota A, Ciesielski T. Cytokeratin 7 and 20 staining for the diagnosis of lung and colorectal adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2002;86(12):1884‐1887. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6600326

6. Avashia JH, Walsh TD, Thomas AJ Jr, Kaye M, Licata A. Metastatic carcinoma of the prostate with hypercalcemia [published correction appears in Cleve Clin J Med. 1991;58(3):284]. Cleve Clin J Med. 1990;57(7):636‐638. doi:10.3949/ccjm.57.7.636.

7. Goldner W. Cancer-related hypercalcemia. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(5):426‐432. doi:10.1200/JOP.2016.011155.

8. Ando T, Watanabe K, Mizusawa T, Katagiri A. Hypercalcemia due to parathyroid hormone-related peptide secreted by neuroendocrine dedifferentiated prostate cancer. Urol Case Rep. 2018;22:67‐69. doi:10.1016/j.eucr.2018.11.001

9. Iwamura M, di Sant’Agnese PA, Wu G, et al. Immunohistochemical localization of parathyroid hormonerelated protein in human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1993;53(8):1724‐1726.

10. Iwamura M, Abrahamsson PA, Foss KA, Wu G, Cockett AT, Deftos LJ. Parathyroid hormone-related protein: a potential autocrine growth regulator in human prostate cancer cell lines. Urology. 1994;43(5):675‐679. doi:10.1016/0090-4295(94)90183-x

11. Smith DC, Tucker JA, Trump DL. Hypercalcemia and neuroendocrine carcinoma of the prostate: a report of three cases and a review of the literature. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10(3):499‐505. doi:10.1200/JCO.1992.10.3.499.

1. Gastanaga VM, Schwartzberg LS, Jain RK, et al. Prevalence of hypercalcemia among cancer patients in the United States. Cancer Med. 2016;5(8):2091‐2100. doi:10.1002/cam4.749

2. Grill V, Martin TJ. Hypercalcemia of malignancy. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2000;1(4):253‐263. doi:10.1023/a:1026597816193

3. Halabi S, Kelly WK, Ma H, et al. Meta-analysis evaluating the impact of site of metastasis on overall survival in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(14):1652‐1659. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.65.7270

4. Chang SS. Overview of prostate-specific membrane antigen. Rev Urol. 2004;6(suppl 10):S13‐S18.

5. Kummar S, Fogarasi M, Canova A, Mota A, Ciesielski T. Cytokeratin 7 and 20 staining for the diagnosis of lung and colorectal adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2002;86(12):1884‐1887. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6600326

6. Avashia JH, Walsh TD, Thomas AJ Jr, Kaye M, Licata A. Metastatic carcinoma of the prostate with hypercalcemia [published correction appears in Cleve Clin J Med. 1991;58(3):284]. Cleve Clin J Med. 1990;57(7):636‐638. doi:10.3949/ccjm.57.7.636.

7. Goldner W. Cancer-related hypercalcemia. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12(5):426‐432. doi:10.1200/JOP.2016.011155.

8. Ando T, Watanabe K, Mizusawa T, Katagiri A. Hypercalcemia due to parathyroid hormone-related peptide secreted by neuroendocrine dedifferentiated prostate cancer. Urol Case Rep. 2018;22:67‐69. doi:10.1016/j.eucr.2018.11.001

9. Iwamura M, di Sant’Agnese PA, Wu G, et al. Immunohistochemical localization of parathyroid hormonerelated protein in human prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 1993;53(8):1724‐1726.

10. Iwamura M, Abrahamsson PA, Foss KA, Wu G, Cockett AT, Deftos LJ. Parathyroid hormone-related protein: a potential autocrine growth regulator in human prostate cancer cell lines. Urology. 1994;43(5):675‐679. doi:10.1016/0090-4295(94)90183-x

11. Smith DC, Tucker JA, Trump DL. Hypercalcemia and neuroendocrine carcinoma of the prostate: a report of three cases and a review of the literature. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10(3):499‐505. doi:10.1200/JCO.1992.10.3.499.

FDA approves olaparib for certain metastatic prostate cancers

The Food and Drug Administration approved olaparib (Lynparza, AstraZeneca) for deleterious or suspected deleterious germline or somatic homologous recombination repair (HRR) gene-mutated metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC).

The drug is limited to use in men who have progressed following prior treatment with enzalutamide or abiraterone.

Olaparib becomes the second PARP inhibitor approved by the FDA for use in prostate cancer this week. Earlier, rucaparib (Rubraca, Clovis Oncology) was approved for use in patients with mCRPC that harbor deleterious BRCA mutations (germline and/or somatic).

Olaparib is also indicated for use in ovarian, breast, and pancreatic cancers.

The FDA also approved two companion diagnostic devices for treatment with olaparib: the FoundationOne CDx test (Foundation Medicine) for the selection of patients carrying HRR gene alterations and the BRACAnalysis CDx test (Myriad Genetic Laboratories) for the selection of patients carrying germline BRCA1/2 alterations.

The approval was based on results from the open-label, multicenter PROfound trial, which randomly assigned 387 patients to olaparib 300 mg twice daily and to investigator’s choice of enzalutamide or abiraterone acetate. All patients received a GnRH analogue or had prior bilateral orchiectomy.

The study involved two cohorts. Patients with mutations in either BRCA1, BRCA2, or ATM were randomly assigned in cohort A (n = 245); patients with mutations among 12 other genes involved in the HRR pathway were randomly assigned in cohort B (n = 142); those with co-mutations were assigned to cohort A.

The major efficacy outcome of the trial was radiological progression-free survival (rPFS) (cohort A).

In cohort A, patients receiving olaparib had a median rPFS of 7.4 months vs 3.6 months among patients receiving investigator’s choice (hazard ratio [HR], 0.34; P < .0001). Median overall survival was 19.1 months vs 14.7 months (HR, 0.69; P = .0175) and the overall response rate was 33% vs 2% (P < .0001).

In cohort A+B, patients receiving olaparib had a median rPFS of 5.8 months vs 3.5 months among patients receiving investigator’s choice (HR, 0.49; P < .0001).

The study results were first presented at the 2019 annual meeting of the European Society for Medical Oncology. At that time, study investigator Maha Hussain, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, said the rPFS result and other outcomes were a “remarkable achievement” in such heavily pretreated patients with prostate cancer.

Patients with prostate cancer should now undergo genetic testing of tumor tissue to identify the roughly 30% of patients who can benefit – as is already routinely being done for breast, ovarian, and lung cancer, said experts at ESMO.

The most common adverse reactions with olaparib (≥10% of patients) were anemia, nausea, fatigue (including asthenia), decreased appetite, diarrhea, vomiting, thrombocytopenia, cough, and dyspnea. Venous thromboembolic events, including pulmonary embolism, occurred in 7% of patients randomly assigned to olaparib, compared with 3.1% of those receiving investigator’s choice of enzalutamide or abiraterone.

Olaparib carries the warning that myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia (MDS/AML) occurred in <1.5% of patients exposed to it as a monotherapy, and that the majority of events had a fatal outcome.

The recommended olaparib dose is 300 mg taken orally twice daily, with or without food.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration approved olaparib (Lynparza, AstraZeneca) for deleterious or suspected deleterious germline or somatic homologous recombination repair (HRR) gene-mutated metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC).

The drug is limited to use in men who have progressed following prior treatment with enzalutamide or abiraterone.

Olaparib becomes the second PARP inhibitor approved by the FDA for use in prostate cancer this week. Earlier, rucaparib (Rubraca, Clovis Oncology) was approved for use in patients with mCRPC that harbor deleterious BRCA mutations (germline and/or somatic).

Olaparib is also indicated for use in ovarian, breast, and pancreatic cancers.

The FDA also approved two companion diagnostic devices for treatment with olaparib: the FoundationOne CDx test (Foundation Medicine) for the selection of patients carrying HRR gene alterations and the BRACAnalysis CDx test (Myriad Genetic Laboratories) for the selection of patients carrying germline BRCA1/2 alterations.

The approval was based on results from the open-label, multicenter PROfound trial, which randomly assigned 387 patients to olaparib 300 mg twice daily and to investigator’s choice of enzalutamide or abiraterone acetate. All patients received a GnRH analogue or had prior bilateral orchiectomy.

The study involved two cohorts. Patients with mutations in either BRCA1, BRCA2, or ATM were randomly assigned in cohort A (n = 245); patients with mutations among 12 other genes involved in the HRR pathway were randomly assigned in cohort B (n = 142); those with co-mutations were assigned to cohort A.

The major efficacy outcome of the trial was radiological progression-free survival (rPFS) (cohort A).

In cohort A, patients receiving olaparib had a median rPFS of 7.4 months vs 3.6 months among patients receiving investigator’s choice (hazard ratio [HR], 0.34; P < .0001). Median overall survival was 19.1 months vs 14.7 months (HR, 0.69; P = .0175) and the overall response rate was 33% vs 2% (P < .0001).

In cohort A+B, patients receiving olaparib had a median rPFS of 5.8 months vs 3.5 months among patients receiving investigator’s choice (HR, 0.49; P < .0001).

The study results were first presented at the 2019 annual meeting of the European Society for Medical Oncology. At that time, study investigator Maha Hussain, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, said the rPFS result and other outcomes were a “remarkable achievement” in such heavily pretreated patients with prostate cancer.

Patients with prostate cancer should now undergo genetic testing of tumor tissue to identify the roughly 30% of patients who can benefit – as is already routinely being done for breast, ovarian, and lung cancer, said experts at ESMO.

The most common adverse reactions with olaparib (≥10% of patients) were anemia, nausea, fatigue (including asthenia), decreased appetite, diarrhea, vomiting, thrombocytopenia, cough, and dyspnea. Venous thromboembolic events, including pulmonary embolism, occurred in 7% of patients randomly assigned to olaparib, compared with 3.1% of those receiving investigator’s choice of enzalutamide or abiraterone.

Olaparib carries the warning that myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia (MDS/AML) occurred in <1.5% of patients exposed to it as a monotherapy, and that the majority of events had a fatal outcome.

The recommended olaparib dose is 300 mg taken orally twice daily, with or without food.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration approved olaparib (Lynparza, AstraZeneca) for deleterious or suspected deleterious germline or somatic homologous recombination repair (HRR) gene-mutated metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC).

The drug is limited to use in men who have progressed following prior treatment with enzalutamide or abiraterone.

Olaparib becomes the second PARP inhibitor approved by the FDA for use in prostate cancer this week. Earlier, rucaparib (Rubraca, Clovis Oncology) was approved for use in patients with mCRPC that harbor deleterious BRCA mutations (germline and/or somatic).

Olaparib is also indicated for use in ovarian, breast, and pancreatic cancers.

The FDA also approved two companion diagnostic devices for treatment with olaparib: the FoundationOne CDx test (Foundation Medicine) for the selection of patients carrying HRR gene alterations and the BRACAnalysis CDx test (Myriad Genetic Laboratories) for the selection of patients carrying germline BRCA1/2 alterations.

The approval was based on results from the open-label, multicenter PROfound trial, which randomly assigned 387 patients to olaparib 300 mg twice daily and to investigator’s choice of enzalutamide or abiraterone acetate. All patients received a GnRH analogue or had prior bilateral orchiectomy.

The study involved two cohorts. Patients with mutations in either BRCA1, BRCA2, or ATM were randomly assigned in cohort A (n = 245); patients with mutations among 12 other genes involved in the HRR pathway were randomly assigned in cohort B (n = 142); those with co-mutations were assigned to cohort A.

The major efficacy outcome of the trial was radiological progression-free survival (rPFS) (cohort A).

In cohort A, patients receiving olaparib had a median rPFS of 7.4 months vs 3.6 months among patients receiving investigator’s choice (hazard ratio [HR], 0.34; P < .0001). Median overall survival was 19.1 months vs 14.7 months (HR, 0.69; P = .0175) and the overall response rate was 33% vs 2% (P < .0001).

In cohort A+B, patients receiving olaparib had a median rPFS of 5.8 months vs 3.5 months among patients receiving investigator’s choice (HR, 0.49; P < .0001).

The study results were first presented at the 2019 annual meeting of the European Society for Medical Oncology. At that time, study investigator Maha Hussain, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, said the rPFS result and other outcomes were a “remarkable achievement” in such heavily pretreated patients with prostate cancer.

Patients with prostate cancer should now undergo genetic testing of tumor tissue to identify the roughly 30% of patients who can benefit – as is already routinely being done for breast, ovarian, and lung cancer, said experts at ESMO.

The most common adverse reactions with olaparib (≥10% of patients) were anemia, nausea, fatigue (including asthenia), decreased appetite, diarrhea, vomiting, thrombocytopenia, cough, and dyspnea. Venous thromboembolic events, including pulmonary embolism, occurred in 7% of patients randomly assigned to olaparib, compared with 3.1% of those receiving investigator’s choice of enzalutamide or abiraterone.

Olaparib carries the warning that myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia (MDS/AML) occurred in <1.5% of patients exposed to it as a monotherapy, and that the majority of events had a fatal outcome.

The recommended olaparib dose is 300 mg taken orally twice daily, with or without food.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

First PARP inhibitor approved for metastatic prostate cancer

A completely new approach to the treatment of prostate cancer is now available to clinicians through the approval of the first PARP inhibitor for use in certain patients with this disease.

Rucaparib (Rubraca, Clovis Oncology) is the first PARP inhibitor approved for use in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) that harbors deleterious BRCA mutations (germline and/or somatic). The drug is indicated for use in patients who have already been treated with androgen receptor–directed therapy and a taxane-based chemotherapy.

The drug is already marketed for use in ovarian cancer.

The new prostate cancer indication was granted an accelerated approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on the basis of response rates and effect on levels of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) from the TRITON2 clinical trial. A confirmatory phase 3 trial, TRITON3, is currently underway.

“Standard treatment options for men with mCRPC have been limited to androgen receptor–targeting therapies, taxane chemotherapy, radium-223, and sipuleucel-T,” said Wassim Abida, MD, a medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, in a statement.

“Rucaparib is the first in a class of drugs to become newly available to patients with mCRPC who harbor a deleterious BRCA mutation,” said Abida, who is also the principal investigator of the TRITON2 study. “Given the level and duration of responses observed with rucaparib in men with mCRPC and these mutations, it represents an important and timely new treatment option for this patient population.”

Other indications, another PARP inhibitor

Rucaparib is already approved for the treatment of women with advanced BRCA mutation–positive ovarian cancer who have received two or more prior chemotherapies. It is also approved as maintenance treatment for patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer who demonstrate a complete or partial response to platinum-based chemotherapy, regardless of BRCA status.

Another PARP inhibitor, olaparib (Lynparza, AstraZeneca), is awaiting approval for use in prostate cancer in men with BRCA mutations. That pending approval is based on results from the phase 3 PROfound trial, which was hailed as a “landmark trial” when it was presented last year. The results showed a significant improved in disease-free progression. The company recently announced that there was also a significant improvement in overall survival.

Olaparib is already approved for the maintenance treatment of platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer regardless of BRCA status and as first-line maintenance treatment in BRCA-mutated advanced ovarian cancer following response to platinum-based chemotherapy. It is also approved for germline BRCA-mutated HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer previously treated with chemotherapy and for the maintenance treatment of germline BRCA-mutated advanced pancreatic cancer following first-line platinum-based chemotherapy.

Details of the TRITON2 study

The accelerated approval for use of rucaparib in BRCA prostate cancer was based on efficacy data from the multicenter, single-arm TRITON2 clinical trial. The cohort included 62 patients with a BRCA (germline and/or somatic) mutation and measurable disease; 115 patients with a BRCA (germline and/or somatic) mutation and measurable or nonmeasurable disease; and 209 patients with homologous recombination deficiency (HRD)–positive mCRPC.

The major efficacy outcomes were objective response rate (ORR) and duration of response. Confirmed PSA response rate was also a prespecified endpoint. Data were assessed by independent radiologic review.

For the patients with measurable disease and a BRCA mutation, the ORR was 44%. The ORR was similar for patients with a germline BRCA mutation.

Median duration of response was not evaluable at data cutoff but ranged from 1.7 to 24+ months. Of the 27 patients with a confirmed objective response, 15 (56%) patients showed a response that lasted 6 months or longer.

In an analysis of 115 patients with a deleterious BRCA mutation (germline and/or somatic) and measurable or nonmeasurable disease, the confirmed PSA response rate was 55%.

The safety evaluation was based on an analysis of the 209 patients with HRD-positive mCRPC and included 115 with deleterious BRCA mutations. The most common adverse events (≥20%; grade 1-4) in the patients with BRCA mutations were fatigue/asthenia (62%), nausea (52%), anemia (43%), AST/ALT elevation (33%), decreased appetite (28%), rash (27%), constipation (27%), thrombocytopenia (25%), vomiting (22%), and diarrhea (20%).

Rucaparib has been associated with hematologic toxicity, including myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML). However, MDS/AML was not observed in the TRITON2 study, regardless of HRD mutation.

Confirmation with TRITON3

A phase 3, randomized, open-label study, TRITON3, is currently underway and is expected to serve as the confirmatory study for the accelerated approval in mCRPC. TRITON3 is comparing rucaparib with physician’s choice of therapy in patients with mCRPC who have specific gene alterations, including BRCA and ATM alterations, and who have experienced disease progression after androgen receptor–directed therapy but have not yet received chemotherapy. The primary endpoint for TRITON3 is radiographic progression-free survival.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A completely new approach to the treatment of prostate cancer is now available to clinicians through the approval of the first PARP inhibitor for use in certain patients with this disease.

Rucaparib (Rubraca, Clovis Oncology) is the first PARP inhibitor approved for use in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) that harbors deleterious BRCA mutations (germline and/or somatic). The drug is indicated for use in patients who have already been treated with androgen receptor–directed therapy and a taxane-based chemotherapy.

The drug is already marketed for use in ovarian cancer.

The new prostate cancer indication was granted an accelerated approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on the basis of response rates and effect on levels of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) from the TRITON2 clinical trial. A confirmatory phase 3 trial, TRITON3, is currently underway.

“Standard treatment options for men with mCRPC have been limited to androgen receptor–targeting therapies, taxane chemotherapy, radium-223, and sipuleucel-T,” said Wassim Abida, MD, a medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, in a statement.

“Rucaparib is the first in a class of drugs to become newly available to patients with mCRPC who harbor a deleterious BRCA mutation,” said Abida, who is also the principal investigator of the TRITON2 study. “Given the level and duration of responses observed with rucaparib in men with mCRPC and these mutations, it represents an important and timely new treatment option for this patient population.”

Other indications, another PARP inhibitor

Rucaparib is already approved for the treatment of women with advanced BRCA mutation–positive ovarian cancer who have received two or more prior chemotherapies. It is also approved as maintenance treatment for patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer who demonstrate a complete or partial response to platinum-based chemotherapy, regardless of BRCA status.

Another PARP inhibitor, olaparib (Lynparza, AstraZeneca), is awaiting approval for use in prostate cancer in men with BRCA mutations. That pending approval is based on results from the phase 3 PROfound trial, which was hailed as a “landmark trial” when it was presented last year. The results showed a significant improved in disease-free progression. The company recently announced that there was also a significant improvement in overall survival.

Olaparib is already approved for the maintenance treatment of platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer regardless of BRCA status and as first-line maintenance treatment in BRCA-mutated advanced ovarian cancer following response to platinum-based chemotherapy. It is also approved for germline BRCA-mutated HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer previously treated with chemotherapy and for the maintenance treatment of germline BRCA-mutated advanced pancreatic cancer following first-line platinum-based chemotherapy.

Details of the TRITON2 study

The accelerated approval for use of rucaparib in BRCA prostate cancer was based on efficacy data from the multicenter, single-arm TRITON2 clinical trial. The cohort included 62 patients with a BRCA (germline and/or somatic) mutation and measurable disease; 115 patients with a BRCA (germline and/or somatic) mutation and measurable or nonmeasurable disease; and 209 patients with homologous recombination deficiency (HRD)–positive mCRPC.

The major efficacy outcomes were objective response rate (ORR) and duration of response. Confirmed PSA response rate was also a prespecified endpoint. Data were assessed by independent radiologic review.

For the patients with measurable disease and a BRCA mutation, the ORR was 44%. The ORR was similar for patients with a germline BRCA mutation.

Median duration of response was not evaluable at data cutoff but ranged from 1.7 to 24+ months. Of the 27 patients with a confirmed objective response, 15 (56%) patients showed a response that lasted 6 months or longer.

In an analysis of 115 patients with a deleterious BRCA mutation (germline and/or somatic) and measurable or nonmeasurable disease, the confirmed PSA response rate was 55%.

The safety evaluation was based on an analysis of the 209 patients with HRD-positive mCRPC and included 115 with deleterious BRCA mutations. The most common adverse events (≥20%; grade 1-4) in the patients with BRCA mutations were fatigue/asthenia (62%), nausea (52%), anemia (43%), AST/ALT elevation (33%), decreased appetite (28%), rash (27%), constipation (27%), thrombocytopenia (25%), vomiting (22%), and diarrhea (20%).

Rucaparib has been associated with hematologic toxicity, including myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML). However, MDS/AML was not observed in the TRITON2 study, regardless of HRD mutation.

Confirmation with TRITON3

A phase 3, randomized, open-label study, TRITON3, is currently underway and is expected to serve as the confirmatory study for the accelerated approval in mCRPC. TRITON3 is comparing rucaparib with physician’s choice of therapy in patients with mCRPC who have specific gene alterations, including BRCA and ATM alterations, and who have experienced disease progression after androgen receptor–directed therapy but have not yet received chemotherapy. The primary endpoint for TRITON3 is radiographic progression-free survival.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A completely new approach to the treatment of prostate cancer is now available to clinicians through the approval of the first PARP inhibitor for use in certain patients with this disease.

Rucaparib (Rubraca, Clovis Oncology) is the first PARP inhibitor approved for use in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) that harbors deleterious BRCA mutations (germline and/or somatic). The drug is indicated for use in patients who have already been treated with androgen receptor–directed therapy and a taxane-based chemotherapy.

The drug is already marketed for use in ovarian cancer.

The new prostate cancer indication was granted an accelerated approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on the basis of response rates and effect on levels of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) from the TRITON2 clinical trial. A confirmatory phase 3 trial, TRITON3, is currently underway.

“Standard treatment options for men with mCRPC have been limited to androgen receptor–targeting therapies, taxane chemotherapy, radium-223, and sipuleucel-T,” said Wassim Abida, MD, a medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, in a statement.

“Rucaparib is the first in a class of drugs to become newly available to patients with mCRPC who harbor a deleterious BRCA mutation,” said Abida, who is also the principal investigator of the TRITON2 study. “Given the level and duration of responses observed with rucaparib in men with mCRPC and these mutations, it represents an important and timely new treatment option for this patient population.”

Other indications, another PARP inhibitor

Rucaparib is already approved for the treatment of women with advanced BRCA mutation–positive ovarian cancer who have received two or more prior chemotherapies. It is also approved as maintenance treatment for patients with recurrent epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer who demonstrate a complete or partial response to platinum-based chemotherapy, regardless of BRCA status.

Another PARP inhibitor, olaparib (Lynparza, AstraZeneca), is awaiting approval for use in prostate cancer in men with BRCA mutations. That pending approval is based on results from the phase 3 PROfound trial, which was hailed as a “landmark trial” when it was presented last year. The results showed a significant improved in disease-free progression. The company recently announced that there was also a significant improvement in overall survival.