User login

Countries with high malaria burden don’t receive research funding

A new study has revealed inequalities in malaria research funding in sub-Saharan Africa.

The study showed that some countries with a high malaria burden—such as Sierra Leone, Congo, Central African Republic, and Guinea—received little to no funding for malaria research in recent years.

However, other countries—such as Tanzania, Uganda, and Kenya—received close to $100 million in funding for malaria research.

Michael Head, PhD, of the University of Southampton in the UK, and his colleagues reported these findings in The Lancet Global Health.

“We have been able to provide a comprehensive overview of the landscape of funding for malaria in sub-Saharan Africa, a massive area where around 90% of worldwide malaria cases occur,” Dr Head said.

“We’ve shown that there are countries that are being neglected, and the global health community should reconsider strategies around resource allocation to reduce inequities and improve equality.”

For this study, Dr Head and his colleagues analyzed funding data spanning the period from 1997 to 2013. The data were sourced from 13 major public and philanthropic global health funders, as well as from funding databases.

The researchers ranked 45 countries according to the level of malaria research funding they received.

All of the countries studied received funding for malaria control, which includes investment for bed nets, public health schemes, and antimalarial drugs.

However, 8 of the 45 countries did not receive any funding related to malaria research. This included Central African Republic, Sierra Leone, and Congo—countries with a “reasonably high” malaria burden/mortality rate, according to Dr Head and his colleagues.

In all, there were 333 research awards, totaling $814.4 million. The countries that received the most research funding were Tanzania ($107.8 million), Uganda ($97.9 million), and Kenya ($92.9 million).

The 8 countries that received no research funding were Cape Verde, Botswana, Djibouti, Central African Republic, Mauritania, Congo, Chad, and Sierra Leone.

Dr Head and his colleagues suggested that the reason for the disparity in funding allocation could be, in part, due to the presence of established high-quality research infrastructure in countries such as Tanzania and Kenya, and political instability and poor healthcare infrastructures in lower-ranked nations such as Central African Republic or Sierra Leone.

“[N]ew investment in malaria research and development in these areas can encourage the development of improved health systems,” Dr Head said. “Many countries in sub-Saharan Africa simply do not have an established research infrastructure, and it is difficult for research funders to make investments in these settings.”

“Ultimately, however, there are neglected populations in these countries who suffer greatly from malaria and other diseases. Investments in health improve the wealth of a nation, and we need to be smarter with allocating limited resources to best help to reduce clear health inequalities.” ![]()

A new study has revealed inequalities in malaria research funding in sub-Saharan Africa.

The study showed that some countries with a high malaria burden—such as Sierra Leone, Congo, Central African Republic, and Guinea—received little to no funding for malaria research in recent years.

However, other countries—such as Tanzania, Uganda, and Kenya—received close to $100 million in funding for malaria research.

Michael Head, PhD, of the University of Southampton in the UK, and his colleagues reported these findings in The Lancet Global Health.

“We have been able to provide a comprehensive overview of the landscape of funding for malaria in sub-Saharan Africa, a massive area where around 90% of worldwide malaria cases occur,” Dr Head said.

“We’ve shown that there are countries that are being neglected, and the global health community should reconsider strategies around resource allocation to reduce inequities and improve equality.”

For this study, Dr Head and his colleagues analyzed funding data spanning the period from 1997 to 2013. The data were sourced from 13 major public and philanthropic global health funders, as well as from funding databases.

The researchers ranked 45 countries according to the level of malaria research funding they received.

All of the countries studied received funding for malaria control, which includes investment for bed nets, public health schemes, and antimalarial drugs.

However, 8 of the 45 countries did not receive any funding related to malaria research. This included Central African Republic, Sierra Leone, and Congo—countries with a “reasonably high” malaria burden/mortality rate, according to Dr Head and his colleagues.

In all, there were 333 research awards, totaling $814.4 million. The countries that received the most research funding were Tanzania ($107.8 million), Uganda ($97.9 million), and Kenya ($92.9 million).

The 8 countries that received no research funding were Cape Verde, Botswana, Djibouti, Central African Republic, Mauritania, Congo, Chad, and Sierra Leone.

Dr Head and his colleagues suggested that the reason for the disparity in funding allocation could be, in part, due to the presence of established high-quality research infrastructure in countries such as Tanzania and Kenya, and political instability and poor healthcare infrastructures in lower-ranked nations such as Central African Republic or Sierra Leone.

“[N]ew investment in malaria research and development in these areas can encourage the development of improved health systems,” Dr Head said. “Many countries in sub-Saharan Africa simply do not have an established research infrastructure, and it is difficult for research funders to make investments in these settings.”

“Ultimately, however, there are neglected populations in these countries who suffer greatly from malaria and other diseases. Investments in health improve the wealth of a nation, and we need to be smarter with allocating limited resources to best help to reduce clear health inequalities.” ![]()

A new study has revealed inequalities in malaria research funding in sub-Saharan Africa.

The study showed that some countries with a high malaria burden—such as Sierra Leone, Congo, Central African Republic, and Guinea—received little to no funding for malaria research in recent years.

However, other countries—such as Tanzania, Uganda, and Kenya—received close to $100 million in funding for malaria research.

Michael Head, PhD, of the University of Southampton in the UK, and his colleagues reported these findings in The Lancet Global Health.

“We have been able to provide a comprehensive overview of the landscape of funding for malaria in sub-Saharan Africa, a massive area where around 90% of worldwide malaria cases occur,” Dr Head said.

“We’ve shown that there are countries that are being neglected, and the global health community should reconsider strategies around resource allocation to reduce inequities and improve equality.”

For this study, Dr Head and his colleagues analyzed funding data spanning the period from 1997 to 2013. The data were sourced from 13 major public and philanthropic global health funders, as well as from funding databases.

The researchers ranked 45 countries according to the level of malaria research funding they received.

All of the countries studied received funding for malaria control, which includes investment for bed nets, public health schemes, and antimalarial drugs.

However, 8 of the 45 countries did not receive any funding related to malaria research. This included Central African Republic, Sierra Leone, and Congo—countries with a “reasonably high” malaria burden/mortality rate, according to Dr Head and his colleagues.

In all, there were 333 research awards, totaling $814.4 million. The countries that received the most research funding were Tanzania ($107.8 million), Uganda ($97.9 million), and Kenya ($92.9 million).

The 8 countries that received no research funding were Cape Verde, Botswana, Djibouti, Central African Republic, Mauritania, Congo, Chad, and Sierra Leone.

Dr Head and his colleagues suggested that the reason for the disparity in funding allocation could be, in part, due to the presence of established high-quality research infrastructure in countries such as Tanzania and Kenya, and political instability and poor healthcare infrastructures in lower-ranked nations such as Central African Republic or Sierra Leone.

“[N]ew investment in malaria research and development in these areas can encourage the development of improved health systems,” Dr Head said. “Many countries in sub-Saharan Africa simply do not have an established research infrastructure, and it is difficult for research funders to make investments in these settings.”

“Ultimately, however, there are neglected populations in these countries who suffer greatly from malaria and other diseases. Investments in health improve the wealth of a nation, and we need to be smarter with allocating limited resources to best help to reduce clear health inequalities.” ![]()

FDA unveils plan to eliminate orphan designation backlog

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has unveiled a plan to eliminate the agency’s existing backlog of orphan designation requests and ensure timely responses to all new requests with firm deadlines.

The agency’s Orphan Drug Modernization Plan comes a week after FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb committed to eliminating the backlog within 90 days and responding to all new requests for designation within 90 days of receipt during his testimony before a Senate subcommittee.

As authorized under the Orphan Drug Act, the Orphan Drug Designation Program provides orphan status to drugs and biologics intended for the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of rare diseases, which are generally defined as diseases that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

Orphan designation qualifies a product’s developer for various development incentives, including tax credits for clinical trial costs, relief from prescription drug user fee if the indication is for a rare disease or condition, and eligibility for 7 years of marketing exclusivity if the product is approved.

A request for orphan designation is one step that can be taken in the development process and is different than the filing of a marketing application with the FDA.

Currently, the FDA has about 200 orphan drug designation requests that are pending review. The number of orphan drug designation requests has steadily increased over the past 5 years.

In 2016, the FDA’s Office of Orphan Products Development received 568 new requests for designation – more than double the number of requests received in 2012.

The FDA says this increased interest in the program is a positive development for patients with rare diseases, and, with the Orphan Drug Modernization Plan, the FDA is committing to advancing the program to ensure it can efficiently and adequately review these requests.

“People who suffer with rare diseases are too often faced with no or limited treatment options, and what treatment options they have may be quite expensive due, in part, to significant costs of developing therapies for smaller populations,” said FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD.

“Congress gave us tools to incentivize the development of novel therapies for rare diseases, and we intend to use these resources to their fullest extent in order to ensure Americans get the safe and effective medicines they need, and that the process for developing these innovations is as modern and efficient as possible.”

Among the elements of the Orphan Drug Modernization Plan, the FDA will deploy a Backlog SWAT team comprised of senior, experienced reviewers with significant expertise in orphan drug designation. The team will focus solely on the backlogged applications, starting with the oldest requests.

The agency will also employ a streamlined Designation Review Template to increase consistency and efficiency of its reviews.

In addition, the Orphan Drug Designation Program will look to collaborate within the agency’s medical product centers to create greater efficiency, including conducting joint reviews with the Office of Pediatric Therapeutics to review rare pediatric disease designation requests.

To ensure all future requests receive a response within 90 days of receipt, the FDA will take a multifaceted approach.

These efforts include, among other new steps:

- Reorganizing the review staff to maximize expertise and improve workload efficiencies

- Better leveraging the expertise across the FDA’s medical product centers

- Establishing a new FDA Orphan Products Council that will help address scientific and regulatory issues to ensure the agency is applying a consistent approach to regulating orphan drug products and reviewing designation requests.

The FDA is planning for the backlog to be eliminated by mid-September.

The Orphan Drug Modernization Plan is the first element of several efforts the FDA plans to undertake under its new “Medical Innovation Development Plan,” which is aimed at ensuring the FDA’s regulatory tools and policies are modern, risk-based, and efficient.

The goal of the plan is to seek ways the FDA can help facilitate the development of safe, effective, and transformative medical innovations that have the potential to significantly impact disease and reduce overall healthcare costs. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has unveiled a plan to eliminate the agency’s existing backlog of orphan designation requests and ensure timely responses to all new requests with firm deadlines.

The agency’s Orphan Drug Modernization Plan comes a week after FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb committed to eliminating the backlog within 90 days and responding to all new requests for designation within 90 days of receipt during his testimony before a Senate subcommittee.

As authorized under the Orphan Drug Act, the Orphan Drug Designation Program provides orphan status to drugs and biologics intended for the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of rare diseases, which are generally defined as diseases that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

Orphan designation qualifies a product’s developer for various development incentives, including tax credits for clinical trial costs, relief from prescription drug user fee if the indication is for a rare disease or condition, and eligibility for 7 years of marketing exclusivity if the product is approved.

A request for orphan designation is one step that can be taken in the development process and is different than the filing of a marketing application with the FDA.

Currently, the FDA has about 200 orphan drug designation requests that are pending review. The number of orphan drug designation requests has steadily increased over the past 5 years.

In 2016, the FDA’s Office of Orphan Products Development received 568 new requests for designation – more than double the number of requests received in 2012.

The FDA says this increased interest in the program is a positive development for patients with rare diseases, and, with the Orphan Drug Modernization Plan, the FDA is committing to advancing the program to ensure it can efficiently and adequately review these requests.

“People who suffer with rare diseases are too often faced with no or limited treatment options, and what treatment options they have may be quite expensive due, in part, to significant costs of developing therapies for smaller populations,” said FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD.

“Congress gave us tools to incentivize the development of novel therapies for rare diseases, and we intend to use these resources to their fullest extent in order to ensure Americans get the safe and effective medicines they need, and that the process for developing these innovations is as modern and efficient as possible.”

Among the elements of the Orphan Drug Modernization Plan, the FDA will deploy a Backlog SWAT team comprised of senior, experienced reviewers with significant expertise in orphan drug designation. The team will focus solely on the backlogged applications, starting with the oldest requests.

The agency will also employ a streamlined Designation Review Template to increase consistency and efficiency of its reviews.

In addition, the Orphan Drug Designation Program will look to collaborate within the agency’s medical product centers to create greater efficiency, including conducting joint reviews with the Office of Pediatric Therapeutics to review rare pediatric disease designation requests.

To ensure all future requests receive a response within 90 days of receipt, the FDA will take a multifaceted approach.

These efforts include, among other new steps:

- Reorganizing the review staff to maximize expertise and improve workload efficiencies

- Better leveraging the expertise across the FDA’s medical product centers

- Establishing a new FDA Orphan Products Council that will help address scientific and regulatory issues to ensure the agency is applying a consistent approach to regulating orphan drug products and reviewing designation requests.

The FDA is planning for the backlog to be eliminated by mid-September.

The Orphan Drug Modernization Plan is the first element of several efforts the FDA plans to undertake under its new “Medical Innovation Development Plan,” which is aimed at ensuring the FDA’s regulatory tools and policies are modern, risk-based, and efficient.

The goal of the plan is to seek ways the FDA can help facilitate the development of safe, effective, and transformative medical innovations that have the potential to significantly impact disease and reduce overall healthcare costs. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has unveiled a plan to eliminate the agency’s existing backlog of orphan designation requests and ensure timely responses to all new requests with firm deadlines.

The agency’s Orphan Drug Modernization Plan comes a week after FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb committed to eliminating the backlog within 90 days and responding to all new requests for designation within 90 days of receipt during his testimony before a Senate subcommittee.

As authorized under the Orphan Drug Act, the Orphan Drug Designation Program provides orphan status to drugs and biologics intended for the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of rare diseases, which are generally defined as diseases that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

Orphan designation qualifies a product’s developer for various development incentives, including tax credits for clinical trial costs, relief from prescription drug user fee if the indication is for a rare disease or condition, and eligibility for 7 years of marketing exclusivity if the product is approved.

A request for orphan designation is one step that can be taken in the development process and is different than the filing of a marketing application with the FDA.

Currently, the FDA has about 200 orphan drug designation requests that are pending review. The number of orphan drug designation requests has steadily increased over the past 5 years.

In 2016, the FDA’s Office of Orphan Products Development received 568 new requests for designation – more than double the number of requests received in 2012.

The FDA says this increased interest in the program is a positive development for patients with rare diseases, and, with the Orphan Drug Modernization Plan, the FDA is committing to advancing the program to ensure it can efficiently and adequately review these requests.

“People who suffer with rare diseases are too often faced with no or limited treatment options, and what treatment options they have may be quite expensive due, in part, to significant costs of developing therapies for smaller populations,” said FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD.

“Congress gave us tools to incentivize the development of novel therapies for rare diseases, and we intend to use these resources to their fullest extent in order to ensure Americans get the safe and effective medicines they need, and that the process for developing these innovations is as modern and efficient as possible.”

Among the elements of the Orphan Drug Modernization Plan, the FDA will deploy a Backlog SWAT team comprised of senior, experienced reviewers with significant expertise in orphan drug designation. The team will focus solely on the backlogged applications, starting with the oldest requests.

The agency will also employ a streamlined Designation Review Template to increase consistency and efficiency of its reviews.

In addition, the Orphan Drug Designation Program will look to collaborate within the agency’s medical product centers to create greater efficiency, including conducting joint reviews with the Office of Pediatric Therapeutics to review rare pediatric disease designation requests.

To ensure all future requests receive a response within 90 days of receipt, the FDA will take a multifaceted approach.

These efforts include, among other new steps:

- Reorganizing the review staff to maximize expertise and improve workload efficiencies

- Better leveraging the expertise across the FDA’s medical product centers

- Establishing a new FDA Orphan Products Council that will help address scientific and regulatory issues to ensure the agency is applying a consistent approach to regulating orphan drug products and reviewing designation requests.

The FDA is planning for the backlog to be eliminated by mid-September.

The Orphan Drug Modernization Plan is the first element of several efforts the FDA plans to undertake under its new “Medical Innovation Development Plan,” which is aimed at ensuring the FDA’s regulatory tools and policies are modern, risk-based, and efficient.

The goal of the plan is to seek ways the FDA can help facilitate the development of safe, effective, and transformative medical innovations that have the potential to significantly impact disease and reduce overall healthcare costs. ![]()

Single-dose NEPA found non-inferior to aprepitant/granisetron

WASHINGTON, DC—In a head-to-head study comparing a single-dose oral antiemetic to a 3-day oral regimen, the single dose has shown itself to be non-inferior to the multi-day regimen in preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV).

The investigators evaluated netupitant/palonosetron (NEPA) against aprepitant/granisetron (APR/GRAN) in patients on highly emetogenic chemotherapy.

They found the data suggest “that NEPA, in a single dose, had equivalent efficacy to a 3-day oral aprepitant/granisetron regimen,” according to the lead investigator and abstract presenter.

Li Zhang, MD, of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center in Guangzhou, China, presented the data at the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer/International Society of Oral Oncology (MASCC/ISOO) Congress (abstract PS049, pp S55 – S56).

NEPA is a combination of the selective NK1RA netupitant (300 mg) and the clinically and pharmacologically active 5-HT3RA, palonosetron (0.5 mg) for the prevention of CINV.

Oral palonosetron prevents nausea and vomiting during the acute phase of treatment.

Netupitant prevents nausea and vomiting during both the acute and delayed phase after cancer chemotherapy.

It is formulated into a single oral capsule.

Study design

The study was a phase 3 randomized, double-blind, double-dummy study conducted in 828 chemotherapy-naïve Asian patients receiving cisplatin-based highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC) agents.

Patients received a single oral dose of NEPA on day 1 or a 3-day oral APR/GRAN regimen (days 1-3).

All patients received oral dexamethasone on days 1-4.

The primary efficacy endpoint was complete response (CR), defined as no emesis or rescue medication needed during the overall (0-120 hour) phase.

The investigators defined non-inferiority to be the lower limit of the two-sided 95% confidence interval greater than the non-inferiority margin set at ̶ 10%.

Secondary endpoints included no emesis, no rescue medication, and no significant nausea (NSN), defined as <25 mm on 100 mm visual analog scale (VAS).

Results

The baseline demographics were comparable between the NEPA (n=413) and APR/GRAN (n=416) arms: 71% of the patients were male, a mean age of 55 years, and a little more than half were ECOG performance status 1.

The most common cancer types were lung and head and neck cancer.

Patients had received a median cisplatin dose of 73 and 72 mg/m2 in the NEPA and APR/GRAN arms, respectively.

Within the first 24 hours (acute phase), NEPA was non-inferior to APR/GRAN. NEPA had a CR rate of 84.5% and APR/GRAN had a CR rate of 87.0%. The risk difference between the 2 agents was -2.5% (range, -7.2%, 2.3%).

In the delayed phase (25-120 hours), NEPA had a CR rate of 77.9% and APR/GRAN, 74.3%. The risk difference was 3.7% (range, -2.1%, 9.5%).

Overall, for both phases, the CR rate was 73.8% for NEPA and 72.4% for APR/GRAN. The risk difference was 1.5% (range, -4.5%, 7.5%).

Dr Zhang pointed out that although the overall CR rates were similar, the daily rates of patients experiencing CINV remained in the range of 13% - 15% for patients in the APR/GRAN arm.

However, daily rates of CINV for patients receiving NEPA declined from 16% to 8% over the 5 days. The investigators believe this suggests a benefit for delayed CINV.

Regarding secondary endpoints, significantly more patients receiving NEPA did not require rescue medication in the delayed phase and overall than patients in the APR/GRAN arm.

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were comparable between the arms—58.1% in the NEPA arm and 57.5% in the APR/GRAN arm, as were serious TEAS, at 4.5% and 4.6% for NEPA and APR/GRAN, respectively. And the no emesis and no significant nausea rates favored NEPA.

The most common treatment-emergent adverse events occurring in 2% or more of the patients in both arms were constipation and hiccups.

Two serious treatment-related adverse events occurred in each arm, 1 leading to discontinuation in the NEPA arm.

The investigators concluded that NEPA, as a convenient capsule administered once per cycle, is at least as effective as the 3-day regimen of APR/GRAN in patients receiving HEC.

NEPA (Akynzeo®) is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and marketed globally by Helsinn, Lugano, Switzerland, the sponsor of the trial.

For the full US prescribing information, see the package insert.

WASHINGTON, DC—In a head-to-head study comparing a single-dose oral antiemetic to a 3-day oral regimen, the single dose has shown itself to be non-inferior to the multi-day regimen in preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV).

The investigators evaluated netupitant/palonosetron (NEPA) against aprepitant/granisetron (APR/GRAN) in patients on highly emetogenic chemotherapy.

They found the data suggest “that NEPA, in a single dose, had equivalent efficacy to a 3-day oral aprepitant/granisetron regimen,” according to the lead investigator and abstract presenter.

Li Zhang, MD, of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center in Guangzhou, China, presented the data at the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer/International Society of Oral Oncology (MASCC/ISOO) Congress (abstract PS049, pp S55 – S56).

NEPA is a combination of the selective NK1RA netupitant (300 mg) and the clinically and pharmacologically active 5-HT3RA, palonosetron (0.5 mg) for the prevention of CINV.

Oral palonosetron prevents nausea and vomiting during the acute phase of treatment.

Netupitant prevents nausea and vomiting during both the acute and delayed phase after cancer chemotherapy.

It is formulated into a single oral capsule.

Study design

The study was a phase 3 randomized, double-blind, double-dummy study conducted in 828 chemotherapy-naïve Asian patients receiving cisplatin-based highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC) agents.

Patients received a single oral dose of NEPA on day 1 or a 3-day oral APR/GRAN regimen (days 1-3).

All patients received oral dexamethasone on days 1-4.

The primary efficacy endpoint was complete response (CR), defined as no emesis or rescue medication needed during the overall (0-120 hour) phase.

The investigators defined non-inferiority to be the lower limit of the two-sided 95% confidence interval greater than the non-inferiority margin set at ̶ 10%.

Secondary endpoints included no emesis, no rescue medication, and no significant nausea (NSN), defined as <25 mm on 100 mm visual analog scale (VAS).

Results

The baseline demographics were comparable between the NEPA (n=413) and APR/GRAN (n=416) arms: 71% of the patients were male, a mean age of 55 years, and a little more than half were ECOG performance status 1.

The most common cancer types were lung and head and neck cancer.

Patients had received a median cisplatin dose of 73 and 72 mg/m2 in the NEPA and APR/GRAN arms, respectively.

Within the first 24 hours (acute phase), NEPA was non-inferior to APR/GRAN. NEPA had a CR rate of 84.5% and APR/GRAN had a CR rate of 87.0%. The risk difference between the 2 agents was -2.5% (range, -7.2%, 2.3%).

In the delayed phase (25-120 hours), NEPA had a CR rate of 77.9% and APR/GRAN, 74.3%. The risk difference was 3.7% (range, -2.1%, 9.5%).

Overall, for both phases, the CR rate was 73.8% for NEPA and 72.4% for APR/GRAN. The risk difference was 1.5% (range, -4.5%, 7.5%).

Dr Zhang pointed out that although the overall CR rates were similar, the daily rates of patients experiencing CINV remained in the range of 13% - 15% for patients in the APR/GRAN arm.

However, daily rates of CINV for patients receiving NEPA declined from 16% to 8% over the 5 days. The investigators believe this suggests a benefit for delayed CINV.

Regarding secondary endpoints, significantly more patients receiving NEPA did not require rescue medication in the delayed phase and overall than patients in the APR/GRAN arm.

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were comparable between the arms—58.1% in the NEPA arm and 57.5% in the APR/GRAN arm, as were serious TEAS, at 4.5% and 4.6% for NEPA and APR/GRAN, respectively. And the no emesis and no significant nausea rates favored NEPA.

The most common treatment-emergent adverse events occurring in 2% or more of the patients in both arms were constipation and hiccups.

Two serious treatment-related adverse events occurred in each arm, 1 leading to discontinuation in the NEPA arm.

The investigators concluded that NEPA, as a convenient capsule administered once per cycle, is at least as effective as the 3-day regimen of APR/GRAN in patients receiving HEC.

NEPA (Akynzeo®) is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and marketed globally by Helsinn, Lugano, Switzerland, the sponsor of the trial.

For the full US prescribing information, see the package insert.

WASHINGTON, DC—In a head-to-head study comparing a single-dose oral antiemetic to a 3-day oral regimen, the single dose has shown itself to be non-inferior to the multi-day regimen in preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV).

The investigators evaluated netupitant/palonosetron (NEPA) against aprepitant/granisetron (APR/GRAN) in patients on highly emetogenic chemotherapy.

They found the data suggest “that NEPA, in a single dose, had equivalent efficacy to a 3-day oral aprepitant/granisetron regimen,” according to the lead investigator and abstract presenter.

Li Zhang, MD, of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center in Guangzhou, China, presented the data at the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer/International Society of Oral Oncology (MASCC/ISOO) Congress (abstract PS049, pp S55 – S56).

NEPA is a combination of the selective NK1RA netupitant (300 mg) and the clinically and pharmacologically active 5-HT3RA, palonosetron (0.5 mg) for the prevention of CINV.

Oral palonosetron prevents nausea and vomiting during the acute phase of treatment.

Netupitant prevents nausea and vomiting during both the acute and delayed phase after cancer chemotherapy.

It is formulated into a single oral capsule.

Study design

The study was a phase 3 randomized, double-blind, double-dummy study conducted in 828 chemotherapy-naïve Asian patients receiving cisplatin-based highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC) agents.

Patients received a single oral dose of NEPA on day 1 or a 3-day oral APR/GRAN regimen (days 1-3).

All patients received oral dexamethasone on days 1-4.

The primary efficacy endpoint was complete response (CR), defined as no emesis or rescue medication needed during the overall (0-120 hour) phase.

The investigators defined non-inferiority to be the lower limit of the two-sided 95% confidence interval greater than the non-inferiority margin set at ̶ 10%.

Secondary endpoints included no emesis, no rescue medication, and no significant nausea (NSN), defined as <25 mm on 100 mm visual analog scale (VAS).

Results

The baseline demographics were comparable between the NEPA (n=413) and APR/GRAN (n=416) arms: 71% of the patients were male, a mean age of 55 years, and a little more than half were ECOG performance status 1.

The most common cancer types were lung and head and neck cancer.

Patients had received a median cisplatin dose of 73 and 72 mg/m2 in the NEPA and APR/GRAN arms, respectively.

Within the first 24 hours (acute phase), NEPA was non-inferior to APR/GRAN. NEPA had a CR rate of 84.5% and APR/GRAN had a CR rate of 87.0%. The risk difference between the 2 agents was -2.5% (range, -7.2%, 2.3%).

In the delayed phase (25-120 hours), NEPA had a CR rate of 77.9% and APR/GRAN, 74.3%. The risk difference was 3.7% (range, -2.1%, 9.5%).

Overall, for both phases, the CR rate was 73.8% for NEPA and 72.4% for APR/GRAN. The risk difference was 1.5% (range, -4.5%, 7.5%).

Dr Zhang pointed out that although the overall CR rates were similar, the daily rates of patients experiencing CINV remained in the range of 13% - 15% for patients in the APR/GRAN arm.

However, daily rates of CINV for patients receiving NEPA declined from 16% to 8% over the 5 days. The investigators believe this suggests a benefit for delayed CINV.

Regarding secondary endpoints, significantly more patients receiving NEPA did not require rescue medication in the delayed phase and overall than patients in the APR/GRAN arm.

Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were comparable between the arms—58.1% in the NEPA arm and 57.5% in the APR/GRAN arm, as were serious TEAS, at 4.5% and 4.6% for NEPA and APR/GRAN, respectively. And the no emesis and no significant nausea rates favored NEPA.

The most common treatment-emergent adverse events occurring in 2% or more of the patients in both arms were constipation and hiccups.

Two serious treatment-related adverse events occurred in each arm, 1 leading to discontinuation in the NEPA arm.

The investigators concluded that NEPA, as a convenient capsule administered once per cycle, is at least as effective as the 3-day regimen of APR/GRAN in patients receiving HEC.

NEPA (Akynzeo®) is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and marketed globally by Helsinn, Lugano, Switzerland, the sponsor of the trial.

For the full US prescribing information, see the package insert.

Developments on the malaria front

Progress is being made in the battle against malaria. From engineering a mosquito-killing fungus to discovering new anti-malaria targets, scientists are making advances on multiple malaria fronts.

And US aid to combat malaria is having a positive impact on reducing childhood mortality in 19 sub-Saharan countries. A few of the recent developments are described here.

Genetic engineering

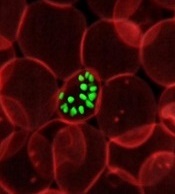

Scientists developed a genetic technique that disrupts the heme synthesis pathway in Plasmodium berghei parasites, which could be an effective way to target Plasmodium parasites in the liver.

Heme synthesis is essential for P berghei development in mosquitoes that transmit the parasite between rodent hosts. However, the pathway is not essential during a later stage of the parasite’s development in the bloodstream.

So researchers produced P berghei parasites capable of expressing the FC gene. The FC (ferrochelatase) gene allows P berghei to produce heme. The parasites could develop properly in mosquitoes, but produced some FC-deficient parasites once they infected mouse liver cells.

FC-deficient parasites were unable to complete their liver development phase.

The team says this approach would be prophylactic, since malaria symptoms aren't apparent until the parasite leaves the liver and begins its bloodstream phase.

The team published its findings in PLOS Pathogens.

Mosquito-killing fungi

In a report that sounds almost like a science fiction story, researchers genetically engineered a fungus to kill mosquitoes by producing spider and scorpion toxins.

They suggest this method could serve as a highly effective biological control mechanism to fight malaria-carrying mosquitoes.

The researchers isolated genes that express neurotoxins from the venom of scorpions and spiders. They then engineered the genes into the fungus's DNA.

The researchers used the fungus Metarhizium pingshaensei, which is a natural killer of mosquitoes.

The fungus was originally isolated from a mosquito and previous evidence suggests it is specific to disease-carrying mosquito species, including Anopheles gambiae and Aedes aegypti.

When spores of the fungus contact a mosquito's body, the spores germinate and penetrate the insect's exoskeleton, eventually killing the insect host from the inside out.

And the most potent fungal strains, Brian Lovett, a graduate student at the University of Maryland in College Park, explained, “are able to kill mosquitoes with a single spore."

He added that the fungi also stop mosquitoes from blood feeding. Taken together, this means “that our fungal strains are capable of preventing transmission of disease by more than 90 percent of mosquitoes after just 5 days."

The fungus is specific to mosquitoes and does not pose a risk to humans. The study results also suggest the fungus is safe for honeybees and other insects.

The researchers plan to expand on-the-ground testing in Burkina Faso.

For more on this mosquito-killing approach, see their study published in Scientific Reports.

Potential new target

Researchers have described a new protein, the transcription factor PfAP2-I, which they say may turn out to be an effective target to combat drug-resistant malaria parasites.

PfAP2-I regulates genes involved with the parasite's invasion of red blood cells. This is a critical part of the parasite's 3-stage life cycle that could be targeted by new anti-malarial drugs.

“Most multi-celled organisms have hundreds of these regulators,” said lead author Manuel Llinás, PhD, of Penn State University in State College, Pennsylvania, “but it turns out, so far as we can recognize, the [Plasmodium] parasite has a single family of transcription factors called Apicomplexan AP2 proteins. One of these transcription factors is PfAP2-I."

PfAP2-I is the first known regulator of invasion genes in Plasmodium falciparum.

The new study also indicates that PfAP2-I likely recruits another protein, Bromodomain Protein 1 (PfBDP1), which was previously shown to be involved in the invasion of red blood cells.

The two proteins may work together to regulate gene transcription during this critical stage of infection.

For more on this potential new target, see their study published in Cell Host & Microbe.

Parasite diversity

Not all malaria infections result in life-threatening anemia and organ failure, and so a research team led by Matthew B. B. McCall, MD, PhD, of Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, set out to determine why.

They exposed 23 healthy human volunteers to sets of 5 mosquitoes carrying the NF54, NF135.C10, or NF166.C8 isolates of P falciparum.

All volunteers developed parasitemia, were treated with anti-malarial drugs, and recovered, although some strains caused more severe symptoms.

The investigators found that 3 geographic and genetically diverse forms of the parasite each demonstrated a distinct ability to infect liver cells.

They also observed the degree of infection in human liver cells growing in culture was closely correlated with parasite loads in the bloodstream.

The investigators believe the variability among parasite types suggests that malaria vaccines should use multiple strains.

In addition, the infectivity of different parasite strains could vary in populations previously exposed to malaria.

For more details on parasite diversity, see the team’s findings in Science Translational Medicine.

Malaria test

A new malaria test can diagnose malaria faster and more reliably than current methods, according to a report in the NL Times.

The new test uses an algorithm that can diagnose malaria at a rate of 120 blood tests per hour. It is 97% accurate.

Rather than search for the parasite itself in blood samples, the new test analyzes the effect the infection has on the blood, such as shape and density of red blood cells, hemoglobin level, and 27 other parameters simultaneously.

The developers won the European Inventor Award for the rapid malaria test, which will be further developed by Siemens.

Aid to combat malaria

The US malaria initiative in 19 sub-Saharan African countries has contributed to a 16% reduction in the annual risk of mortality for children under 5 years, according to a new study published in PLOS Medicine.

Thirteen sub-Saharan countries did not receive funding from the initiative, which allowed researchers to compare and analyze the impact of the intervention.

Because the study may have had confounding variables that were not measured, however, the results could not be definitively interpreted as causal evidence of the reduction in child mortality rates.

However, they do indicate an association between the receipt of funding and mortality.

The funding went to support malaria prevention technologies, such as insecticide-treated nets and indoor residual spraying.

The authors believe further investment in these interventions “may translate to additional lives saved, reduced household financial burdens associated with caring for ill household members and lost wages, and less strain on health systems associated with treating malaria cases.”

Countries that received funding included: Angola, Benin, Congo DRC, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

Comparison countries include: Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Chad, Congo, Cote d’Ivoire, Gabon, Namibia, Niger, Sierra Leone, Swaziland, The Gambia, and Togo. ![]()

Progress is being made in the battle against malaria. From engineering a mosquito-killing fungus to discovering new anti-malaria targets, scientists are making advances on multiple malaria fronts.

And US aid to combat malaria is having a positive impact on reducing childhood mortality in 19 sub-Saharan countries. A few of the recent developments are described here.

Genetic engineering

Scientists developed a genetic technique that disrupts the heme synthesis pathway in Plasmodium berghei parasites, which could be an effective way to target Plasmodium parasites in the liver.

Heme synthesis is essential for P berghei development in mosquitoes that transmit the parasite between rodent hosts. However, the pathway is not essential during a later stage of the parasite’s development in the bloodstream.

So researchers produced P berghei parasites capable of expressing the FC gene. The FC (ferrochelatase) gene allows P berghei to produce heme. The parasites could develop properly in mosquitoes, but produced some FC-deficient parasites once they infected mouse liver cells.

FC-deficient parasites were unable to complete their liver development phase.

The team says this approach would be prophylactic, since malaria symptoms aren't apparent until the parasite leaves the liver and begins its bloodstream phase.

The team published its findings in PLOS Pathogens.

Mosquito-killing fungi

In a report that sounds almost like a science fiction story, researchers genetically engineered a fungus to kill mosquitoes by producing spider and scorpion toxins.

They suggest this method could serve as a highly effective biological control mechanism to fight malaria-carrying mosquitoes.

The researchers isolated genes that express neurotoxins from the venom of scorpions and spiders. They then engineered the genes into the fungus's DNA.

The researchers used the fungus Metarhizium pingshaensei, which is a natural killer of mosquitoes.

The fungus was originally isolated from a mosquito and previous evidence suggests it is specific to disease-carrying mosquito species, including Anopheles gambiae and Aedes aegypti.

When spores of the fungus contact a mosquito's body, the spores germinate and penetrate the insect's exoskeleton, eventually killing the insect host from the inside out.

And the most potent fungal strains, Brian Lovett, a graduate student at the University of Maryland in College Park, explained, “are able to kill mosquitoes with a single spore."

He added that the fungi also stop mosquitoes from blood feeding. Taken together, this means “that our fungal strains are capable of preventing transmission of disease by more than 90 percent of mosquitoes after just 5 days."

The fungus is specific to mosquitoes and does not pose a risk to humans. The study results also suggest the fungus is safe for honeybees and other insects.

The researchers plan to expand on-the-ground testing in Burkina Faso.

For more on this mosquito-killing approach, see their study published in Scientific Reports.

Potential new target

Researchers have described a new protein, the transcription factor PfAP2-I, which they say may turn out to be an effective target to combat drug-resistant malaria parasites.

PfAP2-I regulates genes involved with the parasite's invasion of red blood cells. This is a critical part of the parasite's 3-stage life cycle that could be targeted by new anti-malarial drugs.

“Most multi-celled organisms have hundreds of these regulators,” said lead author Manuel Llinás, PhD, of Penn State University in State College, Pennsylvania, “but it turns out, so far as we can recognize, the [Plasmodium] parasite has a single family of transcription factors called Apicomplexan AP2 proteins. One of these transcription factors is PfAP2-I."

PfAP2-I is the first known regulator of invasion genes in Plasmodium falciparum.

The new study also indicates that PfAP2-I likely recruits another protein, Bromodomain Protein 1 (PfBDP1), which was previously shown to be involved in the invasion of red blood cells.

The two proteins may work together to regulate gene transcription during this critical stage of infection.

For more on this potential new target, see their study published in Cell Host & Microbe.

Parasite diversity

Not all malaria infections result in life-threatening anemia and organ failure, and so a research team led by Matthew B. B. McCall, MD, PhD, of Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, set out to determine why.

They exposed 23 healthy human volunteers to sets of 5 mosquitoes carrying the NF54, NF135.C10, or NF166.C8 isolates of P falciparum.

All volunteers developed parasitemia, were treated with anti-malarial drugs, and recovered, although some strains caused more severe symptoms.

The investigators found that 3 geographic and genetically diverse forms of the parasite each demonstrated a distinct ability to infect liver cells.

They also observed the degree of infection in human liver cells growing in culture was closely correlated with parasite loads in the bloodstream.

The investigators believe the variability among parasite types suggests that malaria vaccines should use multiple strains.

In addition, the infectivity of different parasite strains could vary in populations previously exposed to malaria.

For more details on parasite diversity, see the team’s findings in Science Translational Medicine.

Malaria test

A new malaria test can diagnose malaria faster and more reliably than current methods, according to a report in the NL Times.

The new test uses an algorithm that can diagnose malaria at a rate of 120 blood tests per hour. It is 97% accurate.

Rather than search for the parasite itself in blood samples, the new test analyzes the effect the infection has on the blood, such as shape and density of red blood cells, hemoglobin level, and 27 other parameters simultaneously.

The developers won the European Inventor Award for the rapid malaria test, which will be further developed by Siemens.

Aid to combat malaria

The US malaria initiative in 19 sub-Saharan African countries has contributed to a 16% reduction in the annual risk of mortality for children under 5 years, according to a new study published in PLOS Medicine.

Thirteen sub-Saharan countries did not receive funding from the initiative, which allowed researchers to compare and analyze the impact of the intervention.

Because the study may have had confounding variables that were not measured, however, the results could not be definitively interpreted as causal evidence of the reduction in child mortality rates.

However, they do indicate an association between the receipt of funding and mortality.

The funding went to support malaria prevention technologies, such as insecticide-treated nets and indoor residual spraying.

The authors believe further investment in these interventions “may translate to additional lives saved, reduced household financial burdens associated with caring for ill household members and lost wages, and less strain on health systems associated with treating malaria cases.”

Countries that received funding included: Angola, Benin, Congo DRC, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

Comparison countries include: Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Chad, Congo, Cote d’Ivoire, Gabon, Namibia, Niger, Sierra Leone, Swaziland, The Gambia, and Togo. ![]()

Progress is being made in the battle against malaria. From engineering a mosquito-killing fungus to discovering new anti-malaria targets, scientists are making advances on multiple malaria fronts.

And US aid to combat malaria is having a positive impact on reducing childhood mortality in 19 sub-Saharan countries. A few of the recent developments are described here.

Genetic engineering

Scientists developed a genetic technique that disrupts the heme synthesis pathway in Plasmodium berghei parasites, which could be an effective way to target Plasmodium parasites in the liver.

Heme synthesis is essential for P berghei development in mosquitoes that transmit the parasite between rodent hosts. However, the pathway is not essential during a later stage of the parasite’s development in the bloodstream.

So researchers produced P berghei parasites capable of expressing the FC gene. The FC (ferrochelatase) gene allows P berghei to produce heme. The parasites could develop properly in mosquitoes, but produced some FC-deficient parasites once they infected mouse liver cells.

FC-deficient parasites were unable to complete their liver development phase.

The team says this approach would be prophylactic, since malaria symptoms aren't apparent until the parasite leaves the liver and begins its bloodstream phase.

The team published its findings in PLOS Pathogens.

Mosquito-killing fungi

In a report that sounds almost like a science fiction story, researchers genetically engineered a fungus to kill mosquitoes by producing spider and scorpion toxins.

They suggest this method could serve as a highly effective biological control mechanism to fight malaria-carrying mosquitoes.

The researchers isolated genes that express neurotoxins from the venom of scorpions and spiders. They then engineered the genes into the fungus's DNA.

The researchers used the fungus Metarhizium pingshaensei, which is a natural killer of mosquitoes.

The fungus was originally isolated from a mosquito and previous evidence suggests it is specific to disease-carrying mosquito species, including Anopheles gambiae and Aedes aegypti.

When spores of the fungus contact a mosquito's body, the spores germinate and penetrate the insect's exoskeleton, eventually killing the insect host from the inside out.

And the most potent fungal strains, Brian Lovett, a graduate student at the University of Maryland in College Park, explained, “are able to kill mosquitoes with a single spore."

He added that the fungi also stop mosquitoes from blood feeding. Taken together, this means “that our fungal strains are capable of preventing transmission of disease by more than 90 percent of mosquitoes after just 5 days."

The fungus is specific to mosquitoes and does not pose a risk to humans. The study results also suggest the fungus is safe for honeybees and other insects.

The researchers plan to expand on-the-ground testing in Burkina Faso.

For more on this mosquito-killing approach, see their study published in Scientific Reports.

Potential new target

Researchers have described a new protein, the transcription factor PfAP2-I, which they say may turn out to be an effective target to combat drug-resistant malaria parasites.

PfAP2-I regulates genes involved with the parasite's invasion of red blood cells. This is a critical part of the parasite's 3-stage life cycle that could be targeted by new anti-malarial drugs.

“Most multi-celled organisms have hundreds of these regulators,” said lead author Manuel Llinás, PhD, of Penn State University in State College, Pennsylvania, “but it turns out, so far as we can recognize, the [Plasmodium] parasite has a single family of transcription factors called Apicomplexan AP2 proteins. One of these transcription factors is PfAP2-I."

PfAP2-I is the first known regulator of invasion genes in Plasmodium falciparum.

The new study also indicates that PfAP2-I likely recruits another protein, Bromodomain Protein 1 (PfBDP1), which was previously shown to be involved in the invasion of red blood cells.

The two proteins may work together to regulate gene transcription during this critical stage of infection.

For more on this potential new target, see their study published in Cell Host & Microbe.

Parasite diversity

Not all malaria infections result in life-threatening anemia and organ failure, and so a research team led by Matthew B. B. McCall, MD, PhD, of Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, set out to determine why.

They exposed 23 healthy human volunteers to sets of 5 mosquitoes carrying the NF54, NF135.C10, or NF166.C8 isolates of P falciparum.

All volunteers developed parasitemia, were treated with anti-malarial drugs, and recovered, although some strains caused more severe symptoms.

The investigators found that 3 geographic and genetically diverse forms of the parasite each demonstrated a distinct ability to infect liver cells.

They also observed the degree of infection in human liver cells growing in culture was closely correlated with parasite loads in the bloodstream.

The investigators believe the variability among parasite types suggests that malaria vaccines should use multiple strains.

In addition, the infectivity of different parasite strains could vary in populations previously exposed to malaria.

For more details on parasite diversity, see the team’s findings in Science Translational Medicine.

Malaria test

A new malaria test can diagnose malaria faster and more reliably than current methods, according to a report in the NL Times.

The new test uses an algorithm that can diagnose malaria at a rate of 120 blood tests per hour. It is 97% accurate.

Rather than search for the parasite itself in blood samples, the new test analyzes the effect the infection has on the blood, such as shape and density of red blood cells, hemoglobin level, and 27 other parameters simultaneously.

The developers won the European Inventor Award for the rapid malaria test, which will be further developed by Siemens.

Aid to combat malaria

The US malaria initiative in 19 sub-Saharan African countries has contributed to a 16% reduction in the annual risk of mortality for children under 5 years, according to a new study published in PLOS Medicine.

Thirteen sub-Saharan countries did not receive funding from the initiative, which allowed researchers to compare and analyze the impact of the intervention.

Because the study may have had confounding variables that were not measured, however, the results could not be definitively interpreted as causal evidence of the reduction in child mortality rates.

However, they do indicate an association between the receipt of funding and mortality.

The funding went to support malaria prevention technologies, such as insecticide-treated nets and indoor residual spraying.

The authors believe further investment in these interventions “may translate to additional lives saved, reduced household financial burdens associated with caring for ill household members and lost wages, and less strain on health systems associated with treating malaria cases.”

Countries that received funding included: Angola, Benin, Congo DRC, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe.

Comparison countries include: Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Chad, Congo, Cote d’Ivoire, Gabon, Namibia, Niger, Sierra Leone, Swaziland, The Gambia, and Togo. ![]()

Kids’ self-reports of symptoms, side effects reliable

A small study of 20 children aged 8 to 18 years with incurable or refractory cancers indicates children are reliable reporters of their symptoms and side effects.

The investigators collected reports from the children, who were enrolled on phase 1/2 clinical trials at 4 cancer centers and undergoing their first courses of chemotherapy.

The team assessed the feasibility and acceptability of collecting symptom, function, and quality of life (QOL) reports from the study participants.

The investigators also evaluated the measurement tool and interview questions at 2 time points.

They contend the youths’ self-reports potentially could be a new trial endpoint.

According to the investigators, only rarely do patient-reported outcomes (PROs) get incorporated into pediatric phase 1 or phase 2 trials.

And because these trials contribute to drug indications and labeling, the researchers decided to assess whether it was feasible to enroll young people and retain them in a PRO endeavor.

The researchers also assessed the reliability, validity, responsiveness, and range of the pediatric measures employed. They used the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) to capture statistically significant and clinically meaningful changes or minimally important differences (MIDs) in PROs.

Pamela S. Hinds, PhD, RN, of George Washington University in Washington, DC, reported the findings on behalf of the Children's National Health System researchers in Cancer, the journal of the American Cancer Society.

"When experimental cancer drugs are studied, researchers collect details about how these promising therapies affect children's organs, but rarely do they ask the children themselves about symptoms they feel or the side effects they experience," Dr Hinds said.

"Without this crucial information, the full impact of the experimental treatment on the pediatric patient is likely underreported and clinicians are hobbled in their ability to effectively manage side effects," she added.

The team recruited children and adolescents enrolled in phase 1 safety or phase 2 efficacy trials at Children's National, Seattle Children's Hospital, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, and Boston Children's Hospital.

Findings

Sixty percent of the participants were male and 70% were white.

Median age of the participants was 13.6 years: 7 (35%) were age 8 to 12, and 13 (65%) were 13 to 17.

Thirteen participants (65%) had solid tumors, 5 (25%) had brain tumors, and 2 (10%) had lymphoma.

A total of 29 patients were eligible to participate in the trial during 20 months of screening. Five parents and 2 patients declined to participate.

The remaining 22 patients who agreed to participate accounted for a 75.9% enrollment rate. Twenty of them (90.9%) participated at the first data time point, which was at the time of enrollment, and 77.3% participated 3 weeks later at time point 2.

The authors noted that refusals to enroll were more likely to come from parents (17.2%) than the eligible patients (8.3%).

And refusals only occurred when the self-report measures were not embedded in the clinical trial.

Of the 10 protocols represented, 7 patients were enrolled on the same protocol in which the PRO measures were embedded.

The researchers administered the 6-item short-form measures for the scales of Mobility, Pain, Fatigue, Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety, and Peer Relationships.

They asked the 4 open-ended questions—concerning QOL while receiving therapy and acceptability of the patient reporting—at time point 2.

At time point 1, 3 patients did not complete 3 PROMIS measures, for a person-missing rate of 15% and a measure-missing rate of 3.3%.

At the second time point, 2 patients did not complete 1 measure each, for a person-missing rate of 11.8% and a measure-missing rate of 2%.

All but one measure at time point 1 met the reliability criterion and all measures did so at time point 2.

The research team believes their findings support the feasibility and acceptability of completing quantitative and qualitative measures regarding symptom, function, and QOL experiences among children and adolescents with incurable cancer.

The researchers note the small study size and the number of parent refusals are limitations of the trial.

Nevertheless, they recommend embedding PROs in future pediatric oncology phase 1/2 trials. ![]()

A small study of 20 children aged 8 to 18 years with incurable or refractory cancers indicates children are reliable reporters of their symptoms and side effects.

The investigators collected reports from the children, who were enrolled on phase 1/2 clinical trials at 4 cancer centers and undergoing their first courses of chemotherapy.

The team assessed the feasibility and acceptability of collecting symptom, function, and quality of life (QOL) reports from the study participants.

The investigators also evaluated the measurement tool and interview questions at 2 time points.

They contend the youths’ self-reports potentially could be a new trial endpoint.

According to the investigators, only rarely do patient-reported outcomes (PROs) get incorporated into pediatric phase 1 or phase 2 trials.

And because these trials contribute to drug indications and labeling, the researchers decided to assess whether it was feasible to enroll young people and retain them in a PRO endeavor.

The researchers also assessed the reliability, validity, responsiveness, and range of the pediatric measures employed. They used the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) to capture statistically significant and clinically meaningful changes or minimally important differences (MIDs) in PROs.

Pamela S. Hinds, PhD, RN, of George Washington University in Washington, DC, reported the findings on behalf of the Children's National Health System researchers in Cancer, the journal of the American Cancer Society.

"When experimental cancer drugs are studied, researchers collect details about how these promising therapies affect children's organs, but rarely do they ask the children themselves about symptoms they feel or the side effects they experience," Dr Hinds said.

"Without this crucial information, the full impact of the experimental treatment on the pediatric patient is likely underreported and clinicians are hobbled in their ability to effectively manage side effects," she added.

The team recruited children and adolescents enrolled in phase 1 safety or phase 2 efficacy trials at Children's National, Seattle Children's Hospital, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, and Boston Children's Hospital.

Findings

Sixty percent of the participants were male and 70% were white.

Median age of the participants was 13.6 years: 7 (35%) were age 8 to 12, and 13 (65%) were 13 to 17.

Thirteen participants (65%) had solid tumors, 5 (25%) had brain tumors, and 2 (10%) had lymphoma.

A total of 29 patients were eligible to participate in the trial during 20 months of screening. Five parents and 2 patients declined to participate.

The remaining 22 patients who agreed to participate accounted for a 75.9% enrollment rate. Twenty of them (90.9%) participated at the first data time point, which was at the time of enrollment, and 77.3% participated 3 weeks later at time point 2.

The authors noted that refusals to enroll were more likely to come from parents (17.2%) than the eligible patients (8.3%).

And refusals only occurred when the self-report measures were not embedded in the clinical trial.

Of the 10 protocols represented, 7 patients were enrolled on the same protocol in which the PRO measures were embedded.

The researchers administered the 6-item short-form measures for the scales of Mobility, Pain, Fatigue, Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety, and Peer Relationships.

They asked the 4 open-ended questions—concerning QOL while receiving therapy and acceptability of the patient reporting—at time point 2.

At time point 1, 3 patients did not complete 3 PROMIS measures, for a person-missing rate of 15% and a measure-missing rate of 3.3%.

At the second time point, 2 patients did not complete 1 measure each, for a person-missing rate of 11.8% and a measure-missing rate of 2%.

All but one measure at time point 1 met the reliability criterion and all measures did so at time point 2.

The research team believes their findings support the feasibility and acceptability of completing quantitative and qualitative measures regarding symptom, function, and QOL experiences among children and adolescents with incurable cancer.

The researchers note the small study size and the number of parent refusals are limitations of the trial.

Nevertheless, they recommend embedding PROs in future pediatric oncology phase 1/2 trials. ![]()

A small study of 20 children aged 8 to 18 years with incurable or refractory cancers indicates children are reliable reporters of their symptoms and side effects.

The investigators collected reports from the children, who were enrolled on phase 1/2 clinical trials at 4 cancer centers and undergoing their first courses of chemotherapy.

The team assessed the feasibility and acceptability of collecting symptom, function, and quality of life (QOL) reports from the study participants.

The investigators also evaluated the measurement tool and interview questions at 2 time points.

They contend the youths’ self-reports potentially could be a new trial endpoint.

According to the investigators, only rarely do patient-reported outcomes (PROs) get incorporated into pediatric phase 1 or phase 2 trials.

And because these trials contribute to drug indications and labeling, the researchers decided to assess whether it was feasible to enroll young people and retain them in a PRO endeavor.

The researchers also assessed the reliability, validity, responsiveness, and range of the pediatric measures employed. They used the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) to capture statistically significant and clinically meaningful changes or minimally important differences (MIDs) in PROs.

Pamela S. Hinds, PhD, RN, of George Washington University in Washington, DC, reported the findings on behalf of the Children's National Health System researchers in Cancer, the journal of the American Cancer Society.

"When experimental cancer drugs are studied, researchers collect details about how these promising therapies affect children's organs, but rarely do they ask the children themselves about symptoms they feel or the side effects they experience," Dr Hinds said.

"Without this crucial information, the full impact of the experimental treatment on the pediatric patient is likely underreported and clinicians are hobbled in their ability to effectively manage side effects," she added.

The team recruited children and adolescents enrolled in phase 1 safety or phase 2 efficacy trials at Children's National, Seattle Children's Hospital, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, and Boston Children's Hospital.

Findings

Sixty percent of the participants were male and 70% were white.

Median age of the participants was 13.6 years: 7 (35%) were age 8 to 12, and 13 (65%) were 13 to 17.

Thirteen participants (65%) had solid tumors, 5 (25%) had brain tumors, and 2 (10%) had lymphoma.

A total of 29 patients were eligible to participate in the trial during 20 months of screening. Five parents and 2 patients declined to participate.

The remaining 22 patients who agreed to participate accounted for a 75.9% enrollment rate. Twenty of them (90.9%) participated at the first data time point, which was at the time of enrollment, and 77.3% participated 3 weeks later at time point 2.

The authors noted that refusals to enroll were more likely to come from parents (17.2%) than the eligible patients (8.3%).

And refusals only occurred when the self-report measures were not embedded in the clinical trial.

Of the 10 protocols represented, 7 patients were enrolled on the same protocol in which the PRO measures were embedded.

The researchers administered the 6-item short-form measures for the scales of Mobility, Pain, Fatigue, Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety, and Peer Relationships.

They asked the 4 open-ended questions—concerning QOL while receiving therapy and acceptability of the patient reporting—at time point 2.

At time point 1, 3 patients did not complete 3 PROMIS measures, for a person-missing rate of 15% and a measure-missing rate of 3.3%.

At the second time point, 2 patients did not complete 1 measure each, for a person-missing rate of 11.8% and a measure-missing rate of 2%.

All but one measure at time point 1 met the reliability criterion and all measures did so at time point 2.

The research team believes their findings support the feasibility and acceptability of completing quantitative and qualitative measures regarding symptom, function, and QOL experiences among children and adolescents with incurable cancer.

The researchers note the small study size and the number of parent refusals are limitations of the trial.

Nevertheless, they recommend embedding PROs in future pediatric oncology phase 1/2 trials. ![]()

Tafenoquine reduces relapse risk in patients with P vivax malaria

A single dose of tafenoquine, when given with chloroquine, can significantly reduce the risk of relapse in patients with Plasmodium vivax malaria compared to placebo, as demonstrated by the results of 2 phase 3 studies.

Patients who have had P vivax malaria, even a single infection, can relapse several weeks or even years after the initial occurrence.

Results of the studies were presented at the 6th International Conference on Plasmodium vivax Research (ICPVR) in Manaus, Brazil.

Tafenoquine, an 8-aminoquinoline derivative, is being developed by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) in collaboration with Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV).

“One of the greatest challenges for patients with P vivax malaria,” Patrick Vallance, of GSK, said, “is preventing relapses.”

“Being able to treat patients with a single dose of medicine would be an important step forward in ensuring efficacious treatment,” Vallance noted, “thereby reducing the risk of relapse, particularly in areas with very limited healthcare infrastructure.”

The DETECTIVE and GATHER studies were conducted in malaria-endemic countries in South America, Asia, and Africa.

DETECTIVE (TAF112582) study

This was a double-blind, double-dummy phase 3 study evaluating the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of tafenoquine in 522 patients aged 16 years or older with P vivax malaria.

Patients were randomized to receive placebo, a single dose of 300 mg tafenoquine, or primaquine at 15 mg daily for 14 days in a 1:2:1 ratio.

All patients received a 3-day course of chloroquine to treat the acute blood stage infection.

The study met its primary endpoint. A statistically significant greater proportion of patients treated with tafenoquine (60%) remained relapse-free over the 6-month follow-up period than patients on placebo (26%). The odds ratio for risk of relapse vs placebo given with chloroquine was 0.24, P<0.001.

Treatment with 14 days of primaquine also achieved a statistically significant improvement in relapse-free follow-up, with an odds ratio vs placebo when given with chloroquine of 0.20, P<0.001.

The frequency of adverse events was 63% for the tafenoquine group, 59% for the primaquine group, and 65% for the chloroquine group.

And the frequency of serious adverse events was 8% for the tafenoquine group, 3% for the primaquine group, and 5% for the chloroquine group.

GATHER (TAF116564) study

This study evaluated a single dose of 300 mg tafenoquine on hemoglobin levels compared to a 14-day course of 15 mg primaquine.

Agents in the 8-aminoquinoline drug class are associated with hemolytic anemia in individuals with inherited glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency.

All patients were screened for G6PD deficiency at baseline. Males with G6PD activity of at least 70% of the site median and females with 40% were eligible.

All 251 patients also received the standard 3-day course of chloroquine.

The incidence of decline in hemoglobin was low and similar between the 2 treatment arms, 2.4% for the tafenoquine group and 1.2% for the chloroquine group.

No patient required a blood transfusion.

The companies plan to develop a point-of-care diagnostic for G6PD as a mandatory test prior to treatment with tafenoquine.

“The positive results of the phase 3 trials for single-dose tafenoquine provide great hope that a new, effective drug to stop the relapse of P vivax malaria is in sight,” David Reddy, of MMV, affirmed.

Tafenoquine currently is not approved for use anywhere in the world. GSK plans to submit regulatory filings later in 2017. ![]()

A single dose of tafenoquine, when given with chloroquine, can significantly reduce the risk of relapse in patients with Plasmodium vivax malaria compared to placebo, as demonstrated by the results of 2 phase 3 studies.

Patients who have had P vivax malaria, even a single infection, can relapse several weeks or even years after the initial occurrence.

Results of the studies were presented at the 6th International Conference on Plasmodium vivax Research (ICPVR) in Manaus, Brazil.

Tafenoquine, an 8-aminoquinoline derivative, is being developed by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) in collaboration with Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV).

“One of the greatest challenges for patients with P vivax malaria,” Patrick Vallance, of GSK, said, “is preventing relapses.”

“Being able to treat patients with a single dose of medicine would be an important step forward in ensuring efficacious treatment,” Vallance noted, “thereby reducing the risk of relapse, particularly in areas with very limited healthcare infrastructure.”

The DETECTIVE and GATHER studies were conducted in malaria-endemic countries in South America, Asia, and Africa.

DETECTIVE (TAF112582) study

This was a double-blind, double-dummy phase 3 study evaluating the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of tafenoquine in 522 patients aged 16 years or older with P vivax malaria.

Patients were randomized to receive placebo, a single dose of 300 mg tafenoquine, or primaquine at 15 mg daily for 14 days in a 1:2:1 ratio.

All patients received a 3-day course of chloroquine to treat the acute blood stage infection.

The study met its primary endpoint. A statistically significant greater proportion of patients treated with tafenoquine (60%) remained relapse-free over the 6-month follow-up period than patients on placebo (26%). The odds ratio for risk of relapse vs placebo given with chloroquine was 0.24, P<0.001.

Treatment with 14 days of primaquine also achieved a statistically significant improvement in relapse-free follow-up, with an odds ratio vs placebo when given with chloroquine of 0.20, P<0.001.

The frequency of adverse events was 63% for the tafenoquine group, 59% for the primaquine group, and 65% for the chloroquine group.

And the frequency of serious adverse events was 8% for the tafenoquine group, 3% for the primaquine group, and 5% for the chloroquine group.

GATHER (TAF116564) study

This study evaluated a single dose of 300 mg tafenoquine on hemoglobin levels compared to a 14-day course of 15 mg primaquine.

Agents in the 8-aminoquinoline drug class are associated with hemolytic anemia in individuals with inherited glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency.

All patients were screened for G6PD deficiency at baseline. Males with G6PD activity of at least 70% of the site median and females with 40% were eligible.

All 251 patients also received the standard 3-day course of chloroquine.