User login

Zika virus spread undetected in the Americas, team says

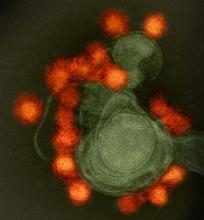

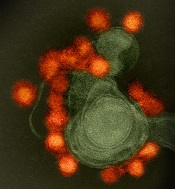

New research suggests the Zika virus spread quickly in the Americas and then diverged into distinct genetic groups.

Researchers performed genetic analysis on samples collected as the virus spread throughout the Americas after its introduction in 2013 or 2014.

The team found that Zika circulated undetected for up to a year in some regions before it came to the attention of public health authorities.

Genetic sequencing also enabled the researchers to recreate the epidemiological and evolutionary paths the virus took as it spread and split into the distinct subtypes—or clades—that have been detected in the Americas.

Hayden C. Metsky, a PhD student at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and his colleagues reported these findings in Nature.

The researchers reconstructed Zika’s dispersal by sequencing genetic material collected from hundreds of patients in 10 countries and territories.

The team eventually amassed a database of 110 complete or partial Zika virus genomes—the largest collection to date—which they analyzed along with 64 published and publicly shared genomes.

Based on changes to the viral genome that accumulated as the disease moved through new populations, the researchers concluded that Zika virus spread rapidly upon its initial introduction in Brazil, likely sometime in 2013.

Later, at several points in early to mid-2015, the virus separated into at least 3 clades—distinct genetic groups whose members share a common ancestor—in Colombia, Honduras, and Puerto Rico, as well as a fourth type found in parts of the Caribbean and the continental US.

The researchers believe these findings could have a direct impact on public health, informing disease surveillance and the development of diagnostic tests. ![]()

New research suggests the Zika virus spread quickly in the Americas and then diverged into distinct genetic groups.

Researchers performed genetic analysis on samples collected as the virus spread throughout the Americas after its introduction in 2013 or 2014.

The team found that Zika circulated undetected for up to a year in some regions before it came to the attention of public health authorities.

Genetic sequencing also enabled the researchers to recreate the epidemiological and evolutionary paths the virus took as it spread and split into the distinct subtypes—or clades—that have been detected in the Americas.

Hayden C. Metsky, a PhD student at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and his colleagues reported these findings in Nature.

The researchers reconstructed Zika’s dispersal by sequencing genetic material collected from hundreds of patients in 10 countries and territories.

The team eventually amassed a database of 110 complete or partial Zika virus genomes—the largest collection to date—which they analyzed along with 64 published and publicly shared genomes.

Based on changes to the viral genome that accumulated as the disease moved through new populations, the researchers concluded that Zika virus spread rapidly upon its initial introduction in Brazil, likely sometime in 2013.

Later, at several points in early to mid-2015, the virus separated into at least 3 clades—distinct genetic groups whose members share a common ancestor—in Colombia, Honduras, and Puerto Rico, as well as a fourth type found in parts of the Caribbean and the continental US.

The researchers believe these findings could have a direct impact on public health, informing disease surveillance and the development of diagnostic tests. ![]()

New research suggests the Zika virus spread quickly in the Americas and then diverged into distinct genetic groups.

Researchers performed genetic analysis on samples collected as the virus spread throughout the Americas after its introduction in 2013 or 2014.

The team found that Zika circulated undetected for up to a year in some regions before it came to the attention of public health authorities.

Genetic sequencing also enabled the researchers to recreate the epidemiological and evolutionary paths the virus took as it spread and split into the distinct subtypes—or clades—that have been detected in the Americas.

Hayden C. Metsky, a PhD student at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and his colleagues reported these findings in Nature.

The researchers reconstructed Zika’s dispersal by sequencing genetic material collected from hundreds of patients in 10 countries and territories.

The team eventually amassed a database of 110 complete or partial Zika virus genomes—the largest collection to date—which they analyzed along with 64 published and publicly shared genomes.

Based on changes to the viral genome that accumulated as the disease moved through new populations, the researchers concluded that Zika virus spread rapidly upon its initial introduction in Brazil, likely sometime in 2013.

Later, at several points in early to mid-2015, the virus separated into at least 3 clades—distinct genetic groups whose members share a common ancestor—in Colombia, Honduras, and Puerto Rico, as well as a fourth type found in parts of the Caribbean and the continental US.

The researchers believe these findings could have a direct impact on public health, informing disease surveillance and the development of diagnostic tests. ![]()

How Zika arrived and spread in Florida

A study published in Nature appears to explain how Zika virus entered the US via Florida in 2016 and how the virus might re-enter the country this year.

By sequencing the Zika virus genome at different points in the outbreak, researchers created a family tree showing where cases originated and how quickly they spread.

The team discovered that transmission of Zika virus began in Florida at least 4—and potentially up to 40—times last year.

The researchers also traced most of the Zika lineages back to strains of the virus in the Caribbean.

“Without these genomes, we wouldn’t be able to reconstruct the history of how the virus moved around,” said study author Kristian G. Andersen, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California.

“Rapid viral genome sequencing during ongoing outbreaks is a new development that has only been made possible over the last couple of years.”

Why Miami?

By sequencing Zika virus genomes from humans and mosquitoes—and analyzing travel and mosquito abundance data—the researchers found that several factors created a “perfect storm” for the spread of Zika virus in Miami.

“This study shows why Miami is special,” said study author Nathan D. Grubaugh, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute.

First, Dr Grubaugh explained, Miami is home to year-round populations of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, the main species that transmits Zika virus.

The area is also a significant travel hub, bringing in more international air and sea traffic than any other city in the continental US in 2016. Finally, Miami is an especially popular destination for travelers who have visited Zika-afflicted areas.

The researchers found that travel from the Caribbean islands may have significantly contributed to cases of Zika reaching Miami.

Of the 5.7 million international travelers entering Miami by flights and cruise ships between January and June of 2016, more than half arrived from the Caribbean.

Killing mosquitos produces results

The researchers believe Zika virus may have started transmission in Miami up to 40 times, but most travel-related cases did not lead to any secondary infections locally. The virus was more likely to reach a dead end than keep spreading.

The researchers found that one reason for the dead-ends was a direct connection between mosquito control efforts and disease prevention.

“We show that if you decrease the mosquito population in an area, the number of Zika infections goes down proportionally,” Dr Andersen said. “This means we can significantly limit the risk of Zika virus by focusing on mosquito control. This is not too surprising, but it’s important to show that there is an almost perfect correlation between the number of mosquitos and the number of human infections.”

Based on data from the outbreak, the researchers see potential in stopping the virus through mosquito control efforts in the US and other infected countries, instead of, for example, through travel restrictions.

“Given how many times the introductions happened, trying to restrict traffic or movement of people obviously isn’t a solution,” Dr Andersen said. “Focusing on disease prevention and mosquito control in endemic areas is likely to be a much more successful strategy.”

When the virus did spread, the researchers found that splitting Miami into designated Zika zones—often done by neighborhood or city block—didn’t accurately represent how the virus was moving.

Within each Zika zone, the researchers discovered a mixing of multiple Zika lineages, suggesting the virus wasn’t well-confined, likely moving around with infected people.

Drs Andersen and Grubaugh hope these lessons from the 2016 epidemic will help researchers and health officials respond even faster to prevent Zika’s spread in 2017.

Behind the data

Understanding Zika’s timeline required an international team of researchers and partnerships with several health agencies.

The researchers also designed a new method of genomic sequencing just to study the Zika virus. Because Zika is hard to collect in the blood of those infected, it was a challenge for the researchers to isolate enough of its genetic material for sequencing.

To solve this problem, the researchers developed 2 different protocols to break apart the genetic material they could find and reassemble it in a useful way for analysis.

With these new protocols, the researchers sequenced the virus from 28 of the reported 256 Zika cases in Florida, as well as 7 mosquito pools, to model what happened in the larger patient group.

As they worked, the researchers released their data immediately publicly to help other researchers. They hope to release more data—and analysis—in real time as cases mount in 2017.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, The Pew Charitable Trusts, The Ray Thomas Foundation, a Mahan Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Computational Biology Program at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the European Union Seventh Framework Programme, the United States Agency for International Development Emerging Pandemic Threats Program-2 PREDICT-2, and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. ![]()

A study published in Nature appears to explain how Zika virus entered the US via Florida in 2016 and how the virus might re-enter the country this year.

By sequencing the Zika virus genome at different points in the outbreak, researchers created a family tree showing where cases originated and how quickly they spread.

The team discovered that transmission of Zika virus began in Florida at least 4—and potentially up to 40—times last year.

The researchers also traced most of the Zika lineages back to strains of the virus in the Caribbean.

“Without these genomes, we wouldn’t be able to reconstruct the history of how the virus moved around,” said study author Kristian G. Andersen, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California.

“Rapid viral genome sequencing during ongoing outbreaks is a new development that has only been made possible over the last couple of years.”

Why Miami?

By sequencing Zika virus genomes from humans and mosquitoes—and analyzing travel and mosquito abundance data—the researchers found that several factors created a “perfect storm” for the spread of Zika virus in Miami.

“This study shows why Miami is special,” said study author Nathan D. Grubaugh, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute.

First, Dr Grubaugh explained, Miami is home to year-round populations of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, the main species that transmits Zika virus.

The area is also a significant travel hub, bringing in more international air and sea traffic than any other city in the continental US in 2016. Finally, Miami is an especially popular destination for travelers who have visited Zika-afflicted areas.

The researchers found that travel from the Caribbean islands may have significantly contributed to cases of Zika reaching Miami.

Of the 5.7 million international travelers entering Miami by flights and cruise ships between January and June of 2016, more than half arrived from the Caribbean.

Killing mosquitos produces results

The researchers believe Zika virus may have started transmission in Miami up to 40 times, but most travel-related cases did not lead to any secondary infections locally. The virus was more likely to reach a dead end than keep spreading.

The researchers found that one reason for the dead-ends was a direct connection between mosquito control efforts and disease prevention.

“We show that if you decrease the mosquito population in an area, the number of Zika infections goes down proportionally,” Dr Andersen said. “This means we can significantly limit the risk of Zika virus by focusing on mosquito control. This is not too surprising, but it’s important to show that there is an almost perfect correlation between the number of mosquitos and the number of human infections.”

Based on data from the outbreak, the researchers see potential in stopping the virus through mosquito control efforts in the US and other infected countries, instead of, for example, through travel restrictions.

“Given how many times the introductions happened, trying to restrict traffic or movement of people obviously isn’t a solution,” Dr Andersen said. “Focusing on disease prevention and mosquito control in endemic areas is likely to be a much more successful strategy.”

When the virus did spread, the researchers found that splitting Miami into designated Zika zones—often done by neighborhood or city block—didn’t accurately represent how the virus was moving.

Within each Zika zone, the researchers discovered a mixing of multiple Zika lineages, suggesting the virus wasn’t well-confined, likely moving around with infected people.

Drs Andersen and Grubaugh hope these lessons from the 2016 epidemic will help researchers and health officials respond even faster to prevent Zika’s spread in 2017.

Behind the data

Understanding Zika’s timeline required an international team of researchers and partnerships with several health agencies.

The researchers also designed a new method of genomic sequencing just to study the Zika virus. Because Zika is hard to collect in the blood of those infected, it was a challenge for the researchers to isolate enough of its genetic material for sequencing.

To solve this problem, the researchers developed 2 different protocols to break apart the genetic material they could find and reassemble it in a useful way for analysis.

With these new protocols, the researchers sequenced the virus from 28 of the reported 256 Zika cases in Florida, as well as 7 mosquito pools, to model what happened in the larger patient group.

As they worked, the researchers released their data immediately publicly to help other researchers. They hope to release more data—and analysis—in real time as cases mount in 2017.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, The Pew Charitable Trusts, The Ray Thomas Foundation, a Mahan Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Computational Biology Program at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the European Union Seventh Framework Programme, the United States Agency for International Development Emerging Pandemic Threats Program-2 PREDICT-2, and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. ![]()

A study published in Nature appears to explain how Zika virus entered the US via Florida in 2016 and how the virus might re-enter the country this year.

By sequencing the Zika virus genome at different points in the outbreak, researchers created a family tree showing where cases originated and how quickly they spread.

The team discovered that transmission of Zika virus began in Florida at least 4—and potentially up to 40—times last year.

The researchers also traced most of the Zika lineages back to strains of the virus in the Caribbean.

“Without these genomes, we wouldn’t be able to reconstruct the history of how the virus moved around,” said study author Kristian G. Andersen, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California.

“Rapid viral genome sequencing during ongoing outbreaks is a new development that has only been made possible over the last couple of years.”

Why Miami?

By sequencing Zika virus genomes from humans and mosquitoes—and analyzing travel and mosquito abundance data—the researchers found that several factors created a “perfect storm” for the spread of Zika virus in Miami.

“This study shows why Miami is special,” said study author Nathan D. Grubaugh, PhD, of The Scripps Research Institute.

First, Dr Grubaugh explained, Miami is home to year-round populations of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, the main species that transmits Zika virus.

The area is also a significant travel hub, bringing in more international air and sea traffic than any other city in the continental US in 2016. Finally, Miami is an especially popular destination for travelers who have visited Zika-afflicted areas.

The researchers found that travel from the Caribbean islands may have significantly contributed to cases of Zika reaching Miami.

Of the 5.7 million international travelers entering Miami by flights and cruise ships between January and June of 2016, more than half arrived from the Caribbean.

Killing mosquitos produces results

The researchers believe Zika virus may have started transmission in Miami up to 40 times, but most travel-related cases did not lead to any secondary infections locally. The virus was more likely to reach a dead end than keep spreading.

The researchers found that one reason for the dead-ends was a direct connection between mosquito control efforts and disease prevention.

“We show that if you decrease the mosquito population in an area, the number of Zika infections goes down proportionally,” Dr Andersen said. “This means we can significantly limit the risk of Zika virus by focusing on mosquito control. This is not too surprising, but it’s important to show that there is an almost perfect correlation between the number of mosquitos and the number of human infections.”

Based on data from the outbreak, the researchers see potential in stopping the virus through mosquito control efforts in the US and other infected countries, instead of, for example, through travel restrictions.

“Given how many times the introductions happened, trying to restrict traffic or movement of people obviously isn’t a solution,” Dr Andersen said. “Focusing on disease prevention and mosquito control in endemic areas is likely to be a much more successful strategy.”

When the virus did spread, the researchers found that splitting Miami into designated Zika zones—often done by neighborhood or city block—didn’t accurately represent how the virus was moving.

Within each Zika zone, the researchers discovered a mixing of multiple Zika lineages, suggesting the virus wasn’t well-confined, likely moving around with infected people.

Drs Andersen and Grubaugh hope these lessons from the 2016 epidemic will help researchers and health officials respond even faster to prevent Zika’s spread in 2017.

Behind the data

Understanding Zika’s timeline required an international team of researchers and partnerships with several health agencies.

The researchers also designed a new method of genomic sequencing just to study the Zika virus. Because Zika is hard to collect in the blood of those infected, it was a challenge for the researchers to isolate enough of its genetic material for sequencing.

To solve this problem, the researchers developed 2 different protocols to break apart the genetic material they could find and reassemble it in a useful way for analysis.

With these new protocols, the researchers sequenced the virus from 28 of the reported 256 Zika cases in Florida, as well as 7 mosquito pools, to model what happened in the larger patient group.

As they worked, the researchers released their data immediately publicly to help other researchers. They hope to release more data—and analysis—in real time as cases mount in 2017.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, The Pew Charitable Trusts, The Ray Thomas Foundation, a Mahan Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Computational Biology Program at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the European Union Seventh Framework Programme, the United States Agency for International Development Emerging Pandemic Threats Program-2 PREDICT-2, and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. ![]()

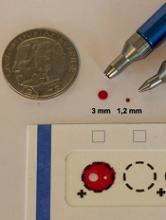

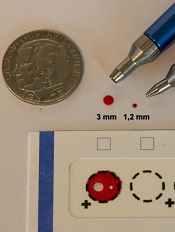

Study supports wider use of dried blood samples

Researchers have found evidence to suggest that dried blood samples may sometimes be a suitable alternative to conventional blood sampling.

The team measured levels of 92 proteins in millimeter-sized circles punched out of dried blood samples.

They found that, in many cases, little happens to these proteins when they are allowed to dry.

Most of the proteins remain unaltered after 30 years, or they change only minimally.

However, the proteins can be affected by storage temperatures.

Still, the researchers believe these results suggest dried blood samples could be used more widely—for routine health checks and to set up large-scale biobanks, with patients collecting the blood samples themselves.

“[Y]ou can prick your own finger and send in a dried blood spot by post,” study author Ulf Landegren, MD, PhD, of Uppsala University in Sweden.

“[A]t a minimal cost, it will be possible to build gigantic biobanks of samples obtained on a routine clinical basis. This means that samples can be taken before the clinical debut of a disease to identify markers of value for early diagnosis, improving the scope for curative treatment.”

Dr Landegren and his colleagues discussed these possibilities in a paper published in Molecular and Cellular Proteomics.

The researchers analyzed dried blood samples, measuring levels of 92 proteins that are relevant in oncology. To determine the effects of long-term storage, the team examined what happens to protein detection as an effect of the drying process.

Some of the dried blood samples analyzed had been collected recently, while others had been preserved for up to 30 years in biobanks in Sweden and Denmark. These 2 biobanks keep their dried blood samples at different temperatures: the Swedish one at +4°C and the Danish one at -24°C.

The researchers also looked at wet plasma samples kept at -70°C for corresponding periods of time.

“Our conclusion is that we can measure levels of 92 proteins with very high precision and sensitivity using PEA [proximity extension assay] technology in the tiny, punched-out discs from a dried blood spot,” said study author Johan Björkesten, a doctoral student at Uppsala University.

“The actual drying process has a negligible effect on the various proteins, and the effect is reproducible, which means that it can be included in the calculation.”

The researchers did find that long-term storage affects the detectability of certain proteins more than others.

Most proteins remain completely intact after 30 years or exhibit minimal changes. However, levels of some proteins decrease so that half the quantity remains after a period of between 10 and 50 years.

The researchers also found that a relatively low storage temperature is preferable for proteins that are affected by storage.

Protein detection was less affected when dried blood samples were stored at -24°C than when they were stored at +4°C. Over the 30-year period, detectability was not affected for 34% of proteins stored at +4°C and 76% of proteins stored at -24°C.

However, storing wet plasma at -70°C preserved proteins better than dried blood sample storage at -24°C. Detectability decreased for 5% of the proteins stored wet at -70°C for 45 years, compared to 24% for proteins in dried samples stored at -24°C for 30 years.

The researchers did note, though, that this part of their analysis was complicated by some confounding factors, so this was not a clear, direct comparison between wet and dry samples. ![]()

Researchers have found evidence to suggest that dried blood samples may sometimes be a suitable alternative to conventional blood sampling.

The team measured levels of 92 proteins in millimeter-sized circles punched out of dried blood samples.

They found that, in many cases, little happens to these proteins when they are allowed to dry.

Most of the proteins remain unaltered after 30 years, or they change only minimally.

However, the proteins can be affected by storage temperatures.

Still, the researchers believe these results suggest dried blood samples could be used more widely—for routine health checks and to set up large-scale biobanks, with patients collecting the blood samples themselves.

“[Y]ou can prick your own finger and send in a dried blood spot by post,” study author Ulf Landegren, MD, PhD, of Uppsala University in Sweden.

“[A]t a minimal cost, it will be possible to build gigantic biobanks of samples obtained on a routine clinical basis. This means that samples can be taken before the clinical debut of a disease to identify markers of value for early diagnosis, improving the scope for curative treatment.”

Dr Landegren and his colleagues discussed these possibilities in a paper published in Molecular and Cellular Proteomics.

The researchers analyzed dried blood samples, measuring levels of 92 proteins that are relevant in oncology. To determine the effects of long-term storage, the team examined what happens to protein detection as an effect of the drying process.

Some of the dried blood samples analyzed had been collected recently, while others had been preserved for up to 30 years in biobanks in Sweden and Denmark. These 2 biobanks keep their dried blood samples at different temperatures: the Swedish one at +4°C and the Danish one at -24°C.

The researchers also looked at wet plasma samples kept at -70°C for corresponding periods of time.

“Our conclusion is that we can measure levels of 92 proteins with very high precision and sensitivity using PEA [proximity extension assay] technology in the tiny, punched-out discs from a dried blood spot,” said study author Johan Björkesten, a doctoral student at Uppsala University.

“The actual drying process has a negligible effect on the various proteins, and the effect is reproducible, which means that it can be included in the calculation.”

The researchers did find that long-term storage affects the detectability of certain proteins more than others.

Most proteins remain completely intact after 30 years or exhibit minimal changes. However, levels of some proteins decrease so that half the quantity remains after a period of between 10 and 50 years.

The researchers also found that a relatively low storage temperature is preferable for proteins that are affected by storage.

Protein detection was less affected when dried blood samples were stored at -24°C than when they were stored at +4°C. Over the 30-year period, detectability was not affected for 34% of proteins stored at +4°C and 76% of proteins stored at -24°C.

However, storing wet plasma at -70°C preserved proteins better than dried blood sample storage at -24°C. Detectability decreased for 5% of the proteins stored wet at -70°C for 45 years, compared to 24% for proteins in dried samples stored at -24°C for 30 years.

The researchers did note, though, that this part of their analysis was complicated by some confounding factors, so this was not a clear, direct comparison between wet and dry samples. ![]()

Researchers have found evidence to suggest that dried blood samples may sometimes be a suitable alternative to conventional blood sampling.

The team measured levels of 92 proteins in millimeter-sized circles punched out of dried blood samples.

They found that, in many cases, little happens to these proteins when they are allowed to dry.

Most of the proteins remain unaltered after 30 years, or they change only minimally.

However, the proteins can be affected by storage temperatures.

Still, the researchers believe these results suggest dried blood samples could be used more widely—for routine health checks and to set up large-scale biobanks, with patients collecting the blood samples themselves.

“[Y]ou can prick your own finger and send in a dried blood spot by post,” study author Ulf Landegren, MD, PhD, of Uppsala University in Sweden.

“[A]t a minimal cost, it will be possible to build gigantic biobanks of samples obtained on a routine clinical basis. This means that samples can be taken before the clinical debut of a disease to identify markers of value for early diagnosis, improving the scope for curative treatment.”

Dr Landegren and his colleagues discussed these possibilities in a paper published in Molecular and Cellular Proteomics.

The researchers analyzed dried blood samples, measuring levels of 92 proteins that are relevant in oncology. To determine the effects of long-term storage, the team examined what happens to protein detection as an effect of the drying process.

Some of the dried blood samples analyzed had been collected recently, while others had been preserved for up to 30 years in biobanks in Sweden and Denmark. These 2 biobanks keep their dried blood samples at different temperatures: the Swedish one at +4°C and the Danish one at -24°C.

The researchers also looked at wet plasma samples kept at -70°C for corresponding periods of time.

“Our conclusion is that we can measure levels of 92 proteins with very high precision and sensitivity using PEA [proximity extension assay] technology in the tiny, punched-out discs from a dried blood spot,” said study author Johan Björkesten, a doctoral student at Uppsala University.

“The actual drying process has a negligible effect on the various proteins, and the effect is reproducible, which means that it can be included in the calculation.”

The researchers did find that long-term storage affects the detectability of certain proteins more than others.

Most proteins remain completely intact after 30 years or exhibit minimal changes. However, levels of some proteins decrease so that half the quantity remains after a period of between 10 and 50 years.

The researchers also found that a relatively low storage temperature is preferable for proteins that are affected by storage.

Protein detection was less affected when dried blood samples were stored at -24°C than when they were stored at +4°C. Over the 30-year period, detectability was not affected for 34% of proteins stored at +4°C and 76% of proteins stored at -24°C.

However, storing wet plasma at -70°C preserved proteins better than dried blood sample storage at -24°C. Detectability decreased for 5% of the proteins stored wet at -70°C for 45 years, compared to 24% for proteins in dried samples stored at -24°C for 30 years.

The researchers did note, though, that this part of their analysis was complicated by some confounding factors, so this was not a clear, direct comparison between wet and dry samples. ![]()

Global study reveals healthcare inequity, preventable deaths

A global study has revealed inequity of access to and quality of healthcare among and within countries and suggests people are dying from causes with well-known treatments.

“What we have found about healthcare access and quality is disturbing,” said Christopher Murray, MD, DPhil, of the University of Washington in Seattle.

“Having a strong economy does not guarantee good healthcare. Having great medical technology doesn’t either. We know this because people are not getting the care that should be expected for diseases with established treatments.”

Dr Murray and his colleagues reported these findings in The Lancet.

For this study, the researchers assessed access to and quality of healthcare services in 195 countries from 1990 to 2015.

The group used the Healthcare Access and Quality Index, a summary measure based on 32 causes* that, in the presence of high-quality healthcare, should not result in death. Leukemia and Hodgkin lymphoma are among these causes.

Countries were assigned scores for each of the causes, based on estimates from the annual Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors study (GBD), a systematic, scientific effort to quantify the magnitude of health loss from all major diseases, injuries, and risk factors by age, sex, and population.

In addition, data were extracted from the most recent GBD update and evaluated using a Socio-demographic Index based on rates of education, fertility, and income.

Results

The 195 countries were assigned scores on a scale of 1 to 100 for healthcare access and quality. They received scores for the 32 causes as well as overall scores.

In 2015, the top-ranked nation was Andorra, with an overall score of 95. Its lowest treatment score was 70, for Hodgkin lymphoma.

The lowest-ranked nation was Central African Republic, with a score of 29. Its highest treatment score was 65, for diphtheria.

Nations in much of sub-Saharan Africa, as well as in south Asia and several countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, also had low rankings.

However, many countries in these regions, including China (score: 74) and Ethiopia (score: 44), have seen sizeable gains since 1990.

‘Developed’ nations falling short

The US had an overall score of 81 (in 2015), tied with Estonia and Montenegro. As with many other nations, the US scored 100 in treating common vaccine-preventable diseases, such as diphtheria, tetanus, and measles.

However, the US had 9 treatment categories in which it scored in the 60s: lower respiratory infections (60), neonatal disorders (69), non-melanoma skin cancer (68), Hodgkin lymphoma (67), ischemic heart disease (62), hypertensive heart disease (64), diabetes (67), chronic kidney disease (62), and the adverse effects of medical treatment itself (68).

“America’s ranking is an embarrassment, especially considering the US spends more than $9000 per person on healthcare annually, more than any other country,” Dr Murray said.

“Anyone with a stake in the current healthcare debate, including elected officials at the federal, state, and local levels, should take a look at where the US is falling short.”

Other nations with strong economies and advanced medical technology are falling short in some areas as well.

For example, Norway and Australia each scored 90 overall, among the highest in the world. However, Norway scored 65 in its treatment for testicular cancer, and Australia scored 52 for treating non-melanoma skin cancer.

“In the majority of cases, both of these cancers can be treated effectively,” Dr Murray said. “Shouldn’t it cause serious concern that people are dying of these causes in countries that have the resources to address them?” ![]()

*The 32 causes are:

- Adverse effects of medical treatment

- Appendicitis

- Breast cancer

- Cerebrovascular disease (stroke)

- Cervical cancer

- Chronic kidney disease

- Chronic respiratory diseases

- Colon and rectum cancer

- Congenital anomalies

- Diabetes mellitus

- Diarrhea-related diseases

- Diphtheria

- Epilepsy

- Gallbladder and biliary diseases

- Hodgkin lymphoma

- Hypertensive heart disease

- Inguinal, femoral, and abdominal hernia

- Ischemic heart disease

- Leukemia

- Lower respiratory infections

- Maternal disorders

- Measles

- Neonatal disorders

- Non-melanoma skin cancer

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Rheumatic heart disease

- Testicular cancer

- Tetanus

- Tuberculosis

- Upper respiratory infections

- Uterine cancer

- Whooping cough.

A global study has revealed inequity of access to and quality of healthcare among and within countries and suggests people are dying from causes with well-known treatments.

“What we have found about healthcare access and quality is disturbing,” said Christopher Murray, MD, DPhil, of the University of Washington in Seattle.

“Having a strong economy does not guarantee good healthcare. Having great medical technology doesn’t either. We know this because people are not getting the care that should be expected for diseases with established treatments.”

Dr Murray and his colleagues reported these findings in The Lancet.

For this study, the researchers assessed access to and quality of healthcare services in 195 countries from 1990 to 2015.

The group used the Healthcare Access and Quality Index, a summary measure based on 32 causes* that, in the presence of high-quality healthcare, should not result in death. Leukemia and Hodgkin lymphoma are among these causes.

Countries were assigned scores for each of the causes, based on estimates from the annual Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors study (GBD), a systematic, scientific effort to quantify the magnitude of health loss from all major diseases, injuries, and risk factors by age, sex, and population.

In addition, data were extracted from the most recent GBD update and evaluated using a Socio-demographic Index based on rates of education, fertility, and income.

Results

The 195 countries were assigned scores on a scale of 1 to 100 for healthcare access and quality. They received scores for the 32 causes as well as overall scores.

In 2015, the top-ranked nation was Andorra, with an overall score of 95. Its lowest treatment score was 70, for Hodgkin lymphoma.

The lowest-ranked nation was Central African Republic, with a score of 29. Its highest treatment score was 65, for diphtheria.

Nations in much of sub-Saharan Africa, as well as in south Asia and several countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, also had low rankings.

However, many countries in these regions, including China (score: 74) and Ethiopia (score: 44), have seen sizeable gains since 1990.

‘Developed’ nations falling short

The US had an overall score of 81 (in 2015), tied with Estonia and Montenegro. As with many other nations, the US scored 100 in treating common vaccine-preventable diseases, such as diphtheria, tetanus, and measles.

However, the US had 9 treatment categories in which it scored in the 60s: lower respiratory infections (60), neonatal disorders (69), non-melanoma skin cancer (68), Hodgkin lymphoma (67), ischemic heart disease (62), hypertensive heart disease (64), diabetes (67), chronic kidney disease (62), and the adverse effects of medical treatment itself (68).

“America’s ranking is an embarrassment, especially considering the US spends more than $9000 per person on healthcare annually, more than any other country,” Dr Murray said.

“Anyone with a stake in the current healthcare debate, including elected officials at the federal, state, and local levels, should take a look at where the US is falling short.”

Other nations with strong economies and advanced medical technology are falling short in some areas as well.

For example, Norway and Australia each scored 90 overall, among the highest in the world. However, Norway scored 65 in its treatment for testicular cancer, and Australia scored 52 for treating non-melanoma skin cancer.

“In the majority of cases, both of these cancers can be treated effectively,” Dr Murray said. “Shouldn’t it cause serious concern that people are dying of these causes in countries that have the resources to address them?” ![]()

*The 32 causes are:

- Adverse effects of medical treatment

- Appendicitis

- Breast cancer

- Cerebrovascular disease (stroke)

- Cervical cancer

- Chronic kidney disease

- Chronic respiratory diseases

- Colon and rectum cancer

- Congenital anomalies

- Diabetes mellitus

- Diarrhea-related diseases

- Diphtheria

- Epilepsy

- Gallbladder and biliary diseases

- Hodgkin lymphoma

- Hypertensive heart disease

- Inguinal, femoral, and abdominal hernia

- Ischemic heart disease

- Leukemia

- Lower respiratory infections

- Maternal disorders

- Measles

- Neonatal disorders

- Non-melanoma skin cancer

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Rheumatic heart disease

- Testicular cancer

- Tetanus

- Tuberculosis

- Upper respiratory infections

- Uterine cancer

- Whooping cough.

A global study has revealed inequity of access to and quality of healthcare among and within countries and suggests people are dying from causes with well-known treatments.

“What we have found about healthcare access and quality is disturbing,” said Christopher Murray, MD, DPhil, of the University of Washington in Seattle.

“Having a strong economy does not guarantee good healthcare. Having great medical technology doesn’t either. We know this because people are not getting the care that should be expected for diseases with established treatments.”

Dr Murray and his colleagues reported these findings in The Lancet.

For this study, the researchers assessed access to and quality of healthcare services in 195 countries from 1990 to 2015.

The group used the Healthcare Access and Quality Index, a summary measure based on 32 causes* that, in the presence of high-quality healthcare, should not result in death. Leukemia and Hodgkin lymphoma are among these causes.

Countries were assigned scores for each of the causes, based on estimates from the annual Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors study (GBD), a systematic, scientific effort to quantify the magnitude of health loss from all major diseases, injuries, and risk factors by age, sex, and population.

In addition, data were extracted from the most recent GBD update and evaluated using a Socio-demographic Index based on rates of education, fertility, and income.

Results

The 195 countries were assigned scores on a scale of 1 to 100 for healthcare access and quality. They received scores for the 32 causes as well as overall scores.

In 2015, the top-ranked nation was Andorra, with an overall score of 95. Its lowest treatment score was 70, for Hodgkin lymphoma.

The lowest-ranked nation was Central African Republic, with a score of 29. Its highest treatment score was 65, for diphtheria.

Nations in much of sub-Saharan Africa, as well as in south Asia and several countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, also had low rankings.

However, many countries in these regions, including China (score: 74) and Ethiopia (score: 44), have seen sizeable gains since 1990.

‘Developed’ nations falling short

The US had an overall score of 81 (in 2015), tied with Estonia and Montenegro. As with many other nations, the US scored 100 in treating common vaccine-preventable diseases, such as diphtheria, tetanus, and measles.

However, the US had 9 treatment categories in which it scored in the 60s: lower respiratory infections (60), neonatal disorders (69), non-melanoma skin cancer (68), Hodgkin lymphoma (67), ischemic heart disease (62), hypertensive heart disease (64), diabetes (67), chronic kidney disease (62), and the adverse effects of medical treatment itself (68).

“America’s ranking is an embarrassment, especially considering the US spends more than $9000 per person on healthcare annually, more than any other country,” Dr Murray said.

“Anyone with a stake in the current healthcare debate, including elected officials at the federal, state, and local levels, should take a look at where the US is falling short.”

Other nations with strong economies and advanced medical technology are falling short in some areas as well.

For example, Norway and Australia each scored 90 overall, among the highest in the world. However, Norway scored 65 in its treatment for testicular cancer, and Australia scored 52 for treating non-melanoma skin cancer.

“In the majority of cases, both of these cancers can be treated effectively,” Dr Murray said. “Shouldn’t it cause serious concern that people are dying of these causes in countries that have the resources to address them?” ![]()

*The 32 causes are:

- Adverse effects of medical treatment

- Appendicitis

- Breast cancer

- Cerebrovascular disease (stroke)

- Cervical cancer

- Chronic kidney disease

- Chronic respiratory diseases

- Colon and rectum cancer

- Congenital anomalies

- Diabetes mellitus

- Diarrhea-related diseases

- Diphtheria

- Epilepsy

- Gallbladder and biliary diseases

- Hodgkin lymphoma

- Hypertensive heart disease

- Inguinal, femoral, and abdominal hernia

- Ischemic heart disease

- Leukemia

- Lower respiratory infections

- Maternal disorders

- Measles

- Neonatal disorders

- Non-melanoma skin cancer

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Rheumatic heart disease

- Testicular cancer

- Tetanus

- Tuberculosis

- Upper respiratory infections

- Uterine cancer

- Whooping cough.

FDA supports continued, cautious use of GBCAs

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) said it has not found any evidence of adverse health effects from gadolinium retention in the brain following the use of gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs) for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

The agency noted that all GBCAs may be associated with some gadolinium retention in the brain and other body tissues.

However, an FDA review showed no evidence that gadolinium retention in the brain is harmful.

Therefore, the FDA said it will not restrict GBCA use, although the agency will continue to assess the safety of GBCAs and plans to have a public meeting on the issue in the future.

The manufacturer of OptiMARK (gadoversetamide), a linear GBCA, updated its label with information about gadolinium retention. The FDA said it is reviewing the labels of other GBCAs to determine if changes are needed.

Recommendations

The FDA said its recommendations regarding GBCAs have not changed.

The agency advises healthcare professionals to limit GBCA use to circumstances in which the contrast agent can provide necessary information. Professionals should also consider the necessity of repetitive MRIs with GBCAs.

Patients, parents, and caregivers with any questions or concerns about GBCAs should discuss the agents with their healthcare professionals.

The FDA is also urging patients and healthcare professionals to report side effects involving GBCAs to the agency’s MedWatch program.

About the FDA review

For its review, the FDA looked at scientific publications and adverse event reports submitted to agency.

These data showed that gadolinium is retained in organs and suggested that linear GBCAs cause retention of more gadolinium in the brain than macrocyclic GBCAs. However, the data did not show adverse health effects related to this brain retention.

The only known adverse health effect related to gadolinium retention is nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF), a disease characterized by thickening of the skin, which can involve the joints and limit motion.

NSF is known to occur in patients with pre-existing kidney failure. However, recent publications have shown reactions involving thickening and hardening of the skin and other tissues in patients with normal kidney function who received GBCAs and did not have NSF. Some of these patients also had evidence of gadolinium retention.

The FDA said it is evaluating such reports to determine if these fibrotic reactions are an adverse health effect of retained gadolinium.

The agency is also continuing its assessment of GBCAs, investigating how gadolinium is retained in the body. And the FDA’s National Center for Toxicological Research is conducting a study on brain retention of GBCAs in rats.

PRAC review

A recent review by the European Medicines Agency’s Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) suggested there are no adverse health effects associated with gadolinium retention in the brain.

However, the PRAC recommended suspending the marketing authorization of certain linear GBCAs because they cause greater retention of gadolinium in the brain than macrocyclic GBCAs.

The PRAC’s recommendation is undergoing an appeal, which will be further reviewed by the PRAC and the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) said it has not found any evidence of adverse health effects from gadolinium retention in the brain following the use of gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs) for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

The agency noted that all GBCAs may be associated with some gadolinium retention in the brain and other body tissues.

However, an FDA review showed no evidence that gadolinium retention in the brain is harmful.

Therefore, the FDA said it will not restrict GBCA use, although the agency will continue to assess the safety of GBCAs and plans to have a public meeting on the issue in the future.

The manufacturer of OptiMARK (gadoversetamide), a linear GBCA, updated its label with information about gadolinium retention. The FDA said it is reviewing the labels of other GBCAs to determine if changes are needed.

Recommendations

The FDA said its recommendations regarding GBCAs have not changed.

The agency advises healthcare professionals to limit GBCA use to circumstances in which the contrast agent can provide necessary information. Professionals should also consider the necessity of repetitive MRIs with GBCAs.

Patients, parents, and caregivers with any questions or concerns about GBCAs should discuss the agents with their healthcare professionals.

The FDA is also urging patients and healthcare professionals to report side effects involving GBCAs to the agency’s MedWatch program.

About the FDA review

For its review, the FDA looked at scientific publications and adverse event reports submitted to agency.

These data showed that gadolinium is retained in organs and suggested that linear GBCAs cause retention of more gadolinium in the brain than macrocyclic GBCAs. However, the data did not show adverse health effects related to this brain retention.

The only known adverse health effect related to gadolinium retention is nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF), a disease characterized by thickening of the skin, which can involve the joints and limit motion.

NSF is known to occur in patients with pre-existing kidney failure. However, recent publications have shown reactions involving thickening and hardening of the skin and other tissues in patients with normal kidney function who received GBCAs and did not have NSF. Some of these patients also had evidence of gadolinium retention.

The FDA said it is evaluating such reports to determine if these fibrotic reactions are an adverse health effect of retained gadolinium.

The agency is also continuing its assessment of GBCAs, investigating how gadolinium is retained in the body. And the FDA’s National Center for Toxicological Research is conducting a study on brain retention of GBCAs in rats.

PRAC review

A recent review by the European Medicines Agency’s Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) suggested there are no adverse health effects associated with gadolinium retention in the brain.

However, the PRAC recommended suspending the marketing authorization of certain linear GBCAs because they cause greater retention of gadolinium in the brain than macrocyclic GBCAs.

The PRAC’s recommendation is undergoing an appeal, which will be further reviewed by the PRAC and the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) said it has not found any evidence of adverse health effects from gadolinium retention in the brain following the use of gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs) for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

The agency noted that all GBCAs may be associated with some gadolinium retention in the brain and other body tissues.

However, an FDA review showed no evidence that gadolinium retention in the brain is harmful.

Therefore, the FDA said it will not restrict GBCA use, although the agency will continue to assess the safety of GBCAs and plans to have a public meeting on the issue in the future.

The manufacturer of OptiMARK (gadoversetamide), a linear GBCA, updated its label with information about gadolinium retention. The FDA said it is reviewing the labels of other GBCAs to determine if changes are needed.

Recommendations

The FDA said its recommendations regarding GBCAs have not changed.

The agency advises healthcare professionals to limit GBCA use to circumstances in which the contrast agent can provide necessary information. Professionals should also consider the necessity of repetitive MRIs with GBCAs.

Patients, parents, and caregivers with any questions or concerns about GBCAs should discuss the agents with their healthcare professionals.

The FDA is also urging patients and healthcare professionals to report side effects involving GBCAs to the agency’s MedWatch program.

About the FDA review

For its review, the FDA looked at scientific publications and adverse event reports submitted to agency.

These data showed that gadolinium is retained in organs and suggested that linear GBCAs cause retention of more gadolinium in the brain than macrocyclic GBCAs. However, the data did not show adverse health effects related to this brain retention.

The only known adverse health effect related to gadolinium retention is nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF), a disease characterized by thickening of the skin, which can involve the joints and limit motion.

NSF is known to occur in patients with pre-existing kidney failure. However, recent publications have shown reactions involving thickening and hardening of the skin and other tissues in patients with normal kidney function who received GBCAs and did not have NSF. Some of these patients also had evidence of gadolinium retention.

The FDA said it is evaluating such reports to determine if these fibrotic reactions are an adverse health effect of retained gadolinium.

The agency is also continuing its assessment of GBCAs, investigating how gadolinium is retained in the body. And the FDA’s National Center for Toxicological Research is conducting a study on brain retention of GBCAs in rats.

PRAC review

A recent review by the European Medicines Agency’s Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) suggested there are no adverse health effects associated with gadolinium retention in the brain.

However, the PRAC recommended suspending the marketing authorization of certain linear GBCAs because they cause greater retention of gadolinium in the brain than macrocyclic GBCAs.

The PRAC’s recommendation is undergoing an appeal, which will be further reviewed by the PRAC and the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. ![]()

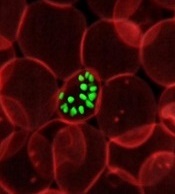

Gene variant reduces risk of severe malaria

New research indicates that some Africans carry a gene variant that reduces the risk of severe malaria.

The study suggests this variant results from the rearrangement of 2 glycophorin receptors found on the surface of red blood cells.

The malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum uses these receptors—GYPA and GYPB—to enter the cells.

Researchers identified a gene variant that results in altered GYPA and GYPB receptors and may reduce the risk of severe malaria by 40%.

Ellen Leffler, of the University of Oxford in the UK, and her colleagues reported these findings in Science.

The researchers performed genome sequencing of 765 individuals from 10 ethnic groups in Gambia, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, and Tanzania.

The team also conducted a study across the Gambia, Kenya, and Malawi that included 5310 individuals from the general population and 4579 people who were hospitalized with severe malaria.

These analyses revealed copy number variants affecting GYPA and GYPB.

“[W]e found strong evidence that variation in the glycophorin gene cluster influences malaria susceptibility,” Dr Leffler said.

“We found some people have a complex rearrangement of GYPA and GYPB genes, forming a hybrid glycophorin, and these people are less likely to develop severe complications of the disease.”

The rearrangement involves the loss of GYPB and gain of 2 GYPB-A hybrid genes. The hybrid GYPB-A gene is found in a rare blood group—part of the MNS blood group system—where it is known as Dantu.

DUP4, the most common Dantu gene variant, is a result of the rearrangement. And the researchers found that DUP4 reduced the risk of severe malaria by an estimated 40%.

DUP4 was only present in certain populations, particularly in individuals of East African descent.

The researchers proposed a number of reasons as to why DUP4 may not be more widespread, including the possibility that it emerged recently. Alternatively, it may only protect against certain strains of P falciparum that are specific to east Africa.

Though more research is needed, the team said these findings link the structural variation of glycophorin receptors with resistance to severe malaria.

“We are starting to find that the glycophorin region of the genome has an important role in protecting people against malaria,” said study author Dominic Kwiatkowski, MD, of the University of Oxford.

“Our discovery that a specific variant of glycophorin invasion receptors can give substantial protection against severe malaria will hopefully inspire further research on exactly how Plasmodium falciparum invade red blood cells. This could also help us discover novel parasite weaknesses that could be exploited in future interventions against this deadly disease.” ![]()

New research indicates that some Africans carry a gene variant that reduces the risk of severe malaria.

The study suggests this variant results from the rearrangement of 2 glycophorin receptors found on the surface of red blood cells.

The malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum uses these receptors—GYPA and GYPB—to enter the cells.

Researchers identified a gene variant that results in altered GYPA and GYPB receptors and may reduce the risk of severe malaria by 40%.

Ellen Leffler, of the University of Oxford in the UK, and her colleagues reported these findings in Science.

The researchers performed genome sequencing of 765 individuals from 10 ethnic groups in Gambia, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, and Tanzania.

The team also conducted a study across the Gambia, Kenya, and Malawi that included 5310 individuals from the general population and 4579 people who were hospitalized with severe malaria.

These analyses revealed copy number variants affecting GYPA and GYPB.

“[W]e found strong evidence that variation in the glycophorin gene cluster influences malaria susceptibility,” Dr Leffler said.

“We found some people have a complex rearrangement of GYPA and GYPB genes, forming a hybrid glycophorin, and these people are less likely to develop severe complications of the disease.”

The rearrangement involves the loss of GYPB and gain of 2 GYPB-A hybrid genes. The hybrid GYPB-A gene is found in a rare blood group—part of the MNS blood group system—where it is known as Dantu.

DUP4, the most common Dantu gene variant, is a result of the rearrangement. And the researchers found that DUP4 reduced the risk of severe malaria by an estimated 40%.

DUP4 was only present in certain populations, particularly in individuals of East African descent.

The researchers proposed a number of reasons as to why DUP4 may not be more widespread, including the possibility that it emerged recently. Alternatively, it may only protect against certain strains of P falciparum that are specific to east Africa.

Though more research is needed, the team said these findings link the structural variation of glycophorin receptors with resistance to severe malaria.

“We are starting to find that the glycophorin region of the genome has an important role in protecting people against malaria,” said study author Dominic Kwiatkowski, MD, of the University of Oxford.

“Our discovery that a specific variant of glycophorin invasion receptors can give substantial protection against severe malaria will hopefully inspire further research on exactly how Plasmodium falciparum invade red blood cells. This could also help us discover novel parasite weaknesses that could be exploited in future interventions against this deadly disease.” ![]()

New research indicates that some Africans carry a gene variant that reduces the risk of severe malaria.

The study suggests this variant results from the rearrangement of 2 glycophorin receptors found on the surface of red blood cells.

The malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum uses these receptors—GYPA and GYPB—to enter the cells.

Researchers identified a gene variant that results in altered GYPA and GYPB receptors and may reduce the risk of severe malaria by 40%.

Ellen Leffler, of the University of Oxford in the UK, and her colleagues reported these findings in Science.

The researchers performed genome sequencing of 765 individuals from 10 ethnic groups in Gambia, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, and Tanzania.

The team also conducted a study across the Gambia, Kenya, and Malawi that included 5310 individuals from the general population and 4579 people who were hospitalized with severe malaria.

These analyses revealed copy number variants affecting GYPA and GYPB.

“[W]e found strong evidence that variation in the glycophorin gene cluster influences malaria susceptibility,” Dr Leffler said.

“We found some people have a complex rearrangement of GYPA and GYPB genes, forming a hybrid glycophorin, and these people are less likely to develop severe complications of the disease.”

The rearrangement involves the loss of GYPB and gain of 2 GYPB-A hybrid genes. The hybrid GYPB-A gene is found in a rare blood group—part of the MNS blood group system—where it is known as Dantu.

DUP4, the most common Dantu gene variant, is a result of the rearrangement. And the researchers found that DUP4 reduced the risk of severe malaria by an estimated 40%.

DUP4 was only present in certain populations, particularly in individuals of East African descent.

The researchers proposed a number of reasons as to why DUP4 may not be more widespread, including the possibility that it emerged recently. Alternatively, it may only protect against certain strains of P falciparum that are specific to east Africa.

Though more research is needed, the team said these findings link the structural variation of glycophorin receptors with resistance to severe malaria.

“We are starting to find that the glycophorin region of the genome has an important role in protecting people against malaria,” said study author Dominic Kwiatkowski, MD, of the University of Oxford.

“Our discovery that a specific variant of glycophorin invasion receptors can give substantial protection against severe malaria will hopefully inspire further research on exactly how Plasmodium falciparum invade red blood cells. This could also help us discover novel parasite weaknesses that could be exploited in future interventions against this deadly disease.” ![]()

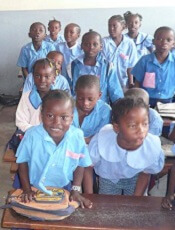

Maternal education can reduce risk of childhood malaria

One way to reduce the risk of malaria infection in children is to educate their mothers, according to a study published in Pathogens and Global Health.

The study suggested that educating mothers can be more effective in preventing childhood malaria than the malaria vaccine candidate RTS,S (Mosquirix).

Researchers said this finding can be explained by the fact that educated mothers know of ways to prevent malaria infection, such as using bed nets and taking their children for treatment if they develop a fever.

For this study, the researchers performed malaria testing in 647 children in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) who were between the ages of 2 months and 5 years.

The team also had the children’s parent or guardian fill out a survey related to demographics, socioeconomic status, maternal education, bed net use, and recent illness involving fever.

Results showed that mothers with a higher education level had children with a lower risk of malaria infection.

“This was not a small effect,” said study author Michael Hawkes, MD, PhD, of the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

“Maternal education had an enormous effect—equivalent to or greater than the leading biomedical vaccine against malaria.”

Overall, 19% of the children studied (123/647) tested positive for malaria.

The prevalence of malaria was 30% in children of mothers with no education, 17% in children of mothers with primary education, and 15% in children of mothers with education beyond primary school (P=0.001).

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for the effect of a child’s age and the study site, maternal education was still a significant predictor of malaria antigenemia.

“It doesn’t take a lot of education to teach a mom how to take simple precautions to prevent malaria in her child,” said study author Cary Ma, a medical student at the University of Alberta.

“All it takes is knowing the importance of using a bed net and knowing the importance of seeking care when your child has a fever. These are fairly straightforward, simple messages in the context of health and hygiene that can easily be conveyed, usually at an elementary or primary school level.”

“The World Health Organization is rolling out a new vaccine [RTS,S] in countries across Africa that has an efficacy of about 30%,” Dr Hawkes added.

“But children whose mothers are educated beyond the primary level have a 53% reduction in their malaria rates. So educating the mom has as profound an effect on childhood malaria as hundreds of millions of dollars spent on a vaccine.”

The researchers said this work builds upon previous studies that have shown the importance of maternal education in reducing child mortality and disease in other countries around the world.

The team noted that maternal education isn’t a magic bullet by itself, but they do believe it is part of the solution. They hope the lessons learned via this study can help lead policymakers to strengthen efforts to educate girls and women in the DRC and other malaria hotspots around the world. ![]()

One way to reduce the risk of malaria infection in children is to educate their mothers, according to a study published in Pathogens and Global Health.

The study suggested that educating mothers can be more effective in preventing childhood malaria than the malaria vaccine candidate RTS,S (Mosquirix).

Researchers said this finding can be explained by the fact that educated mothers know of ways to prevent malaria infection, such as using bed nets and taking their children for treatment if they develop a fever.

For this study, the researchers performed malaria testing in 647 children in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) who were between the ages of 2 months and 5 years.

The team also had the children’s parent or guardian fill out a survey related to demographics, socioeconomic status, maternal education, bed net use, and recent illness involving fever.

Results showed that mothers with a higher education level had children with a lower risk of malaria infection.

“This was not a small effect,” said study author Michael Hawkes, MD, PhD, of the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

“Maternal education had an enormous effect—equivalent to or greater than the leading biomedical vaccine against malaria.”

Overall, 19% of the children studied (123/647) tested positive for malaria.

The prevalence of malaria was 30% in children of mothers with no education, 17% in children of mothers with primary education, and 15% in children of mothers with education beyond primary school (P=0.001).

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for the effect of a child’s age and the study site, maternal education was still a significant predictor of malaria antigenemia.

“It doesn’t take a lot of education to teach a mom how to take simple precautions to prevent malaria in her child,” said study author Cary Ma, a medical student at the University of Alberta.

“All it takes is knowing the importance of using a bed net and knowing the importance of seeking care when your child has a fever. These are fairly straightforward, simple messages in the context of health and hygiene that can easily be conveyed, usually at an elementary or primary school level.”

“The World Health Organization is rolling out a new vaccine [RTS,S] in countries across Africa that has an efficacy of about 30%,” Dr Hawkes added.

“But children whose mothers are educated beyond the primary level have a 53% reduction in their malaria rates. So educating the mom has as profound an effect on childhood malaria as hundreds of millions of dollars spent on a vaccine.”

The researchers said this work builds upon previous studies that have shown the importance of maternal education in reducing child mortality and disease in other countries around the world.

The team noted that maternal education isn’t a magic bullet by itself, but they do believe it is part of the solution. They hope the lessons learned via this study can help lead policymakers to strengthen efforts to educate girls and women in the DRC and other malaria hotspots around the world. ![]()

One way to reduce the risk of malaria infection in children is to educate their mothers, according to a study published in Pathogens and Global Health.

The study suggested that educating mothers can be more effective in preventing childhood malaria than the malaria vaccine candidate RTS,S (Mosquirix).

Researchers said this finding can be explained by the fact that educated mothers know of ways to prevent malaria infection, such as using bed nets and taking their children for treatment if they develop a fever.

For this study, the researchers performed malaria testing in 647 children in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) who were between the ages of 2 months and 5 years.

The team also had the children’s parent or guardian fill out a survey related to demographics, socioeconomic status, maternal education, bed net use, and recent illness involving fever.

Results showed that mothers with a higher education level had children with a lower risk of malaria infection.

“This was not a small effect,” said study author Michael Hawkes, MD, PhD, of the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

“Maternal education had an enormous effect—equivalent to or greater than the leading biomedical vaccine against malaria.”

Overall, 19% of the children studied (123/647) tested positive for malaria.

The prevalence of malaria was 30% in children of mothers with no education, 17% in children of mothers with primary education, and 15% in children of mothers with education beyond primary school (P=0.001).

In a multivariate analysis adjusted for the effect of a child’s age and the study site, maternal education was still a significant predictor of malaria antigenemia.

“It doesn’t take a lot of education to teach a mom how to take simple precautions to prevent malaria in her child,” said study author Cary Ma, a medical student at the University of Alberta.

“All it takes is knowing the importance of using a bed net and knowing the importance of seeking care when your child has a fever. These are fairly straightforward, simple messages in the context of health and hygiene that can easily be conveyed, usually at an elementary or primary school level.”

“The World Health Organization is rolling out a new vaccine [RTS,S] in countries across Africa that has an efficacy of about 30%,” Dr Hawkes added.

“But children whose mothers are educated beyond the primary level have a 53% reduction in their malaria rates. So educating the mom has as profound an effect on childhood malaria as hundreds of millions of dollars spent on a vaccine.”

The researchers said this work builds upon previous studies that have shown the importance of maternal education in reducing child mortality and disease in other countries around the world.

The team noted that maternal education isn’t a magic bullet by itself, but they do believe it is part of the solution. They hope the lessons learned via this study can help lead policymakers to strengthen efforts to educate girls and women in the DRC and other malaria hotspots around the world.

Study: Most oncologists don’t discuss exercise with patients

Results of a small, single-center study suggest oncologists may not provide cancer patients with adequate guidance on exercise.

A majority of the patients and oncologists surveyed for this study placed importance on exercise during cancer care, but most of the oncologists failed to give patients recommendations on exercise.

“Our results indicate that exercise is perceived as important to patients with cancer, both from a patient and physician perspective,” said study author Agnes Smaradottir, MD, of Gundersen Health System in La Crosse, Wisconsin.

“However, physicians are reluctant to consistently include [physical activity] recommendations in their patient discussions.”

Dr Smaradottir and her colleagues reported these findings in JNCCN.

The researchers surveyed 20 cancer patients and 9 oncologists for this study.

The patients’ mean age was 64. Ten patients had stage I-III non-metastatic cancer after adjuvant therapy, and 10 had stage IV metastatic disease and were undergoing palliative treatment. Most patients had solid tumor malignancies, but 1 had chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

The oncologists’ mean age was 45, 56% were male, and they had a mean of 12 years of practice. Most (89%) said they exercise on a regular basis.

Discussions

Nineteen (95%) of the patients surveyed felt they benefited from exercise during treatment, but only 3 of the patients recalled being instructed to exercise.

Exercise was felt to be an equally important part of treatment and well-being for patients with early stage cancer treated with curative intent as well as patients receiving palliative therapy.

Although all the oncologists noted that exercise can benefit cancer patients, only 1 of the 9 surveyed documented discussion of exercise in patient charts.

Preferences and concerns

More than 80% of the patients said they would prefer a home-based exercise regimen that could be performed in alignment with their personal schedules and symptoms.

Patients also noted a preference that exercise recommendations come from their oncologists, as they have an established relationship and feel their oncologists best understand the complexities of their personalized treatment plans.

The oncologists, on the other hand, wanted to refer patients to specialist care for exercise recommendations. Reasons for this included the oncologists’ mounting clinic schedules and a lack of education about appropriate physical activity recommendations for patients.

The oncologists also expressed concern about asking patients to be more physically active during chemotherapy and radiation and expressed trepidation about prescribing exercise to frail patients with limited mobility.

“We were surprised by the gap in expectations regarding exercise recommendation between patients and providers,” Dr Smaradottir said. “Many providers, ourselves included, thought patients would prefer to be referred to an exercise center, but they clearly preferred to have a home-based program recommended by their oncologist.”

“Our findings highlight the value of examining both patient and provider attitudes and behavioral intentions. While we uncovered barriers to exercise recommendations, questions remain on how to bridge the gap between patient and provider preferences.”

Results of a small, single-center study suggest oncologists may not provide cancer patients with adequate guidance on exercise.

A majority of the patients and oncologists surveyed for this study placed importance on exercise during cancer care, but most of the oncologists failed to give patients recommendations on exercise.

“Our results indicate that exercise is perceived as important to patients with cancer, both from a patient and physician perspective,” said study author Agnes Smaradottir, MD, of Gundersen Health System in La Crosse, Wisconsin.

“However, physicians are reluctant to consistently include [physical activity] recommendations in their patient discussions.”

Dr Smaradottir and her colleagues reported these findings in JNCCN.

The researchers surveyed 20 cancer patients and 9 oncologists for this study.

The patients’ mean age was 64. Ten patients had stage I-III non-metastatic cancer after adjuvant therapy, and 10 had stage IV metastatic disease and were undergoing palliative treatment. Most patients had solid tumor malignancies, but 1 had chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

The oncologists’ mean age was 45, 56% were male, and they had a mean of 12 years of practice. Most (89%) said they exercise on a regular basis.

Discussions

Nineteen (95%) of the patients surveyed felt they benefited from exercise during treatment, but only 3 of the patients recalled being instructed to exercise.

Exercise was felt to be an equally important part of treatment and well-being for patients with early stage cancer treated with curative intent as well as patients receiving palliative therapy.