User login

Survey: Patients largely unaware of docs’ industry ties

A survey of nearly 2000 people suggests many Americans may not know if their physician receives industry payments.

A majority of the individuals surveyed were treated by a doctor who received some form of industry payment in the last year, but few of the patients were aware of these payments.

In fact, more than half of the patients did not know that accepting industry payments is something physicians may do.

“The findings suggest that although physicians who accept industry payments are in the minority, they are caring for a very substantial portion of America’s adult patient population,” said Genevieve Pham-Kanter, PhD, of Drexel University’s Dornsife School of Public Health in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

She and her colleagues reported these findings in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.

Since 2013, the Sunshine Act, part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, has required pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers to report gifts and payments they make to healthcare providers. This information is publicly available on the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Open Payments website.

Dr Pham-Kanter and her colleagues conducted their survey shortly before the first release of the Open Payments data in September 2014. However, payment data were already publicly available in certain states, nationwide via the Pro Publica website, and through disclosures made by pharmaceutical and medical device firms themselves (who had been required to release payment information as part of legal settlements or did so voluntarily).

Survey results

The researchers conducted their online survey in 3542 adults. Respondents were asked whether they were aware of industry payments and to name the physicians they had seen most frequently in the previous year.

Physician names were then linked to the Open Payment data to ascertain how often patients saw doctors who accepted industry payments.

There were 1987 respondents who could be matched to a specific physician. Sixty-five percent of these individuals had visited a physician who accepted an industry payment in the last 12 months, but only 5% of the respondents actually knew if their doctors received industry payments.

Forty-five percent of respondents said they knew about the practice of doctors receiving industry payments, and 12% said information about such payments was publicly available.

“These findings tell us that if you thought that your doctor was not receiving any money from industry, you’re most likely mistaken,” Dr Pham-Kanter said. “Patients should be aware of the incentives that their physicians face that may lead them to not always act in their patients’ best interest.”

In Open Payments, all physicians averaged $193 in yearly payments and gifts. But when measuring only the doctors visited by participants in the survey, the median payment amount over the last year was $510, more than 2.5 times the US average.

“We may be lulled into thinking this isn’t a big deal because the average payment amount across all doctors is low,” Dr Pham-Kanter said. “But that obscures the fact that most people are seeing doctors who receive the largest payments.”

“Drug companies have long known that even small gifts to physicians can be influential,” added study author Michelle Mello, JD, PhD, of Stanford University School of Medicine and Stanford Law School in California. “And research validates the notion that they tend to induce feelings of reciprocity.” ![]()

A survey of nearly 2000 people suggests many Americans may not know if their physician receives industry payments.

A majority of the individuals surveyed were treated by a doctor who received some form of industry payment in the last year, but few of the patients were aware of these payments.

In fact, more than half of the patients did not know that accepting industry payments is something physicians may do.

“The findings suggest that although physicians who accept industry payments are in the minority, they are caring for a very substantial portion of America’s adult patient population,” said Genevieve Pham-Kanter, PhD, of Drexel University’s Dornsife School of Public Health in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

She and her colleagues reported these findings in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.

Since 2013, the Sunshine Act, part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, has required pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers to report gifts and payments they make to healthcare providers. This information is publicly available on the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Open Payments website.

Dr Pham-Kanter and her colleagues conducted their survey shortly before the first release of the Open Payments data in September 2014. However, payment data were already publicly available in certain states, nationwide via the Pro Publica website, and through disclosures made by pharmaceutical and medical device firms themselves (who had been required to release payment information as part of legal settlements or did so voluntarily).

Survey results

The researchers conducted their online survey in 3542 adults. Respondents were asked whether they were aware of industry payments and to name the physicians they had seen most frequently in the previous year.

Physician names were then linked to the Open Payment data to ascertain how often patients saw doctors who accepted industry payments.

There were 1987 respondents who could be matched to a specific physician. Sixty-five percent of these individuals had visited a physician who accepted an industry payment in the last 12 months, but only 5% of the respondents actually knew if their doctors received industry payments.

Forty-five percent of respondents said they knew about the practice of doctors receiving industry payments, and 12% said information about such payments was publicly available.

“These findings tell us that if you thought that your doctor was not receiving any money from industry, you’re most likely mistaken,” Dr Pham-Kanter said. “Patients should be aware of the incentives that their physicians face that may lead them to not always act in their patients’ best interest.”

In Open Payments, all physicians averaged $193 in yearly payments and gifts. But when measuring only the doctors visited by participants in the survey, the median payment amount over the last year was $510, more than 2.5 times the US average.

“We may be lulled into thinking this isn’t a big deal because the average payment amount across all doctors is low,” Dr Pham-Kanter said. “But that obscures the fact that most people are seeing doctors who receive the largest payments.”

“Drug companies have long known that even small gifts to physicians can be influential,” added study author Michelle Mello, JD, PhD, of Stanford University School of Medicine and Stanford Law School in California. “And research validates the notion that they tend to induce feelings of reciprocity.” ![]()

A survey of nearly 2000 people suggests many Americans may not know if their physician receives industry payments.

A majority of the individuals surveyed were treated by a doctor who received some form of industry payment in the last year, but few of the patients were aware of these payments.

In fact, more than half of the patients did not know that accepting industry payments is something physicians may do.

“The findings suggest that although physicians who accept industry payments are in the minority, they are caring for a very substantial portion of America’s adult patient population,” said Genevieve Pham-Kanter, PhD, of Drexel University’s Dornsife School of Public Health in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

She and her colleagues reported these findings in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.

Since 2013, the Sunshine Act, part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, has required pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers to report gifts and payments they make to healthcare providers. This information is publicly available on the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Open Payments website.

Dr Pham-Kanter and her colleagues conducted their survey shortly before the first release of the Open Payments data in September 2014. However, payment data were already publicly available in certain states, nationwide via the Pro Publica website, and through disclosures made by pharmaceutical and medical device firms themselves (who had been required to release payment information as part of legal settlements or did so voluntarily).

Survey results

The researchers conducted their online survey in 3542 adults. Respondents were asked whether they were aware of industry payments and to name the physicians they had seen most frequently in the previous year.

Physician names were then linked to the Open Payment data to ascertain how often patients saw doctors who accepted industry payments.

There were 1987 respondents who could be matched to a specific physician. Sixty-five percent of these individuals had visited a physician who accepted an industry payment in the last 12 months, but only 5% of the respondents actually knew if their doctors received industry payments.

Forty-five percent of respondents said they knew about the practice of doctors receiving industry payments, and 12% said information about such payments was publicly available.

“These findings tell us that if you thought that your doctor was not receiving any money from industry, you’re most likely mistaken,” Dr Pham-Kanter said. “Patients should be aware of the incentives that their physicians face that may lead them to not always act in their patients’ best interest.”

In Open Payments, all physicians averaged $193 in yearly payments and gifts. But when measuring only the doctors visited by participants in the survey, the median payment amount over the last year was $510, more than 2.5 times the US average.

“We may be lulled into thinking this isn’t a big deal because the average payment amount across all doctors is low,” Dr Pham-Kanter said. “But that obscures the fact that most people are seeing doctors who receive the largest payments.”

“Drug companies have long known that even small gifts to physicians can be influential,” added study author Michelle Mello, JD, PhD, of Stanford University School of Medicine and Stanford Law School in California. “And research validates the notion that they tend to induce feelings of reciprocity.” ![]()

Exercise better than meds to reduce fatigue in cancer patients

Exercise and/or psychological therapy work better than medications to reduce cancer-related fatigue, according to research published in JAMA Oncology.

Researchers conducted a review and meta-analysis of more than 113 studies and found that exercise and psychological interventions, as well as a combination of both, were associated with reduced fatigue during and after cancer treatment.

However, pharmaceutical interventions were not associated with the same magnitude of improvement.

The researchers therefore concluded that exercise and psychological therapy should be recommended over medications.

“If a cancer patient is having trouble with fatigue, rather than looking for extra cups of coffee, a nap, or a pharmaceutical solution, consider a 15-minute walk,” said study author Karen Mustian, PhD, of the University of Rochester Medical Center in Rochester, New York.

“It’s a really simple concept, but it’s very hard for patients and the medical community to wrap their heads around it because these interventions have not been front-and-center in the past. Our research gives clinicians a valuable asset to alleviate cancer-related fatigue.”

Dr Mustian and her colleagues reached their conclusions after analyzing data from 113 randomized clinical trials testing various treatments for cancer-related fatigue.

There were 11,525 patients enrolled in these studies. Nearly half (46.9%) were women with breast cancer. Ten studies focused on other types of cancer and enrolled only men.

Dr Mustian and her colleagues performed a meta-analysis to establish and compare the mean weighted effect sizes (WESs) of the fatigue treatments.

The team found that exercise alone—whether aerobic or anaerobic—reduced cancer-related fatigue most significantly. The WES was 0.30 (95% CI, 0.25-0.36; P<0.001).

Psychological interventions—such as therapy designed to provide education, change personal behavior, and adapt the way a person thinks about his or her circumstances—also improved fatigue. The WES was 0.27 (95% CI, 0.21-0.330.30; P<0.001).

A combination of psychological interventions and exercise had a significant improvement on fatigue as well. The WES was 0.26 (95% CI, 0.13-0.38; P<0.001).

However, the drugs tested for treating cancer-related fatigue—paroxetine hydrochloride, modafinil, armodafinil, methylphenidate hydrochloride, dexymethylphenidate, dexamphetamine, and methylprednisolone—were not as effective as the other interventions. The WES was 0.09 (95% CI, 0.00-0.19; P=0.05).

“The literature bears out that these drugs don’t work very well, although they are continually prescribed,” Dr Mustian said. “Cancer patients already take a lot of medications, and they all come with risks and side effects. So any time you can subtract a pharmaceutical from the picture it usually benefits patients.” ![]()

Exercise and/or psychological therapy work better than medications to reduce cancer-related fatigue, according to research published in JAMA Oncology.

Researchers conducted a review and meta-analysis of more than 113 studies and found that exercise and psychological interventions, as well as a combination of both, were associated with reduced fatigue during and after cancer treatment.

However, pharmaceutical interventions were not associated with the same magnitude of improvement.

The researchers therefore concluded that exercise and psychological therapy should be recommended over medications.

“If a cancer patient is having trouble with fatigue, rather than looking for extra cups of coffee, a nap, or a pharmaceutical solution, consider a 15-minute walk,” said study author Karen Mustian, PhD, of the University of Rochester Medical Center in Rochester, New York.

“It’s a really simple concept, but it’s very hard for patients and the medical community to wrap their heads around it because these interventions have not been front-and-center in the past. Our research gives clinicians a valuable asset to alleviate cancer-related fatigue.”

Dr Mustian and her colleagues reached their conclusions after analyzing data from 113 randomized clinical trials testing various treatments for cancer-related fatigue.

There were 11,525 patients enrolled in these studies. Nearly half (46.9%) were women with breast cancer. Ten studies focused on other types of cancer and enrolled only men.

Dr Mustian and her colleagues performed a meta-analysis to establish and compare the mean weighted effect sizes (WESs) of the fatigue treatments.

The team found that exercise alone—whether aerobic or anaerobic—reduced cancer-related fatigue most significantly. The WES was 0.30 (95% CI, 0.25-0.36; P<0.001).

Psychological interventions—such as therapy designed to provide education, change personal behavior, and adapt the way a person thinks about his or her circumstances—also improved fatigue. The WES was 0.27 (95% CI, 0.21-0.330.30; P<0.001).

A combination of psychological interventions and exercise had a significant improvement on fatigue as well. The WES was 0.26 (95% CI, 0.13-0.38; P<0.001).

However, the drugs tested for treating cancer-related fatigue—paroxetine hydrochloride, modafinil, armodafinil, methylphenidate hydrochloride, dexymethylphenidate, dexamphetamine, and methylprednisolone—were not as effective as the other interventions. The WES was 0.09 (95% CI, 0.00-0.19; P=0.05).

“The literature bears out that these drugs don’t work very well, although they are continually prescribed,” Dr Mustian said. “Cancer patients already take a lot of medications, and they all come with risks and side effects. So any time you can subtract a pharmaceutical from the picture it usually benefits patients.” ![]()

Exercise and/or psychological therapy work better than medications to reduce cancer-related fatigue, according to research published in JAMA Oncology.

Researchers conducted a review and meta-analysis of more than 113 studies and found that exercise and psychological interventions, as well as a combination of both, were associated with reduced fatigue during and after cancer treatment.

However, pharmaceutical interventions were not associated with the same magnitude of improvement.

The researchers therefore concluded that exercise and psychological therapy should be recommended over medications.

“If a cancer patient is having trouble with fatigue, rather than looking for extra cups of coffee, a nap, or a pharmaceutical solution, consider a 15-minute walk,” said study author Karen Mustian, PhD, of the University of Rochester Medical Center in Rochester, New York.

“It’s a really simple concept, but it’s very hard for patients and the medical community to wrap their heads around it because these interventions have not been front-and-center in the past. Our research gives clinicians a valuable asset to alleviate cancer-related fatigue.”

Dr Mustian and her colleagues reached their conclusions after analyzing data from 113 randomized clinical trials testing various treatments for cancer-related fatigue.

There were 11,525 patients enrolled in these studies. Nearly half (46.9%) were women with breast cancer. Ten studies focused on other types of cancer and enrolled only men.

Dr Mustian and her colleagues performed a meta-analysis to establish and compare the mean weighted effect sizes (WESs) of the fatigue treatments.

The team found that exercise alone—whether aerobic or anaerobic—reduced cancer-related fatigue most significantly. The WES was 0.30 (95% CI, 0.25-0.36; P<0.001).

Psychological interventions—such as therapy designed to provide education, change personal behavior, and adapt the way a person thinks about his or her circumstances—also improved fatigue. The WES was 0.27 (95% CI, 0.21-0.330.30; P<0.001).

A combination of psychological interventions and exercise had a significant improvement on fatigue as well. The WES was 0.26 (95% CI, 0.13-0.38; P<0.001).

However, the drugs tested for treating cancer-related fatigue—paroxetine hydrochloride, modafinil, armodafinil, methylphenidate hydrochloride, dexymethylphenidate, dexamphetamine, and methylprednisolone—were not as effective as the other interventions. The WES was 0.09 (95% CI, 0.00-0.19; P=0.05).

“The literature bears out that these drugs don’t work very well, although they are continually prescribed,” Dr Mustian said. “Cancer patients already take a lot of medications, and they all come with risks and side effects. So any time you can subtract a pharmaceutical from the picture it usually benefits patients.” ![]()

Hospital floors pose infection risk, team says

Hospital room floors may be an overlooked source of infection, according to a study published in the American Journal of Infection Control.

Researchers surveyed 5 hospitals and found that floors in patient rooms were often contaminated with pathogens.

Certain objects, such as personal items and medical devices and supplies, were in contact with the floor, and touching these objects resulted in the transfer of pathogens to bare and gloved hands.

Abhishek Deshpande, MD, PhD, of Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine in Cleveland, Ohio, and his colleagues conducted this research.

The team cultured 318 floor sites from 159 patient rooms (2 sites per room) in 5 hospitals in the Cleveland area. The rooms included both Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) isolation rooms and non-CDI rooms.

The researchers also cultured hands (gloved and bare) as well as other “high-touch” surfaces such as clothing and medical devices/supplies.

The team found that floors in patient rooms were often contaminated with Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), and C difficile.

C difficile was recovered in 55% of CDI rooms and 47% of non-CDI rooms. MRSA was recovered in 32% of CDI rooms and 8% of non-CDI rooms. VRE was recovered in 30% of CDI rooms and 13% of non-CDI rooms.

The researchers said the frequency of contamination was similar for each of the 5 hospitals and from room and bathroom floor sites.

Of the 100 occupied rooms surveyed, 41% had one or more high-touch objects that were in contact with the floor. These included personal items (eg, clothing, canes, and cellular phone chargers), medical devices and supplies (eg, pulse oximeter, call button, heating pad, urinal, blood pressure cuff, wash basin, and heel protector), and bed linens or towels.

The findings indicate that handling such items resulted in the transfer of pathogens. All 3 pathogens were recovered from bare or gloved hand cultures—MRSA in 6 (18%), VRE in 2 (6%), and C difficile in 1 (3%).

The researchers said these results suggest hospital floors could be an underappreciated source for dissemination of pathogens and are an important area for additional research.

“Understanding gaps in infection prevention is critically important for institutions seeking to improve the quality of care offered to patients,” said Linda Greene, RN, current president of the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology.

“Even though most facilities believe they are taking the proper precautions, this study points out the importance of ensuring cleanliness of the hospital environment and the need for education of both staff and patients on this issue.” ![]()

Hospital room floors may be an overlooked source of infection, according to a study published in the American Journal of Infection Control.

Researchers surveyed 5 hospitals and found that floors in patient rooms were often contaminated with pathogens.

Certain objects, such as personal items and medical devices and supplies, were in contact with the floor, and touching these objects resulted in the transfer of pathogens to bare and gloved hands.

Abhishek Deshpande, MD, PhD, of Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine in Cleveland, Ohio, and his colleagues conducted this research.

The team cultured 318 floor sites from 159 patient rooms (2 sites per room) in 5 hospitals in the Cleveland area. The rooms included both Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) isolation rooms and non-CDI rooms.

The researchers also cultured hands (gloved and bare) as well as other “high-touch” surfaces such as clothing and medical devices/supplies.

The team found that floors in patient rooms were often contaminated with Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), and C difficile.

C difficile was recovered in 55% of CDI rooms and 47% of non-CDI rooms. MRSA was recovered in 32% of CDI rooms and 8% of non-CDI rooms. VRE was recovered in 30% of CDI rooms and 13% of non-CDI rooms.

The researchers said the frequency of contamination was similar for each of the 5 hospitals and from room and bathroom floor sites.

Of the 100 occupied rooms surveyed, 41% had one or more high-touch objects that were in contact with the floor. These included personal items (eg, clothing, canes, and cellular phone chargers), medical devices and supplies (eg, pulse oximeter, call button, heating pad, urinal, blood pressure cuff, wash basin, and heel protector), and bed linens or towels.

The findings indicate that handling such items resulted in the transfer of pathogens. All 3 pathogens were recovered from bare or gloved hand cultures—MRSA in 6 (18%), VRE in 2 (6%), and C difficile in 1 (3%).

The researchers said these results suggest hospital floors could be an underappreciated source for dissemination of pathogens and are an important area for additional research.

“Understanding gaps in infection prevention is critically important for institutions seeking to improve the quality of care offered to patients,” said Linda Greene, RN, current president of the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology.

“Even though most facilities believe they are taking the proper precautions, this study points out the importance of ensuring cleanliness of the hospital environment and the need for education of both staff and patients on this issue.” ![]()

Hospital room floors may be an overlooked source of infection, according to a study published in the American Journal of Infection Control.

Researchers surveyed 5 hospitals and found that floors in patient rooms were often contaminated with pathogens.

Certain objects, such as personal items and medical devices and supplies, were in contact with the floor, and touching these objects resulted in the transfer of pathogens to bare and gloved hands.

Abhishek Deshpande, MD, PhD, of Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine in Cleveland, Ohio, and his colleagues conducted this research.

The team cultured 318 floor sites from 159 patient rooms (2 sites per room) in 5 hospitals in the Cleveland area. The rooms included both Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) isolation rooms and non-CDI rooms.

The researchers also cultured hands (gloved and bare) as well as other “high-touch” surfaces such as clothing and medical devices/supplies.

The team found that floors in patient rooms were often contaminated with Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), and C difficile.

C difficile was recovered in 55% of CDI rooms and 47% of non-CDI rooms. MRSA was recovered in 32% of CDI rooms and 8% of non-CDI rooms. VRE was recovered in 30% of CDI rooms and 13% of non-CDI rooms.

The researchers said the frequency of contamination was similar for each of the 5 hospitals and from room and bathroom floor sites.

Of the 100 occupied rooms surveyed, 41% had one or more high-touch objects that were in contact with the floor. These included personal items (eg, clothing, canes, and cellular phone chargers), medical devices and supplies (eg, pulse oximeter, call button, heating pad, urinal, blood pressure cuff, wash basin, and heel protector), and bed linens or towels.

The findings indicate that handling such items resulted in the transfer of pathogens. All 3 pathogens were recovered from bare or gloved hand cultures—MRSA in 6 (18%), VRE in 2 (6%), and C difficile in 1 (3%).

The researchers said these results suggest hospital floors could be an underappreciated source for dissemination of pathogens and are an important area for additional research.

“Understanding gaps in infection prevention is critically important for institutions seeking to improve the quality of care offered to patients,” said Linda Greene, RN, current president of the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology.

“Even though most facilities believe they are taking the proper precautions, this study points out the importance of ensuring cleanliness of the hospital environment and the need for education of both staff and patients on this issue.” ![]()

Vaccine can fight different malaria strains

An investigational malaria vaccine can protect healthy adults from infection with a malaria strain different from that contained in the vaccine, according to a phase 1 study published in PNAS.

The vaccine, known as the PfSPZ Vaccine, contains weakened Plasmodium falciparum sporozoites that are able to generate a protective immune response against live malaria infection.

Prior research showed that the PfSPZ Vaccine can provide long-term protection against a single malaria strain matched to the vaccine.

The new study has shown that the PfSPZ Vaccine can protect against a different strain of P falciparum as well.

“An effective malaria vaccine will need to protect people living in endemic areas against multiple strains of the mosquito-borne disease,” said Anthony S. Fauci, MD, of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) in Bethesda, Maryland.

“These new findings showing cross-protection with the PfSPZ Vaccine suggest that it may be able to accomplish this goal.”

The PfSPZ Vaccine was developed by Sanaria Inc. The company designed, manufactured, and provided PfSPZ Vaccine and the heterologous challenge mosquitoes for this trial. The NIAID supported the development of the vaccine through several grants.

Study details

The study enrolled 31 healthy, malaria-naive adults ages 19 to 45.

Fifteen subjects were scheduled to receive 3 doses of the PfSPZ Vaccine—9.0 × 105 PfSPZ administered intravenously 3 times at 8-week intervals. The remaining subjects served as controls.

Nineteen weeks after receiving the final dose of the test vaccine, vaccinated subjects and controls were exposed to bites from mosquitoes infected with the same strain of P falciparum parasites (NF54) that were used to manufacture PfSPZ Vaccine.

Nine of the 14 subjects (64%) who received PfSPZ Vaccine demonstrated no evidence of malaria parasites. All 6 of the non-vaccinated subjects who were challenged at the same time had malaria parasites in their blood.

Of the 9 subjects who showed no evidence of malaria, 6 subjects were again exposed to mosquito bites, this time from mosquitoes infected with a different strain of P falciparum (Pf7G8), 33 weeks after the final immunization.

In this group, 5 of the 6 subjects (83%) were protected against malaria infection. None of the 6 control subjects who were challenged were protected.

“Achieving durable protection against a malaria strain different from the vaccine strain, over 8 months after vaccination, is an indication of this vaccine’s potential,” said Robert A. Seder, MD, of NIAID.

“If we can build on these findings with the PfSPZ Vaccine and induce higher efficacy, we may be on our way to a vaccine that could effectively protect people against a variety of malaria parasites where the disease is prevalent.”

The researchers found the PfSPZ Vaccine activated T cells and induced antibody responses in all vaccine recipients. Vaccine-specific T-cell responses were comparable when measured against both malaria challenge strains, providing some insight into how the vaccine was mediating protection.

Ongoing research should determine whether protective efficacy can be improved by changes to the PfSPZ Vaccine dose and number of immunizations.

A phase 2 trial testing 3 different dosages in a 3-dose vaccine regimen is now underway in 5-to 12-month-old infants in Western Kenya to assess safety and efficacy of the vaccine against natural infection. ![]()

An investigational malaria vaccine can protect healthy adults from infection with a malaria strain different from that contained in the vaccine, according to a phase 1 study published in PNAS.

The vaccine, known as the PfSPZ Vaccine, contains weakened Plasmodium falciparum sporozoites that are able to generate a protective immune response against live malaria infection.

Prior research showed that the PfSPZ Vaccine can provide long-term protection against a single malaria strain matched to the vaccine.

The new study has shown that the PfSPZ Vaccine can protect against a different strain of P falciparum as well.

“An effective malaria vaccine will need to protect people living in endemic areas against multiple strains of the mosquito-borne disease,” said Anthony S. Fauci, MD, of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) in Bethesda, Maryland.

“These new findings showing cross-protection with the PfSPZ Vaccine suggest that it may be able to accomplish this goal.”

The PfSPZ Vaccine was developed by Sanaria Inc. The company designed, manufactured, and provided PfSPZ Vaccine and the heterologous challenge mosquitoes for this trial. The NIAID supported the development of the vaccine through several grants.

Study details

The study enrolled 31 healthy, malaria-naive adults ages 19 to 45.

Fifteen subjects were scheduled to receive 3 doses of the PfSPZ Vaccine—9.0 × 105 PfSPZ administered intravenously 3 times at 8-week intervals. The remaining subjects served as controls.

Nineteen weeks after receiving the final dose of the test vaccine, vaccinated subjects and controls were exposed to bites from mosquitoes infected with the same strain of P falciparum parasites (NF54) that were used to manufacture PfSPZ Vaccine.

Nine of the 14 subjects (64%) who received PfSPZ Vaccine demonstrated no evidence of malaria parasites. All 6 of the non-vaccinated subjects who were challenged at the same time had malaria parasites in their blood.

Of the 9 subjects who showed no evidence of malaria, 6 subjects were again exposed to mosquito bites, this time from mosquitoes infected with a different strain of P falciparum (Pf7G8), 33 weeks after the final immunization.

In this group, 5 of the 6 subjects (83%) were protected against malaria infection. None of the 6 control subjects who were challenged were protected.

“Achieving durable protection against a malaria strain different from the vaccine strain, over 8 months after vaccination, is an indication of this vaccine’s potential,” said Robert A. Seder, MD, of NIAID.

“If we can build on these findings with the PfSPZ Vaccine and induce higher efficacy, we may be on our way to a vaccine that could effectively protect people against a variety of malaria parasites where the disease is prevalent.”

The researchers found the PfSPZ Vaccine activated T cells and induced antibody responses in all vaccine recipients. Vaccine-specific T-cell responses were comparable when measured against both malaria challenge strains, providing some insight into how the vaccine was mediating protection.

Ongoing research should determine whether protective efficacy can be improved by changes to the PfSPZ Vaccine dose and number of immunizations.

A phase 2 trial testing 3 different dosages in a 3-dose vaccine regimen is now underway in 5-to 12-month-old infants in Western Kenya to assess safety and efficacy of the vaccine against natural infection. ![]()

An investigational malaria vaccine can protect healthy adults from infection with a malaria strain different from that contained in the vaccine, according to a phase 1 study published in PNAS.

The vaccine, known as the PfSPZ Vaccine, contains weakened Plasmodium falciparum sporozoites that are able to generate a protective immune response against live malaria infection.

Prior research showed that the PfSPZ Vaccine can provide long-term protection against a single malaria strain matched to the vaccine.

The new study has shown that the PfSPZ Vaccine can protect against a different strain of P falciparum as well.

“An effective malaria vaccine will need to protect people living in endemic areas against multiple strains of the mosquito-borne disease,” said Anthony S. Fauci, MD, of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) in Bethesda, Maryland.

“These new findings showing cross-protection with the PfSPZ Vaccine suggest that it may be able to accomplish this goal.”

The PfSPZ Vaccine was developed by Sanaria Inc. The company designed, manufactured, and provided PfSPZ Vaccine and the heterologous challenge mosquitoes for this trial. The NIAID supported the development of the vaccine through several grants.

Study details

The study enrolled 31 healthy, malaria-naive adults ages 19 to 45.

Fifteen subjects were scheduled to receive 3 doses of the PfSPZ Vaccine—9.0 × 105 PfSPZ administered intravenously 3 times at 8-week intervals. The remaining subjects served as controls.

Nineteen weeks after receiving the final dose of the test vaccine, vaccinated subjects and controls were exposed to bites from mosquitoes infected with the same strain of P falciparum parasites (NF54) that were used to manufacture PfSPZ Vaccine.

Nine of the 14 subjects (64%) who received PfSPZ Vaccine demonstrated no evidence of malaria parasites. All 6 of the non-vaccinated subjects who were challenged at the same time had malaria parasites in their blood.

Of the 9 subjects who showed no evidence of malaria, 6 subjects were again exposed to mosquito bites, this time from mosquitoes infected with a different strain of P falciparum (Pf7G8), 33 weeks after the final immunization.

In this group, 5 of the 6 subjects (83%) were protected against malaria infection. None of the 6 control subjects who were challenged were protected.

“Achieving durable protection against a malaria strain different from the vaccine strain, over 8 months after vaccination, is an indication of this vaccine’s potential,” said Robert A. Seder, MD, of NIAID.

“If we can build on these findings with the PfSPZ Vaccine and induce higher efficacy, we may be on our way to a vaccine that could effectively protect people against a variety of malaria parasites where the disease is prevalent.”

The researchers found the PfSPZ Vaccine activated T cells and induced antibody responses in all vaccine recipients. Vaccine-specific T-cell responses were comparable when measured against both malaria challenge strains, providing some insight into how the vaccine was mediating protection.

Ongoing research should determine whether protective efficacy can be improved by changes to the PfSPZ Vaccine dose and number of immunizations.

A phase 2 trial testing 3 different dosages in a 3-dose vaccine regimen is now underway in 5-to 12-month-old infants in Western Kenya to assess safety and efficacy of the vaccine against natural infection. ![]()

CHMP recommends authorization of antiemetic agent

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended marketing authorization for the antiemetic agent rolapitant (Varuby) as a treatment for adults with cancer.

The drug is intended to be used in combination with other antiemetic agents to prevent delayed nausea and vomiting associated with highly and moderately emetogenic chemotherapy.

The CHMP’s recommendation regarding rolapitant has been forwarded to the European Commission, which is expected to make a decision about the drug within 2 months.

If the commission authorizes marketing of rolapitant, the drug will be available as 90 mg film-coated tablets.

The applicant for rolapitant is Tesaro UK Limited.

Rolapitant clinical trials

Results from three phase 3 trials suggested that rolapitant (at 180 mg) in combination with a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone was more effective than the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone on their own (active control).

The 3-drug combination demonstrated a significant reduction in episodes of vomiting or use of rescue medication during the 25- to 120-hour period following administration of highly emetogenic and moderately emetogenic chemotherapy regimens.

In addition, patients who received rolapitant reported experiencing less nausea that interfered with normal daily life and fewer episodes of vomiting or retching over multiple cycles of chemotherapy.

Highly emetogenic chemotherapy

The clinical profile of rolapitant in cisplatin-based, highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC) was confirmed in two phase 3 studies: HEC1 and HEC2. Results from these trials were published in The Lancet Oncology in August 2015.

Both trials met their primary endpoint of complete response (CR) and demonstrated statistical superiority of the rolapitant combination compared to active control.

In HEC1, 264 patients received the rolapitant combination, and 262 received active control. The proportion of patients achieving a CR was 72.7% and 58.4%, respectively (P<0.001).

In HEC2, 271 patients received the rolapitant combination, and 273 received active control. The proportion of patients achieving a CR was 70.1% and 61.9%, respectively (P=0.043).

The most common adverse events (in the rolapitant and control groups, respectively) were neutropenia (9% and 8%), hiccups (5% and 4%), and abdominal pain (3% and 2%).

Moderately emetogenic chemotherapy

Researchers conducted another phase 3 trial to compare the rolapitant combination with active control in 1332 patients receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Results from this trial were also published in The Lancet Oncology in August 2015.

This trial met its primary endpoint of CR and demonstrated statistical superiority of the rolapitant combination compared to active control. The proportion of patients achieving a CR was 71.3% and 61.6%, respectively (P<0.001).

The most common adverse events (in the rolapitant and control groups, respectively) were decreased appetite (9% and 7%), neutropenia (7% and 6%), dizziness (6% and 4%), dyspepsia (4% and 2%), urinary tract infection (4% and 3%), stomatitis (4% and 2%), and anemia (3% and 2%). ![]()

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended marketing authorization for the antiemetic agent rolapitant (Varuby) as a treatment for adults with cancer.

The drug is intended to be used in combination with other antiemetic agents to prevent delayed nausea and vomiting associated with highly and moderately emetogenic chemotherapy.

The CHMP’s recommendation regarding rolapitant has been forwarded to the European Commission, which is expected to make a decision about the drug within 2 months.

If the commission authorizes marketing of rolapitant, the drug will be available as 90 mg film-coated tablets.

The applicant for rolapitant is Tesaro UK Limited.

Rolapitant clinical trials

Results from three phase 3 trials suggested that rolapitant (at 180 mg) in combination with a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone was more effective than the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone on their own (active control).

The 3-drug combination demonstrated a significant reduction in episodes of vomiting or use of rescue medication during the 25- to 120-hour period following administration of highly emetogenic and moderately emetogenic chemotherapy regimens.

In addition, patients who received rolapitant reported experiencing less nausea that interfered with normal daily life and fewer episodes of vomiting or retching over multiple cycles of chemotherapy.

Highly emetogenic chemotherapy

The clinical profile of rolapitant in cisplatin-based, highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC) was confirmed in two phase 3 studies: HEC1 and HEC2. Results from these trials were published in The Lancet Oncology in August 2015.

Both trials met their primary endpoint of complete response (CR) and demonstrated statistical superiority of the rolapitant combination compared to active control.

In HEC1, 264 patients received the rolapitant combination, and 262 received active control. The proportion of patients achieving a CR was 72.7% and 58.4%, respectively (P<0.001).

In HEC2, 271 patients received the rolapitant combination, and 273 received active control. The proportion of patients achieving a CR was 70.1% and 61.9%, respectively (P=0.043).

The most common adverse events (in the rolapitant and control groups, respectively) were neutropenia (9% and 8%), hiccups (5% and 4%), and abdominal pain (3% and 2%).

Moderately emetogenic chemotherapy

Researchers conducted another phase 3 trial to compare the rolapitant combination with active control in 1332 patients receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Results from this trial were also published in The Lancet Oncology in August 2015.

This trial met its primary endpoint of CR and demonstrated statistical superiority of the rolapitant combination compared to active control. The proportion of patients achieving a CR was 71.3% and 61.6%, respectively (P<0.001).

The most common adverse events (in the rolapitant and control groups, respectively) were decreased appetite (9% and 7%), neutropenia (7% and 6%), dizziness (6% and 4%), dyspepsia (4% and 2%), urinary tract infection (4% and 3%), stomatitis (4% and 2%), and anemia (3% and 2%). ![]()

The European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has recommended marketing authorization for the antiemetic agent rolapitant (Varuby) as a treatment for adults with cancer.

The drug is intended to be used in combination with other antiemetic agents to prevent delayed nausea and vomiting associated with highly and moderately emetogenic chemotherapy.

The CHMP’s recommendation regarding rolapitant has been forwarded to the European Commission, which is expected to make a decision about the drug within 2 months.

If the commission authorizes marketing of rolapitant, the drug will be available as 90 mg film-coated tablets.

The applicant for rolapitant is Tesaro UK Limited.

Rolapitant clinical trials

Results from three phase 3 trials suggested that rolapitant (at 180 mg) in combination with a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone was more effective than the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone on their own (active control).

The 3-drug combination demonstrated a significant reduction in episodes of vomiting or use of rescue medication during the 25- to 120-hour period following administration of highly emetogenic and moderately emetogenic chemotherapy regimens.

In addition, patients who received rolapitant reported experiencing less nausea that interfered with normal daily life and fewer episodes of vomiting or retching over multiple cycles of chemotherapy.

Highly emetogenic chemotherapy

The clinical profile of rolapitant in cisplatin-based, highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC) was confirmed in two phase 3 studies: HEC1 and HEC2. Results from these trials were published in The Lancet Oncology in August 2015.

Both trials met their primary endpoint of complete response (CR) and demonstrated statistical superiority of the rolapitant combination compared to active control.

In HEC1, 264 patients received the rolapitant combination, and 262 received active control. The proportion of patients achieving a CR was 72.7% and 58.4%, respectively (P<0.001).

In HEC2, 271 patients received the rolapitant combination, and 273 received active control. The proportion of patients achieving a CR was 70.1% and 61.9%, respectively (P=0.043).

The most common adverse events (in the rolapitant and control groups, respectively) were neutropenia (9% and 8%), hiccups (5% and 4%), and abdominal pain (3% and 2%).

Moderately emetogenic chemotherapy

Researchers conducted another phase 3 trial to compare the rolapitant combination with active control in 1332 patients receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Results from this trial were also published in The Lancet Oncology in August 2015.

This trial met its primary endpoint of CR and demonstrated statistical superiority of the rolapitant combination compared to active control. The proportion of patients achieving a CR was 71.3% and 61.6%, respectively (P<0.001).

The most common adverse events (in the rolapitant and control groups, respectively) were decreased appetite (9% and 7%), neutropenia (7% and 6%), dizziness (6% and 4%), dyspepsia (4% and 2%), urinary tract infection (4% and 3%), stomatitis (4% and 2%), and anemia (3% and 2%). ![]()

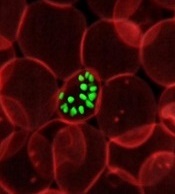

First case of artemisinin resistance in Africa

Researchers have identified the first known case of artemisinin-resistant malaria originating in Africa, according to a letter published in NEJM.

Resistant Plasmodium falciparum parasites were detected in a Chinese man who had travelled from Equatorial Guinea to China.

The finding means Africa has joined Southeast Asia in hosting parasites that are partially resistant to the first-line antimalaria drug, artemisinin.

Researchers were able to confirm that the parasites in the current case carried a new mutation in the Kelch13 (K13) gene, the main driver for artemisinin resistance in Asia.

Then, the team set out to determine whether the parasite originated from Africa or Southeast Asia.

“We used whole-genome sequencing and bioinformatics tools we had previously developed—like detectives trying to link the culprit parasite to the crime scene,” explained Arnab Pain, PhD, of King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Thuwal, Saudi Arabia.

Sequencing and analysis of P falciparum DNA unveiled its origin by disclosing the single nucleotide polymorphisms that vary according to the geographical source of the strain.

The researchers used the nuclear DNA, as well as the one present in 2 organelles of the parasite—the mitochondrium and the apicoplast.

Both methods independently validated the origin of the parasite as West African, confirming the first case of artemisinin resistance mediated by a K13 gene mutation on the African continent.

“The spread of artemisinin resistance in Africa would be a major setback in the fight against malaria, as ACT [artemisinin-based combination therapy] is the only effective and widely used antimalarial treatment at the moment,” Dr Pain said. “Therefore, it is very important to regularly monitor artemisinin resistance worldwide.” ![]()

Researchers have identified the first known case of artemisinin-resistant malaria originating in Africa, according to a letter published in NEJM.

Resistant Plasmodium falciparum parasites were detected in a Chinese man who had travelled from Equatorial Guinea to China.

The finding means Africa has joined Southeast Asia in hosting parasites that are partially resistant to the first-line antimalaria drug, artemisinin.

Researchers were able to confirm that the parasites in the current case carried a new mutation in the Kelch13 (K13) gene, the main driver for artemisinin resistance in Asia.

Then, the team set out to determine whether the parasite originated from Africa or Southeast Asia.

“We used whole-genome sequencing and bioinformatics tools we had previously developed—like detectives trying to link the culprit parasite to the crime scene,” explained Arnab Pain, PhD, of King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Thuwal, Saudi Arabia.

Sequencing and analysis of P falciparum DNA unveiled its origin by disclosing the single nucleotide polymorphisms that vary according to the geographical source of the strain.

The researchers used the nuclear DNA, as well as the one present in 2 organelles of the parasite—the mitochondrium and the apicoplast.

Both methods independently validated the origin of the parasite as West African, confirming the first case of artemisinin resistance mediated by a K13 gene mutation on the African continent.

“The spread of artemisinin resistance in Africa would be a major setback in the fight against malaria, as ACT [artemisinin-based combination therapy] is the only effective and widely used antimalarial treatment at the moment,” Dr Pain said. “Therefore, it is very important to regularly monitor artemisinin resistance worldwide.” ![]()

Researchers have identified the first known case of artemisinin-resistant malaria originating in Africa, according to a letter published in NEJM.

Resistant Plasmodium falciparum parasites were detected in a Chinese man who had travelled from Equatorial Guinea to China.

The finding means Africa has joined Southeast Asia in hosting parasites that are partially resistant to the first-line antimalaria drug, artemisinin.

Researchers were able to confirm that the parasites in the current case carried a new mutation in the Kelch13 (K13) gene, the main driver for artemisinin resistance in Asia.

Then, the team set out to determine whether the parasite originated from Africa or Southeast Asia.

“We used whole-genome sequencing and bioinformatics tools we had previously developed—like detectives trying to link the culprit parasite to the crime scene,” explained Arnab Pain, PhD, of King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Thuwal, Saudi Arabia.

Sequencing and analysis of P falciparum DNA unveiled its origin by disclosing the single nucleotide polymorphisms that vary according to the geographical source of the strain.

The researchers used the nuclear DNA, as well as the one present in 2 organelles of the parasite—the mitochondrium and the apicoplast.

Both methods independently validated the origin of the parasite as West African, confirming the first case of artemisinin resistance mediated by a K13 gene mutation on the African continent.

“The spread of artemisinin resistance in Africa would be a major setback in the fight against malaria, as ACT [artemisinin-based combination therapy] is the only effective and widely used antimalarial treatment at the moment,” Dr Pain said. “Therefore, it is very important to regularly monitor artemisinin resistance worldwide.” ![]()

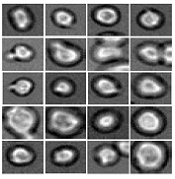

Software predicts HSPC differentiation

Deep learning can be used to determine how murine hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) will differentiate, according to research published in Nature Methods.

Deep learning algorithms simulate the learning processes in people using artificial neural networks.

Researchers have reported the development of software that uses deep learning to predict which type of cell murine HSPCs will differentiate into, based on microscopy images.

“A hematopoietic stem cell’s decision to become a certain cell type cannot be observed,” said study author Carsten Marr, PhD, of Helmholtz Zentrum München–German Research Center for Environmental Health in Neuherberg, Germany.

“At this time, it is only possible to verify the decision retrospectively with cell surface markers.”

Therefore, Dr Marr and his team set out to develop an algorithm that can predict the decision in advance, and deep learning was key.

“Deep neural networks play a major role in our method,” Dr Marr said. “Our algorithm classifies light microscopic images and videos of individual cells by comparing these data with past experience from the development of such cells. In this way, the algorithm ‘learns’ how certain cells behave.”

Specifically, the researchers examined murine HSPCs filmed under a microscope in the lab. Using information on the cells’ appearance and speed, the software was able to “memorize” the corresponding behavior patterns and then make its prediction.

“Compared to conventional methods, such as fluorescent antibodies against certain surface proteins, we know how the cells will decide 3 cell generations earlier,” said Felix Buggenthin, PhD, of Helmholtz Zentrum München–German Research Center for Environmental Health.

“Since we now know which cells will develop in which way, we can isolate them earlier than before and examine how they differ at a molecular level,” Dr Marr added. “We want to use this information to understand how the choices are made for particular developmental traits.” ![]()

Deep learning can be used to determine how murine hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) will differentiate, according to research published in Nature Methods.

Deep learning algorithms simulate the learning processes in people using artificial neural networks.

Researchers have reported the development of software that uses deep learning to predict which type of cell murine HSPCs will differentiate into, based on microscopy images.

“A hematopoietic stem cell’s decision to become a certain cell type cannot be observed,” said study author Carsten Marr, PhD, of Helmholtz Zentrum München–German Research Center for Environmental Health in Neuherberg, Germany.

“At this time, it is only possible to verify the decision retrospectively with cell surface markers.”

Therefore, Dr Marr and his team set out to develop an algorithm that can predict the decision in advance, and deep learning was key.

“Deep neural networks play a major role in our method,” Dr Marr said. “Our algorithm classifies light microscopic images and videos of individual cells by comparing these data with past experience from the development of such cells. In this way, the algorithm ‘learns’ how certain cells behave.”

Specifically, the researchers examined murine HSPCs filmed under a microscope in the lab. Using information on the cells’ appearance and speed, the software was able to “memorize” the corresponding behavior patterns and then make its prediction.

“Compared to conventional methods, such as fluorescent antibodies against certain surface proteins, we know how the cells will decide 3 cell generations earlier,” said Felix Buggenthin, PhD, of Helmholtz Zentrum München–German Research Center for Environmental Health.

“Since we now know which cells will develop in which way, we can isolate them earlier than before and examine how they differ at a molecular level,” Dr Marr added. “We want to use this information to understand how the choices are made for particular developmental traits.” ![]()

Deep learning can be used to determine how murine hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) will differentiate, according to research published in Nature Methods.

Deep learning algorithms simulate the learning processes in people using artificial neural networks.

Researchers have reported the development of software that uses deep learning to predict which type of cell murine HSPCs will differentiate into, based on microscopy images.

“A hematopoietic stem cell’s decision to become a certain cell type cannot be observed,” said study author Carsten Marr, PhD, of Helmholtz Zentrum München–German Research Center for Environmental Health in Neuherberg, Germany.

“At this time, it is only possible to verify the decision retrospectively with cell surface markers.”

Therefore, Dr Marr and his team set out to develop an algorithm that can predict the decision in advance, and deep learning was key.

“Deep neural networks play a major role in our method,” Dr Marr said. “Our algorithm classifies light microscopic images and videos of individual cells by comparing these data with past experience from the development of such cells. In this way, the algorithm ‘learns’ how certain cells behave.”

Specifically, the researchers examined murine HSPCs filmed under a microscope in the lab. Using information on the cells’ appearance and speed, the software was able to “memorize” the corresponding behavior patterns and then make its prediction.

“Compared to conventional methods, such as fluorescent antibodies against certain surface proteins, we know how the cells will decide 3 cell generations earlier,” said Felix Buggenthin, PhD, of Helmholtz Zentrum München–German Research Center for Environmental Health.

“Since we now know which cells will develop in which way, we can isolate them earlier than before and examine how they differ at a molecular level,” Dr Marr added. “We want to use this information to understand how the choices are made for particular developmental traits.”

How long Zika remains in body fluids

A study published in NEJM provides evidence that Zika virus RNA remain longer in blood and semen than in other body fluids, which suggests these may be superior diagnostic specimens.

This is the first study in which researchers examined multiple body fluids for the presence of Zika virus over a length of time.

The team sought to determine the frequency and duration of detectable Zika virus RNA in serum, saliva, urine, semen, and vaginal secretions.

They collected such specimens from 150 men and women in Puerto Rico who initially tested positive for Zika virus in urine or blood. The specimens were collected weekly for the first month and then at 2 months, 4 months, and 6 months.

The researchers tested all specimens using the Trioplex RT-PCR assay, a test that can be used to detect dengue, chikungunya, and Zika virus RNA. There have been allegations that this assay is less effective than a test used to detect Zika virus alone.

The researchers also performed validation analyses for the use of the Trioplex RT-PCR assay in semen. And they tested serum using the Zika IgM Antibody Capture Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (Zika MAC-ELISA).

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) developed both Zika MAC-ELISA and the Trioplex RT-PCR assay. This research was supported by the CDC.

After sample testing was complete, the researchers used parametric Weibull regression models to estimate the time to the loss of Zika virus RNA, which they reported in medians and 95th percentiles.

Results

The researchers said 88% of subjects (132/150) had detectable Zika virus RNA in at least 1 serum specimen. The median time to the loss of RNA detection in serum was 14 days (95% confidence interval [CI], 11 to 17), and the 95th percentile of time was 54 days (95% CI, 43 to 64).

The team also found that 61.7% of eligible subjects (92/149) had detectable Zika virus RNA in at least 1 urine specimen. The median time to the loss of RNA detection in urine was 8 days (95% CI, 6 to 10), and the 95th percentile of time was 39 days (95% CI, 31 to 47).

Fifteen subjects (10.1%) had detectable Zika virus RNA in urine but not serum, and 55 (36.7%) had RNA in serum but not urine.

Fifty-six percent of eligible male subjects (31/55) had Zika virus RNA in at least 1 semen specimen. The median time to loss of RNA detection in semen was 34 days (95% CI, 28 to 41), and the 95th percentile of time was 81 days (95% CI, 64 to 98).

The researchers noted that 11 of the 55 subjects had Zika virus RNA in their semen at their last visit and were still being followed at the time the NEJM article was written. The maximum duration of RNA detection was 125 days after the onset of symptoms.

Zika virus RNA levels were detectable in few saliva samples, with 10.2% of eligible subjects (15/147) having detectable levels in at least 1 saliva specimen.

Only 1 of 50 women (2%) had detectable Zika virus RNA in vaginal secretions.

“The findings of this study are important for both diagnostic and prevention purposes,” said study author Eli Rosenberg, PhD, of Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia.

“The results fully support current CDC sexual transmission recommendations but also provide critical information to help in understanding how often and how long evidence of Zika virus can be found in different body fluids. This knowledge is key to improving accuracy and effectiveness of testing methods while providing important baseline information for future research.”

A study published in NEJM provides evidence that Zika virus RNA remain longer in blood and semen than in other body fluids, which suggests these may be superior diagnostic specimens.

This is the first study in which researchers examined multiple body fluids for the presence of Zika virus over a length of time.

The team sought to determine the frequency and duration of detectable Zika virus RNA in serum, saliva, urine, semen, and vaginal secretions.

They collected such specimens from 150 men and women in Puerto Rico who initially tested positive for Zika virus in urine or blood. The specimens were collected weekly for the first month and then at 2 months, 4 months, and 6 months.

The researchers tested all specimens using the Trioplex RT-PCR assay, a test that can be used to detect dengue, chikungunya, and Zika virus RNA. There have been allegations that this assay is less effective than a test used to detect Zika virus alone.

The researchers also performed validation analyses for the use of the Trioplex RT-PCR assay in semen. And they tested serum using the Zika IgM Antibody Capture Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (Zika MAC-ELISA).

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) developed both Zika MAC-ELISA and the Trioplex RT-PCR assay. This research was supported by the CDC.

After sample testing was complete, the researchers used parametric Weibull regression models to estimate the time to the loss of Zika virus RNA, which they reported in medians and 95th percentiles.

Results

The researchers said 88% of subjects (132/150) had detectable Zika virus RNA in at least 1 serum specimen. The median time to the loss of RNA detection in serum was 14 days (95% confidence interval [CI], 11 to 17), and the 95th percentile of time was 54 days (95% CI, 43 to 64).

The team also found that 61.7% of eligible subjects (92/149) had detectable Zika virus RNA in at least 1 urine specimen. The median time to the loss of RNA detection in urine was 8 days (95% CI, 6 to 10), and the 95th percentile of time was 39 days (95% CI, 31 to 47).

Fifteen subjects (10.1%) had detectable Zika virus RNA in urine but not serum, and 55 (36.7%) had RNA in serum but not urine.

Fifty-six percent of eligible male subjects (31/55) had Zika virus RNA in at least 1 semen specimen. The median time to loss of RNA detection in semen was 34 days (95% CI, 28 to 41), and the 95th percentile of time was 81 days (95% CI, 64 to 98).

The researchers noted that 11 of the 55 subjects had Zika virus RNA in their semen at their last visit and were still being followed at the time the NEJM article was written. The maximum duration of RNA detection was 125 days after the onset of symptoms.

Zika virus RNA levels were detectable in few saliva samples, with 10.2% of eligible subjects (15/147) having detectable levels in at least 1 saliva specimen.

Only 1 of 50 women (2%) had detectable Zika virus RNA in vaginal secretions.

“The findings of this study are important for both diagnostic and prevention purposes,” said study author Eli Rosenberg, PhD, of Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia.

“The results fully support current CDC sexual transmission recommendations but also provide critical information to help in understanding how often and how long evidence of Zika virus can be found in different body fluids. This knowledge is key to improving accuracy and effectiveness of testing methods while providing important baseline information for future research.”

A study published in NEJM provides evidence that Zika virus RNA remain longer in blood and semen than in other body fluids, which suggests these may be superior diagnostic specimens.

This is the first study in which researchers examined multiple body fluids for the presence of Zika virus over a length of time.

The team sought to determine the frequency and duration of detectable Zika virus RNA in serum, saliva, urine, semen, and vaginal secretions.

They collected such specimens from 150 men and women in Puerto Rico who initially tested positive for Zika virus in urine or blood. The specimens were collected weekly for the first month and then at 2 months, 4 months, and 6 months.

The researchers tested all specimens using the Trioplex RT-PCR assay, a test that can be used to detect dengue, chikungunya, and Zika virus RNA. There have been allegations that this assay is less effective than a test used to detect Zika virus alone.

The researchers also performed validation analyses for the use of the Trioplex RT-PCR assay in semen. And they tested serum using the Zika IgM Antibody Capture Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (Zika MAC-ELISA).

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) developed both Zika MAC-ELISA and the Trioplex RT-PCR assay. This research was supported by the CDC.

After sample testing was complete, the researchers used parametric Weibull regression models to estimate the time to the loss of Zika virus RNA, which they reported in medians and 95th percentiles.

Results

The researchers said 88% of subjects (132/150) had detectable Zika virus RNA in at least 1 serum specimen. The median time to the loss of RNA detection in serum was 14 days (95% confidence interval [CI], 11 to 17), and the 95th percentile of time was 54 days (95% CI, 43 to 64).

The team also found that 61.7% of eligible subjects (92/149) had detectable Zika virus RNA in at least 1 urine specimen. The median time to the loss of RNA detection in urine was 8 days (95% CI, 6 to 10), and the 95th percentile of time was 39 days (95% CI, 31 to 47).

Fifteen subjects (10.1%) had detectable Zika virus RNA in urine but not serum, and 55 (36.7%) had RNA in serum but not urine.

Fifty-six percent of eligible male subjects (31/55) had Zika virus RNA in at least 1 semen specimen. The median time to loss of RNA detection in semen was 34 days (95% CI, 28 to 41), and the 95th percentile of time was 81 days (95% CI, 64 to 98).

The researchers noted that 11 of the 55 subjects had Zika virus RNA in their semen at their last visit and were still being followed at the time the NEJM article was written. The maximum duration of RNA detection was 125 days after the onset of symptoms.

Zika virus RNA levels were detectable in few saliva samples, with 10.2% of eligible subjects (15/147) having detectable levels in at least 1 saliva specimen.

Only 1 of 50 women (2%) had detectable Zika virus RNA in vaginal secretions.

“The findings of this study are important for both diagnostic and prevention purposes,” said study author Eli Rosenberg, PhD, of Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia.

“The results fully support current CDC sexual transmission recommendations but also provide critical information to help in understanding how often and how long evidence of Zika virus can be found in different body fluids. This knowledge is key to improving accuracy and effectiveness of testing methods while providing important baseline information for future research.”

Walking can benefit advanced cancer patients

Walking for 30 minutes 3 times a week can improve quality of life for patients with advanced cancer, according to research published in BMJ Open.

The study indicated that some patients with advanced cancer may not be able to commit to weekly walks with a group of fellow patients.

However, some patients enjoyed walking in groups, and most reported benefits from regular walks, whether taken alone or with others.

“Findings from this important study show that exercise is valued by, suitable for, and beneficial to people with advanced cancer,” said study author Emma Ream, RN, PhD, of the University of Surrey in the UK.

“Rather than shying away from exercise, people with advanced disease should be encouraged to be more active and incorporate exercise into their daily lives where possible.”

One hundred and ten patients with advanced cancer were eligible to participate in this study, but 49 (47%) declined, primarily because of work commitments. Patients said they could not commit to a weekly walking group.

The 42 patients who did participate in this study were divided into 2 groups.

Group 1 (n=21) received coaching, which included a short motivational interview, as well as the recommendation to walk for at least 30 minutes on alternate days and attend a volunteer-led group walk weekly.

Patients in group 2 (n=21) were encouraged to maintain their current level of activity.

Nineteen participants (45%) withdrew from the study—11 in group 1 and 8 in group 2. In general, patients did not provide reasons for withdrawal. However, 2 patients were too unwell to participate, and 2 patients died during the study.

At 6, 12, and 24 weeks, scores on quality of life questionnaires were not significantly different between groups 1 and 2.

However, in interviews, patients in group 1 said they felt walking provided physical, emotional, and psychological benefits, as well as improvements in social well-being and lifestyle.

At 24 weeks, 8 of 9 participants in group 1 said they found the walking intervention useful, and 7 participants said they were satisfied with it.

Some patients said walking improved their attitude toward their illness and spoke of the social benefits of participating in group walks.

But other patients were dissatisfied with the walking groups. They reported accessibility issues and a dislike of group activities. One younger individual felt the group was more appropriate for older patients.

“This study is a first step towards exploring how walking can help people living with advanced cancer,” said study author Jo Armes, RGN, PhD, of King’s College London in the UK.

“Walking is a free and accessible form of physical activity, and patients reported that it made a real difference to their quality of life. Further research is needed with a larger number of people to provide definitive evidence that walking improves both health outcomes and social and emotional wellbeing in this group of people.”

Walking for 30 minutes 3 times a week can improve quality of life for patients with advanced cancer, according to research published in BMJ Open.

The study indicated that some patients with advanced cancer may not be able to commit to weekly walks with a group of fellow patients.

However, some patients enjoyed walking in groups, and most reported benefits from regular walks, whether taken alone or with others.

“Findings from this important study show that exercise is valued by, suitable for, and beneficial to people with advanced cancer,” said study author Emma Ream, RN, PhD, of the University of Surrey in the UK.

“Rather than shying away from exercise, people with advanced disease should be encouraged to be more active and incorporate exercise into their daily lives where possible.”

One hundred and ten patients with advanced cancer were eligible to participate in this study, but 49 (47%) declined, primarily because of work commitments. Patients said they could not commit to a weekly walking group.

The 42 patients who did participate in this study were divided into 2 groups.

Group 1 (n=21) received coaching, which included a short motivational interview, as well as the recommendation to walk for at least 30 minutes on alternate days and attend a volunteer-led group walk weekly.

Patients in group 2 (n=21) were encouraged to maintain their current level of activity.

Nineteen participants (45%) withdrew from the study—11 in group 1 and 8 in group 2. In general, patients did not provide reasons for withdrawal. However, 2 patients were too unwell to participate, and 2 patients died during the study.

At 6, 12, and 24 weeks, scores on quality of life questionnaires were not significantly different between groups 1 and 2.

However, in interviews, patients in group 1 said they felt walking provided physical, emotional, and psychological benefits, as well as improvements in social well-being and lifestyle.

At 24 weeks, 8 of 9 participants in group 1 said they found the walking intervention useful, and 7 participants said they were satisfied with it.

Some patients said walking improved their attitude toward their illness and spoke of the social benefits of participating in group walks.

But other patients were dissatisfied with the walking groups. They reported accessibility issues and a dislike of group activities. One younger individual felt the group was more appropriate for older patients.

“This study is a first step towards exploring how walking can help people living with advanced cancer,” said study author Jo Armes, RGN, PhD, of King’s College London in the UK.

“Walking is a free and accessible form of physical activity, and patients reported that it made a real difference to their quality of life. Further research is needed with a larger number of people to provide definitive evidence that walking improves both health outcomes and social and emotional wellbeing in this group of people.”

Walking for 30 minutes 3 times a week can improve quality of life for patients with advanced cancer, according to research published in BMJ Open.

The study indicated that some patients with advanced cancer may not be able to commit to weekly walks with a group of fellow patients.

However, some patients enjoyed walking in groups, and most reported benefits from regular walks, whether taken alone or with others.

“Findings from this important study show that exercise is valued by, suitable for, and beneficial to people with advanced cancer,” said study author Emma Ream, RN, PhD, of the University of Surrey in the UK.

“Rather than shying away from exercise, people with advanced disease should be encouraged to be more active and incorporate exercise into their daily lives where possible.”

One hundred and ten patients with advanced cancer were eligible to participate in this study, but 49 (47%) declined, primarily because of work commitments. Patients said they could not commit to a weekly walking group.

The 42 patients who did participate in this study were divided into 2 groups.

Group 1 (n=21) received coaching, which included a short motivational interview, as well as the recommendation to walk for at least 30 minutes on alternate days and attend a volunteer-led group walk weekly.

Patients in group 2 (n=21) were encouraged to maintain their current level of activity.

Nineteen participants (45%) withdrew from the study—11 in group 1 and 8 in group 2. In general, patients did not provide reasons for withdrawal. However, 2 patients were too unwell to participate, and 2 patients died during the study.

At 6, 12, and 24 weeks, scores on quality of life questionnaires were not significantly different between groups 1 and 2.

However, in interviews, patients in group 1 said they felt walking provided physical, emotional, and psychological benefits, as well as improvements in social well-being and lifestyle.

At 24 weeks, 8 of 9 participants in group 1 said they found the walking intervention useful, and 7 participants said they were satisfied with it.

Some patients said walking improved their attitude toward their illness and spoke of the social benefits of participating in group walks.

But other patients were dissatisfied with the walking groups. They reported accessibility issues and a dislike of group activities. One younger individual felt the group was more appropriate for older patients.

“This study is a first step towards exploring how walking can help people living with advanced cancer,” said study author Jo Armes, RGN, PhD, of King’s College London in the UK.