User login

CPPD nomenclature is sore subject for gout group

LA JOLLA, CALIF. – Twelve years ago, an international task force of the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) released recommendations regarding nomenclature in calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease (CPPD), aiming to standardize the way the condition is described. “Pseudogout” was out, and “acute CPP crystal arthritis” was in, and a confusing array of multi-named phenotypes gained specific labels.

Since 2011, the nomenclature guidelines have been cited hundreds of times, but a new report finds that the medical literature mostly hasn’t followed the recommendations. The findings were released at the annual research symposium of the Gout, Hyperuricemia, and Crystal Associated Disease Network (G-CAN), which is taking another stab at overhauling CPPD nomenclature.

“The objective is to uniform and standardize the labels of the disease, the disease elements, and the clinical states,” rheumatologist Charlotte Jauffret, MD, of the Catholic University of Lille (France), said in a presentation. CPPD is a widely underdiagnosed disease that’s worth the same efforts to standardize nomenclature as occurred in gout, she said.

As Dr. Jauffret explained, CPPD has a diversity of phenotypes in asymptomatic, acute, and chronic forms that pose challenges to diagnosis. “The same terms are used to depict different concepts, and some disease elements are depicted through different names,” she said.

Among other suggestions, the 2011 EULAR recommendations suggested that rheumatologists use the terms chronic CPP crystal inflammatory arthritis instead of “pseudo-rheumatoid arthritis,” osteoarthritis with CPPD, instead of “pseudo-osteoarthritis,” and severe joint degeneration instead of “pseudo-neuropathic joint disease.”

Later reports noted that terms such as CPPD and chondrocalcinosis are still wrongly used interchangeably and called for an international consensus on nomenclature, Dr. Jauffret said.

For the new report, Dr. Jauffret and colleagues examined 985 articles from 2000-2022. The guidelines were often not followed even after the release of the recommendations.

For example, 49% of relevant papers used the label “pseudogout” before 2011, and 43% did afterward. A total of 34% of relevant papers described CPPD as chondrocalcinosis prior to 2011, and 22% did afterward.

G-CAN’s next steps are to reach consensus on terminology through online and in-person meetings in 2024, Dr. Jauffret said.

Use of correct gout nomenclature labels improved

In a related presentation, rheumatologist Ellen Prendergast, MBChB, of Dunedin Hospital in New Zealand, reported the results of a newly published review of gout studies before and after G-CAN released consensus recommendations for gout nomenclature in 2019. “There has been improvement in the agreed labels in some areas, but there remains quite significant variability,” she said.

The review examined American College of Rheumatology and EULAR annual meeting abstracts: 596 from 2016-2017 and 392 from 2020-2021. Dr. Prendergast said researchers focused on abstracts instead of published studies in order to gain the most up-to-date understanding of nomenclature.

“Use of the agreed labels ‘urate’ and ‘gout flare’ increased between the two periods. There were 219 of 383 (57.2%) abstracts with the agreed label ‘urate’ in 2016-2017, compared with 164 of 232 (70.7%) in 2020-2021 (P = .001),” the researchers reported. “There were 60 of 175 (34.3%) abstracts with the agreed label ‘gout flare’ in 2016-2017, compared with 57 of 109 (52.3%) in 2020-2021 (P = .003).”

And the use of the term “chronic gout,” which the guidelines recommend against, fell from 29 of 596 (4.9%) abstracts in 2016-2017 to 8 of 392 (2.0%) abstracts in 2020-2021 (P = .02).

One author of the gout nomenclature study reports various consulting fees, speaker fees, or grants outside the submitted work. The other authors of the two studies report no disclosures.

LA JOLLA, CALIF. – Twelve years ago, an international task force of the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) released recommendations regarding nomenclature in calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease (CPPD), aiming to standardize the way the condition is described. “Pseudogout” was out, and “acute CPP crystal arthritis” was in, and a confusing array of multi-named phenotypes gained specific labels.

Since 2011, the nomenclature guidelines have been cited hundreds of times, but a new report finds that the medical literature mostly hasn’t followed the recommendations. The findings were released at the annual research symposium of the Gout, Hyperuricemia, and Crystal Associated Disease Network (G-CAN), which is taking another stab at overhauling CPPD nomenclature.

“The objective is to uniform and standardize the labels of the disease, the disease elements, and the clinical states,” rheumatologist Charlotte Jauffret, MD, of the Catholic University of Lille (France), said in a presentation. CPPD is a widely underdiagnosed disease that’s worth the same efforts to standardize nomenclature as occurred in gout, she said.

As Dr. Jauffret explained, CPPD has a diversity of phenotypes in asymptomatic, acute, and chronic forms that pose challenges to diagnosis. “The same terms are used to depict different concepts, and some disease elements are depicted through different names,” she said.

Among other suggestions, the 2011 EULAR recommendations suggested that rheumatologists use the terms chronic CPP crystal inflammatory arthritis instead of “pseudo-rheumatoid arthritis,” osteoarthritis with CPPD, instead of “pseudo-osteoarthritis,” and severe joint degeneration instead of “pseudo-neuropathic joint disease.”

Later reports noted that terms such as CPPD and chondrocalcinosis are still wrongly used interchangeably and called for an international consensus on nomenclature, Dr. Jauffret said.

For the new report, Dr. Jauffret and colleagues examined 985 articles from 2000-2022. The guidelines were often not followed even after the release of the recommendations.

For example, 49% of relevant papers used the label “pseudogout” before 2011, and 43% did afterward. A total of 34% of relevant papers described CPPD as chondrocalcinosis prior to 2011, and 22% did afterward.

G-CAN’s next steps are to reach consensus on terminology through online and in-person meetings in 2024, Dr. Jauffret said.

Use of correct gout nomenclature labels improved

In a related presentation, rheumatologist Ellen Prendergast, MBChB, of Dunedin Hospital in New Zealand, reported the results of a newly published review of gout studies before and after G-CAN released consensus recommendations for gout nomenclature in 2019. “There has been improvement in the agreed labels in some areas, but there remains quite significant variability,” she said.

The review examined American College of Rheumatology and EULAR annual meeting abstracts: 596 from 2016-2017 and 392 from 2020-2021. Dr. Prendergast said researchers focused on abstracts instead of published studies in order to gain the most up-to-date understanding of nomenclature.

“Use of the agreed labels ‘urate’ and ‘gout flare’ increased between the two periods. There were 219 of 383 (57.2%) abstracts with the agreed label ‘urate’ in 2016-2017, compared with 164 of 232 (70.7%) in 2020-2021 (P = .001),” the researchers reported. “There were 60 of 175 (34.3%) abstracts with the agreed label ‘gout flare’ in 2016-2017, compared with 57 of 109 (52.3%) in 2020-2021 (P = .003).”

And the use of the term “chronic gout,” which the guidelines recommend against, fell from 29 of 596 (4.9%) abstracts in 2016-2017 to 8 of 392 (2.0%) abstracts in 2020-2021 (P = .02).

One author of the gout nomenclature study reports various consulting fees, speaker fees, or grants outside the submitted work. The other authors of the two studies report no disclosures.

LA JOLLA, CALIF. – Twelve years ago, an international task force of the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) released recommendations regarding nomenclature in calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease (CPPD), aiming to standardize the way the condition is described. “Pseudogout” was out, and “acute CPP crystal arthritis” was in, and a confusing array of multi-named phenotypes gained specific labels.

Since 2011, the nomenclature guidelines have been cited hundreds of times, but a new report finds that the medical literature mostly hasn’t followed the recommendations. The findings were released at the annual research symposium of the Gout, Hyperuricemia, and Crystal Associated Disease Network (G-CAN), which is taking another stab at overhauling CPPD nomenclature.

“The objective is to uniform and standardize the labels of the disease, the disease elements, and the clinical states,” rheumatologist Charlotte Jauffret, MD, of the Catholic University of Lille (France), said in a presentation. CPPD is a widely underdiagnosed disease that’s worth the same efforts to standardize nomenclature as occurred in gout, she said.

As Dr. Jauffret explained, CPPD has a diversity of phenotypes in asymptomatic, acute, and chronic forms that pose challenges to diagnosis. “The same terms are used to depict different concepts, and some disease elements are depicted through different names,” she said.

Among other suggestions, the 2011 EULAR recommendations suggested that rheumatologists use the terms chronic CPP crystal inflammatory arthritis instead of “pseudo-rheumatoid arthritis,” osteoarthritis with CPPD, instead of “pseudo-osteoarthritis,” and severe joint degeneration instead of “pseudo-neuropathic joint disease.”

Later reports noted that terms such as CPPD and chondrocalcinosis are still wrongly used interchangeably and called for an international consensus on nomenclature, Dr. Jauffret said.

For the new report, Dr. Jauffret and colleagues examined 985 articles from 2000-2022. The guidelines were often not followed even after the release of the recommendations.

For example, 49% of relevant papers used the label “pseudogout” before 2011, and 43% did afterward. A total of 34% of relevant papers described CPPD as chondrocalcinosis prior to 2011, and 22% did afterward.

G-CAN’s next steps are to reach consensus on terminology through online and in-person meetings in 2024, Dr. Jauffret said.

Use of correct gout nomenclature labels improved

In a related presentation, rheumatologist Ellen Prendergast, MBChB, of Dunedin Hospital in New Zealand, reported the results of a newly published review of gout studies before and after G-CAN released consensus recommendations for gout nomenclature in 2019. “There has been improvement in the agreed labels in some areas, but there remains quite significant variability,” she said.

The review examined American College of Rheumatology and EULAR annual meeting abstracts: 596 from 2016-2017 and 392 from 2020-2021. Dr. Prendergast said researchers focused on abstracts instead of published studies in order to gain the most up-to-date understanding of nomenclature.

“Use of the agreed labels ‘urate’ and ‘gout flare’ increased between the two periods. There were 219 of 383 (57.2%) abstracts with the agreed label ‘urate’ in 2016-2017, compared with 164 of 232 (70.7%) in 2020-2021 (P = .001),” the researchers reported. “There were 60 of 175 (34.3%) abstracts with the agreed label ‘gout flare’ in 2016-2017, compared with 57 of 109 (52.3%) in 2020-2021 (P = .003).”

And the use of the term “chronic gout,” which the guidelines recommend against, fell from 29 of 596 (4.9%) abstracts in 2016-2017 to 8 of 392 (2.0%) abstracts in 2020-2021 (P = .02).

One author of the gout nomenclature study reports various consulting fees, speaker fees, or grants outside the submitted work. The other authors of the two studies report no disclosures.

At G-CAN 2023

55-year-old woman • myalgias and progressive symmetrical proximal weakness • history of type 2 diabetes and hyperlipidemia • Dx?

THE CASE

A 55-year-old woman developed subacute progression of myalgias and subjective weakness in her proximal extremities after starting a new exercise regimen. The patient had a history of unilateral renal agenesis, type 2 diabetes, and hyperlipidemia, for which she had taken atorvastatin 40 mg/d for several years before discontinuing it 2 years earlier for unknown reasons. She had been evaluated multiple times in the primary care clinic and emergency department over the previous month. Each time, her strength was minimally reduced in the upper extremities on examination, her renal function and electrolytes were normal, and her creatine kinase (CK) level was elevated (16,000-20,000 U/L; normal range, 26-192 U/L). She was managed conservatively with fluids and given return precautions each time.

After her myalgias and weakness increased in severity, she presented to the emergency department with a muscle strength score of 4/5 in both shoulders, triceps, hip flexors, hip extensors, abductors, and adductors. Her laboratory results were significant for the presence of blood without red blood cells on her urine dipstick test and a CK level of 25,070 U/L. She was admitted for further evaluation of progressive myopathy and given aggressive IV fluid hydration to prevent renal injury based on her history of unilateral renal agenesis.

Infectious disease testing, which included a respiratory virus panel, acute hepatitis panel, HIV screening, Lyme antibody testing, cytomegalovirus DNA detection by polymerase chain reaction, Epstein-Barr virus capsid immunoglobulin M, and anti-streptolysin O, were negative. Electrolytes, inflammatory markers, and kidney function were normal. However, high-sensitivity troponin-T levels were elevated, with a peak value of 216.3 ng/L (normal range, 0-19 ng/L). The patient denied having any chest pain, and her electrocardiogram and transthoracic echocardiogram were normal. By hospital Day 4, her myalgias and weakness had improved, CK had stabilized (19,000-21,000 U/L), cardiac enzymes had improved, and urinalysis had normalized. She was discharged with a referral to a rheumatologist.

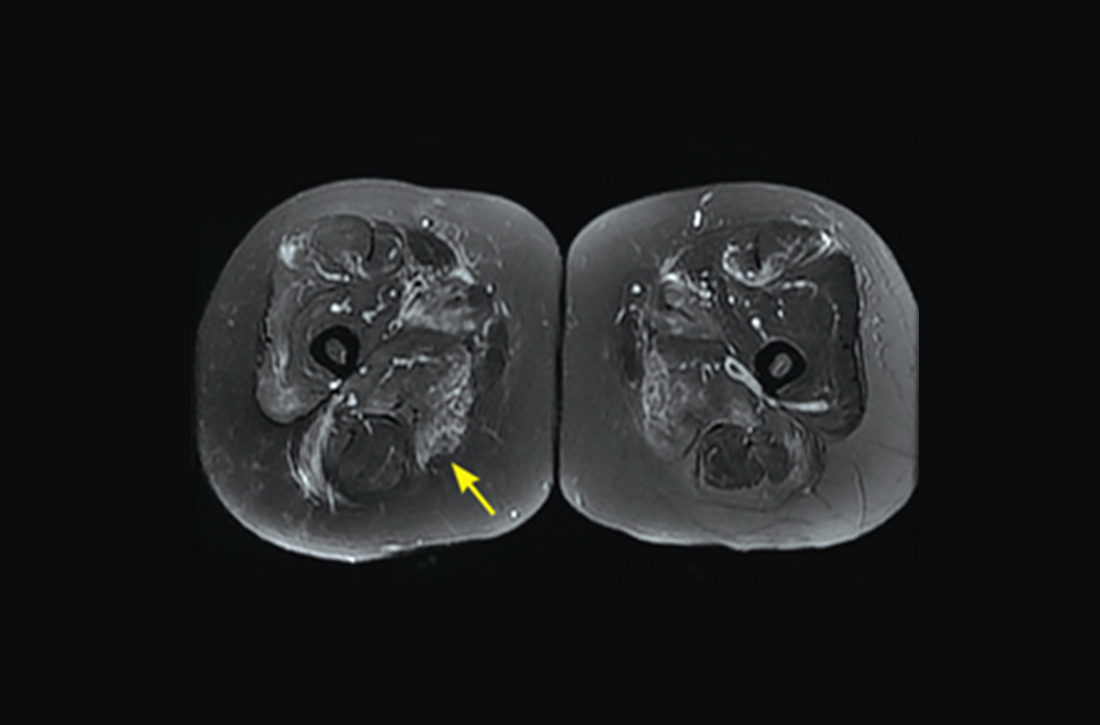

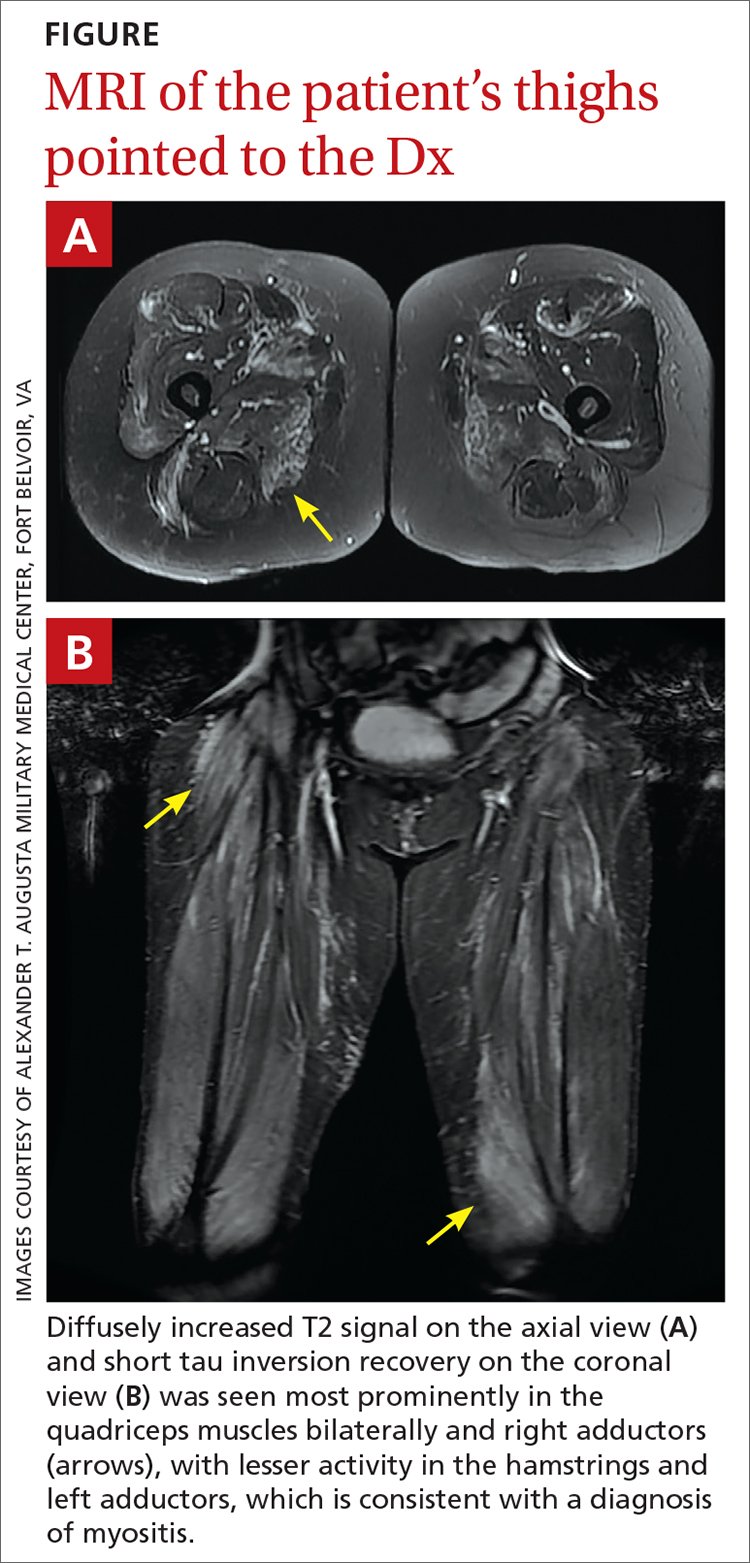

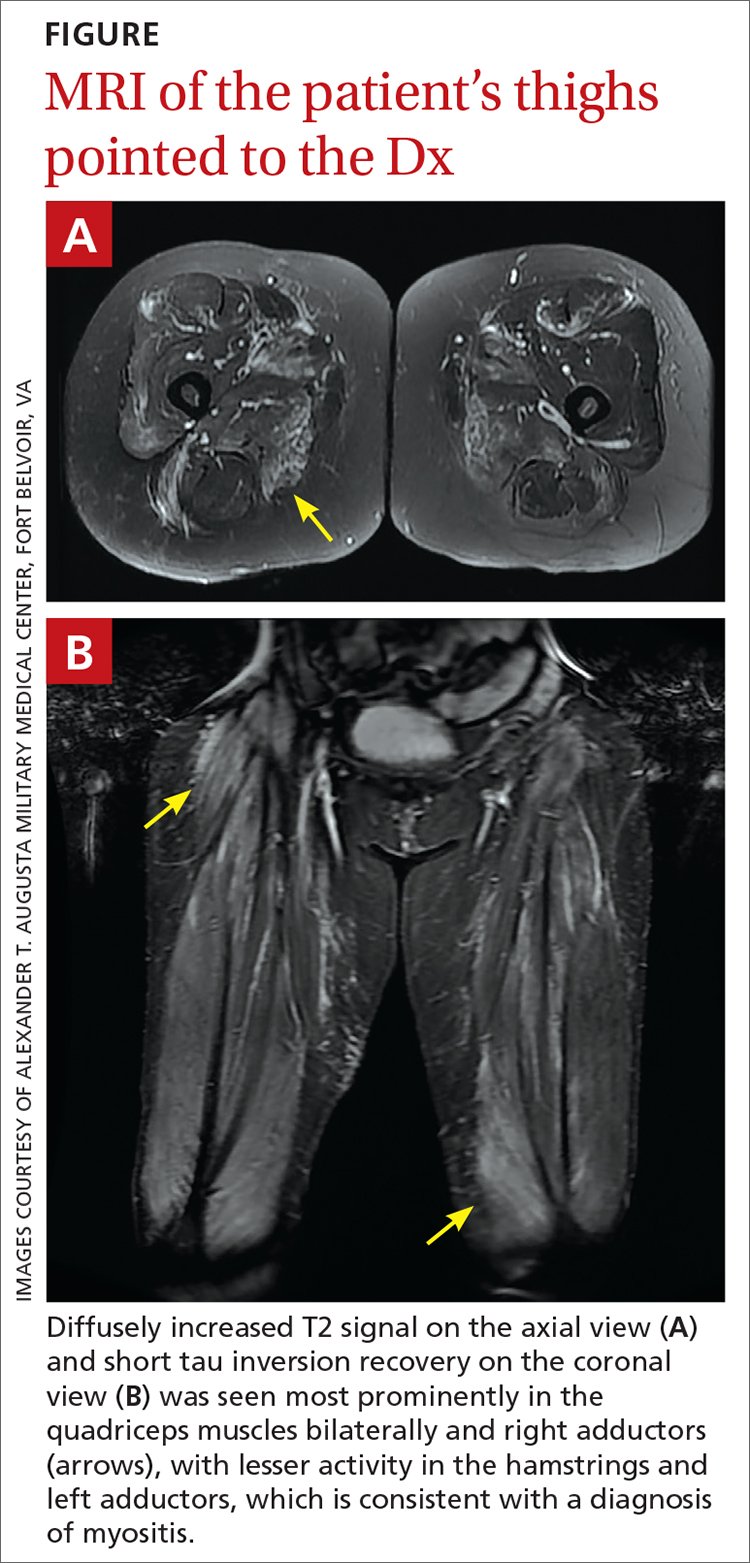

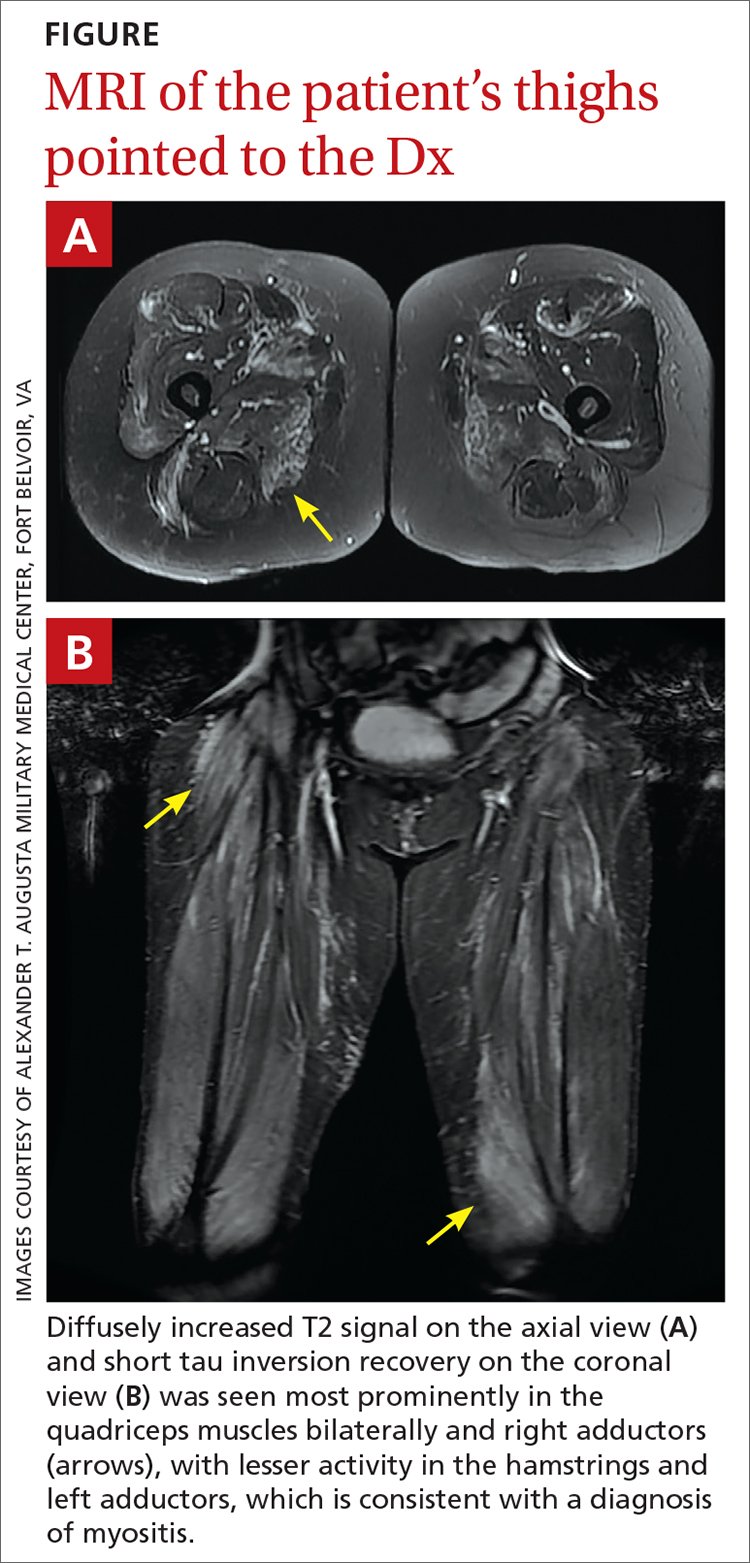

However, 10 days later—before she could see a rheumatologist—she was readmitted to a community hospital for recurrence of severe myalgias, progressive weakness, positive blood on urine dipstick testing, and a rising CK level (to 24,580 U/L) found during a follow-up appointment with her primary care physician. At this point, Neurology and Rheumatology were consulted and myositis-specific and myositis-associated autoantibody tests were sent out. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of her thighs was performed and showed diffusely increased T2 signal and short tau inversion recovery in multiple proximal muscles (FIGURE).

DIAGNOSIS

Given her symmetrical proximal muscle weakness (which was refractory to IV fluid resuscitation), MRI findings, and the exclusion of infection and metabolic derangements, the patient was given a working diagnosis of myositis and treated with 1-g IV methylprednisolone followed by a 4-month steroid taper, methotrexate 20 mg weekly, and physical therapy. This working diagnosis was later confirmed with the results of her autoantibody tests.

At her 1-month follow-up visit, the patient reported minimal improvement in her strength, new neck weakness, and dysphagia with solids. Testing revealed anti–3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (anti-HMGCR) antibody levels of more than 200 U/L (negative < 20 U/L; positive > 59 U/L), which pointed to a more refined diagnosis of anti-HMGCR immune-mediated necrotizing myositis.

DISCUSSION

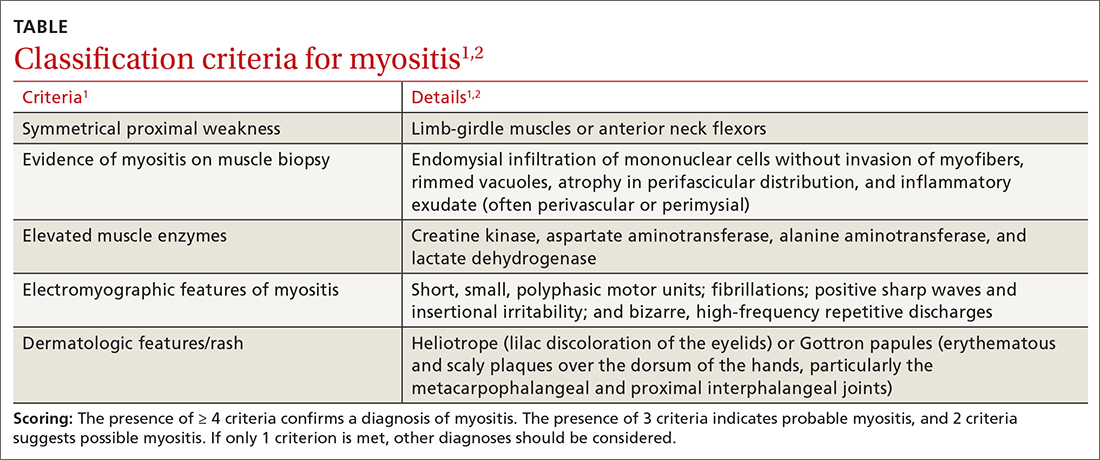

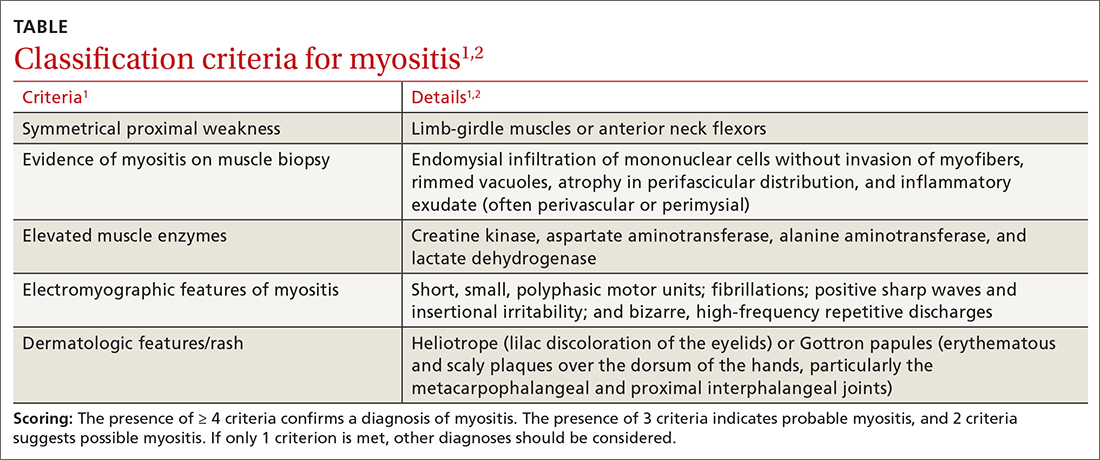

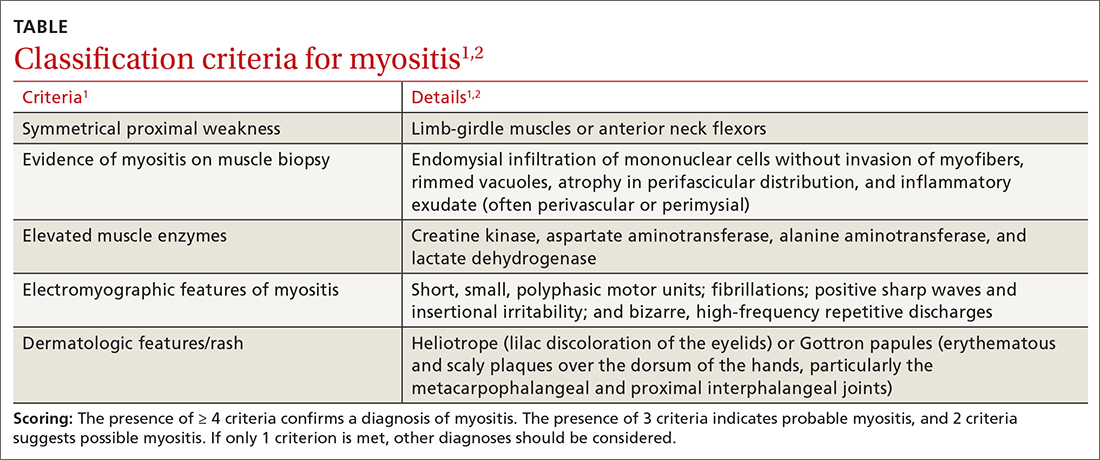

Myositis should be in the differential diagnosis for patients with symmetrical proximal muscle weakness. Bohan and Peter devised a 5-part set of criteria to help diagnose myositis, shown in the TABLE.1,2 This simple framework broadens the differential and guides diagnostic testing. Our patient’s presentation was fairly typical for anti-HMGCR myositis, a subset of immune-mediated necrotizing myositis,3 with a pretest probability of 62% per the European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria.2 Probability of this diagnosis was further increased by the high-titer anti-HMGCR, so biopsy and electromyography (EMG), as noted by Bohan and Peter, were not pursued.

Continue to: Autoimmune myopathies...

Autoimmune myopathies occur in 9 to 14 per 100,000 people,4 with 6% of patients having anti-HMGCR auto-antibodies.5 Anti-HMGCR myositis is more prevalent in older women, patients with type 2 diabetes, and those with a history of atorvastatin use.3,6 Two-thirds of patients with anti-HMGCR myositis report current or prior statin use, and this increases to more than 90% in those age 50 years or older.5 Anti-HMGCR myositis causes significant muscle weakness that does not resolve with discontinuation of the statin and can occur years after the initiation or discontinuation of statin treatment.6 Cardiac involvement is rare4 but dysphagia is relatively common.7,8 Anti-HMGCR myositis also has a weak association with cancer, most commonly gastrointestinal and lung cancers.4,7

Distinguishing statin-induced myalgias from statin-induced myositis guides management. Statin-induced myalgias are associated with normal or slightly increased CK levels (typically < 1000 U/L) and resolve with discontinuation of the statin; the patient can often tolerate re-challenge with a statin.6 In contrast, CK elevation in patients with statin-induced myositis is typically more than 10,000 U/L6 and requires aggressive treatment with immunomodulatory medications to prevent permanent muscle damage.

Treatment recommendations are supported only by case series, observational studies, and expert opinion. Typical first-line treatment includes induction with high-dose corticosteroids followed by prolonged taper plus a conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (csDMARD) such as methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate.4 Maintenance therapy often is achieved with csDMARD therapy for 2 years.4 Severe cases frequently are treated with combination csDMARD therapy (eg, methotrexate and azathioprine or methotrexate and mycophenolate).4 Rituximab and IV immunoglobulin (IVIG) are typically reserved for refractory cases.6 Usual monitoring for relapse includes muscle strength testing on examination and evaluation of trending CK levels.8

Our patient received monthly 2-g/kg IVIG infusions, which led to slow, consistent improvement in her strength and normalization of her CK levels to 181 U/L after 6 months.

THE TAKEAWAY

Anti-HMGCR myositis should be suspected in any patient currently or previously treated with a statin who presents with proximal muscle weakness, myalgias, or an elevated CK level. We suggest early subspecialty consultation to discuss whether antibody testing, EMG, or muscle biopsy are warranted. If anti-HMGCR myositis is confirmed, it is advisable to rule out comorbid malignancy and initiate early combination treatment to minimize relapses and permanent muscle damage.

CORRESPONDENCE

Daniel T. Schoenherr, MD, Family Medicine Residency, National Capital Consortium–Alexander T. Augusta Military Medical Center, 9300 DeWitt Loop, Fort Belvoir, VA 22060; [email protected]

1. Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1975;292:344-347. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197502132920706

2. Bottai M, Tjärnlund A, Santoni G, et al. EULAR/ACR classification criteria for adult and juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and their major subgroups: a methodology report. RMD Open. 2017;3:e000507. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000507

3. Basharat P, Lahouti AH, Paik JJ, et al. Statin-induced anti-HMGCR-associated myopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:234-235. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.04.037

4. Pinal-Fernandez I, Casal-Dominguez M, Mammen AL. Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2018;20:21. doi: 10.1007/s11926-018-0732-6

5. Mammen AL, Chung T, Christopher-Stine L, et al. Autoantibodies against 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase in patients with statin-associated autoimmune myopathy. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:713-721. doi: 10.1002/art.30156

6. Irvine NJ. Anti-HMGCR myopathy: a rare and serious side effect of statins. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33:785-788. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2020.05.190450

7. Basharat P, Christopher-Stine L. Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy: update on diagnosis and management. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17:72. doi: 10.1007/s11926-015-0548-6

8. Betteridge Z, McHugh N. Myositis-specific autoantibodies: an important tool to support diagnosis of myositis. J Int Med. 2016;280:8-23. doi: 10.1111/joim.12451

THE CASE

A 55-year-old woman developed subacute progression of myalgias and subjective weakness in her proximal extremities after starting a new exercise regimen. The patient had a history of unilateral renal agenesis, type 2 diabetes, and hyperlipidemia, for which she had taken atorvastatin 40 mg/d for several years before discontinuing it 2 years earlier for unknown reasons. She had been evaluated multiple times in the primary care clinic and emergency department over the previous month. Each time, her strength was minimally reduced in the upper extremities on examination, her renal function and electrolytes were normal, and her creatine kinase (CK) level was elevated (16,000-20,000 U/L; normal range, 26-192 U/L). She was managed conservatively with fluids and given return precautions each time.

After her myalgias and weakness increased in severity, she presented to the emergency department with a muscle strength score of 4/5 in both shoulders, triceps, hip flexors, hip extensors, abductors, and adductors. Her laboratory results were significant for the presence of blood without red blood cells on her urine dipstick test and a CK level of 25,070 U/L. She was admitted for further evaluation of progressive myopathy and given aggressive IV fluid hydration to prevent renal injury based on her history of unilateral renal agenesis.

Infectious disease testing, which included a respiratory virus panel, acute hepatitis panel, HIV screening, Lyme antibody testing, cytomegalovirus DNA detection by polymerase chain reaction, Epstein-Barr virus capsid immunoglobulin M, and anti-streptolysin O, were negative. Electrolytes, inflammatory markers, and kidney function were normal. However, high-sensitivity troponin-T levels were elevated, with a peak value of 216.3 ng/L (normal range, 0-19 ng/L). The patient denied having any chest pain, and her electrocardiogram and transthoracic echocardiogram were normal. By hospital Day 4, her myalgias and weakness had improved, CK had stabilized (19,000-21,000 U/L), cardiac enzymes had improved, and urinalysis had normalized. She was discharged with a referral to a rheumatologist.

However, 10 days later—before she could see a rheumatologist—she was readmitted to a community hospital for recurrence of severe myalgias, progressive weakness, positive blood on urine dipstick testing, and a rising CK level (to 24,580 U/L) found during a follow-up appointment with her primary care physician. At this point, Neurology and Rheumatology were consulted and myositis-specific and myositis-associated autoantibody tests were sent out. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of her thighs was performed and showed diffusely increased T2 signal and short tau inversion recovery in multiple proximal muscles (FIGURE).

DIAGNOSIS

Given her symmetrical proximal muscle weakness (which was refractory to IV fluid resuscitation), MRI findings, and the exclusion of infection and metabolic derangements, the patient was given a working diagnosis of myositis and treated with 1-g IV methylprednisolone followed by a 4-month steroid taper, methotrexate 20 mg weekly, and physical therapy. This working diagnosis was later confirmed with the results of her autoantibody tests.

At her 1-month follow-up visit, the patient reported minimal improvement in her strength, new neck weakness, and dysphagia with solids. Testing revealed anti–3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (anti-HMGCR) antibody levels of more than 200 U/L (negative < 20 U/L; positive > 59 U/L), which pointed to a more refined diagnosis of anti-HMGCR immune-mediated necrotizing myositis.

DISCUSSION

Myositis should be in the differential diagnosis for patients with symmetrical proximal muscle weakness. Bohan and Peter devised a 5-part set of criteria to help diagnose myositis, shown in the TABLE.1,2 This simple framework broadens the differential and guides diagnostic testing. Our patient’s presentation was fairly typical for anti-HMGCR myositis, a subset of immune-mediated necrotizing myositis,3 with a pretest probability of 62% per the European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria.2 Probability of this diagnosis was further increased by the high-titer anti-HMGCR, so biopsy and electromyography (EMG), as noted by Bohan and Peter, were not pursued.

Continue to: Autoimmune myopathies...

Autoimmune myopathies occur in 9 to 14 per 100,000 people,4 with 6% of patients having anti-HMGCR auto-antibodies.5 Anti-HMGCR myositis is more prevalent in older women, patients with type 2 diabetes, and those with a history of atorvastatin use.3,6 Two-thirds of patients with anti-HMGCR myositis report current or prior statin use, and this increases to more than 90% in those age 50 years or older.5 Anti-HMGCR myositis causes significant muscle weakness that does not resolve with discontinuation of the statin and can occur years after the initiation or discontinuation of statin treatment.6 Cardiac involvement is rare4 but dysphagia is relatively common.7,8 Anti-HMGCR myositis also has a weak association with cancer, most commonly gastrointestinal and lung cancers.4,7

Distinguishing statin-induced myalgias from statin-induced myositis guides management. Statin-induced myalgias are associated with normal or slightly increased CK levels (typically < 1000 U/L) and resolve with discontinuation of the statin; the patient can often tolerate re-challenge with a statin.6 In contrast, CK elevation in patients with statin-induced myositis is typically more than 10,000 U/L6 and requires aggressive treatment with immunomodulatory medications to prevent permanent muscle damage.

Treatment recommendations are supported only by case series, observational studies, and expert opinion. Typical first-line treatment includes induction with high-dose corticosteroids followed by prolonged taper plus a conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (csDMARD) such as methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate.4 Maintenance therapy often is achieved with csDMARD therapy for 2 years.4 Severe cases frequently are treated with combination csDMARD therapy (eg, methotrexate and azathioprine or methotrexate and mycophenolate).4 Rituximab and IV immunoglobulin (IVIG) are typically reserved for refractory cases.6 Usual monitoring for relapse includes muscle strength testing on examination and evaluation of trending CK levels.8

Our patient received monthly 2-g/kg IVIG infusions, which led to slow, consistent improvement in her strength and normalization of her CK levels to 181 U/L after 6 months.

THE TAKEAWAY

Anti-HMGCR myositis should be suspected in any patient currently or previously treated with a statin who presents with proximal muscle weakness, myalgias, or an elevated CK level. We suggest early subspecialty consultation to discuss whether antibody testing, EMG, or muscle biopsy are warranted. If anti-HMGCR myositis is confirmed, it is advisable to rule out comorbid malignancy and initiate early combination treatment to minimize relapses and permanent muscle damage.

CORRESPONDENCE

Daniel T. Schoenherr, MD, Family Medicine Residency, National Capital Consortium–Alexander T. Augusta Military Medical Center, 9300 DeWitt Loop, Fort Belvoir, VA 22060; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 55-year-old woman developed subacute progression of myalgias and subjective weakness in her proximal extremities after starting a new exercise regimen. The patient had a history of unilateral renal agenesis, type 2 diabetes, and hyperlipidemia, for which she had taken atorvastatin 40 mg/d for several years before discontinuing it 2 years earlier for unknown reasons. She had been evaluated multiple times in the primary care clinic and emergency department over the previous month. Each time, her strength was minimally reduced in the upper extremities on examination, her renal function and electrolytes were normal, and her creatine kinase (CK) level was elevated (16,000-20,000 U/L; normal range, 26-192 U/L). She was managed conservatively with fluids and given return precautions each time.

After her myalgias and weakness increased in severity, she presented to the emergency department with a muscle strength score of 4/5 in both shoulders, triceps, hip flexors, hip extensors, abductors, and adductors. Her laboratory results were significant for the presence of blood without red blood cells on her urine dipstick test and a CK level of 25,070 U/L. She was admitted for further evaluation of progressive myopathy and given aggressive IV fluid hydration to prevent renal injury based on her history of unilateral renal agenesis.

Infectious disease testing, which included a respiratory virus panel, acute hepatitis panel, HIV screening, Lyme antibody testing, cytomegalovirus DNA detection by polymerase chain reaction, Epstein-Barr virus capsid immunoglobulin M, and anti-streptolysin O, were negative. Electrolytes, inflammatory markers, and kidney function were normal. However, high-sensitivity troponin-T levels were elevated, with a peak value of 216.3 ng/L (normal range, 0-19 ng/L). The patient denied having any chest pain, and her electrocardiogram and transthoracic echocardiogram were normal. By hospital Day 4, her myalgias and weakness had improved, CK had stabilized (19,000-21,000 U/L), cardiac enzymes had improved, and urinalysis had normalized. She was discharged with a referral to a rheumatologist.

However, 10 days later—before she could see a rheumatologist—she was readmitted to a community hospital for recurrence of severe myalgias, progressive weakness, positive blood on urine dipstick testing, and a rising CK level (to 24,580 U/L) found during a follow-up appointment with her primary care physician. At this point, Neurology and Rheumatology were consulted and myositis-specific and myositis-associated autoantibody tests were sent out. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of her thighs was performed and showed diffusely increased T2 signal and short tau inversion recovery in multiple proximal muscles (FIGURE).

DIAGNOSIS

Given her symmetrical proximal muscle weakness (which was refractory to IV fluid resuscitation), MRI findings, and the exclusion of infection and metabolic derangements, the patient was given a working diagnosis of myositis and treated with 1-g IV methylprednisolone followed by a 4-month steroid taper, methotrexate 20 mg weekly, and physical therapy. This working diagnosis was later confirmed with the results of her autoantibody tests.

At her 1-month follow-up visit, the patient reported minimal improvement in her strength, new neck weakness, and dysphagia with solids. Testing revealed anti–3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (anti-HMGCR) antibody levels of more than 200 U/L (negative < 20 U/L; positive > 59 U/L), which pointed to a more refined diagnosis of anti-HMGCR immune-mediated necrotizing myositis.

DISCUSSION

Myositis should be in the differential diagnosis for patients with symmetrical proximal muscle weakness. Bohan and Peter devised a 5-part set of criteria to help diagnose myositis, shown in the TABLE.1,2 This simple framework broadens the differential and guides diagnostic testing. Our patient’s presentation was fairly typical for anti-HMGCR myositis, a subset of immune-mediated necrotizing myositis,3 with a pretest probability of 62% per the European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria.2 Probability of this diagnosis was further increased by the high-titer anti-HMGCR, so biopsy and electromyography (EMG), as noted by Bohan and Peter, were not pursued.

Continue to: Autoimmune myopathies...

Autoimmune myopathies occur in 9 to 14 per 100,000 people,4 with 6% of patients having anti-HMGCR auto-antibodies.5 Anti-HMGCR myositis is more prevalent in older women, patients with type 2 diabetes, and those with a history of atorvastatin use.3,6 Two-thirds of patients with anti-HMGCR myositis report current or prior statin use, and this increases to more than 90% in those age 50 years or older.5 Anti-HMGCR myositis causes significant muscle weakness that does not resolve with discontinuation of the statin and can occur years after the initiation or discontinuation of statin treatment.6 Cardiac involvement is rare4 but dysphagia is relatively common.7,8 Anti-HMGCR myositis also has a weak association with cancer, most commonly gastrointestinal and lung cancers.4,7

Distinguishing statin-induced myalgias from statin-induced myositis guides management. Statin-induced myalgias are associated with normal or slightly increased CK levels (typically < 1000 U/L) and resolve with discontinuation of the statin; the patient can often tolerate re-challenge with a statin.6 In contrast, CK elevation in patients with statin-induced myositis is typically more than 10,000 U/L6 and requires aggressive treatment with immunomodulatory medications to prevent permanent muscle damage.

Treatment recommendations are supported only by case series, observational studies, and expert opinion. Typical first-line treatment includes induction with high-dose corticosteroids followed by prolonged taper plus a conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (csDMARD) such as methotrexate, azathioprine, or mycophenolate.4 Maintenance therapy often is achieved with csDMARD therapy for 2 years.4 Severe cases frequently are treated with combination csDMARD therapy (eg, methotrexate and azathioprine or methotrexate and mycophenolate).4 Rituximab and IV immunoglobulin (IVIG) are typically reserved for refractory cases.6 Usual monitoring for relapse includes muscle strength testing on examination and evaluation of trending CK levels.8

Our patient received monthly 2-g/kg IVIG infusions, which led to slow, consistent improvement in her strength and normalization of her CK levels to 181 U/L after 6 months.

THE TAKEAWAY

Anti-HMGCR myositis should be suspected in any patient currently or previously treated with a statin who presents with proximal muscle weakness, myalgias, or an elevated CK level. We suggest early subspecialty consultation to discuss whether antibody testing, EMG, or muscle biopsy are warranted. If anti-HMGCR myositis is confirmed, it is advisable to rule out comorbid malignancy and initiate early combination treatment to minimize relapses and permanent muscle damage.

CORRESPONDENCE

Daniel T. Schoenherr, MD, Family Medicine Residency, National Capital Consortium–Alexander T. Augusta Military Medical Center, 9300 DeWitt Loop, Fort Belvoir, VA 22060; [email protected]

1. Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1975;292:344-347. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197502132920706

2. Bottai M, Tjärnlund A, Santoni G, et al. EULAR/ACR classification criteria for adult and juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and their major subgroups: a methodology report. RMD Open. 2017;3:e000507. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000507

3. Basharat P, Lahouti AH, Paik JJ, et al. Statin-induced anti-HMGCR-associated myopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:234-235. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.04.037

4. Pinal-Fernandez I, Casal-Dominguez M, Mammen AL. Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2018;20:21. doi: 10.1007/s11926-018-0732-6

5. Mammen AL, Chung T, Christopher-Stine L, et al. Autoantibodies against 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase in patients with statin-associated autoimmune myopathy. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:713-721. doi: 10.1002/art.30156

6. Irvine NJ. Anti-HMGCR myopathy: a rare and serious side effect of statins. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33:785-788. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2020.05.190450

7. Basharat P, Christopher-Stine L. Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy: update on diagnosis and management. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17:72. doi: 10.1007/s11926-015-0548-6

8. Betteridge Z, McHugh N. Myositis-specific autoantibodies: an important tool to support diagnosis of myositis. J Int Med. 2016;280:8-23. doi: 10.1111/joim.12451

1. Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1975;292:344-347. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197502132920706

2. Bottai M, Tjärnlund A, Santoni G, et al. EULAR/ACR classification criteria for adult and juvenile idiopathic inflammatory myopathies and their major subgroups: a methodology report. RMD Open. 2017;3:e000507. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000507

3. Basharat P, Lahouti AH, Paik JJ, et al. Statin-induced anti-HMGCR-associated myopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:234-235. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.04.037

4. Pinal-Fernandez I, Casal-Dominguez M, Mammen AL. Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2018;20:21. doi: 10.1007/s11926-018-0732-6

5. Mammen AL, Chung T, Christopher-Stine L, et al. Autoantibodies against 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase in patients with statin-associated autoimmune myopathy. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:713-721. doi: 10.1002/art.30156

6. Irvine NJ. Anti-HMGCR myopathy: a rare and serious side effect of statins. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33:785-788. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2020.05.190450

7. Basharat P, Christopher-Stine L. Immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy: update on diagnosis and management. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17:72. doi: 10.1007/s11926-015-0548-6

8. Betteridge Z, McHugh N. Myositis-specific autoantibodies: an important tool to support diagnosis of myositis. J Int Med. 2016;280:8-23. doi: 10.1111/joim.12451

► Myalgias and progressive symmetrical proximal weakness

► History of unilateral renal agenesis, type 2 diabetes, and hyperlipidemia

Gout: Studies support early use of urate-lowering therapy, warn of peripheral arterial disease

LA JOLLA, Calif. – A new analysis suggests that it may not be necessary to delay urate-lowering therapy (ULT) in gout flares, and a study warns of the potential heightened risk of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) in gout.

The reports were released at the annual research symposium of the Gout, Hyperuricemia, and Crystal Associated Disease Network (G-CAN).

The urate-lowering report, a systematic review and meta-analysis, suggests that the use of ULT during a gout flare “does not affect flare severity nor the duration of the flare or risk of recurrence in the subsequent month,” lead author Vicky Tai, MBChB, of the University of Auckland (New Zealand), said in a presentation.

She noted that there’s ongoing debate about whether ULT should be delayed until a week or two after gout flares subside to avoid their return. “This is reflected in guidelines on gout management, which have provided inconsistent recommendations on the issue,” Dr. Tai said.

As she noted, the American College of Rheumatology’s 2020 gout guidelines conditionally recommended starting ULT during gout flares – and not afterward – if it’s indicated. (The guidelines also conditionally recommend against ULT in a first gout flare, however, with a few exceptions.)

The British Society for Rheumatology’s 2017 gout guidelines suggested waiting until flares have settled down and “the patient was no longer in pain,” although ULT may be started in patients with frequent attacks. The European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology’s gout guidelines from 2016 didn’t address timing, Dr. Tai said.

For the new analysis, Dr. Tai and colleagues examined six randomized studies from the United States (two), China (two), Taiwan (one), and Thailand (one) that examined the use of allopurinol (three studies), febuxostat (two studies), and probenecid (one). The studies, dated from 2012 to 2023, randomized 226 subjects with gout to early initiation of ULT vs. 219 who received placebo or delayed ULT. Subjects were tracked for a median of 28 days (15 days to 12 weeks).

Three of the studies were deemed to have high risk of bias.

There were no differences in patient-rated pain scores at various time points, duration of gout flares (examined in three studies), or recurrence of gout flares (examined in four studies).

“Other outcomes of interest, including long-term adherence, time to achieve target serum urate, and patient satisfaction with treatment, were not examined,” Dr. Tai said. “Adverse events were similar between groups.”

She cautioned that the sample sizes are small, and the findings may not be applicable to patients with tophaceous gout or comorbid renal disease.

A similar meta-analysis published in 2022 examined five studies (including three of those in the new analysis); among the five was one study from 1987 that examined azapropazone and indomethacin plus allopurinol. The review found “that initiation of ULT during an acute gout flare did not prolong the duration of acute flares.”

Risk for PAD

In the other study, researchers raised an alarm after finding a high rate of PAD in patients with gout regardless of whether they also had diabetes, which is a known risk factor for PAD. “Our data suggest that gout is an underrecognized risk factor for PAD and indicates the importance of assessing for PAD in gout patients,” lead author Nicole Leung, MD, of NYU Langone Health, said in a presentation.

According to Dr. Leung, there’s little known about links between PAD and gout, although she highlighted a 2018 study that found that patients with obstructive coronary artery disease were more likely to have poor outcomes if they also developed gout after catheterization. She highlighted a 2022 study that found higher rates of lower-extremity amputations in patients with gout independent of cardiovascular disease and diabetes. However, she noted that a link to PAD is unclear, and the study found a link between gout and amputations that was independent of PAD.

Patients with gout, she added, are not routinely screened for PAD.

For the new retrospective, cross-sectional analysis, Dr. Leung and colleagues examined Veterans Administration data from 2014 to 2018 for 7.2 million patients. The population was largely male.

Of those, 140,862 (2.52%) – the control group – had no gout or diabetes. In comparison, 11,449 (5.56%) of 205,904 with gout but not diabetes had PAD, for a rate 2.2 times greater than the control group). PAD occurred in 101,582 (8.70%) of 1,168,138 with diabetes but not gout, giving a rate 3.2 times greater than the control group. The rate was highest among people with both gout and diabetes, at 9.97% (9,905 of 99,377), which is about four times greater than the control group.

The link between gout and PAD remained after adjustment for creatinine levels, age, gender, and body mass index. Diabetes was linked to a higher risk for PAD than was gout, and the effect of both conditions combined was “less than additive.” This “may suggest an overlap and pathophysiology between the two,” she said.

Disclosure information was not provided. The Rheumatology Research Foundation funded the PAD study; funding information for the ULT/gout flare analysis was not provided.

LA JOLLA, Calif. – A new analysis suggests that it may not be necessary to delay urate-lowering therapy (ULT) in gout flares, and a study warns of the potential heightened risk of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) in gout.

The reports were released at the annual research symposium of the Gout, Hyperuricemia, and Crystal Associated Disease Network (G-CAN).

The urate-lowering report, a systematic review and meta-analysis, suggests that the use of ULT during a gout flare “does not affect flare severity nor the duration of the flare or risk of recurrence in the subsequent month,” lead author Vicky Tai, MBChB, of the University of Auckland (New Zealand), said in a presentation.

She noted that there’s ongoing debate about whether ULT should be delayed until a week or two after gout flares subside to avoid their return. “This is reflected in guidelines on gout management, which have provided inconsistent recommendations on the issue,” Dr. Tai said.

As she noted, the American College of Rheumatology’s 2020 gout guidelines conditionally recommended starting ULT during gout flares – and not afterward – if it’s indicated. (The guidelines also conditionally recommend against ULT in a first gout flare, however, with a few exceptions.)

The British Society for Rheumatology’s 2017 gout guidelines suggested waiting until flares have settled down and “the patient was no longer in pain,” although ULT may be started in patients with frequent attacks. The European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology’s gout guidelines from 2016 didn’t address timing, Dr. Tai said.

For the new analysis, Dr. Tai and colleagues examined six randomized studies from the United States (two), China (two), Taiwan (one), and Thailand (one) that examined the use of allopurinol (three studies), febuxostat (two studies), and probenecid (one). The studies, dated from 2012 to 2023, randomized 226 subjects with gout to early initiation of ULT vs. 219 who received placebo or delayed ULT. Subjects were tracked for a median of 28 days (15 days to 12 weeks).

Three of the studies were deemed to have high risk of bias.

There were no differences in patient-rated pain scores at various time points, duration of gout flares (examined in three studies), or recurrence of gout flares (examined in four studies).

“Other outcomes of interest, including long-term adherence, time to achieve target serum urate, and patient satisfaction with treatment, were not examined,” Dr. Tai said. “Adverse events were similar between groups.”

She cautioned that the sample sizes are small, and the findings may not be applicable to patients with tophaceous gout or comorbid renal disease.

A similar meta-analysis published in 2022 examined five studies (including three of those in the new analysis); among the five was one study from 1987 that examined azapropazone and indomethacin plus allopurinol. The review found “that initiation of ULT during an acute gout flare did not prolong the duration of acute flares.”

Risk for PAD

In the other study, researchers raised an alarm after finding a high rate of PAD in patients with gout regardless of whether they also had diabetes, which is a known risk factor for PAD. “Our data suggest that gout is an underrecognized risk factor for PAD and indicates the importance of assessing for PAD in gout patients,” lead author Nicole Leung, MD, of NYU Langone Health, said in a presentation.

According to Dr. Leung, there’s little known about links between PAD and gout, although she highlighted a 2018 study that found that patients with obstructive coronary artery disease were more likely to have poor outcomes if they also developed gout after catheterization. She highlighted a 2022 study that found higher rates of lower-extremity amputations in patients with gout independent of cardiovascular disease and diabetes. However, she noted that a link to PAD is unclear, and the study found a link between gout and amputations that was independent of PAD.

Patients with gout, she added, are not routinely screened for PAD.

For the new retrospective, cross-sectional analysis, Dr. Leung and colleagues examined Veterans Administration data from 2014 to 2018 for 7.2 million patients. The population was largely male.

Of those, 140,862 (2.52%) – the control group – had no gout or diabetes. In comparison, 11,449 (5.56%) of 205,904 with gout but not diabetes had PAD, for a rate 2.2 times greater than the control group). PAD occurred in 101,582 (8.70%) of 1,168,138 with diabetes but not gout, giving a rate 3.2 times greater than the control group. The rate was highest among people with both gout and diabetes, at 9.97% (9,905 of 99,377), which is about four times greater than the control group.

The link between gout and PAD remained after adjustment for creatinine levels, age, gender, and body mass index. Diabetes was linked to a higher risk for PAD than was gout, and the effect of both conditions combined was “less than additive.” This “may suggest an overlap and pathophysiology between the two,” she said.

Disclosure information was not provided. The Rheumatology Research Foundation funded the PAD study; funding information for the ULT/gout flare analysis was not provided.

LA JOLLA, Calif. – A new analysis suggests that it may not be necessary to delay urate-lowering therapy (ULT) in gout flares, and a study warns of the potential heightened risk of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) in gout.

The reports were released at the annual research symposium of the Gout, Hyperuricemia, and Crystal Associated Disease Network (G-CAN).

The urate-lowering report, a systematic review and meta-analysis, suggests that the use of ULT during a gout flare “does not affect flare severity nor the duration of the flare or risk of recurrence in the subsequent month,” lead author Vicky Tai, MBChB, of the University of Auckland (New Zealand), said in a presentation.

She noted that there’s ongoing debate about whether ULT should be delayed until a week or two after gout flares subside to avoid their return. “This is reflected in guidelines on gout management, which have provided inconsistent recommendations on the issue,” Dr. Tai said.

As she noted, the American College of Rheumatology’s 2020 gout guidelines conditionally recommended starting ULT during gout flares – and not afterward – if it’s indicated. (The guidelines also conditionally recommend against ULT in a first gout flare, however, with a few exceptions.)

The British Society for Rheumatology’s 2017 gout guidelines suggested waiting until flares have settled down and “the patient was no longer in pain,” although ULT may be started in patients with frequent attacks. The European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology’s gout guidelines from 2016 didn’t address timing, Dr. Tai said.

For the new analysis, Dr. Tai and colleagues examined six randomized studies from the United States (two), China (two), Taiwan (one), and Thailand (one) that examined the use of allopurinol (three studies), febuxostat (two studies), and probenecid (one). The studies, dated from 2012 to 2023, randomized 226 subjects with gout to early initiation of ULT vs. 219 who received placebo or delayed ULT. Subjects were tracked for a median of 28 days (15 days to 12 weeks).

Three of the studies were deemed to have high risk of bias.

There were no differences in patient-rated pain scores at various time points, duration of gout flares (examined in three studies), or recurrence of gout flares (examined in four studies).

“Other outcomes of interest, including long-term adherence, time to achieve target serum urate, and patient satisfaction with treatment, were not examined,” Dr. Tai said. “Adverse events were similar between groups.”

She cautioned that the sample sizes are small, and the findings may not be applicable to patients with tophaceous gout or comorbid renal disease.

A similar meta-analysis published in 2022 examined five studies (including three of those in the new analysis); among the five was one study from 1987 that examined azapropazone and indomethacin plus allopurinol. The review found “that initiation of ULT during an acute gout flare did not prolong the duration of acute flares.”

Risk for PAD

In the other study, researchers raised an alarm after finding a high rate of PAD in patients with gout regardless of whether they also had diabetes, which is a known risk factor for PAD. “Our data suggest that gout is an underrecognized risk factor for PAD and indicates the importance of assessing for PAD in gout patients,” lead author Nicole Leung, MD, of NYU Langone Health, said in a presentation.

According to Dr. Leung, there’s little known about links between PAD and gout, although she highlighted a 2018 study that found that patients with obstructive coronary artery disease were more likely to have poor outcomes if they also developed gout after catheterization. She highlighted a 2022 study that found higher rates of lower-extremity amputations in patients with gout independent of cardiovascular disease and diabetes. However, she noted that a link to PAD is unclear, and the study found a link between gout and amputations that was independent of PAD.

Patients with gout, she added, are not routinely screened for PAD.

For the new retrospective, cross-sectional analysis, Dr. Leung and colleagues examined Veterans Administration data from 2014 to 2018 for 7.2 million patients. The population was largely male.

Of those, 140,862 (2.52%) – the control group – had no gout or diabetes. In comparison, 11,449 (5.56%) of 205,904 with gout but not diabetes had PAD, for a rate 2.2 times greater than the control group). PAD occurred in 101,582 (8.70%) of 1,168,138 with diabetes but not gout, giving a rate 3.2 times greater than the control group. The rate was highest among people with both gout and diabetes, at 9.97% (9,905 of 99,377), which is about four times greater than the control group.

The link between gout and PAD remained after adjustment for creatinine levels, age, gender, and body mass index. Diabetes was linked to a higher risk for PAD than was gout, and the effect of both conditions combined was “less than additive.” This “may suggest an overlap and pathophysiology between the two,” she said.

Disclosure information was not provided. The Rheumatology Research Foundation funded the PAD study; funding information for the ULT/gout flare analysis was not provided.

AT G-CAN 2023

Review estimates acne risk with JAK inhibitor therapy

TOPLINE:

, according to an analysis of 25 JAK inhibitor studies.

METHODOLOGY:

- Acne has been reported to be an adverse effect of JAK inhibitors, but not much is known about how common acne is overall and how incidence differs between different JAK inhibitors and the disease being treated.

- For the systematic review and meta-analysis, researchers identified 25 phase 2 or 3 randomized, controlled trials that reported acne as an adverse event associated with the use of JAK inhibitors.

- The study population included 10,839 participants (54% male, 46% female).

- The primary outcome was the incidence of acne following a period of JAK inhibitor use.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, the risk of acne was significantly higher among those treated with JAK inhibitors in comparison with patients given placebo in a pooled analysis (odds ratio [OR], 3.83).

- The risk of acne was highest with abrocitinib (OR, 13.47), followed by baricitinib (OR, 4.96), upadacitinib (OR, 4.79), deuruxolitinib (OR, 3.30), and deucravacitinib (OR, 2.64). By JAK inhibitor class, results were as follows: JAK1-specific inhibitors (OR, 4.69), combined JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitors (OR, 3.43), and tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitors (OR, 2.64).

- In a subgroup analysis, risk of acne was higher among patients using JAK inhibitors for dermatologic conditions in comparison with those using JAK inhibitors for nondermatologic conditions (OR, 4.67 vs 1.18).

- Age and gender had no apparent impact on the effect of JAK inhibitor use on acne risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“The occurrence of acne following treatment with certain classes of JAK inhibitors is of potential concern, as this adverse effect may jeopardize treatment adherence among some patients,” the researchers wrote. More studies are needed “to characterize the underlying mechanism of acne with JAK inhibitor use and to identify best practices for treatment,” they added.

SOURCE:

The lead author was Jeremy Martinez, MPH, of Harvard Medical School, Boston. The study was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The review was limited by the variable classification and reporting of acne across studies, the potential exclusion of relevant studies, and the small number of studies for certain drugs.

DISCLOSURES:

The studies were mainly funded by the pharmaceutical industry. Mr. Martinez disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors have ties with Dexcel Pharma Technologies, AbbVie, Concert, Pfizer, 3Derm Systems, Incyte, Aclaris, Eli Lilly, Concert, Equillium, ASLAN, ACOM, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, according to an analysis of 25 JAK inhibitor studies.

METHODOLOGY:

- Acne has been reported to be an adverse effect of JAK inhibitors, but not much is known about how common acne is overall and how incidence differs between different JAK inhibitors and the disease being treated.

- For the systematic review and meta-analysis, researchers identified 25 phase 2 or 3 randomized, controlled trials that reported acne as an adverse event associated with the use of JAK inhibitors.

- The study population included 10,839 participants (54% male, 46% female).

- The primary outcome was the incidence of acne following a period of JAK inhibitor use.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, the risk of acne was significantly higher among those treated with JAK inhibitors in comparison with patients given placebo in a pooled analysis (odds ratio [OR], 3.83).

- The risk of acne was highest with abrocitinib (OR, 13.47), followed by baricitinib (OR, 4.96), upadacitinib (OR, 4.79), deuruxolitinib (OR, 3.30), and deucravacitinib (OR, 2.64). By JAK inhibitor class, results were as follows: JAK1-specific inhibitors (OR, 4.69), combined JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitors (OR, 3.43), and tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitors (OR, 2.64).

- In a subgroup analysis, risk of acne was higher among patients using JAK inhibitors for dermatologic conditions in comparison with those using JAK inhibitors for nondermatologic conditions (OR, 4.67 vs 1.18).

- Age and gender had no apparent impact on the effect of JAK inhibitor use on acne risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“The occurrence of acne following treatment with certain classes of JAK inhibitors is of potential concern, as this adverse effect may jeopardize treatment adherence among some patients,” the researchers wrote. More studies are needed “to characterize the underlying mechanism of acne with JAK inhibitor use and to identify best practices for treatment,” they added.

SOURCE:

The lead author was Jeremy Martinez, MPH, of Harvard Medical School, Boston. The study was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The review was limited by the variable classification and reporting of acne across studies, the potential exclusion of relevant studies, and the small number of studies for certain drugs.

DISCLOSURES:

The studies were mainly funded by the pharmaceutical industry. Mr. Martinez disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors have ties with Dexcel Pharma Technologies, AbbVie, Concert, Pfizer, 3Derm Systems, Incyte, Aclaris, Eli Lilly, Concert, Equillium, ASLAN, ACOM, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, according to an analysis of 25 JAK inhibitor studies.

METHODOLOGY:

- Acne has been reported to be an adverse effect of JAK inhibitors, but not much is known about how common acne is overall and how incidence differs between different JAK inhibitors and the disease being treated.

- For the systematic review and meta-analysis, researchers identified 25 phase 2 or 3 randomized, controlled trials that reported acne as an adverse event associated with the use of JAK inhibitors.

- The study population included 10,839 participants (54% male, 46% female).

- The primary outcome was the incidence of acne following a period of JAK inhibitor use.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, the risk of acne was significantly higher among those treated with JAK inhibitors in comparison with patients given placebo in a pooled analysis (odds ratio [OR], 3.83).

- The risk of acne was highest with abrocitinib (OR, 13.47), followed by baricitinib (OR, 4.96), upadacitinib (OR, 4.79), deuruxolitinib (OR, 3.30), and deucravacitinib (OR, 2.64). By JAK inhibitor class, results were as follows: JAK1-specific inhibitors (OR, 4.69), combined JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitors (OR, 3.43), and tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitors (OR, 2.64).

- In a subgroup analysis, risk of acne was higher among patients using JAK inhibitors for dermatologic conditions in comparison with those using JAK inhibitors for nondermatologic conditions (OR, 4.67 vs 1.18).

- Age and gender had no apparent impact on the effect of JAK inhibitor use on acne risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“The occurrence of acne following treatment with certain classes of JAK inhibitors is of potential concern, as this adverse effect may jeopardize treatment adherence among some patients,” the researchers wrote. More studies are needed “to characterize the underlying mechanism of acne with JAK inhibitor use and to identify best practices for treatment,” they added.

SOURCE:

The lead author was Jeremy Martinez, MPH, of Harvard Medical School, Boston. The study was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The review was limited by the variable classification and reporting of acne across studies, the potential exclusion of relevant studies, and the small number of studies for certain drugs.

DISCLOSURES:

The studies were mainly funded by the pharmaceutical industry. Mr. Martinez disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Several coauthors have ties with Dexcel Pharma Technologies, AbbVie, Concert, Pfizer, 3Derm Systems, Incyte, Aclaris, Eli Lilly, Concert, Equillium, ASLAN, ACOM, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Researchers tease apart multiple biologic failure in psoriasis, PsA

WASHINGTON – Multiple biologic failure in a minority of patients with psoriasis may have several causes, from genetic endotypes and immunologic factors to lower serum drug levels, the presence of anti-drug antibody levels, female sex, and certain comorbidities, Wilson Liao, MD, said at the annual research symposium of the National Psoriasis Foundation.

“Tough-to-treat psoriasis remains a challenge despite newer therapies ... Why do we still have this sub-population of patients who seem to be refractory?” said Dr. Liao, professor and associate vice chair of research in the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, who coauthored a 2015-2022 prospective cohort analysis that documented about 6% of patients failing two or more biologic agents of different mechanistic classes.

“These patients are really suffering,” he said. “We need to have better guidelines and treatment algorithms for these patients.”

A significant number of patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA), meanwhile, are inadequate responders to tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibition, Christopher T. Ritchlin, MD, PhD, professor of medicine in the division of allergy/immunology and rheumatology and the Center of Musculoskeletal Research at the University of Rochester (N.Y.), said during another session at the meeting.

The long-term “persistence,” or usage, of first-line biologics in patients with PsA – and of second-line biologics in patients who failed one TNF-inhibitor – is low, but the literature offers little information on the reasons for TNF-inhibitor discontinuation, said Dr. Ritchlin, who coauthored a perspective piece in Arthritis & Rheumatology on managing the patient with PsA who fails one TNF inhibitor.

Dr. Ritchlin and his coauthors were asked to provide evidence-informed advice and algorithms, but the task was difficult. “It’s hard to know what to recommend for the next step if we don’t know why patients failed the first,” he said. “The point is, we need more data. [Clinical trials] are not recording the kind of information we need.”

Anti-drug antibodies, genetics, other factors in psoriasis

Research shows that in large cohorts, “all the biologics do seem to lose efficacy over time,” said Dr. Liao, who directs the UCSF Psoriasis and Skin Treatment Center. “Some are better than others, but we do see a loss of effectiveness over time.”

A cohort study published in 2022 in JAMA Dermatology, for instance, documented declining “drug survival” associated with ineffectiveness during 2 years of treatment for each of five biologics studied (adalimumab [Humira], ustekinumab [Stelara], secukinumab [Cosentyx], guselkumab [Tremfya], and ixekizumab [Taltz]).

“There have been a number of theories put forward” as to why that’s the case, including lower serum drug levels, “which of course can be related to anti-drug antibody production,” he said.

He pointed to two studies of ustekinumab: One prospective observational cohort study that reported an association of lower early drug levels of the IL-12/23 receptor antagonist with lower Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) scores, and another observational study that documented an association between anti-drug antibody positivity with lower ustekinumab levels and impaired clinical response.

“We also now know ... that there are genetic endotypes in psoriasis, and that patients who are [HLA-C*06:02]-positive tend to respond a little better to drugs like ustekinumab, and those who are [HLA-C*06:02]-negative tend to do a little better with the TNF inhibitors,” Dr. Liao said. The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) allele HLA-C*06:02 is associated with susceptibility to psoriasis.

In a study using a national psoriasis registry, HLA-C*06:02-negative patients were 3 times more likely to achieve PASI90 status in response to adalimumab, a TNF-alpha inhibitor, than with ustekinumab treatment. And in a meta-analysis covering eight studies with more than 1,000 patients with psoriasis, the median PASI75 response rate after 6 months of ustekinumab therapy was 92% in the HLA-C*06:02-positive group and 67% in HLA-C*06:02-negative patients.

The recently published cohort study showing a 6% rate of multiple biologic failure evaluated patients in the multicenter CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry who initiated their first biologic between 2015 and 2020 and were followed for 2 or more years. Investigators looked for sociodemographic and clinical differences between the patients who continued use of their first biologic for at least 2 years (“good response”), and those who discontinued two or more biologics of different classes, each used for at least 90 days, because of inadequate efficacy.

Of 1,039 evaluated patients, 490 (47.2%) had good clinical response to their first biologic and 65 (6.3%) had multiple biologic failure. All biologic classes were represented among those who failed multiple biologics. The first and second biologic classes used were attempted for a mean duration of 10 months – “an adequate trial” of each, Dr. Liao said.

In multivariable regression analysis, six variables were significantly associated with multiple biologic failure: female sex at birth, shorter disease duration, earlier year of biologic initiation, prior nonbiologic systemic therapy, having Medicaid insurance, and a history of hyperlipidemia. The latter is “interesting because other studies have shown that metabolic syndrome, of which hyperlipidemia is a component, can also relate to poor response to biologics,” Dr. Liao said.

The most common sequences of first-to-second biologics among those with multiple biologic failure were TNF inhibitor to IL-17 inhibitor (30.8%); IL-12/23 inhibitor to IL-17 inhibitor (21.5%); TNF inhibitor to IL-12/23 inhibitor (12.3%); and IL-17 inhibitor to IL-23 inhibitor (10.8%).

The vast majority of patients failed more than two biologics, however, and “more than 20% had five or more biologics tried over a relatively short period,” Dr. Liao said.

Comorbidities and biologic failure in psoriasis, PsA

In practice, it was said during a discussion period, biologic failures in psoriasis can be of two types: a primary inadequate response or initial failure, or a secondary failure with initial improvement followed by declining or no response. “I agree 100% that these probably represent two different endotypes,” Dr. Liao said. “There’s research emerging that psoriasis isn’t necessarily a clean phenotype.”

The option of focusing on comorbidities in the face of biologic failure was another point of discussion. “Maybe the next biologic is not the answer,” a meeting participant said. “Maybe we should focus on metabolic syndrome.”

“I agree,” Dr. Liao said. “In clinic, there are people who may not respond to therapies but have other comorbidities and factors that make it difficult to manage [their psoriasis] ... that may be causative for psoriasis. Maybe if we treat the comorbidities, it will make it easier to treat the psoriasis.”

Addressing comorbidities and “extra-articular traits” such as poorly controlled diabetes, centralized pain, anxiety and depression, and obesity is something Dr. Ritchlin advocates for PsA. “Centralized pain, I believe, is a major driver of nonresponse,” he said at the meeting. “We have to be careful about blaming nonresponse and lack of efficacy of biologics when it could be a wholly different mechanism the biologic won’t treat ... for example, centralized pain.”

As with psoriasis, the emergence of antidrug antibodies may be one reason for the secondary failure of biologic agents for PsA, Dr. Ritchlin and his coauthors wrote in their paper on management of PsA after failure of one TNF inhibitor. Other areas to consider in evaluating failure, they wrote, are compliance and time of dosing, and financial barriers.

Low long-term persistence of second-line biologics for patients with PsA was demonstrated in a national cohort study utilizing the French health insurance database, Dr. Ritchlin noted at the research meeting.

The French study covered almost 3,000 patients who started a second biologic after discontinuing a TNF inhibitor during 2015-2020. Overall, 1-year and 3-year persistence rates were 42% and 17%, respectively.

Dr. Liao disclosed research grant funding from AbbVie, Amgen, Janssen, Leo, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Trex Bio. Dr. Ritchlin reported no disclosures.

WASHINGTON – Multiple biologic failure in a minority of patients with psoriasis may have several causes, from genetic endotypes and immunologic factors to lower serum drug levels, the presence of anti-drug antibody levels, female sex, and certain comorbidities, Wilson Liao, MD, said at the annual research symposium of the National Psoriasis Foundation.

“Tough-to-treat psoriasis remains a challenge despite newer therapies ... Why do we still have this sub-population of patients who seem to be refractory?” said Dr. Liao, professor and associate vice chair of research in the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, who coauthored a 2015-2022 prospective cohort analysis that documented about 6% of patients failing two or more biologic agents of different mechanistic classes.

“These patients are really suffering,” he said. “We need to have better guidelines and treatment algorithms for these patients.”

A significant number of patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA), meanwhile, are inadequate responders to tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibition, Christopher T. Ritchlin, MD, PhD, professor of medicine in the division of allergy/immunology and rheumatology and the Center of Musculoskeletal Research at the University of Rochester (N.Y.), said during another session at the meeting.

The long-term “persistence,” or usage, of first-line biologics in patients with PsA – and of second-line biologics in patients who failed one TNF-inhibitor – is low, but the literature offers little information on the reasons for TNF-inhibitor discontinuation, said Dr. Ritchlin, who coauthored a perspective piece in Arthritis & Rheumatology on managing the patient with PsA who fails one TNF inhibitor.

Dr. Ritchlin and his coauthors were asked to provide evidence-informed advice and algorithms, but the task was difficult. “It’s hard to know what to recommend for the next step if we don’t know why patients failed the first,” he said. “The point is, we need more data. [Clinical trials] are not recording the kind of information we need.”

Anti-drug antibodies, genetics, other factors in psoriasis

Research shows that in large cohorts, “all the biologics do seem to lose efficacy over time,” said Dr. Liao, who directs the UCSF Psoriasis and Skin Treatment Center. “Some are better than others, but we do see a loss of effectiveness over time.”

A cohort study published in 2022 in JAMA Dermatology, for instance, documented declining “drug survival” associated with ineffectiveness during 2 years of treatment for each of five biologics studied (adalimumab [Humira], ustekinumab [Stelara], secukinumab [Cosentyx], guselkumab [Tremfya], and ixekizumab [Taltz]).

“There have been a number of theories put forward” as to why that’s the case, including lower serum drug levels, “which of course can be related to anti-drug antibody production,” he said.

He pointed to two studies of ustekinumab: One prospective observational cohort study that reported an association of lower early drug levels of the IL-12/23 receptor antagonist with lower Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) scores, and another observational study that documented an association between anti-drug antibody positivity with lower ustekinumab levels and impaired clinical response.

“We also now know ... that there are genetic endotypes in psoriasis, and that patients who are [HLA-C*06:02]-positive tend to respond a little better to drugs like ustekinumab, and those who are [HLA-C*06:02]-negative tend to do a little better with the TNF inhibitors,” Dr. Liao said. The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) allele HLA-C*06:02 is associated with susceptibility to psoriasis.

In a study using a national psoriasis registry, HLA-C*06:02-negative patients were 3 times more likely to achieve PASI90 status in response to adalimumab, a TNF-alpha inhibitor, than with ustekinumab treatment. And in a meta-analysis covering eight studies with more than 1,000 patients with psoriasis, the median PASI75 response rate after 6 months of ustekinumab therapy was 92% in the HLA-C*06:02-positive group and 67% in HLA-C*06:02-negative patients.

The recently published cohort study showing a 6% rate of multiple biologic failure evaluated patients in the multicenter CorEvitas Psoriasis Registry who initiated their first biologic between 2015 and 2020 and were followed for 2 or more years. Investigators looked for sociodemographic and clinical differences between the patients who continued use of their first biologic for at least 2 years (“good response”), and those who discontinued two or more biologics of different classes, each used for at least 90 days, because of inadequate efficacy.

Of 1,039 evaluated patients, 490 (47.2%) had good clinical response to their first biologic and 65 (6.3%) had multiple biologic failure. All biologic classes were represented among those who failed multiple biologics. The first and second biologic classes used were attempted for a mean duration of 10 months – “an adequate trial” of each, Dr. Liao said.

In multivariable regression analysis, six variables were significantly associated with multiple biologic failure: female sex at birth, shorter disease duration, earlier year of biologic initiation, prior nonbiologic systemic therapy, having Medicaid insurance, and a history of hyperlipidemia. The latter is “interesting because other studies have shown that metabolic syndrome, of which hyperlipidemia is a component, can also relate to poor response to biologics,” Dr. Liao said.

The most common sequences of first-to-second biologics among those with multiple biologic failure were TNF inhibitor to IL-17 inhibitor (30.8%); IL-12/23 inhibitor to IL-17 inhibitor (21.5%); TNF inhibitor to IL-12/23 inhibitor (12.3%); and IL-17 inhibitor to IL-23 inhibitor (10.8%).

The vast majority of patients failed more than two biologics, however, and “more than 20% had five or more biologics tried over a relatively short period,” Dr. Liao said.

Comorbidities and biologic failure in psoriasis, PsA

In practice, it was said during a discussion period, biologic failures in psoriasis can be of two types: a primary inadequate response or initial failure, or a secondary failure with initial improvement followed by declining or no response. “I agree 100% that these probably represent two different endotypes,” Dr. Liao said. “There’s research emerging that psoriasis isn’t necessarily a clean phenotype.”

The option of focusing on comorbidities in the face of biologic failure was another point of discussion. “Maybe the next biologic is not the answer,” a meeting participant said. “Maybe we should focus on metabolic syndrome.”

“I agree,” Dr. Liao said. “In clinic, there are people who may not respond to therapies but have other comorbidities and factors that make it difficult to manage [their psoriasis] ... that may be causative for psoriasis. Maybe if we treat the comorbidities, it will make it easier to treat the psoriasis.”

Addressing comorbidities and “extra-articular traits” such as poorly controlled diabetes, centralized pain, anxiety and depression, and obesity is something Dr. Ritchlin advocates for PsA. “Centralized pain, I believe, is a major driver of nonresponse,” he said at the meeting. “We have to be careful about blaming nonresponse and lack of efficacy of biologics when it could be a wholly different mechanism the biologic won’t treat ... for example, centralized pain.”

As with psoriasis, the emergence of antidrug antibodies may be one reason for the secondary failure of biologic agents for PsA, Dr. Ritchlin and his coauthors wrote in their paper on management of PsA after failure of one TNF inhibitor. Other areas to consider in evaluating failure, they wrote, are compliance and time of dosing, and financial barriers.

Low long-term persistence of second-line biologics for patients with PsA was demonstrated in a national cohort study utilizing the French health insurance database, Dr. Ritchlin noted at the research meeting.