User login

Study takes fine-grained look at MACE risk with glucocorticoids in RA

SAN DIEGO – Even when taken at low doses and over short periods, glucocorticoids (GCs) were linked to a higher risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) over the long term in a Veterans Affairs population of older, mostly male patients with rheumatoid arthritis, a new retrospective cohort study has found.

The analysis of nearly 19,000 patients, presented by rheumatologist Beth Wallace, MD, MSc, at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, showed that the level of risk for MACE rose with the dose, duration, and recency of GC use, in which risk increased significantly at prednisone-equivalent doses as low as 5 mg/day, durations as short as 30 days, and with last use as long as 1 year before MACE.

“Up to half of RA patients in the United States use long-term glucocorticoids despite previous work suggesting they increase MACE in a dose-dependent way,” said Dr. Wallace, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and a rheumatologist at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare Center. “Our group previously presented work suggesting that less than 14 days of glucocorticoid use in a 6-month period is associated with a two-thirds increase in odds of MACE over the following 6 months, with 90 days of use associated with more than twofold increase.”

In recent years, researchers such as Dr. Wallace have focused attention on the risks of GCs in RA. The American College of Rheumatology and the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology emphasize avoiding long-term use of GCs in RA and keeping doses as small and over the shortest amount of time as possible.

When Dr. Wallace and colleagues looked at the clinical pattern of GC use for patients with RA during the past 2 years, those who took 5 mg, 7.5 mg, and 10 mg daily doses for 30 days and had stopped at least a year before had risk for MACE that rose significantly by 3%, 5%, and 7%, respectively, compared with those who didn’t take GCs in the past 2 years.

While those increases were small, risk for MACE rose even more for those who took the same daily doses for 90 days, increasing 10%, 15%, and 21%, respectively. Researchers linked current ongoing use of GCs for the past 90 days to a 13%, 19%, and 27% higher risk for MACE at those respective doses.

The findings “add to the literature suggesting that there is some risk even with low-dose steroids,” said Michael George, MD, assistant professor of rheumatology and epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, who did not take part in the research but is familiar with the findings.

“We can see that even glucocorticoids taken several years ago may affect cardiovascular risk but that recent use has a bigger effect on risk,” Dr. George said in an interview. “This study also suggests that very low-dose use affects risk.”

For the new study, Dr. Wallace and colleagues examined a Veterans Affairs database and identified 18,882 patients with RA (mean age, 62.5 years; 84% male; 66% GC users) who met the criteria of being > 40 and < 90 years old. The subjects had an initial VA rheumatology visit during 2010-2018 and were excluded if they had a non-RA rheumatologic disorder, prior MACE, or heart failure. MACE was defined as MI, stroke/TIA, cardiac arrest, coronary revascularization, or death from CV cause.

A total of 16% of the cohort had the largest exposure to GCs, defined as use for 90 days or more; 23% had exposure of 14-89 days, and 14% had exposure of 1-13 days.

The median 5-year MACE risk at baseline was 5.3%, and 3,754 patients (19.9%) had high baseline MACE risk. Incident MACE occurred in 4.1% of patients, and the median time to MACE was 2.67 years (interquartile ratio, 1.26-4.45 years).

Covariates included factors such as age, race, sex, body mass index, smoking status, adjusted Elixhauser index, VA risk score for cardiovascular disease, cancer, hospitalization for infection, number of rheumatology clinic visits, and use of lipid-lowering drugs, opioids, methotrexate, biologics, and hydroxychloroquine.

Dr. Wallace noted limitations including the possibility of residual confounding and the influence of background cardiovascular risk. The study didn’t examine the clinical value of taking GCs or compare that to the potential risk. Nor did it examine cost or the risks and benefits of alternative therapeutic options.

A study released earlier this year suggested that patients taking daily prednisolone doses under 5 mg do not have a higher risk of MACE. Previous studies had reached conflicting results.

“Glucocorticoids can provide major benefits to patients, but these benefits must be balanced with the potential risks,” Dr. George said. At low doses, these risks may be small, but they are present. In many cases, escalating DMARD [disease-modifying antirheumatic drug] therapy may be safer than continuing glucocorticoids.”

He added that the risks of GCs may be especially high in older patients and in those who have cardiovascular risk factors: “Often biologics are avoided in these higher-risk patients. But in fact, in many cases biologics may be the safer choice.”

No study funding was reported. Dr. Wallace reported no relevant financial relationships, and some of the other authors reported various ties with industry. Dr. George reported research funding from GlaxoSmithKline and Janssen and consulting fees from AbbVie.

SAN DIEGO – Even when taken at low doses and over short periods, glucocorticoids (GCs) were linked to a higher risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) over the long term in a Veterans Affairs population of older, mostly male patients with rheumatoid arthritis, a new retrospective cohort study has found.

The analysis of nearly 19,000 patients, presented by rheumatologist Beth Wallace, MD, MSc, at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, showed that the level of risk for MACE rose with the dose, duration, and recency of GC use, in which risk increased significantly at prednisone-equivalent doses as low as 5 mg/day, durations as short as 30 days, and with last use as long as 1 year before MACE.

“Up to half of RA patients in the United States use long-term glucocorticoids despite previous work suggesting they increase MACE in a dose-dependent way,” said Dr. Wallace, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and a rheumatologist at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare Center. “Our group previously presented work suggesting that less than 14 days of glucocorticoid use in a 6-month period is associated with a two-thirds increase in odds of MACE over the following 6 months, with 90 days of use associated with more than twofold increase.”

In recent years, researchers such as Dr. Wallace have focused attention on the risks of GCs in RA. The American College of Rheumatology and the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology emphasize avoiding long-term use of GCs in RA and keeping doses as small and over the shortest amount of time as possible.

When Dr. Wallace and colleagues looked at the clinical pattern of GC use for patients with RA during the past 2 years, those who took 5 mg, 7.5 mg, and 10 mg daily doses for 30 days and had stopped at least a year before had risk for MACE that rose significantly by 3%, 5%, and 7%, respectively, compared with those who didn’t take GCs in the past 2 years.

While those increases were small, risk for MACE rose even more for those who took the same daily doses for 90 days, increasing 10%, 15%, and 21%, respectively. Researchers linked current ongoing use of GCs for the past 90 days to a 13%, 19%, and 27% higher risk for MACE at those respective doses.

The findings “add to the literature suggesting that there is some risk even with low-dose steroids,” said Michael George, MD, assistant professor of rheumatology and epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, who did not take part in the research but is familiar with the findings.

“We can see that even glucocorticoids taken several years ago may affect cardiovascular risk but that recent use has a bigger effect on risk,” Dr. George said in an interview. “This study also suggests that very low-dose use affects risk.”

For the new study, Dr. Wallace and colleagues examined a Veterans Affairs database and identified 18,882 patients with RA (mean age, 62.5 years; 84% male; 66% GC users) who met the criteria of being > 40 and < 90 years old. The subjects had an initial VA rheumatology visit during 2010-2018 and were excluded if they had a non-RA rheumatologic disorder, prior MACE, or heart failure. MACE was defined as MI, stroke/TIA, cardiac arrest, coronary revascularization, or death from CV cause.

A total of 16% of the cohort had the largest exposure to GCs, defined as use for 90 days or more; 23% had exposure of 14-89 days, and 14% had exposure of 1-13 days.

The median 5-year MACE risk at baseline was 5.3%, and 3,754 patients (19.9%) had high baseline MACE risk. Incident MACE occurred in 4.1% of patients, and the median time to MACE was 2.67 years (interquartile ratio, 1.26-4.45 years).

Covariates included factors such as age, race, sex, body mass index, smoking status, adjusted Elixhauser index, VA risk score for cardiovascular disease, cancer, hospitalization for infection, number of rheumatology clinic visits, and use of lipid-lowering drugs, opioids, methotrexate, biologics, and hydroxychloroquine.

Dr. Wallace noted limitations including the possibility of residual confounding and the influence of background cardiovascular risk. The study didn’t examine the clinical value of taking GCs or compare that to the potential risk. Nor did it examine cost or the risks and benefits of alternative therapeutic options.

A study released earlier this year suggested that patients taking daily prednisolone doses under 5 mg do not have a higher risk of MACE. Previous studies had reached conflicting results.

“Glucocorticoids can provide major benefits to patients, but these benefits must be balanced with the potential risks,” Dr. George said. At low doses, these risks may be small, but they are present. In many cases, escalating DMARD [disease-modifying antirheumatic drug] therapy may be safer than continuing glucocorticoids.”

He added that the risks of GCs may be especially high in older patients and in those who have cardiovascular risk factors: “Often biologics are avoided in these higher-risk patients. But in fact, in many cases biologics may be the safer choice.”

No study funding was reported. Dr. Wallace reported no relevant financial relationships, and some of the other authors reported various ties with industry. Dr. George reported research funding from GlaxoSmithKline and Janssen and consulting fees from AbbVie.

SAN DIEGO – Even when taken at low doses and over short periods, glucocorticoids (GCs) were linked to a higher risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) over the long term in a Veterans Affairs population of older, mostly male patients with rheumatoid arthritis, a new retrospective cohort study has found.

The analysis of nearly 19,000 patients, presented by rheumatologist Beth Wallace, MD, MSc, at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, showed that the level of risk for MACE rose with the dose, duration, and recency of GC use, in which risk increased significantly at prednisone-equivalent doses as low as 5 mg/day, durations as short as 30 days, and with last use as long as 1 year before MACE.

“Up to half of RA patients in the United States use long-term glucocorticoids despite previous work suggesting they increase MACE in a dose-dependent way,” said Dr. Wallace, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and a rheumatologist at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare Center. “Our group previously presented work suggesting that less than 14 days of glucocorticoid use in a 6-month period is associated with a two-thirds increase in odds of MACE over the following 6 months, with 90 days of use associated with more than twofold increase.”

In recent years, researchers such as Dr. Wallace have focused attention on the risks of GCs in RA. The American College of Rheumatology and the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology emphasize avoiding long-term use of GCs in RA and keeping doses as small and over the shortest amount of time as possible.

When Dr. Wallace and colleagues looked at the clinical pattern of GC use for patients with RA during the past 2 years, those who took 5 mg, 7.5 mg, and 10 mg daily doses for 30 days and had stopped at least a year before had risk for MACE that rose significantly by 3%, 5%, and 7%, respectively, compared with those who didn’t take GCs in the past 2 years.

While those increases were small, risk for MACE rose even more for those who took the same daily doses for 90 days, increasing 10%, 15%, and 21%, respectively. Researchers linked current ongoing use of GCs for the past 90 days to a 13%, 19%, and 27% higher risk for MACE at those respective doses.

The findings “add to the literature suggesting that there is some risk even with low-dose steroids,” said Michael George, MD, assistant professor of rheumatology and epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, who did not take part in the research but is familiar with the findings.

“We can see that even glucocorticoids taken several years ago may affect cardiovascular risk but that recent use has a bigger effect on risk,” Dr. George said in an interview. “This study also suggests that very low-dose use affects risk.”

For the new study, Dr. Wallace and colleagues examined a Veterans Affairs database and identified 18,882 patients with RA (mean age, 62.5 years; 84% male; 66% GC users) who met the criteria of being > 40 and < 90 years old. The subjects had an initial VA rheumatology visit during 2010-2018 and were excluded if they had a non-RA rheumatologic disorder, prior MACE, or heart failure. MACE was defined as MI, stroke/TIA, cardiac arrest, coronary revascularization, or death from CV cause.

A total of 16% of the cohort had the largest exposure to GCs, defined as use for 90 days or more; 23% had exposure of 14-89 days, and 14% had exposure of 1-13 days.

The median 5-year MACE risk at baseline was 5.3%, and 3,754 patients (19.9%) had high baseline MACE risk. Incident MACE occurred in 4.1% of patients, and the median time to MACE was 2.67 years (interquartile ratio, 1.26-4.45 years).

Covariates included factors such as age, race, sex, body mass index, smoking status, adjusted Elixhauser index, VA risk score for cardiovascular disease, cancer, hospitalization for infection, number of rheumatology clinic visits, and use of lipid-lowering drugs, opioids, methotrexate, biologics, and hydroxychloroquine.

Dr. Wallace noted limitations including the possibility of residual confounding and the influence of background cardiovascular risk. The study didn’t examine the clinical value of taking GCs or compare that to the potential risk. Nor did it examine cost or the risks and benefits of alternative therapeutic options.

A study released earlier this year suggested that patients taking daily prednisolone doses under 5 mg do not have a higher risk of MACE. Previous studies had reached conflicting results.

“Glucocorticoids can provide major benefits to patients, but these benefits must be balanced with the potential risks,” Dr. George said. At low doses, these risks may be small, but they are present. In many cases, escalating DMARD [disease-modifying antirheumatic drug] therapy may be safer than continuing glucocorticoids.”

He added that the risks of GCs may be especially high in older patients and in those who have cardiovascular risk factors: “Often biologics are avoided in these higher-risk patients. But in fact, in many cases biologics may be the safer choice.”

No study funding was reported. Dr. Wallace reported no relevant financial relationships, and some of the other authors reported various ties with industry. Dr. George reported research funding from GlaxoSmithKline and Janssen and consulting fees from AbbVie.

AT ACR 2023

AI tool perfect in study of inflammatory diseases

Artificial intelligence can distinguish overlapping inflammatory conditions with total accuracy, according to a new study presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Texas pediatricians faced a conundrum during the pandemic. Endemic typhus, a flea-borne tropical infection common to the region, is nearly indistinguishable from multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), a rare condition set in motion by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Children with either ailment had seemingly identical symptoms: fever, rash, gastrointestinal issues, and in need of swift treatment. A diagnosis of endemic typhus can take 4-6 days to confirm.

Tiphanie Vogel, MD, PhD, a pediatric rheumatologist at Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, and colleagues sought to create a tool to hasten diagnosis and, ideally, treatment. To do so, they incorporated machine learning and clinical factors available within the first 6 hours of the onset of symptoms.

The team analyzed 49 demographic, clinical, and laboratory measures from the medical records of 133 children with MIS-C and 87 with endemic typhus. Using deep learning, they narrowed the model to 30 essential features that became the backbone of AI-MET, a two-phase clinical-decision support system.

Phase 1 uses 17 clinical factors and can be performed on paper. If a patient’s score in phase 1 is not determinative, clinicians proceed to phase 2, which uses an additional 13 weighted factors and machine learning.

In testing, the two-part tool classified each of the 220 test patients perfectly. And it diagnosed a second group of 111 patients with MIS-C with 99% (110/111) accuracy.

Of note, “that first step classifies [a patient] correctly half of the time,” Dr. Vogel said, so the second, AI phase of the tool was necessary for only half of cases. Dr. Vogel said that’s a good sign; it means that the tool is useful in settings where AI may not always be feasible, like in a busy ED.

Melissa Mizesko, MD, a pediatric rheumatologist at Driscoll Children’s Hospital in Corpus Christi, Tex., said that the new tool could help clinicians streamline care. When cases of MIS-C peaked in Texas, clinicians often would start sick children on doxycycline and treat for MIS-C at the same time, then wait to see whether the antibiotic brought the fever down.

“This [new tool] is helpful if you live in a part of the country that has typhus,” said Jane Burns, MD, director of the Kawasaki Disease Research Center at the University of California, San Diego, who helped develop a similar AI-based tool to distinguish MIS-C from Kawasaki disease. But she encouraged the researchers to expand their testing to include other conditions. Although the AI model Dr. Vogel’s group developed can pinpoint MIS-C or endemic typhus, what if a child has neither condition? “It’s not often you’re dealing with a diagnosis between just two specific diseases,” Dr. Burns said.

Dr. Vogel is also interested in making AI-MET more efficient. “This go-round we prioritized perfect accuracy,” she said. But 30 clinical factors, with 17 of them recorded and calculated by hand, is a lot. “Could we still get this to be very accurate, maybe not perfect, with less inputs?”

In addition to refining AI-MET, which Texas Children’s eventually hopes to make available to other institutions, Dr. Vogel and associates are also considering other use cases for AI. Lupus is one option. “Maybe with machine learning we could identify clues at diagnosis that would help recommend targeted treatment,” she said

Dr. Vogel disclosed potential conflicts of interest with Moderna, Novartis, Pfizer, and SOBI. Dr. Burns and Dr. Mizesko disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Artificial intelligence can distinguish overlapping inflammatory conditions with total accuracy, according to a new study presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Texas pediatricians faced a conundrum during the pandemic. Endemic typhus, a flea-borne tropical infection common to the region, is nearly indistinguishable from multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), a rare condition set in motion by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Children with either ailment had seemingly identical symptoms: fever, rash, gastrointestinal issues, and in need of swift treatment. A diagnosis of endemic typhus can take 4-6 days to confirm.

Tiphanie Vogel, MD, PhD, a pediatric rheumatologist at Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, and colleagues sought to create a tool to hasten diagnosis and, ideally, treatment. To do so, they incorporated machine learning and clinical factors available within the first 6 hours of the onset of symptoms.

The team analyzed 49 demographic, clinical, and laboratory measures from the medical records of 133 children with MIS-C and 87 with endemic typhus. Using deep learning, they narrowed the model to 30 essential features that became the backbone of AI-MET, a two-phase clinical-decision support system.

Phase 1 uses 17 clinical factors and can be performed on paper. If a patient’s score in phase 1 is not determinative, clinicians proceed to phase 2, which uses an additional 13 weighted factors and machine learning.

In testing, the two-part tool classified each of the 220 test patients perfectly. And it diagnosed a second group of 111 patients with MIS-C with 99% (110/111) accuracy.

Of note, “that first step classifies [a patient] correctly half of the time,” Dr. Vogel said, so the second, AI phase of the tool was necessary for only half of cases. Dr. Vogel said that’s a good sign; it means that the tool is useful in settings where AI may not always be feasible, like in a busy ED.

Melissa Mizesko, MD, a pediatric rheumatologist at Driscoll Children’s Hospital in Corpus Christi, Tex., said that the new tool could help clinicians streamline care. When cases of MIS-C peaked in Texas, clinicians often would start sick children on doxycycline and treat for MIS-C at the same time, then wait to see whether the antibiotic brought the fever down.

“This [new tool] is helpful if you live in a part of the country that has typhus,” said Jane Burns, MD, director of the Kawasaki Disease Research Center at the University of California, San Diego, who helped develop a similar AI-based tool to distinguish MIS-C from Kawasaki disease. But she encouraged the researchers to expand their testing to include other conditions. Although the AI model Dr. Vogel’s group developed can pinpoint MIS-C or endemic typhus, what if a child has neither condition? “It’s not often you’re dealing with a diagnosis between just two specific diseases,” Dr. Burns said.

Dr. Vogel is also interested in making AI-MET more efficient. “This go-round we prioritized perfect accuracy,” she said. But 30 clinical factors, with 17 of them recorded and calculated by hand, is a lot. “Could we still get this to be very accurate, maybe not perfect, with less inputs?”

In addition to refining AI-MET, which Texas Children’s eventually hopes to make available to other institutions, Dr. Vogel and associates are also considering other use cases for AI. Lupus is one option. “Maybe with machine learning we could identify clues at diagnosis that would help recommend targeted treatment,” she said

Dr. Vogel disclosed potential conflicts of interest with Moderna, Novartis, Pfizer, and SOBI. Dr. Burns and Dr. Mizesko disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Artificial intelligence can distinguish overlapping inflammatory conditions with total accuracy, according to a new study presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Texas pediatricians faced a conundrum during the pandemic. Endemic typhus, a flea-borne tropical infection common to the region, is nearly indistinguishable from multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), a rare condition set in motion by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Children with either ailment had seemingly identical symptoms: fever, rash, gastrointestinal issues, and in need of swift treatment. A diagnosis of endemic typhus can take 4-6 days to confirm.

Tiphanie Vogel, MD, PhD, a pediatric rheumatologist at Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, and colleagues sought to create a tool to hasten diagnosis and, ideally, treatment. To do so, they incorporated machine learning and clinical factors available within the first 6 hours of the onset of symptoms.

The team analyzed 49 demographic, clinical, and laboratory measures from the medical records of 133 children with MIS-C and 87 with endemic typhus. Using deep learning, they narrowed the model to 30 essential features that became the backbone of AI-MET, a two-phase clinical-decision support system.

Phase 1 uses 17 clinical factors and can be performed on paper. If a patient’s score in phase 1 is not determinative, clinicians proceed to phase 2, which uses an additional 13 weighted factors and machine learning.

In testing, the two-part tool classified each of the 220 test patients perfectly. And it diagnosed a second group of 111 patients with MIS-C with 99% (110/111) accuracy.

Of note, “that first step classifies [a patient] correctly half of the time,” Dr. Vogel said, so the second, AI phase of the tool was necessary for only half of cases. Dr. Vogel said that’s a good sign; it means that the tool is useful in settings where AI may not always be feasible, like in a busy ED.

Melissa Mizesko, MD, a pediatric rheumatologist at Driscoll Children’s Hospital in Corpus Christi, Tex., said that the new tool could help clinicians streamline care. When cases of MIS-C peaked in Texas, clinicians often would start sick children on doxycycline and treat for MIS-C at the same time, then wait to see whether the antibiotic brought the fever down.

“This [new tool] is helpful if you live in a part of the country that has typhus,” said Jane Burns, MD, director of the Kawasaki Disease Research Center at the University of California, San Diego, who helped develop a similar AI-based tool to distinguish MIS-C from Kawasaki disease. But she encouraged the researchers to expand their testing to include other conditions. Although the AI model Dr. Vogel’s group developed can pinpoint MIS-C or endemic typhus, what if a child has neither condition? “It’s not often you’re dealing with a diagnosis between just two specific diseases,” Dr. Burns said.

Dr. Vogel is also interested in making AI-MET more efficient. “This go-round we prioritized perfect accuracy,” she said. But 30 clinical factors, with 17 of them recorded and calculated by hand, is a lot. “Could we still get this to be very accurate, maybe not perfect, with less inputs?”

In addition to refining AI-MET, which Texas Children’s eventually hopes to make available to other institutions, Dr. Vogel and associates are also considering other use cases for AI. Lupus is one option. “Maybe with machine learning we could identify clues at diagnosis that would help recommend targeted treatment,” she said

Dr. Vogel disclosed potential conflicts of interest with Moderna, Novartis, Pfizer, and SOBI. Dr. Burns and Dr. Mizesko disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ACR 2023

TNF inhibitors may be OK for treating RA-associated interstitial lung disease

SAN DIEGO – Patients with rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) who start a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) appear to have rates of survival and respiratory-related hospitalization similar to those initiating a non-TNFi biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD) or Janus kinase inhibitor (JAKi), results from a large pharmacoepidemiologic study show.

“These results challenge some of the findings in prior literature that perhaps TNFi should be avoided in RA-ILD,” lead study investigator Bryant R. England, MD, PhD, said in an interview. The findings were presented during a plenary session at the American College of Rheumatology annual meeting.

Dr. England, associate professor of rheumatology and immunology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, said that while RA-ILD carries a poor prognosis, a paucity of evidence exists on the effectiveness and safety of disease-modifying therapies in this population.

It’s a pleasant surprise “to see that the investigators were unable to demonstrate a significant difference in the risk of respiratory hospitalization or death between people with RA-ILD initiating non-TNFi/JAKi versus TNFi. Here is a unique situation where a so called ‘negative’ study contributes important information. This study provides needed safety data, as they were unable to show that TNFi results in worsening of severe RA-ILD outcomes,” Sindhu R. Johnson, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at the University of Toronto, said when asked for comment on the study.

“While this study does not address the use of these medications for the treatment of RA-ILD, these data suggest that TNFi may remain a treatment option for articular disease in people with RA-ILD,” said Dr. Johnson, who was not involved with the study.

For the study, Dr. England and colleagues drew from Veterans Health Administration data between 2006 and 2018 to identify patients with RA-ILD initiating TNFi or non-TNFi biologic/JAKi for the first time. Those who received ILD-focused therapies such as mycophenolate and antifibrotics were excluded from the analysis.

The researchers used validated administrative algorithms requiring multiple RA and ILD diagnostic codes to identify RA-ILD and used 1:1 propensity score matching to compare TNFi and non-TNFi biologic/JAKi factors such as health care use, comorbidities, and several RA-ILD factors, such as pretreatment forced vital capacity, obtained from electronic health records and administrative data. The primary outcome was a composite of time to respiratory-related hospitalization or death using Cox regression models.

Dr. England reported findings from 237 TNFi initiators and 237 non-TNFi/JAKi initiators. Their mean age was 68 years and 92% were male. After matching, the mean standardized differences of variables in the propensity score model improved, but a few variables remained slightly imbalanced, such as two markers of inflammation, inhaled corticosteroid use, and body mass index. The most frequently prescribed TNFi drugs were adalimumab (51%) and etanercept (37%), and the most frequently prescribed non-TNFi/JAKi drugs were rituximab (53%) and abatacept (28%).

The researchers observed no significant difference in the primary outcome between non-TNFi/JAKi and TNFi initiators (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.22; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.92-1.60). They also observed no significant differences in respiratory hospitalization, all-cause mortality, or respiratory-related death at 1 and 3 years. In sensitivity analyses with modified cohort eligibility requirements, no significant differences in outcomes were observed between non-TNFi/JAKi and TNFi initiators.

During his presentation at the meeting, Dr. England posed the question: Are TNFi drugs safe to be used in RA-ILD?

“The answer is: It’s complex,” he said. “Our findings don’t suggest that we should be systematically avoiding TNFis with every single person with RA-ILD. But that’s different than whether there are specific subpopulations of RA-ILD for which the choice of these therapies may differ. Unfortunately, we could not address that in this study. We also could not address whether TNFis have efficacy at stopping, slowing, or reversing progression of the ILD itself. This calls for us as a field to gather together and pursue clinical trials to try to generate robust evidence that can guide these important clinical decisions that we’re making with our patients.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its observational design. “So, despite best efforts to minimize bias with pharmacoepidemiologic designs and approaches, there could still be confounding and selection,” he said. “Additionally, RA-ILD is a heterogeneous disease characterized by different patterns and trajectories. While we did account for several RA- and ILD-related factors, we could not account for all heterogeneity in RA-ILD.”

When asked for comment on the study, session moderator Janet Pope, MD, MPH, professor of medicine in the division of rheumatology at the University of Western Ontario, London, said that the study findings surprised her.

“Sometimes RA patients on TNFis were thought to have more new or worsening ILD vs. [those on] non-TNFi bDMARDs, but most [data were] from older studies where TNFis were used as initial bDMARD in sicker patients,” she told this news organization. “So, data were confounded previously. Even in this study, there may have been channeling bias as it was not a randomized controlled trial. We need a definitive randomized controlled trial to answer this question of what the most optimal therapy for RA-ILD is.”

Dr. England reports receiving consulting fees and research support from Boehringer Ingelheim, and several coauthors reported financial relationships from various pharmaceutical companies and medical publishers. Dr. Johnson reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Pope reports being a consultant for several pharmaceutical companies. She has received grant/research support from AbbVie/Abbott and Eli Lilly and is an adviser for Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO – Patients with rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) who start a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) appear to have rates of survival and respiratory-related hospitalization similar to those initiating a non-TNFi biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD) or Janus kinase inhibitor (JAKi), results from a large pharmacoepidemiologic study show.

“These results challenge some of the findings in prior literature that perhaps TNFi should be avoided in RA-ILD,” lead study investigator Bryant R. England, MD, PhD, said in an interview. The findings were presented during a plenary session at the American College of Rheumatology annual meeting.

Dr. England, associate professor of rheumatology and immunology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, said that while RA-ILD carries a poor prognosis, a paucity of evidence exists on the effectiveness and safety of disease-modifying therapies in this population.

It’s a pleasant surprise “to see that the investigators were unable to demonstrate a significant difference in the risk of respiratory hospitalization or death between people with RA-ILD initiating non-TNFi/JAKi versus TNFi. Here is a unique situation where a so called ‘negative’ study contributes important information. This study provides needed safety data, as they were unable to show that TNFi results in worsening of severe RA-ILD outcomes,” Sindhu R. Johnson, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at the University of Toronto, said when asked for comment on the study.

“While this study does not address the use of these medications for the treatment of RA-ILD, these data suggest that TNFi may remain a treatment option for articular disease in people with RA-ILD,” said Dr. Johnson, who was not involved with the study.

For the study, Dr. England and colleagues drew from Veterans Health Administration data between 2006 and 2018 to identify patients with RA-ILD initiating TNFi or non-TNFi biologic/JAKi for the first time. Those who received ILD-focused therapies such as mycophenolate and antifibrotics were excluded from the analysis.

The researchers used validated administrative algorithms requiring multiple RA and ILD diagnostic codes to identify RA-ILD and used 1:1 propensity score matching to compare TNFi and non-TNFi biologic/JAKi factors such as health care use, comorbidities, and several RA-ILD factors, such as pretreatment forced vital capacity, obtained from electronic health records and administrative data. The primary outcome was a composite of time to respiratory-related hospitalization or death using Cox regression models.

Dr. England reported findings from 237 TNFi initiators and 237 non-TNFi/JAKi initiators. Their mean age was 68 years and 92% were male. After matching, the mean standardized differences of variables in the propensity score model improved, but a few variables remained slightly imbalanced, such as two markers of inflammation, inhaled corticosteroid use, and body mass index. The most frequently prescribed TNFi drugs were adalimumab (51%) and etanercept (37%), and the most frequently prescribed non-TNFi/JAKi drugs were rituximab (53%) and abatacept (28%).

The researchers observed no significant difference in the primary outcome between non-TNFi/JAKi and TNFi initiators (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.22; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.92-1.60). They also observed no significant differences in respiratory hospitalization, all-cause mortality, or respiratory-related death at 1 and 3 years. In sensitivity analyses with modified cohort eligibility requirements, no significant differences in outcomes were observed between non-TNFi/JAKi and TNFi initiators.

During his presentation at the meeting, Dr. England posed the question: Are TNFi drugs safe to be used in RA-ILD?

“The answer is: It’s complex,” he said. “Our findings don’t suggest that we should be systematically avoiding TNFis with every single person with RA-ILD. But that’s different than whether there are specific subpopulations of RA-ILD for which the choice of these therapies may differ. Unfortunately, we could not address that in this study. We also could not address whether TNFis have efficacy at stopping, slowing, or reversing progression of the ILD itself. This calls for us as a field to gather together and pursue clinical trials to try to generate robust evidence that can guide these important clinical decisions that we’re making with our patients.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its observational design. “So, despite best efforts to minimize bias with pharmacoepidemiologic designs and approaches, there could still be confounding and selection,” he said. “Additionally, RA-ILD is a heterogeneous disease characterized by different patterns and trajectories. While we did account for several RA- and ILD-related factors, we could not account for all heterogeneity in RA-ILD.”

When asked for comment on the study, session moderator Janet Pope, MD, MPH, professor of medicine in the division of rheumatology at the University of Western Ontario, London, said that the study findings surprised her.

“Sometimes RA patients on TNFis were thought to have more new or worsening ILD vs. [those on] non-TNFi bDMARDs, but most [data were] from older studies where TNFis were used as initial bDMARD in sicker patients,” she told this news organization. “So, data were confounded previously. Even in this study, there may have been channeling bias as it was not a randomized controlled trial. We need a definitive randomized controlled trial to answer this question of what the most optimal therapy for RA-ILD is.”

Dr. England reports receiving consulting fees and research support from Boehringer Ingelheim, and several coauthors reported financial relationships from various pharmaceutical companies and medical publishers. Dr. Johnson reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Pope reports being a consultant for several pharmaceutical companies. She has received grant/research support from AbbVie/Abbott and Eli Lilly and is an adviser for Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO – Patients with rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) who start a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) appear to have rates of survival and respiratory-related hospitalization similar to those initiating a non-TNFi biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD) or Janus kinase inhibitor (JAKi), results from a large pharmacoepidemiologic study show.

“These results challenge some of the findings in prior literature that perhaps TNFi should be avoided in RA-ILD,” lead study investigator Bryant R. England, MD, PhD, said in an interview. The findings were presented during a plenary session at the American College of Rheumatology annual meeting.

Dr. England, associate professor of rheumatology and immunology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, said that while RA-ILD carries a poor prognosis, a paucity of evidence exists on the effectiveness and safety of disease-modifying therapies in this population.

It’s a pleasant surprise “to see that the investigators were unable to demonstrate a significant difference in the risk of respiratory hospitalization or death between people with RA-ILD initiating non-TNFi/JAKi versus TNFi. Here is a unique situation where a so called ‘negative’ study contributes important information. This study provides needed safety data, as they were unable to show that TNFi results in worsening of severe RA-ILD outcomes,” Sindhu R. Johnson, MD, PhD, professor of medicine at the University of Toronto, said when asked for comment on the study.

“While this study does not address the use of these medications for the treatment of RA-ILD, these data suggest that TNFi may remain a treatment option for articular disease in people with RA-ILD,” said Dr. Johnson, who was not involved with the study.

For the study, Dr. England and colleagues drew from Veterans Health Administration data between 2006 and 2018 to identify patients with RA-ILD initiating TNFi or non-TNFi biologic/JAKi for the first time. Those who received ILD-focused therapies such as mycophenolate and antifibrotics were excluded from the analysis.

The researchers used validated administrative algorithms requiring multiple RA and ILD diagnostic codes to identify RA-ILD and used 1:1 propensity score matching to compare TNFi and non-TNFi biologic/JAKi factors such as health care use, comorbidities, and several RA-ILD factors, such as pretreatment forced vital capacity, obtained from electronic health records and administrative data. The primary outcome was a composite of time to respiratory-related hospitalization or death using Cox regression models.

Dr. England reported findings from 237 TNFi initiators and 237 non-TNFi/JAKi initiators. Their mean age was 68 years and 92% were male. After matching, the mean standardized differences of variables in the propensity score model improved, but a few variables remained slightly imbalanced, such as two markers of inflammation, inhaled corticosteroid use, and body mass index. The most frequently prescribed TNFi drugs were adalimumab (51%) and etanercept (37%), and the most frequently prescribed non-TNFi/JAKi drugs were rituximab (53%) and abatacept (28%).

The researchers observed no significant difference in the primary outcome between non-TNFi/JAKi and TNFi initiators (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.22; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.92-1.60). They also observed no significant differences in respiratory hospitalization, all-cause mortality, or respiratory-related death at 1 and 3 years. In sensitivity analyses with modified cohort eligibility requirements, no significant differences in outcomes were observed between non-TNFi/JAKi and TNFi initiators.

During his presentation at the meeting, Dr. England posed the question: Are TNFi drugs safe to be used in RA-ILD?

“The answer is: It’s complex,” he said. “Our findings don’t suggest that we should be systematically avoiding TNFis with every single person with RA-ILD. But that’s different than whether there are specific subpopulations of RA-ILD for which the choice of these therapies may differ. Unfortunately, we could not address that in this study. We also could not address whether TNFis have efficacy at stopping, slowing, or reversing progression of the ILD itself. This calls for us as a field to gather together and pursue clinical trials to try to generate robust evidence that can guide these important clinical decisions that we’re making with our patients.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the analysis, including its observational design. “So, despite best efforts to minimize bias with pharmacoepidemiologic designs and approaches, there could still be confounding and selection,” he said. “Additionally, RA-ILD is a heterogeneous disease characterized by different patterns and trajectories. While we did account for several RA- and ILD-related factors, we could not account for all heterogeneity in RA-ILD.”

When asked for comment on the study, session moderator Janet Pope, MD, MPH, professor of medicine in the division of rheumatology at the University of Western Ontario, London, said that the study findings surprised her.

“Sometimes RA patients on TNFis were thought to have more new or worsening ILD vs. [those on] non-TNFi bDMARDs, but most [data were] from older studies where TNFis were used as initial bDMARD in sicker patients,” she told this news organization. “So, data were confounded previously. Even in this study, there may have been channeling bias as it was not a randomized controlled trial. We need a definitive randomized controlled trial to answer this question of what the most optimal therapy for RA-ILD is.”

Dr. England reports receiving consulting fees and research support from Boehringer Ingelheim, and several coauthors reported financial relationships from various pharmaceutical companies and medical publishers. Dr. Johnson reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Pope reports being a consultant for several pharmaceutical companies. She has received grant/research support from AbbVie/Abbott and Eli Lilly and is an adviser for Boehringer Ingelheim.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ACR 2023

Vasculitis confers higher risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes

SAN DIEGO – Pregnancy in patients with vasculitis had a higher risk for preterm delivery and preeclampsia/eclampsia – especially those with small-vessel vasculitis – compared with the general obstetric population, in a large analysis of administrative claims data presented at the American College of Rheumatology annual meeting.

“We suspect that there is a relationship between the increased risk of these serious hypertensive disorders and preterm delivery, given the higher risk of medically indicated preterm delivery,” one the of the study authors, Audra Horomanski, MD, said in an interview prior to her presentation in a plenary session at the meeting.

Limited data exist on the risks of pregnancy in patients with systemic vasculitis, according to Dr. Horomanski, a rheumatologist who directs the Stanford Vasculitis Clinic at Stanford (Calif.) University. “The majority of what we do know comes from relatively small cohort studies,” she said. “This is the first U.S., nationwide database study looking at the risk of preterm delivery and other adverse pregnancy outcomes.”

Drawing on administrative claims data from private health insurance providers, Dr. Horomanski and her colleagues identified all pregnancies regardless of outcome for patients with and without vasculitis from 2007 to 2021. They defined vasculitis as ≥ 2 ICD-coded outpatient visits or ≥ 1 ICD-coded inpatient visit occurring before the estimated last menstrual period (LMP), and they further categorized vasculitis by vessel size: large, medium, small, and variable, based on Chapel Hill Consensus Conference criteria. For a referent population, they included patients without vasculitis or other rheumatic disease, defined as no ICD-coded outpatient or inpatient visits for vasculitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis, or juvenile idiopathic arthritis before LMP or during pregnancy. Next, the researchers described pregnancy outcomes in patients with vasculitis compared with the referent population, and explored pregnancy characteristics and complications in patients with vasculitis stratified by parity (nulliparous vs. multiparous).

Dr. Horomanski reported results from 665 pregnancies in 527 patients with vasculitis and 4,209,034 pregnancies in 2,932,379 patients from the referent population. Patients with vasculitis had higher rates of spontaneous abortion (21% vs. 19%), elective termination (6% vs. 5%), ectopic and molar pregnancy (4% vs. 3%), and preterm delivery (13% vs. 6%). Approximately 12% of pregnancies among patients with vasculitis were complicated by preeclampsia. Multiparous pregnancies had a slightly higher frequency of preterm delivery than did nulliparous pregnancies (14% vs. 13%) and were more often comorbid with gestational diabetes (11% vs. 6%) and prepregnancy hypertension (23% vs. 13%). Patients with small-vessel vasculitis had higher frequencies of spontaneous abortion, preterm delivery, and comorbidities among vasculitis subtypes.

“I was surprised that vasculitis patients were less likely to be diagnosed with gestational hypertension compared to the general population, but more likely to be diagnosed with preeclampsia/eclampsia,” Dr. Horomanski added. “It raises questions about whether vasculitis patients are more likely to be diagnosed with more serious hypertensive disorders of pregnancy due to their underlying systemic disease or due to the perceptions of the treating clinicians.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it lacked information on race and ethnicity and was limited to privately insured individuals. This “suggests that we are likely missing patients with disabilities and those who are uninsured, both groups that may be at higher risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes,” she said. “We also have no information on disease activity or flare events which may contribute to these outcomes, particularly medically indicated preterm delivery. There is also a risk of misclassification due to the use of claims data and ICD coding. This misclassification may impact vasculitis diagnoses, parity, and early pregnancy losses.”

Despite the limitations, she said that the work “highlights the value of large database analysis as a complement to prior cohort studies to further clarify this complex picture. Overall, this information is valuable for the counseling of vasculitis patients considering pregnancy and for creating a plan to monitor for pregnancy complications.”

Lindsay S. Lally, MD, a rheumatologist with Hospital for Special Surgery in New York, who was asked to comment on the study, characterized the findings as “important in how many women with vasculitis and vasculitis pregnancies were identified. These data are a start at heightening our awareness about potential complications these women may experience during pregnancy. This study should help inform our family planning conversations with our vasculitis patients. Discussing potential reproductive risks, which are likely mediated by the disease itself, as well as the treatments that we prescribe, is important to help our vasculitis patients make informed decisions.”

Dr. Lally noted that an ongoing project through the Vasculitis Clinical Research Consortium includes a prospective registry of pregnant women with vasculitis, which asks pregnant patients to enter information throughout their pregnancy. “These studies will ultimately help optimize care of our vasculitis patients during pregnancy, ensuring the best outcomes for mother and baby,” she said.

Dr. Horomanski disclosed that she has received research support from Principia, BeiGene, Gilead, and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Lally reported having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO – Pregnancy in patients with vasculitis had a higher risk for preterm delivery and preeclampsia/eclampsia – especially those with small-vessel vasculitis – compared with the general obstetric population, in a large analysis of administrative claims data presented at the American College of Rheumatology annual meeting.

“We suspect that there is a relationship between the increased risk of these serious hypertensive disorders and preterm delivery, given the higher risk of medically indicated preterm delivery,” one the of the study authors, Audra Horomanski, MD, said in an interview prior to her presentation in a plenary session at the meeting.

Limited data exist on the risks of pregnancy in patients with systemic vasculitis, according to Dr. Horomanski, a rheumatologist who directs the Stanford Vasculitis Clinic at Stanford (Calif.) University. “The majority of what we do know comes from relatively small cohort studies,” she said. “This is the first U.S., nationwide database study looking at the risk of preterm delivery and other adverse pregnancy outcomes.”

Drawing on administrative claims data from private health insurance providers, Dr. Horomanski and her colleagues identified all pregnancies regardless of outcome for patients with and without vasculitis from 2007 to 2021. They defined vasculitis as ≥ 2 ICD-coded outpatient visits or ≥ 1 ICD-coded inpatient visit occurring before the estimated last menstrual period (LMP), and they further categorized vasculitis by vessel size: large, medium, small, and variable, based on Chapel Hill Consensus Conference criteria. For a referent population, they included patients without vasculitis or other rheumatic disease, defined as no ICD-coded outpatient or inpatient visits for vasculitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis, or juvenile idiopathic arthritis before LMP or during pregnancy. Next, the researchers described pregnancy outcomes in patients with vasculitis compared with the referent population, and explored pregnancy characteristics and complications in patients with vasculitis stratified by parity (nulliparous vs. multiparous).

Dr. Horomanski reported results from 665 pregnancies in 527 patients with vasculitis and 4,209,034 pregnancies in 2,932,379 patients from the referent population. Patients with vasculitis had higher rates of spontaneous abortion (21% vs. 19%), elective termination (6% vs. 5%), ectopic and molar pregnancy (4% vs. 3%), and preterm delivery (13% vs. 6%). Approximately 12% of pregnancies among patients with vasculitis were complicated by preeclampsia. Multiparous pregnancies had a slightly higher frequency of preterm delivery than did nulliparous pregnancies (14% vs. 13%) and were more often comorbid with gestational diabetes (11% vs. 6%) and prepregnancy hypertension (23% vs. 13%). Patients with small-vessel vasculitis had higher frequencies of spontaneous abortion, preterm delivery, and comorbidities among vasculitis subtypes.

“I was surprised that vasculitis patients were less likely to be diagnosed with gestational hypertension compared to the general population, but more likely to be diagnosed with preeclampsia/eclampsia,” Dr. Horomanski added. “It raises questions about whether vasculitis patients are more likely to be diagnosed with more serious hypertensive disorders of pregnancy due to their underlying systemic disease or due to the perceptions of the treating clinicians.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it lacked information on race and ethnicity and was limited to privately insured individuals. This “suggests that we are likely missing patients with disabilities and those who are uninsured, both groups that may be at higher risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes,” she said. “We also have no information on disease activity or flare events which may contribute to these outcomes, particularly medically indicated preterm delivery. There is also a risk of misclassification due to the use of claims data and ICD coding. This misclassification may impact vasculitis diagnoses, parity, and early pregnancy losses.”

Despite the limitations, she said that the work “highlights the value of large database analysis as a complement to prior cohort studies to further clarify this complex picture. Overall, this information is valuable for the counseling of vasculitis patients considering pregnancy and for creating a plan to monitor for pregnancy complications.”

Lindsay S. Lally, MD, a rheumatologist with Hospital for Special Surgery in New York, who was asked to comment on the study, characterized the findings as “important in how many women with vasculitis and vasculitis pregnancies were identified. These data are a start at heightening our awareness about potential complications these women may experience during pregnancy. This study should help inform our family planning conversations with our vasculitis patients. Discussing potential reproductive risks, which are likely mediated by the disease itself, as well as the treatments that we prescribe, is important to help our vasculitis patients make informed decisions.”

Dr. Lally noted that an ongoing project through the Vasculitis Clinical Research Consortium includes a prospective registry of pregnant women with vasculitis, which asks pregnant patients to enter information throughout their pregnancy. “These studies will ultimately help optimize care of our vasculitis patients during pregnancy, ensuring the best outcomes for mother and baby,” she said.

Dr. Horomanski disclosed that she has received research support from Principia, BeiGene, Gilead, and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Lally reported having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO – Pregnancy in patients with vasculitis had a higher risk for preterm delivery and preeclampsia/eclampsia – especially those with small-vessel vasculitis – compared with the general obstetric population, in a large analysis of administrative claims data presented at the American College of Rheumatology annual meeting.

“We suspect that there is a relationship between the increased risk of these serious hypertensive disorders and preterm delivery, given the higher risk of medically indicated preterm delivery,” one the of the study authors, Audra Horomanski, MD, said in an interview prior to her presentation in a plenary session at the meeting.

Limited data exist on the risks of pregnancy in patients with systemic vasculitis, according to Dr. Horomanski, a rheumatologist who directs the Stanford Vasculitis Clinic at Stanford (Calif.) University. “The majority of what we do know comes from relatively small cohort studies,” she said. “This is the first U.S., nationwide database study looking at the risk of preterm delivery and other adverse pregnancy outcomes.”

Drawing on administrative claims data from private health insurance providers, Dr. Horomanski and her colleagues identified all pregnancies regardless of outcome for patients with and without vasculitis from 2007 to 2021. They defined vasculitis as ≥ 2 ICD-coded outpatient visits or ≥ 1 ICD-coded inpatient visit occurring before the estimated last menstrual period (LMP), and they further categorized vasculitis by vessel size: large, medium, small, and variable, based on Chapel Hill Consensus Conference criteria. For a referent population, they included patients without vasculitis or other rheumatic disease, defined as no ICD-coded outpatient or inpatient visits for vasculitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis, or juvenile idiopathic arthritis before LMP or during pregnancy. Next, the researchers described pregnancy outcomes in patients with vasculitis compared with the referent population, and explored pregnancy characteristics and complications in patients with vasculitis stratified by parity (nulliparous vs. multiparous).

Dr. Horomanski reported results from 665 pregnancies in 527 patients with vasculitis and 4,209,034 pregnancies in 2,932,379 patients from the referent population. Patients with vasculitis had higher rates of spontaneous abortion (21% vs. 19%), elective termination (6% vs. 5%), ectopic and molar pregnancy (4% vs. 3%), and preterm delivery (13% vs. 6%). Approximately 12% of pregnancies among patients with vasculitis were complicated by preeclampsia. Multiparous pregnancies had a slightly higher frequency of preterm delivery than did nulliparous pregnancies (14% vs. 13%) and were more often comorbid with gestational diabetes (11% vs. 6%) and prepregnancy hypertension (23% vs. 13%). Patients with small-vessel vasculitis had higher frequencies of spontaneous abortion, preterm delivery, and comorbidities among vasculitis subtypes.

“I was surprised that vasculitis patients were less likely to be diagnosed with gestational hypertension compared to the general population, but more likely to be diagnosed with preeclampsia/eclampsia,” Dr. Horomanski added. “It raises questions about whether vasculitis patients are more likely to be diagnosed with more serious hypertensive disorders of pregnancy due to their underlying systemic disease or due to the perceptions of the treating clinicians.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including the fact that it lacked information on race and ethnicity and was limited to privately insured individuals. This “suggests that we are likely missing patients with disabilities and those who are uninsured, both groups that may be at higher risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes,” she said. “We also have no information on disease activity or flare events which may contribute to these outcomes, particularly medically indicated preterm delivery. There is also a risk of misclassification due to the use of claims data and ICD coding. This misclassification may impact vasculitis diagnoses, parity, and early pregnancy losses.”

Despite the limitations, she said that the work “highlights the value of large database analysis as a complement to prior cohort studies to further clarify this complex picture. Overall, this information is valuable for the counseling of vasculitis patients considering pregnancy and for creating a plan to monitor for pregnancy complications.”

Lindsay S. Lally, MD, a rheumatologist with Hospital for Special Surgery in New York, who was asked to comment on the study, characterized the findings as “important in how many women with vasculitis and vasculitis pregnancies were identified. These data are a start at heightening our awareness about potential complications these women may experience during pregnancy. This study should help inform our family planning conversations with our vasculitis patients. Discussing potential reproductive risks, which are likely mediated by the disease itself, as well as the treatments that we prescribe, is important to help our vasculitis patients make informed decisions.”

Dr. Lally noted that an ongoing project through the Vasculitis Clinical Research Consortium includes a prospective registry of pregnant women with vasculitis, which asks pregnant patients to enter information throughout their pregnancy. “These studies will ultimately help optimize care of our vasculitis patients during pregnancy, ensuring the best outcomes for mother and baby,” she said.

Dr. Horomanski disclosed that she has received research support from Principia, BeiGene, Gilead, and the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Lally reported having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ACR 2023

Apremilast beats placebo in early PsA affecting few joints

SAN DIEGO – Patients with early oligoarticular psoriatic arthritis (PsA) who took apremilast (Otezla) had more than double the response rate of placebo-treated patients by 16 weeks in a double-blind and randomized phase 4 study.

Oligoarticular PsA can significantly affect quality of life even though few joints are affected, and there’s a lack of relevant clinical data to guide treatment, said rheumatologist Philip J. Mease, MD, of the University of Washington and Swedish Medical Center, Seattle, who reported the results in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The findings of the study, called FOREMOST, support the use of the drug in mild PsA, Alexis Ogdie, MD, director of the Penn Psoriatic Arthritis Clinic and the Penn Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview. Dr. Ogdie, who was not involved with the research, noted that rheumatologists commonly prescribe apremilast for mild PsA, although previous research has focused on severe PsA cases.

By 16 weeks, 33.9% of 203 who received apremilast and 16% of 105 who received placebo (difference, 18.5%; 95% confidence interval, 8.9-28.1; P = .0008) met the trial’s primary outcome, a modified version of minimal disease activity score (MDA-Joints), which required attainment of 1 or fewer swollen and/or tender joints plus three of five additional criteria (psoriasis body surface area of 3% or less, a patient pain visual analog scale assessment of 15 mm or less out of 0-100 mm, a patient global assessment of 20 mm or less out of 0-100 mm, a Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index score of 0.5 or less, and a Leeds Enthesitis Index score of 1 or less). The primary analysis was conducted only in joints affected at baseline.

The researchers recruited patients with 2-4 swollen and/or tender joints out of a total of 66-68 joints assessed; most patients (87%) randomized in the study had 4 or fewer active joints at baseline. The patients had a mean age of 50.9. The mean duration of PsA was 9.9 months, and 39.9% of patients were taking a conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drug.

In a clinically important outcome, the percentage who had a patient-reported pain response improvement defined as “significant” reached 31.4% with placebo, compared with 48.8% for apremilast (difference, 17.7%; 95% CI, 6.0-29.4; P = .0044), and the percentage who reached a patient-reported pain response defined as “major” totaled 19.1% for placebo vs. 41.3% for apremilast (difference, 22.3%; 95% CI, 11.7-32.9; P = .002).

In an exploratory analysis of all joints, the percentages meeting MDA-Joints criteria for response were 7.9% with placebo and 21.3% with apremilast (difference, 13.6%; 95% CI, 5.9-21.4; P = .0028. Focusing on this exploratory analysis, Dr. Ogdie noted that examination of all joints is “more consistent” with the understanding of disease activity than only looking at the initial joints that had disease activity.

A post-hoc analysis among subjects with 2-4 affected joints found rates similar to the primary endpoint analysis: MDA-Joints response rates were reached by 34.4% of those who took apremilast and by 17.2% of those who took placebo.

When asked about the relatively low response rate for apremilast, Dr. Ogdie said the drug is “a really mild medication, which is why it belongs in the mild disease population. That’s balanced by the fact that it has a pretty good safety profile,” especially compared with the alternative of methotrexate, she said.

Almost all patients can tolerate apremilast, she said, although they may experience nausea or diarrhea. (The study found that adverse events were as expected for apremilast, and the drug was well tolerated.) Blood labs aren’t necessary, she added, as they are in patients taking methotrexate.

As for cost, apremilast is a highly expensive drug, especially when compared to methotrexate, which costs pennies per tablet at some pharmacies. Amgen, the manufacturer of apremilast, lists the price as $4,600 a month. Still, insurers generally cover apremilast, Dr. Ogdie said.

The study was sponsored by Amgen. Dr. Mease reported financial relationships with many pharmaceutical companies, including Amgen. Many other coauthors reported financial relationships with Amgen and other pharmaceutical companies or were employees of Amgen. Dr. Ogdie reported having multiple consulting relationships with pharmaceutical companies, including Amgen, and receiving grant funding from multiple companies as well as the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Psoriasis Foundation, Rheumatology Research Foundation, and Forward Databank.

SAN DIEGO – Patients with early oligoarticular psoriatic arthritis (PsA) who took apremilast (Otezla) had more than double the response rate of placebo-treated patients by 16 weeks in a double-blind and randomized phase 4 study.

Oligoarticular PsA can significantly affect quality of life even though few joints are affected, and there’s a lack of relevant clinical data to guide treatment, said rheumatologist Philip J. Mease, MD, of the University of Washington and Swedish Medical Center, Seattle, who reported the results in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The findings of the study, called FOREMOST, support the use of the drug in mild PsA, Alexis Ogdie, MD, director of the Penn Psoriatic Arthritis Clinic and the Penn Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview. Dr. Ogdie, who was not involved with the research, noted that rheumatologists commonly prescribe apremilast for mild PsA, although previous research has focused on severe PsA cases.

By 16 weeks, 33.9% of 203 who received apremilast and 16% of 105 who received placebo (difference, 18.5%; 95% confidence interval, 8.9-28.1; P = .0008) met the trial’s primary outcome, a modified version of minimal disease activity score (MDA-Joints), which required attainment of 1 or fewer swollen and/or tender joints plus three of five additional criteria (psoriasis body surface area of 3% or less, a patient pain visual analog scale assessment of 15 mm or less out of 0-100 mm, a patient global assessment of 20 mm or less out of 0-100 mm, a Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index score of 0.5 or less, and a Leeds Enthesitis Index score of 1 or less). The primary analysis was conducted only in joints affected at baseline.

The researchers recruited patients with 2-4 swollen and/or tender joints out of a total of 66-68 joints assessed; most patients (87%) randomized in the study had 4 or fewer active joints at baseline. The patients had a mean age of 50.9. The mean duration of PsA was 9.9 months, and 39.9% of patients were taking a conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drug.

In a clinically important outcome, the percentage who had a patient-reported pain response improvement defined as “significant” reached 31.4% with placebo, compared with 48.8% for apremilast (difference, 17.7%; 95% CI, 6.0-29.4; P = .0044), and the percentage who reached a patient-reported pain response defined as “major” totaled 19.1% for placebo vs. 41.3% for apremilast (difference, 22.3%; 95% CI, 11.7-32.9; P = .002).

In an exploratory analysis of all joints, the percentages meeting MDA-Joints criteria for response were 7.9% with placebo and 21.3% with apremilast (difference, 13.6%; 95% CI, 5.9-21.4; P = .0028. Focusing on this exploratory analysis, Dr. Ogdie noted that examination of all joints is “more consistent” with the understanding of disease activity than only looking at the initial joints that had disease activity.

A post-hoc analysis among subjects with 2-4 affected joints found rates similar to the primary endpoint analysis: MDA-Joints response rates were reached by 34.4% of those who took apremilast and by 17.2% of those who took placebo.

When asked about the relatively low response rate for apremilast, Dr. Ogdie said the drug is “a really mild medication, which is why it belongs in the mild disease population. That’s balanced by the fact that it has a pretty good safety profile,” especially compared with the alternative of methotrexate, she said.

Almost all patients can tolerate apremilast, she said, although they may experience nausea or diarrhea. (The study found that adverse events were as expected for apremilast, and the drug was well tolerated.) Blood labs aren’t necessary, she added, as they are in patients taking methotrexate.

As for cost, apremilast is a highly expensive drug, especially when compared to methotrexate, which costs pennies per tablet at some pharmacies. Amgen, the manufacturer of apremilast, lists the price as $4,600 a month. Still, insurers generally cover apremilast, Dr. Ogdie said.

The study was sponsored by Amgen. Dr. Mease reported financial relationships with many pharmaceutical companies, including Amgen. Many other coauthors reported financial relationships with Amgen and other pharmaceutical companies or were employees of Amgen. Dr. Ogdie reported having multiple consulting relationships with pharmaceutical companies, including Amgen, and receiving grant funding from multiple companies as well as the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Psoriasis Foundation, Rheumatology Research Foundation, and Forward Databank.

SAN DIEGO – Patients with early oligoarticular psoriatic arthritis (PsA) who took apremilast (Otezla) had more than double the response rate of placebo-treated patients by 16 weeks in a double-blind and randomized phase 4 study.

Oligoarticular PsA can significantly affect quality of life even though few joints are affected, and there’s a lack of relevant clinical data to guide treatment, said rheumatologist Philip J. Mease, MD, of the University of Washington and Swedish Medical Center, Seattle, who reported the results in a presentation at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

The findings of the study, called FOREMOST, support the use of the drug in mild PsA, Alexis Ogdie, MD, director of the Penn Psoriatic Arthritis Clinic and the Penn Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview. Dr. Ogdie, who was not involved with the research, noted that rheumatologists commonly prescribe apremilast for mild PsA, although previous research has focused on severe PsA cases.

By 16 weeks, 33.9% of 203 who received apremilast and 16% of 105 who received placebo (difference, 18.5%; 95% confidence interval, 8.9-28.1; P = .0008) met the trial’s primary outcome, a modified version of minimal disease activity score (MDA-Joints), which required attainment of 1 or fewer swollen and/or tender joints plus three of five additional criteria (psoriasis body surface area of 3% or less, a patient pain visual analog scale assessment of 15 mm or less out of 0-100 mm, a patient global assessment of 20 mm or less out of 0-100 mm, a Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index score of 0.5 or less, and a Leeds Enthesitis Index score of 1 or less). The primary analysis was conducted only in joints affected at baseline.

The researchers recruited patients with 2-4 swollen and/or tender joints out of a total of 66-68 joints assessed; most patients (87%) randomized in the study had 4 or fewer active joints at baseline. The patients had a mean age of 50.9. The mean duration of PsA was 9.9 months, and 39.9% of patients were taking a conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drug.

In a clinically important outcome, the percentage who had a patient-reported pain response improvement defined as “significant” reached 31.4% with placebo, compared with 48.8% for apremilast (difference, 17.7%; 95% CI, 6.0-29.4; P = .0044), and the percentage who reached a patient-reported pain response defined as “major” totaled 19.1% for placebo vs. 41.3% for apremilast (difference, 22.3%; 95% CI, 11.7-32.9; P = .002).

In an exploratory analysis of all joints, the percentages meeting MDA-Joints criteria for response were 7.9% with placebo and 21.3% with apremilast (difference, 13.6%; 95% CI, 5.9-21.4; P = .0028. Focusing on this exploratory analysis, Dr. Ogdie noted that examination of all joints is “more consistent” with the understanding of disease activity than only looking at the initial joints that had disease activity.

A post-hoc analysis among subjects with 2-4 affected joints found rates similar to the primary endpoint analysis: MDA-Joints response rates were reached by 34.4% of those who took apremilast and by 17.2% of those who took placebo.

When asked about the relatively low response rate for apremilast, Dr. Ogdie said the drug is “a really mild medication, which is why it belongs in the mild disease population. That’s balanced by the fact that it has a pretty good safety profile,” especially compared with the alternative of methotrexate, she said.

Almost all patients can tolerate apremilast, she said, although they may experience nausea or diarrhea. (The study found that adverse events were as expected for apremilast, and the drug was well tolerated.) Blood labs aren’t necessary, she added, as they are in patients taking methotrexate.

As for cost, apremilast is a highly expensive drug, especially when compared to methotrexate, which costs pennies per tablet at some pharmacies. Amgen, the manufacturer of apremilast, lists the price as $4,600 a month. Still, insurers generally cover apremilast, Dr. Ogdie said.

The study was sponsored by Amgen. Dr. Mease reported financial relationships with many pharmaceutical companies, including Amgen. Many other coauthors reported financial relationships with Amgen and other pharmaceutical companies or were employees of Amgen. Dr. Ogdie reported having multiple consulting relationships with pharmaceutical companies, including Amgen, and receiving grant funding from multiple companies as well as the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Psoriasis Foundation, Rheumatology Research Foundation, and Forward Databank.

AT ACR 2023

TNF blockers not associated with poorer pregnancy outcomes

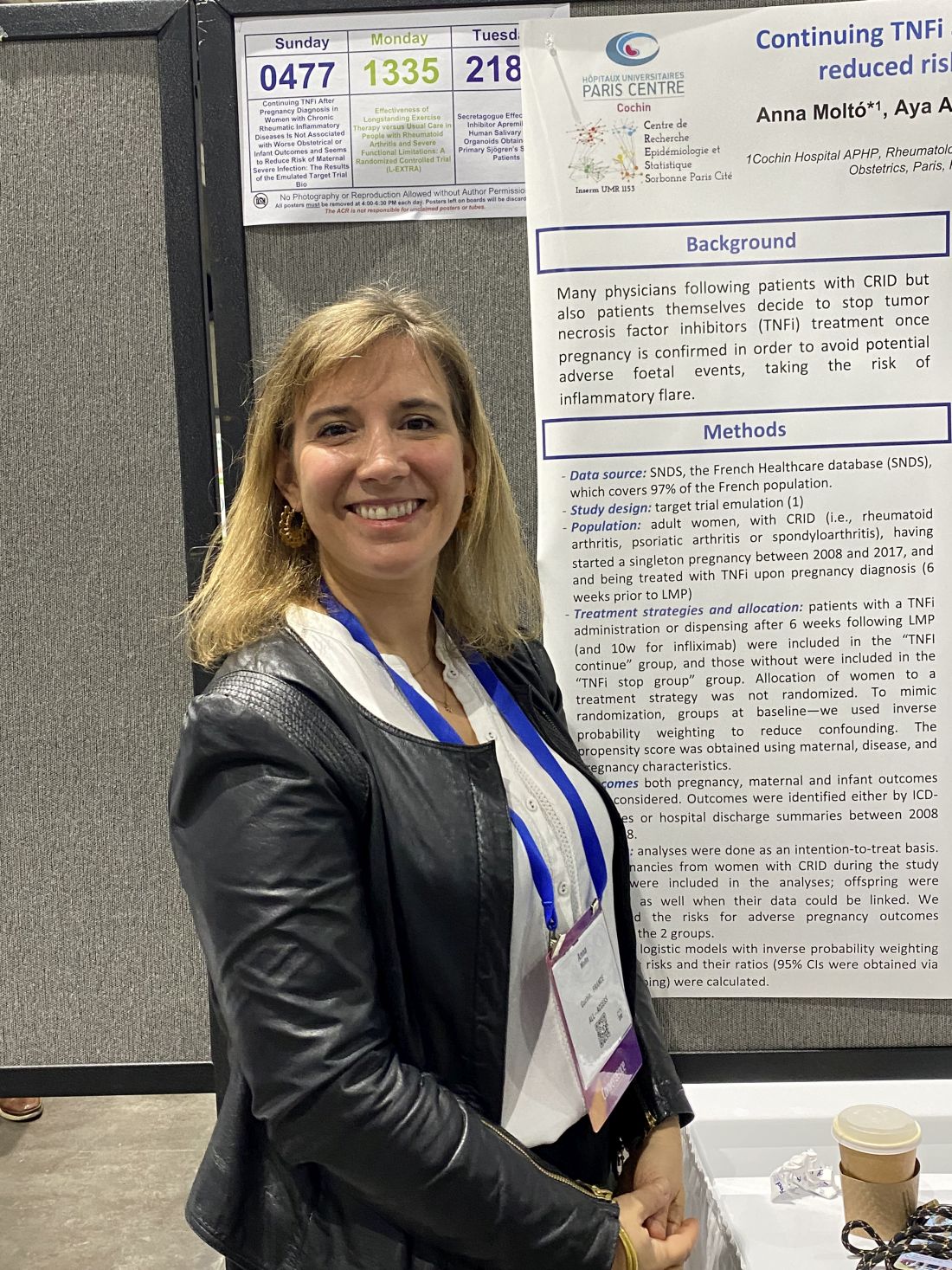

SAN DIEGO – Continuing a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) during pregnancy does not increase risk of worse fetal or obstetric outcomes, according to new research presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Patients who continued a TNFi also had fewer severe infections requiring hospitalization, compared with those who stopped taking the medication during their pregnancy.

“The main message is that patients continuing were not doing worse than the patients stopping. It’s an important clinical message for rheumatologists who are not really confident in dealing with these drugs during pregnancy,” said Anna Moltó, MD, PhD, a rheumatologist at Cochin Hospital, Paris, who led the research. “It adds to the data that it seems to be safe,” she added in an interview.