User login

Post-Hospital Syndrome Contributes to Readmission Risk for Elderly

Post-hospital syndrome, as labeled in a recent, widely publicized opinion piece in the New England Journal of Medicine, is not a new concept, according to one hospitalist pioneer.1

Harlan Krumholz, MD, of the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn., writes in NEJM what others previously have described as “hospitalization-associated disability,” says Mark Williams, MD, MHM, chief of hospital medicine at Northwestern University School of Medicine and principal investigator of SHM’s Project BOOST (www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost).2

Dr. Krumholz found that the majority of 30-day readmissions for elderly patients with heart failure, pneumonia, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are for conditions other than the diagnosis named at discharge. He attributes this phenomenon to hospitalization-related sleep deprivation, malnourishment, pain and discomfort, cognition- and physical function-altering medications, deconditioning from bed rest or inactivity, and the experience of confronting stressful, mentally challenging situations in the hospital.1 Such stressors leave elderly patients with post-hospitalization disabilities comparable to a bad case of jet lag.

For Dr. Williams, the physical deterioration leading to rehospitalizations is better attributed to the underlying serious illness and comorbidities experienced by elderly patients—a kind of high-risk, post-illness syndrome. Prior research also has demonstrated the effects of bed rest for hospitalized elderly patients.

Regardless of the origins, is there anything hospitalists can do about this syndrome? “Absolutely,” Dr. Williams says. “Get elderly, hospitalized patients out of bed as quickly as possible, and be mindful of medications and their effects on elderly patients. But most hospitalists already think about these things when managing elderly patients.”

References

Post-hospital syndrome, as labeled in a recent, widely publicized opinion piece in the New England Journal of Medicine, is not a new concept, according to one hospitalist pioneer.1

Harlan Krumholz, MD, of the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn., writes in NEJM what others previously have described as “hospitalization-associated disability,” says Mark Williams, MD, MHM, chief of hospital medicine at Northwestern University School of Medicine and principal investigator of SHM’s Project BOOST (www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost).2

Dr. Krumholz found that the majority of 30-day readmissions for elderly patients with heart failure, pneumonia, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are for conditions other than the diagnosis named at discharge. He attributes this phenomenon to hospitalization-related sleep deprivation, malnourishment, pain and discomfort, cognition- and physical function-altering medications, deconditioning from bed rest or inactivity, and the experience of confronting stressful, mentally challenging situations in the hospital.1 Such stressors leave elderly patients with post-hospitalization disabilities comparable to a bad case of jet lag.

For Dr. Williams, the physical deterioration leading to rehospitalizations is better attributed to the underlying serious illness and comorbidities experienced by elderly patients—a kind of high-risk, post-illness syndrome. Prior research also has demonstrated the effects of bed rest for hospitalized elderly patients.

Regardless of the origins, is there anything hospitalists can do about this syndrome? “Absolutely,” Dr. Williams says. “Get elderly, hospitalized patients out of bed as quickly as possible, and be mindful of medications and their effects on elderly patients. But most hospitalists already think about these things when managing elderly patients.”

References

Post-hospital syndrome, as labeled in a recent, widely publicized opinion piece in the New England Journal of Medicine, is not a new concept, according to one hospitalist pioneer.1

Harlan Krumholz, MD, of the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn., writes in NEJM what others previously have described as “hospitalization-associated disability,” says Mark Williams, MD, MHM, chief of hospital medicine at Northwestern University School of Medicine and principal investigator of SHM’s Project BOOST (www.hospitalmedicine.org/boost).2

Dr. Krumholz found that the majority of 30-day readmissions for elderly patients with heart failure, pneumonia, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are for conditions other than the diagnosis named at discharge. He attributes this phenomenon to hospitalization-related sleep deprivation, malnourishment, pain and discomfort, cognition- and physical function-altering medications, deconditioning from bed rest or inactivity, and the experience of confronting stressful, mentally challenging situations in the hospital.1 Such stressors leave elderly patients with post-hospitalization disabilities comparable to a bad case of jet lag.

For Dr. Williams, the physical deterioration leading to rehospitalizations is better attributed to the underlying serious illness and comorbidities experienced by elderly patients—a kind of high-risk, post-illness syndrome. Prior research also has demonstrated the effects of bed rest for hospitalized elderly patients.

Regardless of the origins, is there anything hospitalists can do about this syndrome? “Absolutely,” Dr. Williams says. “Get elderly, hospitalized patients out of bed as quickly as possible, and be mindful of medications and their effects on elderly patients. But most hospitalists already think about these things when managing elderly patients.”

References

Houston Hospitalists Create Direct-Admit System

Two hospitalists in the greater Houston area have developed a computer application that streamlines the hospital admission process—a major frustration for busy, office-based primary-care physicians (PCPs).

Mujtaba Ali-Khan, DO, who has practiced at Conroe Regional Medical Center since 2009, is president of Streamlined Medical Solutions (www.streamlinedmedical.com), a company incorporated in July 2011 to market the Direct Admit System for Hospitals, or DASH.1 DASH allows referring physicians to access and submit a direct-admit form, upload medical records, and order preliminary medications and tests for the patient. Once the on-call hospitalist accepts the submitted referral, a “boarding pass” with assigned hospitalist and room number is generated for the patient to take to the hospital’s admissions department. Patients bypass the ED and avoid duplicative medical tests. The process also sends a confirmation to the PCP.

With the support of Hospital Corporation of America (HCA), Dr. Ali-Khan and his business partner, hospitalist Ali Bhuriwala, MD, piloted DASH at two HCA hospitals in Texas. It’s now on the market and has been implemented or is in the works at several others.

“When we started using DASH, we found ourselves getting all sorts of data: Who are the referring physicians, the patients’ ZIP codes, how long do admissions take?” says Dr. Ali-Khan, who adds plans are under way to expand the software’s capacity to allow PCPs to upload tests and place medical orders from the field. “We’re also developing a full suite of hospitalist communication and coordination functions on a dashboard, accessible from smartphones and text alerts, dispensing with pagers entirely.”

Watch a video about DASH at www.youtube.com/watch?v=HUG_vQgKvE0.

Reference

Two hospitalists in the greater Houston area have developed a computer application that streamlines the hospital admission process—a major frustration for busy, office-based primary-care physicians (PCPs).

Mujtaba Ali-Khan, DO, who has practiced at Conroe Regional Medical Center since 2009, is president of Streamlined Medical Solutions (www.streamlinedmedical.com), a company incorporated in July 2011 to market the Direct Admit System for Hospitals, or DASH.1 DASH allows referring physicians to access and submit a direct-admit form, upload medical records, and order preliminary medications and tests for the patient. Once the on-call hospitalist accepts the submitted referral, a “boarding pass” with assigned hospitalist and room number is generated for the patient to take to the hospital’s admissions department. Patients bypass the ED and avoid duplicative medical tests. The process also sends a confirmation to the PCP.

With the support of Hospital Corporation of America (HCA), Dr. Ali-Khan and his business partner, hospitalist Ali Bhuriwala, MD, piloted DASH at two HCA hospitals in Texas. It’s now on the market and has been implemented or is in the works at several others.

“When we started using DASH, we found ourselves getting all sorts of data: Who are the referring physicians, the patients’ ZIP codes, how long do admissions take?” says Dr. Ali-Khan, who adds plans are under way to expand the software’s capacity to allow PCPs to upload tests and place medical orders from the field. “We’re also developing a full suite of hospitalist communication and coordination functions on a dashboard, accessible from smartphones and text alerts, dispensing with pagers entirely.”

Watch a video about DASH at www.youtube.com/watch?v=HUG_vQgKvE0.

Reference

Two hospitalists in the greater Houston area have developed a computer application that streamlines the hospital admission process—a major frustration for busy, office-based primary-care physicians (PCPs).

Mujtaba Ali-Khan, DO, who has practiced at Conroe Regional Medical Center since 2009, is president of Streamlined Medical Solutions (www.streamlinedmedical.com), a company incorporated in July 2011 to market the Direct Admit System for Hospitals, or DASH.1 DASH allows referring physicians to access and submit a direct-admit form, upload medical records, and order preliminary medications and tests for the patient. Once the on-call hospitalist accepts the submitted referral, a “boarding pass” with assigned hospitalist and room number is generated for the patient to take to the hospital’s admissions department. Patients bypass the ED and avoid duplicative medical tests. The process also sends a confirmation to the PCP.

With the support of Hospital Corporation of America (HCA), Dr. Ali-Khan and his business partner, hospitalist Ali Bhuriwala, MD, piloted DASH at two HCA hospitals in Texas. It’s now on the market and has been implemented or is in the works at several others.

“When we started using DASH, we found ourselves getting all sorts of data: Who are the referring physicians, the patients’ ZIP codes, how long do admissions take?” says Dr. Ali-Khan, who adds plans are under way to expand the software’s capacity to allow PCPs to upload tests and place medical orders from the field. “We’re also developing a full suite of hospitalist communication and coordination functions on a dashboard, accessible from smartphones and text alerts, dispensing with pagers entirely.”

Watch a video about DASH at www.youtube.com/watch?v=HUG_vQgKvE0.

Reference

Win Whitcomb: Mortality Rates Become a Measuring Stick for Hospital Performance

—Blue Oyster Cult

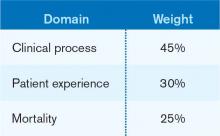

The designers of the hospital value-based purchasing (HVBP) program sought to include outcomes measures in 2014, and when they did, mortality was their choice. Specifically, HVBP for fiscal-year 2014 (starting October 2013) will include 30-day mortality rates for myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia. The weighting for the mortality domain will be 25% (see Table 1).

To review the requirements for the HVBP program in FY2014: All hospitals will have 1.25% of their Medicare inpatient payments withheld. They can earn back none, some, all, or an amount in excess of the 1.25%, depending on performance in the performance domains. To put it in perspective, 1.25% of Medicare inpatient payments for a 320-bed hospital are about $1 million. Such a hospital will have about $250,000 at risk in the mortality domain in FY2014.

Given the role hospitalists play in quality and safety initiatives, and the importance of medical record documentation in defining the risk of mortality and severity of illness, we can be crucial players in how our hospitals perform with regard to mortality.

Focus Areas for Mortality Reduction

Although many hospitalists might think that reducing mortality is like “boiling the ocean,” there are some areas where we can clearly focus our attention. There are four priority areas we should target in the coming years (also see Figure 1):

Reduce harm. This may take the form of reducing hospital-acquired infections, such as catheter-related UTIs, Clostridium difficile, and central-line-associated bloodstream infections, or reducing hospital-acquired VTE, falls, and delirium. Many hospital-acquired conditions have a collection, or bundle, of preventive practices. Hospitalists can work both in an institutional leadership capacity and in the course of daily clinical practice to implement bundles and best practices to reduce patient harm.

Improve teamwork. With hospitalists, “you started to have teams caring for inpatients in a coordinated way. So I regard this as [hospitalists] coming into their own, their vision of the future starting to really take hold,” said Brent James, coauthor of the recent Institute of Medicine report “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Partly, we’ve accomplished this through simply “showing up” and partly we’ve done it through becoming students of the art and science of teamwork. An example of teamwork training, developed by the Defense Department and the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ), is TeamSTEPPS, which offers a systematic approach to cooperation, coordination, and communication among team members. Optimal patient resuscitation, in-hospital handoffs, rapid-response teams, and early-warning systems are essential pieces of teamwork that may reduce mortality.

Improve evidence-based care. This domain covers process measures aimed at optimizing care, including reducing mortality. For HVBP in particular, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia are the focus.

Improve transitions of care. Best practices for care transitions and reducing readmissions, including advance-care planning, involvement of palliative care and hospice, and coordination with post-acute care, can be a key part of reducing 30-day mortality.

Documentation Integrity

Accurately capturing a patient’s condition in the medical record is crucial to assigning severity of illness and risk of mortality. Because mortality rates are severity-adjusted, accurate documentation is another important dimension to potentially improving a hospital’s performance with regard to the mortality domain. This is one more reason to work closely with your hospital’s documentation specialists.

Don’t Be Afraid...

Proponents of mortality as a quality measure point to it as the ultimate reflection of the care provided. While moving the needle might seem like a task too big to undertake, a disciplined approach to the elements of the driver diagram combined with a robust documentation program can provide your institution with a tangible focus on this definitive measure.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

—Blue Oyster Cult

The designers of the hospital value-based purchasing (HVBP) program sought to include outcomes measures in 2014, and when they did, mortality was their choice. Specifically, HVBP for fiscal-year 2014 (starting October 2013) will include 30-day mortality rates for myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia. The weighting for the mortality domain will be 25% (see Table 1).

To review the requirements for the HVBP program in FY2014: All hospitals will have 1.25% of their Medicare inpatient payments withheld. They can earn back none, some, all, or an amount in excess of the 1.25%, depending on performance in the performance domains. To put it in perspective, 1.25% of Medicare inpatient payments for a 320-bed hospital are about $1 million. Such a hospital will have about $250,000 at risk in the mortality domain in FY2014.

Given the role hospitalists play in quality and safety initiatives, and the importance of medical record documentation in defining the risk of mortality and severity of illness, we can be crucial players in how our hospitals perform with regard to mortality.

Focus Areas for Mortality Reduction

Although many hospitalists might think that reducing mortality is like “boiling the ocean,” there are some areas where we can clearly focus our attention. There are four priority areas we should target in the coming years (also see Figure 1):

Reduce harm. This may take the form of reducing hospital-acquired infections, such as catheter-related UTIs, Clostridium difficile, and central-line-associated bloodstream infections, or reducing hospital-acquired VTE, falls, and delirium. Many hospital-acquired conditions have a collection, or bundle, of preventive practices. Hospitalists can work both in an institutional leadership capacity and in the course of daily clinical practice to implement bundles and best practices to reduce patient harm.

Improve teamwork. With hospitalists, “you started to have teams caring for inpatients in a coordinated way. So I regard this as [hospitalists] coming into their own, their vision of the future starting to really take hold,” said Brent James, coauthor of the recent Institute of Medicine report “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Partly, we’ve accomplished this through simply “showing up” and partly we’ve done it through becoming students of the art and science of teamwork. An example of teamwork training, developed by the Defense Department and the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ), is TeamSTEPPS, which offers a systematic approach to cooperation, coordination, and communication among team members. Optimal patient resuscitation, in-hospital handoffs, rapid-response teams, and early-warning systems are essential pieces of teamwork that may reduce mortality.

Improve evidence-based care. This domain covers process measures aimed at optimizing care, including reducing mortality. For HVBP in particular, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia are the focus.

Improve transitions of care. Best practices for care transitions and reducing readmissions, including advance-care planning, involvement of palliative care and hospice, and coordination with post-acute care, can be a key part of reducing 30-day mortality.

Documentation Integrity

Accurately capturing a patient’s condition in the medical record is crucial to assigning severity of illness and risk of mortality. Because mortality rates are severity-adjusted, accurate documentation is another important dimension to potentially improving a hospital’s performance with regard to the mortality domain. This is one more reason to work closely with your hospital’s documentation specialists.

Don’t Be Afraid...

Proponents of mortality as a quality measure point to it as the ultimate reflection of the care provided. While moving the needle might seem like a task too big to undertake, a disciplined approach to the elements of the driver diagram combined with a robust documentation program can provide your institution with a tangible focus on this definitive measure.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

—Blue Oyster Cult

The designers of the hospital value-based purchasing (HVBP) program sought to include outcomes measures in 2014, and when they did, mortality was their choice. Specifically, HVBP for fiscal-year 2014 (starting October 2013) will include 30-day mortality rates for myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia. The weighting for the mortality domain will be 25% (see Table 1).

To review the requirements for the HVBP program in FY2014: All hospitals will have 1.25% of their Medicare inpatient payments withheld. They can earn back none, some, all, or an amount in excess of the 1.25%, depending on performance in the performance domains. To put it in perspective, 1.25% of Medicare inpatient payments for a 320-bed hospital are about $1 million. Such a hospital will have about $250,000 at risk in the mortality domain in FY2014.

Given the role hospitalists play in quality and safety initiatives, and the importance of medical record documentation in defining the risk of mortality and severity of illness, we can be crucial players in how our hospitals perform with regard to mortality.

Focus Areas for Mortality Reduction

Although many hospitalists might think that reducing mortality is like “boiling the ocean,” there are some areas where we can clearly focus our attention. There are four priority areas we should target in the coming years (also see Figure 1):

Reduce harm. This may take the form of reducing hospital-acquired infections, such as catheter-related UTIs, Clostridium difficile, and central-line-associated bloodstream infections, or reducing hospital-acquired VTE, falls, and delirium. Many hospital-acquired conditions have a collection, or bundle, of preventive practices. Hospitalists can work both in an institutional leadership capacity and in the course of daily clinical practice to implement bundles and best practices to reduce patient harm.

Improve teamwork. With hospitalists, “you started to have teams caring for inpatients in a coordinated way. So I regard this as [hospitalists] coming into their own, their vision of the future starting to really take hold,” said Brent James, coauthor of the recent Institute of Medicine report “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Partly, we’ve accomplished this through simply “showing up” and partly we’ve done it through becoming students of the art and science of teamwork. An example of teamwork training, developed by the Defense Department and the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (AHRQ), is TeamSTEPPS, which offers a systematic approach to cooperation, coordination, and communication among team members. Optimal patient resuscitation, in-hospital handoffs, rapid-response teams, and early-warning systems are essential pieces of teamwork that may reduce mortality.

Improve evidence-based care. This domain covers process measures aimed at optimizing care, including reducing mortality. For HVBP in particular, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia are the focus.

Improve transitions of care. Best practices for care transitions and reducing readmissions, including advance-care planning, involvement of palliative care and hospice, and coordination with post-acute care, can be a key part of reducing 30-day mortality.

Documentation Integrity

Accurately capturing a patient’s condition in the medical record is crucial to assigning severity of illness and risk of mortality. Because mortality rates are severity-adjusted, accurate documentation is another important dimension to potentially improving a hospital’s performance with regard to the mortality domain. This is one more reason to work closely with your hospital’s documentation specialists.

Don’t Be Afraid...

Proponents of mortality as a quality measure point to it as the ultimate reflection of the care provided. While moving the needle might seem like a task too big to undertake, a disciplined approach to the elements of the driver diagram combined with a robust documentation program can provide your institution with a tangible focus on this definitive measure.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

Multidisciplinary Palliative-Care Consults Help Reduce Hospital Readmissions

Research on seriously ill, hospitalized, Medicare-age patients finds that those who received inpatient consultations from a multidisciplinary, palliative-care team (including a physician, nurse, and social worker) had lower 30-day hospital readmission rates.1 Ten percent of discharged patients who received the palliative-care consult were readmitted within 30 days at an urban HMO medical center in Los Angeles County during the same period, even though they were sicker than the overall discharged population.

Receipt of hospice care or home-based palliative-care services following discharge was also associated with significantly lower rates of readmissions, suggesting opportunities for systemic cost savings from earlier access to longitudinal, or ongoing, palliative-care services, says Susan Enguidanos, MPH, PhD, assistant professor of gerontology at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. Patients discharged from the hospital without any follow-up care in the home had higher odds of readmission.

“Hospitals and medical centers should seriously consider an inpatient palliative care consultation team for many reasons, mostly arising from findings from other studies that have demonstrated improved quality of life, pain and symptom management, satisfaction with medical care, and other promising outcomes,” Dr. Enguidanos says. “Our study suggests that longitudinal palliative care is also associated with the lower readmission rate.”

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

Research on seriously ill, hospitalized, Medicare-age patients finds that those who received inpatient consultations from a multidisciplinary, palliative-care team (including a physician, nurse, and social worker) had lower 30-day hospital readmission rates.1 Ten percent of discharged patients who received the palliative-care consult were readmitted within 30 days at an urban HMO medical center in Los Angeles County during the same period, even though they were sicker than the overall discharged population.

Receipt of hospice care or home-based palliative-care services following discharge was also associated with significantly lower rates of readmissions, suggesting opportunities for systemic cost savings from earlier access to longitudinal, or ongoing, palliative-care services, says Susan Enguidanos, MPH, PhD, assistant professor of gerontology at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. Patients discharged from the hospital without any follow-up care in the home had higher odds of readmission.

“Hospitals and medical centers should seriously consider an inpatient palliative care consultation team for many reasons, mostly arising from findings from other studies that have demonstrated improved quality of life, pain and symptom management, satisfaction with medical care, and other promising outcomes,” Dr. Enguidanos says. “Our study suggests that longitudinal palliative care is also associated with the lower readmission rate.”

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

Research on seriously ill, hospitalized, Medicare-age patients finds that those who received inpatient consultations from a multidisciplinary, palliative-care team (including a physician, nurse, and social worker) had lower 30-day hospital readmission rates.1 Ten percent of discharged patients who received the palliative-care consult were readmitted within 30 days at an urban HMO medical center in Los Angeles County during the same period, even though they were sicker than the overall discharged population.

Receipt of hospice care or home-based palliative-care services following discharge was also associated with significantly lower rates of readmissions, suggesting opportunities for systemic cost savings from earlier access to longitudinal, or ongoing, palliative-care services, says Susan Enguidanos, MPH, PhD, assistant professor of gerontology at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. Patients discharged from the hospital without any follow-up care in the home had higher odds of readmission.

“Hospitals and medical centers should seriously consider an inpatient palliative care consultation team for many reasons, mostly arising from findings from other studies that have demonstrated improved quality of life, pain and symptom management, satisfaction with medical care, and other promising outcomes,” Dr. Enguidanos says. “Our study suggests that longitudinal palliative care is also associated with the lower readmission rate.”

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

Cardiologists Help Lower Readmission Rates for Hospitalized Heart Failure Patients

Data reported at the American Heart Association’s scientific sessions in Los Angeles in November suggest that when a cardiologist, rather than a hospitalist, is the attending physician for a hospitalized heart failure patient, readmission is less likely. Casey M. Lawler, MD, FACC, a cardiologist at the Minneapolis Heart Institute, says her center began establishing protocols to improve heart failure readmissions rates five years ago, after determining that many patients did not understand their diagnosis or treatment. “Thus, we became much more involved in post-discharge care,” including the phoning of discharged patients and follow-up with primary-care providers.

When the heart failure patients’ attending physicians were cardiologists, their readmission rate was 16%, versus 27.1% with hospitalists, even though their severity of illness was higher. Length of stay was similar for both groups and total mean costs were higher for the patients managed by cardiologists. “Although these results reveal that specialists have a positive impact on readmission rates, an overhaul to an entire healthcare system’s treatment of [heart failure] patients—from admission to post-discharge follow-up—is required to truly impact preventable readmissions,” Dr. Lawler asserted.

In the Minneapolis study, 65% of the 2,300 heart failure patients were managed by hospitalists, and 35% by cardiologists. A recent national survey of advanced heart failure programs found that cardiologists managed the care of acute HF patients more than 60 percent of the time.2

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

Data reported at the American Heart Association’s scientific sessions in Los Angeles in November suggest that when a cardiologist, rather than a hospitalist, is the attending physician for a hospitalized heart failure patient, readmission is less likely. Casey M. Lawler, MD, FACC, a cardiologist at the Minneapolis Heart Institute, says her center began establishing protocols to improve heart failure readmissions rates five years ago, after determining that many patients did not understand their diagnosis or treatment. “Thus, we became much more involved in post-discharge care,” including the phoning of discharged patients and follow-up with primary-care providers.

When the heart failure patients’ attending physicians were cardiologists, their readmission rate was 16%, versus 27.1% with hospitalists, even though their severity of illness was higher. Length of stay was similar for both groups and total mean costs were higher for the patients managed by cardiologists. “Although these results reveal that specialists have a positive impact on readmission rates, an overhaul to an entire healthcare system’s treatment of [heart failure] patients—from admission to post-discharge follow-up—is required to truly impact preventable readmissions,” Dr. Lawler asserted.

In the Minneapolis study, 65% of the 2,300 heart failure patients were managed by hospitalists, and 35% by cardiologists. A recent national survey of advanced heart failure programs found that cardiologists managed the care of acute HF patients more than 60 percent of the time.2

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

Data reported at the American Heart Association’s scientific sessions in Los Angeles in November suggest that when a cardiologist, rather than a hospitalist, is the attending physician for a hospitalized heart failure patient, readmission is less likely. Casey M. Lawler, MD, FACC, a cardiologist at the Minneapolis Heart Institute, says her center began establishing protocols to improve heart failure readmissions rates five years ago, after determining that many patients did not understand their diagnosis or treatment. “Thus, we became much more involved in post-discharge care,” including the phoning of discharged patients and follow-up with primary-care providers.

When the heart failure patients’ attending physicians were cardiologists, their readmission rate was 16%, versus 27.1% with hospitalists, even though their severity of illness was higher. Length of stay was similar for both groups and total mean costs were higher for the patients managed by cardiologists. “Although these results reveal that specialists have a positive impact on readmission rates, an overhaul to an entire healthcare system’s treatment of [heart failure] patients—from admission to post-discharge follow-up—is required to truly impact preventable readmissions,” Dr. Lawler asserted.

In the Minneapolis study, 65% of the 2,300 heart failure patients were managed by hospitalists, and 35% by cardiologists. A recent national survey of advanced heart failure programs found that cardiologists managed the care of acute HF patients more than 60 percent of the time.2

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

VTE Pathway Improves Outcomes for Uninsured Patients

A poster presented at HM12 in San Diego last April describes a standardized, systematic, multidisciplinary clinical pathway for treating acute VTE (venous thromboembolism) in an urban hospital serving a high proportion of the uninsured.3 Implementing the pathway in February 2011 “dramatically reduced hospital utilization and cost, particularly among uninsured patients,” who were previously shown to have increased length of stay, cost, and emergency department recidivism, says lead author Gregory Misky, MD, a hospitalist at the University of Colorado Denver.

The pathway—which aimed to standardize all VTE care from hospital presentation to post-discharge follow-up—contained multiple components, including education for staff, enhanced communication processes, written order sets, and a series of formal and informal meetings held with community providers, such as the clinics where these patients get their follow-up primary care. Dr. Misky collaborated with his university’s anticoagulation clinic to help identify primary-care physicians and clinics and arrange follow-up outpatient appointments much sooner than the patients could have obtained by themselves.

The prospective study compared 135 VTE patients presenting to the emergency department or admitted to a medicine service and receiving care under the pathway, compared with 234 VTE patients prior to its introduction. Length of stay dropped to 2.5 days from 4.2, and for uninsured patients it dropped even more, to 2.2 days from 5.5.

Dr. Misky says the data gathered since the San Diego conference “continue to show good results in resource utilization, particularly for the uninsured, with emergency department visits and readmissions slashed.” Readmissions have dropped to 5.2% from 9.8%—and to 3.5% from 11.6% for uninsured VTE patients. He suggests that the clinical pathway approach likely has implications for other diseases as well.

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

A poster presented at HM12 in San Diego last April describes a standardized, systematic, multidisciplinary clinical pathway for treating acute VTE (venous thromboembolism) in an urban hospital serving a high proportion of the uninsured.3 Implementing the pathway in February 2011 “dramatically reduced hospital utilization and cost, particularly among uninsured patients,” who were previously shown to have increased length of stay, cost, and emergency department recidivism, says lead author Gregory Misky, MD, a hospitalist at the University of Colorado Denver.

The pathway—which aimed to standardize all VTE care from hospital presentation to post-discharge follow-up—contained multiple components, including education for staff, enhanced communication processes, written order sets, and a series of formal and informal meetings held with community providers, such as the clinics where these patients get their follow-up primary care. Dr. Misky collaborated with his university’s anticoagulation clinic to help identify primary-care physicians and clinics and arrange follow-up outpatient appointments much sooner than the patients could have obtained by themselves.

The prospective study compared 135 VTE patients presenting to the emergency department or admitted to a medicine service and receiving care under the pathway, compared with 234 VTE patients prior to its introduction. Length of stay dropped to 2.5 days from 4.2, and for uninsured patients it dropped even more, to 2.2 days from 5.5.

Dr. Misky says the data gathered since the San Diego conference “continue to show good results in resource utilization, particularly for the uninsured, with emergency department visits and readmissions slashed.” Readmissions have dropped to 5.2% from 9.8%—and to 3.5% from 11.6% for uninsured VTE patients. He suggests that the clinical pathway approach likely has implications for other diseases as well.

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

A poster presented at HM12 in San Diego last April describes a standardized, systematic, multidisciplinary clinical pathway for treating acute VTE (venous thromboembolism) in an urban hospital serving a high proportion of the uninsured.3 Implementing the pathway in February 2011 “dramatically reduced hospital utilization and cost, particularly among uninsured patients,” who were previously shown to have increased length of stay, cost, and emergency department recidivism, says lead author Gregory Misky, MD, a hospitalist at the University of Colorado Denver.

The pathway—which aimed to standardize all VTE care from hospital presentation to post-discharge follow-up—contained multiple components, including education for staff, enhanced communication processes, written order sets, and a series of formal and informal meetings held with community providers, such as the clinics where these patients get their follow-up primary care. Dr. Misky collaborated with his university’s anticoagulation clinic to help identify primary-care physicians and clinics and arrange follow-up outpatient appointments much sooner than the patients could have obtained by themselves.

The prospective study compared 135 VTE patients presenting to the emergency department or admitted to a medicine service and receiving care under the pathway, compared with 234 VTE patients prior to its introduction. Length of stay dropped to 2.5 days from 4.2, and for uninsured patients it dropped even more, to 2.2 days from 5.5.

Dr. Misky says the data gathered since the San Diego conference “continue to show good results in resource utilization, particularly for the uninsured, with emergency department visits and readmissions slashed.” Readmissions have dropped to 5.2% from 9.8%—and to 3.5% from 11.6% for uninsured VTE patients. He suggests that the clinical pathway approach likely has implications for other diseases as well.

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

Well-Designed IT Systems Essential to Healthcare Integration

David Lawrence, MD, retired head of the Kaiser Foundation health plan, says in a recent Information Week article that it will be “nearly impossible” to achieve the goals of healthcare integration without the connectivity of a well-designed health IT system.4 Dr. Lawrence was a member of a committee that authored the recent report Order from Chaos: Accelerating Care Integration for the Lucian Leape Institute at the National Patient Care Safety Foundation. Failures of coordination most often happen during the crucial information transfers that happen during care transitions, but there has not been enough attention to how important information technology could be to these transfers, Dr. Lawrence told the magazine. “It’s the really complex stuff where this becomes particularly critical,” he said.

The federal Office of Inspector General (OIG) took the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to task in a November report for not having adequate oversight or safeguards for its EHR meaningful-use program.5 As a result, OIG described Medicare as “vulnerable” to fraud and abuse of incentive payments made to hospitals and health professionals, according to OIG. OIG recommends that CMS request and review supporting documentation for selected providers and issue guidance with specific examples of appropriate documentation. As of September 2012, CMS had paid out $4 billion in meaningful-use incentives to 1,400 hospitals and 82,000 professionals.

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

David Lawrence, MD, retired head of the Kaiser Foundation health plan, says in a recent Information Week article that it will be “nearly impossible” to achieve the goals of healthcare integration without the connectivity of a well-designed health IT system.4 Dr. Lawrence was a member of a committee that authored the recent report Order from Chaos: Accelerating Care Integration for the Lucian Leape Institute at the National Patient Care Safety Foundation. Failures of coordination most often happen during the crucial information transfers that happen during care transitions, but there has not been enough attention to how important information technology could be to these transfers, Dr. Lawrence told the magazine. “It’s the really complex stuff where this becomes particularly critical,” he said.

The federal Office of Inspector General (OIG) took the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to task in a November report for not having adequate oversight or safeguards for its EHR meaningful-use program.5 As a result, OIG described Medicare as “vulnerable” to fraud and abuse of incentive payments made to hospitals and health professionals, according to OIG. OIG recommends that CMS request and review supporting documentation for selected providers and issue guidance with specific examples of appropriate documentation. As of September 2012, CMS had paid out $4 billion in meaningful-use incentives to 1,400 hospitals and 82,000 professionals.

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

David Lawrence, MD, retired head of the Kaiser Foundation health plan, says in a recent Information Week article that it will be “nearly impossible” to achieve the goals of healthcare integration without the connectivity of a well-designed health IT system.4 Dr. Lawrence was a member of a committee that authored the recent report Order from Chaos: Accelerating Care Integration for the Lucian Leape Institute at the National Patient Care Safety Foundation. Failures of coordination most often happen during the crucial information transfers that happen during care transitions, but there has not been enough attention to how important information technology could be to these transfers, Dr. Lawrence told the magazine. “It’s the really complex stuff where this becomes particularly critical,” he said.

The federal Office of Inspector General (OIG) took the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to task in a November report for not having adequate oversight or safeguards for its EHR meaningful-use program.5 As a result, OIG described Medicare as “vulnerable” to fraud and abuse of incentive payments made to hospitals and health professionals, according to OIG. OIG recommends that CMS request and review supporting documentation for selected providers and issue guidance with specific examples of appropriate documentation. As of September 2012, CMS had paid out $4 billion in meaningful-use incentives to 1,400 hospitals and 82,000 professionals.

References

- Enguidanos S, Vesper E, Lorenz K. 30-day readmissions among seriously ill older adults. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1356-1361.

- The Advisory Board Company. Mastering the cardiovascular care continuum: strategies for bridging divides among providers and across time. The Advisory Board Company website. Available at: http://www.advisory.com/Research/Cardiovascular-Roundtable/Studies/2012/Mastering-the-Cardiovascular-Care-Continuum. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Misky G, Carlson T, Klem P, et al. Development and implementation of a clinical care pathway for acute VTE reduces hospital utilization and cost at an urban tertiary care center [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2012;7 Suppl 2:S66-S67.

- Versel N. Health IT holds key to better care integration. Information Week website. Available at: http://www.informationweek.com/healthcare/interoperability/health-it-holds-key-to-better-care-integ/240012443. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

- Office of Inspector General. Early Assessment Finds That CMS Faces Obstacles in Overseeing the Medicare EHR Incentive Program. Office of Inspector General website. Available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-11-00250.asp. Accessed Jan. 8, 2013.

Pharmacist-Hospitalist Collaboration Can Improve Care, Save Money

A healthy collaboration between hospitalists and pharmacists can generate cost savings and promote positive outcomes, such as preventing adverse drug events and improving care transitions, says Jonathan Edwards, PharmD, BCPS, a clinical pharmacy specialist at Huntsville Hospital in Alabama.

At the 2012 national conference of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy in Hollywood, Fla., Edwards presented a poster that detailed the effectiveness of such interdisciplinary collaboration at Huntsville Hospital, where pharmacists and physicians developed six order sets, a collaborative practice, and a patient interaction program from November 2011 to February 2012. During the study period, researchers documented a total cost savings of $9,825 resulting from 156 patient interventions.

Edwards’ collaborative study at Huntsville started with two physicians who had launched a service teaching hospitalists what pharmacists do, and how they could help in their efforts.

“We got together and developed an order set for treating acute alcohol withdrawal. That went well, so we did five more order sets,” Edwards says. “Then we thought: What if pharmacists got more involved by meeting directly with patients in the hospital to optimize their medication management and help them reach their goals for treatment? We now evaluate patients on the hospitalist service in three units.”

For Edwards, key factors that make the hospitalist-pharmacist relationship work include communicating the pharmacist’s availability to help with the hospitalist’s patients, identifying the physician’s openness to help, and clarifying how the physician prefers to be contacted.

Last October, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) and the American Pharmacists Association (APhA) recognized eight care-transitions programs for best practices that improved patient outcomes and reduced hospital readmissions as part of the Medication Management in Care Transitions (MMCT) Project.

“The MMCT project highlights the valuable role pharmacists can play in addressing medication-related problems that can lead to hospital readmissions,” APhA chief executive officer Thomas E. Menighan, BSPharm, MBA, ScD (Hon), FAPhA, said in a news release. “By putting together these best practices, our goal is to provide a model for better coordination of care and better connectivity between pharmacists and healthcare providers in different practice settings that leads to improved patient health.”

Visit our website for more information about maximizing patient care through pharmacist-hospitalist collaboration.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

Articles first published in the Jan. 16, 2013, edition of The Hospitalist eWire.

A healthy collaboration between hospitalists and pharmacists can generate cost savings and promote positive outcomes, such as preventing adverse drug events and improving care transitions, says Jonathan Edwards, PharmD, BCPS, a clinical pharmacy specialist at Huntsville Hospital in Alabama.

At the 2012 national conference of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy in Hollywood, Fla., Edwards presented a poster that detailed the effectiveness of such interdisciplinary collaboration at Huntsville Hospital, where pharmacists and physicians developed six order sets, a collaborative practice, and a patient interaction program from November 2011 to February 2012. During the study period, researchers documented a total cost savings of $9,825 resulting from 156 patient interventions.

Edwards’ collaborative study at Huntsville started with two physicians who had launched a service teaching hospitalists what pharmacists do, and how they could help in their efforts.

“We got together and developed an order set for treating acute alcohol withdrawal. That went well, so we did five more order sets,” Edwards says. “Then we thought: What if pharmacists got more involved by meeting directly with patients in the hospital to optimize their medication management and help them reach their goals for treatment? We now evaluate patients on the hospitalist service in three units.”

For Edwards, key factors that make the hospitalist-pharmacist relationship work include communicating the pharmacist’s availability to help with the hospitalist’s patients, identifying the physician’s openness to help, and clarifying how the physician prefers to be contacted.

Last October, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) and the American Pharmacists Association (APhA) recognized eight care-transitions programs for best practices that improved patient outcomes and reduced hospital readmissions as part of the Medication Management in Care Transitions (MMCT) Project.

“The MMCT project highlights the valuable role pharmacists can play in addressing medication-related problems that can lead to hospital readmissions,” APhA chief executive officer Thomas E. Menighan, BSPharm, MBA, ScD (Hon), FAPhA, said in a news release. “By putting together these best practices, our goal is to provide a model for better coordination of care and better connectivity between pharmacists and healthcare providers in different practice settings that leads to improved patient health.”

Visit our website for more information about maximizing patient care through pharmacist-hospitalist collaboration.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

Articles first published in the Jan. 16, 2013, edition of The Hospitalist eWire.

A healthy collaboration between hospitalists and pharmacists can generate cost savings and promote positive outcomes, such as preventing adverse drug events and improving care transitions, says Jonathan Edwards, PharmD, BCPS, a clinical pharmacy specialist at Huntsville Hospital in Alabama.

At the 2012 national conference of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy in Hollywood, Fla., Edwards presented a poster that detailed the effectiveness of such interdisciplinary collaboration at Huntsville Hospital, where pharmacists and physicians developed six order sets, a collaborative practice, and a patient interaction program from November 2011 to February 2012. During the study period, researchers documented a total cost savings of $9,825 resulting from 156 patient interventions.

Edwards’ collaborative study at Huntsville started with two physicians who had launched a service teaching hospitalists what pharmacists do, and how they could help in their efforts.

“We got together and developed an order set for treating acute alcohol withdrawal. That went well, so we did five more order sets,” Edwards says. “Then we thought: What if pharmacists got more involved by meeting directly with patients in the hospital to optimize their medication management and help them reach their goals for treatment? We now evaluate patients on the hospitalist service in three units.”

For Edwards, key factors that make the hospitalist-pharmacist relationship work include communicating the pharmacist’s availability to help with the hospitalist’s patients, identifying the physician’s openness to help, and clarifying how the physician prefers to be contacted.

Last October, the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) and the American Pharmacists Association (APhA) recognized eight care-transitions programs for best practices that improved patient outcomes and reduced hospital readmissions as part of the Medication Management in Care Transitions (MMCT) Project.

“The MMCT project highlights the valuable role pharmacists can play in addressing medication-related problems that can lead to hospital readmissions,” APhA chief executive officer Thomas E. Menighan, BSPharm, MBA, ScD (Hon), FAPhA, said in a news release. “By putting together these best practices, our goal is to provide a model for better coordination of care and better connectivity between pharmacists and healthcare providers in different practice settings that leads to improved patient health.”

Visit our website for more information about maximizing patient care through pharmacist-hospitalist collaboration.

Larry Beresford is a freelance writer in Oakland, Calif.

Articles first published in the Jan. 16, 2013, edition of The Hospitalist eWire.

New Codes Bridge Hospitals' Post-Discharge Billing Gap

In November 2012, the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) finalized its 2013 physician fee schedule with two new transitional-care-management (TCM) codes, 99495 and 99496. These codes provide reimbursement for transitional-care services to patients for 30 days after hospital discharge. CMS estimates that two-thirds of the 10 million Medicare patients discharged annually from hospitals will have TCM services provided by an outpatient doctor. Why might hospitalists be interested in these outpatient codes? Read on.

As a post-discharge provider in a primary-care-based discharge clinic, I can say the new Medicare transitional codes read like our job description. Because I’ve worked in a post-discharge clinic for the past three years, I have learned that post-discharge care requires time and resource allocation beyond routine outpatient care. Because of the unique population we see, on average we bill at a higher level than the rest of the practice. Yet we, like all outpatient providers, remain constrained by the existing billing structure, which is intimately connected to physician face-to-face visits.

Here’s an illustration of a typical afternoon in the post-discharge clinic: A schizophrenic patient presents with renal failure, hypoglycemia, and confusion. Her home visiting nurse (VNA) administers her medications; the patient cannot tell you any of them. While you are calling the VNA to clarify her medications, trying to identify her healthcare proxy, and stopping her ACE inhibitor because her potassium is 5.6, the next patient arrives. She has end-stage liver disease and was recently in the hospital for liver failure, and now has worsening recurrent ascites. After clinic, you call interventional radiology to coordinate a therapeutic paracentesis and change diuretic doses after her labs return. Two weeks later, you arrange a repeat paracentesis, and subsequently a transition to comfort care in a hospice house. For this work, right now, you can at most bill a high-complexity office visit (99215), and the rest of the care coordination—by you, your nurse, or your administrative staff—is not compensated.

How Do the New Codes Work?

CMS created the new TCM codes to begin to change the outpatient fee schedule to emphasize primary care and care coordination for beneficiaries, particularly in the post-hospitalization period. The new TCM codes are a first step toward reimbursement for non-face-to-face activities, which are increasingly important in the evolving healthcare system.

The investment is estimated at more than $1 billion in 2013. The new codes are available to physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and other advanced-practice nurses only once within the 30 days after hospital discharge. During the 30 days after discharge, the two codes, 99495 and 99496, require a single face-to-face visit within seven days of discharge for the highest-risk patients and within 14 days of discharge for moderate-risk patients. The face-to-face visit is not billed separately. The codes also mandate telephone communication with the patient or caregiver within two business days of hospital discharge; the medical decision-making must be of either moderate or high complexity.

The average reimbursement for the codes will be $132.96 for 99495 and $231.11 for 99496, reflecting a higher wRVU than either hospital discharge day management or high-acuity outpatient visits. The code is billed at the end of the 30 days. The TCM code cannot be billed a second time if a patient is readmitted within the 30 days. Other E/M codes can be billed during the same time period for additional visits as necessary.

What’s the Impact on Hospitalists?

The new codes affect hospitalists in two ways. First, the hospitalists in the growing group of “transitionalists,” many of whom practice in outpatient clinics seeing patients after discharge, will be able to use these codes. As the codes require no pre-existing relationship with the patient, non-primary-care providers will be able to bill these codes, assuming that they fulfill the designated requirements. This concession enables hospitalists to fill a vital role for those patients who have inadequate access to immediate primary care post-hospitalization. It also provides a necessary bridge to appropriate primary care for those patients. This group of patients might be particularly vulnerable to adverse events, including hospital readmission, given their suboptimal connection with their primary-care providers.

Hospitalists who practice entirely as inpatient physicians will not be able to bill these new codes, but they will provide a valuable service to patients by helping identify the physicians who will provide their TCM and documenting this in the discharge documentation, already seen as a key element of discharge day management services.

Do These Codes Change the Business Case for Discharge Clinics?

Discharge clinics, either hospitalist-staffed or otherwise, have been actively discussed in the media in recent years.1 Even without these transitional codes, discharge clinics have arisen where primary-care access is limited and as a potential, but as yet unproven, solution to high readmission rates. Despite this proliferation, discharge clinics have not yet proven to be cost-effective.

Implementation of these codes could change the calculus for organizations considering dedicating resources to a discharge clinic. The new codes could make discharge clinics more financially viable by increasing the reimbursement for care that often requires more than 30 minutes. However, based on the experience in our clinic, the increased revenue accurately reflects the intensity of service necessary to coordinate care in the post-discharge period.

The time intensity of care already is obvious from the structure of established discharge clinics. Examples include the comprehensive care centers at HealthCare Partners in Southern California, where multidisciplinary visits average 90 minutes, or at our clinic at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.2 While the visits in our clinic are less than half as long as those at HealthCare Partners, we are not including the time spent reviewing the discharge documentation, outstanding tests, and medication changes in advance of the visit, and the time spent after the visit, coordinating the patient’s care with visiting nurses and elder service agencies.3

What’s Next?

Whether these codes lead to an increased interest in hospitalist-staffed discharge clinics or to primary-care development of robust transitional-care structures, these new codes will help focus resources and attention on increasing services, with the goal of improving patient care during a period of extreme vulnerability. This alone is something to be grateful for, whether you are a transitionalist, hospitalist, primary-care doctor, caregiver, or patient.

Dr. Doctoroff is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston and an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School. She is medical director of BIDMC’s Health Care Associates Post Discharge Clinic.

References

- Andrews M. Post-discharge clinics try to cut hospital readmissions by helping patients. Washington Post website. Available at: http://articles.washingtonpost.com/2011-12-19/national/35288219_1_readmissions-discharge-vulnerable-patients. Accessed Jan. 7, 2013.

- Feder JL. Predictive modeling and team care for high-need patients at HealthCare Partners. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(3):416-418.

- Doctoroff L. Interval examination: establishment of a hospitalist-staffed discharge clinic. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1377-1382.

In November 2012, the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) finalized its 2013 physician fee schedule with two new transitional-care-management (TCM) codes, 99495 and 99496. These codes provide reimbursement for transitional-care services to patients for 30 days after hospital discharge. CMS estimates that two-thirds of the 10 million Medicare patients discharged annually from hospitals will have TCM services provided by an outpatient doctor. Why might hospitalists be interested in these outpatient codes? Read on.

As a post-discharge provider in a primary-care-based discharge clinic, I can say the new Medicare transitional codes read like our job description. Because I’ve worked in a post-discharge clinic for the past three years, I have learned that post-discharge care requires time and resource allocation beyond routine outpatient care. Because of the unique population we see, on average we bill at a higher level than the rest of the practice. Yet we, like all outpatient providers, remain constrained by the existing billing structure, which is intimately connected to physician face-to-face visits.

Here’s an illustration of a typical afternoon in the post-discharge clinic: A schizophrenic patient presents with renal failure, hypoglycemia, and confusion. Her home visiting nurse (VNA) administers her medications; the patient cannot tell you any of them. While you are calling the VNA to clarify her medications, trying to identify her healthcare proxy, and stopping her ACE inhibitor because her potassium is 5.6, the next patient arrives. She has end-stage liver disease and was recently in the hospital for liver failure, and now has worsening recurrent ascites. After clinic, you call interventional radiology to coordinate a therapeutic paracentesis and change diuretic doses after her labs return. Two weeks later, you arrange a repeat paracentesis, and subsequently a transition to comfort care in a hospice house. For this work, right now, you can at most bill a high-complexity office visit (99215), and the rest of the care coordination—by you, your nurse, or your administrative staff—is not compensated.

How Do the New Codes Work?

CMS created the new TCM codes to begin to change the outpatient fee schedule to emphasize primary care and care coordination for beneficiaries, particularly in the post-hospitalization period. The new TCM codes are a first step toward reimbursement for non-face-to-face activities, which are increasingly important in the evolving healthcare system.

The investment is estimated at more than $1 billion in 2013. The new codes are available to physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and other advanced-practice nurses only once within the 30 days after hospital discharge. During the 30 days after discharge, the two codes, 99495 and 99496, require a single face-to-face visit within seven days of discharge for the highest-risk patients and within 14 days of discharge for moderate-risk patients. The face-to-face visit is not billed separately. The codes also mandate telephone communication with the patient or caregiver within two business days of hospital discharge; the medical decision-making must be of either moderate or high complexity.

The average reimbursement for the codes will be $132.96 for 99495 and $231.11 for 99496, reflecting a higher wRVU than either hospital discharge day management or high-acuity outpatient visits. The code is billed at the end of the 30 days. The TCM code cannot be billed a second time if a patient is readmitted within the 30 days. Other E/M codes can be billed during the same time period for additional visits as necessary.

What’s the Impact on Hospitalists?

The new codes affect hospitalists in two ways. First, the hospitalists in the growing group of “transitionalists,” many of whom practice in outpatient clinics seeing patients after discharge, will be able to use these codes. As the codes require no pre-existing relationship with the patient, non-primary-care providers will be able to bill these codes, assuming that they fulfill the designated requirements. This concession enables hospitalists to fill a vital role for those patients who have inadequate access to immediate primary care post-hospitalization. It also provides a necessary bridge to appropriate primary care for those patients. This group of patients might be particularly vulnerable to adverse events, including hospital readmission, given their suboptimal connection with their primary-care providers.

Hospitalists who practice entirely as inpatient physicians will not be able to bill these new codes, but they will provide a valuable service to patients by helping identify the physicians who will provide their TCM and documenting this in the discharge documentation, already seen as a key element of discharge day management services.

Do These Codes Change the Business Case for Discharge Clinics?