User login

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Listen to Joaquin Cigarroa, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University, discuss the overlap of cardiology and hospital medicine

Click here to listen to Dr. Cigarroa

Click here to listen to Dr. Cigarroa

Click here to listen to Dr. Cigarroa

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Daniel Dressler, MD, MSc, SFHM, discusses the differences in opinion over the SHM/SCCM critical care fellowship proposal

Click here to listen to Dr. Dressler

Click here to listen to Dr. Dressler

Click here to listen to Dr. Dressler

Penalties for Hospitals with Excessive Readmissions Take Effect

The new era of penalizing hospitals for higher-than-predicted 30-day avoidable readmissions rates has begun. Under the federal Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, some calculate a hospital's excessive readmissions rate for each applicable condition.

Penalties for the current fiscal year—FY 2013, which began Oct. 1, 2012—will be based on discharges that occurred during the three-year period from July 1, 2008, to June 30, 2011, according to the program guidelines. For hospitals that don't improve, the penalty grows to a maximum 2% next year (FY14) and 3% in FY15.

Hospitalists are not penalized directly for readmissions, and many hospitalists are wondering about the extent to which they're responsible for a readmission after the patient leaves the hospital, notes Mark Williams, MD, FACP, MHM, chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

Dr. Williams is the principal investigator of SHM’s Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions), one of several national quality initiatives that teach hospitals and other healthcare providers how to improve transitions of care through such techniques as patient coaching and community partnerships.

"These new penalties mean that hospitals will start talking to their physicians about readmissions, and looking for methods to incentivize the hospitalists to get involved in preventing them," Dr. Williams says.

The new era of penalizing hospitals for higher-than-predicted 30-day avoidable readmissions rates has begun. Under the federal Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, some calculate a hospital's excessive readmissions rate for each applicable condition.

Penalties for the current fiscal year—FY 2013, which began Oct. 1, 2012—will be based on discharges that occurred during the three-year period from July 1, 2008, to June 30, 2011, according to the program guidelines. For hospitals that don't improve, the penalty grows to a maximum 2% next year (FY14) and 3% in FY15.

Hospitalists are not penalized directly for readmissions, and many hospitalists are wondering about the extent to which they're responsible for a readmission after the patient leaves the hospital, notes Mark Williams, MD, FACP, MHM, chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

Dr. Williams is the principal investigator of SHM’s Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions), one of several national quality initiatives that teach hospitals and other healthcare providers how to improve transitions of care through such techniques as patient coaching and community partnerships.

"These new penalties mean that hospitals will start talking to their physicians about readmissions, and looking for methods to incentivize the hospitalists to get involved in preventing them," Dr. Williams says.

The new era of penalizing hospitals for higher-than-predicted 30-day avoidable readmissions rates has begun. Under the federal Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, some calculate a hospital's excessive readmissions rate for each applicable condition.

Penalties for the current fiscal year—FY 2013, which began Oct. 1, 2012—will be based on discharges that occurred during the three-year period from July 1, 2008, to June 30, 2011, according to the program guidelines. For hospitals that don't improve, the penalty grows to a maximum 2% next year (FY14) and 3% in FY15.

Hospitalists are not penalized directly for readmissions, and many hospitalists are wondering about the extent to which they're responsible for a readmission after the patient leaves the hospital, notes Mark Williams, MD, FACP, MHM, chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

Dr. Williams is the principal investigator of SHM’s Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions), one of several national quality initiatives that teach hospitals and other healthcare providers how to improve transitions of care through such techniques as patient coaching and community partnerships.

"These new penalties mean that hospitals will start talking to their physicians about readmissions, and looking for methods to incentivize the hospitalists to get involved in preventing them," Dr. Williams says.

Study: Neurohospitalists Benefit Academic Medical Centers

Bringing a neurohospitalist service into an academic medical center can reduce neurological patients' length of stay (LOS) at the facility, according to a study in Neurology.

The retrospective cohort study, "Effect of a Neurohospitalist Service on Outcomes at an Academic Medical Center," found that the mean LOS dropped to 4.6 days while the neurohospitalist service was in place, compared with 6.3 days during the pre-neurohospitalist period. However, adding the service didn't significantly reduce the median cost of care delivery ($6,758 vs. $7,241; P=0.25) or in-hospital mortality rate (1.6% vs. 1.2%; P=0.61), the study noted.

Lead author Vanja Douglas, MD, health sciences assistant clinical professor in the department of neurology at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) School of Medicine, says the study's impact is limited by its single-center universe of data. The study was conducted at a UCSF Medical Center in October 2006, but Dr. Douglas hopes similar studies at other academic or community centers will replicate the findings.

"If the current model people have in place is not necessarily focused on outcomes like LOS and cost, then making a change to a neurohospitalist model is likely to positively affect those outcomes," says Dr. Douglas, editor in chief of The Neurohospitalist.

Investigators tracked administrative data starting 21 months before UCSF added a neurohospitalist service and 27 months after. The service was comprised of one neurohospitalist focused solely on inpatients, which allowed other staff neurologists to focus on consultative cases throughout the hospital. Dr. Douglas says as HM groups look to improve their scope of practice and bottom line, studies such as his can lay the groundwork to make the investment.

"A lot of the groups that contract with hospitals are interested in partnering with subspecialty hospitalists," Dr. Douglas adds. "A neurohospitalist model has the potential to work, and the potential to improve outcomes."

Bringing a neurohospitalist service into an academic medical center can reduce neurological patients' length of stay (LOS) at the facility, according to a study in Neurology.

The retrospective cohort study, "Effect of a Neurohospitalist Service on Outcomes at an Academic Medical Center," found that the mean LOS dropped to 4.6 days while the neurohospitalist service was in place, compared with 6.3 days during the pre-neurohospitalist period. However, adding the service didn't significantly reduce the median cost of care delivery ($6,758 vs. $7,241; P=0.25) or in-hospital mortality rate (1.6% vs. 1.2%; P=0.61), the study noted.

Lead author Vanja Douglas, MD, health sciences assistant clinical professor in the department of neurology at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) School of Medicine, says the study's impact is limited by its single-center universe of data. The study was conducted at a UCSF Medical Center in October 2006, but Dr. Douglas hopes similar studies at other academic or community centers will replicate the findings.

"If the current model people have in place is not necessarily focused on outcomes like LOS and cost, then making a change to a neurohospitalist model is likely to positively affect those outcomes," says Dr. Douglas, editor in chief of The Neurohospitalist.

Investigators tracked administrative data starting 21 months before UCSF added a neurohospitalist service and 27 months after. The service was comprised of one neurohospitalist focused solely on inpatients, which allowed other staff neurologists to focus on consultative cases throughout the hospital. Dr. Douglas says as HM groups look to improve their scope of practice and bottom line, studies such as his can lay the groundwork to make the investment.

"A lot of the groups that contract with hospitals are interested in partnering with subspecialty hospitalists," Dr. Douglas adds. "A neurohospitalist model has the potential to work, and the potential to improve outcomes."

Bringing a neurohospitalist service into an academic medical center can reduce neurological patients' length of stay (LOS) at the facility, according to a study in Neurology.

The retrospective cohort study, "Effect of a Neurohospitalist Service on Outcomes at an Academic Medical Center," found that the mean LOS dropped to 4.6 days while the neurohospitalist service was in place, compared with 6.3 days during the pre-neurohospitalist period. However, adding the service didn't significantly reduce the median cost of care delivery ($6,758 vs. $7,241; P=0.25) or in-hospital mortality rate (1.6% vs. 1.2%; P=0.61), the study noted.

Lead author Vanja Douglas, MD, health sciences assistant clinical professor in the department of neurology at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) School of Medicine, says the study's impact is limited by its single-center universe of data. The study was conducted at a UCSF Medical Center in October 2006, but Dr. Douglas hopes similar studies at other academic or community centers will replicate the findings.

"If the current model people have in place is not necessarily focused on outcomes like LOS and cost, then making a change to a neurohospitalist model is likely to positively affect those outcomes," says Dr. Douglas, editor in chief of The Neurohospitalist.

Investigators tracked administrative data starting 21 months before UCSF added a neurohospitalist service and 27 months after. The service was comprised of one neurohospitalist focused solely on inpatients, which allowed other staff neurologists to focus on consultative cases throughout the hospital. Dr. Douglas says as HM groups look to improve their scope of practice and bottom line, studies such as his can lay the groundwork to make the investment.

"A lot of the groups that contract with hospitals are interested in partnering with subspecialty hospitalists," Dr. Douglas adds. "A neurohospitalist model has the potential to work, and the potential to improve outcomes."

Rules of Engagement Necessary for Comanagement of Orthopedic Patients

One of our providers wants to use adult hospitalists for coverage of inpatient orthopedic surgery patients. Is this acceptable practice? Are there qualifiers?

–Libby Gardner

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Let’s see how far we can tackle this open-ended question. There has been lots of discussion on the topic of comanagement in the past by people eminently more qualified than I am. Still, it never hurts to take a fresh look at things.

For one, on the subject of admissions, I am a firm believer that hospitalists should admit all adult hip fractures. The overwhelming majority of the time, these patients are elderly with comorbid conditions. Sure, they are going to get their hip fixed, because the alternative is usually unacceptable, but some thought needs to go into the process. The orthopedic surgeon sees a hip that needs fixing and not much else. When issues like renal failure, afib, CHF, prior DVT, or dementia are present, hospitalists should take charge of the case. It is the best way to ensure that the patient receives optimal medical care and the documentation that goes along with it. I love our orthopedic surgeons, but I don’t want them primarily admitting, managing, and discharging my elderly patients. Let the surgeon do what they do best, which is operate, and leave the rest to us.

On the subject of orthopedic trauma, I take the exact opposite tack—this is not something for which I or most of my colleagues have expertise. A young, healthy patient with trauma should be admitted by the orthopedic service; that patient population’s complications are much more likely to be directly related to their trauma.

When it comes to elective surgery, when the admitting surgeon (orthopedic or otherwise) wants the help of a hospitalist, then I think it is of paramount importance to have clear “rules of engagement.” I think with good expectations, you can have a fantastic working relationship with your surgeons. Without them, it becomes a nightmare.

Here are my HM group’s rules for elective orthopedic surgery:

- Orthopedics handles all pain medications and VTE prophylaxis, including discharge prescriptions.

- Medicine handles all admit and discharge medication reconciliation (“med rec”).

- There is shared discussion on:

- Need for transfusion; and

- The VTE prophylaxis when a patient already is on chronic anticoagulation.

We do not vary from this protocol. I never adjust a patient’s pain medications. Even the floor nurses know this. Because I’m doing the admit med rec, it also means that the patient doesn’t have their HCTZ continued after 600cc of EBL and spinal anesthesia.

The system works because the rules are clear and the communication is consistent. This does not mean that we cover the orthopedic service at night. They are equally responsible for their patients under the items outlined above. In my view—and this might sound simplistic—the surgeon caused the post-op pain, so they should be responsible for managing it. On VTE prophylaxis, I might take a more nuanced view, but for our surgeons, they own the wound and the post-op follow-up, so they get the choice on what agent to use.

Would I accept an arrangement in which I covered all the orthopedic issues out of regular hours? Nope—not when they have primary responsibility for the case; they should always be directly available to the nurse. I think that anything else would be a system ripe for abuse.

Our exact rules will not work for every situation, but I would strongly encourage the two basic tenets from above: No. 1, the hospitalist should primarily admit and manage elderly hip fractures, and No. 2, clear rules of engagement should be established with your orthopedic or surgery group. It’s a discussion worth having during daylight hours, because trying to figure out the rules at 3 in the morning rarely ends well.

One of our providers wants to use adult hospitalists for coverage of inpatient orthopedic surgery patients. Is this acceptable practice? Are there qualifiers?

–Libby Gardner

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Let’s see how far we can tackle this open-ended question. There has been lots of discussion on the topic of comanagement in the past by people eminently more qualified than I am. Still, it never hurts to take a fresh look at things.

For one, on the subject of admissions, I am a firm believer that hospitalists should admit all adult hip fractures. The overwhelming majority of the time, these patients are elderly with comorbid conditions. Sure, they are going to get their hip fixed, because the alternative is usually unacceptable, but some thought needs to go into the process. The orthopedic surgeon sees a hip that needs fixing and not much else. When issues like renal failure, afib, CHF, prior DVT, or dementia are present, hospitalists should take charge of the case. It is the best way to ensure that the patient receives optimal medical care and the documentation that goes along with it. I love our orthopedic surgeons, but I don’t want them primarily admitting, managing, and discharging my elderly patients. Let the surgeon do what they do best, which is operate, and leave the rest to us.

On the subject of orthopedic trauma, I take the exact opposite tack—this is not something for which I or most of my colleagues have expertise. A young, healthy patient with trauma should be admitted by the orthopedic service; that patient population’s complications are much more likely to be directly related to their trauma.

When it comes to elective surgery, when the admitting surgeon (orthopedic or otherwise) wants the help of a hospitalist, then I think it is of paramount importance to have clear “rules of engagement.” I think with good expectations, you can have a fantastic working relationship with your surgeons. Without them, it becomes a nightmare.

Here are my HM group’s rules for elective orthopedic surgery:

- Orthopedics handles all pain medications and VTE prophylaxis, including discharge prescriptions.

- Medicine handles all admit and discharge medication reconciliation (“med rec”).

- There is shared discussion on:

- Need for transfusion; and

- The VTE prophylaxis when a patient already is on chronic anticoagulation.

We do not vary from this protocol. I never adjust a patient’s pain medications. Even the floor nurses know this. Because I’m doing the admit med rec, it also means that the patient doesn’t have their HCTZ continued after 600cc of EBL and spinal anesthesia.

The system works because the rules are clear and the communication is consistent. This does not mean that we cover the orthopedic service at night. They are equally responsible for their patients under the items outlined above. In my view—and this might sound simplistic—the surgeon caused the post-op pain, so they should be responsible for managing it. On VTE prophylaxis, I might take a more nuanced view, but for our surgeons, they own the wound and the post-op follow-up, so they get the choice on what agent to use.

Would I accept an arrangement in which I covered all the orthopedic issues out of regular hours? Nope—not when they have primary responsibility for the case; they should always be directly available to the nurse. I think that anything else would be a system ripe for abuse.

Our exact rules will not work for every situation, but I would strongly encourage the two basic tenets from above: No. 1, the hospitalist should primarily admit and manage elderly hip fractures, and No. 2, clear rules of engagement should be established with your orthopedic or surgery group. It’s a discussion worth having during daylight hours, because trying to figure out the rules at 3 in the morning rarely ends well.

One of our providers wants to use adult hospitalists for coverage of inpatient orthopedic surgery patients. Is this acceptable practice? Are there qualifiers?

–Libby Gardner

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Let’s see how far we can tackle this open-ended question. There has been lots of discussion on the topic of comanagement in the past by people eminently more qualified than I am. Still, it never hurts to take a fresh look at things.

For one, on the subject of admissions, I am a firm believer that hospitalists should admit all adult hip fractures. The overwhelming majority of the time, these patients are elderly with comorbid conditions. Sure, they are going to get their hip fixed, because the alternative is usually unacceptable, but some thought needs to go into the process. The orthopedic surgeon sees a hip that needs fixing and not much else. When issues like renal failure, afib, CHF, prior DVT, or dementia are present, hospitalists should take charge of the case. It is the best way to ensure that the patient receives optimal medical care and the documentation that goes along with it. I love our orthopedic surgeons, but I don’t want them primarily admitting, managing, and discharging my elderly patients. Let the surgeon do what they do best, which is operate, and leave the rest to us.

On the subject of orthopedic trauma, I take the exact opposite tack—this is not something for which I or most of my colleagues have expertise. A young, healthy patient with trauma should be admitted by the orthopedic service; that patient population’s complications are much more likely to be directly related to their trauma.

When it comes to elective surgery, when the admitting surgeon (orthopedic or otherwise) wants the help of a hospitalist, then I think it is of paramount importance to have clear “rules of engagement.” I think with good expectations, you can have a fantastic working relationship with your surgeons. Without them, it becomes a nightmare.

Here are my HM group’s rules for elective orthopedic surgery:

- Orthopedics handles all pain medications and VTE prophylaxis, including discharge prescriptions.

- Medicine handles all admit and discharge medication reconciliation (“med rec”).

- There is shared discussion on:

- Need for transfusion; and

- The VTE prophylaxis when a patient already is on chronic anticoagulation.

We do not vary from this protocol. I never adjust a patient’s pain medications. Even the floor nurses know this. Because I’m doing the admit med rec, it also means that the patient doesn’t have their HCTZ continued after 600cc of EBL and spinal anesthesia.

The system works because the rules are clear and the communication is consistent. This does not mean that we cover the orthopedic service at night. They are equally responsible for their patients under the items outlined above. In my view—and this might sound simplistic—the surgeon caused the post-op pain, so they should be responsible for managing it. On VTE prophylaxis, I might take a more nuanced view, but for our surgeons, they own the wound and the post-op follow-up, so they get the choice on what agent to use.

Would I accept an arrangement in which I covered all the orthopedic issues out of regular hours? Nope—not when they have primary responsibility for the case; they should always be directly available to the nurse. I think that anything else would be a system ripe for abuse.

Our exact rules will not work for every situation, but I would strongly encourage the two basic tenets from above: No. 1, the hospitalist should primarily admit and manage elderly hip fractures, and No. 2, clear rules of engagement should be established with your orthopedic or surgery group. It’s a discussion worth having during daylight hours, because trying to figure out the rules at 3 in the morning rarely ends well.

ICU Hospitalist Model Improves Quality of Care for Critically Ill Patients

Despite calls for board-certified intensivists to manage all critically ill patients, only a third of hospitalized ICU patients currently are seen by such a specialist—mostly because there are not enough of them to go around.1,2 More and more hospitalists, especially those in community hospitals, are working in ICUs (see “The Critical-Care Debate,”). With the proper training, that can be a good thing for patients and hospitalists, according to a Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) abstract presented at HM12 in San Diego.3

Lead author and hospitalist Mark Krivopal, MD, SFHM, formerly with TeamHealth in California and now vice president and medical director of clinical integration and hospital medicine at Steward Health Care in Boston, outlined a program at California’s Lodi Memorial Hospital that identified a group of hospitalists who had experience in caring for critically ill patients and credentials to perform such procedures as central-line placements, intubations, and ventilator management. The select group of TeamHealth hospitalists completed a two-day “Fundamentals of Critical Care Support” course offered by the Society of Critical Care Medicine (www.sccm.org), then began covering the ICU in shifts from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. The program was so successful early on that hospital administration requested that it expand to a 24-hour service.

An ICU hospitalist program needs to be a partnership, Dr. Krivopal says. Essential oversight at Lodi Memorial is provided by the hospital’s sole pulmonologist.

Preliminary data showed a 35% reduction in ventilator days and 22% reduction in ICU stays, Dr. Krivopal says. The hospital also reports high satisfaction from nurses and other staff. Additional metrics, such as cost savings and patient satisfaction, are under review.

“So long as the level of training is sufficient, this is an approach that definitely should be explored,” he says, adding that young internists have many of the skills needed for ICU work. “But if you don’t keep those skills up [with practice] after residency, you lose them.”

References

- The Leapfrog Group. ICU physician staffing fact sheet. The Leapfrog Group website. Available at: http://www.leapfroggroup.org/media/file/Leapfrog-ICU_Physician_Staffing_Fact_Sheet.pdf. Accessed Aug. 29, 2012.

- Health Resources & Services Administration. Report to Congress: The critical care workforce: a study of the supply and demand for critical care physicians. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services website. Available at: http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/reports/studycriticalcarephys.pdf. Accessed Aug. 29, 2012.

- Krivopal M, Hlaing M, Felber R, Himebaugh R. ICU hospitalist: a novel method of care for the critically ill patients in economically lean times. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(Suppl 2):192.

Despite calls for board-certified intensivists to manage all critically ill patients, only a third of hospitalized ICU patients currently are seen by such a specialist—mostly because there are not enough of them to go around.1,2 More and more hospitalists, especially those in community hospitals, are working in ICUs (see “The Critical-Care Debate,”). With the proper training, that can be a good thing for patients and hospitalists, according to a Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) abstract presented at HM12 in San Diego.3

Lead author and hospitalist Mark Krivopal, MD, SFHM, formerly with TeamHealth in California and now vice president and medical director of clinical integration and hospital medicine at Steward Health Care in Boston, outlined a program at California’s Lodi Memorial Hospital that identified a group of hospitalists who had experience in caring for critically ill patients and credentials to perform such procedures as central-line placements, intubations, and ventilator management. The select group of TeamHealth hospitalists completed a two-day “Fundamentals of Critical Care Support” course offered by the Society of Critical Care Medicine (www.sccm.org), then began covering the ICU in shifts from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. The program was so successful early on that hospital administration requested that it expand to a 24-hour service.

An ICU hospitalist program needs to be a partnership, Dr. Krivopal says. Essential oversight at Lodi Memorial is provided by the hospital’s sole pulmonologist.

Preliminary data showed a 35% reduction in ventilator days and 22% reduction in ICU stays, Dr. Krivopal says. The hospital also reports high satisfaction from nurses and other staff. Additional metrics, such as cost savings and patient satisfaction, are under review.

“So long as the level of training is sufficient, this is an approach that definitely should be explored,” he says, adding that young internists have many of the skills needed for ICU work. “But if you don’t keep those skills up [with practice] after residency, you lose them.”

References

- The Leapfrog Group. ICU physician staffing fact sheet. The Leapfrog Group website. Available at: http://www.leapfroggroup.org/media/file/Leapfrog-ICU_Physician_Staffing_Fact_Sheet.pdf. Accessed Aug. 29, 2012.

- Health Resources & Services Administration. Report to Congress: The critical care workforce: a study of the supply and demand for critical care physicians. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services website. Available at: http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/reports/studycriticalcarephys.pdf. Accessed Aug. 29, 2012.

- Krivopal M, Hlaing M, Felber R, Himebaugh R. ICU hospitalist: a novel method of care for the critically ill patients in economically lean times. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(Suppl 2):192.

Despite calls for board-certified intensivists to manage all critically ill patients, only a third of hospitalized ICU patients currently are seen by such a specialist—mostly because there are not enough of them to go around.1,2 More and more hospitalists, especially those in community hospitals, are working in ICUs (see “The Critical-Care Debate,”). With the proper training, that can be a good thing for patients and hospitalists, according to a Research, Innovations, and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) abstract presented at HM12 in San Diego.3

Lead author and hospitalist Mark Krivopal, MD, SFHM, formerly with TeamHealth in California and now vice president and medical director of clinical integration and hospital medicine at Steward Health Care in Boston, outlined a program at California’s Lodi Memorial Hospital that identified a group of hospitalists who had experience in caring for critically ill patients and credentials to perform such procedures as central-line placements, intubations, and ventilator management. The select group of TeamHealth hospitalists completed a two-day “Fundamentals of Critical Care Support” course offered by the Society of Critical Care Medicine (www.sccm.org), then began covering the ICU in shifts from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. The program was so successful early on that hospital administration requested that it expand to a 24-hour service.

An ICU hospitalist program needs to be a partnership, Dr. Krivopal says. Essential oversight at Lodi Memorial is provided by the hospital’s sole pulmonologist.

Preliminary data showed a 35% reduction in ventilator days and 22% reduction in ICU stays, Dr. Krivopal says. The hospital also reports high satisfaction from nurses and other staff. Additional metrics, such as cost savings and patient satisfaction, are under review.

“So long as the level of training is sufficient, this is an approach that definitely should be explored,” he says, adding that young internists have many of the skills needed for ICU work. “But if you don’t keep those skills up [with practice] after residency, you lose them.”

References

- The Leapfrog Group. ICU physician staffing fact sheet. The Leapfrog Group website. Available at: http://www.leapfroggroup.org/media/file/Leapfrog-ICU_Physician_Staffing_Fact_Sheet.pdf. Accessed Aug. 29, 2012.

- Health Resources & Services Administration. Report to Congress: The critical care workforce: a study of the supply and demand for critical care physicians. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services website. Available at: http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/reports/studycriticalcarephys.pdf. Accessed Aug. 29, 2012.

- Krivopal M, Hlaing M, Felber R, Himebaugh R. ICU hospitalist: a novel method of care for the critically ill patients in economically lean times. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(Suppl 2):192.

Win Whitcomb: Hospital Readmissions Penalties Start Now

The uproar and confusion over readmissions penalties has consumed umpteen hours of senior leaders’ time (especially that of CFOs), not to mention that of front-line nurses, case managers, quality-improvement (QI) coordinators, hospitalists, and others involved in discharge planning and ensuring a safe transition for patients out of the hospital. For many, the math is fuzzy, and for most, the return on investment is even fuzzier. After all, avoided readmissions are lost revenue to those who are running a business known as an acute-care hospital.

Let me start with the conclusion: Eliminating avoidable readmissions is the right thing to do, period. But the financial downside to doing so is probably greater than any upside realized through avoidance of the penalties that began affecting hospital payments on Oct. 1—at least in the fee-for-service world we live in. At some point in the future, when most patients are under a global payment, the math might be clearer, but today, penalties probably won’t offset lost revenue from reduced readmissions added to the cost of paying lots of people to work in meetings (and at the bedside) to devise better care transitions. (Caveat: If your hospital is bursting at the seams with full occupancy, reducing readmissions and replacing them with higher-reimbursing patients, such as those undergoing elective major surgery, likely will be a net financial gain for your hospital.)

Part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) will reduce total Medicare DRG reimbursement for hospitals beginning in fiscal-year 2013 based on actual 30-day readmission rates for myocardial infarction (MI), heart failure (HF), and pneumonia that are in excess of risk-adjusted expected rates. The reduction is capped at 1% in 2013, 2% in 2014, and 3% in 2015 and beyond. Hospital readmission rates are based on calculated baseline rates using Medicare data from July 1, 2008, to June 30, 2011.

Cost of a Readmissions-Reduction Program

How much does it cost for a hospital to implement a care-transitions program—such as SHM’s Project BOOST—to reduce readmissions? Last year, I interviewed a dozen hospitals that successfully implemented SHM’s formal mentored implementation program. The result? In the first year of the program, hospitals spent about $170,000 on training and staff time devoted to the project.

Lost Revenue

Let’s look at a sample penalty calculation, then examine a scenario sizing up how revenue is lost when a hospital is successful in reducing readmissions. The ACA defines the payments for excess readmissions as:

The number of patients with the applicable condition (HF, MI, or pneumonia) multiplied by the base DRG payment made for those patients multiplied by the percentage of readmissions beyond the expected.

As an example, let’s take a hospital that treats 500 pneumonia patients (# with the applicable condition), has a base DRG payment for pneumonia of $5,000, and a readmission rate that is 4% higher than expected (in this example, the actual rate is 25% and the expected rate is 24%; 1/25=4%). The penalty is 500 X $5,000 X .04, or $100,000. We’ll assume that the readmission rate for myocardial infarction and heart failure are less than expected, so the total penalty is $100,000.

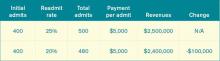

Let’s say the hospital works hard to decrease pneumonia readmissions from 25% to 20% and avoids the penalty. As outlined in Table 1, the hospital will lose $100,000 in revenue (admittedly, reducing readmissions to 20% from 25% represents a big jump, but this is for illustration purposes—we haven’t added in lost revenue from reduced readmissions for other conditions). What’s the final cost of avoiding the $100,000 readmission penalty? Lost revenue of $100,000 plus the cost of implementing the readmission reduction program of $170,000=$270,000.

Why Are We Doing This?

I see the value in care transitions and readmissions-reduction programs, such as Project BOOST, first and foremost as a way to improve patient safety; as such, if implemented effectively, they are likely worth the investment. Second, their value lies in the preparation all hospitals and health systems should be undergoing to remain market-competitive and solvent under global payment systems. Because the penalties in the HRRP might come with lost revenues and the costs of program implementation, be clear about your team’s motivation for reducing readmissions. Your CFO will see to it if I don’t.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

The uproar and confusion over readmissions penalties has consumed umpteen hours of senior leaders’ time (especially that of CFOs), not to mention that of front-line nurses, case managers, quality-improvement (QI) coordinators, hospitalists, and others involved in discharge planning and ensuring a safe transition for patients out of the hospital. For many, the math is fuzzy, and for most, the return on investment is even fuzzier. After all, avoided readmissions are lost revenue to those who are running a business known as an acute-care hospital.

Let me start with the conclusion: Eliminating avoidable readmissions is the right thing to do, period. But the financial downside to doing so is probably greater than any upside realized through avoidance of the penalties that began affecting hospital payments on Oct. 1—at least in the fee-for-service world we live in. At some point in the future, when most patients are under a global payment, the math might be clearer, but today, penalties probably won’t offset lost revenue from reduced readmissions added to the cost of paying lots of people to work in meetings (and at the bedside) to devise better care transitions. (Caveat: If your hospital is bursting at the seams with full occupancy, reducing readmissions and replacing them with higher-reimbursing patients, such as those undergoing elective major surgery, likely will be a net financial gain for your hospital.)

Part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) will reduce total Medicare DRG reimbursement for hospitals beginning in fiscal-year 2013 based on actual 30-day readmission rates for myocardial infarction (MI), heart failure (HF), and pneumonia that are in excess of risk-adjusted expected rates. The reduction is capped at 1% in 2013, 2% in 2014, and 3% in 2015 and beyond. Hospital readmission rates are based on calculated baseline rates using Medicare data from July 1, 2008, to June 30, 2011.

Cost of a Readmissions-Reduction Program

How much does it cost for a hospital to implement a care-transitions program—such as SHM’s Project BOOST—to reduce readmissions? Last year, I interviewed a dozen hospitals that successfully implemented SHM’s formal mentored implementation program. The result? In the first year of the program, hospitals spent about $170,000 on training and staff time devoted to the project.

Lost Revenue

Let’s look at a sample penalty calculation, then examine a scenario sizing up how revenue is lost when a hospital is successful in reducing readmissions. The ACA defines the payments for excess readmissions as:

The number of patients with the applicable condition (HF, MI, or pneumonia) multiplied by the base DRG payment made for those patients multiplied by the percentage of readmissions beyond the expected.

As an example, let’s take a hospital that treats 500 pneumonia patients (# with the applicable condition), has a base DRG payment for pneumonia of $5,000, and a readmission rate that is 4% higher than expected (in this example, the actual rate is 25% and the expected rate is 24%; 1/25=4%). The penalty is 500 X $5,000 X .04, or $100,000. We’ll assume that the readmission rate for myocardial infarction and heart failure are less than expected, so the total penalty is $100,000.

Let’s say the hospital works hard to decrease pneumonia readmissions from 25% to 20% and avoids the penalty. As outlined in Table 1, the hospital will lose $100,000 in revenue (admittedly, reducing readmissions to 20% from 25% represents a big jump, but this is for illustration purposes—we haven’t added in lost revenue from reduced readmissions for other conditions). What’s the final cost of avoiding the $100,000 readmission penalty? Lost revenue of $100,000 plus the cost of implementing the readmission reduction program of $170,000=$270,000.

Why Are We Doing This?

I see the value in care transitions and readmissions-reduction programs, such as Project BOOST, first and foremost as a way to improve patient safety; as such, if implemented effectively, they are likely worth the investment. Second, their value lies in the preparation all hospitals and health systems should be undergoing to remain market-competitive and solvent under global payment systems. Because the penalties in the HRRP might come with lost revenues and the costs of program implementation, be clear about your team’s motivation for reducing readmissions. Your CFO will see to it if I don’t.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

The uproar and confusion over readmissions penalties has consumed umpteen hours of senior leaders’ time (especially that of CFOs), not to mention that of front-line nurses, case managers, quality-improvement (QI) coordinators, hospitalists, and others involved in discharge planning and ensuring a safe transition for patients out of the hospital. For many, the math is fuzzy, and for most, the return on investment is even fuzzier. After all, avoided readmissions are lost revenue to those who are running a business known as an acute-care hospital.

Let me start with the conclusion: Eliminating avoidable readmissions is the right thing to do, period. But the financial downside to doing so is probably greater than any upside realized through avoidance of the penalties that began affecting hospital payments on Oct. 1—at least in the fee-for-service world we live in. At some point in the future, when most patients are under a global payment, the math might be clearer, but today, penalties probably won’t offset lost revenue from reduced readmissions added to the cost of paying lots of people to work in meetings (and at the bedside) to devise better care transitions. (Caveat: If your hospital is bursting at the seams with full occupancy, reducing readmissions and replacing them with higher-reimbursing patients, such as those undergoing elective major surgery, likely will be a net financial gain for your hospital.)

Part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) will reduce total Medicare DRG reimbursement for hospitals beginning in fiscal-year 2013 based on actual 30-day readmission rates for myocardial infarction (MI), heart failure (HF), and pneumonia that are in excess of risk-adjusted expected rates. The reduction is capped at 1% in 2013, 2% in 2014, and 3% in 2015 and beyond. Hospital readmission rates are based on calculated baseline rates using Medicare data from July 1, 2008, to June 30, 2011.

Cost of a Readmissions-Reduction Program

How much does it cost for a hospital to implement a care-transitions program—such as SHM’s Project BOOST—to reduce readmissions? Last year, I interviewed a dozen hospitals that successfully implemented SHM’s formal mentored implementation program. The result? In the first year of the program, hospitals spent about $170,000 on training and staff time devoted to the project.

Lost Revenue

Let’s look at a sample penalty calculation, then examine a scenario sizing up how revenue is lost when a hospital is successful in reducing readmissions. The ACA defines the payments for excess readmissions as:

The number of patients with the applicable condition (HF, MI, or pneumonia) multiplied by the base DRG payment made for those patients multiplied by the percentage of readmissions beyond the expected.

As an example, let’s take a hospital that treats 500 pneumonia patients (# with the applicable condition), has a base DRG payment for pneumonia of $5,000, and a readmission rate that is 4% higher than expected (in this example, the actual rate is 25% and the expected rate is 24%; 1/25=4%). The penalty is 500 X $5,000 X .04, or $100,000. We’ll assume that the readmission rate for myocardial infarction and heart failure are less than expected, so the total penalty is $100,000.

Let’s say the hospital works hard to decrease pneumonia readmissions from 25% to 20% and avoids the penalty. As outlined in Table 1, the hospital will lose $100,000 in revenue (admittedly, reducing readmissions to 20% from 25% represents a big jump, but this is for illustration purposes—we haven’t added in lost revenue from reduced readmissions for other conditions). What’s the final cost of avoiding the $100,000 readmission penalty? Lost revenue of $100,000 plus the cost of implementing the readmission reduction program of $170,000=$270,000.

Why Are We Doing This?

I see the value in care transitions and readmissions-reduction programs, such as Project BOOST, first and foremost as a way to improve patient safety; as such, if implemented effectively, they are likely worth the investment. Second, their value lies in the preparation all hospitals and health systems should be undergoing to remain market-competitive and solvent under global payment systems. Because the penalties in the HRRP might come with lost revenues and the costs of program implementation, be clear about your team’s motivation for reducing readmissions. Your CFO will see to it if I don’t.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

12 Things Cardiologists Think Hospitalists Need to Know

Only about a third of ideal candidates with heart failure are currently treated with [aldosterone antagonists], even though it markedly improves outcome and is Class I-recommended in the guidelines.

—Gregg Fonarow, MD, co-chief, University of California at Los Angeles division of cardiology, chair, American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines program steering committee

You might not have done a fellowship in cardiology, but quite often you probably feel like a cardiologist. Hospitalists frequently attend to patients on observation for heart problems and help manage even the most complex patients.

Often, you are working alongside the cardiologist. But other times, you’re on your own. Hospitalists are expected to carry an increasingly heavy load when it comes to heart-failure patients and many other kinds of patients with specialized disorders. It can be hard to keep up with what you need to know.

Top Twelve

- Recognize the new importance of beta-blockers for heart failure, and go with the best of them.

- It’s not readmissions that are the problem—it’s avoidable readmissions.

- New interventional technologies will mean more complex patients, so be ready.

- Aldosterone antagonists, though probably underutilized, can be very effective but require caution.

- Switching from IV diuretics to an oral regimen calls for careful monitoring.

- Patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction have outcomes over the longer haul similar to those with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. And in preserved ejection fraction cases, the contributing illnesses must be addressed.

- Inotropic agents can do more harm than good.

- Pay attention to the ins and outs of new antiplatelet therapies.

- Bridging anticoagulant therapy in patients going for electrophysiology procedures should be done only some, not most, of the time.

- Some non-STEMI patients might benefit from getting to the catheterization lab quickly.

- Beware the idiosyncrasies of new anticoagulants.

- Be cognizant of stent thrombosis and how to manage it.

The Hospitalist spoke to several cardiologists about the latest in treatments, technologies, and HM’s role in the system of care. The following are their suggestions for what you really need to know about treating patients with heart conditions.

1) Recognize the new importance of beta-blockers for heart failure, and go with the best of them.

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensive receptor blockers have been part of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) core measures for heart failure for a long time, but beta-blockers at hospital discharge only recently have been added as American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/American Medical Association–Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement measures for heart failure.1

“For those with heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, very old and outdated concepts would have talked about potentially holding the beta-blocker during hospitalization for heart failure—or not initiating until the patient was an outpatient,” says Gregg Fonarow, MD, co-chief of the University of California at Los Angeles’ division of cardiology and chair of the steering committee for the American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines program. “[But] the guidelines and evidence, and often performance measures, linked to them are now explicit about initiating or maintaining beta-blockers during the heart-failure hospitalization.”

Beta-blockers should be initiated as patients are stabilized before discharge. Dr. Fonarow suggests hospitalists use only one of the three evidence-based therapies: carvedilol, metoprolol succinate, or bisoprolol.

“Many physicians have been using metoprolol tartrate or atenolol in heart-failure patients,” Dr. Fonarow says. “These are not known to improve clinical outcomes. So here’s an example where the specific medication is absolutely, critically important.”

2) It’s not readmissions that are the problem—it’s avoidable readmissions.

“The modifier is very important,” says Clyde Yancy, MD, chief of the division of cardiology at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago. “Heart failure continues to be a problematic disease. Many patients now do really well, but some do not. Those patients are symptomatic and may require frequent hospitalizations for stabilization. We should not disallow or misdirect those patients who need inpatient care from receiving such because of an arbitrary incentive to reduce rehospitalizations out of fear of punitive financial damages. The unforeseen risks here are real.”

Dr. Yancy says studies based on CMS data have found that institutions with higher readmission rates have lower 30-day mortality rates.2 He cautions hospitalists to be “very thoughtful about an overzealous embrace of reducing all readmissions for heart failure.” Instead, the goal should be to limit the “avoidable readmissions.”

“And for the patient that clearly has advanced disease,” he says, “rather than triaging them away from the hospital, we really should be very respectful of their disease. Keep those patients where disease-modifying interventions can be deployed, and we can work to achieve the best possible outcome for those that have the most advanced disease.”

3) New interventional technologies will mean more complex patients, so be ready.

Advances in interventional procedures, including transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) and endoscopic mitral valve repair, will translate into a new population of highly complex patients. Many of these patients will be in their 80s or 90s.

“It’s a whole new paradigm shift of technology,” says John Harold, MD, president-elect of the American College of Cardiology and past chief of staff and department of medicine clinical chief of staff at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. “Very often, the hospitalist is at the front dealing with all of these issues.”

Many of these patients have other problems, including renal insufficiency, diabetes, and the like.

“They have all sorts of other things going on simultaneously, so very often the hospitalist becomes … the point person in dealing with all of these issues,” Dr. Harold says.

4) Aldosterone antagonists, though probably underutilized, can be very effective but require caution.

Aldosterone antagonists can greatly improve outcomes and reduce hospitalization in heart-failure patients, but they have to be used with very careful dosing and patient selection, Dr. Fonarow says. And they require early follow-up once patients are discharged.

“Only about a third of ideal candidates with heart failure are currently treated with this agent, even though it markedly improves outcome and is Class I-recommended in the guidelines,” Dr. Fonarow says. “But this is one where it needs to be started at appropriate low doses, with meticulous monitoring in both the inpatient and the outpatient setting, early follow-up, and early laboratory checks.”

5) Switching from IV diuretics to an oral regimen calls for careful monitoring.

Transitioning patients from IV diuretics to oral regimens is an area rife with mistakes, Dr. Fonarow says. It requires a lot of “meticulous attention to proper potassium supplementation and monitoring of renal function and electrolyte levels,” he says.

Medication reconciliation—“med rec”—is especially important during the transition from inpatient to outpatient.

“There are common medication errors that are made during this transition,” Dr. Fonarow says. “Hospitalists, along with other [care team] members, can really play a critically important role in trying to reduce that risk.”

6) Patients with heart failure with preserved ejection

fraction have outcomes over the longer haul similar to those with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. And in preserved ejection fraction cases, the contributing illnesses must be addressed.

“We really can’t exercise a thought economy that just says, ‘Extrapolate the evidence-based therapies for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction’ and expect good outcomes,” Dr. Yancy says. “That’s not the case. We don’t have an evidence base to substantiate that.”

He says one or more common comorbidities (e.g. atrial fibrillation, hypertension, obesity, diabetes, renal insufficiency) are present in 90% of patients with preserved ejection fraction. Treatment of those comorbidities—for example, rate control in afib patients, lowering the blood pressure in hypertension patients—has to be done with care.

“We should recognize that the therapy for this condition, albeit absent any specifically indicated interventions that will change its natural history, can still be skillfully constructed,” Dr. Yancy says. “But that construct needs to reflect the recommended, guideline-driven interventions for the concomitant other comorbidities.”

7) Inotropic agents can do more harm than good.

For patients who aren’t in cardiogenic shock, using inotropic agents doesn’t help. In fact, it might actually hurt. Dr. Fonarow says studies have shown these agents can “prolong length of stay, cause complications, and increase mortality risk.”

He notes that the use of inotropes should be avoided, or if it’s being considered, a cardiologist with knowledge and experience in heart failure should be involved in the treatment and care.

Statements about avoiding inotropes in heart failure, except under very specific circumstances, have been “incredibly strengthened” recently in the American College of Cardiology and Heart Failure Society of America guidelines.3

8) Pay attention to the ins and outs of new antiplatelet therapies.

—John Harold, MD, president-elect, American College of Cardiology, former chief of staff, department of medicine, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles

Hospitalists caring for acute coronary syndrome patients need to familiarize themselves with updated guidelines and additional therapies that are now available, Dr. Fonarow says. New antiplatelet therapies (e.g. prasugrel and ticagrelor) are available as part of the armamentarium, along with the mainstay clopidogrel.

“These therapies lower the risk of recurrent events, lowered the risk of stent thrombosis,” he says. “In the case of ticagrelor, it actually lowered all-cause mortality. These are important new therapies, with new guideline recommendations, that all hospitalists should be aware of.”

9) Bridging anticoagulant therapy in patients going for electrophysiology procedures should be done only some, not most, of the time.

“Patients getting such devices as pacemakers or implantable cardioverter defribrillators (ICD) installed tend not to need bridging,” says Joaquin Cigarroa, MD, clinical chief of cardiology at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland.

He says it’s actually “safer” to do the procedure when patients “are on oral antithrombotics than switching them from an oral agent, and bridging with low- molecular-weight- or unfractionated heparin.”

“It’s a big deal,” Dr. Cigarroa adds, because it is risky to have elderly and frail patients on multiple antithrombotics. “Hemorrhagic complications in cardiology patients still occurs very frequently, so really be attuned to estimating bleeding risk and making sure that we’re dosing antithrombotics appropriately. Bridging should be the minority of patients, not the majority of patients.”

10) Some non-STEMI patients might benefit from getting to the catheterization lab quickly.

Door-to-balloon time is recognized as critical for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients, but more recent work—such as in the TIMACS trial—finds benefits of early revascularization for some non-STEMI patients as well.2

“This trial showed that among higher-risk patients, using a validated risk score, that those patients did benefit from an early approach, meaning going to the cath lab in the first 12 hours of hospitalization,” Dr. Fonarow says. “We now have more information about the optimal timing of coronary angiography and potential revascularization of higher-risk patients with non-ST-segment elevation MI.”

11) Beware the idiosyncrasies of new anticoagulants.

The introduction of dabigatran and rivaroxaban (and, perhaps soon, apixaban) to the array of anticoagulant therapies brings a new slate of considerations for hospitalists, Dr. Harold says.

“For the majority of these, there’s no specific way to reverse the anticoagulant effect in the event of a major bleeding event,” he says. “There’s no simple antidote. And the effect can last up to 12 to 24 hours, depending on the renal function. This is what the hospitalist will be called to deal with: bleeding complications in patients who have these newer anticoagulants on board.”

Dr. Fonarow says that the new CHA2DS2-VASc score has been found to do a better job than the traditional CHADS2 score in assessing afib stroke risk.4

12) Be cognizant of stent thrombosis and how to manage it.

Dr. Harold says that most hospitalists probably are up to date on drug-eluting stents and the risk of stopping dual antiplatelet therapy within several months of implant, but that doesn’t mean they won’t treat patients whose primary-care physicians (PCPs) aren’t up to date. He recommends working on these cases with hematologists.

“That knowledge is not widespread in terms of the internal-medicine community,” he says. “I’ve seen situations where patients have had their Plavix stopped for colonoscopies and they’ve had stent thrombosis. It’s this knowledge of cardiac patients who come in with recent deployment of drug-eluting stents who may end up having other issues.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

References

- 2009 Focused Update: ACCF/AHA Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults. Circulation. 2009;119:1977-2016 an HFSA 2010 Comprehensive Heart Failure Practice Guideline. J Cardiac Failure. 2010;16(6):475-539.

- Gorodeski EZ, Starling RC, Blackstone EH. Are all readmissions bad readmissions? N Engl J Med. 2010;363:297-298.

- Mehta SR, Granger CB, Boden WE, et al. Early versus delayed invasive intervention in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(21):2165-2175.

- Olesen JB, Torp-Pedersen C, Hansen ML, Lip GY. The value of the CHA2DS2-VASc score for refining stroke risk stratification in patients with atrial fibrillation with a CHADS2 score 0-1: a nationwide cohort study. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107(6):1172-1179.

- Associations between outpatient heart failure process-of-care measures and mortality. Circulation. 2011;123(15):1601-1610.

Only about a third of ideal candidates with heart failure are currently treated with [aldosterone antagonists], even though it markedly improves outcome and is Class I-recommended in the guidelines.

—Gregg Fonarow, MD, co-chief, University of California at Los Angeles division of cardiology, chair, American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines program steering committee

You might not have done a fellowship in cardiology, but quite often you probably feel like a cardiologist. Hospitalists frequently attend to patients on observation for heart problems and help manage even the most complex patients.

Often, you are working alongside the cardiologist. But other times, you’re on your own. Hospitalists are expected to carry an increasingly heavy load when it comes to heart-failure patients and many other kinds of patients with specialized disorders. It can be hard to keep up with what you need to know.

Top Twelve

- Recognize the new importance of beta-blockers for heart failure, and go with the best of them.

- It’s not readmissions that are the problem—it’s avoidable readmissions.

- New interventional technologies will mean more complex patients, so be ready.

- Aldosterone antagonists, though probably underutilized, can be very effective but require caution.

- Switching from IV diuretics to an oral regimen calls for careful monitoring.

- Patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction have outcomes over the longer haul similar to those with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. And in preserved ejection fraction cases, the contributing illnesses must be addressed.

- Inotropic agents can do more harm than good.

- Pay attention to the ins and outs of new antiplatelet therapies.

- Bridging anticoagulant therapy in patients going for electrophysiology procedures should be done only some, not most, of the time.

- Some non-STEMI patients might benefit from getting to the catheterization lab quickly.

- Beware the idiosyncrasies of new anticoagulants.

- Be cognizant of stent thrombosis and how to manage it.

The Hospitalist spoke to several cardiologists about the latest in treatments, technologies, and HM’s role in the system of care. The following are their suggestions for what you really need to know about treating patients with heart conditions.

1) Recognize the new importance of beta-blockers for heart failure, and go with the best of them.

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensive receptor blockers have been part of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) core measures for heart failure for a long time, but beta-blockers at hospital discharge only recently have been added as American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/American Medical Association–Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement measures for heart failure.1

“For those with heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, very old and outdated concepts would have talked about potentially holding the beta-blocker during hospitalization for heart failure—or not initiating until the patient was an outpatient,” says Gregg Fonarow, MD, co-chief of the University of California at Los Angeles’ division of cardiology and chair of the steering committee for the American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines program. “[But] the guidelines and evidence, and often performance measures, linked to them are now explicit about initiating or maintaining beta-blockers during the heart-failure hospitalization.”

Beta-blockers should be initiated as patients are stabilized before discharge. Dr. Fonarow suggests hospitalists use only one of the three evidence-based therapies: carvedilol, metoprolol succinate, or bisoprolol.

“Many physicians have been using metoprolol tartrate or atenolol in heart-failure patients,” Dr. Fonarow says. “These are not known to improve clinical outcomes. So here’s an example where the specific medication is absolutely, critically important.”

2) It’s not readmissions that are the problem—it’s avoidable readmissions.

“The modifier is very important,” says Clyde Yancy, MD, chief of the division of cardiology at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago. “Heart failure continues to be a problematic disease. Many patients now do really well, but some do not. Those patients are symptomatic and may require frequent hospitalizations for stabilization. We should not disallow or misdirect those patients who need inpatient care from receiving such because of an arbitrary incentive to reduce rehospitalizations out of fear of punitive financial damages. The unforeseen risks here are real.”

Dr. Yancy says studies based on CMS data have found that institutions with higher readmission rates have lower 30-day mortality rates.2 He cautions hospitalists to be “very thoughtful about an overzealous embrace of reducing all readmissions for heart failure.” Instead, the goal should be to limit the “avoidable readmissions.”

“And for the patient that clearly has advanced disease,” he says, “rather than triaging them away from the hospital, we really should be very respectful of their disease. Keep those patients where disease-modifying interventions can be deployed, and we can work to achieve the best possible outcome for those that have the most advanced disease.”

3) New interventional technologies will mean more complex patients, so be ready.

Advances in interventional procedures, including transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) and endoscopic mitral valve repair, will translate into a new population of highly complex patients. Many of these patients will be in their 80s or 90s.

“It’s a whole new paradigm shift of technology,” says John Harold, MD, president-elect of the American College of Cardiology and past chief of staff and department of medicine clinical chief of staff at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. “Very often, the hospitalist is at the front dealing with all of these issues.”

Many of these patients have other problems, including renal insufficiency, diabetes, and the like.

“They have all sorts of other things going on simultaneously, so very often the hospitalist becomes … the point person in dealing with all of these issues,” Dr. Harold says.

4) Aldosterone antagonists, though probably underutilized, can be very effective but require caution.

Aldosterone antagonists can greatly improve outcomes and reduce hospitalization in heart-failure patients, but they have to be used with very careful dosing and patient selection, Dr. Fonarow says. And they require early follow-up once patients are discharged.

“Only about a third of ideal candidates with heart failure are currently treated with this agent, even though it markedly improves outcome and is Class I-recommended in the guidelines,” Dr. Fonarow says. “But this is one where it needs to be started at appropriate low doses, with meticulous monitoring in both the inpatient and the outpatient setting, early follow-up, and early laboratory checks.”

5) Switching from IV diuretics to an oral regimen calls for careful monitoring.

Transitioning patients from IV diuretics to oral regimens is an area rife with mistakes, Dr. Fonarow says. It requires a lot of “meticulous attention to proper potassium supplementation and monitoring of renal function and electrolyte levels,” he says.

Medication reconciliation—“med rec”—is especially important during the transition from inpatient to outpatient.

“There are common medication errors that are made during this transition,” Dr. Fonarow says. “Hospitalists, along with other [care team] members, can really play a critically important role in trying to reduce that risk.”

6) Patients with heart failure with preserved ejection

fraction have outcomes over the longer haul similar to those with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. And in preserved ejection fraction cases, the contributing illnesses must be addressed.

“We really can’t exercise a thought economy that just says, ‘Extrapolate the evidence-based therapies for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction’ and expect good outcomes,” Dr. Yancy says. “That’s not the case. We don’t have an evidence base to substantiate that.”

He says one or more common comorbidities (e.g. atrial fibrillation, hypertension, obesity, diabetes, renal insufficiency) are present in 90% of patients with preserved ejection fraction. Treatment of those comorbidities—for example, rate control in afib patients, lowering the blood pressure in hypertension patients—has to be done with care.

“We should recognize that the therapy for this condition, albeit absent any specifically indicated interventions that will change its natural history, can still be skillfully constructed,” Dr. Yancy says. “But that construct needs to reflect the recommended, guideline-driven interventions for the concomitant other comorbidities.”

7) Inotropic agents can do more harm than good.

For patients who aren’t in cardiogenic shock, using inotropic agents doesn’t help. In fact, it might actually hurt. Dr. Fonarow says studies have shown these agents can “prolong length of stay, cause complications, and increase mortality risk.”

He notes that the use of inotropes should be avoided, or if it’s being considered, a cardiologist with knowledge and experience in heart failure should be involved in the treatment and care.

Statements about avoiding inotropes in heart failure, except under very specific circumstances, have been “incredibly strengthened” recently in the American College of Cardiology and Heart Failure Society of America guidelines.3

8) Pay attention to the ins and outs of new antiplatelet therapies.

—John Harold, MD, president-elect, American College of Cardiology, former chief of staff, department of medicine, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles

Hospitalists caring for acute coronary syndrome patients need to familiarize themselves with updated guidelines and additional therapies that are now available, Dr. Fonarow says. New antiplatelet therapies (e.g. prasugrel and ticagrelor) are available as part of the armamentarium, along with the mainstay clopidogrel.

“These therapies lower the risk of recurrent events, lowered the risk of stent thrombosis,” he says. “In the case of ticagrelor, it actually lowered all-cause mortality. These are important new therapies, with new guideline recommendations, that all hospitalists should be aware of.”

9) Bridging anticoagulant therapy in patients going for electrophysiology procedures should be done only some, not most, of the time.

“Patients getting such devices as pacemakers or implantable cardioverter defribrillators (ICD) installed tend not to need bridging,” says Joaquin Cigarroa, MD, clinical chief of cardiology at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland.

He says it’s actually “safer” to do the procedure when patients “are on oral antithrombotics than switching them from an oral agent, and bridging with low- molecular-weight- or unfractionated heparin.”

“It’s a big deal,” Dr. Cigarroa adds, because it is risky to have elderly and frail patients on multiple antithrombotics. “Hemorrhagic complications in cardiology patients still occurs very frequently, so really be attuned to estimating bleeding risk and making sure that we’re dosing antithrombotics appropriately. Bridging should be the minority of patients, not the majority of patients.”

10) Some non-STEMI patients might benefit from getting to the catheterization lab quickly.

Door-to-balloon time is recognized as critical for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients, but more recent work—such as in the TIMACS trial—finds benefits of early revascularization for some non-STEMI patients as well.2

“This trial showed that among higher-risk patients, using a validated risk score, that those patients did benefit from an early approach, meaning going to the cath lab in the first 12 hours of hospitalization,” Dr. Fonarow says. “We now have more information about the optimal timing of coronary angiography and potential revascularization of higher-risk patients with non-ST-segment elevation MI.”

11) Beware the idiosyncrasies of new anticoagulants.

The introduction of dabigatran and rivaroxaban (and, perhaps soon, apixaban) to the array of anticoagulant therapies brings a new slate of considerations for hospitalists, Dr. Harold says.

“For the majority of these, there’s no specific way to reverse the anticoagulant effect in the event of a major bleeding event,” he says. “There’s no simple antidote. And the effect can last up to 12 to 24 hours, depending on the renal function. This is what the hospitalist will be called to deal with: bleeding complications in patients who have these newer anticoagulants on board.”

Dr. Fonarow says that the new CHA2DS2-VASc score has been found to do a better job than the traditional CHADS2 score in assessing afib stroke risk.4

12) Be cognizant of stent thrombosis and how to manage it.

Dr. Harold says that most hospitalists probably are up to date on drug-eluting stents and the risk of stopping dual antiplatelet therapy within several months of implant, but that doesn’t mean they won’t treat patients whose primary-care physicians (PCPs) aren’t up to date. He recommends working on these cases with hematologists.

“That knowledge is not widespread in terms of the internal-medicine community,” he says. “I’ve seen situations where patients have had their Plavix stopped for colonoscopies and they’ve had stent thrombosis. It’s this knowledge of cardiac patients who come in with recent deployment of drug-eluting stents who may end up having other issues.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer in South Florida.

References

- 2009 Focused Update: ACCF/AHA Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults. Circulation. 2009;119:1977-2016 an HFSA 2010 Comprehensive Heart Failure Practice Guideline. J Cardiac Failure. 2010;16(6):475-539.

- Gorodeski EZ, Starling RC, Blackstone EH. Are all readmissions bad readmissions? N Engl J Med. 2010;363:297-298.

- Mehta SR, Granger CB, Boden WE, et al. Early versus delayed invasive intervention in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(21):2165-2175.

- Olesen JB, Torp-Pedersen C, Hansen ML, Lip GY. The value of the CHA2DS2-VASc score for refining stroke risk stratification in patients with atrial fibrillation with a CHADS2 score 0-1: a nationwide cohort study. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107(6):1172-1179.

- Associations between outpatient heart failure process-of-care measures and mortality. Circulation. 2011;123(15):1601-1610.

Only about a third of ideal candidates with heart failure are currently treated with [aldosterone antagonists], even though it markedly improves outcome and is Class I-recommended in the guidelines.

—Gregg Fonarow, MD, co-chief, University of California at Los Angeles division of cardiology, chair, American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines program steering committee

You might not have done a fellowship in cardiology, but quite often you probably feel like a cardiologist. Hospitalists frequently attend to patients on observation for heart problems and help manage even the most complex patients.

Often, you are working alongside the cardiologist. But other times, you’re on your own. Hospitalists are expected to carry an increasingly heavy load when it comes to heart-failure patients and many other kinds of patients with specialized disorders. It can be hard to keep up with what you need to know.

Top Twelve

- Recognize the new importance of beta-blockers for heart failure, and go with the best of them.

- It’s not readmissions that are the problem—it’s avoidable readmissions.

- New interventional technologies will mean more complex patients, so be ready.

- Aldosterone antagonists, though probably underutilized, can be very effective but require caution.

- Switching from IV diuretics to an oral regimen calls for careful monitoring.

- Patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction have outcomes over the longer haul similar to those with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. And in preserved ejection fraction cases, the contributing illnesses must be addressed.

- Inotropic agents can do more harm than good.

- Pay attention to the ins and outs of new antiplatelet therapies.

- Bridging anticoagulant therapy in patients going for electrophysiology procedures should be done only some, not most, of the time.

- Some non-STEMI patients might benefit from getting to the catheterization lab quickly.

- Beware the idiosyncrasies of new anticoagulants.

- Be cognizant of stent thrombosis and how to manage it.

The Hospitalist spoke to several cardiologists about the latest in treatments, technologies, and HM’s role in the system of care. The following are their suggestions for what you really need to know about treating patients with heart conditions.

1) Recognize the new importance of beta-blockers for heart failure, and go with the best of them.

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensive receptor blockers have been part of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) core measures for heart failure for a long time, but beta-blockers at hospital discharge only recently have been added as American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/American Medical Association–Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement measures for heart failure.1

“For those with heart failure and reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, very old and outdated concepts would have talked about potentially holding the beta-blocker during hospitalization for heart failure—or not initiating until the patient was an outpatient,” says Gregg Fonarow, MD, co-chief of the University of California at Los Angeles’ division of cardiology and chair of the steering committee for the American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines program. “[But] the guidelines and evidence, and often performance measures, linked to them are now explicit about initiating or maintaining beta-blockers during the heart-failure hospitalization.”

Beta-blockers should be initiated as patients are stabilized before discharge. Dr. Fonarow suggests hospitalists use only one of the three evidence-based therapies: carvedilol, metoprolol succinate, or bisoprolol.