User login

Living liver donation safety supported in single-center study

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – A single-center analysis of complications following living liver donation found a low rate of severe complications, and a high quality of life among donors. The results are similar to what has been seen in a previous multicenter study in the United States, and the authors hope that the results can help inform potential donors and their physicians.

There is a significant shortage of deceased liver donors, leading to the death of about 3,500 liver transplant hopefuls in 2016, compared with about 2,900 who received a transplant. Living donor transplant was developed and first attempted in 1996 as an attempt to counter this shortage, and for a brief period it was popular, peaking at 500 donor surgeries in 2001. But that year the death of a donor occurred in New York and received widespread publicity.

Overall, though, the study showed relatively few complications, and that donors reported good quality of life. “There was a slight dip in health-related quality of life at 5 years and 10 years, but at all times the donors had significantly better quality of life compared to the standard population,” said Dr. Chinnakotla, clinical director of pediatric transplantation at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

The researchers examined long-term complications and quality of life among 176 liver donors who underwent surgery between 1997 and 2016 at the University of Minnesota. At total of 140 donors underwent a right-lobe hepatectomy without middle hepatic vein, 14 underwent right lobe with middle hepatic vein, 4 underwent left lobe, and 18 underwent left lateral segmentectomy.

The researchers then analyzed complications graded by the Clavien scale. They found that 59.1% of right-lobe donors experienced no complications at all; 5.8% had Clavien scale 1 complications, meaning something abnormal occurred but required no intervention; and 27.3% had a Clavien 2 complication, requiring pharmaceutical treatment, a blood transfusion, or parenteral nutrition. Clavien 3a complications, which required an intervention without general anesthesia, occurred in 1.9% of cases, and Clavien 3b complications, which required anesthesia, occurred in 5.8%.

A total of 81.8% of left-lobe donors experienced no complications, 4.5% had a Clavien 1 complication, and 13.6% a Clavien 2. There were no Clavien 3 or 4 complications in left-lobe donors.

Overall, the incidence of Clavien grade 3 or higher complications was 7%, there were no complications involving organ failure, and there were no deaths.

Quality of life, as measured by the 36-item Short Form Health Survey and an internally designed donor-specific survey, was higher among recipients than in the general population at all time points. The primary long-term complaints were incisional discomfort, which ranged from about 23% to 38% in frequency, and intolerance to fatty meals, which had a frequency of 20%-30%, and is likely attributable to accompanying cholecystectomy, according to Dr. Chinnakotla.

“The overall results appear to have been excellent,” said William C. Chapman, MD, who was invited by the meeting organizers to review and comment on the study. Dr. Chapman is surgical director of transplant surgery at Washington University in St. Louis.

Dr. Chapman also noted that some studies in Asia have looked at reducing complications in donors, while avoiding a small-for-size graft, by using two left-lobe grafts from separate living donors (Liver Transpl 2015;21[11]1438-48). “We haven’t been brave enough to do that in the United States, but I think that is a strategy we can look forward to in the future,” said Dr. Chinnakotla.

No funding source was disclosed.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – A single-center analysis of complications following living liver donation found a low rate of severe complications, and a high quality of life among donors. The results are similar to what has been seen in a previous multicenter study in the United States, and the authors hope that the results can help inform potential donors and their physicians.

There is a significant shortage of deceased liver donors, leading to the death of about 3,500 liver transplant hopefuls in 2016, compared with about 2,900 who received a transplant. Living donor transplant was developed and first attempted in 1996 as an attempt to counter this shortage, and for a brief period it was popular, peaking at 500 donor surgeries in 2001. But that year the death of a donor occurred in New York and received widespread publicity.

Overall, though, the study showed relatively few complications, and that donors reported good quality of life. “There was a slight dip in health-related quality of life at 5 years and 10 years, but at all times the donors had significantly better quality of life compared to the standard population,” said Dr. Chinnakotla, clinical director of pediatric transplantation at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

The researchers examined long-term complications and quality of life among 176 liver donors who underwent surgery between 1997 and 2016 at the University of Minnesota. At total of 140 donors underwent a right-lobe hepatectomy without middle hepatic vein, 14 underwent right lobe with middle hepatic vein, 4 underwent left lobe, and 18 underwent left lateral segmentectomy.

The researchers then analyzed complications graded by the Clavien scale. They found that 59.1% of right-lobe donors experienced no complications at all; 5.8% had Clavien scale 1 complications, meaning something abnormal occurred but required no intervention; and 27.3% had a Clavien 2 complication, requiring pharmaceutical treatment, a blood transfusion, or parenteral nutrition. Clavien 3a complications, which required an intervention without general anesthesia, occurred in 1.9% of cases, and Clavien 3b complications, which required anesthesia, occurred in 5.8%.

A total of 81.8% of left-lobe donors experienced no complications, 4.5% had a Clavien 1 complication, and 13.6% a Clavien 2. There were no Clavien 3 or 4 complications in left-lobe donors.

Overall, the incidence of Clavien grade 3 or higher complications was 7%, there were no complications involving organ failure, and there were no deaths.

Quality of life, as measured by the 36-item Short Form Health Survey and an internally designed donor-specific survey, was higher among recipients than in the general population at all time points. The primary long-term complaints were incisional discomfort, which ranged from about 23% to 38% in frequency, and intolerance to fatty meals, which had a frequency of 20%-30%, and is likely attributable to accompanying cholecystectomy, according to Dr. Chinnakotla.

“The overall results appear to have been excellent,” said William C. Chapman, MD, who was invited by the meeting organizers to review and comment on the study. Dr. Chapman is surgical director of transplant surgery at Washington University in St. Louis.

Dr. Chapman also noted that some studies in Asia have looked at reducing complications in donors, while avoiding a small-for-size graft, by using two left-lobe grafts from separate living donors (Liver Transpl 2015;21[11]1438-48). “We haven’t been brave enough to do that in the United States, but I think that is a strategy we can look forward to in the future,” said Dr. Chinnakotla.

No funding source was disclosed.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ. – A single-center analysis of complications following living liver donation found a low rate of severe complications, and a high quality of life among donors. The results are similar to what has been seen in a previous multicenter study in the United States, and the authors hope that the results can help inform potential donors and their physicians.

There is a significant shortage of deceased liver donors, leading to the death of about 3,500 liver transplant hopefuls in 2016, compared with about 2,900 who received a transplant. Living donor transplant was developed and first attempted in 1996 as an attempt to counter this shortage, and for a brief period it was popular, peaking at 500 donor surgeries in 2001. But that year the death of a donor occurred in New York and received widespread publicity.

Overall, though, the study showed relatively few complications, and that donors reported good quality of life. “There was a slight dip in health-related quality of life at 5 years and 10 years, but at all times the donors had significantly better quality of life compared to the standard population,” said Dr. Chinnakotla, clinical director of pediatric transplantation at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

The researchers examined long-term complications and quality of life among 176 liver donors who underwent surgery between 1997 and 2016 at the University of Minnesota. At total of 140 donors underwent a right-lobe hepatectomy without middle hepatic vein, 14 underwent right lobe with middle hepatic vein, 4 underwent left lobe, and 18 underwent left lateral segmentectomy.

The researchers then analyzed complications graded by the Clavien scale. They found that 59.1% of right-lobe donors experienced no complications at all; 5.8% had Clavien scale 1 complications, meaning something abnormal occurred but required no intervention; and 27.3% had a Clavien 2 complication, requiring pharmaceutical treatment, a blood transfusion, or parenteral nutrition. Clavien 3a complications, which required an intervention without general anesthesia, occurred in 1.9% of cases, and Clavien 3b complications, which required anesthesia, occurred in 5.8%.

A total of 81.8% of left-lobe donors experienced no complications, 4.5% had a Clavien 1 complication, and 13.6% a Clavien 2. There were no Clavien 3 or 4 complications in left-lobe donors.

Overall, the incidence of Clavien grade 3 or higher complications was 7%, there were no complications involving organ failure, and there were no deaths.

Quality of life, as measured by the 36-item Short Form Health Survey and an internally designed donor-specific survey, was higher among recipients than in the general population at all time points. The primary long-term complaints were incisional discomfort, which ranged from about 23% to 38% in frequency, and intolerance to fatty meals, which had a frequency of 20%-30%, and is likely attributable to accompanying cholecystectomy, according to Dr. Chinnakotla.

“The overall results appear to have been excellent,” said William C. Chapman, MD, who was invited by the meeting organizers to review and comment on the study. Dr. Chapman is surgical director of transplant surgery at Washington University in St. Louis.

Dr. Chapman also noted that some studies in Asia have looked at reducing complications in donors, while avoiding a small-for-size graft, by using two left-lobe grafts from separate living donors (Liver Transpl 2015;21[11]1438-48). “We haven’t been brave enough to do that in the United States, but I think that is a strategy we can look forward to in the future,” said Dr. Chinnakotla.

No funding source was disclosed.

AT WSA 2017

Heart transplantation: Preop LVAD erases adverse impact of pulmonary hypertension

COLORADO SPRINGS – Reconsideration of the role of pulmonary hypertension in heart transplant outcomes is appropriate in the emerging era of the use of left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) as bridge to transplant, according to Ann C. Gaffey, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“Pulmonary hypertension secondary to congestive heart failure more than likely can be reversed to the values acceptable for heart transplant by the use of an LVAD. For bridge-to-transplant patients, pretransplant pulmonary hypertension does not affect recipient outcomes post transplantation,” she said at the annual meeting of the Western Thoracic Surgical Association.

Vasodilators are prescribed in an effort to reduce PH; however, 40% of patients with PH are unresponsive to the medications and have therefore been excluded from consideration as potential candidates for a donor heart.

But the growing use of LVADs as a bridge to transplant has changed all that, Dr. Gaffey said. As supporting evidence, she presented a retrospective analysis of the United Network for Organ Sharing database on adult heart transplants from mid-2004 through the end of 2014.

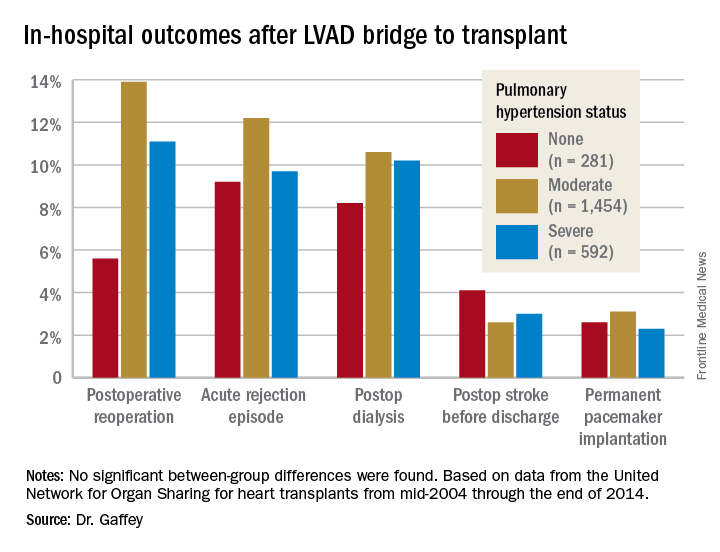

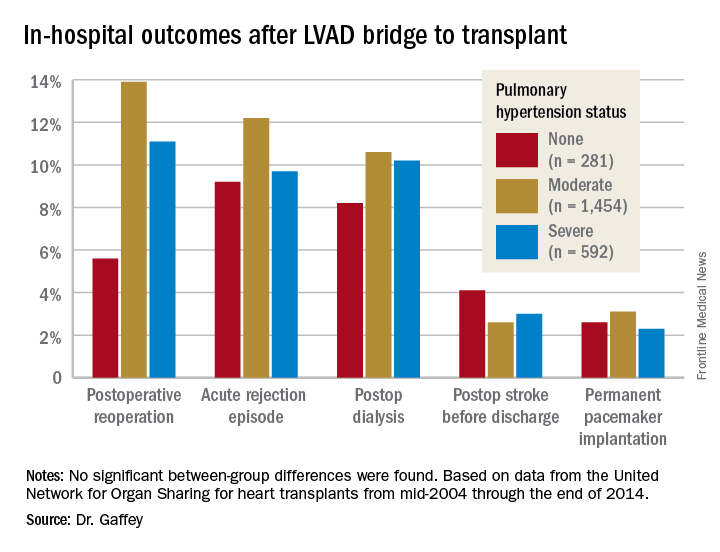

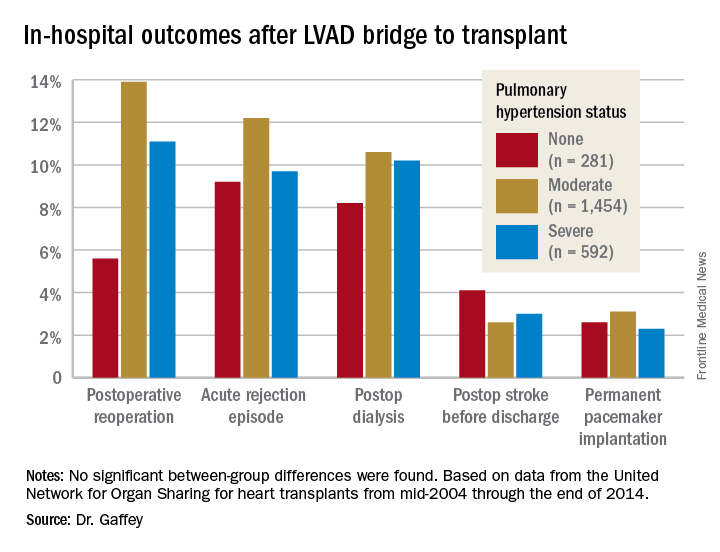

The review turned up 3,951 heart transplant recipients who had been bridged to transplant with an LVAD. Dr. Gaffey and her coinvestigators divided them into three groups: 281 patients without pretransplant PH; 1,454 with moderate PH as defined by 1-3 Wood units; and 592 with severe PH and more than 3 Wood units.

The three groups didn’t differ in terms of age, sex, wait-list time, or the prevalence of diabetes or renal, liver, or cerebrovascular disease. Nor did their donors differ in age, sex, left ventricular function, or allograft ischemic time.

Key in-hospital outcomes were similar between the groups with no, mild, and severe PH.

Moreover, there was no between-group difference in the rate of rejection at 1 year. Five-year survival rates were closely similar in the three groups, in the mid-70s.

Audience member Nahush A. Mokadam, MD, rose to praise Dr. Gaffey’s report.

“This is a great and important study. I think as a group we have been too conservative with pulmonary hypertension, so thank you for shining a good light on it,” said Dr. Mokadam of the University of Washington, Seattle.

Dr. Gaffey reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

COLORADO SPRINGS – Reconsideration of the role of pulmonary hypertension in heart transplant outcomes is appropriate in the emerging era of the use of left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) as bridge to transplant, according to Ann C. Gaffey, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“Pulmonary hypertension secondary to congestive heart failure more than likely can be reversed to the values acceptable for heart transplant by the use of an LVAD. For bridge-to-transplant patients, pretransplant pulmonary hypertension does not affect recipient outcomes post transplantation,” she said at the annual meeting of the Western Thoracic Surgical Association.

Vasodilators are prescribed in an effort to reduce PH; however, 40% of patients with PH are unresponsive to the medications and have therefore been excluded from consideration as potential candidates for a donor heart.

But the growing use of LVADs as a bridge to transplant has changed all that, Dr. Gaffey said. As supporting evidence, she presented a retrospective analysis of the United Network for Organ Sharing database on adult heart transplants from mid-2004 through the end of 2014.

The review turned up 3,951 heart transplant recipients who had been bridged to transplant with an LVAD. Dr. Gaffey and her coinvestigators divided them into three groups: 281 patients without pretransplant PH; 1,454 with moderate PH as defined by 1-3 Wood units; and 592 with severe PH and more than 3 Wood units.

The three groups didn’t differ in terms of age, sex, wait-list time, or the prevalence of diabetes or renal, liver, or cerebrovascular disease. Nor did their donors differ in age, sex, left ventricular function, or allograft ischemic time.

Key in-hospital outcomes were similar between the groups with no, mild, and severe PH.

Moreover, there was no between-group difference in the rate of rejection at 1 year. Five-year survival rates were closely similar in the three groups, in the mid-70s.

Audience member Nahush A. Mokadam, MD, rose to praise Dr. Gaffey’s report.

“This is a great and important study. I think as a group we have been too conservative with pulmonary hypertension, so thank you for shining a good light on it,” said Dr. Mokadam of the University of Washington, Seattle.

Dr. Gaffey reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

COLORADO SPRINGS – Reconsideration of the role of pulmonary hypertension in heart transplant outcomes is appropriate in the emerging era of the use of left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) as bridge to transplant, according to Ann C. Gaffey, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“Pulmonary hypertension secondary to congestive heart failure more than likely can be reversed to the values acceptable for heart transplant by the use of an LVAD. For bridge-to-transplant patients, pretransplant pulmonary hypertension does not affect recipient outcomes post transplantation,” she said at the annual meeting of the Western Thoracic Surgical Association.

Vasodilators are prescribed in an effort to reduce PH; however, 40% of patients with PH are unresponsive to the medications and have therefore been excluded from consideration as potential candidates for a donor heart.

But the growing use of LVADs as a bridge to transplant has changed all that, Dr. Gaffey said. As supporting evidence, she presented a retrospective analysis of the United Network for Organ Sharing database on adult heart transplants from mid-2004 through the end of 2014.

The review turned up 3,951 heart transplant recipients who had been bridged to transplant with an LVAD. Dr. Gaffey and her coinvestigators divided them into three groups: 281 patients without pretransplant PH; 1,454 with moderate PH as defined by 1-3 Wood units; and 592 with severe PH and more than 3 Wood units.

The three groups didn’t differ in terms of age, sex, wait-list time, or the prevalence of diabetes or renal, liver, or cerebrovascular disease. Nor did their donors differ in age, sex, left ventricular function, or allograft ischemic time.

Key in-hospital outcomes were similar between the groups with no, mild, and severe PH.

Moreover, there was no between-group difference in the rate of rejection at 1 year. Five-year survival rates were closely similar in the three groups, in the mid-70s.

Audience member Nahush A. Mokadam, MD, rose to praise Dr. Gaffey’s report.

“This is a great and important study. I think as a group we have been too conservative with pulmonary hypertension, so thank you for shining a good light on it,” said Dr. Mokadam of the University of Washington, Seattle.

Dr. Gaffey reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

AT THE WTSA ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: It’s time to reconsider the practice of excluding patients with pulmonary hypertension from consideration for a donor heart.

Data source: A retrospective analysis of the United Network for Organ Sharing database including outcomes out to 5 years on 3,951 heart transplant recipients who had been bridged to transplant with an LVAD, most of whom had moderate or severe pulmonary hypertension before transplant.

Disclosures: This study was conducted free of commercial support. The presenter reported having no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

Study examines intestinal microbiota role post liver transplant

WASHINGTON – During and after liver transplant, the reaction of the intestinal microbiota may be a critical determinant of outcomes; preliminary data from a cohort study may provide some clarification of what modulates gut microbiota post transplantation and shed light on predictive factors.

Anna-Catrin Uhlemann, MD, PhD, of Columbia University Medical Center, New York, noted that several studies in recent years sought to clarify influences on gut microbiota in people receiving liver transplants, but “there are still a number of important gaps in knowledge, including what exactly is the longitudinal evolution of the host transplant microbiome and what is the predictive value of pre- and early posttransplant dysbiosis on outcomes and complications.”

The researchers collected more than 1,000 samples to screen for colonization by the following MDR organisms: carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), Enterobacteriaceae resistant to third-generation cephalosporins (ESBL), and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE). Over the 1-year follow-up period, 19% (P =.031) of patients had CRE colonization associated with subsequent infection, 41% (P = .003) had ESBL colonization, and 46% (P = .021) had VRE colonization, Dr. Uhlemann said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. The researchers then selected 484 samples for sequencing of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene to determine the composition of gut microbiota.

The study used two indexes to determine the alpha diversity of microbiota: the Chao index to estimate richness and the Shannon diversity index to determine the abundance of species in different settings. “We observed dynamic temporal evolution of alpha diversity and taxa abundance over the 1-year follow-up period,” Dr. Uhlemann said. “The diagnosis, the Child-Pugh class, and changes in perioperative antibiotics were important predictors of posttransplant alpha diversity.”

The study also found that Enterobacteriaceae and enterococci increased post transplant in general and as MDR organisms, and that a patient’s MDR status was an important modulator of the posttransplant microbiome, as was the lack of protective operational taxonomic units (OTUs).

The researchers evaluated the relative abundance of taxa and beta diversity. For example, pretransplant patients with a Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score greater than 25 showed enrichment of Enterobacteriaceae as well as different taxa of the Bacteroidiaceae, while those with MELD scores below 25 showed enrichment of Veillonellaceae. “The significance of this is not clear yet,” Dr. Uhlemann said.

Liver disease severity can also influence gut microbes. Those with Child-Pugh class C disease have the highest numbers in terms of richness and lowest in terms of diversity, Dr. Uhlemann said. “However, at the moment when we are looking at the differential abundance of the taxa, we don’t see quite as clear a pattern, although we noticed in the high group a higher abundance of Bacteroidiaceae,” she said.

Hepatitis B and C patients also presented divergent microbiota profiles. Hepatitis B virus patients “in general are always relatively healthy, and we actually see that these indices are relatively preserved,” Dr. Uhlemann said. “When we look at hepatitis C, however, we see that these patients are starting off quite low and then have an increase in alpha-diversity measures at around month 6.” A subset of patients with alcoholic liver disease also didn’t reach higher Chao and Shannon levels until 6 months after transplant.

“We also find that adjustment of periodic antibiotics for allergy or history of prior infection is significantly associated with a decrease in alpha diversity several months into the posttransplant course,” said Dr. Uhlemann. This is driven by an increase in the abundance of Enterococcaceae and Enterobacteriaceae. “And when we look at MDR colonization as a predictor of alpha diversity, we see that those who have MDR colonization, irrespective of the species, also have the lower alpha diversity.”

The researchers also started to look at pretransplant alpha diversity as a predictor of transplant outcomes, and while the analysis is still in progress, the Shannon indices were significantly different between patients who died and those who survived a year. “There was a trend for significant differences for posttransplant infection and the length of the hospital stay,” Dr. Uhlemann said. “However, we did not see any association with posttransplant ICU readmission, rejection, or VRE complications.”

She added that future analyses are needed to further evaluate the interaction between the clinical comorbidities in the microbiome and vice versa.

Dr. Uhlemann disclosed links to Merck.

WASHINGTON – During and after liver transplant, the reaction of the intestinal microbiota may be a critical determinant of outcomes; preliminary data from a cohort study may provide some clarification of what modulates gut microbiota post transplantation and shed light on predictive factors.

Anna-Catrin Uhlemann, MD, PhD, of Columbia University Medical Center, New York, noted that several studies in recent years sought to clarify influences on gut microbiota in people receiving liver transplants, but “there are still a number of important gaps in knowledge, including what exactly is the longitudinal evolution of the host transplant microbiome and what is the predictive value of pre- and early posttransplant dysbiosis on outcomes and complications.”

The researchers collected more than 1,000 samples to screen for colonization by the following MDR organisms: carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), Enterobacteriaceae resistant to third-generation cephalosporins (ESBL), and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE). Over the 1-year follow-up period, 19% (P =.031) of patients had CRE colonization associated with subsequent infection, 41% (P = .003) had ESBL colonization, and 46% (P = .021) had VRE colonization, Dr. Uhlemann said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. The researchers then selected 484 samples for sequencing of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene to determine the composition of gut microbiota.

The study used two indexes to determine the alpha diversity of microbiota: the Chao index to estimate richness and the Shannon diversity index to determine the abundance of species in different settings. “We observed dynamic temporal evolution of alpha diversity and taxa abundance over the 1-year follow-up period,” Dr. Uhlemann said. “The diagnosis, the Child-Pugh class, and changes in perioperative antibiotics were important predictors of posttransplant alpha diversity.”

The study also found that Enterobacteriaceae and enterococci increased post transplant in general and as MDR organisms, and that a patient’s MDR status was an important modulator of the posttransplant microbiome, as was the lack of protective operational taxonomic units (OTUs).

The researchers evaluated the relative abundance of taxa and beta diversity. For example, pretransplant patients with a Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score greater than 25 showed enrichment of Enterobacteriaceae as well as different taxa of the Bacteroidiaceae, while those with MELD scores below 25 showed enrichment of Veillonellaceae. “The significance of this is not clear yet,” Dr. Uhlemann said.

Liver disease severity can also influence gut microbes. Those with Child-Pugh class C disease have the highest numbers in terms of richness and lowest in terms of diversity, Dr. Uhlemann said. “However, at the moment when we are looking at the differential abundance of the taxa, we don’t see quite as clear a pattern, although we noticed in the high group a higher abundance of Bacteroidiaceae,” she said.

Hepatitis B and C patients also presented divergent microbiota profiles. Hepatitis B virus patients “in general are always relatively healthy, and we actually see that these indices are relatively preserved,” Dr. Uhlemann said. “When we look at hepatitis C, however, we see that these patients are starting off quite low and then have an increase in alpha-diversity measures at around month 6.” A subset of patients with alcoholic liver disease also didn’t reach higher Chao and Shannon levels until 6 months after transplant.

“We also find that adjustment of periodic antibiotics for allergy or history of prior infection is significantly associated with a decrease in alpha diversity several months into the posttransplant course,” said Dr. Uhlemann. This is driven by an increase in the abundance of Enterococcaceae and Enterobacteriaceae. “And when we look at MDR colonization as a predictor of alpha diversity, we see that those who have MDR colonization, irrespective of the species, also have the lower alpha diversity.”

The researchers also started to look at pretransplant alpha diversity as a predictor of transplant outcomes, and while the analysis is still in progress, the Shannon indices were significantly different between patients who died and those who survived a year. “There was a trend for significant differences for posttransplant infection and the length of the hospital stay,” Dr. Uhlemann said. “However, we did not see any association with posttransplant ICU readmission, rejection, or VRE complications.”

She added that future analyses are needed to further evaluate the interaction between the clinical comorbidities in the microbiome and vice versa.

Dr. Uhlemann disclosed links to Merck.

WASHINGTON – During and after liver transplant, the reaction of the intestinal microbiota may be a critical determinant of outcomes; preliminary data from a cohort study may provide some clarification of what modulates gut microbiota post transplantation and shed light on predictive factors.

Anna-Catrin Uhlemann, MD, PhD, of Columbia University Medical Center, New York, noted that several studies in recent years sought to clarify influences on gut microbiota in people receiving liver transplants, but “there are still a number of important gaps in knowledge, including what exactly is the longitudinal evolution of the host transplant microbiome and what is the predictive value of pre- and early posttransplant dysbiosis on outcomes and complications.”

The researchers collected more than 1,000 samples to screen for colonization by the following MDR organisms: carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE), Enterobacteriaceae resistant to third-generation cephalosporins (ESBL), and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE). Over the 1-year follow-up period, 19% (P =.031) of patients had CRE colonization associated with subsequent infection, 41% (P = .003) had ESBL colonization, and 46% (P = .021) had VRE colonization, Dr. Uhlemann said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. The researchers then selected 484 samples for sequencing of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene to determine the composition of gut microbiota.

The study used two indexes to determine the alpha diversity of microbiota: the Chao index to estimate richness and the Shannon diversity index to determine the abundance of species in different settings. “We observed dynamic temporal evolution of alpha diversity and taxa abundance over the 1-year follow-up period,” Dr. Uhlemann said. “The diagnosis, the Child-Pugh class, and changes in perioperative antibiotics were important predictors of posttransplant alpha diversity.”

The study also found that Enterobacteriaceae and enterococci increased post transplant in general and as MDR organisms, and that a patient’s MDR status was an important modulator of the posttransplant microbiome, as was the lack of protective operational taxonomic units (OTUs).

The researchers evaluated the relative abundance of taxa and beta diversity. For example, pretransplant patients with a Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score greater than 25 showed enrichment of Enterobacteriaceae as well as different taxa of the Bacteroidiaceae, while those with MELD scores below 25 showed enrichment of Veillonellaceae. “The significance of this is not clear yet,” Dr. Uhlemann said.

Liver disease severity can also influence gut microbes. Those with Child-Pugh class C disease have the highest numbers in terms of richness and lowest in terms of diversity, Dr. Uhlemann said. “However, at the moment when we are looking at the differential abundance of the taxa, we don’t see quite as clear a pattern, although we noticed in the high group a higher abundance of Bacteroidiaceae,” she said.

Hepatitis B and C patients also presented divergent microbiota profiles. Hepatitis B virus patients “in general are always relatively healthy, and we actually see that these indices are relatively preserved,” Dr. Uhlemann said. “When we look at hepatitis C, however, we see that these patients are starting off quite low and then have an increase in alpha-diversity measures at around month 6.” A subset of patients with alcoholic liver disease also didn’t reach higher Chao and Shannon levels until 6 months after transplant.

“We also find that adjustment of periodic antibiotics for allergy or history of prior infection is significantly associated with a decrease in alpha diversity several months into the posttransplant course,” said Dr. Uhlemann. This is driven by an increase in the abundance of Enterococcaceae and Enterobacteriaceae. “And when we look at MDR colonization as a predictor of alpha diversity, we see that those who have MDR colonization, irrespective of the species, also have the lower alpha diversity.”

The researchers also started to look at pretransplant alpha diversity as a predictor of transplant outcomes, and while the analysis is still in progress, the Shannon indices were significantly different between patients who died and those who survived a year. “There was a trend for significant differences for posttransplant infection and the length of the hospital stay,” Dr. Uhlemann said. “However, we did not see any association with posttransplant ICU readmission, rejection, or VRE complications.”

She added that future analyses are needed to further evaluate the interaction between the clinical comorbidities in the microbiome and vice versa.

Dr. Uhlemann disclosed links to Merck.

AT THE LIVER MEETING 2017

Key clinical point: The presence or lack of specific modulators of gut microbiota may influence outcomes of liver transplantation.

Major finding: Over a 1-year follow-up period, 19% of patients had colonization with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, 41% had Enterobacteriaceae resistant to third-generation cephalosporins, and 46% had vancomycin-resistant enterococci associated with subsequent infections.

Data source: A prospective longitudinal cohort study of 323 patients, 125 of whom completed 1 year of follow-up.

Disclosures: Dr. Uhlemann disclosed receiving research funding from Merck.

VIDEO: Rapid influenza test obviates empiric antivirals

TORONTO – A test that only requires a maximum 2-hour wait for results was highly accurate at detecting influenza and respiratory syncytial virus infection in lung transplant patients, according to research presented at the CHEST annual meeting on Oct. 30.

This rapid and highly accurate test for detecting three common respiratory viruses has dramatically cut the need for empiric treatments and the risk for causing nosocomial infections in lung transplant patients who develop severe upper respiratory infections, Macé M. Schuurmans, MD, noted during the presentation.

This study involved 100 consecutive lung transplant patients who presented at Zurich University Hospital with signs of severe upper respiratory infection. The researchers ran the rapid and standard diagnostic tests for each patient and found that, relative to the standard test, the rapid test had positive and negative predictive values of 95%.

The number of empiric treatments with oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and ribavirin to treat a suspected influenza or respiratory syncytial virus infection (RSV) has “strongly diminished” by about two-thirds, noted Dr. Schuurmans, who is a pulmonologist at the hospital.

Until the rapid test became available, Dr. Shuurmans and his associates used a standard polymerase chain reaction test that takes 36-48 hours to yield a result. Using this test made treating patients empirically with oseltamivir and oral antibiotics for a couple of days a necessity, he said in a video interview. The older test also required isolating patients to avoid the potential spread of influenza or RSV in the hospital.

The rapid test, which became available for U.S. use in early 2017, covers influenza A and B and RSV in a single test with a single mouth-swab specimen.

“We now routinely use the rapid test and don’t prescribe empiric antivirals or antibiotics as often,” Dr. Schuurmans said. “There is much less drug cost and fewer potential adverse effects from empiric treatment.” Specimens still also undergo conventional testing, however, because that can identify eight additional viruses that the rapid test doesn’t cover.

Dr. Schuurmans acknowledged that further study needs to assess the cost-benefit of the rapid test to confirm that its added expense is offset by reduced expenses for empiric treatment and hospital isolation.

He had no disclosures. The study received no commercial support.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

TORONTO – A test that only requires a maximum 2-hour wait for results was highly accurate at detecting influenza and respiratory syncytial virus infection in lung transplant patients, according to research presented at the CHEST annual meeting on Oct. 30.

This rapid and highly accurate test for detecting three common respiratory viruses has dramatically cut the need for empiric treatments and the risk for causing nosocomial infections in lung transplant patients who develop severe upper respiratory infections, Macé M. Schuurmans, MD, noted during the presentation.

This study involved 100 consecutive lung transplant patients who presented at Zurich University Hospital with signs of severe upper respiratory infection. The researchers ran the rapid and standard diagnostic tests for each patient and found that, relative to the standard test, the rapid test had positive and negative predictive values of 95%.

The number of empiric treatments with oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and ribavirin to treat a suspected influenza or respiratory syncytial virus infection (RSV) has “strongly diminished” by about two-thirds, noted Dr. Schuurmans, who is a pulmonologist at the hospital.

Until the rapid test became available, Dr. Shuurmans and his associates used a standard polymerase chain reaction test that takes 36-48 hours to yield a result. Using this test made treating patients empirically with oseltamivir and oral antibiotics for a couple of days a necessity, he said in a video interview. The older test also required isolating patients to avoid the potential spread of influenza or RSV in the hospital.

The rapid test, which became available for U.S. use in early 2017, covers influenza A and B and RSV in a single test with a single mouth-swab specimen.

“We now routinely use the rapid test and don’t prescribe empiric antivirals or antibiotics as often,” Dr. Schuurmans said. “There is much less drug cost and fewer potential adverse effects from empiric treatment.” Specimens still also undergo conventional testing, however, because that can identify eight additional viruses that the rapid test doesn’t cover.

Dr. Schuurmans acknowledged that further study needs to assess the cost-benefit of the rapid test to confirm that its added expense is offset by reduced expenses for empiric treatment and hospital isolation.

He had no disclosures. The study received no commercial support.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

TORONTO – A test that only requires a maximum 2-hour wait for results was highly accurate at detecting influenza and respiratory syncytial virus infection in lung transplant patients, according to research presented at the CHEST annual meeting on Oct. 30.

This rapid and highly accurate test for detecting three common respiratory viruses has dramatically cut the need for empiric treatments and the risk for causing nosocomial infections in lung transplant patients who develop severe upper respiratory infections, Macé M. Schuurmans, MD, noted during the presentation.

This study involved 100 consecutive lung transplant patients who presented at Zurich University Hospital with signs of severe upper respiratory infection. The researchers ran the rapid and standard diagnostic tests for each patient and found that, relative to the standard test, the rapid test had positive and negative predictive values of 95%.

The number of empiric treatments with oseltamivir (Tamiflu) and ribavirin to treat a suspected influenza or respiratory syncytial virus infection (RSV) has “strongly diminished” by about two-thirds, noted Dr. Schuurmans, who is a pulmonologist at the hospital.

Until the rapid test became available, Dr. Shuurmans and his associates used a standard polymerase chain reaction test that takes 36-48 hours to yield a result. Using this test made treating patients empirically with oseltamivir and oral antibiotics for a couple of days a necessity, he said in a video interview. The older test also required isolating patients to avoid the potential spread of influenza or RSV in the hospital.

The rapid test, which became available for U.S. use in early 2017, covers influenza A and B and RSV in a single test with a single mouth-swab specimen.

“We now routinely use the rapid test and don’t prescribe empiric antivirals or antibiotics as often,” Dr. Schuurmans said. “There is much less drug cost and fewer potential adverse effects from empiric treatment.” Specimens still also undergo conventional testing, however, because that can identify eight additional viruses that the rapid test doesn’t cover.

Dr. Schuurmans acknowledged that further study needs to assess the cost-benefit of the rapid test to confirm that its added expense is offset by reduced expenses for empiric treatment and hospital isolation.

He had no disclosures. The study received no commercial support.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT CHEST 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The rapid test had positive and negative predictive values of 95%.

Data source: A single-center observational study of 100 consecutive lung transplant recipients who presented with severe, acute respiratory infection.

Disclosures: Dr. Schuurmans had no disclosures. The study received no commercial support.

VIDEO: Liver transplant center competition tied to delisting patients

WASHINGTON – Low market competition among liver transplant centers may affect which patients are considered too sick to transplant, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

With 20% of patients dying while on the transplant wait list, including those who were delisted, understanding the distribution of organs among donor service areas (DSAs) is crucial to lowering mortality during the current organ shortage, according to presenter Yanik Babekov, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Investigators studied 3,131 patients who were delisted after being classified as “too sick” from 116 centers in 51 DSAs, between 2002 and 2012.

Researchers used the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), which analyzes the market share of each participant to determine the overall level of competition. Measurements on the HHI range between 0 and 1, with 0 being the most competitive and 1 being the least.

Mean delisting Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores considered to be “too sick to transplant” were 26.1, and average HHI among DSAs was 0.46, according to investigators. They found that, for every 1% increase in HHI, the delisting MELD score increased by 0.06, according to a risk-adjustment analysis.

“In other words, more competitive DSAs delist patients for [being] ‘too sick’ at lower MELD scores,” Dr. Babekov explained in a video interview. “Interestingly, race, education, citizenship, and other DSA factors also impacted delisting MELD for ‘too sick.’ ”

While market competition may not be the only factor to explain the phenomenon of patients delisted for being ‘too sick,’ it is important to identify how having more transplant centers in DSAs can help more patients be added to, and stay on, these wait lists, according to investigators.

Dr. Babekov had no relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

WASHINGTON – Low market competition among liver transplant centers may affect which patients are considered too sick to transplant, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

With 20% of patients dying while on the transplant wait list, including those who were delisted, understanding the distribution of organs among donor service areas (DSAs) is crucial to lowering mortality during the current organ shortage, according to presenter Yanik Babekov, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Investigators studied 3,131 patients who were delisted after being classified as “too sick” from 116 centers in 51 DSAs, between 2002 and 2012.

Researchers used the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), which analyzes the market share of each participant to determine the overall level of competition. Measurements on the HHI range between 0 and 1, with 0 being the most competitive and 1 being the least.

Mean delisting Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores considered to be “too sick to transplant” were 26.1, and average HHI among DSAs was 0.46, according to investigators. They found that, for every 1% increase in HHI, the delisting MELD score increased by 0.06, according to a risk-adjustment analysis.

“In other words, more competitive DSAs delist patients for [being] ‘too sick’ at lower MELD scores,” Dr. Babekov explained in a video interview. “Interestingly, race, education, citizenship, and other DSA factors also impacted delisting MELD for ‘too sick.’ ”

While market competition may not be the only factor to explain the phenomenon of patients delisted for being ‘too sick,’ it is important to identify how having more transplant centers in DSAs can help more patients be added to, and stay on, these wait lists, according to investigators.

Dr. Babekov had no relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

WASHINGTON – Low market competition among liver transplant centers may affect which patients are considered too sick to transplant, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

With 20% of patients dying while on the transplant wait list, including those who were delisted, understanding the distribution of organs among donor service areas (DSAs) is crucial to lowering mortality during the current organ shortage, according to presenter Yanik Babekov, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Investigators studied 3,131 patients who were delisted after being classified as “too sick” from 116 centers in 51 DSAs, between 2002 and 2012.

Researchers used the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), which analyzes the market share of each participant to determine the overall level of competition. Measurements on the HHI range between 0 and 1, with 0 being the most competitive and 1 being the least.

Mean delisting Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores considered to be “too sick to transplant” were 26.1, and average HHI among DSAs was 0.46, according to investigators. They found that, for every 1% increase in HHI, the delisting MELD score increased by 0.06, according to a risk-adjustment analysis.

“In other words, more competitive DSAs delist patients for [being] ‘too sick’ at lower MELD scores,” Dr. Babekov explained in a video interview. “Interestingly, race, education, citizenship, and other DSA factors also impacted delisting MELD for ‘too sick.’ ”

While market competition may not be the only factor to explain the phenomenon of patients delisted for being ‘too sick,’ it is important to identify how having more transplant centers in DSAs can help more patients be added to, and stay on, these wait lists, according to investigators.

Dr. Babekov had no relevant financial disclosures.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

AT THE LIVER MEETING 2017

Nutrition status predicts outcomes in liver transplant

WASHINGTON – Efforts to improve nutritional status prior to transplant may lead to improved patient outcomes and economic benefits after orthotopic liver transplant.

Clinicians at Austin Health, a tertiary health center in Melbourne, reviewed prospectively acquired data on 390 adult patients who underwent orthotopic liver transplant at their institution between January 2009 and June 2016, according to Brooke Chapman, a dietitian on the center’s transplant team.

“Hand-grip strength test is a functional measure of upper-body strength,” Ms. Chapman said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. “It’s quick and cheap and reliable but importantly, it does respond quite readily to changes in nutritional intake and nutrition status.”

Assessments were made as patients were wait listed for liver transplant. Hand-grip strength and subjective global assessment were repeated at the time of transplant.

Patients with fulminant liver failure and those requiring retransplantation were excluded from the final analysis, leaving 321 patients in the cohort. More than two-thirds (69%) were men and the median age was 52 years old. About half of patients had a diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma or hepatitis C infection. The median MELD (Model for Endstage Liver Disease) score was 18, with a range of 6-40, and the median time on the wait list was 140 days.

We saw a “high prevalence of malnutrition in patients undergoing liver transplant and the deterioration in nutritional status despite our best efforts while they are on the waiting list,” Ms. Chapman said.

At baseline, two-thirds of patients were malnourished – either mildly to moderately or severely; by transplantation, 77% were malnourished.

“At assessment, we are prescribing and educating patients on a high-calorie, high-protein diet initially, and we give oral nutrition support therapies,” she said. “We really try to get them to improve oral intake, but for patients who do require more aggressive intervention, we will feed them via nasogastric tube.”

Just over half (55%) of patients fell below the cutoff for sarcopenia on the hand-grip test at baseline and at transplant. More than a quarter of patients (27%) were not able to complete the 6-minute walk test.

“On univariate analysis, we saw malnutrition to be strongly associated with increased ICU and hospital length of stay,” Ms. Chapman noted. Severely malnourished patients spent significantly more time in the ICU than did well-nourished patients – a mean 147 hours vs. 89 hours (P = .001). Mean length of stay also was significantly longer at 40 days vs. 16 days (P = .003).

There was also an increased incidence of infection in severely malnourished patients as compared with well-nourished patients – 55.2% vs. 33.8%, she said.

“Aggressive strategies to combat malnutrition and deconditioning in the pretransplant period may lead to improved outcomes after transplant,” Ms. Chapman concluded.

The study was funded by Austin Health. Ms. Chapman declared no relevant conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @denisefulton

WASHINGTON – Efforts to improve nutritional status prior to transplant may lead to improved patient outcomes and economic benefits after orthotopic liver transplant.

Clinicians at Austin Health, a tertiary health center in Melbourne, reviewed prospectively acquired data on 390 adult patients who underwent orthotopic liver transplant at their institution between January 2009 and June 2016, according to Brooke Chapman, a dietitian on the center’s transplant team.

“Hand-grip strength test is a functional measure of upper-body strength,” Ms. Chapman said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. “It’s quick and cheap and reliable but importantly, it does respond quite readily to changes in nutritional intake and nutrition status.”

Assessments were made as patients were wait listed for liver transplant. Hand-grip strength and subjective global assessment were repeated at the time of transplant.

Patients with fulminant liver failure and those requiring retransplantation were excluded from the final analysis, leaving 321 patients in the cohort. More than two-thirds (69%) were men and the median age was 52 years old. About half of patients had a diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma or hepatitis C infection. The median MELD (Model for Endstage Liver Disease) score was 18, with a range of 6-40, and the median time on the wait list was 140 days.

We saw a “high prevalence of malnutrition in patients undergoing liver transplant and the deterioration in nutritional status despite our best efforts while they are on the waiting list,” Ms. Chapman said.

At baseline, two-thirds of patients were malnourished – either mildly to moderately or severely; by transplantation, 77% were malnourished.

“At assessment, we are prescribing and educating patients on a high-calorie, high-protein diet initially, and we give oral nutrition support therapies,” she said. “We really try to get them to improve oral intake, but for patients who do require more aggressive intervention, we will feed them via nasogastric tube.”

Just over half (55%) of patients fell below the cutoff for sarcopenia on the hand-grip test at baseline and at transplant. More than a quarter of patients (27%) were not able to complete the 6-minute walk test.

“On univariate analysis, we saw malnutrition to be strongly associated with increased ICU and hospital length of stay,” Ms. Chapman noted. Severely malnourished patients spent significantly more time in the ICU than did well-nourished patients – a mean 147 hours vs. 89 hours (P = .001). Mean length of stay also was significantly longer at 40 days vs. 16 days (P = .003).

There was also an increased incidence of infection in severely malnourished patients as compared with well-nourished patients – 55.2% vs. 33.8%, she said.

“Aggressive strategies to combat malnutrition and deconditioning in the pretransplant period may lead to improved outcomes after transplant,” Ms. Chapman concluded.

The study was funded by Austin Health. Ms. Chapman declared no relevant conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @denisefulton

WASHINGTON – Efforts to improve nutritional status prior to transplant may lead to improved patient outcomes and economic benefits after orthotopic liver transplant.

Clinicians at Austin Health, a tertiary health center in Melbourne, reviewed prospectively acquired data on 390 adult patients who underwent orthotopic liver transplant at their institution between January 2009 and June 2016, according to Brooke Chapman, a dietitian on the center’s transplant team.

“Hand-grip strength test is a functional measure of upper-body strength,” Ms. Chapman said at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. “It’s quick and cheap and reliable but importantly, it does respond quite readily to changes in nutritional intake and nutrition status.”

Assessments were made as patients were wait listed for liver transplant. Hand-grip strength and subjective global assessment were repeated at the time of transplant.

Patients with fulminant liver failure and those requiring retransplantation were excluded from the final analysis, leaving 321 patients in the cohort. More than two-thirds (69%) were men and the median age was 52 years old. About half of patients had a diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma or hepatitis C infection. The median MELD (Model for Endstage Liver Disease) score was 18, with a range of 6-40, and the median time on the wait list was 140 days.

We saw a “high prevalence of malnutrition in patients undergoing liver transplant and the deterioration in nutritional status despite our best efforts while they are on the waiting list,” Ms. Chapman said.

At baseline, two-thirds of patients were malnourished – either mildly to moderately or severely; by transplantation, 77% were malnourished.

“At assessment, we are prescribing and educating patients on a high-calorie, high-protein diet initially, and we give oral nutrition support therapies,” she said. “We really try to get them to improve oral intake, but for patients who do require more aggressive intervention, we will feed them via nasogastric tube.”

Just over half (55%) of patients fell below the cutoff for sarcopenia on the hand-grip test at baseline and at transplant. More than a quarter of patients (27%) were not able to complete the 6-minute walk test.

“On univariate analysis, we saw malnutrition to be strongly associated with increased ICU and hospital length of stay,” Ms. Chapman noted. Severely malnourished patients spent significantly more time in the ICU than did well-nourished patients – a mean 147 hours vs. 89 hours (P = .001). Mean length of stay also was significantly longer at 40 days vs. 16 days (P = .003).

There was also an increased incidence of infection in severely malnourished patients as compared with well-nourished patients – 55.2% vs. 33.8%, she said.

“Aggressive strategies to combat malnutrition and deconditioning in the pretransplant period may lead to improved outcomes after transplant,” Ms. Chapman concluded.

The study was funded by Austin Health. Ms. Chapman declared no relevant conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @denisefulton

AT THE LIVER MEETING 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Severely malnourished patients spent a mean of 147 hours in the ICU vs. 89 hours for well-nourished patients. Mean length of stay also was significantly longer at 40 days vs. 16 days (P = .003).

Data source: Retrospective review of data on 390 adults awaiting liver transplantation between Jan. 2009 and June 2016.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the institutions. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Post–liver transplant results similar in acute alcoholic hepatitis, stage 1a

WASHINGTON – Patients with acute alcoholic hepatitis (AAH) have similar early post–liver transplant outcomes to those listed with fulminant hepatic failure, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Patients with severe AAH have high mortality, but many are unable to survive the 6 months of sobriety required to be accepted as liver transplant candidates, said George Cholankeril, MD, of the gastroenterology and hepatology department at Stanford (Calif.) University.

He and his associates studied wait-list mortality and post–liver transplant survival among 1,912 patients listed for either AAH or fulminant hepatic failure on the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) registry between 2011 and 2016.

A total of 193 patients were listed with AAH, 314 were listed with drug-induced liver injury including acetaminophen (DILI-APAP), and 1,405 were listed as non-DILI patients.

One-year post–liver transplant survival among AAH patients was 93.3%, compared with 87.75% for DILI-APAP patients and 88.4% among non-DILI patients (P less than .001). Survival remained the same among AAH patients 3 years following transplantation, but rates dropped for both the DILI-APAP group (80.8%) and the non-DILI group (81.4%), Dr. Cholankeril reported.

Patients were a median age of 45, 33, and 46 years among the AAH, DILI-APAP, and non-DILI, groups respectively. Patients were majority white among all three groups, with a significantly larger female population among the DILI-APAP group (80.6%) than the AAH (34.7%) or non-DILI (59.4%) groups. Patients in the AAH group had a median Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score of 32, compared with 34 for DILI-APAP and 21 for non-DILI.

AAH patients could potentially see significant improvement with a liver transplant, according to investigators; however, the current standards for candidacy have created treatment barriers.

“Patients with AAH have comparable early post-transplant outcomes to those with hepatic liver failure,” said Dr. Cholankeril. “However, there is no consensus or national guidelines for liver transplantation within this patient population.”

Wait-list trends have already started to shift toward more AAH patient acceptance. The number of AAH patients added to the transplant wait lists increased from 14 in 2011 to 58 in 2016. Investigators also found that the number of liver transplant centers accepting AAH patients to their transplant lists increased from 3 to 26.

Investigators were limited by the variations in protocols for each transplant center, as well as by the inconsistency of pre–liver transplant psychosocial metrics. The diagnostic criteria of AAH through UNOS was also a limitation for investigators, according to Dr. Cholankeril.

Although liver transplantation may be able to help some patients, it is only a small fix for a much larger problem. “This is only a solution for a minority of patients with the rising epidemic of alcoholic intoxication in the U.S.,” he said. “As the increasing mortality trends show alcohol-related mortality, and alcoholic liver disease is a contributor to it, we must recognize alcoholic liver disease remains an orphan disease and there is still an unmet need.”

Dr. Cholankeril reported no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

Transplanting patients with alcohol induced liver disease has been controversial since the earliest days of liver transplantation. Initially some programs were reluctant to transplant patients with a disease that was “self-inflicted” based on an ethical concern about using a scarce resource to save the lives of those whose disease was their own fault, while other patients may die waiting. There was also a concern that transplanting alcoholics would be bad publicity for organ donation and reduce the public’s willingness to donate organs. The highly publicized transplantation of baseball legend and known alcoholic Mickey Mantle in 1995 intensified this debate.

Over time it became clear that the concerns regarding transplanting alcoholics were unfounded. The outcomes were equal or better than for other diseases. Liver transplantation was termed “the ultimate eye opening experience” as serious recidivism turned out to be very uncommon. It was realized that a large percentage of all reasons for seeking medical care can be attributed to self-inflicted harm when one considers cigarette induced malignancy and cardiovascular disease and dietary indiscretion leading to obesity and diabetes. It also became clear that from a practical standpoint prohibiting transplantation of alcoholics simply drove patients to programs that would accept such patients, or caused them and their family to withhold disclosure of alcohol use.

While transplantation of patients with chronic liver disease due to alcohol use has become standard of care, transplanting patients with acute alcoholic hepatitis remains controversial and relatively uncommon. Many programs require a period of abstinence, which is impossible in the setting of acute alcoholic hepatitis. The concern is that it is impossible to discern among actively drinking candidates which ones will be able to achieve sobriety after the transplant. The report by Cholankeril and colleagues documents that the tide is changing. There are increasing numbers of patients being transplanted for acute alcoholic hepatitis, and outcomes are acceptable. However, as the authors point out, the numbers are small and represent a highly selected group of patients. Nevertheless, the pressure on programs to modify rigid abstinence criteria is likely to grow as the evidence accumulates showing selected patients with acute alcoholic hepatitis can do well.

Jeffrey Punch, MD, FACS, is transplant specialist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and on the Editorial Advisory Board of ACS Surgery News.

Transplanting patients with alcohol induced liver disease has been controversial since the earliest days of liver transplantation. Initially some programs were reluctant to transplant patients with a disease that was “self-inflicted” based on an ethical concern about using a scarce resource to save the lives of those whose disease was their own fault, while other patients may die waiting. There was also a concern that transplanting alcoholics would be bad publicity for organ donation and reduce the public’s willingness to donate organs. The highly publicized transplantation of baseball legend and known alcoholic Mickey Mantle in 1995 intensified this debate.

Over time it became clear that the concerns regarding transplanting alcoholics were unfounded. The outcomes were equal or better than for other diseases. Liver transplantation was termed “the ultimate eye opening experience” as serious recidivism turned out to be very uncommon. It was realized that a large percentage of all reasons for seeking medical care can be attributed to self-inflicted harm when one considers cigarette induced malignancy and cardiovascular disease and dietary indiscretion leading to obesity and diabetes. It also became clear that from a practical standpoint prohibiting transplantation of alcoholics simply drove patients to programs that would accept such patients, or caused them and their family to withhold disclosure of alcohol use.

While transplantation of patients with chronic liver disease due to alcohol use has become standard of care, transplanting patients with acute alcoholic hepatitis remains controversial and relatively uncommon. Many programs require a period of abstinence, which is impossible in the setting of acute alcoholic hepatitis. The concern is that it is impossible to discern among actively drinking candidates which ones will be able to achieve sobriety after the transplant. The report by Cholankeril and colleagues documents that the tide is changing. There are increasing numbers of patients being transplanted for acute alcoholic hepatitis, and outcomes are acceptable. However, as the authors point out, the numbers are small and represent a highly selected group of patients. Nevertheless, the pressure on programs to modify rigid abstinence criteria is likely to grow as the evidence accumulates showing selected patients with acute alcoholic hepatitis can do well.

Jeffrey Punch, MD, FACS, is transplant specialist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and on the Editorial Advisory Board of ACS Surgery News.

Transplanting patients with alcohol induced liver disease has been controversial since the earliest days of liver transplantation. Initially some programs were reluctant to transplant patients with a disease that was “self-inflicted” based on an ethical concern about using a scarce resource to save the lives of those whose disease was their own fault, while other patients may die waiting. There was also a concern that transplanting alcoholics would be bad publicity for organ donation and reduce the public’s willingness to donate organs. The highly publicized transplantation of baseball legend and known alcoholic Mickey Mantle in 1995 intensified this debate.

Over time it became clear that the concerns regarding transplanting alcoholics were unfounded. The outcomes were equal or better than for other diseases. Liver transplantation was termed “the ultimate eye opening experience” as serious recidivism turned out to be very uncommon. It was realized that a large percentage of all reasons for seeking medical care can be attributed to self-inflicted harm when one considers cigarette induced malignancy and cardiovascular disease and dietary indiscretion leading to obesity and diabetes. It also became clear that from a practical standpoint prohibiting transplantation of alcoholics simply drove patients to programs that would accept such patients, or caused them and their family to withhold disclosure of alcohol use.

While transplantation of patients with chronic liver disease due to alcohol use has become standard of care, transplanting patients with acute alcoholic hepatitis remains controversial and relatively uncommon. Many programs require a period of abstinence, which is impossible in the setting of acute alcoholic hepatitis. The concern is that it is impossible to discern among actively drinking candidates which ones will be able to achieve sobriety after the transplant. The report by Cholankeril and colleagues documents that the tide is changing. There are increasing numbers of patients being transplanted for acute alcoholic hepatitis, and outcomes are acceptable. However, as the authors point out, the numbers are small and represent a highly selected group of patients. Nevertheless, the pressure on programs to modify rigid abstinence criteria is likely to grow as the evidence accumulates showing selected patients with acute alcoholic hepatitis can do well.

Jeffrey Punch, MD, FACS, is transplant specialist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and on the Editorial Advisory Board of ACS Surgery News.

WASHINGTON – Patients with acute alcoholic hepatitis (AAH) have similar early post–liver transplant outcomes to those listed with fulminant hepatic failure, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Patients with severe AAH have high mortality, but many are unable to survive the 6 months of sobriety required to be accepted as liver transplant candidates, said George Cholankeril, MD, of the gastroenterology and hepatology department at Stanford (Calif.) University.

He and his associates studied wait-list mortality and post–liver transplant survival among 1,912 patients listed for either AAH or fulminant hepatic failure on the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) registry between 2011 and 2016.

A total of 193 patients were listed with AAH, 314 were listed with drug-induced liver injury including acetaminophen (DILI-APAP), and 1,405 were listed as non-DILI patients.

One-year post–liver transplant survival among AAH patients was 93.3%, compared with 87.75% for DILI-APAP patients and 88.4% among non-DILI patients (P less than .001). Survival remained the same among AAH patients 3 years following transplantation, but rates dropped for both the DILI-APAP group (80.8%) and the non-DILI group (81.4%), Dr. Cholankeril reported.

Patients were a median age of 45, 33, and 46 years among the AAH, DILI-APAP, and non-DILI, groups respectively. Patients were majority white among all three groups, with a significantly larger female population among the DILI-APAP group (80.6%) than the AAH (34.7%) or non-DILI (59.4%) groups. Patients in the AAH group had a median Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score of 32, compared with 34 for DILI-APAP and 21 for non-DILI.

AAH patients could potentially see significant improvement with a liver transplant, according to investigators; however, the current standards for candidacy have created treatment barriers.

“Patients with AAH have comparable early post-transplant outcomes to those with hepatic liver failure,” said Dr. Cholankeril. “However, there is no consensus or national guidelines for liver transplantation within this patient population.”

Wait-list trends have already started to shift toward more AAH patient acceptance. The number of AAH patients added to the transplant wait lists increased from 14 in 2011 to 58 in 2016. Investigators also found that the number of liver transplant centers accepting AAH patients to their transplant lists increased from 3 to 26.

Investigators were limited by the variations in protocols for each transplant center, as well as by the inconsistency of pre–liver transplant psychosocial metrics. The diagnostic criteria of AAH through UNOS was also a limitation for investigators, according to Dr. Cholankeril.

Although liver transplantation may be able to help some patients, it is only a small fix for a much larger problem. “This is only a solution for a minority of patients with the rising epidemic of alcoholic intoxication in the U.S.,” he said. “As the increasing mortality trends show alcohol-related mortality, and alcoholic liver disease is a contributor to it, we must recognize alcoholic liver disease remains an orphan disease and there is still an unmet need.”

Dr. Cholankeril reported no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

WASHINGTON – Patients with acute alcoholic hepatitis (AAH) have similar early post–liver transplant outcomes to those listed with fulminant hepatic failure, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Patients with severe AAH have high mortality, but many are unable to survive the 6 months of sobriety required to be accepted as liver transplant candidates, said George Cholankeril, MD, of the gastroenterology and hepatology department at Stanford (Calif.) University.

He and his associates studied wait-list mortality and post–liver transplant survival among 1,912 patients listed for either AAH or fulminant hepatic failure on the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) registry between 2011 and 2016.

A total of 193 patients were listed with AAH, 314 were listed with drug-induced liver injury including acetaminophen (DILI-APAP), and 1,405 were listed as non-DILI patients.

One-year post–liver transplant survival among AAH patients was 93.3%, compared with 87.75% for DILI-APAP patients and 88.4% among non-DILI patients (P less than .001). Survival remained the same among AAH patients 3 years following transplantation, but rates dropped for both the DILI-APAP group (80.8%) and the non-DILI group (81.4%), Dr. Cholankeril reported.

Patients were a median age of 45, 33, and 46 years among the AAH, DILI-APAP, and non-DILI, groups respectively. Patients were majority white among all three groups, with a significantly larger female population among the DILI-APAP group (80.6%) than the AAH (34.7%) or non-DILI (59.4%) groups. Patients in the AAH group had a median Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score of 32, compared with 34 for DILI-APAP and 21 for non-DILI.

AAH patients could potentially see significant improvement with a liver transplant, according to investigators; however, the current standards for candidacy have created treatment barriers.

“Patients with AAH have comparable early post-transplant outcomes to those with hepatic liver failure,” said Dr. Cholankeril. “However, there is no consensus or national guidelines for liver transplantation within this patient population.”

Wait-list trends have already started to shift toward more AAH patient acceptance. The number of AAH patients added to the transplant wait lists increased from 14 in 2011 to 58 in 2016. Investigators also found that the number of liver transplant centers accepting AAH patients to their transplant lists increased from 3 to 26.

Investigators were limited by the variations in protocols for each transplant center, as well as by the inconsistency of pre–liver transplant psychosocial metrics. The diagnostic criteria of AAH through UNOS was also a limitation for investigators, according to Dr. Cholankeril.

Although liver transplantation may be able to help some patients, it is only a small fix for a much larger problem. “This is only a solution for a minority of patients with the rising epidemic of alcoholic intoxication in the U.S.,” he said. “As the increasing mortality trends show alcohol-related mortality, and alcoholic liver disease is a contributor to it, we must recognize alcoholic liver disease remains an orphan disease and there is still an unmet need.”

Dr. Cholankeril reported no relevant financial disclosures.

[email protected]

On Twitter @eaztweets

AT THE LIVER MEETING 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Survival 1 and 3 years after liver transplant was comparable in patients with drug-induced liver injury including acetaminophen (P = .10) and significantly higher than other chronic alcoholic liver disease patients (P less that .001).

Data source: Retrospective study of 1,912 liver transplant patients listed for either AAH or status 1A registered on the UNOS registry between 2011 and 2016.

Disclosures: Presenter reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Early liver transplant good for patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis

Early liver transplantation was associated with good short-term survival in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis, but a significant number of patients started consuming alcohol again, according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

The study was a retrospective review of the ACCELERATE-AH trial, utilizing a cohort of 147 patients with severe AH who underwent liver transplant prior to a 6-month abstinence period and were discharged home after surgery, said Dr. Brian Lee of the University of California, San Francisco, and his colleagues. Patients also underwent a follow-up period with a median time of 1.6 years.

Pretransplant abstinence time was a median of 55 days, and 54% received steroids for alcoholic hepatitis before the surgery. A total of 141 patients were discharged home after surgery, and 132 survived past 3 months. Of the nine patients who died within 3 months of their liver transplant, eight had received steroid therapy, and five died from sepsis.

No deaths were reported between 3 months and 1 year post transplant, but nine deaths were reported after 1 year, seven of which were alcohol related. The probability of alcohol use after 1 year was 25% and was 34% after 3 years.

After adjustment, a lack of self-admission into a hospital was associated with alcohol usage post transplant, with a hazard ratio of 4.3. In multivariate analysis, any alcohol use post transplant was associated with death, with a hazard ratio of 3.9, Dr. Lee and his colleagues noted.