User login

Antibody shows promise in eosinophilic gastritis/duodenitis

In a phase 2 trial in eosinophilic gastritis and duodenitis, an anti–Siglec-8 antibody greatly reduced populations of eosinophilic cells, and also led to improved symptoms. The sponsoring company, Alkalos, is currently conducting a phase 3 trial in eosinophilic gastritis or duodenitis and a phase 2-3 trial in eosinophilic esophagitis.

The news is welcome to clinicians who treat these rare conditions, since the only current treatment option is steroids. This is particularly challenging because most patients with these conditions present in their 30s and 40s, according to Carol Semrad, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, who was asked to comment on the study. She noted that the study’s results were impressive, but it will take a phase 3 trial to convince. It’s also unclear if the clinical benefit tracks with the impressive reduction seen in eosinophil count. “There’s somewhat of a disconnect between symptom reduction and reduction of the eosinophil counts. Sometimes just blocking the inflammation [isn’t enough]. Maybe there is other damage to the bowel.”

Still, “it looks like they have a proof of concept that it’s very effective at blocking the eosinophils and mast cells that are thought to be causing eosinophilic gastritis and duodenitis in human disease. That, along with improvement in symptoms, is highly promising, given that we have no other treatment beside steroids,” said Dr. Semrad.

The research, led by Evan S. Dellon, MD, MPH, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Ikuo Hirano, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The antibody (lirentelimab) targets sialic acid–binding immunoglobulin-like lectin 8 (Siglec-8), which is an inhibitory receptor found on mature eosinophils and mast cells, and expressed at low levels on basophils. The antibody reduces eosinophil population through natural killer cell-mediated cellular cytotoxicity and apoptosis, and other antibodies against the same target have been shown to inhibit activation of mast cells.

At 22 sites across the United States, researchers randomized 65 adults with active, uncontrolled eosinophilic gastritis or eosinophilic duodenitis, or both, to receive four monthly low doses (0.3, 1, 1, and 1 mg/kg) or high-dose lirentelimab (0.3, 1, 3, and 3 mg/kg), or placebo. A total of 10 patients had gastritis, 25 had duodenitis, and 30 had both.

In the intention-to-treat analysis, there was a mean 86% reduction in eosinophil count in patients in the treatment groups, compared with a 9% increase in controls (P < .001). In the per-protocol analysis, there was a 95% reduction versus a 10% increase (P < .001). Of treated patients, 95% had a gastrointestinal eosinophil count of 6 or fewer per high-powered field, compared with 0% in the placebo group.

In the intention-to-treat analysis, 63% of treated patients experienced a treatment response, defined as at least a 30% reduction in total symptom score and at least a 75% reduction in eosinophil count. About 5% of patients had a response in the placebo group (P < .001). The mean percentage change in total symptom score was –48 versus –22 in the placebo group (P = .004). In the per-protocol analysis, 69% responded versus 5% (P < .001). The mean percentage change in total symptom score was –53 versus –24 (P = .001).

91% of patients in the treatment groups experienced at least one adverse event, compared with 82% in the placebo group. About 60% in the treatment group had an infusion-related reaction versus 23% who received placebo; 93% of reactions were mild to moderate. Serious adverse events occurred in 9% of the treatment group and 14% of patients on placebo. The only serious adverse event thought to be related to the drug was a single grade 4 infusion-related event in the high-dose treatment group, which led to discontinuation of the drug and withdrawal from the trial. 86% of patients in the treatment group experienced transient lymphopenia, as did 47% of the placebo group, but there were no clinical consequences.

One potential concern with the therapy is the effect that long-term suppression of eosinophils and mast cells, and to a lesser extent basophils, could have on the immune system. Eosinophils are key to defenses against parasites, so that will need to be looked at in further studies, according to Dr. Semrad: “How is blocking those inflammatory cells going to impact gut function and the ability to fight off certain organisms? That’s going to be one of the real questions.”

The study was funded by Alkalos. Dr. Semrad has no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Dellon ES et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Oct 22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2012047.

In a phase 2 trial in eosinophilic gastritis and duodenitis, an anti–Siglec-8 antibody greatly reduced populations of eosinophilic cells, and also led to improved symptoms. The sponsoring company, Alkalos, is currently conducting a phase 3 trial in eosinophilic gastritis or duodenitis and a phase 2-3 trial in eosinophilic esophagitis.

The news is welcome to clinicians who treat these rare conditions, since the only current treatment option is steroids. This is particularly challenging because most patients with these conditions present in their 30s and 40s, according to Carol Semrad, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, who was asked to comment on the study. She noted that the study’s results were impressive, but it will take a phase 3 trial to convince. It’s also unclear if the clinical benefit tracks with the impressive reduction seen in eosinophil count. “There’s somewhat of a disconnect between symptom reduction and reduction of the eosinophil counts. Sometimes just blocking the inflammation [isn’t enough]. Maybe there is other damage to the bowel.”

Still, “it looks like they have a proof of concept that it’s very effective at blocking the eosinophils and mast cells that are thought to be causing eosinophilic gastritis and duodenitis in human disease. That, along with improvement in symptoms, is highly promising, given that we have no other treatment beside steroids,” said Dr. Semrad.

The research, led by Evan S. Dellon, MD, MPH, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Ikuo Hirano, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The antibody (lirentelimab) targets sialic acid–binding immunoglobulin-like lectin 8 (Siglec-8), which is an inhibitory receptor found on mature eosinophils and mast cells, and expressed at low levels on basophils. The antibody reduces eosinophil population through natural killer cell-mediated cellular cytotoxicity and apoptosis, and other antibodies against the same target have been shown to inhibit activation of mast cells.

At 22 sites across the United States, researchers randomized 65 adults with active, uncontrolled eosinophilic gastritis or eosinophilic duodenitis, or both, to receive four monthly low doses (0.3, 1, 1, and 1 mg/kg) or high-dose lirentelimab (0.3, 1, 3, and 3 mg/kg), or placebo. A total of 10 patients had gastritis, 25 had duodenitis, and 30 had both.

In the intention-to-treat analysis, there was a mean 86% reduction in eosinophil count in patients in the treatment groups, compared with a 9% increase in controls (P < .001). In the per-protocol analysis, there was a 95% reduction versus a 10% increase (P < .001). Of treated patients, 95% had a gastrointestinal eosinophil count of 6 or fewer per high-powered field, compared with 0% in the placebo group.

In the intention-to-treat analysis, 63% of treated patients experienced a treatment response, defined as at least a 30% reduction in total symptom score and at least a 75% reduction in eosinophil count. About 5% of patients had a response in the placebo group (P < .001). The mean percentage change in total symptom score was –48 versus –22 in the placebo group (P = .004). In the per-protocol analysis, 69% responded versus 5% (P < .001). The mean percentage change in total symptom score was –53 versus –24 (P = .001).

91% of patients in the treatment groups experienced at least one adverse event, compared with 82% in the placebo group. About 60% in the treatment group had an infusion-related reaction versus 23% who received placebo; 93% of reactions were mild to moderate. Serious adverse events occurred in 9% of the treatment group and 14% of patients on placebo. The only serious adverse event thought to be related to the drug was a single grade 4 infusion-related event in the high-dose treatment group, which led to discontinuation of the drug and withdrawal from the trial. 86% of patients in the treatment group experienced transient lymphopenia, as did 47% of the placebo group, but there were no clinical consequences.

One potential concern with the therapy is the effect that long-term suppression of eosinophils and mast cells, and to a lesser extent basophils, could have on the immune system. Eosinophils are key to defenses against parasites, so that will need to be looked at in further studies, according to Dr. Semrad: “How is blocking those inflammatory cells going to impact gut function and the ability to fight off certain organisms? That’s going to be one of the real questions.”

The study was funded by Alkalos. Dr. Semrad has no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Dellon ES et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Oct 22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2012047.

In a phase 2 trial in eosinophilic gastritis and duodenitis, an anti–Siglec-8 antibody greatly reduced populations of eosinophilic cells, and also led to improved symptoms. The sponsoring company, Alkalos, is currently conducting a phase 3 trial in eosinophilic gastritis or duodenitis and a phase 2-3 trial in eosinophilic esophagitis.

The news is welcome to clinicians who treat these rare conditions, since the only current treatment option is steroids. This is particularly challenging because most patients with these conditions present in their 30s and 40s, according to Carol Semrad, MD, professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, who was asked to comment on the study. She noted that the study’s results were impressive, but it will take a phase 3 trial to convince. It’s also unclear if the clinical benefit tracks with the impressive reduction seen in eosinophil count. “There’s somewhat of a disconnect between symptom reduction and reduction of the eosinophil counts. Sometimes just blocking the inflammation [isn’t enough]. Maybe there is other damage to the bowel.”

Still, “it looks like they have a proof of concept that it’s very effective at blocking the eosinophils and mast cells that are thought to be causing eosinophilic gastritis and duodenitis in human disease. That, along with improvement in symptoms, is highly promising, given that we have no other treatment beside steroids,” said Dr. Semrad.

The research, led by Evan S. Dellon, MD, MPH, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Ikuo Hirano, MD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The antibody (lirentelimab) targets sialic acid–binding immunoglobulin-like lectin 8 (Siglec-8), which is an inhibitory receptor found on mature eosinophils and mast cells, and expressed at low levels on basophils. The antibody reduces eosinophil population through natural killer cell-mediated cellular cytotoxicity and apoptosis, and other antibodies against the same target have been shown to inhibit activation of mast cells.

At 22 sites across the United States, researchers randomized 65 adults with active, uncontrolled eosinophilic gastritis or eosinophilic duodenitis, or both, to receive four monthly low doses (0.3, 1, 1, and 1 mg/kg) or high-dose lirentelimab (0.3, 1, 3, and 3 mg/kg), or placebo. A total of 10 patients had gastritis, 25 had duodenitis, and 30 had both.

In the intention-to-treat analysis, there was a mean 86% reduction in eosinophil count in patients in the treatment groups, compared with a 9% increase in controls (P < .001). In the per-protocol analysis, there was a 95% reduction versus a 10% increase (P < .001). Of treated patients, 95% had a gastrointestinal eosinophil count of 6 or fewer per high-powered field, compared with 0% in the placebo group.

In the intention-to-treat analysis, 63% of treated patients experienced a treatment response, defined as at least a 30% reduction in total symptom score and at least a 75% reduction in eosinophil count. About 5% of patients had a response in the placebo group (P < .001). The mean percentage change in total symptom score was –48 versus –22 in the placebo group (P = .004). In the per-protocol analysis, 69% responded versus 5% (P < .001). The mean percentage change in total symptom score was –53 versus –24 (P = .001).

91% of patients in the treatment groups experienced at least one adverse event, compared with 82% in the placebo group. About 60% in the treatment group had an infusion-related reaction versus 23% who received placebo; 93% of reactions were mild to moderate. Serious adverse events occurred in 9% of the treatment group and 14% of patients on placebo. The only serious adverse event thought to be related to the drug was a single grade 4 infusion-related event in the high-dose treatment group, which led to discontinuation of the drug and withdrawal from the trial. 86% of patients in the treatment group experienced transient lymphopenia, as did 47% of the placebo group, but there were no clinical consequences.

One potential concern with the therapy is the effect that long-term suppression of eosinophils and mast cells, and to a lesser extent basophils, could have on the immune system. Eosinophils are key to defenses against parasites, so that will need to be looked at in further studies, according to Dr. Semrad: “How is blocking those inflammatory cells going to impact gut function and the ability to fight off certain organisms? That’s going to be one of the real questions.”

The study was funded by Alkalos. Dr. Semrad has no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Dellon ES et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Oct 22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2012047.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Budesonide orodispersible tablets maintained remissions in EoE

Budesonide orodispersible tablets maintained remissions of eosinophilic esophagitis for 48 weeks in approximately 75% of patients and did not increase the risk for most adverse events, compared with placebo, according to the findings of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial.

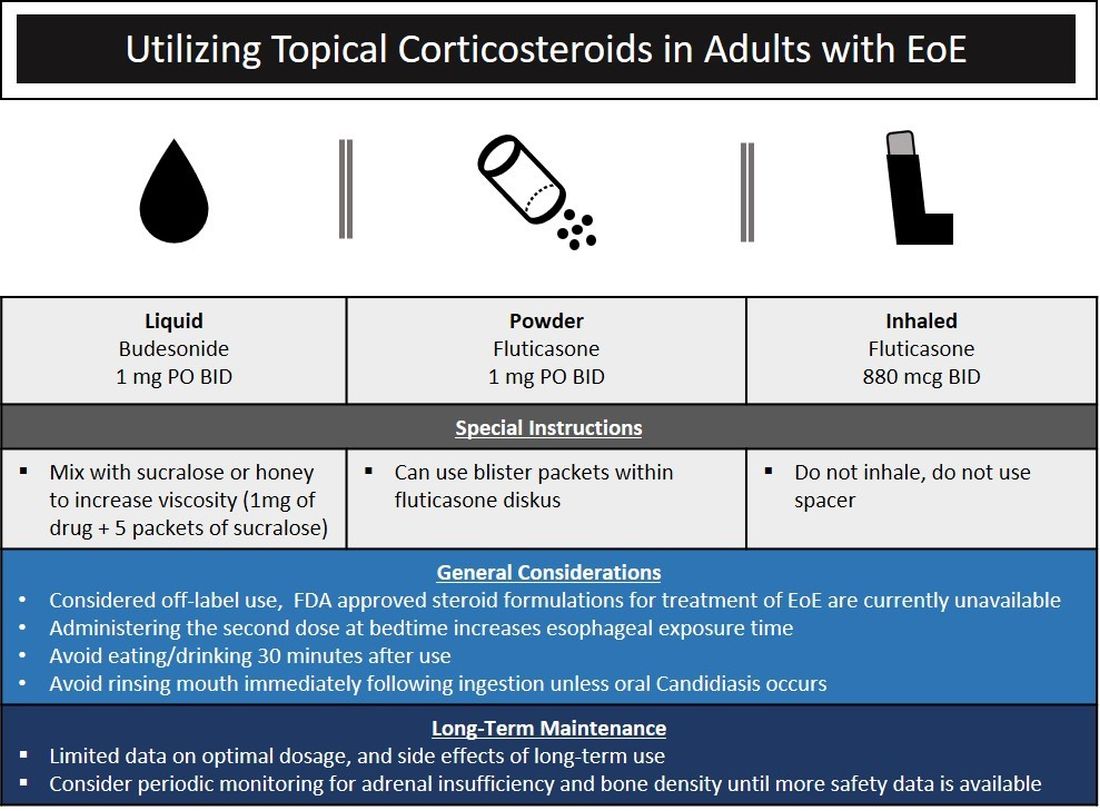

While prior studies have shown that swallowed topical corticosteroids such as budesonide or fluticasone induce remission in EoE, this is the first multicenter phase 3 study of budesonide orodispersible tablets (BOTs) for maintaining remissions over the long term, wrote Alex Straumann, MD, of the Swiss EoE Research Group and University Hospital Zurich, and associates in Gastroenterology.

Eosinophilic esophagitis is the most common cause of esophageal dysphagia and food impaction. Swallowed topical corticosteroids improve symptoms and inflammation, but the off-label use of formulations developed for airway administration in asthma shows “suboptimal esophageal targeting and efficacy,” the researchers wrote. In the phase 3 EOS-2 trial, twice-daily treatment with 1.0 mg BOTs had induced clinicohistologic remissions in 58% of adults with EoE at 6 weeks and in 85% at 12 weeks.

To study long-term maintenance BOT therapy, the researchers randomly assigned 204 of the remitted patients to 48 weeks of twice-daily BOT 0.5 mg, BOT 1.0 mg, or placebo. There were 68 patients per group. A total of 141 patients completed this double-blind phase, but all 204 were evaluable for the primary analysis. The primary outcome was remission at week 48, defined as freedom from relapse (dysphagia or odynophagia rated as 4 or higher on a 10-point numeric rating scale), histologic relapse (≥48 eosinophils per mm2 high-power field), food impaction requiring endoscopic intervention, and dilation.

After 48 weeks, 51 patients in the 1-mg group (75%) and 50 patients in the 0.5-mg group (73.5%) remained in remission, compared with only three patients in the placebo group (4.4%; both P less than .0001). Patients in the placebo group relapsed after a median of 87 days off BOTs. Overall, BOT therapy was similarly efficacious regardless of factors such as history of allergic diseases, location of inflammation at the start of induction, or concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors. However, patients with inflammation of all three esophageal segments achieved “clinically relevant” greater rates of remission with twice-daily 1.0-mg BOT, compared with twice-daily 0.5-mg BOT (80% vs. 68%). In secondary analyses, rates of histologic relapse were 13.2% with 0.5-mg BOT twice daily, 10.3% with 1.0-mg BOT twice daily, and 90% with placebo, and rates of clinical relapse were 10.3%, 7.4%, and 60.3%, respectively. “Histological remission in the BOT 0.5 and 1.0mg twice daily group was independently maintained in all esophageal segments,” the researchers reported.

Rates of most adverse events were similar across treatment groups, and no serious treatment-emergent adverse events were reported. Average morning serum cortisol levels were similar among groups and did not change after treatment ended, but four patients on BOT therapy developed asymptomatic subnormal levels of morning cortisol. “Clinically manifested candidiasis was suspected in 16.2% of patients in the BOT 0.5mg group and in 11.8% of patients in the BOT 1.0mg group; all infections resolved with treatment,” the researchers wrote.

The study and editorial support were funded by Dr. Falk Pharma GmbH, a pharmaceutical company in Germany. Dr. Falk Pharma was involved in the study design and data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Dr. Straumann disclosed fees from several pharmaceutical companies, including Dr. Falk Pharma and AstraZeneca, which makes budesonide. Several other coinvestigators also disclosed ties to Dr. Falk Pharma, AstraZeneca, and other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Straumann A et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 July 25. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.07.039.

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) continues to rise in prevalence and prescription steroid therapy is limited to off-label use leading to a call for action for directed therapy for EoE and understanding long-term remission rates. In this phase 3 study, Straumann and colleagues studied budesonide orodispersible tablets (BOTs) and their ability to maintain remission, compared with placebo, at two doses specifically designed for EoE in adults with proton pump inhibitor–refractory EoE. Regardless of dose, at either 1.0 mg twice a day or 0.5 mg twice a day, there was an improvement in maintaining remission (73.5% for low dose and 75% for high dose, compared with 4.4% with placebo) at 48 weeks of therapy. Common side effects studied include an increase in candidiasis (12%-16% of patients), but there was no statistical change in morning cortisol.

Given the need for maintenance therapy for EoE, this study proves long-term efficacy and safety for the treatment of this chronic condition with a targeted esophageal formulation. We now have evidence of maintaining remission for EoE with a safe side-effect profile. Future research will be needed to look at long-term steroid use on bone health and immune dysregulation, especially in the pediatric population, which was not studied in this cohort. Moreover, future studies are needed to determine a minimally effective dose to help prevent potential side effects that can maintain remission while allowing discontinuation of all stable proton pump inhibitor doses to ensure no confounding effect.

Rishi D. Naik, MD, MSCI, is an assistant professor, department of medicine, section of gastroenterology & hepatology, Esophageal Center at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn. He has no conflicts.

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) continues to rise in prevalence and prescription steroid therapy is limited to off-label use leading to a call for action for directed therapy for EoE and understanding long-term remission rates. In this phase 3 study, Straumann and colleagues studied budesonide orodispersible tablets (BOTs) and their ability to maintain remission, compared with placebo, at two doses specifically designed for EoE in adults with proton pump inhibitor–refractory EoE. Regardless of dose, at either 1.0 mg twice a day or 0.5 mg twice a day, there was an improvement in maintaining remission (73.5% for low dose and 75% for high dose, compared with 4.4% with placebo) at 48 weeks of therapy. Common side effects studied include an increase in candidiasis (12%-16% of patients), but there was no statistical change in morning cortisol.

Given the need for maintenance therapy for EoE, this study proves long-term efficacy and safety for the treatment of this chronic condition with a targeted esophageal formulation. We now have evidence of maintaining remission for EoE with a safe side-effect profile. Future research will be needed to look at long-term steroid use on bone health and immune dysregulation, especially in the pediatric population, which was not studied in this cohort. Moreover, future studies are needed to determine a minimally effective dose to help prevent potential side effects that can maintain remission while allowing discontinuation of all stable proton pump inhibitor doses to ensure no confounding effect.

Rishi D. Naik, MD, MSCI, is an assistant professor, department of medicine, section of gastroenterology & hepatology, Esophageal Center at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn. He has no conflicts.

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) continues to rise in prevalence and prescription steroid therapy is limited to off-label use leading to a call for action for directed therapy for EoE and understanding long-term remission rates. In this phase 3 study, Straumann and colleagues studied budesonide orodispersible tablets (BOTs) and their ability to maintain remission, compared with placebo, at two doses specifically designed for EoE in adults with proton pump inhibitor–refractory EoE. Regardless of dose, at either 1.0 mg twice a day or 0.5 mg twice a day, there was an improvement in maintaining remission (73.5% for low dose and 75% for high dose, compared with 4.4% with placebo) at 48 weeks of therapy. Common side effects studied include an increase in candidiasis (12%-16% of patients), but there was no statistical change in morning cortisol.

Given the need for maintenance therapy for EoE, this study proves long-term efficacy and safety for the treatment of this chronic condition with a targeted esophageal formulation. We now have evidence of maintaining remission for EoE with a safe side-effect profile. Future research will be needed to look at long-term steroid use on bone health and immune dysregulation, especially in the pediatric population, which was not studied in this cohort. Moreover, future studies are needed to determine a minimally effective dose to help prevent potential side effects that can maintain remission while allowing discontinuation of all stable proton pump inhibitor doses to ensure no confounding effect.

Rishi D. Naik, MD, MSCI, is an assistant professor, department of medicine, section of gastroenterology & hepatology, Esophageal Center at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn. He has no conflicts.

Budesonide orodispersible tablets maintained remissions of eosinophilic esophagitis for 48 weeks in approximately 75% of patients and did not increase the risk for most adverse events, compared with placebo, according to the findings of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial.

While prior studies have shown that swallowed topical corticosteroids such as budesonide or fluticasone induce remission in EoE, this is the first multicenter phase 3 study of budesonide orodispersible tablets (BOTs) for maintaining remissions over the long term, wrote Alex Straumann, MD, of the Swiss EoE Research Group and University Hospital Zurich, and associates in Gastroenterology.

Eosinophilic esophagitis is the most common cause of esophageal dysphagia and food impaction. Swallowed topical corticosteroids improve symptoms and inflammation, but the off-label use of formulations developed for airway administration in asthma shows “suboptimal esophageal targeting and efficacy,” the researchers wrote. In the phase 3 EOS-2 trial, twice-daily treatment with 1.0 mg BOTs had induced clinicohistologic remissions in 58% of adults with EoE at 6 weeks and in 85% at 12 weeks.

To study long-term maintenance BOT therapy, the researchers randomly assigned 204 of the remitted patients to 48 weeks of twice-daily BOT 0.5 mg, BOT 1.0 mg, or placebo. There were 68 patients per group. A total of 141 patients completed this double-blind phase, but all 204 were evaluable for the primary analysis. The primary outcome was remission at week 48, defined as freedom from relapse (dysphagia or odynophagia rated as 4 or higher on a 10-point numeric rating scale), histologic relapse (≥48 eosinophils per mm2 high-power field), food impaction requiring endoscopic intervention, and dilation.

After 48 weeks, 51 patients in the 1-mg group (75%) and 50 patients in the 0.5-mg group (73.5%) remained in remission, compared with only three patients in the placebo group (4.4%; both P less than .0001). Patients in the placebo group relapsed after a median of 87 days off BOTs. Overall, BOT therapy was similarly efficacious regardless of factors such as history of allergic diseases, location of inflammation at the start of induction, or concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors. However, patients with inflammation of all three esophageal segments achieved “clinically relevant” greater rates of remission with twice-daily 1.0-mg BOT, compared with twice-daily 0.5-mg BOT (80% vs. 68%). In secondary analyses, rates of histologic relapse were 13.2% with 0.5-mg BOT twice daily, 10.3% with 1.0-mg BOT twice daily, and 90% with placebo, and rates of clinical relapse were 10.3%, 7.4%, and 60.3%, respectively. “Histological remission in the BOT 0.5 and 1.0mg twice daily group was independently maintained in all esophageal segments,” the researchers reported.

Rates of most adverse events were similar across treatment groups, and no serious treatment-emergent adverse events were reported. Average morning serum cortisol levels were similar among groups and did not change after treatment ended, but four patients on BOT therapy developed asymptomatic subnormal levels of morning cortisol. “Clinically manifested candidiasis was suspected in 16.2% of patients in the BOT 0.5mg group and in 11.8% of patients in the BOT 1.0mg group; all infections resolved with treatment,” the researchers wrote.

The study and editorial support were funded by Dr. Falk Pharma GmbH, a pharmaceutical company in Germany. Dr. Falk Pharma was involved in the study design and data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Dr. Straumann disclosed fees from several pharmaceutical companies, including Dr. Falk Pharma and AstraZeneca, which makes budesonide. Several other coinvestigators also disclosed ties to Dr. Falk Pharma, AstraZeneca, and other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Straumann A et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 July 25. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.07.039.

Budesonide orodispersible tablets maintained remissions of eosinophilic esophagitis for 48 weeks in approximately 75% of patients and did not increase the risk for most adverse events, compared with placebo, according to the findings of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial.

While prior studies have shown that swallowed topical corticosteroids such as budesonide or fluticasone induce remission in EoE, this is the first multicenter phase 3 study of budesonide orodispersible tablets (BOTs) for maintaining remissions over the long term, wrote Alex Straumann, MD, of the Swiss EoE Research Group and University Hospital Zurich, and associates in Gastroenterology.

Eosinophilic esophagitis is the most common cause of esophageal dysphagia and food impaction. Swallowed topical corticosteroids improve symptoms and inflammation, but the off-label use of formulations developed for airway administration in asthma shows “suboptimal esophageal targeting and efficacy,” the researchers wrote. In the phase 3 EOS-2 trial, twice-daily treatment with 1.0 mg BOTs had induced clinicohistologic remissions in 58% of adults with EoE at 6 weeks and in 85% at 12 weeks.

To study long-term maintenance BOT therapy, the researchers randomly assigned 204 of the remitted patients to 48 weeks of twice-daily BOT 0.5 mg, BOT 1.0 mg, or placebo. There were 68 patients per group. A total of 141 patients completed this double-blind phase, but all 204 were evaluable for the primary analysis. The primary outcome was remission at week 48, defined as freedom from relapse (dysphagia or odynophagia rated as 4 or higher on a 10-point numeric rating scale), histologic relapse (≥48 eosinophils per mm2 high-power field), food impaction requiring endoscopic intervention, and dilation.

After 48 weeks, 51 patients in the 1-mg group (75%) and 50 patients in the 0.5-mg group (73.5%) remained in remission, compared with only three patients in the placebo group (4.4%; both P less than .0001). Patients in the placebo group relapsed after a median of 87 days off BOTs. Overall, BOT therapy was similarly efficacious regardless of factors such as history of allergic diseases, location of inflammation at the start of induction, or concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors. However, patients with inflammation of all three esophageal segments achieved “clinically relevant” greater rates of remission with twice-daily 1.0-mg BOT, compared with twice-daily 0.5-mg BOT (80% vs. 68%). In secondary analyses, rates of histologic relapse were 13.2% with 0.5-mg BOT twice daily, 10.3% with 1.0-mg BOT twice daily, and 90% with placebo, and rates of clinical relapse were 10.3%, 7.4%, and 60.3%, respectively. “Histological remission in the BOT 0.5 and 1.0mg twice daily group was independently maintained in all esophageal segments,” the researchers reported.

Rates of most adverse events were similar across treatment groups, and no serious treatment-emergent adverse events were reported. Average morning serum cortisol levels were similar among groups and did not change after treatment ended, but four patients on BOT therapy developed asymptomatic subnormal levels of morning cortisol. “Clinically manifested candidiasis was suspected in 16.2% of patients in the BOT 0.5mg group and in 11.8% of patients in the BOT 1.0mg group; all infections resolved with treatment,” the researchers wrote.

The study and editorial support were funded by Dr. Falk Pharma GmbH, a pharmaceutical company in Germany. Dr. Falk Pharma was involved in the study design and data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Dr. Straumann disclosed fees from several pharmaceutical companies, including Dr. Falk Pharma and AstraZeneca, which makes budesonide. Several other coinvestigators also disclosed ties to Dr. Falk Pharma, AstraZeneca, and other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Straumann A et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 July 25. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.07.039.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

PPIs associated with diabetes risk, but questions remain

Regular use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) is associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes, according to a large prospective analysis of the Nurses’ Health Study. The results follow on other studies suggesting other potential adverse effects of PPIs such as dementia, kidney damage, and micronutrient deficiencies.

The authors, led by Jinqiu Yuan and Changhua Zhang of Sun Yat-sen University (Guangdong, China), call for regular blood glucose testing and diabetes screening for patients on long-term PPIs. But not all are convinced. “I think that’s a strong recommendation from the available data and it’s unclear how oe who would implement that in practice. I think instead practitioners should adhere to best practices, which emphasize using the lowest effective dose of PPIs for patients with appropriate indications,” David Leiman, MD, MSHP, assistant professor of medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C. said in an interview.

“Overall, the data from the study can be classified as provocative results that I think may warrant further study,” he added. Consistent and strongly positive findings from more observationsal studies would be required to establish causality between PPI use and diabetes risk, and in any case the findings of the surrent study don't warrant a change in practice, Dr. Leiman said, noting that the study’s design makes it likely that much or all of the observed associations were due to unmeasured confounding.

The study appeared online Sept. 28 in Gut.

The researchers analyzed data from 80,500 women from the Nurses’ Health Study, 95,550 women from the Nurses’ Health Study II, and 28,639 men from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS), with a median follow-up time of 12 years in NHS and NHS2 and 9.8 years in HPFS.

The absolute risk of diabetes was 7.44 per 1,000 person-years in PPI users versus 4.32 among nonusers. After adjustment for lagging PPI use for 2 years and stratification by age and study period, PPI use was associated with a 74% increased risk of diabetes (hazard ratio , 1.74; 95% confidence interval, 1.37-2.20). Multivariable adjustment for demographic factors, lifestyle habits, comorbidities, and use of other medications and clinical indications for PPI use attenuated the association but did not eliminate it (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.17-1.31).

There was no statistically significant association in the HPFS group (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.91-1.38), possibly because of the smaller sample size.

At 1 year, the number needed to harm with PPIs was 318.9 (95% CI, 285.2-385.0). At 2 years it was 170.8 (95% CI, 150.8-209.7) and at 3 years it was 77.3 (95% CI, 66.8-97.0).

At 0-2 years, PPI use was associated with a 5% increase in diabetes risk (HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.93-1.19). More than 2 years of use was associated with higher risk (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.18-1.35).

There was also an association between stopping PPI use and a decreased risk of diabetes: Compared with current PPI users, those who had stopped within the past 2 years had a 17% reduction in risk (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.70-0.98), and those who had stopped more than 2 years previously had a 19% reduction (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.76-0.86).

The researchers also examined diabetes risk associated with use of H2 receptor agonists (H2RAs), since the drugs share clinical indications with PPIs. H2RA use was also associated with a higher risk of diabetes (adjusted HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.07-1.23).

The researchers suggested that the fact that the less potent H2RA inhibitors had a less pronounced association with diabetes risk supports the idea that acid suppression may be related to diabetes pathogenesis.

The authors also suggest that changes to the gut microbiota may underlie increased risk. PPI use has been shown to reduce gut microbiome diversity and alter its phenotype. Such changes could lead to weight gain, metabolic syndrome, and chronic liver disease, which could in turn heighten risk.

The study is limited by its observational nature, and lacked detailed information on dosage, frequency, and indications for PPI use.

SOURCE: Yuan J et al. Gut. 2020 Sep 28. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322557.

This story was updated on 11/24/2020.

Help your patients understand the risks and benefits of long-term PPI use by sharing the AGA Clinical Practice Update patient companion at http://ow.ly/N1

Regular use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) is associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes, according to a large prospective analysis of the Nurses’ Health Study. The results follow on other studies suggesting other potential adverse effects of PPIs such as dementia, kidney damage, and micronutrient deficiencies.

The authors, led by Jinqiu Yuan and Changhua Zhang of Sun Yat-sen University (Guangdong, China), call for regular blood glucose testing and diabetes screening for patients on long-term PPIs. But not all are convinced. “I think that’s a strong recommendation from the available data and it’s unclear how oe who would implement that in practice. I think instead practitioners should adhere to best practices, which emphasize using the lowest effective dose of PPIs for patients with appropriate indications,” David Leiman, MD, MSHP, assistant professor of medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C. said in an interview.

“Overall, the data from the study can be classified as provocative results that I think may warrant further study,” he added. Consistent and strongly positive findings from more observationsal studies would be required to establish causality between PPI use and diabetes risk, and in any case the findings of the surrent study don't warrant a change in practice, Dr. Leiman said, noting that the study’s design makes it likely that much or all of the observed associations were due to unmeasured confounding.

The study appeared online Sept. 28 in Gut.

The researchers analyzed data from 80,500 women from the Nurses’ Health Study, 95,550 women from the Nurses’ Health Study II, and 28,639 men from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS), with a median follow-up time of 12 years in NHS and NHS2 and 9.8 years in HPFS.

The absolute risk of diabetes was 7.44 per 1,000 person-years in PPI users versus 4.32 among nonusers. After adjustment for lagging PPI use for 2 years and stratification by age and study period, PPI use was associated with a 74% increased risk of diabetes (hazard ratio , 1.74; 95% confidence interval, 1.37-2.20). Multivariable adjustment for demographic factors, lifestyle habits, comorbidities, and use of other medications and clinical indications for PPI use attenuated the association but did not eliminate it (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.17-1.31).

There was no statistically significant association in the HPFS group (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.91-1.38), possibly because of the smaller sample size.

At 1 year, the number needed to harm with PPIs was 318.9 (95% CI, 285.2-385.0). At 2 years it was 170.8 (95% CI, 150.8-209.7) and at 3 years it was 77.3 (95% CI, 66.8-97.0).

At 0-2 years, PPI use was associated with a 5% increase in diabetes risk (HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.93-1.19). More than 2 years of use was associated with higher risk (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.18-1.35).

There was also an association between stopping PPI use and a decreased risk of diabetes: Compared with current PPI users, those who had stopped within the past 2 years had a 17% reduction in risk (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.70-0.98), and those who had stopped more than 2 years previously had a 19% reduction (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.76-0.86).

The researchers also examined diabetes risk associated with use of H2 receptor agonists (H2RAs), since the drugs share clinical indications with PPIs. H2RA use was also associated with a higher risk of diabetes (adjusted HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.07-1.23).

The researchers suggested that the fact that the less potent H2RA inhibitors had a less pronounced association with diabetes risk supports the idea that acid suppression may be related to diabetes pathogenesis.

The authors also suggest that changes to the gut microbiota may underlie increased risk. PPI use has been shown to reduce gut microbiome diversity and alter its phenotype. Such changes could lead to weight gain, metabolic syndrome, and chronic liver disease, which could in turn heighten risk.

The study is limited by its observational nature, and lacked detailed information on dosage, frequency, and indications for PPI use.

SOURCE: Yuan J et al. Gut. 2020 Sep 28. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322557.

This story was updated on 11/24/2020.

Help your patients understand the risks and benefits of long-term PPI use by sharing the AGA Clinical Practice Update patient companion at http://ow.ly/N1

Regular use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) is associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes, according to a large prospective analysis of the Nurses’ Health Study. The results follow on other studies suggesting other potential adverse effects of PPIs such as dementia, kidney damage, and micronutrient deficiencies.

The authors, led by Jinqiu Yuan and Changhua Zhang of Sun Yat-sen University (Guangdong, China), call for regular blood glucose testing and diabetes screening for patients on long-term PPIs. But not all are convinced. “I think that’s a strong recommendation from the available data and it’s unclear how oe who would implement that in practice. I think instead practitioners should adhere to best practices, which emphasize using the lowest effective dose of PPIs for patients with appropriate indications,” David Leiman, MD, MSHP, assistant professor of medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C. said in an interview.

“Overall, the data from the study can be classified as provocative results that I think may warrant further study,” he added. Consistent and strongly positive findings from more observationsal studies would be required to establish causality between PPI use and diabetes risk, and in any case the findings of the surrent study don't warrant a change in practice, Dr. Leiman said, noting that the study’s design makes it likely that much or all of the observed associations were due to unmeasured confounding.

The study appeared online Sept. 28 in Gut.

The researchers analyzed data from 80,500 women from the Nurses’ Health Study, 95,550 women from the Nurses’ Health Study II, and 28,639 men from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS), with a median follow-up time of 12 years in NHS and NHS2 and 9.8 years in HPFS.

The absolute risk of diabetes was 7.44 per 1,000 person-years in PPI users versus 4.32 among nonusers. After adjustment for lagging PPI use for 2 years and stratification by age and study period, PPI use was associated with a 74% increased risk of diabetes (hazard ratio , 1.74; 95% confidence interval, 1.37-2.20). Multivariable adjustment for demographic factors, lifestyle habits, comorbidities, and use of other medications and clinical indications for PPI use attenuated the association but did not eliminate it (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.17-1.31).

There was no statistically significant association in the HPFS group (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.91-1.38), possibly because of the smaller sample size.

At 1 year, the number needed to harm with PPIs was 318.9 (95% CI, 285.2-385.0). At 2 years it was 170.8 (95% CI, 150.8-209.7) and at 3 years it was 77.3 (95% CI, 66.8-97.0).

At 0-2 years, PPI use was associated with a 5% increase in diabetes risk (HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.93-1.19). More than 2 years of use was associated with higher risk (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.18-1.35).

There was also an association between stopping PPI use and a decreased risk of diabetes: Compared with current PPI users, those who had stopped within the past 2 years had a 17% reduction in risk (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.70-0.98), and those who had stopped more than 2 years previously had a 19% reduction (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.76-0.86).

The researchers also examined diabetes risk associated with use of H2 receptor agonists (H2RAs), since the drugs share clinical indications with PPIs. H2RA use was also associated with a higher risk of diabetes (adjusted HR, 1.14; 95% CI, 1.07-1.23).

The researchers suggested that the fact that the less potent H2RA inhibitors had a less pronounced association with diabetes risk supports the idea that acid suppression may be related to diabetes pathogenesis.

The authors also suggest that changes to the gut microbiota may underlie increased risk. PPI use has been shown to reduce gut microbiome diversity and alter its phenotype. Such changes could lead to weight gain, metabolic syndrome, and chronic liver disease, which could in turn heighten risk.

The study is limited by its observational nature, and lacked detailed information on dosage, frequency, and indications for PPI use.

SOURCE: Yuan J et al. Gut. 2020 Sep 28. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322557.

This story was updated on 11/24/2020.

Help your patients understand the risks and benefits of long-term PPI use by sharing the AGA Clinical Practice Update patient companion at http://ow.ly/N1

FROM GUT

GERD: Endoscopic therapies may offer alternative to PPIs

For patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), endoscopic and minimally invasive surgical techniques may be viable alternatives to proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, according to investigators.

Still, their exact role in the treatment process remains undetermined, reported Michael F. Vaezi, MD, PhD, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., and colleagues.

“The frequent incomplete response to PPI therapy, in addition to recent studies suggesting chronic complications with PPI therapy, have fueled discussion of alternative strategies for treating patients with GERD,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology. “For a substantial number of patients and providers with the above concerns who are unwilling to pursue the traditional surgical gastric fundoplication, endoscopic or less invasive surgical strategies have gained some traction.”

Dr. Vaezi and colleagues noted that they conducted the scoping review with intentions of being more descriptive than prescriptive.

“Our goal is not to recommend the utility of any of the discussed techniques in specific clinical scenarios,” they wrote. “Rather, it is to summarize the currently available evidence and identify where more research may be helpful.”

Across 22 randomized, controlled trials and observational studies, objective and symptomatic improvement varied between modalities. Measured outcomes also varied; most studies reported symptoms, health-related quality of life, and PPI use; fewer studies (but still a majority) reported intraesophageal acid exposure and/or lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure. Conclusions drawn by Dr. Vaezi and colleagues are summarized below.

Magnetic sphincter augmentation of the LES

In multiple trials, magnetic sphincter augmentation demonstrated a “high degree of efficacy” in the short or midterm, and a favorable safety profile. Dr. Vaezi and colleagues highlighted significant improvements in disease-related quality of life, with “a substantial proportion” of patients achieving normalization or at least 50% improvement in acid exposure. While some patients required esophageal dilation after the procedure, this was not needed any more frequently than after surgical fundoplication.

Radiofrequency ablation

Across five trials, radiofrequency ablation, which involves delivery of energy to the LES and gastric cardia, improved GERD-related quality of life, and reduced, but did not normalize, acid exposure. The technique lessened short-term need for PPIs, but long-term relief was not observed. Compared with observational studies, efficacy signals were weaker in randomized, controlled trials. The procedure was generally safe.

Surgical implantation of LES pacemaker

Limited data were available for LES sphincter stimulation among patients with GERD, and the most recent study, involving a comparison of device placement with or without stimulation, was terminated early. Still, available data suggest that the technique is generally well tolerated, with reduced need for PPIs, improved symptoms, and lessened acid exposure. Dr. Vaezi and colleagues noted that the manufacturing company, EndoStim, is in receivership, putting U.S. availability in question.

Full-thickness fundoplication

Endoscopic full-thickness fundoplication was associated with improvement of symptoms and quality of life, and a favorable safety profile. Although the procedure generally reduced PPI use, most patients still needed PPIs long-term. Reflux improved after the procedure, but not to the same degree as laparoscopic plication.

Transoral incisionless fundoplication

Based on a number of studies, including five randomized, controlled trials, transoral incisionless fundoplication appears safe and effective, with reduced need for PPIs up to 5 years. According to Dr. Vaezi and colleagues, variable results across studies are likely explained by variations in the technique over time and heterogeneous patient populations. Recent studies in which the “TIF 2.0 technique” has been performed on patients with hiatal hernias less than 2 cm have met objective efficacy outcomes.

Incisionless fundoplication with magnetic ultrasonic surgical endostapler

The magnetic ultrasonic surgical endostapler, which allows for incisionless fundoplication, had more limited data. Only two studies have been conducted, and neither had sham-controlled nor comparative-trial data. Furthermore, multiple safety signals have been encountered, with “substantial” complication rates and serious adverse events that were “noticeable and concerning,” according to Dr. Vaezi and colleagues.

Concluding their discussion, the investigators suggested that some endoscopic and minimally invasive approaches to GERD are “promising” alternatives to PPI therapy.

“However, their place in the treatment algorithm for GERD will be better defined when important clinical parameters, especially the durability of their effect, are understood,” they wrote.

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Vaezi MF et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Jul 1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.097.

For patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), endoscopic and minimally invasive surgical techniques may be viable alternatives to proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, according to investigators.

Still, their exact role in the treatment process remains undetermined, reported Michael F. Vaezi, MD, PhD, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., and colleagues.

“The frequent incomplete response to PPI therapy, in addition to recent studies suggesting chronic complications with PPI therapy, have fueled discussion of alternative strategies for treating patients with GERD,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology. “For a substantial number of patients and providers with the above concerns who are unwilling to pursue the traditional surgical gastric fundoplication, endoscopic or less invasive surgical strategies have gained some traction.”

Dr. Vaezi and colleagues noted that they conducted the scoping review with intentions of being more descriptive than prescriptive.

“Our goal is not to recommend the utility of any of the discussed techniques in specific clinical scenarios,” they wrote. “Rather, it is to summarize the currently available evidence and identify where more research may be helpful.”

Across 22 randomized, controlled trials and observational studies, objective and symptomatic improvement varied between modalities. Measured outcomes also varied; most studies reported symptoms, health-related quality of life, and PPI use; fewer studies (but still a majority) reported intraesophageal acid exposure and/or lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure. Conclusions drawn by Dr. Vaezi and colleagues are summarized below.

Magnetic sphincter augmentation of the LES

In multiple trials, magnetic sphincter augmentation demonstrated a “high degree of efficacy” in the short or midterm, and a favorable safety profile. Dr. Vaezi and colleagues highlighted significant improvements in disease-related quality of life, with “a substantial proportion” of patients achieving normalization or at least 50% improvement in acid exposure. While some patients required esophageal dilation after the procedure, this was not needed any more frequently than after surgical fundoplication.

Radiofrequency ablation

Across five trials, radiofrequency ablation, which involves delivery of energy to the LES and gastric cardia, improved GERD-related quality of life, and reduced, but did not normalize, acid exposure. The technique lessened short-term need for PPIs, but long-term relief was not observed. Compared with observational studies, efficacy signals were weaker in randomized, controlled trials. The procedure was generally safe.

Surgical implantation of LES pacemaker

Limited data were available for LES sphincter stimulation among patients with GERD, and the most recent study, involving a comparison of device placement with or without stimulation, was terminated early. Still, available data suggest that the technique is generally well tolerated, with reduced need for PPIs, improved symptoms, and lessened acid exposure. Dr. Vaezi and colleagues noted that the manufacturing company, EndoStim, is in receivership, putting U.S. availability in question.

Full-thickness fundoplication

Endoscopic full-thickness fundoplication was associated with improvement of symptoms and quality of life, and a favorable safety profile. Although the procedure generally reduced PPI use, most patients still needed PPIs long-term. Reflux improved after the procedure, but not to the same degree as laparoscopic plication.

Transoral incisionless fundoplication

Based on a number of studies, including five randomized, controlled trials, transoral incisionless fundoplication appears safe and effective, with reduced need for PPIs up to 5 years. According to Dr. Vaezi and colleagues, variable results across studies are likely explained by variations in the technique over time and heterogeneous patient populations. Recent studies in which the “TIF 2.0 technique” has been performed on patients with hiatal hernias less than 2 cm have met objective efficacy outcomes.

Incisionless fundoplication with magnetic ultrasonic surgical endostapler

The magnetic ultrasonic surgical endostapler, which allows for incisionless fundoplication, had more limited data. Only two studies have been conducted, and neither had sham-controlled nor comparative-trial data. Furthermore, multiple safety signals have been encountered, with “substantial” complication rates and serious adverse events that were “noticeable and concerning,” according to Dr. Vaezi and colleagues.

Concluding their discussion, the investigators suggested that some endoscopic and minimally invasive approaches to GERD are “promising” alternatives to PPI therapy.

“However, their place in the treatment algorithm for GERD will be better defined when important clinical parameters, especially the durability of their effect, are understood,” they wrote.

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Vaezi MF et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Jul 1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.097.

For patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), endoscopic and minimally invasive surgical techniques may be viable alternatives to proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, according to investigators.

Still, their exact role in the treatment process remains undetermined, reported Michael F. Vaezi, MD, PhD, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., and colleagues.

“The frequent incomplete response to PPI therapy, in addition to recent studies suggesting chronic complications with PPI therapy, have fueled discussion of alternative strategies for treating patients with GERD,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology. “For a substantial number of patients and providers with the above concerns who are unwilling to pursue the traditional surgical gastric fundoplication, endoscopic or less invasive surgical strategies have gained some traction.”

Dr. Vaezi and colleagues noted that they conducted the scoping review with intentions of being more descriptive than prescriptive.

“Our goal is not to recommend the utility of any of the discussed techniques in specific clinical scenarios,” they wrote. “Rather, it is to summarize the currently available evidence and identify where more research may be helpful.”

Across 22 randomized, controlled trials and observational studies, objective and symptomatic improvement varied between modalities. Measured outcomes also varied; most studies reported symptoms, health-related quality of life, and PPI use; fewer studies (but still a majority) reported intraesophageal acid exposure and/or lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure. Conclusions drawn by Dr. Vaezi and colleagues are summarized below.

Magnetic sphincter augmentation of the LES

In multiple trials, magnetic sphincter augmentation demonstrated a “high degree of efficacy” in the short or midterm, and a favorable safety profile. Dr. Vaezi and colleagues highlighted significant improvements in disease-related quality of life, with “a substantial proportion” of patients achieving normalization or at least 50% improvement in acid exposure. While some patients required esophageal dilation after the procedure, this was not needed any more frequently than after surgical fundoplication.

Radiofrequency ablation

Across five trials, radiofrequency ablation, which involves delivery of energy to the LES and gastric cardia, improved GERD-related quality of life, and reduced, but did not normalize, acid exposure. The technique lessened short-term need for PPIs, but long-term relief was not observed. Compared with observational studies, efficacy signals were weaker in randomized, controlled trials. The procedure was generally safe.

Surgical implantation of LES pacemaker

Limited data were available for LES sphincter stimulation among patients with GERD, and the most recent study, involving a comparison of device placement with or without stimulation, was terminated early. Still, available data suggest that the technique is generally well tolerated, with reduced need for PPIs, improved symptoms, and lessened acid exposure. Dr. Vaezi and colleagues noted that the manufacturing company, EndoStim, is in receivership, putting U.S. availability in question.

Full-thickness fundoplication

Endoscopic full-thickness fundoplication was associated with improvement of symptoms and quality of life, and a favorable safety profile. Although the procedure generally reduced PPI use, most patients still needed PPIs long-term. Reflux improved after the procedure, but not to the same degree as laparoscopic plication.

Transoral incisionless fundoplication

Based on a number of studies, including five randomized, controlled trials, transoral incisionless fundoplication appears safe and effective, with reduced need for PPIs up to 5 years. According to Dr. Vaezi and colleagues, variable results across studies are likely explained by variations in the technique over time and heterogeneous patient populations. Recent studies in which the “TIF 2.0 technique” has been performed on patients with hiatal hernias less than 2 cm have met objective efficacy outcomes.

Incisionless fundoplication with magnetic ultrasonic surgical endostapler

The magnetic ultrasonic surgical endostapler, which allows for incisionless fundoplication, had more limited data. Only two studies have been conducted, and neither had sham-controlled nor comparative-trial data. Furthermore, multiple safety signals have been encountered, with “substantial” complication rates and serious adverse events that were “noticeable and concerning,” according to Dr. Vaezi and colleagues.

Concluding their discussion, the investigators suggested that some endoscopic and minimally invasive approaches to GERD are “promising” alternatives to PPI therapy.

“However, their place in the treatment algorithm for GERD will be better defined when important clinical parameters, especially the durability of their effect, are understood,” they wrote.

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Vaezi MF et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Jul 1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.097.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

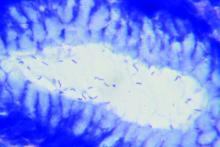

CagA-positive H. pylori patients at higher risk of osteoporosis, fracture

A new study has found that older patients who test positive for the cytotoxin associated gene-A (CagA) strain of Helicobacter pylori may be more at risk of both osteoporosis and fractures.

“Further studies will be required to replicate these findings in other cohorts and to better clarify the underlying pathogenetic mechanisms leading to increased bone fragility in subjects infected by CagA-positive H. pylori strains,” wrote Luigi Gennari, MD, PhD, of the University of Siena (Italy), and coauthors. The study was published in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

To determine the effects of H. pylori on bone health and potential fracture risk, the researchers launched a population-based cohort study of 1,149 adults between the ages of 50 and 80 in Siena. The cohort comprised 174 males with an average (SD) age of 65.9 (plus or minus 6 years) and 975 females with an average age of 62.5 (plus or minus 6 years). All subjects were examined for H. pylori antibodies, and those who were infected were also examined for anti-CagA serum antibodies. As blood was sampled, bone mineral density (BMD) of the lumbar spine, femoral neck, total hip, and total body was measured via dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.

In total, 53% of male participants and 49% of female participants tested positive for H. pylori, with CagA-positive strains found in 27% of males and 26% of females. No differences in infection rates were discovered in regard to socioeconomic status, age, weight, or height. Patients with normal BMD (45%), osteoporosis (51%), or osteopenia (49%) had similar prevalence of H. pylori infection, but CagA-positive strains were more frequently found in osteoporotic (30%) and osteopenic (26%) patients, compared to patients with normal BMD (21%, P < .01). CagA-positive female patients also had lower lumbar (0.950 g/cm2) and femoral (0.795 g/cm2) BMD, compared to CagA-negative (0.987 and 0.813 g/cm2) or H. pylori-negative women (0.997 and 0.821 g/cm2), respectively.

After an average follow-up period of 11.8 years, 199 nontraumatic fractures (72 vertebral and 127 nonvertebral) had occurred in 158 participants. Patients with CagA-positive strains of H. pylori had significantly increased risk of a clinical vertebral fracture (hazard ratio [HR], 5.27; 95% confidence interval, 2.23-12.63; P < .0001) or a nonvertebral incident fracture (HR, 2.09; 95% CI, 1.27-2.46; P < .01), compared to patients without H. pylori. After adjustment for age, sex, and body mass index, the risk among CagA-positive patients remained similarly significantly elevated for both vertebral (aHR, 4.78; 95% CI, 1.99-11.47; P < .0001) and nonvertebral fractures (aHR, 2.04; 95% CI, 1.22-3.41; P < .01).

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including a cohort that was notably low in male participants, an inability to assess the effects of eradicating H. pylori on bone, and uncertainty as to which specific effects of H. pylori infection increase the risk of osteoporosis or fracture. Along those lines, they noted that an association between serum CagA antibody titer and gastric mucosal inflammation could lead to malabsorption of calcium, hypothesizing that antibody titer rather than antibody positivity “might be a more relevant marker for assessing the risk of bone fragility in patients affected by H. pylori infection.”

The study was supported in part by a grant from the Italian Association for Osteoporosis. The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gennari L et al. J Bone Miner Res. 2020 Aug 13. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.4162.

A new study has found that older patients who test positive for the cytotoxin associated gene-A (CagA) strain of Helicobacter pylori may be more at risk of both osteoporosis and fractures.

“Further studies will be required to replicate these findings in other cohorts and to better clarify the underlying pathogenetic mechanisms leading to increased bone fragility in subjects infected by CagA-positive H. pylori strains,” wrote Luigi Gennari, MD, PhD, of the University of Siena (Italy), and coauthors. The study was published in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

To determine the effects of H. pylori on bone health and potential fracture risk, the researchers launched a population-based cohort study of 1,149 adults between the ages of 50 and 80 in Siena. The cohort comprised 174 males with an average (SD) age of 65.9 (plus or minus 6 years) and 975 females with an average age of 62.5 (plus or minus 6 years). All subjects were examined for H. pylori antibodies, and those who were infected were also examined for anti-CagA serum antibodies. As blood was sampled, bone mineral density (BMD) of the lumbar spine, femoral neck, total hip, and total body was measured via dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.

In total, 53% of male participants and 49% of female participants tested positive for H. pylori, with CagA-positive strains found in 27% of males and 26% of females. No differences in infection rates were discovered in regard to socioeconomic status, age, weight, or height. Patients with normal BMD (45%), osteoporosis (51%), or osteopenia (49%) had similar prevalence of H. pylori infection, but CagA-positive strains were more frequently found in osteoporotic (30%) and osteopenic (26%) patients, compared to patients with normal BMD (21%, P < .01). CagA-positive female patients also had lower lumbar (0.950 g/cm2) and femoral (0.795 g/cm2) BMD, compared to CagA-negative (0.987 and 0.813 g/cm2) or H. pylori-negative women (0.997 and 0.821 g/cm2), respectively.

After an average follow-up period of 11.8 years, 199 nontraumatic fractures (72 vertebral and 127 nonvertebral) had occurred in 158 participants. Patients with CagA-positive strains of H. pylori had significantly increased risk of a clinical vertebral fracture (hazard ratio [HR], 5.27; 95% confidence interval, 2.23-12.63; P < .0001) or a nonvertebral incident fracture (HR, 2.09; 95% CI, 1.27-2.46; P < .01), compared to patients without H. pylori. After adjustment for age, sex, and body mass index, the risk among CagA-positive patients remained similarly significantly elevated for both vertebral (aHR, 4.78; 95% CI, 1.99-11.47; P < .0001) and nonvertebral fractures (aHR, 2.04; 95% CI, 1.22-3.41; P < .01).

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including a cohort that was notably low in male participants, an inability to assess the effects of eradicating H. pylori on bone, and uncertainty as to which specific effects of H. pylori infection increase the risk of osteoporosis or fracture. Along those lines, they noted that an association between serum CagA antibody titer and gastric mucosal inflammation could lead to malabsorption of calcium, hypothesizing that antibody titer rather than antibody positivity “might be a more relevant marker for assessing the risk of bone fragility in patients affected by H. pylori infection.”

The study was supported in part by a grant from the Italian Association for Osteoporosis. The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gennari L et al. J Bone Miner Res. 2020 Aug 13. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.4162.

A new study has found that older patients who test positive for the cytotoxin associated gene-A (CagA) strain of Helicobacter pylori may be more at risk of both osteoporosis and fractures.

“Further studies will be required to replicate these findings in other cohorts and to better clarify the underlying pathogenetic mechanisms leading to increased bone fragility in subjects infected by CagA-positive H. pylori strains,” wrote Luigi Gennari, MD, PhD, of the University of Siena (Italy), and coauthors. The study was published in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

To determine the effects of H. pylori on bone health and potential fracture risk, the researchers launched a population-based cohort study of 1,149 adults between the ages of 50 and 80 in Siena. The cohort comprised 174 males with an average (SD) age of 65.9 (plus or minus 6 years) and 975 females with an average age of 62.5 (plus or minus 6 years). All subjects were examined for H. pylori antibodies, and those who were infected were also examined for anti-CagA serum antibodies. As blood was sampled, bone mineral density (BMD) of the lumbar spine, femoral neck, total hip, and total body was measured via dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.

In total, 53% of male participants and 49% of female participants tested positive for H. pylori, with CagA-positive strains found in 27% of males and 26% of females. No differences in infection rates were discovered in regard to socioeconomic status, age, weight, or height. Patients with normal BMD (45%), osteoporosis (51%), or osteopenia (49%) had similar prevalence of H. pylori infection, but CagA-positive strains were more frequently found in osteoporotic (30%) and osteopenic (26%) patients, compared to patients with normal BMD (21%, P < .01). CagA-positive female patients also had lower lumbar (0.950 g/cm2) and femoral (0.795 g/cm2) BMD, compared to CagA-negative (0.987 and 0.813 g/cm2) or H. pylori-negative women (0.997 and 0.821 g/cm2), respectively.

After an average follow-up period of 11.8 years, 199 nontraumatic fractures (72 vertebral and 127 nonvertebral) had occurred in 158 participants. Patients with CagA-positive strains of H. pylori had significantly increased risk of a clinical vertebral fracture (hazard ratio [HR], 5.27; 95% confidence interval, 2.23-12.63; P < .0001) or a nonvertebral incident fracture (HR, 2.09; 95% CI, 1.27-2.46; P < .01), compared to patients without H. pylori. After adjustment for age, sex, and body mass index, the risk among CagA-positive patients remained similarly significantly elevated for both vertebral (aHR, 4.78; 95% CI, 1.99-11.47; P < .0001) and nonvertebral fractures (aHR, 2.04; 95% CI, 1.22-3.41; P < .01).

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including a cohort that was notably low in male participants, an inability to assess the effects of eradicating H. pylori on bone, and uncertainty as to which specific effects of H. pylori infection increase the risk of osteoporosis or fracture. Along those lines, they noted that an association between serum CagA antibody titer and gastric mucosal inflammation could lead to malabsorption of calcium, hypothesizing that antibody titer rather than antibody positivity “might be a more relevant marker for assessing the risk of bone fragility in patients affected by H. pylori infection.”

The study was supported in part by a grant from the Italian Association for Osteoporosis. The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gennari L et al. J Bone Miner Res. 2020 Aug 13. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.4162.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF BONE AND MINERAL RESEARCH

AGA updates endoscopic management of nonvariceal upper GI bleeding

The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) has published a clinical practice update for endoscopic management of nonvariceal upper GI bleeding (NVUGIB).

The update includes 10 best practice recommendations based on clinical experience and a comprehensive literature review, reported lead author Daniel K. Mullady, MD, of Washington University in St. Louis.

“Numerous endoscopic devices have been developed over the past 30 years with demonstrated effectiveness in treating NVUGIB,” Dr. Mullady and colleagues wrote in Gastroenterology. “The purpose of this clinical practice update is to review the key concepts, new devices, and therapeutic strategies in endoscopically combating this age-old clinical dilemma.”

According to the investigators, endoscopy is central to management of NVUGIB, but only after patients are appropriately triaged and stabilized.

“[E]ndoscopy should be performed to determine the source of bleeding, to assess rebleeding risk, and to treat lesions at high risk for rebleeding,” they wrote. “Exactly when the endoscopy should be performed is a clinical judgment made by the gastroenterologist in consultation with the primary service.”

The investigators recommended that endoscopy be performed within 12 hours for emergent cases and within 24 hours for urgent cases, whereas elective cases could wait longer.

They noted that NVUGIB can range from mild and self-limiting, allowing for outpatient management, to severe and life-threatening, necessitating intensive care. Because of this broad range, the investigators recommended familiarity with triage scoring systems, including the Glasgow-Blatchford Score, the Rockall Score, and AIMS-65.

“A common decision is deciding whether or not to wait until the next morning to perform endoscopy on a patient presenting after hours with suspected NVUGIB,” the investigators wrote.

The investigators cautioned that emergent endoscopy may actually be associated with poorer outcomes because of “inadequate resuscitation,” and suggested that “[p]atients who are hemodynamically stable, do not have ongoing hematemesis, and have melena only can generally be deferred to the following morning.”

Concerning hemostatic technique, Dr. Mullady and colleagues recommended familiarity with conventional thermal therapy and placement of hemoclips. If these approaches are unsuccessful, or deemed unlikely to succeed, they recommended an over-the-scope clip.

For ulcers “with a rigid and fibrotic base,” or those that are hard to reach, the investigators recommended monopolar hemostatic forceps with low-voltage coagulation.

According to the update, hemostatic powder should be reserved for scenarios in which bleeding is diffuse and difficult to locate.

“In most instances, hemostatic powder should be preferentially used as a rescue therapy and not for primary hemostasis, except in cases of malignant bleeding or massive bleeding with inability to perform thermal therapy or hemoclip placement,” the investigators wrote.

They noted that hemostatic powder generally dissolves in less than 24 hours, so additional treatment approaches should be considered, particular when there is a high risk of rebleeding.

When deciding between transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) and surgery after endoscopic failure, the update calls for a comprehensive clinical assessment that incorporates patient factors, such as coagulopathy, hemodynamic instability, and multiorgan failure; bleeding etiology; potential adverse effects; and rebleeding risk.

“An important point is that prophylactic TAE of high-risk ulcers after successful endoscopic therapy is not recommended,” the investigators wrote.

Beyond these recommendations, the update includes a comprehensive discussion of relevant literature and strategies for effective clinical decision making. The discussion concludes with global remarks about the evolving role of endoscopy in managing NVUGIB, including a note about cost-effectiveness despite up-front expenses associated with some methods.

“With this expanded endoscopic armamentarium, endoscopic therapy should achieve hemostasis in the majority of patients with NVUGIB,” the investigators wrote. “Despite the increased costs of newer devices or multimodal therapy, effective hemostasis to preventing rebleeding and the need for hospital readmission is likely to be a dominant cost-saving strategy.”

Dr. Mullady disclosed relationships with Boston Scientific, ConMed, and Cook Medical.

This story was updated on 9/9/2020.

SOURCE: Mullady DK et al. Gastro. 2020 Jun 20. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.095.

The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) has published a clinical practice update for endoscopic management of nonvariceal upper GI bleeding (NVUGIB).

The update includes 10 best practice recommendations based on clinical experience and a comprehensive literature review, reported lead author Daniel K. Mullady, MD, of Washington University in St. Louis.

“Numerous endoscopic devices have been developed over the past 30 years with demonstrated effectiveness in treating NVUGIB,” Dr. Mullady and colleagues wrote in Gastroenterology. “The purpose of this clinical practice update is to review the key concepts, new devices, and therapeutic strategies in endoscopically combating this age-old clinical dilemma.”

According to the investigators, endoscopy is central to management of NVUGIB, but only after patients are appropriately triaged and stabilized.

“[E]ndoscopy should be performed to determine the source of bleeding, to assess rebleeding risk, and to treat lesions at high risk for rebleeding,” they wrote. “Exactly when the endoscopy should be performed is a clinical judgment made by the gastroenterologist in consultation with the primary service.”

The investigators recommended that endoscopy be performed within 12 hours for emergent cases and within 24 hours for urgent cases, whereas elective cases could wait longer.

They noted that NVUGIB can range from mild and self-limiting, allowing for outpatient management, to severe and life-threatening, necessitating intensive care. Because of this broad range, the investigators recommended familiarity with triage scoring systems, including the Glasgow-Blatchford Score, the Rockall Score, and AIMS-65.

“A common decision is deciding whether or not to wait until the next morning to perform endoscopy on a patient presenting after hours with suspected NVUGIB,” the investigators wrote.

The investigators cautioned that emergent endoscopy may actually be associated with poorer outcomes because of “inadequate resuscitation,” and suggested that “[p]atients who are hemodynamically stable, do not have ongoing hematemesis, and have melena only can generally be deferred to the following morning.”

Concerning hemostatic technique, Dr. Mullady and colleagues recommended familiarity with conventional thermal therapy and placement of hemoclips. If these approaches are unsuccessful, or deemed unlikely to succeed, they recommended an over-the-scope clip.

For ulcers “with a rigid and fibrotic base,” or those that are hard to reach, the investigators recommended monopolar hemostatic forceps with low-voltage coagulation.

According to the update, hemostatic powder should be reserved for scenarios in which bleeding is diffuse and difficult to locate.

“In most instances, hemostatic powder should be preferentially used as a rescue therapy and not for primary hemostasis, except in cases of malignant bleeding or massive bleeding with inability to perform thermal therapy or hemoclip placement,” the investigators wrote.

They noted that hemostatic powder generally dissolves in less than 24 hours, so additional treatment approaches should be considered, particular when there is a high risk of rebleeding.